Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry

2.2. Iron (II/III) chloride solutions

2.3. Aloysia citrodora water extract: LC-MS analysis

2.4. Differential pulse voltammetry of Aβ1-42

3. Results

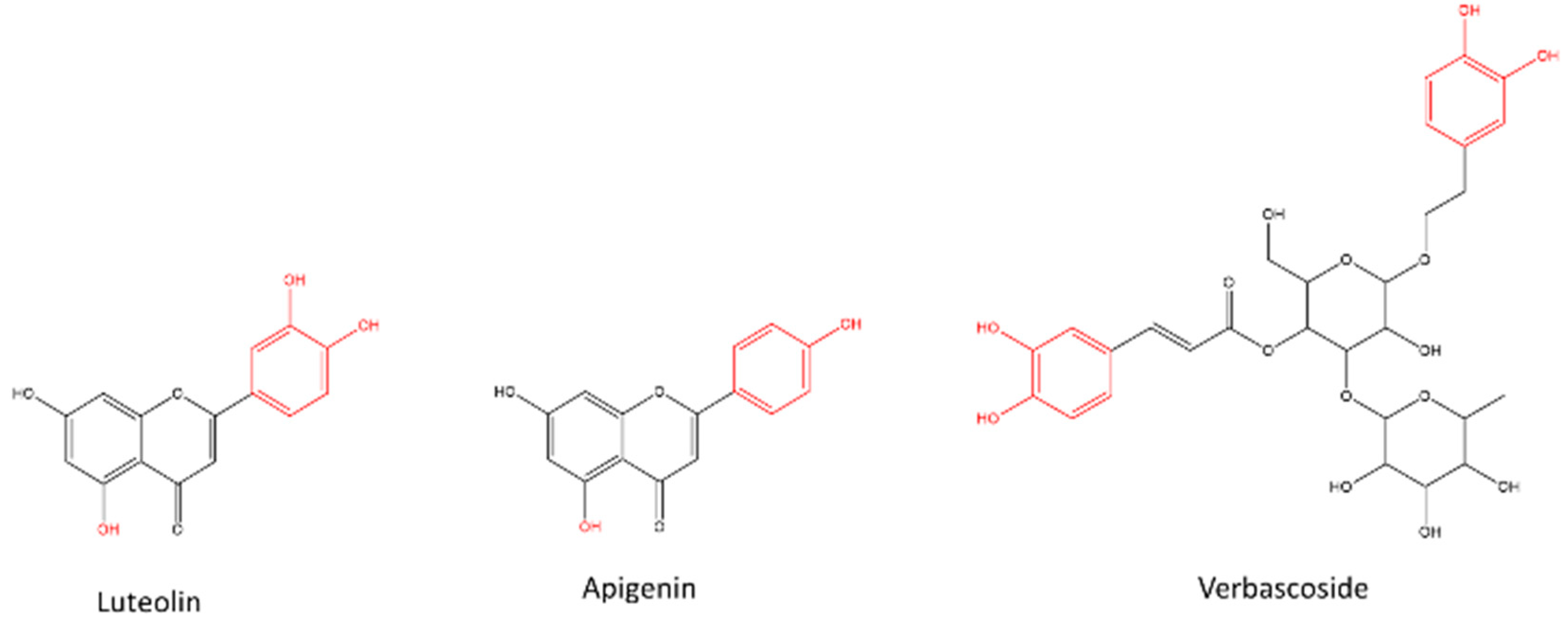

3.1. AC composition

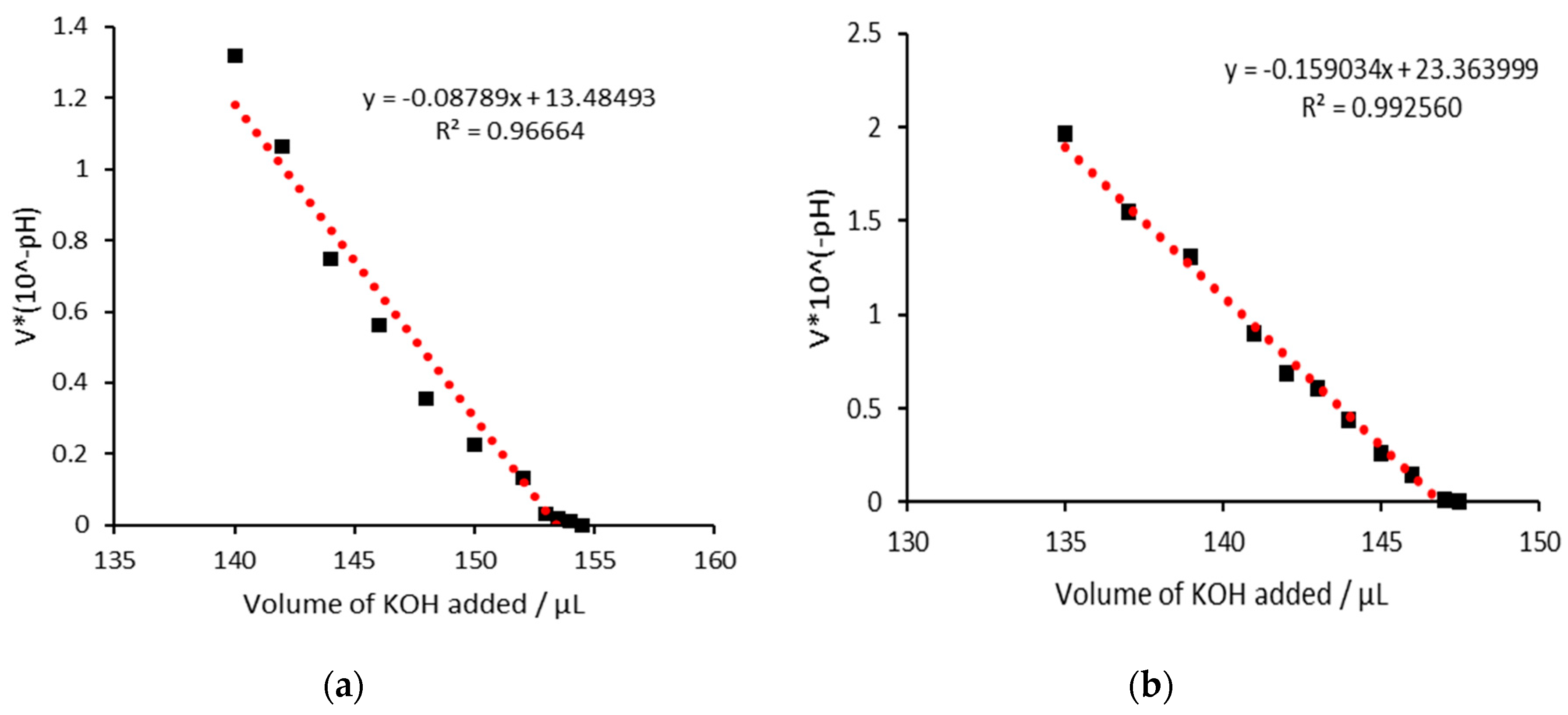

3.2. AC as an iron chelator

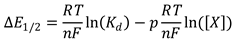

3.3. AC with iron (III)

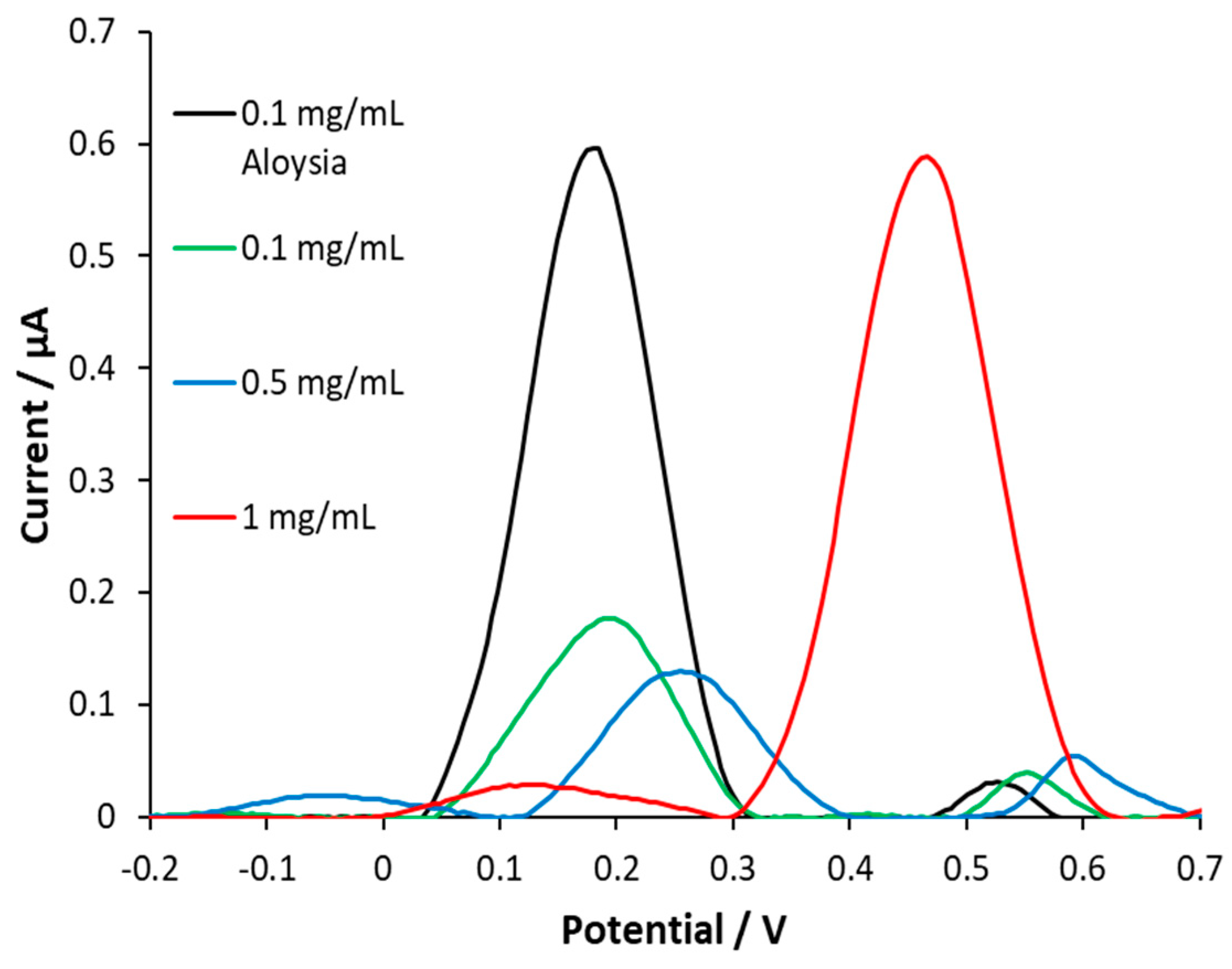

3.4. AC with iron(II)

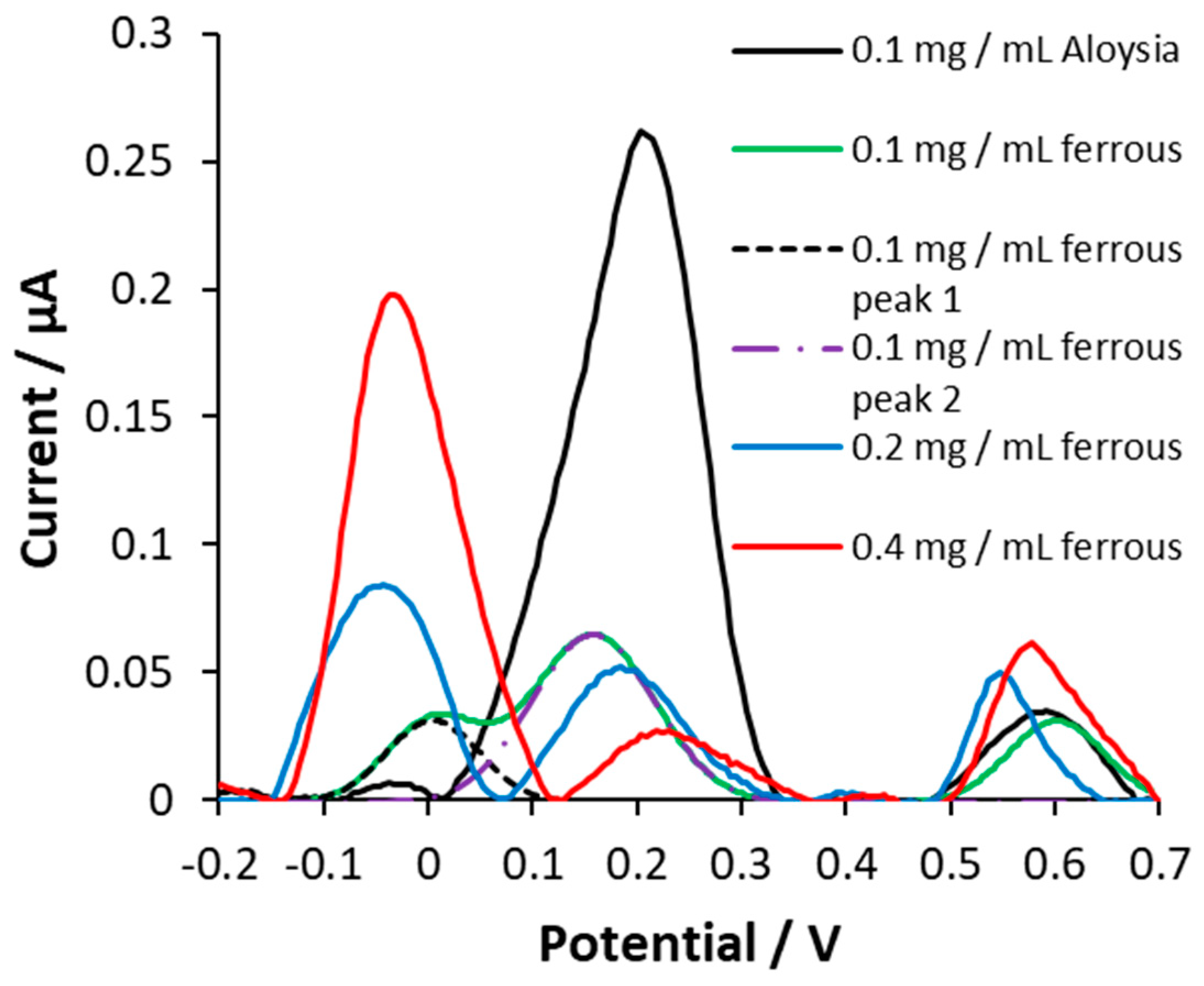

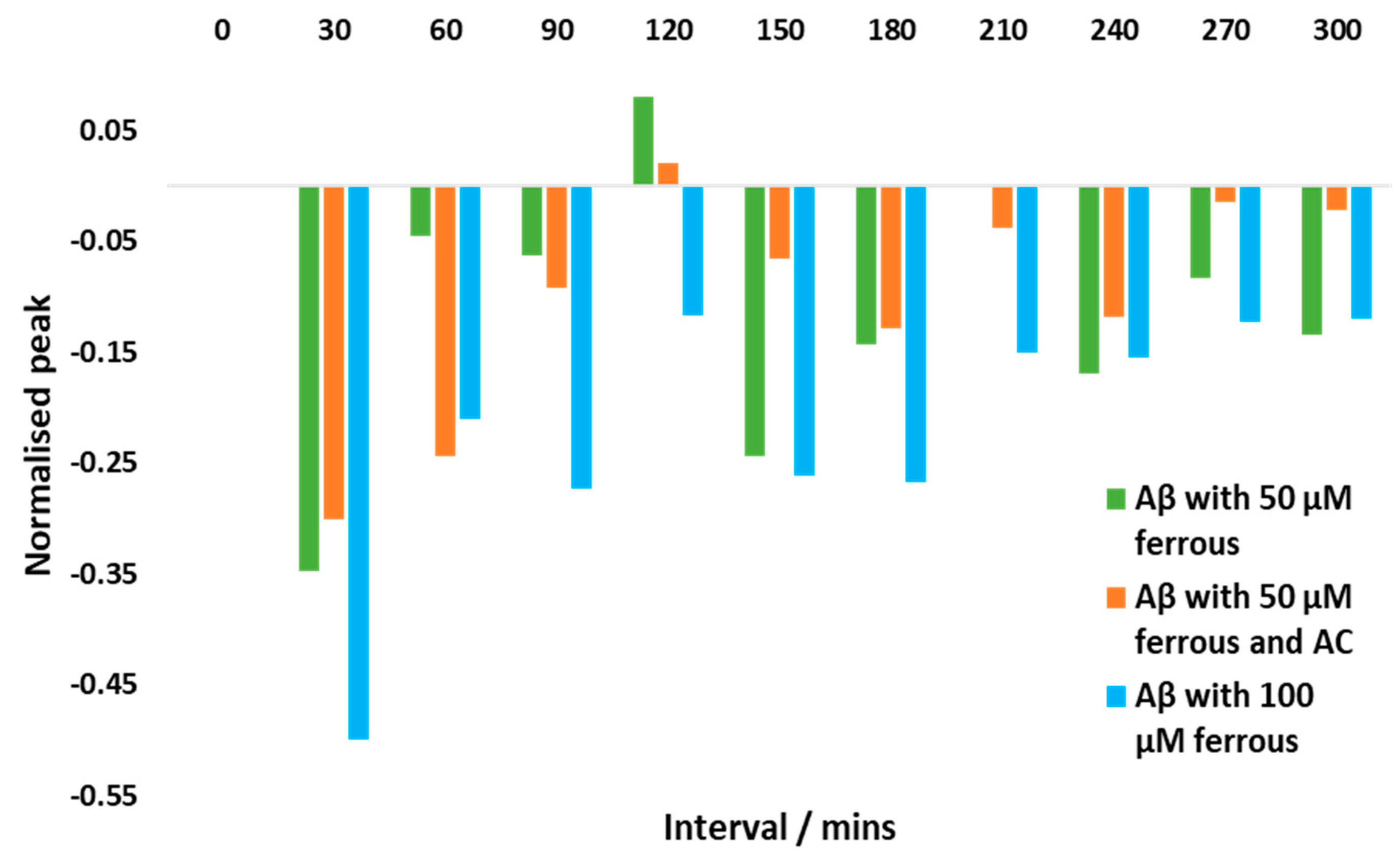

3.5. Monitoring Aβ1-42 aggregation using DPV

3.6. AC potentially ameliorates Aβ aggregation induced by iron (II)

4. Discussion

4.1. AC can bind to ferrous and ferric iron

4.2. Electrochemical changes in the Aβ1-42 structure

4.3. Iron can induce changes in Aβ1-42 aggregation and AC can offer potential mitigation

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Drayer, B.; Burger, P.; Darwin’, R.; Riederer’, S.; Herfkens’, R.; Johnson’, G.A. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Brain Iron. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 1986, 7, 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, P.; Santos, A.; Pinto, N.R.; Mendes, R.; Magalhães, T.; Almeida, A. Iron levels in the human brain: A post-mortem study of anatomical region differences and age-related changes. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllum, E.J.; Hare, D.J.; Volitakis, I.; McLean, C.A.; Bush, A.I.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Roberts, B.R. Regional iron distribution and soluble ferroprotein profiles in the healthy human brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 186, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, F.; Ma, Q. Brain iron deposition analysis using susceptibility weighted imaging and its association with body iron level in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 8209–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Shi, S.; Fu, C.; Han, X.; Gao, W.; et al. Increased Iron Deposition on Brain Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Correlates with Decreased Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, A.; Bush, A.I. Iron and Ferroptosis as Therapeutic Targets in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.; Adlard, P.A. Untangling Tau and Iron: Exploring the Interaction Between Iron and Tau in Neurodegeneration. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Shin, R.-W.; Hasegawa, K.; Naiki, H.; Sato, H.; Yoshimasu, F.; Kitamoto, T. Iron (III) induces aggregation of hyperphosphorylated τ and its reduction to iron (II) reverses the aggregation: implications in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2002, 82, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Ebralidze, I.I.; She, Z.; Kraatz, H.-B. Electrochemical studies of tau protein-iron interactions—Potential implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Electrochimica Acta 2017, 236, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, C.J.; Bush, A.I.; Masters, C.L.; Cappai, R.; Li, Q.-X. Metals and amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2005, 86, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.; Brooks, J.; Collingwood, J.F.; Telling, N.D. Nanoscale chemical speciation of β-amyloid/iron aggregates using soft X-ray spectromicroscopy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-L.; Fan, Y.