Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-generation diffusion

2.2. Marketing factor in diffusion process

3. The model

3.1. The brand competition diffusion

3.2. Separation of consumer behaviors under multi-generation diffusion

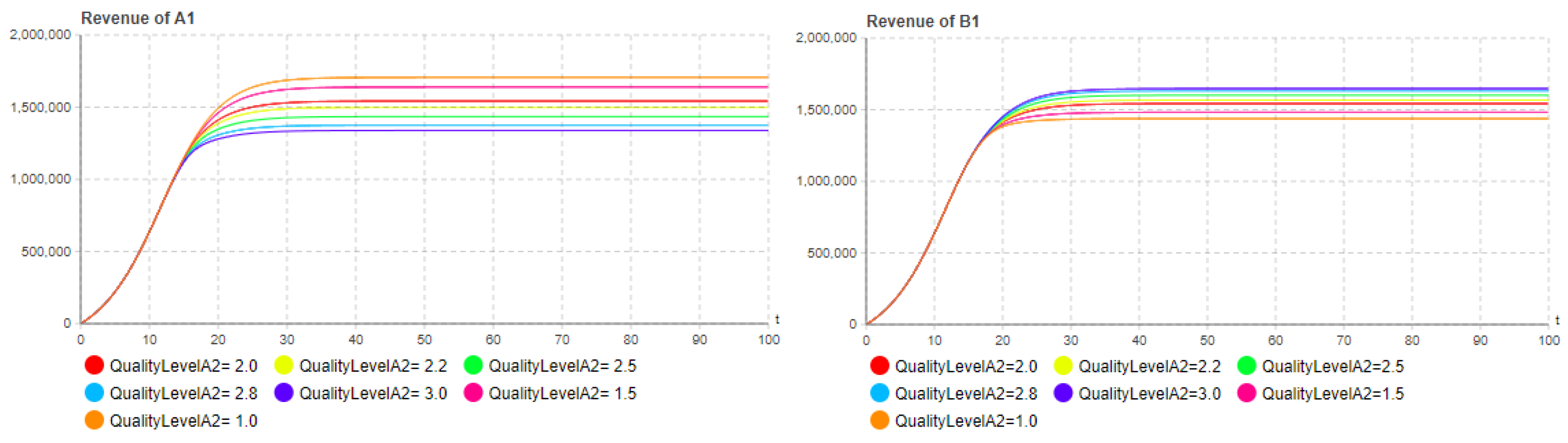

4. The system

| Notation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Mi | Total market size of each generation products |

| kji | The quality level of each j brand and i generation products |

| Brand value spillover effect coefficient | |

| Advertising coefficient of each j brand and i Generation products | |

| Word-of-mouth influence coefficient of each j brand and i generation products | |

| Each j brand of i generation product dynamic price (price changes) | |

| Nji(t) | The cumulative diffusion number of each j brand and i Generation products at time t |

| Sji(t) | The cumulative sales volume of each j brand and i Generation products at time t |

