1. Introduction

Several devastating central nervous system diseases (CNS) are associated with demyelination and remyelination processes. The most frequent demyelinating disease is multiple sclerosis (MS), characterized by recurrent episodes of demyelination resulting in neuro-axonal degeneration. To understand the underlying mechanisms of these processes, a variety of models have been developed [

1]. Among toxin-induced models of demyelination, a cuprizone-induced model attracted prominent interest due to good reproducibility in contrast to other models of MS [

2]. The cuprizone diet causes primary oligodendrocyte apoptosis and secondary demyelination of nerve fibers. The demyelination is accompanied by a mitochondrial dysfunction and oligodendrocyte loss, and results in the formation of multiple lesions in different brain regions enriched by white (corpus callosum, superior cerebellar peduncles) and grey matter (cortex, cerebrum and cerebellum). The demyelination and inflammation processes in the CNS are accompanied by reactive astrogliosis, peripheral macrophage recruitment, and progenitor cell activation [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Thus, the cuprizone model of demyelination triggers all these complex processes in the CNS.

Historically, a majority of publications suggested that the blood-brain barrier (BBB) stays intact during cuprizone intoxication [

7]. However, this statement is based on a few studies conducted in the 1980s and earlier [

8,

9,

10]. Namely, in 1969 Suzuki and colleagues injected a toluidine dye Trypan Blue into two cuprizone-intoxicated mice with encephalopathy symptoms in order to check the BBB integrity in the treated mice [

9]. They did not detect any accumulation of Trypan Blue in the mouse brain and concluded that the BBB was not compromised. But the peculiarities of this investigation should be taken into consideration: 1) the use of 3-4-weeks Swiss-Webster strain of mice (major publications used C57Bl6 mice in their experiments), 2) the cuprizone treatment of mice only for 2 weeks, and 3) insufficient number of animals in the study (only two mice out of 40 demonstrated encephalopathy symptoms during the cuprizone diet and were used for subsequent investigation of BBB integrity). However, later it was shown that the severity and reproducibility of demyelination strongly depend on the animal strain and age. Hiremath et al. (1998) published a key study in which they determined that cuprizone feeding of 8-week old C57BL/6 mice consistently induced demyelination with minimal clinical toxicity. Since then cuprizone-induced model using C57BL/6 mice became the most used variant of the cuprizone model due to its relatively high reproducibility. Moreover, the length of time on the diet is important for demyelination; subsequent studies have shown that maximum demyelination was achieved no earlier than 4-6 weeks on the cuprizone diet. Later the permeability of the BBB for macromolecules in the murine cuprizone model has been studied by two groups, Akira Kondo and Suzuki, Bakker and Ludwin [

8,

10]. They showed that the BBB in the area of demyelinated nerve fibers is not permeable to horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 40 kDa) within 30 or 60 minutes after intravenous injection of HRP. Immunochemical analysis of brain slices using antiserum to detect serum proteins reaffirmed that there was no BBB breakdown [

10]. A panel of different methods (e.g., electronic microscopy, histological evaluation) supported the obtained result. The authors used a brain injury model as a positive control for increased BBB permeability in these studies.

Later on, a number of publications demonstrated results that could be explained by the increased permeability of the BBB in the cuprizone model. For example, Hedayatpour et al. showed that intravenously transplanted adipose mesenchymal stem cells could migrate into the demyelinated lesion in the murine cuprizone model [

11]. However, it is known that intravenously administrated cells are unlikely to migrate across the healthy BBB because the BBB would prevent access of cells and a majority of molecules to the parenchyma. The authors suggested that focal demyelination might induce chemoattractant signals that promote the accumulation of mesenchymal stem cells in the brain [

11]. But we suggest that it also could be explained by the disruption of the BBB in the demyelinated area in cuprizone-treated mice. Also, peripheral macrophages and a low number of recruited T cells were observed in the corpus callosum of cuprizone-treated mice [

3,

5]. Nevertheless, their findings could also indicate the increased BBB permeability in the cuprizone model.

Nowadays, BBB integrity in the cuprizone model remains a topic of debate. Some researchers claims that BBB remains intact in cuprizone model, while other observed signs of increased BBB permeability in their studies. Thus, Monokesh K. Sen et al. [

12] state that BBB remains intact based on recent both histological and proteomic investigations of other researchers [

13,

14,

15]. Tejedor et al. did not observe any accumulation of Evans blue dye in cuprizone-treated mice [

15], while Shelestak et al. observed accumulation of Evans blue in early phase of cuprizone model and suggested mechanism of increased BBB permeability [

16]. Berghoff et al also questioned BBB integrity and proposed that BBB hyperpermeability precedes demyelination in the cuprizone model [

17].

Martin Zirngibl et al. (2022) asserted that BBB remains largely intact in the cuprizone model, but also suggested that the altered BBB integrity may permit infiltration of leukocytes. [

18]

. All these contradictory results led us to the idea that the increased permeability of the BBB for macromolecules in the cuprizone model may be slight and local, and could be detectable using sensitive methods, such as molecular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or confocal microscopy. Moreover, tracers with high fluorescence intensity can improve chances of detecting the local increased permeability in the BBB during cuprizone-induced demyelination. Therefore, in this study we investigated BBB permeability for macromolecules using injections of Evans Blue, Alexa Fluor™ 488-labeled specific antibodies to GFAP, and gadolinium-labeled antibody conjugates in healthy or cuprizone-treated mice. The accumulation of these tracers in the brains of animals was evaluated by immunohistochemical and MRI analysis. Our results suggest that BBB integrity is compromised in the white matter of brain in cuprizone model of demyelination (in particular corpus callosum).

