Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Background and Rational

2.1. Online Privacy

2.2. Online Anonymity

2.3. Anonymous Communication Networks

2.3.1. About TOR

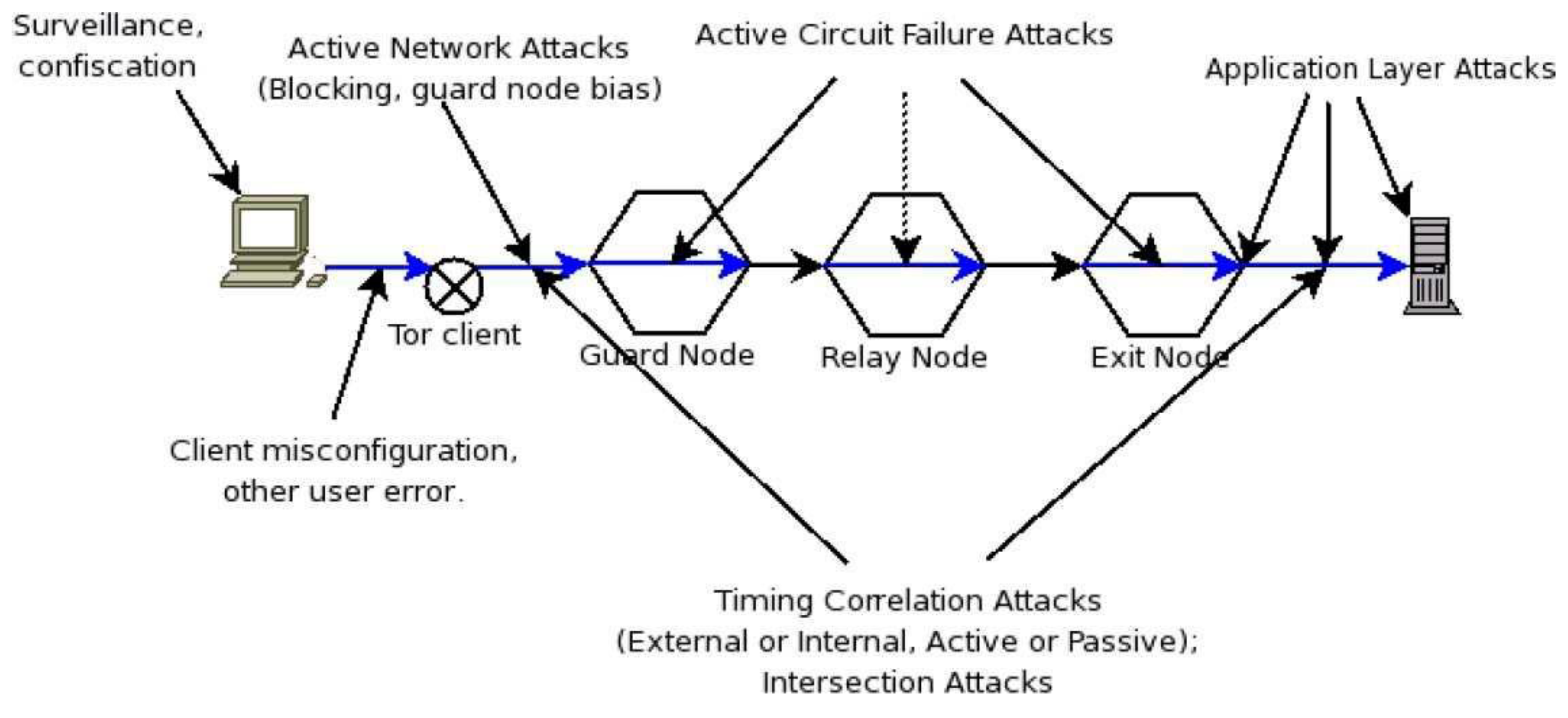

- -

- As TOR is relying on an aging (componential breakable) encryption and integrity mechanisms for which global adversaries are or will soon be able and capable of compromising. Thus, the existing pretended cryptology guarantee such as onion construction (wrapping ciphers), keys exchange protocols and the integrity and authentication checks mechanisms should be reviewed.

- -

- The delays caused by the congestion on the network and also by the heavyweight encryption and decryption.

- -

- The identification of TOR user through internet and traffic analysis which leads usually to linking several intercepted communication to involved parties or linking multiple communications to a single user (Nia et al., 2014).

2.3.2. Path Selection Attacks

3. Methodology and Proposed Improvements and Enhancements

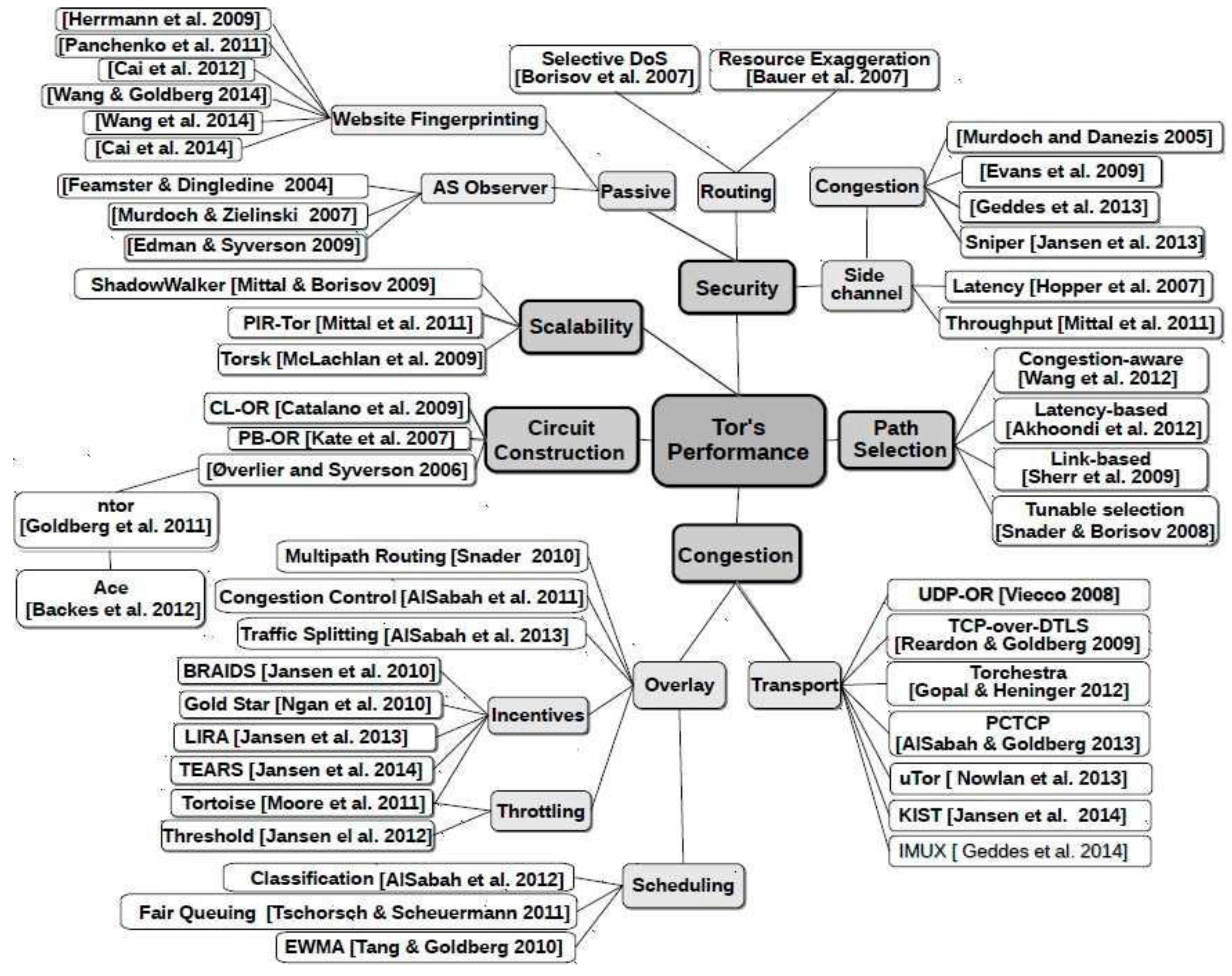

3.1. Related Improving Research

3.2. Problem Tackled During This Works

- a)

- Cryptographic and performance enhancement

- b)

- Circuit selection security

- c)

- Sessions’ and Users’ Un-linkability

- d)

- Network Confusion and Diffusion

- e)

- Node-to-Node cells’ authentication

3.3. Proposed Improvements and Enhancements

3.3.1. Multi-Layer Encryption Improvement

- -

- OCB eliminate the problem of authenticated-encryption with associated-data (AEAD),

- -

- The OCB nonce required to encrypt and decrypt should not be necessary random as it utelise a counter,

- -

- OCB can encrypt data of any size without padding it to any convenient-length and therefore save some precious computing power.

