Submitted:

25 July 2023

Posted:

27 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

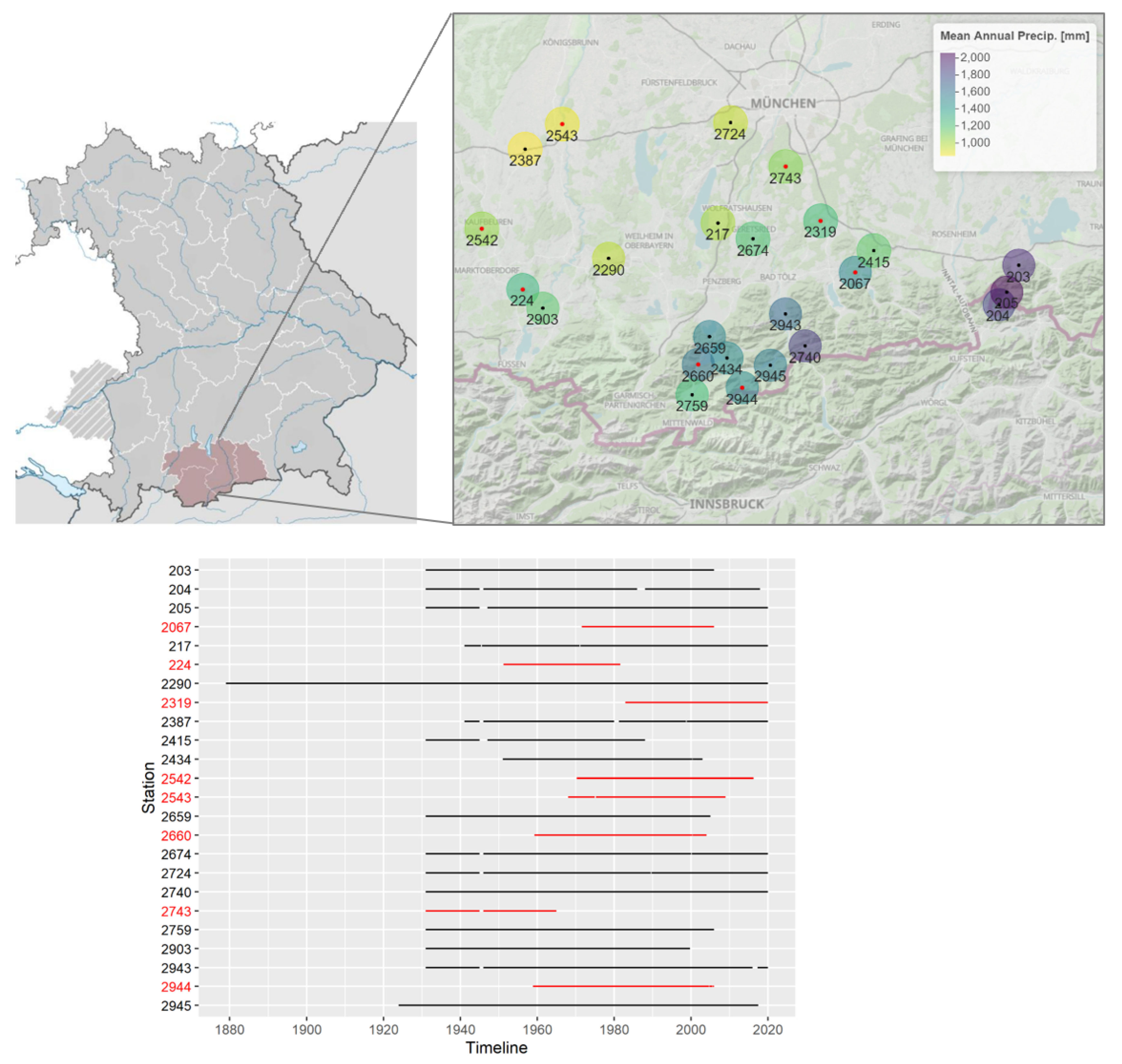

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Data

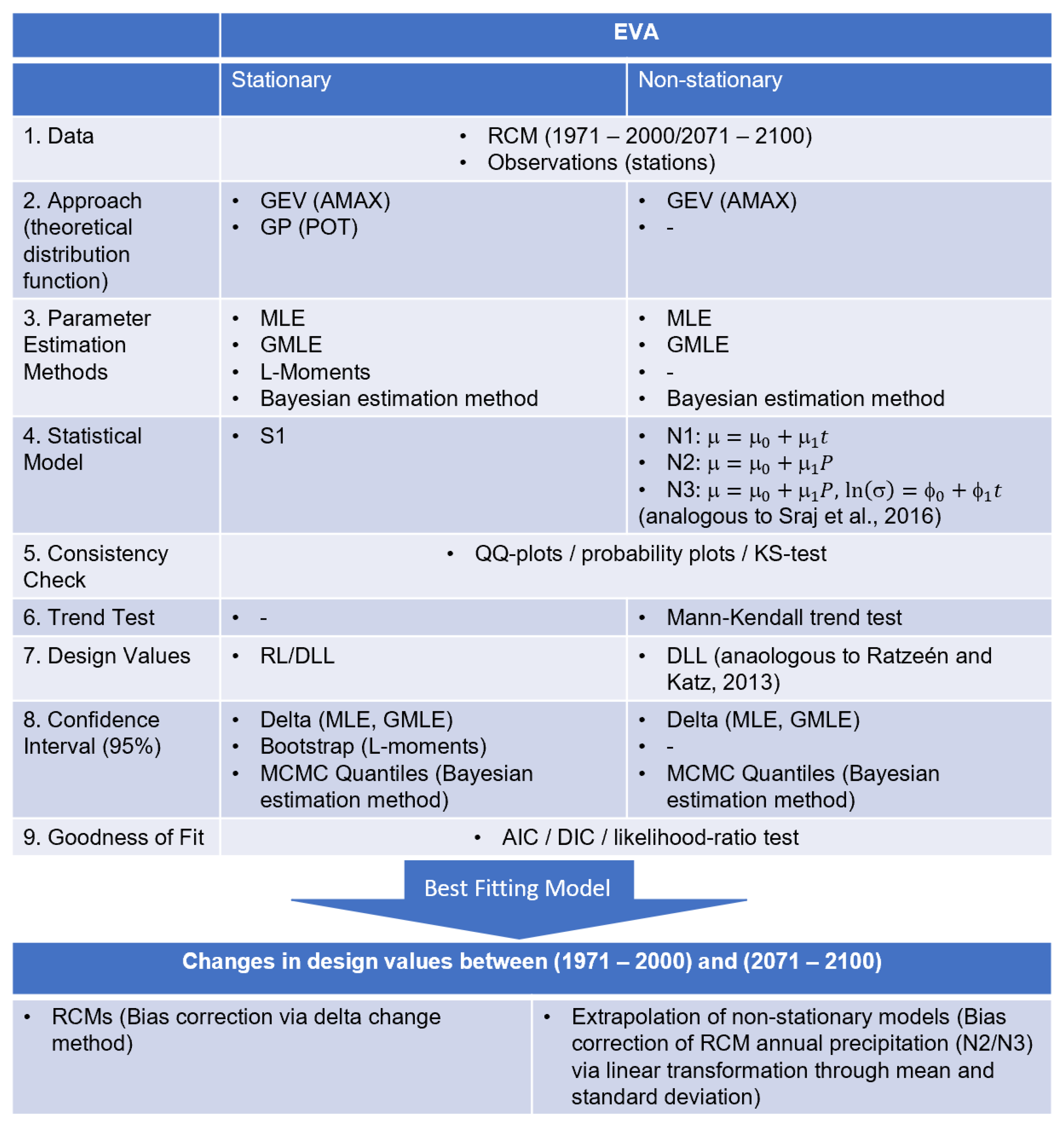

2.3. Methods Applied for Extreme Value Analysis (EVA)

2.3.1. Theoretical Extreme Distribution Functions

