3. Offset boosting for symmetric pairs of strange attractors

If a variable substitution:

, (here

,

) in a dynamical system

(

leads to

(

, the variable

in system

obtains the operation of offset boosting, and for this reason its average value gets boosted by the new introduced constant

. The variable

can be a signal in an electrical system, correspondingly the signal gets offset-boosted by a direct current voltage of

. When the operation

only introduces an independent constant

in one dimension in the system, then the system was named as a variable-boostable system [

28]. For a variable-boostable dynamical system

(

, there exists one and only one

(

) satisfying

, where

k is a nonzero constant.

Offset boosting is an effective technique for shifting an attractor in phase space without changing the basic dynamics of a system. In a system

,

, take the substitution of

,

,

, the offset of the variable

get boosted. The offset parameter

can move the attractor switching from the negative zone to the positive zone divided by the dimension

,

. In fact, an attractor can be moved in any dimension by offset boosting. From this view, when the offset boosting is completed by an absolute-value function, corresponding attractors can get doubled by the combination of polarity compensation. The mechanism is as explained in [

29,

30,

31].

If the system (5) has coexisting solutions identified by attractors like,

, take the offset-boosting constants as

, subjecting to any state vector

to satisfy

, then substituting

with

,

into system (5) like,

Then:

(I) System (6) is of symmetry according to the dimension of ;

(II) System (6) has 2m coexisting attractors;

(III) All the attractors in system (6) share the same structure with the ones in system (5) and all the equilibria in system (6) have the same stabilities with those of system (5).

Take the above method for constructing coexisting attractors in the Rössler system [

32,

33], which is described by,

We know, when

a =

b = 0.2,

c = 5.7, the system is chaotic with Lyapunov exponents (LEs) of (0.0714, 0, −5.3943) and a Kaplan-Yorke dimension of

DKY = 2.0132. Replace the variable

z with an absolute function |

z|−

d,

This time, system (8) turns to be a reflection invariant system since it is of polarity balance when

z turns to be

–z, and the attractors get doubled according to the

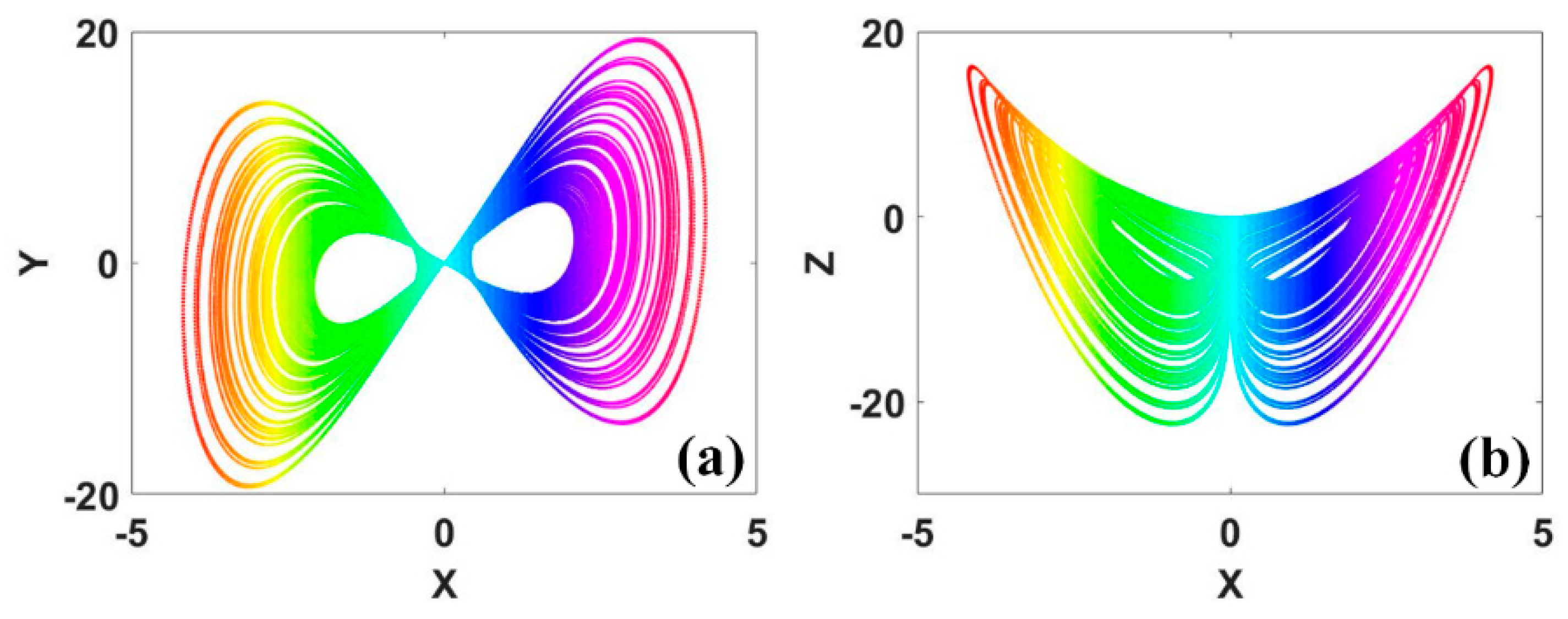

z-axis, as shown in

Figure 11. Larger offset constant

d will separate the coexisting attractors more far away in this direction, for example, let

d = 12, the two attractors stand in phase space far away, as shown in

Figure 12. More absolute functions can turn the original Rössler system to be of other regimes of symmetry. That is to say, take |

x|

– d1, |

y|

– d2, |

z|

– d3, the derived system is of inversion symmetry, and when the variables

x, y, and

z get polarities inversed, the derived system keep the same equation, as written in system (9),

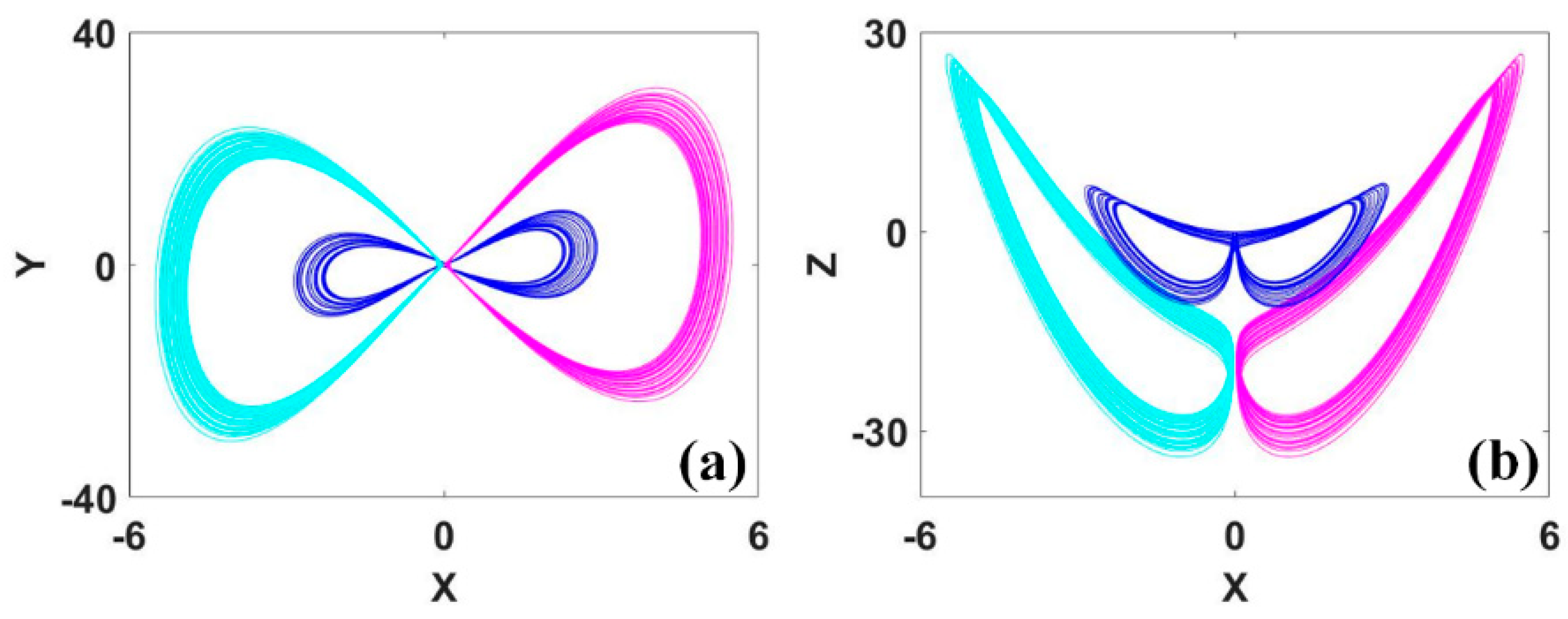

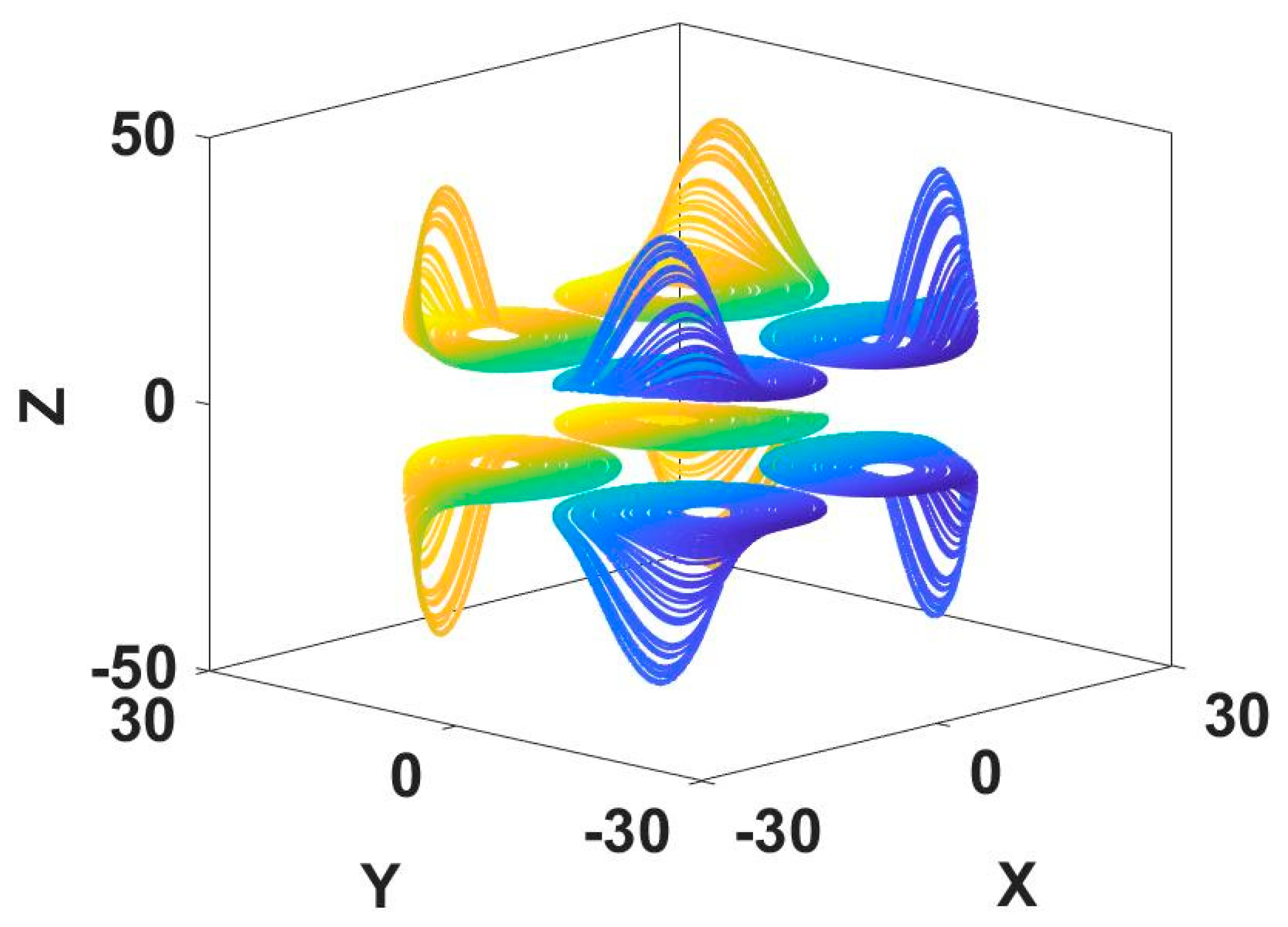

And at this time, the original attractor gets three times of doubling, and then totally eight attractors show up, as displayed in

Figure 13.

4. Coexisting strange attractors of conditional symmetry

As we know, a system variable like

x can be written as

x = |

x|sgn(

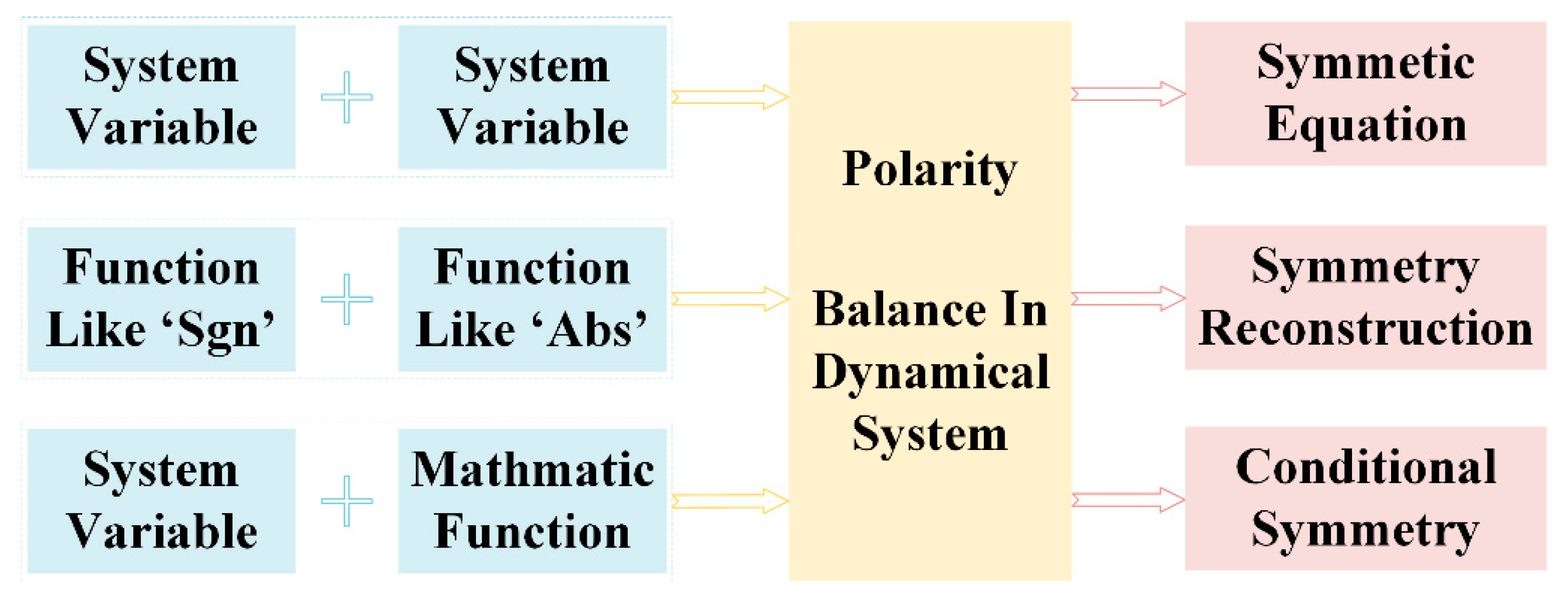

x). In fact, any variable in an equation includes two types of inherent features: the amplitude and the polarity of the variable. Therefore, there are two effective polarity adapters: one is the signum function for maintaining the polarity, and the other is the absolute value function removing the polarity. The combination of signum function and absolute-value function can producing coexisting doubled attractors. At the same time, the absolute-value function is an effective way for the producing of functional polarity reverse leading to coexisting conditional symmetric attractors. Therefore, from the conception of conditional symmetry, we could conclude that if some of the variables get the polarities reversed, the additional operation like offset boosting may return the polarity balance and result in symmetrically attractor doubling or conditional symmetry, as shown in

Figure 14. The polarity adapter and slide polarity converter are widely applied in a dynamical system for giving conditional symmetry or attractor self-reproducing.

For a dynamical system

(

, when the variable substitution including polarity reversal and offset boosting such as

, (here

,

,

and

are not identical,

) lead to the derived system retaining its polarity balance and satisfy

(

he system

(

is of l-dimensionally conditional symmetry since the polarity balance needs an l-dimensional offset boosting [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. For a three-dimensional system,

(

, the regime could be conditional rotational symmetry in 1-dimension and conditional reflection symmetry in 1-dimension or 2-dimension.

