1. Introduction

Several studies targeting patients with lesions in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) have reported impairments in short-term memory function [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recent research evaluating working memory in rats has reported that the coordinated neural activity patterns between the dentate gyrus and the hippocampal CA3 region contribute to working memory [

6], suggesting the potential involvement of the MTL in short-term function. Additionally, it was reported that a heightened propensity for impairments in spatial memory, integral to navigation and self-location, following damage to the right MTL [

7]. Conversely, when the left MTL is compromised, there is an increased likelihood of deficits in verbal memory, essential for memorising the auditory and visual linguistic information.

In recent years, the technique of applying electrical stimulation to deep brain regions has been established, leading to an increase in studies aiming to enhance memory function through electrical stimulation of the MTL [

8]. However, several previous studies investigating electrical stimulation specifically targeting the hippocampus, the central region of the MTL, have reported a decline in memory function [

9,

10,

11,

12], with inconsistent findings across studies. Hescham et al. have suggested that electrical stimulations within the hippocampus may cause an acute depolarization block, leading to memory impairment [

9]. Akin to transcranial electrical stimulation, neurofeedback (NF) exists as a method for modulating brain function. NF involves providing users with real-time feedback of their brain activity, typically in the form of perceptible information such as bar length or circle size, allowing individuals to self-regulate their brain activity. Through repeated NF training, it is expected to facilitate the regulation of cognitive functions associated with brain activity. In recent years, NF has gained momentum in clinical applications, with reports of symptom alleviation in various mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia [

13], and ADHD [

14] by utilising brain activity, a biomarker of symptoms, for NF training. Additionally, there has been an increase in opportunities for NF training in healthy individuals to enhance memory [

15], meditation [

16], and attentional focus [

17]. Since NF relies on the brain’s autonomic learning capability to regulate neural activity, it offers a potentially lower risk of interfering with memory function compared to electrical stimulation methods. Moreover, anatomical evidence reveals that memory function involves multiple brain regions beyond the hippocampus, such as the thalamus, mammillary bodies, and the cingulate gyrus [

18]. In order to regulate such complex neural networks, we believe that a closed-loop control system that provides feedback on MTL neural activity which is closely related to the memory function to be enhanced, and relies on the brain’s autonomic learning capability, would be more rational and effective compared to open-loop control systems that simply deliver external electrical stimulation.

Patients with intractable epilepsy, who undergo intracranial electrode placement through craniotomy for the purpose of epileptic focus diagnosis, provide an opportunity for intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) measurements. Recently, there has been increased interest in applying this invasive brain activity measurement method to brain-computer interfaces [

19]. Signals obtained from intracranial electrodes offer superior temporal resolution compared to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and reduce the impact of artefacts compared to scalp EEG. These advantages of intracranial electrodes can be utilised in NF studies, such as modulating somatosensory-motor function by NF [

20,

21,

22] and modulating emotional function [

23]. However, these approaches are still in their early stages, and in fact, there are few NF studies focusing specifically on memory function in the MTL [

24].

1.1. Learning Mechanisms in Neurofeedback

The mechanism by which NF training allows for the adjustment of brain activity and brain function is believed to be rooted in the learning mechanisms of operant conditioning [

25]. Operant conditioning, a fundamental concept in behavioural psychology, involves increasing or decreasing the occurrence probability of a response under a specific condition by providing a consequence (reinforcement or punishment) in response to voluntary behaviour (operant behaviour). In this context, the "specific condition" serves as an antecedent that function as cue for the voluntary response. Operant conditioning involves learning the association between these antecedent, behaviour, and consequence. The association of these three elements is known as three-term contingency.

In the context of NF, let us consider an illustrative scenario where the user can increase the length of a bar displayed on the screen when a specific brain activity pattern occurs during a specific cognitive condition. Through NF training, as the user engages in trial and error, they may accidentally produce the desired brain activity pattern and achieve success in increasing the length of the bar. Through repeated these experiences, the user’s probability of generating the desired brain activity pattern in a specific cognitive condition gradually increases. In other words, in NF, the user learns the contingency between the specific cognitive condition (antecedent), the brain activity pattern (behaviour), and the success in bar length adjustment (reinforcement).

The presence of consequence (reinforcement or punishment) is crucial for the success of operant conditioning learning. If the reinforcements or punishments following operant behaviour are insufficient, the changes in the occurrence probability of the response will be weak, making it difficult for learning to take place. The importance of consequence can also be applied to the context of NF. Davelaar [

26] proposed a neurophysiological theory of NF, suggesting the significant contribution of the striatum, a part of the reward system, to NF learning. Indeed, several NF studies have reported the observed involvement of the striatum [

27,

28,

29].

1.2. Neurofeedback Research and Challenges in Memory Function

When constructing an NF system aimed at regulating neural activity related to memory function, several challenges need to be considered. In this section, we summarise the challenges of previous NF studies on memory function.

1.2.1. Challenges in Brain Activity Measurement Methods

NF studies targeting memory function have extensively utilised scalp EEG [

15,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Memory function has long been associated with theta oscillations [

38,

39,

40], and an increase in theta power during memory encoding has been reported in numerous EEG studies [

38,

41,

42]. Based on the accumulation of such foundational research, many memory NF studies using EEG have implemented NF to increase theta power. These EEG-NF studies have contributed to the understanding that the upregulation of theta activity in the frontal midline is associated with improved control processes during memory retrieval [

31] and accelerated and enhanced memory consolidation [

33,

36], thus accumulating knowledge regarding the relationship between theta oscillations and memory function. Studies utilising intracranial electrodes have also reported increased theta power in the MTL during successful encoding and retrieval [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], and increased phase synchronization between the hippocampus and other cortical regions (rhinal cortex, prefrontal cortex) during memory encoding [

50,

51]. However, studies also report a decrease in MTL theta power during encoding [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58], and the causal relationship between MTL theta power changes (increases or decreases) and memory function (encoding success or failure) is inconsistent across studies. In our previous study [

24], we conducted NF using iEEG of MTL and reported an increase in theta power in one participant; however, no accompanying changes in memory function were observed.

1.2.2. Challenges in Modulating Memory as a Cognitive Function

In NF studies aiming to improve mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia [

13], and ADHD [

14], as well as enhance brain function in healthy individuals [

15,

16,

17], it is common to perform NF during a resting state without imposing additional tasks on participants. This is because the resting state already corresponds to the "specific cognitive condition" in the learning mechanism of NF. In other words, in mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD, where chronic symptoms persist even during the resting state, NF during the resting state enables the learning of three-term contingency. The same applies to healthy individuals training their attention, relaxation, or meditation using NF. On the other hand, when conducting NF training for memory function, the "specific cognitive condition" corresponds to the condition requiring memory function. Therefore, it is essential to create a situation that necessitates memory function, such as imposing memory tasks on participants, and conduct NF within that context to efficiently learn the three-term contingency and achieve successful memory NF. Traditional memory NF studies have often required several weeks or more for participants to gain self-regulation of brain activity [

15,

59]. We believe this may be attributed to the fact that previous memory NF studies have been conducted during resting states, without creating a situation that necessitates memory function. Additionally, during the resting state, participants lack clues regarding how to control their brain activity to adjust the feedback signal, resulting in higher difficulty in learning self-regulation of brain function and requiring a longer time for the effects to appear. If NF can be conducted within a context that necessitates the desired brain function, rather than during the resting state, participants will have clues on how to modulate their brain activity to change the feedback signal, making it easier to acquire self-regulation of brain function in a shorter period.

However, when participants perform tasks requiring the desired brain function while simultaneously receiving feedback, dual-task interference occurs, diverting attention away from the feedback, making self-regulation difficult. Alternatively, participants may become overly focused on the feedback, neglecting the task. To address these issues, a task-based NF approach has been proposed [

60,

61], where the periods for task performance and feedback are separated, allowing for alternating short periods of task engagement and feedback. This approach enables participants to engage in tasks and feedback without divided attention and allows for conducting NF within a context that requires the desired brain function. In this study, we adopt this task-based NF approach to investigate whether the neural activity in the MTL associated with memory function can be modulated.

1.3. Aims

This study aims to develop a task-based NF system, incorporating memory tasks and NF, and to observe the control of neural activity and resulting effects on memory function through NF training conducted to modulate MTL neural activity in both upward and downward directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In this study, we targeted three patients with intractable epilepsy (P01, P02, P03) who underwent intracranial electrode implantation for clinical purposes at the University of Tokyo Hospital. The characteristics of each participant are shown in

Table 1. The Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FIQ) was evaluated using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-fourth edition (WAIS-IV). Language dominance was assessed using functional MRI before electrode transplantation or cortical electrical stimulation via subdural electrodes during language task [

62]. Through these evaluation methods, it was confirmed that the language-dominant hemisphere for all participants was the left hemisphere. Since language dominance and language memory dominance are often concordant [

63], it was assumed that language memory dominance is also located in the left hemisphere. Prior to the surgery, all participants underwent the Japanese version of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R), with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The index score for P01 was 51, confirming that verbal memory function was impaired, which is speculated to be due to sclerosis in the left hippocampus. The verbal memory of P02 and P03 was found to be within the normal range, with an index score of 102 for P02 and 99 for P03, respectively.

This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo Hospital (Approval No. 1797) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants received sufficient explanations regarding the purpose and content of the study and provided written informed consent.

2.2. Acquisition of iEEG Data

The placement of intracranial electrodes was determined based on clinical purposes, which involved identifying the epileptogenic zone for each participant. The respective electrodes used and their placement locations for each participant are described in the results section. iEEG data were recorded using gUSBamp (gTec, Schiedlberg, Austria) at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz. At the time of acquiring iEEG data, a bandpass filter of 0.1-200 Hz and a notch filter at 50 Hz were applied to the data using the gUSBamp software settings to reduce power line noise.

