1. Introduction

Unlike heart- and brain-related diseases, which carry a higher risk of death, bone, muscle- and nerve- related diseases have received relatively little attention in the past. However, with the improvement of living standards, disease-causing and disabling diseases have gradually received attention. In addition, diverse musculoskeletal diseases cause to heavy medical burden in every country and the burden seriously exceeds the service capacity [

1,

2]. Young children and adolescents are both at risk of musculoskeletal diseases [

3]. In China, muscle nerve diseases such as chronic non-specific low back pain, due to their complexity and lacking of correct diagnostic methods, also bring a huge burden to the medical system [

4].

A survey report of 354 diseases in 195 countries, including China from 1990 to 2017, pointed out [

5] that skeletal neuromuscular diseases accounted for a relatively large proportion and showed an increasing trend. A summary report on the impact of skeletal muscle disorders in the United States [

6] states that skeletal and muscle disorders are systemic and very common, with one in two people being diagnosed with musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, musculoskeletal diseases affect human normal life and economic development [

7,

8].

When musculoskeletal disorders that can be prevented or improved are not addressed in a timely manner, opportunities to intervene earlier and more effectively in the disease are missed, and the problem is made worse by the lack of methods for effective diagnosis. Therefore, a clinical detection method is urgently needed to improve the accuracy of diagnosis. At present, there are a variety of diagnostic methods in clinical practice, such as electromyography (EMG) [

9,

10], surface electromyography [

11], needle electromyography [

12,

13], quantitative electromyography [

9], ultrasound [

14], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

15], etc. But they have their own advantages and disadvantages. For EMG, the subcutaneous tissue is similar to low-pass filtering and the human body conducts electricity, which will affect the transmission of electrical signals and reduce the accuracy of signals [

10]. Needle EMG test signals are accurate but invasive and the location of the needle depends on the doctor’s clinical experience [

13]. Therefore, a method is needed to combine with other diagnostic methods to improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis and solve some problems in the diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases. Electric field and magnetic field are homologous. Muscle action potential is accompanied by electrical activity, and at the same time, it will radiate in space in the form of weak magnetic field, so disease diagnosis by detecting magnetic field is completely non-invasive.

In 1972, David and Edward used a Superconducting QUantum Interference Device (SQUID) to measure the muscle magnetic signal for the first time in a magnetic shielding room and defined it as a magnetomyogram (MMG) [

16]. Related instruments for the detection of magnetic signals in the heart and brain have gradually matured and entered the clinic [

17,

18,

19]. However, due to the difficulty of muscle nerve signal detection, the clinical application of MMG for disease diagnosis has been slow to develop. The clinical diagnostic technology and application of MMG in China are still blank. SQUID has been used to conduct preliminary testing and analysis of muscle signals at the laboratory for the first time in China[

20], and more relevant experiments are currently being carried out.

Some international research teams have pointed out that neuromuscular magnetic field has potential advantages in disease diagnosis, health detection, rehabilitation and robot control [

21,

22]. Compared with EMG, MMG, with a higher signal-to-noise ratio, non-invasive property, higher signal accuracy, and being insensitive to surrounding muscle tissues, can simultaneously measure multiple dimensions for source localization [

23]. Magnetic detection of spinal nerves has certain advantages compared with other clinical detection methods [

24]. In addition, MMG has potential advantages in providing additional details about the mechanism of skeletal muscle contraction [

25]. Therefore, magnetic detection of nerve and muscle is expected to become a new auxiliary detection technique, which is of great significance in the clinical diagnosis of diseases and the study of kinematic mechanism. The advantages and disadvantages of EMG, MRI and MMG are shown in

Table 1.

2. System Related Technology

Magnetoneurography (MNG), MMG, magnetocardiogram (MCG) and magnetoencephalogram (MEG), relative to the Earth’s magnetic field, are very weak magnetic field signals. To detect such a weak magnetic signal requires highly sensitive magnetic field sensors. SQUID are sensors that meet the detection requirements in sensitivity, bandwidth and time response. Optical pumped atomic magnetometers (OPM) are limited by their bandwidth and cannot meet all neuromuscular magnetic field signal tests. Other sensors, such as fluxgate and reluctance sensors, cannot meet the detection requirements. The sensors include their detection sensitivity and working bandwidth are shown in

Figure 1 [

26]. Moreover, the signal characteristics of nerve and muscle magnetic fields are shown in

Table 2 [

27]. The amplitude of the signal is not the same because of the difference of the detection site. As can be seen from

Figure 1, SQUID is currently the most suitable sensor for nerve and muscle detection.

2.1. Sensor related technology

SQUID [

28] combines the two physical phenomena of magnetic flux ionization and Josephson effect, which is the embodiment of quantum behavior at the macro level, and is also the magnetic field sensor with the highest sensitivity theoretically so far. In order to improve the performance of SQUID, different research teams at home and abroad have focused on the quality of the Josephson junction that makes up SQUID. The critical current density of Josephson junction is further increased and the junction size is further reduced.

Table 3 shows the research status of Josephson junction by different teams in recent years. By optimizing the performance of a single junction, researchers can use it for many applications, such as NanoSQUID [

33], SFQ [

34], TES [

35], etc. In the actual biomagnetic detection, magnetometer, gradiometer and current sensors are the core detection elements.

Table 4 shows the research status of different SQUID sensitive elements.