2.3.2. Parameter Estimation Methods

2.3.3. Implementation of Non-Stationarity

- 1.

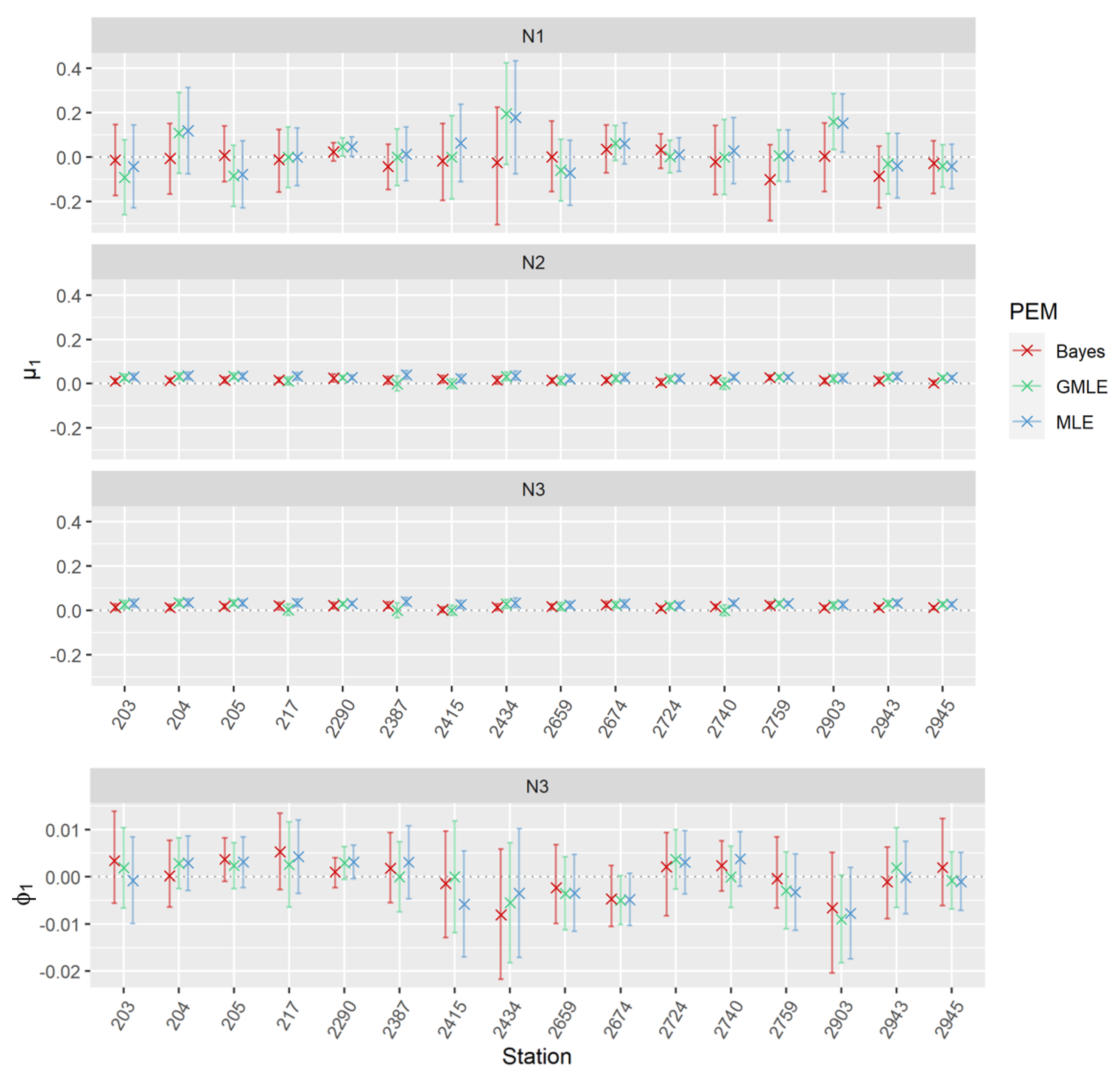

- N1: non-stationary model (1) with location parameter being a function of time: (t) = + t

- 2.

- N2: non-stationary model (2) with location parameter being a function of annual precipitation: (t) = + P

- 3.

