1. Introduction

The management of risk is frequently a matter of managing dilemmas, paradoxes, and conflicting goals. The management of these issues is seldom identified as an issue in any risk assessment, yet such conflicts have the potential to lead to poor Health and Safety outcomes, the loss of credibility, integrity and reputations, and ultimately poor decision making. The etiology of Health and Safety occurs at all levels of an organization where, there are multiple stakeholders who may have differing agendas and therefore different priorities. Within the renewable energy (offshore wind) sector the major windfarm owners, developers, and service providers, have created an industry body known as The Global Offshore Wind Health and Safety Organization shortened to the G+ who, have the stated aim “

to bring together the offshore wind industry to pursue shared goals” [

1]. G+ (2023). A number of G+ members kindly supplied a selection of their risk assessment for analysis within this research project.

While the principle focus of the research project is to analyze the risk assessment content, it is a reasonable assumption that the outcome of this research will also indicate any parallel issues that may exist within the management systems which enable the risk assessment approvals and publication process.

The traditional approach to managing the complexity of human involvement is by the application of rules to manage human inconsistency. Frerick Taylor (1856-1915) suggested that workers needed strict control and supervision so that they follow the most efficient and scientific way of undertaking their duties [

2]. The Tayloristic approaches have been adopted by others who support the compliance and supervisory based approaches by suggesting that an organizations safety policies practices and procedures are a mechanism for valuing company safety [

3], and any deviation could be described as a level of stupidity [

4]. These views are of considerable interest for research purposes as it implies that the system in which the worker operates is safe, and that the worker is therefore the hazard that needs to be managed.

Businesses function because of the systems and processes that are at the heart of their operation. Each business may likely thrive or fail depending on the quality and efficiency of its system management. An interesting definition of a system comes from Systems Science which advises:bias

“Systems do not exist in the sense of physical objects. In a certain sense, the term could be regarded as artificially made up to generate order”. [

5]

The thought of generating order from potential chaos is interesting as it reflects the complexity of managing workplace Health and Safety and reinforces the deterministic values. The deterministic approach implies that when something unexpectedly occurs the default position is that someone must have done something wrong. In early 20th century the screening of unsuitable candidates was deemed to have reduced human error from 80% to 20%. [

6]. In 1933 a UK shoe factory announced that by using appropriate testing techniques, the injury prone worker who was somehow predisposed to having accidents, could be readily identified [

7]. The idea of injury prone workers continued when it was suggested that

Accident Proneness was no longer a theory but an established fact [

8] (p.45) . More recently, however, the idea of system frailty, poor management process and poor design have become more prevalent. It is estimated that approximately 94% of business troubles emanate from common causes or faults within its systems which are a management responsibility [

9].

By examining systems management approaches in the business environment, we can see that the introduction of new technology into established systems, makes the system reverberate, and the introductions of new capabilities introduces new complexities [

10] The notion of systems and their potential frailty was not lost on ancient scholars.

The latin term Ceteris Paribus which translates as ‘all other things being equal’ which was used in the field of economics in the 16th century [

11,

12]

. In later years Ceteris Paribus became known as the substitution myth which is described as the substitution myth which states :

“a common assumption that artefacts are value neutral in the sense that their introduction into a system only has the intended and no unintended effects”. [

13]

The problems with systems of any kind are therefore well established. Although Health and Safety management systems offer the suggestion of clarity, order, and structure, ultimately, they will likely be overloaded and stretched with additions, subtractions or modifications deemed to have little or no detrimental effect. If we therefore view systems through the ‘lens’ of the research assumption that:

We can reasonably deduce that while there has been no deliberate intention to deceive, the system creators were unintentionally influenced or even oblivious to the system degradation. Which suggests that:

“The etiology of risk exists within the entropic characteristics present when static systems become dynamic” [

14].

Whilst therefore there may be an honorable belief that systems are not being stretched up to and beyond their capability, that belief mechanism is based potentially on conflicting goals, bias, and limited awareness.

The standard risk assessment now forms a fundamental part of any safety management system. Like all systems however, the environment within which they exist is constantly changing and evolving and is constantly being stretched. The system of risk assessment creation therefore is susceptible to a variety of biases, generated by the substitution myth and the application of deterministic methodologies. This study forms part of a research project which suggests:

The research challenges the frequently used and generic approaches adopted to manage the prospect of hazard realization and the floored and counterfactual methodologies selected. The research also aims to offer an insight into the prevailing ideology and psychology demonstrated within the business that created and approved the risk assessment, and within the industry in which the business operates. By analysing the style and the content of the hazard control and mitigation measures adopted within the published and approved risk assessment documents, it also becomes possible to evaluate the safety management system that enabled them.