2.3. Data Acquisition procedure

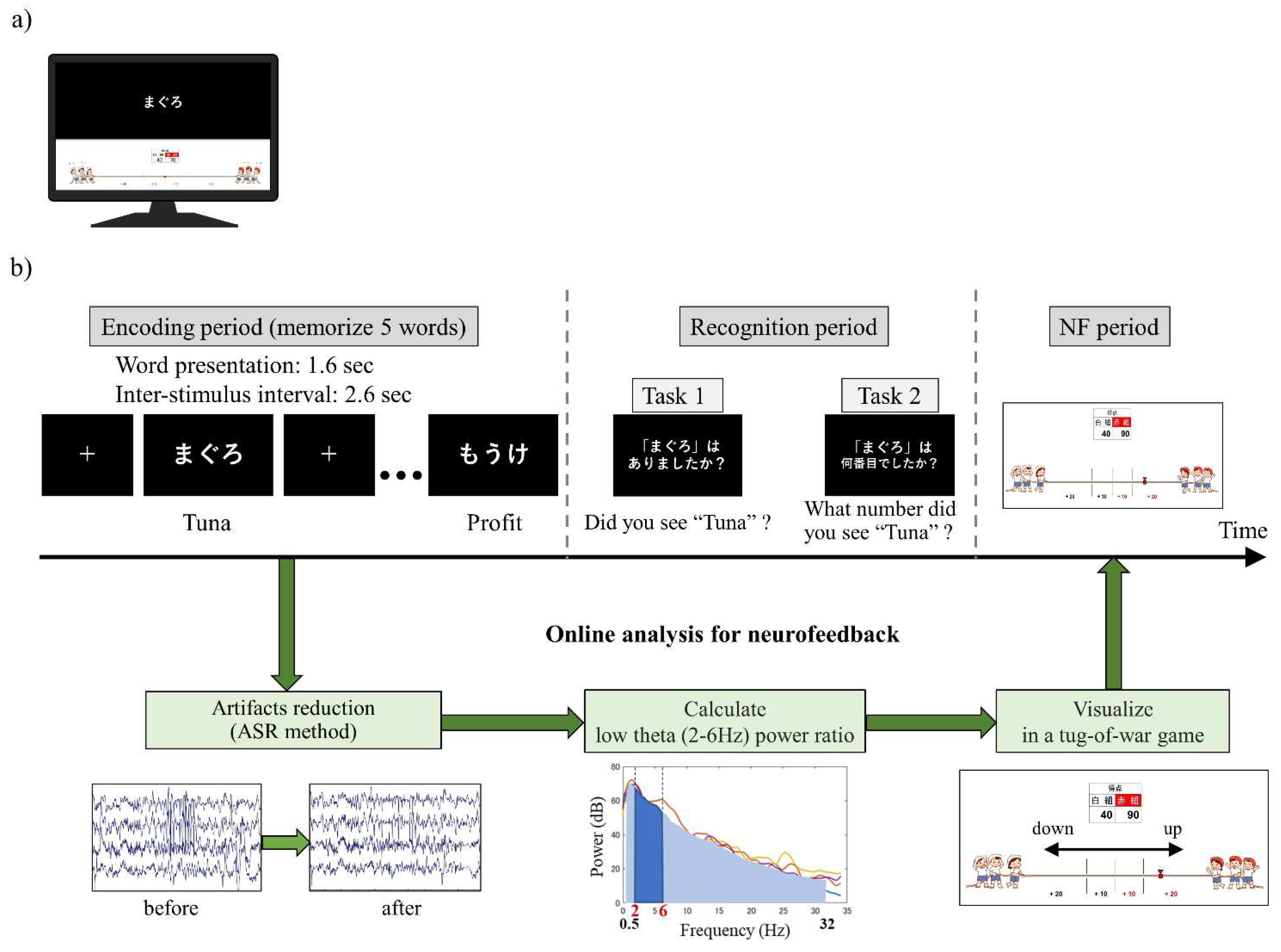

Prior to participating in the study, the participants watched an explanatory video and read an instruction manual to ensure a sufficient understanding of the tasks. The participants were seated in an electrically shielded room and instructed to look at a monitor screen displaying visual stimuli during the tasks. The monitor screen was divided into upper and lower sections by a central line. The upper screen displayed instructional text and the memory task, while the lower screen displayed NF (

Figure 1a).

At the beginning of each session, the participants were instructed to be relaxed while fixating on a fixation point displayed in the centre of the upper screen for 20 seconds. The subsequent memory NF paradigm consisted of 20 trials per session, with each trial comprising a memory task (encoding period followed by recognition period) and an NF period (

Figure 1b). During the encoding period, five words were sequentially presented in the centre of the upper screen for 1.6 seconds each, with a 2.6-second interval between them. The participants were required to memorise these words. In the subsequent recognition period, a single word was presented on the upper screen, and the participants had to determine whether the word was one of the five words presented during the encoding period (recognition task 1) and, if so, what number they saw it (recognition task 2). The question screens for the recognition tasks were presented sequentially for 8 seconds each, and the participants provided their responses using key inputs. In the following NF period, the neural activity in the medial temporal lobe during the encoding period was visually presented as feedback on the lower screen in the form of a tug-of-war game. The duration of each session was set to approximately 15 minutes, considering the physical and mental fatigue of the patients.

2.4. Memory task

The words selected for the memory task were obtained from the Word List by Semantic Principles (WLDP) version 1.0, provided by the Centre for Language Resource Development, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics [

64]. This lexical database comprises 96,557 words and employs crowdsourcing and Bayesian linear mixed models to estimate word familiarity [

65]. Initially, Japanese hiragana or katakana words consisting of three letters or three syllables were extracted to form multiple sets of six words. The word combinations were adjusted to ensure an equal average familiarity score across the sets. Each session included twenty word sets, with one set assigned per trial. twenty word sets were extracted so that they would not overlap across sessions.

During the encoding period, five out of the six words in each set were presented. In the subsequent recognition period, one of the five words presented during encoding was displayed as an "old" stimulus, while the remaining word not presented during encoding was shown as a "new" stimulus. Out of the 20 trials, 10 trials featured the presentation of "old" stimuli and the other 10 trials featured the presentation of "new" stimuli. The sequence of trials with either "old" or "new" stimuli was randomised.

Regarding recognition task 1, the accuracy score (the probability of correctly identifying whether the stimulus was "old" or "new" among all responses) and the recall score (the probability of correctly identifying an "old" stimulus as an "old" stimulus) were calculated. For recognition task 2, the accuracy score (i.e., the probability of correctly identifying the order in which the "old" stimulus was presented in task 1) was computed. As an example, in the trial depicted in

Figure 1b, "Tuna" was the first word presented among the five, indicating that the correct answer for task 2 is "first."

2.5. Neurofeedback

Real-time analysis and feedback of the acquired iEEG data were performed using a custom program developed with g.HIsys (gTec, Schiedlberg, Austria) and MATLAB R2020a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). During the memory encoding period of 13 seconds ((1.0+1.6) s × 5 words), iEEG data were extracted, and an artifact subspace reconstruction [

66,

67] (ASR) was applied to reduce epileptic spike-related artifacts. The ASR parameters were adjusted based on the extent of epileptic spike contamination. Specifically, waveform correction was performed with k = 10 when the proportion of brain wave potentials exceeding the mean ± 3 standard deviations for 13 seconds was less than 1%, with k = 6 when it was between 1% and 1.5%, and with k = 4 when it exceeded 1.5%. Subsequently, the 12 seconds of iEEG data, excluding the initial 1-second period in which the encoding words were not presented, were used to calculate the ratio of low theta band power (2-6 Hz) to the total power (0.5-32 Hz). The average ratio of low theta band power (LTR) across four electrodes was then computed. For each trial (i), the relative magnitude of LTR

i to LTR

1 (LTR

i/1 = 100 × LTR

i/ LTR

1) was used as the neurofeedback (NF) signal.

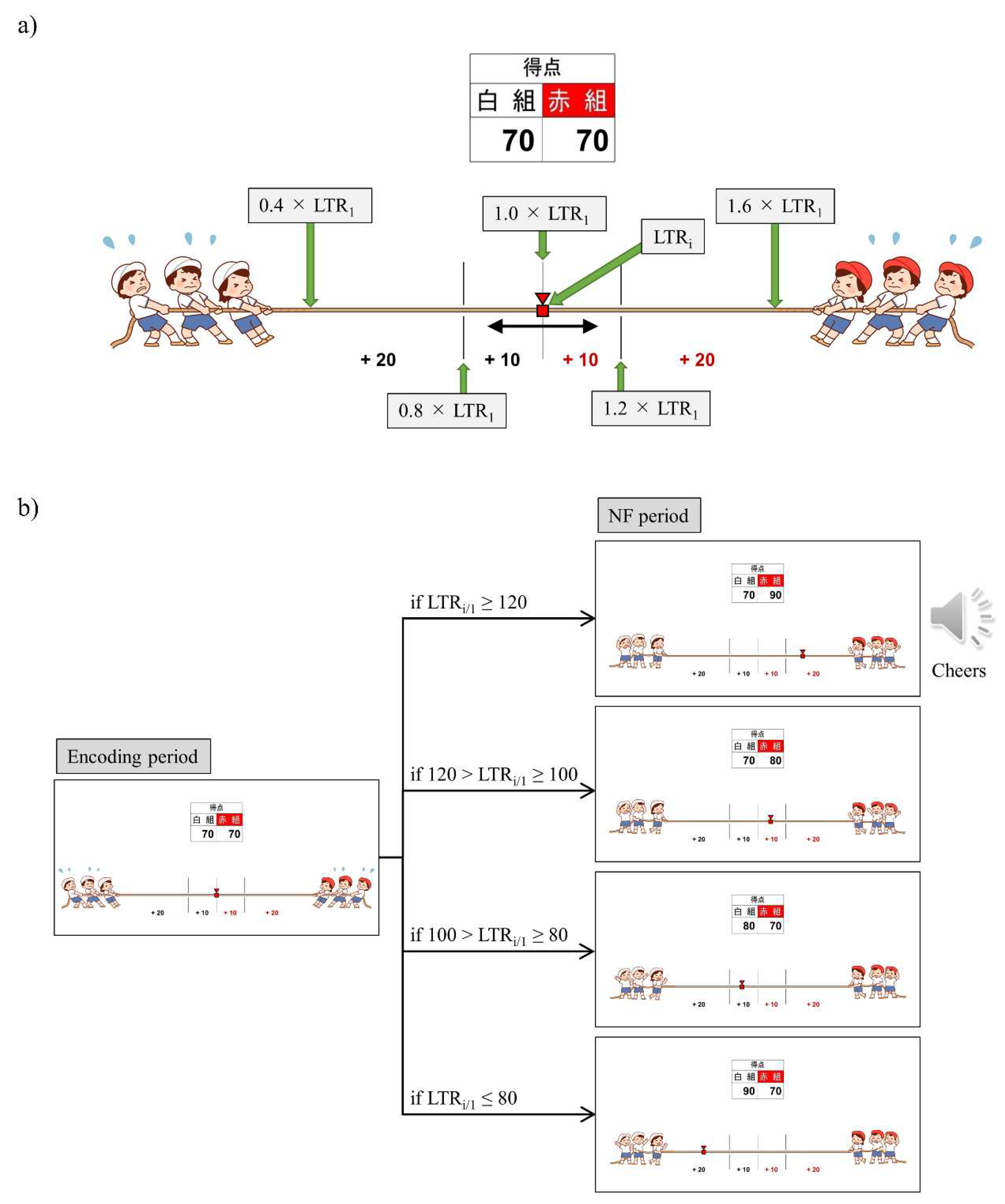

We employed a bidirectional control NF system and introduced gamification and reward elements. The reason for adding gamification and reward elements is that attention, motivation, and mood affect efficient learning and success in NF [

