Submitted:

15 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Patients

Adherence Assessment

Mental health Assessment

Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, G.; Halbert, J.; Crotty, M.; Shanahan, E.M.; Batterham, M.; Ahern, M. The effect of treatment on radiological progression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Rheumatology. 2003, 42, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combe, B.; Landewe, R.; Daien, C.I.; Hua, C.; Aletaha, D.; Álvaro-Gracia, J.M.; et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017, 76, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Nice: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018.

- Taylor, P.C.; Balsa Criado, A.; Mongey, A.B.; Avouac, J.; Marotte, H.; Mueller, R.B. How to get the most from methotrexate (MTX) treatment for your rheumatoid arthritis patient? -MTX in the treat-to-target strategy. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krüger, K.; Wollenhaupt, J.; Albrecht, K.; Alten, R.; Backhaus, M.; Baerwald, C.; et al. European League of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR). S1-Leitlinie der DGRh zur sequenziellen medikamentösen Therapie der rheumatoiden Arthritis 2012. Adaptierte EULAR-Empfehlungen und aktualisierter Therapiealgorithmus [German 2012 guidelines for the sequential medical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adapted EULAR recommendations and updated treatment algorithm]. Z Rheumatol. 2012, 71, 592–603. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell, J.R.; Curtis, J.R.; Mikuls, T.R.; Cofield, S.S.; Bridges, S.L. Jr; Ranganath, V.K.; et al. ; TEAR Trial Investigators. Validation of the methotrexate-first strategy in patients with early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis: results from a two-year randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choy, E.H.; Smith, C.M.; Farewell, V.; Walker, D.; Hassell, A.; Chau, L.; et al. CARDERA (Combination Anti-Rheumatic Drugs in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis) Trial Group. Factorial randomised controlled trial of glucocorticoids and combination disease modifying drugs in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hider, S.L.; Silman, A.; Bunn, D.; Manning, S.; Symmons, D.; Lunt, M. Comparing the long-term clinical outcome of treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine prescribed as the first disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodtkorb, E.; Samsonsen, C.; Sund, J.K.; Bråthen, G.; Helde, G.; Reimers, A. Treatment non-adherence in pseudo-refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, H.F. ; Bluett, J; Barton, A. ; Hyrich, K.L.; Cordingley, L.; Verstappen, S.M. Psychological factors predict adherence to methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis; findings from a systematic review of rates, predictors and associations with patient-reported and clinical outcomes. RMD Open. 2016, 2, e000171. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, J.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Aassi, M.; Schiff, M. Adherence and Persistence with Methotrexate in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. J Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 1997–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, G.W.; Mikuls, T.R.; Hayden, C.L.; Ying, J.; Curtis, J.R.; Reimold, A.M.; Caplan, L.; Kerr, G.S.; Richards, J.S.; Johnson, D.S.; Sauer, B.C. Merging Veterans Affairs rheumatoid arthritis registry and pharmacy data to assess methotrexate adherence and disease activity in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011, 63, 1680–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cuyper, E.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S.; Van Camp, Y.; De Clerck, L.S. Determinants of methotrexate adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 1335–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Klerk, E; van der Heijde; D. ; Landewé, R.; van der Tempel, H.; Urquhart, J.; van der Linden, S. Patient compliance in rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, and gout. J Rheumatol 2003, 30, 44–54.

- van den Bemt, B.J.; Zwikker, H.E.; van den Ende, C.H. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012, 8, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999, 47, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangi, H.A.; Ndosi, M.; Adams, J.; Andersen, L.; Bode, C.; Boström, C.; et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015, 74, 954–962. [Google Scholar]

- Sowden, E.; Hassan, W.; Gooden, A.; Jepson, B.; Kausor, T.; Shafait, I.; et al. Limited end-user knowledge of methotrexate despite patient education: an assessment of rheumatologic preventive practice and effectiveness. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012, 18, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R. Compliance, adherence, and concordance. In: Taylor K, Harding G, eds. Pharmacy practice. London: Taylor & Francis, 2001, 148–167.