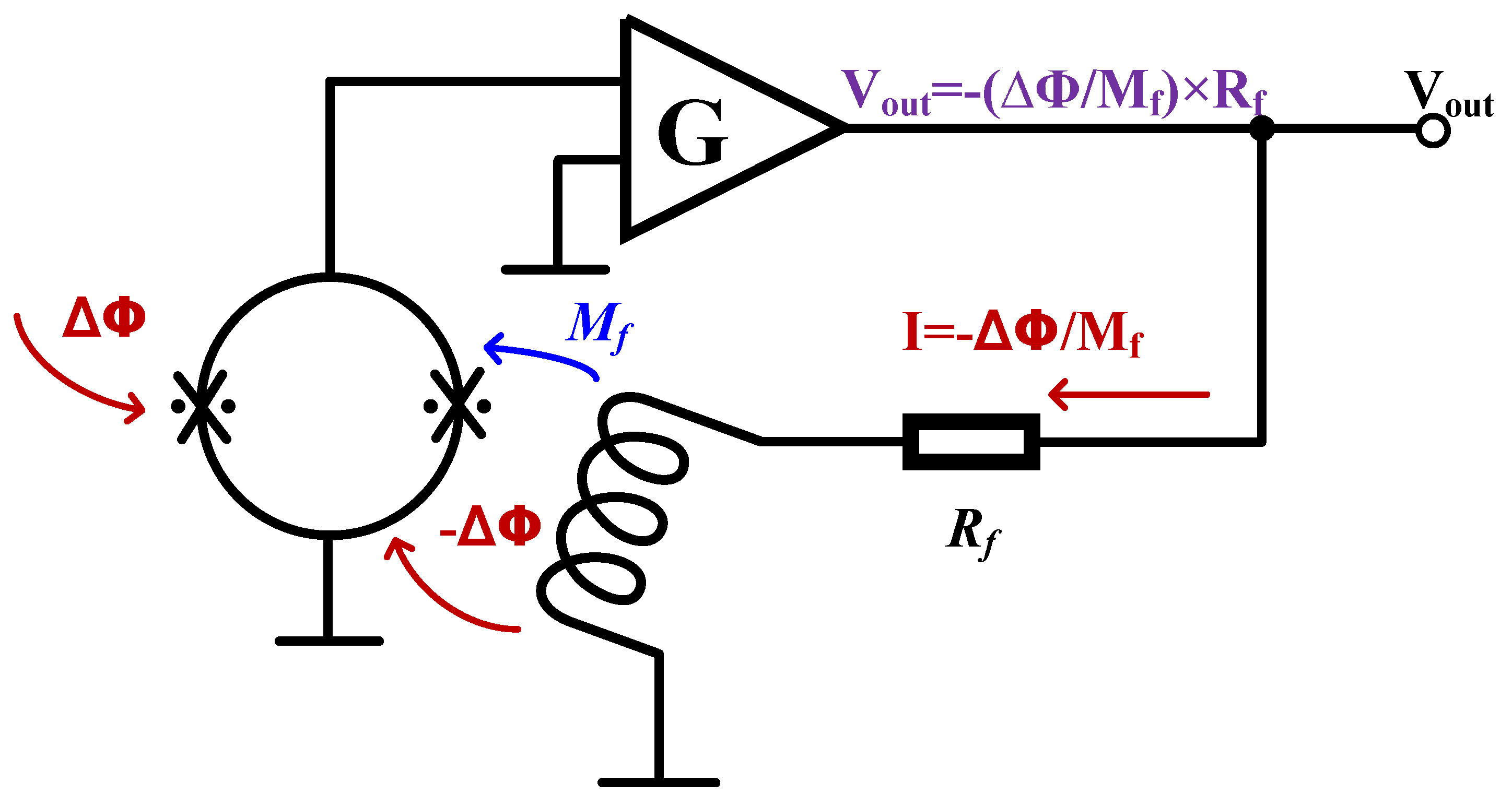

The output of SQUID is modulated by external magnetic flux in a periodic way, but the output is not linear with the detected magnetic field and cannot be directly used for magnetic field measurement. A specific readout circuit is needed to improve the dynamic range of the sensor’s magnetic flux, so that the output and magnetic flux present a linear relationship. The key structure of this circuit is the flux-locked loop (FLL) [

44,

45]. The basic principle is shown in

Figure 2. It uses a negative feedback circuit to generate a magnetic flux equal to and opposite to the external change on the feedback coil to make the sensor work in a fixed state, called the working point, and then achieve linear readout. Since the appearance of FLL, researchers have invented a variety of different readout circuits, but they are all based on FLL.

