1. Introduction

The Alcohol is one of the most widely-used licit drugs. Notably, it is a powerful reinforcing agent, and its chronic use can lead to addictive behaviors, characterized by the loss of control over intake and, importantly, compulsive alcohol-seeking and alcohol-taking behaviors despite negative health and socioeconomic consequences. However, a limited number of pharmacotherapeutic agents are available to treat this chronic and relapsing brain disorder.

The endogenous opioid system has been implicated in the rewarding and reinforcing actions of alcohol. For example, a number of studies have shown that nonselective opioid antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, reduce alcohol consumption in both humans and animals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. There is also evidence that opioid peptides are released following ethanol exposure [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Finally, increased opioid system activity following ethanol exposure in rodent lines selectively bred for alcohol preference has been associated with their propensity to drink relative to non-preferring strains [

7,

11].

The combined use of alcohol and opiates is also a major medical concern. Cases involving its concomitant use or where it is used as a substitution (e.g., opiate use during periods of abstinence from alcohol, the use of alcohol to cope with pain or the development of opiate addiction following prior problems with alcohol) have been reported [

12]. Numerous studies have shown that a history of alcohol use is a risk factor for increased opioid use. Compared to non-drinkers, binge drinkers were twice as likely to misuse prescription opioids, with frequency of binge drinking being a strong predictor of misuse [

13]. Among those with excessive alcohol use, the proportion expressing chronic pain was highly elevated (>50%) and this was correlated with higher non-prescription opioid use [

14,

15]. This is a serious issue for people who may consume alcohol while taking pain medications, as use of these substances together may lead to adverse health consequences such as the enhancement of shared CNS effects (e.g., sedation) as well as a risk of respiratory depression [

16]. Toxicologic analysis of victims of heroin overdose found an inverse relationship between blood ethanol and morphine concentrations in the blood, suggesting that the presence of alcohol could alter the acute effects of heroin [

17]. Recent reports have estimated that approximately 19% of opioid-related emergency department visits involved alcohol, and 22% of drug-related deaths involved both opioids and alcohol [

18]. Given its wide availability, alcohol has often been termed a gateway drug from which users turn to other illicit drugs.

Both alcohol and morphine have been shown to activate a common reward pathway, and each induces euphoria and has high potential for abuse. Morphine induces its rewarding effect by binding to MOP, in turn stimulating dopamine release within the mesolimbic reward system. Ethanol targets numerous neurotransmitter systems to exert its rewarding action. Among these, it can facilitate dopaminergic activity by stimulating the release of endogenous opioid peptides, which then act on opioid receptors, leading to its rewarding effects [for review, see [

19]]. Several studies have also reported an interaction between alcohol and exogenous opioids. For example, there is evidence showing the development of cross-tolerance to the analgesic effect of ethanol in morphine-treated mice [

20]. Furthermore, prior injection of morphine increased intake of an ethanol solution in rats [

21]. In human studies, higher alcohol consumption was associated with altered response to an oral dose of oxycodone indicated by attenuated miosis, poorer performance on cognitive tests and higher subjective rating of the positive effects of oxycodone [

22]. Together, these studies suggest that changes in drug sensitivity due to the co-use of these substances could lead to altered intake and increased risk for abuse.

We previously found that the rewarding action of ethanol was reduced in mice lacking both beta-endorphin and enkephalins, suggesting that these opioid peptides mediate, at least in part, the rewarding action of alcohol [

23]. Here we propose that if alcohol alters the level of endogenous opioids, exogenously administered opioids should also crosstalk with alcohol. Previous studies have shown that small doses of morphine increase animals’ intake of alcohol [

24]. Given that opioids can also influence consummatory behaviors [

25], however, it is difficult to distinguish whether this effect was due to morphine modifying the motivational processes underlying alcohol reward/reinforcement or to a more nonspecific effect on feeding. Therefore, we used the place conditioning paradigm as a measure of reward [

26], and assessed if ethanol-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) would display crosstalk with morphine. We then determined the role of MOP in this response, in which we compared MOP knockout mice to their wild-type littermates/controls. This was to confirm that MOP mediates morphine’s actions. We then evaluated which endogenous opioid peptides would be involved in the crosstalk between alcohol and morphine, in which we utilized mice lacking β-end and/or enkephalins and their wild-type controls.

2. Materials and Methods

Female mice between the ages of 2-4 months at the time of experiments were used throughout. We used female mice because they exhibit a significantly greater CPP response than male mice following an ethanol conditioning protocol similar to that used in the current study [

27]. Mice lacking MOP [

28], β-endorphin [

29] and enkephalin [

30] and their respective wild-type controls, fully backcrossed on a C57BL/6J mouse background, originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were bred in house. Male and female heterozygous mice of each genotype or both lines were generated and then mated to obtain mice lacking β-endorphin, enkephalins or β-endorphin and enkephalins and their respective wild-type littermates/controls. Mice were housed up to 4 per cage, with food and water available

ad libitum throughout the study. They were kept in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with standard 12 h light/dark cycle. All experiments were carried out during the light phase between 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Mice were habituated to the testing room at least 1 day prior to the start of the experiment and remained there until the end of the experiment. All procedures were in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Western University of Health Sciences (Pomona, California, USA).

Alcohol solutions were prepared from ethyl alcohol (200 Proof, OmniPur, EM Science; Gibbstown, NJ) and saline to the appropriate concentrations, and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a volume of 0.1 mL/10 g body weight. Morphine, generously supplied by the Drug Supply program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), was dissolved in saline and injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in a volume of 0.1 mL/10 g body weight.