- a)

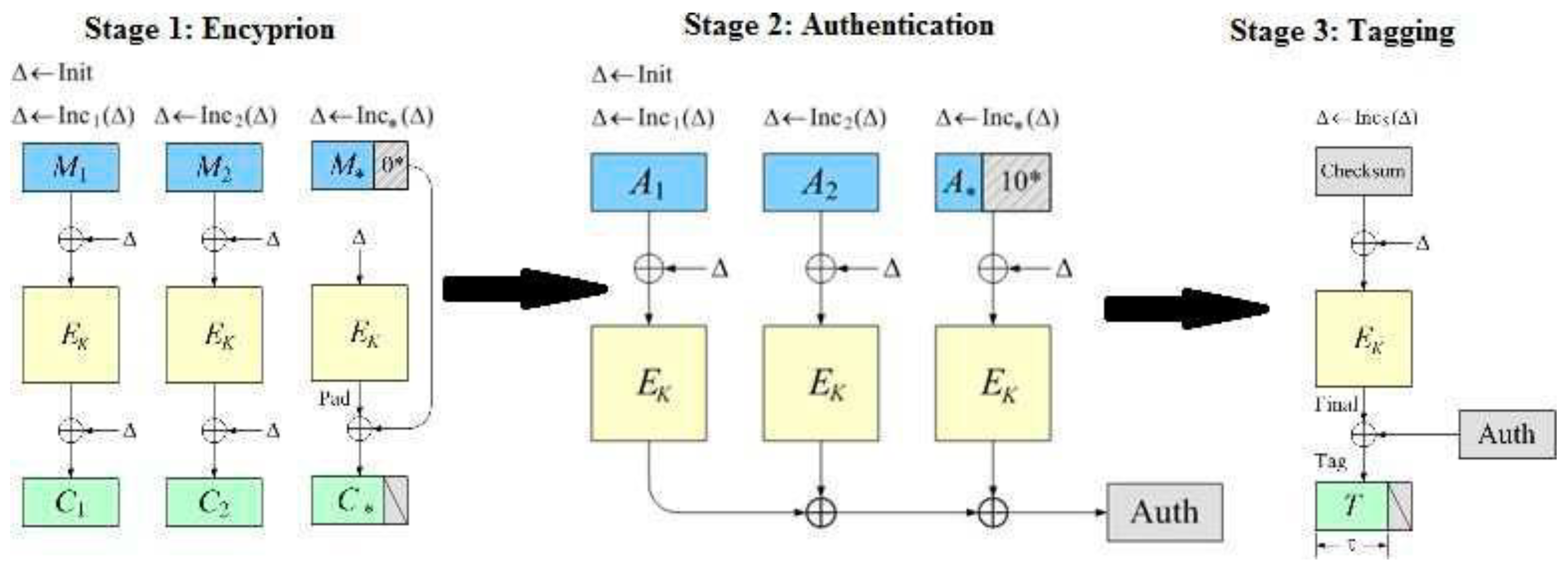

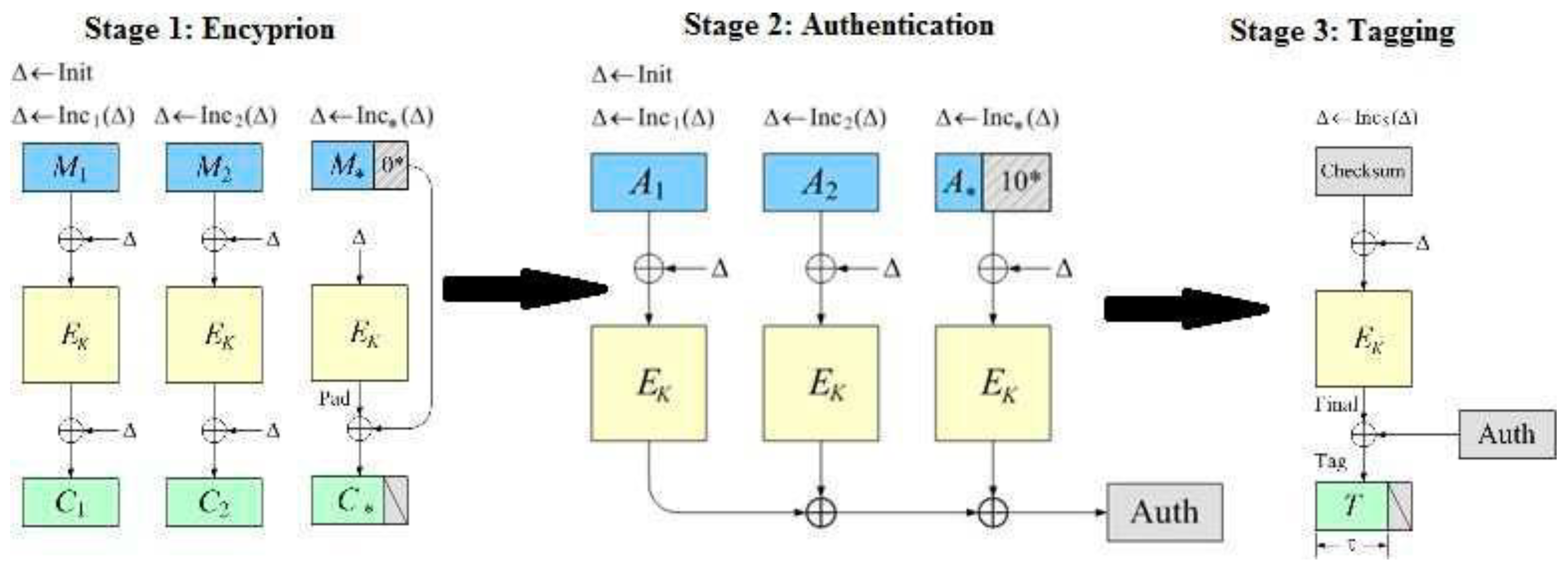

- Working principle of the OCB mode

- -

- First the plaintext M is divided into blocks of 128 bits each M = M1 ... Mm, Here there is two cases; the data size in bit is a multiple of 128, or there is a remainder and therefore the algorithm require a padding.

- -

- Secondly, a Checksum of 128 bits is calculated Checksum = M1 ⊕…⊕ Mm and will be used later during the authentication process.

- -

- Thirdly, an initialisation function “Init” take place and using the nonce N which is concatenated with a 32 bits constant value to produce a 128 bits value called “Top”. Later, the Ktop = EK (Top) is computed and Stretched to produce the 256 bits value Stretch = Ktop || (Ktop⊕(Ktop<<8)) (left shift by 8 positions KTop and replace the empty by zeros). The value Init(N) which is the initial value for Δ.

- -

- Fourthly, for each block “i” the increment is called to increment the Δ, XOR with the Mi, and encrypted using the key K and the algorithm AES-OCB as showed in the scheme. Later, the output of the encryption in stage 4 is XOR again with the Δ to produce Ci... The authenticated ciphertext is CT = C1 C2 … Cm T.

- -

- Fully parallelizable operations of the block ciphering can be performed simultaneously. Thus, OCB is very efficient and suitable for hardware encrypting at high network speeds.

- -

- Block-ciphering scheme make it strong and resist better to the new timing attacks which the other mode like CBC would be vulnerable.

- -

- OCB is a single key scheme as it use the same key for encryption and authentication which make it more efficient in term of memory use.

- -

- OCB can process any data size without requiring it to be a multiple of the block length. Moreover, no external padding function is used and thus it economise time as there is no bits- waste in the ciphertext due to padding.

- -

- The main computational function used beyond the block-ciphering is XOR which is very time and power efficient function (three 128 bits XOR per block).

- -

- OCB can be perfectly used into memory-limited systems as the main memory cost the amount needed to hold the AES sub-keys.

- b)

- Choice justification

- c)

-

Cryptographic features comparison against competitorsTo evaluate the features of each candidate in addition to the practical performances, this work rely on the following points to determine the suitability of the authenticated encryption mode, the features are summarised in the following table and divided into three major part:

| Feature | CCM | GCM | OCB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Proved | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Online ability | No | Yes | Yes |

|

Key requirement |

128 bits block size |

128 or 64 bits block size |

128 or 64 bits block size |

- -

- Provably secure: all the three modes are proved to be mathematically secure by assuming that the used with block cipher (AES) is pseudorandom permutation. As far as the cryptography permit, AES is proved secure and thus both three modes of implementation are absolutely secure.

- -

- Online message processing: this feature is crucial for the suitability of the mode as the modes should be able to process data without knowing the whole length in advance as the TOR have no pre-set or pre-defined data length. Moreover, this feature is highly desired for a memory restricted environment which is the case of ORs in this part, CCM mode fail to achieve the set baselines.

- -

- Cipher requirements: CCM mode is developed to only work with ciphers using block size of 128 bits, while GCM and OCB can work with cipher using different block size (64/128 bits).