68]. Specifically, we employed a tug-of-war game with 20 trials per session, where a larger LTR

i/1 value caused the rope to be pulled towards the right (red team side), while a smaller LTR

i/1 value resulted in the rope being pulled towards the left (white team side), with the marker moving right and left accordingly (

Figure 2a). Participants were instructed that their brain activity during word memorization would be utilised for a tug-of-war game, and the outcome would be determined after each trial. The participants were also informed about which team to root for before the start of each session (Up/Down conditions based on the direction of adjusting the LTR

i/1 value) and were encouraged to strive for win through trial and error. The Up and Down conditions were alternated between sessions. For P01 and P03, odd-numbered sessions were assigned to Up and even-numbered sessions to Down, while for P02, it was the reverse. The research conductors did not provide explicit instructions regarding mental strategies to the participants, and the correspondence between the Up/Down conditions and the winning/losing teams was blinded. Additionally, the research conductors and data analysts were separate individuals, and the analysts were blinded to the information regarding which condition was used in each session. When the supported team won, 10 points were added to their score. Moreover, if the LTR

i changed by more than 20% from LTR

1 and the supported team won, the score was doubled (20 points), accompanied by the playback of cheering audio. Conversely, if the supported team lost, 10 points were added to the opponent’s score, and if the LTR

i changed by more than 20% from LTR

1 and resulted in the loss of the supported team, the opponent’s score was doubled (20 points). A score table was displayed at the top of the tug-of-war screen, allowing the participants to monitor the cumulative scores for their supported team as the trials progressed.

Figure 2b illustrates the transition of the NF screen from the encoding period to the NF period in trial i of sessions rooting for the red team (Up condition). After completing all 20 trials, the outcome of each session was determined based on the cumulative scores. When the supported team won, a celebration screen and a loud cheer were displayed as audio. In the case of a draw, only a notification was displayed informing the result of a draw. In case of loss, a screen indicating disappointment was shown.

2.6. Offline Data Analysis

To examine how the difference in NF signal values (LTRi/1) between the Up and Down conditions changed before and after NF training, the difference in median NF signal values between trials was calculated for each condition (Up and Down) in both the first and final sessions. Subsequently, these differences were compared between the first and final sessions.

Next, the transition of NF signal values (LTRi/1) between sessions and within sessions was examined for each participant. The transition between sessions for LTRi was also investigated. Statistical analyses were conducted to determine if there were significant increases or decreases in the transition of these values between sessions. Nonparametric tests were employed for all statistical analyses conducted across all participants due to the lack of normality in the distribution of some data, as assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. For each session, the median of LTRi/1, which represented the NF signal values from trial 2 to trial 20, was compared to the baseline, the LTR1/1 value (100) of trial 1, using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Additionally, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed to examine if there were differences between the conditions at the same session number, and if there were changes across sessions within the same condition. The effect size (r) was calculated as the Z-statistic divided by the square root of the sample size (N). Spearman’s rank correlation was utilised to investigate the associations between the changes in the three scores obtained from the recognition tasks and the changes in physiological data (NF signal values and LTR). For the correlation analysis, only the trials relevant to each score were selected, and their median NF signal values and median LTR values were calculated for each session. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni method, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. Furthermore, since EEG tend to exhibit larger power in lower frequencies, there is a possibility that the delta band (0.5-2Hz), which is even lower in frequency than the targeted low theta band for NF, may influence the transitions of LTR. Therefore, we investigated the transitions of the total power (0.5-32Hz), low theta power, and delta power between sessions.

To examine the frequency and temporal characteristics of neural activity during memory encoding, a time-frequency analysis was performed. The iEEG power spectrum (obtained through fast Fourier transform) and power spectrum using complex Morlet wavelets (, t: time, f: frequencies increasing logarithmically from 1 Hz to 64 Hz with 31 log-spaced steps, σ=n/2πf: bandwidth of each frequency band, n: wavelet cycle numbers increasing logarithmically from 4 to 10) were multiplied for each trial data of each electrode. Then, the inverse fast Fourier transform (convolution in the frequency domain) was applied to obtain the time-frequency representation. The squared magnitude of the convolution results was defined as the power estimate at each time point and frequency band. After that, the power estimates from the four electrodes were averaged, resulting in time-frequency features for each trial. To investigate the time-frequency characteristics related to memory encoding, trials in each session were divided into correct trials (Correct) and incorrect trials (Error) based on the accuracy of recognition task 2. Specifically, the median of each Correct/Error trial was calculated for each session. Then, the average power estimates from -600ms to -100ms before the presentation of the first word were considered as the baseline activity. Using this baseline activity, the power estimates during memory encoding were Z-transformed and normalised for each condition. By calculating the average of the Z-scores across sessions for Correct and Error trials, the time-frequency characteristics of each condition were obtained. Furthermore, the difference in time-frequency characteristics between Correct and Error trials was assessed by subtracting the Z-scores of Error trials from Correct trials for each session and calculating the average across sessions. It is worth noting that statistical comparisons were not conducted due to constraints on the number of sessions.

Similarly, the time-frequency characteristics of the two conditions (Up/Down) were compared during the two NF training stages (first/final). For each combination of condition and stage, the median values of trials, excluding trial 1 and trials contaminated with noise, were calculated. Then the average power estimates from -600ms to -100ms before the first word presentation were used as the baseline activity and underwent Z-score transformation. By the standardised, the time-frequency characteristics of each condition were obtained. The differences between the two groups (condition/stage) were statistically compared using nonparametric randomization tests. In the randomization tests, first, the time-frequency maps of each trial were shuffled between the two groups, and the test statistic t was obtained for each time-frequency pixel. By performing 1000 shuffles, the mean and standard deviation of the test statistics t for each pixel were calculated. The actual t-values were then converted to z-scores based on the mean and standard deviation from the shuffling procedure, creating a time-frequency map representing the differences between the two groups. Cluster-based multiple comparison corrections were applied to identify statistically significant spatiotemporal clusters. In this process, the maximum cluster size formed by pixels exceeding the threshold (α = 0.05) of the t-distribution in each shuffle out of 1000 shuffles was extracted to obtain the null distribution of cluster sizes. Subsequently, the threshold was set at the 95th percentile of this null distribution, and clusters of pixels exceeding this threshold were considered statistically significant as large clusters.

3. Results

System errors or significant noise contamination led to the exclusion of trials or sessions where proper NF could not be achieved. Additionally, trials in which key input was missed, resulting in an inability to confirm responses for the recognition task, and trials where effective NF was not possible were excluded during the calculation of recognition performance.

