1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major cause of death in developed countries [

1]. There are a number of risk factors contributing to the development of CAD including genetic, psychosocial, socioeconomic and environmental ones, as well as those linked to ethnicity, body composition, frailty or family history. Genetic factors can contribute as much as 40-60% to the disease [

2]. Inheritance of CAD can be either monogenic or polygenic [

3]. The etiology of the disease is complex and the variable phenotype is the result of interactions between multiple genes and environmental factors [

4]. Despite considerable progress made in recent years in the diagnosis and treatment of CAD, there is still a need to search for new genetic and phenotypic CAD markers.

Presently, in general, the use of genetic markers is not recommended in the diagnosis of CAD. This is in spite of the widespread availability of such tests [

6]. The only notable exception is the focus on monogenic inherited cardiovascular diseases caused by the LDLR gene mutation [

5]. Also, there is no acknowledged consensus on which genes should be included in genetic diagnostics. Instead, a lot of contemporary research in this area focuses on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) aiming to discover genetic variants that contribute to the development of CAD [

2], but their place in the pathomechanism of CAD is often unknown [

3].

Another approach attracting considerable focus is the candidate gene method, which focuses on the relationship between genetic variation within pre-specified genes of interest and phenotypes. One example of this approach is the study of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the methyl tetrahydrofolate reductase (

MTHFR) gene that causes methylation disorders. MTHFR, which is a key enzyme in the folate pathway, catalyses the conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to the active form of folic acid (5-MTHF). Folate metabolism disorders cause endothelial dysfunction (ED), which initiates the CAD development [

7].

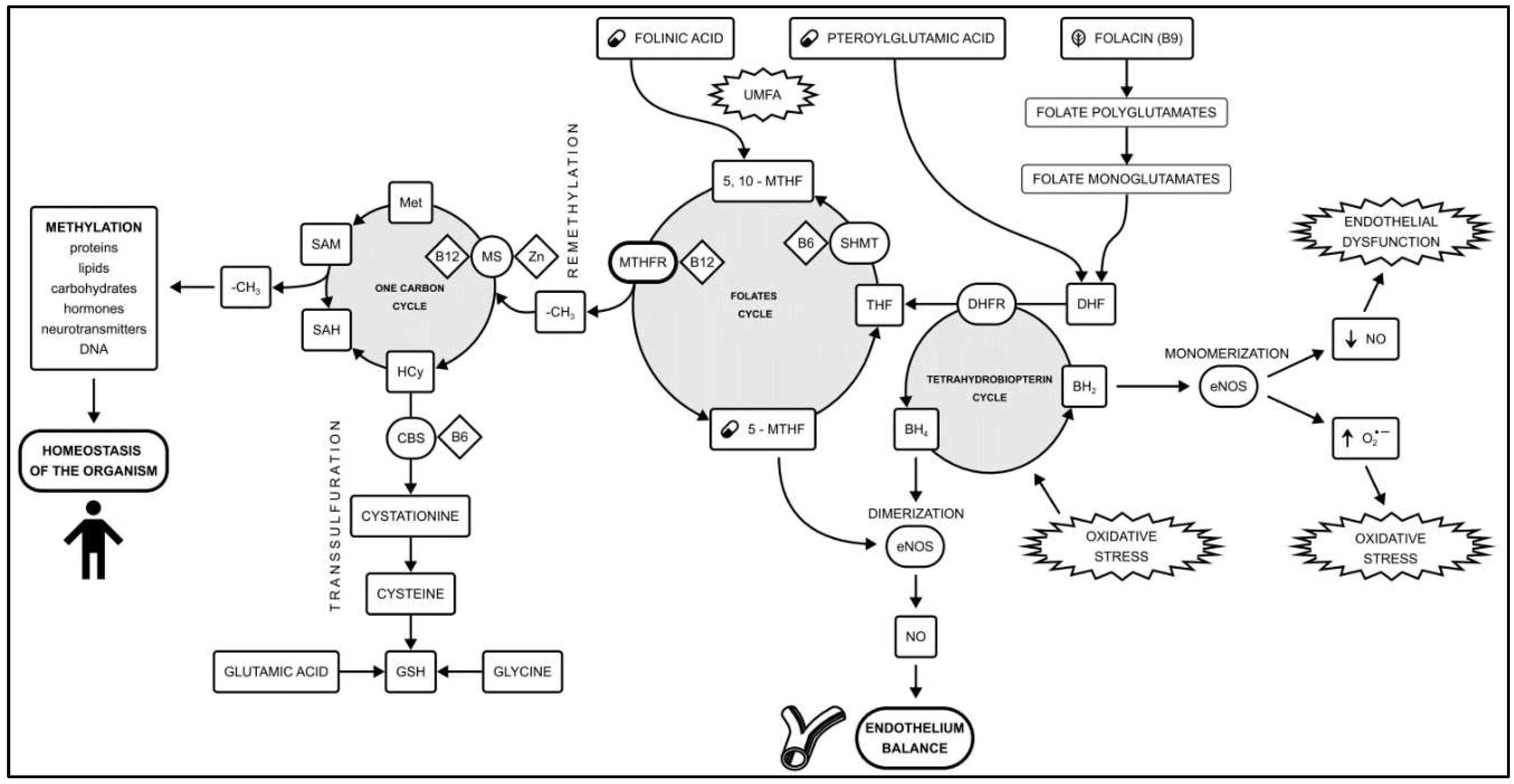

Methylation is a biochemical process in which a methyl group (-CH3) is transferred between donors and acceptors such as neurotransmitters, lipids, proteins and DNA. Methylation plays a key role in maintaining the homeostasis of the organism, as well as supporting the proper function of the vascular endothelium [

