Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

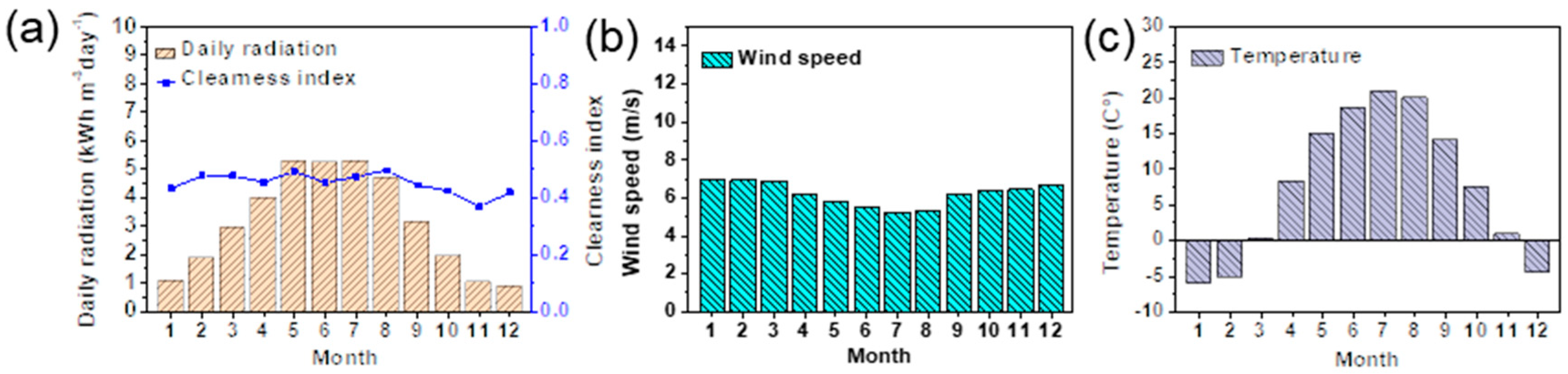

- Kyiv has considerable potent solar and wind energy for green hydrogen production.

- HOMER evaluates the techno-economic feasibility of a hybrid HydESS for renewables.

- The lowest LCOE is 0.245 $ kWh−1 from the Wind-HydESS-BESS hybrid system.

- The HydESS system consists of a 250-kW PEM fuel cell and a 250-kW electrolyzer.

- An additional benefit of HydESS is a reduction of CO2 to 4,132 tons for 25 yrs.

- The lifetime sensitivity of proton exchange membrane fuel cells is reduced, but the on-off time of 600 seconds is anticipated to be more severe.

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

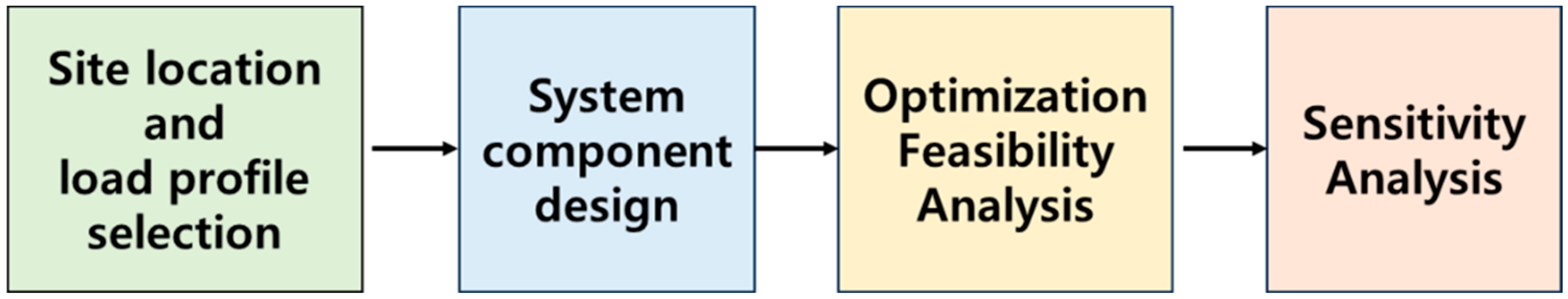

2.1. Research framework & Flow

2.2. Literature Review

| Ref |

Item | COE | NPC | PV | Wind | BESS | PEMWE | PEMFC | H2 tank | Region | AC load or Hydrogen demand |

| Objective | $ kWh−1 | $ | kW | kW | kW | kW | kW | kg | kWh day−1 kgH2 day−1 |

||

| [17] | BESS vs. HydESS comparison |

1.208 | 75,428 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Saudi Arabia | 14 kWh day−1 |

| [18] | BESS vs. HydESS comparison |

0.52 | 7,160,000 | 469 | 1500 | 396 | 350 | 100 | 500 | USA | 70 kgH2 day−1 |

| [19] | HydESS feasibility | 0.8399 | 1,006,293 | 120 | - | - | 60 | 13 | 20 | Spain | 200 kWh day−1 |

| [20] | HydESS case study |

1.901 | 910,415 | 1 | 1 | - | 150 | 1 | 100 | Oman | 12 kWh day−1 |

| [21] | PV vs. Wind comparison |

0.374 | 2,990,000 | 69 | 88 | 581 | 250 | 450 | 700 | Canada | 125 kgH2 day−1 |

| [22] | PV vs. Wind comparison |

0.366 | 5,276,069 | 900 | 700 | 1088 | 300-kW | 100 | 300 | Korea | 2187.6 kWh day−1 |

| This work |

BESS vs. HydESS comparison |

0.245 | 4,508,672 | 0 | 1,000 | 441 | 250 | 250 | 700 | Ukraine | 3,900 kWh day−1 |

