1. Introduction

The experience of COVID-19 pandemic has turned the spotlight on the importance of public health measures and disease prevention. The urgent need to control the spread of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has accelerated the development of immunization strategies and, on 11 December 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [

1]. In the same period, the seasonal influenza vaccination campaign, known to be the most effective way to protect from infection and to reduce the flu-related morbidity and mortality [

2], was taking place in many countries worldwide. Despite the established importance of both of these prevention measures, influenza vaccination uptake has remained low in most nations (and far from the World Health Organization's target of 75%) [

3], while misperceptions regarding the efficacy, the safety and the reliability of COVID-19 vaccine have grown.

Italy was the first European country hit by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and started the COVID-19 vaccination campaign on 27 December 2020 [

4]. After a first discretely enthusiastic acceptance of the immunization, an abrupt halt was observed with a decreasing trend in the daily number of vaccine recipients estimated of 39.765 [

5]. On 30 June 2021 only 57.5% of the total population had received at last one dose of COVID-19 vaccine [

5]. For the purpose of keeping a level of immunization coverage capable of contrasting the virus circulation, on 23 July 2021 the Italian Government adopted the European Digital Pass strategy, also called Green Pass. It consisted in a certificate that had to be displayed to enable access to all public places - work places included - and to travel. The certificate was delivered by the Ministry of Health via app to those with recent infection (180 days validity), immunization (1 year validity) or recent negative COVID-test (2-3 days validity) [

6]. This strategy - also adopted by other countries as France, Israel and Denmark - was pursued to avoid the introduction of mandatory SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, based upon the principle that an incentive-based model would have been more tolerated [

7]. During the first weeks after its entry into effect, Green Pass was heavily emphasized via the news with an immediate rebound on social media; bookings for vaccination skyrocketed and the immunization coverage increased (on the first week of August 2021 was reached the number of 71,071,465 vaccine doses administered the since the beginning of the campaign) [

5]. Despite the early success of this measure, many people kept their anti-vaccination beliefs and, gradually, concerns regarding the compulsory nature of Green Pass started to rise, threatening the efficacity of this strategy [

8]. In April 2022 the need of the certificate for access to public places was dismissed and since December 2022 it has not been required to enter hospitals as a visitor [

9]. To date, 49,526,642 people have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine and 48,725,293 have completed the vaccination cycle (respectively 91.73 % and 90.4 % of the population over [

10].

In COVID-19 pandemic time, the seasonal influenza vaccination (SIV) campaign took place in Italy during winters 2020-2021 and 2021-2022, starting in mid October and ending in the month of February. Immunization was offered free of charge to people older than 60 years, to healthcare workers and to the most fragile part of the population [

11]. The first campaign made soar the progressive annual increase in vaccinal coverage ongoing since 2013, with 23.7% of the population having received the flu shot at the end of the winter (+ 6.9% if compared with the previous year). The subsequent SIV campaign 2021-2022 settled the end of this upward trend with a 3.2% decline in the vaccination coverage rate among general population and an even greater collapse when considering the elderly (from 65.3% in 2020-2021 to 58.1% in 2021-2022) [

12].

On these premises, the aim of this work was to explore deeply the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy in the complex background in which COVID-19 and influenza vaccination campaigns have concurrently taken place between 2021 and 2022, departing from the hypothesis that large-scale prevention strategies can drive people’s attitude only if they climb down into the context - in which social media information, mandatory political choices as well as personal opinions and emotions intertwine. We longitudinally analyzes the vaccinal tendences towards both COVID-19 and influenza vaccination in a cohort of patients that first experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection in the area of Academic Hospital of Udine (Italy), investigating the reasons behind hesitancy or acceptance. Expanding knowledge relating to these attitudes may inform the future public health strategies in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This investigation used a two times repeated cross-sectional exploratory design to assess vaccinal tendences towards both COVID-19 and influenza vaccination in a cohort of adult patients having in common a medical history of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2020, during the first pandemic wave. The study was carried out between 2020 and 2022 and it was designed and conducted by the Infection Diseases Unit at the Academic Hospital of Udine (Italy), a tertiary-care teaching hospital (1000 beds) that was also a referral regional centre for COVID-19 attending a population of approximately 530,000 inhabitants.

