Summary: Through the construction of species distribution model, landscape index calculation and ecological risk assessment model, the habitat suitability of moose(Alces alces) population in Nanwenghe National Nature Reserve of the Great Khingan Mountains is evaluated. The results show that under the premise of global warming, in terms of landscape pattern, the areas with high suitability of moose in the habitat are also the areas where they prefer patch types, which are mainly concentrated in forests and rivers. However, the risk of landscape pattern fragmentation tends to increase from 2015 to 2020. Moose preference patch type is dispersed, the degree of polymerization is low, and the risk of patch type transformation is increased. In terms of ecological risk: the medium-and high-risk areas in the moose habitat are mainly concentrated in the river area and its nearby forests, showing fine and scattered distribution. The low ecological risk area is mainly distributed on both sides of the road and mountainous area, and the patch type is single. It shows that the moose habitat has a weak ability to resist risk in the future. The study suggests that we should avoid further human intervention in forests and rivers, formulate reasonable forest protection and sustainable development plans in cold temperate zones, and effectively monitor and protect the dynamics of cold temperate forests and moose populations.

1. Introduction

Forest ecosystem is a system with certain structure, function and self-regulation ability formed by forest biological community and its environment. In the terrestrial ecosystem, the forest ecosystem has the highest biological amount, the largest area, the most complex structure and the most perfect function, which plays an indispensable role in the global ecological process. As an important part of terrestrial ecosystem, forest ecosystem provides wild animals with food, habitat and other resources to ensure the survival and reproduction of wild animals. Therefore, the stability of the function and structure of forest ecosystem affects the global biodiversity. Once the structure and function of forest ecosystem is affected, it is likely to change the landscape pattern of wildlife habitat in the system. As the basis of species survival and reproduction, the change of landscape pattern will directly affect the migration, diffusion and communication of species [

1].

In recent years, under the disturbance of human activities to the global climate and forest ecosystem, the change of species habitat landscape pattern caused by forest ecosystem degradation and then affect the survival of species has become a global problem for wild animals. For large forest mammals, habitat fragmentation is more likely to affect their access to food resources and safe places, and lead to an increase in individual mortality [

2]. Based on the practice of wildlife conservation in recent years, it is particularly important to consider the dynamic changes of ecosystem and habitat while carrying out the protection of target species. Therefore, it is of great significance for the protection of target species and forest ecosystem to understand the dynamic changes of landscape spatial pattern of habitats and the ability of habitats to resist the disturbance of external factors.

The analysis of landscape pattern of species habitat is based on the analysis of landscape pattern, combined with the preference of target species to landscape elements such as patch type, size and shape, and the results can effectively reflect the quality of habitat. and to a certain extent reflect the degree of species preference for the current habitat [

3,

4].The ability of habitat to resist external factors is based on the size of landscape ecological risk index. the index indicates the impact and harm degree of negative factors such as increased risk of habitat destruction and decrease of biodiversity on regional ecosystem security caused by the dynamic change of landscape pattern [

5].Combined with the preference of target species for habitat selection, to a certain extent, the index not only reflects the habitat quality of target species, but also shows the harm of forest ecosystem under a variety of stress factors such as human disturbance and natural disasters.

Located in the northeast of China, the Great Khingan Mountains is not only the main distribution area of cold temperate zone in China, but also an important sensitive area of global ecological change.

The Great Khingan Mountains has the largest cold temperate forest ecosystem in China, and its unique cold and humid environment has formed a large bright coniferous forest area with

Larix gmelinii as the dominant tree species under the interaction of permafrost, wetland and forest [

6].The Great Khingan Mountains forest ecosystem not only improves the global climate, but also provides conditions for many precious endangered species to survive and reproduce. Recent studies have shown that the cold temperate zone is one of the main distribution areas of the permafrost on the earth. Global warming will weaken or even lose the function of the permafrost, resulting in the release of stored soil organic carbon. While further aggravating greenhouse effect [

7],It will lead to the increase of river flow level and water area in cold temperate forest, increase the frequency of flood disasters, and then change the species habitat pattern and affect the survival of species [

8].