The mechanism of conditional symmetry is associated with the offset boosting for polarity balance. Suppose we want to construct a conditional reflection symmetric system, here the variable

gets polarity reversed, which will revise the polarity of

, and in turn requires the polarity reverse on the right-hand side of

to get

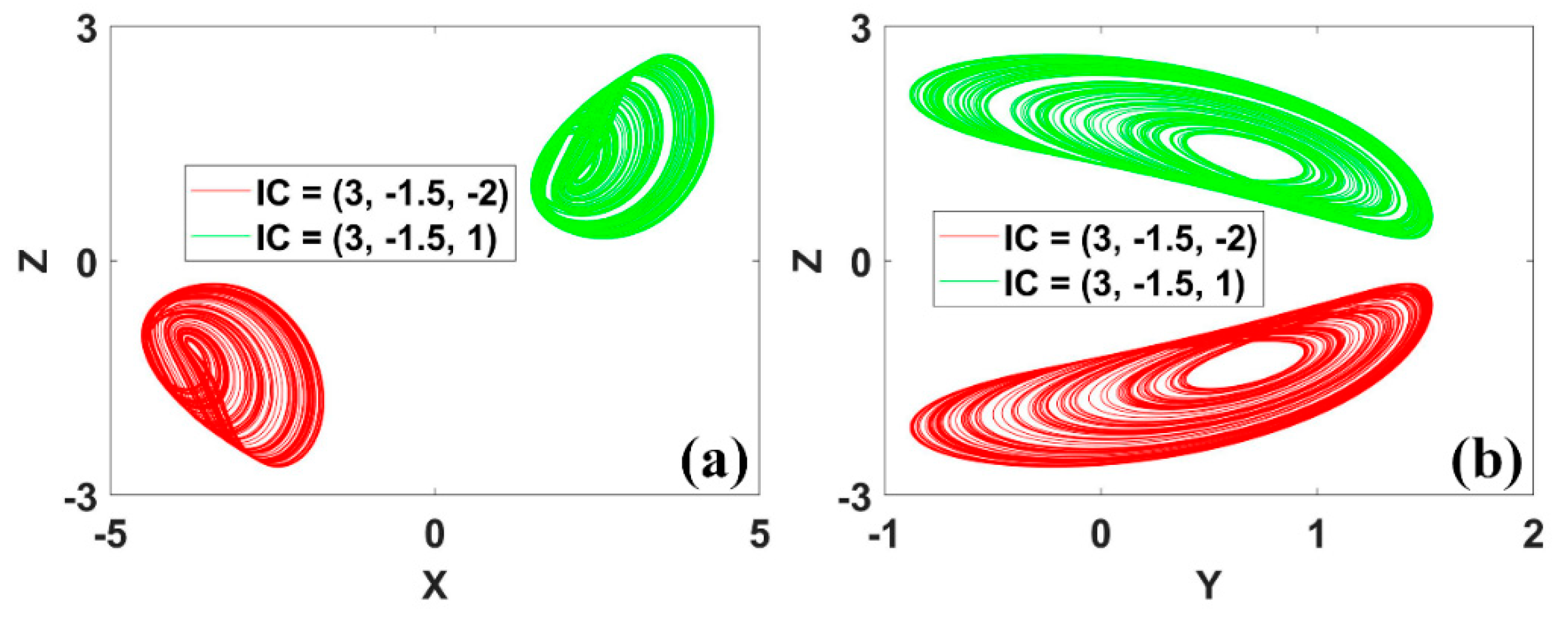

without influencing any of the other dimensions for polarity balance. Aim to this end, based on exhaustive researching, a chaotic system of conditional reflection symmetry was found as shown,

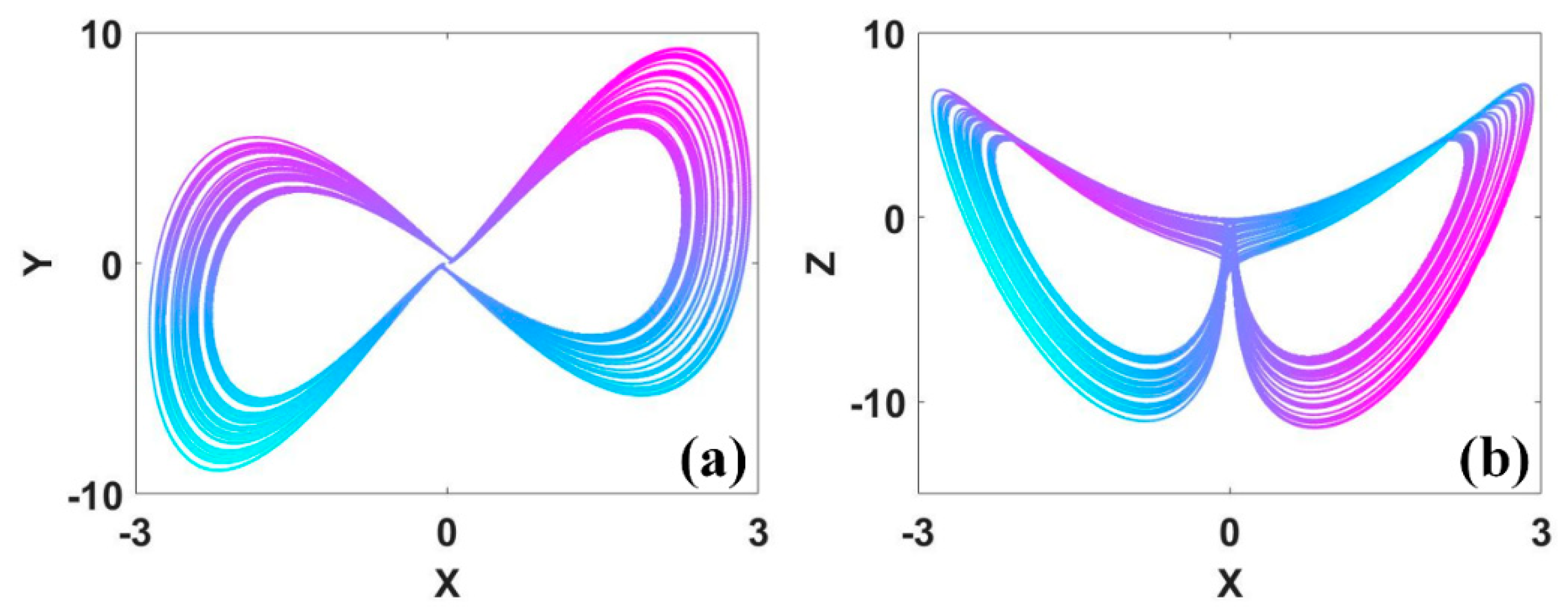

When

z gets the polarity reversed, the polarity of the last dimension is destroyed unless the function F(

x) = |

x|−3 get a reversed polarity to recover this balance. The polarity reverse of F(

x) is induced by the offset boosting of

x, that is to say, when

x →

x +

d, the first two dimensions do not change, but the function F(

x+d) turns to be −F(

x) since the absolute-value function has two reverse slopes during different position of its variable. The newly balanced polarity brings a pair of coexisting attractors across the

x and

z-axis in phase space, as shown in

Figure 15. We see that the direction of the attractor in the dimension of

x does not change but the direction in the dimension of

x does be overturned. Therefore, we can call this polarity balance as ‘one-jump polarity balance’.

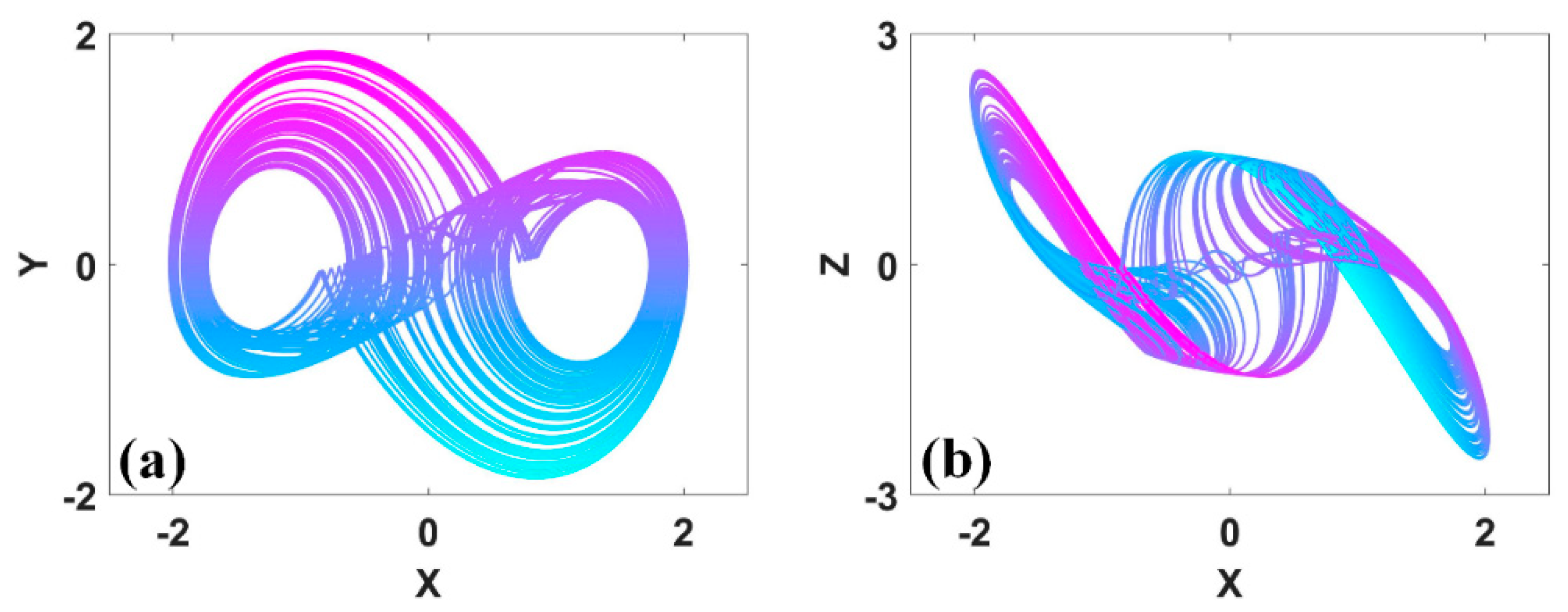

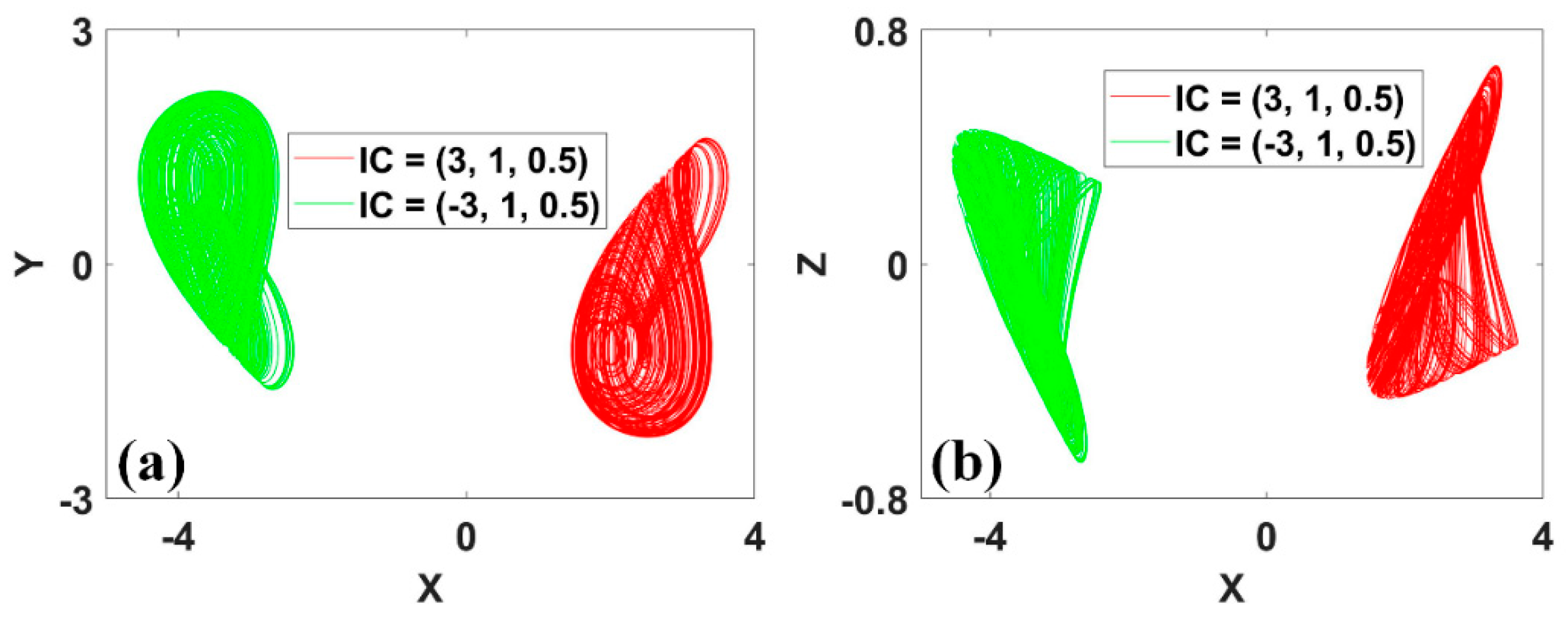

The ‘one-jump polarity balance’ can also happens in those rotational symmetric systems. As to system (11), here the polarity reverse in the dimension

y and

z breaks the polarity balance in the last dimension until the offset boosting of

x returns its balance without destroy the first dimension since adding a constant term does not change the value of the derivative. As shown in

Figure 16, this time the direction of coexisting attractors does not change in the

x-axis, but change both in the

y and

z dimension.

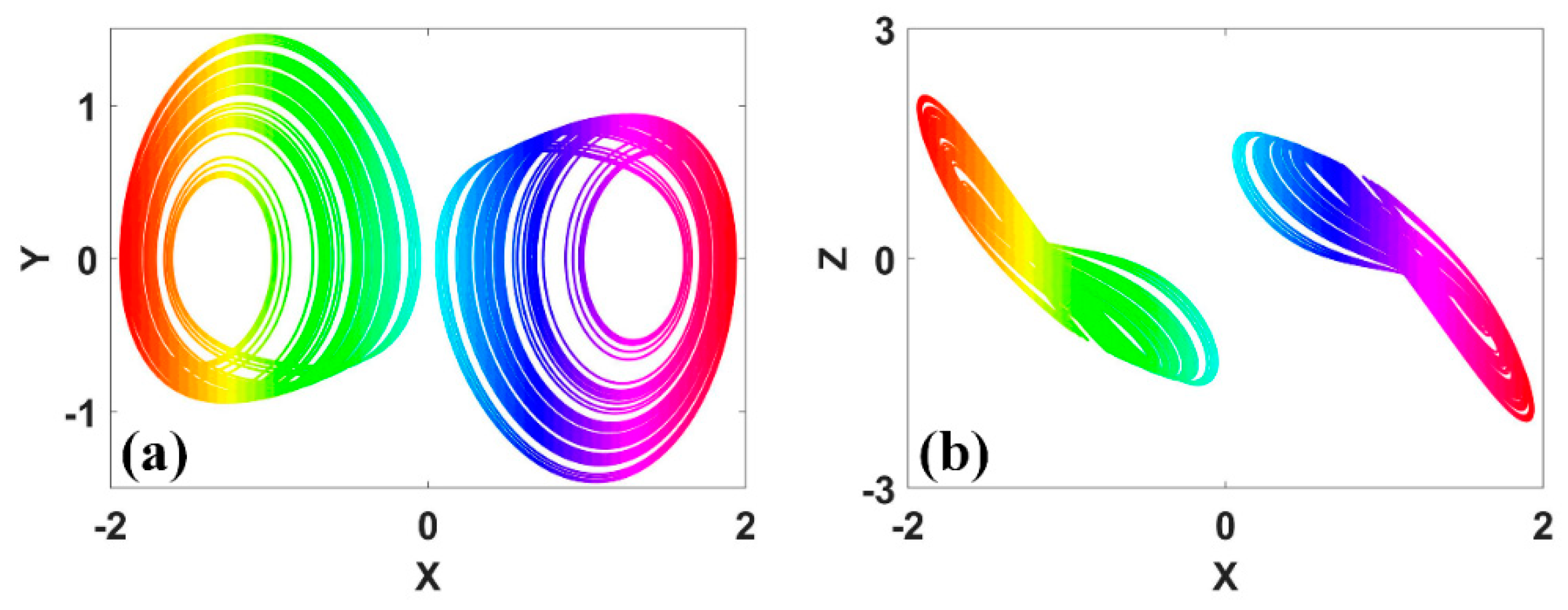

Sometimes, more operations of offset boosting are needed for balancing the polarity reverse of some of the variables. At this time, the conditional symmetry could be of ‘two-jump polarity balance’ or ‘more-jump polarity balance’. Like the system (12), here polarity reverse of

z is washed out by the offset boosting in the dimensions of

x and

y. This time, we can see that direction of the coexisting attractors does not change in the

x and

y dimension, but turn down in the

z-axis, as shown in

Figure 17. The ‘two-jump polarity balance’ may also happens in the same dimension and leave more variables for polarity reverse, as displayed in the system (13), here two variables get polarity reversed like

x and

y, but the polarity balance is returned by the offset boosting in the

z-dimension. The coexisting attractors, shown in

Figure 18, compared with those of system (12), system (13) has coexisting attractors with opposite directions in the dimension of

x and

y, but with the same direction in the

z-dimension.

