Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

29 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

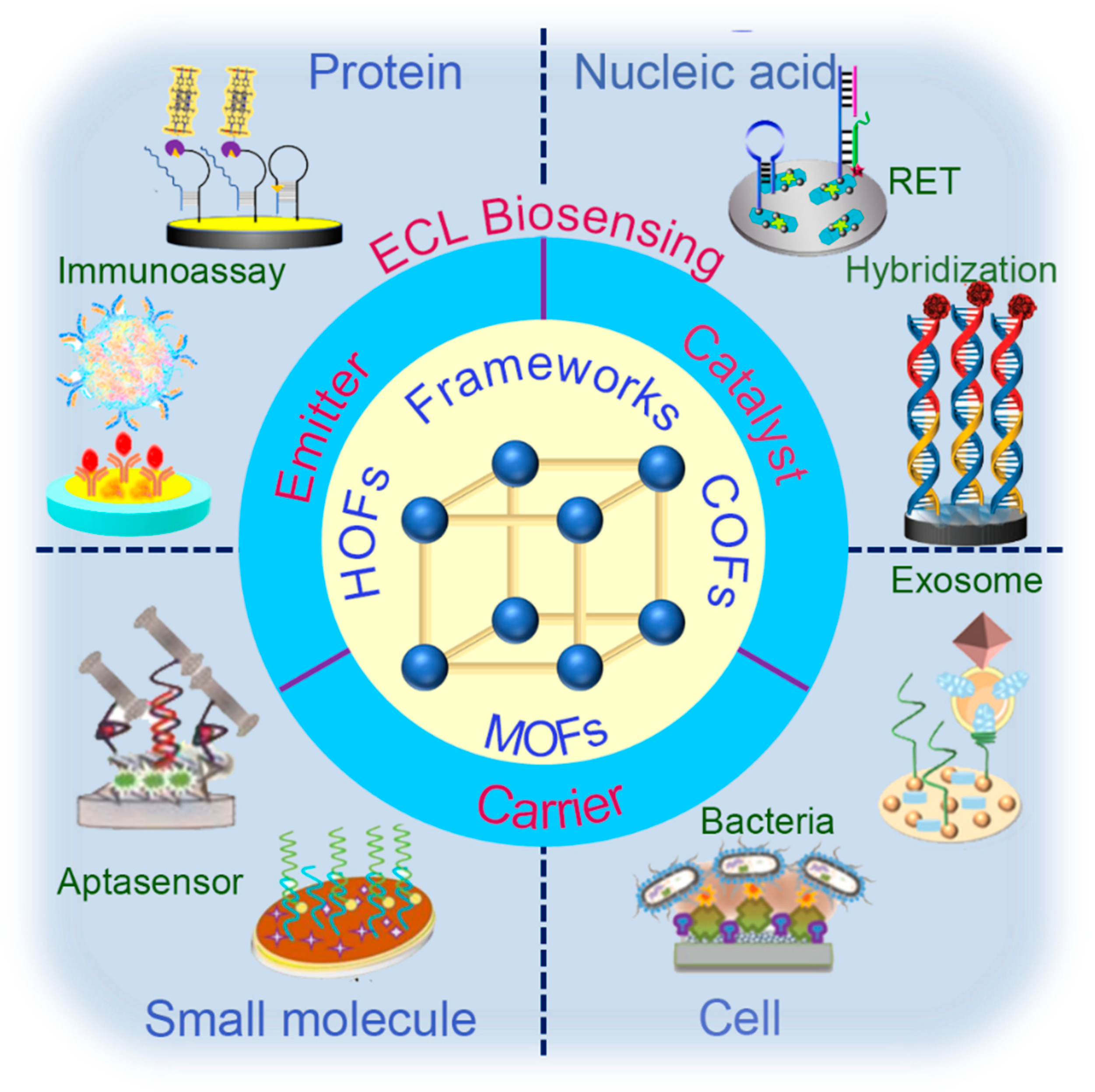

2. The Roles of Frameworks in ECL Processes

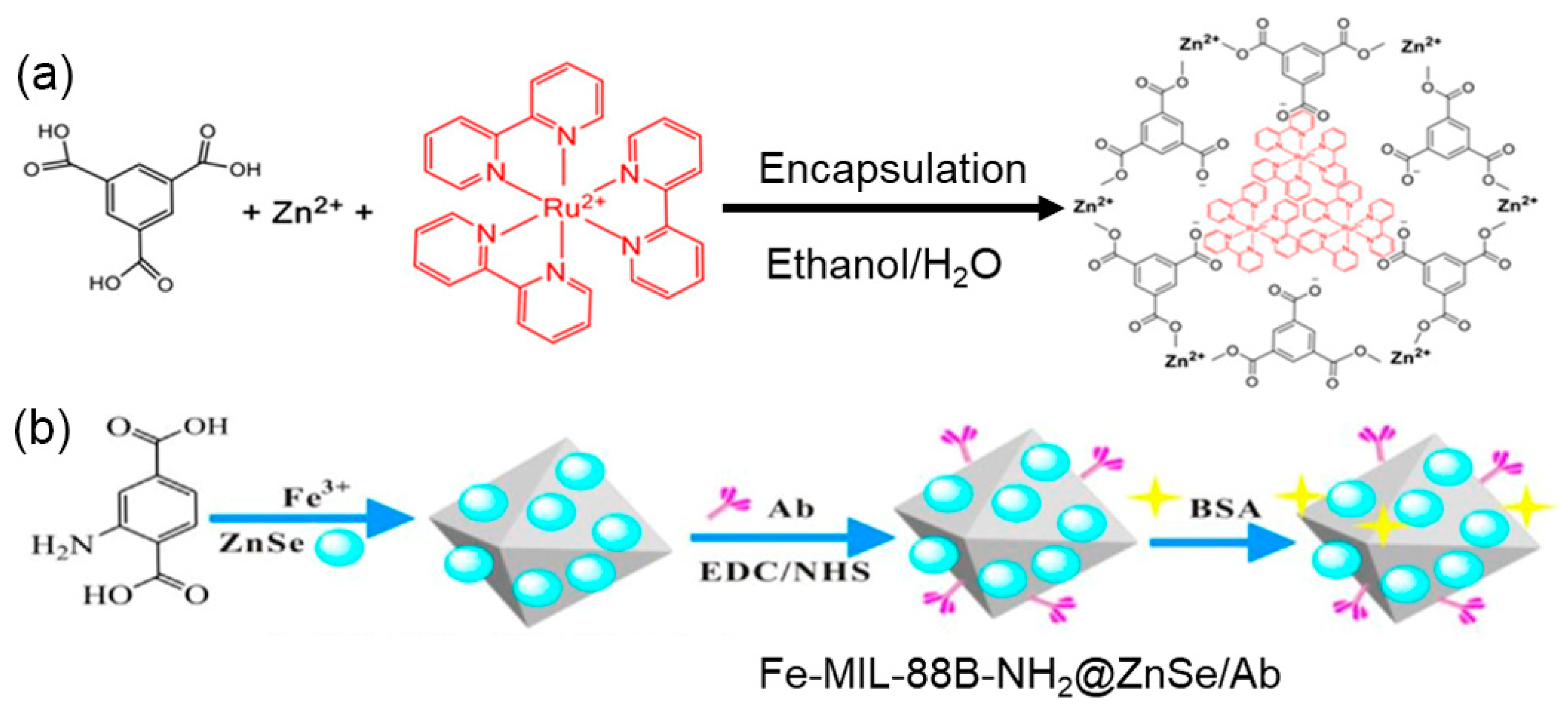

2.1. The Carriers of ECL Luminophores

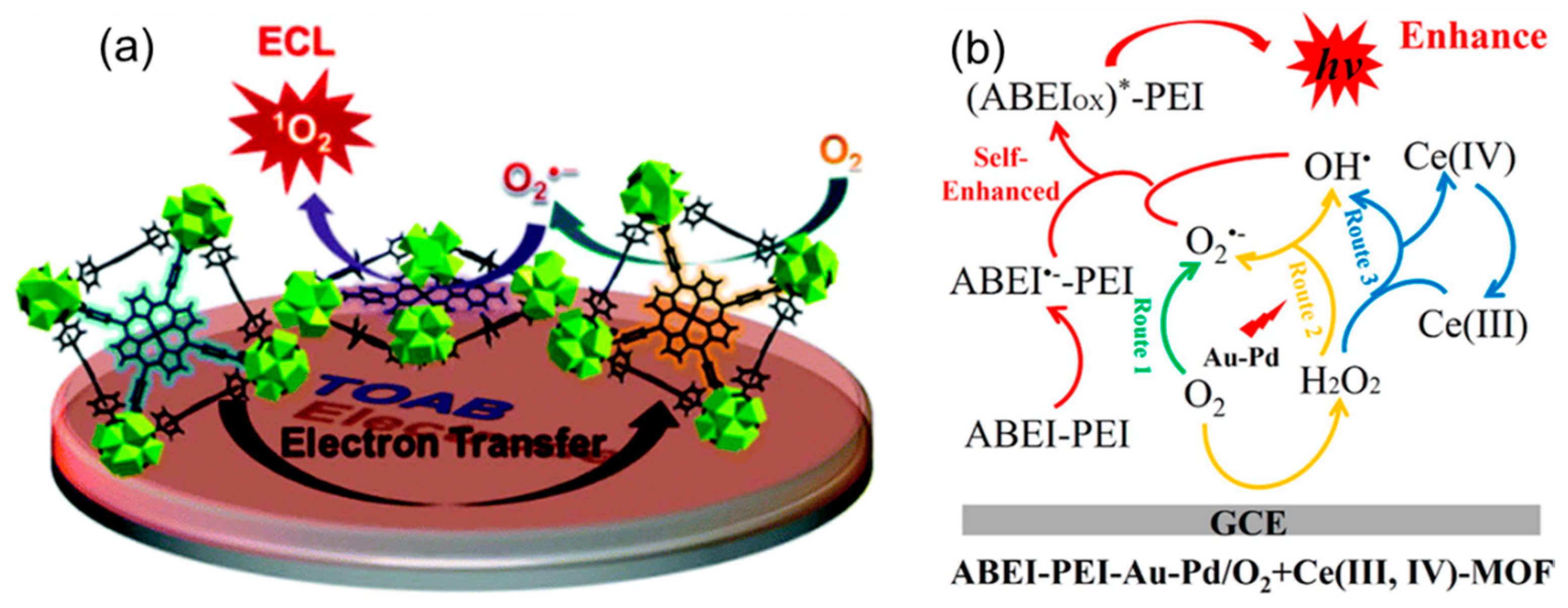

2.2. The Catalyst in ECL Processes

2.3. ECL nanoemitters

3. Framework-Enhanced ECL for Biosensing

3.1. Proteins

3.2. Nucleic Acids

3.3. Small molecules

3.4. Cellular analysis

4. Conclusion and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miao, W. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence and its biorelated applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2506–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.M. Electrochemiluminescence (ECL). Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3003–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Hou, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, H. Electrochemically generated versus photoexcited luminescence from semiconductor nanomaterials: bridging the valley between two worlds. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11027–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Lei, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Yi, H.; Liao, Y.; Chen, L.; Xiao, Y. Simple, rapid, and visual electrochemiluminescence sensor for on-site catechol analysis. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 17330–17336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Chen, W.; Jin, Z.; Lei, J.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Dual intramolecular electron transfer for in situ coreactant embedded electrochemiluminescence microimaging of membrane protein. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J. Direct imaging of single-molecule electrochemical reactions in solution. Nature 2021, 596, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.; Wei, Z.; Yuan, R.; Qian, J.; Long, L.; Wang, K. Sensitive and stable detection of deoxynivalenol based on electrochemiluminescence aptasensor enhanced by 0D/2D homojunction effect in food analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pei, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Donor-acceptor structure-dependent electrochemiluminescence sensor for accurate uranium detection in drinking water. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 14665–14670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, M.; Yan, H.; Lu, C.; Xu, J. Recent advances in aggregation-induced electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 12671–12683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, D.; Padelford, J.W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, G. Near-infrared electrogenerated chemiluminescence from aqueous soluble lipoic acid Au nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6380–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. J.; Brown, K.; Dennany, L. Cathodic quantum dot facilitated electrochemiluminescent detection in blood. