Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study framework

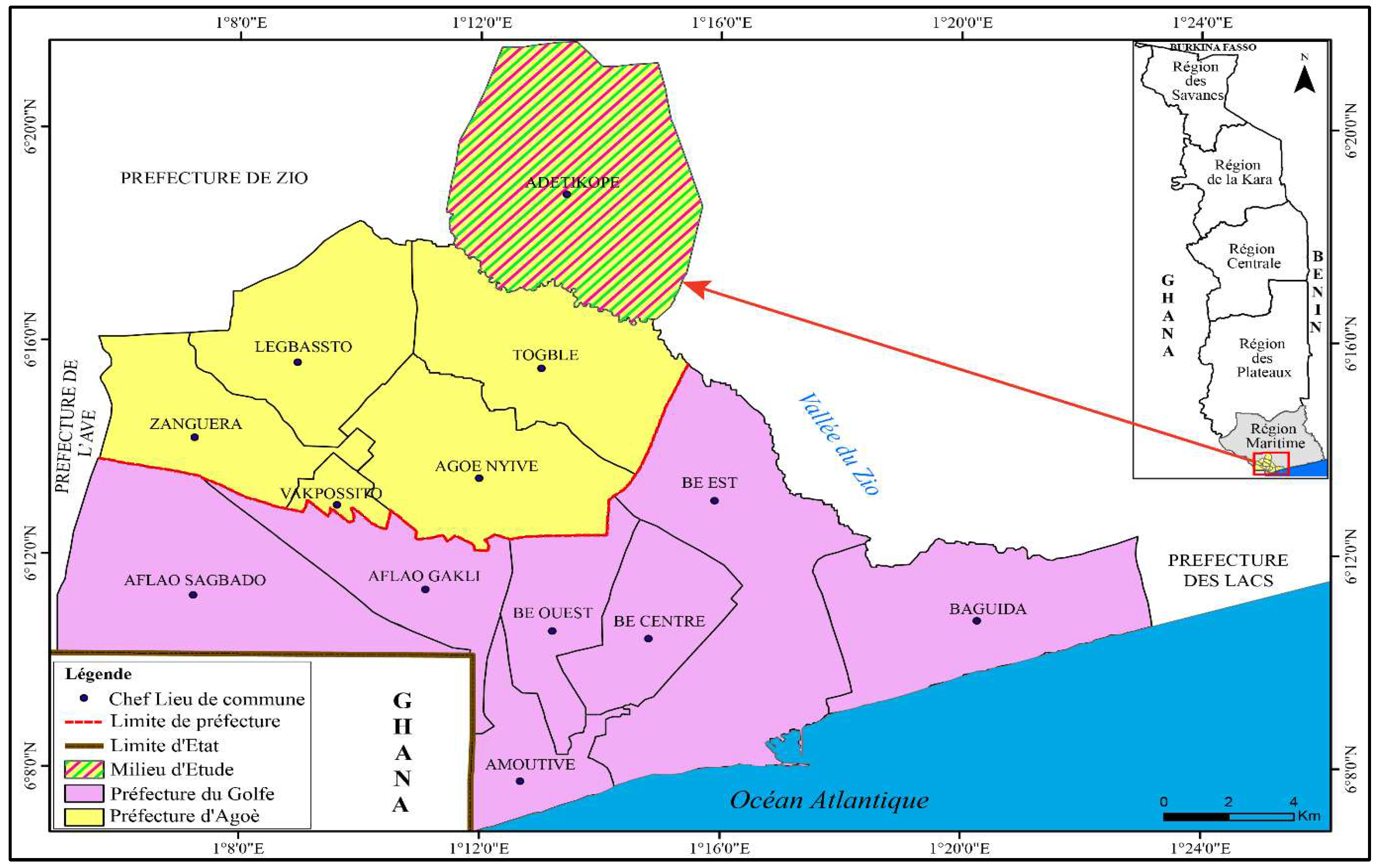

2.1.1. Geographical scope of the study

2.1.2. Scientific framework

2.2. Study material

2.3. Study methods

2.3.1. Type of study

2.3.2. Method used for data collection

2.3.3. Sampling

2.3.4. Data collection techniques and tools

2.3.5. Conduct of the survey

2.3.6. Data processing

2.4. Ethical aspects of research

2.5. Difficulties encountered

3. Results

3.1. Household solid and liquid waste management

| Indicators | Terms | % | P. Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbourhoods | Adétikopé Adoglové | 15.07% | < 0,05 |