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O. 3rd; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar]

- Prevoo, M.L.; van ‘t Hof, M.A.; Kuper, H.H.; van Leeuwen, M.A.; van de Putte, L.B.; van Riel, P.L. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D. Scores for all seasons: SDAI and CDAI. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014, 32(5 Suppl 85), S-75–S-79. [Google Scholar]

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005, 23(5 Suppl 39), S100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Smolen, J.S.; Breedveld, F.C.; Schiff, M.H.; Kalden, J.R.; Emery, P.; Eberl, G.; van Riel, P.L.; Tugwell, P. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003, 42, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, B.; Fries, J.F. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, E.; van der Heijde, D.; van der Tempel, H.; van der Linden, S. Development of a questionnaire to investigate patient compliance with antirheumatic drug therapy. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26, 2635–2641. [Google Scholar]

- de Klerk, E.; van der Heijde, D.; Landewé, R.; van der Tempel, H.; van der Linden, S. The compliance-questionnaire-rheumatology compared with electronic medication event monitoring: a validation study. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cinar, F.I.; Cinar, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Acikel, C.; Erdem, H. ; Pay, S; et al. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of the Turkish Version of the Compliance Questionnaire on Rheumatology in Patients With Behçet’s Disease. J Transcult Nurs. 2016, 27, 480–486. [Google Scholar]

- Salt, E.; Hall, L.; Peden, A.R.; Home, R. Psychometric properties of three medication adherence scales in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Nurs Meas. 2012, 20, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, S.; Clifford, S.; Eliasson, L.; Barber, N.; Willson, A. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Common Mental Health Disorders: The NICE Guideline on Identification and Pathways to Care. National Clinical Guideline Number 123. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13476/54604/54604.pdf.

- Katchamart, W.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Chanapai, W.; Thaweeratthakul, P.; Srisomnuek, A. Prevalence of and factors associated with depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020, 23, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland. , I; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002, 52, 69–77.

- de Thurah, A.; Nørgaard, M.; Johansen, M.B.; Stengaard-Pedersen, K. Methotrexate compliance among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the influence of disease activity, disease duration, and co-morbidity in a 10-year longitudinal study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010, 39, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viller, F.; Guillemin, F.; Briançon, S.; Moum, T.; Suurmeijer, T.; van den Heuvel, W. Compliance to drug treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 3 year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, D.C.; Hertzog, C.; Leventhal, H.; Morrell, R.W.; Leventhal, E.; Birchmore, D.; Martin, M.; Bennett, J. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yajima, N.; Kawaguchi, T.; Takahashi, R.; Nishiwaki, H.; Toyoshima, Y.; Oh, K.; et al. Adherence to methotrexate and associated factors considering social desirability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Rheumatol. 2022, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurkmans, E.J.; Maes, S.; de Gucht, V.; Knittle, K.; Peeters, A.J.; Ronday, H.K.; Vlieland, T.P. Motivation as a determinant of physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010, 62, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, B.J.; Huang, X.; Zarotsky, V.; Globe, D. Trends in RA patients’ adherence to subcutaneous anti-TNF therapies and costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009, 25, 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, C.; Erlacher, L.; Fenzl, K.H.; Dorner, T.E. Medication Adherence and Coping Strategies in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Rheumatol. 2019, 2019, 4709645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, N.K.; Fischer, M.A.; Avorn, J.; Liberman, J.N.; Schneeweiss, S.; Pakes, J.; Brennan, T.A.; Shrank, W.H. The implications of therapeutic complexity on adherence to cardiovascular medications. Arch Intern Med. 2011, 171, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katchamart, W.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Sukprasert, N.; Chanapai, W.; Srisomnuek, A. Rate and causes of noncompliance with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug regimens in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.; Kwan, Y.H.; Seah, Y.; Low, L.L.; Fong, W.; Thumboo, J. A systematic review of the barriers affecting medication adherence in patients with rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. 2017, 37, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J.S. Effectiveness profiles and dose dependent retention of traditional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. An observational study. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ideguchi, H.; Ohno, S.; Ishigatsubo, Y. Risk factors associated with the cumulative survival of low-dose methotrexate in 273 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007, 13, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Marroquín, R.; Contreras-Yáñez, I.; Alcocer-Castillejos, N.; Pascual-Ramos, V. Major depressive episodes are associated with poor concordance with therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients: the impact on disease outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014, 32, 904–913. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, M.; van de Laar, M.A.; Bernelot Moens, H.J.; Kruijsen, M.W.; Haagsma, C.J. Longterm observational study of methotrexate use in a Dutch cohort of 1022 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 2325–2329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasir, S.J. Alrubaye; Mohammed, B.M. Al-Juboori; Ameer, K. Al-Humairi. The Causes of Non-Adherence to Methotrexate in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Research J. Pharm. and Tech. 2021, 14, 769–774. [Google Scholar]