2. Results

2.1 Validation of the cuprizone model of demyelination in mice

Experimental design and body weight changes. Demyelination of nerve fibers in the brain of C57BL/6 male mice was induced by cuprizone intoxication using a rodent chow containing 0.6 % cuprizone [

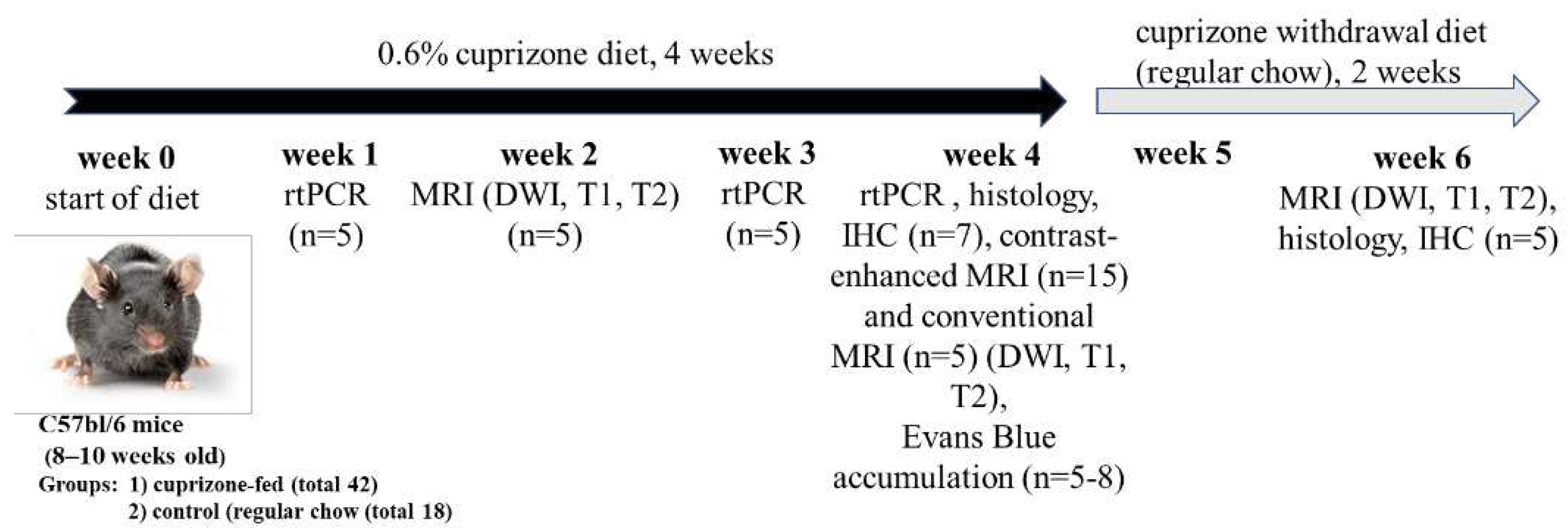

19]. Experimental design and number of animals per group are indicated at

Figure 1. The cuprizone-treated animals demonstrated a steady decrease in body weight, and by the 4th week of the cuprizone diet their weight loss significantly differed compared to healthy mice (24.3 ± 0.8 g vs. 27.8 ± 0.3 g) (Supplementary materials,

Figure S1).

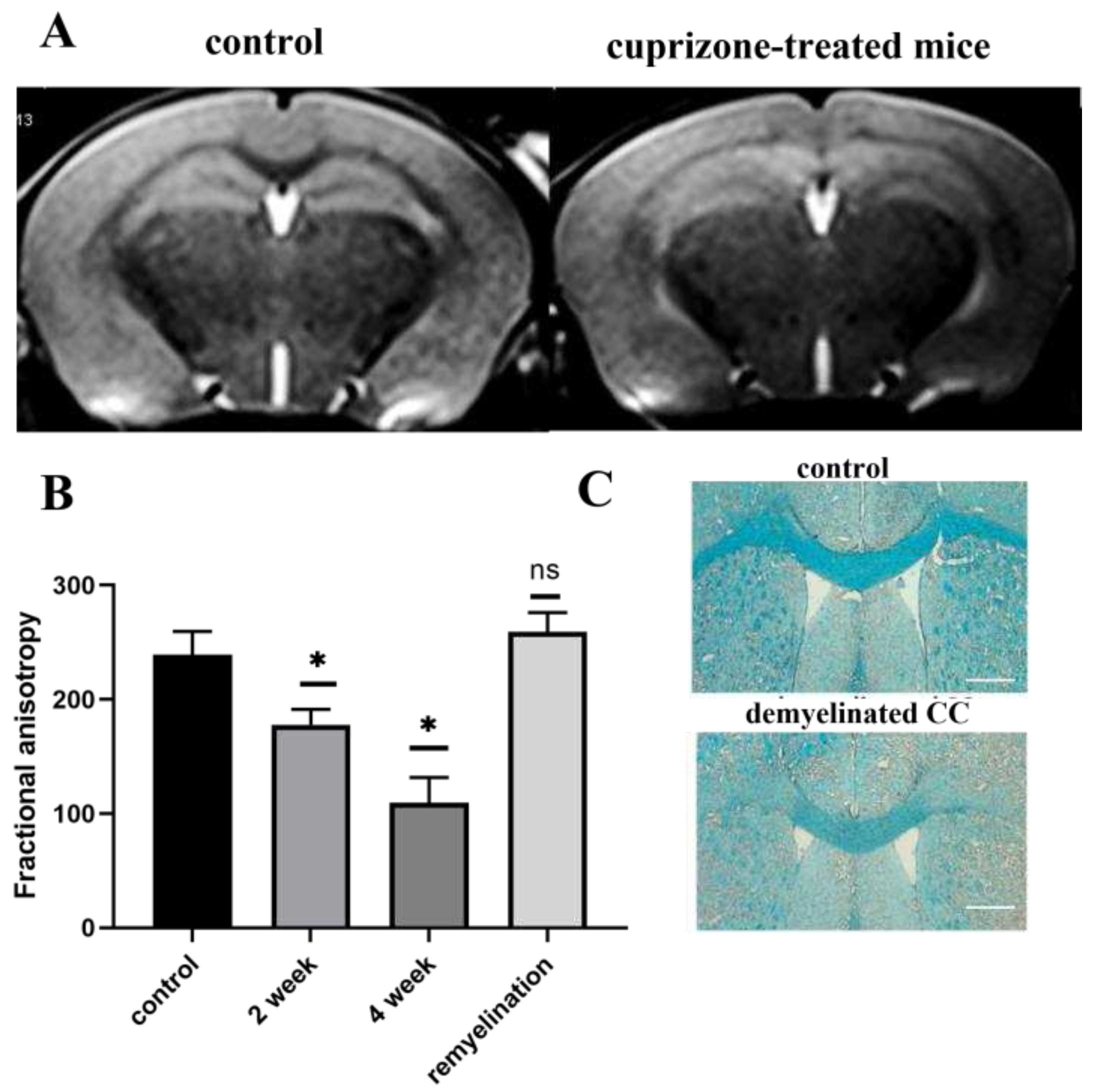

MRI and histological evaluation of cuprizone-induced demyelination. Т2-weighted MRI images revealed pathological lesions in the corpus callosum of mice treated with cuprizone compared to non-treated mice at the 4th week of the diet (

Figure 2a). As expected, 2 weeks after termination of cuprizone diet, the signal intensity of Т2-weighted MRI images increased, reflecting remyelination process. We also performed a diffusion MRI to determine brain fiber structure using water diffusion properties as a probe. The calculated values of the fractional anisotropy obtained from the diffusion tensor MRI imaging reflects disturbance of the cellular structure and is widely used to measure connectivity in the brain and estimate the white matter damage (i.e. demyelination). In our study, the fractional anisotropy in the brains of cuprizone-treated animals decreased by 2 times at the 4th week of cuprizone diet, followed by restoration to its original values during the remyelination (

Figure 2b). Histological staining of myelin by the Luxol Fast Blue also demonstrated the demyelination in the brain of cuprizone-treated mice.