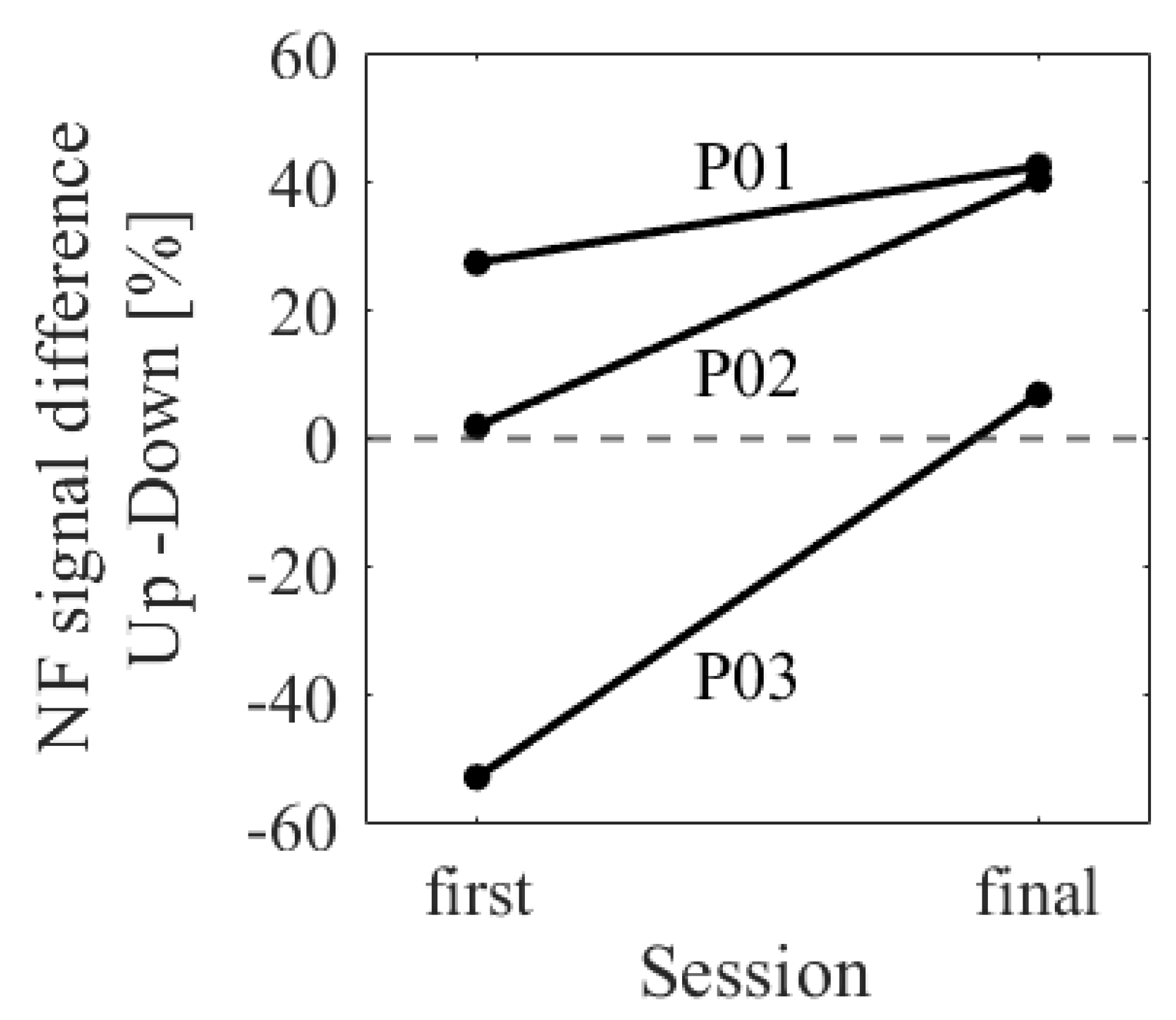

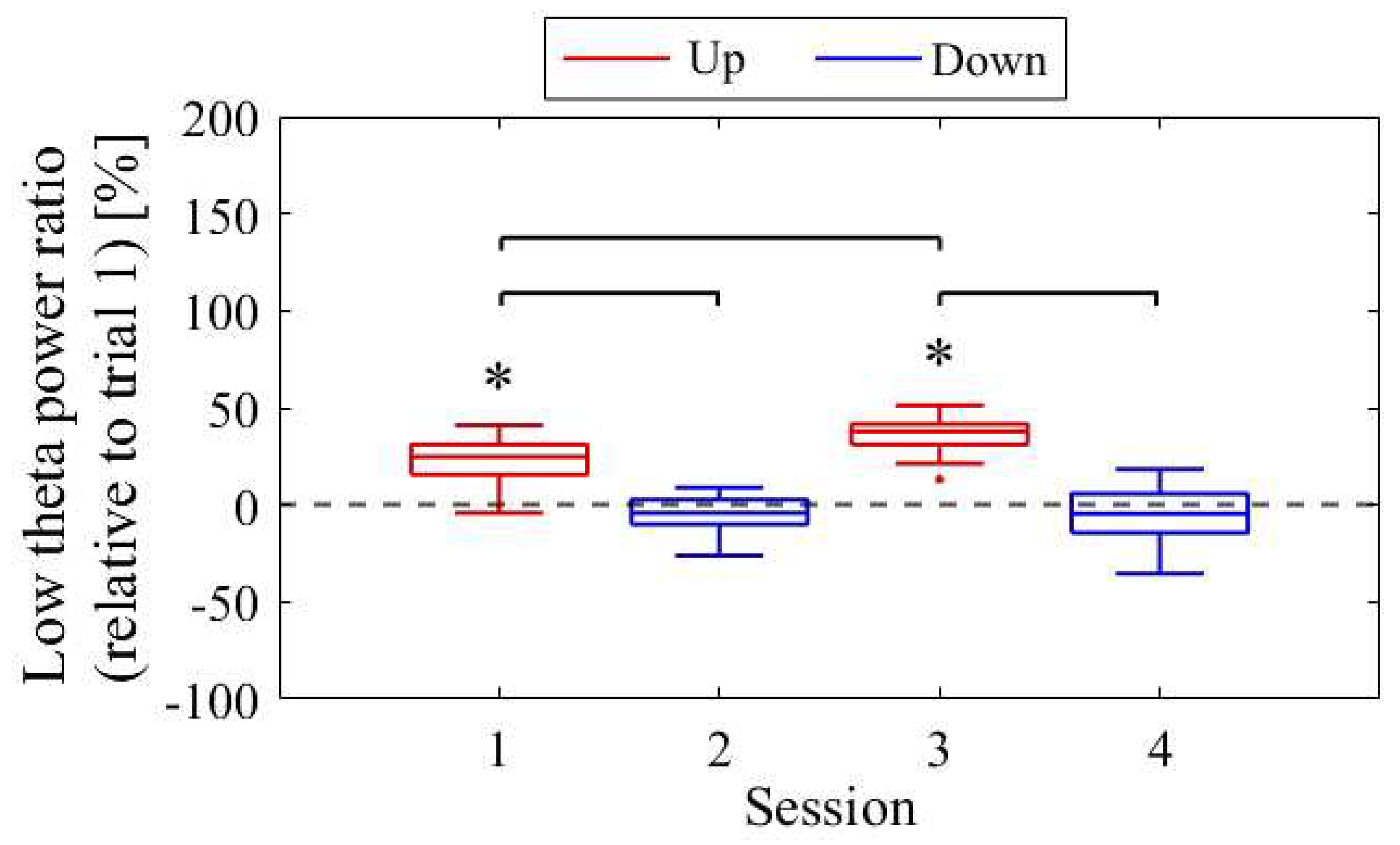

The difference in NF signal values for the Up condition relative to the Down condition (Up − Down) is shown in

Figure 3. In the first session, the NF signal difference varied among participants, ranging from positive values for P01 (27.35%) to negative values for P03 (−52.66%), with P02 having a value of 1.90%. In the final session, all participants exhibited positive NF signal differences and showed larger values compared to the first session , with P01 at 42.35%, P02 at 40.25%, and P03 at 6.82%.

The following section provides the results for each participant.

3.1. Results for P01

P01 completed four sessions of memory NF training over a span of five days. After the series of NF training, P01 underwent surgery to remove the left temporal lobe, resulting in the cessation of seizures. Post-surgery, the verbal memory Index Score on the WMS-R was below 50 and showed a decline compared to pre-surgery levels.

After the end of session 2, it was reported that in the course of trial and error in the NF, P01 adopted a strategy of randomly answering the recognition task. Although we asked P01 to avoid random responses from sessions 3 onwards, careful interpretation of the scores of the recognition task in Session 2 is necessary. There were no mentions of mental strategies from session 3 onwards. Furthermore, in session 3, due to a system error, the baseline for the NF signal was referenced not from the encoding period data of trial 1, but from a period preceding it with higher LTR values (specifically, 153.81% when LTR1 was set as 100%). Consequently, in session 3, NF was conducted under conditions that made it difficult for the red team to win. Since NF was consistent with LTR values in the MTL, it was not excluded from the analysis. However, careful interpretation of the results in session 3 is required.

