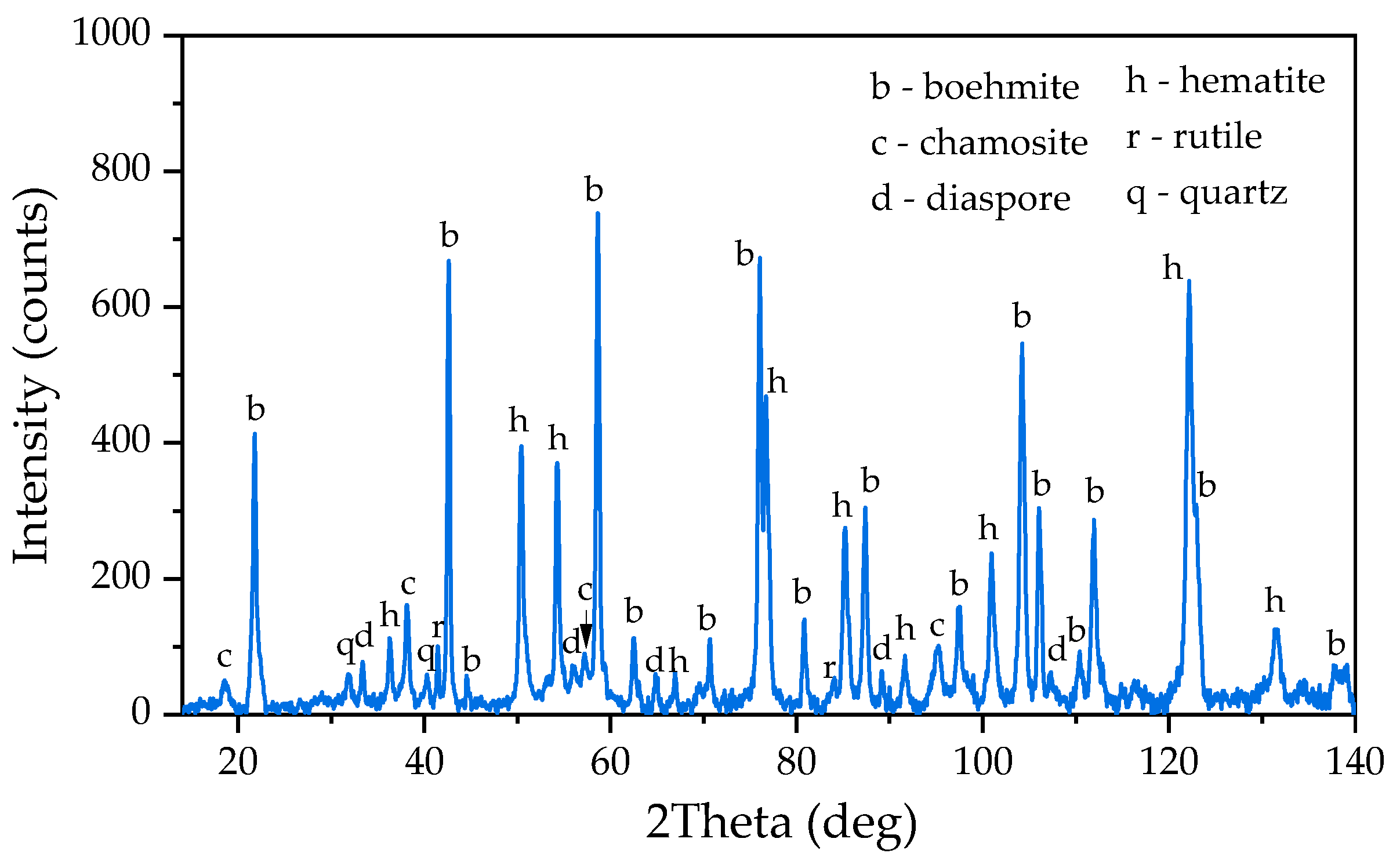

3.1. Voltammetric measurements during electroreduction of iron minerals in suspension of the raw bauxite in alkaline solutions

The reduction efficiency of hematite in a suspesion obtained by mixing BR from the MYTILINEOS Aluminium of Greece with 50% NaOH (591.1 g L

–1 Na

2O) solution [

24] is strongly dependent on the process temperature and the concentration of solid. The present study uses the Bayer process solution, in which a bauxite is subsequently leached for alumina extraction, and an alkaline solution with a concentration of 400 g L

–1 Na

2O, to carry out similar investigations.

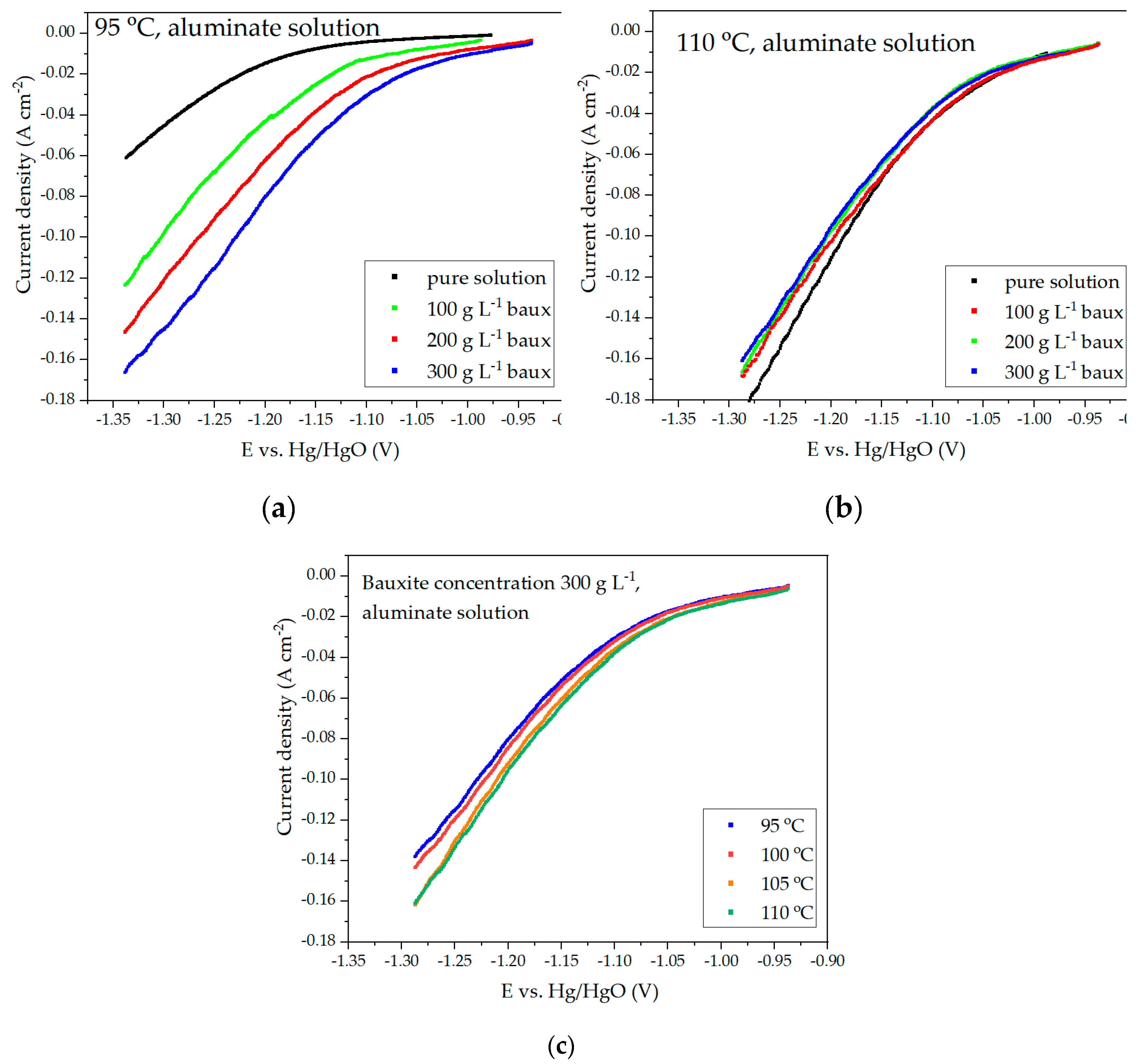

Figure 4 shows the results of voltammetric measurements using a solution containing 150 g L

–1 Al

2O

3 and 300 g L

–1 Na

2O (Bayer process aluminate solution)

As the aluminate solution used in the Bayer process contains only 300 g L

–1 of caustic alkali, its boiling point is lower than that observed in studies using a solution with a concentration of 591 g L

–1 Na

2O [

24]. Therefore, the maximum temperature to which the solution was heated at atmospheric pressure in our experiments was 110 °C. The course of the voltammetric curves shown in

Figure 4a and 4b is significantly altered by increasing the amount of solid. Based on the data presented in

Figure 4c, it can be observed that the overvoltage at the cathode decreases with increasing temperature. If the rate of hematite reduction with a rise in cathodic potential is faster than the rate of hydrogen evolution, it may result in a decrease in the current share of the side reaction of hydrogen evolution and, consequently, an increase in the present efficiency.

As the temperature increases, a gradual convergence of the curves at various concentrations of solid in the suspension is observed. At 110 °C, the current density for a concentration of 300 g L–1 is even lower than for 100 and 200 g L–1. This may be due to a decrease in concentration and kinetic limitations for hematite reduction, as well as a decrease in overvoltage during hydrogen release. The true cause can be found by looking at how the current efficiency changes under different electrolysis conditions.