8]. The main metabolic pathways related to methylation are the folates cycle and the one-carbon cycle. An additional role is played by the transsulfuration pathway and the tetrahydrobiopterin cycle [

9] (

Figure 1). Naturally occurring folates are folic acid found mainly in green leafy vegetables and methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), which represents the active physiological form of folic acid in the blood. 5-MTHF’s availability plays a key role in the amount of circulating nitric oxide (NO) [

10,

11,

12]. Shifting the balance between NO production and oxidative stress in endothelial cells leads to endothelial dysfunction (ED), which is a key step in CAD development [

13].

Two of the most investigated

MTHFR SNPs are c.665C>T (rs1801133) and c.1286A>C (rs1801131). These polymorphisms can occur as a heterozygous genotype (polymorphism in only one allele), homozygous (polymorphism in both alleles), and in the form of complex heterozygotes (one of the above-mentioned polymorphisms in one allele and the other in the other allele). The frequency of polymorphisms varies by geographic location and ethnicity. According to the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) in the general European population, the c.665C>T polymorphic allele affects 30.85% of the population, and the c.1286A>C allele affects 28.58% of the population [

14]. The presence of the

MTHFR polymorphism results in a loss of 40 to 70% of enzyme function for variant c.665C>T and 30 to 50% for variant c.1298A>C [

15]. Maintaining an appropriate balance between substrates, products, cofactors and enzymes involved in the methylation process is essential for the organism’s homeostasis [

16].

According to current knowledge, ED is a reversible process [

17]. As stated in the present European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines, prevention methods centre around making changes to a lifestyle or pharmacotherapy for lipid disorders and hypertension [

18]. According to the standards in cardiovascular prevention regarding B vitamins (B6, B12) and folic acid supplementation, no beneficial effects have been demonstrated [

6]. Despite the availability of methylated forms of B vitamins and methylated folic acid (5-MTHF), studies on the metabolism of folates, including their methylated forms, have not been conducted so far. There have also been no studies on methylation disorders with confirmed coronary artery disease based on coronary angiography.

The aim of the study was to establish a correlation between methylation disorders caused by the MTHFR gene polymorphism and the folates (folic acid, 5-MTHF) metabolism in patients with CAD. Knowledge of the genetic background of CAD combined with phenotypic assessment based on new CAD biomarkers may improve cardiovascular risk estimation. An individual selection of drugs depending on genetic polymorphisms and mutations of a particular patient may contribute to the development of pharmacogenomics. Understanding the relationship between methylation disorders caused by the expression of the MTHFR gene (c.665C>T and c.1286A>C) and the folates (folic acid and 5-MTHF) metabolism may help to identify new therapeutic targets, including the justification of using of active (methylated) form of folic acid (5-MTHF) in patients with methylation disorders caused by MTHFR gene polymorphisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

A case-control study was conducted that comprised of patients of the Medical University of Lodz (Poland). All of the participants were Caucasian, Polish residents, recruited between February 2020 and October 2022, and have all signed an informed consent form. The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (Poland) approved the study (Registration number: RNN/78/19/KE form February 12th, 2019). We followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. In the study we used the “consecutive sampling” algorithm.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

All participants underwent invasive coronary angiography (ICA) (elective or due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or multislice computed tomography (MSCT) with an assessment of coronary artery calcification scoring (CAC scoring)).

Inclusion criteria: Presence of ≥ 50% stenosis of the left main coronary artery or ≥ 70% stenosis of one or more other major coronary arteries based on Quantitative Coronary Analysis (QCA) of one of the vessels: left anterior descending artery (LAD); circumflex branch of the left coronary artery (Cx); right coronary artery (RCA).

The control group included patients without CAD clinical symptoms or significant coronary artery stenosis based on ICA or MSCT with CAC scoring.

Exclusion criteria: chronic inflammatory diseases, severe anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dl), neoplastic diseases, immunosuppressive therapy, renal failure (glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2), thrombophilia, history of venous thromboembolism (past pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis), familial hypercholesterolaemia.

We obtained clinical data including history of early onset of atherosclerotic diseases in the subjects’ family (<55 years in men and <60 years in women), smoking status, previous ACS (angiographically documented), previous coronary revascularization procedures (percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)), comorbidieties (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes), pharmacological treatment, additional test results (documented reduction of the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessed by the Simpson method in transthoracic echocardiography(TTE); LVEF < 50% according to ESC guidelines), complete blood count, GFR, lipid panel.

2.2.1. Blood collection

The blood was collected into 2 tube-syringes: 4.9 ml of whole blood was taken with the anticoagulant ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for the genetic analysis and 2.6 ml of serum with clotting activator/gel for folates (5-MTHF and folic acid) analysis. Blood was collected from each of the participants from the basilic vein in the morning, after a 30-minute rest in a sitting or lying position. In total, biological material (venous whole blood) was collected from 213 patients who were included in the study from February 2020 to October 2022.