2. Context and Methods

Assessing risk is a well-established process, it is frequently legally mandated across a variety of legal frameworks, and considerable industrial and academic time has been invested in the creation of a variety of scoring mechanisms, templates, and guidelines. The audience for risk assessment would seem to be very clear. Employers are legally required to protect their employees and others from harm [

15]. Other guidance, however, offers a slightly different perspective. A risk assessment will protect workers and the business and help to comply with the law [

16]. Additionally is was found that workshop attendees and professionals are motivated to protect budgets or engineering designs which led to the underestimation of risk [

17] . Therefore, any loss of competitive advantage, monetary benefit or power and influence has the potential to lead to loss aversion which demonstrates that individuals fear of loss can exceed the pleasure of gain by around 50%.[

18]. The theory of loss aversion (also called prospect theory) has been enhanced and developed by many who support the existence of the theory of loss aversion theory to discuss the effect of losses and its relationship to decision making [

19].

The problem of managing priorities and interpretating information to make informed decisions is not new. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates said that:

“

no two people will ever hear or see the same thing in an identical way and consequently, will never perceive sensory information in the same way either” [

20].

Interestingly Nietzsche (1844-1900) suggested in his notes that ‘

facts do not exist only their interpretations’ [

21]. This comment then evolved into the frequently used quotation that ‘

All things are subject to interpretation and whichever interpretation prevails at a given time is a function of power and not truth’. It is unclear if Nietzsche ever actually said those precise words, but the implications of the statement are of interest.

The psychological way humans interpret data and suggested that bias interferes with rationality and impartiality as we develop our own heuristics or ‘

rules of thumb’ [

22]. Motivational bias is the vulnerability to opinion changes based upon incentivisation, organization pressures and self-interest have the potential to impact any risk assessment and scoring mechanisms adopted to justify the required risk reduction [

23]. It is also suggested that businesses operate in an environment with multiple and often conflicting goals which can be generated in social and organizational contexts [

24] (p168). The suggestion that as humans we perceive and understand differently, poses considerable issues for managing safety and assessing risk which, aligns with another research assumption.

It is suggested therefore that many risk assessments documents and the safety management systems that within which they reside, have been created and subsequently evolved to accommodate a variety of stakeholders, all of whom are susceptible to both confirmation bias and loss aversion which can impair judgement when estimating risk exposure. Additionally, the accuracy of risk estimation has been the subject of a variety of academic studies. Humans are primarily guided by emotion and therefore are distracted by trivial details and are insensitive to the differences between low and negligibly low probabilities [

25]. It is further suggested that, if the only evidence presented is subjective in nature and supplied by those who support the suggested approach then there is no reason to believe the method would not deliver a negative outcome [

26] (p17) (Hubbard, 2009). Hubbard also suggested something of interest for the purposes of this research:

“For a critical issue like risk management we should require positive proof that it works – not just lack of proof it does not.” [

26]

(p.17)

Proving a negative is certainly problematic as the absence of evidence is not evidence of the absence of evidence [

27]. Unfortunately however, the reliance on history to predict future outcomes is prevalent within the Health and Safety Industry which suggests the application of deterministic risk management strategies. In its annual report declaring a variety of health and safety statistics for the global offshore wind industry The Energy Institute advises that, in 2022 the Total Recordable Injury Rate (TRIR) had declined from 3.28 in 2021 to 2.82 in 2022 [

28]. The TRIR is defined by the Energy Institute as “

The number of recordable injuries (fatalities + lost workday injuries + restricted workday injuries + medical treatment injuries) per 1 000 000 hours worked. The deterministic implication here is clearly that past health and safety performance provides a metric for the measurement of current and future health and safety performance. Interestingly however in the glossary of the documentation TRIR is defined as “

The number of fatalities, lost workday incidents, restricted workday incidents and medical treatment injuries per million hours worked”. While the differences between the two definitions may be slight, with the initial definition advising that recordable incidents should be recorded. What is clear is that the definitions are different and therefore there exists the potential for misinterpretation.

The conflict between the deterministic theory of the universe by Albert Einstein (1879-1955) which was based upon Newton’s work, is contrasted by the probabilistic and challenging theory of Quantum Mechanics championed by Bohr (1885-1962). Quantum theory disrupts, undermines, and potentially invalidates many of the foundations on which Health and Safety management systems are built. Quantum theory has profound implications for the way in which the world is viewed. The world is not deterministic as we cannot measure the present state of the universe precisely [

29].