-G.; Yang, Z.-S.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Guo, C. Iron and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Implications. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.; Céspedes, E.; Shelford, L.R.; Exley, C.; Collingwood, J.F.; Dobson, J.; van der Laan, G.; Jenkins, C.A.; Arenholz, E.; Telling, N.D. Ferrous iron formation following the co-aggregation of ferric iron and the Alzheimer’s disease peptide β-amyloid (1–42). J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousejra-ElGarah, F.; Bijani, C.; Coppel, Y.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C. Iron(II) Binding to Amyloid-β, the Alzheimer’s Peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9024–9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balejcikova, L.; Siposova, K.; Kopcansky, P.; Safarik, I. Fe(II) formation after interaction of the amyloid β-peptide with iron-storage protein ferritin. J. Biol. Phys. 2018, 44, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Huo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.; Xu, M. Electrochemical Monitoring of Reduction and Binding of Iron Amyloid-β Complexes at Boron-Doped Diamond Electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 10027–10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Österlund, N.; Wallin, C.; Wu, J.; Luo, J.; Tiiman, A.; Jarvet, J.; Gräslund, A. Metal binding to the amyloid-β peptides in the presence of biomembranes: potential mechanisms of cell toxicity. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 24, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Pittman, J.M.; Zerweck, J.; Venkata, B.S.; Moore, P.C.; Sachleben, J.R.; Meredith, S.C. β-Amyloid aggregation and heterogeneous nucleation. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1567–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deferiprone to Delay Dementia (The 3D Study) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved , from. 30 January. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03234686?term=deferiprone&draw=2&rank=4.