2.3. Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral venous blood samples using the GeneMatrix Blood DNA purification Kit (EURx, Gdańsk, Poland) in line with the manufacturer's protocol. DNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm on a Synergy HT spectrophotometer (BioTek, Hong Kong, China). Identification of polymorphic variants of the MTHFR gene c.665C>T (the terms C677T or C665T are no longer recommended; rs1801133 according to the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database) and c.1286A>C (the terms A1298C or A1286c are no longer recommended; rs1801131) was performed using TaqMan®SNP and TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix, No UNG (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) genotypic tests. A kit with primers and fluorescently labeled molecular probes was used for genotyping during real-time DNA polymerase chain reaction analysis. Markings were made in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. The total volume of the PCR reaction was 20 μl, including 4 μl of 5×HOT FIREPol®Probe qPCR Mix (Solis, Tartu, Estonia), 1 μl of DNA (100 ng), 1 μl of TaqMan SNP primers and 14 μl of RNA-free water. The PCR conditions were as follows: polymerase activation (10 min, 95°C), 30 cycles of denaturation (15 s, 95°C) annealing/extension (60 s, 60°C). Genotyping was performed in the Bio-Rad CFX96 system (BioRad, CA, USA).

2.4. Folates analysis

The Liquid Chromatography - Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) method was used to determine the concentrations of folic acid and its active form, 5-methyltetrahydrolofate (5-MTHF) in blood serum. LC-MS is a combined technique used in the qualitative and quantitative analysis of complex biological samples. Only the LC-MS tests are able to distinguish between different forms of folic acid: 5-MTHF, folic acid and folinic acid, and they should be used in the assessment of folate status, unlike the mass-used tests based on fluorescence, evaluating the level of all folates containing the pteroyl ring, without differentiating them. The use of such tests does not allow to reflect the level of the biologically active form of folic acid [

21]. Tests detecting 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not commonly used, despite that fact that only these tests enable the assessment of the concentration of a metabolically active methyl group donor. They also allow the actual reflection of the status of folic acid in

MTHFR gene polymorphism subjects [

22].

The LC-MS analysis was carried out using a DIONEX UltiMate 3000 liquid chromatograph equipped with a DAD (diode array detector) from Thermo Scientific coupled with a microOTOF-QIII mass spectrometer from Bruker.

I. Preparation of the sample for analysis: 1 ml of EtOH was added to the 0.5 ml of sample, mixed together and transferred to an Eppendorf (2 ml). Next, the sample was rinsed with an additional 0.5 mL of EtOH. Eppendorfs incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. After incubation, the probes were centrifuged. The supernatant was collected.

II. LC analysis: gradient elution (component A - water and component B - acetonitrile, both solvents with the addition of 0.1% formic acid); reverse phase column by Kinetex C18 100×4.6 mm without thermostating, particle size – 2.6 µm, pore size 100 Å; analysis program (B/A): 0–2 min 3/97, 2–31 min 95/5, 31–32 min 0/100, 32–33 min 0/100, 33–35 min 3/97, 35 –37.5 minutes 3/97; analytical wavelengths of the DAD detector: 214, 220, 256 and 291 nm; sample injection volume per column - 10 µl.

III. MS analysis: electrospray ionization method, flow rate of drying gas (nitrogen) 6.0 l/min, nebulizer pressure 2.4 Bar, capillary inlet temperature 250ᵒC, capillary voltage 4000 V; TOF (time of flight) detector. Solvents included in the eluent and used for sample preparation had the degree of purity required for LC-MS analysis. All obtained solutions were additionally centrifuged in order to remove possible impurities and residues of undissolved compounds.

The obtained chromatograms and MS spectra were processed using the DataAnalysis 4.2 program.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The collected results are presented as mean + standard deviation (SD) or median and quartile range (lower quartile, LQ [25%] - upper quartile, UQ [75%]), depending on the scale and distribution of the data. The normality of data distribution was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test, the homogeneity of variance was checked by the Brown-Forsythe test. Significance of differences between two independent groups of abnormal variables was calculated using the U-Mann-Whitney test. Otherwise, the Student's t-test for independent samples was used to analyze the two groups. Data that did not meet the condition of normal distribution/variance homogeneity in many groups were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test, using the classical approach, and with the use of bootstrap simulation (Monte Carlo model, 1,000,000 iterations). Multiple comparisons were checked post-hoc using Connover-Inman. Multi-parametric logistic regression with age and gender adjustment was used to analyze the relationship between the selected variables. The fit of the model was checked with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Due to the relatively small sample size and the low statistical power of the estimated inferences in some calculations, a model with recovery (resampling bootstrap, 10,000 iterations) was used to determine the probability of obtaining the revealed differences by pure chance. A replacement draw (or so-called repetition-not random draw) is a type of multiple draw where the same single draw from the same set of possible outcomes is repeated. In this procedure, the drawn object goes back to the pool before the next repetition of the draw and thus can be drawn many times. This, for example, happens when rolling a dice multiple times. Thanks to such a procedure, statistical parameters (averages, errors, test statistics) can be determined much more reliably, especially in the case of small samples. Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica v. 12.5 and Resampling Stats Add-in for Excel v.4.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the groups

The obtained results permitted a preliminary analysis of the 58 patients group. We divided the subjects according to the presence of coronary artery disease ( CAD+/- ) and the presence of methylation disorders caused by the MTHFR polymorphic variants.