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 12944–12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Ju, H.; Lei, J. Electroactive metal-organic frameworks as emitters for self-enhanced electrochemiluminescence in aqueous medium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10446–10450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, K.; He, T.; Liu, R.; Dalapati, S.; Tan, K.T.; Li, Z.; Tao, S.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8814–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, H. Metal-organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yin, X.B.; He, X.W.; Zhang, Y.K. Electrochemistry and electrochemiluminescence from a redox-active metal-organic framework. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 68, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Fu, H.; Yan, T.; Lei, J. Electroactive metal-organic framework composites: Design and biosensing application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 146, 111743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, D.; Shao, Y. Fabrication of tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II)-functionalized metal-organic framework thin films by electrochemically assisted self-assembly technique for electrochemiluminescent immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 11622–11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Yan, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Nie, F.; Yang, G. A sandwich electrochemiluminescent assay for determination of concanavalin A with triple signal amplification based on MoS2NF@MWCNTs modified electrode and Zn-MOF encapsulated luminol. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, G.; Qin, D.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, X.; Mo, W.; Deng, B. A sensitive electrochemiluminescence biosensor based on metal-organic framework and imprinted polymer for squamous cell carcinoma antigen detection. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 310, 127852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Shao, Y. In situ growing triethanolamine-functionalized metal-organic frameworks on two-dimensional carbon nanosheets for electrochemiluminescent immunoassay. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2351–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheroni, D.; Lan, G.; Lin, W. Efficient electrocatalytic proton reduction with carbon nanotube-supported metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15591–15595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Saqib, M.; Ge, C.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. Enhancing luminol electrochemiluminescence by combined use of cobalt-based metal organic frameworks and silver nanoparticles and its application in ultrasensitive detection of cardiac troponin I. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 3048–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Tan, X.; Wu, Y.; Ai, C.