| πj | Total revenue of two generations of each brand j products |

| βj | Price sensitivity coefficient of each j brand |

| Second generation products launch time | |

| R | Diminishing price factor |

| r | Product income discount factor |

| T | Simulation termination time |

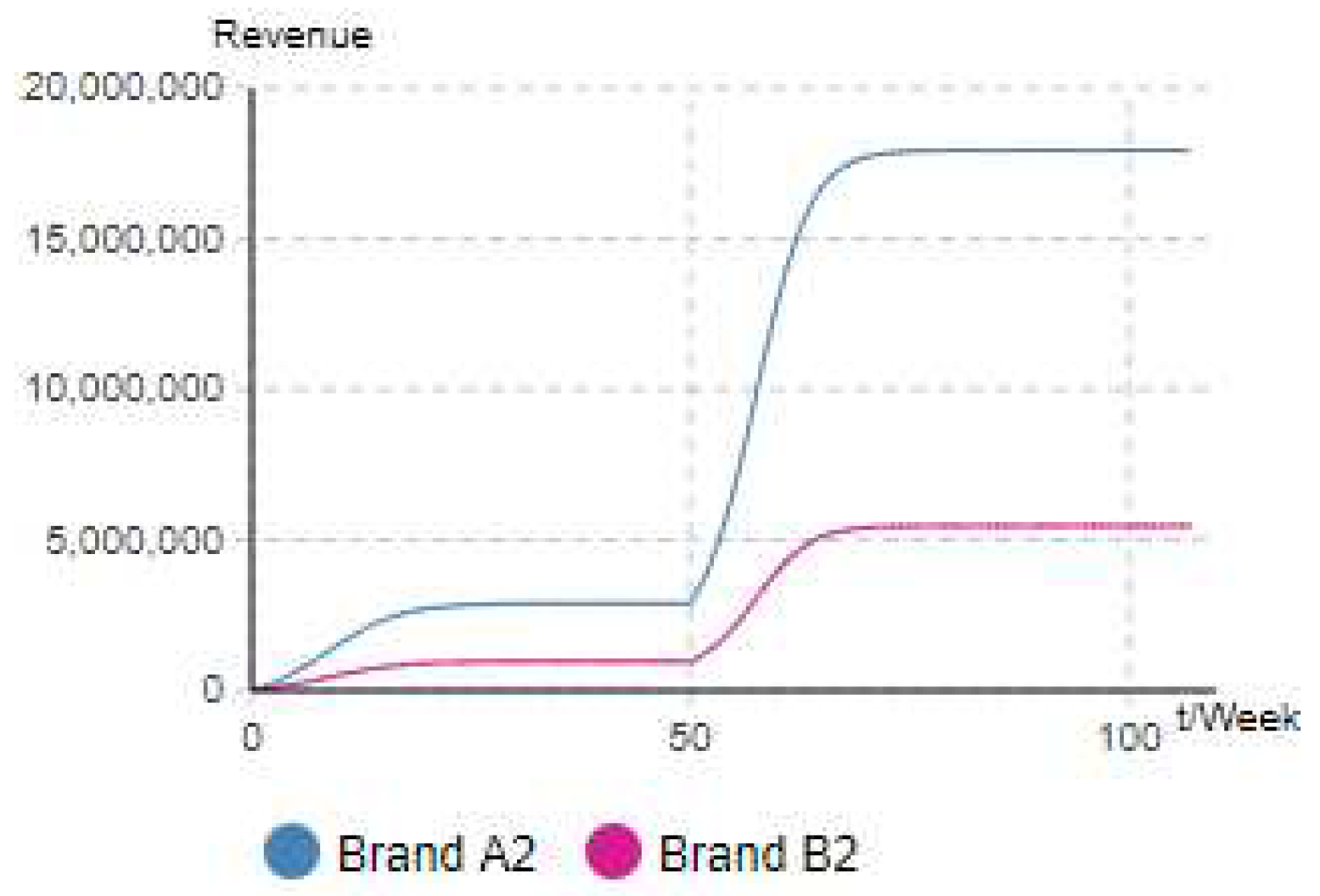

5. System dynamics simulation and experimentation

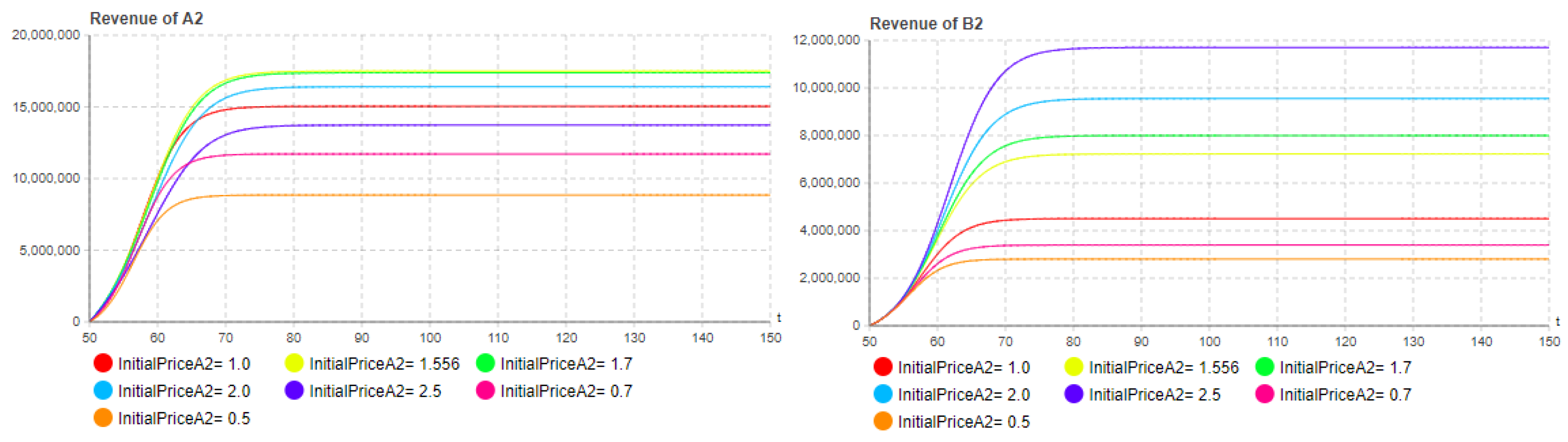

5.1. Optimal pricing decision

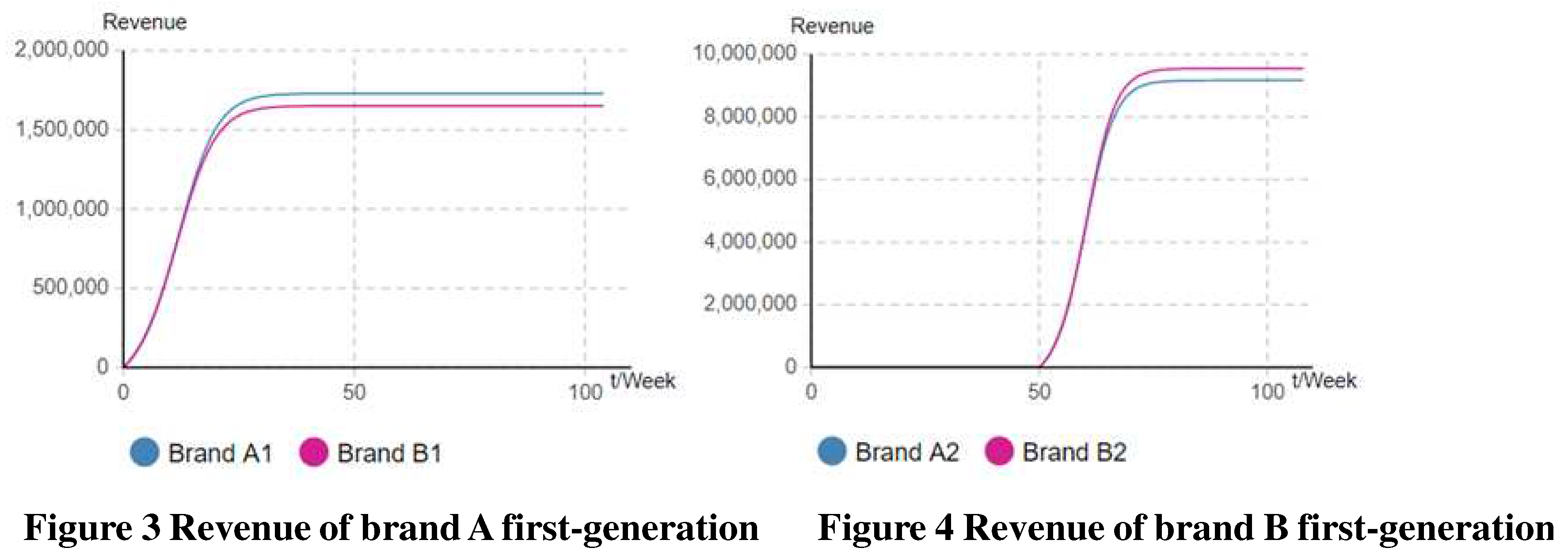

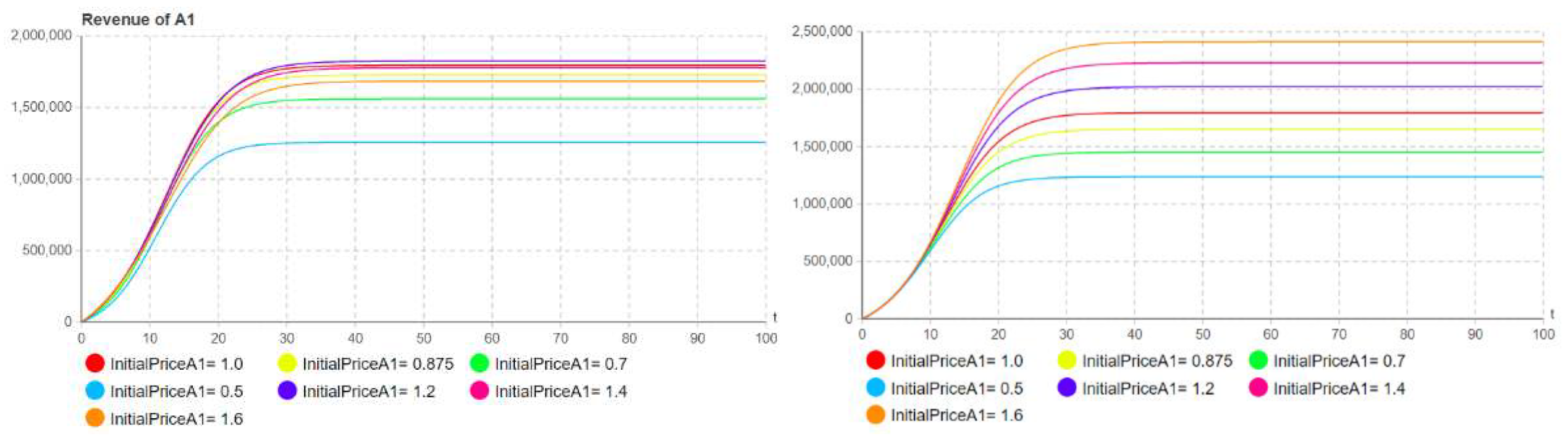

5.1.1. In the case of equal brand competitive strength

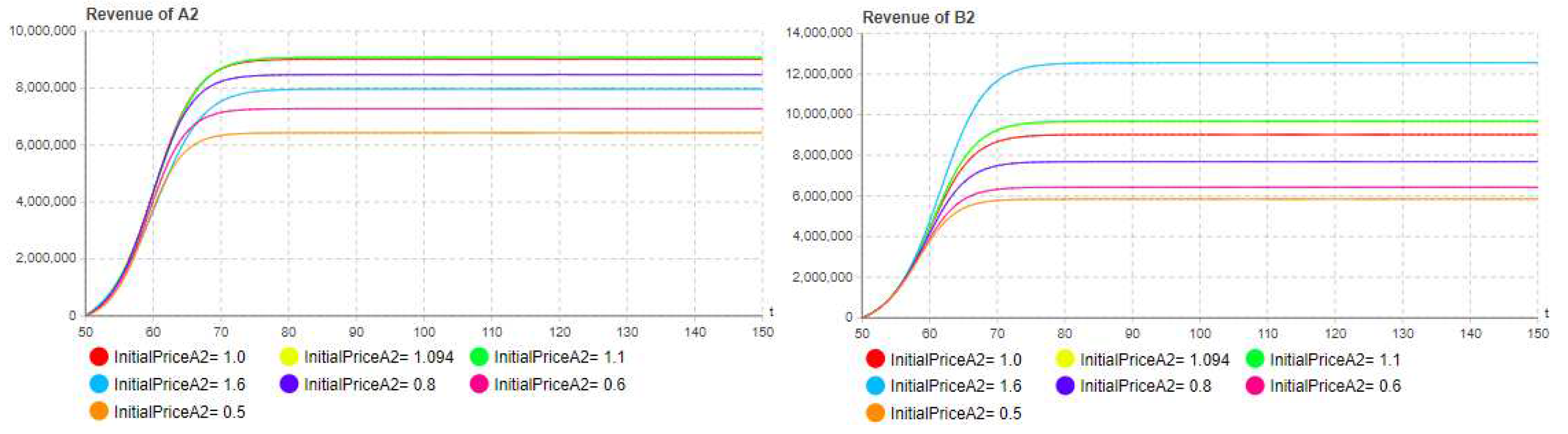

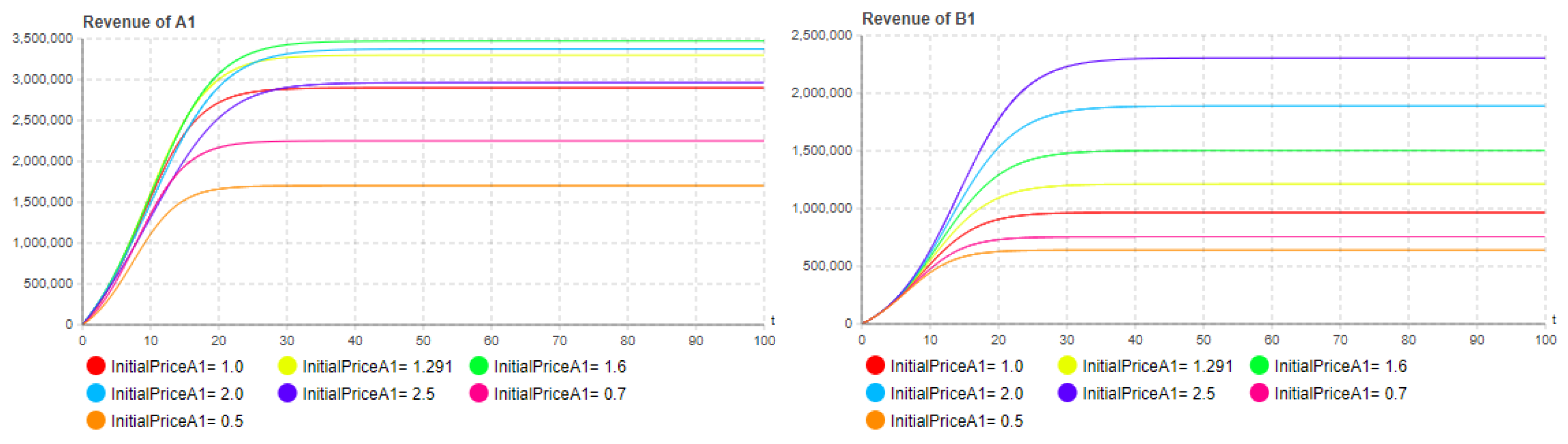

5.1.2. In the case of unequal brand competitive strength

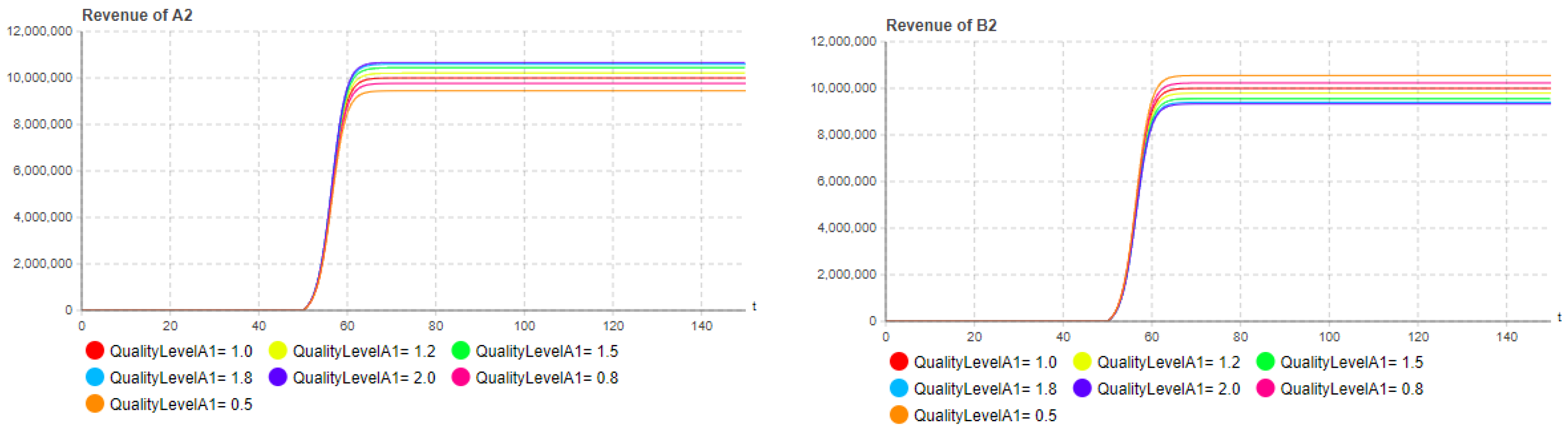

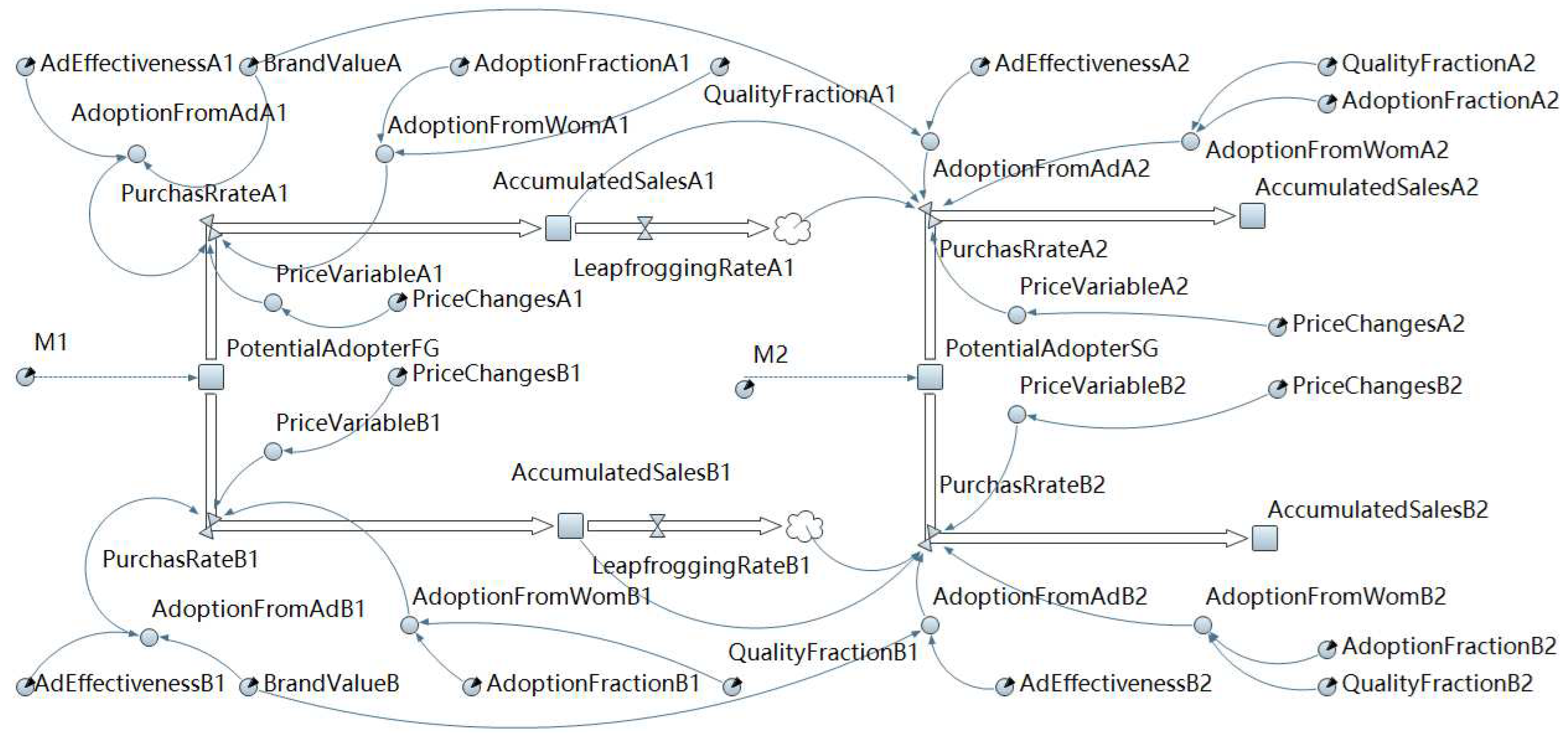

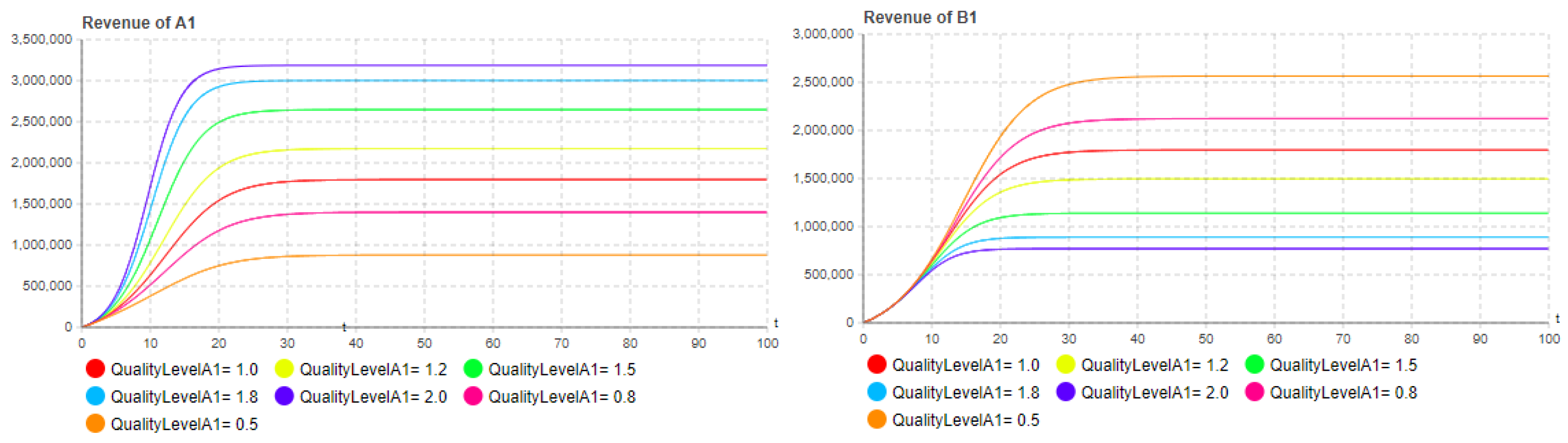

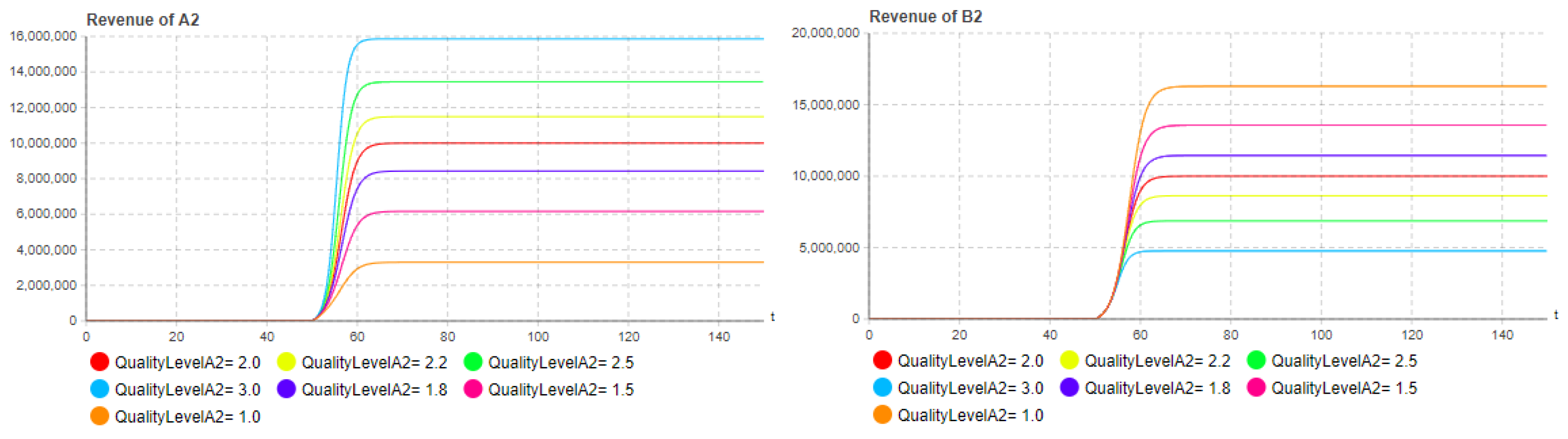

5.2. Influence of quality level

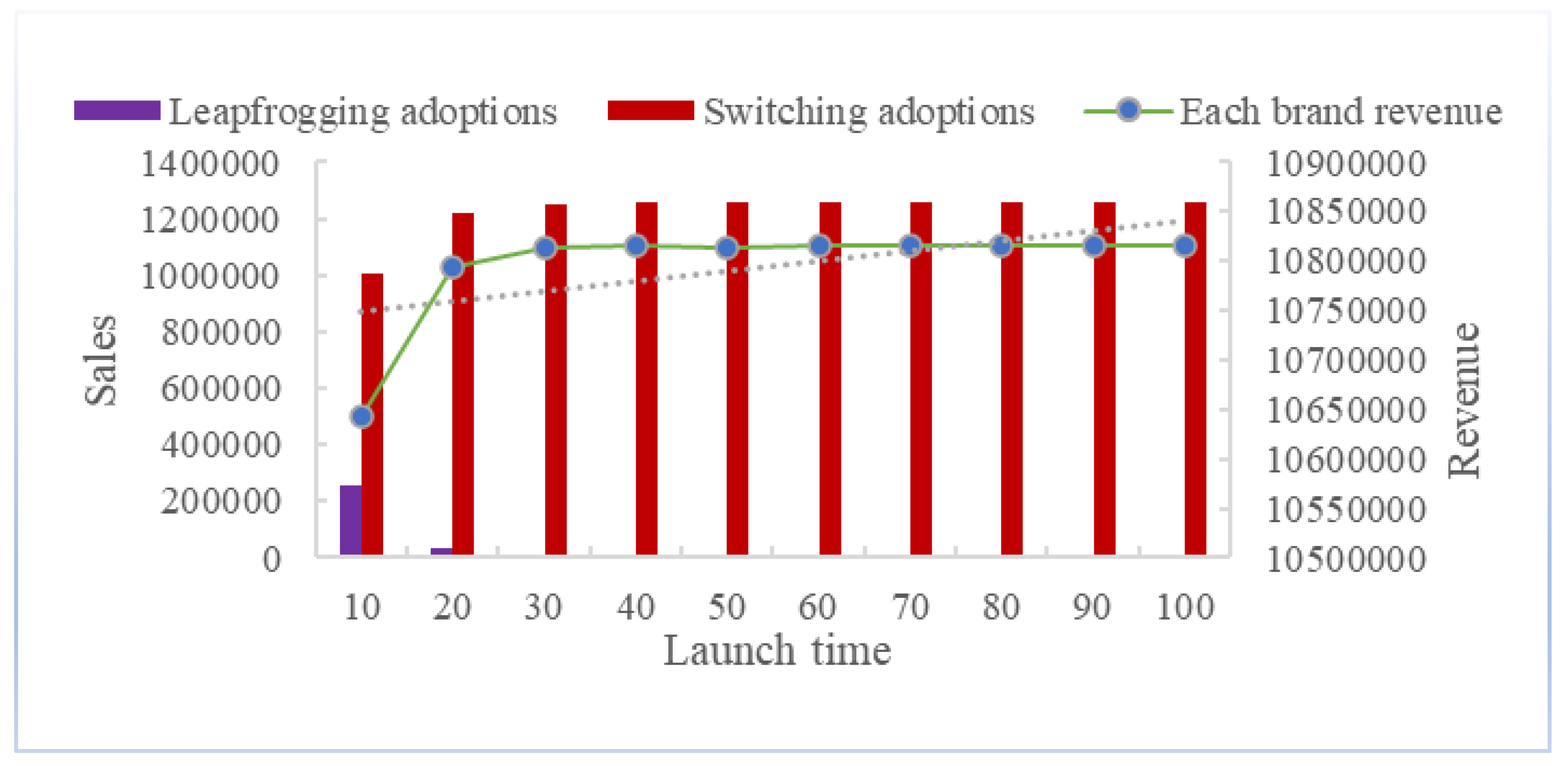

5.3. Launch time decision

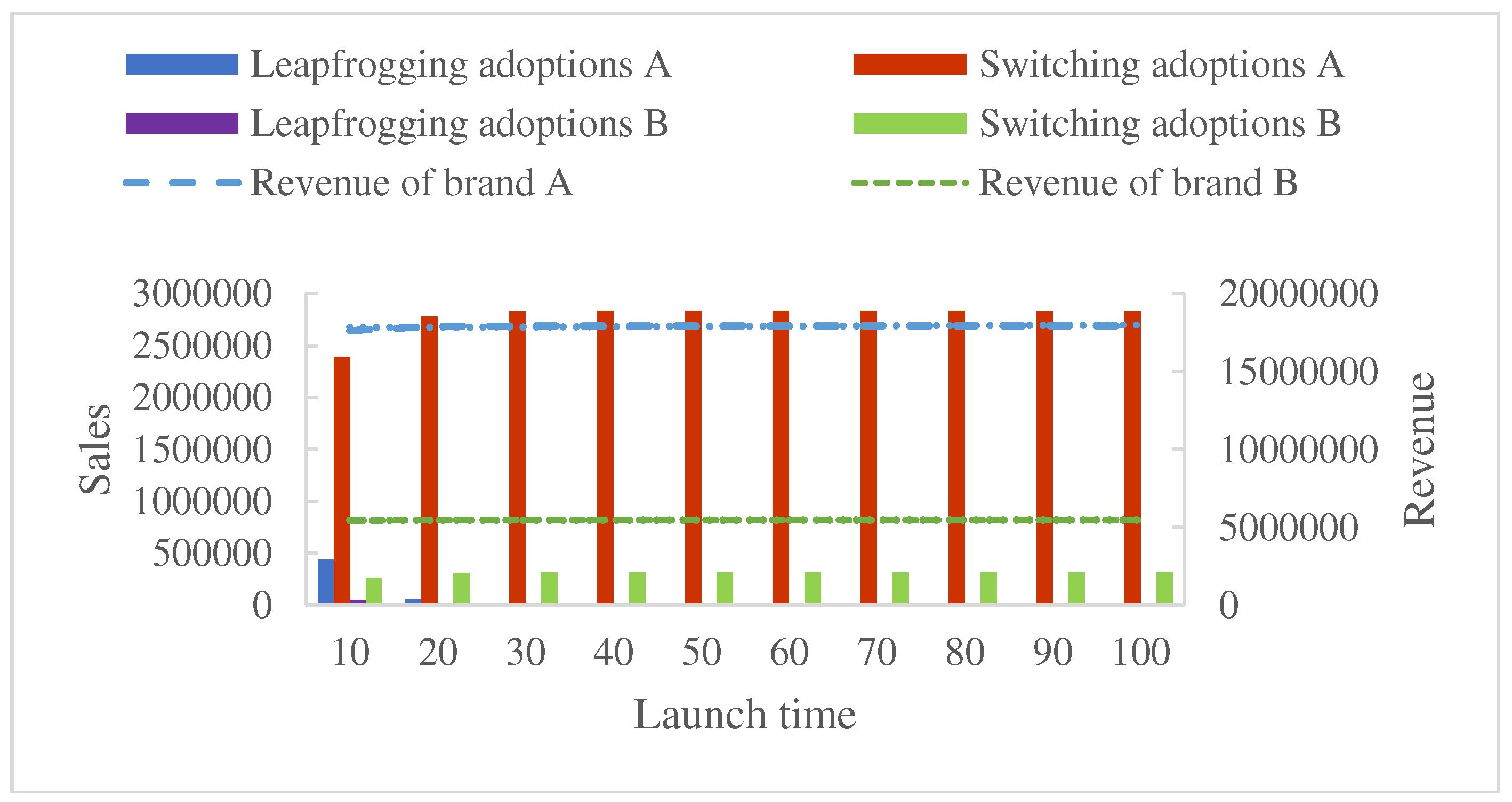

