1. Introduction

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a disease that occurs in Temporomandibular joint (TMJ), surrounding structures and masticatory muscles. Although the prevalence of TMD varies from study to study, it shows a U-shaped pattern with increasing age. Among them, TMJ osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease that occurs in the TMJ and is common even at a young age. The TMJ is an important growth point for facial profile formation, and growth is completed at the age of 16 for females and 18 for males on average [

1]. Therefore, severe OA in juvenile patients changes the normal growth pattern and, when occurring unilaterally, results in facial asymmetry. Bilateral occurrence can cause facial deformities such as posterior rotation and mandibular retraction. In addition, limitation of physical function such as mastication and conversation makes daily functions difficult [

1,

2]. Therefore, early diagnosis is important, but in the early stages, clinical symptoms such as pain and crepitation often do not coincide with the state of arthritis, so it is often missed [

3]. Therefore, the condition is accidentally discovered after visiting a hospital for orthodontic treatment because of severe facial asymmetry, or for an openbite or other dental treatment such as tooth extraction and restorative treatment. However, early arthritis may not be detected on conventional images, such as panoramic images, even after visiting a hospital; therefore, it may be missed unless conebeam CT (CBCT) is performed.

In this study, juvenile idiopathic osteoarthritis (JOA) encompassed all OA in juvenile patients. In general, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) can be distinguished from idiopathic condylar resorption (ICR) as it lacks joint inflammation and synovitis. However, it is difficult to clinically differentiate between JIA and ICR that involves the TMJ with minimal pain, lack of swelling, and low-sensitivity MRI. Both conditions s how high overlap in radiological and clinical manifestations and are used inter-changeably in studies [

4,

5,

6]. Some argue that the diagnostic difference between ICR and JIA is due to difference in the timing of diagnosis rather than the difference in disease itself [

7]. Although many studies have been conducted, overall understanding of the JOA is still limited. In addition, previous studies on condylar volume have mainly been con-ducted in Caucasians, and studies in Asians are lacking [

8,

9]. And most studies have focused on the condyle, and there are few studies on articular eminence. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to compare the volume and length of the normal condyle, unilateral and bilateral JOA, and the articular eminence.

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective case-control study, eminence, condylar volume, and length were analyzed by comparing patients affected by unilateral and bilateral JOA and comparing them with healthy controls. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents depending on their age at the initial visit. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Dental Hospital (IRB No. PNUDH-2021-022). This study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for Human Studies.

2.1. Study participants and design

All subjects were recruited from among those who visited the Department of Oral Medicine at the Pusan National University Dental Hospital between January 2017 and December 2020. Patients who met the criteria for OA diagnosis according to The Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) were included. 11, 12) As a control group, CBCT was performed for tooth extraction or orthodontic evaluation at the first visit. Patients who had no erosion, sclerosis, subcortical cysts, or flattening in both the TMJ and eminence on CBCT, no previous orthodontic treatment, and no previous cranio-facial trauma were included. Patients with no congenital craniofacial deformities, condylar fractures, or TMJ tumors were also included. A total of 116 participants, including 16 control participants, were divided into four groups. (1) Control group (n = 16); (2) affected condyle of unilateral JOA (Aff-Uni) (n = 36); (3) unaffected condyle of JOA (NonAff-Uni) (n = 36); (4) Bilateral JOA (Bilateral) (n=28). Only the right side of the subject was investigated for all joints.

2.2. Image Acquisition and 3D reconstruction

CBCT images were obtained from all patients using Pax-Zenith 3D (Vatech, Hwaseong, South Korea). The CBCT data were reformatted using 3-dimensional (3-D) imaging soft-ware (Ondemand 3-D; Cybermed Co., Seoul, Korea) set to the following parameters: field of view, 20 × 20 cm; tube voltage:110 kVp; tube current:4.0 mA; and scan time,24 s. All interpretations were performed under the same graphical conditions. All condyles and articular eminences were visualized in the recommended bone density range (range of grayscale from −1350 to 1650), as previously described and then graphically isolated prior to the 3D and volumetric measurements. The adaptive threshold was determined to be 500 Hounsfield units [

9].