Figure 2c shows that the amount of myelin in the corpus callosum was significantly reduced in the treated animals after 4 weeks of the cuprizone diet (

Figure 2c).

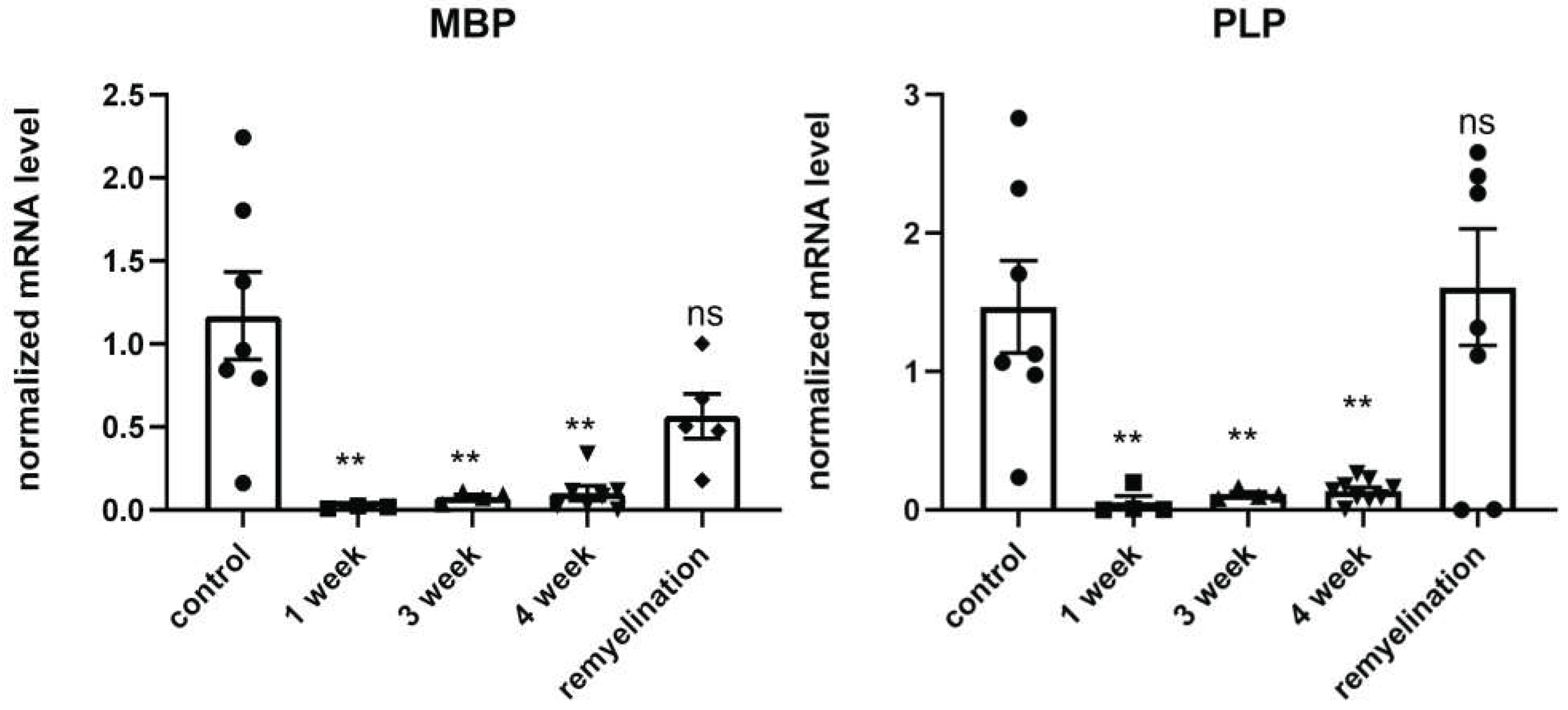

Analysis of myelin proteins by real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR). Gene expression of MBP and PLP, which together account for 90% of all myelin proteins in the brain, were analyzed by rt-PCR.

Figure 3 demonstrates the significant reduction of MBP and PLP expression after the first week of the cuprizone diet. Throughout the entire cuprizone-feeding period (4 weeks), there was a decrease in expression of these proteins, which reflects demyelination. The expression levels increased or returned to the initial levels after the termination of the diet. These results also corroborate that the cuprizone diet used in this study reflects the demyelination process in the CNS, as observed by others [

20,

21].

Immunostaining of GFAP and VEGFR2 of cuprizone-injured brain. It is known that demyelination is accompanied by increased astrocyte reactivity, and inflammation and demyelination processes in glia are characterized by elevated GFAP expression (

Figure S6) [

4,

22,

23,

24]. Using immunofluorescence staining with pAb anti-GFAP, we detected an increase in GFAP expression after 4 weeks of cuprizone exposure, indicating the strong glial reaction (

Figure S6B). However, the astroglial reactivity did not normalize after the cuprizone withdrawal, and the remyelination was also accompanied by increased GFAP expression (

Figure S6C). The high expression of GFAP during demyelination was taken into account in our further experiments, where we analyzed vascular permeability of the BBB during demyelination using specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb) to GFAP.