More operations of offset boosting from the absolute-value functions could be introduced for recovering the polarity balance, such as in system (14), which contains six absolute-value functions for balancing the polarity reverse of the variable

x. As shown in

Figure 19, here the direction of the coexisting attractors in

x-dimension gets reversed, but does not change in the

y and

z dimension except the two-dimensional offset boosting. More interestingly, sometimes conditional symmetry may happen in symmetric systems. In this case, the offset boosting of some of the system variables also may return other types of conditional symmetry. As we know, the original version of system (15) is the simplified Lorenz system, but the two-dimensional offset boosting with

y and

z returns a conditional reflection symmetry, as shown in

Figure 20. Note that, it is interesting that system (5) is an asymmetric system now, although it has symmetric attractors in a conditional symmetric way, which means an asymmetric system may hosting symmetric attractors.

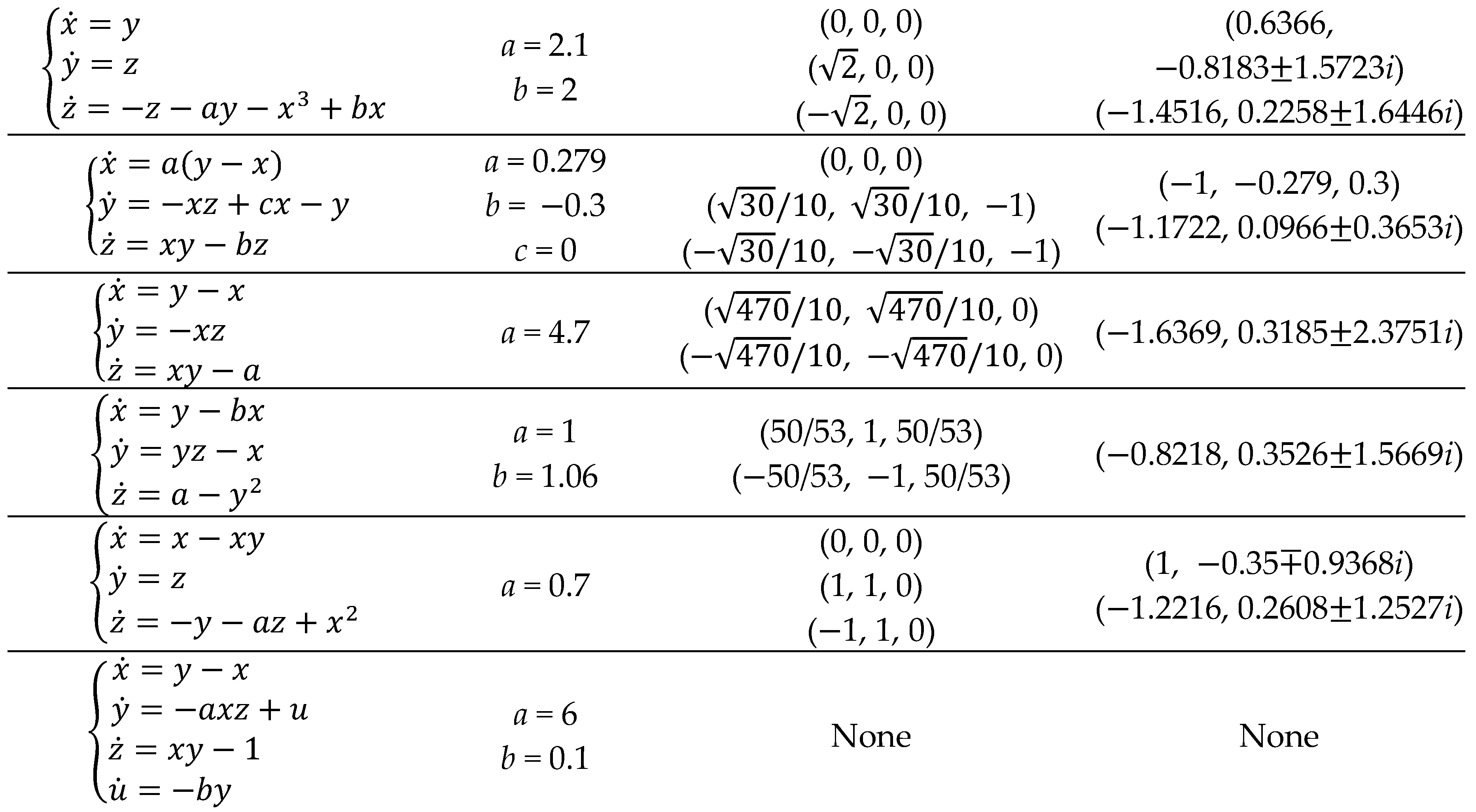

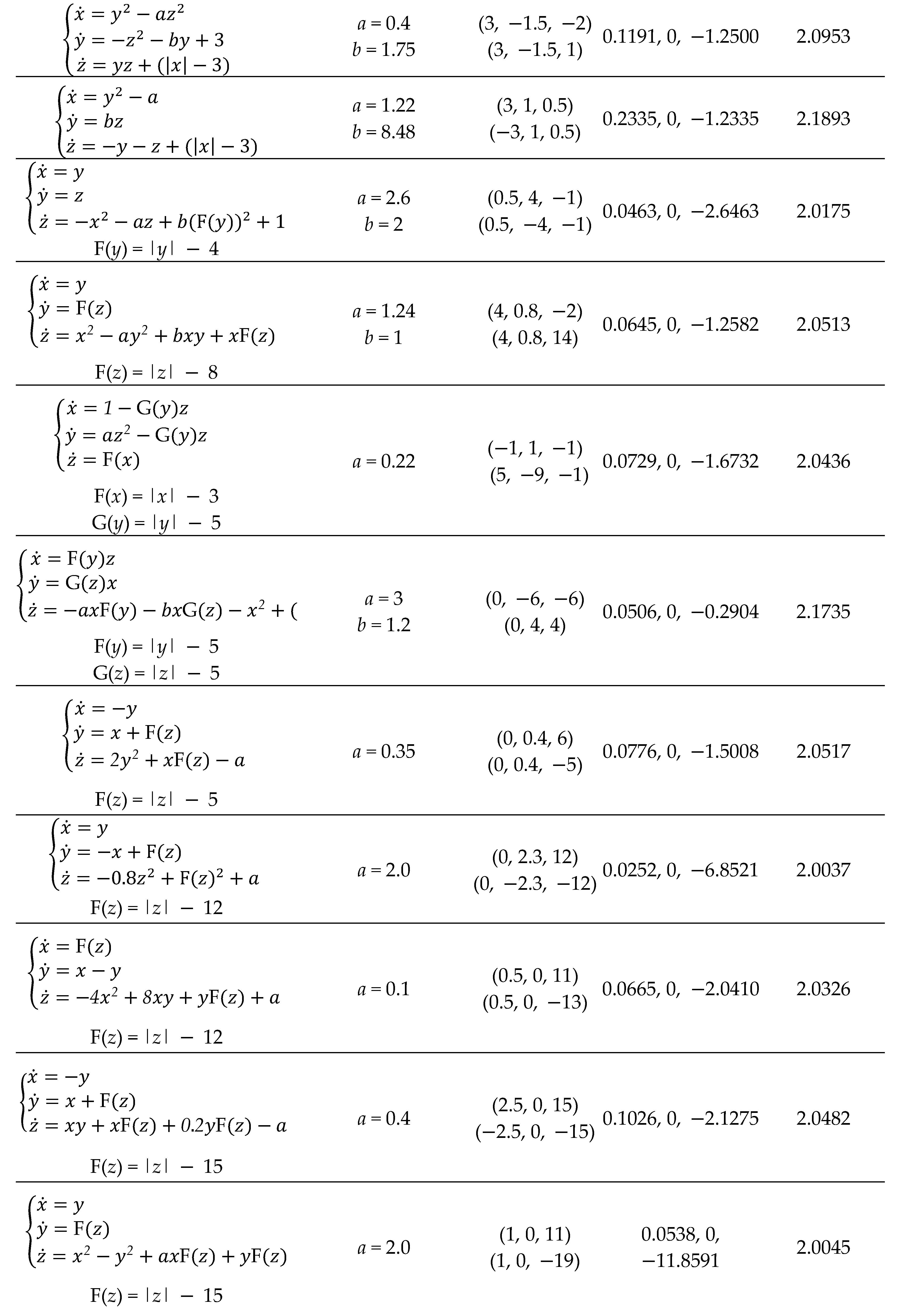

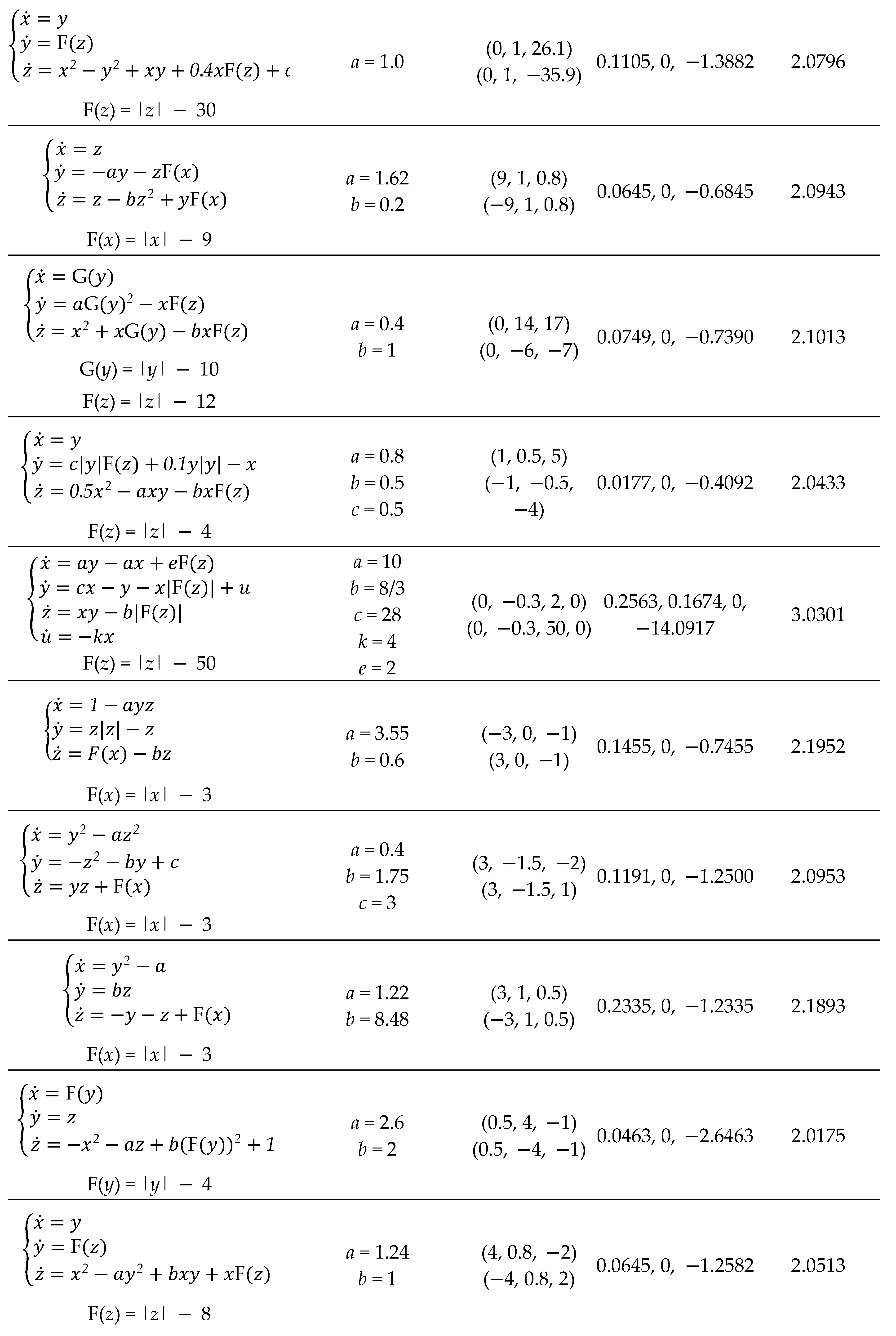

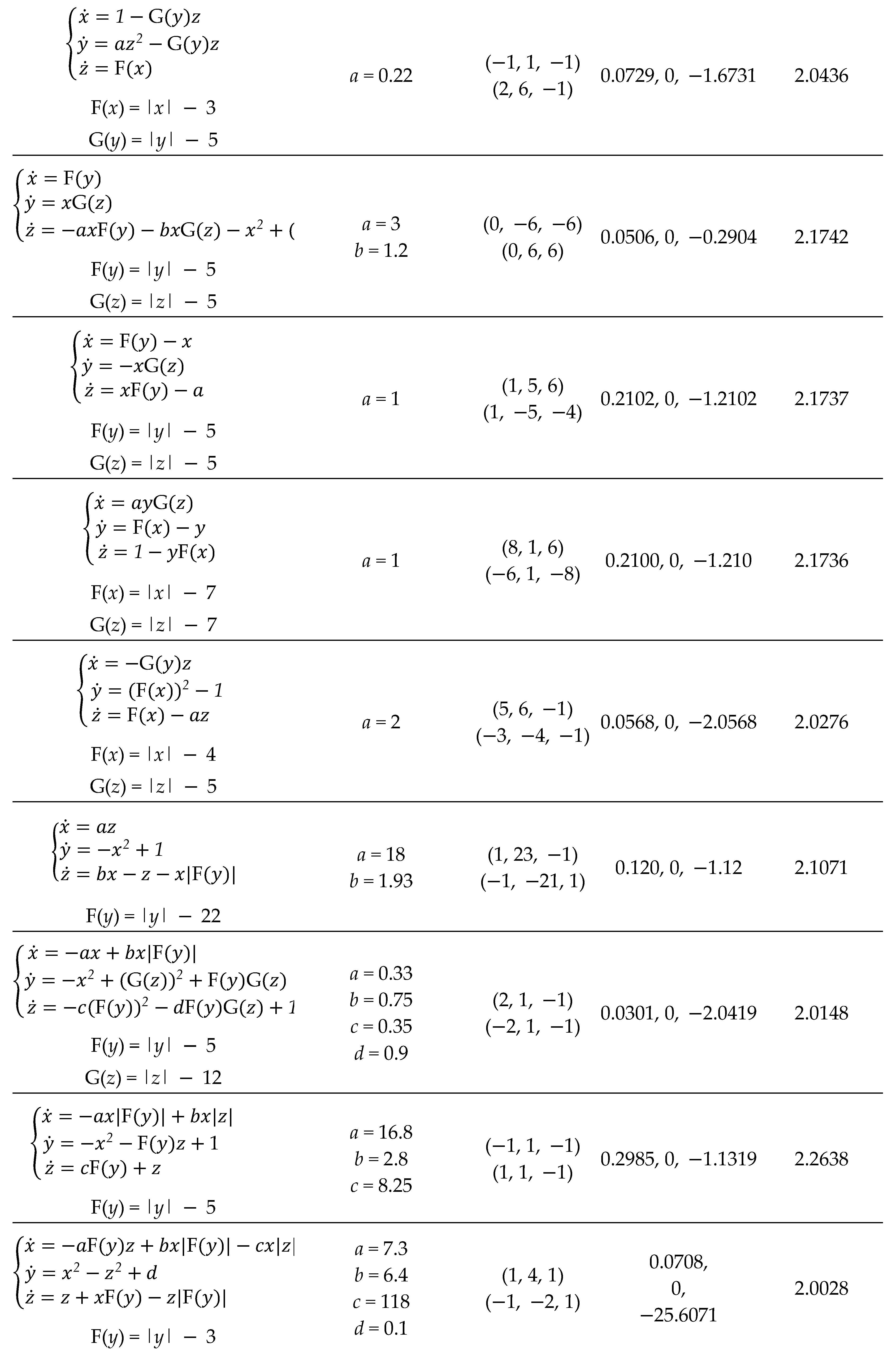

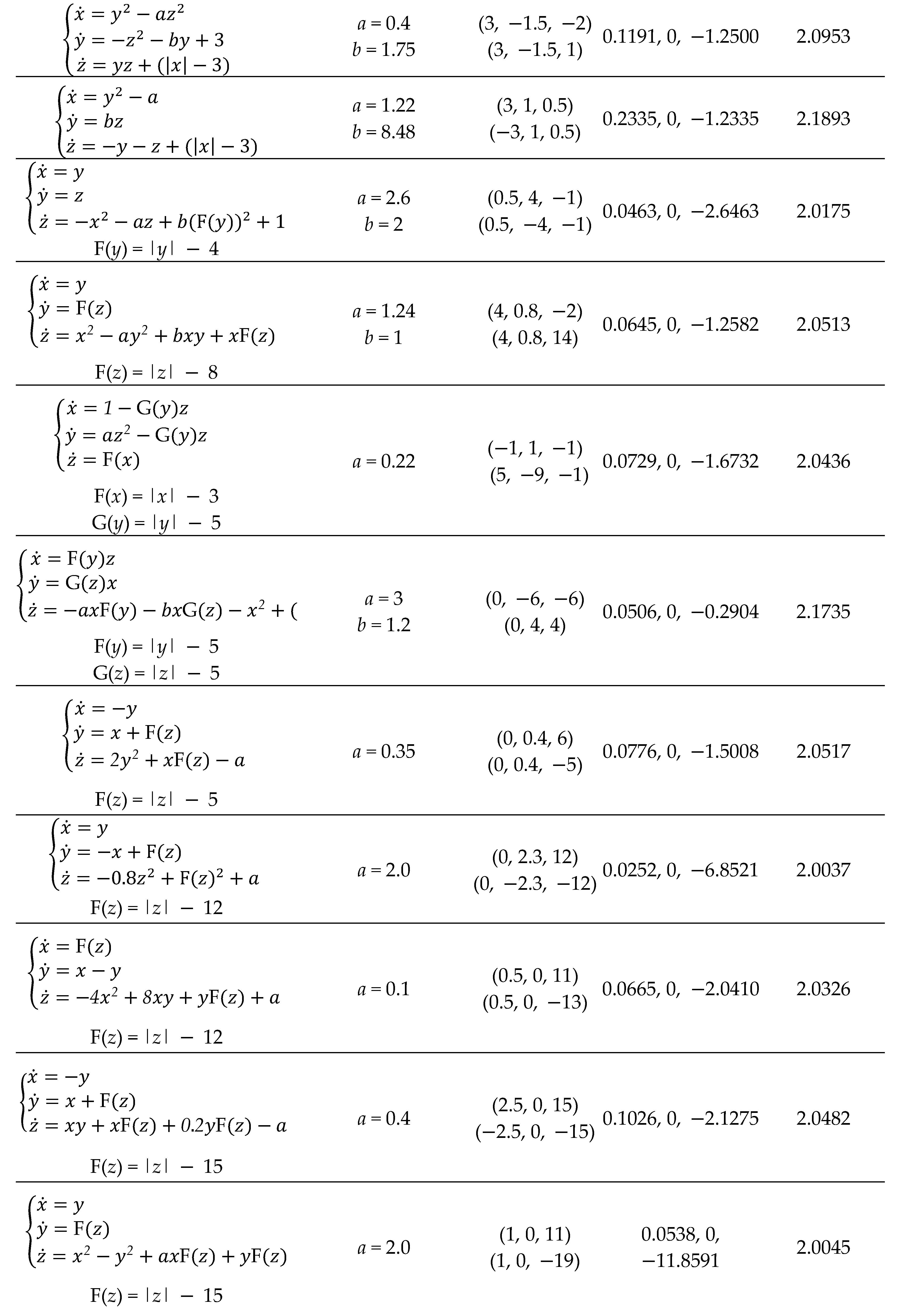

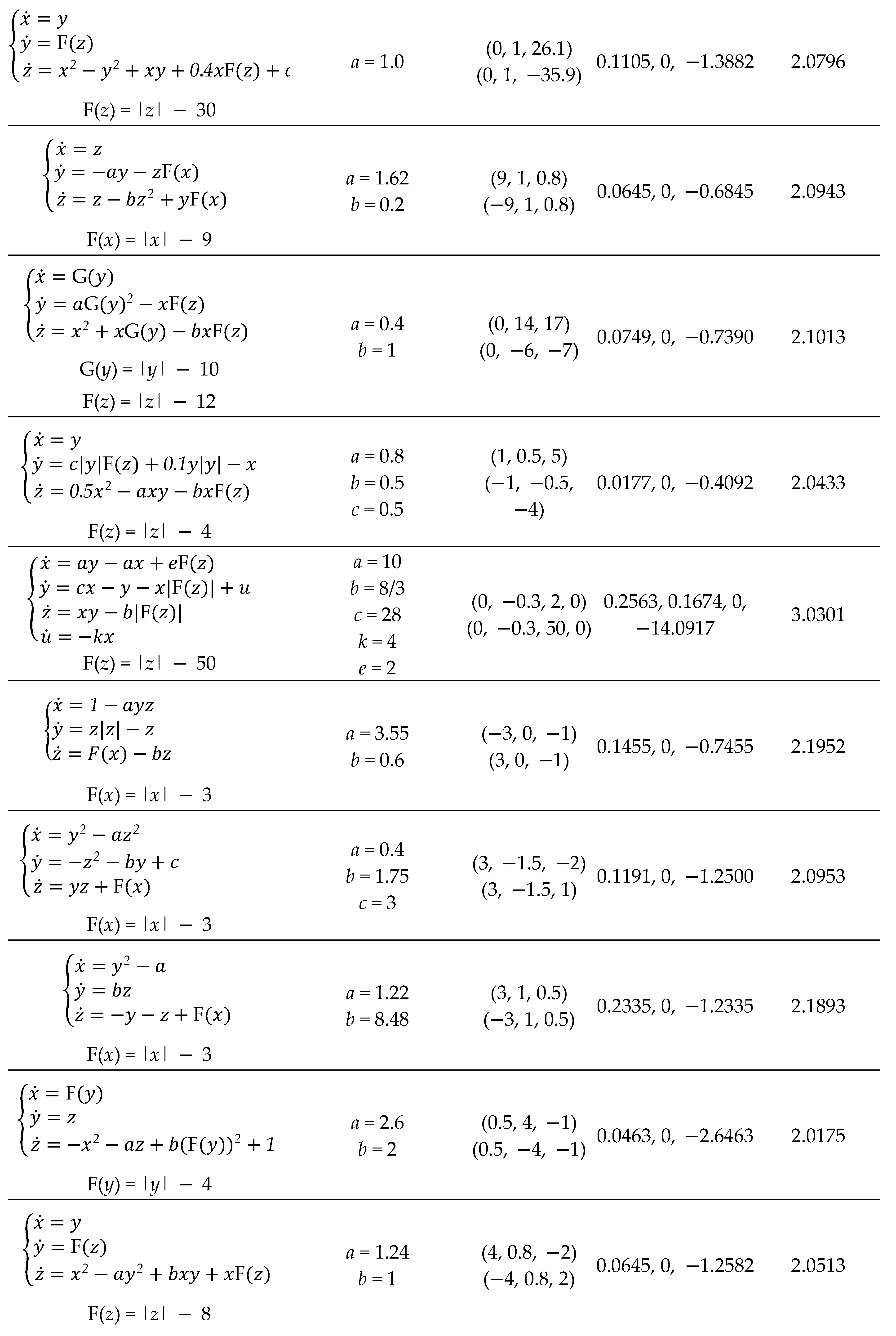

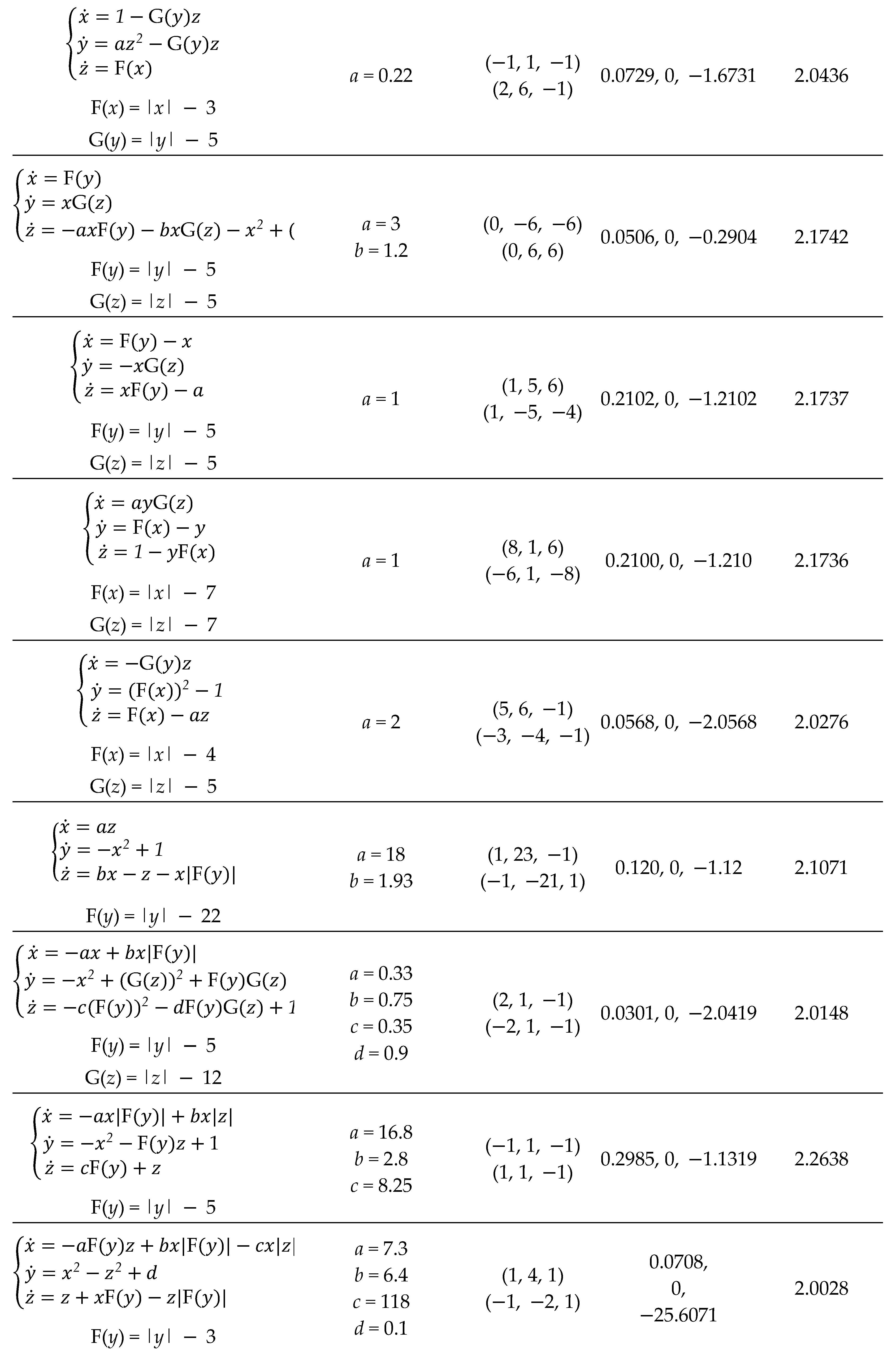

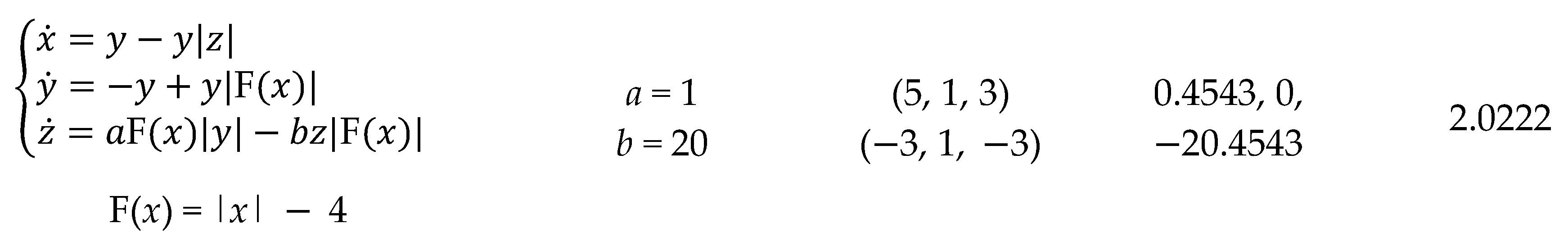

Many candidates of chaotic systems with coexisting attractors have been explored based on various system structures, such as those of chaotic system with hidden attractors [

40], those symmetric systems [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], as listed in Table. 2. Those system could be of symmetry, or asymmetry, or jerk system. Readers could check these systems to see if they are of polarity balance. Here the factors for polarity balance are from the system variables and also recovered by the absolute functions. The polarity broken is originated from the polarity reverse of some of the system variables, and the polarity balance is reconstructed by the internal polarity reverses of the absolute-value function. One absolute-value function introduces one time of polarity reverse by the offset boosting; multiple absolute-value functions drive multiple times of polarity jump of offset boosting. Those chaotic systems with amplitude control [

43] or other coexisting attractors [

44] may preserve this property since the polarity reverse induced by the offset boosting does not fundamentally change the system structure.

Table 2.

Chaotic systems of conditional symmetry proposed in [