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Condylar

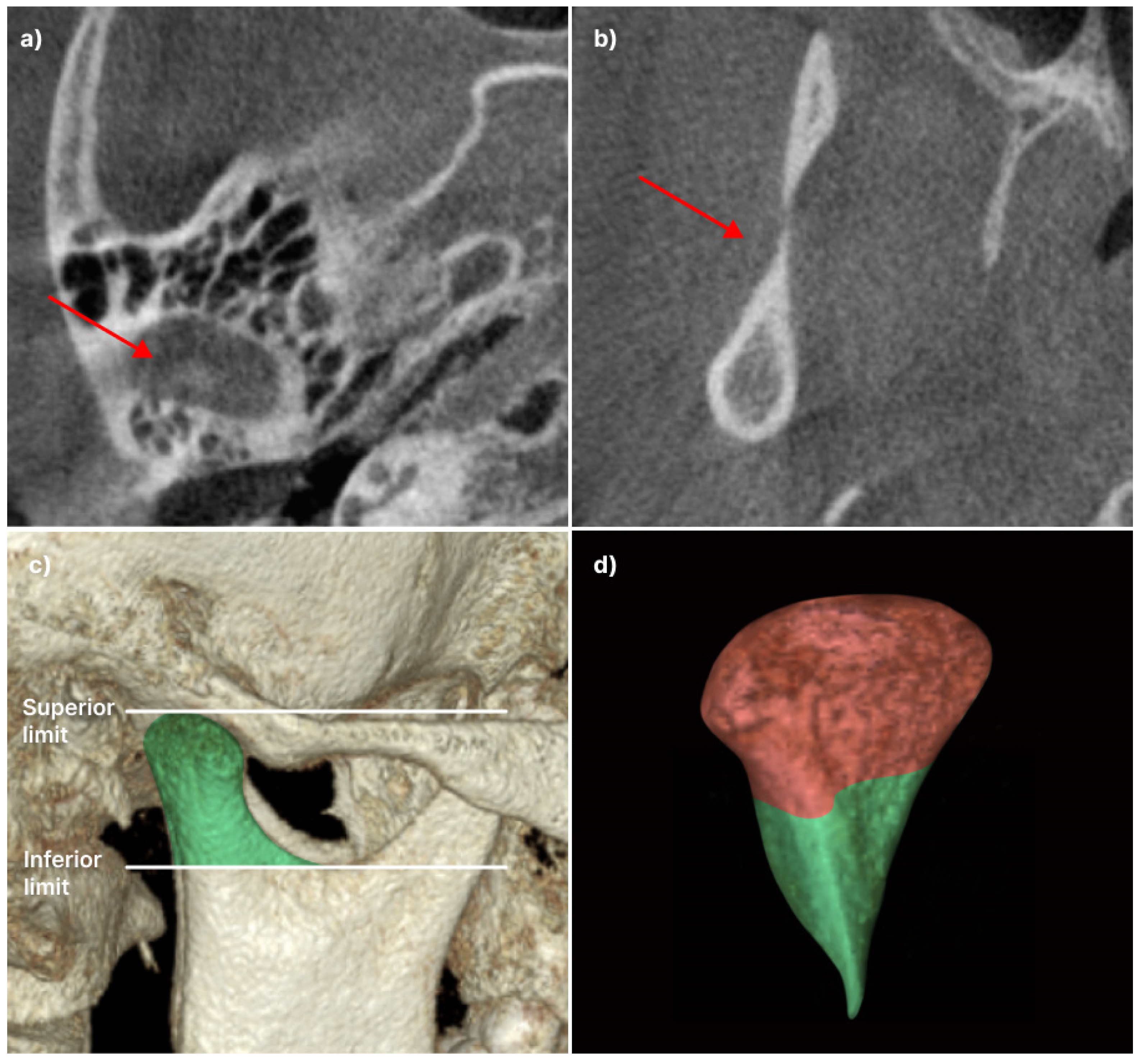

The method for measuring condylar volume referred to previous studies [

8,

12]. Segmentation and condylar lateral limit identified were completed in the axial view. The upper limit of the condyle was considered when the first radiopacity was observed in the upper articular region. The lower limit of the condyle was selected when the first sigmoid notch disappeared. For detailed condylar volume measurement, the head and neck of the condyle were separated at the boundary where the contour of the condyle changes from “ellipsoidal” to “circular” (

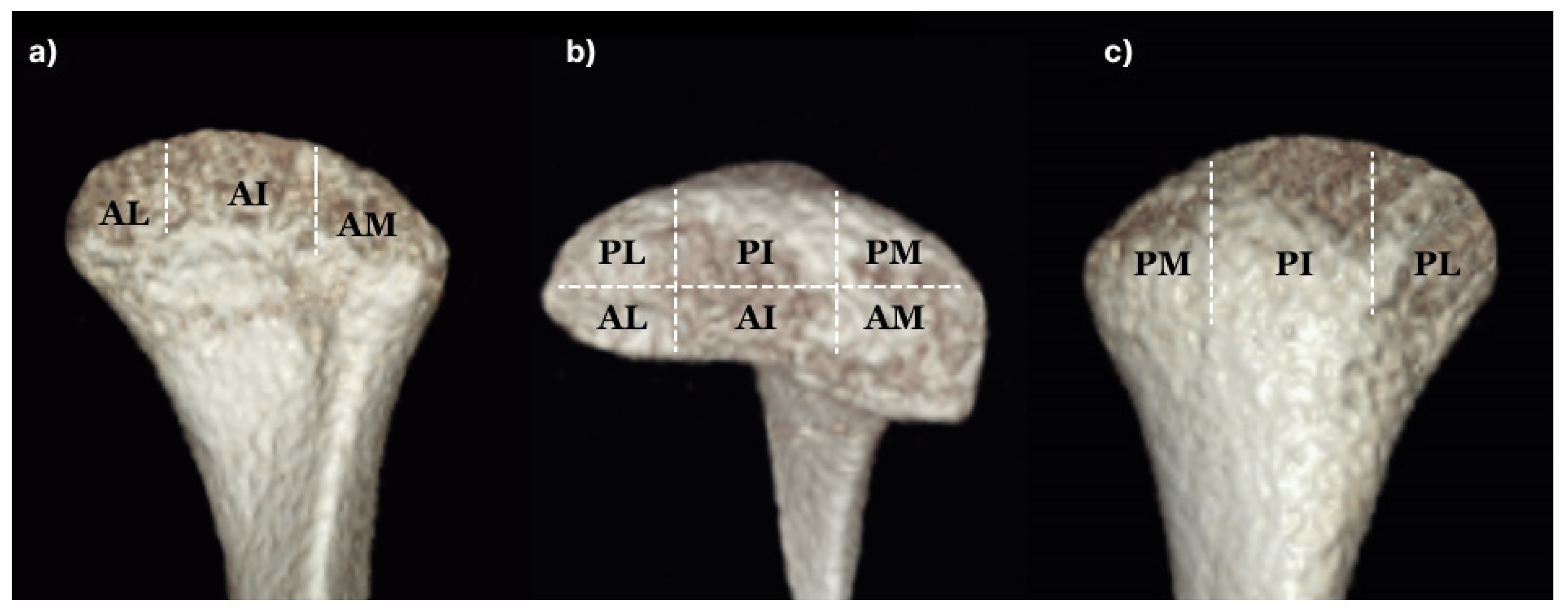

Figure 1). Subsequently, the plane passing through the medial and lateral poles was divided into anterior and posterior planes. Each isometrically partitioned into lateral, intermediate, and medial segments, thereby delineating the anterolateral (AL), anterior-intermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), and posteromedial (PM) sections in the head of the condyle. (