- N3: non-stationary model (3) with location parameter being a function of annual precipitation and parameter being a function of time: (t) = + P, ln((t)) = + t

2.3.4. Equivalent Design Life Level

2.3.5. Usage of Regional Climate Models

3. Results

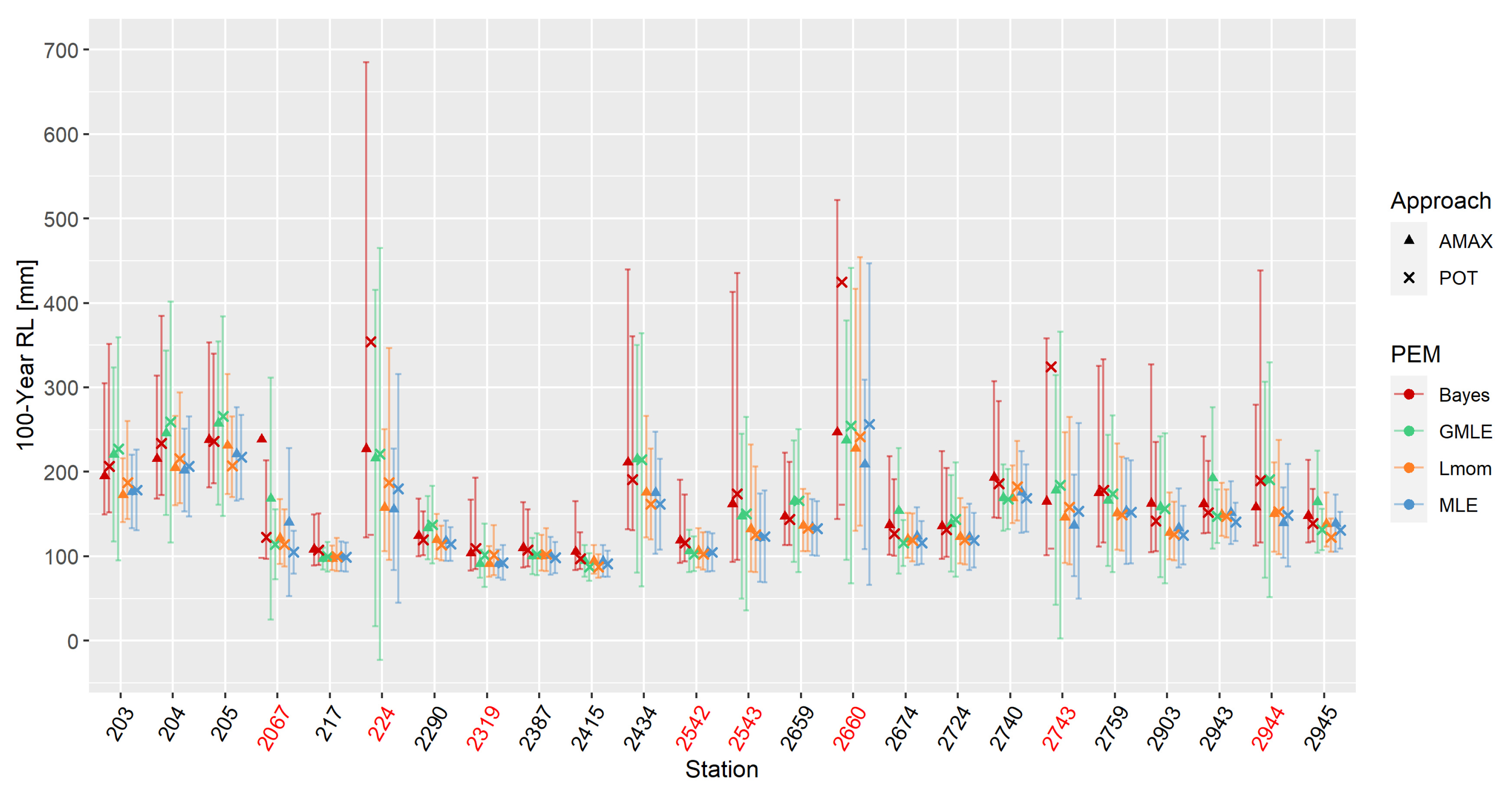

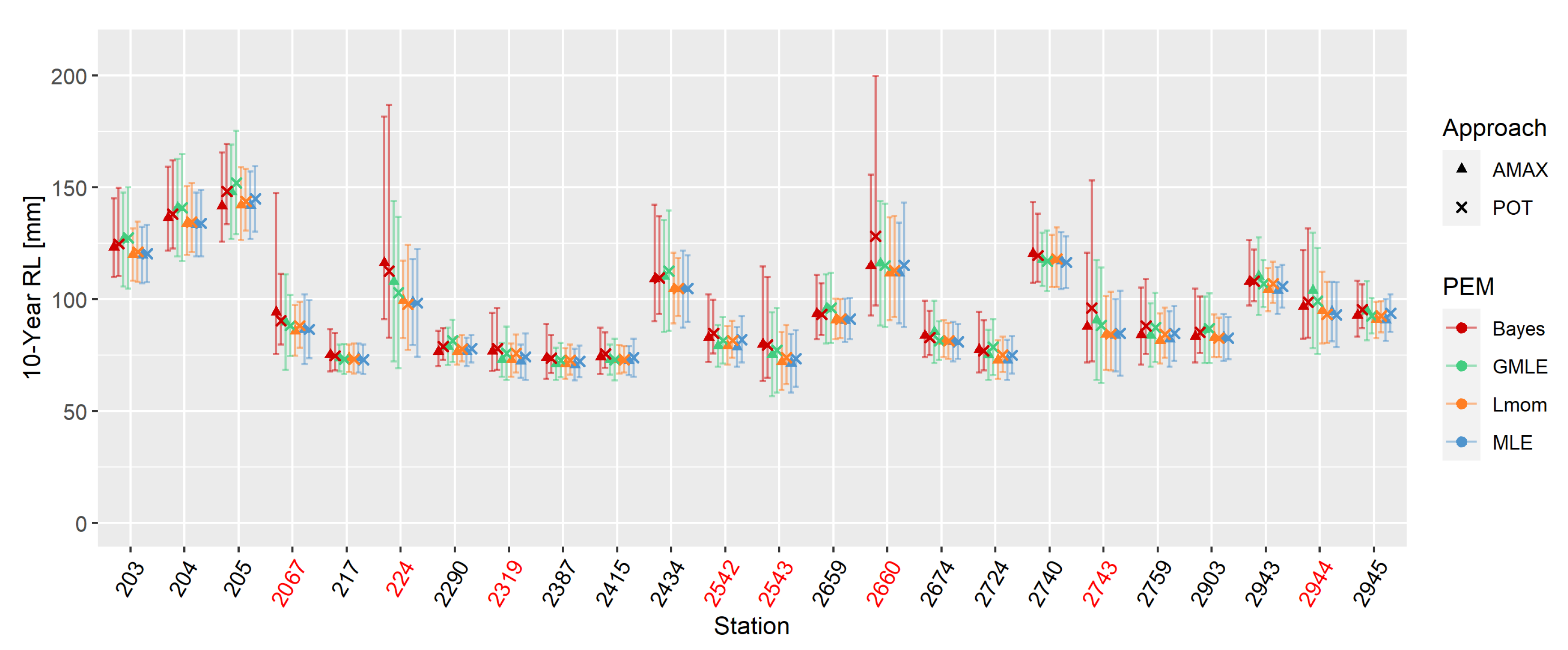