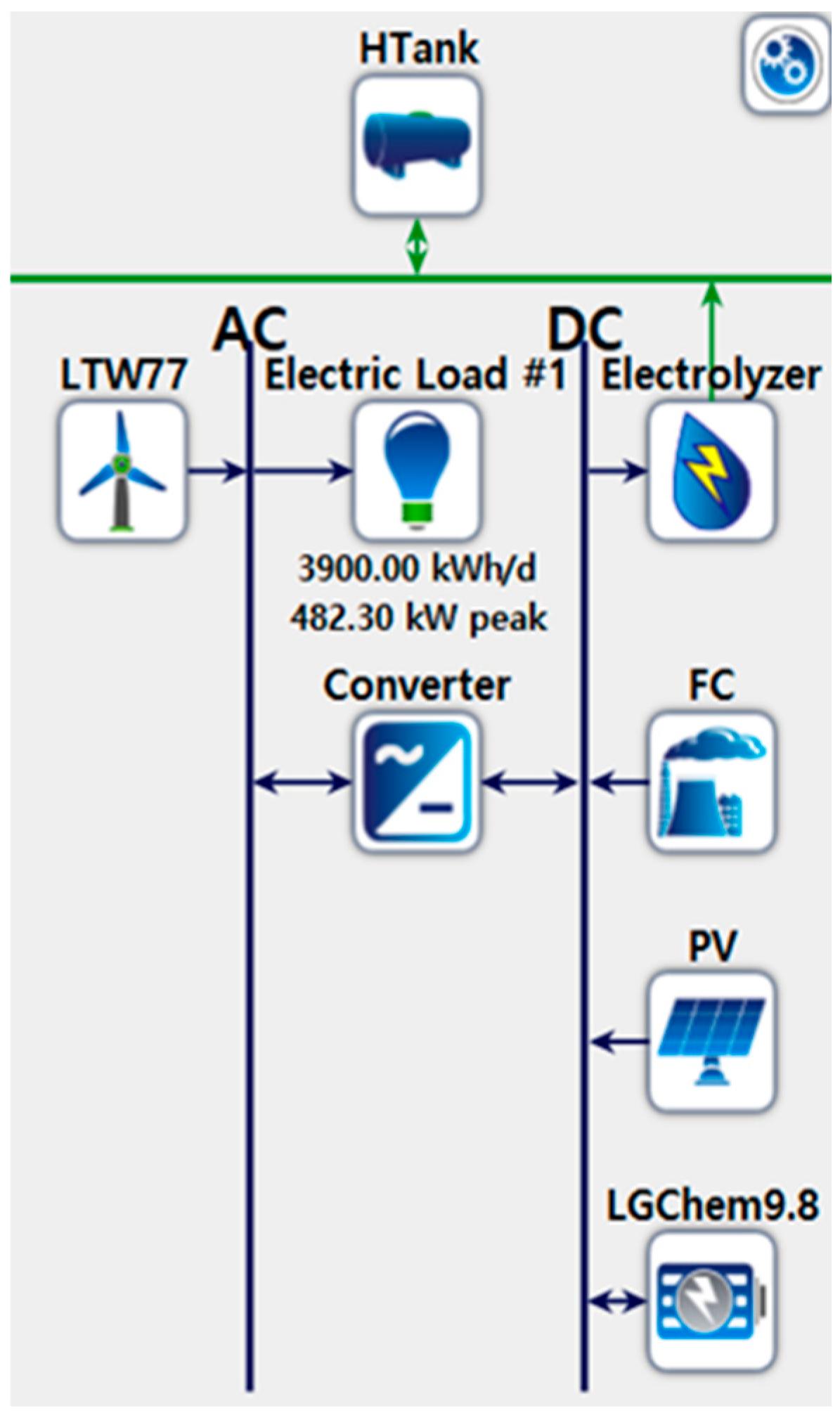

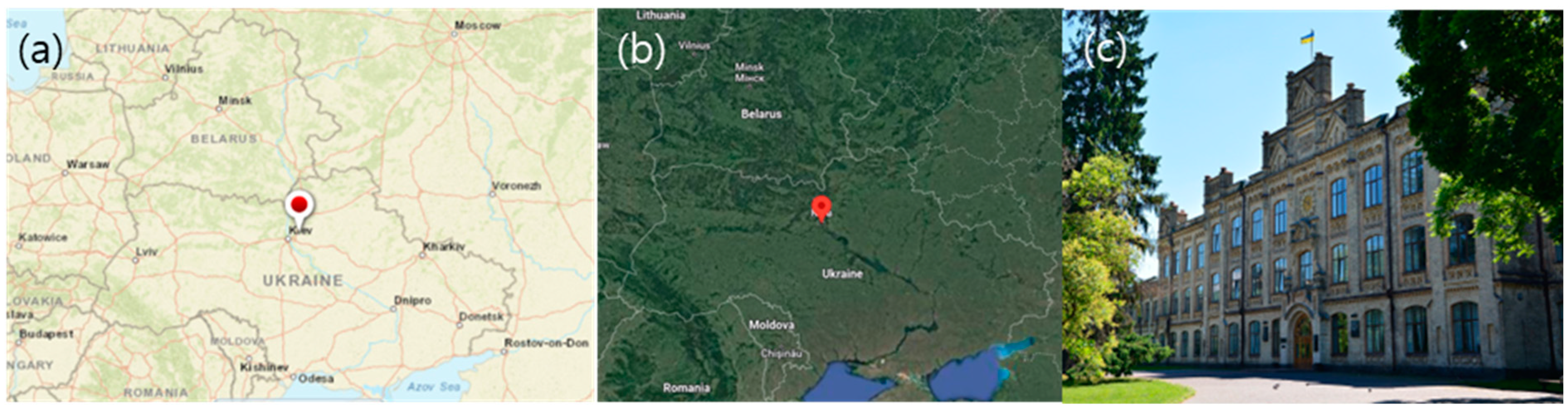

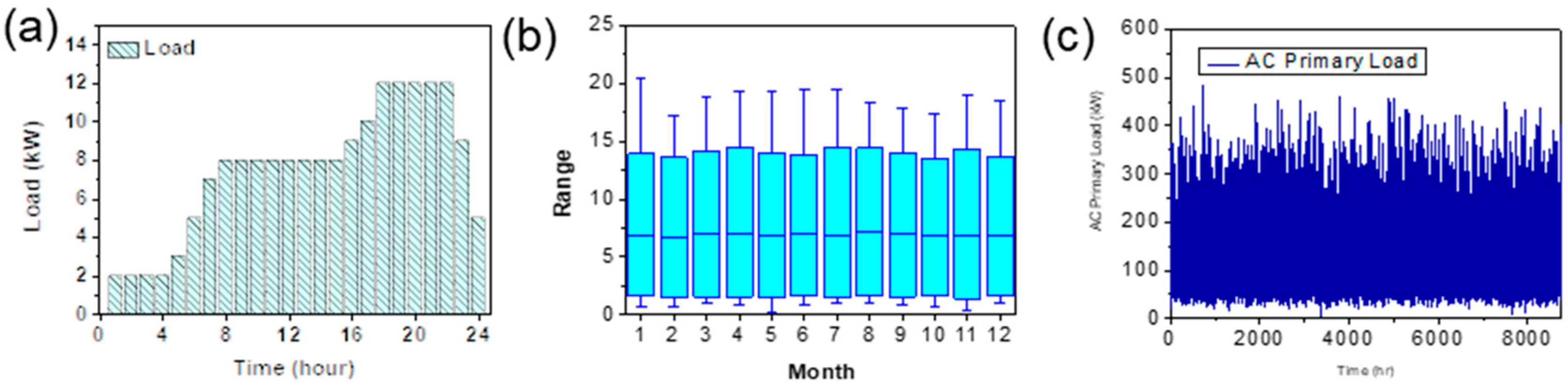

2.3. System and site outline

| System data | ||

| PV Unit | ||

| Capital expenditure | 1252 | $ kW−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 18 | $ y−1 kW−1 |