The application of quantum mechanics outside of the physics discipline is still in its infancy despite the fact that the theory is over 100 years old. When discussing the application of quantum theories in the field of Information Management it is suggested that using quantum approaches are still in their earliest stages [

30]. Quantum Mechanics also “

opened new avenues of thought about organizational life” [

31] (p272). Interestingly even the principal founder of quantum theory, Bohr advised that quantum theory had application in social realms [

32]. The use of quantum theory in the social domain is of interest as a fundemental theory of physical reality is not going away, the question therefore is how far will ti travel outside of physics. [

33], which demonstrates that quantum formalisms have considerable applicability [

34].

From a philosophical perspective the 19th century philosopher Nietzsche suggested that to trace something unfamiliar back to something familiar is at once a comfort and a satisfaction. Interestingly Nietzsche goes on to suggest a first principle which is, any explanation is better than none at all [

35]. Nietzsche’s philosophical has been further developed by acknowledging that whist any cause certainly has an effect, the idea of reverse causality is purely an assumption [

36] (p63) which has driven the potentially misguided thinking that the world is linear, all incidents have causes which can be identified and therefore prevented. The implication that the world is not linear, and that reverse causality is a fallacy appears to align well with the fundamental principle of quantum mechanics. It should also be noted that some of the greatest and most esteemed physicists appear to also question causality. Max Planck (1858-1947) advised:

Planck and Murphy (trans) (1932) stated:

“Hitherto the principle of causality was universally accepted as an indispensable postulate of scientific research, but now we are told by some physicists that it must be thrown overboard. The fact that such an extraordinary opinion should be expressed in responsible scientific quarters is widely taken to be significant of the all-round unreliability of human knowledge. This indeed is a very serious situation”. [

37]

Bohr advised that “Causality may be considered as a mode of perception by which we reduce our sense impressions to order”. [

38]. Bohr additionally stated that “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future” [

39]Anker, (2017). Even Albert Einstein (1879-1955) advised that “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a persistent one” [

40]). Perhaps the best and most applicable description of the deterministic and probabilistic paradox which resonates in the management of risk was made by the CERN particle physicist John Bell (1928-1990) who said.

“Bohr was inconsistent, unclear, wilfully obscure, and right. Einstein was consistent, clear, down-to-earth and wrong” [

41].

This study examines the reliability of published and ‘live’ risk assessments used within the renewable industry environment. It is suggested that the traditional idea of reliability means the repeated analysis of a phenomena resulting in the truth [

42]. A total of 102 published risk assessments all kindly supplied by four different renewable energy companies were examined. Each individual risk assessment contained a variety of risk reduction measures (1,018 in total) intended to reduce the risks of hazard realization to a satisfactory level which would fulfil the mandated requirement to manage workplace risks suitably and sufficiently [