5.3.1. Launch time decision under equal brand value spillover scenario

5.3.1. Launch time decision under unequal brand value spillover scenario

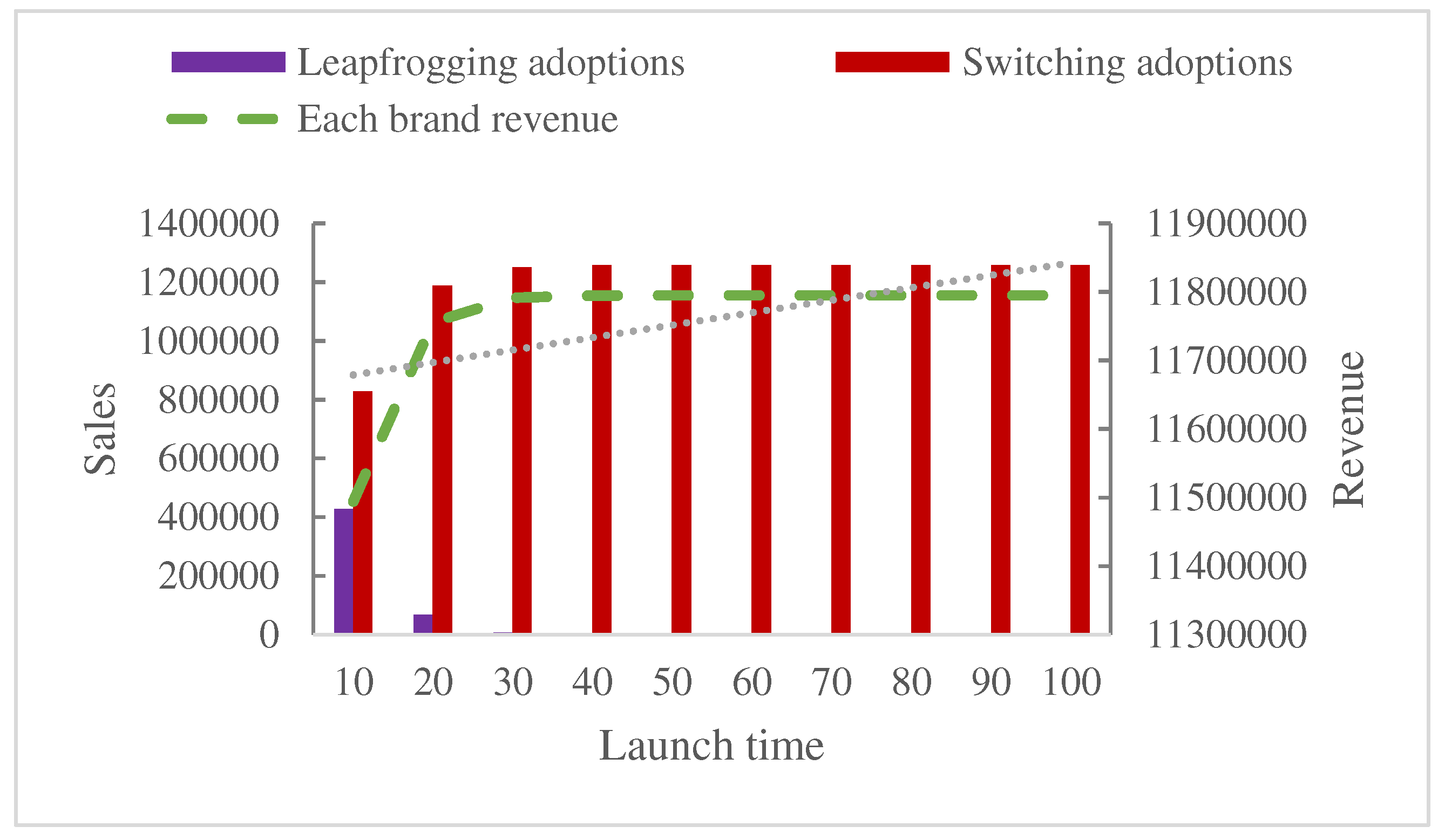

5.3.2. Launch time to market decision under quality upgrade scenario

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Leslie Olin Morgan, Ruskin M. Morgan, William L. Moore.Quality and Time-to-Market Trade-offs when There Are Multiple Product Generations. [J]. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 2001, 3, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Seifert R W. On the optimal frequency of multiple generation product introductions[J]. European Journal of Operational Research, 2015, 245, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3. Hapuwatte B M , Badurdeen F , Bagh A ,et al.Optimizing sustainability performance through component commonality for multi-generational products[J]. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 180, 105999. [CrossRef]