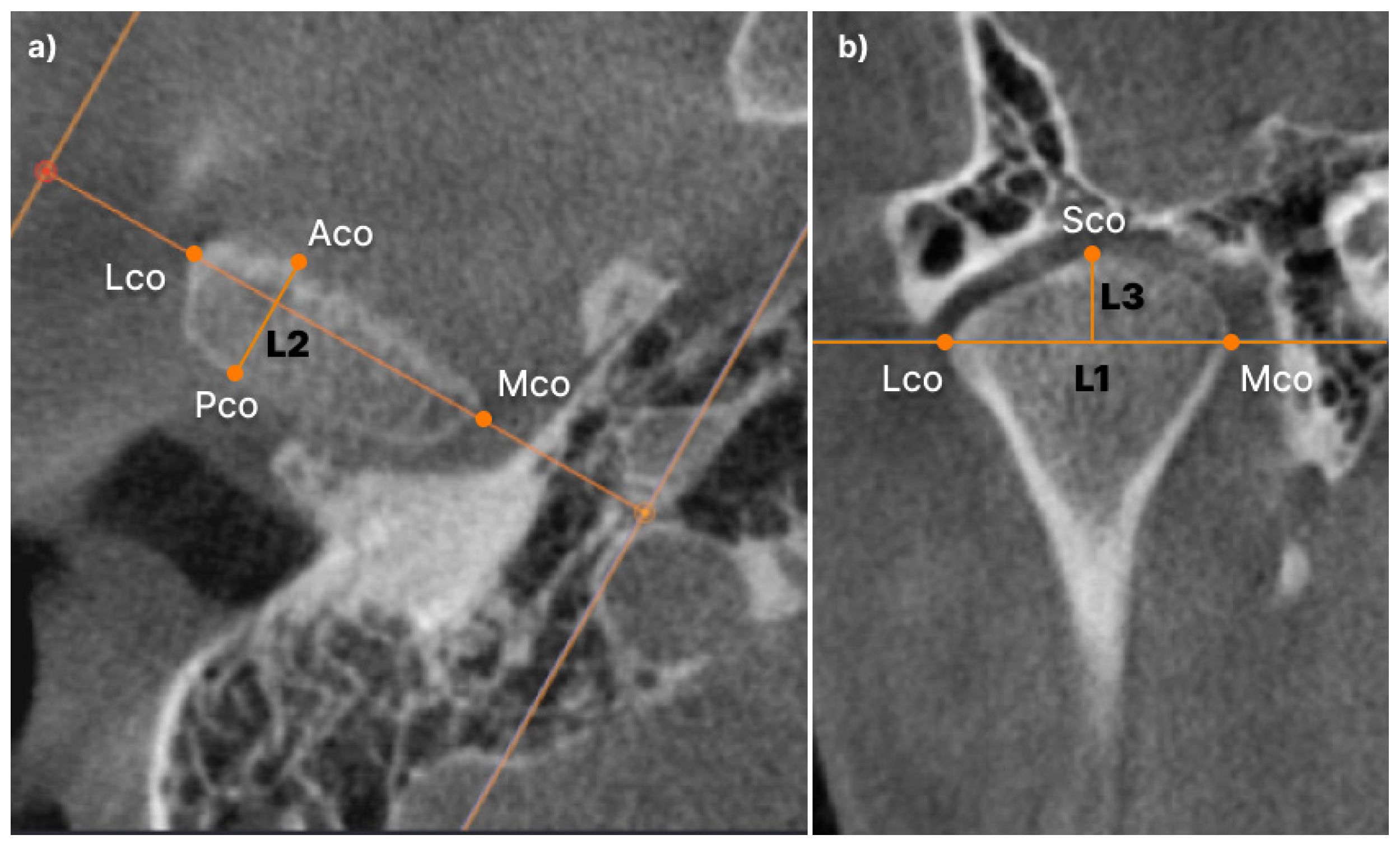

Figure 2). Linear condyle measurements were performed using coronal and axial views of the CBCT images. The most anterior extent of the mandibular condyle was defined as ACo, the most posterior extent of the mandibular condyle as PCo, the most lateral extent of the mandibular condyle as LCo, the most medial extent of the mandibular condyle as Mco, and the most superior aspect of the mandibular condyle as SCo. L1 (LCo-MCo): condylar width measured in the coronal view. Linear distance between the lateral and medial L2 (ACo-PCo): Condylar length measured on the axial view. Linear distance between the anterior and posterior L3 (SCo-L1 perpendicular): Condylar height measured in the coronal view. Linear distance of the perpendicular line traced from SCo to L1 (

Figure 3) [

13].