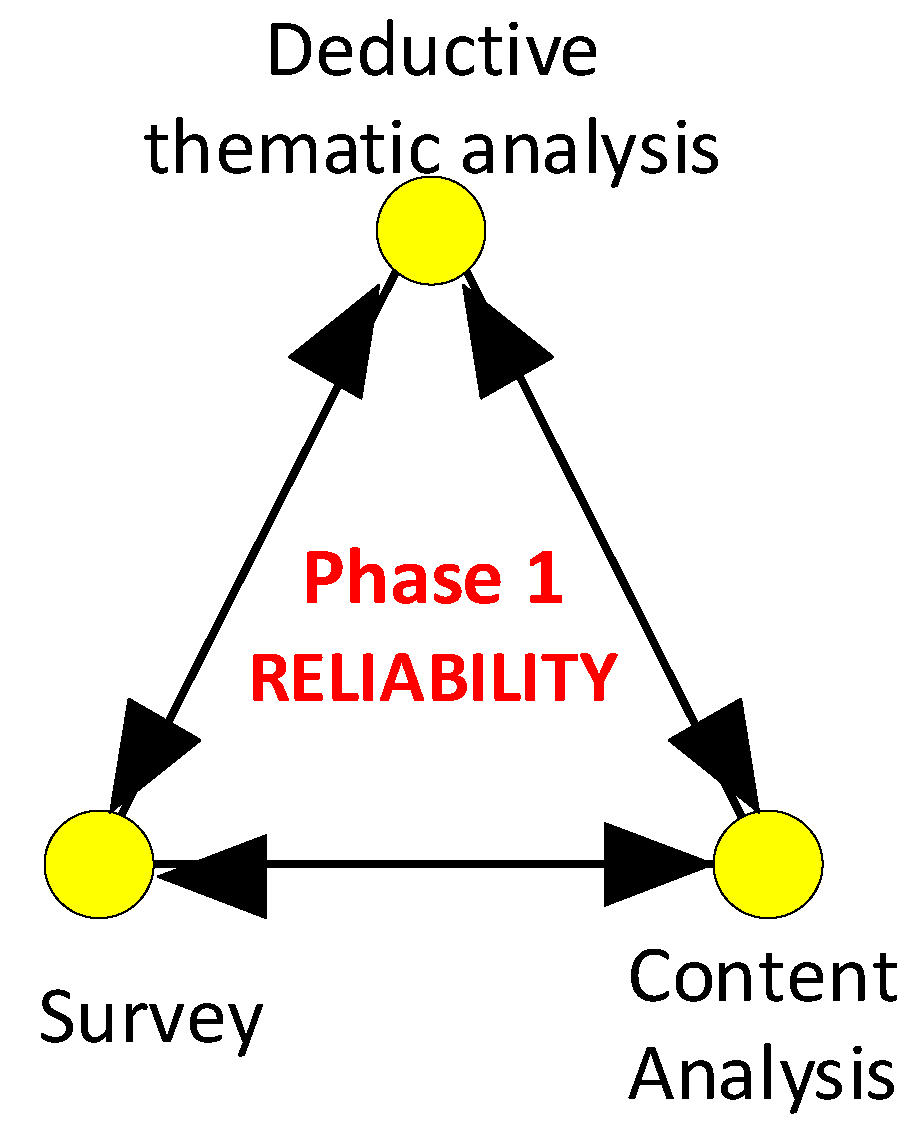

43]. Three methods were selected to analyze the qualitative content:

Content analysis enables the researcher to systematically describe and quantify phenomena [

44], which subsequently allows the researcher to build models or conceptually map categories for analysis [

45].

Thematic Analysis described as descriptive method that reduces the data in a flexible way that dovetails with other data analysis models [

46]

Survey. Described as the collection of information from a sample group through their responses to questions [

47]

By using three differing methods of analysis of the published risk assessments, trends, themes, and codes can be identified all of which indicate a level of reliability of the published documents. Reliability can be estimated by comparing different versions of the same measurement [

48]. The diagram below in

Figure 1 demonstrates how the survey results, content, and deductive thematic analysis combine to deliver evidence-based outputs.

3. Results

3.1. Content Analysis

By undertaking a Content Analysis the frequency of word usage within the published risk assessments can be examined and using NVIVO software. . The NVIVO software is unable to supply theoretical frameworks it simply facilitates data analysis. [

49]. The outputs of the Content Analysis provides inputs for the Thematic Analysis the results of which can then be verified by the results from a survey.

Table 1 indicates the top 10 words used within the text of the Renewable Energy risk assessments. The search criteria examined individual words containing 5 or more letters to avoid grammatical conjunctions such as and, the, so etc. The types of words frequently chosen by the risk assessment author(s) are of interest as they contain a mixture of nouns (7), verbs (2), and adjectives (1).

There were 5 common nouns used which are described as: the type of person, type of thing or place . Additionally, there were 2 abstract nouns used which are described as conceptual and non-physical [

50]. The use of the adjective word ‘

competent’ which was the second highest scoring is also indicative. Adjectives are described as words that are descriptive of the qualities of something or someone and words that modify nouns or pronouns [

51] . The only verb used within the top 10 of frequently used words is the Gerund verb ‘

lifting’ Gerund verbs are simply adding an ‘ing’ to a verb to form a noun [

52].

3.2. Thematic Analysis

The output of the content analysis then contributes to the Thematic analysis of the published risk assessment. Deductive thematic analysis enables the creation of coding which begins with a set of themes or theoretical ideas [

53]. A detailed analysis and reading of the text generate concepts and ideas from which themes are created [

54]. Once the Thematic analysis has developed a series of themes, they can then be used to create a categorization matrix. The categorization matrix can also be used to test research concepts and hypothesis [

55]. The initial categorization matrix created from risk assessment analysis as shown in

Table 2

As risk assessments symbolize the surface level elements of the organization culture Schein (2016) being able to measure the constituent parts of a published risk assessment is of value. Measurement as defined by Hubbard (2014) states that measurement is:

“a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more observations” [

56] (p.31)

The categorization matrix created as part of the initial analysis has certainly reduced the level of uncertainty regarding the reliability of the published risk assessments and dependent on stakeholder requirements the initial categorization may be sufficient. Defining reliability in a qualitative manner however can be problematic. With Qualitative research it has to be acknowledged that human behaviour can be erratic, and measurement and observations can fluctuate when human interactions are being studied [

57].