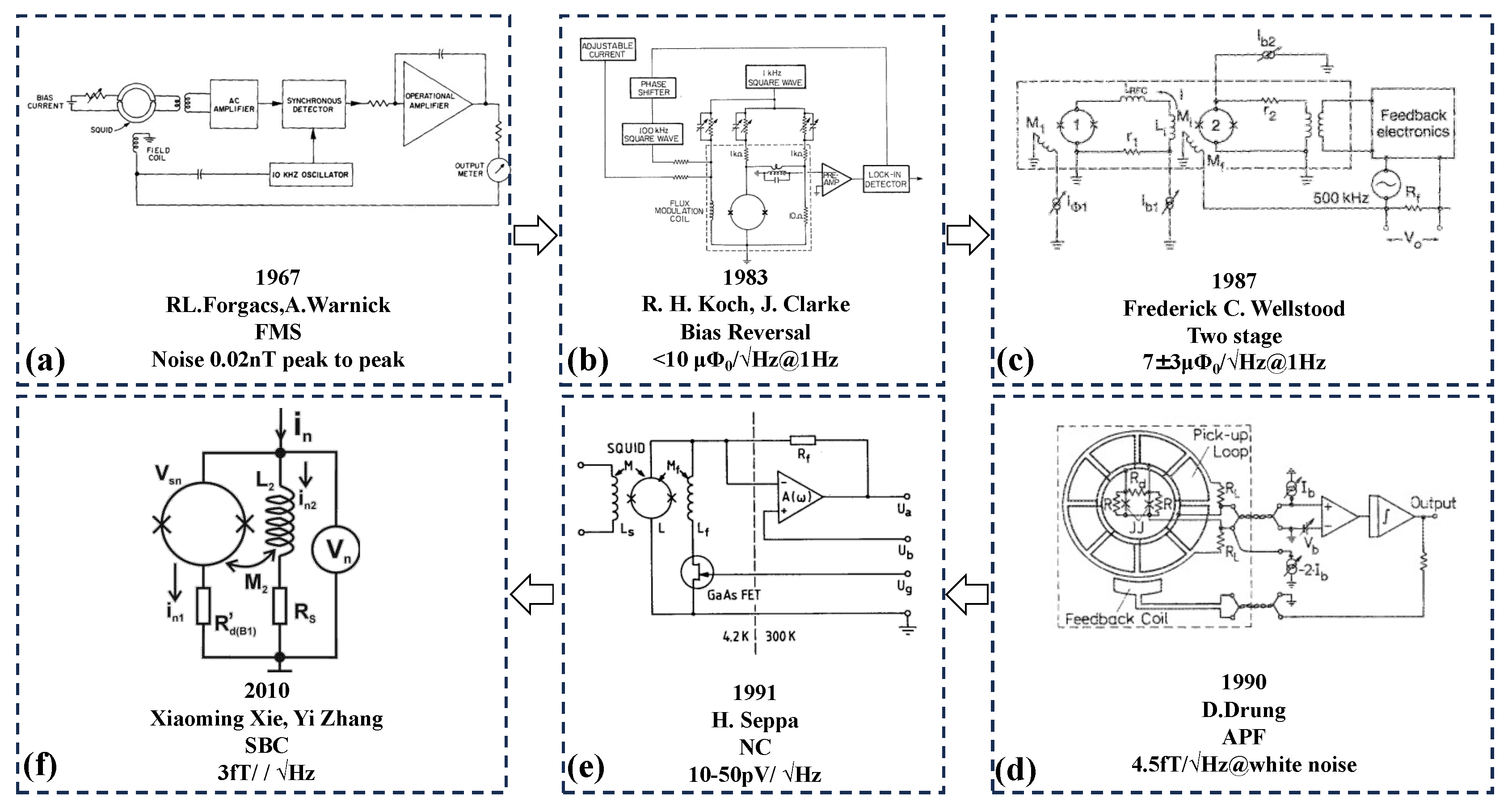

Figure 3 shows the development history of SQUID readout, and their starting point is to achieve a higher signal-to-noise ratio and more stable signal readout.

Table 5 shows the performance of the readout circuits used by different research teams, which are used in different application and therefore different parameters are focused on. However, to read out weak signals, it is of importance for the matching between the sensors and its readout circuit, and a better test environment and a stable working platform are also in need, so that the advantages of SQUID can be played and the development of the sensor in the application can be promoted.

2.2. Environmental assessment and noise suppression methods

Compared to the Earth’s magnetic field of 30-50

T, the intensity of the space magnetic field generated by bioelectrical activities such as neuromuscles is extremely small. Therefore, before the actual signal test, it is necessary to evaluate the environment,select different noise suppression means and achieve the suppression of environmental magnetic field. Among them, sensors with low sensitivity such as fluxgate [

57] can be used to test magnetic field fluctuations in time domain and gradient field fluctuations, and the frequency domain characteristics of environmental field can be tested by SQUID magnetometer with low sensitivity. If the sensor is in a shielded room, it is also necessary to evaluate the shielding effect of the shielded room.

After evaluating the signal, it is necessary to select different noise shielding and signal detection schemes according to the environmental characteristics and the amplitude and frequency domain characteristics of the detected signal. Noise shielding is mainly divided into active shielding and passive shielding [

57]. Passive shielding is the use of high permeability materials such as permalloy to build a shielding room, shielding cylinder, etc., which can play a certain shielding role in the environment of remanence and gradient field. Depending on the number of layers, the shielding effect is also different.

Table 6 shows passive shielding schemes developed by different research teams.

Although passive shielding is costly and requires large space, open magnetic shielding rooms may become a possibility for future development in the medical field. At present, due to the high cost of passive shielding, the development of active shielding has become the mainstream. The active shielding mainly captures the magnetic field signal through the magnetic field sensor, and passes the signal into the signal source, so that it generates a certain current and passes into the Helmholtz coil to generate a magnetic field equal to the ambient magnetic field and in the opposite direction, and then plays the purpose of suppressing noise. However, limited by the real-time performance of the feedback circuit and the accuracy and stability of noise compensation, the compensation effect is not ideal, so most teams combine active and passive noise suppression.

Table 7 shows the different environmental noise suppression schemes adopted by different teams.

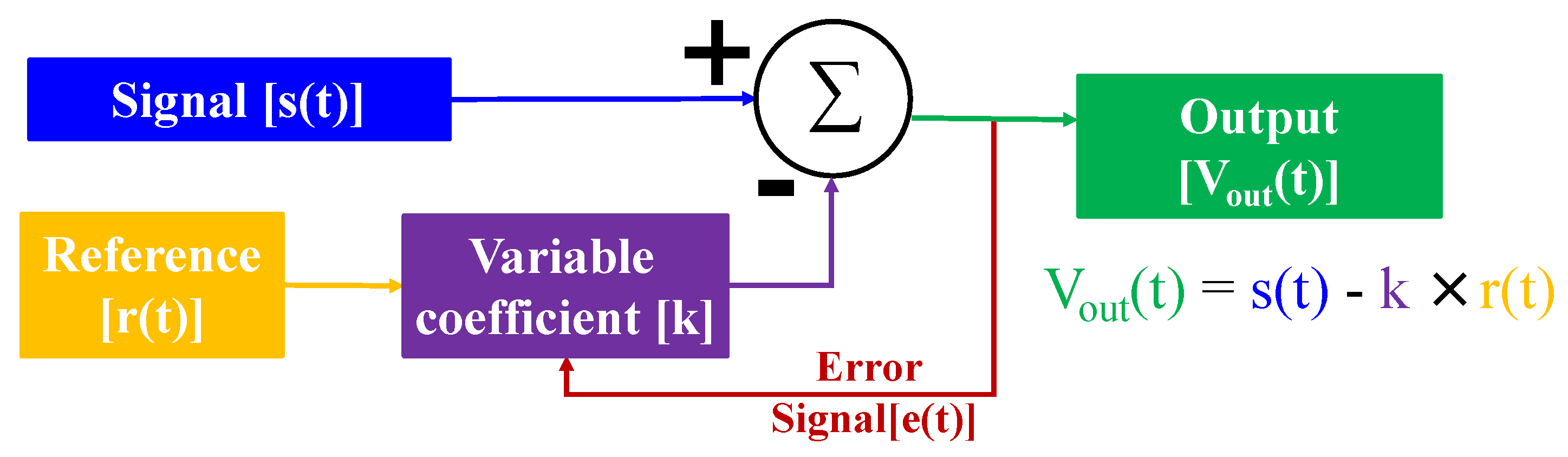

Due to the temporal and spatial correlation of magnetic fields, spatial gradient difference [