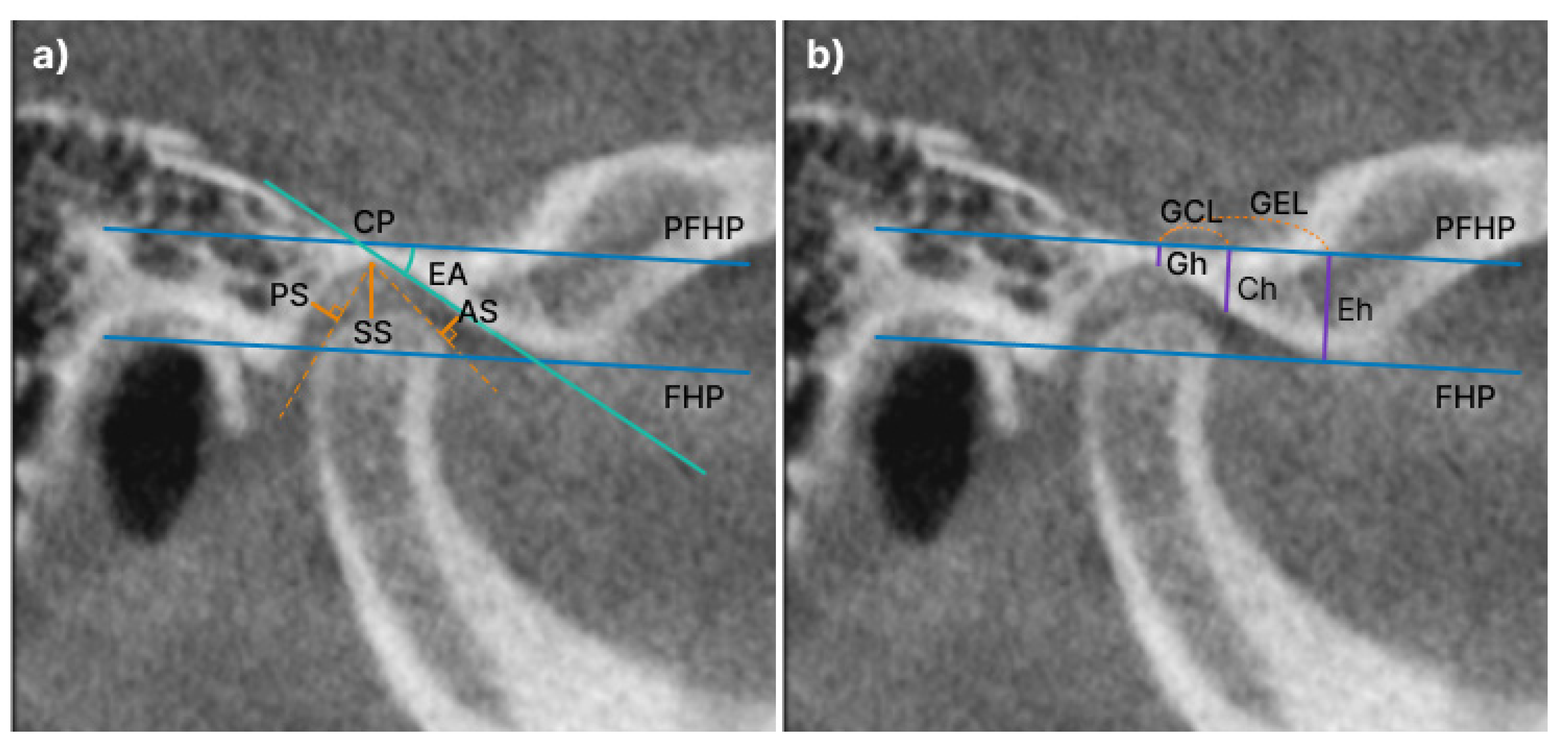

2.3.2. Anteroposterior condylar position in glenoid fossa

To confirm the positional relationship between the condylar positions in the glenoid fossa, the anterior, posterior, and superior spaces (AS, PS, and SS, respectively) were measured from the most prominent anterior, posterior, and superior points of the condyle to the glenoid fossa. This plane (parallel to the FH plane) was used as the reference. The lines tangential to the most prominent anterior and posterior aspects of the condyle were drawn from the superior aspect of the glenoid fossa on the reference plane (

Figure 4-a) [

14].

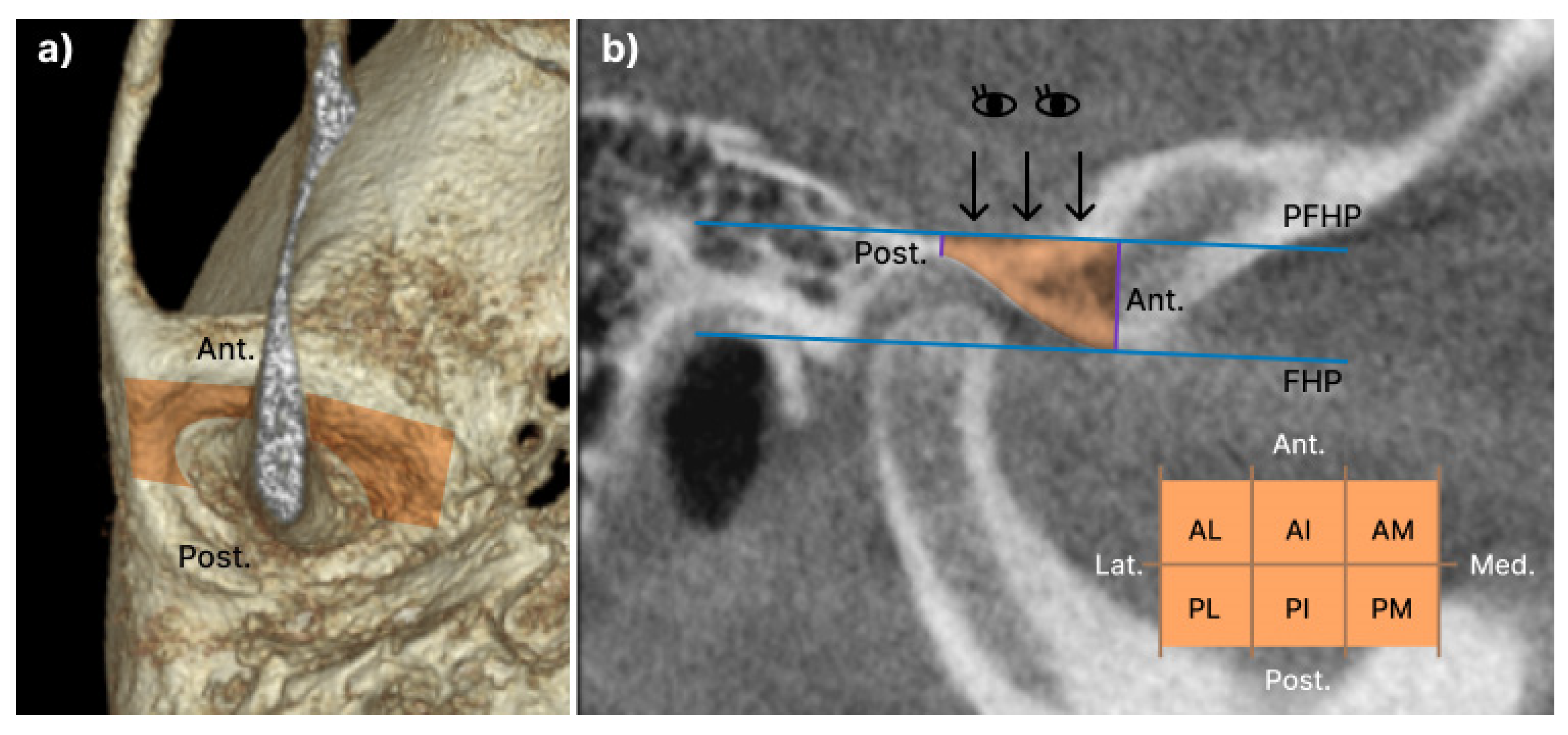

2.3.3. Articular eminence

The articular eminence volume was set as the anterior and posterior limits of the plane containing the line drawn vertically from the highest point of the glenoid fossa on the Frankfort horizontal plane, and the parallel plane containing the line drawn from the lowest point of the articular eminence on the FH plane. The lateral boundary was defined as the sagittal plane perpendicular to the FH plane passing through the outermost point of the temporal bone, whereas the medial boundary was defined as the sagittal plane perpendicular to the FH plane passing through the innermost point, where the lower boundary intersects the temporal bone. The two lines of the anterior and posterior borders, and the lateral and medial borders formed a rectangle perpendicular to them (

Figure 5) [

15,

16]. For detailed volume measurement of the articular eminence, the center points of each of the lateral and medial planes were connected, and the plane perpendicular to the FH plane was divided into anterior and posterior planes. Additionally, perpendicular to the plane dividing the anterior and posterior, it was divided equally into anterolateral (AL), anterior-intermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), and posteromedial (PM). The eminence was divided into six equal parts (

Figure 5).