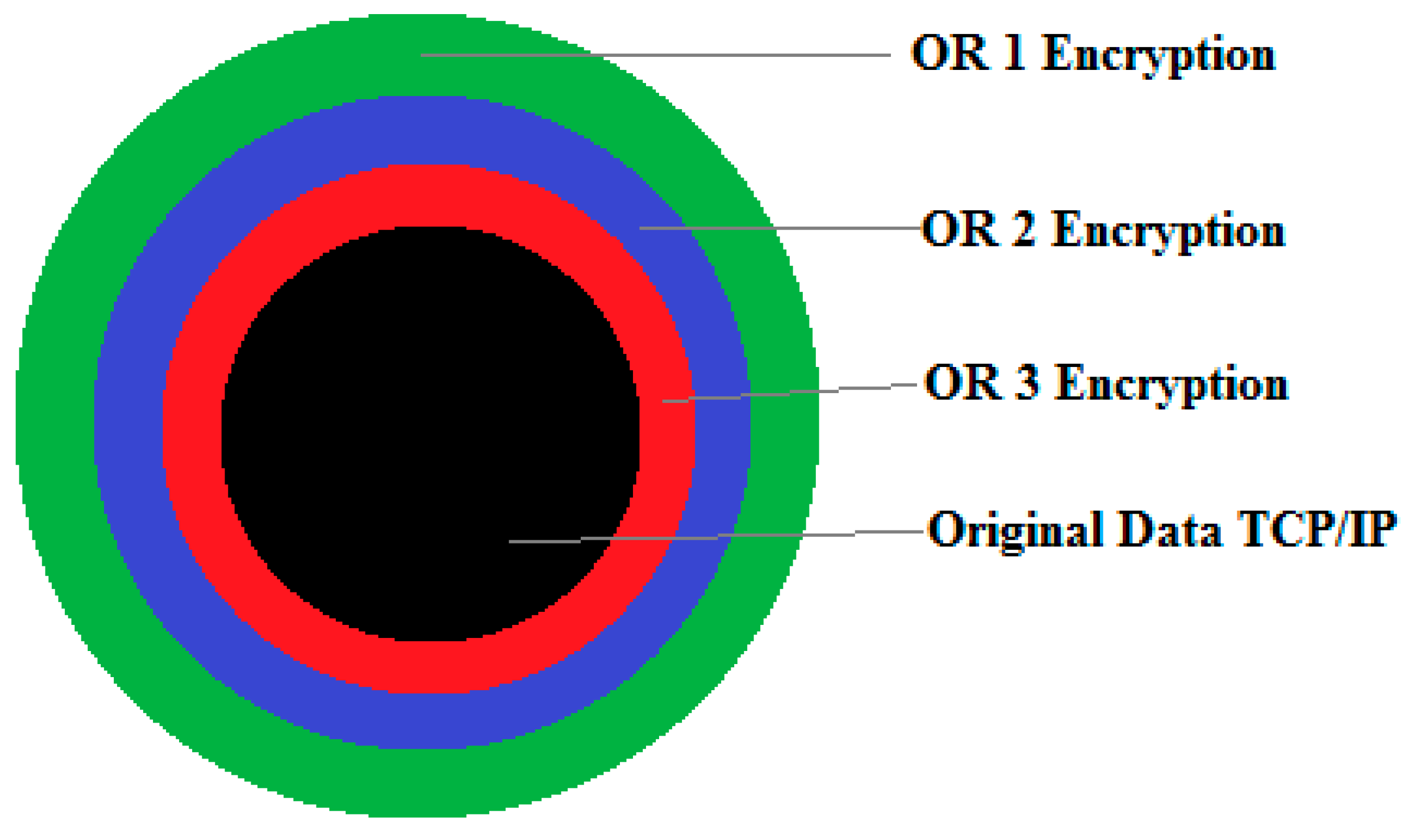

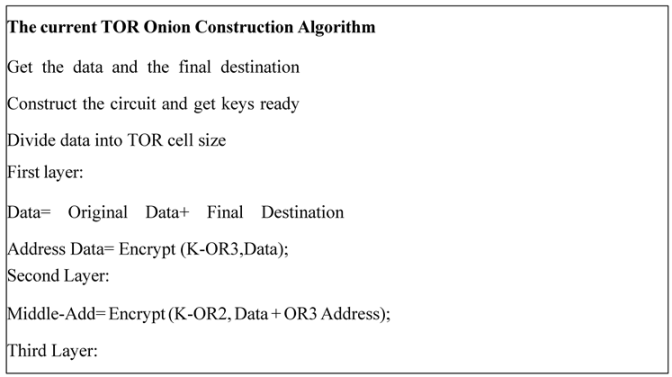

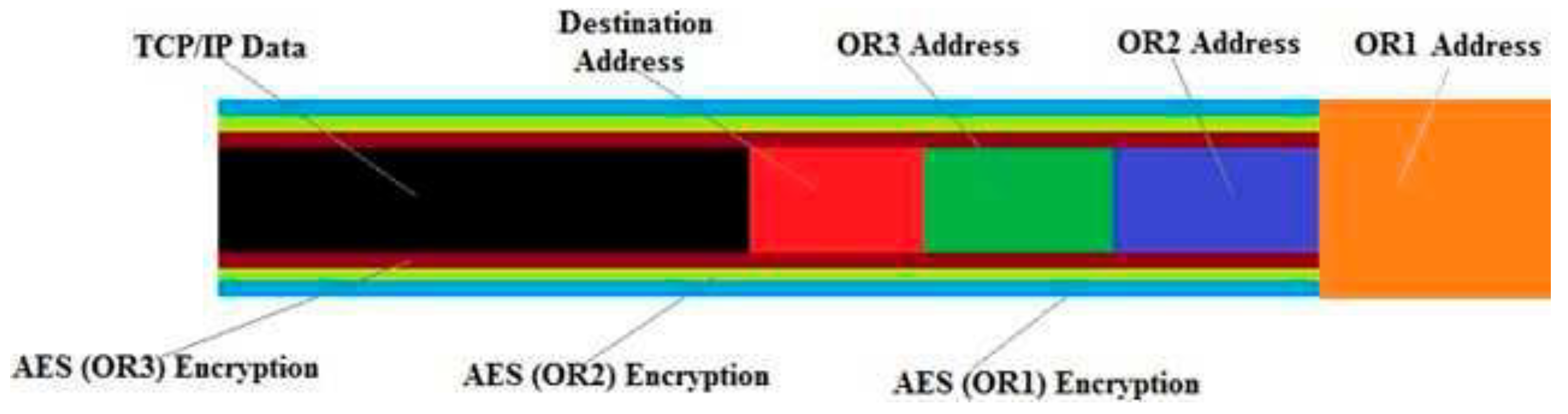

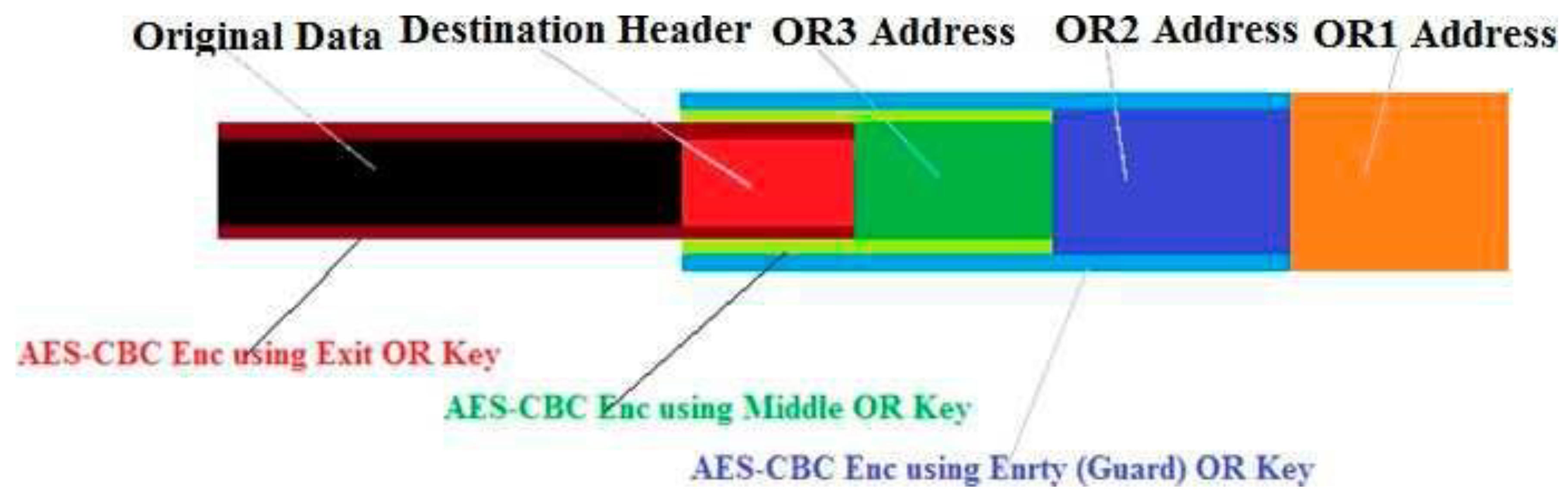

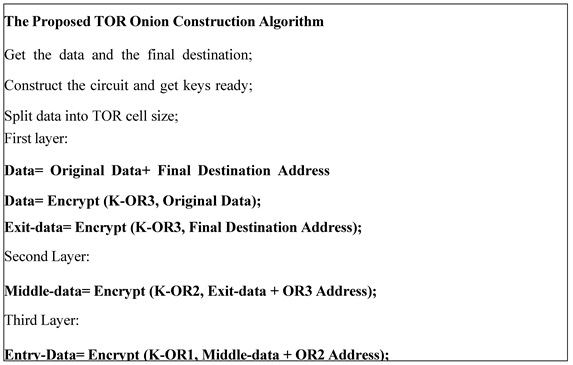

3.3.2. The Encapsulation Approach (Onion Wrapping Method)

- d)

- Proposed Improvement:

3.3.3. The Number of Intermediate ORs

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

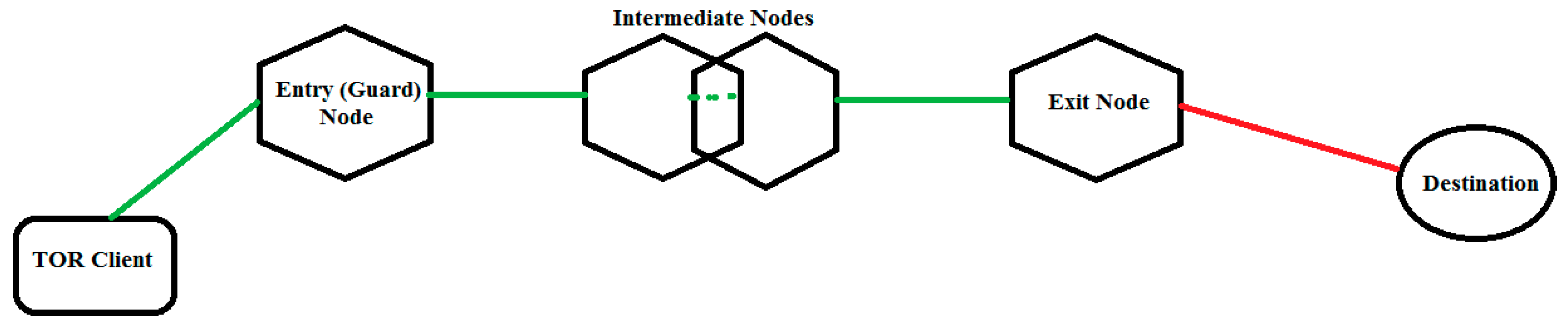

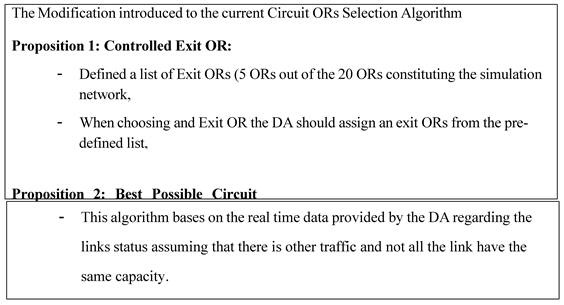

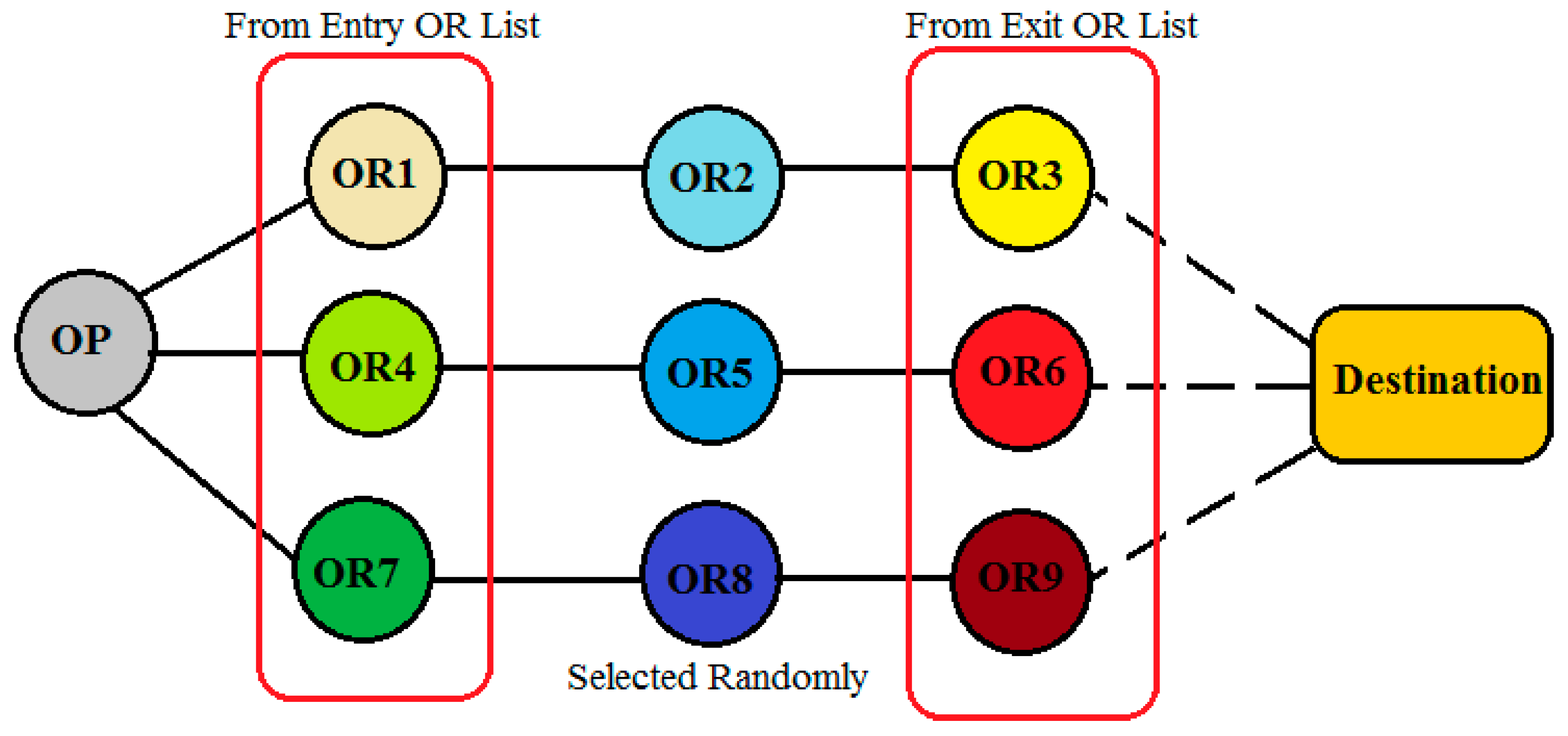

3.3.4. Circuit ORs’ Selection Approach

- -

- No OR should be used in the same circuit more than once,

- -

- ORs in the same circuit should belong to different class of TOR network,

- -

- A special treatment for co-administered ORs is introduced by marking them as the same family,

- -

- Directory Authorities will assign flags to ORs basing on the following parameters: performances, status, position and role.

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

- b)