68] is also widely used to reduce the magnetic field noise in addition to shielding room and Helmholtz- coil. A gradiometer in a broad sense is called a synthetic gradiometer and consists of a signal channel and a reference channel. Any magnetic field sensor can be used as signal channel or reference channel.Different research schemes are shown in

Table 8. In addition, due to the complex and changeable environmental magnetic field, it is far from enough to only use the hardware gradiometer. An adaptive processing algorithm is also needed [

69]. Then the electronic circuit or software algorithm is used for the signal channel and the reference channel to find the time-changing compensation coefficient. Besides, an error function is needed to feedback the results and to guide the optimization of filtering effect. The schematic diagram of adaptive filtering is shown in the

Figure 4. No matter what kind of program it is for noise suppression of the environment, it is necessary to combine the characteristics of the environment and the signal to make a comprehensive selection in order to obtain a better effect.

2.3. Future development trend

For the detection of neuromuscular magnetic field, a high-sensitivity sensor and a low-noise environment are not enough. Human peripheral nerves [

73] consist mainly of 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. The body has about 639 muscles, which are made up of about 6 billion muscle fibers. Therefore, it is necessary to further improve the spatial resolution at the system level. For multi-channel systems, currently separate structures are used mainly [

74,

75]. The channels are separated from each other. Since SQUID is an inductively coupled magnetic flux, crosstalk between channels will occur if the distance between channels is too close [

76]. The suppression of crosstalk will be the focus of the subsequent system. In addition, for neuromuscular detection, portable miniaturized array sensors will become a trend.

3. Application of neuromuscular magnetism

Some research groups have made corresponding applications in neuromuscular magnetic detection based on SQUID multi-channel detection system.

Table 9 shows the relevant applications made by different teams in recent years. But they have not really gone clinical, lacking in-depth research for a certain disease; that is, the cooperation of doctors is needed. For example, acquired inflammatory myopathy has a high incidence and a long age span, and its main clinical manifestations are subacute or chronic progressive myasthenia and muscular atrophy, which is one of the most important diseases affecting the quality of life at home and abroad [

77]. However, the selection of specific detection sites and patients still needs the cooperation of doctors. In addition, it is difficult to locate the site in clinical myogenic or neurogenic disease [

78]. Comprehensive analysis should be carried out based on the characteristics of the cases. And there is an urgent need for more advanced means to solve such problems. MMG has great potential in disease diagnosis, health detection, human-machine interface and rehabilitation [

79].

MMG has its unique advantages in disease diagnosis. A team from Shigenori Kawabata in Japan used nerve or muscle magnetic field to examine multiple parts of the human body, demonstrating the advantages of magnetic field detection in disease diagnosis. In 2017, Yoshiaki Adachi introduced the composition of the MSG system and summarized its advantages in multiple bio-magnetic field detection [

84]. In 2019, his team used MNG to achieve non-invasive visualization of posterior lumbar nerve root and cauda equina nerve activity [

85]. The study data can help establish diagnostic criteria for radiculopathy. In the same year, they used MSG to demonstrate the activity of the brachial plexus and were able to distinguish the conduction pathways following stimulation of the median and ulnar nerves, and further visualized the currents within the axons [

86]. In 2020, they used the MNG system to detect the flow of activity after ulnar nerve stimulation and proved that ulnar nerve stimulation was more effective than median nerve stimulation [

87]. Besides, in 2019, the Adachi team successfully observed the response of palmar carpal tunnel area and wrist to stimulation [

88], and in the progress, artifact removal and source analysis was put on, and the results showed that MNG was helpful for the diagnosis of various peripheral neuropathy and carpal tunnel syndrome. In 2022, they studied cubital tunnel syndrome by functional imaging of the ulnar nerve of the elbow to rule out false negatives [

89].

Compared with MRI, MMG or MSG is functional imaging, so it can test the data for a long time and carry out the functional evolution of the test site, and then infer the possibility of disease at the test site in the future, so as to play the purpose of health monitoring. At present, the application of neuromuscular magnetogram in health monitoring is mainly reflected in the muscle detection of pregnant mothers before and after delivery. In 2004, Curtis L. Lowery’s team used a 151 channel system to detect muscle activity during delivery and successfully predicted the delivery of multiple patients [

90]. In 2006, based on previous studies, his team proposed four parameters that could quantify the characteristics of uterine MMG signals and help us better understand the labor process [

91]. In 2009, they conducted long-term MMG detection on pregnant mothers, and the detection results proved that MMG has the potential to predict term and preterm birth [

92].

Since MMG or MNG can be used for health detection and disease diagnosis, it can be used as a guide for disease rehabilitation. In 1999, Bruno Marcel Mackert used SQUID system to monitor signals of injured muscles for a long time in vitro, and the results showed that the neuromagnetic detection, quantification and monitoring of in vivo quasi-direct current injury is technically feasible. It also pointed out that the SQUID system can play a role in diagnosing diseases by detecting current changes caused by different depolarization modes in cerebral ischemia cases [

93]. Human skeletal muscle is also associated with the occurrence of electrical activities, so MMG is expected to be an auxiliary signal detection means in skeletal muscle physiology research [

94]. In 2019, Diana Escalona-Vargas’ team used a multi-channel SQUID array system to characterize the signaling characteristics of the anal levator muscle in pregnant women, demonstrating that MMG provides a novel and innovative tool for studying the female pelvic floor and assessing anal levator function, injury, and rehabilitation [

95].

4. Neuromuscular modeling

The signal detection sites carried out by different teams in the worldwide are not the same. Different individuals, and the different nerves or muscles of the same person are also ever-changing, so there are certain problems in the signal interpretation of neuromuscular magnetism. Therefore, building a model based on bone muscle or nerve is a prerequisite for any accurate interpretation of the signal. Different groups have modeled different parts over time, all based on Maxwell’s Equations. The magnetic field generated by a single skeletal muscle fiber was first recorded by Van Egeraat et al in 1990 [

96] and details of other cellular properties, such as membrane capacitance and intracellular conductivity, were provided using the core conduction model proposed by John P. B et al in 1985 [

97]. It is a model based on a single axon. The model is studied from two perspectives of axial current and radial current inside a single axon, and finally the relationship between the propagating current and the transmembrane potential is obtained.