3.3. Survey Results

This research project is based within the renewable energy industry. Therefore, there is a considerable risk that those being surveyed within the renewable energy businesses will display an element of confirmation bias within their replies. Confirmation bias is described as the interpretation of evidence that aligns with existing beliefs or hypothesis [

58]. Additionally, Cognitive dissonance described as a conflict between two opposing beliefs. can cause the survey participant into a dilemmic situation where loyalty to the company and all that entails is perhaps contrary to professional or competent view [

59].

Cognitive dissonance has a strong link to confirmation bias. To create an unbiased decision every piece of information would require critical analysis; such an undertaking is unrealistic [

60]. To counter the potential impact of confirmation bias or cognitive dissonance it is suggested that confirmation bias effect can be minimized by adopting an alternative hypothesis which also has the potential to deliver a more dynamic form of evidence gathering. [

61]

In this research every effort has been made to ensure the survey results are unaffected by confirmation bias. To achieve this, three approaches were adopted:

The survey participants would not be asked to rate or score the language used as a risk safeguard. They would be asked to categorize the safeguards under the themes developed from thematic/content analysis.

The participants in the survey are volunteers suggested by the Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH). They are all chartered safety professionals; however, they have no knowledge or experience of the renewable energy industry. This approach was adopted as the hazards described in the published risk assessments are generic in nature and therefore occur in other industries. They include working at height, exposure to hazardous substances, exposure to hazardous energies and slips, trips, and falls. [

62]

The safety professionals nominated by IOSH were also asked to nominate friends or family who had no knowledge of the renewable industry and no formal health and safety background.

A total of 5 safety professionals and 5 non safety professionals were surveyed, and the results are listed in

Table 3. Providing a subject group is randomly selected the ‘

rule of five’ is 93.75% accurate in identifying the mean [

63] (p43).

Table 3 enables the contrasting of results from the initail analysis compared to survey results supplied by Safety and non-safety professional randomly selected volunteers

Additionally, “

the lack of having an exact number is not the same as knowing nothing” and that having range of values delivers a 90% confidence level [

64] (p.109).

Table 4 demonstrates that the results of the random surveys and the initial analysis align with the research assumption that

and in doing so provides the risk owner an evidence-based evaluation of the reliability of their published risk assessments.

4. Discussion

By combining the outputs from of the Content Analysis, the Thematic analysis, and with the results from random surveys, it becomes possible to gain an insight into the methodology adopted by the document authors, and the business and industry attitudes towards risk management. While considerable effort and research has been undertaken to guide on risk assessment creation, there is a paucity of guidance available which could offer an evaluation of the content and therefore its reliability if ever tested or scrutinized. The categorization of the published risk assessment language demonstrates how the risk assessment authors have chosen to manage the risks and the assumptions that have been made to create a suitable and sufficient risk assessment, which in turn has been verified by the employer and potentially the industry within which it operates.

Of the 6 codes used to categorize the risk assessments between 33% and 57% of the risk assessment barriers provided the reader with additional instructions while between 13% and 20% made generic statements. Examples include:

“The products for the Work are to be identified to the team leader and additional controls are implemented”.

“Barrier creams are made available for daily use.”

“Adequate ventilation shall be ensured.”

“Take regular breaks”.

“Only approved tooling shall be used”.

As the supply of instructions is a legally mandated requirement [

65] it is suggested that this type of content should only appear in formal work instructions and not form part of a risk assessment that examines the realization of a specific hazard. The precise reason why the inclusion of additional instructions within the risk assessment barriers is unclear although potentially it does indicate a level of confusion between compliance and risk management.

Other legally mandated requirements contained within the risk assessments included, competency, which comprises of between 9% and 16% of total content, and PPE which is between 6% and 12% of the content. Examples include:

“Wear suitable PPE as stated in relevant COSHH assessment when coming into contact with substances hazardous to health”.

“Refer to COSHH assessment for required PPE”.

“Statutory inspections in accordance with legislation shall be completed for all lifting equipment and copies of certificates kept at site”.

“Only trained and competent technicians to carry out lifting work”.

“A written scheme of examination shall be prepared by a competent person and implemented by Management”.