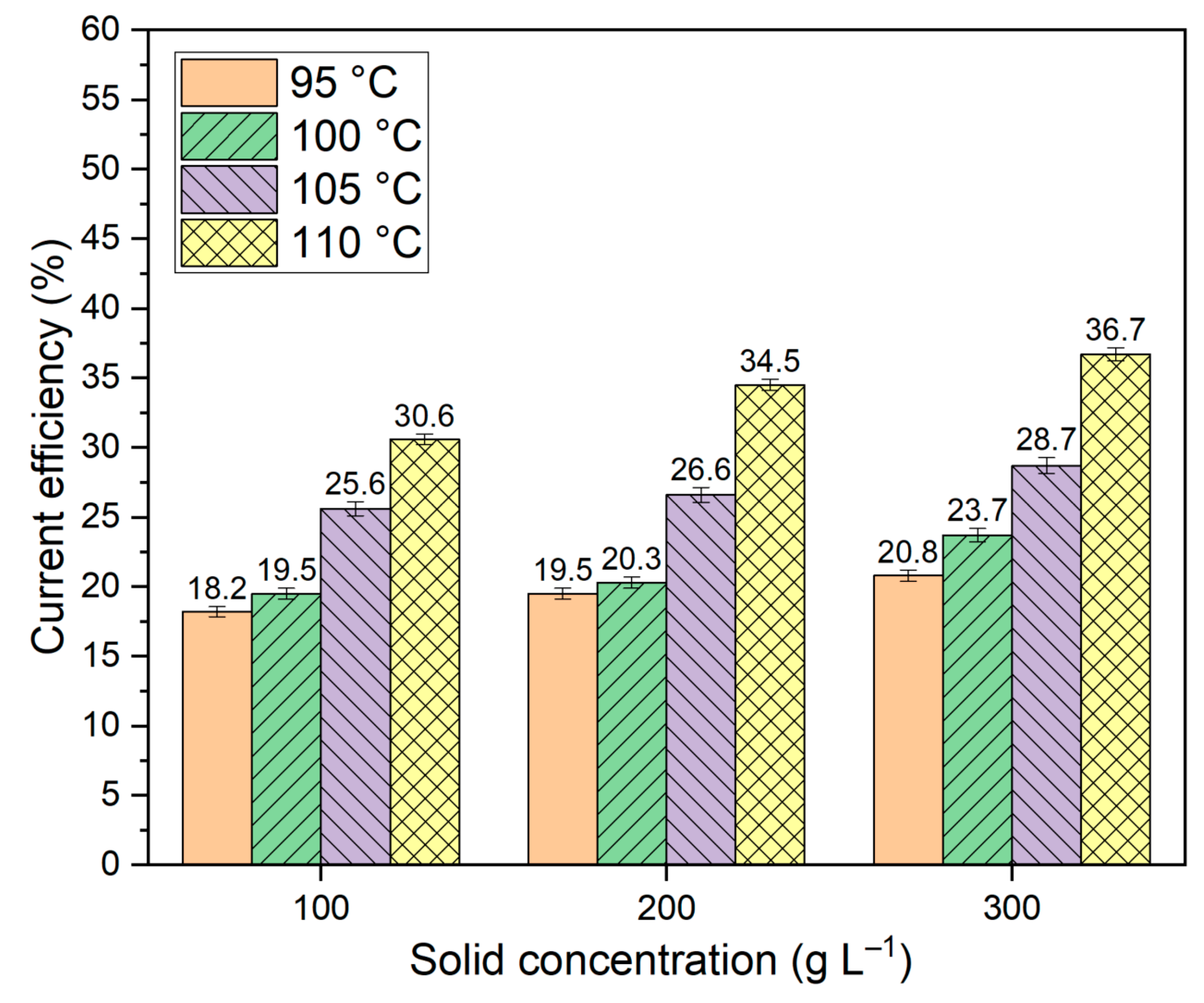

Further, the electrolysis was carried out for 2 h at different temperatures and solid concentrations (similar to the conditions of voltammetric curves in

Figure 4) under potentiostatic conditions at a potential of –1.15 V, which, according to literature data, corresponds to the beginning of reduction of hematite and magnetite to elemental iron [

25,

30]. The results of determining the current efficiency of electrolysis are shown in

Figure 5.

The data presented in

Figure 5 indicates that as the temperature rises, the proportion of current directed towards the reduction of iron minerals increases. The decrease in polarization with increasing temperature and increasing concentration of solid in the suspension is due to a stronger influence of these factors on the rate of hematite and other iron containing minerals reduction than their influence on the rates of side reactions.

At the same time, the current efficiency of the process of reducing hematite with a suspension of bauxite in an aluminate solution is inefficient because most of the current is still used to release hydrogen. In the process of reducing iron minerals with a suspension in an aluminate solution, all the iron was deposited at the cathode, and the amount of magnetite or iron in the solid residue was small. The investigation of the morphology of the solid precipitate on the cathode is shown in Section 3.4.

According to literature data, the electroreduction of hematite involves the transfer of iron into solution and the formation of Fe(OH)

4– complexes, which are then reacted at the cathode to produce dendritic iron. [

22]. There is a possibility of the formation of Fe(OH)

3– complexes, which in turn interact with hematite to form magnetite (Equation (5)). When using the aluminate solution of the Bayer process, the rate of dissolution of iron is very low. Otherwise, leaching in the refinery would produce solutions with a higher iron content, which in practice is not observed even with the use of high-pressure processes. This explains the low efficiency of the hematite electroreduction process using the aluminate solution as well as the low amount of magnetite in the solid residue.

The studies were continued using an alkaline solution without dissolved alumina at a concentration of 400 g L

–1 of Na

2O. According to our previous studies [

27], this concentration is sufficient for the formation of magnetite from hematite in the presence of iron (2+) at temperatures above 110 °C, indicating the dissolution of hematite. Furthermore, this concentration permits the suspension temperature to reach a temperature of 130 °C at atmospheric pressure [

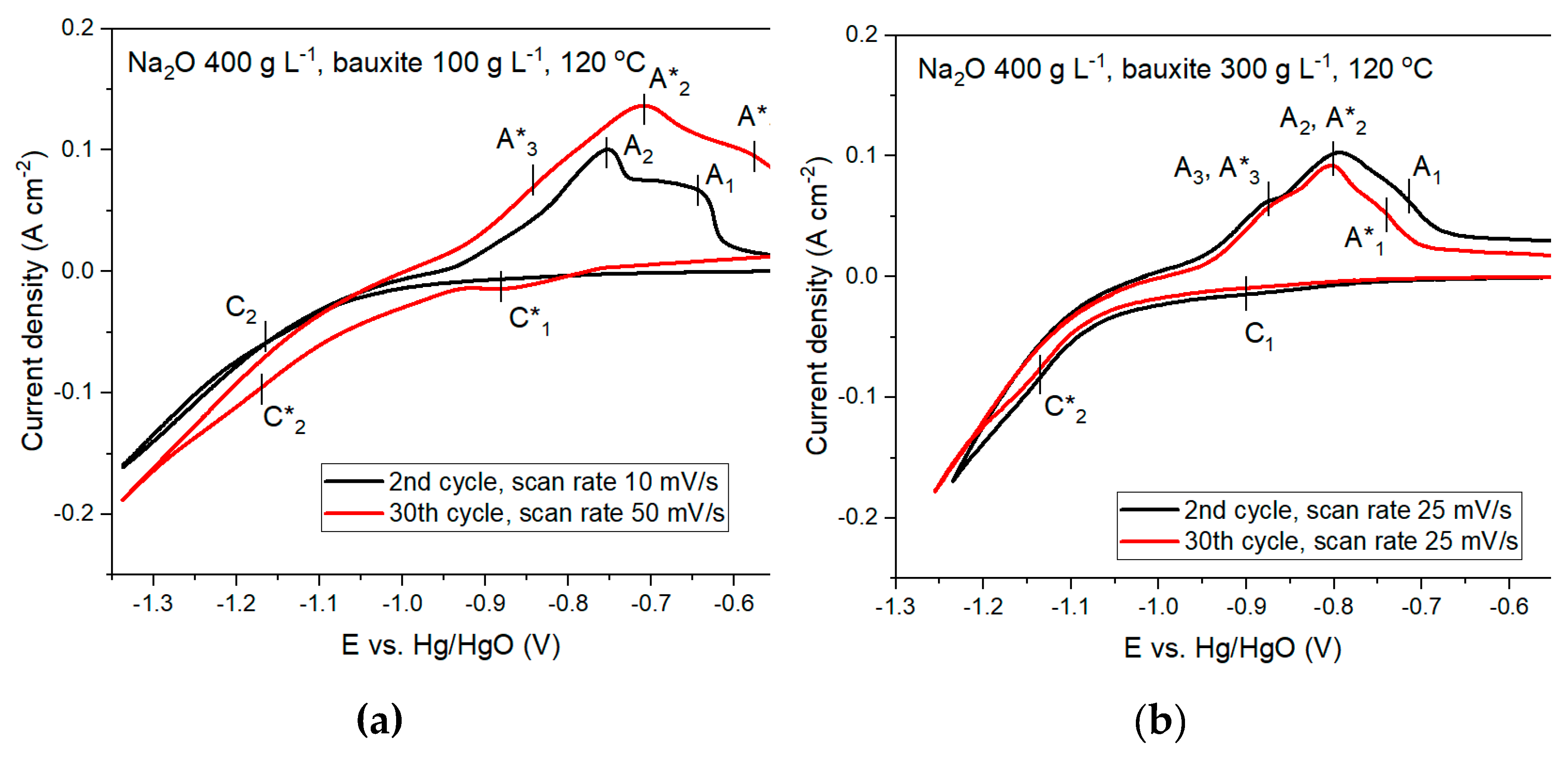

31]. The results of cyclic voltammetric (CV) measurements using a solution containing 400 g L

–1 Na

2O at 120 °C are shown in

Figure 6. To detect cathodic and anodic peaks, measurements were carried out at different scanning rates of 10 to 50 mV/s for 30 cycles.

According to Figures 6a and 6b, increasing the amount of solid in the suspension from 100 g L–1 to 300 g L–1 leads to significant depolarization and an increase in the current density under otherwise equal conditions. This may indicate an increase in the rate of both the main and side reactions due to a decrease in the required overvoltage for the reaction to proceed. Figures 6a and 6b show that there are several cathodic and anodic peaks on the CV curves. The current C1 with a potential E of -0.88 V was detected at the highest scan rate after 30 cycles and with a low solid concentration. According to research [

25], this current is caused by the formation of iron (2+) compounds. It can be both the formation of Fe(OH)

2 and the reduction of iron (3+) hydroxocomplexes according to the Equation (3). The current C

2 is difficult to distinguish at a solid concentration of 100 g L

–1 in the suspension, but becomes more distinct after 30 cycles at a solid concentration of 300 g L

–1 at E = –1.14 V. This current is attributed to the reduction of magnetite and hematite to Fe [

30]. In the initial stages of scanning at low scanning speed, the cathodic peaks are not visible because they are overlapped by the side reaction of hydrogen evolution, which becomes predominant at cathodic potentials greater than 1.15 V.

At all concentrations of solid in the suspension, the anodic peaks are more distinct, since the oxidation process is not accompanied by the release of hydrogen. Peaks A

1 and A

3 are only visible as shoulders, while peak A

2 is clearly distinguishable. According to Monteiro et al.[

25], the A

1 peak observed at a potential higher than E = –0.75 V can be attributed to the oxidation of compounds formed at the cathodic potential in the current C

1 region. The A

3 peak refers to the oxidation of Fe to Fe(OH)

2, and the A

2 peak refers to the oxidation of Fe to Fe

2+ and the simultaneous completion of the oxidation of compounds formed at the A

3 current.

The potentiodynamic curves in Figures 6c and 6d show that, with increasing temperature, the current density significantly increases over the entire potential range at the cathode for pure solution (without bauxite) and for electroreduction from suspensions, which also indicates a general increase in the rate of the process. However, increasing the concentration of the solid phase in the suspension leads to a decrease in current density, which may indicate a decrease in the rate of the side reaction of hydrogen evolution.