6], [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]

Table 2.

Chaotic systems of conditional symmetry proposed in [

6], [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]

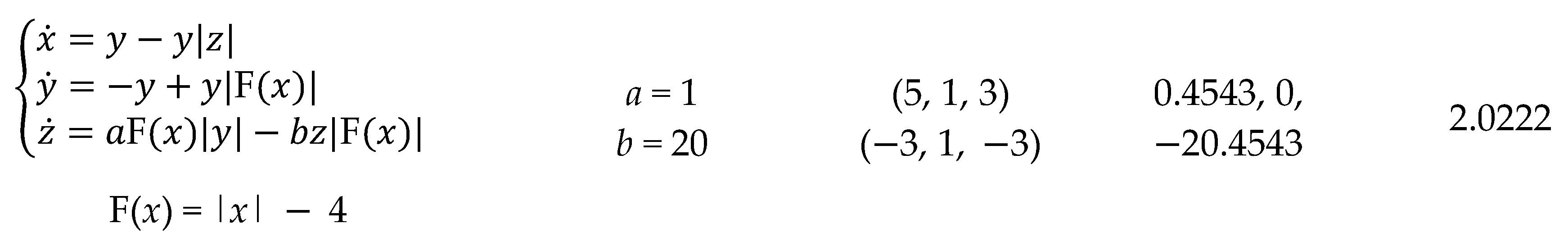

| Equations |

Parameters |

(x0, y0, z0) |

LEs |

DKY

|

|

|

|

|

From this view, the route for conditional symmetry is just drawing support from offset boosting to balance the destroyed polarity. The absolute value is just a polarity carrier for returning the polarity balance. The conditional symmetry is in fact a specific attractor rotation of offset dependence [

45] without rotation matrix, where conditional reflectional symmetry could be regarded as the attractor rotation of one-dimensional 180 degrees, namely antiphase rotation (could be regarded as from the first quadrant to the second quadrant); meanwhile the conditional rotational symmetry could be regarded as the attractor rotation of two-dimensional 135 degrees, namely anti-quadrant rotation (could be regarded as from the first quadrant to the third quadrant in a two-dimensional plane). In fact, more generally, the polarity balance may be recovered from any combinations of variable and its offset boosting. We can also conclude that even a 3D chaotic system of inversion symmetry can recover its polarity balance based on offset boosting, and such an additional selection of polarity balance can also be employed for repellor construction [

34]. As displayed in system TCSS6,

The offset boosting of the variables

x, y, and

z introduces polarity reverse for balancing the polarity destroyed from the variable of

t, and thus returning coexisting repellors, as shown in

Figure 21, here various operations of offset boosting of the variables return two repellors with conditional symmetry to the coexisting attractors.

The offset boosting within a trigonometric function, such as sinusoidal function or tangent function, can also balance the polarity reverse [

46] and thus reproducing infinitely many coexisting attractors of conditional symmetry [

39]. As appears in system (17),

Here the sinusoidal function of

x also brings a new polarity reverse and return the polarity balance in the last dimension of system (17), and thus introducing more coexisting attractors based on periodic offset boosting, as shown in

Figure 22. The flexible combinations of offset-boosting-oriented polarity reverse and variable polarity reverse lead to abundant candidates of chaotic systems with infinitely many coexisting attractors or repellors [

47].