A 3-chambered place conditioning apparatus (ENV-3013, Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT) was used. The apparatus was divided into two large chambers of equal size (16.8 x 12.7 x 12.7 cm), connected by a small central chamber (7.2 x 12.7 x 12.7 cm) and separated by manual guillotine doors. The two side chambers contained distinct visual and tactile cues. One chamber had a white wall with horizontal or vertical black stripes and steel mesh floor while the opposite chamber had a black wall with horizontal or vertical white stripes and solid steel rod floors. The central neutral chamber had solid gray walls and floor and served as the entry point to the apparatus. The apparatus was equipped with infrared beams connected to a computer system with software (MED-PC IV, Med Associates Inc.) to monitor and record the amount of time that mice spent in each chamber.

The place conditioning procedure consisted of three distinct phases conducted over a 5-day period: preconditioning (day 1), conditioning with saline or ethanol (days 2-4) and postconditioning (day 5). On the preconditioning test day, mice were tested for baseline place preference, in which they were placed in the central neutral gray chamber and allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus for 15 min under a drug-free state. The amount of time that mice spent in each conditioning chamber was recorded. Conditioning was conducted using a biased design, in which mice received ethanol (2 g/kg) in the initially non-preferred side and saline in the initially preferred side in a counterbalanced manner. Every attempt was made to include knockout mice with their respective wild-type controls in each set of animals undergoing testing and conditioning. Additionally, each experiment was conducted using at least three cohorts of 3-5 mice per genotype. During the conditioning days (days 2-4), animals received an injection of ethanol (2g/kg, i.p.) or saline in the morning and were immediately confined to the corresponding ethanol- or saline-paired chamber for 15 min. In the afternoon, they received the alternate treatment and were confined to the opposite chamber for 15 min. The morning and afternoon conditioning sessions were separated by 4 h. On the postconditioning test day, mice were again placed in the central chamber and allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus for 15 min. The amount of time that mice spent in each chamber was recorded in the same manner as for the preconditioning test. Mice were left undisturbed in their home cages over the next 2 days.

Experiment 1. We determined if mice conditioned with ethanol would display greater CPP when challenged with morphine. Mice were conditioned as described above and on day 8 tested for CPP following saline or a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg, s.c.). Mice were then immediately placed in the place conditioning apparatus. The amount of time that mice spent in each chamber was recorded for 15 min.

Experiment 2. We then assessed the role of MOP in this response, in which we compared MOP knockout mice to their wild-type littermates/controls. This was to confirm that morphine’s actions were via MOP. Mice were conditioned as described above and on day 8 tested for CPP following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg, s.c.). The amount of time that mice spent in each chamber was recorded for 15 min.