2.3.4. Linear measurement of the articular eminence

Gh was defined as the length of a line perpendicular to the uppermost point of the glenoid fossa in the FHP, and Eh was defined as a line constructed parallel to the FHP, tangent to the apex of the articular eminence, with a line perpendicular to the depth of the mandibular fossa. The CP represents the inflection point of the slope of the articular eminence. Ch is defined as the length of the line perpendicular to CP in the PFHP. The GEL was defined as the distance between the PFHP and Gh points and the PFHP and Eh points, and the GCL was defined as the distance between the FHP and Gh points and the FHP and CP points (

Figure 4-b). The EA (angle) is the angle at which the tangent of the distal slope passing through the CP and FHP meets; that is, the articular inclination. (

Figure 4-a)

CBCT scans were performed by the same surgeon. Condyle and articular eminence length and volume measurements were performed by two people and were measured again 2 weeks after the initial measurement to measure the error between the intraobserver and interobserver methods.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. 3. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess whether the data were normally distributed. The chi-square test was used to analyze the sex distribution. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and bonferroni post-hoc were used to identify differences in the clinical characteristics of age, NRS, MCO, overjet, and overbite. In addition, ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to evaluate differences in volume, length, and position between the control, unilateral JOA, and bilateral JOA groups. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for comparison between groups were calculated to compare intra-and interoperator variability.

3. Results

Among all patients with JOA (n=100), there were 76 females and 24 males: approximately three times as many females. The NRS was 3.51±2.28 on average for all JOAs, which was smaller than the control group at 4.41±2.34, but there was no statistical difference. In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in clinical manifestations such as sex, NRS, age, MCO, overjet, and overbite among the four groups (

Table 1).

3.1. Comparison of condylar volume and length

Table 2 compares condylar volume and length between the control, aff-uni, non-aff-uni, and bilateral groups. Total condyle volume showed a statistically significant difference between the four groups, and the post hoc test showed that it was larger in the control than the bilateral group. The condylar head total volume (CHTV), after re-moving the neck from the condylar total volume (CTV), was greater in the control and NonAff-uni groups than in bilateral controls. In the detailed volume measurement, a difference in volume between the groups was observed in the ants. and post., mid, and ant. med. groups. Condylar lengths were different in L1, L2, and L3. In L1, there was a statistical difference between the bilateral and control groups, and in L2, the control group was longer than the aff-uni, non-aff-uni, and bilateral groups. At L3, the control, Aff-Uni, and Non-Aff-Uni groups showed bilateral differences (

Table 2).

3.2. Anteroposterior condylar position in glenoid fossa

There was no significant difference between the four groups in the condylar position within the glenoid fossa, but the AS was narrower in the NonAff-Uni group than in the control group (

Table 3).

3.3. Comparison of eminence volume and length in Control and JIA with unilateral and bilateral eminence

Table 4 compares eminence volume and length between the four groups. There was a statistically significant difference in ETV between the four groups, and the control was greater than the Aff-Uni. Comparing the size of the detailed volume, the size of the PL and PM were larger than that of the Aff-Uni and NonAff-Uni in the control group. The average eminence slope was 48.72±11.53, with no statistical difference between the 4 groups. The lengths of Gh, Ch, Eh, GCL, and GEL were not statistically different among the four groups.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have mainly examined condylar total volume; few studies have divided and confirmed articular eminence and condylar volumes, as in this study [

9,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The TMJ articular surface with fibrocartilage has remarkable adaptive capacity. However, functional demands that exceed the adaptive capacity cause a maladaptive response and OA. The etiology of TMJ-OA is complex, multifactorial, and still unknown; previous studies have shown that excessive mechanical load on normal articular cartilage, or normal mechanical load on damaged articular cartilage, generally lead to OA starting from the disruption of cartilage matrix homeostasis [

21]. Whenever functions such as opening and mastication are performed, the condyle and articular eminence receive mutual pressure and rub against each other. The degree or aspect of destruction shows individual differences. Growing condyles show a different adaptability to overload than that observed in the adult TMJ, and inhibit growth itself. Excessive pressure during growth can slow endochondral growth velocity, pre-venting cortical lining formation. This affects immature subarticular and secondary cartilages, which alters growth direction in patients with JOA [

17,

21]. As a result, in this study, all lengths of L1 (lateral and medical), L2 (anterior and posterior), and L3 (condylar height) were small, and total condylar volume was small (

Table 1).

Interestingly, in this study, there was a clear difference between the control and bilateral JOA in condylar volume. The difference was more visible is the most convex part, which is the middle of the ant., post, and ant sections. In the articular eminence, a difference in size was shown in the posterolateral and medial parts of the control, Aff-Uni JOA, and NonAff-Uni JOA groups. In studies comparing the morphological changes of condylar OA in adults, the superior surface showed the greatest difference when compared to healthy controls, as in this study [

22,

23].

The lateral surface of condyles usually demonstrates resorption in TMJOA patients, with resultant flattening on the lateroposterior condylar [

24,

25]. From the viewpoint of homeostasis and adaptability, in patients with bilateral JOA, the condyle was relatively more destroyed along the main movement path of the joint amid mutual friction between the condyle and the articular eminence. In cases of Aff-Uni JOA and NonAff-Uni JOA, the lateral and medial part of posterior articular eminence was con-firmed to be more destroyed. This is likely the result of a muscle imbalance causing unilateral JOA; as a result. the direction of pressure applied to the joint is concentrated on both the lateral and medial sides rather than the middle [

26,

27]. Even in the positional relationship of the condyles within the glenoid fossa, this difference in unilateral JOA caused a midline shift to the affected side, resulting in a small AS in the NonAff-Uni group (

Table 3).

A problem in treating patients with JOA is the mismatch between clinical symptoms and the severity of bone destruction. Therefore, many adolescent patients do not realize the seriousness of their condition, do not modify their behavior, forget to take their medicine, and do not wear the device. Therefore, the seriousness must be emphasized every time they are followed up. In that case, it is thought that the cooperation of treatment can be increased by emphasizing the reduction of bone volume, which can occur when JOA is neglected.

Although this study provided information on the condylar and eminence volumes and lengths of unilateral and bilateral JOA in Asian patients, it has several limitations. First, cross-sectional conditions were compared, and bone changes in patients with JOA were not measured longitudinally within the same patient. In addition, in the same unilateral JOA patient, within the same patient who can be affected by each other, there is a case in which the sample size per group is reduced by dividing the group differently by unifying all measured joints to the right side without measuring the affected and non-affected sides. In the same patient with unilateral JOA, the sample size per group decreased be-cause the groups were divided differently by unifying all the measured joints to the right side without measuring the affected and non-affected sides within the same patient that could be affected by each other.