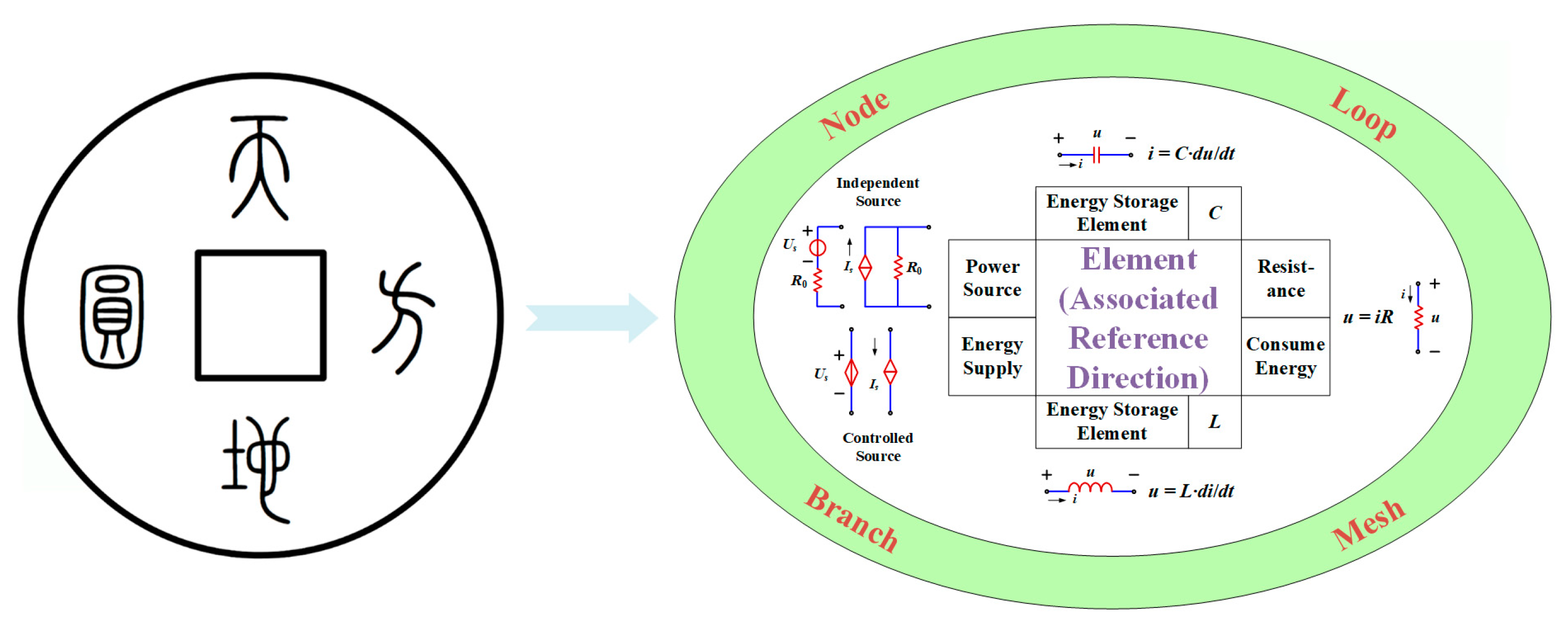

5. Symmetry and elegance in simple chaotic circuits

Furthermore, symmetry and conditional symmetry can be seen in the circuits. As we know, the restriction of voltage and current in a circuit is under the rule governed by the structure of circuit topology, and the individual characteristic of a circuit component. The structure of circuit topology gives the macro-restriction with the voltage and current, while the individual characteristic of a circuit component leads to a local micro-restriction. The former corresponds to the circuit law of Kirchhoff law, and the later is related the local restriction from a circuit element. All the circuit variables must obey the two types of constraints, but we still see that the constraint from the local component endows the flexibility in voltage and current values. Therefore, I call these two constraints with a Chinese Ancient philosophy vocabulary as ‘a square earth with a round sky above’, as shown in

Figure 23. The concept of ‘a square earth with a round sky above’ is the philosophical idea in ancient China, which is a manifestation of the theory of ‘Yin and Yang’. The sky and circle symbolize movement, but the earth and square represent stillness. In fact, the combination shows a balance of ‘yin and yang’ with the complementary movement and stillness. The concept of ‘round sky and square earth’ has been shown in ancient Chinese architecture, currency and other aspects, such as the Temple of Heaven, square hole coins and other patterns and structures.

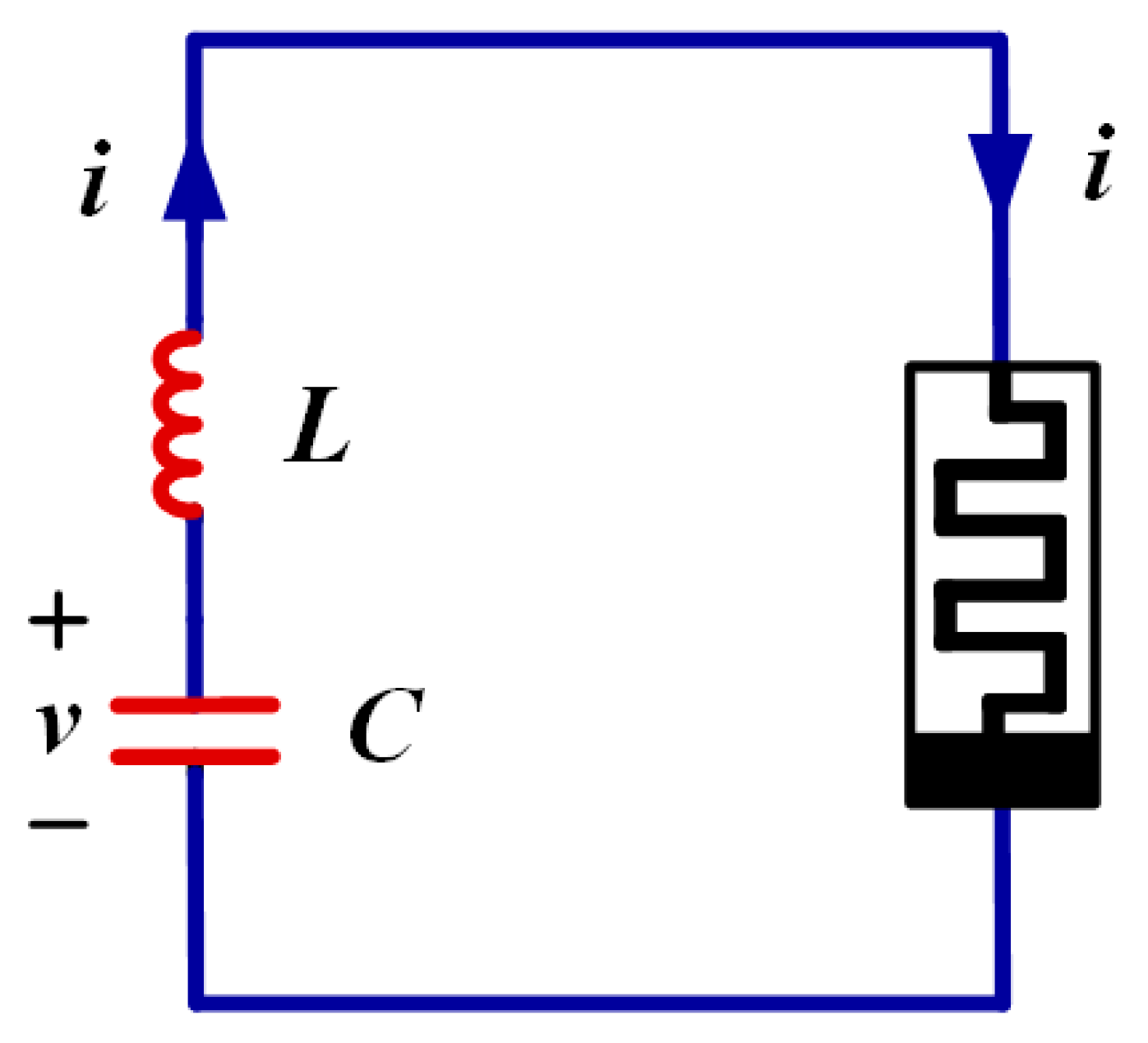

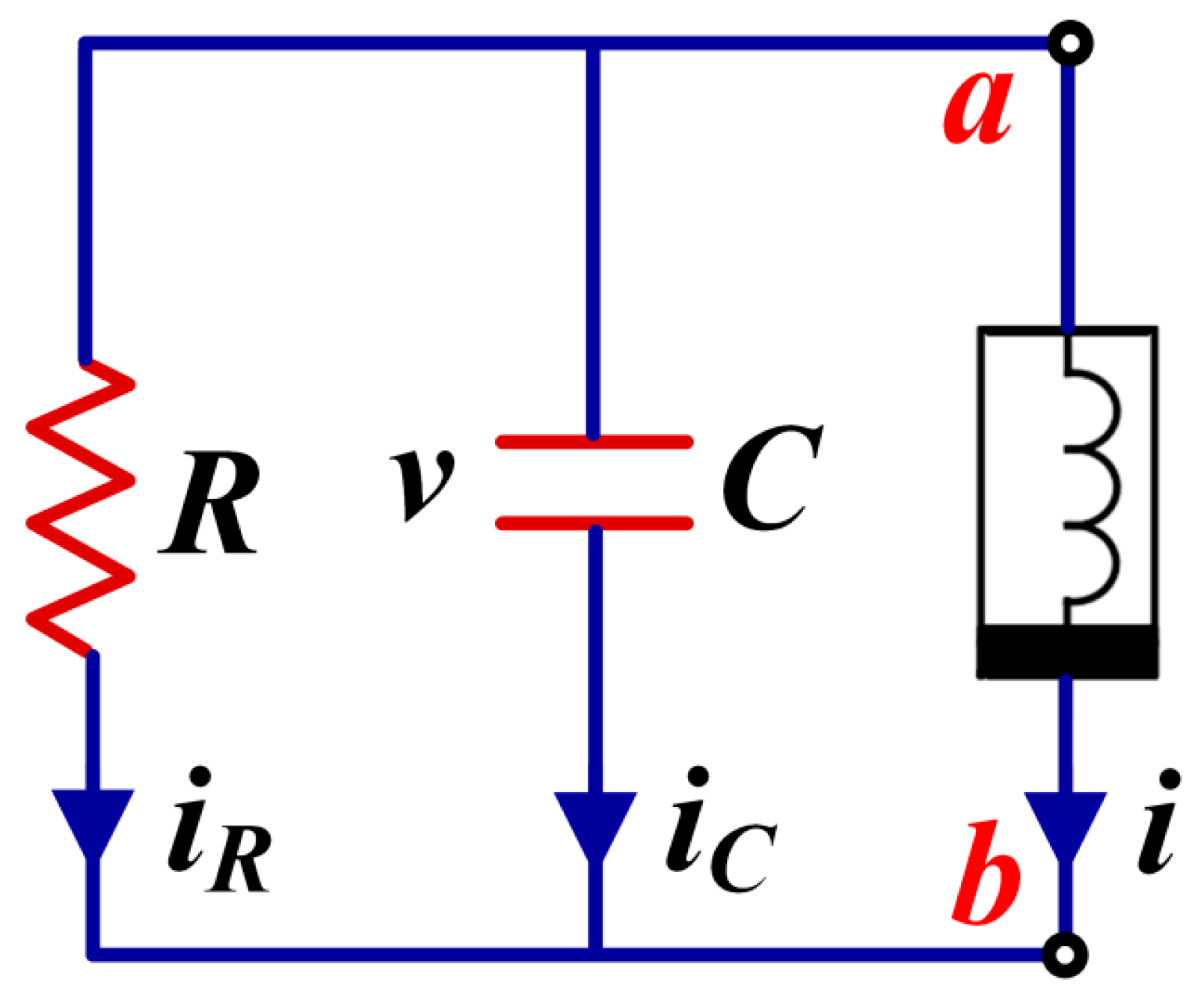

Moreover, in circuit, there are many cases of symmetry and duality. We can enumerate many circuit structures and corresponding circuit laws, such as capacitive and inductive components, voltage source and current source, series for voltage and parallel for current, series resonance and parallel resonance, time constant of resistor and capacitor and the time constant of conduction and inductance. Typically, many circuits of series structure could be transformed to be of parallel structure and give symmetric attractors or coexisting attractors of conditional symmetry. As shown

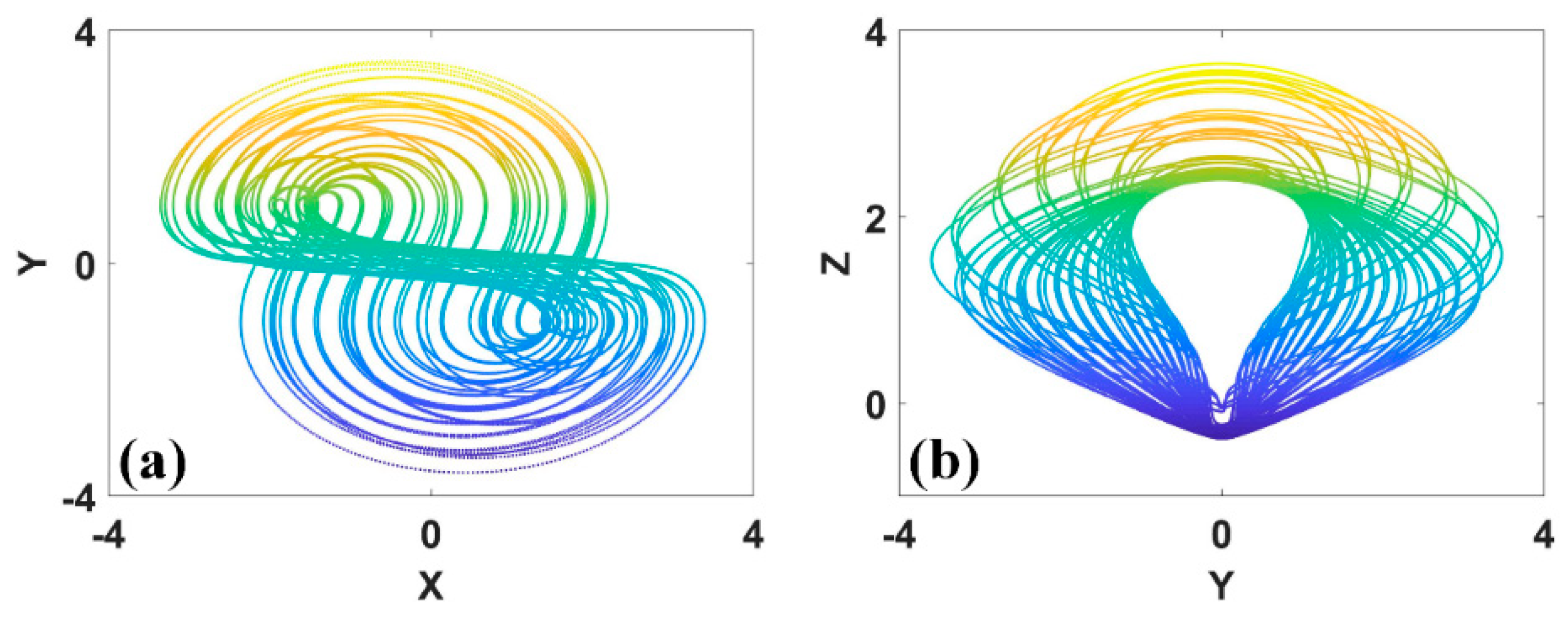

Figure 24, the simple series circuit [

48] including an inductor, a capacitor and a memristor can produce symmetric chaotic attractor, as show in

Figure 25. The circuit realizes the equation of system (18) with rotational symmetry according to the variables

y and

z.