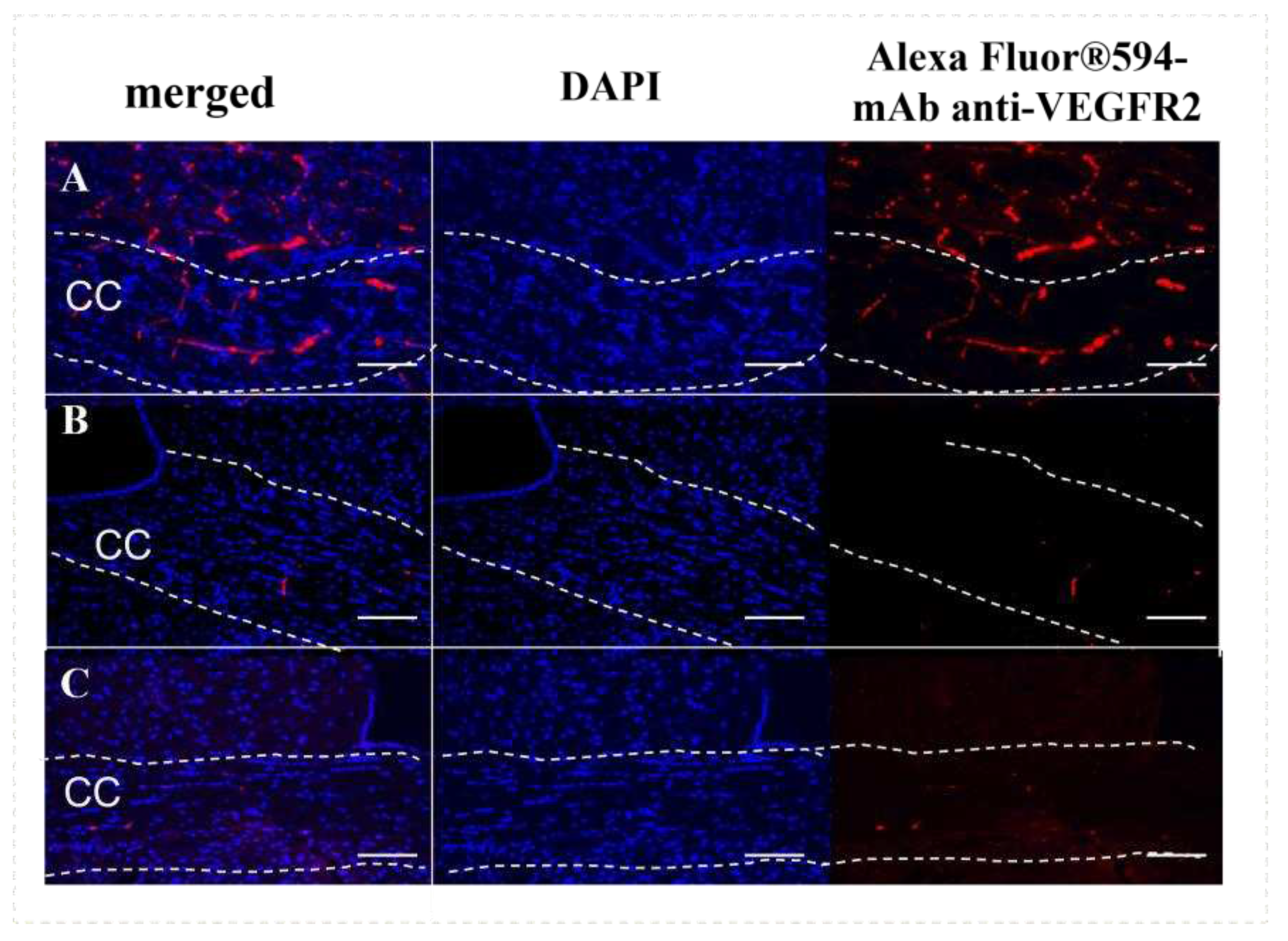

We also investigated the expression of VEGF receptor (VEGFR2) during demyelination and remyelination, because VEGF and its receptors are the main regulators of angiogenesis and vascular permeability. It has been shown that high expression of one of the VEGF receptors, Flt-1 (VEGFR2), in endothelial cells and astrocytes is associated with micronecrosis during a brain injury and plays a role in the disruption of the BBB [

25]. In our study we detected the high expression of VEGFR2 mostly in the vessels of the brain cross-sections of cuprizone-treated mice on the 4th week of the diet. This elevated VEGFR2 expression at the demyelination stage probably reflects the cuprizone-mediated damage and apoptosis of oligodendrocytes in the corpus callosum and might be associated with the BBB disruption (

Figure 4A). After the cuprizone withdrawal, the expression of VEGFR2 in the brain reduced, reflecting the recovery process (

Figure 4B) [

26].

2.2. Detection of Evans Blue dye in the brain of cuprizone-treated mice

To compare our results with previous studies on the BBB permeability, we followed the conventional protocol using Evans Blue dye [

27]. Evans Blue is an isomer of Trypan blue with higher half life time in the blood (>120 min), and similar to Trypan blue, it binds to plasma proteins and reflects albumin leakage through the impaired BBB [

28]. After i.v. injection of Evans Blue, first the whole brain samples were scanned using an IVIS imaging system (

Figure S3A). Then the dye was extracted from the brain homogenates, and its concentration was analyzed by a fluorescence reader VictorX3 (PerkinElmer, USA). There was no fluorescence detected by both methods in the control (intact brain) and experimental group of mice (cuprizone-treated). We assumed that the sensitivity of the IVIS Spectrum CT or fluorescence reader VictorX3 was insufficient for detection of a small amount of albumin-bound Evans Blue that might leak through the disturbed BBB. In comparison, the fluorescence analysis of brain with significant BBB impairment (glioma C6) demonstrated significant fluorescent signal as detected by IVIS Spectrum CT (Supplementary material,

Figure S3B). We also prepared solutions of Evans Blue at different concentrations and analyzed the fluorescence of these samples by both methods. There was almost no fluorescence detected in samples at the concentrations typically delivered to the brain (approximately 20 µg/ml, or 0.2% of injected dose was about 37000 a.u); however, the fluorescein at the same concentration was 25 times higher (about 970000 a.u.). This result indicates that either the fluorescence intensity of this dye at such low concentrations is not enough to detect or the sensitivity of the equipment is insufficient, suggesting that the leakage of Evans Blue could be missed previously due to inadequate detection methods.