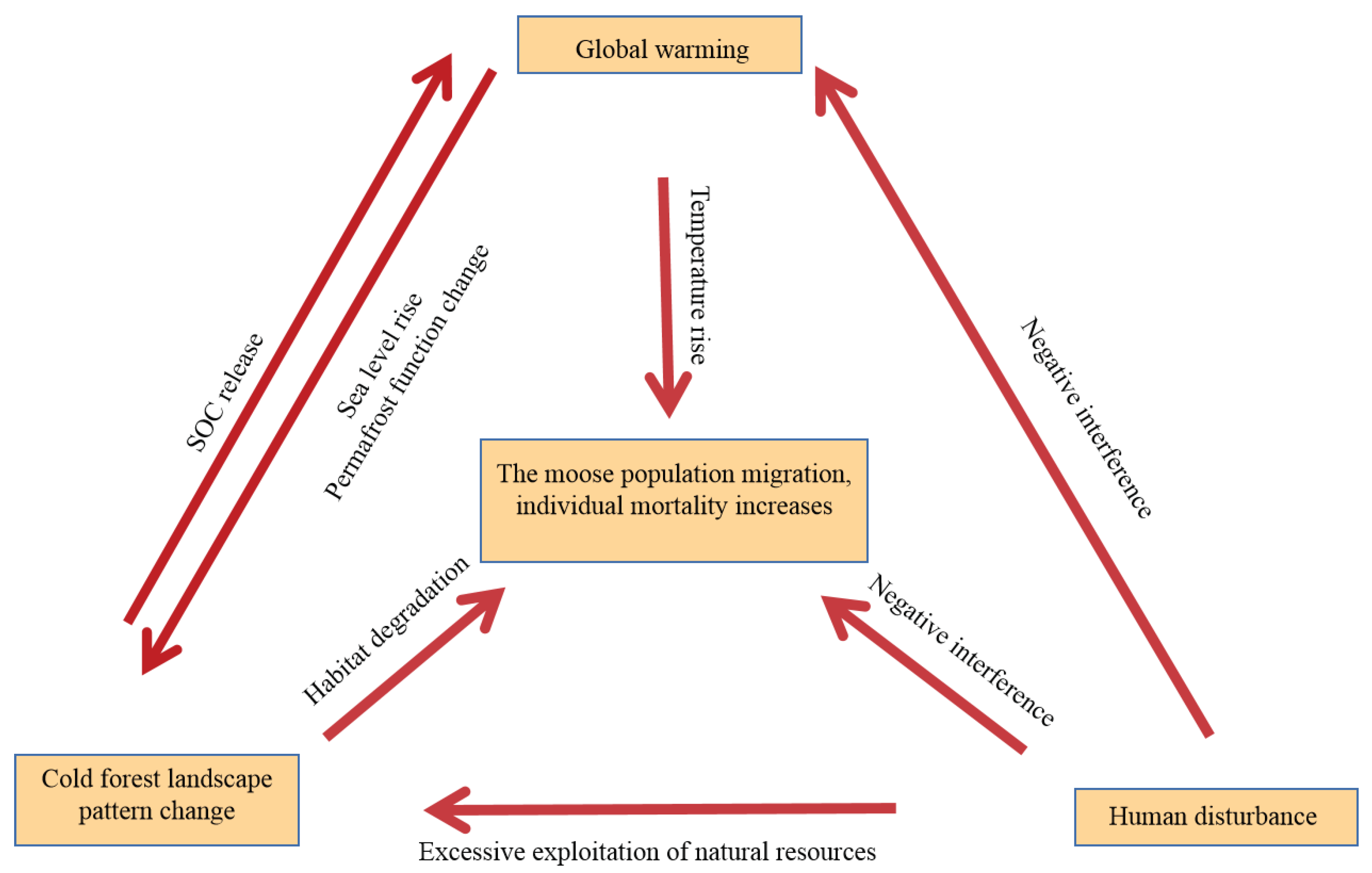

As one of the representative species of cold temperate forest ecosystem, moose population depends on forest ecosystem to obtain survival resources. With the increasing risk of functional degradation of forest ecosystem in cold temperate zone in recent years, it has produced a very significant ecological response to the number and distribution of moose population. Moose distributed in the Great Khingan Mountains of China is the southernmost population of this species in Eurasia. Compared with moose populations in other distribution areas, the risk faced by moose population in China is more severe [

9].On the one hand, due to global climate change, the negative impact of temperature change on moose is more intense in the southern edge of species distribution, especially in moose which are sensitive to temperature change, resulting in higher individual mortality [

10].On the other hand, due to the enhanced disturbance of human activities to the forest ecosystem, the habitat area of moose decreased, the risk of fragmentation increased [

11], and finally led to moose population migration and even led to the decline of the population [

12].The local extinction of the population will not only reduce the distribution range of moose in China, but also affect the global distribution pattern of moose. Therefore, the landscape pattern dynamics of cold temperate forest moose habitat was analyzed, and the ecological risk assessment of cold temperate forest landscape is combined to evaluate the resistance of habitat under stress factors. it can provide a theoretical basis for the protection of cold temperate forest moose population and the establishment of cold temperate forest national park in China.

In Nanweng River National Nature Reserve in the east of the Great Khingan Mountains, the land cover data of 2015 and 2020 were selected, combined with field survey and infrared camera monitoring data from April 2014 to January 2023 to quantitatively evaluate the suitability of moose habitat, habitat landscape dynamics and ecological risk. The purpose of this study is to provide a theoretical basis for effective protection of moose population and habitat in cold temperate forest.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area chooses the Great Khingan Cold temperate Nanweng River National Nature Reserve, which is located in Songling District of the Great Khingan area of Heilongjiang Province, which is a branch of the Great Khingan Mountains, bounded by the Yilhuli Mountains in the north, Huma 12 stations in the east, and adjacent to the Jiagdachi Forestry Bureau in the south. The geographical coordinates are 51 °05: 07 "N-51 °39: 24" E, 125 °07: 55 "- 125 °50: 05" E, with a total area of 229523hm

2, including forest area 128137hm

2 and wetland area 70480hm2 (

Figure 1).The land is a low mountain and hilly landform with little relief, high in the north and low in the south, high in the west and low in the east, with an elevation of 500m, 800m, the lowest 370m and the highest elevation of 1044m (

Figure 1).The reserve is located in the cold temperate zone, which belongs to the continental monsoon climate zone of the cold temperate zone, with a long cold period in winter and a short hot period in summer, with an annual average of-3 ℃, a maximum temperature of 30 ℃ and a minimum temperature of-48 ℃. The average annual precipitation is 600mm, of which July and August account for about 50% of the whole year.There are more than 20 large and small rivers in the territory, such as Nan Weng River, Kengdu River and Nanyang River, which flow through the whole territory from northwest to southwest and flow into Nenjiang River, which is the main birthplace and water conservation place of Nenjiang River.The soil types mainly include brown coniferous forest soil, meadow soil, swamp soil and stony soil. Typical brown coniferous forest soil is distributed on the middle slope of each slope direction, with an altitude of 700m to 1000m, meadow soil is mainly distributed on both sides of the river at an altitude of 500m to 700m, swamp soil is mainly distributed in a wet valley at an altitude of about 500m and 700m, and stony soil is rarely distributed in ridges above 800m above sea level. This area belongs to Pan-North Plant region and the Great Khingan Plant region. Its vegetation type is a typical cold temperate coniferous forest composed of

Larix gmelinii as constructive species, including

Betula platyphylla-

Larix gmelinii forest,

Rhododendron dauricum-

Larix gmelinii forest, grass swamp and larch swamp. There are more than 800 species of plants belonging to 61 families. The main tree species are

Larix gmelinii, Betula platyphylla and

Populus davidiana, and the main shrub species are

Rhododendron dauricum and

Spiraea salicifolia.There are 74 families and 309 species of wildlife resources. Among them, herbivorous mammals mainly include moose, red deer

(Cervus canadensis), Siberian roe deer (

Capreolus pygargus) and

lepus timidus.Carnivorous mammals mainly include

Lynx lynx,

Gulo gulo and so on.There are 216 species of birds, included

Tetrao urogalloides and

Bonasa bonasia. At the same time, there are 44 species of amphibians and reptiles such as

Salamandrella keyserlingii.

2.2. Sample Line Data Acquisition

From December 2021 to January 2023, the sample line method was used in Nanwenghe National Nature Reserve. The length of the sample line is at least 4km, and a large sample square of 10m*10m is set up every 400m and when the vegetation type changes, and five small sample squares of 1m*1m are set in the sample square. The survey area, date and time, sample coordinates, vegetation types, moose number and activity traces (footprints, feces and entities, etc.) were recorded in the form.Sample line spacing ˃ 2km, sample lines are randomly arranged at different levels. Due to the lack of access by vehicles in some areas of the reserve, the sample lines in this area cannot be arranged. In this survey, there are 126 sample lines, the number of samples is 1377, and the total length of sample lines is 512.6km.

2.3. Infrared Camera Data Acquisition

From April 2014 to January 2023, infrared camera technology was used to monitor moose resources in Nanwenghe National Nature Reserve. Using the kilometer grid method, according to the 1km*1km grid, the infrared camera is set up in the center of the grid where the moose may pass. A total of 267 infrared cameras were set up in this survey. According to the monitoring records, the infrared camera sites of moose entities were sorted out and summarized.

2.4. Environmental Data Acquisition

The distribution of moose is affected by climate, topography, human disturbance and other factors. In this experiment, 23 environmental factors are selected as modeling data, including landscape, topography, climate and human factors. They are 17 bioclimatic factors (Bio3-19), 2 geographical factors (elevation and slope), 2 vegetation data (landuse type and normalized difference vegetation index), 1 human disturbance factor (distance to road) and 1 basic geographic information data (distance to river).The spatial resolution of all environmental factors is resampled to 30m, the study area is taken as the layer boundary of environmental variables, and the projection coordinate system 1 is set to WGS-1984-UTM-ZONE-50N. It is convenient for the screening of subsequent environment variables.