3.1. Theoretical Distributions and Parameter Estimation Methods

3.2. Justification and Evaluation of Non-Stationary EVA

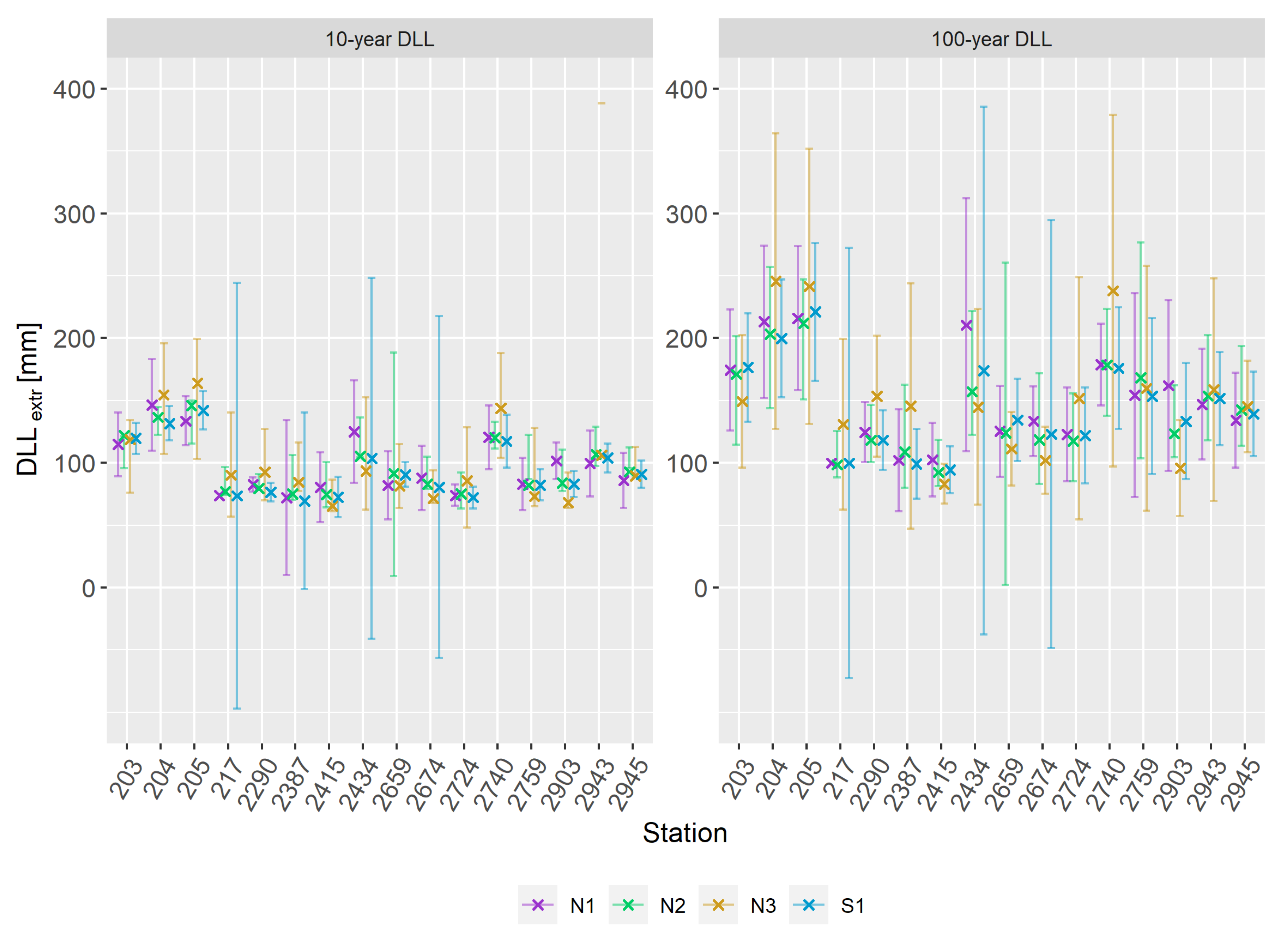

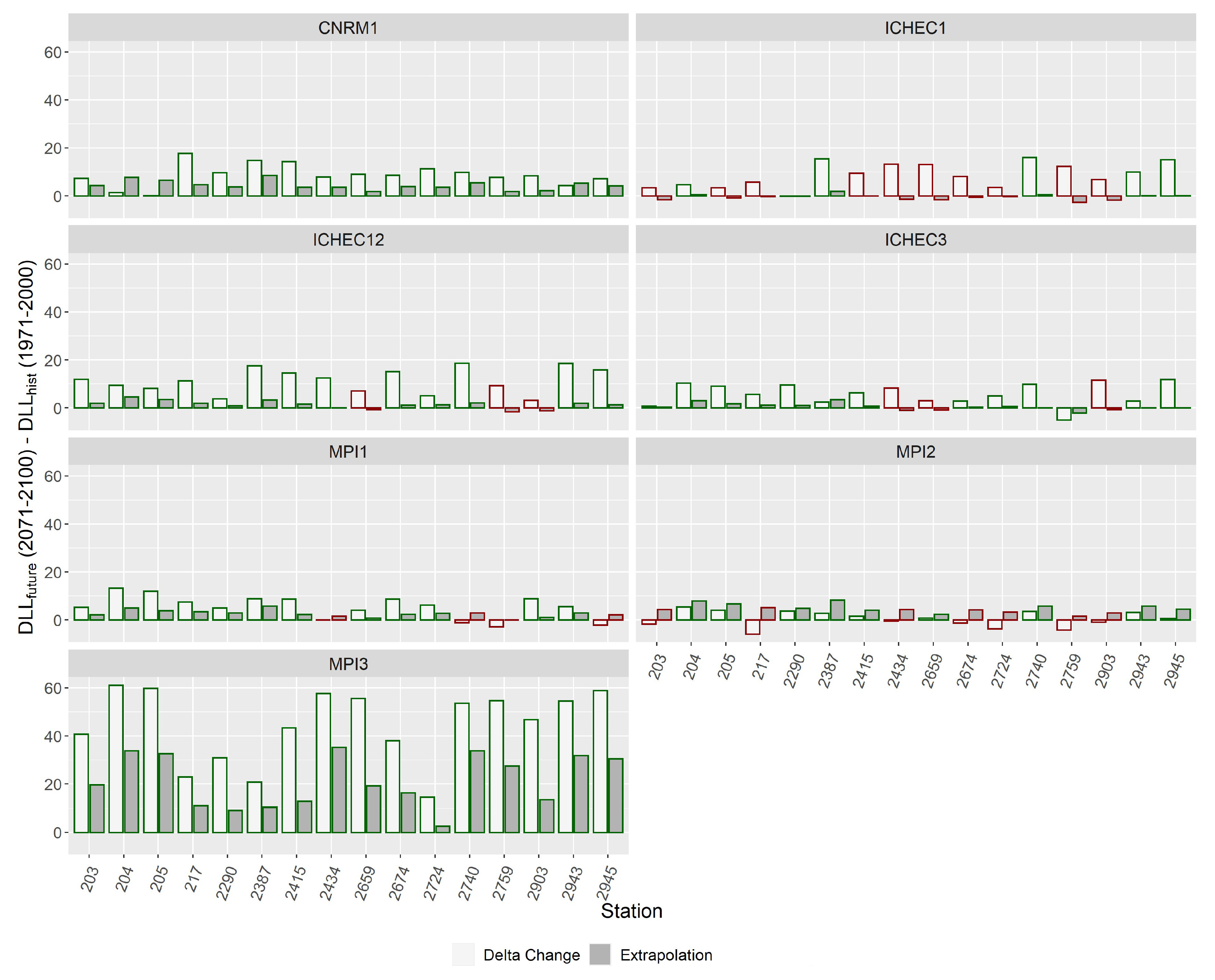

3.3. Changes in Design Life Levels

3.3.1. Extrapolation of Non-Stationary Models