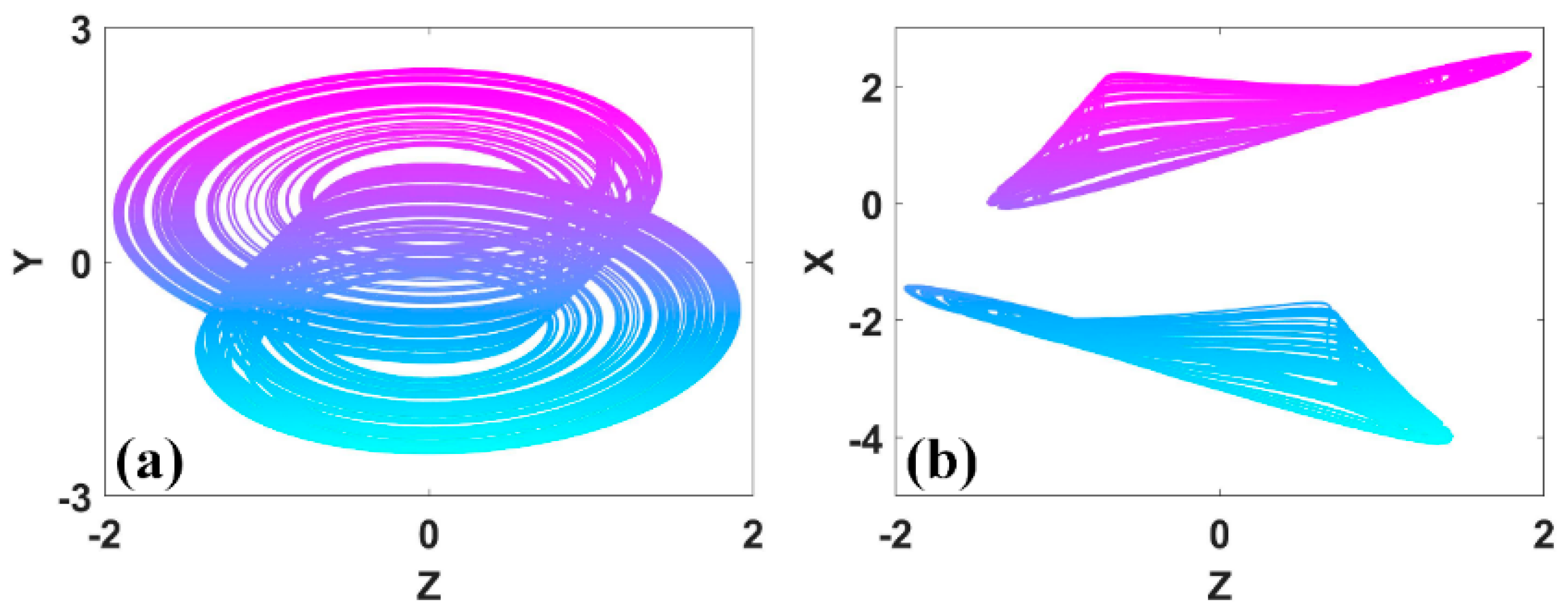

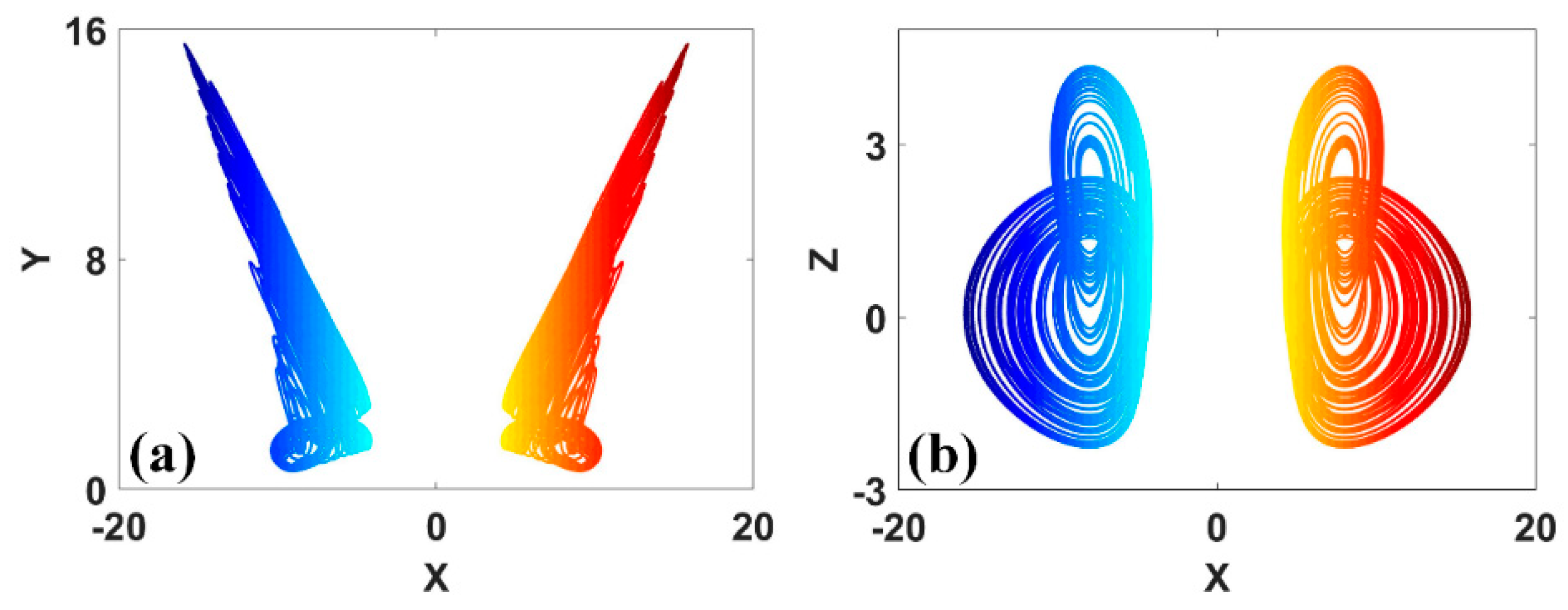

Conditional symmetry of coexisting attractors can also be generated in a simple parallel circuit structure [

49]. The chaotic system (19),

has coexisting chaotic attractors of rotational conditional symmetry when

a = 0.6,

b = 1,

c = 2, as displayed in

Figure 26. The structure of system (19) is unique, and can be implemented based on a parallel circuit with a capacitor, a resistor, and an meminductor, as shown in

Figure 27. This simple structure also oscillates outputting two coexisting attractors, as shown in

Figure 28. We can declare that people can realize these systems with a dual circuit structure if they want to switch the circuit between the series and parallel.

In fact, the elegant structure or symmetric property of a system does not indicate its simple or easy structure. For example, for doubling the coexisting attractors [

28,

29,

30], let’s see the system (20),

the coexisting attractors locate in phase space according to the axis of symmetry

x = 0. Here the constant

d modifies the distance between two coexisting symmetric attractors, when it increases from

d = 4.11 to be

d = 8, the distance between those symmetric attractors gets increased also, as shown in

Figure 29 and

Figure 30. Here the chaotic phase trajectories are elegant and simple, but the circuit for realizing them is not simple, typically it is realized based on three lines of operational-amplifier-based integral structure [

27], [

50].

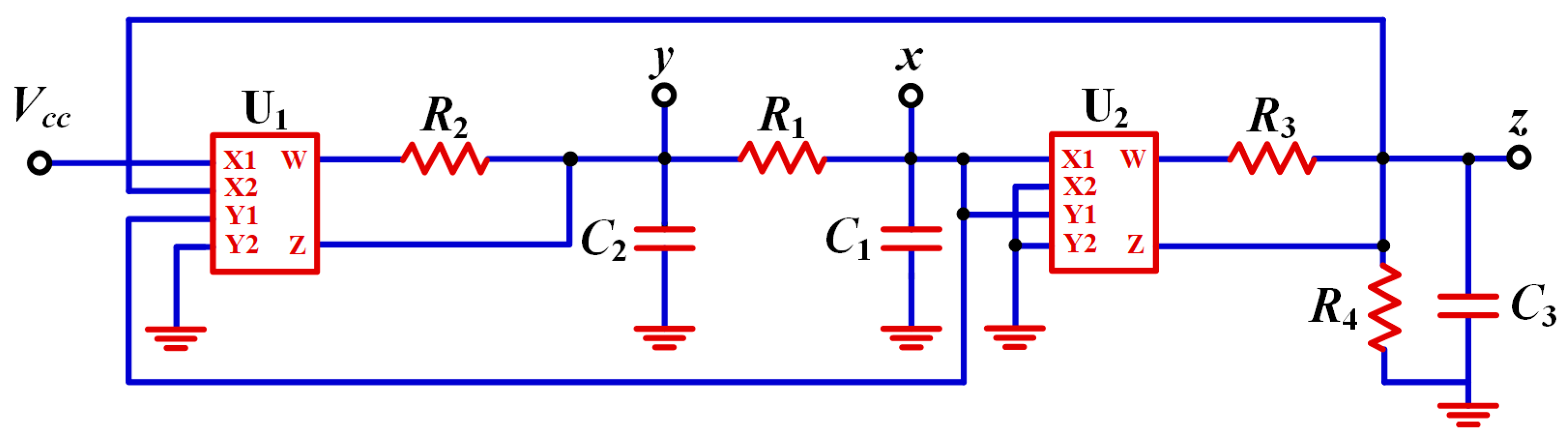

For many of those symmetric chaotic systems, the simple circuit could be constructed by utilizing the inherent characteristics of a multiplier and the differential constraint of the capacitor [

51]. As we know, the multiplier AD633 can convert voltage to current by an external resistor. The external voltage transformation characteristic of AD633 obeys the relationship of

. If a resistor connects the output point W and Z in series, as shown in

Figure 31(a), the output current satisfies

0 and

for a large input resistor of the Z port with a small input current. Thus, the output voltage satisfies the balance of current:

. Consequently, the current associated with AD633 subject to

. Various combinations of inputs realize those terms with different degrees according to the input variable, and therefore, a multiplier provides the linear terms and quadratic terms for circuit calculation. Furthermore, the connection of resistor and capacitor drives flexible integration calculation. When two capacitors are coupled with a resistor as shown in

Figure 31(b), the current

identified by

equals the current through the capacitor

resulting in

, and similarly leads to the symmetric restraint like

. When a capacitor and a resistor connect in parallel, the current equation is

. From the above two class of basic circuit constraints, many symmetric chaotic systems with quadratic terms could be implemented in an easy way. Like the system, written as,

it can be realized with a compact structure, as shown in

Figure 32.

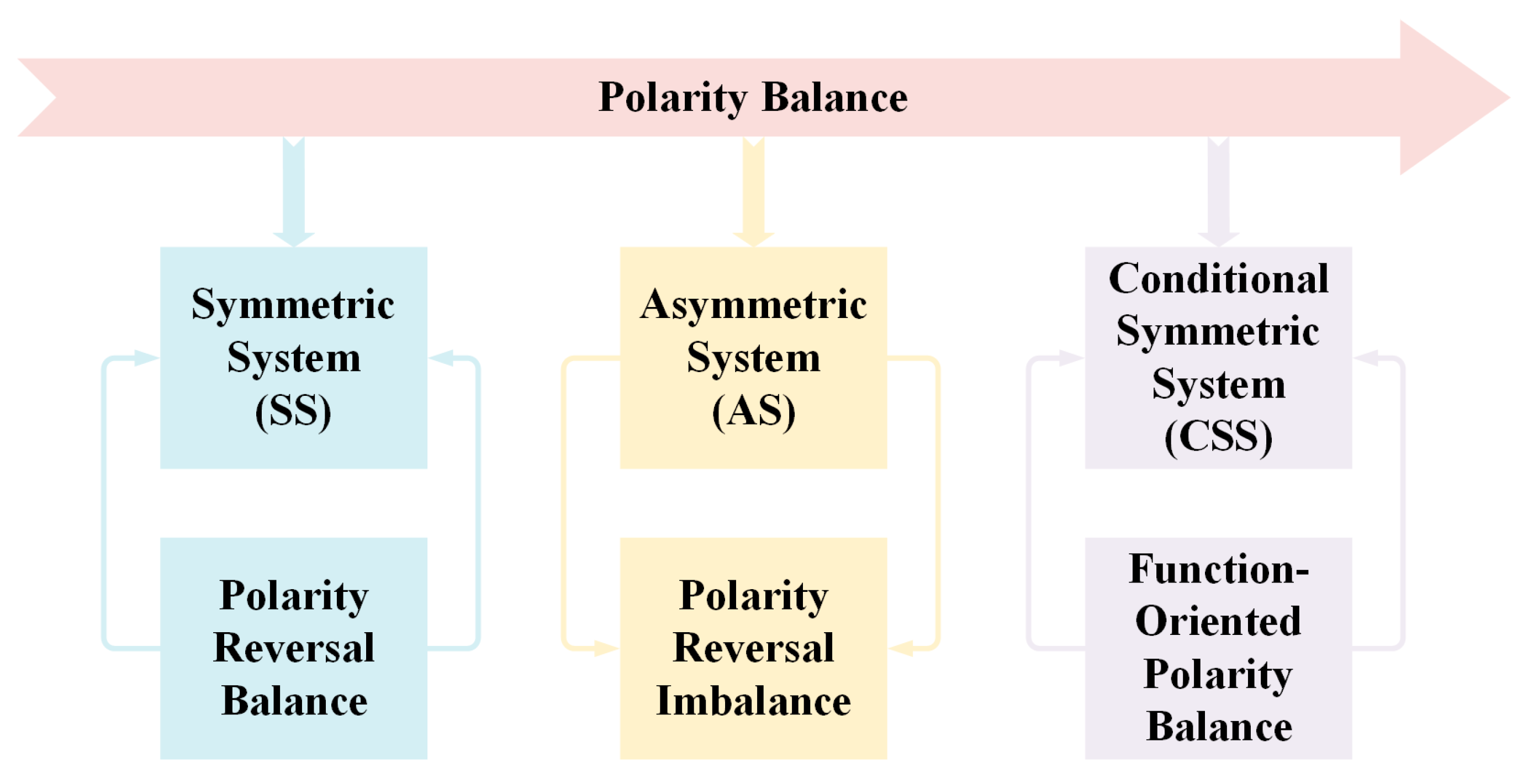

Figure 1.

Symmetry, asymmetry and conditional symmetry in chaotic systems.

Figure 1.

Symmetry, asymmetry and conditional symmetry in chaotic systems.

Figure 2.

Attractor of rotational symmetry in system (1) when σ = 0.279, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC = (−0.1, 0.1, −2): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 2.

Attractor of rotational symmetry in system (1) when σ = 0.279, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC = (−0.1, 0.1, −2): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

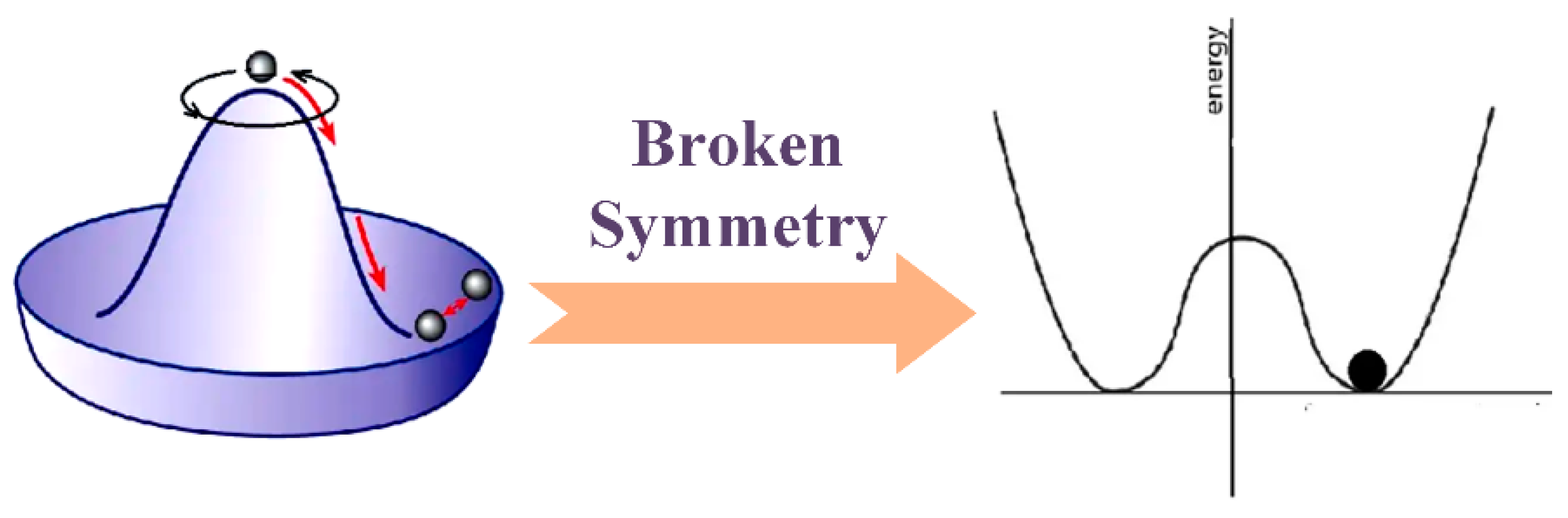

Figure 3.

Symmetric solutions under the broken symmetry.

Figure 3.

Symmetric solutions under the broken symmetry.

Figure 4.

Symmetric pair of attractors with rotational symmetry in system (1) under the parameters σ = 0.256, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC1 = (−0.1, 0.1, −2) (left), IC2 = (0.1, −0.1, −2) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 4.

Symmetric pair of attractors with rotational symmetry in system (1) under the parameters σ = 0.256, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC1 = (−0.1, 0.1, −2) (left), IC2 = (0.1, −0.1, −2) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 5.

Coexisting strange attractors of system (1) when σ = 0.279, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC1 = (−0.1, 0.1, −2) (blue), IC2 = (−0.1, 0.1, −14) (cyan), IC3 = (0.1, −0.1, −14) (purple): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 5.

Coexisting strange attractors of system (1) when σ = 0.279, r = 0, b = −0.3 and IC1 = (−0.1, 0.1, −2) (blue), IC2 = (−0.1, 0.1, −14) (cyan), IC3 = (0.1, −0.1, −14) (purple): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 6.

Symmetric attractor of inversion symmetry in system (2) when a = 1.7, b = 2 and IC = (1, 0, 0): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 6.

Symmetric attractor of inversion symmetry in system (2) when a = 1.7, b = 2 and IC = (1, 0, 0): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 7.

A symmetric pair of coexisting attractors in system (2) when a = 2.1, b = 2 and IC1 = (−1, 0, 0) (left), IC2 = (1, 0, 0) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 7.

A symmetric pair of coexisting attractors in system (2) when a = 2.1, b = 2 and IC1 = (−1, 0, 0) (left), IC2 = (1, 0, 0) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 8.

Attractor of reflection invariant system (3) with a = 0.35 and IC = (−2, 2, 0): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 8.

Attractor of reflection invariant system (3) with a = 0.35 and IC = (−2, 2, 0): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 9.

A symmetric pair of attractors in reflection invariant system (3) with a = 0.7 and IC1 = (−2, 2, 0) (left), IC2 = (2, 2, 0) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 9.

A symmetric pair of attractors in reflection invariant system (3) with a = 0.7 and IC1 = (−2, 2, 0) (left), IC2 = (2, 2, 0) (right): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 10.

Quasi-periodic torus coexisting with a symmetric pair of chaotic attractors at a = 6, b = 0.1 (red and blue attractors correspond to two symmetric initial conditions under IC = (0, ±4, 0, ∓5), cyan is for symmetric torus under IC = (1, −1, 1, −1)): (a) x-z, (b) y-z.

Figure 10.

Quasi-periodic torus coexisting with a symmetric pair of chaotic attractors at a = 6, b = 0.1 (red and blue attractors correspond to two symmetric initial conditions under IC = (0, ±4, 0, ∓5), cyan is for symmetric torus under IC = (1, −1, 1, −1)): (a) x-z, (b) y-z.