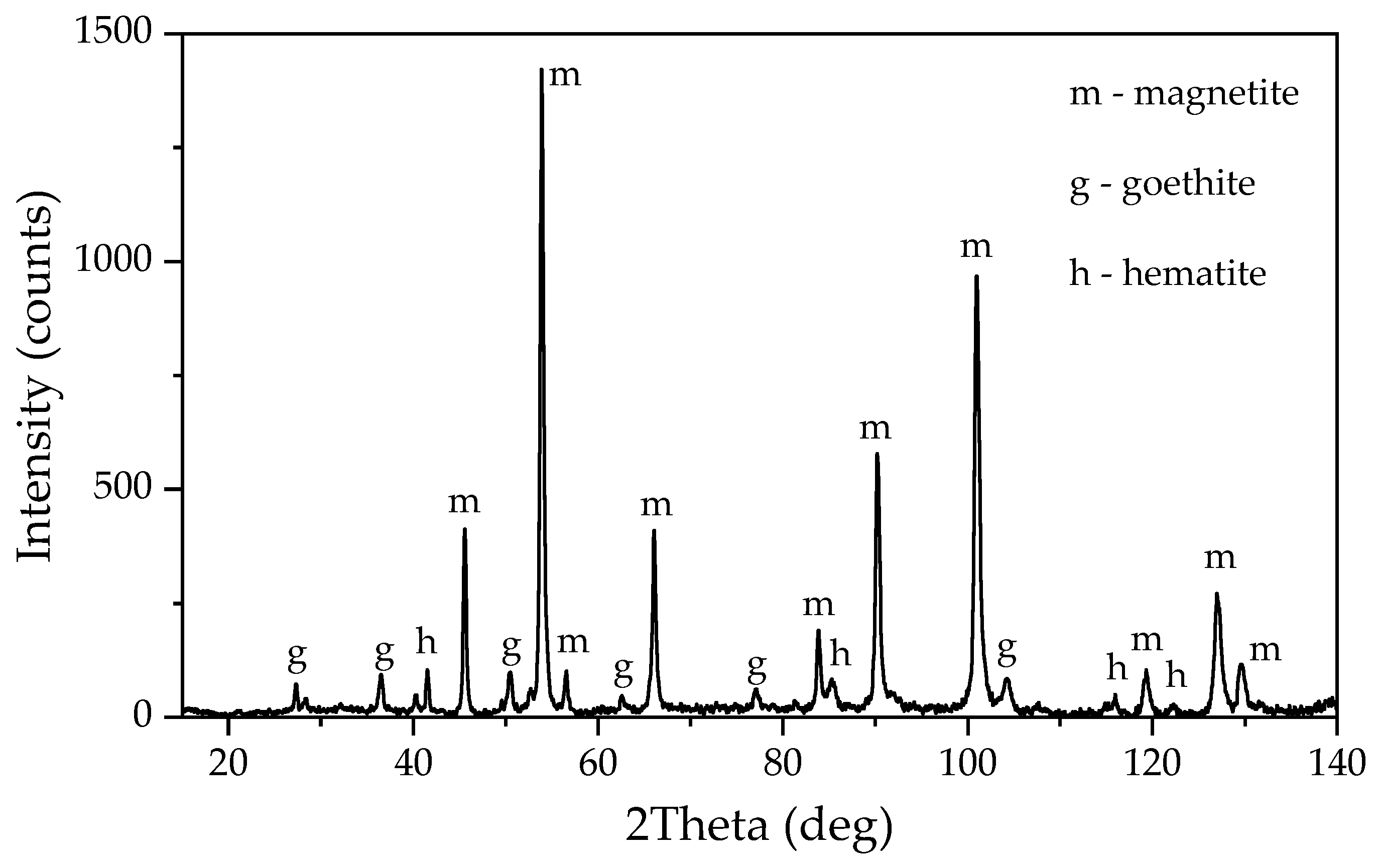

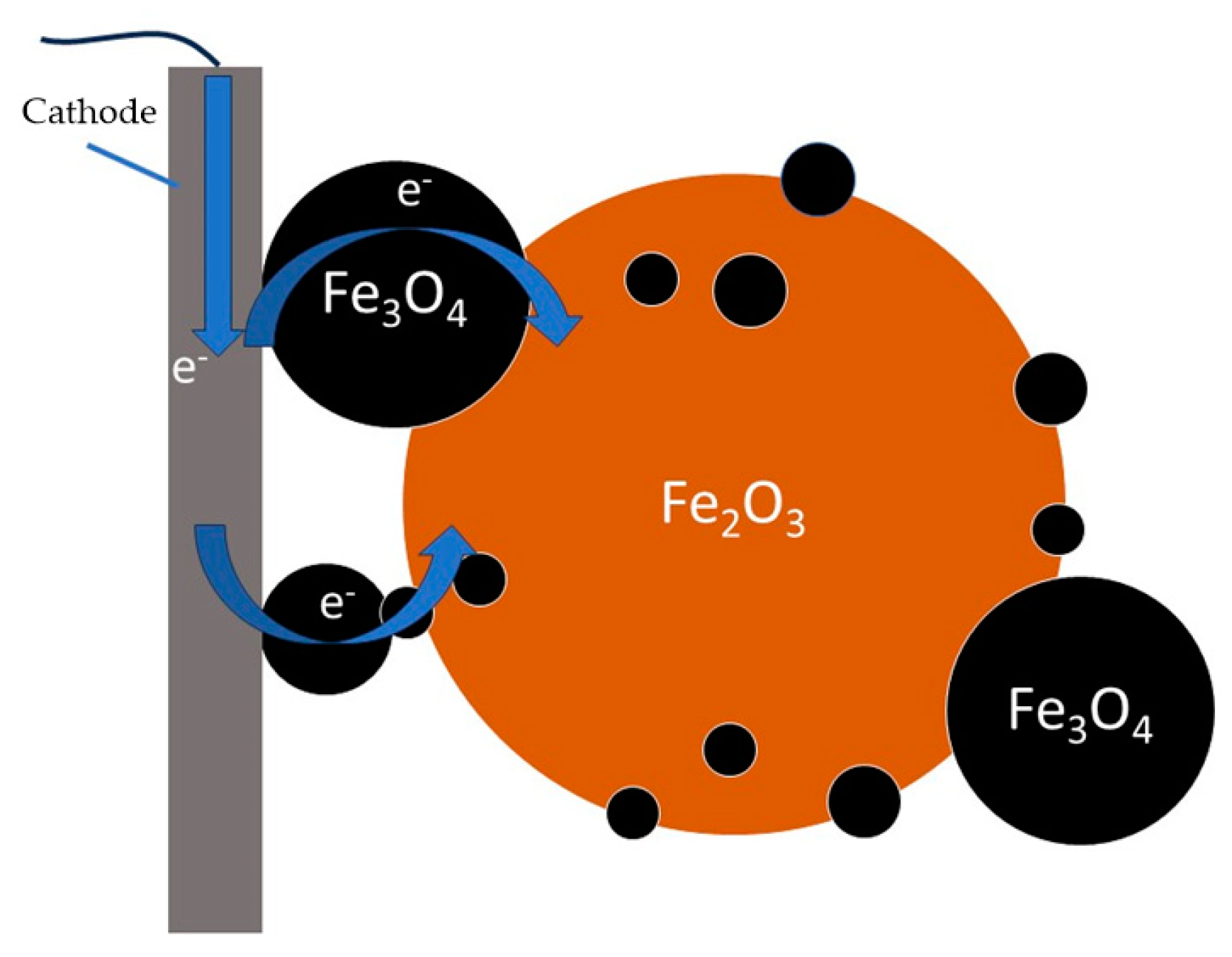

he higher content of magnetite in the precipitate was observed when using an alkaline solution, which may be due to the faster formation (at increased alkali concentration and high temperature) of Fe(OH)

4– complexes, which are then reduced at the cathode to produce Fe(OH)

3–. The latter interact with hematite to form magnetite. The artificial addition of magnetite to bauxite results in a slight increase in the current density at the same concentration of bauxite in the suspension, which may indicate an increase in the reduction rate. It's possible that adding electroconductive magnetite [

18], increases the area of contact between hematite particles and the cathode by the mechanism shown in

Figure 7. However, the addition of magnetite may increase the amount of iron-containing solid phase in contact with the cathode, which may also have a positive effect on the current efficiency. Nonetheless, the current efficiency of magnetite reduction in [

18] was significantly lower than that of hematite reduction. The low current efficiency of the magnetite reduction process, its intensive formation under specific conditions, and its electrically conductive properties have resulted in a considerable amount of complexity in the description of the process involved, necessitating further investigation.

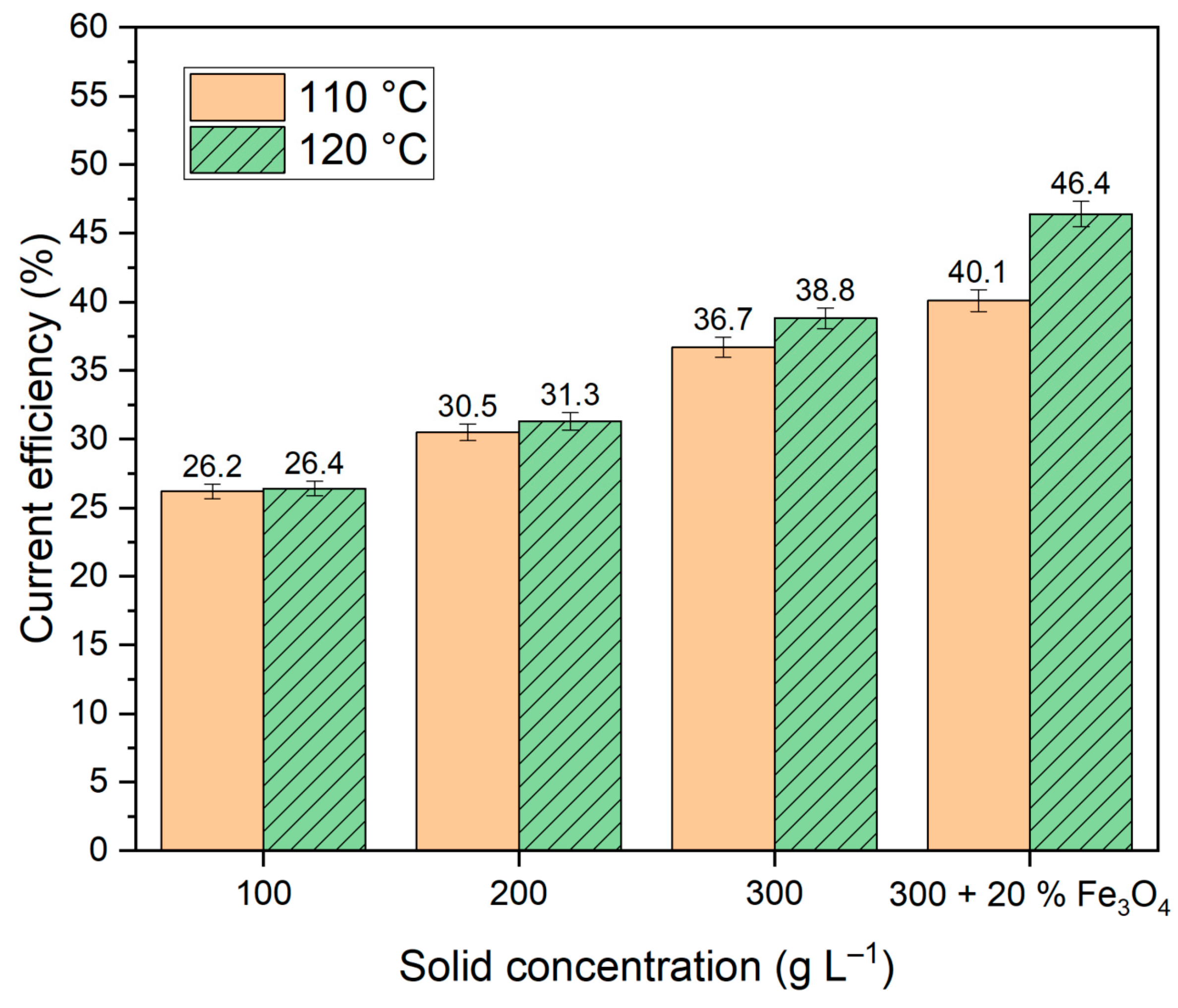

In contrast to electroreduction using an aluminate solution, the use of a relatively well dissolving hematite alkali solution leads to a decrease in current density at all temperatures relative to the pure solution (

Figure 6), indicating an increase in the proportion of current going to the reduction of iron minerals in bauxite. Using an alkaline solution with a concentration of 400 g L

–1 increases the total current efficiency at all concentrations and temperatures, as shown in

Figure 8.