2.5. Species Distribution Models Building

Through the collection of moose distribution point data of sample line survey records and infrared monitoring records, the data are preliminarily screened to eliminate data format errors and duplicate recorded data. After extraction and screening, the detailed longitude and latitude information of moose occurrence points were extracted, and a total of 145 moose occurrence sites were obtained. Using the SDMtoolbox spatial filtering tool in ArcGIS10.3, 1km is selected as the sparse radius to filter the occurrence points [

13], and 44 moose distribution points are obtained. In order to avoid the influence of the correlation between environmental variables on the results of the model, the Pearson correlation test of 23 environmental factors was carried out. The final retention of environmental factors with a correlation coefficient of less than 0.7.After screening, 12 environmental factors are obtained (

Table 1), and the obtained environmental factors are converted into ASC file format by using the transformation tool of ArcGIS10.3 [

14].ROC curve, that is the area value under the subject’s working characteristic curve, The ROC(receiver operating characteristic curve) ,which is the value of the area under the subject’s working characteristic curve(AUC, area under curve) ,curve measure the pros and cons of the model. Import the screened environmental factors and field species survey data into the MaxEnt model [

15].75% of the moose distribution sites were randomly selected as the training set to establish the prediction model. The rest of the distribution points are used as test sets to verify the model, and logistic is selected to output the results. The repeated operation coefficient of the model is set to 10 times, the repeated operation category selects sub samp, and other parameters use the default settings and run [

16].

2.7. Analysis of Landscape Pattern of Habitat

Based on the moose habitat simulated by MaxEnt model, the ArcGIS10.3 screening and extraction tools were used to cut the data of land cover types in 2015 and 2020.According to the attribute classification, the land cover types of moose habitat are divided into five first level types: arable land, forest, water area, grassland and unused land. There are 7 second level types of dry land, closed forest land, shrubs, sparse woodland, high coverage grassland, medium coverage grassland and swamp [

17,

18].Using Fragstats4.3 software, the following indicators were selected at the patch and landscape level to calculate the moose habitat landscape pattern index under different time series.

According to the landscape pattern index of 6 patch types [

19], 6 indexes were selected.

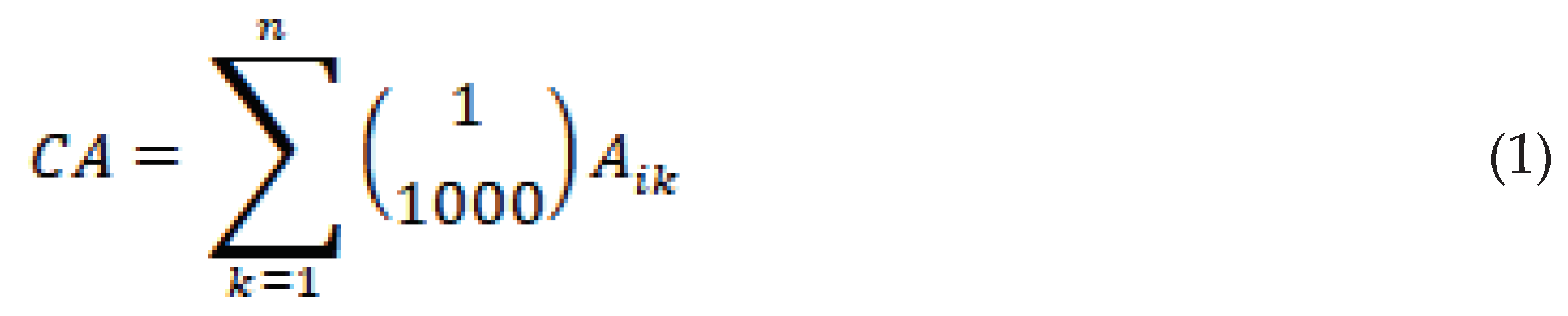

Class area calculation formula is:

where,

Aik represents the area of the

k patches of category i landscape elements, and n is the number of patches.

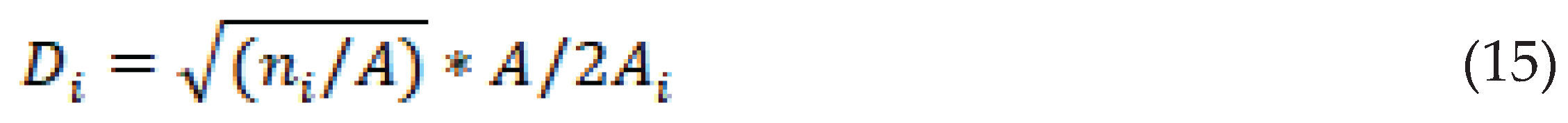

Patch density calculation formula is:

where,

Ni represents the total number of

patches in category i landscape. An is the total landscape area.

Landscape shape index calculation formula is:

where,

ai represents the

maximum patch area of category i landscape.

Landscape shape index calculation formula is:

where, C

i represents the perimeter of type i

landscape, and represents the perimeter of the circle of the same area.

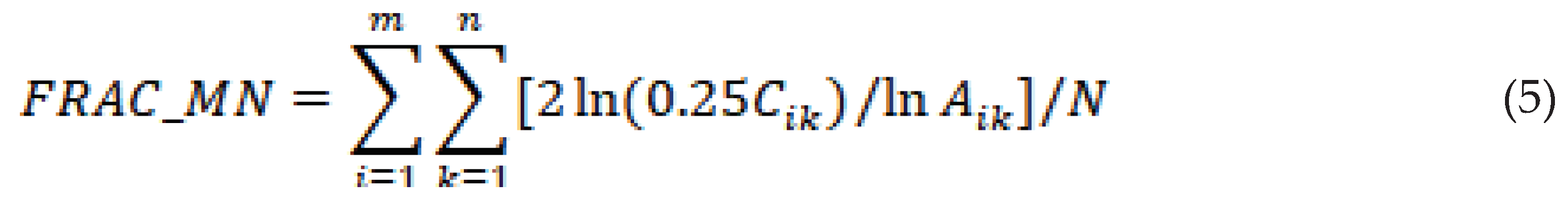

Mean fractal dimension calculation formula is:

where, m is the total number of landscape

types and

Cik is the

perimeter of patch ik.

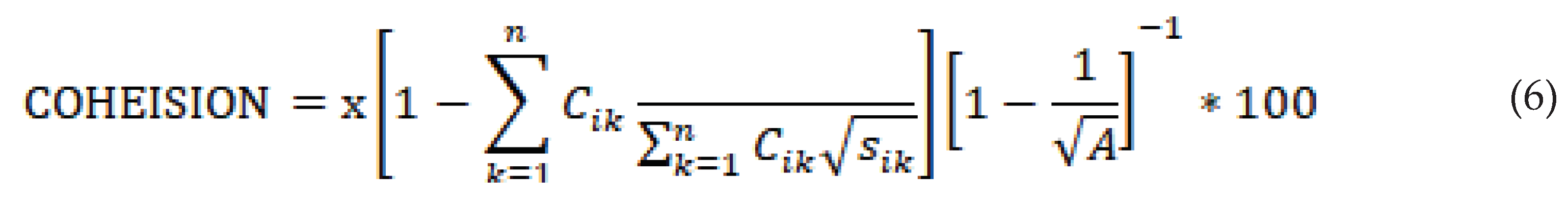

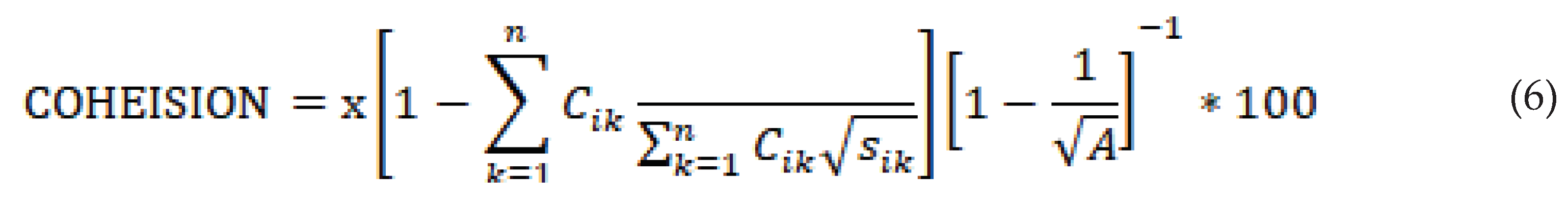

Patch cohesion index calculation formula is:

where,

Sik is the area of plaque ik.