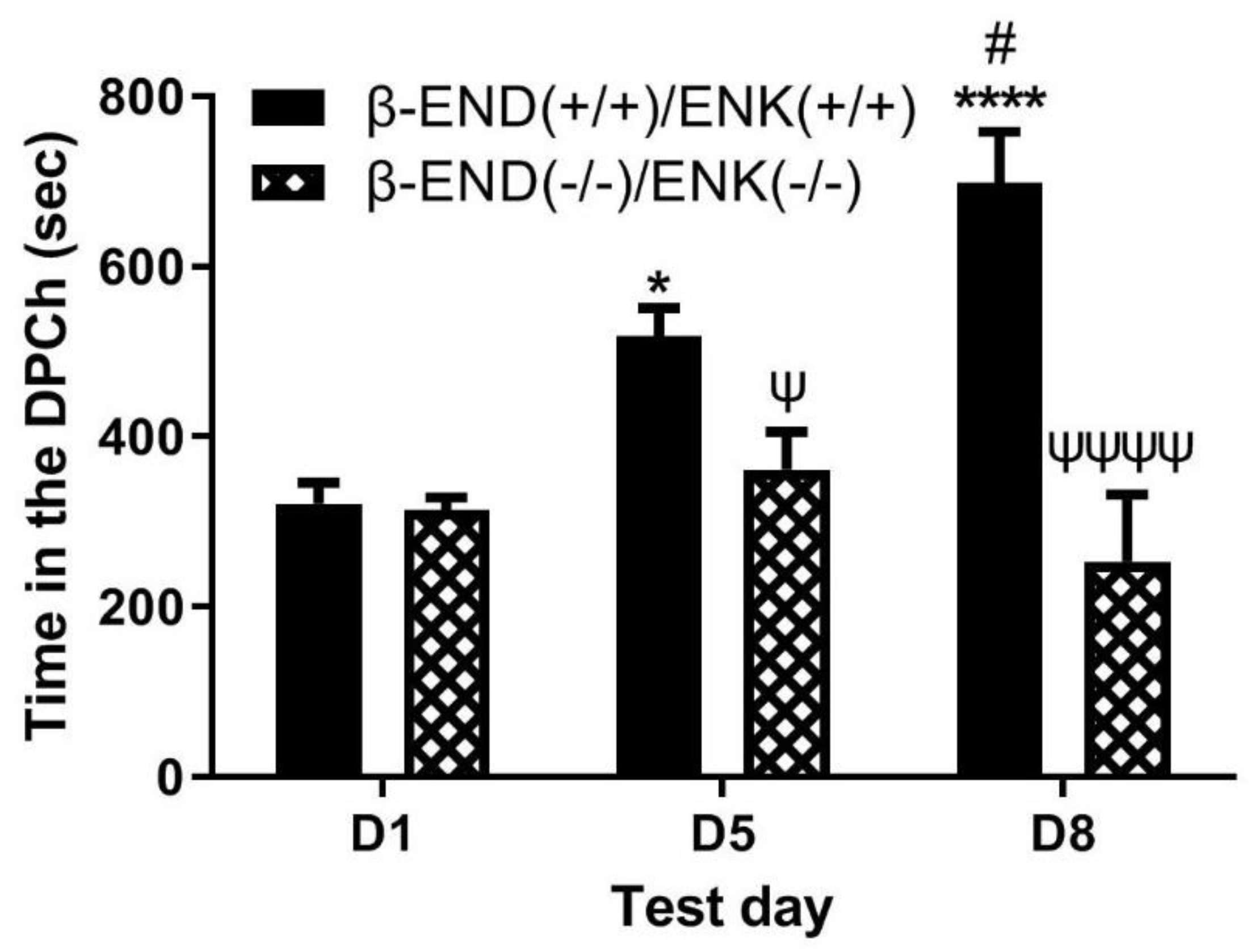

Experiment 3. We then evaluated which endogenous opioid peptides would be involved in the crosstalk between alcohol and morphine. We utilized mice lacking β-end and/or enkephalins and their wild-type controls. Mice were conditioned with ethanol, as described above. On day 8, they were challenged with morphine (5 mg/kg, s.c.) and immediately after were placed in the place conditioning apparatus. The amount of time that mice spent in each chamber was recorded for 15 min.

- Data

ata Analysis

Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) of the amount of time that mice of each genotype spent in the ethanol-paired chambers on preconditioning (D1) test day, following conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) (D5) and following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) (D8). Data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to reveal significant differences between groups and between test days. A p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

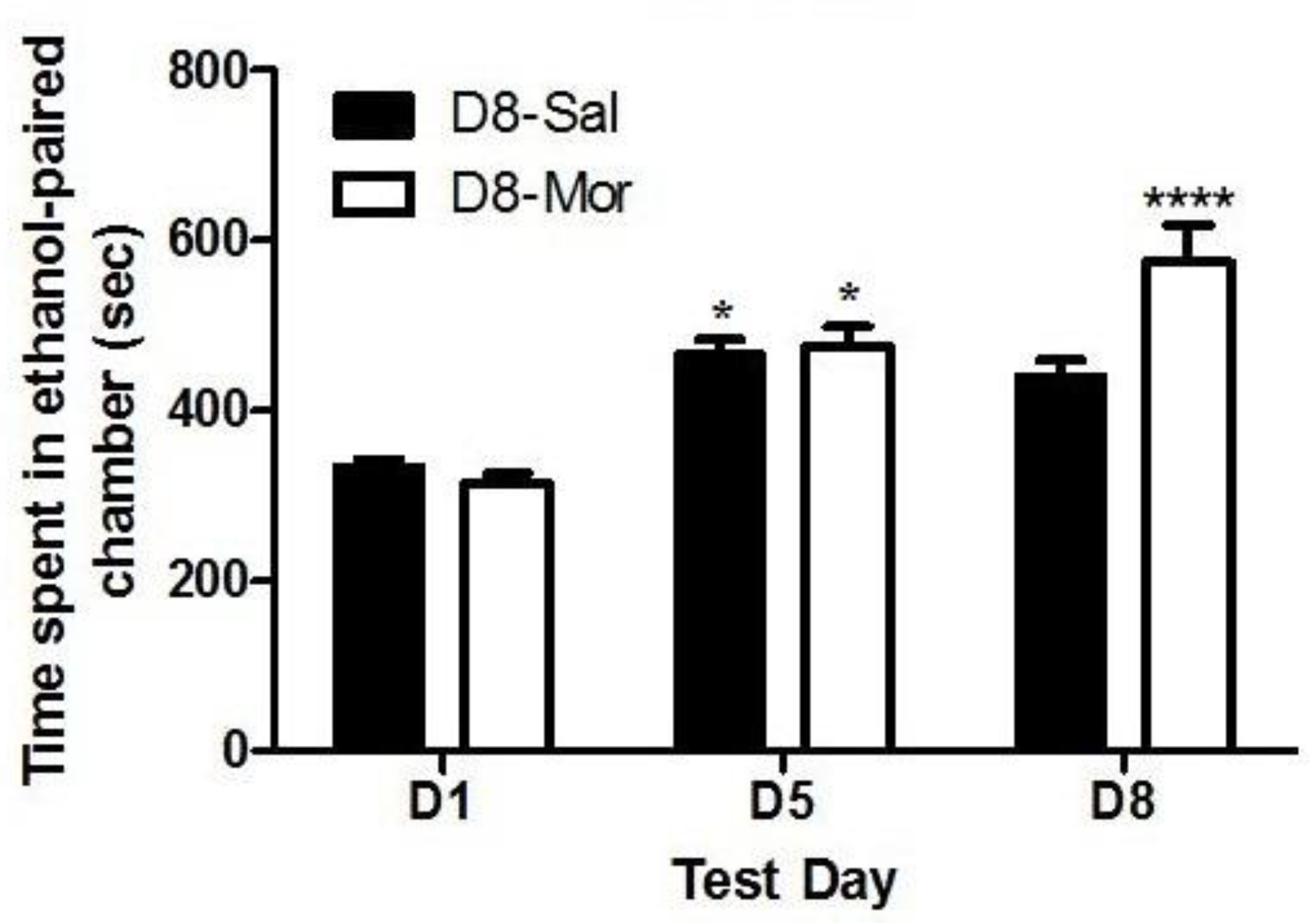

Figure 1 depicts the amount of time that C57BL/6J wild-type mice spent in the saline- and ethanol-paired chambers before (D1) and after (D5) conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) and following the saline or morphine (5 mg/kg) challenge given on day 8 (D8). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant effect of treatment (F(1,51) = 3.59, p>0.05), but there was a significant effect of test day (F(2,102) = 51.32, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction between the two factors (F(2,102) = 9.26, p<0.0005). Post-hoc analysis showed that mice spent significantly more time in the ethanol-paired chamber on the postconditioning test day (day 5, D5) than the preconditioning test day (day 1, D1), showing that both groups exhibited CPP. Animals challenged with saline on day 8 retained the CPP response. However, mice that were treated with morphine on day 8 spent a significantly greater amount of time in the ethanol-paired chamber than their saline-treated controls (p<0.0001). These results suggest that morphine potentiated the rewarding action of ethanol in wild-type mice (

Figure 1).