- John, A. Norton, Frank M. Bass.A Diffusion Theory Model of Adoption and Substitution for Successive Generations of High-Technology Products. [J]. Management Science, 1987, 33, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengrui Jiang, Dipak C. Jain.A Generalized Norton–Bass Model for Multigeneration Diffusion. [J]. Management Science, 2012, 58, 1887–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam T, Fiebig D G. Modelling the development of supply-restricted telecommunications markets[J]. Journal of Forecasting, 2001, 20, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonen J, Kamarainen J K, Puumalainen K, et al. Toward automatic forecasts for diffusion of innovations[J]. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2006, 73, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo Z, Chen J. Multigeneration Product Diffusion in the Presence of Strategic Consumers[J]. Information Systems Research, 2018, 29, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun D B, Park Y S. A Choice-Based Diffusion Model for Multiple Generations of Products[J]. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 1999, 61, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, M. Bass, (1969) A New Product Growth for Model Consumer Durables. Management Science 15, 215-227.

- 11. Lei Z, Yi-jun L, Wen-guo A. Research on Diffusion Mode of Chinese Mobile Communication Products[C]//2007 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering. IEEE, 2007: 2034-2039. 2.

- Laciana C E, Gual G, Kalmus D, et al. Diffusion of two brands in competition: Cross-brand effect[J]. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2014, 413, 104–115.

- Nikolopoulos K, Buxton S, Khammash M,et al. Forecasting branded and generic pharmaceuticals[J].International Journal of Forecasting, 2016, 32, 344–357.

- Krishnan TV,PB" Seethu,Seetharaman,et al. The multiple roles of interpersonal communication in new product growth[J].International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2012, 29, 292–305.