According to the landscape level, a total of 5 indicators are selected for calculation.

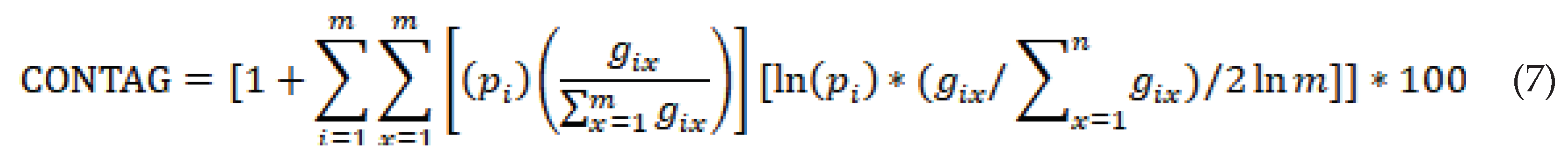

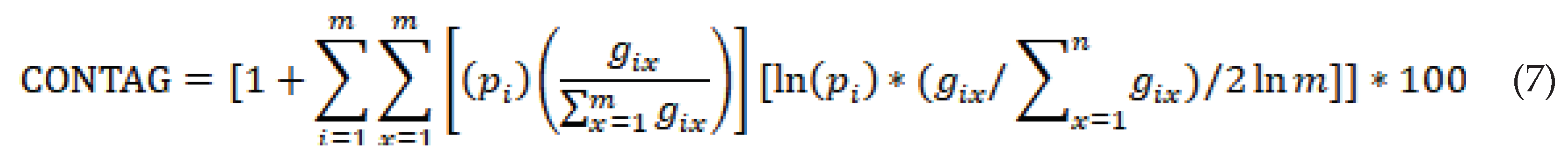

Contagion index calculation formula is:

where,

gix is the number of

grids adjacent to x of landscape type i.

Split index calculation formula is:

where,

Mi is the distance index of type i

landscape.

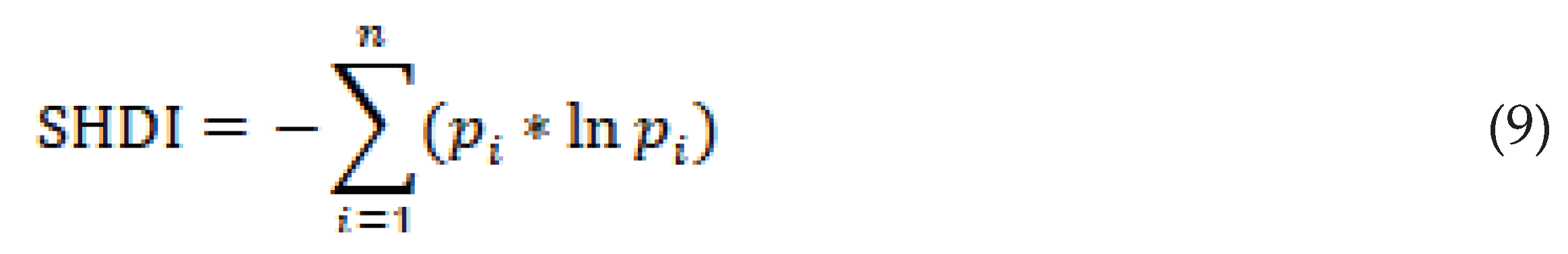

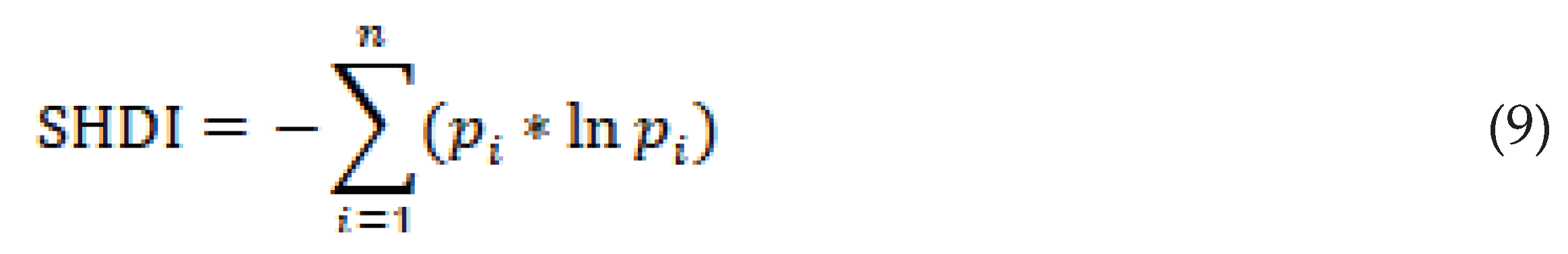

Shannon’s diversity index calculation formula is:

wheres,

Pi refers to the

proportion of category i landscape to the total landscape area.

Aggregation index calculation formula is:

where,

gii refers to the number of adjacent

patches in the adjacent landscape.

2.8. Ecological Risk Assessment of Habitat Landscape

Based on Fragstats4.3 software, the landscape pattern index of different patch types is obtained, and the landscape vulnerability index, landscape interference index and landscape loss index are calculated to construct the landscape ecological risk assessment model [

20].Based on the method of grid sampling, the fishing net map is compiled by ArcGIS10.3, and the landscape ecological risk index (ERI) in the grid is calculated. The ecological risk map of habitat landscape was compiled in ArcGIS10.3 by Kriging interpolation method [

21].

Ecological risk index calculation formula is:

where,

Aki represents the category i landscape

area of k sampling area.

Ak represents

the area of the sampling area.

represents the landscape loss index.

The landscape loss index indicates the degree of loss when the landscape is disturbed, and its calculation formula is:

where,

indicates the landscape disturbance index.

indicates the landscape vulnerability index. The method of expert assignment is used to assign the vulnerability of six landscape types, which is 6 for unused land, 5 for water area, 4 for arable land, 3 for grassland, 2 for forest and 1 for urban and rural construction land. then the landscape vulnerability index is obtained by normalization.

The landscape disturbance index indicates the degree of landscape disturbance and its calculation formula is:

where,

,

,

represent landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index.A, b and c represent the weights of different landscape indexes respectively. Combined with the actual situation of the study area(Lou et al., 2020),the weights (a, b, c) of landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index were assigned to 0.5,0.3 and 0.2 respectively.