2.3. Accumulation of antibody-conjugates in the brain of cuprizone-treated mice

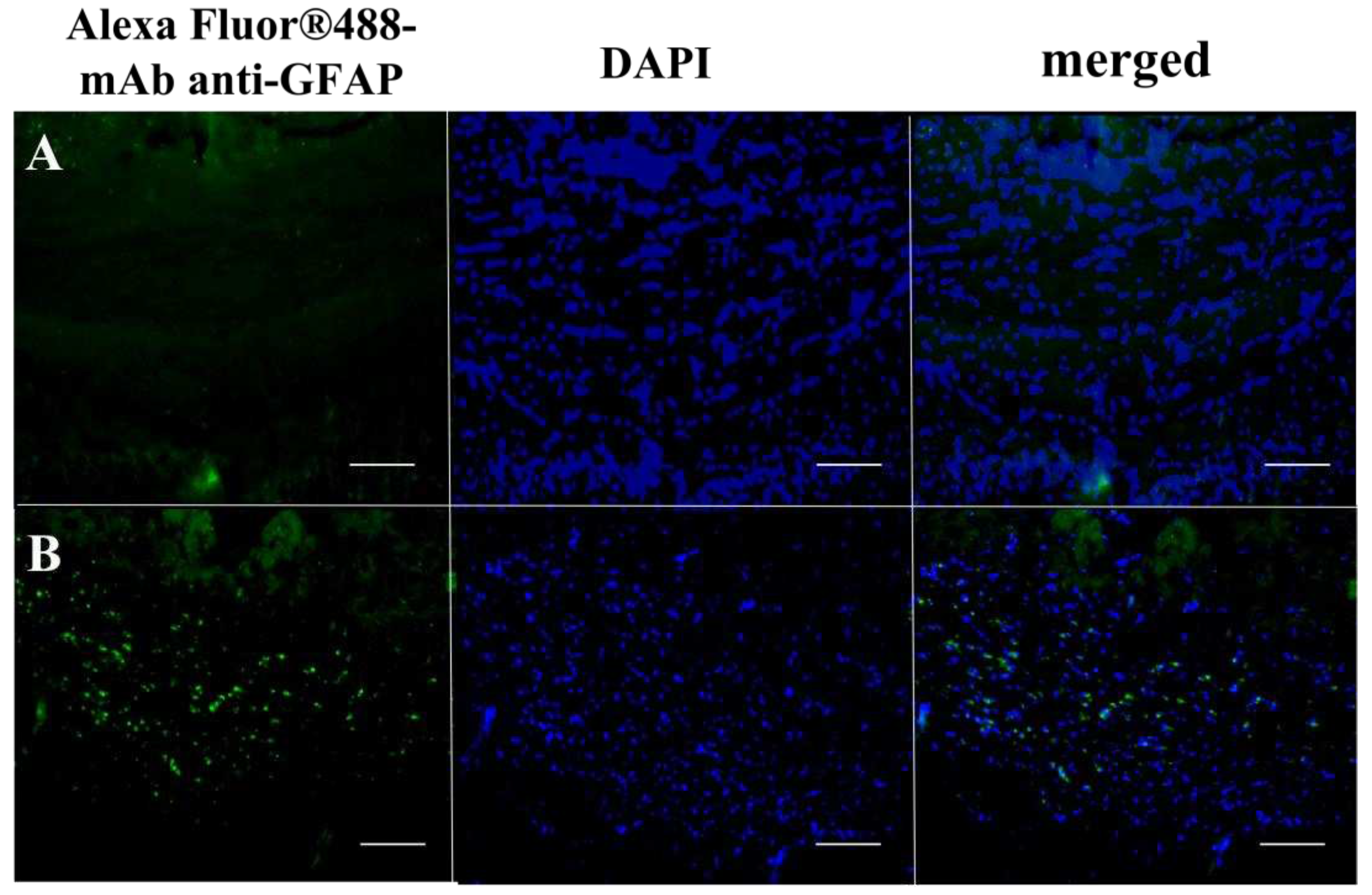

To analyze accumulation of macromolecular conjugates in the brain of cuprizone-treated mice, we used monoclonal antibodies to GFAP, which are overexpressed in the reactive astrocytes at the 4th week of the diet (

Figure S6B). We labeled specific mAb GFAP and non-specific IgG by a fluorescent dye, Alexa Fluor ™ 488, using carbodiimide chemistry. Non-specific IgG-conjugate was used as a control. At 12 and 24 hours after i.v. injection of these fluorescently labeled antibodies, the significant accumulation of the specific mAb GFAP was observed in the corpus callosum of cuprizone-treated mice in comparison with control mice (intact brain),

Figure 5. We also observed some penetration through the BBB of non-specific IgG-conjugated contrast agents during the demyelination stage reflecting the increased BBB’s permeability (

Figure S5). Its minor retention in tissue could be also explained by non-specific binding of IgG to corpus callosum at demyelination stage that was shown in immunofluorescent analysis (Supplementary material,

Figure S2).