The requirement to suitably train employees to a sufficient level is also a requirement [

66]. As is the requirment to provide suitable Personal Protective equipment which sates:

Every employer shall ensure that suitable protective equipment is provided to his employees who maybe expose to a risk to their health and safety while at work.[

66]

What is also apparent from the categorization matrix and the subsequently developed ranges, is that between 6% and 12% of the risk assessments ask the reader or stakeholder to make choices and between 4% and 9% ask the reader to refer to other documents or processes in order to suitably and sufficiently manage the risk. Such approaches could certainly be perceived as an indication of a generic methodology or the delegation of risk ownership to the end user of the risk assessment document. Examples include:

Waste shall be disposed in accordance with the relevant COSHH assessment.

Work areas and access ways to be kept clear of unnecessary materials and equipment.

Refer to Method Statement for all CoSHH products to be used for task.

Where possible a suitable sized approved lifting bag in good condition shall be used.

Avoid exposure to the body where possible.

During the analysis of the published risk assessments, it also became evident that each of the risk assessment barriers attracted a risk reduction score regardless of the viability of the barrier. The most common approach used was for the risk assessment authors to score the hazard realization in terms of severity and probability. The individual notional scoring of severity and probability is purely judgmental and there seems to be no evidence to support the ratings applied. The multiplication of severity and probability scoring to develop an overall risk score is also without any evidential basis. Once a risk score is established each risk assessment barrier is allotted a risk reduction score which is an additional judgement by the risk assessment authors.

5. Conclusions

The word reliability can be defined as the consistency and trustworthiness of a measure.,[

67,

68,

69]. In order therefore for a risk assessment barrier to be reliable the communication must be clear and unambiguous to the reader. Any misunderstanding or a differing interpretation is a quiescent error described as

:

“a silent and therefore hidden error which has the illusion of normality, but its unforeseen consequences have the potential to endanger”.[

70]

(p.289).

By undertaking a Thematic and Content analysis of the published risk assessments and validating the resultant categorization matrix with a randomly conducted survey, two keys aspects which enable stakeholders to evaluate the reliability of the documents were identified.

16% of all the risk assessments examined contained ‘cloned’ or ‘copy and pasted’ barriers to manage the risk. This demonstrates that despite the constituent parts of the task being assessed having considerable differences such as, environments of operation, machinery differences and staffing variances each constituent part of the task is deemed to be ‘value neutral’ within the risk assessment process. Such a linear approach negatively impacts the reliability of the published document.

The risk assessment categorization matrix developed accurately demonstrates the chosen methods the risk assessment authors have adopted to suitably and sufficiently manage the specific risks on behalf of the business. The categorization matrix therefore permits the risk owners and users of the document to make informed decisions about the reliability of the document content.

The risk assessment authors, and their businesses are confusing risk management with compliance to statutory or procedural requirements. The compliance to statutory or procedural mandated requirements are expectations of the regulator and business stakeholders therefore, supervision and compliance should be managed via audit, inspection, and where appropriate independent analysis and verification.

Risk ratings and risk reductions scores are arbitrary, inconsistent and appear to have no evidential basis.

The use of imprecise language within the published risk assessment, used in parallel with arbitrary and inconsistent scoring mechanisms suggests that the demonstrated risk assessment process is flawed and may not accurately describe the hazard or its controls and mitigations.

The use of imprecise language and questionable scoring mechanisms can also be seen within the whole renewable industry. In its annual report the G+ uses the Total Recordable Injury Rate (TRIR) as the metric for health and safety measurement globally. Having already established there are two different definitions of TRIR within the published document and advised that history is no guarantee of future success, it is also interesting to note that some of the categories used within the TRIR calculations are also imprecise. What is classified as reportable incident within one country specific legal framework may not be reportable in another. Under U.K reporting requirments a report should be submitted to the regulator where:

“Any person at work is incapacitated for routine work for more than seven consecutive days.” [

71]

Under similar requirements specified in the the United States Department of Labor (2022) the reporting requirement is different and advises:

“Any work-related injury or illness that results in loss of consciousness, days away from work, restricted work, or transfer to another job”. [

72]

How the G+ reconcile the differences between the two legislative frameworks is unclear.

In summary by developing a simple tool that enables risk owners to evaluate their own published risk assessments, it has become evident that many of the issues identified within the process of risk assessment creation exist within the industry publications. If we accept the two research assumptions that:

With a few notable exceptions no employee regardless of grade or position within a business would intentionally set out to harm themselves or others in the course of their duties.’

Most employees have a vested interest in the success of their employer so will therefore try to do a good job.