- Study of Parkinson’s Early Stage With Deferiprone - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved , from. 30 January. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02728843?term=deferiprone&draw=3&rank=19.

- Raines, D.; Sanderson, T.; Wilde, E.; Duhme-Klair, A.-K. Siderophores. Reference Module in 89 Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering. 2015. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-409547-2.11040-6. [CrossRef]

- Farr, A. C.; Xiong, M. P. Challenges and Opportunities of Deferoxamine Delivery for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2021, 18, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhamdah, S.; Abuhamdah, R.; Howes, M.-J.R.; Al-Olimat, S.; Ennaceur, A.; Chazot, P.L. Pharmacological and neuroprotective profile of an essential oil derived from leaves of A loysia citrodora Palau. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sripetchwandee, J.; Wongjaikam, S.; Krintratun, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. A combination of an iron chelator with an antioxidant effectively diminishes the dendritic loss, tau-hyperphosphorylation, amyloids-β accumulation and brain mitochondrial dynamic disruption in rats with chronic iron-overload. Neuroscience 2016, 332, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Lee, H.J. Redox-Active Metal Ions and Amyloid-Degrading Enzymes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnat, A.; Carnat, A.-P.; Chavignon, O.; Heitz, A.; Wylde, R.; Lamaison, J.-L. Luteolin 7-Diglucuronide, the Major Flavonoid Compound fromAloysia triphyllaandVerbena officinalis. Planta Medica 1995, 61, 490–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, D.; Degerine-Roussel, A.; Bred, A.; Ndoye, S.F.; Vivier, M.; Felgines, C.; Senejoux, F. A Novel HPLC Method for Direct Detection of Nitric Oxide Scavengers from Complex Plant Matrices and Its Application to Aloysia triphylla Leaves. Molecules 2018, 23, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Pellati, F.; Graziosi, R.; Brighenti, V.; Pinetti, D.; Bertelli, D. Identification and determination of bioactive phenylpropanoid glycosides of Aloysia polystachya (Griseb. et Moldenke) by HPLC-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirantes-Piné, R.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Characterization of phenolic and other polar compounds in a lemon verbena extract by capillary electrophoresis-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2010, 33, 2818–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwunze, M.O. Characterization of Cr-Curcumin Complex by Differential Pulse Voltammetry and UV-Vis Spectrophotometry. ISRN Anal. Chem. 2014, 2014, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorcea-Paquim, A.-M.; Enache, T.A.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Electrochemistry of Alzheimer Disease Amyloid Beta Peptides. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 4066–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorcea-Paquim, A.-M.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Amyloid beta peptides electrochemistry: A review. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 31, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Kerman, K. Electrochemical approaches for the detection of amyloid-β, tau, and α-synuclein. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2019, 14, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhulkar, S.; Piatyszek, R.; Cirrito, J.R.; Wu, Z.-Z.; Li, C.-Z. Microbiosensor for Alzheimer’s disease diagnostics: detection of amyloid beta biomarkers. J. Neurochem. 2012, 122, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D. C. , & Lucy, C. A. (2019). Quantitative chemical analysis. W H Freeman & Co.