- Guseo R, Mortarino C. Within-brand and cross-brand word-of-mouth for sequential multi-innovation diffusions[J]. Ima Journal of Management Mathematics, 2014, 25, 287–311. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan T V, Kumar F M B. Impact of a Late Entrant on the Diffusion of a New Product/Service[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2000, 37, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan V, Sharma S, Buzzell R D. Assessing the impact of competitive entry on market expansion and incumbent sales[J]. Journal of marketing, 1993, 57, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim N, Chang D R, Shocker A D. Modeling intercategory and generational dynamics for a growing information technology industry[J]. Management Science, 2000, 46, 496–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libai B, Muller E, Peres R. The Role of Within-Brand and Cross-Brand Communications in Competitive Growth[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2009, 73, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohui Shi, Pattarin Chumnumpan.Modelling market dynamics of multi-brand and multi-generational products,European Journal of Operational Research,Volume 279, Issue 1,2019,Pages 199-210.

- Aggrawal D, Anand A, Bansal G, et al. Modelling product lines diffusion: a framework incorporating competitive brands for sustainable innovations[J]. Operations Management Research, 2022:1-13.

- Li H,Graves S C. Pricing Decisions During Inter-Generational Product Transition[J].Production & Operations Management, 2012, 21, 14–28.

- Li F, Du T C, Wei Y. Offensive pricing strategies for online platforms[J]. International Journal of Production Economics, 2019, 216, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgrath M E.Product strategy for high-technology companies[J].McGraw-Hill, 1995.

- Henderson,B,D,1973.The experience curve-reviewed II:history.Available at: https://www.bcg.com/search?q=+The+experience+curve+%E2%80%93+reviewed+II%3A+history+.

- Bock S , Puetz M .Implementing Value Engineering based on a multidimensional quality-oriented control calculus within a Target Costing and Target Pricing approach[J].International Journal of Production Economics, 2017, 183(PT.A):146-158.