From Bio-Savart’s law we know that the magnetic field is inversely proportional to the distance of the source and proportional to the amplitude of the source. From the core conductor model, it can be deduced that the magnitude of the current is equal to the axial derivative of the transmembrane potential divided by the internal resistance per unit length of the axon. Thus, the magnetic field near the nerve is proportional to the derivative of the transmembrane potential. However, when we use sensor detection, the detector is far away from the nerve, so this proportional relationship is no longer true in the actual detection, and the relationship between the magnetic field and the transmembrane potential becomes more complex. In 1985, Woosley and Roth proposed the volume conductor model [

98], which took the continuity of the transmembrane potential and the normal component of current density as the boundary condition. They also proposed the expression of potential energy in different media, applied the Fourier transform to define the filter function, and obtained the calculation formula of current density. Magnetic fields are calculated from the perspective of Bio-Savart’s law and Ampere’s theorem. Although they provide different visual images of the sources and processes that produce magnetic fields, Bio-Savart’s law and Ampere’s theorem produce the same results for all physically measurable quantities. At the same time, the paper also gave some experimental verification, giving different parameters to observe the difference of potential and magnetic field, etc., to study the influence of parameters on the model calculation. Meanwhile, in the same year, Roth and Wikswo made a detection device [

99] using ferrite core, epoxy resin and wire to detect the magnetic field and potential generated by the lobster single axon and verify the accuracy of the model. The results showed that there are difference in theory and practice. Finally, they tried to analyze the sources of difference in many aspects.

In the actual medical detection, the detection of single axon or single nerve is generally unable to achieve in vivo, and the clinical detection of nerve bundles composed of multiple nerve fibers can be relatively easy. Therefore, it is more meaningful to study nerve bundles than single axons. In 1991, John. P. Wikswo’s team used the generalized volume conduction model to calculate the composite action potential and current of a nerve bundle [

100,

101,

102]. The effects of propagation distance and frequency-related conductivity on the composite action signals of various nerve bundles were also studied. At present, the detection of neuromuscular diseases is developing towards the goal of non-invasive, but the detection and calculation of single nerve bundle still fails to meet the demand. The most commonly detected nerves or muscles in clinical tests are superficial shallower below the surface of the skin. In order to study the mechanism and working mechanism of nerve control muscle, the detection of single motor unit compound action potential and potential calculation has been used to in vitro sensor to detect magnetic field. In 1997, Wikswo’s team [

103] developed a simple model to calculate the magnetic field strength of a single moving unit compound action potential at a certain point. Finally, the model was applied to the composite action potentials obtained by SQUID, and information about the distribution of action currents and the anatomical characteristics of individual motor units in muscle bundles could be obtained. In 1998, Tadashi Masuda’s team [

104] used SQUID system to detect magnetic fields in the lateral and medial muscles of three healthy men, and calculated the results using dipole model and volume conductor model to improve the accuracy of measurement. With the development and progress of computer technology, the method of using software simulation has become a good means to combine with experiment. In 2021, Siming Zuo’s team proposed a compact muscle model [

79]. COMSOL simulation software was used to establish the model and characterize the action potential of soleus muscle. Meanwhile, MATLAB was used to derive the relationship between magnetic and electrical signals in physics and mathematics.

Because of the large number and different shapes of human nerves and muscles, it is difficult to propose a universal model, but it is also urgently needed to further promote the development of magnetic field detection in clinical applications.

5. Conclusions

So far, SQUID is the sensor with the highest sensitivity to detect neuromuscular magnetic field, and its application advantages in clinical detection are not obvious. However, SQUID is the best choice for basic research on neuromuscular pathogenesis and current propagation mechanism. In this paper, the sensor related technologies, including devices, circuits, the relevant environmental testing and noise suppression technology in the field of weak magnetic detection are introduced, and the future development trend of neuromuscular magnetic is described. Finally, the status quo and development of neuromuscular magnetic field detection at home and abroad are summarized and described from the aspects of application and modeling. Due to the characteristics of the magnetic field, MMG will play a significant role in medical diagnosis, thus improving the level of human health.

Author Contributions

Paper writing and most of the content research, Zhidan Zhang; Circuit content part research, Anran He; Passive shielding survey, Zihan Xu; Coil compensation scheme investigation, Kun Yang; Paper revision and supervision of the writing process, Xiangyan Kong. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62071265 and partly supported by the One Health Interdisciplinary Research Project, Ningbo University.

References

- Briggs, A. M., Cross, M. J., Hoy, D. G., Sànchez-Riera, L., Blyth, F. M., Woolf, A. D., March, L Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: a report for the 2015 World Health Organization world report on ageing and health. The Gerontologist 2016, 56, S243-S255.

- Kramer, J. S., Yelin, E. H., Epstein, W. V. Social and economic impacts of four musculoskeletal conditions. Arthritis and Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology 1983, 26, 901-907.

- Rosenfeld, S. B., Schroeder, K., Watkins-Castillo, S. I. The economic burden of musculoskeletal disease in children and adolescents in the United States.Journal Abbreviation 2018, 38, e230-e236.

- Ma, K., Zhuang, Z. G., Wang, L., Liu, X. G., Lu, L. J., Yang, X. Q., Liu, Y. Q. The Chinese Association for the Study of Pain (CASP): consensus on the assessment and management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Pain Research and Management 2019.

- James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., Briggs, A. M. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2018, 392, 1789-1858.

- Yelin, E. H., Felts, W. R. A summary of the impact of musculoskeletal conditions in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 33, 750-755.

- Mongiovi, J., Shi, Z., Greenlee, H. Complementary and alternative medicine use and absenteeism among individuals with chronic disease. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2016 16, 1-12.

- Bevan, S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Practice and Research Clinical Rheumatology 2015, 29, 356-373.

- Bromberg, M. B. The motor unit and quantitative electromyography. Muscle and Nerve 2020, 61, 131-142.