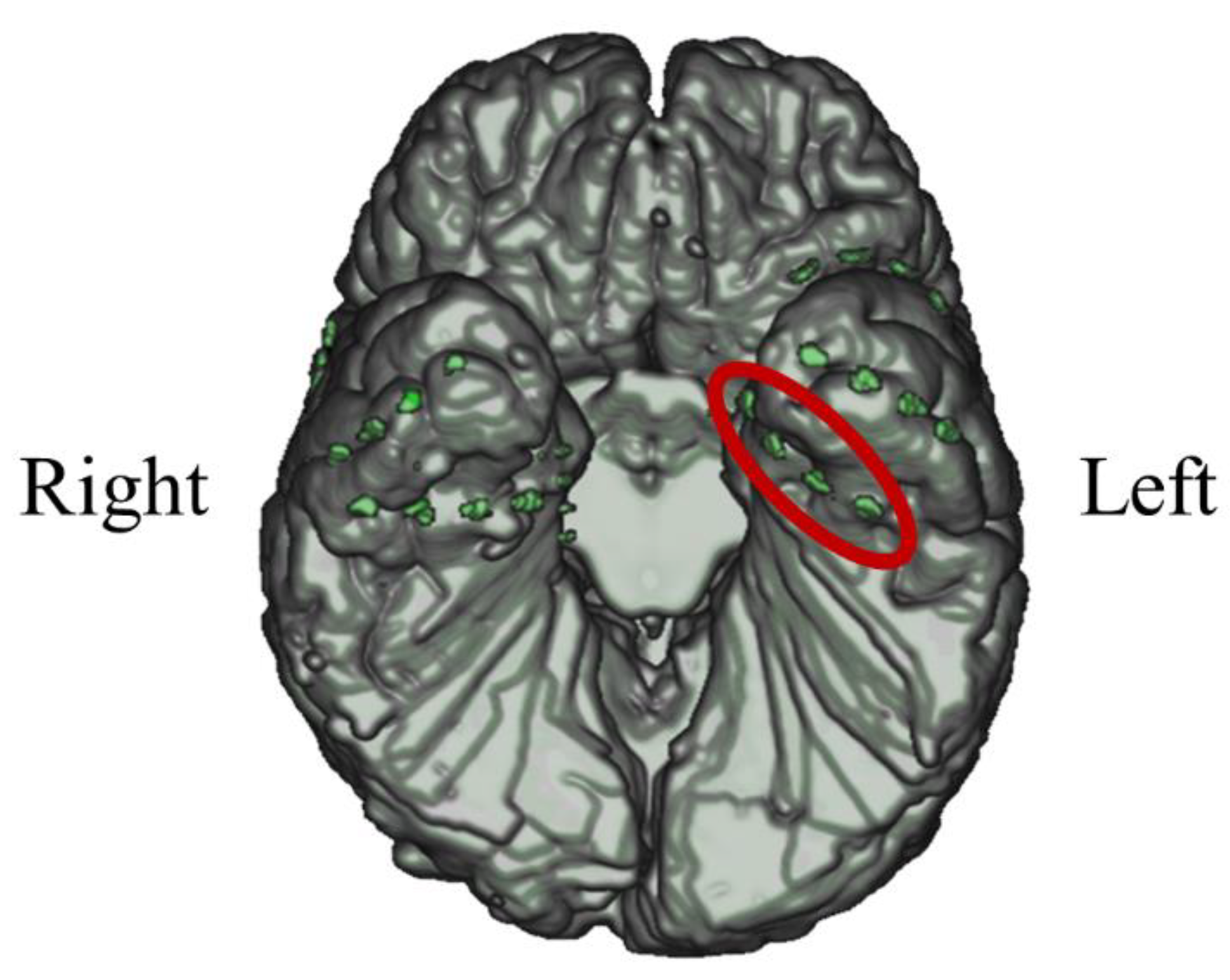

3.1.1. Intracranial Electrodes Used for Memory NF (P01)

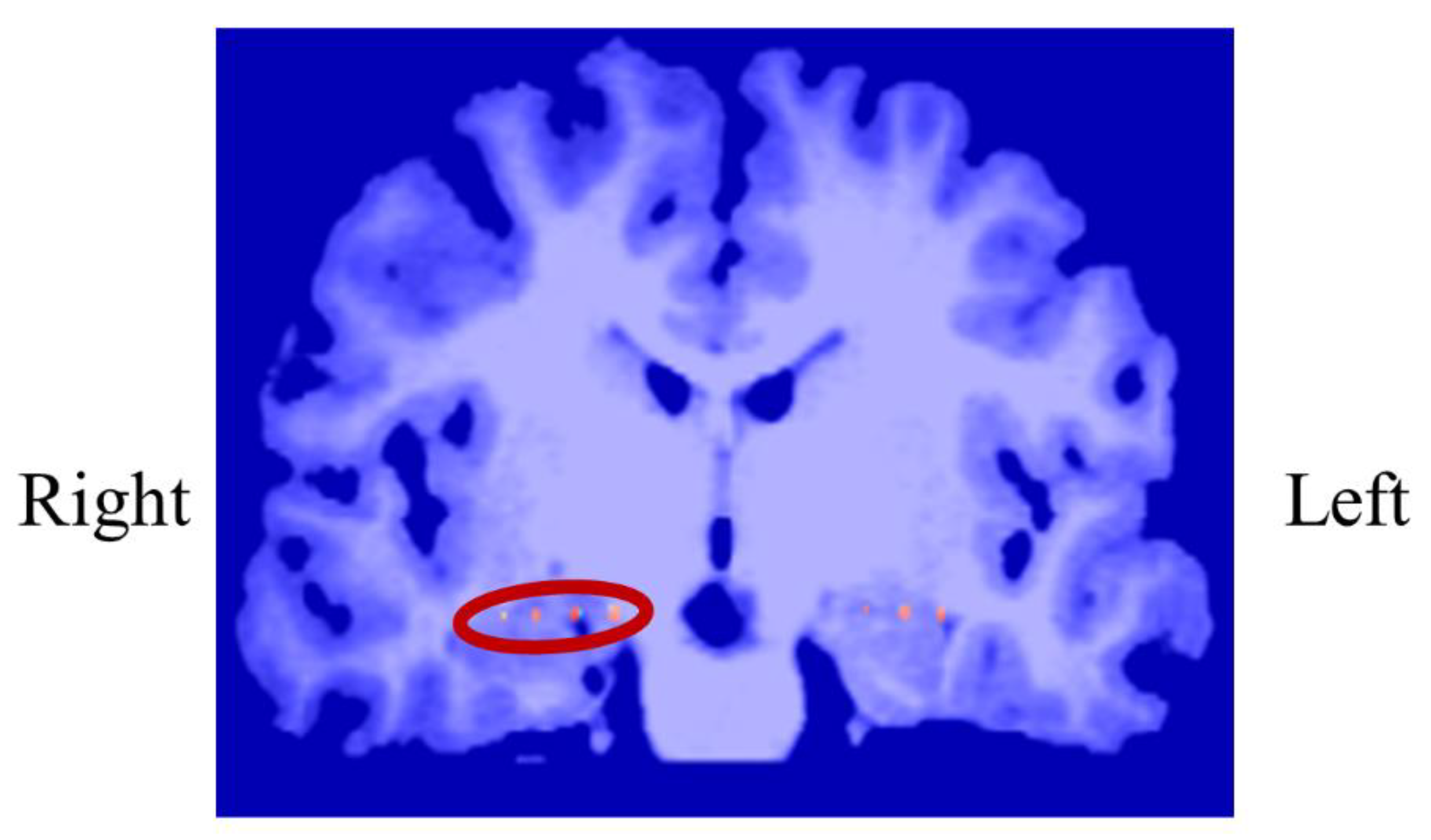

In P01, deep electrodes (Unique Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were implanted in the right MTL. The iEEG data were measured from four platinum electrodes (1mm in length), positioned at 5mm intervals (centre to centre) from the tip located in the right hippocampus, and used for NF (

Figure 4). A reference electrode was placed subcutaneously on the right side for P01.