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Q.; Han, H. Electrochemiluminecence nanogears aptasensor based on MIL-53(Fe)@CdS for multiplexed detection of kanamycin and neomycin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 129, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Liu, B. Nanoconfinement-enhanced electrochemiluminescence for in situ imaging of single biomolecules. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 3809–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, C.S.; Liu, Y.; Cordova, K.E.; Yaghi, O.M. The role of reticular chemistry in the design of CO2 reduction catalysts. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Gao, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Liu, Z.; Lin, J.; Kasemchainan, J.; Wang, L.; Jia, Q.; Wang, G. Electrostatic potential-derived charge: a universal OER performance descriptor for MOFs. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 13160–13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cai, C.; Cosnier, S.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, X.; Shan, D. Zirconium-metalloporphyrin frameworks as a three-in-one platform possessing oxygen nanocage, electron media, and bonding site for electrochemiluminescence protein kinase activity assay. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 11649–11657. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Peng, L.; Lei, Y.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. Strong electrochemiluminescence from MOF accelerator enriched quantum dots for enhanced sensing of trace cTnI. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3995–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, D.; Wu, Z; Yang, K. ; Sun, S.; Wen, J. Metal-organic layers-catalyzed amplification of electrochemiluminescence signal and its application for immunosensor construction. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2023, 376, 133004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yu, S.; Zhao, L. Guo, Y.; Ren, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, S.; Luo, C.; Li, Y.; Wei, Q. Efficient ABEI-dissolved O2-Ce(III, IV)-MOF ternary electrochemiluminescent system combined with self-assembled microfluidic chips for bioanalysis. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 9363–9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Tan, X.; Lu, Z.; Han, H. Metal-organic frameworks-based sensitive electrochemiluminescence biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 164, 112332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, C.A.; Mehl, B.P.; Ma, L.; Papanikolas, J.M.; Meyer, T.J.; Lin, W. Energy transfer dynamics in metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12767–12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Li, T.; Cao, S.; Chen, Y.; Fu, W. Incorporation of a [Ru(dcbpy)(bpy)2]2+ photosensitizer and a Pt(dcbpy)Cl2 catalyst into metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from aqueous solution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 10386–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