- Dynamic circuit construction with traffic management

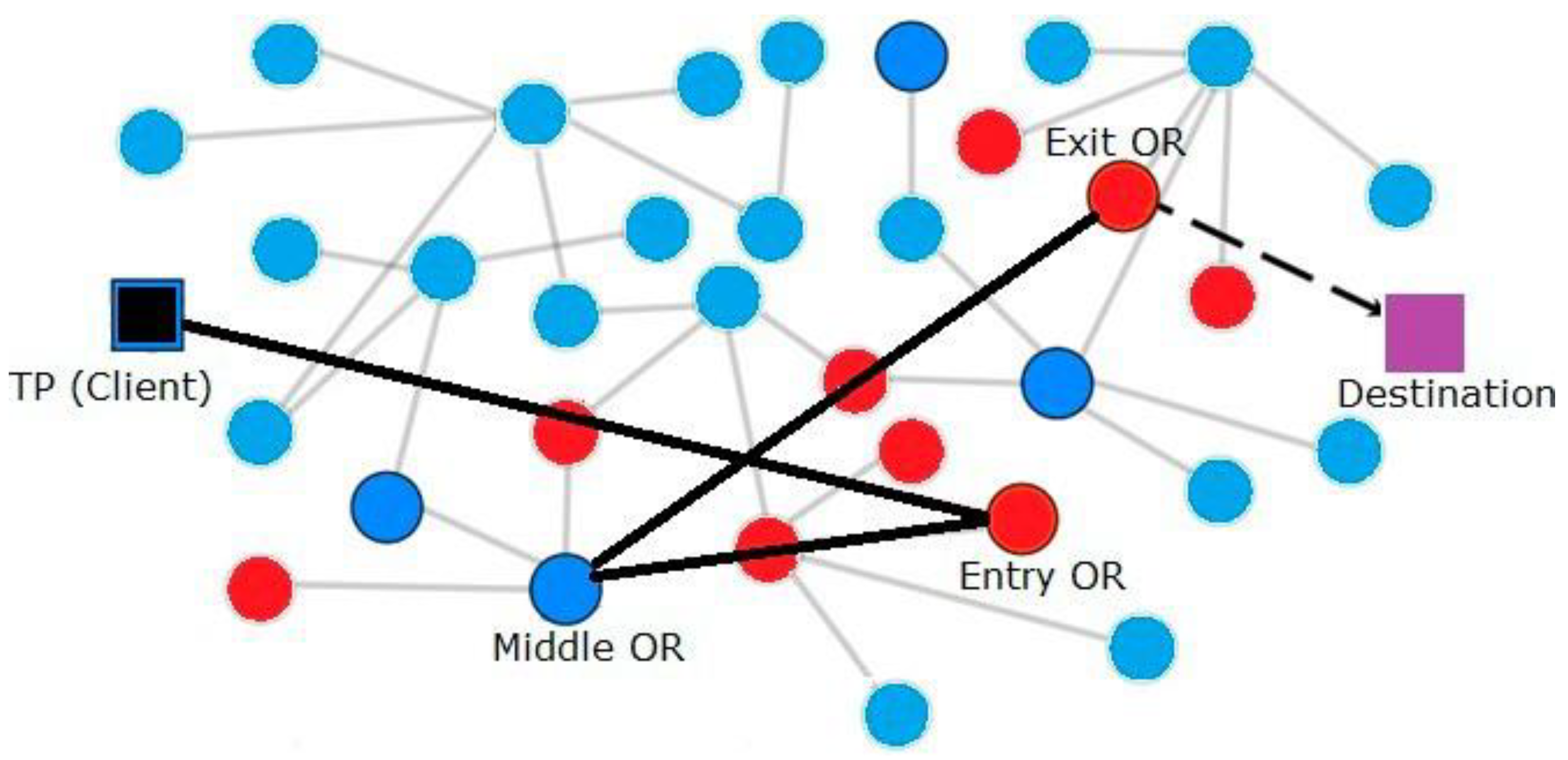

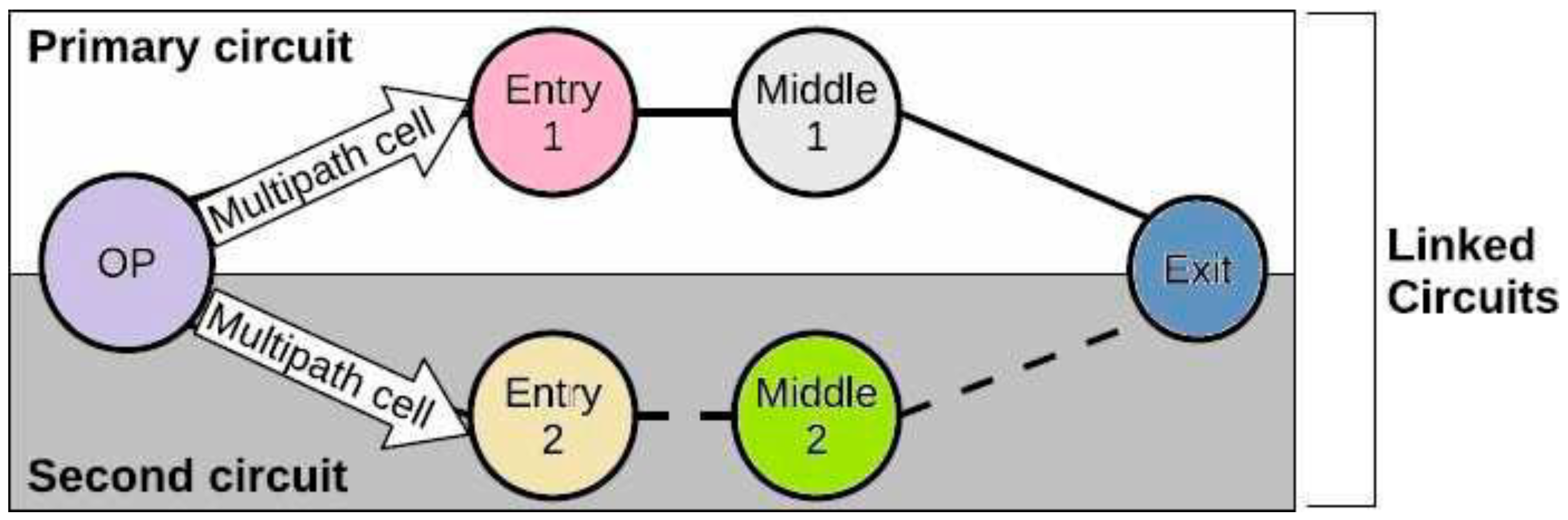

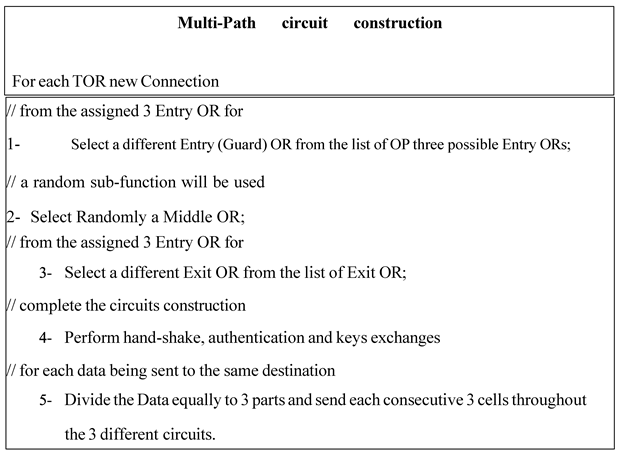

3.3.5. Cells’ Multi-Circuit Routing (Limited to Three Circuits)

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

5. Implementation, Testing and Results

5.1. Simulation Test-Beds Design and Adoption

- -

- Implementing, testing and comparing the obtained results of AES-OCB, AES-GCM and AES-CCM,

- -

- Implementing the proposed Wrapping approach (multi-layered encapsulation), testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Implementing the two variant of Circuit construction algorithms, testing and comparing the results,

- -

- Implementing the variable circuit length algorithm, testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Implementing the Multi-path Cell routing algorithm, testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Validation of the results and discussion.