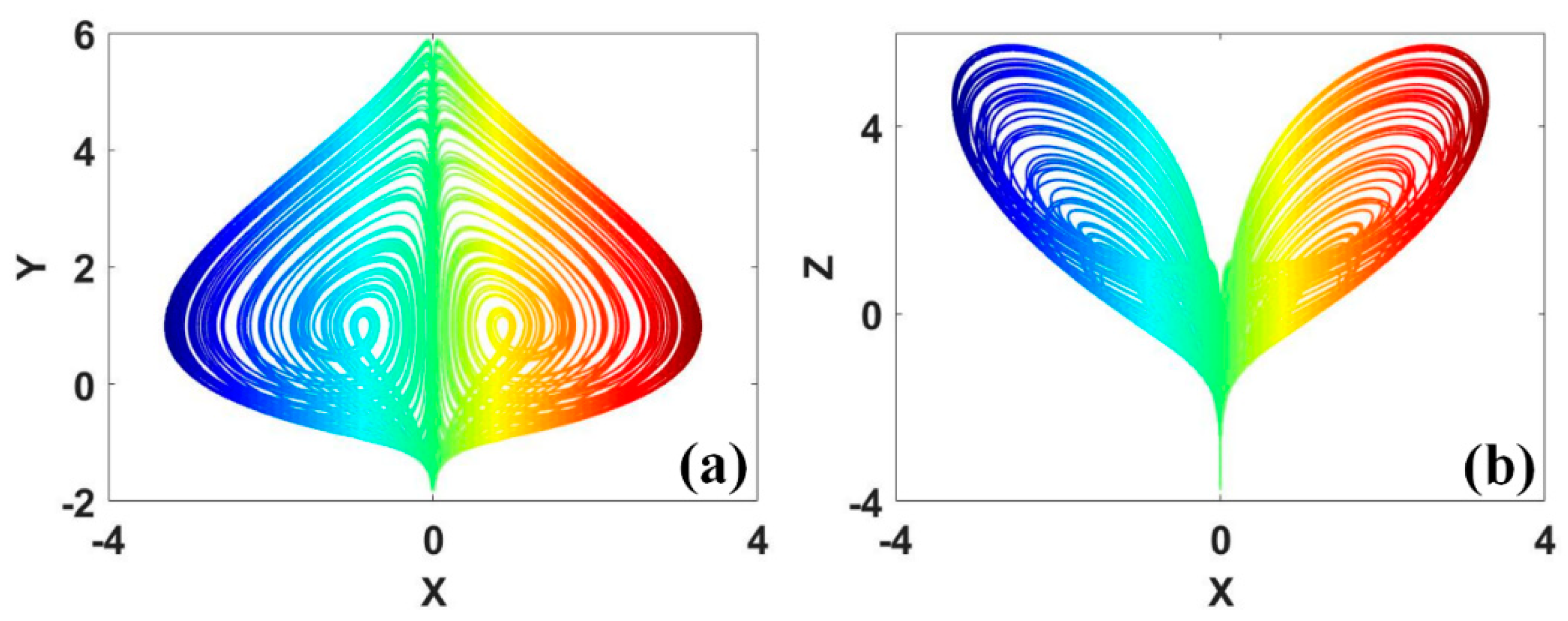

Figure 11.

Symmetric attractors of system (8) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d = 0 and IC1 = (−9, 0, 2) (up), IC2 = (−9, 0, −2) (down): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 11.

Symmetric attractors of system (8) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d = 0 and IC1 = (−9, 0, 2) (up), IC2 = (−9, 0, −2) (down): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 12.

Symmetric attractors of system (8) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d = 12 and IC1 = (−9, 0, 12) (up), IC2 = (−9, 0, −12) (down): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 12.

Symmetric attractors of system (8) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d = 12 and IC1 = (−9, 0, 12) (up), IC2 = (−9, 0, −12) (down): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

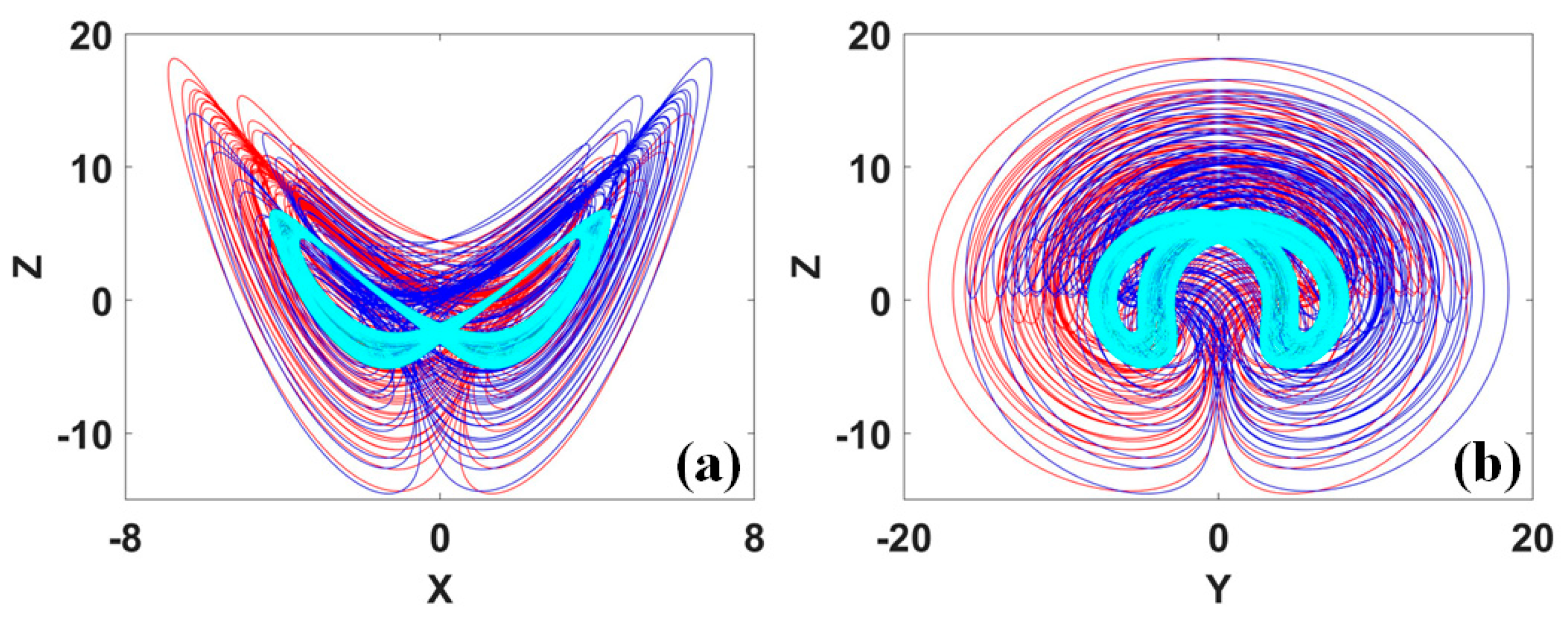

Figure 13.

Eight coexisting attractors of system (9) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d1 = 11, d2 = 13, d3 = 12.

Figure 13.

Eight coexisting attractors of system (9) with a = b = 0.2, c = 6.5, d1 = 11, d2 = 13, d3 = 12.

Figure 14.

Polarity balance in a dynamical system.

Figure 14.

Polarity balance in a dynamical system.

Figure 15.

Coexisting conditional reflection symmetric attractors of system (10) with IC1 = (3, −1.5, −2) (red), IC2 = (3, −1.5, 1) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 15.

Coexisting conditional reflection symmetric attractors of system (10) with IC1 = (3, −1.5, −2) (red), IC2 = (3, −1.5, 1) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 16.

Coexisting conditional rotational symmetric attractors of system (11) with IC1 = (3, 1, 0.5) (red), IC2 = (−3, 1, 0.5) (green): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 16.

Coexisting conditional rotational symmetric attractors of system (11) with IC1 = (3, 1, 0.5) (red), IC2 = (−3, 1, 0.5) (green): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

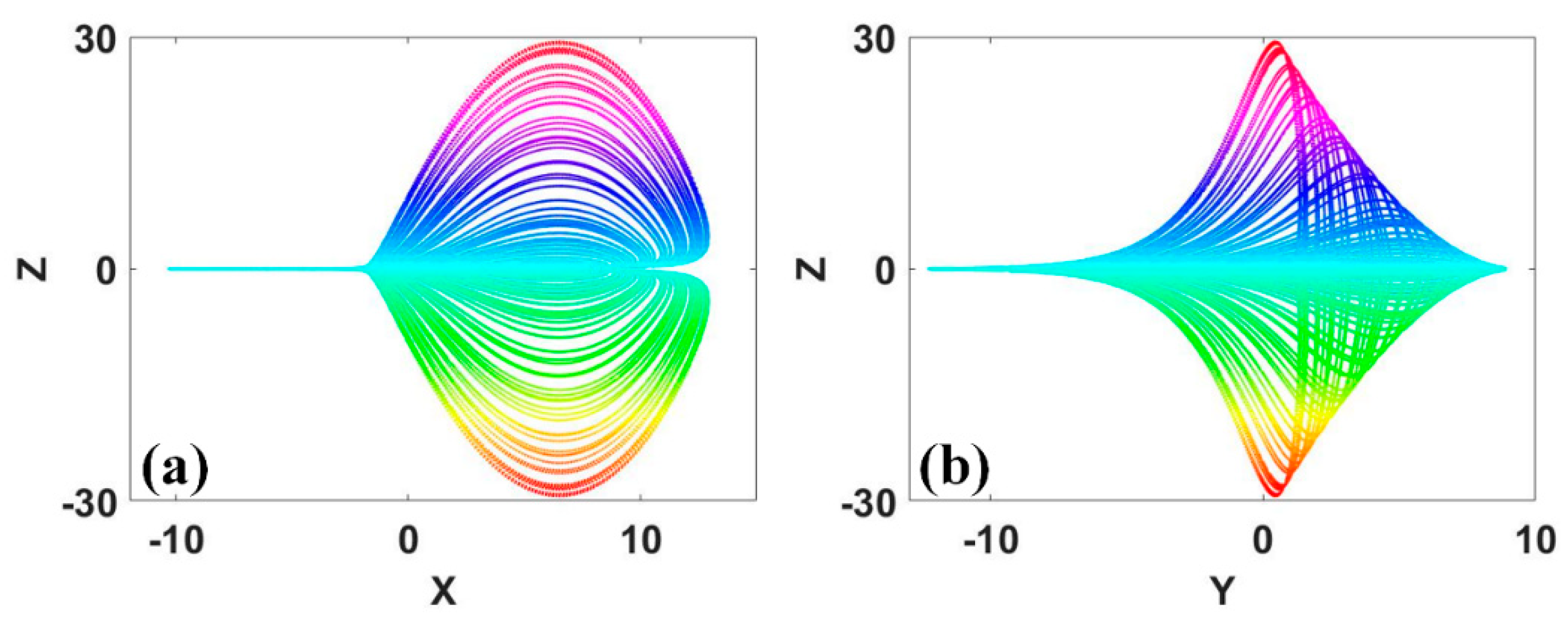

Figure 17.

Coexisting attractors in system (12) by 2D offset boosting, when a = 0.22 and IC1 = (2, 6, −1) (red), IC2 = (−1, 1, −1) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 17.

Coexisting attractors in system (12) by 2D offset boosting, when a = 0.22 and IC1 = (2, 6, −1) (red), IC2 = (−1, 1, −1) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

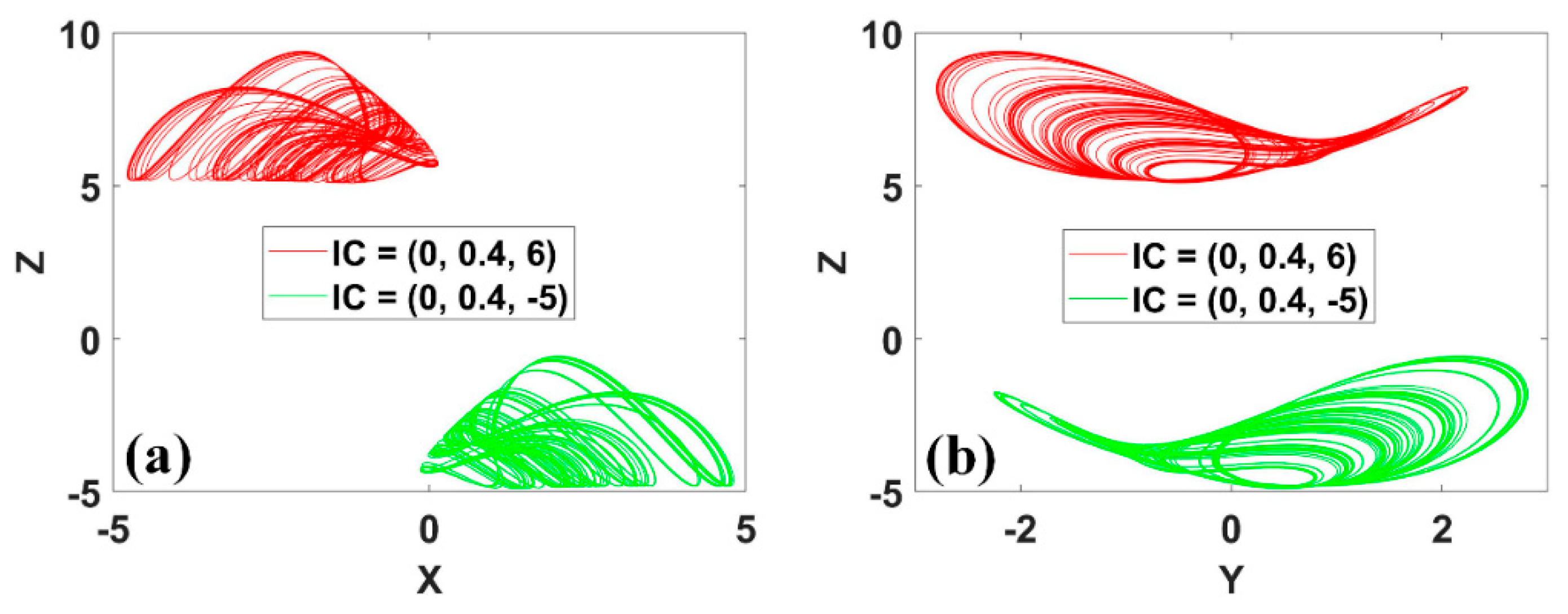

Figure 18.

Coexisting conditional rotational symmetric attractors of system (13) with a = 0.35, IC1 = (0, 0.4, 6) (red), IC2 = (0, 0.4, −5) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 18.

Coexisting conditional rotational symmetric attractors of system (13) with a = 0.35, IC1 = (0, 0.4, 6) (red), IC2 = (0, 0.4, −5) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

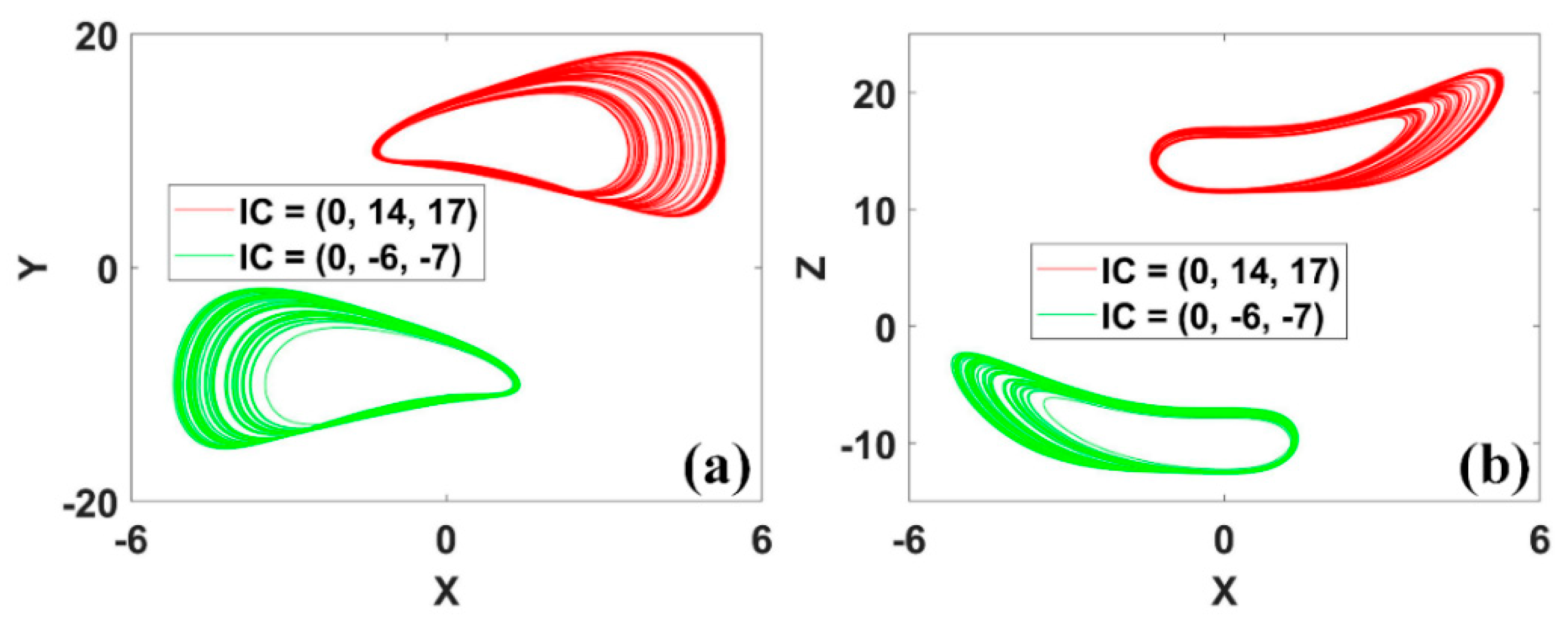

Figure 19.