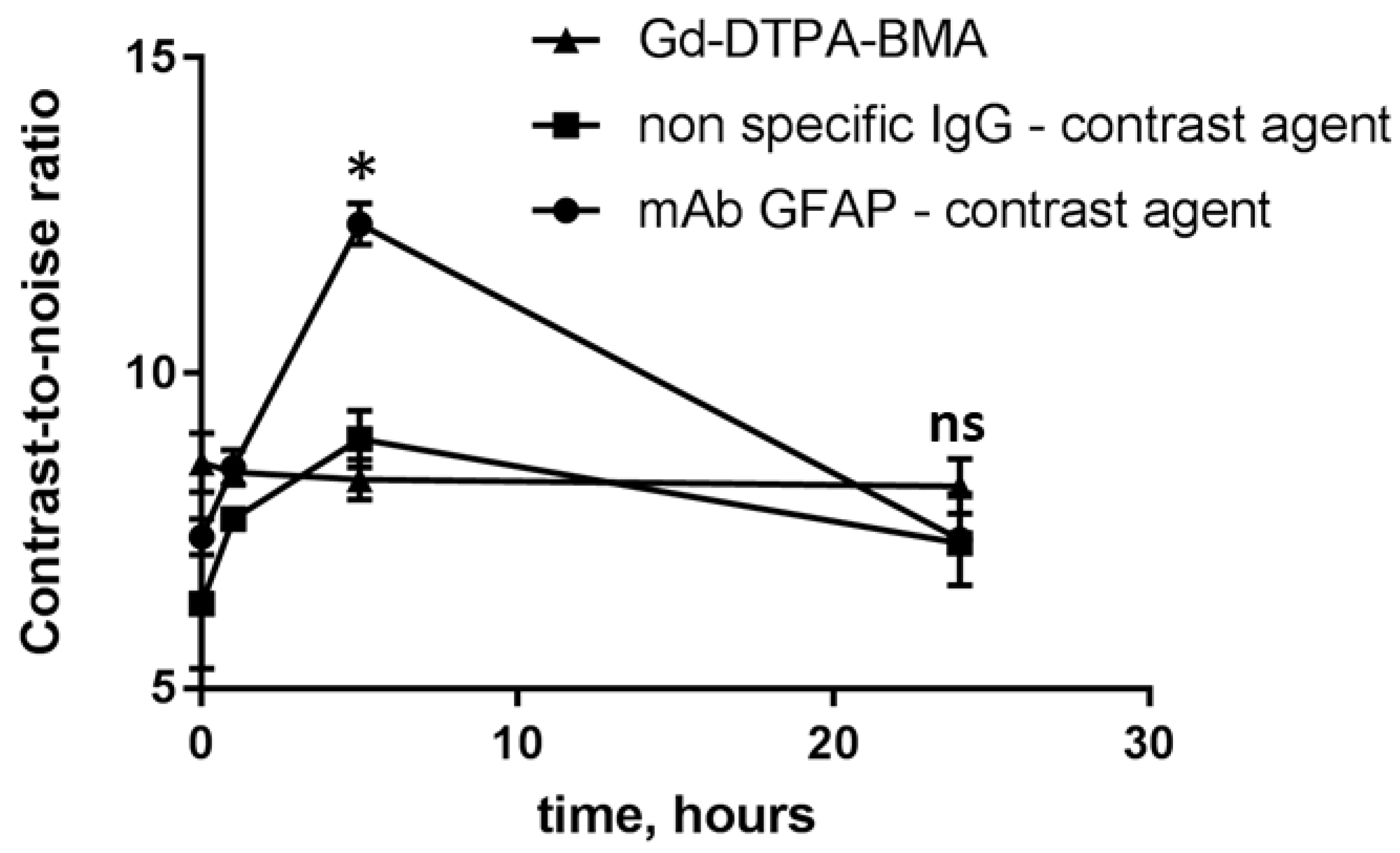

Then we synthesized mAb GFAP- and IgG-conjugated Gd-based contrast agents for MRI monitoring of their accumulation in the brain. We compared the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) values in the demyelinated area of the corpus callosum after i.v. injection of the contrast agents. The enhanced accumulation of the specific mAb GFAP-conjugated contrast agent was also observed in the corpus callosum compared to non-specific IgG contrast agent or the conventional agent Omniscan®. The CNR values for both non-specific contrast agents (IgG conjugate and Omniscan®) increased up to 20% relatively the initial CNR values. Meanwhile, the CNR values for the specific mAb-GFAP-contrast agent were 3 times higher than that for controls at 5 h post-injection (

Figure 6).

3. Discussion

The cuprizone-induced model of demyelination in mice is still among the most popular approaches for modeling of the CNS diseases associated with demyelination and remyelination. However, there is still no consensus on BBB integrity during the cuprizone diet.

In fact, there are currently three different opinions on BBB integrity in the cuprizone model: positive («disrupted BBB»), neutral («relatively intact BBB», «limited BBB permeability»), and negative («intact BBB»). This diversity of opinions is reflected in the literature. However, some results are controversial and suggest that increased BBB permeability is induced by the cuprizone diet [

16,

17]. Here, we decided to explore the permeability of the BBB in the cuprizone-treated mice for macromolecules, in particular antibody-conjugates.

First, we validated our cuprizone-induced model of demyelination by tracking changes in performing MRI, histological evaluation of mice brains, and accessing gene expression of MBP and PLP proteins in the brains. The development of pathological lesions in the corpus callosum of cuprizone-fed mice was confirmed by T2-weighted MRI after 4 weeks of the cuprizone diet. This process was accompanied by myelin loss (Luxol Fast Blue staining) and a decrease of levels of myelin proteins (MBP and PLP-gene expression) as detected by histological and rt-PCR analysis. Moreover, we observed the high expression of GFAP in the corpus callosum using immunohistochemical analysis. It has been shown that the cuprizone-induced demyelination accompanies reactive astrogliosis, and the increase of GFAP expression in the grey and white matter of the cerebrum can be detected even after 3 weeks of the 0.2% cuprizone diet in C57BL/6 mice [

4]. We observed the enhanced amount of GFAP-positive astrocytes in the demyelinated lesions not only at the 4th week of demyelination but also during remyelination stage, 2 weeks after the diet termination. These results are consistent with the published data confirming that astrocyte reactivity does not normalize rapidly and persists in combination with extensive spontaneous remyelination [

22]. Thus, our results confirmed the relevance and high reproducibility of the cuprizone model in mice.

To study BBB integrity, we analyzed the accumulation of three different macromolecules in the brains of mice treated with cuprizone in comparison with healthy mice. It is known that accumulation of macromolecules is possible only in cases where the BBB has been compromised (e.g., brain injury, brain tumor) [

29,

30]. Thus, we studied the accumulation of traditional Evans Blue, fluorescently labeled antibodies and antibody-conjugated Gd-based contrast agents using a variety of methods (confocal microscopy, in vivo imaging IVIS and MRI analysis).

Evans Blue is often used to verify the increased permeability of the BBB to macromolecules due to its a very high affinity to serum albumin. Historically, the accumulation of albumin-bound Evans Blue is evaluated by extraction of the dye from the brain followed by fluorometric analysis [

27]. At 4 hours after intraperitoneal injection of Evans Blue, we did not detect significant difference between the control and cuprizone-treated mice using the standard protocol [

31]. Similar results were obtained by others [

15], indicating either a lack of or very weak permeability of the albumin-bound Evans Blue across the BBB. However, Berghoff et al. demonstrated a minor localized accumulation of Evans Blue in the cuprizone-treated brain, indicating minor loss of BBB integrity [

17]. Also,

Shelestak et al. (2020) observed an accumulation of Evans blue in an early phase of the cuprizone model [

16]

. However, peculiarities of Evans blue as tracer for altered BBB integrity in different studies should be taken into account, i.e. variation of injected doses (most common is 2% EB, 2-4 ml/kg) and detection methods. In particular, Saunders et al (2015) published a critique of EB as tracer for assessment of BBB hyperpermeability [

32]. He mentioned that high dose of EB leads to presence of free dye in plasma and its binding to the tissue that will cause misinterpretation of results and suggested to use other tracers with better sensitivity. We agree and suggest that other methods are likely to be more accurate and probably can detect even small amounts of the dye that were previously overlooked. We tested different concentrations of Evans Blue in order to determine the minimal detectable concentration for the standard extraction method. We verified that sensitivity of the standard method (techniques and/or dye) is not enough for detection of accumulated Evans Blue in the demyelinated lesions after the cuprizone diet compared to brain tumors, namely glioblastoma multiforme.