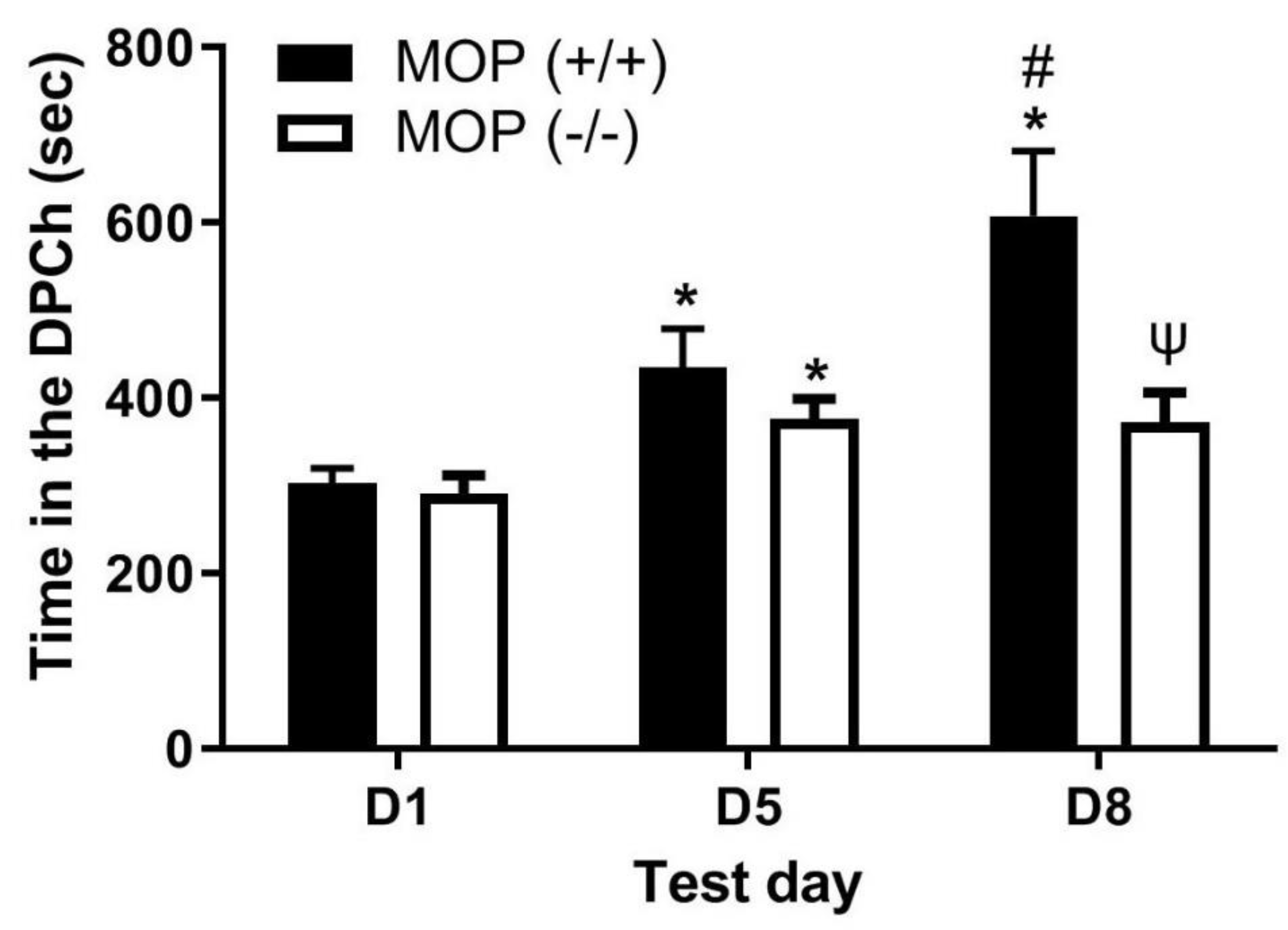

Figure 2 depicts the amount of time that mice lacking MOP and their wild-type littermates/controls spent in the ethanol-paired chambers before (D1) and after (D5) conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) and following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) given on day 8 (D8). Comparing the amount of time that mice of both genotypes spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on pre- and postconditioning test days revealed a significant effect of test day (F(1,29) = 57.88, p<0.0001) and a significant effect of genotype (F(1,29) = 5.21 (p<0.05), but there was no significant interaction between the two factors (F(1,29) = 1.91, p>0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that wild-type mice spent a significantly greater amount of time in the ethanol-paired chamber on day 8 compared to MOP null mice (p<0.05). These results suggest that, although ethanol induced CPP in both mice lacking MOP and their wild-type littermates/controls (

Figure 2, compare D1 vs. D5), the CPP response following a challenge dose of morphine was attenuated in MOP null mice (

Figure 2, compare the CPP response in mice of the two genotypes on D8). These findings suggest that the ability of morphine to enhance the magnitude of ethanol CPP was mediated via MOP.