| Lifetime | 25 | years |

| Derating factor | 85 | % |

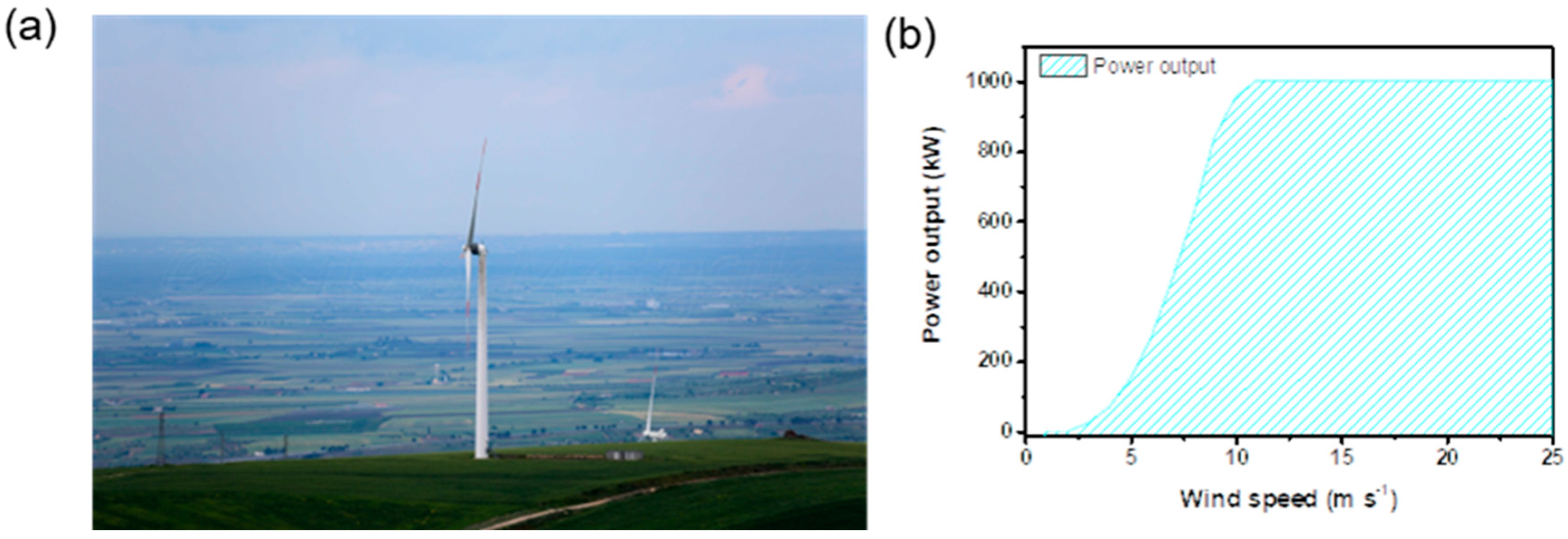

| Wind turbine system | ||

| Capital expenditure | 1500 | $ kW−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 50 | $ y−1 kW−1 |

| Lifetime | 25 | years |

| Batteries (100 kWh Li BESS) | ||

| Nominal voltage | 480 | V |

| Nominal catacity | 90.7 | kWh |

| Maximum capacity | 189 | Ah |

| Captial expenditure | 415 | $ kWh−1 |

| Replacement expenditure | 280 | $ kWh−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 25 | $ y−1 kWh−1 |

| Lifetime | 10 | years |

| Converter | ||

| Capital expenditure | 90 | $ kW−1 |

| Replacement c expenditure | 90 | $ kW−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 0 | $ y−1 |

| Lifetime | 15 | years |

| Efficiency | 95 | % |

| Electrolyzer | ||

| Capital expenditure | 1400 | $ kW−1 |

| Replacement expenditure | 650 | $ kW−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 60 | $ y−1 |

| Lifetime | 25 | years |

| Storage tank (High pressure) | ||

| Capital expenditure | 635 | $ kg−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | 3 | $ y−1 |