2.2. Participants

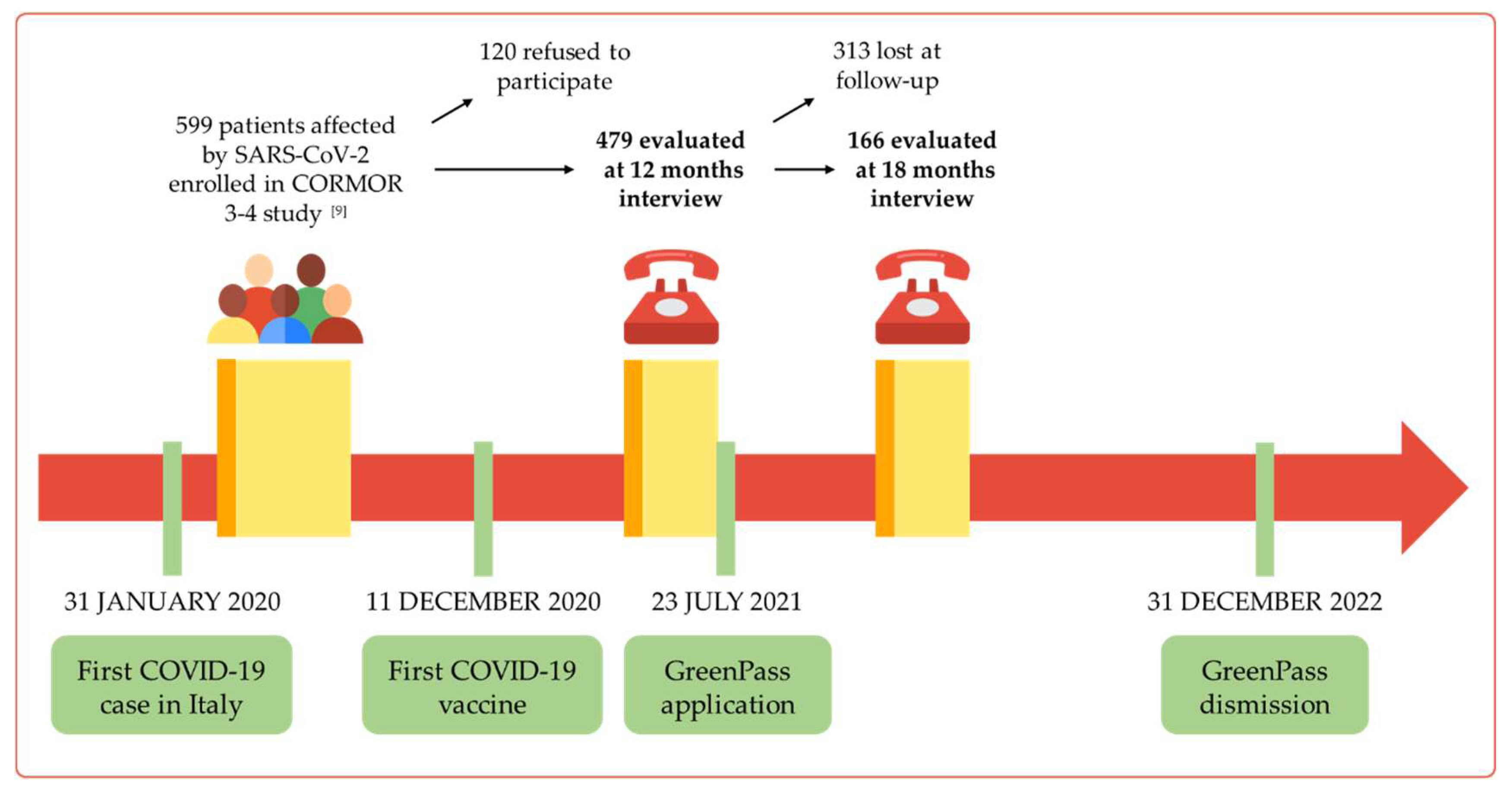

A cohort of adult (older than 18 years) in- and out- patients who had received a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection between March 2020 and April 2020, during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave, and who had taken part in the CORMOR 3-4 study [

13], was firstly assessed in 2021 for vaccinal hesitancy at 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection [

14]. Then the survey was conducted longitudinally, exploring the vaccination hesitancy or willingness at 12 months and at 18 months. Eligible patients were those (a) recruited during their first access at the Infectious Disease Department of Udine in March 2020; (b) confirmed as cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection, thus patients with a positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for SARS-CoV-2 in a respiratory tract specimen; (c) willing to take part in telephonic interviews conducted at 12 and 18 months following the infection (

Figure 1).

2.3. Primary Outcome and Associate Variables

The primary aim of the study was to assess patients’ attitude towards COVID-19 and flu vaccines at 12- and 18-months following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Attitude was considered in terms of expressed hesitancy or willingness to adhere to the vaccination campaign. The secondary aim was to identify factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and willingness.