- Li H, Webster S, Yu G. Product Design Under Multinomial Logit Choices: Optimization of Quality and Prices in an Evolving Product Line[J]. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 2020, 22, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Bala R, Carr S. Pricing Software Upgrades: The Role of Product Improvement and User Costs[J]. Production and Operations Management, 2009, 18, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim H J, Jee S J, Sohn S Y. Cost–benefit model for multi-generational high-technology products to compare sequential innovation strategy with quality strategy[J]. PloS one, 2021, 16, e0249124. [Google Scholar]

- Druehl C T, Schmidt G M, Souza G C. The optimal pace of product updates[J]. European Journal of Operational Research, 2009, 192, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng H, Jiang Z, Liu D. Quality, pricing, and release time: Optimal market entry strategy for new software-as-a-service vendors[J]. MIS Quarterly, 2017, 42, 333–353. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel I, Patel J, Vulcano G, et al. Optimizing Product Launches in the Presence of Strategic Consumers[J]. Management Science, 2016, 62, 1778–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 33. Negahban A , Smith J S . Optimal production-sales policies and entry time for successive generations of new products[J]. International Journal of Production Economics 2018, 199, 220–232. [CrossRef]

- Wenjing Shen, Izak Duenyas, Roman Kapuscinski. Optimal Pricing, Production, and Inventory for New Product Diffusion Under Supply Constraints[J]. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 2014, 16, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaram G, Robinson W T, Urban G L. Order of Market Entry: Established Empirical Generalizations, Emerging Empirical Generalizations, and Future Research[J]. Marketing Science, 1995, 14, 212–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützner T, Schnider C, Zollinger D, et al. Reducing time to market by innovative development and production strategies[J]. Chemical Engineering & Technology, 2016, 39, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar]

- McKie E C, Ferguson M E, Galbreth M R, et al. How do consumers choose between multiple product generations and conditions? An empirical study of iPad sales on eBay[J]. Production and Operations Management 2018, 27, 1574–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin S, Terwiesch C. Optimal product launch times in a duopoly: Balancing life-cycle revenues with product cost[J]. Operations Research, 2005, 53, 26–47.

- Ke T T, Shen Z J M, Li S. How inventory cost influences introduction timing of product line extensions[J]. Production and Operations Management, 2013, 22, 1214–1231.

- McKie E C, Ferguson M E, Galbreth M R, et al. How do consumers choose between multiple product generations and conditions? An empirical study of iPad sales on eBay[J]. Production and Operations Management, 2018, 27, 1574–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicay-Ergin N ,Chun-yuLin, Okudan G E ,et al. Analysis of dynamic pricing scenarios for multiple-generation product line [J]. Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering 2015, 1861-9576.

- Frank, M. Bass, Dipak C. Jain.Optimal Pricing Strategy for New Products. Management Science[J]. 1999, 45, 1650–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Cosguner K, Seetharaman S. Dynamic Pricing for New Products Using a Utility-Based Generalization of the Bass Diffusion Model l[J]. Management Science, 2022, 68, 1904–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speece, M. W, MacLachlan, et al. Forecasting fluid milk package type with a multigeneration new product diffusion model[J]. Engineering Management, IEEE Transactions on, 1992, 39, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, El, Ouardighi, et al. Advertising and Quality-Dependent Word-of-Mouth in a Contagion Sales Model[J]. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 2016, 170, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher P J, Hardie B G S, Putsis W P. Marketing-Mix Variables and the Diffusion of Successive Generations of a Technological Innovation[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2001, 38, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram M, Balachander S. Increasing Quality Sequence: When Is It an Optimal Product Introduction Strategy? [J]. Management Science, 2015, 61, 2487–2494.

- 48. Peng S , Li B , Hou P . Optimal Upgrading Strategy for the Quality, Release Time, and Pricing for Software Vendor[J]. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2021, PP(99):1-1.

- Zhang J, Dong L, Ji T. The Diffusion of Competitive Platform-Based Products with Network Effects[J]. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 8845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | kAi | 1 | |

| M2 | kA2 | 1 | |

| αA | 1 | kB1 | 1 |

| αB | 1 | kB2 | 1 |

| qA1 | 0.337 | pA1(0) | 1 |

| qA2 | 0.477 | pA2(0) | 1 |

| qB1 | 0.337 | pB1(0) | 1 |

| qB2 | 0.477 | pB2(0) | 1 |

| PA1 | 0.00943 | R | -0.05 |

| PA2 | 0.00943 | 50 | |

| pB1 | 0.00943 | βA | 0.5 |

| pB2 | 0.00943 | βB | 0.5 |

| r | 0.02 | T | 150 weeks |

| scenario | Brand value αA=1,αB=1 |

Brand value αA=3,αB=1 |

|---|---|---|

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=2, kB2=2 |

pA1(0)=0.849,pA2(τ2)=0.994 πA=11827922.349 |

pA1(0)=1.278,pA2(τ2)=1.398 πA=21015325.598 (1) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=2 |

pA1(0)=1.345,pA2(τ2)=1.336 πA=21963950.961 |

pA1(0)=1.762,pA2(τ2)=1.742 πA=31744272.157 (2) |

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=2 |

pA1(0)=0.676,pA2(τ2)=1.34 πA=19334506.412 |

pA1(0)=1.173,pA2(τ2)=1.743 πA=29099025.877 (3) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=3 |

pA1(0)=1.438,pA2(τ2)=0.954 πA=14736147.193 |

pA1(0)=1.857,pA2(τ2)=1.321 πA=23729928.91 (4) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=2, kB2=1 |

pA1(0)=1.427,pA2(τ2)=1.675 πA=24773330.916 |

pA1(0)=1.741,pA2(τ2)=2.075 πA=35111523.865 (5) |

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=1, kB2=1 |

pA1(0)=0.875,pA2(τ2)=1.094 πA=10894474.196 |

pA1(0)=1.291,pA2(τ2)=1.556 πA=20536744.303 (6) |

| scenario | Brand value αA=1,αB=1 |

Brand value αA=3,αB=1 |

|---|---|---|

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=2, kB2=2 |

pB1(0)=0.849,pB2(τ2)=0.994 πB=11827922.349 |

pB1(0)=0.819,pB2(τ2)=0.833 πB=5964821.122 (7) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=2 |

pB1(0)=0.715,pB2(τ2)=0.761 πB=5460440.417 |

pB1(0)=0.999,pB2(τ2)=0.78 πB=2805444.926 (8) |

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=2 |

pB1(0)=0.99,pB2(τ2)=0.762 πB=6789403.062 |

pB1(0)=0.949,pB2(τ2)=0.78 πB=3402421.956 (9) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=3, kB2=3 |

pB1(0)=0.454,pB2(τ2)=0.952 πB=10685858.775 |

pB1(0)=0.813,pB2(τ2)=0.778 πB=5567137.124 (10) |

|

kA1=2, kB1=1 kA2=2, kB2=1 |

pB1(0)=0.817,pB2(τ2)=0.908 πB=3873196.966 |

pB1(0)=1.043,pB2(τ2)=1.052 πB=2205744.207 (11) |

|

kA1=1, kB1=1 kA2=1, kB2=1 |

pB1(0)=0.875,pB2(τ2)=1.094 πB=10894474.196 |

pB1(0)=0.847,pB2(τ2)=0.975 πB=5486472.016 (12) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).