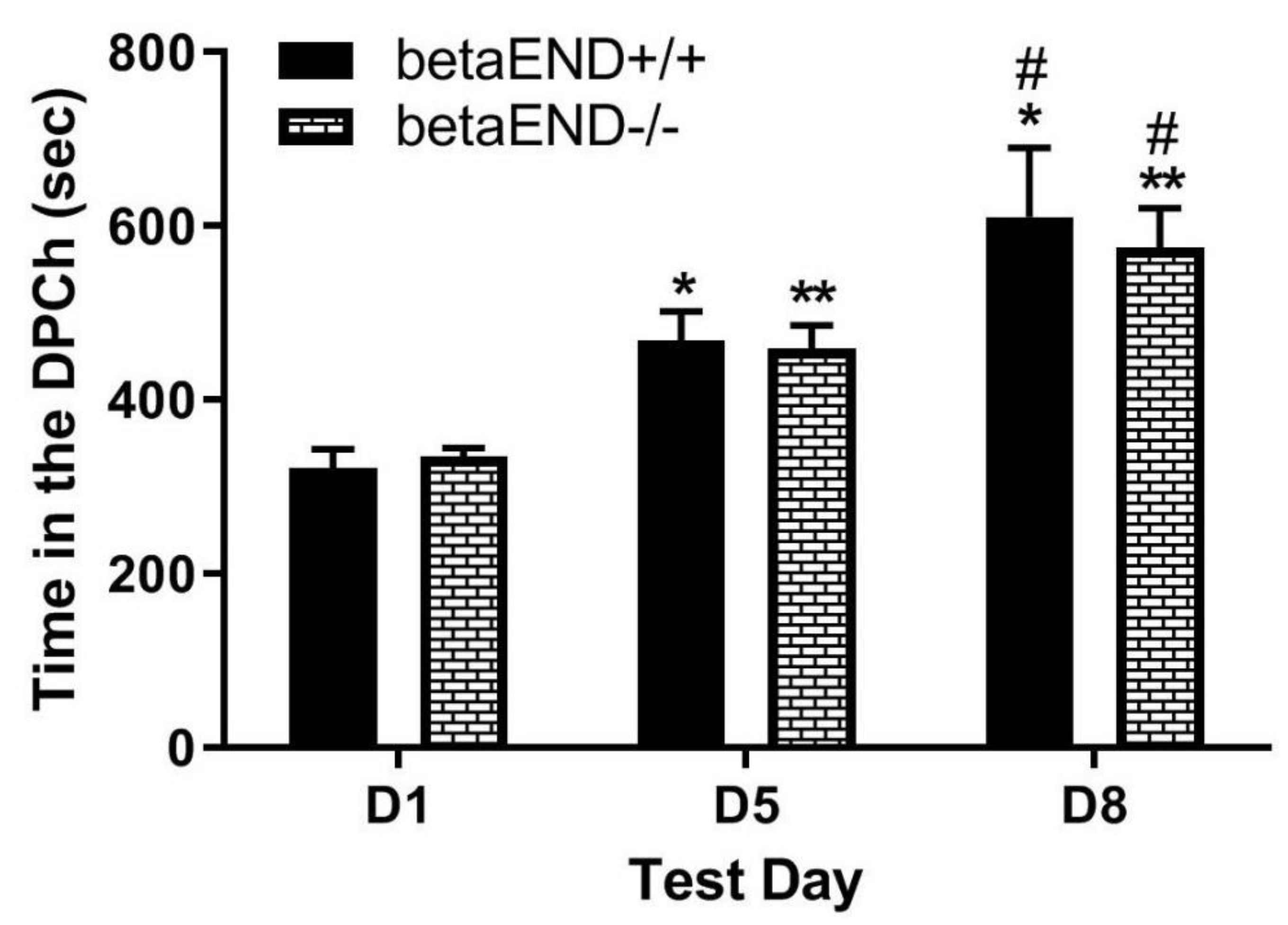

Figure 3 depicts the amount of time that mice lacking β-end spent in the ethanol-paired chambers before (D1) and after (D5) conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) and following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) given on day 8 (D8). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of test day (F(2,34) = 28.00, p<0.0001), a significant effect of treatment (F(1,17) = 9.55, p<0.01) and a significant interaction between the two factors (F(2,34) = 8.65, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no difference in the amount of time that mice from each group spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on the preconditioning (D1) and postconditioning (D5) test days (p>0.05). Likewise, mice of both genotypes showed a comparable CPP response following the challenge dose of morphine on day 8 (

Figure 3, D1 vs. D8 for the mice of each genotype). These results suggest that the ability of morphine to potentiate ethanol CPP was not altered in the absence of β-end.