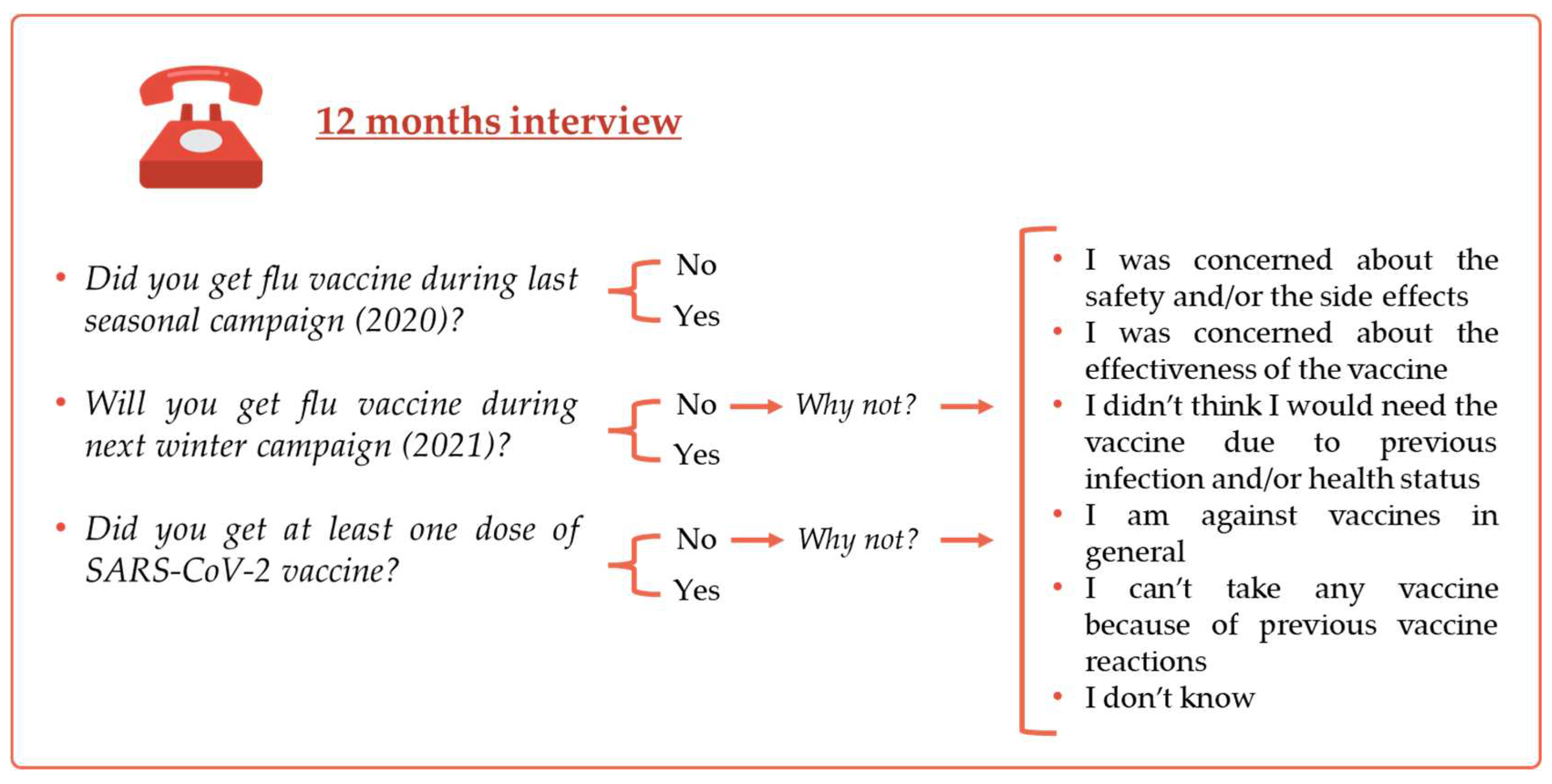

Vaccine attitude was first assessed at 12 months with the following questions “Did you get flu a vaccine during last seasonal campaign?”, “Will you get a flu vaccine next winter?” and “Did you get at least one dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine?”. Possible answers were yes/no. In case of negative answer, participants were asked to explain their vaccine hesitancy towards the two vaccines (

Figure 2).