5. Conclusions

In this retrospective case-control study, there was a clear difference in condyle volume between the control and bilateral JOA groups, and this occurred frequently in the mid and medial parts of the condyle. Regarding overall condylar length, the length between the lat. and med. (L1) was clearly observed between the control and bilateral, and the lengths of the ant. and post (L2) sections were smaller than those in the control, unilaterally affected, unilaterally affected, and bilateral groups. L3 in the bilateral group was significantly lower than that in the other groups. In terms of total eminence volume, Aff-Uni patients had statistically smaller volumes than controls in a different aspect from the condyle. When the volumes were divided in detail and compared, a difference in volume was found in the PL and PM groups vs the control group. In the detailed eminence volume comparison, the same results were observed, not only on the affected side, but also on the unaffected side. There were no statistically significant differences between the control and eminence volumes. Unlike previous studies that have focused on the volume of the condyle in JOA patients, this study also compared the difference in volume of eminence. The results of this study showed that the unilateral and bilateral JOA appeared differently. In future studies, the articular eminence and condyle both should be studied, and unilateral and bilateral JOA should be studied separately.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-M.JU. and S.-M.O.; methodology, H.-M.JU.; software, H.-W.K.; validation, H.-W.K., and S.-Y.C.; formal analysis, H.-M.JU.; investigation, H.-M.JEON ; resources, Y.-W.A; data curation, S.-H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-M.JU.; writing—review and editing, S.-M.O.; visualization, H.-W.K.; supervision, S.-M.O.; project administration, S.-M.O.; funding acquisition, H.-M.JU. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI23C0162).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Dental Hospital (IRB No. PNUDH-2021-022). This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki for human studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all patients or their parents, depending on their age, at the initial visit.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported.

References

- Genden, E.M.; Buchbinder, D.; Chaplin, J.M.; Lueg, E.; Funk, G.F.; Urken, M.L. Reconstruction of the pediatric maxilla and mandible. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2000, 126, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard, A.-F.; Kaban, L.B.; Peacock, Z.S. Acquired abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics 2018, 30, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.K.; Küseler, A.; Gelineck, J.; Herlin, T. A prospective study of magnetic resonance and radiographic imaging in relation to symptoms and clinical findings of the temporomandibular joint in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology 2008, 35, 1668–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowicz, S.; Kim, S.; Prahalad, S.; Chouinard, A.; Kaban, L. Juvenile arthritis: current concepts in terminology, etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2016, 45, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A. Idiopathic condylar resorption: the current understanding in diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of the Indian Prosthodontic Society 2017, 17, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimanovic, D.; Pedersen, T.K.; Matzen, L.H.; Stoustrup, P. Comparing clinical and radiological manifestations of adolescent idiopathic condylar resorption and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the temporomandibular joint. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2021, 79, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, T.K.; Stoustrup, P. How to diagnose idiopathic condylar resorptions in the absence of consensus-based criteria? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2021, 79, 1810–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecco, S.; Saccucci, M.; Nucera, R.; Polimeni, A.; Pagnoni, M.; Cordasco, G.; Festa, F.; Iannetti, G. Condylar volume and surface in Caucasian young adult subjects. BMC medical imaging 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccucci, M.; Polimeni, A.; Festa, F.; Tecco, S. Do skeletal cephalometric characteristics correlate with condylar volume, surface and shape? A 3D analysis. Head & face medicine 2012, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Southwood, T.R.; Manners, P.; Baum, J.; Glass, D.N.; Goldenberg, J.; He, X.; Maldonado-Cocco, J.; Orozco-Alcala, J.; Prieur, A.-M. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. The Journal of rheumatology 2004, 31, 390–392. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache 2014, 28, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ok, S.-M.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-I.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, K.B.; Jeong, S.-H. Anterior condylar remodeling observed in stabilization splint therapy for temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology 2014, 118, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sanz, V.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Hernández, V.; Serrano-Sánchez, P.; Guarinos, J.; Paredes-Gallardo, V. Accuracy and reliability of cone-beam computed tomography for linear and volumetric mandibular condyle measurements. A human cadaver study. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- KIM, Y.I.; JUNG, Y.H.; CHO, B.H.; KIM, J.R.; KIM, S.S.; SON, W.S.; PARK, S.B. The assessment of the short-and long-term changes in the condylar position following sagittal split ramus osteotomy (SSRO) with rigid fixation. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2010, 37, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Ohe, J.-Y.; Choi, B.-J. Three-dimensional volumetric analysis of condylar head and glenoid cavity after mandibular advancement. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2018, 46, 1470–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, S.-M.; Jeong, S.-H.; Ahn, Y.-W.; Kim, Y.-I. Effect of stabilization splint therapy on glenoid fossa remodeling in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Journal of Prosthodontic Research 2016, 60, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.F.O.; Pedersen, T.K.; Dalstra, M.; Herlin, T.; Verna, C. 3D evaluation of mandibular skeletal changes in juvenile arthritis patients treated with a distraction splint: A retrospective follow-up. The Angle Orthodontist 2016, 86, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnetto, D.; Abate, A.; Caprioglio, A.; Cressoni, P.; Maspero, C. Three-dimensional volumetric evaluation of the different mandibular segments using CBCT in patients affected by juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Progress in Orthodontics 2021, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Lagravere, M.O.; Kaipatur, N.R.; Major, P.W.; Romanyk, D.L. Reliability and accuracy of a method for measuring temporomandibular joint condylar volume. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology 2021, 131, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, A.; Caruso, S.; Ehsani, S.; Baldini, A.; Tecco, S. Three-dimensional volumetric analysis of mandibular condyle changes in growing subjects: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Cranio® 2020, 38, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibbets, J.M.; Carlson, D.S. Implications of temporomandibulardisorders for facial growth and orthodontic treatment. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Orthodontics; 1995; pp. 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, L.R.; Gomes, M.; Jung, B.; Paniagua, B.; Ruellas, A.C.; Gonçalves, J.R.; Styner, M.A.; Wolford, L.; Cevidanes, L. Diagnostic index of 3D osteoarthritic changes in TMJ condylar morphology. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2015: Computer-Aided Diagnosis; 2015; pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cevidanes, L.H.; Walker, D.; Schilling, J.; Sugai, J.; Giannobile, W.; Paniagua, B.; Benavides, E.; Zhu, H.; Marron, J.S.; Jung, B.T. 3D osteoarthritic changes in TMJ condylar morphology correlates with specific systemic and local biomarkers of disease. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2014, 22, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoukri, B.; Prieto, J.; Ruellas, A.; Yatabe, M.; Sugai, J.; Styner, M.; Zhu, H.; Huang, C.; Paniagua, B.; Aronovich, S. Minimally invasive approach for diagnosing TMJ osteoarthritis. Journal of Dental Research 2019, 98, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nah, K.-S. Condylar bony changes in patients with temporomandibular disorders: a CBCT study. Imaging science in dentistry 2012, 42, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, R.; Ioi, H.; Goto, T.; Hara, A.; Nakata, S.; Nakasima, A.; Counts, A. Relationship between the unilateral TMJ osteoarthritis/osteoarthrosis, mandibular asymmetry and the EMG activity of the masticatory muscles: a retrospective study. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2010, 37, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, Y.; Nakata, S.; Watanabe, M.; Komiya, C. Functional analysis of the masticatory muscle in a patient with progressing facial asymmetry. Orthod Waves Jpn Ed 1994, 53, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Defining boundaries for condyle volume measurement: (a) The superior limit of the condyle is identified when the first radiopaque point is observed in the upper articular region; (b) The inferior limit of the condyle is selected when the first sigmoid notch disappeared; (c) On sagittal view, superior and inferior limit; (d) The head and neck of the condyle are separated at the boundary where the contour of the condyle changes from “ellipsoidal” to “circular”.