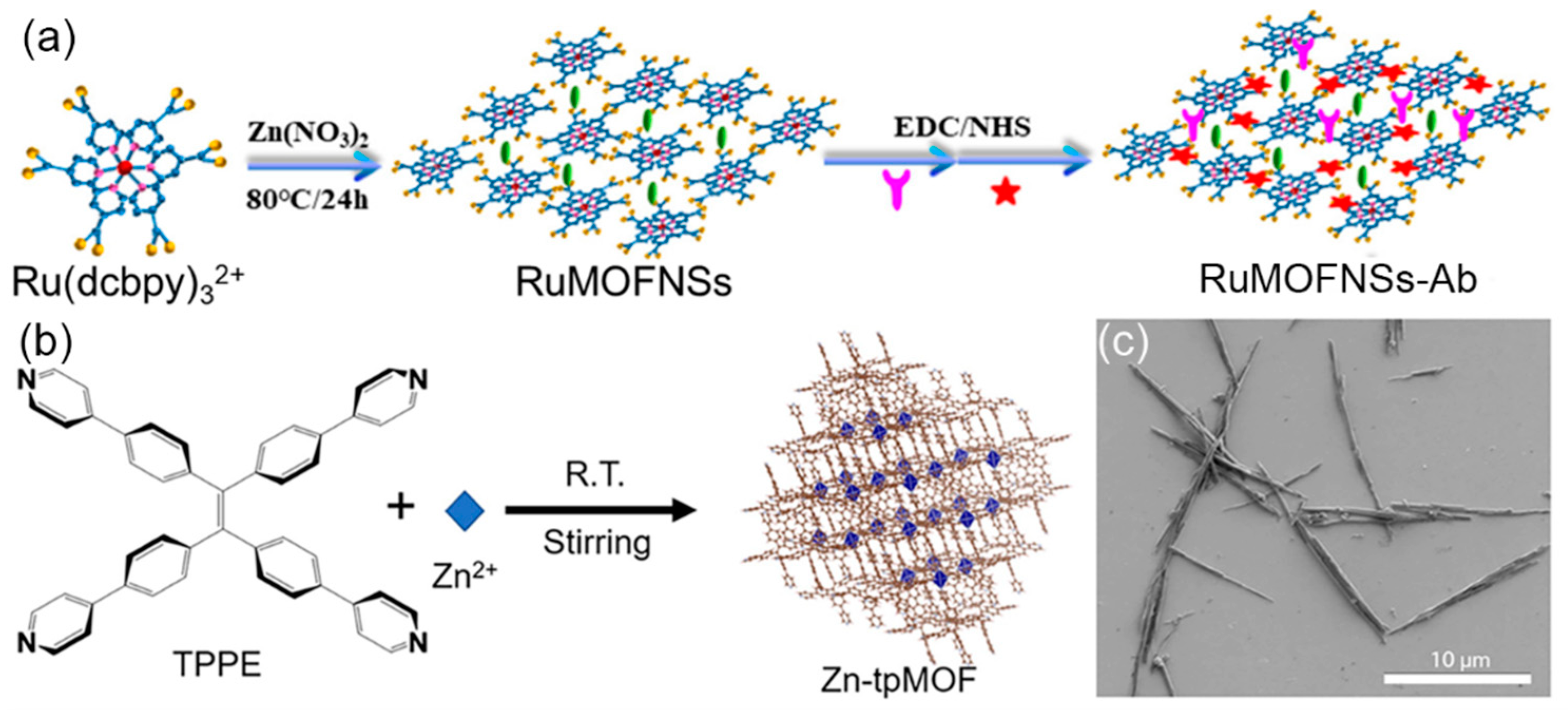

- Yan, M.; Ye, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Huang, J.; Yang, X. Ultrasensitive immunosensor for cardiac troponin I detection based on the electrochemiluminescence of 2D Ru-MOF nanosheets. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10156–10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Xiong, C.; Liang, W.; Zeng, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Yao, L.Y.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Highly stable mesoporous luminescence-functionalized MOF with excellent electrochemiluminescence property for ultrasensitive immunosensor construction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 15913–15919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, G.; Liang, W.; Yao, L.; Huang, W.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. A highly sensitive self-enhanced aptasensor based on a stable ultrathin 2D metal-organic layer with outstanding electrochemiluminescence property. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 10056–10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Fu, X.; Mao, W.; Li, W.; Yu, C. Novel Ce(III)-metal organic framework with a luminescent property to fabricate an electrochemiluminescence immunosensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Overcoming aggregation-induced quenching by metal-organic framework for electrochemiluminescence (ECL) enhancement: ZnPTC as a new ECL emitter for ultrasensitive MicroRNAs detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 44079–44085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Yang, F.; Hu, G.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.; Liang, W.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM) by metal-organic frameworks for electrochemiluminescence enhancement: 2D Zr12-adb nanoplate as a novel ECL tag for the construction of biosensing platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 155, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y. Li, Z.; Bai, L.; Huo, S.; Lu, X. Substituent-induced aggregated state electrochemiluminescence of tetraphenylethene derivatives. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 8676–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhuo, Y.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Near-infrared aggregation-induced enhanced electrochemiluminescence from tetraphenylethylene nanocrystals: a new generation of ECL emitters. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 4497–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, T.; Lei, J. In situ coordination interactions between metal-organic framework nanoemitters and coreactants for enhanced electrochemiluminescence in biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 222, 114920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jia, H.; Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, R.; Ma, H.; Wei, Q. Dumbbell plate-shaped AIEgen-based luminescent MOF with high quantum yield as self-enhanced ECL tags: mechanism insights and biosensing application. Small 2022, 18, 2106567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, G.; Liang, W.; Yao, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. An AIEgen-based 2D ultrathin metal-organic layer as an electrochemiluminescence platform for ultrasensitive biosensing of carcinoembryonic antigen. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 5932–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.T.K.; Leung, C.W.T.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Biosensing by luminogens with aggregation-induced emission characteristics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4228–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiwasuku, T.; Chuaephon, A.; Habarakada, U.; Boonmak, J.; Puangmali, T.; Kielar, F.; Harding, D.J.; Youngme, S. A water-stable lanthanide-based MOF as a highly sensitive sensor for the selective detection of paraquat in agricultural products. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 2761–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wei, X.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Wei, T.; Dai, Z. Co-quenching effect between lanthanum metal-organic frameworks luminophore and crystal violet for enhanced electrochemiluminescence gene detection. Small 2021, 17, 2103424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Chi, H.; Yang, S.; Niu, Q.; Wu, D.; Cao, W.; Li, T.; Ma, H.; Wei, Q. Self-luminescent lanthanide metal-organic frameworks as signal probes in electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, S.; Arcudi, F.; Prato, M.; De Cola, L. Amine-rich nitrogen-doped carbon nanodots as a platform for self-enhancing electrochemiluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4757–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Wang, N.; Yu, S.; Luo, R.; Ma, J.; Ju, H.; Lei, J. Dual intrareticular oxidation of mixed-ligand metal-organic frameworks for stepwise electrochemiluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3049–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. .; Cui, W.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Liang, R.; Luo, Q.; Qiu, J. A general design approach toward covalent organic frameworks for highly efficient electrochemiluminescence. Nat. Comunn. 2021, 12, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.; Lv, H.; Liao, Q.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Xi, K.; Wu, X.; Ju, H.; Lei, J. Intrareticular charge transfer regulated electrochemiluminescence of donor-acceptor covalent organic frameworks Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, L.; Jin, Y.; Wang, A.; Yuan, P.; He, Y.; Feng, J. Hydrogen bond organic frameworks as a novel electrochemiluminescence luminophore: simple synthesis and ultrasensitive biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 17110–17118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhu, D.; Zhou, J.; Wu, X.; Ju, H.; Lei, J. Intrareticular electron coupling pathway driven electrochemiluminescence in hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 14488–14495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhao, Y.; El-Sayed, R.; Muhammed, M.; Hassan, M. Advances in nanotechnology for cancer biomarkers. Nano Today 2018, 18, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadinejad, A.; Oskuee, R.K.; Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Rezayi, M.; Baradaran, B.; Maleki, A.; Hashemzaei, M.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; de la Guardia, M. Development of biosensors for detection of alpha-fetoprotein: As a major biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 130, 115961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ma, C.; Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Hong, C.; Qi, Y. Two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets: An efficient two-electron oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalyst for boosting cathodic luminol electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, W.; Ma, C.; Zhao, C.; Li, P.; Jiang, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.; Hong, C. MnO2 nanosheet/polydopamine double-quenching Ru(bpy)32+@TMU-3 electrochemiluminescence for ultrasensitive immunosensing of alpha-fetoprotein. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 14697–14705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.; Jia, H.; Xue, J.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Copper doped terbium metal organic framework as emitter for sensitive electrochemiluminescence detection of CYFRA 21-1. Talanta 2022, 238, 123047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Fan, D.; Kuang, X.; Sun, X.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Ru(dcbpy)32+-functionalized γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks as efficient electrochemiluminescence tags for the detection of CYFRA21-1 in human serum. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2023, 378, 133152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hu, G.; Liang, W.; Wang, J.; Lu, M.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Ruthenium(II) complex-grafted hollow hierarchical metal-organic frameworks with superior electrochemiluminescence performance for sensitive assay of thrombin. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 6239–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Luo, L.; Chen, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yao, S. Regulation of the structure of zirconium-based porphyrinic metal-organic framework as highly electrochemiluminescence sensing platform for thrombin. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 5707–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, L.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Conductive covalent organic frameworks with conductivity- and pre-reduction-enhanced electrochemiluminescence for ultrasensitive biosensor construction. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 3685–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