It is evident that the addition of magnetite resulted in an enhancement of the current efficiency (

Figure 8). Nevertheless, the obtained values of current efficiency are lower than those shown in studies [

23,

24], where the reduction of hematite from BR was carried out in a suspension of 50% NaOH solution. It can be associated with increased hydrogen evolution in our experiments due to the low concentration of the alkaline solution and the use of bauxite with a much lower iron content.

It is possible to conclude that, in order to increase the efficiency of bauxite iron minerals reduction, it is necessary to use an alkaline solution with a Na2O concentration greater than 300 g L–1, to increase the concentration of bauxite in suspension, and to add magnetite to bauxite, to maintain the cathodic potential below 1.15 V to reduce the share of current going to hydrogen release. The amount of solid in the suspension could be increased by using a thickening process and a bottom current supply that is in good contact with the entire volume of solid phase, thereby creating a bulk cathode.

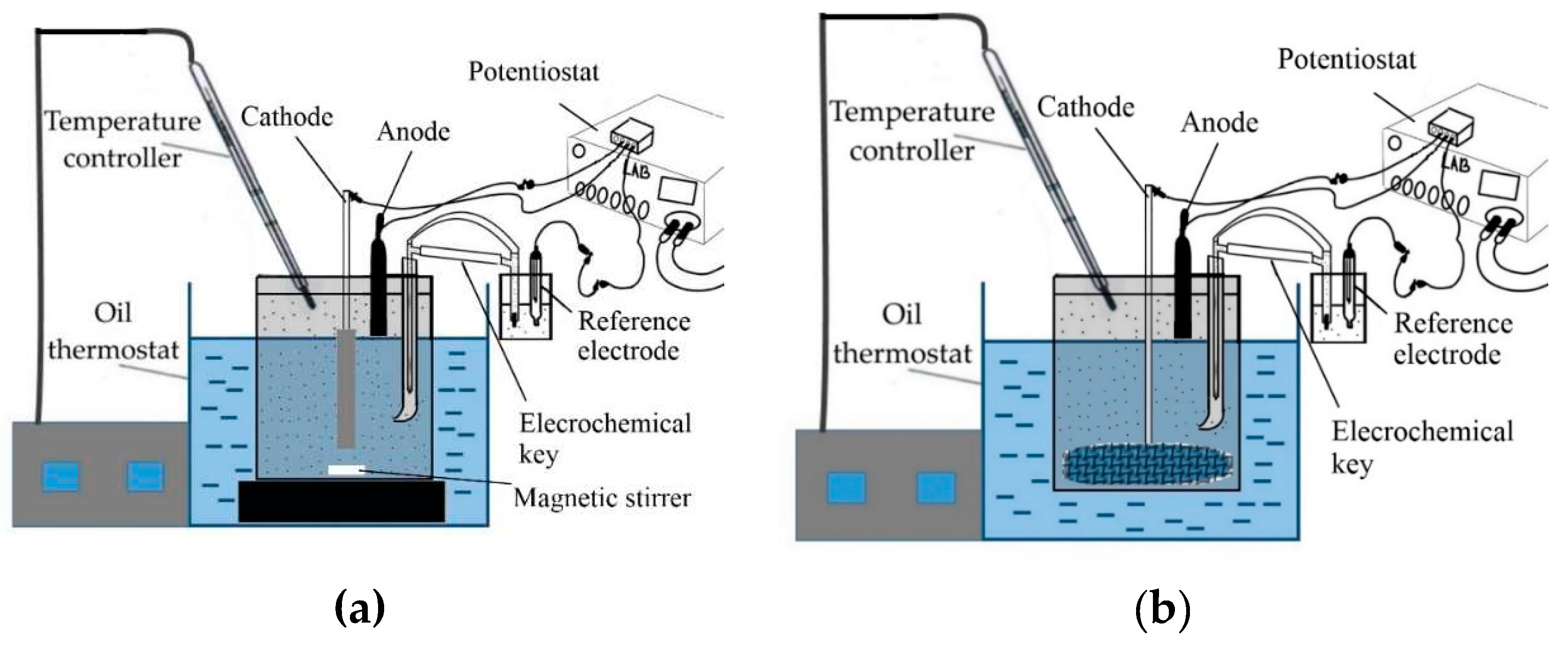

3.2. Electroreduction of bauxite iron minerals using thickened slurry and mesh current supply (bulk cathode)

As demonstrated in the previous section, increasing the concentration of solids in the suspension can significantly increase the efficiency of bauxite iron minerals reduction. In the subsequent experiments, a stainless steel mesh current supply was utilized at the bottom of the beaker (

Figure 3b). This supply was surrounded by bauxite particles during the thickening process, resulting in a significant increase in the quantity of solid in the cathode zone. The results of voltammetric measurements and electrolysis in the galvanostatic regime using a 110 cm