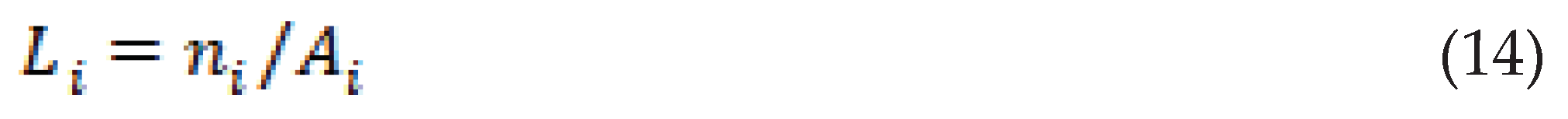

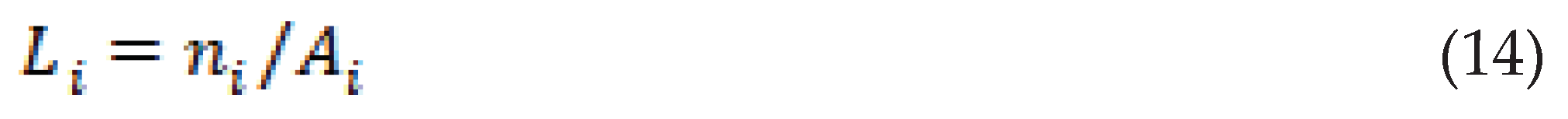

Landscape fragmentation index indicates landscape internal stability and its calculation formula is:

where,

Ai represents category i landscape

area.

ni represents the number of patches in

category i landscape.

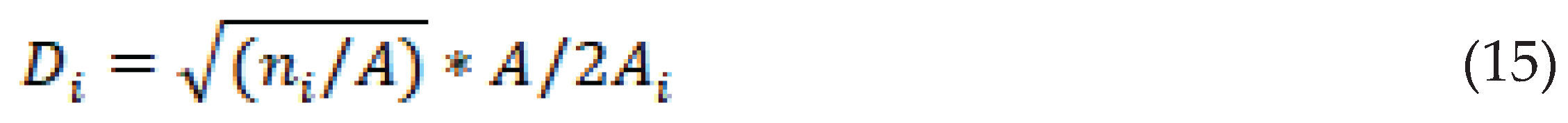

The landscape division index indicates the degree of spatial separation of patches, and its calculation formula is:

where, A represents the total area of all landscapes.

The landscape fractal dimensional index represents the shape complexity and spatial stability of landscape patches, and its formula is :

where,

qi represents the

perimeter of landscape type i.

3. Results

3.1. Habitat Suitability of Moose

The occurrence sites and environmental variables of the processed moose are introduced into the species distribution model to obtain the suitability layer of the moose in the study area(

Figure 2).The simulation results of MaxEnt model show that the average training set AUC value is 0.828 and the standard deviation is 0.074, which indicates that the simulation result of species distribution model is better, and the fitting degree of the model is relatively high. Based on the Equal Training Sensitivity Specificity Threshold automatically generated by MaxEnt, the predicted map of moose habitat suitability index is converted into a binary map of habitat and non-habitat based on the output results of the model in ArcGIS10.3 software. The automatically generated Equal Training Sensitivity Specificity Thresold value in the results of MaxEnt model is 0.435, which is used as a threshold to generate the distribution range of moose population in Nanweng River Nature Reserve (

Figure 3), which is used as the boundary for subsequent landscape pattern analysis.

3.2. Landscape Dynamics of Moose Habitat

3.2.1. Patch Scale Characteristics

Combined with the results of field investigation, distribution model and landscape index calculation, the large area of moose habitat is mainly concentrated in the river area of Nanweng River and Guandu River,

Larix gmelinii-

Betula platyphylla mixed forest and grassland swamp area. Among them, the areas with the highest suitability are mainly rivers and larch forests (

Figure 2) to ensure the needs of moose individuals for food, temperature and other survival factors.

The largest landscape types in moose habitat are high coverage grassland and closed forest land, followed by sparse woodland and dry land, and the smallest area of swamp, shrub and medium coverage grassland (

Figure 4 and

Table 2). From 2015 to 2020, the patch area of dry land, shrub and sparse woodland increased, and the area of sparse woodland increased by 1159.11hm

2. The medium coverage grassland disappeared completely, and the patch type area of high coverage grassland, closed forest land and swamp decreased. Among them, the area of high coverage grassland decreased by 1683.09hm

2, the LPI of dry land and sparse woodland increased, and other landscape types decreased. In terms of LSI, dry land, closed forest land and sparse woodland increased by 1.16, 0.85 and 0.75, while shrubs, high coverage grasslands, medium coverage grasslands and swamps decreased by 0.42, 1.98, 1.4 and 2.12. In terms of FRAC_MN, shrubs and medium coverage grasslands decreased by 0.02 and 1.08, swamps increased by 0.03, and other landscape types changed little. The COHESION of shrub, dry land and sparse woodland increased by 0.78, 1.42 and 0.17 respectively, while that of closed forest land, high coverage grassland, medium coverage grassland and swamp decreased by 0.30,0.22,59.26 and 2.75 respectively.

3.2.2. Landscape Scale Characteristics

From 15 to 2020, the CONTAG decreased by 4.53, the SPLIT increased by 4.86, and the landscape fragmentation showed an increasing trend (

Table 3). In the past five years, the AI changed little, and the SHDI and SHEI showed an increasing trend. The moose habitat is mainly in the vicinity of woodland, Nanweng River and other rivers. from 2015 to 2020, the dominant patch area decreased, the landscape pattern fragmentation increased, and the closed forest land dominated by trees gradually changed into sparse woodland, dry land and other land types. Based on this, it shows that the whole cold temperate coniferous forest region with coniferous forest as zonal vegetation is likely to be in a similar transformation process. The change of patch type is likely to be part of the result and reflection of the northward movement of the whole cold temperate zone under the condition of global warming.