The group consisted of 50 men and 8 women with an average age of 54.6 years and a median of 55.5 years. The youngest participant was 42 years old and the oldest 63 years old. The standard deviation for age was 5.9 years.

Table 1 presents clinical, demographic and biochemical parameters characterizing the study groups. The study group (CAD+) included 42 patients (38 men; 4 women) with a mean age of 53.1 years and a mean age at diagnosis of CAD at 47.1 years. All patients in this group underwent invasive coronary angiography in accordance with the inclusion criteria. The control group (CAD-) included 16 patients (12 males; 4 females) with no coronary stenoses based on invasive coronary angiography (11 subjects) or multislice computed tomography with CAC score (5 subjects).

More than half of the patients (54.8%) (CAD+) had a history of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), 88% had a history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and 19% had a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

In (CAD+) group, adjusted for age and gender, there was statistically more frequent incidence of hypertension [OR= 4.361264 (95% CI 1.015 - 18.735); p=0.042)], dyslipidemia [OR=4.313 (95% CI 0.993-18.723); p= 0.046)], nicotinism [OR=5.503 (95% CI 0.959-31.546); p=0.049)] compared to the group without coronary artery disease (CAD-) The groups (CAD+) and (CAD-) did not differ statistically significantly in terms of the percentage of obesity, diabetes and family history of early (<55 years in men and <60 years in women) onset of atherosclerotic diseases. In both groups, less than half of the patients had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction assessed by Simpson's method in transthoracic echocardiography (LVEF<50%). In the study group (CAD+), 90% of patients were treated with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), 90% with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), 78.6% with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT - clopidogrel/prasugrel/ticagrelor) 80.1% angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ACEI/ARBs), 85.7% beta-blockers (ꞵ-blockers), 0.02% calcium channel blockers (Ca-blockers), 14.3% diuretics (diuretics).

3.2. Frequencies of the genotypes

The obtained results regarding frequencies of

MTHFR genotypes and alleles in the study groups are presented in

Table 2.

In the (CAD+) group, the frequency of genotypes c.[665C=];[665C=] (both wild-type alleles, no polymorphism); c.[665C>T];[665C=] (heterozygous c.665C>T) and c.[665C>T];[665C>T] (homozygous c.665C>T) were respectively 32.4%, 26.5%, 41.2% vs. 21.4%, 21.4%, 57.1% for (CAD-) group.

The C ("wild-type") allele was present in 45.6% of (CAD+) group and in 32.1% of (CAD-) group. The T (polymorphic) allele was present in 54.4% of (CAD+) and in 67.9% of (CAD-) group.