| Adétikopé Agnavé | 21.92% | - | |

| Adétikopé Agotimé | 6.16% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Centre | 12.33% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Dévimé | 4.11% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Djové | 2.05% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Kladjémé | 6.85% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Agouté | 10.96% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Kpotavé | 5.48% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Lomenyo Kopé | 4.11% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Tonoukouti | 3.42% | < 0,001 | |

| Adétikopé Tsikponou Kondji | 7.53% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Gender | Female | 72.60% | - |

| Male | 27.40% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Age | ]0-20] | 0.68% | < 0,001 |

| ]20-30] | 19.98% | < 0,001 | |

| ]30-40] | 39.61% | - | |

| ]40-50] | 20.55% | < 0,001 | |

| ]50-60] | 15.75% | < 0,001 | |

| ]60-70] | 3.42% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Occupancy status | Rental | 30.14% | < 0,001 |

| Family properties | 16.44% | < 0,001 | |

| Personal properties | 53.42% | - | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Religions | Animist | 8.90% | < 0,001 |

| Christian | 70.55% | - | |

| Muslim | 20.55% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Level of education | Out of school | 9.59% | < 0,001 |

| Primary | 22.60% | < 0,001 | |

| Secondary | 64.38% | - | |

| University | 3.42% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% |

3.1. Household water supply

| Indicators | Terms and conditions | % | P. Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method of emptying the pit once it has been filled | Emptying truck | 5.48% | < 0,001 |

| Never emptied + don't know | 80.14% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 85.62% | ||

| Final treatment after emptying | Don't know | 99.20% | < 0,001 |

| Other | 0.80% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% | ||

| Places where latrines are not available | In the wild | 66.67% | < 0,001 |

| The neighbours | 14.28% | < 0,001 | |

| In a public toilet | 19.05% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% | ||

| Places where children's faeces are discharged | In a toilet | 14.38% | < 0,001 |

| In the wild | 85.62% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Observation of flooding in the concession during the rainy season | Yes | 12.33% | < 0,001 |

| No | 87.67% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Observing flooding in the neighbourhood | Yes | 11.64% | < 0,001 |

| No | 88.36% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Knowledge of what happens to the place where the lorries are deposited | Yes | 67.12% | < 0,001 |

| No | 32.88% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Condition of gutters | Bad | 0.68% | < 0,001 |

| Do not exist | 99.32% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% |

3.2. Household wastewater management

3.3. Knowledge of wastewater management

3.3.1. Raising awareness of sanitation issues in the hygiene department

3.3.2. Interview with the head of the basic hygiene and sanitation department

3.3.3. Interview with the head of the town hall's technical division

3.3.4. Interview with the head of the village development committee

3.3.5. Interview with the town hall councillor

3.3.6. Observation grid for the general environment of the village

4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attar, M. Les Enjeux de La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers et Assimilés En France En 2008; Direction des Journaux Officiels, 2008.

- Koné-Bodou Possilétya, J.; Kouamé, V.K.; Fé Doukouré, C.; Yapi, D.A.C.; Kouadio, A.S.; Ballo, Z.; Sanogo, T.A. Risques sanitaires liés aux déchets ménagers sur la population d’Anyama (Abidjan-Côte d’Ivoire). VertigO - Rev. Électronique En Sci. Environ. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Diabagate, S.; konan, kouamé P. Gestion Des Ordures Ménagères Dans La Ville de Bouaké, Sources d’inégalités Socio-Spatiales et Environnementales. Rev. Espace Territ. Sociétés Santé 2018, 1, 126–142.

- abbari, K.; A.Najih; Amir, S.; A.Agbalou GESTION DES DECHETS MENAGERS DANS LA VILLE DE KHOURIBGA (MAROC) : ETUDE DU COMPORTEMENT DU CITOYEN. ScienceLib 2014, 6.