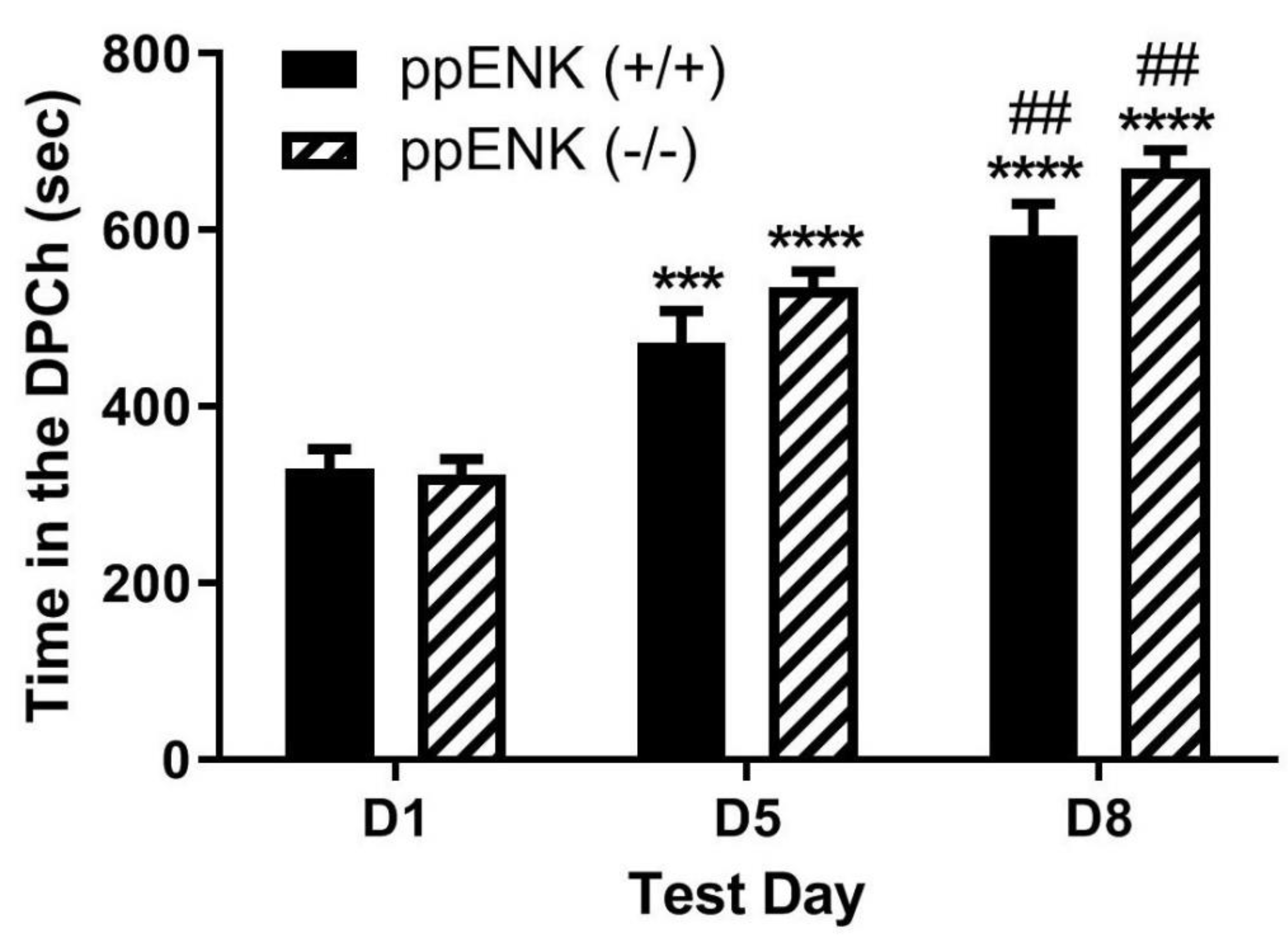

Figure 4 depicts the amount of time that mice lacking enkephalins spent in the ethanol-paired chambers before (D1) and after (D5) conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) and following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) given on day 8 (D8). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of test day (F(1,39) = 57.68, p<0.0001), but there was no significant effect of genotype (F(1,39) = 0.02, p>0.05) and no significant interaction between the two factors (F(1,39) = 0.37, p>0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no difference in the amount of time that mice lacking enkephalins spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on the preconditioning test day (p>0.05) compared to wild-type controls. In addition, there was no difference between genotypes in the amount of time spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on the postconditioning test day (p>0.05) (

Figure 4, D1 vs. D5). Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no difference in the amount of time that mice lacking enkephalins and the wild-type controls spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on day 8 (

Figure 4, D1 vs. D8). These results suggest that the ability of morphine to potentiate ethanol CPP was not altered in the absence of enkephalins.

Figure 5 depicts the amount of time that mice lacking β-end and enkephalins spent in the ethanol-paired chambers before (D1) and after (D5) conditioning with ethanol (2 g/kg) and following a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) given on day 8 (D8). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of test day (F(1,36) = 45.65, p<0.0001) and a significant effect of genotype (F(1,36) = 4.16, p<0.05), but there was no significant interaction between the two factors (F(1,36) = 1.37, p>0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no difference in the time that mice lacking β-end and enkephalins spent in the ethanol-paired chamber on the preconditioning test day (p>0.05) compared to wild-type controls. However, wild-type mice spent a significantly greater amount of time in the ethanol-paired chamber on the postconditioning test day compared to the double knockout mice (p<0.05) (

Figure 5, D1 vs. D5). These results confirm those previously shown that the rewarding action of ethanol was reduced in mice lacking β-end and enkephalins compared to wild-type mice. Post-hoc analysis also showed that wild-type controls spent a significantly greater amount of time in the ethanol-paired chamber on day 8 (p>0.05) than the double knockout mice (

Figure 5, compare mice of the two genotypes on D8). These results suggest that the ability of morphine to potentiate the CPP response was abolished in the absence of both β-end and enkephalins.

4. Discussion

A The main finding of the present study is that there was a crosstalk between the rewarding action of morphine and ethanol, as a challenge dose of morphine enhanced the CPP response in mice conditioned with ethanol. This was blunted in mice lacking the MOP, confirming that the response is mediated via the MOP. While the enhancement was not altered in mice lacking β-endorphin or enkephalins alone, it was completely abolished in mice lacking both β-end and enkephalins. Together, these results suggest that the joint action of these opioid peptides on ethanol reward plays a critical role in the crosstalk between morphine and ethanol.

The prevalence of multiple substance abuse, in particular involving alcohol and opiates, gives reason to look into the mechanisms underlying their combined use. Alcohol and morphine produce many similar effects, such as euphoria, and also have overlapping mechanisms of action. Morphine mimics the action of endogenous opioids by binding to the MOP. Alcohol, on the other hand, stimulates the release of endogenous opioid peptides, such as β-end and enkephalins, in turn activating opioid receptors. Morphine has been shown to suppress ethanol withdrawal-induced convulsions in mice [

31], while sensitization to morphine developed in mice that were habituated to alcohol [

32]. These studies suggest there is a crosstalk between morphine’s and alcohol’s effects. A correlation has also been observed between morphine and alcohol consumption, as small doses of morphine have been shown to increase subsequent intake of ethanol in rats [

24]. However, the ability of morphine to alter alcohol reward has not been fully explored. Therefore, we used the place conditioning paradigm to assess whether morphine would alter ethanol-induced CPP.