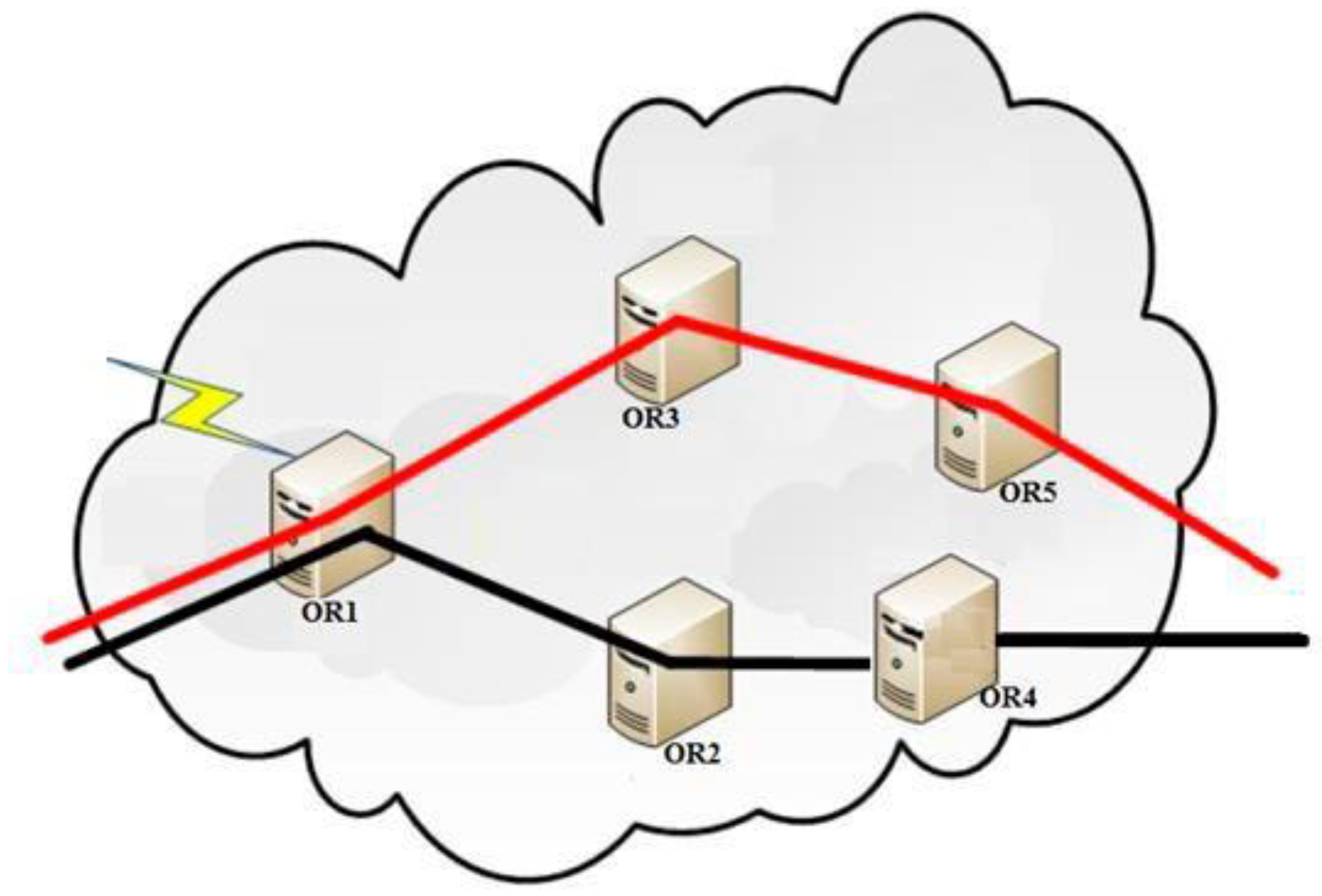

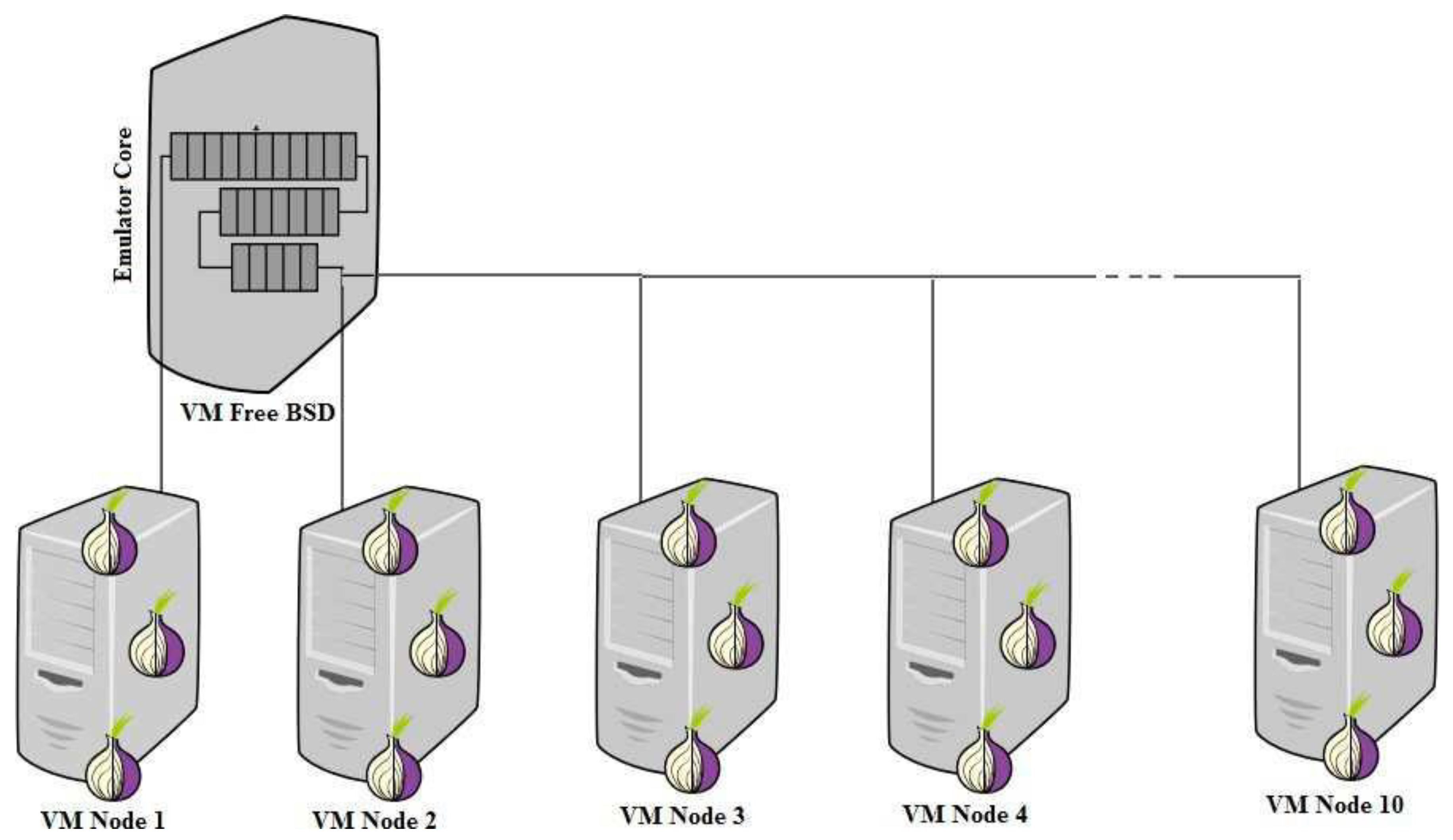

5.2. ExperimenTOR Platform

5.3. TOR Test-Bed Topology and Deployment

5.3.1. Simulation Network Size

- -

- Twenty (20) FreeBSD Onion Routers including 3 dedicated Guard (Entry) ORs,

- -

- One Directory Server (DA),

- -

- Three (03) Onion Proxy (Clients),

- -

- One service server (destination),

- -

- Different size testing data

5.3.2. Test-Bed Preparations and Configuration

5.3.3. Logging and Measurements

5.4. Testing and Results

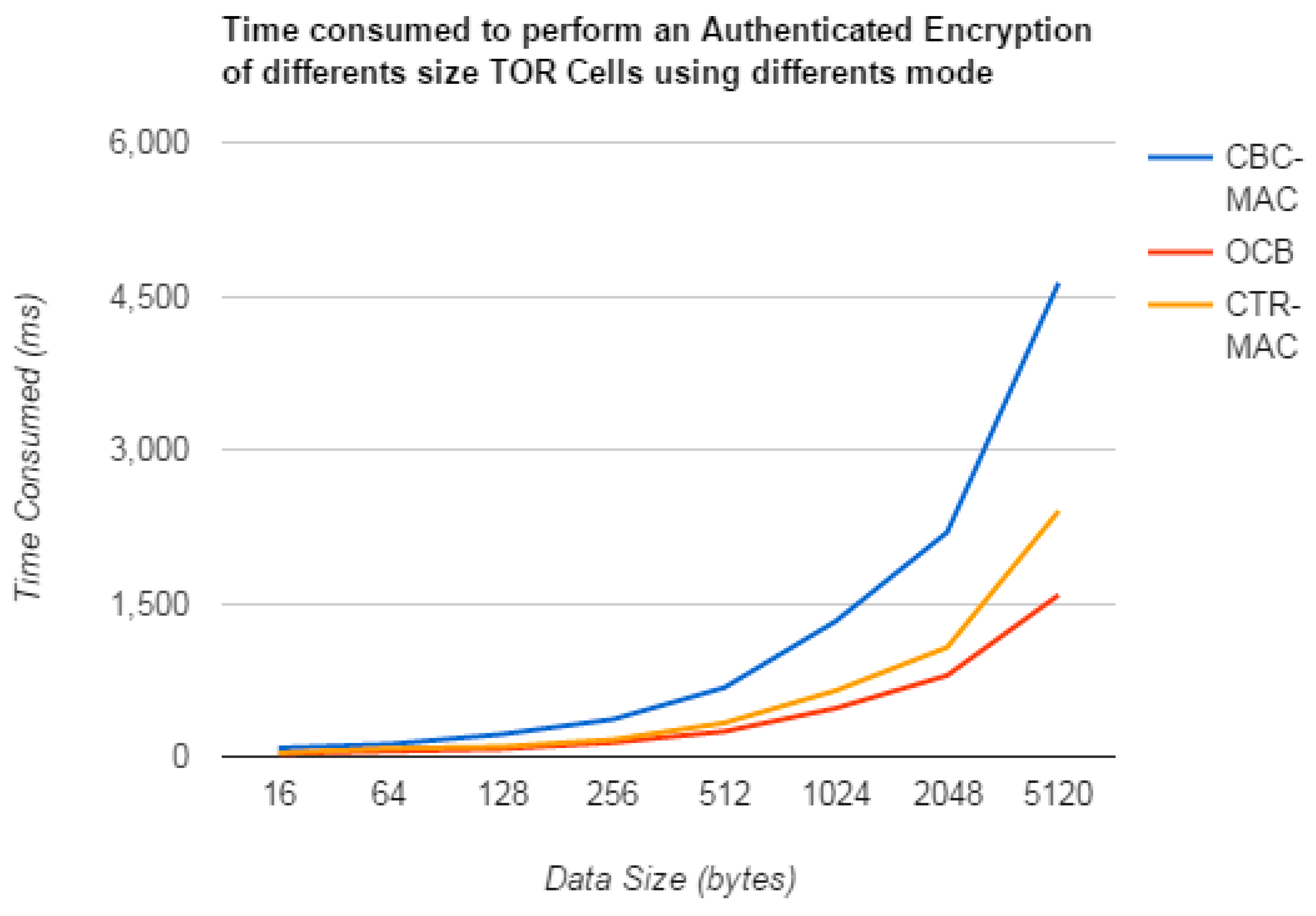

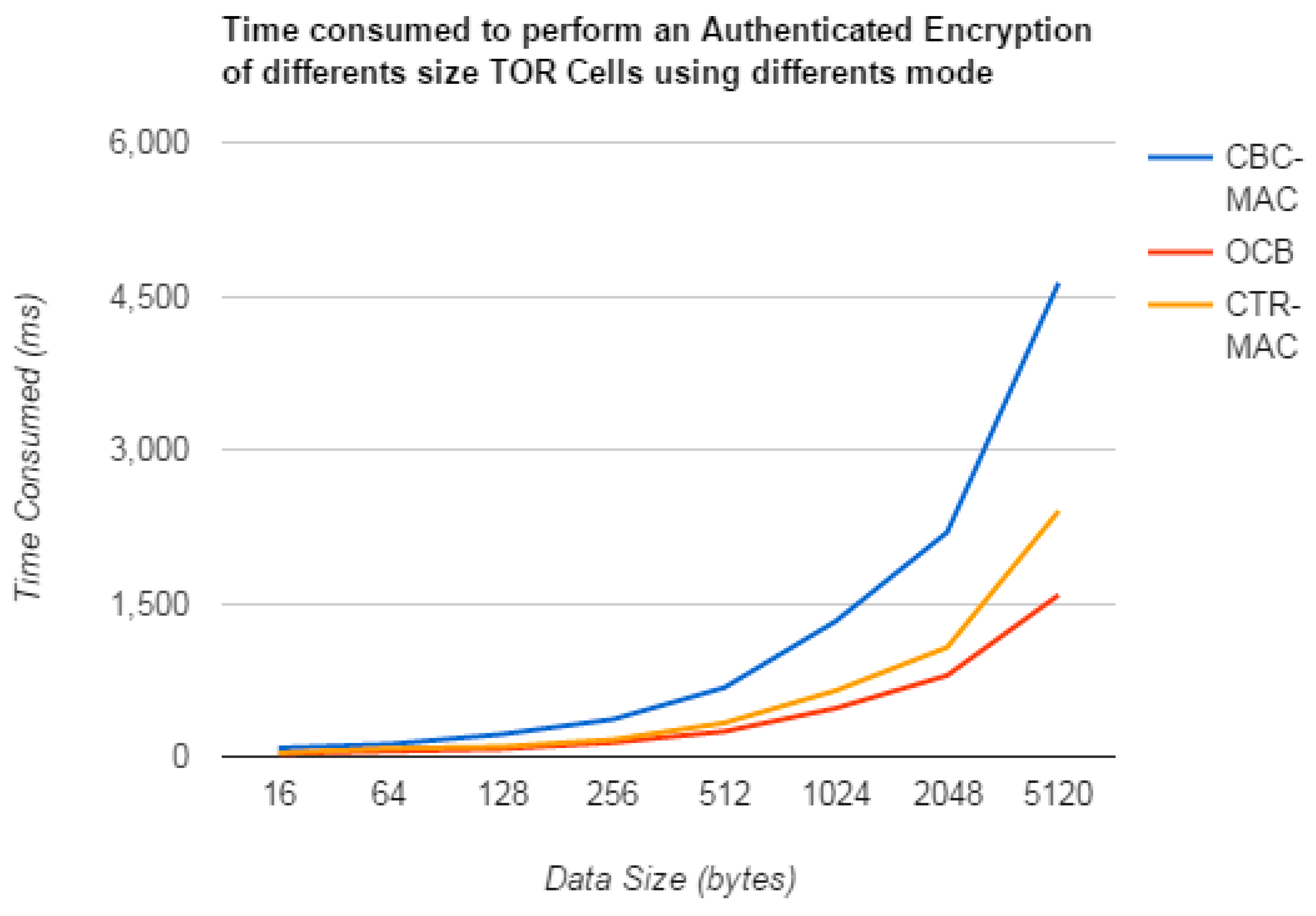

5.4.1. Testing the Proposed Ciphers and Encapsulation Approach

- -

- AES-OCB-128,

- -

- AES-CCM-128,

- -

- AES-GCM-128,

- -

- AES-EAX-128,

- -

- Add a separate MAC calculation function to the existing CBC and CTR code.

- a)

- Experimentation Results and Discussion

|

Input size

(Bytes) |

16 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 5120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time Consumed

(ms) per mode | ||||||||

| CBC | 64.11 | 102.31 | 198.34 | 344.76 | 634.21 | 1123.44 | 2011.54 | 4329.33 |

| OCB | 10.54 | 34.25 | 56.23 | 98.50 | 176.32 | 322.90 | 603.74 | 1488.60 |

| CTR | 5.82 | 20.58 | 36.77 | 65.88 | 129.98 | 245.34 | 468.13 | 1198.86 |

| Data Size | 16 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 5120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time Consumed