- Klotz, T., Gizzi, L., Yavuz, U. Ş., Röhrle, O. Modelling the electrical activity of skeletal muscle tissue using a multi-domain approach. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology 2020, 19, 335-349.

- Zhang, Q., Zhu, J. The Application of EMG and Machine Learning in Human Machine Interface. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Intelligent Computing 2022, 465-469.

- Auchincloss, C. C., McLean, L. The reliability of surface EMG recorded from the pelvic floor muscles. Journal of neuroscience methods 2009, 182, 85-96.

- Rubin, D. I. Needle electromyography: Basic concepts. Handbook of clinical neurology 2019, 160, 243-256.

- Bostanabad, S. K., Azghani, M. R. Evaluation of the Activity and Dimensions Changes of the Skeletal Muscles During Different Activities: A Systematic Review. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation 2017, 11, 73-84.

- Krieg, S. M., Shiban, E., Buchmann, N., Gempt, J., Foerschler, A., Meyer, B., Ringel, F. Utility of presurgical navigated transcranial magnetic brain stimulation for the resection of tumors in eloquent motor areas. Journal of neurosurgery 2012, 116, 994-1001.

- Cohen, D., Givler, E. Magnetomyography: Magnetic fields around the human body produced by skeletal muscles. Applied Physics Letters 1972, 21, 114-116.

- Drung, Dietmar. The PTB 83-SQUID system for biomagnetic applications in a clinic. IEEE transactions on applied superconductivity 1995, 5, 2112-2117.

- Itozaki, H. SQUID application research in Japan. uperconductor Science and Technology 2003, 16, 1340.

- Taulu, S., Hari, R. Removal of magnetoencephalographic artifacts with temporal signal-space separation: Demonstration with single-trial auditory-evoked responses. Journal Abbreviation 2009, 30, 1524-1534.

- Z. Zhang, H. Wang, B. Wu, Z. Xu, X. Kong and T. Liang. Muscle Magnetic Signal Measurement Using High Sensitive Superconducting Sensor. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Applied Superconductivity and Electromagnetic Devices (ASEMD) 2020, 1–2.

- Zuo, S., Heidari, H., Farina, D., Nazarpour, K. The title of the cited article. Miniaturized magnetic sensors for implantable magnetomyography. 2020, 5, 2000185.

- Parvizi, H., Zuo, S., Wang, H., Nazarpour, K., Marquetand, J., Heidari, H. The title of the cited article. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17.

- Zhang, M., La Rosa, P. S., Eswaran, H., Nehorai, A. Estimating uterine source current during contractions using magnetomyography measurements. PloS one 2018, 13, e0202184.

- Mackert, B. M., Curio, G., Burghoff, M., Marx, P. Mapping of tibial nerve evoked magnetic fields over the lower spine. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section 1997, 104, 322-327.

- Lobekin, V. N., Petrov, R. V., Bichurin, M. I., Rebinok, A. V., Sulimanov, R. A. Magnetoelectric sensor for measuring weak magnetic biological fields. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2018, 441, 012035.

- Zuo, S., Schmalz, J., Özden, M. Ö., Gerken, M., Su, J., Niekiel, F., Heidari, H. Ultrasensitive magnetoelectric sensing system for pico-tesla magnetomyography. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems 2020, 14, 971-984.

- K. Zhu and A. Kiourti. A Review of Magnetic Field Emissions From the Human Body: Sources, Sensors, and Uses. IEEE Open Journal of Antennas and Propagation 2022, 3, 732-744.

- Clarke, John, and Alex I.Braginski. The SQUID Handbook. Vol.I Weinheim: Wiley-Vch 2004.

- Tolpygo, S. K., Bolkhovsky, V., Weir, T. J., Johnson, L. M., Gouker, M. A., Oliver, W. D. Fabrication Process and Properties of Fully-Planarized Deep-Submicron Nb/Al–AlOx/Nb Josephson Junctions for VLSI Circuits. IEEE transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2014, 25, 1-12.

- Takeuchi, Naoki, et al. Adiabatic quantum-flux-parametron cell library designed using a 10 kA/cm2 niobium fabrication process Superconductor Science and Technology 2017, 30, 035002.

- Olaya, David, et al. Planarized process for single-flux-quantum circuits with self-shunted Nb/NbxSi1-x/Nb Josephson junctions IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2019, 29, 1-8.

- Ying, Liliang, et al. Development of 15kA/cm2 Fabrication Process for Superconducting Integrated Digital Circuits arXiv preprint arXiv 2023, 2304, 01588.

- José Martínez-Pérez, Maria, and Dieter Koelle. NanoSQUIDs: Basics and recent advances. Physical Sciences Reviews 2017, 2, 20175001.

- Ying, Liliang, et al. Development of multi-layer fabrication process for SFQ large scale integrated digital circuits. EEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2021, 31, 1-4.

- S. W. Leman, E. B. Golden, M. C. Guyton, K. K. Ryu, V. K. Semenov and A. Wynn. Integrated Superconducting Transition-Edge-Sensor Energy Readout (ISTER). IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2023.

- Xu, Da, et al. Low-noise second-order gradient SQUID current sensors overlap-coupled with input coils of different inductances. uperconductor Science and Technology 2022, 35, 085004.

- https://starcryo.com/.

- D. Drung et al. Highly Sensitive and Easy-to-Use SQUID Sensors. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2007, 17, 699-704.

- Doriese. W B, et al. Developments in time-division multiplexing of x-ray transition-edge sensors. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2016, 184, 389–395.

- Kempf S, Ferring A, Fleischmann A and Enss C. Direct-current superconducting quantum interference devices for the readout of metallic magnetic calorimeters. Supercond.Sci.Technol. 2015, 28, 045008.

- Wu, Wentao, et al. Development of series SQUID array with on-chip filter for TES detector. Chinese Physics B 2022, 31, 028504.

- B. Kim, K. -K. Yu, J. -M. Kim and Y. -H. Lee. Comparison of Double Relaxation Oscillation SQUIDs and DC-SQUIDs of Large Stewart-McCumber Parameter. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2023, 33, 1-4.

- M. Schmelz et al. Thin-Film-Based Ultralow Noise SQUID Magnetometer. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2016, 26, 1-5.