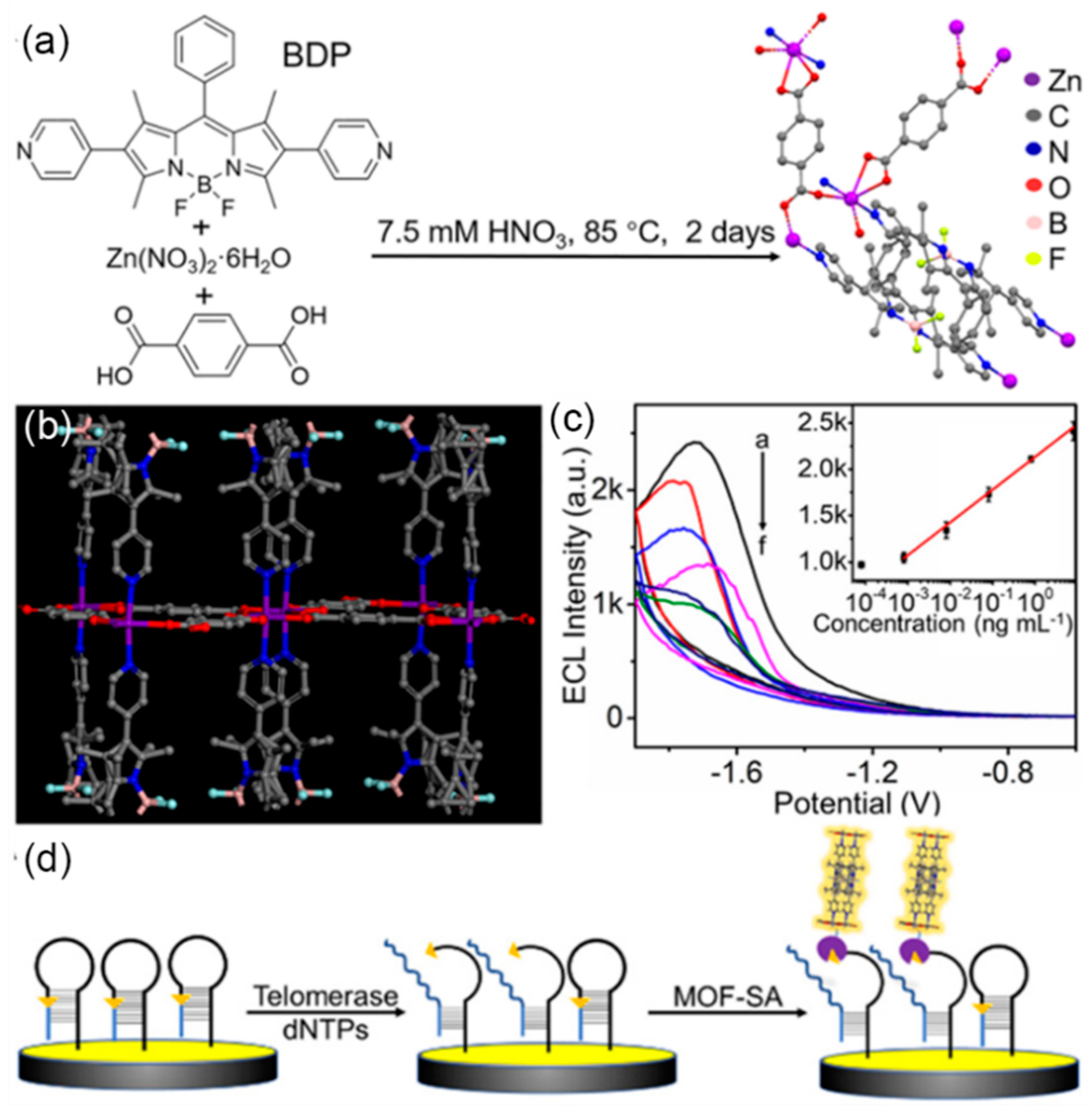

- Xiong, C.; Liang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Ultrasensitive assay for telomerase activity via self-enhanced electrochemiluminescent ruthenium complex doped metal−organic frameworks with high emission efficiency. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 3222–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S. Integration of intracellular telomerase monitoring by electrochemiluminescence technology and targeted cancer therapy by reactive oxygen species. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 8025–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhu, D.; Fu, H.; Shen, Z.; Lei, J. BODIPY-based metal-organic frameworks as efficient electrochemiluminescence emitters for telomerase detection. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 11515–11518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, W. Ultra-sensitive electrochemiluminescence platform based on magnetic metal-organic framework for the highly efficient enrichment. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2020, 324, 128700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, Q.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Nie, G. Electrochemiluminescence and photoelectrochemistry dual-signal immunosensor based on Ru(bpy)32+-functionalized MOF for prostate-specific antigen sensitive detection. Sens. Actuators B 2023, 379, 133269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Wang, B.; Nie, A.; Ye, S.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Lv, Z.; Han, H. Target-triggered signal-on ratiometric electrochemiluminescence sensing of PSA based on MOF/Au/G-quadruplex. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 118, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Cai, R.; Tang, W. Ultrahighly sensitive sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor for selective detection of tumor biomarkers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 44222–44227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Dai, L.; Feng, R.; Wu, D.; Ren, X.; Cao, W.; Ma, H.; Wei, Q. High-performance electrochemiluminescence of a coordination driven J-aggregate K-PTC MOF regulated by metal-phenolic nanoparticles for biomarker analysis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Ju, H. Copper-doped terbium luminescent metal organic framework as an emitter and a co-reaction promoter for amplified electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 14878–14884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Zhu, C.; Hu, J.; Meng, X.; Jiang, M.; Gao, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C. Construction of a dual-mode biosensor for electrochemiluminescent and electrochemical sensing of alkaline phosphatase. Sens. Actuators B 2023, 374, 132779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, C.; Ma, H.; Wu, D.; Cao, W.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q. Dual-quenching mechanisms in electrochemiluminescence immunoassay based on zinc-based MOFs of ruthenium hybrid for D-dimer detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1253, 341076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M. An enzymatically gated catalytic hairpin assembly delivered by lipid nanoparticles for the tumor-specific activation of signal amplification in miRNA imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202214230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, X. An ultrasensitive diagnostic biochip based on biomimetic periodic nanostructure-assisted rolling circle amplification. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6777–6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Gong, X.; Ma, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, F. A Smart, Autocatalytic, DNAzyme biocircuit for in vivo, amplified, microRNA imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5965–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Tran, N. MicroRNAs regulating microRNAs in cancer. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Guo, W.; Wu, X.; Chen, G.; Dai, W.; Zhen, S.; Huang, C.; Li, Y. Controlled synthesis of zinc-metal organic framework microflower with high efficiency electrochemiluminescence for miR-21 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 213, 114443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Liao, N.; Li, Y.; Liang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhuo, Y. Ordered heterogeneity in dual-ligand MOF to enable high electrochemiluminescence efficiency for bioassay with DNA triangular prism as signal switch. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 217, 114713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