2 current supply mesh are shown in

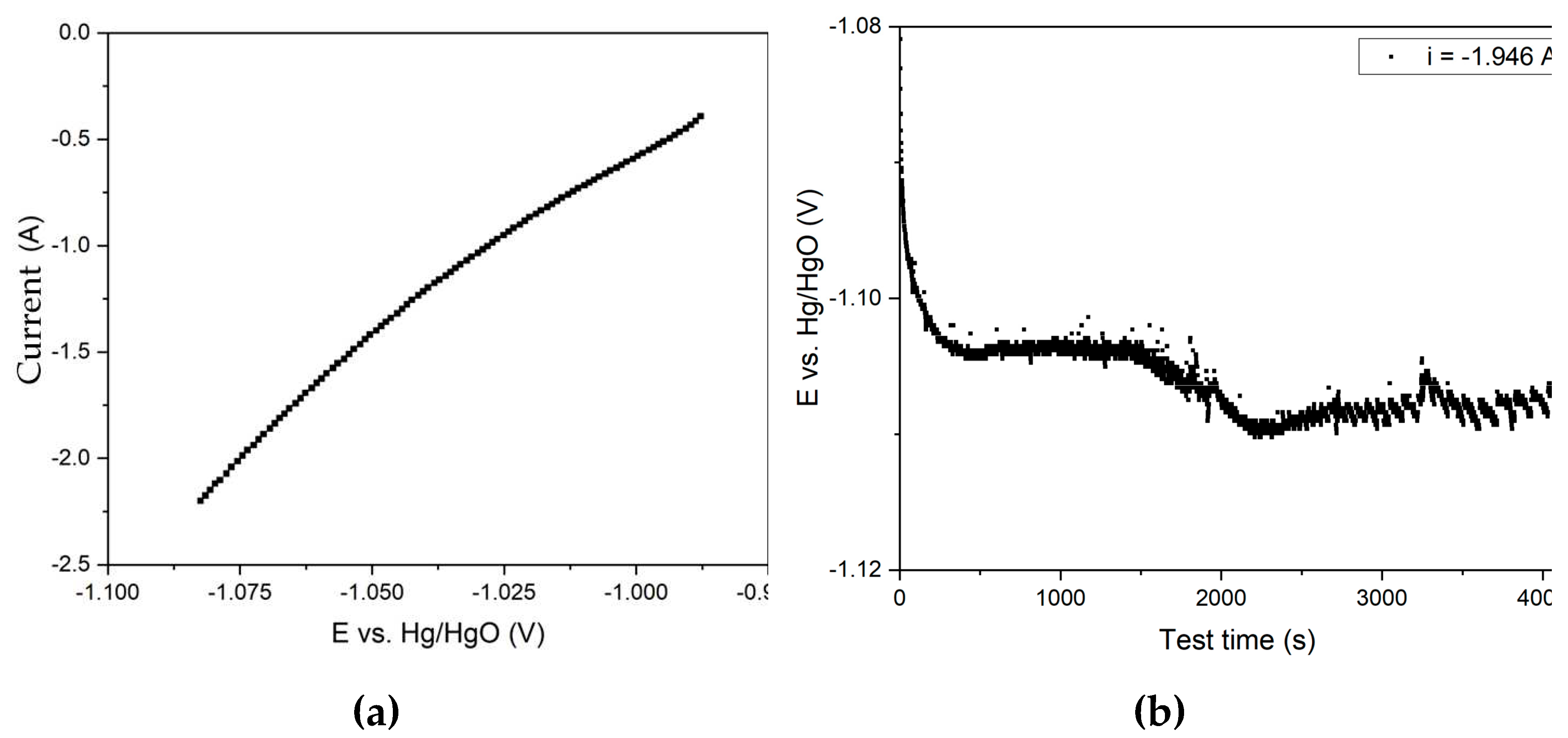

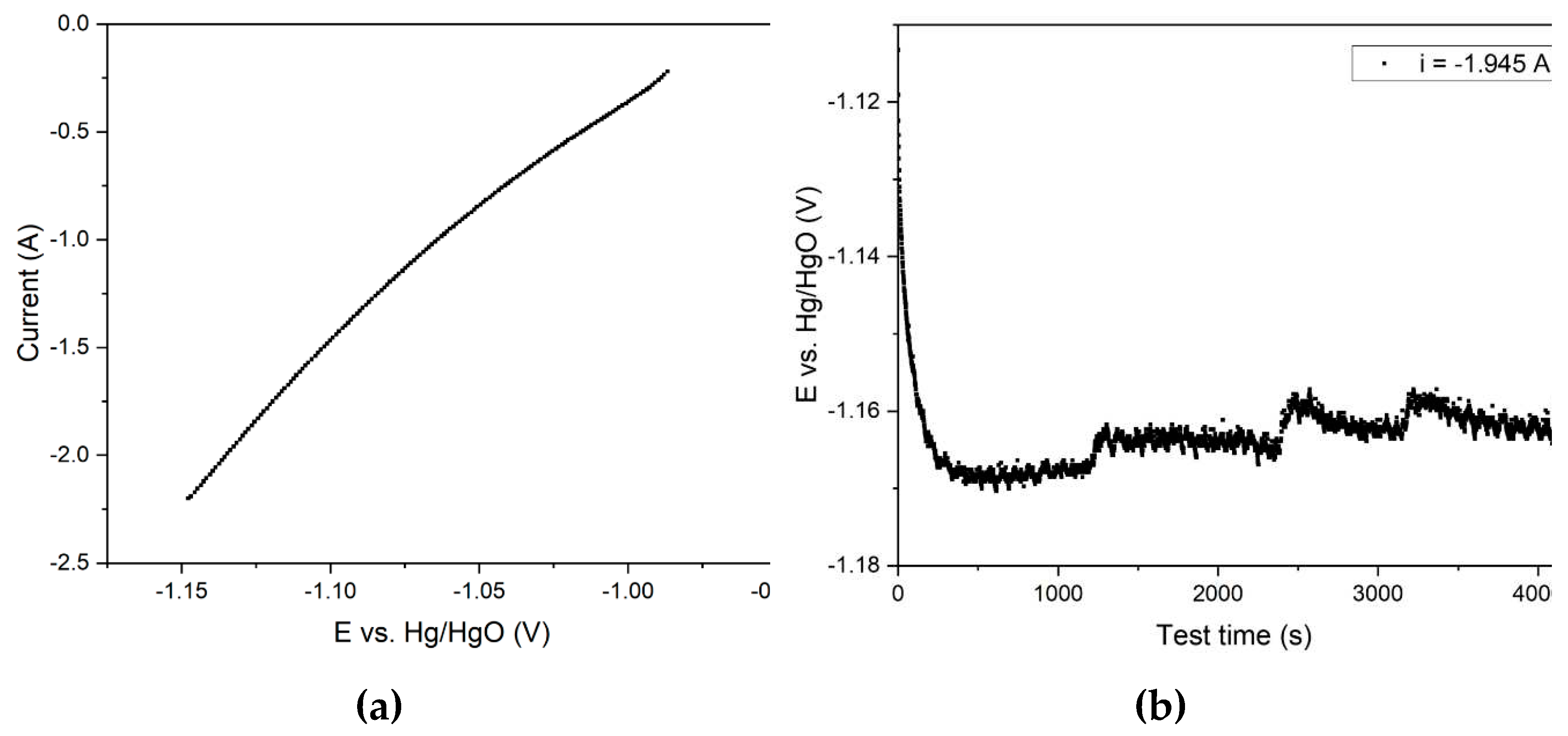

Figure 9.

The figures in

Figure 9 reveal that the cathodes potential was extremely low, corresponding to the initial almost straight line in

Figure 6d. The current density in this section increases linearly with potential, and there is no visible hydrogen release, which begins to progress at high overvoltage.

At the beginning of the electrolysis process (

Figure 9b), an increase in potential from -1.080 V to -1.104 V was observed, followed by the establishment of a stable potential up to 1500 s (25 min), which allows the process rate to be maintained at the same level. As the test duration increased, there was an increase in overvoltage, which may be attributed to the completion of the reduction of particles contacting the current supply. A constant change in the suspension's color to black was observed during the process, which may be due to the beginning of magnetite reduction. The presence of magnetite on the surface of the particles makes it difficult to access the inner layers. This is due to the fact that the current efficiency for the conversion of pure magnetite to iron in alkaline medium is rather low and strongly influenced by the porosity of the sample [

25]. After 4200 s of electrolysis, the degree of conversion of Fe (3+) species to magnetite was 46.0%, which corresponds to a current efficiency coefficient of 60.7%. The yield of solid residue was 46.7%, which indicates almost complete (> 85%) dissolution of alumina after 1 h of desilication and subsequent electrolysis.

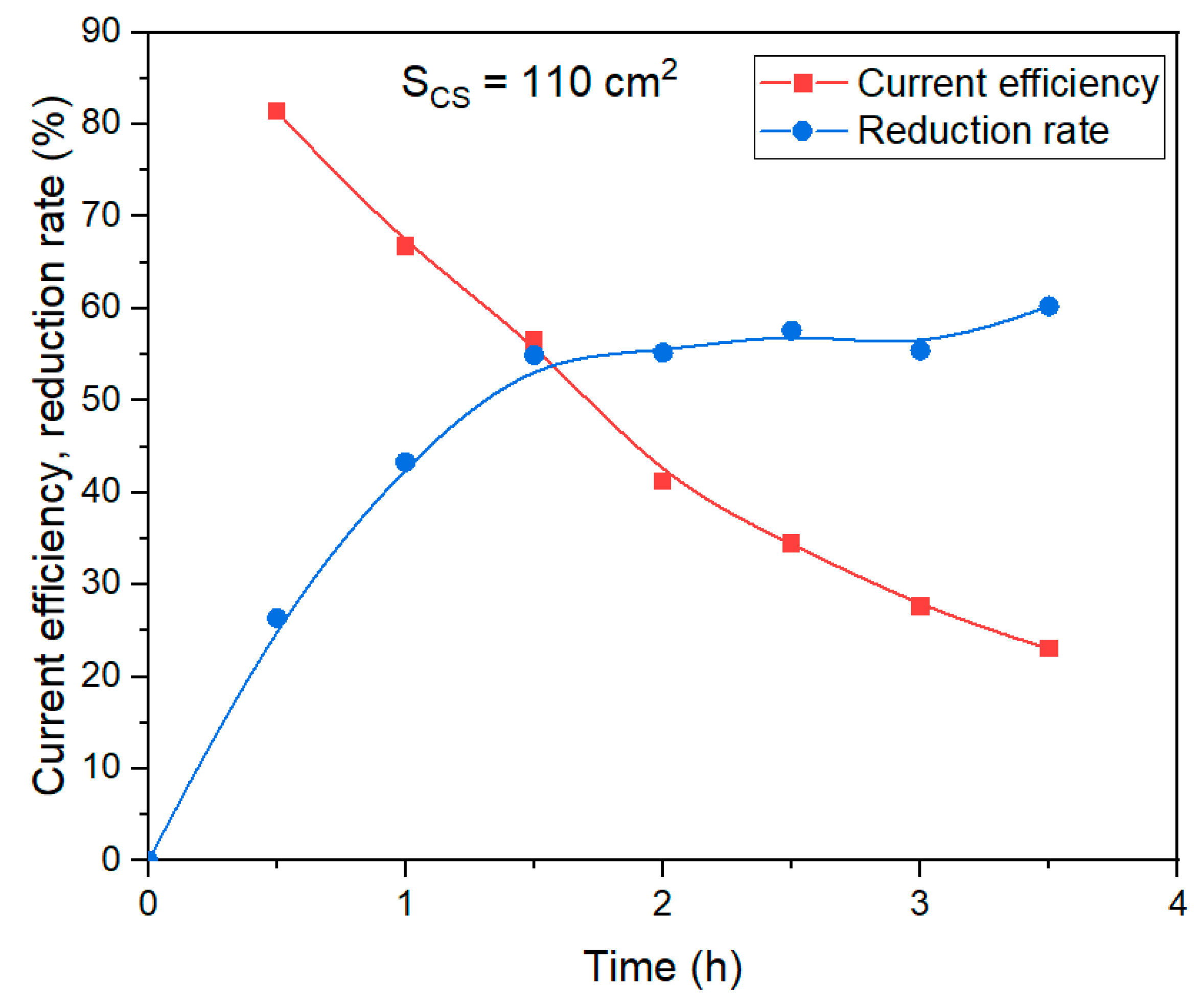

A series of experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of the duration of electrolysis with a 110 cm

2 mesh current supply on the degree of Fe (3+) species and the current efficiency coefficient. In these experiments, all other conditions were the same, and the duration of electrolysis varied from 30 min to 210 min.

Figure 10 shows the results of the experiments by changing the duration of electrolysis.

After 30 min of electrolysis, there is a noticeable decrease in the rate of reduction, and the current efficiency coefficient begins to decrease. After 3.5 h, the maximum reduction rate was 60.2%, but the current efficiency decreased from 81.4% after 30 min to 23.0% after 210 min of electrolysis. Thus, the process of iron minerals reduction is likely limited by diffusion through the magnetite layer formed on the surface of the reacting particles. The evidence supporting this conclusion will be presented in the subsequent section. This explains the increase in overvoltage observed after 25 min, as shown in

Figure 9.

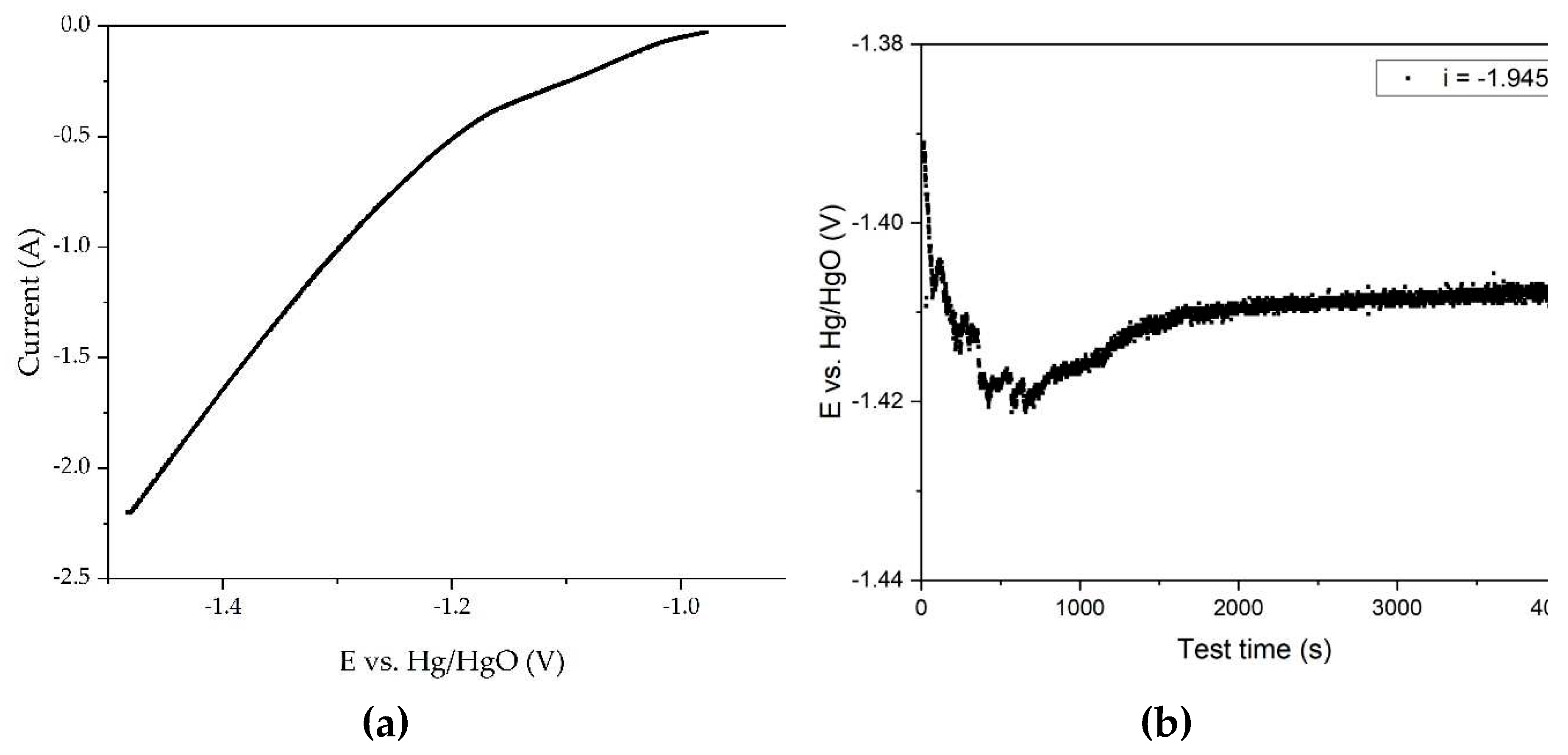

The experiments were continued using a 40 cm

2 mesh current supply, all other conditions being equal. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 11.