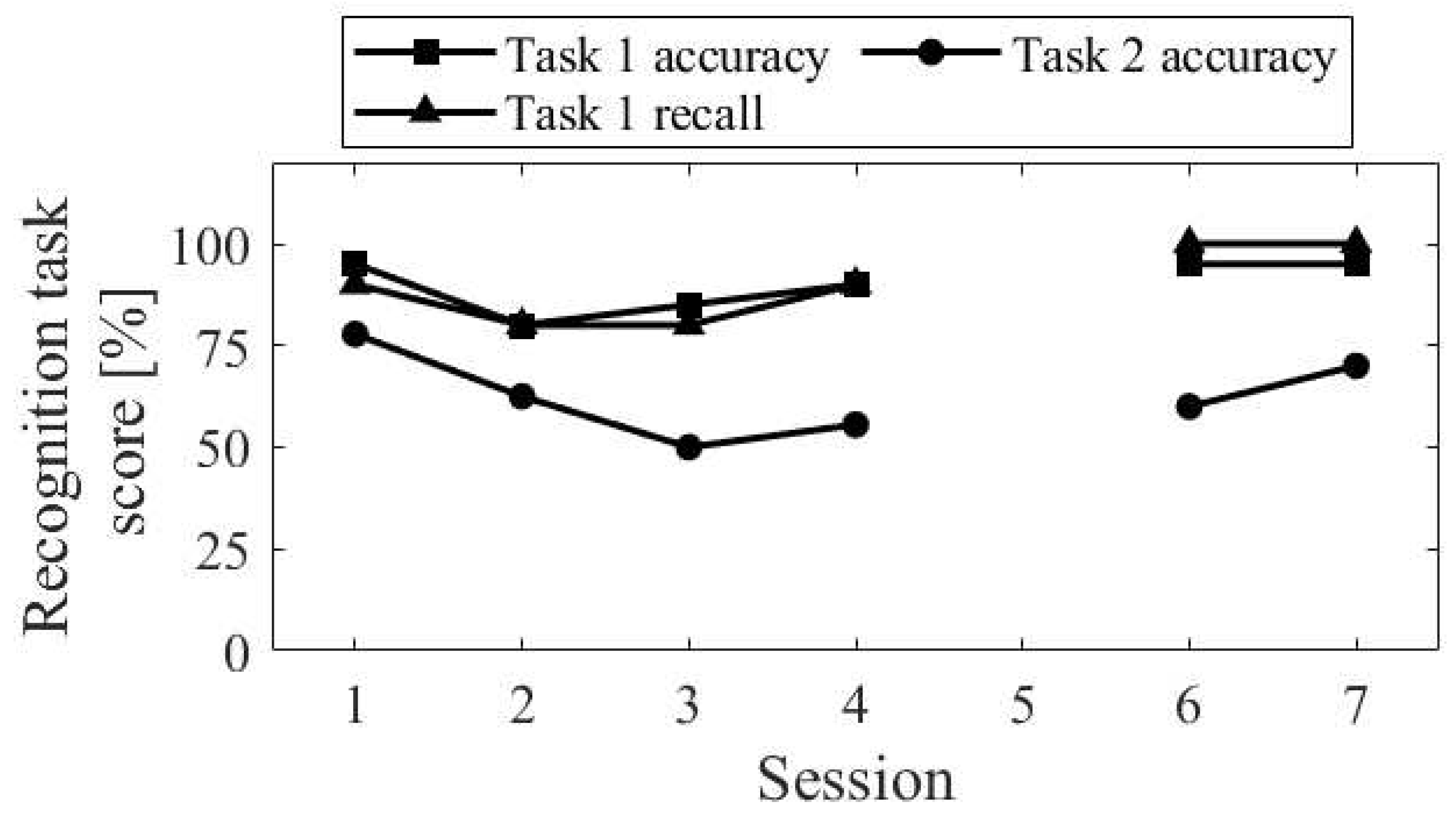

3.1.2. Performance Changes in the Recognition Task (P01)

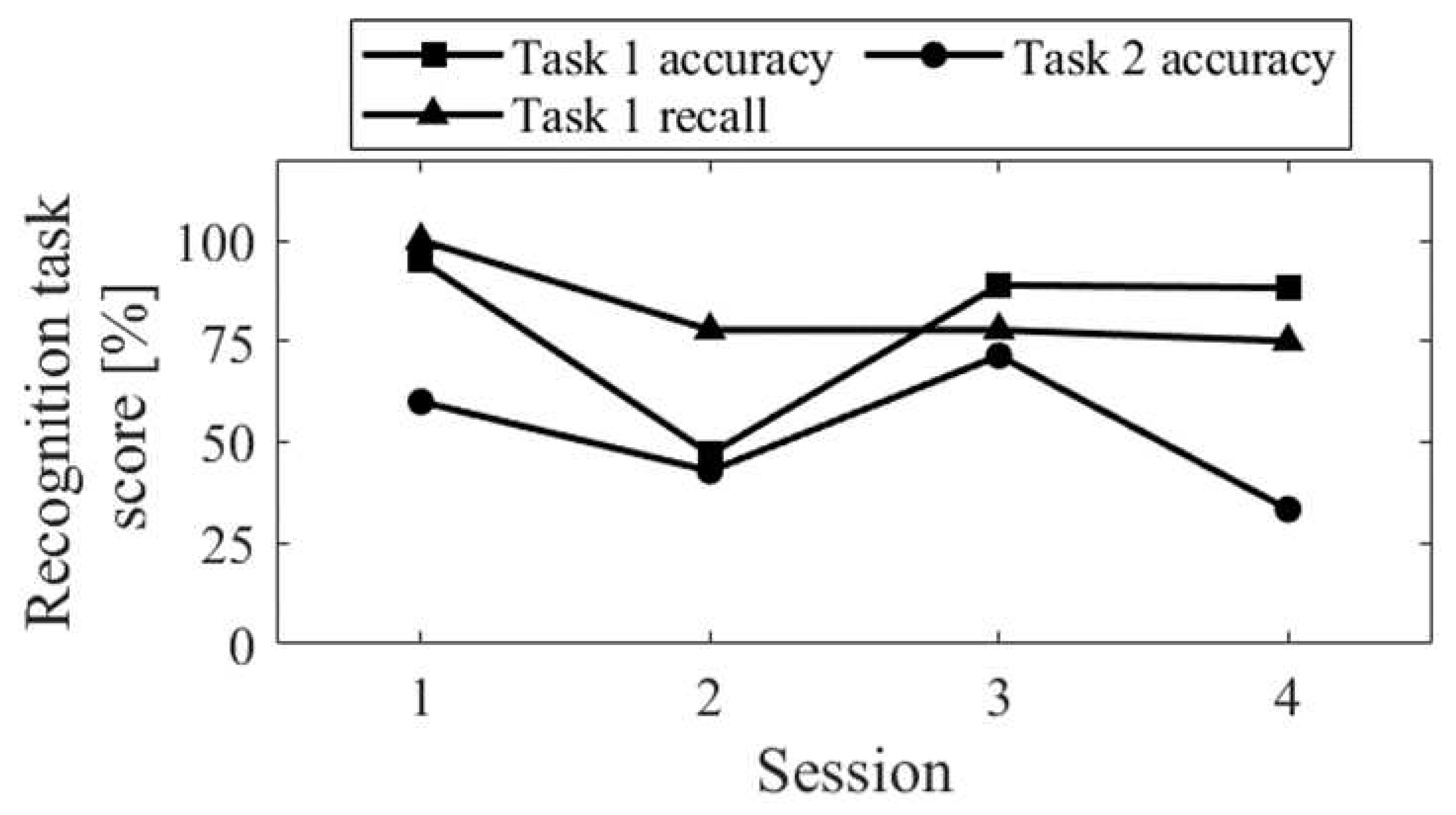

The session-to-session changes of the three scores for the recognition task are shown in

Figure 5. The accuracy of recognition task 1 significantly decreased in Session 2, where random responding occurred. The recall score was equivalent to Sessions 3 and 4. Comparing Up and Down conditions, both in the first sessions (Session 1 vs. Session 2) and final sessions (Session 3 vs. Session 4), the accuracy of recognition task 2 was higher for Up than for Down, and the difference increased in the final sessions.

3.1.3. NF Signal Changes across Sessions (P01)

The session-to-session changes in the NF signal values (LTR

i/1) are presented in

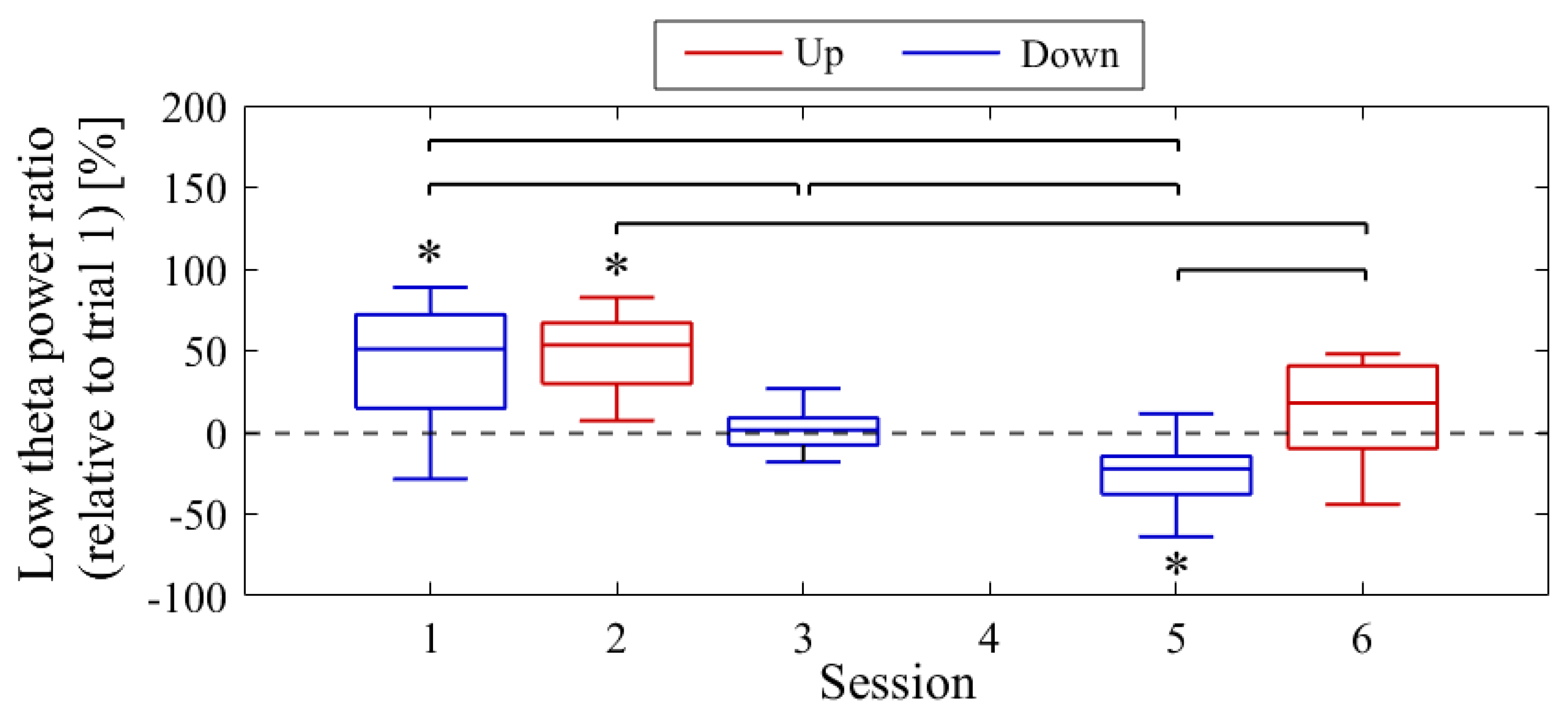

Figure 6. The NF signal values were significantly higher for Up in Session 1 (

Mdn = 124.81,

n = 19,

z = 4.118,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.945) and Session 3 (

Mdn = 137.81,

n = 18,

z = 4.475,

p < 0.001,

r = 1.055) compared to the baseline (LTR

1/1), with large effect sizes. However, there were no significant changes in the Down condition in Session 2 (

Mdn = 95.82,

n = 18,

z = −1.835,

p = 0.067,

r = 0.432) and Session 4 (

Mdn = 95.45,

n = 16,

z = −1.197,

p = 0.231,

r = 0.299) compared to the reference. When comparing Up and Down conditions for the same session number, both the first session (

z = 4.467,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.734) and second session (

z = 4.934,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.846) showed significantly higher values for Up than for Down, with large effect sizes. In the Up condition, the NF signal values significantly increased with each session, showing a large effect size (

z = 3.312,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.545). However, there were no significant changes between sessions in the Down condition (

z = 0.035,

p = 0.986,

r = 0.06).

The similarity between the performance changes in recognition task 2 and the NF signal changes was observed. However, the results of the statistical analysis showed no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the NF signal values for the recognition task 1 accuracy (r = 0.80, p = 0.33), recognition task 1 recall (r = 0.63, p = 0.37), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = 1.00, p = 0.08). Furthermore, there were no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the LTR values for the recognition task 1 accuracy (r = 0.00, p = 1.00), recognition task 1 recall (r = 0.32, p = 0.68), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = 0.80, p = 0.33).