- Gbekley, E.H.; Kouawo, A.C.A.; Awokou, K. L’éducation Relative à l’environnement (ERE) Au Togo : Evaluation Du Paradigme de Formation 2021.

- Kondoh, E.; Bodjona, M.B.; Aziable, E.; Tchegueni, S.; Kili, K.A.; Tchangbedji, G. Etat Des Lieux de La Gestion Des Déchets Dans Le Grand Lomé. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 2200–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JICA Projet d’Assainissement Des Eaux Usées, Des Eaux Pluviales et Des Déchets Solides de La Ville de Kaolack En République Du Sénégal. CTI Engineering International - Recherche Google Available online: https://www.google.com/search?hl=fr&q=Projet+d%27Assainissement+des+Eaux+Us%C3%A9es,+des+Eaux+Pluviales+et+des+D%C3%A9chets+Solides+de+la+ville+de+Kaolack+en+R%C3%A9publique+du+S%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.+CTI+Engineering+International (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Silva, J.A. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [CrossRef]

- DGSNC Ministère Auprès Du Président de La République, Chargé de La Planification, Du Développement et de l’aménagement Du Territoire. Available online: https://planification.gouv.tg/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- QUIBB; MPDAT-DGSCN République Togolaise, Rapport Enquête QUIBB; 2015;

- Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Forestières du Togo. Loi No 2008-005 Du 30 Mai 2008 Portant Loi-Cadre Sur l’environnement.; 2008; p. 37;

- MSHPAUS Politique Nationale de Santé, Togo Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/fr/publications/politique-nationale-de-sante-togo (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- inistère de l’Urbanisme, de l’Habitat et du Cadre de Vie de la République Togolaise. Elaboration Du Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme (SDAU) Du Grand Lomé. 2018. 15p. Available online: https://urbanisme.gouv.tg/le-ministere-de-lurbanisme-de-lhabitat-et-de-la-reforme-fonciere-a-dote-quarante-huit-48-communes-et-le-treize-13-du-grand-lome-de-schemas-directeurs-damenagement/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Robert Magnani et echantillonage Guide d’Echantillonnage Available online: https://www.bing.com:9943/search?q=Robert+Magnani+et+echantillonage&form=ANNTH1&refig=3da28ced7efe4ade9bda7c66ea89acac (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Guidi, A. Disponibilité de l’eau Potable et Santé Des Populations de La Localité d’Adétikopé. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux, 2020.

- Titone, B. Etat Des Lieux de La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers Solides et Liquides Dans La Commune Agou1 de La Préfecture d’Agou : Cas de La Ville de Gadzépé. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2020.

- Tchakou, T. Etat Des Lieux de l’assainissement Dans La Commune Vo3. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2022.

- Dinégré, M. Etat Des Lieux de l’assainissement de l’hygiène et de l’approvisionnement En Eau Potable de La Commune de Notsè. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2016.

- Nyakpo, A. Etat Des Lieux de La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers Solides et Liquides Dans La Commune Agou1 de La Préfecture d’Agou : Cas de La Ville de Gadzépé. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2022.

- Awou, K. Contribution à l’amélioration de La Gestion Des Excréta et Eaux Usées Dans La Ville de Kpalimé. Mémoire de Technicien Supérieur en Génie Sanitaireé, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2011.

- Kpizou Etat Des Lieux de La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers Dans La Commune d’Agoé Nyivé 6 : Cas de La Localité d’Adétikopé Centre. , Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2022.

- Tchindou, P. Etude Diagnostique de La Gestion Des Boues de Vidange Dans La Ville de Tsévié Au Togo. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2019.

- Ali, A. Problématique de l’assainissement Au Togo : Cas Du Quartier Haoussa- Zongo/Togblékopé Dans La Préfecture Du Golfe. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux: Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2014.

- Mukuku, O.; Musung, J.; Samba, C.; Tshibanda, K.; Zalula, C.; Bamba, M.; Luboya, N. Évaluation de La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers Dans La Commune de Katuba à Lubumbashi (République Démocratique Du Congo). Rev. Infirm. Congo. 2018, 2, 50–56.