| Lifetime | 25 | years |

| Fuel cell | ||

| Capital expenditure | 4800 | $ kW−1 |

| Replacement expenditure | 3800 | $ kW−1 |

| Operation and maintenance expenditure | $ y−1 | |

| Lifetime | 5 | years |

2.4. Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

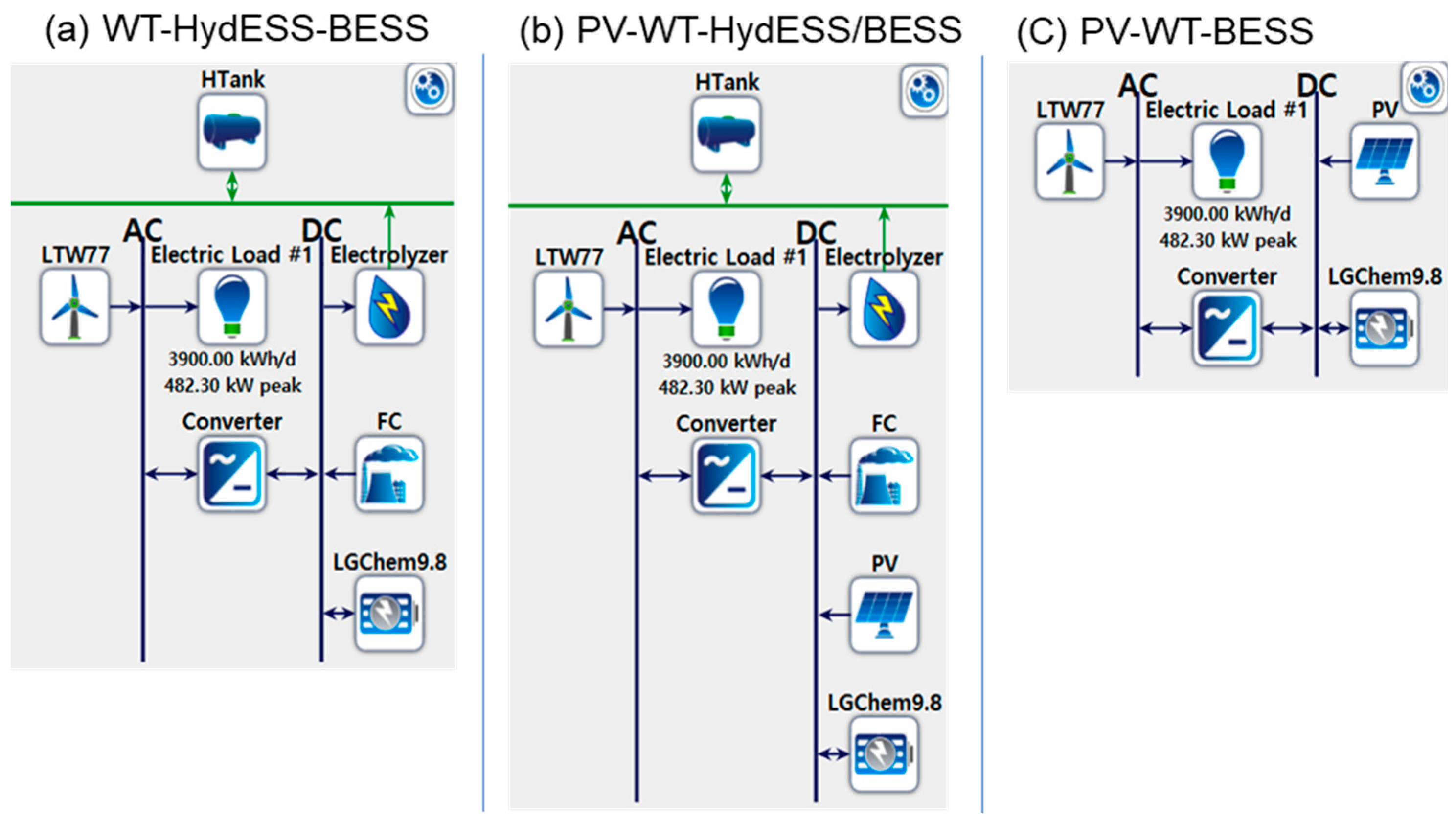

3.1. Optimized system configuration

| Case | FC type | Lifetime | Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) | Total net present cost (NPC) | PV | Wind turbine | FC | Li-ion battery | Converter | PEMWE |

| Units | - | hrs | $/kWh−1 | $ | kW | kW | kW | kWh | kW | kW |

| (a) HydESS-1 | PEMFC | 40,000 | 0.249 | 4,584704 | 0 | 1,000 | 250 | 499.8 | 474 | 250 |