Furthermore, If we then align the research assumptions with the definition of risk which explains that “The etiology of risk exists within the entropic characteristics present when static systems become dynamic” [76] (p.304) and consider that it is for the employer and not the employee to demonstrate that the risks associated with the business activity are suitably and sufficiently managed. It becomes evident that the majority of business risk resides in the noncompliance to statutory or procedural requirements which therefore should be the primary focus of the risk assessment process.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the kind support given in the creation of this paper by the Institition of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) and by the member of the G+ organization who donated a variety of published risk assessment for analysis purposes.

References

- G+ (2023) Delivering world-class health and safety performance in the offshore wind industry Global Offshore Wind Health and Safety Organization. Available online: https://www.gplusoffshorewind.com/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Taylor, T.W. (1911) The Principles of Scientific Management; LCCN 11010339, OCLC 233134; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, London, UK, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- G+ (2023) Global Offshore Wind Health and Safety Organization. Available online: https://www.gplusoffshorewind.com/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Bloch, A. Murphy’s Law Part 2: More Reasons why Things go Wrong. Cornerstone. 1980. ISBN: 1004-1706-645-0.

- Systems Science What is a system? 2020. Available online: http://systems-sciences.uni-graz.at/etextbook/sw2/systems.html (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Miles, G.H. Economy and safety in transport. J. Natl. Inst. Ind. Psychol. 1925, 2, 192–193. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, J.C. Accident Prone. In A History of Technology, Psychology and Misfits of the Machine Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, D. Street Reclaiming: Creating Liveable Streets and Vibrant Communities; New Society Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, W.E. Out of Crisis Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Center for Advanced Engineering Study: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 0-911379-01-0. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.D.; Dekker, S.W.A. Anticipating the Effects of Technological Change: A New Era of Dynamics for Human Factors. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2000, 1, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.; Schurz, G.; Hüttemann, A.; Jaag, S. (2019) Ceteris Paribus Laws", The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. 2019. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/ceteris-paribus.

- de Molina, L. 1659.

- Hollnagel, S. Flight decks and free flight: Where are the system boundaries? ELSEVIER Appl. Ergon. 2007, 38, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.; Jenkins, M. Workplace Substance Management A Bridge for Health and Safety Professionals. Copyright TOX247 publications. T3 Traynor House Peterlee County Durham SR8 2RU. 2023. Available online: https://www.tox247.com.

- HSE. Managing risks and risk assessments at work. 2022. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/simple-health-safety/risk/index.htm (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- ROSPA. What is a risk assessment. 2022. Available online: https://www.rospa.com/workplace-health-and-safety/what-is-a-risk-assessment (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Hunt, D. Naweed, A. The risk of risk assessments: Investigating dangerous workshop biases through a socio-technical systems model. Saf. Sci. 2023, 157, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. PROSPECT THEORY: AN ANALYSIS OF DECISION UNDER RISK. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, L.; Arval, J. Win Some, Lose Some: The Effect of Chronic Losses on Decision Making Under Risk. J. Risk Res. 2007, 10, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.K. Socrates, the Senses and Knowledge: Is there a connection. 2020. Available online: https://www.moyak.com/papers/socrates-truth.html (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Kaufmann, W. THE PORTABLE NEITZSCHE; Penguin Books Ltd: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, D.W. THE FAILURE OF RISK MANAGEMENT: Why Its Broken and How to Fix I; John Wiley and Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-38795. [Google Scholar]

- Montibeller, G.; Von Winterfeldt, D. Cognitive and motivational biases in decision and risk analysis. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 1230–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, S. The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error; Ashgate Publishing: Wey Court Farnham, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7546-4826-0. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. Response Mode, Framing and Information Processing. Effects in Risk Assessment. In New Directions for Methodology of Social and Behavioural Science: Question Framing and Response Consistency; 1982.

- Hubbard, D.W. THE FAILURE OF RISK MANAGEMENT: Why Its Broken and How to Fix I; John Wiley and Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan, C. The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence; Ballantine Books: 1977.