(ms) per mode | ||||||||

| CBC+MAC | 84.11 | 122.31 | 218.34 | 364.76 | 674.21 | 1323.44 | 2191.54 | 4629.33 |

| CTR+MAC | 35.82 | 80.58 | 96.77 | 165.88 | 329.98 | 645.34 | 1068.13 | 2398.86 |

| OCB | 29.54 | 54.25 | 76.23 | 138.50 | 246.32 | 472.90 | 793.74 | 1578.60 |

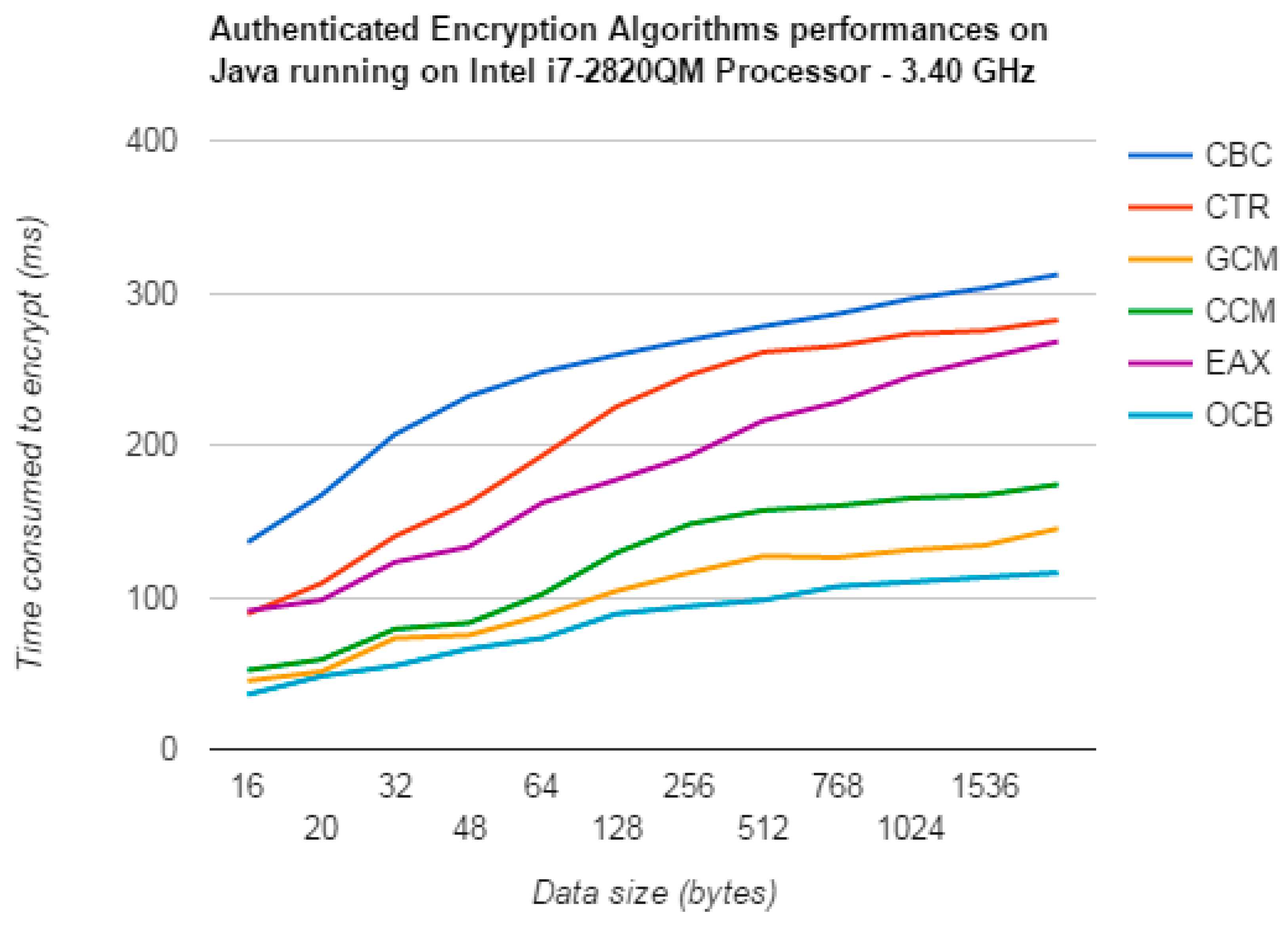

| Data size (Bytes) | 16 | 20 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 768 | 1024 | 1536 | 2048 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time consumed

(ms) per Mode | |||||||||||

| CBC | 136 | 167 | 207 | 232 | 248 | 259 | 269 | 278 | 286 | 299 | 312 |

| CTR | 89 | 109 | 140 | 162 | 193 | 225 | 246 | 261 | 269 | 275 | 282 |

| EAX | 91 | 98 | 123 | 133 | 162 | 177 | 193 | 216 | 228 | 257 | 268 |

| CCM | 52 | 59 | 79 | 83 | 102 | 129 | 148 | 157 | 160 | 167 | 174 |

| GCM | 45 | 51 | 73 | 75 | 88 | 104 | 116 | 127 | 131 | 139 | 153 |

| OCB | 36 | 48 | 65 | 73 | 89 | 101 | 113 | 120 | 127 | 135 | 148 |

- b)

- Encryption testing results

- c)

- Resources use analysis

- d)

- Choice and Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Work Output and Conclusion

6.2. Further Works

6.3. Work Evaluation

References

- AlSabah, M. and Goldberg, I. (2015). Performance and Security Improvements for Tor: A Survey.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., Elahi, T. and Goldberg. (2013a). The Path Less Travelled: Overcoming Tor’s Bottlenecks.

- with Traffic Splitting. In Privacy Enhancing Technologies - 13th International Symposium, PETS 2013,.

- Bloomington, IN, USA, July 10-12, 2013. Proceedings. Springer, 143–163.

- AlSabah, M. and Goldberg, I. (2013b). PCTCP: Per-Circuit TCP-over-IPsec Transport for Anonymous.

- Communication Overlay Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer.

- and Communications Security, CCS’13, Berlin, Germany, 349–360.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., and Goldberg, I. (2012). Enhancing Tor’s Performance Using Real-Time Traffic.

- Classification. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’12).

- . ACM, New York, NY, USA, 73–84.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., Goldberg, I., Grunwald, D., McCoy, D., Savage, S. and Voelker, G. (2011). DefenestraTor:.

- Throwing Out Windows in Tor. In Privacy Enhancing Technologies. 11th International Symposium, PETS.

- 2011, Waterloo, ON, Canada, July 27-29, 2011. Proceedings. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 134–154.

- Antonakakis, M., Edman, M. and Syverson, P. (2009). As-Awareness in TOR Path Selection. In Proceedings of.

- the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS 2009, Chicago, Illinois, USA,.

- ACM 380–389.

- Backes, M., Goldberg, I., Kate, A., & Mohammadi, E. (2012). Provably Secure and Practical Onion Routing.

- Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), 25, 369-385.

- Bauer, K. and Sherr, M. (2011). ExperimenTor: A Testbed for Safe and Realistic Tor Experimentation. USENIX.

- 2011, http://www.usenix.org/events/cset11.

- Bauer, K., Mccoy, D., Sherr, M. and Grunwald, D. (2011). ExperimenTOR: A test-bed for safe and realistic tor.

- experimentation. In Proceedings of the USENIX Workshop on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test (CSET).

- . Bogdanov, A., Lauridsen, M. and Tischhauser, E. (2014). AES-Based Authenticated Encryption.

- Modes in Parallel High-Performance Software. IEEE library.

- Fu, X. and Ling, Z. (2009). One Cell is enough to break Tor’s Anonymity. White Paper for Black Hat DC 2009.

- Boyd, W. (2011). A Simulation of Circuit Creation in Tor. Master thesis submitted at Wesleyan University,.

- Connecticut April, 2011.

- Benmeziane. S., Badache. N. & Bensimessaoud. S. (2011). Tor Network Limits. International Conference on.

- Network Computing and Information Security, 1, 200-205.

- Burstein, A. J. (2008). Conducting cyber security research legally and ethically. 1st USENIX Workshop on Large-.

- Scale Exploits and Emergent Threats, Berkeley, CA, USA, pages 1-8. USENIX Association.

- Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A. (2005). A formal treatment of onion routing. 25th Annual International.

- Conference in Advances in Cryptology CRYPTO 2005, 169-187.

- Carnielli, A. and Aiash, M. (2015). Will TOR Achieve its Goals in the Future Internet? An Empirical Study of.

- using TOR with Cloud Computing. 2015 29th International Conference on Advanced Information.

- Networking and Applications Workshops.

- Casenove, M., Miraglia, A. (2014). Botnet over Tor: The Illusion of Hiding. 6th International Conference on Cyber.

- Conflict P.Brangetto, M.Maybaum, J.Stinissen (Eds.), NATO CCD COE Publications, Tallinn.

- Castelluccia, C., De Cristofaro, E. and Perito, D. (2010). Private information disclosure from web searches. In.

- Mikhail J. Atallah and Nicholas J. Hopper, editors, Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 6205 of Lecture Notes in.

- Computer Science, 38-55.

- Dahal, S., Lee, J., Kang, J. and Shin, S. (2015). Analysis on End-to-End Node Selection Probability in TOR.

- Networking, IEEE ICOIN 2015 ISBN: 978-1-4799-8342-1/15.

- Danezis, G. Diaz, C. and Syverson, P. (2010). Systems for Anonymous Communication. In CRC Handbook of.

- Financial Cryptography and Security, CRC Cryptography and Network Security Series, B. Rosenberg, and D.

- Stinson (Eds.), 341-390.

- Darcie, W., Boggs, R., Sammons, J. and Fenger, T. (2013). Online Anonymity: Forensic Analysis of the Tor.

- Browser Bundle. ICDFSC 2013.

- Dingledine, R. and Mathewson, N. (2016a). TOR Directory Specification.

- https://gitweb.etorproject.org/torspec.git/tree/dir-spec.txt. (2016). Accessed March 2016.

- Dingledine, R. and Mathewson, N. (2016b). TOR Protocol Specification.

- https://gitweb.torproject.org/torspec.git/tree/tor-spec.txt. (2016). Accessed March 2016.

- Dingledine, R., Mathewson, N. & Syverson, P. (2004). Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router. 13th Security.

- Symposium (USENIX), 303–320.

- Dingledine, R., Mathewson, N., Murdoch, S. & Syverson, P. (2014). Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router.

- Draft 2014. http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/, Accessed on 11-02-2014.

- Douceur, J. (2002). The Sybil Attack. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Peer To Peer Systems Workshop (IPTPS 2002).

- . Volume 2429 of LNCS, Springer.

- Feigenbaum, J., Johnson, A. and Syverson, P. F. (2007). Probabilistic analysis of onion routing in a black-box.

- model. 6th ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (WPES), 1–10.