It is obvious that reducing the area of the current supply allows for achieving a much higher potential (

Figure 11a). The curve in this case has three sections: the first straight line, which reaches a potential of -1.02 V, followed by a transient mode, where the current at -1.10 V, which corresponds to the current C

2 in

Figure 6b, can be seen. It is therefore possible that this section is responsible for the reduction in metallic iron. A sharp increase in current begins at a potential of -1.2 V, accompanied by a greater release of hydrogen.

The time dependence of the potential in the galvanostatic regime (i = 1.945 A) as depicted in

Figure 11b exhibits an inverse correlation in comparison to

Figure 9b. At first, there is a slight increase in the potential, which can be explained by the deterioration of the contact between bauxite particles and current supply with intense hydrogen evolution at a given current density. After 900 seconds of electrolysis, the potential at the cathode increases from an initial value of -1.390 V to -1.421 V. Then a constant decrease of the potential to -1.410 V is observed. Then a constant decrease of the potential to -1.410 V is observed. In these experiments, no severe darkening of the slurry due to magnetite formation was observed, and it is likely that most of the iron minerals were converted to iron. It is possible that the decrease in overvoltage is due to the increase in cathode area caused by formed iron on the surface of the current supply. The residue from electrolysis with a small area current supply was then leached at 250 °C for 30 min in a Bayer process aluminate solution. The degree of iron (3+) deoxidation to magnetite was 38%.

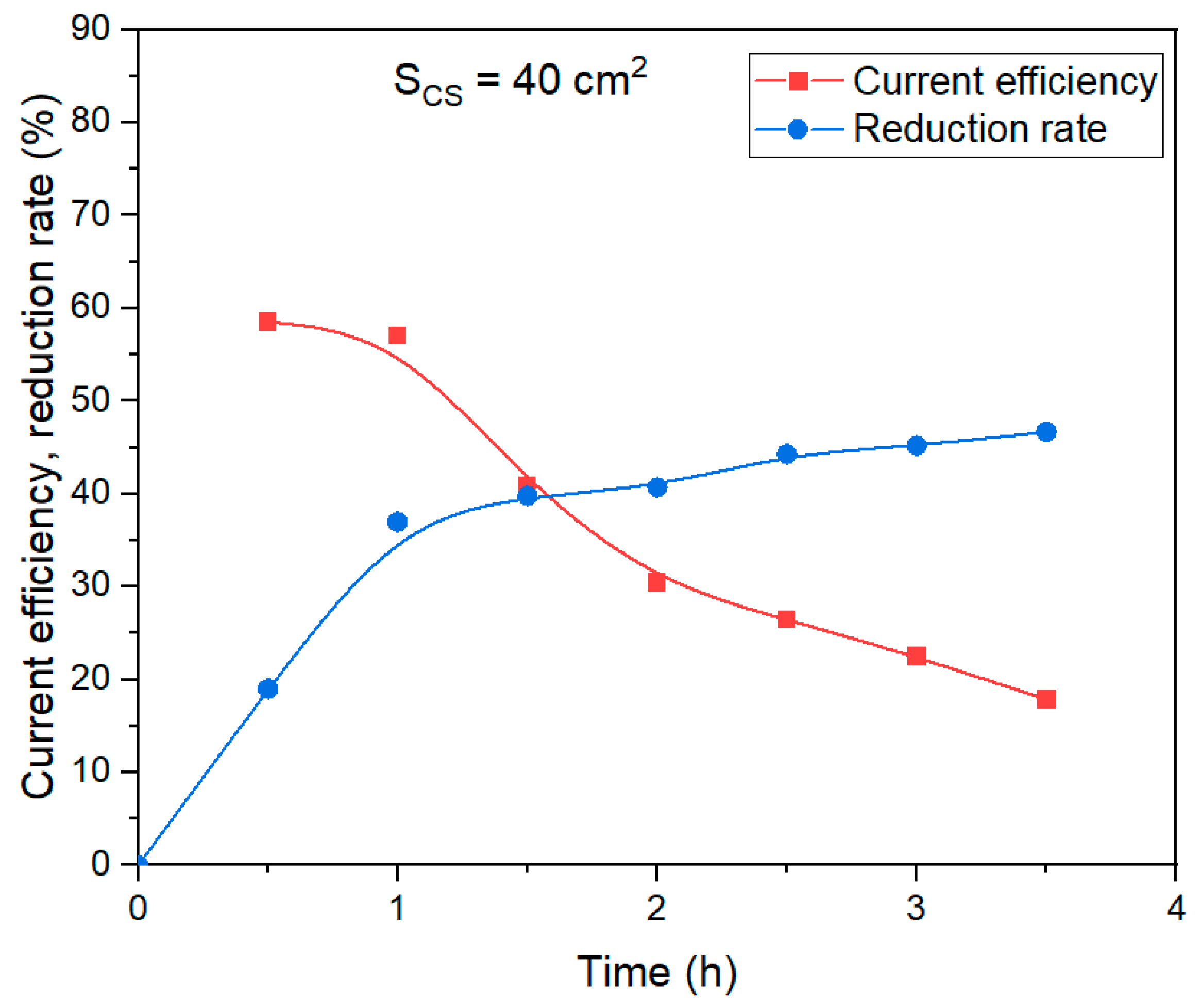

In contrast to the experiment with the use of a large area current supply, this experiment did not observe a noticeable change in the color of the solid residue. Therefore, the proportion of current used to magnetite formation was less. When studying the effect of the duration of electrolysis on the degree of reduction and current efficiency using 40 cm

2 current supply (

Figure 12), a decrease in the efficiency of the process with time was observed, but a sharp decrease began not after 30 min, but after 1 h of electrolysis. The current efficiency coefficient was lower than when a larger area current supply was used.

The yield of solid residue using a smaller area of the current supply (experiment, the results of which are shown in

Figure 11b) was 51.7%. After leaching this solid residue in Bayer solution at 250 °C for 30 min, the yield of BR decreased to 34% (Al extraction higher than 97 %).

High overvoltage leads to a lower degree of reduction and, therefore, a low current efficiency coefficient (

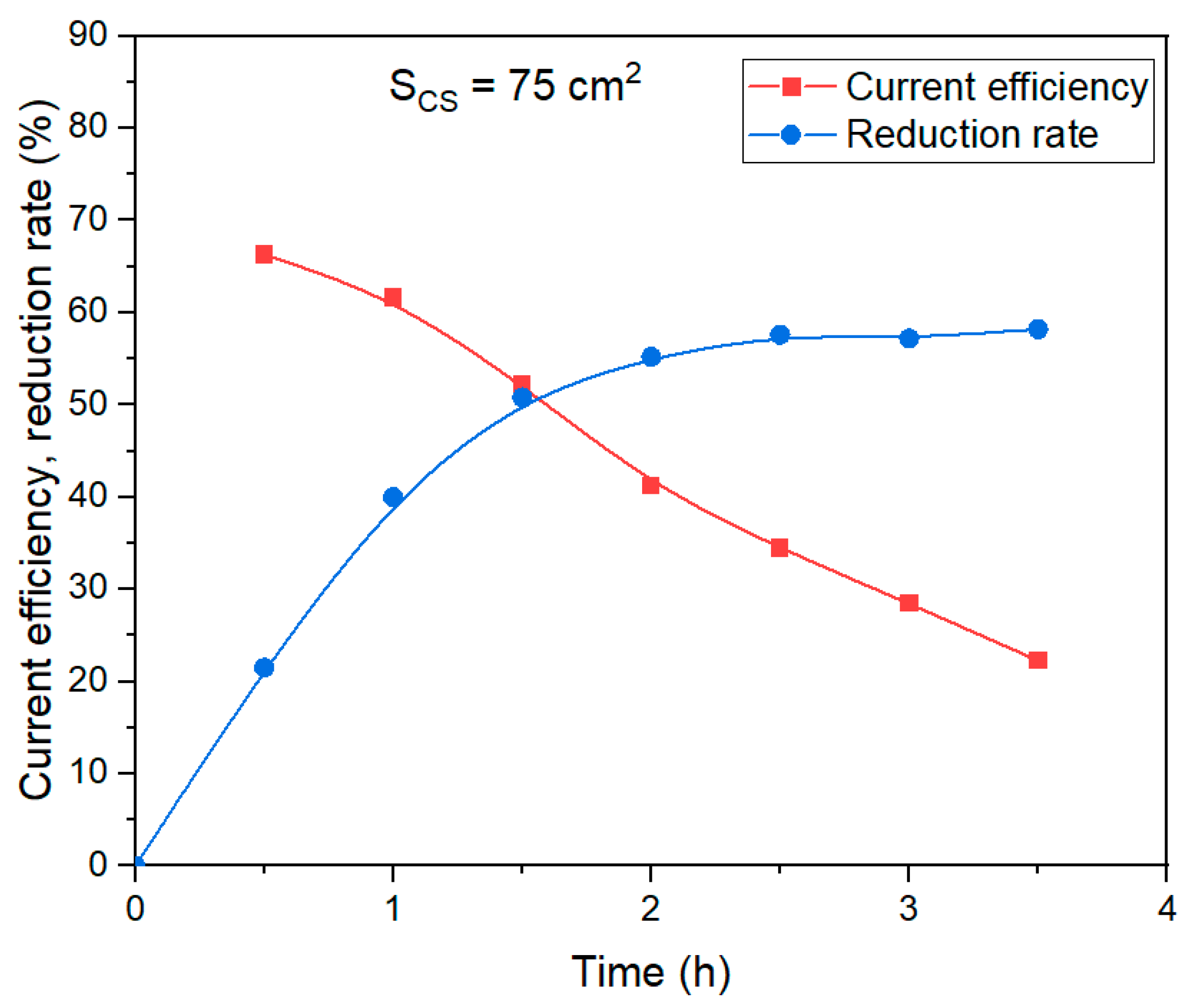

Figure 12) because the rate of the side reaction of hydrogen evolution increases. An attempt was made to conduct the experiment at a potential corresponding to the reduction of hematite into elemental iron (–1.15 V). When overvoltage is not sufficient for intensive hydrogen evolution, but the product is not magnetite. For this purpose, we experimentally selected an area of stainless steel mesh that the potential at the cathode was –1.15 V during potentiometric measurements at a current of 1.945 A. The results of the experiments with a 75 cm

2 current supply are shown in

Figure 13.