| PEMFC | 50,000 | 0.245 | 4,508,672 | 0 | 1,000 | 250 | 441 | 464 | 250 | |

| SOFC | 40,000 | 0.369 | 6,794770 | 0 | 1000 | 250 | 2,274 | 632 | 250 | |

| SOFC | 50,000 | 0.289 | 5,316,831 | 0 | 1,000 | 250 | 911 | 481 | 250 | |

| (b) HydESS-2 |

PEMFC | 40,000 | 0.250 | 4,591,366 | 1 | 1000 | 250 | 509.6 | 466 | 250 |

| PEMFC | 50,000 | 0.246 | 4,526,294 | 2 | 1,000 | 250 | 450.8 | 524 | 250 | |

| SOFC | 40,000 | 0.348 | 6406074 | 140 | 1000 | 250 | 1,744 | 500 | 250 | |

| SOFC | 50,000 | 0.282 | 5,179,203 | 10 | 1,000 | 250 | 755 | 573 | 250 | |

| (c) BESS |

none | - | 0.516 | 9,483,948 | 518 | 2,000 | - | 3,959.2 | 677 | - |

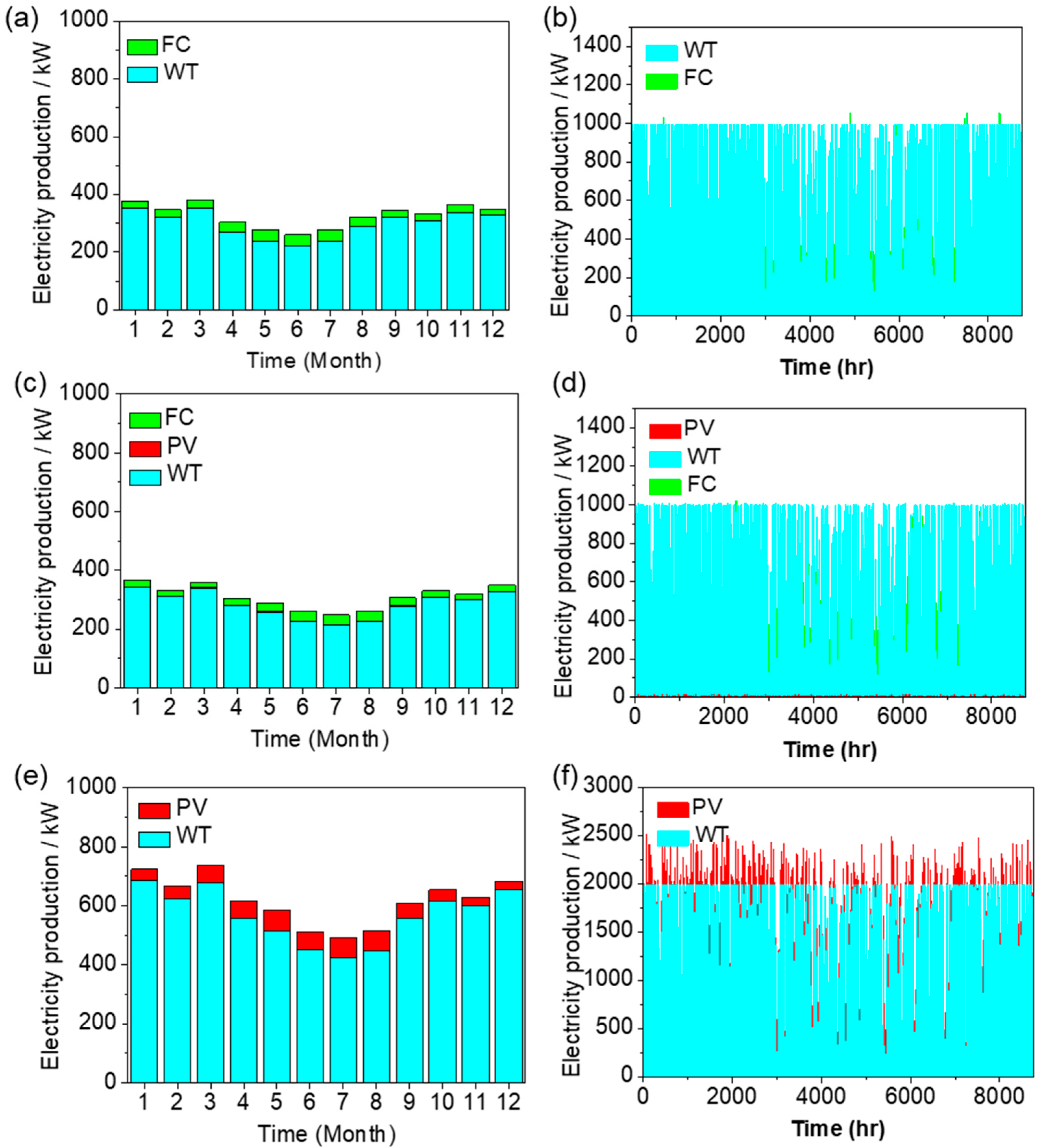

3.2. Electricity production

| Quantity | Case 1 WT-HydESS-BESS |

Case 2 PV-WT-HydESS-BESS |

Units |

| Rated capacity | 250 | 250 | kW |

| Mean input | 75.1 | 74.6 | kW |

| Total input energy | 658,185 | 653,062 | kWh yr−1 |

| Capacity Factor | 30.1 | 29.8 | % |

| Hours of operation | 3,612 | 3,657 | hr yr−1 |

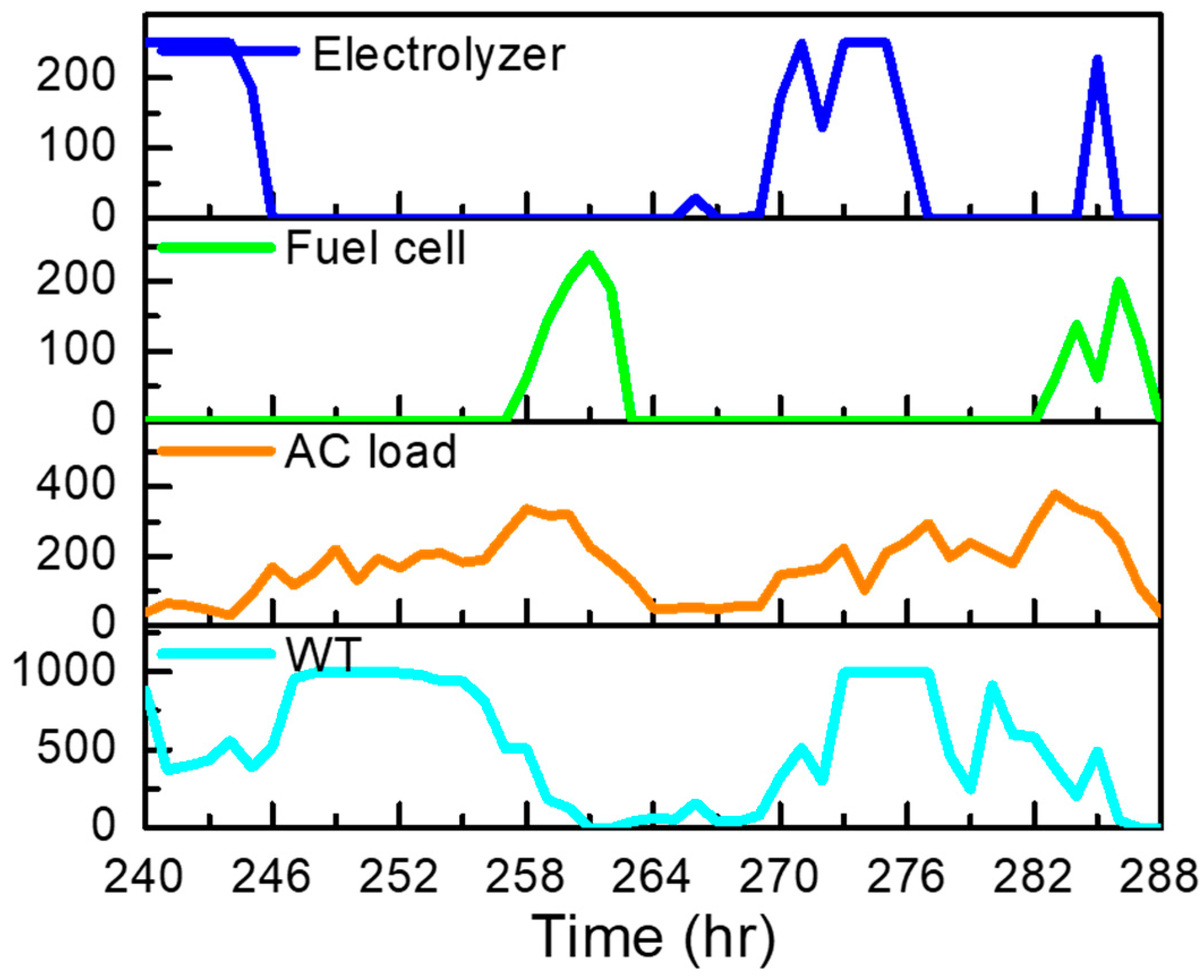

3.3. Operation strategy

3.4. CO2 Emissions

| Material | DG-BESS | HydESS-1 | Units |

| Carbon dioxide | 223,297 | 0 | kg yr−1 |

| Carbon monoxide | 1,408 | 2.61 | kg yr−1 |

| Unburned hydrocarbons | 61.4 | 0 | kg yr−1 |

| Particle matter | 8.53 | 0 | kg yr−1 |

| Sulfur dioxide | 547 | 0 | kg yr−1 |

| Nitrogen oxides | 1,322 | 0.261 | kg yr−1 |

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- 1. Jain I, Lal C, Jain A. Hydrogen storage in Mg: a most promising material. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2010;35(10):5133-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.08.088. [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa L, Mekhilef S, Ismail MS, Moghavvemi M. Energy management strategies in hybrid renewable energy systems: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016;62:821-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.040. [CrossRef]