Figure 1.

Defining boundaries for condyle volume measurement: (a) The superior limit of the condyle is identified when the first radiopaque point is observed in the upper articular region; (b) The inferior limit of the condyle is selected when the first sigmoid notch disappeared; (c) On sagittal view, superior and inferior limit; (d) The head and neck of the condyle are separated at the boundary where the contour of the condyle changes from “ellipsoidal” to “circular”.

Figure 2.

Detail volume of a condyle. Each is isometrically partitioned into lateral, intermediate, and medial segments, thereby delineating the anterolateral (AL), anterior-intermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), and posteromedial (PM) sections in the head of the condyle: (a) Anterior view; (b) superior view; (c) posterior view.

Figure 2.

Detail volume of a condyle. Each is isometrically partitioned into lateral, intermediate, and medial segments, thereby delineating the anterolateral (AL), anterior-intermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), and posteromedial (PM) sections in the head of the condyle: (a) Anterior view; (b) superior view; (c) posterior view.

Figure 3.

Linear measurement of condyle. Aco: most anterior extent of the mandibular condyle was defined; Pco: most posterior extent of the mandibular condyle; Lco: most lateral extent of the mandibular condyle; Mco: most medial extent of the mandibular condyle; Sco: most superior aspect of the mandibular condyle: (a) L2 (Aco-Pco): condylar length measured in the axial view. Linear distance between anterior and posterior; (b) L1 (Lco-Mco): condylar width measured in the coronal view. Linear distance between the lateral and medial L3 (SCo-L1 perpendicular): Condylar height measured in the coronal view. Linear distance of the perpendicular line traced from Sco to L1.

Figure 3.

Linear measurement of condyle. Aco: most anterior extent of the mandibular condyle was defined; Pco: most posterior extent of the mandibular condyle; Lco: most lateral extent of the mandibular condyle; Mco: most medial extent of the mandibular condyle; Sco: most superior aspect of the mandibular condyle: (a) L2 (Aco-Pco): condylar length measured in the axial view. Linear distance between anterior and posterior; (b) L1 (Lco-Mco): condylar width measured in the coronal view. Linear distance between the lateral and medial L3 (SCo-L1 perpendicular): Condylar height measured in the coronal view. Linear distance of the perpendicular line traced from Sco to L1.

Figure 4.

Anteroposterior condylar position in the glenoid fossa and linear measurement of the articular eminence: a) The anterior, posterior, and superior spaces (AS, PS, and SS, respectively) are measured from the most prominent points on the condyle to the glenoid fossa. FHP: Frank-horizontal (FH) plane; PFHP: parallel to the FHP; EA (angle): the angle at which the tangent of the distal slope passing the CP and FHP meets, that is, the articular inclination; b) Gh, the length of a line perpendicular to the uppermost point of the glenoid fossa in the FHP; Eh, a line constructed parallel to the FHP tangent to the apex of the articular eminence with a line perpendicular to the depth of the mandibular fossa; CP, the inflection point of the slope of the articular eminence; Ch, the length of a line perpendicular to the CP in the PFHP; GEL, the distance between the PFHP and Gh points and the PFHP and Eh points; GCL, the distance between the FHP and Gh points and the FHP and CP points.

Figure 4.

Anteroposterior condylar position in the glenoid fossa and linear measurement of the articular eminence: a) The anterior, posterior, and superior spaces (AS, PS, and SS, respectively) are measured from the most prominent points on the condyle to the glenoid fossa. FHP: Frank-horizontal (FH) plane; PFHP: parallel to the FHP; EA (angle): the angle at which the tangent of the distal slope passing the CP and FHP meets, that is, the articular inclination; b) Gh, the length of a line perpendicular to the uppermost point of the glenoid fossa in the FHP; Eh, a line constructed parallel to the FHP tangent to the apex of the articular eminence with a line perpendicular to the depth of the mandibular fossa; CP, the inflection point of the slope of the articular eminence; Ch, the length of a line perpendicular to the CP in the PFHP; GEL, the distance between the PFHP and Gh points and the PFHP and Eh points; GCL, the distance between the FHP and Gh points and the FHP and CP points.

Figure 5.

The volume of Articular eminence: a) The boundaries of the articular eminence are outlined in orange and are shown in the coronal view; b) Detailed volume measurement of the articular eminence. anterolateral (AL), anterointermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), posteromedial (PM). The eminence is divided into six equal parts.

Figure 5.

The volume of Articular eminence: a) The boundaries of the articular eminence are outlined in orange and are shown in the coronal view; b) Detailed volume measurement of the articular eminence. anterolateral (AL), anterointermediate (AI), anteromedial (AM), posterolateral (PL), posterior-intermediate (PI), posteromedial (PM). The eminence is divided into six equal parts.

Table 1.

Clinical manifestation.

Table 1.