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Sun, C. Role of Flavonoids in the Treatment of Iron Overload. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshavn, K.J.; Jang, M.; Kwak, Y.J.; Kochi, A.; Vertuani, S.; Bhunia, A.; Manfredini, S.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Lim, M.H. Reactivity of Metal-Free and Metal-Associated Amyloid-β with Glycosylated Polyphenols and Their Esterified Derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Meng, S.; Lekka, C.E.; Kaxiras, E. Complexation of Flavonoids with Iron: Structure and Optical Signatures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Dodin, G.; Yuan, C.; Chen, H.; Zheng, R.; Jia, Z.; Fan, B.-T. “In vitro” protection of DNA from Fenton reaction by plant polyphenol verbascoside. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2005, 1723, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, J. M. D. , Marković, Z. S., Brdarić, T. P., Pavelkić, V. M., Jadranin, M. B.. Iron complexes of dietary flavonoids: Combined spectroscopic and mechanistic study of their free radical scavenging activity. Food Chemistry, 2011, 129, 1567–1577. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/6159653/Iron_complexes_of_dietary_flavonoids_Combined_spectroscopic_and_mechanistic_study_of_their_free_radical_scavenging_activity. [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.R.; Perry, N.S.; Vásquez-Londoño, C.; Perry, E.K. Role of phytochemicals as nutraceuticals for cognitive functions affected in ageing. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1294–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Londoño CA, H. M.-J. C. G. A. G. R.-C. M. (2023). Scutellaria incarnata Vent. root extract and isolated phenylethanoid glycosides are neuroprotective against C2-ceramide toxicity.. Journal of Ethnopharmacology.

- Taneja, V.; Verma, M.; Vats, A. Toxic species in amyloid disorders: Oligomers or mature fibrils. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2015, 18, 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolar, M.; Hey, J.; Power, A.; Abushakra, S. Neurotoxic Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Drive Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis and Represent a Clinically Validated Target for Slowing Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Zhao, L.; Long, H.W.; Mu, Y.; Chew, L.Y. The Toxicity of Amyloid ß Oligomers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7303–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, C.; Brennan, S.; Keon, M.; Ooi, L. The role of amyloid oligomers in neurodegenerative pathologies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canevari, L.; Abramov, A.Y.; Duchen, M.R. Toxicity of Amyloid β Peptide: Tales of Calcium, Mitochondria, and Oxidative Stress. Neurochem. Res. 2004, 29, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enache, T.A.; Chiorcea-Paquim, A.-M.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Amyloid–β peptides time-dependent structural modifications: AFM and voltammetric characterization. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 926, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprun, E.V.; Radko, S.P.; Kozin, S.A.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Makarov, A.A. Application of electrochemical method to a comparative study of spontaneous aggregation of amyloid-β isoforms. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-P.; Chang, G.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Kuo, Y.-M. Kinetic analysis of β-amyloid peptide aggregation induced by metal ions based on surface plasmon resonance biosensing. J. Neurosci. Methods 2006, 154, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.D.; Zárate, A.M.; Fuentes-Lemus, E.; Davies, M.J.; López-Alarcón, C. Formation and characterization of crosslinks, including Tyr–Trp species, on one electron oxidation of free Tyr and Trp residues by carbonate radical anion. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 25786–25800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assigned compound (or isomer) |

Retention time (min) | Molecular formula | m/z | Ion | ppm# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luteolin 7-diglucuronide* | 8.3 | C27H26O18 | 639.1193 | [M + H]+ | 0.109 |

| Di-O-galloylcrenatin or isomer | 9.5 | C27H26O17 | 623.1242 | [M + H]+ | 0.105 |

| Diosmetin 7-diglucuronide* | 9.9 | C28H28O18 | 653.1357 | [M + H]+ | 1.378 |

| Verbascoside* | 10.3 | C29H36O15 | 625.2143 | [M + H]+ | 2.548 |

| Acetylverbascoside | 10.6 | C31H38O16 | 667.2246 | [M + H]+- | 1.931 |

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin 4’-methyl ether 6-O-glucuronide | 10.8 | C22H20O13 | 493.0985 | [M + H]+ | 1.649 |

| 6-Hydroxyapigenin 4’-methyl ether 6-O-glucuronide | 12.0 | C22H20O12 | 477.1042 | [M + H]+ | 3.013 |

| Apigenin 4’-methyl ether 7-diglucuronide* | 12.1 | C28H28O17 | 637.1407 | [M + H]+ | 1.200 |

| Hydroxy-megastigmenone malonyl-hexoside | 12.7 | C22H34O10 | 459.2229 | [M + H]+ | 0.928 |

| Hydroxy-megastigmenone malonyl-hexoside | 13.1 | C22H34O10 | 459.2237 | [M + H]+ | 2.583 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).