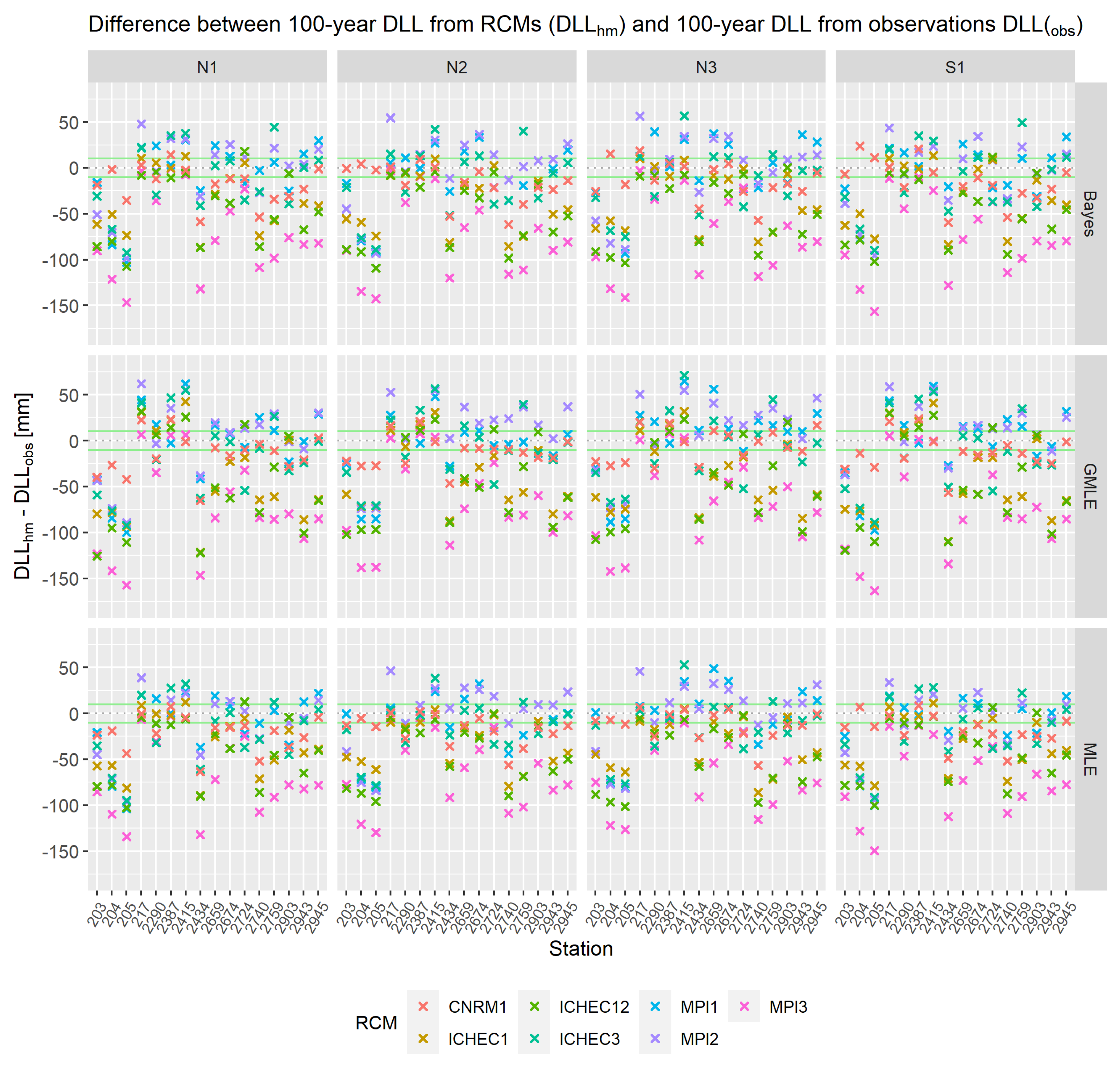

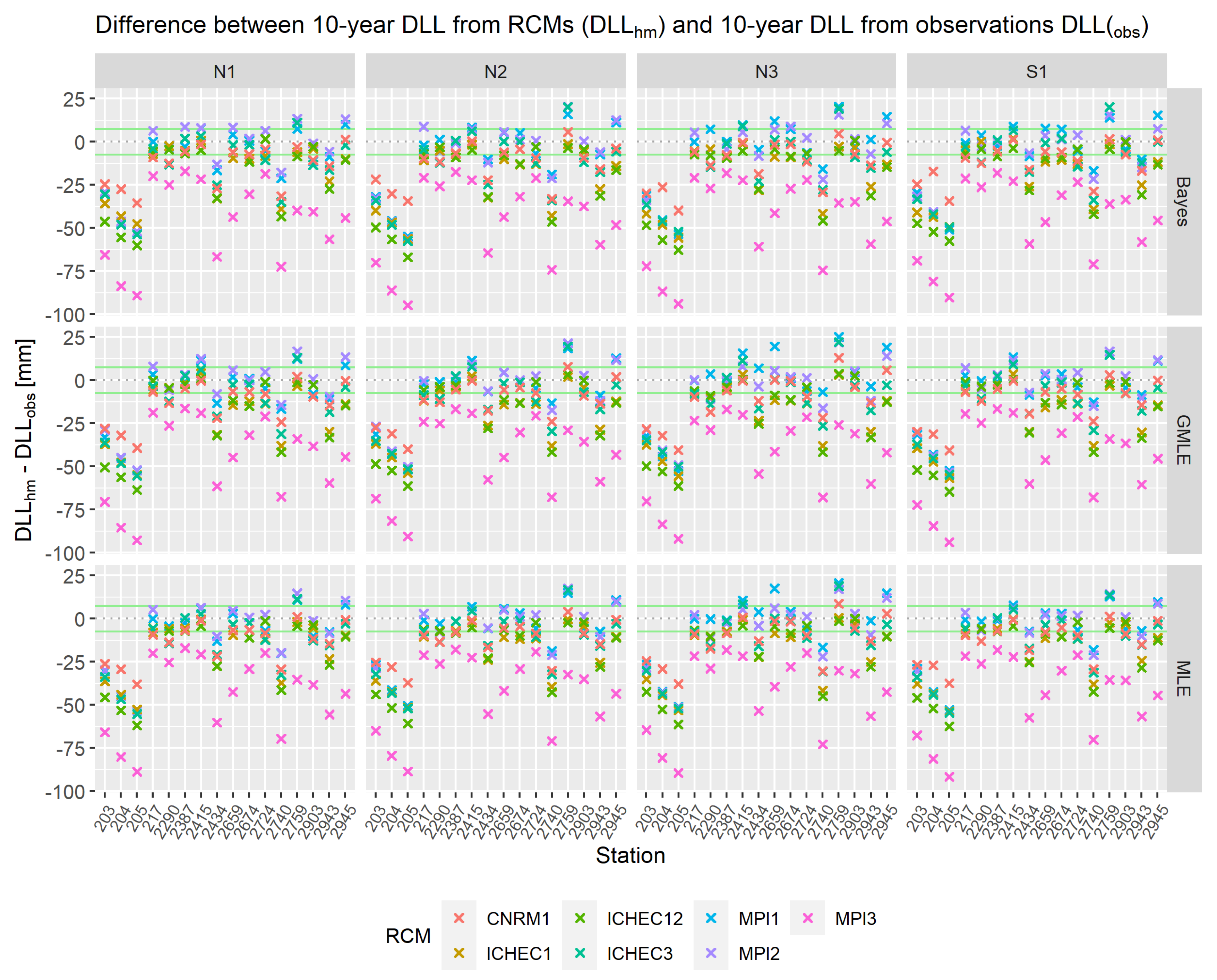

3.3.2. Non-Stationary EVA Using Regional Climate Model Output

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swiss Re. Natural catastrophes in 2021: the floodgates are open. Technical report, 2022.

- Junghänel, T.; Bissolli, P.; Daßler, J.; Fleckenstein, R.; Imbery, F.; Janssen, W.; Kaspar, F.; Lengfeld, K.; Leppelt, T.; Rauthe, M.; et al. Hydro-klimatologische Einordnung der Stark-und Dauerniederschläge in Teilen Deutschlands im Zusammenhang mit dem Tiefdruckgebiet "Bernd" vom 12. bis 19. Juli 2021. Technical report, Deutscher Wetterdienst, 2021.