- Energy Institute. Media Release. safety performance improves alongside surge in offshore wind activity. Energy Institute 61 Cavendish Street W1G 7AR. 2023. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/exploring-energy/resources/news-centre/media-releases (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Hawking, S. A BRIEFER HISTORY OF TIME; Transworld Publishers: Uxbridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Melucci, M.; van Rijsbergen, K. Quantum mechanics and information retrieval. Melucci, M., Baeza-Yates, R., Eds.; In Advanced topics in information retrieval; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 125–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, H.; Russell, M.; Roets, Y.; Kriel, H.; Grimbeck, E. Organisational transformation at an academic information service. Libr. Manag. 1999, 20, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, A. Niels Bohr’s times. In physics, philosophy and polity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Derrian, J.D.; Wendtt, A. Quantizing international relation; The case for quantum approaches to international theory and security practice. Secur. Dialogue 2020, 51, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmanspacher, H.; Graben, P.; Filk, T. Can classical epistemic states be entangled? Song, D., Melucci, M., Frommholz, I., Zhang, P., Wang, L., Arafat, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science Series; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Volume 7052, pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, F. Twilight of the idols or how to philosophise with a hammer; Hackett Publishing Company Inc.: Indianapolis, Indiana, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-1 and Safety-11. The Past the Future of Safety Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Planck, M.; Murphy, J.V.; Today in Science History. Where is Science Going? 1932. Available online: https://todayinsci.com/P/Planck_Max/PlanckMax-Quotations.htm#:~:text=It%20is%20never%20possible%20to%20predict%20a%20physical%20occurrence%20with%20unlimited%20precision.&text=In%20'The%20Meaning%20of%20Causality,1949%2C%202007)%2C%20124 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Frisch, O.R. What little I remember; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Anker, D.; Prediction is very difficult especially if its about the future. Cranfield University. 2017. Available online: https://blogs.cranfield.ac.uk/leadership-management/cbp/forecasting-prediction-is-very-difficult-especially-if-its-about-the-future#:~:text=Niels%20Bohr%2C%20the%20Nobel%20laureate,model%20out%2Dof%2Dsample (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Van Dooren, W.; Van de Walle, S. Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a persistent one: Introduction to the performance measurement symposium. 2008. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0020852308098466 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Farmelo, G.; Random Acts of Science. The New York Times. 2010. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/13/books/review/Farmelo-t.html (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Merriam, S.B. Theory to Practice. What can you tell from an N of 1? Issues of Validity and Reliability in Qualitative Research. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 1995, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- U.K Government. The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations. 19 May 1999. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/3242/contents/made (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Klaus, K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Check, J.; Schutt, R.K. Survey research. Check, J., Schutt, R.K., Eds.; In Research methods in education; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, F.; Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples. Scribbr. 2022. Available online: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/reliability-or-validity (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Lewins, A.; Silver, C. Using software in qualitative research: A step-by-step guide; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, J. What Is a Common Noun? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. 2023. Available online: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/nouns/common-noun/.

- Ryan, E.; What is an Adjective. Definition, Types and Examples. 2022. Available online: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-parts-of-speech/adjective/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Caulfield. J. Gerund Noun Definition, Form and Examples. 2023. Available online: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/nouns/gerunds/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Kaefer, F.; Roper, J.; Sinha, P. A Software-Assisted Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles: Example and Reflections [55 paragraphs]. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2015, 16, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, D.W. THE FAILURE OF RISK MANAGEMENT: Why Its Broken and How to Fix I; John Wiley and Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Theory to Practice. What can you tell from an N of 1? Issues of Validity and Reliability in Qualitative Research. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 1995, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, R.S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 2–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, I.; Confirmation bias. Simply Psychology. 2020. Available online: www.simplypsychology.org/confirmation-bias.html (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Casad, B. Confirmation bias. 2019. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Noor, I.; Confirmation bias. Simply Psychology. 2020. Available online: www.simplypsychology.org/confirmation-bias.html (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Starr, S. Survey research: we can do better. J Med Libr Assoc. 2012, 100, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, D.W. HOW TO MEASURE ANYTHING. In Finding the Value of INTANGIBLES in Business; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, D.W. THE FAILURE OF RISK MANAGEMENT: Why Its Broken and How to Fix I; John Wiley and Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- U.K. Government. The Health and Safety at Work Act. 1974. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37/contents (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- U.K. Government. The Personal Protective Equipment Regulations. 1992. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1992/2966/contents/made (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Middleton, F.; Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples. Scribbr. 2022. Available online: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/reliability-or-validity (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Shuttleworth, M.; Wilson, L.T. Definition of Reliability. 2009. Available online: https://explorable.com/definition-of-reliability (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Shuttleworth, M.; Wilson, L.T. Definition of Reliability. 2009. Available online: https://explorable.com/definition-of-reliability (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Hall, T.; Jenkins, M. Workplace Substance Management A Bridge for Health and Safety Professionals. 2023. Available online: https://www.tox247.com (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- U.K. Government. The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations. 2013. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/1471/regulation/6/made (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- United States Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Adminstration. OSHA Injury and Illness Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements. 2022. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Hall, T.; Jenkins, M. Workplace Substance Management A Bridge for Health and Safety Professionals. 2023. Available online: https://www.tox247.com (accessed on 29 July 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).