- Ahatefou, E.L.; Koriko, M.; Koledzi, K.E.; Tchegueni, S.; Tchangbédji, G.; Hafidi, M. Diagnostic Du Système de Collecte Des Excréta et Eaux Usées Domestiques Dans Les Milieux Inondables de La Ville de Lomé: Cas Du Quartier Zogbedji. Déchets Sci. Tech. 2013, 65, 12–19.

- Gabert, J. Mémento de l’assainissement; éditions Quae, 2018.

- PEA-OMD Guide Opérationnel de l’Assainissement Autonome Des Excréta et Eaux Usées Au Togo. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=PEA-OMD.+%282016%29.+Guide+Op%C3%A9rationnel+de+l%E2%80%99Assainissement+Autonome+des+Excr%C3%A9ta+et+Eaux+Us%C3%A9es+au+Togo.+161p&qs=n&form=QBRE&sp=-1&pq=porno&sc=1-5&sk=&cvid=86806E52E1754318A0A49456CBFFBC9B&ghsh=0&ghacc=0&ghpl= (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Attisso, A. Etude Diagnostique de La Gestion Des Déchets Solides et Liquides Dans La Commune de Bassar. Région de La Kara. Mémoire de master santé environnementale spécialité eau et assainissement, Université de Lomé, Ecole des Assistants Médicaux, 2015.

- Gui, Z.; Wen, J.; Fu, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, B. Analysis on Mode and Benefit of Resource Utilization of Rural Sewage in a Typical Chinese City. Water 2023, 15, 2062. [CrossRef]

| 12 Villages of Adétikopé | Number of men | Number of women | Total | Total households surveyed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADETIKOPE-CENTRE | 8 708 | 9 325 | 18 033 | 1128 |

| AGNAVE | 3 625 | 3 687 | 7 312 | 458 |

| DEVIME | 5 098 | 5 447 | 10 545 | 660 |

| DZOVE | 3 104 | 3 098 | 6 202 | 388 |

| ADOGLOVE | 2 134 | 2 169 | 4 303 | 269 |

| LOMENYO KOPE | 2 075 | 2 120 | 4 195 | 263 |

| KPOKPOME-AGUTE | 13 608 | 14 385 | 27 993 | 1752 |

| AGOTIME | 1 923 | 1 901 | 3 824 | 239 |

| KLADJEME | 4 253 | 4 371 | 8 624 | 540 |

| KPOTAVE | 5 432 | 5 632 | 11 064 | 693 |

| TONOUKOUTI | 2 396 | 2 466 | 4 862 | 304 |

| TSIKPLONOU-KONDJI | 1 554 | 1 683 | 3 237 | 203 |

| TOTAL COMMUNE AGOE-NYIVE 6 | 53 910 | 56 284 | 110 194 | 6898 |

| Technical | Tools | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Observation | Observation grid | General neighbourhood environment Household environment |

| Maintenance | Interview guide | Head of the town hall's technical division Head of the CMS hygiene and sanitation department Head of CDV Town councillor and secretary |

| Questionnaire survey | Questionnaire | Head of household/representative |

| Literature review | Tabulation sheet | Consultation register, scientific websites |

| Indicators | Terms | % | P. Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main occupation of head of household | Farmer | 8.90% | < 0,05 |

| Artisan | 17.12% | < 0,05 | |

| Car / Motorcycle Taxi Driver | 0.68% | < 0,001 | |

| Retailer | 29.45% | - | |

| Housekeeper | 24.66% | < 0,05 | |

| Retailer | 8.90% | < 0,001 | |

| Employee | 8.90% | < 0,001 | |

| Other | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Average household sizeMode | M-1 | 2.05% | < 0,001 |

| M-2 | 4.79% | < 0,001 | |

| M-3 | 13.01% | < 0,06 | |

| M-4 | 19.86% | < 0,09 | |

| M-5 | 10.27% | < 0,001 | |

| M-6 | 20.66% | - | |

| M-7 | 10.33% | < 0,05 | |

| M-8 | 9.65% | < 0,05 | |

| M-9 | 5.54% | < 0,05 | |

| M-10 | 2.11% | < 0,001 | |

| M-11 | 0.06% | < 0,001 | |

| M-12 | 0.06% | < 0,001 | |

| M-13 | 0.06% | < 0,001 | |

| M-14 | 0.06% | < 0,001 | |

| M-15 | 0.06% | < 0,001 | |

| M-16 | 0.34% | < 0,001 | |

| M-20 | 0.29% | < 0,001 | |

| M-24 | 0.40% | < 0,001 | |

| M-32 | 0.40% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% |

| Indicators | Terms | % | P. values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main source of drinking water | TDE* (Togolese of the waters) only | 6.16% | < 0,001 |