In order to capture the marginal accumulation of macromolecules in the brain of cuprizone-treated mice, we intravenously injected monoclonal antibodies to GFAP labeled with the stable and sensitive dye Alexa Fluor 488 and performed confocal analysis of the brain cross-sections. After 12 and 24 hours after i.v. injection, we observed localized accumulation of the fluorescent labeled antibodies in the demyelinated lesions compared to control. This accumulation could be a sign of small localized gaps in the BBB in demyelinating are after micro-necrosis of oligodendrocytes. In addition, the high expression of GFAP detected in the demyelinated lesions can be associated with increased extracellular space and loss of contact between astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, or astrocytes and myelin sheaths [

33]. Recent studies suggested that mechanism of BBB disruption in cuprizone model is also associated with microglial and astrocytic activation [

34]. Activated astrocytes release cytokines, chemokines, and other factors that contribute to cuprizone-induced demyelination. Petra Fallier-Becker et al. (2022) showed that BBB impairment in cuprizone model related to changes in astrocyte endfeet and AQP4 isoform expression [

35]. Shelestak et al. observed that activation of mast cells associated with highest levels of BBB permeability and could potentially mediate BBB disruption [

16]. Moreover, we also observed the increased amount of VEGFR2 in the brain at the 4th week of the cuprizone model, which could be associated with BBB disruption, since VEGFR2 is the main signal transducer in endothelial cells [

36] and its level indicates the vascular permeability in different models [

37], such as brain injury and brain tumors [

38]. It was shown that high amount of VEGFR2 could cause BBB disruption via c-Src activation.

To confirm the results of fluorescent microscopy, we performed MRI analysis and compared the CNR and fractional anisotropy values in the brains of cuprizone-fed and healthy mice. In order to trace a macromolecular contrast agent, we conjugated specific monoclonal antibodies to GFAP or non-specific IgG with Gd-based contrast agent (PLL-DTPA-Gd)[

18]. MRI analysis revealed the accumulation of macromolecular contrast agents in the corpus callosum at the acute phase of demyelination in 5h after injection, regardless of the specificity of the contrast agent (both specific mAb to GFAP and non-specific IgG had increased CNR values). However, the specific GFAP-conjugated contrast agent had enhanced accumulation than that of non-specific IgG-conjugated contrast agent, confirming the overexpression of GFAP in the demyelinated lesions. These results could indicate not only local increased BBB permeability in demyelinated corpus callosum, but also utilization of cuprizone model for targeted drug delivery studies. Moreover, low molecular weight contrast agents (Gd-DTPA-BMA) also had slightly increased CNR values in the pathological site. Contrary results was obtained by Boretius et al (2012), who did not observe accumulation of Gd-DTPA contrast agent in cuprizone model [

39] , however, this difference could be explained by small changes in CNR that could be hard to detect visually by person.

Our data revealed a local BBB disruption and permeability of the BBB to macromolecules, namely for different antibody-conjugates, in demyelinated corpus callosum as detected by fluorescent microscopy and MRI analysis. However, we did not observe any detectable amount of Evans Blue in the CNS of cuprizone-treated mice using the standard protocol of dye extraction, consistent with the literature. Therefore, it is probably possible that extravasation of Evans Blue dye into the brain is local and marginal for detection using conventional protocols; technologies and tracers with better detection limit might help to detect the local BBB hyperpermeability. Thus, using other methods we were able to detect accumulation of various macromolecules in the brain, suggesting that BBB integrity is compromised in the cuprizone model of demyelination.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Bis(cyclohexanone)oxaldihydrazone (C9012), gadolinium chloride hexahydrate (GdCl3, G7532), Luxol Fast Blue solution, non-specific IgG from mouse serum, polylysine (15-30 kD, SIP7890), diethylenpentaacetic acid (D1133) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Paraformaldehyde was provided by Pancreac (141451.1211). Polyclonal antibodies (pAb GFAP) and monoclonal antibodies (mAb GFAP) to glial fibrillar acidic protein, monoclonal antibodies to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (mAb VEGFR2) were obtained by hybridoma technology (custom-made materials will be shared upon reasonable request). Alexa 594™-goat-anti-mouse antibodies, Alexa 488™-goat-anti-mouse antibodies were obtained by Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Antibodies were validated by its binding efficacy in ELISA assay.

4.2. Experimental design and modeling of cuprizone-induced demyelination

All studies on animals were approved by an Ethical Committee of the Serbsky National Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology (Approval #5). C57BL/6 male mice were obtained from «Andreevka», Federal Scientific Center of biomedical technologies, Moscow, Russia. All mice were divided into the cage per group (n=5-7 per group, total number of mice = 60). Behavioral changes and MRI measurements was analyzed by single-blind method, other experiments were performed, and results were interpreted by the same experimenter. Demyelination was induced by feeding 8–10 weeks old mice with a diet, containing 0.6 % cuprizone, mixed into a ground standard rodent chow for 4 weeks. Control animals were fed powdered chow only. Water was given ad libitum. All animals were weighted every 3 days. Behavioral changes were assessed at the 1, 2, 4 weeks of cuprizone diet and 2 weeks after cuprizone retrieval on male and female groups of mice (n=5-6 mice per group). To minimize animal suffering during experiments mice were anesthetized either isoflurane (MRI study), or zoletil/xylazine anesthesia (other types of experiments). For histological evaluation (section 2.4, 2.5, 2.7, 2.8) the mice were anesthetized (Zoletil 50 mg/kg, xylazine 5 mg/ml) and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7.4 at room temperature (RT). Then brains were removed and kept in PFA 4% in PBS overnight and afterwards in sucrose 30% in PBS for a minimum of 24 hours. Coronal sections (20-30 µm) were cut with a Cryostat (MNT Slee, USA). No exclusion of animals was used in statistical analysis.