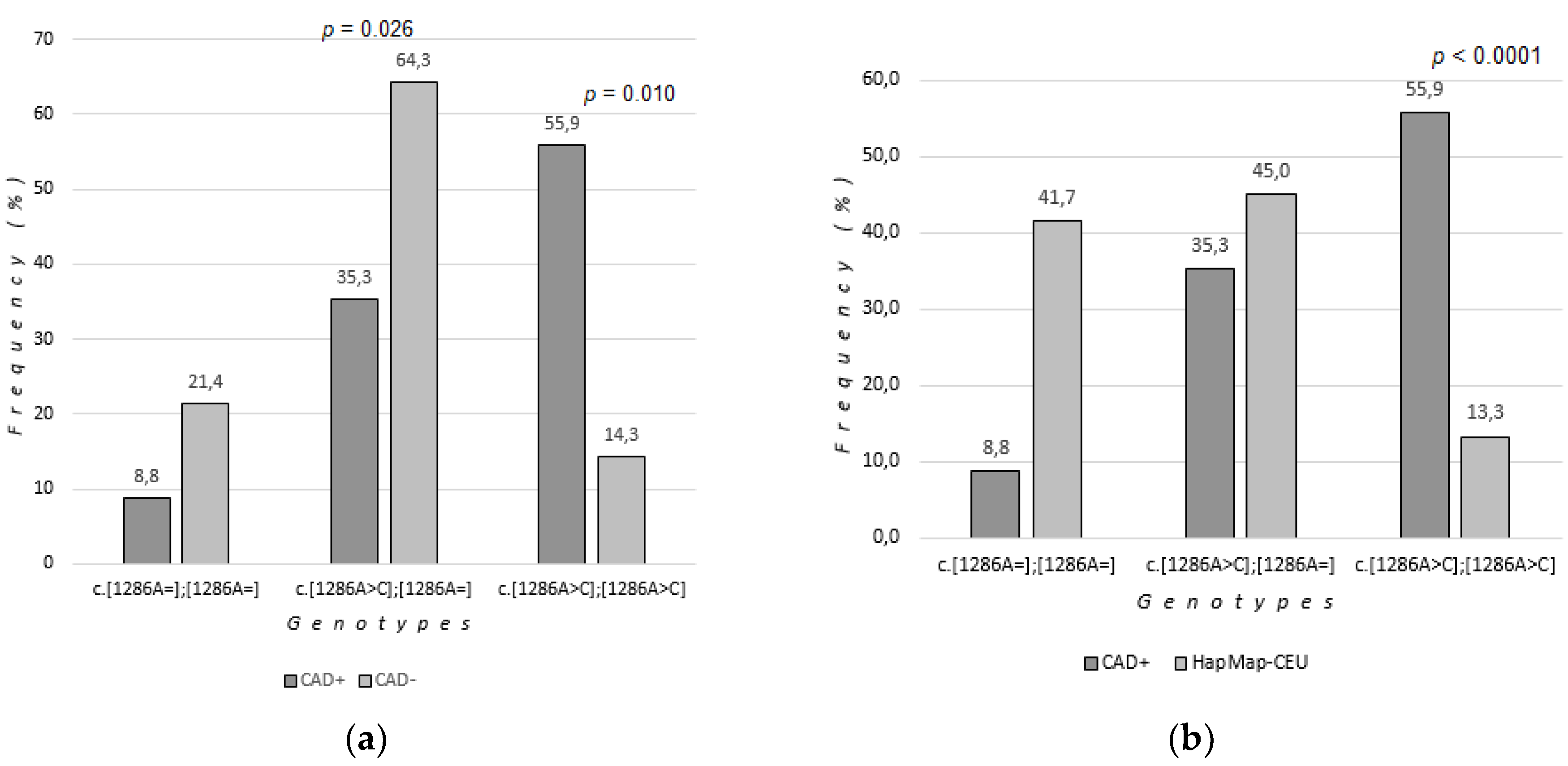

Genotypes c.[1286A=];[1286A=] (both wild-type alleles, no polymorphism), c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] (heterozygous c.1286 A>C) and c.[1286A>C ];[1286A>C] (homozygous c.1286 A>C) occurred at respectively 8.8%, 35.3%, 55.9% of (CAD+) group compared to 21.4%; 64.3%, 14.3% of (CAD-) group.

The A ("wild-type") allele was present in 26.5% of (CAD+) group and 73.5% of (CAD-) group. The C (polymorphic) allele was present in 73.5% of (CAD+ group) and 46.4% of (CAD-) group.

It was found that the c.[1286A>C];[1286A>C] (homozygous c.1286A>C) polymorphism of the

MTHFR gene was statistically significantly more frequent in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD+) compared to patients without coronary artery disease (CAD- ). Group comparisons were made using bootstrap-boosted logistic regression analysis (OR=24,652, 95% CI 2,024-300,267, p=0.010) (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

The c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] polymorphism (heterozygous c.1286 A>C) was statistically significantly less frequent in patients (CAD+) compared to patients (CAD-) (OR=0.081, 95% CI 0.008-0.791, p=0.026). The c.[1286A=];[1286A=] genotype (both wild-type alleles) was more common in the (CAD-) group, but the changes were not statistically significant.

A higher incidence of the C allele (polymorphic, occurring both in homozygous c.[1286A>C];[1286A>C] and heterozygous c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] genotypes) was observed in the group of patients with CAD (73.5%) compared to patients without CAD (46.4%).

There was no statistically significant relationship between the occurrence of MTHFR c.665C>T (rs1801133) gene polymorphisms and coronary artery disease.

The frequency of homozygous c.1286A>C genotype in the study group with coronary artery disease was compared to the frequency in the European population "HapMap-CEU", which consisted of 60 people (32 men, 28 women), selected for the statistical comparison from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, USA) database [

23].

Genotypes c.[1286A=];[1286A=] (both wild-type alleles, no polymorphism), c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] (heterozygous c.1286 A>C) and c.[1286A>C ];[1286A>C] (homozygous c.1286 A>C) occurred at respectively 41.67%; 45.00% and 13.33% of HapMap-CEU group (

Table 3). The A ("wild") allele was present in 64.17%, the C (polymorphic) allele in 35.83% of the European population.

It was found that the c.[1286A>C];[1286A>C] (homozygous c.1286 A>C) polymorphism of the

MTHFR gene was statistically significantly more frequent in the group of patients (CAD+) than in the European population. Group comparisons were made using bootstrap-boosted logistic regression analysis (OR=8.82, 95% CI 3.42-22.78, p<0.0001) (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