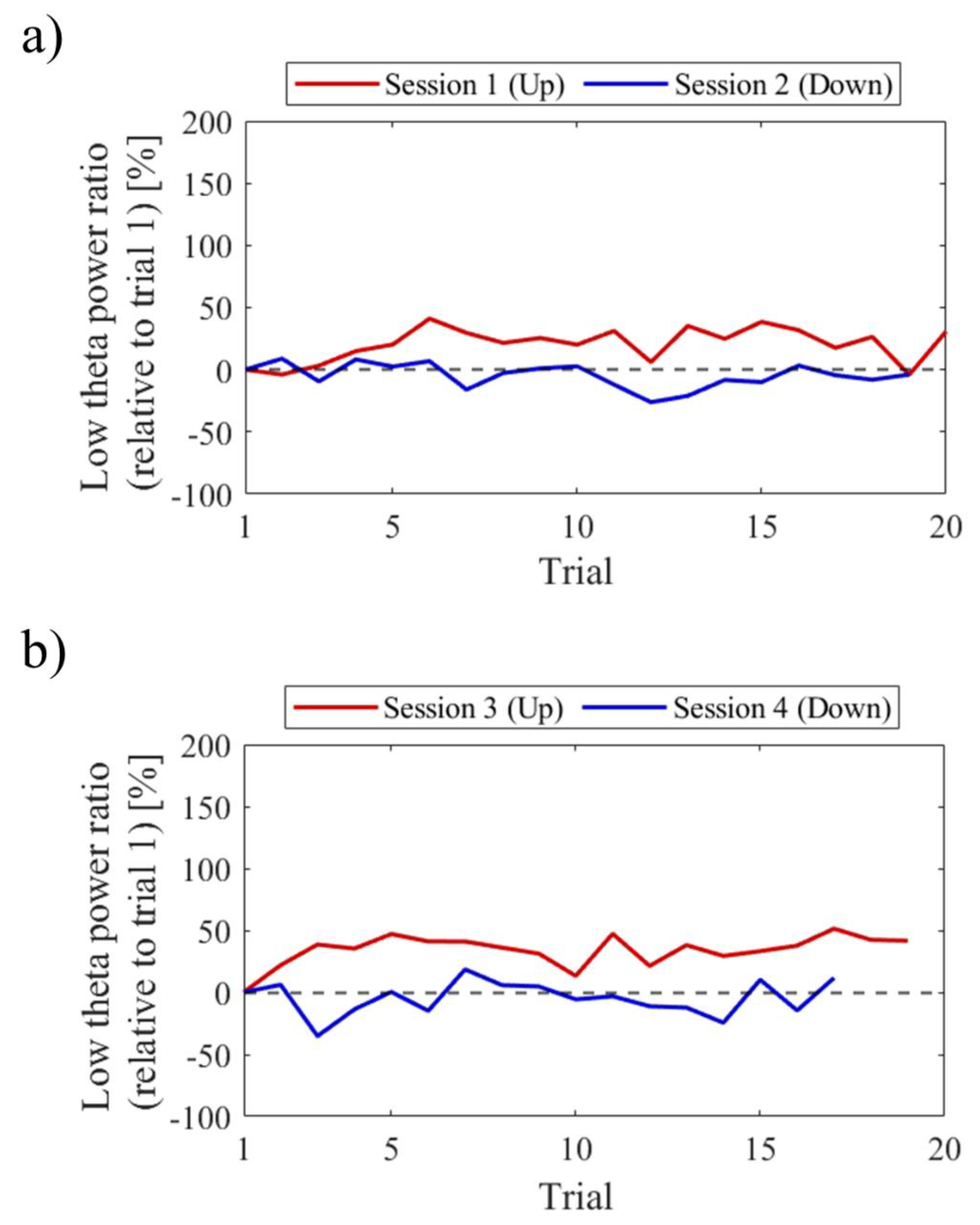

3.1.4. NF Signal Transition within Sessions (P01)

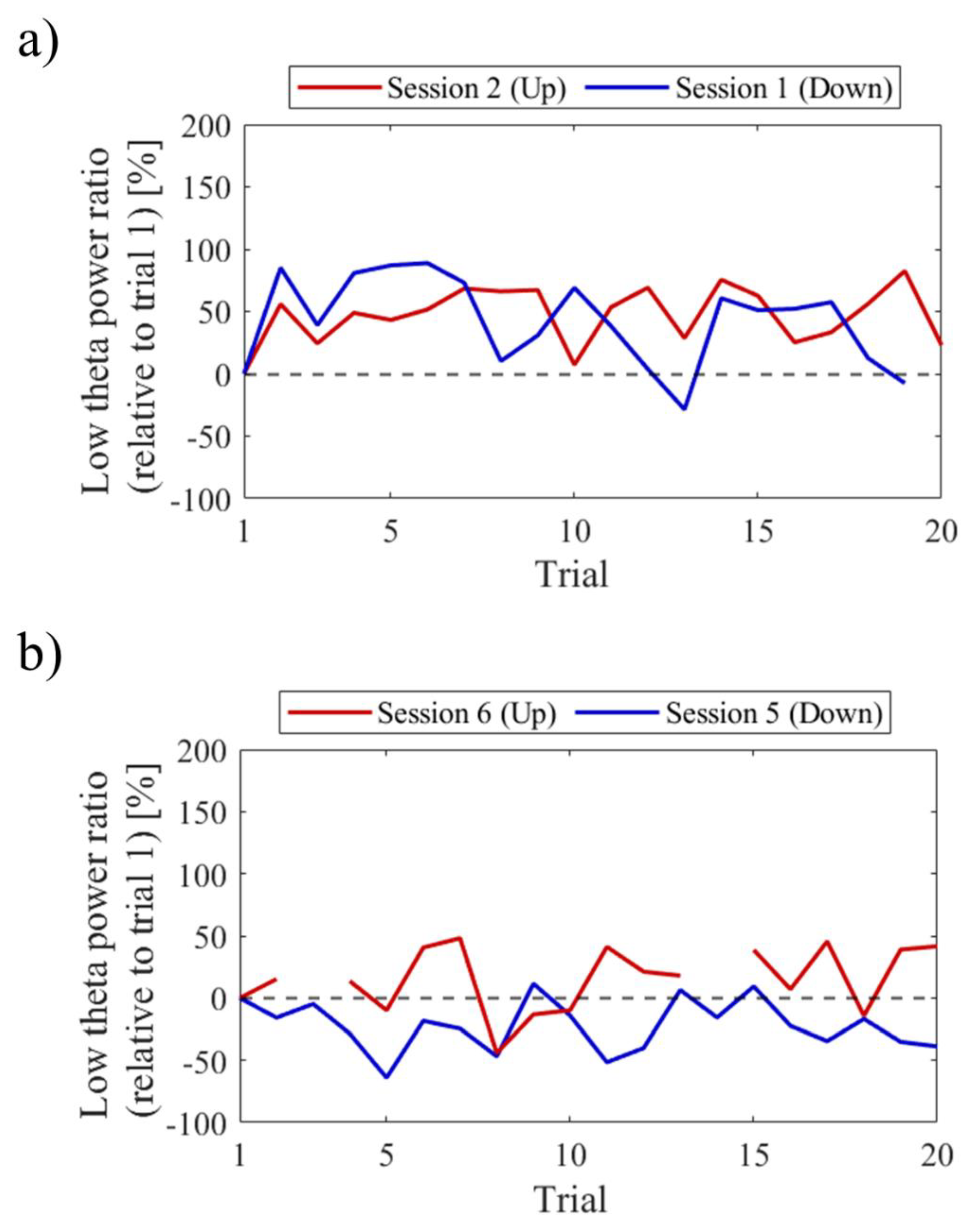

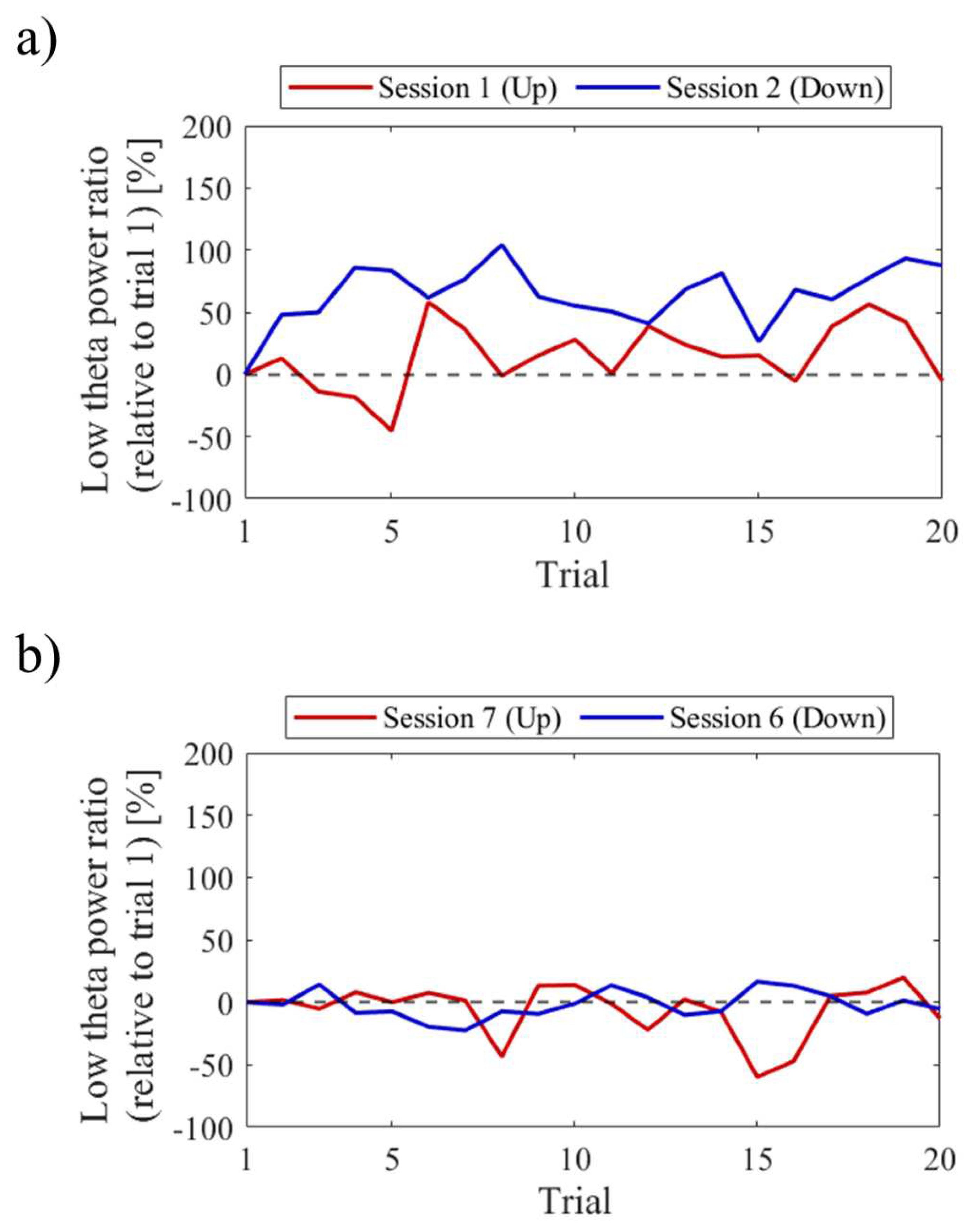

Regarding the first and final sessions, we compared the within-session transitions of NF signal values between Up and Down conditions (

Figure 7). Both in the first and final sessions, the NF signal values exhibited higher overall trends in the Up condition compared to the Down condition across trials. Additionally, in the Up condition, there was a steeper rise in NF signal values from trial 1 during the final session compared to the first session.