- He T, Pachfule P, Wu H, Xu Q, Chen P. Hydrogen carriers. Nature Reviews Materials 2016;1(12):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Lambert LA, Tayah J, Lee-Schmid C, Abdalla M, Abdallah I, Ali AH, Esmail S, Ahmed W. The EU’s natural gas Cold War and diversification challenges. Energy Strategy Reviews 2022;43:100934. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000551952. [CrossRef]

- Ścigan M, Gonul G, Türk A, Frieden D, Prislan B, Gubina A. Cost-Competitive Renewable Power Generation: Potential across South East Europe. Citation: IRENA, Joanneum Research and University of Ljubljana (2017), Cost-Competitive Renewable Power Generation: Potential across South East Europe, International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi.: IRENA; 2017.

- Arent D, Sullivan P, Heimiller D, Lopez A, Eurek K, Badger J, Jorgensen HE, Kelly M, Clarke L, Luckow P. Improved offshore wind resource assessment in global climate stabilization scenarios. National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States); 2012. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.2172/1055364. [CrossRef]

- Kuzior A, Lobanova A, Kalashnikova L. Green energy in Ukraine: State, public demands, and trends. Energies 2021;14(22):7745. [CrossRef]

- Sabishchenko O, Rębilas R, Sczygiol N, Urbański M. Ukraine energy sector management using hybrid renewable energy systems. Energies 2020;13(7):1776. [CrossRef]

- in,.

- Kudria S, Ivanchenko I, Tuchynskyi B, Petrenko K, Karmazin O, Riepkin O. Resource potential for wind-hydrogen power in Ukraine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021;46(1):157-68. [CrossRef]