- Lehmkuhl, F.; Schüttrumpf, H.; Schwarzbauer, J.; Brüll, C.; Dietze, M.; Letmathe, P.; Völker, C.; Hollert, H. Assessment of the 2021 summer flood in Central Europe. Environmental Sciences Europe 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors Sarah, L..; Péan Clotilde.; Chen Yang.; Goldfarb Leah.; Gomis Melissa I.; Matthews J.B. Robin.; Berger Sophie.; et al. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–32. [CrossRef]

- Pörtner Hans-Otto.; Roberts Debra C..; Tignor Melinda M. B..; Poloczanska Elvira.; Mintenbeck Katja.; Alegría Andrés.; Craig Marlies.; Langsdorf Stefanie.; Löschke Sina.; Möller Vincent.; et al., Eds. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Madakumbura, G.D.; Thackeray, C.W.; Norris, J.; Goldenson, N.; Hall, A. Anthropogenic influence on extreme precipitation over global land areas seen in multiple observational datasets. Nature Communications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinkova, M.; Kysely, J. Overview of observed clausius-clapeyron scaling of extreme precipitation in midlatitudes. Atmosphere 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingman, S.L. Physical Hydrology; Waveland Press, Incorporated, 2015.

- Salas, J.D.; Obeysekera, J.; Vogel, R.M. Techniques for assessing water infrastructure for nonstationary extreme events: a review. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2018, 63, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.J.; Anderson, B.; Buechel, M.; Dadson, S.; Han, S.; Harrigan, S.; Kelder, T.; Kowal, K.; Lees, T.; Matthews, T.; et al. Nonstationary weather and water extremes: A review of methods for their detection, attribution, and management, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values; Springer Series in Statistics, Springer, 2001.

- Villarini, G.; Smith, J.A.; Serinaldi, F.; Bales, J.; Bates, P.D.; Krajewski, W.F. Flood frequency analysis for nonstationary annual peak records in an urban drainage basin. Advances in Water Resources 2009, 32, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Jia, S.; Mahmood, R.; Yan, J.; Ahsan, M. Non-Stationary Bayesian Modeling of Annual Maximum Floods in a Changing Environment and Implications for Flood Management in the Kabul River Basin, Pakistan. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, D.; Laux, P.; Heckl, A.; Schindler, M.; Kunstmann, H. Near surface roughness estimation : A parameterization derived from artificial rainfall experiments and two-dimensional hydrodynamic modelling for multiple vegetation coverages. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 617, 128786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarini Gabriele.; Taylor Susan.; Wobus Cameron.; Vogel Richard.; Hecht Jory.; White Kathleen.; Baker Bryan.; Gilroy Kristin.; Olsen J. Rolf.; Raff David. Floods and Nonstationarity: A Review. Technical report, CWTS 2018-01, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC., 2018.

- Wunsch, C. The Interpretation of Short Climate Records, with Comments on the North Atlantic and Southern Oscillations. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 1999, 80, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Climate change, the Hurst phenomenon, and hydrological statistics. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2003, 48, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalas, N.C. Comment on the Announced Death of Stationarity. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2012, 138, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, M. Nonstationarity of Hydrological Records and Recent Trends in Trend Analysis: A State-of-the-art Review. Environmental Processes 2015, 2, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Montanari, A. Negligent killing of scientific concepts: the stationary case. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2015, 60, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinaldi, F.; Kilsby, C.G. Stationarity is undead: Uncertainty dominates the distribution of extremes. Advances in Water Resources 2015, 77, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.D.; Obeysekera, J. Revisiting the Concepts of Return Period and Risk for Nonstationary Hydrologic Extreme Events. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2014, 19, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, D. Return Periods and Return Levels Under Climate Change. In Extremes in a Changing Climate: Detection, Analysis and Uncertainty; AghaKouchak, A., Easterling, D., Hsu, K., Schubert, S., Sorooshian, S., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rootzén, H.; Katz, R.W. Design Life Level: Quantifying risk in a changing climate. Water Resources Research 2013, 49, 5964–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Singh, V.P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Wang, H. Concept of Equivalent Reliability for Estimating the Design Flood under Non-stationary Conditions. Water Resources Management 2018, 32, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeis, S. Analysis of decadal precipitation changes at the northern edge of the alps. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2021, 30, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, K.M.; Ulbrich, U.; Leckebusch, G.C. Vb cyclones and associated rainfall extremes over central Europe under present day and climate change conditions. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peristeri, M.; Ulrich, W.; Smith, R.K. Genesis conditions for thunderstorm growth and the development of a squall line in the northern Alpine foreland. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics 2000, 72, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Nonstationarity versus scaling in hydrology. Journal of Hydrology 2006, 324, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Jones, C.; Asrar, G.R. Addressing climate information needs at the regional level: the CORDEX framework. WMO Bulletin 2009, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, D.; Petersen, J.; Eggert, B.; Alias, A.; Christensen, O.B.; Bouwer, L.M.; Braun, A.; Colette, A.; Déqué, M.; Georgievski, G.; et al. EURO-CORDEX: New high-resolution climate change projections for European impact research. Regional Environmental Change 2014, 14, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, G.; Viola, F.; Deidda, R. Evaluation of Precipitation From EURO-CORDEX Regional Climate Simulations in a Small-Scale Mediterranean Site. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2018, 123, 1604–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgetta, M.A.; Jungclaus, J.; Reick, C.H.; Legutke, S.; Bader, J.; Böttinger, M.; Brovkin, V.; Crueger, T.; Esch, M.; Fieg, K.; et al. Climate and carbon cycle changes from 1850 to 2100 in MPI-ESM simulations for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2013, 5, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, P.; Mckinstry, A. EC-Earth Global Climate Simulations-Ireland’s Contributions to CMIP6. Technical report, Environmental Protection Agency, 2020.

- Laux, P.; Rötter, R.P.; Webber, H.; Dieng, D.; Rahimi, J.; Wei, J.; Faye, B.; Srivastana, A.; Bliefernicht, J.; Adeyeri, O.; et al. To bias correct or not to bias correct ? An agricultural impact modelers’ perspective on regional climate model data. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 304–305, 108406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.; Tawn, J. Bayesian Inference for Extremes: Accounting for the Three Extremal Types; Springer Science + Business Media, Inc. Manufactured in The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 291–307.