- Forgacs R L. Digital-analog magnetometer utilizing superconducting sensor. Review of Scientific Instruments 1967, 38, 214-220.

- Koch R H, Rozen J R, Woltgens P, et al. High performance superconducting quantum interference device feedback electronics. Review of Scientific Instruments 1996, 67, 2968-2976.

- Koch, Roger H., et al. Flicker (1/f) noise in tunnel junction dc SQUIDs. Journal of low temperature physics 1983, 51, 207-224.

- Wellstood, Frederick C., Cristian Urbina, and John Clarke. Low-frequency noise in dc superconducting quantum interference devices below 1 K. Applied Physics Letters 1987, 50, 772-774.

- Drung, D., et al. Low-noise high-speed dc superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer with simplified feedback electronics. Applied physics letters 1990, 57, 406-408.

- Seppa, H., et al. dc-SQUID electronics based on adaptive positive feedback: experiments. IEEE transactions on magnetics 1991, 27, 2488-2490.

- Xie, Xiaoming, et al. A voltage biased superconducting quantum interference device bootstrap circuit. Superconductor science and technology 2010, 23, 065016.

- Chang, Kai, et al. A simple SQUID system with one operational amplifier as readout electronics. Superconductor science and technology 2014, 27, 115004.

- Bick, M., et al. A HTS rf SQUID vector magnetometer for geophysical exploration. IEEE transactions on applied superconductivity 1999, 9, 3780-3785.

- http://tristantech.com/general/.

- Hato, T., et al. Development of HTS-SQUID magnetometer system with high slew rate for exploration of mineral resources. Superconductor Science and Technology 2013, 26, 115003.

- Keenan, Shane T., et al. High-T c superconducting electronic devices based on YBCO step-edge grain boundary junctions. IEICE transactions on electronics 2013, 96, 298-306.

- Chwala, A., et al. Noise characterization of highly sensitive SQUID magnetometer systems in unshielded environments. Superconductor Science and Technology 2013, 26, 035017.

- Wei, Songrui, et al. Recent progress of fluxgate magnetic sensors: basic research and application. Sensors 2021, 21, 1500.

- Hiles, Michael L., et al. Power frequency magnetic field management using a combination of active and passive shielding technology. EEE Transactions on power delivery 1998, 13, 171-179.

- Thiel, F., Schnabel, A., Knappe-Grüneberg, S., Stollfuß, D., Burghoff, M. Demagnetization of magnetically shielded rooms. Review of scientific instruments 2007, 78.

- Mager, A. The Berlin magnetically shielded room (BMSR). In Biomagnetism: Proceedings. Third International Workshop, Berlin (West), May 1980. Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG 2019.

- Cohen, D., Schläpfer, U., Ahlfors, S., Hämäläinen, M., Halgren, E. New six-layer magnetically-shielded room for MEG. In Proceedings of the 13th international conference on biomagnetism. Jena, Germany: VDE Verlag 2002, 10, 919-921.

- Kajiwara, G., Harakawa, K., Ogata, H., Kado, H. High-performance magnetically shielded room. IEEE transactions on Magnetics 1996, 32, 2582-2585.

- Zhao, F., Zhou, X., Zhou, W., Zhang, X., Wang, K., Wang, W. Research on the design of axial uniform coils for residual field compensation in magnetically shielded cylinder. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1-9.

- Iivanainen, J., Zetter, R., Grön, M., Hakkarainen, K., Parkkonen, L. On-scalp MEG system utilizing an actively shielded array of optically-pumped magnetometers. Neuroimage 2019, 194, 244-258.

- Holmes, N., Tierney, T. M., Leggett, J., Boto, E., Mellor, S., Roberts, G., Bowtell, R. Balanced, bi-planar magnetic field and field gradient coils for field compensation in wearable magnetoencephalography. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 14196.

- Jodko-Władzińska, A., Wildner, K., Pałko, T., Władziński, M. Compensation system for biomagnetic measurements with optically pumped magnetometers inside a magnetically shielded room. Sensors 2020, 20, 4563.

- Holmes, N., Rea, M., Hill, R. M., Leggett, J., Edwards, L. J., Hobson, P. J., Bowtell, R. Enabling ambulatory movement in wearable magnetoencephalography with matrix coil active magnetic shielding. Neuroimage 2023, 274, 120157.

- Fife, A. A., et al. Synthetic gradiometer systems for MEG. EEE transactions on applied superconductivity 1999, 9, 4063-4068.

- Kong, X., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Zeng, J., Xie, X. Multi-channel magnetocardiogardiography system based on low-Tc SQUIDs in an unshielded environment. Physics procedia 2012, 36, 286-292.

- Shanehsazzadeh, Faezeh, et al. High Tc SQUID based magnetocardiography system in unshielded environment. 23rd Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering 2015.

- Li, H., Zhang, S., Zhang, C., Xie, X. SQUID-based MCG measurement using a full-tensor compensation technique in an urban hospital environment. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2016, 26, 1-5.

- Okada, Y., Hämäläinen, M., Pratt, K., Mascarenas, A., Miller, P., Han, M., Paulson, D. BabyMEG: A whole-head pediatric magnetoencephalography system for human brain development research. Review of Scientific Instruments 2016, 87.

- Akinrodoye, Micky A., and Forshing Lui. Neuroanatomy, somatic nervous system.2020.

- Krause, H. J., Wolf, W., Glaas, W., Zimmermann, E., Faley, M. I., Sawade, G., Krieger, J. SQUID array for magnetic inspection of prestressed concrete bridges. Physica C: Superconductivity 2002, 368, 91-95.

- Adachi, Y., Kawabata, S., Fujihira, J. I., Uehara, G. Multi-channel SQUID magnetospinogram system with closed-cycle helium recondensing. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2016, 27, 1-4.

- Yang, K., Chen, H., Kong, X., Lu, L., Li, M., Yang, R., Xie, X. Weakly damped SQUID gradiometer with low crosstalk for magnetocardiography measurement. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2016, 26, 1-5.

- Meyer, A., Meyer, N., Schaeffer, M., Gottenberg, J. E., Geny, B., Sibilia, J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory myopathies: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 50-63.