3.3. Folates concentrations

We checked whether the

MTHFR genotype has an impact on the folic acid and 5-MTHF concentrations (

Table 4 and

Table 5,

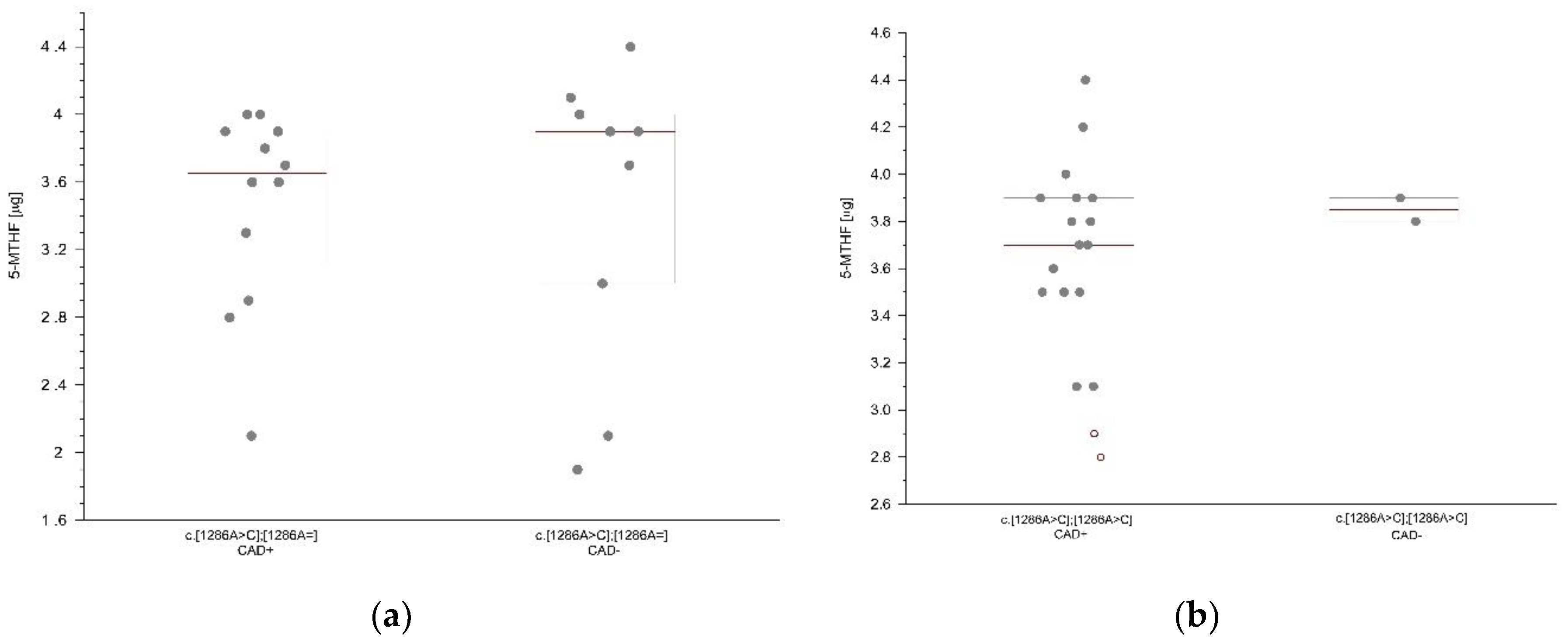

Figure 3).

3.1.1. Folates concentrations in MTHFR polymorphism patients

Serum folates levels assessed according to the genotype, without taking the presence or absence of CAD into account showed no statistically significant differences between the compared groups. However, we observed that in c.[665C=];[665C=] patients (“wild type”) the folic acid concentration in the blood serum was the highest of the three possible c.665 genotypes (1.95 μg/l). In c.[665C>T];[665C=] (heterozygous) patients the mean serum folic acid concentration was lower than in the wild type (1.90 μg/l). In c.[665C>T];[665C>T] (homozygous) patients the mean serum folic acid concentration was lower than in the wild type (1.90 μg/l) (

Table 4).

3.1.3. Folates concentrations according to the MTHFR genotype and the occurrence of coronary artery disease

We compared the mean serum folates concentration according to the presence and absence of coronary artery disease in the (CAD+) and (CAD-) groups with matching genotypes. In the group of patients with methylation disorders caused by the polymorphic variant c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] (heterozygous c.1286A>C) and coronary artery disease, a lower concentration of folic acid was observed (1.8 μg/l) compared to the group of patients without coronary artery disease (2.0 μg/l) with this genotype. In the group of patients with methylation disorders caused by the polymorphic variant c.[1286A>C];[1286A=] (heterozygous c.1286 A>C) and coronary artery disease, a lower concentration of 5-MTHF (3.65 μg/l) was observed compared to the group of patients without coronary artery disease (3.90 μg/l) with this genotype (

Figure 3a). In the group of patients with methylation disorders caused by the polymorphic variant c.[1286A>C];[1286A>C] (homozygous c.1286 A>C) and coronary artery disease, a lower concentration of 5-MTHF (3.7 μg/l) was observed compared to the group of patients without coronary artery disease (3.85 μg/l) with this genotype (

Figure 3b). However, the observed differences between the groups did not reach statistical significance (

Table 5).

A comparison of the (CAD+) versus (CAD-) patients with matching c.665C>T genotypes did not show statistically lower concentrations of folic acid and 5 MTHF in (CAD+) group (

Table 5). However, we observed that in the c.665 homozygous patients with CAD serum folic acid concentration was lower (1.9 μg/l) compared to matching (CAD-) group (1.95 μg/l). The concentration of 5-MTHF was lower in c.665 homozygous patients with CAD (3.7 μg/l) compared to matching (CAD-) group (3.8 μg/l).

4. Discussion

In a paper published in 2020 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the significance of impaired methylation in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases was proved [

24]. The individual’s methylation ability is genetically determined by polymorphisms of the

MTHFR gene. Regarding the individual genotype of the patient (hetero- or homozygosity in terms of the two most common polymorphisms c.665C>T and c.1286A>C), it affects about 30% of the European and 40% of the Polish population [

25,

26]. Methylation disorders due to

MTHFR polymorphisms are associated with the development of CAD [

27].

Currently, in cardiology, there are numerous publications dedicated to the development of atherosclerosis. The main focus is put on the lipidological processes, which in turn is related to the current progress of novel therapeutic drugs such as monoclonal antibodies that bind to and inhibit proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). Research into oxidative stress, metabolic pathways related to inflammation, as well as large-scale research such as genomic mapping of the genome; transcriptomics examining the conditions determining the activity of genes; proteomics determining the interactions of all proteins in the body and metabolomics analyzing endogenous metabolites of cell pathways still have few translations into clinical practice.

Studying the influence of genetic polymorphisms on circulating folate levels is important as it helps to understand the interplay of diet, genetics and CAD pathogenesis, and may also lead to identification of new therapeutic possibilities. Genetic variability in MTHFR may affect the concentration of folates and thus their biological functions in the methylation process.