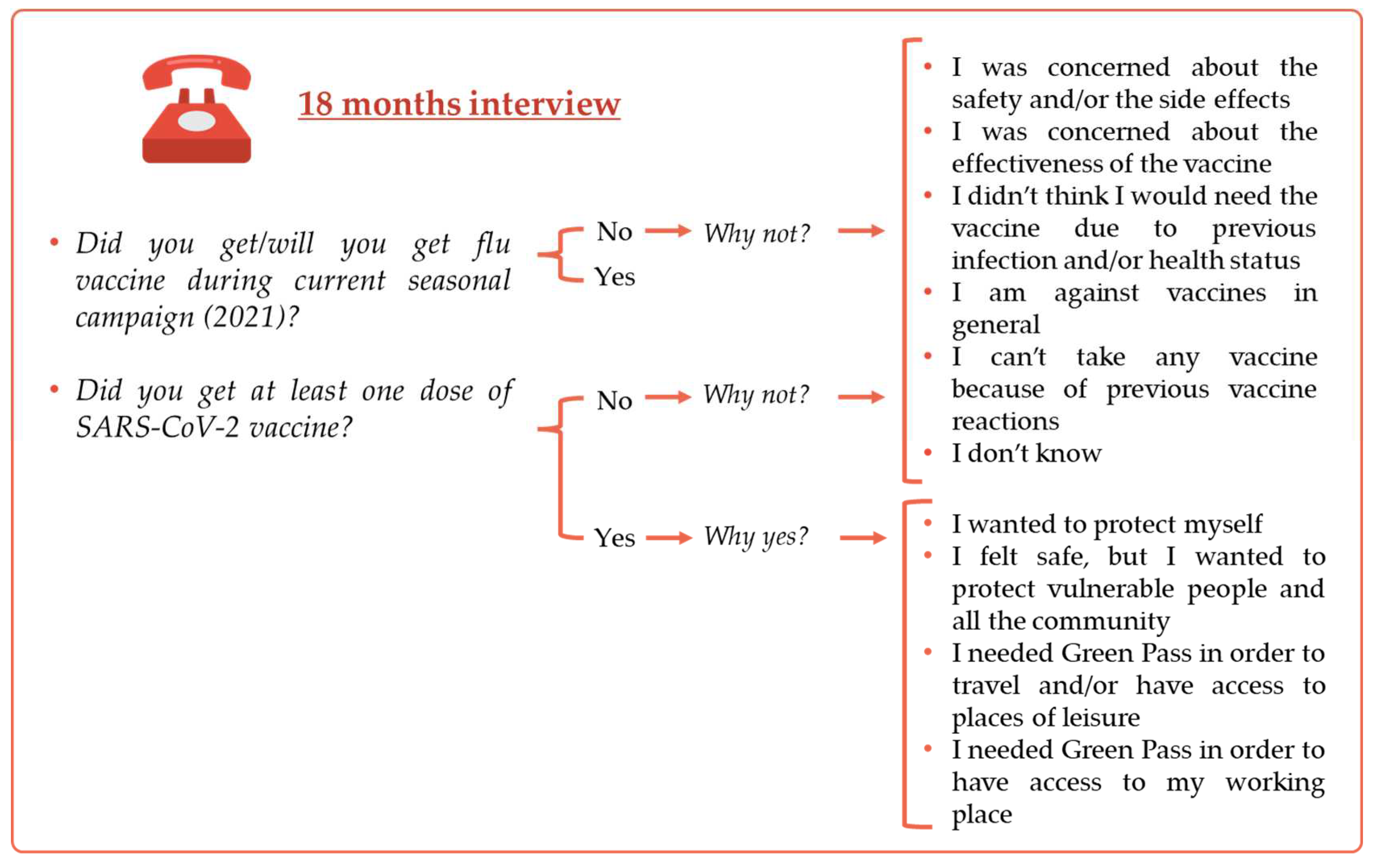

A second interview was taken at 18 months when participants were asked about their attitude towards flu vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and were again asked to explain their vaccine hesitancy towards the two vaccines. Moreover, at 18 months participants were also asked to motivate their decision in case of positive attitude towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (

Figure 3).

2.4. Procedure and Data Collection

All eligible patients were contacted by phone by trained nurses in two different occasions, approximately in May 2021 and in December 2021. The first interview took place 12 months following participants’ SARS-CoV-2 first infection, at the end of 2020-2021 flu vaccination campaign and before Green Pass introduction. The second interview took place 18 months following participants’ SARS-CoV-2 first infection, during the 2021-2022 flu vaccination campaign and during the period when Green pass was widely in use. The nurses involved in the interview process were all advanced educated at the Master or at the PhD level; they were all supervised in the first five interviews by an expert researcher to ensure homogeneity and quality in the data collection process. In the pilot phase, conducted during the first data collection, the understability was assessed among 10 patients and no changes were requested. The interview was also considered feasible given that lasted about 15 minutes.

The participants’ responses were recorded using a standardized interview guide (

Figure 2,

Figure 3). They were left free to answer with their own words and to justify their SARS-CoV-2 and flu vaccine attitude/hesitancy; in the second interview the categorization of reasons emerged in the first were used to collect the answer by transforming the open-ended in a close-ended question (

Figure 3) [

14]. Clinical data collected during the follow-up were extracted from the General Hospital databases, using a standardized protocol.

2.5. Ethical Issues

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Udine and Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale (CEUR-2020-OS-219/CEUR-2020-OS-205) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects before being contacted for the interview.

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Sample Size

Vaccination coverage in Friuli Venezia Giulia during the latest seasonal influenza vaccination campaign has been 20% [

12]. A sample size of 479 patients allows to produce a two-sided 95% confidence interval of this proportion with a 3.7% precision.

Descriptive statistics included frequency analyses (percentages) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation; SD), median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables. In the first data interview, the open-ended answers regarding the vaccine attitudes/hesitation, were categorized by the research team. Specifically, there were involved three investigators as members of the clinical infectious disease unit and the nurses team: they independently analyzed each answer and categorized though a content analysis process [

15] . At the end of the process, they compared the findings by discussing disagreements (

Figure 3). Thus, the categorization emerged in the first were used in the second data collection as the basis for the interview in order to compare the data and explore the changes, if any.

Data were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro –Wilk test. Patients were stratified by age (intervals 18–40, 40–60, >60 years old), nationality, occupation, smoking habits, presence of comorbidities, symptomatic COVID-19, hospital admission and presence of symptoms at 12 months. To explore vaccine hesitancy, the Chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher test were used to compare categorical variables among groups, as appropriate. Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare continuous variables among groups, depending on whether data were normally or non-normally distributed. Furthermore, a univariable logistic regression was performed to explore variables associated to vaccine willingness, estimating the odds ratios (OR; 95% CI).

Analyses were performed using STATA 17. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Population

Out of the 599 patients enrolled in the CORMOR 3-4 study [

9], 479 patients answered the interview at 12 months (participation rate of 79.9%) and 166 of them completed the survey at 18 months (34.7%). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the population are summarized in

Table 1 and in

Table 2.

In brief, 252/479 (52.6%) were female and the mean age was 53 (SD = 15). People working in contact with public accounted for 42.0% (186/443) of the respondents and 19.1% (81/443) were retired. About one half of the patients (249/479, 52.0%) reported at least one chronic medical condition and 47.2% (226/479) were still reporting presence of SARS-Co-V-2 related symptoms at 12 months after the primary illness.