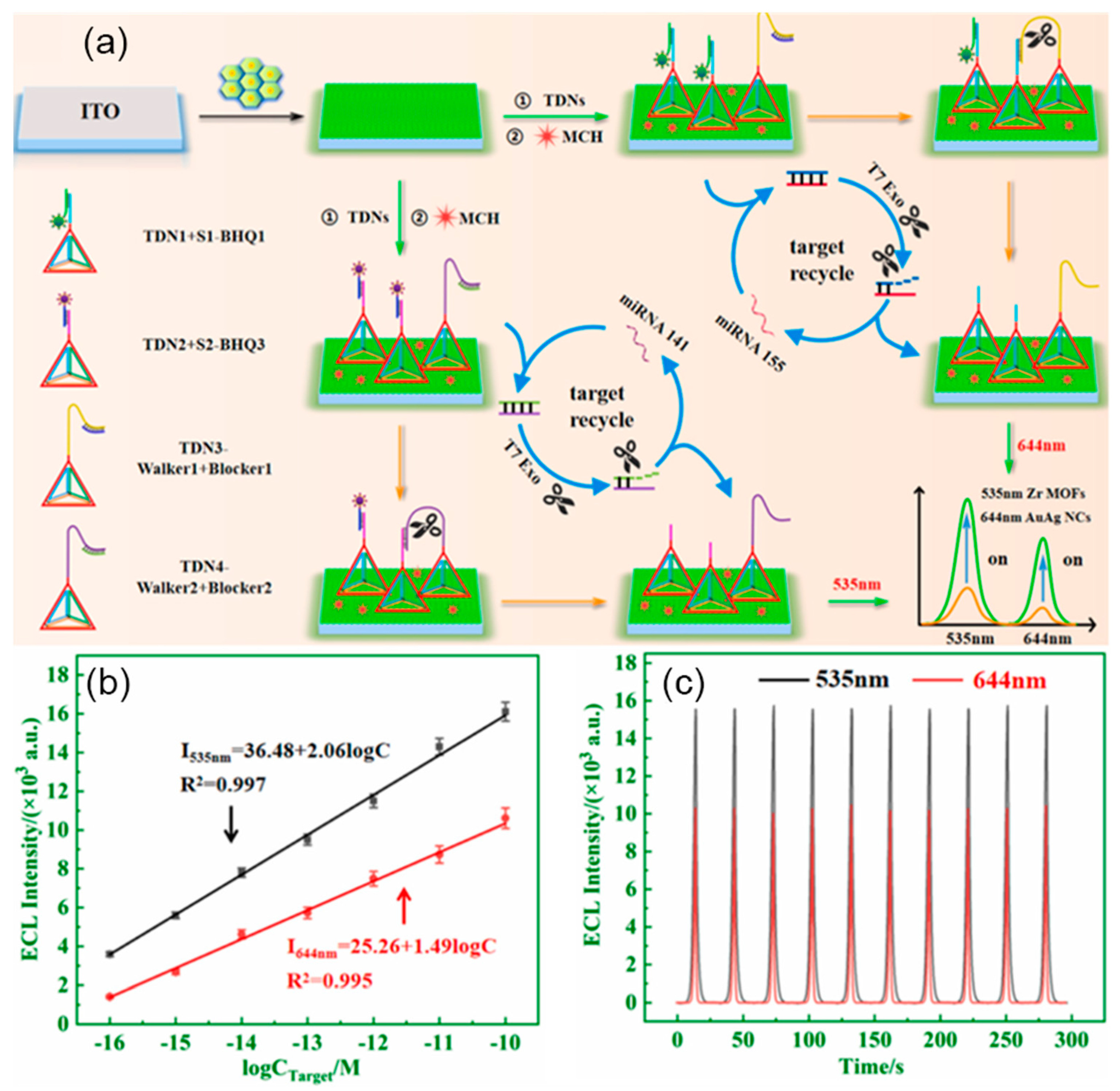

- Yin, T.; Wu, D.; Du, H.; Jie, G. Dual-wavelength electrochemiluminescence biosensor based on a multifunctional Zr MOFs@PEI@AuAg nanocomposite with intramolecular self-enhancing effect for simultaneous detection of dual microRNAs. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 217, 114699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Miao, C.; Jin, B. ORAOV 1 detection made with metal organic frameworks based on Ti3C2Tx MXene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 23726–23733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Conductive NiCo bimetal-organic framework nanorods with conductivity-enhanced electrochemiluminescence for constructing biosensing platform. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 362, 131802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.; Yao, L.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D. Highly stable covalent organic framework nanosheets as a new generation of electrochemiluminescence emitters for ultrasensitive microRNA detection. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3258–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, D.; Gubler, D.J. Zika Virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 487–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Niu, H.; Mao, C.; Jin, B. Metal-organic gel and metal-organic framework based switchable electrochemiluminescence RNA sensing platform for Zika virus. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2020, 321, 128456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, D.; Wang, J.; Shu, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Cosnier, S.; Zeng, H.; Shan, D. 2D Zn-porphyrin-based Co(II)-MOF with 2-methylimidazole sitting axially on the paddle-wheel units: an efficient electrochemiluminescence bioassay for SARS-CoV-2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2209743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