- Preston, David C., and Barbara E. Shapiro. Electromyography and neuromuscular disorders e-book: clinical-electrophysiologic correlations (Expert Consult-Online). Elsevier Health Sciences 2012.

- Zuo, Siming, et al. Modelling and Analysis of Magnetic Fields from Skeletal Muscle for Valuable Physiological Measurements. arXiv preprint arXiv 2021, 2104.

- Llinás, R. R., Ustinin, M., Rykunov, S., Walton, K. D., Rabello, G. M., Garcia, J., Sychev, V. Noninvasive muscle activity imaging using magnetography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 4942-4947.

- Elzenheimer, Eric, et al. Magnetoneurograhy of an Electrically Stimulated Arm Nerve: Usability of Magnetoelectric (ME) Sensors for Magnetic Measurements of Peripheral Arm Nerves. Current Directions in Biomedical Engineering, 2018 4, 363-366.

- Escalona-Vargas, D., Siegel, E. R., Oliphant, S., Eswaran, H. Evaluation of pelvic floor muscles in pregnancy and postpartum with non-invasive magnetomyography. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine 2021, 10, 1-6.

- Adachi, Y., Kawabata, S., Hashimoto, J., Okada, Y., Naijo, Y., Watanabe, T., Uehara, G. Multichannel SQUID magnetoneurograph system for functional imaging of spinal cords and peripheral nerves. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2021, 31, 1600405.

- Adachi, Y., Kawai, J., Haruta, Y., Miyamoto, M., Kawabata, S., Sekihara, K., Uehara, G. Recent advancements in the SQUID magnetospinogram system. Superconductor Science and Technology 2017, 30, 063001.

- Ushio, S., Hoshino, Y., Kawabata, S., Adachi, Y., Sekihara, K., Sumiya, S., Okawa, A. Visualization of the electrical activity of the cauda equina using a magnetospinography system in healthy subjects. Clinical Neurophysiology 2019, 130, 1-11.

- Watanabe, T., Kawabata, S., Hoshino, Y., Ushio, S., Sasaki, T., Miyano, Y., Okawa, A. Novel functional imaging technique for the brachial plexus based on magnetoneurography. Clinical Neurophysiology 2019, 130, 2114-2123.

- Miyano, Y., Kawabata, S., Akaza, M., Sekihara, K., Hoshino, Y., Sasaki, T., Okawa, A. Visualization of electrical activity in the cervical spinal cord and nerve roots after ulnar nerve stimulation using magnetospinography. Clinical Neurophysiology 2020, 131, 2460-2468.

- Sasaki, T., Kawabata, S., Hoshino, Y., Sekihara, K., Adachi, Y., Akaza, M., Okawa, A. Visualization of electrophysiological activity at the carpal tunnel area using magnetoneurography. Clinical Neurophysiology 2020, 131, 951-957.

- Hoshino, Y., Kawabata, S., Adachi, Y., Watanabe, T., Sekihara, K., Sasaki, T. Okawa, A. Magnetoneurography as a novel functional imaging technique for the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Clinical Neurophysiology 2022, 138, 153-162.

- Eswaran, H., Preissl, H., Wilson, J. D., Murphy, P., Lowery, C. L. Prediction of labor in term and preterm pregnancies using non-invasive magnetomyographic recordings of uterine contractions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2006, 1598-1602.

- Eswaran, H., Preissl, H., Murphy, P., Wilson, J. D., Lowery, C. L. Spatial-temporal analysis of uterine smooth muscle activity recorded during pregnancy. In 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference 2008, 10, 6665-6667.

- Eswaran, H., Govindan, R. B., Furdea, A., Murphy, P., Lowery, C. L., Preissl, H. T. Extraction, quantification and characterization of uterine magnetomyographic activity—a proof of concept case study. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2009, 144, S96-S100.

- Mackert, B. M., Mackert, J., Wübbeler, G., Armbrust, F., Wolff, K. D., Burghoff, M., Curio, G. Magnetometry of injury currents from human nerve and muscle specimens using superconducting quantum interferences devices. Neuroscience letters 1999, 262, 163-166.

- Garcia, M. A., Baffa, O. Magnetic fields from skeletal muscles: A valuable physiological measurement? Frontiers in physiology 2015, 6, 228.

- Escalona-Vargas, D., Oliphant, S., Siegel, E. R., Eswaran, H. Characterizing pelvic floor muscles activities using magnetomyography. Neurourology and urodynamics 2019, 38, 151-157.

- Van Egeraat, J. M., Friedman, R. N., Wikswo, J. P. Magnetic field of a single muscle fiber. First measurements and a core conductor model.Biophysical Journal 1990, 57, 663-667.

- Barach, J. P., Roth, B. J., Wikswo, J. P. Magnetic measurements of action currents in a single nerve axon: A core-conductor model. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 1985, 2, 136-140.

- Woosley, J. K., Roth, B. J., Wikswo Jr, J. P. The magnetic field of a single axon: A volume conductor model. Mathematical Biosciences 1985, 76, 1-36.

- Roth, B. J., Wikswo, J. P. The magnetic field of a single axon. A comparison of theory and experiment. Biophysical journal 1985, 48, 93-109.

- Wijesinghe, R. S., Gielen, F. L., Wikswo, J. P. A model for compound action potentials and currents in a nerve bundle I: The forward calculation. Annals of biomedical engineering 1991, 19, 43-72.

- Wijesinghe, R. S., Wikswo, J. P. A model for compound action potentials and currents in a nerve bundle II: A sensitivity analysis of model parameters for the forward and inverse calculations. Annals of biomedical engineering 1991, 19, 73-96.

- Wijesinghe, R. S., Gielen, F. L., Wikswo, J. P. A model for compound action potentials and currents in a nerve bundle III: A comparison of the conduction velocity distributions calculated from compound action currents and potentials. Annals of biomedical engineering 1991, 19, 97-121.

- Parker, K. K., Wikswo, J. P. A model of the magnetic fields created by single motor unit compound action potentials in skeletal muscle. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 1997, 44, 948-957.

- Masuda, T., Endo, H., Takeda, T. Magnetic fields produced by single motor units in human skeletal muscles. Clinical neurophysiology 1999, 110, 384-389.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).