- Jenkinson, A.F. The frequency distribution of the annual maximum (or minimum) values of meteorological elements. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 1955, 81, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; AghaKouchak, A.; Gilleland, E.; Katz, R.W. Non-stationary extreme value analysis in a changing climate. Climatic Change 2014, 127, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, S.; Valdés, J.B.; Steinschneider, S.; Kim, T.W. Non-stationary frequency analysis of extreme precipitation in South Korea using peaks-over-threshold and annual maxima. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2016, 30, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.S.; Stedinger, J.R. Generalized maximum likelihood Pareto-Poisson estimators for partial duration series. Water Resources Research 2001, 37, 2551–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickands, J. Statistical Inference Using Extreme Order Statistics. Source: The Annals of Statistics 1975, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleland, E.; Katz, R.W. ExtRemes 2.0: An extreme value analysis package in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2016, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarrott, C.; Macdonald, A. A Review of Extreme Value Threshold Estimation And Uncertainty Quantification. REVSTAT-Statistical Journal 2012, 10, 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Beirlant, J.; Goegebeur Yuri.; Teugels Jozef.; Segers Johan.; De Waal Daniel.; Ferro Chris. Statistics of extremes: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, 2004.

- Anagnostopoulou, C.; Tolika, K. Extreme precipitation in Europe: Statistical threshold selection based on climatological criteria. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2012, 107, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.S.; Stedinger, J.R. Bayesian MCMC flood frequency analysis with historical information. Journal of Hydrology 2005, 313, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.W.; Parlange, M.B.; Naveau, P. Statistics of extremes in hydrology. Advances in Water Resources 2002, 25, 1287–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S.G.; Dixon, M.J. Likelihood-Based Inference for Extreme Value Models. Extremes 1999, 2, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, J.R.M.; Wallis, J.R. Parameter and Quantile Estimation for the Generalized Pareto Distribution. Technometrics 1987, 29, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, J.R.M. L-Moments: Analysis and Estimation of Distributions using Linear Combinations of Order Statistics. Source: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1990, 52, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.S.; Stedinger, J.R. Generalized maximum-likelihood generalized extreme-value quantile estimators for hydrologic data. Water Resources Research 2000, 36, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šraj, M.; Viglione, A.; Parajka, J.; Blöschl, G. The influence of non-stationarity in extreme hydrological events on flood frequency estimation. Journal of Hydrology and Hydromechanics 2016, 64, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.W. Statistical Methods for Nonstationary Extremes. In Extremes in a Changing Climate: Detection, Analysis and Uncertainty; AghaKouchak, A., Easterling, D., Hsu, K., Schubert, S., Sorooshian, S., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.E.; Neath, A.A. The Akaike information criterion: Background, derivation, properties, application, interpretation, and refinements. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, E.; Osborne, T.M.; Ho, C.K.; Challinor, A.J. Calibration and bias correction of climate projections for crop modelling: An idealised case study over Europe. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2013, 170, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Racines, C.; Tarapues, J.; Thornton, P.; Jarvis, A.; Ramirez-Villegas, J. High-resolution and bias-corrected CMIP5 projections for climate change impact assessments. Scientific Data 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Q.; Laux, P.; Kunstmann, H. Future high- and low-flow estimations for Central Vietnam: a hydro-meteorological modelling chain approach. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2017, 62, 1867–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutschbein, C.; Seibert, J. Bias correction of regional climate model simulations for hydrological climate-change impact studies: Review and evaluation of different methods. Journal of Hydrology 2012, 456-457, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Christoph.; Voigt, M.; Iber, C.; Sauer, T. Starkniederschläge: Entwicklung in Vergangenheit und Zukunft. Technical report, KLIWA, 2019.

- Coles, S.G.; Powell, E.A. Bayesian Methods in Extreme Value Modelling: A Review and New Developments. International Statistical Review / Revue Internationale de Statistique 1996, 64, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengfeld, K.; Kirstetter, P.E.; Fowler, H.J.; Yu, J.; Becker, A.; Flamig, Z.; Gourley, J. Use of radar data for characterizing extreme precipitation at fine scales and short durations. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junghänel, T.; Ertel, H.; Deutschländer, T.; Wetterdienst, D.; Hydrometeorologie, A. Bericht zur Revision der koordinierten Starkregenregionalisierung und-auswertung des Deutschen Wetterdienstes in der Version 2010. Technical report, 2017.

- Poschlod, B.; Ludwig, R.; Sillmann, J. Return levels of sub-daily extreme precipitation over Europe. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2020, pp. 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Maity, R.; Suman, M.; Laux, P.; Kunstmann, H. Bias correction of zero-inflated RCM precipitation fields: A copula-based scheme for both mean and extreme conditions. Journal of Hydrometeorology 2019, 20, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warscher, M.; Wagner, S.; Marke, T.; Laux, P.; Smiatek, G.; Strasser, U.; Kunstmann, H. A 5 km resolution regional climate simulation for Central Europe: Performance in high mountain areas and seasonal, regional and elevation-dependent variations. Atmosphere 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.; Schmidli, J.; Schär, C. Heavy precipitation in a changing climate: Does short-term summer precipitation increase faster? Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; Kainuma, M.; Riahi, K.; Thomson, A.; Hibbard, K.; Hurtt, G.C.; Kram, T.; Krey, V.; Lamarque, J.F.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Climatic Change 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyselý, J.; Rulfová, Z.; Farda, A.; Hanel, M. Convective and stratiform precipitation characteristics in an ensemble of regional climate model simulations. Climate Dynamics 2016, 46, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthou, S.; Kendon, E.J.; Chan, S.C.; Ban, N.; Leutwyler, D.; Schär, C.; Fosser, G. Pan-European climate at convection-permitting scale: a model intercomparison study. Climate Dynamics 2020, 55, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Driving Model (GCM) | RCM | Ensemble | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHEC-EC-Earth | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r1i1p1 | 1950-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| ICHEC-EC-Earth | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r3i1p1 | 1950-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| ICHEC-EC-Earth | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r12i1p1 | 1950-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| MPI-M-MPI-ESM-LR | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r1i1p1 | 1949-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| MPI-M-MPI-ESM-LR | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r2i1p1 | 1949-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| MPI-M-MPI-ESM-LR | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r3i1p1 | 1949-2005 | 2006-2100 |

| CNRM-CERFACES-CNRM-CM5 | COSMO-crCLIM-v1-1 | r1i1p1 | 1951-2005 | 2006-2100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).