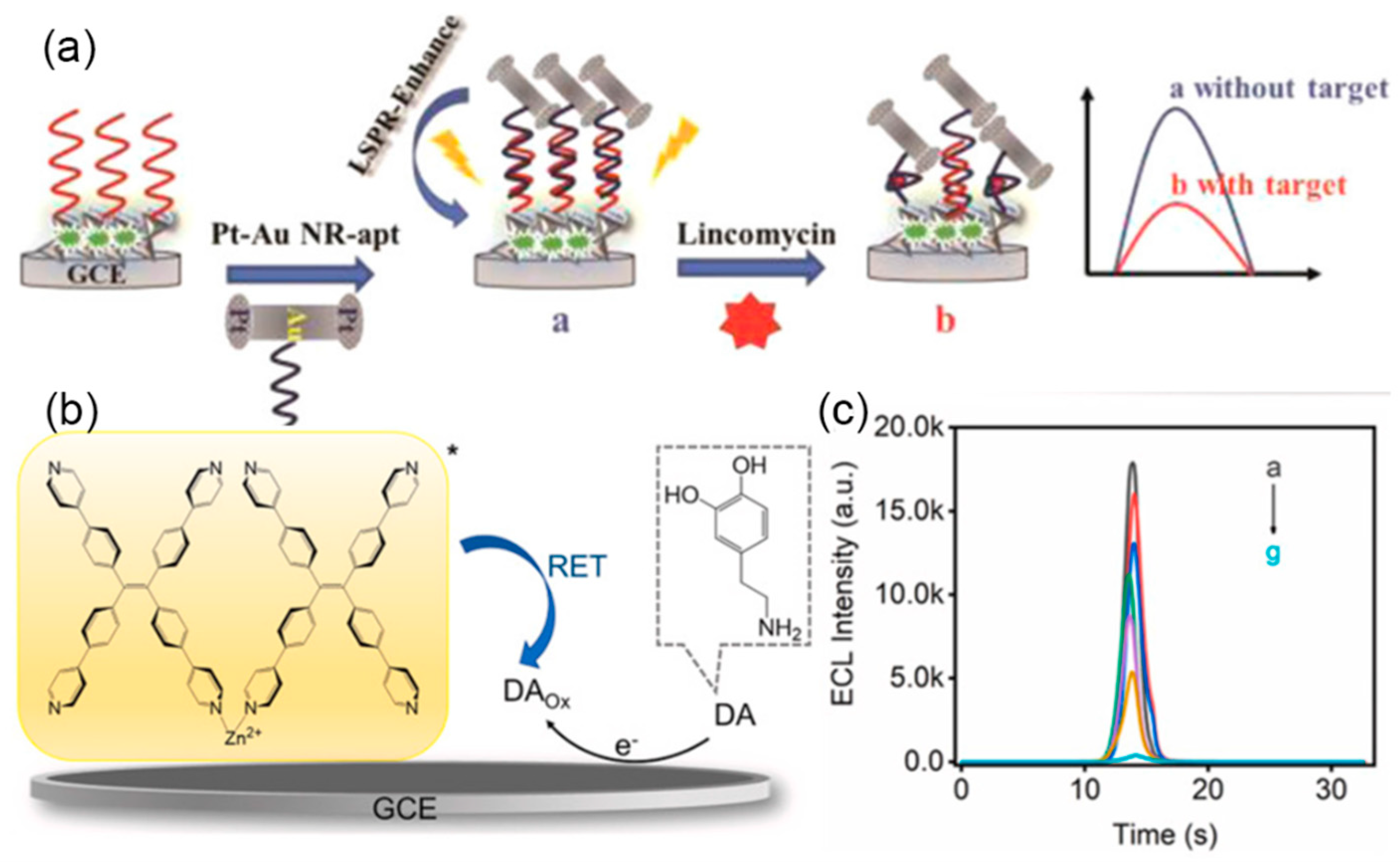

- Li, J.; Luo, M.; Jin, C.; Zhang, P.; Yang, H.; Cai, R.; Tan, W. Plasmon-enhanced electrochemiluminescence of PTP-decorated Eu MOF-based Pt-tpped Au bimetallic nanorods for the lincomycin assay. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, M.; Yang, H.; Ma, C.; Cai, R.; Tan, W. Novel dual-signal electrochemiluminescence aptasensor involving the resonance energy transform system for kanamycin detection. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6410–6416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Zheng, L.; Guo, Q.; Nie, G. A signal “on-off-on”-type electrochemiluminescence aptamer sensor for detection of sulfadimethoxine based on Ru@Zn-oxalate MOF composites. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Zhang, J.; Shen, L.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, A.; Yuan, P.; Feng, J. Hydrogen bond organic frameworks as radical reactors for enhancement in ECL efficiency and their ultrasensitive biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 4735–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Pan, C.; Yang, X.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. CDs assembled metal-organic framework: Exogenous coreactant-free biosensing platform with pore confinement-enhanced electrochemiluminescence. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4803–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhang, H.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Self-assembly of gold nanoclusters into a metal-organic framework with efficient electrochemiluminescence and their application for sensitive detection of rutin. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3445–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yi, H.; Dai, H.; Fang, D.; Hong, Z.; Lin, D.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Y. Fluoro-coumarin silicon phthalocyanine sensitized integrated electrochemiluminescence bioprobe constructed on TiO2 MOFs for the sensing of deoxynivalenol. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018, 269, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Pan, T.; Pan, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Shan, X.; Chen, Z. Highly sensitive and selective detection of Pb (II) by NH2SiO2/Ru(bpy)32+ UiO66 based solid-state ECL sensor. Electroanalysis 2020, 32, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Li, B.; Jiang, D.; Sojic, N.; Liu, B. High electrochemiluminescence from Ru(bpy)32+ embedded metal-organic frameworks to visualize single molecule movement at the cellular membrane. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2204715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Lin, H.; Shao, H.; Hao, T.; Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Su, X. Faraday cage-type aptasensor for dual-mode detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.; Ma, F. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence biosensor based on functionalized two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks for bacterial detection and antimicrobial susceptibility assays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38923–38930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