This paper presented the effect of methylation disorders caused by MTHFR polymorphisms on the metabolism of folic acid and 5-MTHF in CAD patients. Our results showed a higher incidence of c.[1286A>C],[1286A>C] (c.1286 A>C homozygous) MTHFR polymorphism in patients with CAD confirmed by invasive coronary angiography (ICA) to controls without significant coronary artery stenosis based on ICA or multislice computed tomography (MSCT) with an assessment of coronary artery calcification scoring (CAC scoring). Observed differences were statistically significant. In addition, we found out that this homozygous variant is statistically significantly more frequent in patients with CAD compared to the European HapMap - CEU population selected for statistical comparison from the NCBI database. The study showed a lower occurrence of the c.1286 A>C heterozygote in patients with CAD, but a higher occurrence of the C allele (polymorphic, occurring in the c.[1286A>C];[1286A>C] homozygote as well as in the heterozygous c.[1286A>C];[1286A=]) in the group of patients with CAD.

There are few reports on the relationship between c.1286 A>C

MTHFR polymorphism and CAD, but they confirm the correlation observed in this study. In a population of 129 patients with a history of myocardial infarction, significant associations between the c.1286 A>C polymorphisms of the

MTHFR gene and the occurrence of coronary artery disease were found [

28]. In 2017, in a study on the population of 254 patients with angiographically confirmed coronary artery disease, it was found that this polymorphism is associated with the occurrence of coronary artery disease [

29]. In the population of 181 patients after myocardial infarction and 95 with ischemic heart disease (2021), it was found that polymorphisms c.1286 A>C and 665C>T of the

MTHFR gene were significantly more frequent in the group of patients with CAD [

30]. The results of genotype frequencies for c.665C>T polymorphism obtained in this study did not differ statistically significantly between groups with and without CAD. However in a meta-analysis of over 87,000 participants in 2018 (worldwide population), the T allele of the 665C>T

MTHFR polymorphism was found to be a risk factor for CAD, possibly and in part mediated by abnormal lipid levels [

27].

Despite the relatively small sample, the strength of this study is the inclusion criteria. There are many papers considering only the clinical presentation of patients (the absence of angina) or the absence of ischemic changes in the ECG as an exclusion criterion [

31,

32]. We included CAD patients on the basis of ICA and controls on the basis of ICA or MSCT with the CAC Scoring. It is known that the

MTHFR polymorphisms reduce the activity of the key enzyme involved in the cellular methylation pathway to 50% [

15]. Impaired function of

MTHFR enzyme causes the development of vascular endothelial dysfunction and initiates CAD. In our study, the c.1286 A>C homozygous

MTHFR polymorphism was found to be significantly more common in patients with CAD. This indicates the influence of this polymorphism in the development of CAD and it can be considered in terms of a CAD genetic marker.

The analysis of folates concentrations in our study showed that the concentration of folic acid was lower in heterozygotes and in homozygotes with methylation disorders caused by

MTHFR c.665C>T polymorphisms. However it was not statistically significant. In patients with the c.1286 A>C homozygous genotype, which is significantly more common in patients with CAD, as confirmed in this study, we observed lower concentrations of 5-MTHF. Lower 5-MTHF and folic acid levels were observed in patients with the c.1286 A>C heterozygous genotype. Lower 5-MTHF and folic acid levels were observed in patients with the c.665C>T homozygous genotype. Our results were not statistically significant, however they are consistent with the 2022 study conducted on the population of 1712 obese people, where it was found that in the case of

MTHFR gene polymorphisms (in homozygotes c.665C>T) the concentration of folic acid was significantly lower than in heterozygotes and in the wild type [

33]. Our results are consistent with the results of the 2022 study conducted on 1855 postmenopausal women, where lower folic acid concentration and higher homocysteine concentration were found in the homozygous c.665C>T variant of the MTHFR gene [

34]. However, in a whole-genome sequencing multicenter study no influence of the c.665C>T

MTHFR polymorphism on the concentration of folic acid was found. Instead, a gene located on the same chromosome responsible for the concentration of folic acid in the blood was selected [

35].

So far, to the best of the author’s knowledge, there are no publications regarding 5-MTHF serum concentrations depending on the genotype of CAD patients. The existing reports concern patients with psychiatric disorders (significantly lower concentration of 5-MTHF was observed in c.665C>T heterozygotes with schizophrenia, [

36]) and in women with breast cancer (5-MTHF concentration in the blood serum of 564 patients was found to be related to polymorphism c .665C>T and the pattern of the Mediterranean diet, [

37]). In a prospective cohort study conducted between 2011 and 2014 on 10661 participants of the general population, an increased risk of death from any cause was found in people with low levels of 5-MTHF in serum [

38]. Currently, the association of a low concentration of 5-MTHF and other diseases with the same risk factors as CAD is being investigated. This includes obesity (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [

39]), atherosclerosis (chronic kidney disease [

40]) and smoking (lung cancer [

41]). A significantly lower concentration of 5-MTHF was found in red blood cells in a group of 923 hypertensive patients [

42]. Lower concentration of 5-MTHF in red blood cells was found out in 200 patients with angiographically confirmed CAD compared to the control group [

43].