- Lilienthal P. HOMER® micropower optimization model. National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States); 2005.

- Arsad A, Hannan M, Al-Shetwi AQ, Mansur M, Muttaqi K, Dong Z, Blaabjerg F. Hydrogen energy storage integrated hybrid renewable energy systems: A review analysis for future research directions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022;47(39):17285-312. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem TB, Siddiqui M, Khalid M, Asif M. Distributed energy systems: A review of classification, technologies, applications, and policies: Current Policy, targets and their achievements in different countries (continued). Energy Strategy Reviews 2023;48:101096. [CrossRef]

- Singlitico A, Ústergaard J, Chatzivasileiadis S. Onshore, offshore or in-turbine electrolysis? Techno-economic overview of alternative integration designs for green hydrogen production into Offshore Wind Power Hubs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Transition 2021;1:100005. [CrossRef]

- Voronova A, Kim HJ, Jang JH, Park HY, Seo B. Effect of low voltage limit on degradation mechanism during high-frequency dynamic load in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. International Journal of Energy Research 2022:11867–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.7953. [CrossRef]

- Mottaghizadeh P, Jabbari F, Brouwer J. Integrated solid oxide fuel cell, solar PV, and battery storage system to achieve zero net energy residential nanogrid in California. Applied Energy 2022;323:119577. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharafi A, Sahin AZ, Ayar T, Yilbas BS. Techno-economic analysis and optimization of solar and wind energy systems for power generation and hydrogen production in Saudi Arabia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017;69:33-49. [CrossRef]