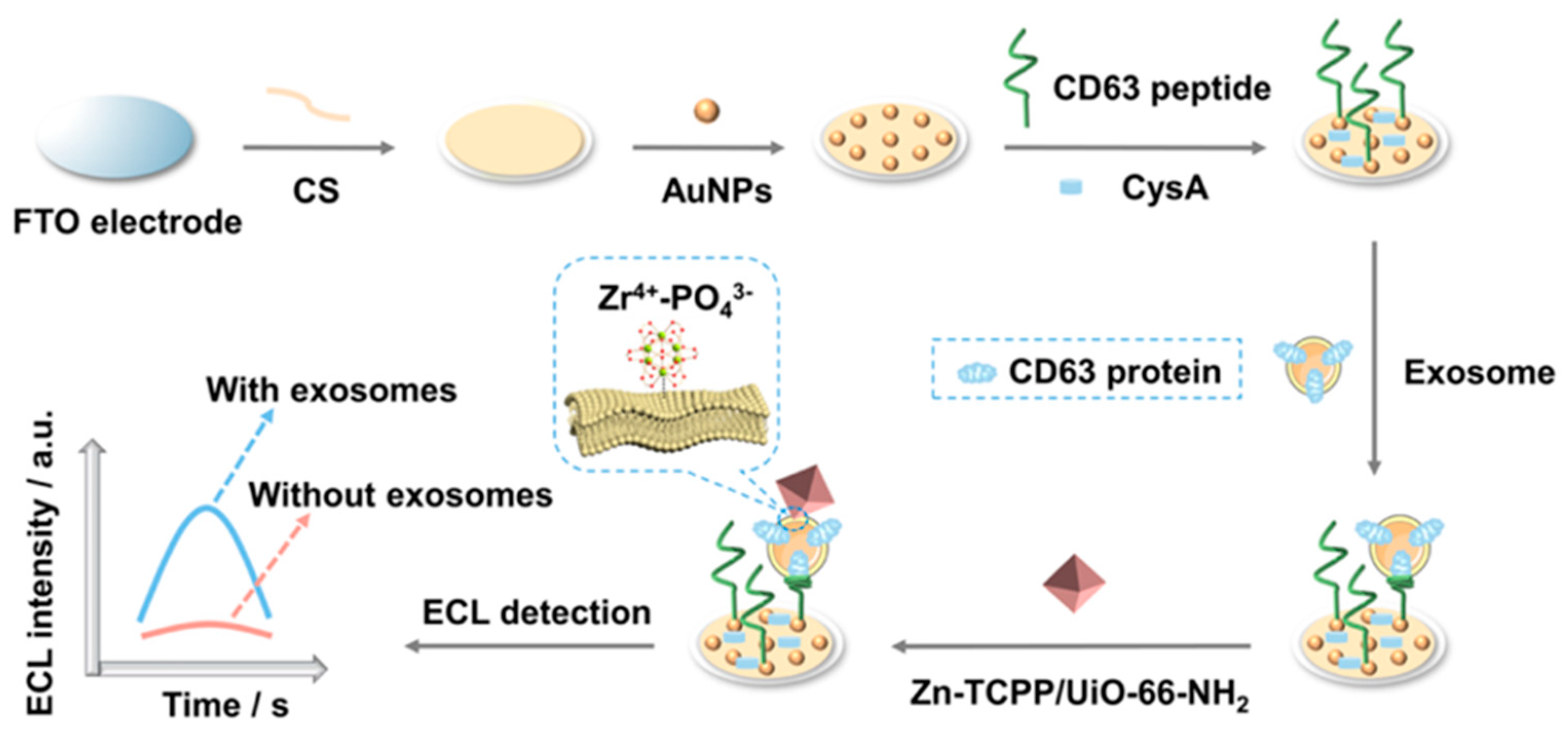

- Wang, Y.; Shu, J.; Lyu, A.; Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Cui, H. Zn2+-modified nonmetal porphyrin-based metal-organic frameworks with improved electrochemiluminescence for nanoscale exosome detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 4214–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Guo, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z. Cyanine-doped lanthanide metal–organic frameworks for near-infrared II bioimaging. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Jiang, D.; Liu, B.; Sojic, N. Single biomolecule imaging by electrochemiluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17910–17914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deneff, J.I.; Rohwer, L.E.S.; Butler, K.S.; Kaehr, B.; Vogel, D.J; Luk, T.S.; Reyes, R.A.; Cruz-Cabrera, A.A.; Martin, J.E.; Sava Gallis, D.F. Orthogonal luminescence lifetime encoding by intermetallic energy transfer in heterometallic rare-earth MOFs. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Li, T.; Yaghi, O.M. Sequencing of metals in multivariate metal-organic frameworks. Science 2020, 369, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Targets | Frameworks | Linear range | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP | NiZn MOF | 0.00005 to 100 ng/mL | 0.98 fg/mL | [58] |

| AFP | Ru(bpy)32+@TMU-3 | 0.01 pg/mL to 5 ng/mL | 10.7 fg/mL | [59] |

| AFP | Magnetic MOF@CdSnS | 1 fg/mL to 100 ng/mL | 0.2 fg/mL | [68] |

| CYFRA21-1 | Pd-ZIF-67 | 0.01 to 100 ng/mL | 2.6 pg/mL | [60] |

| CYFRA21-1 | Ru@ γ-CD-MOF | 0.1 pg/mL to 50 ng/mL | 0.048 pg/mL | [61] |

| Thrombin | Ru-UiO-66-NH2 | 100 fM-100 nM | 31.6 fM | [62] |

| Thrombin | PCN-222 | 50 fg/mL to 100 pg/mL | 2.48 fg/mL | [63] |

| Thrombin | Conductive COF | 100 aM to 1 nM | 62.1 aM | [64] |

| Telomerase | BODIPY MOF | 8.0×10-4 to 8.0 ng/mL | 0.43 pg/mL | [67] |

| PSA | Ru-MOF | 5 pg/mL to 5 μg/mL | 1.78 pg/mL | [69] |

| PSA | MOF/Au/DNAzyme | 0.5 to 500 ng/mL | 0.058 ng/mL | [70] |

| CEA | N,B-doped Eu MOF | 0.1 pg/mL to 1 μg/mL | 0.06 pg/mL | [71] |

| NSE | J-aggregated MOF | 10 pg/mL to 50 ng/mL | 7.4 pg/mL | [72] |

| Peptide | Cu:Tb-MOF | 1.0 pg/mL to 50 ng/mL | 0.68 pg/mL | [73] |

| ALP | π-conjugated COF | 0.01 to 100 U/L | 7.6 × 10- 3 U/L | [74] |

| D-dimer | RuZn MOFs | 0.001~200 ng/mL | 0.20 pg/mL | [75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).