3.2. Attitude towards Influenza Vaccine at the First Interview (12 Months Interview)

Overall, almost half of the respondents (210/479, 43.8%) reported having received the seasonal influenza immunization during winter 2020-2021 and, at the time of the first interview, nearly the same percentage (224/479, 46.8%) was motivated to undertake immunization again (

Table 3).

As shown in

Table 4, a positive attitude towards vaccination was significantly associated with older age (57.6% > 60 years vs. 10.5% 18–40 years; p-value < 0.001), comorbidities (65.1% favourable vs. 42.6% hesitant; p-value < 0.001) and Body Max Index (BMI) (median 25.6 in favourable vs. 24.7 in hesitant, p-value 0.011); moreover, being retired was found to be a predictor of willingness to get influenza immunization (31.5% favourable vs. 7.7% hesitant; p-value < 0.001). On the other side, people whose job did not involve being in contact with public were more likely to refuse seasonal vaccination (38.1% favorable vs. 45.1% hesitant; p-value < 0.001). Gender and smoking habits did not show an association with influenza vaccine acceptance.

In relation to the clinical course of COVID-19,

Table 5 reports that only admission to ICU during the acute infection emerged as a factor promoting vaccine acceptance (p-value < 0.001); neither the presence of a symptomatic acute infection, nor the development of post-COVID-19 syndrome shown a significant association with a positive attitude towards vaccination.

Table 6 shows the reasons of hesitancy reported by those who declared to be unwilling to vaccinate against influenza in the future. The main motivation reported was the feeling of being protected - even without immunization - because of self-perceived good health status (135/200, 67.5%); only a small percentage expressed concern about the safety or the effectiveness of the vaccine (respectively 6.5% and 4.5%).

3.3. Attitude towards Influenza Vaccine at the Second Interview (18 Months Interview)

At 18 months interview, a decrease in influenza vaccination acceptance was registered: only 18.1% (30/166) out of the total reported to be favourable, while the majority declared to be unwilling to be immunized.

Similarly to the 12 months survey, a strong statistical association was found between vaccine acceptance and older age, presence of comorbidities or being retired (p-value < 0.05 in all cases). Among people working in contact with public, a significant proportion of vaccination refusal was registered (30% likely vs. 46.9% unlikely; p-value < 0.001).

No association emerged between influenza vaccine hesitancy and the clinical characteristics of acute COVID-19 infection, except for ICU admission (

Table 5).

As in the previous interview, the main motivation for refusal was the feeling of being protected without the need of a vaccine (72/129, 55.8%) but, at 18 months survey, a higher percentage (30/129, 23.3%) resulted sceptical about the effectiveness of the influenza vaccination (

Table 6).

3.4. Attitude towards SARS-CoV2 Vaccine at the First Interview (12 Months Interview)

At the interview performed 12 months after acute COVID-19 illness, only 27.6% (132/479) reported to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV2, while the great majority of the population was hesitant.

From the analysis of the reasons for refusal (

Table 6), it emerged that 56% of the participants unwilling to be vaccinated were afraid that the vaccine could have dangerous side effects; another heartfelt reason was the idea that the vaccine was unnecessary, due to previous infection, health status or age (20.0%).

3.5. Attitude towards SARS-CoV2 Vaccine at the Second Interview (18 Months Interview)

The great majority of the interviewed (121/166, 72.9%) reported receipt of COVID-19 immunization at 18 months survey. Among the minority of reluctant, the main motivation for refusal was the feeling of being protected without the need of a vaccine (22/45, 48.9%).

Considering the participants with a positive attitude towards vaccination, the main reason for vaccine acceptance was the declared will to protect themselves and the community (90/121, 74.5%), while a minority (27/121, 22.3%) reported as a motivation the need to obtain Green Pass in order to have access to working and leisure places.

Table 7 shows the general characteristics of the population according to the rationale that stimulated them to vaccinate; no significative associations were found between participants’ demography, habits, comorbidities or severity of the primary SARS-CoV-2 illness and the decision to be immunized because of the need to obtain Green Pass rather than the will to protect themselves and the community. The only characteristic that was proved to influence the reason behind the vaccine acceptance was to have a job, as all the participants who found in the need of Green Pass the leading reason for vaccination were workers (100.0%; 52.0% working in contact with public, 44.0% doing works not in contact with public and 4.0% doing unspecified kind of works; p-value 0.007).

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this research was to investigate the evolution over time of vaccinal attitudes towards influenza and SARS-CoV-2 - respectively the main epidemic and pandemic diseases co-existing in current times – in people who had experienced COVID-19 infection during the first and most impactful pandemic wave.

Some significant results emerged from our investigation: (i) self-perception of being at risk was directly correlated with the receipt of influenza vaccination, while the main reason given by participants to explain influenza vaccine refusal was the feeling of being protected without the need of a vaccine; (ii) 2020/2021 seasonal influenza vaccination campaign reported high levels of compliance, while a substantial fall in influenza vaccine acceptance was seen during the following winter, probably as a consequence of the underestimation of the issue (reduced circulation of the flu virus and tendency to overshadowing diseases others than COVID-19) and the spreading of mistrust in vaccines; (iii) a great increase in the number of people vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 occurred after the introduction of Green Pass, even if the great majority of the interviewed declared other reasons inspiring their choice and no significative correlations were founded between the characteristics of the population and the reason behind their vaccine acceptance.