4.3. RT-PCR analysis

For gene expression analysis mice were killed by rapid decapitation. MBP (myelin basic protein), PLP (proteolipid protein), GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) expression in the brain tissue was assessed at the 1, 2 and 4 weeks of cuprizone diet (demyelination period) as well as 2 weeks after cuprizone withdrawal (remyelination period) by RT-PCR (n=5 per group). Samples were prepared from brain hemispheres by homogenization in a Tissue Lyser LT (Qiagen, USA) Subsequently RNA was isolated using the phenol-chloroform extraction method in an automated Qiacube system (Qiagen, USA). RNA concentration was determined sprectrophotometrically by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher, USA). We used 500 ng of total RNA and 20 μl of random decamer primer for the first strand cDNA synthesis from an RNA template (MMLV RT kit, Eurogen, Russia). mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene (HPRT1) and to the average value of the control group where needed. Specific primers are listed in

Supplementary Table S1. Real time PCR was run on a StepOne instrument (Applied Biosystems, USA). ∆∆Ct method was used to calculate relative expression of gene of interest (MBP, PLP).

4.4. Luxol Fast Blue staining

Luxol Fast Blue staining of cuprizone injured brain was performed to prove demyelination. For this purpose brain sections were incubated with Luxol Fast Blue working solution for at least 2-4 hours (56°C) and then standard protocol was followed (Burke 1968). Images of corpus callosum were obtained by light microscopy (Leica, Germany).

4.5. Immunohistochemistry of GFAP and VEGFR2

Immunofluorescence analysis of GFAP and VEGFR2 was carried out on brain sections of mice with cuprizone-induced demyelination at different time points (1 and 4 weeks of demyelination, 2 weeks of remyelination). For this purpose standard protocol was followed [

40]. Briefly, frozen brain sections with 30 µm thickness were pre-incubated with 5% goat serum (30 min, 37°C), washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), containing 0.2% Tween 20 and 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBSTT), and incubated with appropriate primary antibodies (pAb GFAP or mAb VEGFR2, 4°C, overnight).Then brain sections were washed with PBSTT, incubated with Alexa Fluor 594™ - goat - anti - rabbit - antibodies (for pAb GFAP) or with Alexa Fluor 594™ - goat - anti - mouse - antibodies (for mAbVEGFR2) and counterstained with DAPI. Images were obtained using confocal microscopy (Nikon A1 MP, Japan). Quantification of GFAP+ cells was determined by applying binary layers to a threshold of the fluorescence intensity. The lower threshold intensity was equated to background noise of control. Next, the area with target cells in µm was analyzed using NIS Elements AR software.

4.6. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

To prove demyelination T2-weighted images were obtained on the 1, 2, 4 weeks of cuprizone exposure and 2 weeks after diet. Animals were anesthetized throughout the whole procedure with the E-Z Anesthesia system (EZ-7000 330, PA, USA) with 2-3% isoflurane. For T2-weighted images Turbo Spin Echo sequence with following parameters was used: TR= 3250 ms, TE =43, Turbo factor = 9, FOV =20x16.25 mm, base resolution = 192x163, number of acquisitions = 5. For T1 weighted images FLASH 2D sequence with following parameters was used: TR= 450 ms, TE =4.54, flip angle = 70, FOV =20x16.25 mm, slice thickness = 0.7, base resolution = 192x163, number of acquisitions = 5

Efficacy of signal contrast enhancement from pathological lesions was investigated at the 4th week of the cuprizone treatment. For this purpose, GFAP-targeted contrast agents were intravenously (i.v.) injected at a dose 0.2 mmol Gd/kg. The contrast agents conjugated with nonspecific mouse immunoglobulins (IgG), as well as a commercial contrast agent OmniScan® (Gd-DTPA-BMA) were used as controls. T1-weighted images were obtained before and at 1, 5, 24 hours after injection of contrast agents.

Signal intensities of the injured corpus callosum and other brain tissues (caudoputamen or cortex) of cuprizone-injured mice were measured using SyngoFastViewer (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and MultiVox Viewer (GammaMed, Moscow, Russia) software. Contrast enhancement of signal from pathological lesions (contrast-to-noise ratio, CNR) for each time point was calculated according to the following equation: CNR = (SICC-SI noise)/SI noise, where SICC – averaged signal intensities of the corpus callosum, SInoise - averaged signal intensities of noise (in the air).

4.7. Analysis of Evans Blue accumulation

Evans Blue (2 mg/ml, 20 ml/kg) was intraperitoneally injected (i.p.) to the mice with cuprizone-induced demyelination on the 4th week of modeling. After 3 hours, mice were sacrificed and perfused with ice-cold PBS, and brains were monitored using IVIS Spectrum CT. For spectral unmixing of Evans Blue fluorescence from tissue auto-fluorescence the following excitation and emission filters were used: For 605 nm excitation filter and 660-740 nm emission filters were used. For 640 nm excitation filter 680-760 nm filters were used. Spectral unmixing was performed using Living Image 4.4 software in manual mode. After the IVIS imaging brains were homogenized, centrifuged and Evans Blue was extracted using trichloroacetic acid as described previously [

27].

4.8. Accumulation of antibody conjugates

To evaluate permeability of BBB we injected two types of antibody-drug conjugates via femoral vein: 1) fluorescently labeled mAb GFAP-Alexa 488™ and 2) mAb GFAP labeled with GdCl

3 by PLL-DTPA linkers. For the first type of conjugate standard protocol of conjugation tracer with monoclonal antibodies was followed (Life Technologies, USA) [

41]. Synthesis of the GFAP-targeted contrast agents was conducted as previously described [

42]. Briefly, PLL-DTPA conjugates were prepared using [DTPA]:[Lys] ratio = 1:1. After that, monoclonal antibodies to GFAP (mAb GFAP) were covalently bound with PLL-DTPA (molar ratio [mAb]:[PLL-DTPA] was 1:10) and complexed with GdCl3. Obtained mAb GFAP-conjugates were purified by gel filtration chromatography (Sepharose CL-6B, HEPES) from unbounded reagents, sterilized (0.45 µm, Millipore) and stored until further use.

4.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPrism 8 software. One-way Anova with Bonferroni correction were used to analyze the data sets. No randomization was performed to allocate subjects in the study. No exclusion criteria were pre-determined.

Author Contributions

preparation of manuscript, synthesis of antibody-conjugates, T.A.; behavioral experiments, PCR analysis, A.K. and P.K.; contrast -enhanced MRI studies of cuprizone -treated mice, M.A.; statistical analysis, D.P.; immunohistochemical analysis of GFAP, microscopy, P.M., modeling of demyelination using cuprizone, K.I.; diffusion tensor imaging of cuprizone-treated mice, I.G.; monoclonal antibody purification, O.G.; analysis of results, preparation and editing of manuscript, N.N. and V.Ch..