- Treharne, G.; Lyons, A.; Kitas, G. Medication adherence in Rheumatoid arthritis: effects of psychosocial factors. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2004, 9, 337–349. [Google Scholar]

| All (n=111) | VAS | MARS-5 | CQR19 | |||||||

| Variable | Adherent | Nonadherent | p | Adherent | Nonadherent | p | Adherent | Nonadherent | p | |

| Female n (%) | 87 (78,4) | 72 (78.3) | 15 (78.9) | 1 | 64 (82.1) | 22 (68.8) | 0.201 | 48 (88.9) | 38 (67.9) | 0.015 |

| Male n (%) | 24 (21.6) | 20 (21.7) | 4 (21.1) | 14 (17.9) | 10 (31.3) | 6 (11.1) | 18 (32.1) | |||

| Age (yrs) | 56.2±10.6 | 56.0±9.9 | 57.1±13.8 | 0.708 | 56.3±10.5 | 56.5±10.9 | 0.927 | 54.2±10.1 | 58.5±10.6 | 0.031 |

| Living city, n (%) | 88 (79.3) | 73 (79.3) | 15 (78.9) | 1 | 66 (84.6) | 21 (65.6) | 0.049 | 43 (79.6) | 44 (78.6) | 1 |

| Living countryside, n (%) | 23 (20.7) | 19 (20.7) | 4 (21.1) | 12 (15.4) | 11 (34.4) | 11 (20.4) | 12 (21.4) | |||

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Unemployed n (%) | 31 (27.9) | 27 (29.3) | 4 (21.1) | 0.564 | 23 (29.5) | 8 (25.0) | 0.861 | 18 (33.3) | 13 (23.3) | 0.24 |

| Employed n (%) | 39 (35.1) | 33 (35.9) | 6 (31.6) | 27 (34.6) | 11 (34.4) | 20 (37.0) | 18 (32.1) | |||

| Retiree n (%) | 41 (36.9) | 32 (34.8) | 9 (47.7) | 28 (35.9) | 13 (40.6) | 16 (29.6) | 25 (44.6) | |||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Primary n (%) | 9 (8.1) | 7 (7.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0.896 | 5 (6.4) | 4 (12.5) | 0.528 | 3 (5.6) | 6 (10.7) | 0.539 |

| Secondary n (%) | 76 (68.5) | 63 (68.5) | 13 (68.4) | 55 (70.5) | 20 (62.5) | 39 (72.2) | 36 (64.3) | |||

| Higher n (%) | 26 (23.4) | 22 (23.9) | 4 (21.1) | 18 (23.1) | 8 (25.0) | 12 (22.2) | 14 (25.0) | |||

| Nonsmoker n (%) | 54 (48.6) | 44 (47.8) | 10 (52.6) | 0.742 | 38 (48.7) | 15 (46.9) | 0.936 | 22 (40.7) | 31 (55.4) | 0.308 |

| Ex-smoker n (%) | 25 (22.5) | 22 (23.9) | 3 (15.8) | 17 (21.8) | 8 (25.0) | 14 (25.9) | 11 (19.6) | |||

| Smoker n (%) | 32 (28.8) | 26 (28.3) | 6 (31.6) | 23 (29.5) | 9 (28.1) | 18 (33.3) | 14 (25.0) | |||

| Comorbidities: n (%) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 37 (33.3) | 32 (34.8) | 5 (26.3) | 0.373 | 28 (35.9) | 8 (25.0) | 0.039 | 22 (40.7) | 14 (25.0) | 0.243 |

| 1 | 30 (27.0) | 22 (23.9) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (20.5) | 14 (43.8) | 12 (22.2) | 18 (32.1) | |||

| 2 | 21 (18.9) | 19 (20.7) | 2 (10.5) | 14 (17.9) | 7 (21.9) | 8 (14.8) | 13 (23.2) | |||

| ≥ 3 | 23 (20.7) | 19 (20.7) | 4 (21.1) | 20 (26.6) | 3 (9.4) | 12 (22.2) | 11 (19.6) | |||

| Disease duration (yrs) | 6 (3-13.5) | 6 (3-13) | 7 (4-17) | 0.452 | 6 (3-13.8) | 6 (3.3-13.5) | 1 | 6 (3.8-14.3) | 6 (3-10.3) | 0.37 |

| Physician visits (per year) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 3 (2-4) | 0.036 | 4 (3-6) | 3 (3-7.5) | 0.285 | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-5.8) | 0.812 |