4.1. Self Perception as a Potential Driver of Tendences towards Influenza Vaccination

As defined by Osterholm et al., vaccine hesitancy is a dynamic and complex issue which declines in a context-specific way depending on time, place and type of vaccine considered [

16].

With respect to influenza vaccination, in our cohort we observed that people in favour of flu vaccination were mostly the elderly and chronically ill patients (68.4% aged 60 or older vs. 22.9% between 18 and 40 years and 54.6% with underlying diseases vs. 32.7% without), in line with data provided by the Italian Ministry of Health regarding the 2020/2021 SIV [

11] and with findings emerged from surveys conducted in Italy in the same period [

17,

18]. A positive association between the most fragile part of the population and flu vaccination uptake was expected, since immunization is routinary offered to these categories because of its established role in preventing morbidity and mortality [

18,

19]. In addition, we observed an increased level of vaccine acceptance among subjects with BMI greater than 25. This is consistent with the evidence coming from a survey in obese population conducted by Harris et al. [

20] and might be explained by the self-perception of being vulnerable and, consequently, at higher risk for influenza complications [

21]. The possible role of fear in promoting preventive attitudes was investigated by Cori et al., focusing on COVID-19 concern as a driver of influenza vaccine uptake [

22]. The results coming from our research support this evidence, since we found a positive association between admission to ICU during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and influenza immunization acceptance (p-value < 0.001). Moreover, the rate of flu vaccine coverage observed in our cohort is outstandingly higher if compared to official Italian data referring to the successful 2020-2021 influenza vaccination campaign (48.3% vs. 23.7%) [

12]. We suggest, as a possible explanation, the baseline characteristic of our sample, since all the participants shared a common medical history of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first pandemical wave, known as the most severe and impactful.

Whether the consciousness of being at risk is well recognized as a major incentive to opt for vaccination, also the reverse association between low perceived risk and vaccine hesitancy is well established [

23,

24,

25]. Evidence in support of this can be found in our survey as well, since the main motivation given by our respondents to justify their vaccination refusal was the feeling of being protected even without immunization, due to good health status self-perception.

4.2. Exploring the Reasons Behind the Fall in SIV Confidence during Winter 2021-2022

The data collected during our second interview (performed during 2021/2022 SIV campaign) registered a radical trend reversal with respect to the attitude towards seasonal influenza immunization if compared with the data coming from the interviews performed in the same sample at 6 [

14] and 12 months after SARS-CoV-2 acute illness. According to our estimates, the percentage of people prone to be vaccinated in December 2021 was only 18.1% and was similar to the rate of 20.5% reported in the whole Italian population in the same period [

12].

To the best of our knowledge, at present, there is no literature exploring the deep reasons for this fall in SIV confidence among Italians. The participants to our survey explained their hesitancy using quite the same motivations given six months before, however a great increase in concerns regarding side effects and vaccine ineffectiveness was observed. This scepticism is in line with similar studies conducted at the same time [

21,

26,

27] and could be related to conspiracy theories and lack of trust in the healthcare system that spread with unprecedent speed during the COVID-19 pandemic [

24,

28]. In parallel, the polarization of the vaccination campaigns towards SARS-CoV-2 and the media monopolization by COVID-19 advocacy contributed to overshadowing the importance of other infectious diseases [

29]. The underestimation of influenza might have been also driven by the declined circulation of the virus itself, due to the implementation of behavioural protective measures (face masks, physical distancing and movement restrictions) adopted to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 [

29]. Finally, in December 2021, the Green Pass had already been in force for several months, this probably contributing to the growth of hatred for vaccination campaigns among the population [

30]. As suggested by Mills and Rüttenauer, COVID-19 certification is a part of multiple policy levers that could be adopted to counter vaccine hesitancy, but has to be used with caution according to the context, because of the risk of ending in increased complacency [

31].

4.3. Exploring the Assumed Incentive Role of the Green Pass towards SARS-CoV2 Vaccination

With the present study we highlighted a significant increase in SARS-CoV2 vaccination confidence in the interview performed in December 2021, as compared to the one performed before the introduction of Green Pass, and same results have been obtained in surveys conducted in other European countries in the same period [

31]. Surprisingly, it emerged from our work that the leading motivation declared by respondents in order to explain their immunisation confidence was the will to protect themselves and the community, rather than the need to obtain the certification. These findings are in contrast with data coming from analogues Italian studies [

32] and could be explained by the fact that our interviews were performed by healthcare workers, this having potentially driven the answers through altruism or health anxiety feelings rather than to the fear of social limitation. In our survey no significant association was found between the reason behind the vaccine acceptance and the characteristics of COVID-19 previous infection or the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. The only factor significantly linked to the will of Green Pass as an incentive for vaccination was to have a job, as it is intuitively logical. The above can be interpreted as a further demonstration that the direct association observed between Green Pass and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake should be carefully interpreted considering the context and the pandemic trajectory.