Animals were conditioned with ethanol (2 g/kg), tested for postconditioning CPP on day 5 and then received a challenge dose of morphine (5 mg/kg) on day 8. We found that ethanol conditioning induced a robust CPP in wild-type mice of all genotypes and a subsequent morphine challenge potentiated the CPP response in these mice. These results are in agreement with previous studies showing that pretreatment with morphine following ethanol-induced CPP leads to persistent expression of the CPP response [

33].

Previous studies have assessed the interaction between ethanol and opioids. For example, morphine-induced CPP was potentiated in mice given a liquid diet containing ethanol, supporting an interaction between alcohol and opioid effects [

34]. Furthermore, binge-like exposure to ethanol upregulated MOP expression in the striatum and nucleus accumbens, leading to an increase in the antinociceptive response to morphine [

35]. Given the action of morphine is mediated via MOP, we also examined the role of MOP in the crosstalk between morphine and ethanol reward. We observed that MOP wild-type mice conditioned with ethanol and challenged with morphine exhibited a greater CPP response, and this response was absent in mice lacking MOP, suggesting that the crosstalk between morphine and alcohol reward is dependent on a common mechanism in the CNS, which most likely involves activation of MOP. Ethanol exposure not only alters the release of endogenous opioid peptides, but also opioid receptor expression along mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons [

36,

37]. Thus, upregulation of MOP following alcohol exposure may lead to a sensitized endogenous opioid system, permitting enhanced opioid receptor binding. This in turn would facilitate the effect of a subsequent morphine challenge, thereby leading to a greater CPP response. Alternatively, given that both alcohol and morphine alter dopamine release, it is possible that the enhancement of reward is due to a sensitized dopamine system. For example, voluntary ethanol consumption increased the number of spontaneously-firing dopamine neurons in the VTA, which would lead to an excitatory effect on dopamine release [

38].

Given that β-end and enkephalins bind to MOP and that opioid peptides are released following ethanol exposure [

9,

10], we hypothesized that the ability of morphine to enhance the rewarding action of ethanol might be due to the release of endogenous opioid peptides during ethanol conditioning, and therefore this response would be altered in the absence of β-end or enkephalins. However, we discovered that mice lacking either β-end or enkephalins exhibited a comparable CPP response compared to wild-type controls following ethanol conditioning as well as in response to the morphine challenge. Because we had previously observed reduced ethanol CPP in mice lacking both peptides [

23], suggesting that one peptide might compensate for the other, we then examined whether morphine-induced potentiation of ethanol CPP would be altered in mice lacking both β-end and enkephalins. Our results showed that morphine was able to enhance the rewarding action of ethanol in wild-type mice. However, the crosstalk was absent in mice lacking both β-end and enkephalins, suggesting both β-end and enkephalins are needed for the development of crosstalk between ethanol and morphine. We propose that the release of endogenous opioid peptides by ethanol [

6,

7,

8,

39,

40] may induce a sensitized response, thereby leading to enhanced CPP following the morphine challenge in mice showing CPP following the morphine conditioning. However, further studies are needed to delineate the underlying mechanisms of such crosstalk.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we observed that morphine potentiated the rewarding properties of ethanol and this effect was blocked in MOP null mice as well as in mice lacking both β-end and enkephalins. Thus, it appears that the crosstalk between morphine’s and alcohol’s effects are due to an interaction in their mechanisms of action, possibly activation of MOP by ethanol-induced release of opioid peptides, leading to a functionally sensitized system to exogenous opioids. Further studies are needed to test the latter possibility. Interestingly, chronic ethanol drinking has been shown to produce tolerance to morphine’s analgesic effects by preventing MOP endocytosis [

41]. Thus, these findings may have important implications, especially in alcoholics needing morphine for pain relief. Since cross-tolerance to the analgesic effects and cross-sensitization to the rewarding effects of ethanol and morphine occur, consideration needs to be given when pain therapy is necessary in these patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.; methodology, A.T., A.H.; software, A.T., K.L.; validation, A.T. and K.L.; formal analysis, A.T. and K.L; investigation, A.T.; resources, K.L.; data curation, A.T. and K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.; writing—review and editing, A.T. and K.L.; supervision, K.L.; project administration, K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. A.T. was supported by the Department of Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Sciences while conducting these studies as part of his thesis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Western University of Health Sciences (Pomona, CA, USA).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Sciences, the College, and University for their continued support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Altshuler, H.L., P.E. Phillips, and D.A. Feinhandler, Alteration of ethanol self-administration by naltrexone. Life Sci, 1980. 26(9): p. 679-88. [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.C., et al., Naloxone attenuates voluntary ethanol intake in rats selectively bred for high ethanol preference. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 1990. 35(2): p. 385-90. [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, S.S., et al., Naltrexone decreases craving and alcohol self-administration in alcohol-dependent subjects and activates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2002. 160(1): p. 19-29. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, J.R., et al., Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1992. 49(11): p. 876-80. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. and M.J. Kreek, Clinically utilized kappa-opioid receptor agonist nalfurafine combined with low-dose naltrexone prevents alcohol relapse-like drinking in male and female mice. Brain Res, 2019. 1724: p. 146410. [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.P., et al., Effects of acute ethanol on opioid peptide release in the central amygdala: an in vivo microdialysis study. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2008. 201(2): p. 261-71. [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.P., et al., Effects of acute ethanol on beta-endorphin release in the nucleus accumbens of selectively bred lines of alcohol-preferring AA and alcohol-avoiding ANA rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2010. 208(1): p. 121-30. [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, P.W., et al., A microdialysis profile of Met-enkephalin release in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2005. 29(10): p. 1821-8. [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, P.W., R. Quirion, and C. Gianoulakis, A microdialysis profile of beta-endorphin and catecholamines in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2003. 169(1): p. 60-7. [CrossRef]