3.3. Ecological Risk of Habitat Landscape

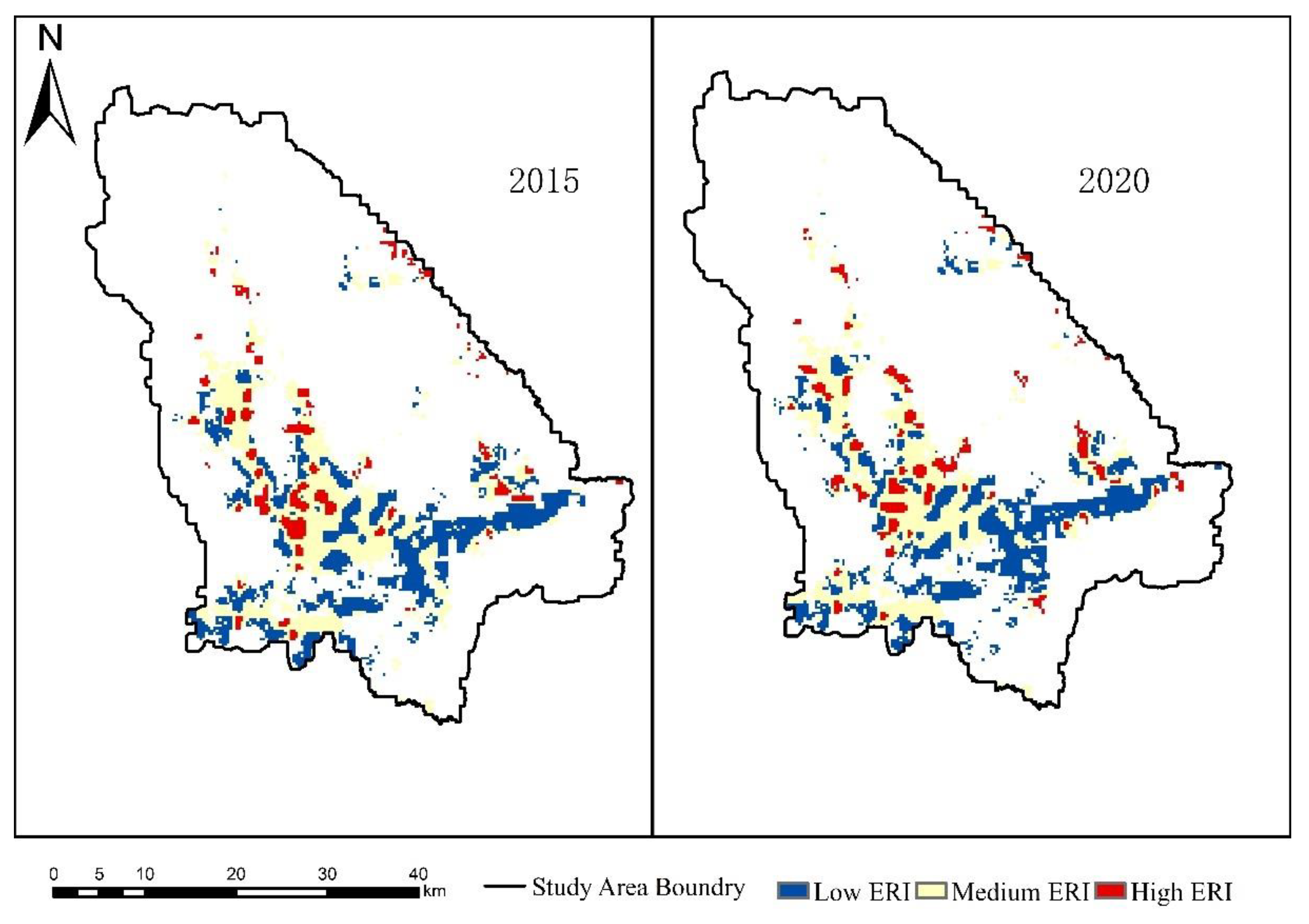

According to the natural breakpoint method, the landscape ecological risk area of moose habitat in Nanweng River Nature Reserve is divided into three grades: Low ERI(0.0196≦ERI<0.0248), Medium ERI(0.0248≦ERI<0.0323), High ERI(0.0323≦ERI<0.0587).

The results showed that the moose habitat in Nanweng River Nature Reserve was dominated by low risk area and stroke risk area, the marginal woodland within 1km on both sides of the highway belonged to low risk area, and the ecological risk grade of high coverage grassland and river area was higher. From 2015 to 2020, the proportion of areas with low ecological risks increased by 0.88%; that of areas with medium ecological risks decreased by 1.11%; and that of areas with high ecological risks increased by 0.23%. Combined with the moose habitat suitability index map, the areas with high suitability are mainly middle and high ecological risk areas. with the decrease of the distance from roads and building facilities, the ecological risk grade decreases and the suitability index decreases. The middle and high risk areas are concentrated in wetlands and water distribution areas, and the patches of closed forest land, swamp and high coverage grassland are fine and scattered, and the characteristics of patch fragmentation are obvious. The low ecological risk area is mainly distributed on both sides of the road and in the mountainous area. due to human activities, the land around and on both sides of the road is reclaimed into sparse woodland and dry land with low canopy density, the patch type is single, and the level of ecological risk is low. and there is a tendency to expand outward on both sides of the highway in the low ecological risk area. Between 2015 and 2020, the area of high ecological risk areas increased, mainly due to the rise in river water levels in cold temperate regions caused by global warming, resulting in an increase in regional risk index (

Table 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

As the basis for the survival and reproduction of wild animal population, habitat needs to meet its necessary survival conditions, including rich food resources, resting and breeding places, predation risk avoidance and other factors. As a species with strong adaptability to cold and extremely sensitive to high temperature, moose [

22]. In habitat selection, the habitat should not only meet the needs of its food resources and avoid natural enemies, but also ensure that the temperature conditions in the habitat meet the needs of species survival. Once the habitat pattern changes, it will directly affect the distribution of moose population in the habitat [

23,

24].

Through the analysis of habitat pattern dynamics, to explore the impact of habitat dynamics on moose population, in order to implement ecological restoration and related management measures in time; based on the dynamic changes of landscape pattern, this paper analyzes the potential hidden dangers that the current cold temperate forest ecosystem may face under the influence of global climate change and human activities. In this paper, the occurrence point of moose was obtained by field investigation and infrared monitoring, the habitat range of moose was determined by species distribution model, the pattern index of patch level and landscape level was calculated by Fragstats4.3 software, and the dynamic changes of landscape pattern of moose habitat under different scales and different time series were analyzed. Landscape index reflects the spatial structure of different types of patches, combined with species preference for patch types and landscape pattern changes, to a certain extent, it can be used as one of the bases for judging the current habitat preference of animal populations.

According to the calculation results of landscape index, from 2015 to 2020, on the patch scale, the patch area of moose preferred land cover type decreased, the patch density decreased, the patch shape became more complex, and the agglomeration degree of main patch types was weak and the trend of dispersion increased. In terms of landscape scale, the degree of landscape aggregation of moose habitat in the reserve is high, and the degree of landscape separation is low, indicating that the degree of landscape fragmentation is not high on the landscape scale, but the CONTAG decreases and the SPLIT increases. It shows that the landscape fragmentation of moose habitat has an increasing trend.

In recent years, due to the rise of sea level and the increase of land water area caused by global warming, the water level of Nenjiang River and its tributaries has increased even higher than the warning line for many times. on-the-spot investigation found that serious floods occurred in the study area in 2016 and 2020. This shows that the dynamic change of landscape pattern from 2015 to 2020 is mainly caused by frequent floods caused by global warming. Previous studies have shown that the increase in temperature affects the function and structure of the ecosystem, which in turn affects the distribution pattern of animals and plants [

25].Based on the results of landscape index, it shows that under the influence of global climate change, the risk of landscape pattern fragmentation in the Great Khingan forest region in cold temperate zone increases, and the dominant species which are dominated by coniferous forest begin to decrease, and the dominant type patches tend to disperse on the landscape scale. the area of woodland decreased, while the area of sparse woodland and dry land increased. Under the condition of global warming, the change of patch types and the decrease of dominant tree species are likely to be part of the result and embodiment of the northward movement of the cold temperate zone. For the cold temperate moose population, the negative factors such as the change of habitat pattern and the increase of cold temperate temperature will greatly affect the survival and reproduction of moose individuals [

11,

26].