When it comes to the methodology, folate measurements can be taken in blood serum and plasma, as well as in red blood cells (RBCs) and in urine. There is evidence that RBC folate measurement is a good indicator of folate status due to their survival time of 120 days, while serum or plasma folate levels may be confounded. However, determination in RBC requires additional research methodology, which reduces efficiency, increases costs and introduces analytical problems [

44]. Tests available in clinical practice most commonly assess the concentration of folic acid using the Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ELCIA) method. Fluorescence-based tests assess the level of all folates containing a pteroyl ring, without differentiating them. The use of such tests does not reflect the level of the biologically active form of folic acid, the 5-MTHF. In the United States, there are commercially available tests assessing folate concentration using Competitive Protein Binding Assay (CPBA), but they are ineffective in detecting 5-MTHF deficiency too [

45]. In addition, there is a methodology for determining folates using microbiological tests (Microbiological assay, MBA).

Tests detecting 5-MTHF are not commonly used, despite the fact that only they enable the assessment of the concentration of a metabolically active methyl group donor as well as allow to reflect the folate status properly. Tests based on liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (LC-MS) are able to distinguish between 5-MTHF, pteroylglutamic acid and folinic acid, and they should be used in the assessment of folate status, but their usage is currently limited to scientific research [

22].

In the present study, folic acid and 5-MTHF concentrations were determined by LC-MS in serum samples (higher peak intensities were found). Several samples were tested with serum and plasma, but peak intensity was higher in the serum.

The obtained results show the influence of MTHFR gene polymorphisms on folate concentrations. The lack of statistical significance in our research may depend on the size of the groups, so it is reasonable to expand the size of the study group to confirm our findings. Folic acid and 5-MTHF concentrations were lower in heterozygotes and in homozygotes with genetically determined polymorphisms of the MTHFR gene at nucleotide positions 665 and 1286. Our study showed that patients with homozygous genotype c.1286 A>C, which is significantly more common in coronary artery disease, have lower concentration of methylated folic acid, which may indicate that the deficit of methylated forms of folic acid participates in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease.

4.1. Practical aspects of results and future directions of research. The use of active metabolites of folic acid (5-MTHF) in the prevention of coronary artery disease?

Coronary artery disease depends on genetic conditions and the lifestyle of patients. Unlike the classical CAD risk factors (dyslipidemia, nicotinism, hypertension, obesity), the polymorphisms remain unchanged throughout the life of the patient. Genetic diagnostics allows to identify people at high risk of CAD and to introduce early preventive actions and personalized therapy to improve their prognosis.

In cardiovascular disease prevention, the importance of a diet rich in folates is well-known. Current ESC guidelines on cardiovascular prevention emphasize the role of nutrition and recommend a diet rich in fruit (>200g/day) and vegetables (>200g/day) [

18]. The reference intake of folic acid in the adult diet should be 200 μg per day - mainly from green leafy vegetables.

The optimal level of folates concentration in the blood may be particularly important for maintaining the health of people with methylation disorders.

The current recommendations for the prevention of CAD do not diversify the patients in terms of their genotype, nor are there recommendations regarding the additional use of folates depending on methylation disorders caused by MTHFR polymorphisms in CAD patients.

On the contrary, when it comes to the prevention of defects of the central nervous system in pregnancy planning for women, it is recommended to use 400 μg of folic acid or its active metabolites a day. High doses of folic acid (up to 4–5 mg daily) are recommended for women who have given birth to children with such a defect [

46]. However, the form of folic acid (normal or methylated) does not depend on the genotype.

Too high doses of folic acid (>400ug per day) can be potentially harmful. Supplementation with synthetic folic acid can lead to a syndrome recognized as Unmetabolized Folic Acid (UMFA) syndrome [

47]. Synthetic folic acid may activate cell division, especially in the vascular smooth muscles, increasing their proliferation. There are reports of significantly more frequent restenosis in stents in patients after coronary artery revascularization procedures, in whom high (>1mg) doses of folic acid were used [

48]. From a public health perspective, mandatory fortification of food with synthetic folic acid has been implemented as an element of prevention of neural tube developmental defects in over 80 countries [

49].

It is reasonable to ask whether people with methylation disorders caused by the MTHFR polymorphism will benefit from such a procedure. Based on the available studies, we conclude that it should be predominantly the bioavailability of folic acid and the patient’s genotype that are taken into consideration first, in contrast to the current approach that focuses on increasing dosage of folic acid. The results of this study suggest that using methylated forms of folic acid (5-MTHF) in people with methylation disorders may be beneficial in the primary and secondary prevention of CAD. Probably in the future, prevention and personalized therapy of coronary artery disease will be based on information coming from the knowledge of the patient's genome sequence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P., A.PR. and R.I.; methodology, I.M., T.P., M.S., B.K., C.W. and R.P.; software, C.W.; validation R.I, R.P., I.M, C.W. and A.PR.. , formal analysis, C.W. and A.PR; investigation, R.P., A.PR, I.M., T.P., M.S., B.K. and J.W.; resources, R.I., I.M., B.K., C.W., J.K, T.P., A.PR. and R.P.; data curation, A.PR., R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.PR. and R.P; writing—review and editing, R.P, C.W., I.M., T.P., B.K. and R.I.; visualization, A.PR., C.W.; supervision, R.I., I.M., T.P., B.K., C.W. and R.P; project administration, R.P, A.PR, R.I and J.K.; funding acquisition, R.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.