| Tender joint count (n) | 5 (1-10) | 5 (1-10) | 4 (0-12) | 0.488 | 6 (1-10) | 4 (0-9.5) | 0.298 | 4.5 (1-10) | 5 (1-11) | 0.797 |

| Swollen joint count (n) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-2.5) | 0 (0-4) | 0.635 | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-3.8) | 0.629 | 0.5 (0-2.8) | 0 (0-3) | 0.869 |

| SE (mm/h) | 26 (14-52) | 26 (14-51) | 39 (20-63) | 0.187 | 26 (12-51) | 28 (17.5-72.75) | 0.293 | 24 (13-47.5) | 28 (14.75-62.25) | 0.154 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 3.89 (1.28-14.99) | 3.42 (1.00-13.96) | 4.75 (2.98-18.3) | 0.197 | 3.05 (0.92-10.03) | 6.5 (2.39-15.73) | 0.062 | 2.87 (0.87-9.53) | 5.21 (2-19) | 0.042 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 12.7 (3.59-42.26) | 14.34 (3.23-13.96) | 5.38 (4.43-42.2) | 0.599 | 12.08 (2.89-42.26) | 14.2 (4.03-41.75) | 0.832 | 16.68 (7.76-43.24) | 4.7 (2-40.34) | 0.059 |

| Dosage MTX (mg) | 15(10-17.5) | 15 (10-17.5) | 12.5 (10-15) | 0.03 | 15 (10-17.5) | 12.5 (10-15) | 0.22 | 15 (10-17.5) | 15 (10-17.5) | 0.506 |

| Side effects of MTX, n (%) | 31 (28.2) | 23 (25.0) | 8 (42.1) | 0.218 | 20 (25.6) | 11 (34.4) | 0.489 | 12 (22.2) | 19 (33.9) | 0.249 |

| Concomitant steroids, n (%) | 96 (86.5) | 82 (91.1) | 14 (73.7) | 0.049 | 70 (92.1) | 25 (78.1) | 0.086 | 51 (96.2) | 44 (80.0) | 0.022 |

| Dosage of corticosteroids (mg) | 6.0(5-9.5) | 5.5 (5-8.5) | 7.5 (5-10) | 0.64 | 5 (5-8.5) | 7.5 (5-10) | 0.473 | 6 (5-10) | 5.5 (5-9.5) | 0.659 |

| sDMARD n (%) | 44 (39.6) | 35 (38.0) | 9 (47.4) | 0.618 | 26 (33.3) | 17 (53.1) | 0.086 | 17 (31.5) | 26 (46.4) | 0.158 |

| bDMARD n (%) | 34 (30.6) | 30 (32.6) | 4 (21.1) | 0.471 | 24 (30.8) | 10 (31.2) | 1,000 | 16 (29.6) | 18 (32.1) | 0.937 |

| CDAI | 17.7±12.4 | 17.8±12.8 | 17.3±10.3 | 0.894 | 17.9±12.7 | 16.97±11.8 | 0.732 | 16.4±11.5 | 18.7±13.2 | 0.347 |

| DAS28-ESR | 4.31±1.7 | 4.28±1.8 | 4.4±1.5 | 0.761 | 4.3±1.7 | 4.3±1.8 | 0.871 | 4.2±1.7 | 4.4±1.7 | 0.628 |

| HAQ | 0.9±0.5 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.881 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.935 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.694 |

| HADS depression | 7.6±3.5 | 7.4±3.5 | 9.0±3.7 | 0.072 | 7.1±3.5 | 8.8±3.3 | 0.03 | 7.2±3.4 | 7.9±3.7 | 0.246 |

| HADS anxiety | 6.1±3.8 | 5.8±3.7 | 7.6±4.0 | 0.07 | 6.0±4.0 | 6.2±3.1 | 0.776 | 6.6±4.1 | 5.6±3.4 | 0.204 |

| Scale | Adherence | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CQR19 | 76.92 ± 13.47 | Nonadherent | 56 (50.5) |

| Adherent | 54 (48.6) | ||

| MARS-5 | 22.63 ± 2.58 | Nonadherent | 32 (28.8) |

| Adherent | 78 (70.3) | ||

| VAS | 87.44 ± 16.49 | Nonadherent | 19 (17.1) |

| Adherent | 92 (82.9) |

| Baseline predictor | VAS | MARS-5 | CQR19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Gender | 1.042 (0.311-3.490) | 0.947 | 0.481(0.187-1.238) | 0.481 | 0.264 (0.095-0.730) | 0.010 |