| TDE and drilling | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| Drilling only | 74.66% | - | |

| Drilling and wells | 9.59% | < 0,001 | |

| Well only | 6.85% | < 0,001 | |

| Wells and TDE | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Use made of water TDE | Drinks and Cooking | 2.05% | < 0,001 |

| Shower and laundry | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| All | 5.48% | < 0,001 | |

| Do not use | 91.10% | - | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Water used for drinking | Conditioned water | 8.90% | < 0,001 |

| Borehole water | 80.14% | - | |

| Well water | 4.11% | < 0,001 | |

| TDE water | 6.85% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Water used for cooking | Drilling | 72.60% | - |

| Drilling and wells | 3.42% | < 0,001 | |

| Well | 15.07% | < 0,001 | |

| TDE water | 8.90% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Water used for showering | Drilling | 70.55% | - |

| Well | 21.92% | < 0,001 | |

| TDE | 7.53% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| TDE water source | TDE subscriber | 93.38% | - |

| Fountain bollard | 6.62% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Satisfaction with TDE services | Satisfied | 23.08% | < 0,05 |

| Not very satisfied | 30.77% | < 0,05 | |

| Not satisfied | 38.46% | - | |

| Does not wish to express | 7.69% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% |

| Indicators | Terms and conditions | % | P. Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge points for kitchen water | In the courtyard of the house | 6.16% | < 0,001 |

| In a sump | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| On the public highway | 78.77% | - | |

| On an undeveloped plot | 13.70% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Discharge points for washing water | In the courtyard of the house | 8.90% | < 0,001 |

| On the public highway | 78.77% | - | |

| On an undeveloped plot | 12.33% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Drainage / discharge of waste water | Septic tank | 58.22% | - |

| On the public highway | 6.16% | < 0,001 | |

| On an undeveloped plot | 32.19% | < 0,001 | |

| In a sump | 3.42% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Existence of latrines in the concession | Yes | 85.62% | - |

| No | 14.38% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | ||

| Types of latrines | Traditional pit | 54.40% | - |

| VIP (Ventilated Improvised Pit) latrines | 30.47% | < 0,001 | |

| Manual flush toilet (TCM) | 15.13% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% | ||

| Condition of latrines | Good | 93.60% | - |

| Acceptable | 4.00% | < 0,001 | |

| Bad | 2.40% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% | ||

| Frequency of toilet / latrine maintenance | Twice a month | 68.00% | - |

| Once (1) a month | 0.80% | < 0,001 | |

| Once (1) a week | 31.20% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% | ||

| Frequency of latrine emptying | 1 time every 3 years | 2.40% | < 0,001 |

| 1 time every 2 years | 3.20% | < 0,001 | |

| Once a year | 1.60% | < 0,001 | |

| Never | 66.40% | - | |

| Don't know | 26.40% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100% |

| Indicators | Terms and conditions | % | Capital gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of wastewater management | Yes | 58.22% | < 0,001 |

| No | 41.78% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 100.00% | < 0,001 | |

| Information channel on wastewater management knowledge | Media | 56.22% | < 0,001 |

| Rue | 2.00% | < 0,001 | |

| NA | 43.15% | < 0,001 | |

| Total | 101.37% | < 0,001 | |

| Knowledge of wastewater reclamation | Yes | 62.33% | < 0,001 |

| No | 36.30% | < 0,001 | |

| No answer | 1.37% | < 0,001 | |

| 100.00% | < 0,001 | ||

| Knowledge of the health hazards of waste water | Yes | 96.58% | < 0,001 |

| No | 2.74% | < 0,001 | |

| No answer | 0.68% | < 0,001 | |

| 100.00% | < 0,001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).