According to the patch type change and landscape index calculation results, the moose habitat near the highway and other human buildings, the patch type is single, there is a trend of patch type transformation, the original woodland and high coverage grassland changed into dry land and sparse woodland, and spread to both sides along the highway. It shows that the direct interference of human activities to the natural environment is enough to aggravate the transformation of patch types in the habitat. Based on this, it shows that in the global warming, direct human interference and natural disasters and other factors are likely to directly affect the stability of the whole cold temperate forest ecosystem, and then affect the living environment of forest wildlife species such as moose in the cold temperate zone.

In the face of external interference, the resistance and resilience of different types of patches are different. when the intensity and frequency of external interference increase, the risk of damage to some types of patches will increase, and even lead to the change of patch type. and then affect the habitat landscape pattern, and finally lead to the distribution of moose population in the habitat. Landscape ecological risk assessment focuses on identifying the hazards that may be caused by natural disasters and human activities in the assessment region to the study of regional receptors (land use, landscape pattern, etc.) [

5,

27].An ecological risk assessment model is constructed, and the results can explain the changes of the spatial distribution pattern of risk under different time series, and analyze the resistance of habitat to external disturbance under the current risk distribution [

28,

29].This paper takes the moose habitat as the modeling area, human activities such as road construction and natural disasters from 2015 to 2020 as the risk source, and the habitat landscape pattern as the risk receptor to construct the ecological risk assessment model of cold temperate forest moose habitat in Great Khingan Mountains. From the results (

Figure 5), the temporal and spatial distribution of ecological risk intensity in 2015 and 2020 on the time scale, the increasing trend of risk intensity in moose habitat is not obvious; in terms of spatial evolution, the middle and high risk areas of habitat are concentrated in areas far away from human activities, and the risk grade decreases gradually with the decrease of distance from the road. It shows that the ecological risk level of moose preference patch type is higher, and the ability to resist risk sources is weak compared with other types of patches. Some studies have shown that the areas with medium and high ecological risks are mainly concentrated in the distribution areas of rivers and wetlands [

30].

According to the results of this risk model, the increase in the area of high-risk areas in the study area may be due to the expansion of river areas caused by floods, and the increase of risk value caused by the transformation of forests and grasslands into wetlands. Therefore, under the condition of global climate change, the risk value of the whole cold temperate forest region, especially in the vicinity of the river, is likely to increase due to the change of surrounding patch types caused by the increase of river area. The consequences usually reduce the ability of the region to resist the source of risk, which will further aggravate the plaque type transformation rate under the condition of external factors. At the same time, under the premise of global warming, the release of organic carbon from the permafrost in the cold temperate zone amplifies the positive feedback effect on climate warming [

31,

32].And the two factors promote each other to aggravate the risk value in some areas of the cold temperate zone, which leads to the weakening of the resistance to external factors in the cold temperate zone and finally affects the distribution of moose population in the cold temperate zone.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that the whole cold temperate region is facing the risk of increasing the transformation trend of dominant patch types in the cold temperate coniferous forest region dominated by coniferous forest caused by global warming, and even the whole cold temperate zone may move northward. This not only leads to the increase of population mobility and mortality due to the decrease of habitat suitability and the increase of environmental temperature of moose population in the south of cold temperate zone (

Figure 6). It is also likely to cause the lack of diversity and ecological integrity of the whole cold temperate forest ecosystem [

33,

34].In addition, the direct interference of human activities to the natural environment also aggravates the speed of patch type transformation in cold temperate forest areas, especially in the vicinity of highways and building facilities.

Through this study, the author suggests that we should strengthen the protection of forests and rivers, avoid further intervention of more human activities, reduce the intensity of human activities in the reserve, and indirectly reduce the negative impact on moose resting and foraging places. We should formulate a reasonable plan for forest protection and sustainable development in the cold temperate zone, and reasonably plan the area of wildlife habitat and eco-tourism scenic spots. Slow down the process of patch transformation, fully restore the connectivity of moose habitat, and better protect the cold temperate forest moose habitat.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., S.S, Y.H., J.G., and N.Z.; methodology, M.Z., S.S., Y.H. and J.G.; validation, M.Z., S.S., Y.H., J.G. and N.Z.; formal analysis, S.S. ; investigation, S.S.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. ; writing—review and editing, M.Z., and Y.H.; visualization, S.S. ; supervision, S.S; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Forestry and Glassland Administration Project, China: Investigation, monitoring and patrol of Amur tiger in Greater Khingan Mountains.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged the administrators, professional staff, and guides of the Nanwenghe region. Special thanks are given to W.Z. for the fund support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilson M C, Chen X Y, Corlett R T, et al. Habitat fragmentation and biodiversity conservation: key findings and future challenges. Landscape Ecology, 2016, 31(2): 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Barelli C, Albance D, et al. Habitat fragmentation is associated to gut microbiota diversity of an endangered primate: implications for conservation. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 14862. [CrossRef]

- Chu L, Sun T C, Wang T W, et al. Evolution and prediction of landscape pattern and habitat quality based on CA-Markov and InVEST model in Hubei section of Three Gorges Reservoir Area(TGRA). Sustainability, 2018, 10(11): 3854. (In Chinese).

- Steffens T S, Lehman S M. Lemur species-specific metapopulation response to habitat loss and fragmentation. PLoS One, 2018, 13(5). [CrossRef]

- CHEN Chunli, WANG Tieyu, et al. Emerging issues and prospects for regional ecological risk assessment. Acta EcologicaSinica, 2010, 30(03): 808-816. (In Chinese).

- Ruihan Xiao. Nitrogen transformation and transport characteristics of Larix gmelini forest ecosystem in cold-temperate area of Daxingʹan Mountains. Northeast Forestry University,2022. (In Chinese).

- Schuur E, Abbott B, et al. High risk of permafrost thaw: Northern soils will release huge amounts of carbon in a warmer world. Nature, 2011, 480(7375): 32-33.

- WANG Mu-yang, ZHANG Chu-jie, et al. Potential impacts of climate change on suitable habitats. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology,2021,32(09):3127-3135. (In Chinese).

- ZhiXiaoliang. The population status and habitat spatiotemporal dynamics of moose (Alces alces) in Northeast China.NortheastForestry University,2023. (In Chinese).

- Meghan A, et al. Moose Response to High-Elevation Forestry: Implications for Apparent Competition with Endangered Caribou. Wildlife Management. 2018, 82(2): 299-309. [CrossRef]

- AO Xiaolan, ZHOU Lin, WU Tingxun, et al. Landscape dynamics and ecological risk of the expressway crossing section in the Hainan Rainforest National Park. Acta EcologicaSinica, 2022,42(16):6695-6703. (In Chinese).

- Tomáš J, Wibke P, Martin Š, et al. The declining occurrence of moose (Alces alces) at the southernmost edge of its range raise conservation concerns. Ecology and Evolution. 2021, 10(11): 5468-5483. [CrossRef]

- YuYanze, Zhang Minghai, Du Hairong, et al. Optimized MAXENT Model in Simulating Distribution of Suitable Habitat of Moose. Journal of Northeast Forestry University. 2019,47(10):81-84+95. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Adriaensen F, Chardon J, Deblust G, et al. The application of ‘least-cost’ modelling as a functional landscape model. Landscape and Urban Planning.2003,64(4):233-247. [CrossRef]

- Guisan A, Tingley R, Baumgartner J B, et al. Predicting species distributions for conservation decisions. Ecol Lett, 2013, 16(12): 1424-35. [CrossRef]

- TENG Yang, ZHANG Zhao, et al. Habitat suitability analysis and ecological corridor designs for red deer (Cervus elaphus) in the southern Greater Khingan Mountains. Acta EcologicaSinica,2022,42(14):5990-6000. (In Chinese).