Coexisting attractors in conditional symmetric system (14) with a = 0.4, b = 1, IC1 = (0, 14, 17) (red), IC2 = (0, −6, −7) (green): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 19.

Coexisting attractors in conditional symmetric system (14) with a = 0.4, b = 1, IC1 = (0, 14, 17) (red), IC2 = (0, −6, −7) (green): (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 20.

Coexisting attractors in symmetric system (15) with IC1 = (1, 5, 5.5) (red), IC2 = (1, −5, −4.5) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

Figure 20.

Coexisting attractors in symmetric system (15) with IC1 = (1, 5, 5.5) (red), IC2 = (1, −5, −4.5) (green): (a) x−z, (b) y−z.

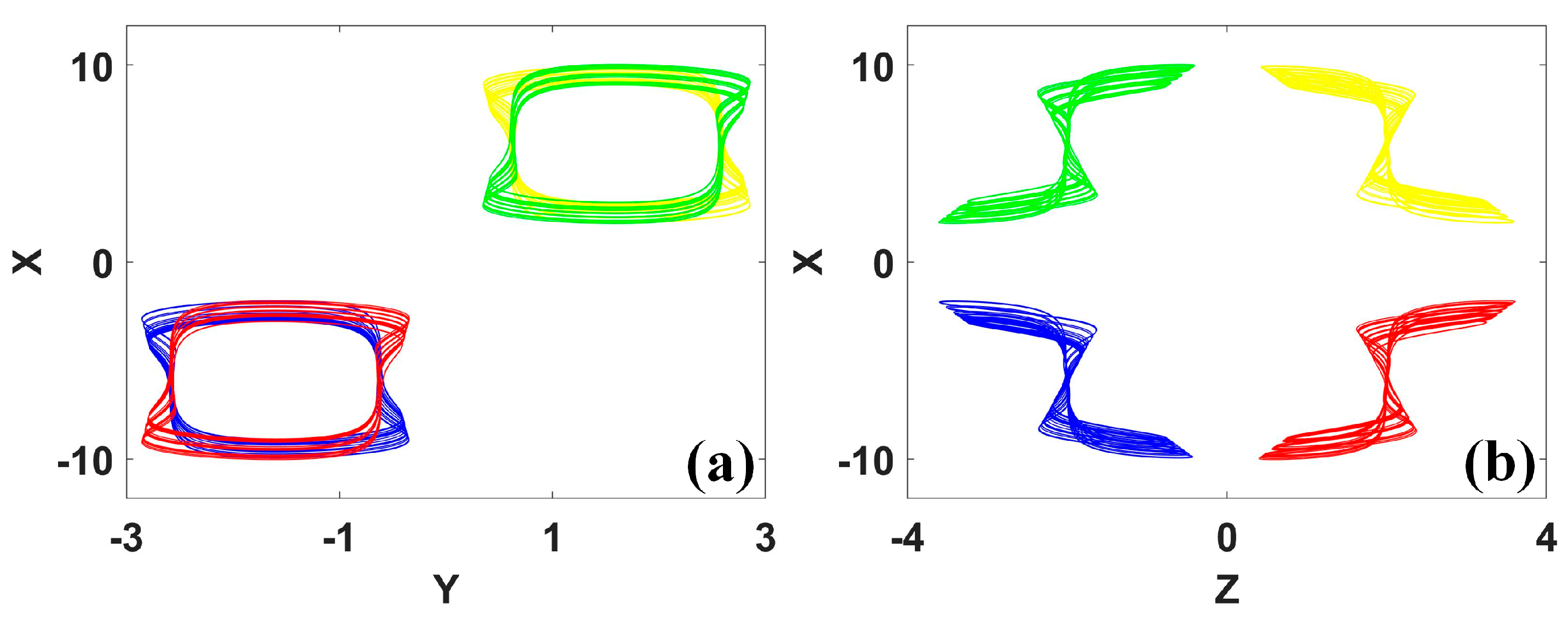

Figure 21.

Coexisting repellors with conditional symmetry in system (16): (a) y−x, (b) z−x. (IC = (0, 0.96, 0) is red, IC = (6, 2, 2) is yellow, IC = (0, −0.96, 0) is green, IC = (−6, −2, −2) is blue.)

Figure 21.

Coexisting repellors with conditional symmetry in system (16): (a) y−x, (b) z−x. (IC = (0, 0.96, 0) is red, IC = (6, 2, 2) is yellow, IC = (0, −0.96, 0) is green, IC = (−6, −2, −2) is blue.)

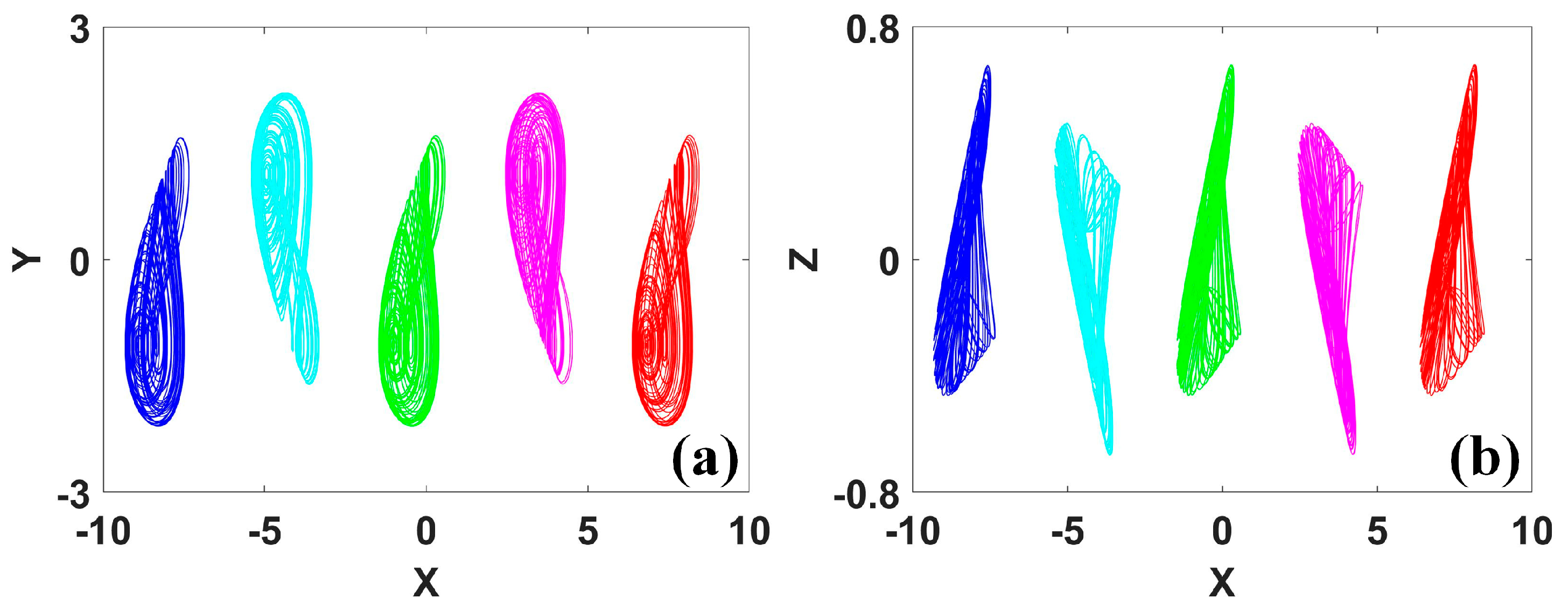

Figure 22.

Coexisting attractors in system (17): (a) x−y, (b) x−z. (IC = (1, 0, 0) is green, IC = (1+1.25π, 0, 0) is pink, IC = (1+2.5π, 0, 0) is red, IC = (1−1.25π, 0, 0) is cyan, IC = (1−2.5π, 0, 0) is blue.)

Figure 22.

Coexisting attractors in system (17): (a) x−y, (b) x−z. (IC = (1, 0, 0) is green, IC = (1+1.25π, 0, 0) is pink, IC = (1+2.5π, 0, 0) is red, IC = (1−1.25π, 0, 0) is cyan, IC = (1−2.5π, 0, 0) is blue.)

Figure 23.

‘A square earth with a round sky above’ and two types of circuit constraints.

Figure 23.

‘A square earth with a round sky above’ and two types of circuit constraints.

Figure 24.

A simple series chaotic circuit with a memristor, an inductor and a capacitor.

Figure 24.

A simple series chaotic circuit with a memristor, an inductor and a capacitor.

Figure 25.

Symmetric attractor in system (18) with α = 1, ω = 1 and IC = (4.1, 0.7, 5): (a) x−y, (b) y−z.

Figure 25.

Symmetric attractor in system (18) with α = 1, ω = 1 and IC = (4.1, 0.7, 5): (a) x−y, (b) y−z.

Figure 26.

Conditional symmetric chaotic attractors of system (19) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 2, (a) z-y, (b) z-x. (IC = (2, 0, −1) is up, IC = (−2, 0, 1) is down.)

Figure 26.

Conditional symmetric chaotic attractors of system (19) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 2, (a) z-y, (b) z-x. (IC = (2, 0, −1) is up, IC = (−2, 0, 1) is down.)

Figure 27.

Meminductive parallel chaotic circuit for realizing system (19).

Figure 27.

Meminductive parallel chaotic circuit for realizing system (19).

Figure 28.

Conditional symmetric chaotic attractors of system (19) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 2 observed in oscilloscope, (a) z-y, (b) z-x. (IC = (2, 0, −1) is green, IC = (−2, 0, 1) is brown.)

Figure 28.

Conditional symmetric chaotic attractors of system (19) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 2 observed in oscilloscope, (a) z-y, (b) z-x. (IC = (2, 0, −1) is green, IC = (−2, 0, 1) is brown.)

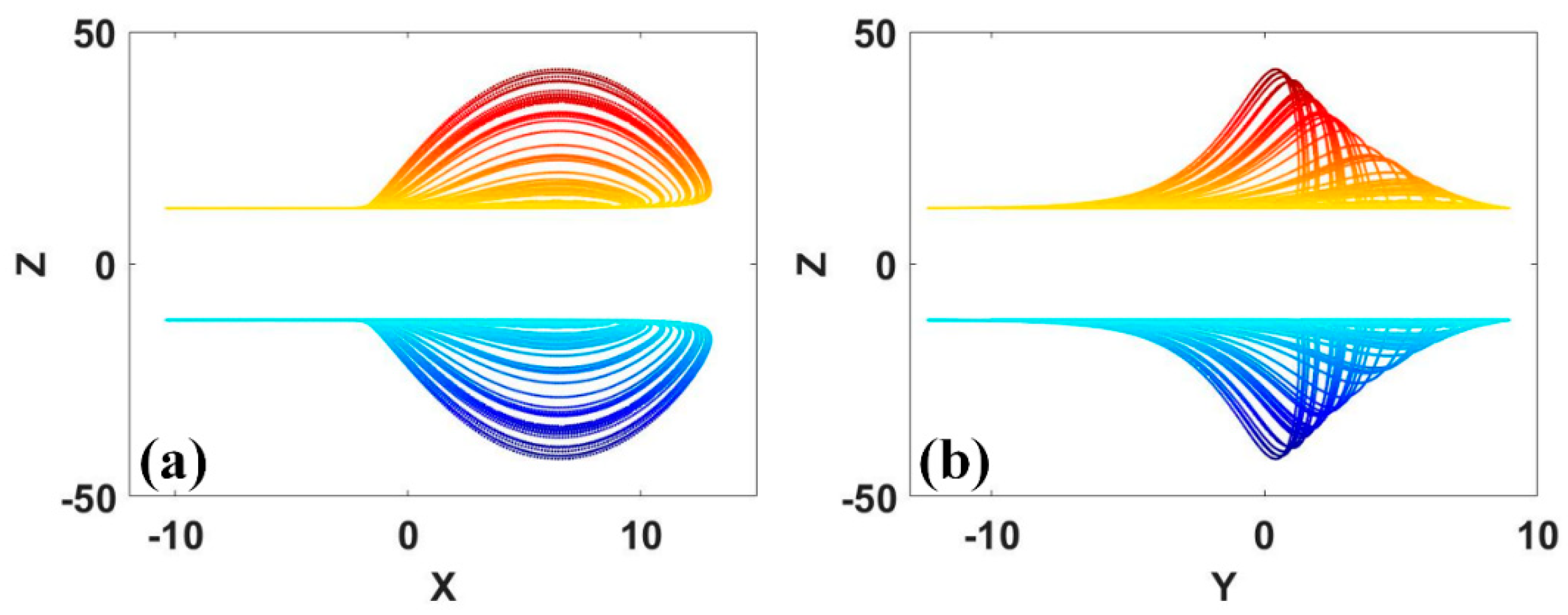

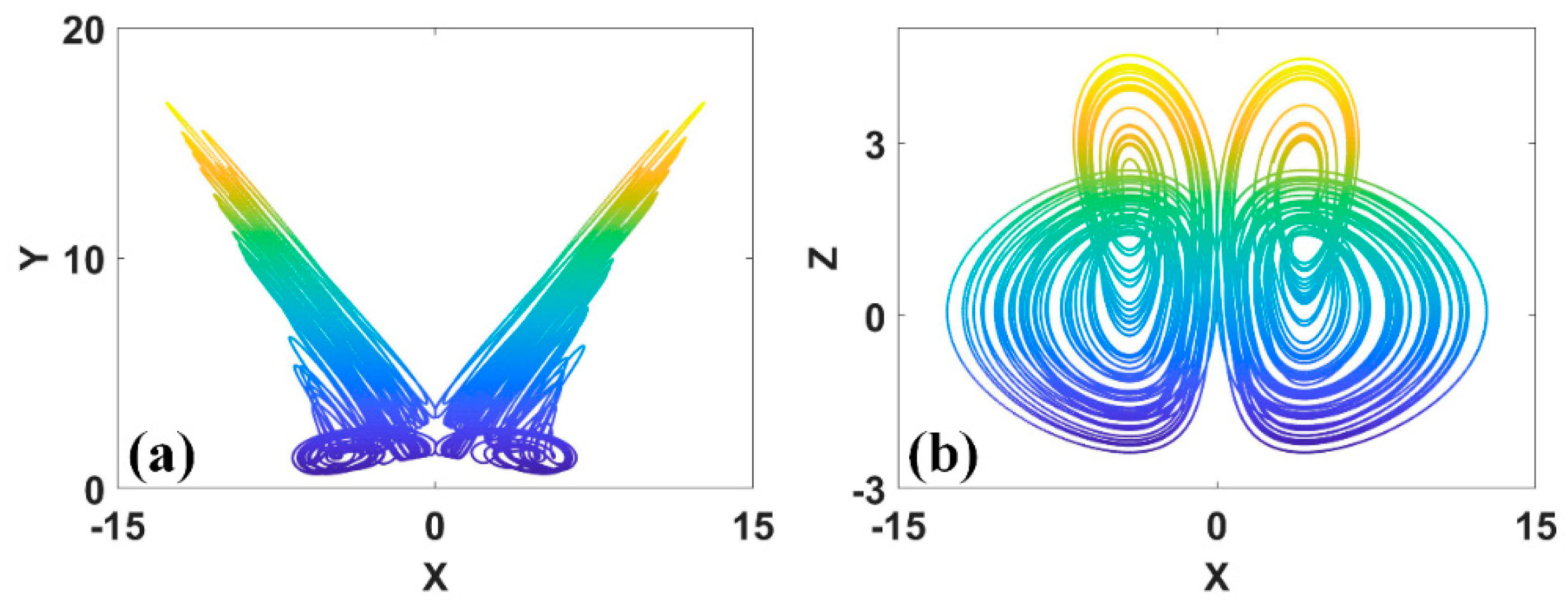

Figure 29.

Chaotic attractors in system (20) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 1, d = 4.11 and IC = (1, 1, −1), here two coexisting attractors close each other and bond to be a pseudo-double-scroll attractor: (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 29.

Chaotic attractors in system (20) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 1, d = 4.11 and IC = (1, 1, −1), here two coexisting attractors close each other and bond to be a pseudo-double-scroll attractor: (a) x−y, (b) x−z.

Figure 30.

Coexisting attractors of system (20) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 1, d = 8: (a) x−y, (b) x−z. (IC = (−1, 1, −1) is left, IC = (1, 1, −1) is right.)

Figure 30.

Coexisting attractors of system (20) with a = 0.6, b = 1, c = 1, d = 8: (a) x−y, (b) x−z. (IC = (−1, 1, −1) is left, IC = (1, 1, −1) is right.)

Figure 31.

Simple circuit operation unit: (a) multiplier current constraint under external resistance, (b) the resistor-capacitor coupling realizes current control.

Figure 31.

Simple circuit operation unit: (a) multiplier current constraint under external resistance, (b) the resistor-capacitor coupling realizes current control.

Figure 32.

Schematic circuit of the system (21).

Figure 32.

Schematic circuit of the system (21).