| Age (yrs) | 1.009 (0.963-1.057) | 0.705 | 1.002 (0.963-1.042) | 0.926 | 1.041 (1.003-1.081) | 0.034 |

| Residence | 0.976 (0.209-3.283) | 0.969 | 0.347 (0.134-0.901) | 0.030 | 0.938 (0.374-2.353) | 0.891 |

| Employment status | 1.227 (0.314-4.799) | 0.768 | 1.171 (0.403-3.405) | 0.772 | 1.246 (0.479-3.242) | 0.652 |

| Education | 0.722 (0.134-3.879) | 0.704 | 0.455 (0.111-1.863) | 0.273 | 0.462 (0.107-1.984) | 0.299 |

| Tobacco use | 0.600 (0.150-2.404) | 0.471 | 1.192 (0.425-3.343) | 0.738 | 0.558 (0.213-1.457) | 0.233 |

| Comorbidities | 2.327 (0.672-8.060) | 0.183 | 3.062 (1.057-8.874) | 0.039 | 2.357 (0.875-6.351) | 0.090 |

| Disease duration (years) | 1.027 (0.967-1.092) | 0.385 | 0.997 (0.944-1.053) | 0.907 | 0.973 (0.925-1.023) | 0.286 |

| Physician visits (per year) | 0.904 (0.759-1.077) | 0.260 | 1.006 (0.889-1.137) | 0.929 | 1.007 (0.899-1.127) | 0.910 |

| Tender joint count | 0.974 (0.892-1.062) | 0.549 | 0.974 (0.907-1.046) | 0.464 | 0.996 (0.936-1.061) | 0.913 |

| Swollen joint count | 1.001 (0.841-1.191) | 0.992 | 1.007 (0.871-1.163) | 0.930 | 1.039 (0.908-1.189) | 0.579 |

| SE (mm/h) | 1.009 (0.995-1.023) | 0.226 | 1.005 (0.992-1.017) | 0.473 | 1.008 (0.996-1.020) | 0.186 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 1.001 (0.978-1.024) | 0.947 | 0.992 (0.971-1.014) | 0.498 | 1.005 (0.987-1.023) | 0.587 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 0.982 (0.948-1.018) | 0.327 | 1.003 (0.986-1.021) | 0.727 | 0.997 (0.981-1.013) | 0.711 |

| Dosage MTX (mg) | 0.881 (0.783-0.992) | 0.036 | 0.952 (0.864-1.048) | 0.314 | 0.981 (0.889-1.071) | 0.673 |

| Concomitant steroids | 0.273 (0.078-0.956) | 0.042 | 0.306 (0.094-0.998) | 0.050 | 0.157 (0.033-0.746) | 0.020 |

| Dosage of steroids (mg) | 1.019 (0.829-1.252) | 0.857 | 1.067 (0.905-1.258) | 0.440 | 0.995 (0.859-1.154) | 0.951 |

| sDMARDs | 1.303 (0.470-3.615) | 0.611 | 2.267 (0.980-5.244) | 0.056 | 1.886 (0.866-4.107) | 0.110 |

| bDMARDs | 0.677 (0.205-2.231) | 0.521 | 1.062 (0.424-2.662) | 0.898 | 1.143 (0.493-2.649) | 0.756 |

| Side effects of MTX | 2.182 (0.782-6.085) | 0.136 | 1.519 (0.624-3.696) | 0.357 | 1.797 (0.770-4.193) | 0.175 |