The voltammetric curve presented in

Figure 13a and obtained using a medium-sized current supply is similar to the curve in

Figure 9. However, in contrast to the electrolysis with a large area current supply at a current of 1.945 A, the potential at the cathode was –1.15 V, which favors the production of metallic iron. In fact,

Figure 13b shows that after 1 hour of electrolysis, the overvoltage at the cathode decreases. This is because metallic iron forms on the surface of the cathode.

Figure 14 shows the dependence of the current efficiency coefficient and the degree of bauxite iron minerals reduction using a medium-sized current supply (the average value of the potential at the cathode in these experiments was –1.16 V) on the duration of electrolysis.

It is obvious that at an average potential at the cathode of –1.16 V, the results obtained are intermediate between large and small area current supplies. After 30 min of electrolysis, the current efficiency coefficient amounted to 66%, and after an hour it decreased only by 5%. The current efficiency coefficient dropped more significantly than at the current supply of 40 cm2. After 3.5 h of electrolysis, the reduction rate of bauxite iron minerals reached 58%, which is only 2% lower than at larger area current supply.

Thus, the use of a bulk cathode and an alkaline solution with a concentration of 400 g L–1 Na2O allows a significant increase in the current efficiency (>70%), if the target reduction rate of bauxite iron minerals does not exceed 50%.

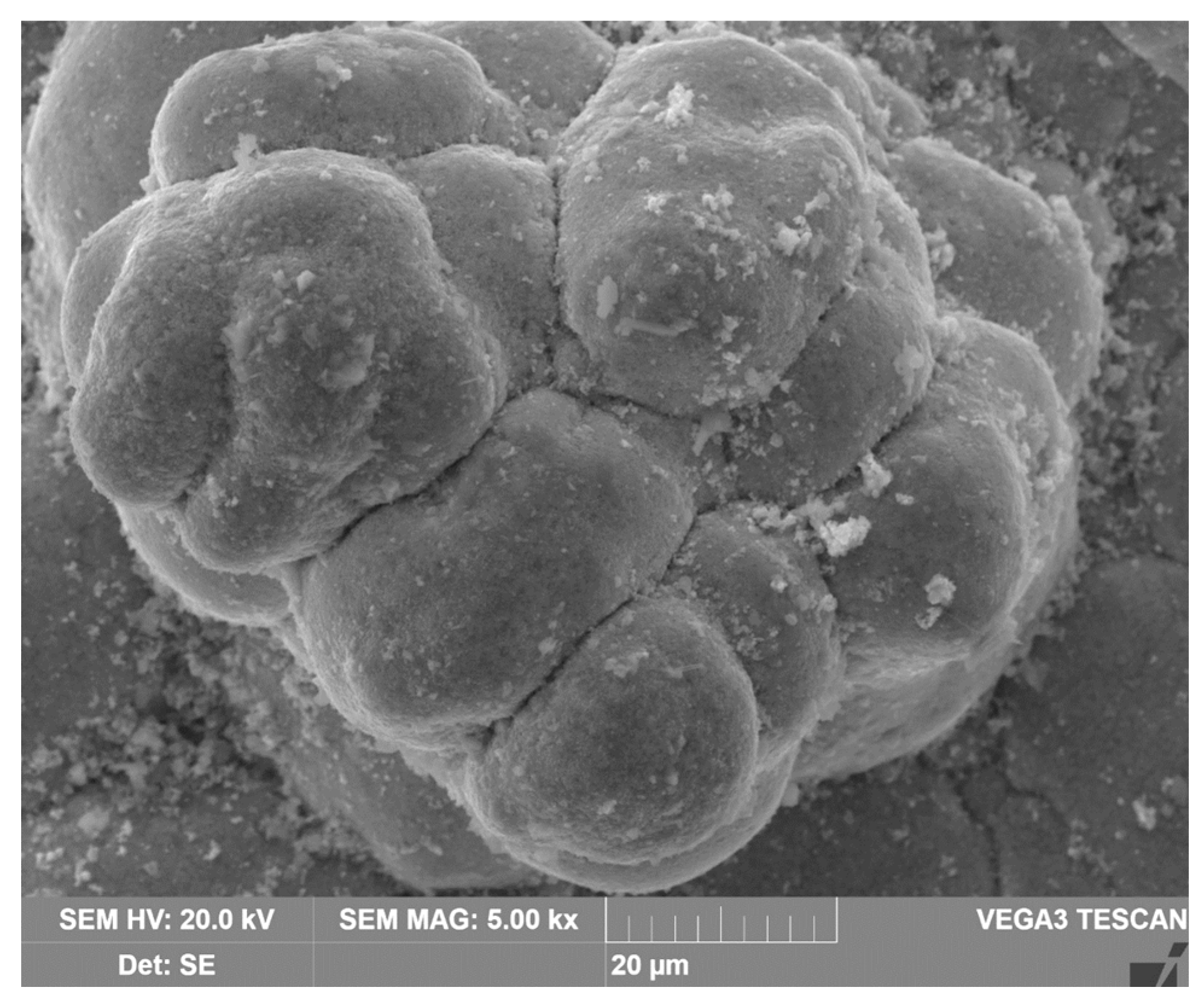

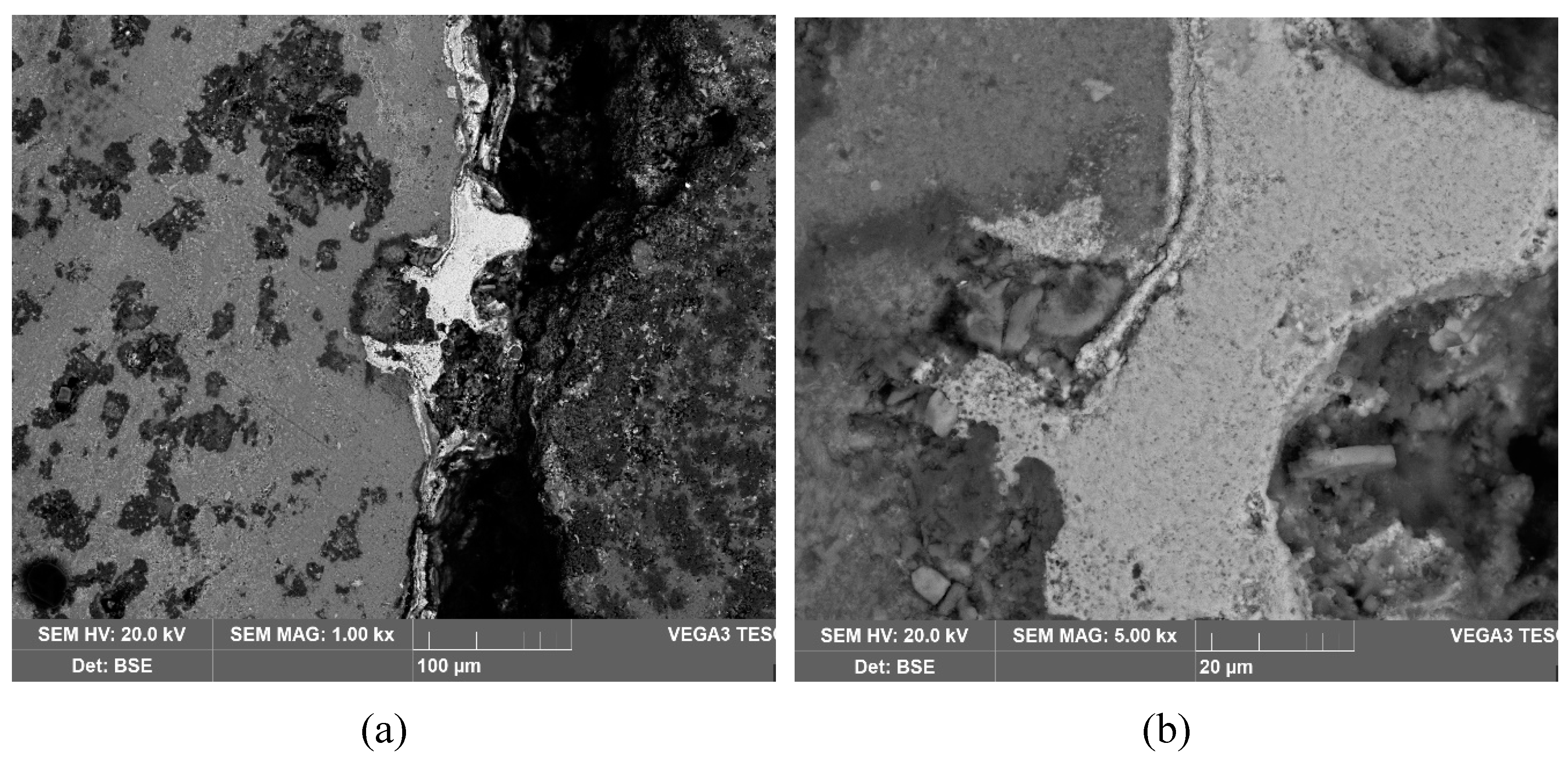

3.2. Solid products characterization

The figure 15 shows a SEM-image of the precipitate that formed on the cathodes surface during electrolysis with a cathode immersed in a suspension of bauxite in aluminate solution, at 120 °C, and a current density of 0.06 A cm

–2. The observed phenomenon indicates that, at low current densities, spherical-shaped precipitates are formed during electrolysis in the Bayer process solution. The spherical shape of the precipitate indicates a low iron content in the solution. Under these conditions, the solubility of hematite in an alkaline solution does not exceed 2x10

-3 mol L

–1 [

25].