- Goldberg, I., Stebila, D. and Ustaoglu, B. (2012). Anonymity and one-way authentication in key exchange.

- protocols. IEEE ICPA 2012.

- Haraty, R.A. & Zantout, B. (2014). The TOR Data Communication System: A Survey. Journal of Communications.

- and Networks, 16, 415-420.

- Huhta, O. (2014). Linking Tor Circuits. MSc Information Security dissertation submitted to University College.

- London.

- Ghanem, M.C., Chen, T.M., Ferrag, M.A. and Kettouche, M.E., 2023. ESASCF: expertise extraction, generalization and reply framework for optimized automation of network security compliance. IEEE Access, 11, pp.129840-129853.

- Jansen, R., Geddes, J., Wacek, C., Sherr, M. and Syverson, P. (2014). US Never Been KIST: Tor’s Congestion.

- Management Blossoms with Kernel-Informed Socket Transport. Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Security.

- Symposium, San Diego, CA ISBN 978-1-931971-15-7.

- Johnson, A., Wacek, C., Jansen, R., Sherr, M. and Syverson, P. (2010). Users Get Routed: Traffic Correlation on.

- Tor by Realistic Adversaries, Association for Computing Machinery, ACM, US.

- Kate, A. and Goldberg, I. (2010). Distributed Private-Key Generators for Identity-Based Cryptography. 7th.

- Conference on Security and Cryptography for Networks (SCN), 436–453.

- Krovetz, T. and Rogaway, P. (2014).OCB implementation and performance analysis. IETF RFC publications.

- Lazzari, M. (2014). Systematic Testing of Tor. Submitted as Master Thesis, ETH Zurich.

- Ling, Z., Luo, J., Yu, W. and Fu, X. (2011). Equal-sized Cells Mean Equal-sized Packets in TOR. IEEE.

- Communications Society subject matter experts for publication in the IEEE ICC 2011 proceedings.

- Marquis, M. (2013). For their eyes only. The Commercialization of Digital Spying citizen lab Canada global.

- security research.

- Mccoy, D., Bauer, K., Grunwald, D., Kohno, T. and Sicker, D. (2008). Shining light in dark places: Understanding.

- the tor network. 8th international symposium on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, PETS '08, 63-76, Berlin.

- Murdoch, S. and Watson, R. (2007). Metrics for Security and Performance in Low-Latency Anonymity Systems.

- University of Cambridge, UK.

- Ghanem, M.C. and Ratnayake, D.N., 2016, June. Enhancing WPA2-PSK four-way handshaking after re-authentication to deal with de-authentication followed by brute-force attack a novel re-authentication protocol. In 2016 International Conference On Cyber Situational Awareness, Data Analytics And Assessment (CyberSA) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Nia, M.A., Karbasi, A.H. & Atani, R.E. (2014). Stop Tracking Me: An anti-detection type solution for anonymous.

- data. 4th International eConference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), 14, 685-690.

- Øverlier, L. and Syverson, P. (2006). Locating hidden servers. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Symposium on.

- Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, US, IEEE Computer Society.

- Perry, M. (2007). Securing the Tor Network, Black Hat USA 2007 Supplementary Handout.

- Reardon, J. and Goldberg, I. (2010). Improving TOR using a TCP-over-DTLS Tunnel. TOR project research.

- papers. https://gitweb.etorproject.org.

- Schanck, J., Whyte, W. and Zhang, Z. (2015). A quantum-safe circuit-extension handshake for Tor. Security.

- innovation white paper.

- Singh, S. (2015). Large-Scale Emulation of Anonymous Communication Networks. Matser thesis presented to.

- the University of Waterloo.

- Ghanem, M., Mouloudi, A. and Mourchid, M., 2015. Towards a scientific research based on semantic web. Procedia Computer Science, 73, pp.328-335.

- Ghanem, M., Dawoud, F., Gamal, H., Soliman, E., El-Batt, T. and Sharara, H., 2022, September. FLoBC: A decentralized blockchain-based federated learning framework. In 2022 Fourth International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA) (pp. 85-92). IEEE.

- Snader, R. and Borisov, N. (2008). A tune-up for Tor: Improving security and performance in the Tor network.

- Network & Distributed System Security Symposium, Interne Society.

- Soghoian, C. (2011). Enforced Community Standards for Research on Users of the Tor Anonymity Network.

- Second Workshop on Ethics in Computer Security Research WECSR, 02, St. Lucia.

- Stupples, D. (2013). Security Challenge of TOR and the Deep Web. The 8th International Conference for Internet.

- Technology and Secured Transactions ICITST 2013.

- Svenda, P. (2012). Basic comparison of Modes for Authenticated-Encryption (IAPM, XCBC, OCB, CCM, EAX,.

- CWC, GCM, PCFB, CS). Masaryk University in Brno.

- Farzaan, M.A.M., Ghanem, M.C., El-Hajjar, A. and Ratnayake, D.N., 2024. Ai-enabled system for efficient and effective cyber incident detection and response in cloud environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05602.

- Syverson, S., Goldschlog, D. and Reeds, M. (1997). Anonymous connections and onion routing. Proceedings of the.

- IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, USA, 482-494.

- TOR Deployment. (2016). TOR network detailed deployment. https://abouttor.tor.org, Acceded on April 2016.

- TOR Flow. (2016). TOR flux across the world. https://torflow.uncharted.software 2016-1-13, accessed on April.

- 2016.

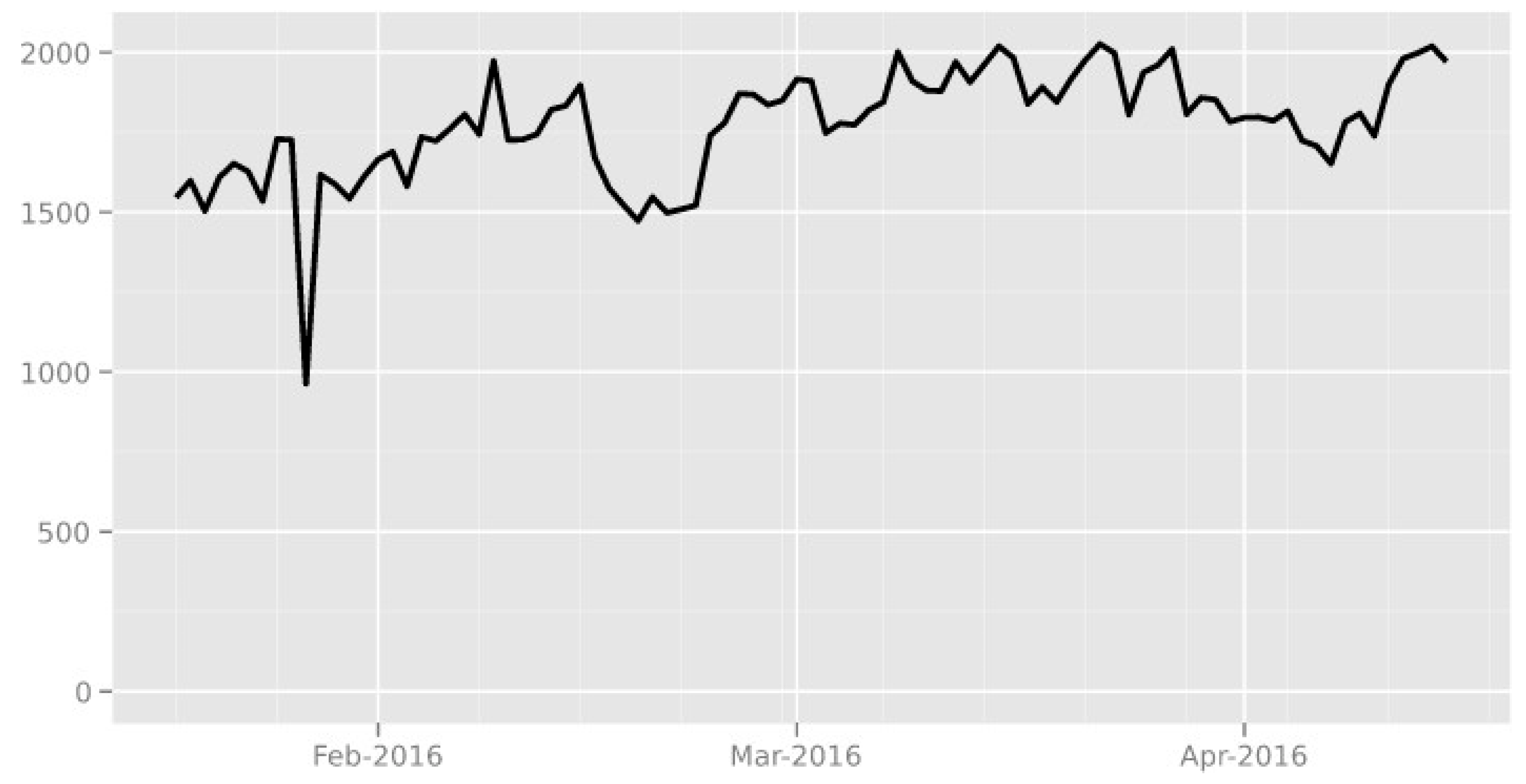

- TOR Project. (2016). TOR active users number in UK. https://metrics.torproject.org, accessed on April 2016. TOR.

- Metrics. (2016). TOR Network overall bandwidth. https://metrics.torproject.org/bandwidth.html,.

- accessed on April 2016.

- Wacek, C., Tan, H., Bauer, K. and Sherr, M. (2013). An Empirical Evaluation of Relay Selection in TOR. In.

- Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium - NDSS’13, The Internet Society.

- Yenuguvanilanka, J. and Elkeelany, O. (2007). Performance Evaluation of Hardware Models of Advanced.

- Encryption Standard (AES) Algorithm. Tennessee Tech University.

- Dunsin, D., Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2024. Reinforcement learning for an efficient and effective malware investigation during cyber Incident response. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.01999.

- Zhang, Y. (2009). Effective attacks in the tor authentication protocol. 3th International Conference on Network and.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).