| CDAI | 0.997 (0.957-1.039) | 0.893 | 0.994 (0.960-1.029) | 0.729 | 1.016 (0.983-1.049) | 0.344 |

| DAS 28-ESR | 1.047 (0.781-1.404) | 0.759 | 0.980 (0.768-1.250) | 0.869 | 1.058 (0.846-1.323) | 0.624 |

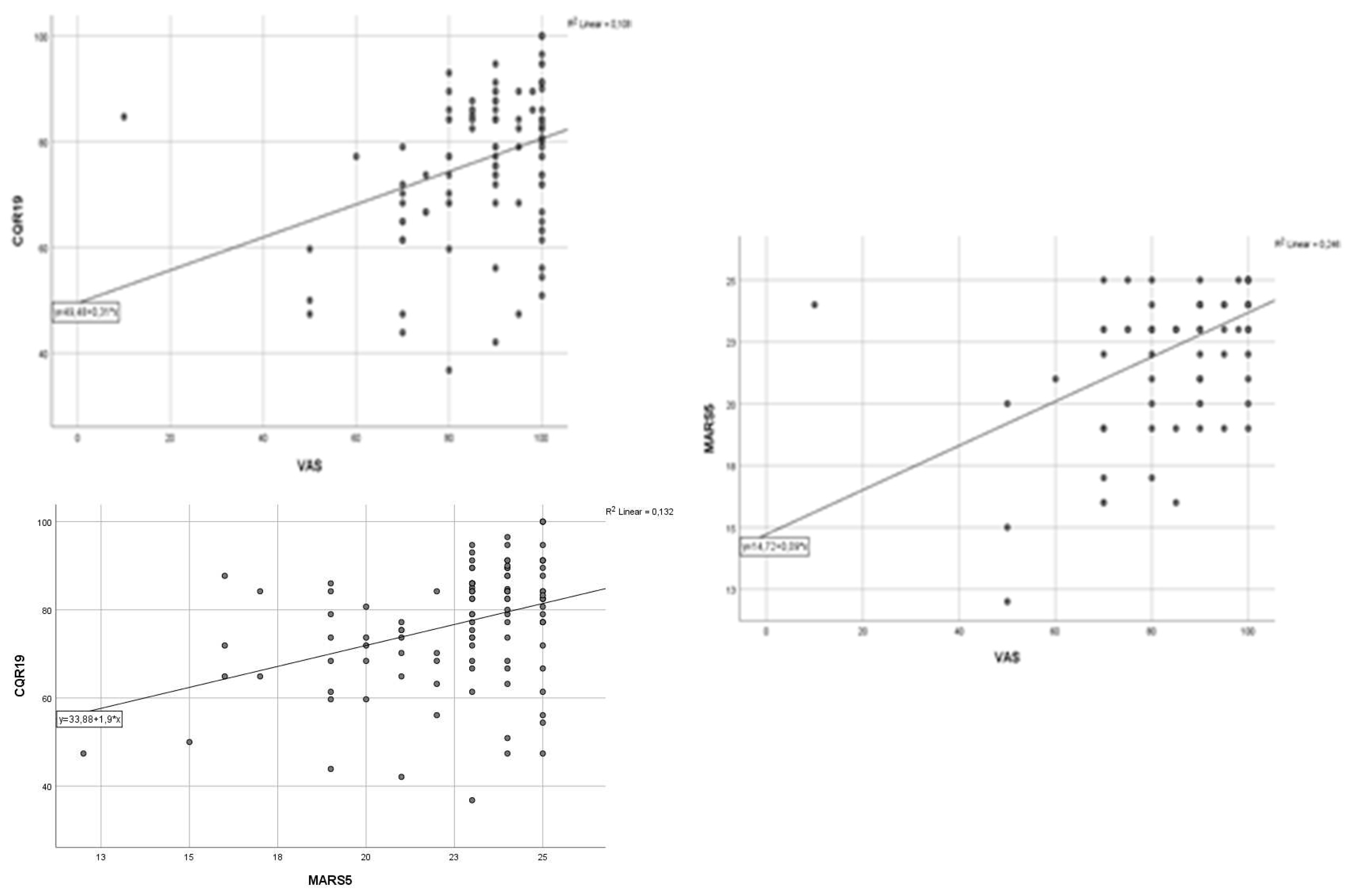

| VAS | 0.999 (0.976-1.022) | 0.942 | 1.006 (0.986-1.025) | 0.574 | 1.011 (0.993-1.029) | 0.246 |

| HAQ | 0.920 (0.315-2.690) | 0.879 | 1.038 (0.434-2.482) | 0.934 | 1.179 (0.524-2.654) | 0.691 |

| HADS depression | 1.137 (0.986-1.311) | 0.077 | 1.142 (1.010-1.293) | 0.035 | 1.068 (0.956-1.193) | 0.245 |

| HADS anxiety | 1.126 (0.988-1.283) | 0.076 | 1.017 (0.909-1.137) | 0.773 | 0.934 (0.842-1.038) | 0.204 |

| Predictor | OR (95%CI) | p |

| HADS depression | 1.131 (0.994-1.286) | 0.061 |

| Concomitant use of steroids | 0.281 (0.078-0.999) | 0.050 |

| Comorbidities | 0.805 (0.538-1.206) | 0.293 |

| Predictor | OR (95%CI) | p |

| Gender | 0.256 (0.088-0.742) | 0.012 |

| Age | 1.038 (0.996-1.082) | 0.075 |

| Concomitant use of steroids | 0.196 (0.039-0.992) | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).