Clinical manifestation.

| |

Controls

(n=16) |

Aff-Uni

(n=36) |

NonAff-Uni

(n=36) |

Bileteral

(n=28) |

P-value |

| Sex |

F |

8(50.0) |

28(77.8) |

24(66.7) |

24(85.7) |

0.055 |

| |

M |

8(50.0) |

8(22.2) |

12(33.3) |

4(14.3) |

| Age |

15.44±1.75 |

14.06±2.60 |

14.36±2.11 |

14.29±2.32 |

0.246 |

| NRS |

4.41±2.34 |

3.44±2.44 |

3.75±2.14 |

3.27±2.28 |

0.413 |

| MCO |

33.38±11.41 |

36.97±11.75 |

35.31±7.63 |

33.96±7.80 |

0.526 |

| overjet |

4.99±1.59 |

4.92±2.27 |

4.41±2.67 |

5.46±2.06 |

0.351 |

| overbite |

0.38±3.56 |

1.39±2.44 |

2.14±2.09 |

1.14±2.79 |

0.153 |

Table 2.

Comparison of condylar length and volume in Control and JOA with unilateral and bilateral.

Table 2.

Comparison of condylar length and volume in Control and JOA with unilateral and bilateral.

| |

Controls

(n=16) |

Aff-Uni

(n=36) |

NonAff-Uni

(n=36) |

Bileteral

(n=28) |

P-value |

Post-Hoc

(bonferroni) |

| CTV |

1772.51±631.34 |

1511.20±608.02 |

1645.34±521.54 |

1290.00±552.59 |

0.030* |

Controls> Bilateral |

| CHTV(mm3) |

1245.23±408.75 |

1003.70±370.08 |

1120.17±374.95 |

843.57±326.02 |

0.003** |

Controls, NonAff-Uni>Bilateral |

| CAntLatV |

276.28±139.81 |

262.43±137.75 |

264.49±121.81 |

230.25±131.03 |

0.643 |

|

| CPostLatV |

87.99±54.69 |

64.45±31.25 |

80.24±39.84 |

56.53±41.39 |

0.029 |

|

| CAntMidV |

521.83±184.08 |

397.58±201.12 |

436.29±199.03 |

320.29±150.67 |

0.006** |

Controls> Bilateral |

| CPostMidV |

166.80±98.98 |

137.24±70.93 |

172.96±69.73 |

115.94±55.48 |

0.010** |

NonAff-Uni>Bilateral |

| CAntMedV |

139.23±80.55 |

91.17±46.59 |

105.87±74.83 |

76.91±45.56 |

0.012* |

Controls> Bilateral |

| CPostMed |

53.11±21.94 |

50.83±29.05 |

60.32±37.40 |

43.66±25.16 |

0.186 |

|

| L1(mm) |

19.35±2.49 |

17.49±2.69 |

17.38±2.80 |

16.20±2.86 |

0.005** |

Controls> Bilateral |

| L2(mm) |

19.16±2.46 |

17.08±2.68 |

16.80±2.44 |

15.74±2.08 |

0.000*** |

Controls>Aff-Uni, NonAff-Uni, Bilateral |

| L3(mm) |

5.75±1.51 |

5.28±1.39 |

5.96±1.29 |

4.35±1.05 |

0.000*** |

Controls, Aff-Uni, NonAff-Uni>Bilateral |

Table 3.

Anteroposterior condylar position in glenoid fossa.

Table 3.

Anteroposterior condylar position in glenoid fossa.

| |

Controls

(n=16) |

Aff-Uni

(n=36) |

NonAff-Uni

(n=36) |

Bileteral

(n=28) |

P-value |

Post-Hoc

(bonferroni) |

| PS |

1.97±0.68 |

2.04±1.34 |

2.06±1.15 |

2.19±1.24 |

0.943 |

|

| SS |

3.38±1.12 |

2.79±1.22 |

2.58±0.80 |

2.98±1.53 |

0.146 |

|

| AS |

3.94±1.80 |

3.29±1.81 |

2.63±1.08 |

3.21±1.46 |

0.036* |

Controls>NonAff-Uni |

Table 4.

Comparison of eminence length and volume in Control and JOA with unilateral and bilateral.

Table 4.

Comparison of eminence length and volume in Control and JOA with unilateral and bilateral.

| |

Controls

(n=16) |

Aff-Uni

(n=36) |

NonAff-Uni

(n=36) |

Bileteral

(n=28) |

P-value |

Post-Hoc

(Bonferroni) |

| EA(angle) |

54.36±10.35 |

49.49±11.89 |

46.86±11.60 |

46.84±11.02 |

0.130 |

|

| Gh(mm) |

2.16±1.47 |

1.60±1.11 |

1.96±1.91 |

2.01±1.22 |

0.558 |

|

| Ch |

6.39±1.68 |

6.00±1.44 |

6.16±2.12 |

6.50±1.45 |

0.684 |

|

| Eh |

10.33±1.95 |

9.32±1.82 |

9.80±2.39 |

9.58±1.57 |

0.376 |

|

| GCL |

5.11±1.61 |

5.39±1.23 |

5.44±1.34 |

6.18±1.91 |

0.084 |

|

| GEL |

11.14±3.25 |

11.38±1.73 |

12.29±2.06 |

12.57±2.38 |

0.072 |

|

| ETV |

254.97±174.42 |

150.89±76.30 |

168.70±120.55 |

202.24±119.33 |

0.023* |

Controls>Aff-Uni |

| EAntLatV |

28.90±23.34 |

14.28±12.14 |

22.08±28.77 |

22.19±27.88 |

0.197 |

|

| EAntMidV |

43.64±33.97 |

29.36±19.86 |

32.68±36.02 |

38.42±32.80 |

0.394 |

|

| EAntMedV |

41.72±29.80 |

24.94±17.06 |

29.21±22.55 |

31.21±25.90 |

0.118 |

|

| EPostLatV |

46.54±37.75 |

23.69±14.32 |

27.91±22.07 |

33.20±20.07 |

0.008** |

Controls>Aff-Uni, NonAff-Uni |

| EPostMidV |

49.53±36.71 |

33.16±18.86 |

31.30±19.71 |

42.68±26.11 |

0.036 |

|

| EPostMedV |

44.64±34.09 |

25.46±13.64 |

25.52±18.06 |

34.54±25.23 |

0.011* |

Controls>Aff-Uni, NonAff-Uni |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).