- Olive, M.F., et al., Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci, 2001. 21(23): p. RC184. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W., T.K. Li, and J.C. Froehlich, Enhanced sensitivity of the nucleus accumbens proenkephalin system to alcohol in rats selectively bred for alcohol preference. Brain Res, 1998. 794(1): p. 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Zale, E.L., S.A. Maisto, and J.W. Ditre, Interrelations between pain and alcohol: An integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev, 2015. 37: p. 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Esser, M.B., et al., Binge Drinking and Prescription Opioid Misuse in the U.S., 2012-2014. Am J Prev Med, 2019. 57(2): p. 197-208. [CrossRef]

- Boissoneault, J., B. Lewis, and S.J. Nixon, Characterizing chronic pain and alcohol use trajectory among treatment-seeking alcoholics. Alcohol, 2019. 75: p. 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E., et al., Longitudinal associations between pain and substance use disorder treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2022. 143: p. 108892. [CrossRef]

- Weathermon, R. and D.W. Crabb, Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol Res Health, 1999. 23(1): p. 40-54.

- Ruttenber, A.J., H.D. Kalter, and P. Santinga, The role of ethanol abuse in the etiology of heroin-related death. J Forensic Sci, 1990. 35(4): p. 891-900. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M., L.J. Paulozzi, and K.A. Mack, Alcohol involvement in opioid pain reliever and benzodiazepine drug abuse-related emergency department visits and drug-related deaths - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2014. 63(40): p. 881-5. [CrossRef]

- Hood, L.E., J.M. Leyrer-Jackson, and M.F. Olive, Pharmacotherapeutic management of co-morbid alcohol and opioid use. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2020. 21(7): p. 823-839. [CrossRef]

- Fidecka, S., et al., The development of cross tolerance between ethanol and morphine. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm, 1986. 38(3): p. 277-84.

- Reid, L.D. and G.A. Hunter, Morphine and naloxone modulate intake of ethanol. Alcohol, 1984. 1(1): p. 33-7. [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, M.M., et al., Elevated customary alcohol consumption attenuates opioid effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 2021. 211: p. 173295. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, A., et al., The role of endogenous beta-endorphin and enkephalins in ethanol reward. Neuropharmacology, 2013. 73: p. 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, C.L., et al., Consumption of ethanol solution is potentiated by morphine and attenuated by naloxone persistently across repeated daily administrations. Alcohol, 1986. 3(1): p. 39-54. [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.S., et al., Opioids and consummatory behavior. Brain Res Bull, 1985. 14(6): p. 663-72. [CrossRef]

- Bardo, M.T. and R.A. Bevins, Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2000. 153(1): p. 31-43.

- Nguyen, K., et al., The role of endogenous dynorphin in ethanol-induced state-dependent CPP. Behav Brain Res, 2012. 227(1): p. 58-63. [CrossRef]

- Matthes, H.W., et al., Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature, 1996. 383(6603): p. 819-23.

- Rubinstein, M., et al., Absence of opioid stress-induced analgesia in mice lacking beta-endorphin by site-directed mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1996. 93(9): p. 3995-4000. [CrossRef]

- Konig, M., et al., Pain responses, anxiety and aggression in mice deficient in pre-proenkephalin. Nature, 1996. 383(6600): p. 535-8. [CrossRef]

- Blum, K., et al., Morphine suppression of ethanol withdrawal in mice. Experientia, 1976. 32(1): p. 79-82. [CrossRef]

- Venho, I., et al., Sensitisation to morphine by experimentally induced alcoholism in white mice. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn, 1955. 33(3): p. 249-52.

- Cunningham, C.L., et al., Morphine and ethanol pretreatment effects on expression and extinction of ethanol-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2021. 238(1): p. 55-66. [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, M., et al., Effect of chronic ethanol treatment on μ-opioid receptor function, interacting proteins and morphine-induced place preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2013. 228(2): p. 207-15. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.L., et al., Binge-Like Exposure to Ethanol Enhances Morphine’s Anti-nociception in B6 Mice. Front Psychiatry, 2018. 9: p. 756. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M., M. Leriche, and J.C. Calva, Acute ethanol administration differentially modulates mu opioid receptors in the rat meso-accumbens and mesocortical pathways. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 2001. 94(1-2): p. 148-56. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, M.S., et al., Ethanol consumption by Fawn-Hooded rats following abstinence: effect of naltrexone and changes in mu-opioid receptor density. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 1999. 23(6): p. 1008-14. [CrossRef]

- Morzorati, S.L., R.L. Marunde, and D. Downey, Limited access to ethanol increases the number of spontaneously active dopamine neurons in the posterior ventral tegmental area of nondependent P rats. Alcohol, 2010. 44(3): p. 257-64. [CrossRef]

- Jarjour, S., L. Bai, and C. Gianoulakis, Effect of acute ethanol administration on the release of opioid peptides from the midbrain including the ventral tegmental area. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2009. 33(6): p. 1033-43. [CrossRef]

- Kalivas, P.W. and R. Abhold, Enkephalin release into the ventral tegmental area in response to stress: modulation of mesocorticolimbic dopamine. Brain Res, 1987. 414(2): p. 339-48. [CrossRef]

- He, L. and J.L. Whistler, Chronic ethanol consumption in rats produces opioid antinociceptive tolerance through inhibition of mu opioid receptor endocytosis. PLoS ONE, 2008. 6(5): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).