- Abdin Z, Mérida W. Hybrid energy systems for off-grid power supply and hydrogen production based on renewable energy: A techno-economic analysis. Energy Conversion and management 2019;196:1068-79. [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Peláez S, Colmenar-Santos A, Pérez-Molina C, Rosales A-E, Rosales-Asensio E. Techno-economic analysis of a heat and power combination system based on hybrid photovoltaic-fuel cell systems using hydrogen as an energy vector. Energy 2021;224:120110. [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo PC, Barhoumi EM, Mansir IB, Emori W, Uzoma PC. Techno-economic analysis and optimization of solar and wind energy systems for hydrogen production: a case study. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2022;44(4):9119-34. [CrossRef]

- Babaei R, Ting DS, Carriveau R. Optimization of hydrogen-producing sustainable island microgrids. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022;47(32):14375-92. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Wei QS, Oh BS. Cost analysis of off-grid renewable hybrid power generation system on Ui Island, South Korea. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022;47(27):13199-212. [CrossRef]

- Steinbach A. Low-Cost, High-Performance Catalyst Coated Membranes for PEM Water Electrolyzers NREL; 2022. DOE-3M-0008425. https://doi.org/10.2172/1863440. [CrossRef]

- in,.

- in,.

- Zhao S, Stocks A, Rasimick B, More K, Xu H. Highly active, durable dispersed iridium nanocatalysts for PEM water electrolyzers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018;165(2):F82-F89. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0981802jes. [CrossRef]

- Park S, Shviro M, Hartmann H, Mayer J, Carmo M, Stolten D. Cation-Exchange Method Enables Uniform Iridium Oxide Nanospheres for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2022;5(3):4062-71. [CrossRef]

- in,.

- Viswanathan V, Mongird K, Franks R, Baxter R. 2022 Grid Energy Storage Technology Cost and Performance Assessment. Energy 2022;2022.

- in,.

- Hoarcă IC, Bizon N, Șorlei IS, Thounthong P. Sizing design for a hybrid renewable power system using HOMER and iHOGA simulators. Energies 2023;16(4):1926. [CrossRef]

- Irena GHCR. Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 ⁰C Climate Goal. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi 2020.

- Lee B, Heo J, Choi NH, Moon C, Moon S, Lim H. Economic evaluation with uncertainty analysis using a Monte-Carlo simulation method for hydrogen production from high pressure PEM water electrolysis in Korea. International journal of hydrogen energy 2017;42(39):24612-19. [CrossRef]

- Iora P, Taher M, Chiesa P, Brandon N. A novel system for the production of pure hydrogen from natural gas based on solid oxide fuel cell–solid oxide electrolyzer. International journal of hydrogen energy 2010;35(22):12680-87. [CrossRef]

- Yu W, Xie H. A review on nanofluids: preparation, stability mechanisms, and applications. Journal of nanomaterials 2012;2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/435873. [CrossRef]

- Maestre V, Ortiz A, Ortiz I. Challenges and prospects of renewable hydrogen-based strategies for full decarbonization of stationary power applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021;152:111628. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Jing R, Zhang Z, Feasibility of solid oxide fuel cell stationary applications in China’s building sector and relevant progress, in: Design and Operation of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 359-93. [CrossRef]

- Parks G, Boyd R, Cornish J, Remick R. Hydrogen station compression, storage, and dispensing technical status and costs: Systems integration. National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States); 2014. [CrossRef]

- IEEE, Analysis of the influence of SOFC degradation on system State and performance. IEEE; 2021.

- Chou Y-S, Stevenson JW, Choi J-P. Long-term evaluation of solid oxide fuel cell candidate materials in a 3-cell generic short stack fixture, Part II: sealing glass stability, microstructure and interfacial reactions. Journal of Power Sources 2014;250:166-73. [CrossRef]

- Yokokawa H. Report of five-year NEDO project on durability/reliability of SOFC stacks. ECS Transactions 2013;57(1):299. [CrossRef]

- Turton R, Bailie RC, Whiting WB, Shaeiwitz JA. Analysis, synthesis and design of chemical processes. Pearson Education; 2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.330711124. [CrossRef]

- Short W, Packey DJ, Holt T. A manual for the economic evaluation of energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies. National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States); 1995. https://doi.org/10.2172/35391. [CrossRef]

- Moon HE, Ha YH, Kim KN. Comparative Economic Analysis of Solar PV and Reused EV Batteries in the Residential Sector of Three Emerging Countries—The Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Energies 2022;16(1):311. [CrossRef]

- Leland Blank P, Anthony Tarquin P. Engineering economy. 7 ed.: Oxford, New York; 2014.

- Mayer T, Semmel M, Morales MaG, Schmidt KM, Bauer A, Wind J. Techno-economic evaluation of hydrogen refueling stations with liquid or gaseous stored hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019;44(47):25809-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.051. [CrossRef]

- Kim J-H, Kim G-E, Yoo S-H. A valuation of the restoration of Hwangnyongsa temple in South Korea. Sustainability 2018;10(2):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020369. [CrossRef]

- in,.

- Sebastian R. A review of fire mitigation methods for li-ion battery energy storage system. Process Safety Progress 2022;41(3):426-29. [CrossRef]

- in,.

- Bellotti D, Rivarolo M, Magistri L. Economic feasibility of methanol synthesis as a method for CO2 reduction and energy storage. Energy Procedia 2019;158:4721-28. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).