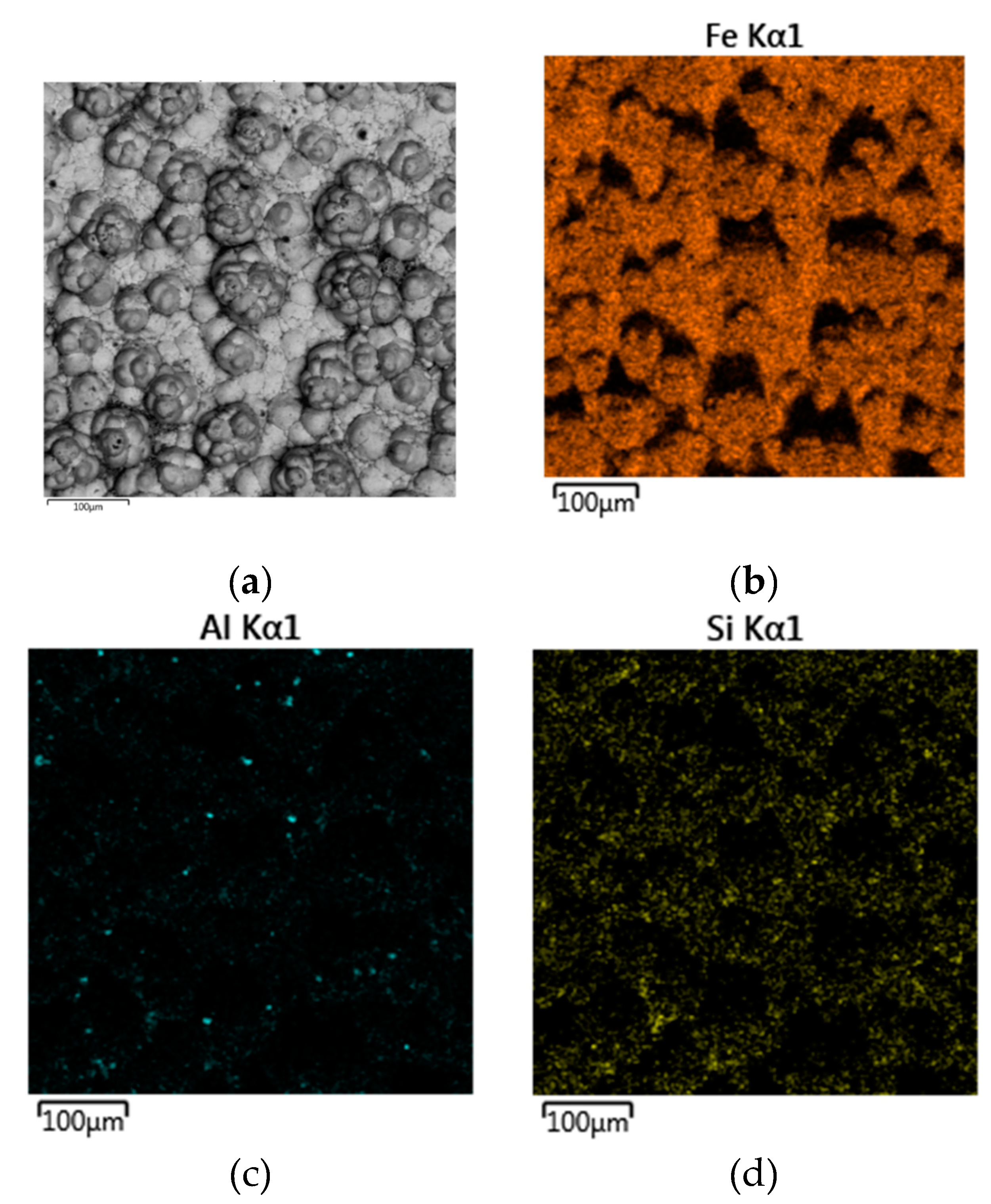

Figure 16 shows the distribution of elements on the cathode precipitates surface. It is evident that the particles present on the cathode surface predominantly comprise iron and minor impurities of aluminum and silicon, which may be attributed to the physical inclusion of the suspension during metal deposition. The XRD pattern of the precipitate shown in

Figure 17 confirms the presence of iron as the main phase.

Figure 18 shows the results of the SEM-EDS analysis of the solid residue obtained using a 110 cm

2 mesh current supply during 1.17 h of electrolysis. It can be seen that the solid residue consists of individual aluminum particles and iron-containing phases. The results of the chemical composition of this solid residue indicate that Si is associated with Al, which may indicate the formation of a desilication product. This is confirmed by the results of the chemical composition of the solid residue (

Table 3). A particle with a higher iron content can also be seen in the SEM-images.

Figure 19a shows this particle at a high magnification. Other particles with a high iron content were also found (

Figure 19b).

According to the SEM-EDS spectra, the mass percentage of iron on the surface of these particles was 75-80%, which was higher than the stoichiometric value for pure magnetite. This may indicate the presence of iron.

Figure 20d shows the XRD diffraction pattern of the BR. It is evident that this BR is mainly composed of hematite and magnetite, with a small amount of unleached boehmite and the resulting desilication product.

The results of the SEM-EDS analysis of the solid residue obtained using a 110 cm

2 mesh current supply during 1.17 h of electrolysis are shown in

Figure 18. The dendritic morphology of these particles suggests that they were most likely formed by the reduction of iron hydroxocomplexes on the surface of the current supply (Equation (4)). The results of the XRD analysis of this sample (

Figure 21b) further confirm the presence of iron, revealing small peaks of elemental iron. After electrolysis at –1.41 V, the amount of magnetite in the solid residue was lower than in experiments with high-area current. However, it increased after Bayer high-pressure leaching of the solid residue from electrolysis (

Figure 21c) This suggests that elemental iron reacted with the alkaline solution with the formation of magnetite [

15] according to Equations (15)-(17).

Table 4 shows the chemical composition of the solid residue after electrolysis with a current of 40 cm

2 for 1.17 h and the BR after two stages (electrolysis followed by leaching in Bayer solution at 250 °C for 30 min). The solid residue from electrolysis at the potential of the cathode –1.41 V has a higher concentration of alumina and a lower concentration of iron (2+), thereby confirming the incompleteness of the process of boehmite leaching and iron minerals reduction. The formation of magnetite during the interaction of elemental iron with Bayer's solution results in a significant increase in the iron (2+) content after high-pressure leaching.

Figure 22 shows SEM-EDS images of the BR after high-pressure leaching. The results of the SEM-EDS analysis of the BR show that the iron is evenly distributed on the surface of particles, and that aluminium and silicon are found in the form of individual particles associated with Na - in the form of desilication product. There are also single independent particles of titanium compounds.

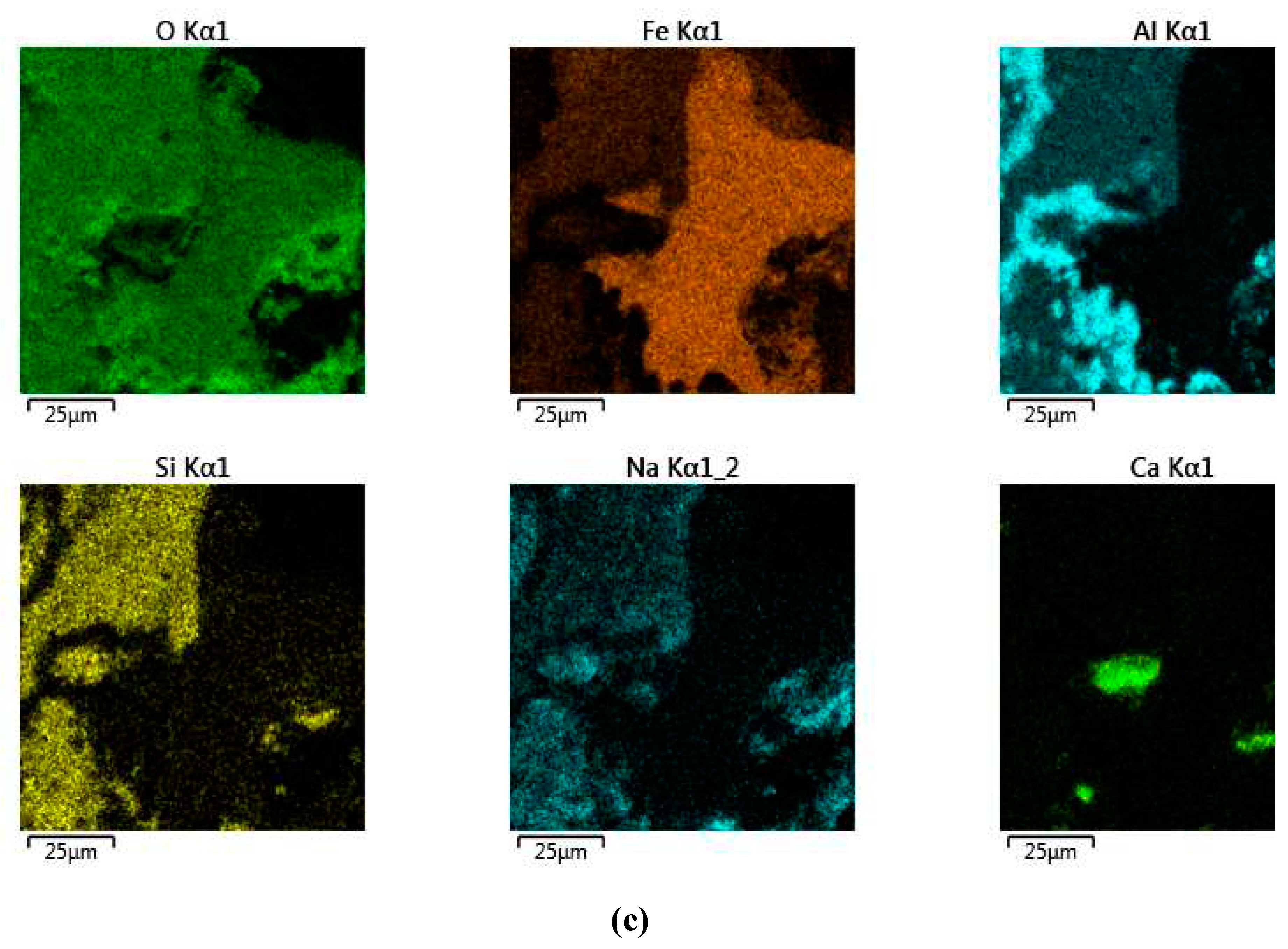

A film of magnetite on the sample surface may be responsible for the low degree of reduction (not more than 60 %) and the attenuation of the process after 1 h of electrolysis. To confirm this, a SEM-EDS analysis of the surface of the solid residue coarse particle was performed (

Figure 23).

Figures 23a and 23b show a SEM image of one of the sections of the coarse particle revealing the formation of a solid film on the surface. As can be seen from

Figure 23c, the phase with increased iron content is found on the surface of the particle at the point of contact of the initial iron-bearing phase of bauxite with the solution. This suggests that the process proceeds mainly through dissolution. The presence of a lot of oxygen in all phases shows that magnetite was being formed on the surface of the sample, not elemental iron.

Due to the dense layer of magnetite formed on the surface of the particle, it is impossible for the alkaline solution to penetrate the particle, thus creating diffusion limitations. Also, the phase, which is in contact with the magnetite inside the particle, may not have iron in its composition and be a dielectric, which slows down the process. To intensify the process, it is necessary to use fine grinding raw material or to create conditions that favor complete dissolution of the iron-free phases, such as pre-dissolution of the bauxite.

The results show that, under the conditions of the experiments presented in this article, when using bauxite instead of pure hematite for reduction, two processes predominate: 1) the reduction of dissolved iron on the cathode surface; 2) the interaction of the iron-containing phase of bauxite with iron (2+) ions to form magnetite. Because of this, magnetite and elemental iron can be formed. The predominance of one or another product depended on the conditions of the process (temperature, concentration), the potential at the cathode, the method of current supply, etc.

The possibility of obtaining different products opens up several directions for further research, depending on the task. If it is necessary to reduce all the hematite and other iron minerals in bauxite or BR to obtain a highly profitable product, a process using a suspension and a plate cathode in highly concentrated alkaline solutions should be used. The reduction of iron minerals in the bauxite immediately prior to the extraction of aluminum can be achieved by employing a bulk cathode configuration with low alkali concentrations, resulting in the preferential formation of magnetite.