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

In displaying our results, it is certainly necessary to consider the different limitations and discuss the strengths of the present investigation.

The first limitation of this work resides in its non-anonymous nature and in the fact that the interviews were performed by healthcare workers; this could have introduced a bias in the answers given by the participants. Secondly, just over one-third of respondents to the first interview were available and allowed to take part in the second one, thus determining a suboptimal response rate. The failure in completing the survey may have been due to the unavailability of the people during phone calls or to the loss of interest in the project once COVID-19 fear was gradually disappearing. Although we had a justifiable sample size to provide enough statistical power, a larger sampling would have definitely strengthened our observation, especially at 18 months interview.

Another weakness in the design of our study consists in the fact that the educational level and the socioeconomic status – defined in other studies as major determinants of vaccine uptake during the pandemic period [

33], were not assessed. Moreover, the investigation of attitudes towards Green Pass strategy and the correlation of these data with vaccinal tendency and demographic characteristics would have provide further elements to discuss the role of the Green Pass; unfortunately, these information were not assessed.

Finally, the second interview took place in December 2021, when the SIV 2021-2022 was not yet concluded. Vaccine tendency was evaluated asking the participants if they had already got a flu vaccine; in case of negative answer, they were questioned about the intention to get it before the end of the campaign. Vaccination acceptance was defined by a positive answer to any of these two questions and the discrepancy between the will to be vaccinated and the actual completion of the vaccination could have introduced a bias.

The main strength of this work resides in its cohort-study nature which allows to longitudinally track the changes in attitudes towards vaccination, in line with the dynamic nature of this phenomenon. Another highlight is represented in the parallel investigation, during the same interview, of tendency towards influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, proving once again that vaccine hesitancy is context-dependent. Moreover, the shared common medical history of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the spring of 2020 – although it could be considered as a source of selection bias – enables us to focus on a peculiar category of population, due to the cruciality of the first pandemic wave in terms of physical, psychological and social impact.

Considering the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy in a dynamic prospective, further efforts are needed to identify the interventions capable of promoting confidence in vaccines, by strengthening trust in the healthcare system and disrupting negative myths.

5. Conclusions

Overcoming vaccine hesitancy remains one of the main current public health challenges. The reasons behind the different choices made by the population are multiple - sometimes conflicting – and difficult to outline and summarize. Osterholm et al. have elaborated a context-specific explanation of vaccine hesitancy [

16] and, in this definition, we suggest to incorporate the role of the single subject, as addressee of the vaccine and protagonist of the context.

In this perspective, the findings coming from our research could help to achieve a better understanding of the evolution of vaccine hesitancy during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, thus to improve public health strategies.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1. Supplementary table 2. Supplementary table 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Valentina Gerussi, Maddalena Peghin, Alvisa Palese and Miriam Isola; Methodology, Maria De Martino and Miriam Isola; Software, Maria De Martino and Miriam Isola; Validation, Alvisa Palese; Formal analysis, Maria De Martino; Investigation, Alvisa Palese and Miriam Isola; Data curation, Valentina Gerussi, Elena Graziano, Stefania Chiappinotto, Federico Fonda, Giulia Bontempo, Tosca Semenzin and Luca Martini; Writing – original draft, Valentina Gerussi and Maria De Martino; Writing – review & editing, Maddalena Peghin, Alvisa Palese, Elena Graziano, Miriam Isola and Carlo Tascini; Visualization, Carlo Tascini; Supervision, Maddalena Peghin and Alvisa Palese; Project administration, Carlo Tascini..

Funding

This research was funded by PRIN 2017 n.20178S4EK9—“Innovative Statistical methods in biomedical research on biomarkers: from their identification to their use in clinical practice”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Udine and Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale (CEUR-2020-OS-219/CEUR-2020-OS-205).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from thecorresponding author (M.P.). The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this survey. We would also like to thank all the nurses who helped us in performing the interviews. Despite the hard period and thegreat amount of work, they found time for supporting us with their efficient and professional help.

Conflicts of Interest

Maddalena Peghin reports grants and personal fees from Pfizer, MSD, and Dia Sorin outside the submitted work. Carlo Tascini has received non conditional grants and personal fees from Pfizer, MSD, Angelini, Shonogi, Nordic, Hikma, Avir Pharma, Biomerieux, Menarini, Zambon, Biotest, Thermofischer outside the submitted work. Other authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 12/05/2023).

- Petrova, V.N.; Russell, C.A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, P.; Mereckiene, J.; Cotter, S.; Johansen, K.; Tsolova, S.; Brown, C. How Close Are Countries of the WHO European Region to Achieving the Goal of Vaccinating 75% of Key Risk Groups against Influenza? Results from National Surveys on Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Programmes, 2008/2009 to 2014/2015. Vaccine 2018, 36, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Italy. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/home.html (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Commissario straordinario per l'emergenza COVID-19 - Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri. COVID-19 Opendata Vaccini. Available online: https://github.com/italia/covid19-opendata-vaccini (accessed on 12/05/2023).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2021/953 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2021 on a framework for the issuance, verification and acceptance of interoperable COVID-19 vaccination, test and recovery certificates (EU Digital COVID Certificate) to facilitate free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021.