- LOU Ni, WANG Zhijie, et al. Assessment on ecological risk of Aha Lake National Wetland Park based onlandscape pattern. Research of Soil and Water Conservation. 2020,27(1):233-239. (In Chinese).

- TANG Bo, et al. Review on the Ecological Risk Assessment of Wetland. Journal of Anhui Agri.Sci. 2009,37(13):6104-6107. (In Chinese).

- Yang R, Cao Y, Huo S, Peng Q Y, Wang X S, Wang F Y, TzHsuan T, Yu L, Steve C, Lan C, Liu H, Gong P, Ma K P. Cost-effective priorities for the expansion of global terrestrial protected areas:setting post-2020 global and national targets. Science Advances, 2020, 6(37): eabc3436. [CrossRef]

- Malekmohammadi B, Rahimi Blouchi L. Ecological risk assessment of wetland ecosystems using multi criteria decision making and geographic information system. Ecological Indicators, 2014, 41(6): 133-144. [CrossRef]

- GAO Bin-pin, LI Chen, et al. Landscape ecological risk assessment and influencing factors in ecological conservation area in Sichuan-Yunnan provinces, China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2021,32(05):1603-1613. (In Chinese).

- Hasbrouck T R, Brinkman T J, et al. Quantifying effects of environmental factors on moose harvest in Interior Alaska. Wildlife Biology. 2020, 2020(2). [CrossRef]

- Tomáš J, Wibke P, Martin Š, et al. The declining occurrence of moose (Alces alces) at the southernmost edge of its range raise conservation concerns. Ecology and Evolution. 2021, 10(11): 5468-5483. [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, S. Jennewein, Mark Hebblewhite, et al. Behavioral modifications by a large-northern herbivore to mitigate warming conditions. Movement Ecology.2020, 8(1): 39-52. [CrossRef]

- Root T L, Price J T, Hall K R, et al. Rosenzweig C, Pounds J. Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants. Nature,2003, 421(6918);57-60. [CrossRef]

- McCain CM, King SRB. Body size and activity times mediate mammalian responses to climate change. Glob Chang Biol. 2014, 20(6): 1760-9. [CrossRef]

- CAI Zhen, NIE Hua. Ecological Risk Management for Wetlands. Wetland Science and Management. 2007,3(4):50-53. (In Chinese).

- Zhao Z N, Zhang T Z. Integration of ecosystem services into ecological risk assessment for implementation in case study of the Yellow River, China. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: an International Journal, 2013,19(1): 80-97. (In Chinese).

- Fan J H, Wang Y, Zhou Z, You N S, et al. Dynamic ecological risk assessment and management of land use in the middle reaches of the Heihe River based on landscape patterns and spatial statistics. Sustainability, 2016, 8(6) : 536. (In Chinese).

- WAN Huilin, WANG Saige, et al. Ecological risk assessment and spatial threshold analysis of wetlands in the Sanjiang Plain. Acta EcologicaSinica, 2022,42(16):6595-6606. (In Chinese).

- CHEN Zhe, JIN Yan-xia, et al. A Review on the Impact of Global Warming to Greenhouse Gas Flux in Frozen Ground Region. Acta AgrestiaSinica, 2023, 31(04): 929-942. (In Chinese).

- Liu Xia. The research of soil respiration rate and its impact factors of forestry and swamp in cool temperate zone permafrost regions.NortheastForestry University,2015. (In Chinese).

- Wang Z M, Song K S, Ma W H, Ren C Y, Zhang B, Liu D W, Chen J M, et al. Loss and fragmentation of marshes in the Sanjiang Plain, northeast China, 1954-2005. Wetlands, 2011, 31(5): 945-954. (In Chinese).

- YANG Chunxia, ZHENG Hua, et al. Changes, Effect and Driving Forces of Land Use in Sanjiang Plain. Environment Protection Science, 2020,46(5):99-104. (In Chinese).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

where, Aik represents the area of the

k patches of category i landscape elements, and n is the number of patches.

where, Aik represents the area of the

k patches of category i landscape elements, and n is the number of patches. where, Ni represents the total number of

patches in category i landscape. An is the total landscape area.

where, Ni represents the total number of

patches in category i landscape. An is the total landscape area. where, ai represents the

maximum patch area of category i landscape.

where, ai represents the

maximum patch area of category i landscape. where, Ci represents the perimeter of type i

landscape, and represents the perimeter of the circle of the same area.

where, Ci represents the perimeter of type i

landscape, and represents the perimeter of the circle of the same area. where, m is the total number of landscape

types and Cik is the

perimeter of patch ik.

where, m is the total number of landscape

types and Cik is the

perimeter of patch ik. where, Sik is the area of plaque ik.

where, Sik is the area of plaque ik. where, gix is the number of

grids adjacent to x of landscape type i.

where, gix is the number of

grids adjacent to x of landscape type i. where, Mi is the distance index of type i

landscape.

where, Mi is the distance index of type i

landscape. wheres, Pi refers to the

proportion of category i landscape to the total landscape area.

wheres, Pi refers to the

proportion of category i landscape to the total landscape area. where, gii refers to the number of adjacent

patches in the adjacent landscape.

where, gii refers to the number of adjacent

patches in the adjacent landscape. where, Aki represents the category i landscape

area of k sampling area. Ak represents

the area of the sampling area.

where, Aki represents the category i landscape

area of k sampling area. Ak represents

the area of the sampling area.

where, indicates the landscape disturbance index. indicates the landscape vulnerability index. The method of expert assignment is used to assign the vulnerability of six landscape types, which is 6 for unused land, 5 for water area, 4 for arable land, 3 for grassland, 2 for forest and 1 for urban and rural construction land. then the landscape vulnerability index is obtained by normalization.

where, indicates the landscape disturbance index. indicates the landscape vulnerability index. The method of expert assignment is used to assign the vulnerability of six landscape types, which is 6 for unused land, 5 for water area, 4 for arable land, 3 for grassland, 2 for forest and 1 for urban and rural construction land. then the landscape vulnerability index is obtained by normalization. where, ,, represent landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index.A, b and c represent the weights of different landscape indexes respectively. Combined with the actual situation of the study area(Lou et al., 2020),the weights (a, b, c) of landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index were assigned to 0.5,0.3 and 0.2 respectively.

where, ,, represent landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index.A, b and c represent the weights of different landscape indexes respectively. Combined with the actual situation of the study area(Lou et al., 2020),the weights (a, b, c) of landscape fragmentation index, landscape division index and landscape fractal dimension index were assigned to 0.5,0.3 and 0.2 respectively. where, Ai represents category i landscape

area. ni represents the number of patches in

category i landscape.

where, Ai represents category i landscape

area. ni represents the number of patches in

category i landscape. where, A represents the total area of all landscapes.

where, A represents the total area of all landscapes. where, qi represents the

perimeter of landscape type i.

where, qi represents the

perimeter of landscape type i.