- Stefanizzi, P.; Bianchi, F.P.; Brescia, N.; Ferorelli, D.; Tafuri, S. Vaccination strategies between compulsion and incentives. The Italian Green Pass experience. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022, 21, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgio, A.; Kuvačić, G.; Maleš, D.; Vecchio, I.; Tornali, C.; Ishac, W.; Ramaci, T.; Barattucci, M.; Milavić, B. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Booster Vaccine: Associations between Green-Pass, Social Media Information, Anti-Vax Beliefs, and Emotional Balance. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo Italiano. Decreto-legge 24 marzo 2022 Misure urgenti per il superamento delle misure di contrasto alla diffusione dell’epidemia da COVID-19, in conseguenza della cessazione dello stato di emergenza. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Report Vacccini Anti-COVID-19. Available online: https://www.governo.it/it/cscovid19/report-vaccini/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Le vaccinazioni in Italia. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/vaccini/dati_Ita#flu (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Vaccinazione antinfluenzale. Tavole. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_tavole_19_3_1_file.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Peghin, M.; Bouza, E.; Fabris, M.; De Martino, M.; Palese, A.; Bontempo,G. ; Graziano, E.; Gerussi, V.; Bressan, V.; Sartor, A.; Isola, M.; Tascini, C.; Curcio, F. Low risk of reinfections and relation with serological response after recovery from the first wave of COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, 40, 2597–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerussi, V.; Peghin, M.; Palese, A.; Bressan, V.; Visintini, E.; Bontempo, G.; Graziano, E.; De Martino, M.; Isola, M.; Tascini, C. Vaccine Hesitancy among Italian Patients Recovered from COVID-19 Infection towards Influenza and Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Osterholm, M.T.; Kelley, N.S.; Sommer, A.; Belongia, E.A. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012, 12, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, A.; Galli, M.; Maggi, S.; Noale, M.; Trevisan, C.; Pagani, G.; Antonelli-Incalzi, R.; Molinaro, S.; Bastiani, L.; Cori, L.; et al. Influenza Vaccination Uptake in the General Italian Population during the 2020-2021 Flu Season: Data from the EPICOVID-19 Online Web-Based Survey. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C.; Lastrucci, V.; Zanella, B.; Gori, E.; Chiesi, F.; Bechini, A.; Boccalini, S.; Del Riccio, M.; Moscadelli, A.; Puggelli, F.; et al. Predictors of Influenza Vaccination Uptake and the Role of Health Literacy among Health and Social Care Volunteers in the Province of Prato (Italy). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Methods for assessing influenza vaccination coverage in target groups. 2016.

- Harris, J.A.; Moniz, M.H.; Iott, B.; Power, R.; Griggs, J.J. Obesity and the receipt of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Obes 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, G.; Cherif, I.; Bouabid, L.; Gharbi, A.; Boukthir, A.; Ben Alaya, N.; Ben Salah, A.; Bettaieb, J. Influenza vaccination knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Tunisian elderly with chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cori, L.; Curzio, O.; Adorni, F.; Prinelli, F.; Noale, M.; Trevisan, C.; Fortunato, L.; Giacomelli, A.; Bianchi, F. Fear of COVID-19 for Individuals and Family Members: Indications from the National Cross-Sectional Study of the EPICOVID19 Web-Based Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.; Thanner, M. Pharmacists' attitudes toward influenza vaccination: does the COVID-19 pandemic make a difference? Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm 2023, 9, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arda, B.; Durusoy, R.; Yamazhan, T.; Sipahi, O.R.; Taşbakan, M.; Pullukçu, H.; Erdem, E.; Ulusoy, S. Did the pandemic have an impact on influenza vaccination attitude? A survey among health care workers. BMC Infect Dis 2011, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassianos, G.; Banerjee, A.; Baron-Papillon, F.; Hampson, A.W.; McElhaney, J.E.; McGeer, A.; Rigoine de Fougerolles, T.; Rothholz, M.; Seale, H.; Tan, L.J.; et al. Key policy and programmatic factors to improve influenza vaccination rates based on the experience from four high-performing countries. Drugs Context 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, E.W.; Lam, I.O.; Chan, T.M. What factors affect influenza vaccine uptake among community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong general outpatient clinics? J Clin Nurs 2009, 18, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, A.; Zecevic, A.; Diachun, L. Influenza vaccinations: older adults' decision-making process. Can J Aging 2014, 33, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Kamarulzaman, A.; El-Mohandes, A. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nature Medicine 2023, 29, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. How COVID-19 is changing the cold and flu season. Nature 2020, 588, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgio, A.; Kuvačić, G.; Maleš, D.; Vecchio, I.; Tornali, C.; Ishac, W.; Ramaci, T.; Barattucci, M.; Milavić, B. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Booster Vaccine: Associations between Green-Pass, Social Media Information, Anti-Vax Beliefs, and Emotional Balance. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mills, M.C.; Rüttenauer, T. The effect of mandatory COVID-19 certificates on vaccine uptake: synthetic-control modelling of six countries. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e15–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, G.; Carpinelli, L.; Savarese, G.; De Caro, F. Vaccine Hesitancy and the Green Digital Pass: A Study on Adherence to the Italian COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deml, M.J.; Githaiga, J.N. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e066615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).