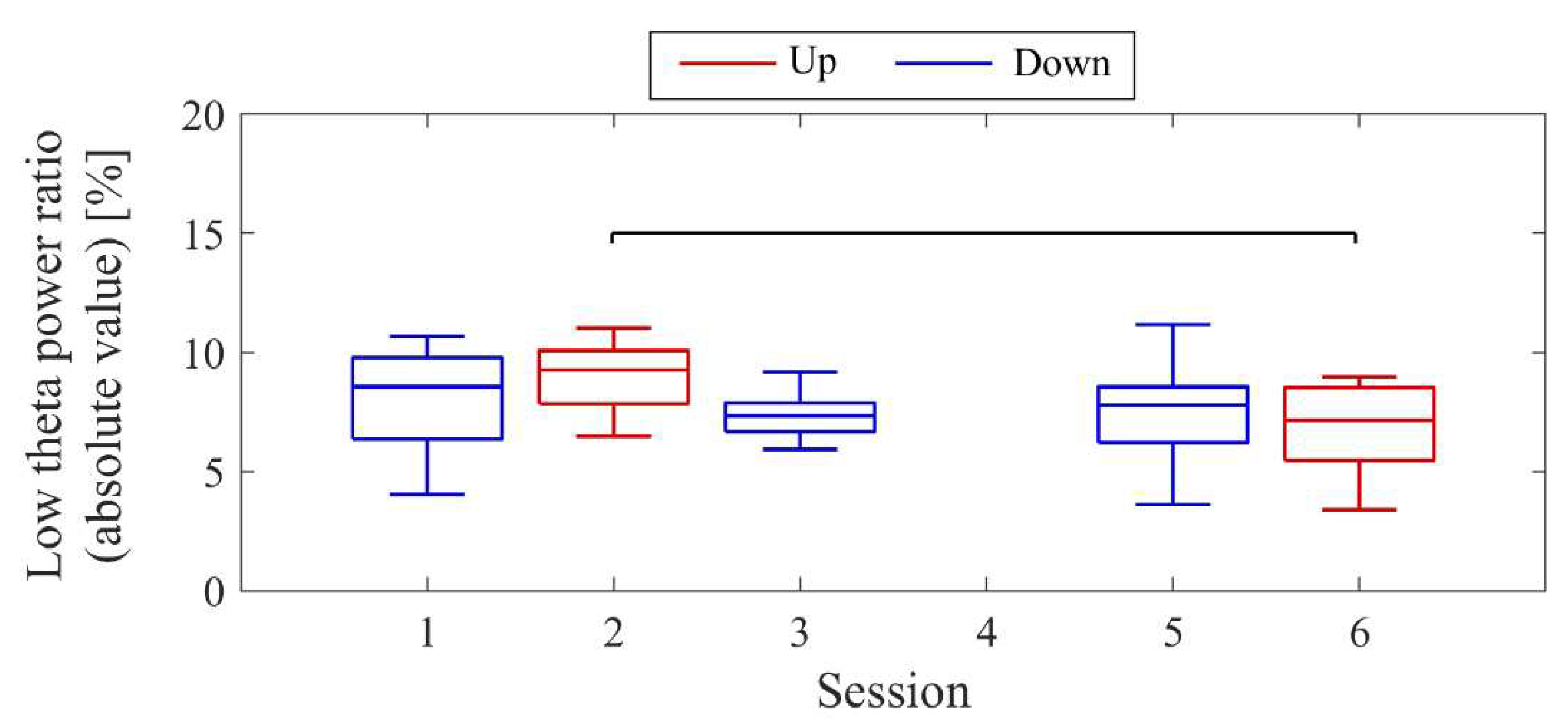

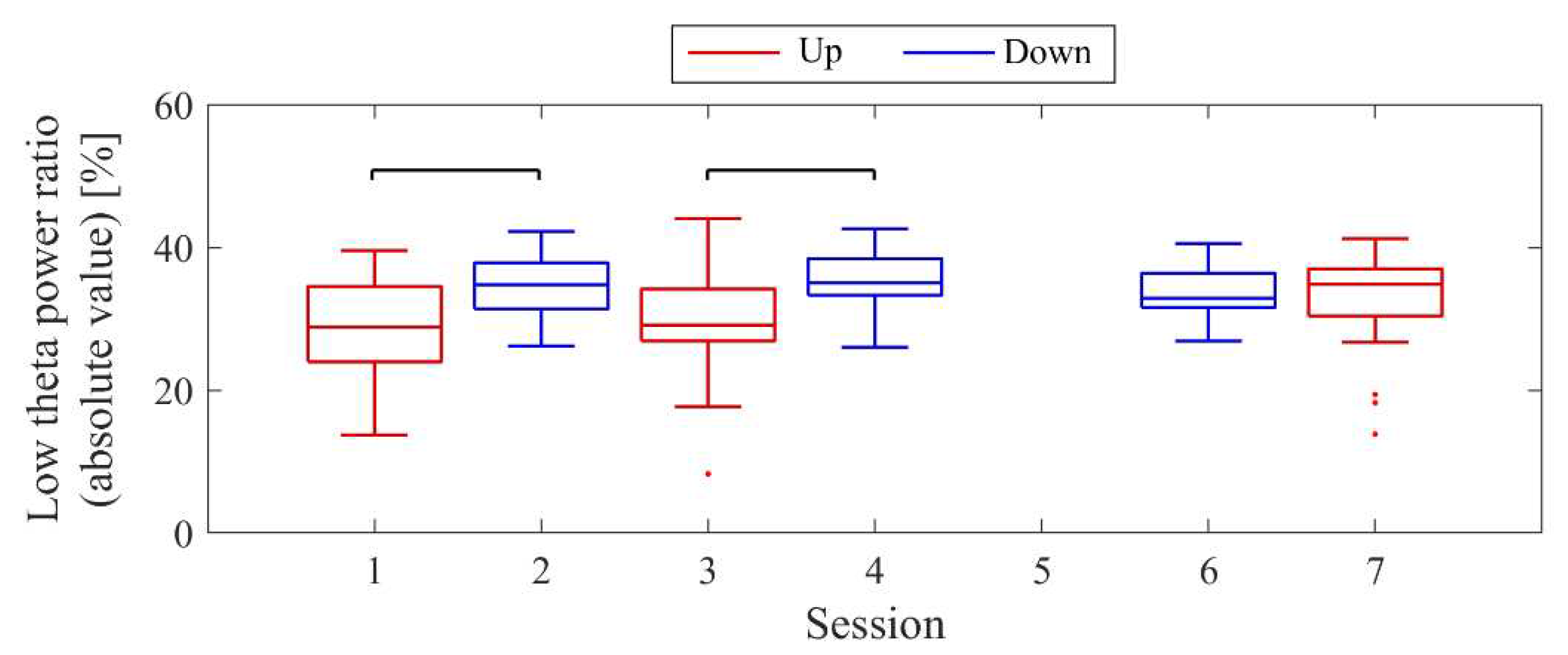

3.1.5. Low Theta Power Ratio (LTR) Changes across Sessions (P01)

The LTR

1, which served as the baseline, showed approximately a 10% difference across conditions: 33.7% in Session 1, 43.4% in Session 2, 32.8% in Session 3, and 41.6% in Session 4. A comparison between conditions was performed for the LTR

i values from Trial 2 onwards, similar to the NF signal analysis (

Figure 8). When comparing Up and Down conditions for the same session number, there were no significant differences in the first session (

z = −0.091,

p = 0.940,

r = 0.015). However, in the second session, Up showed significantly higher values than Down, with a moderate effect size (

z = 2.691,

p = 0.006,

r = 0.462). In the Up condition, the LTR

i values significantly increased with each session, showing a moderate effect size (

z = −2.553,

p = 0.01,

r = 0.419). However, there were no significant changes between sessions in the Down condition (

z = 0.897,

p = 0.384,

r = 0.154).

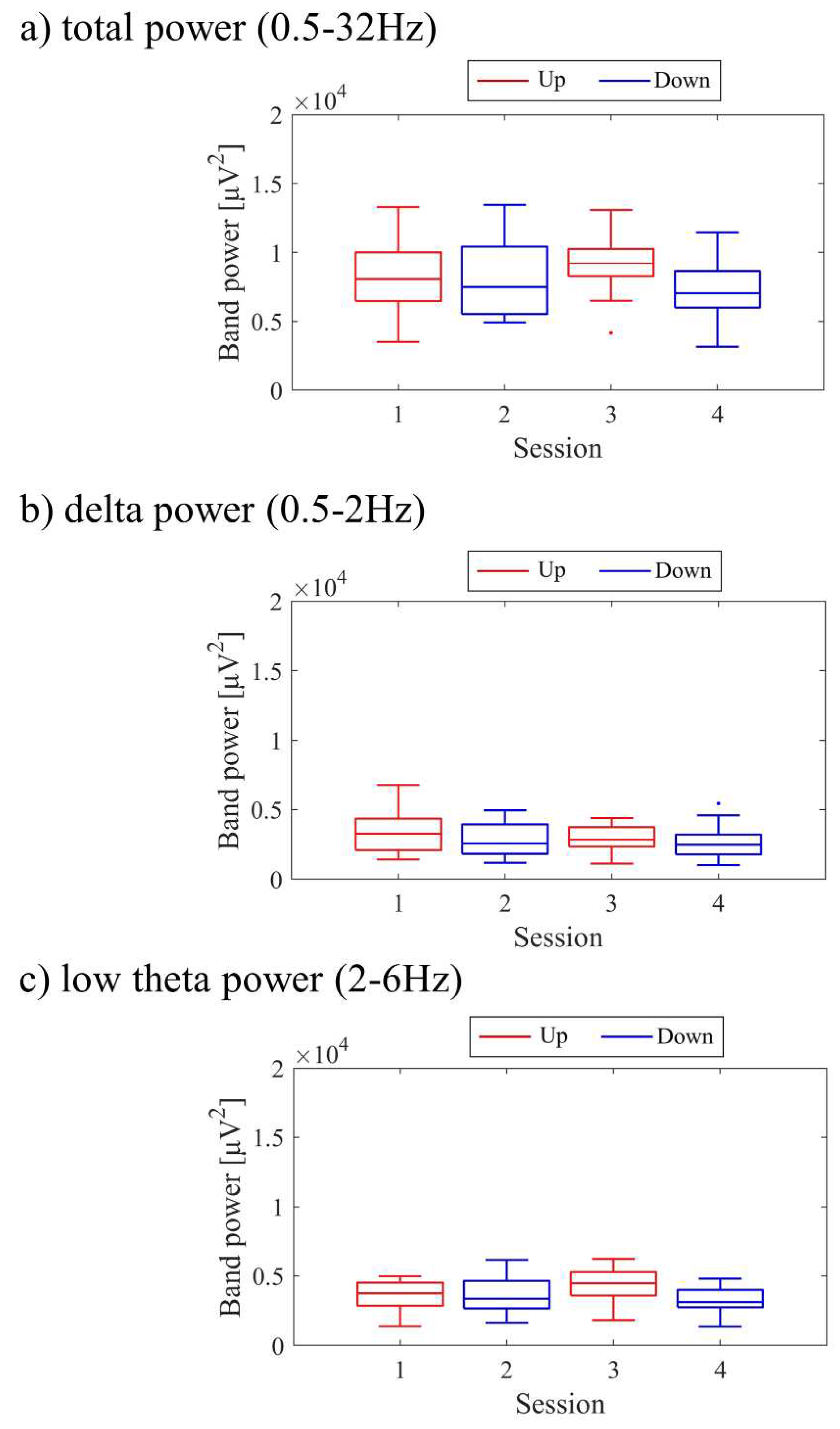

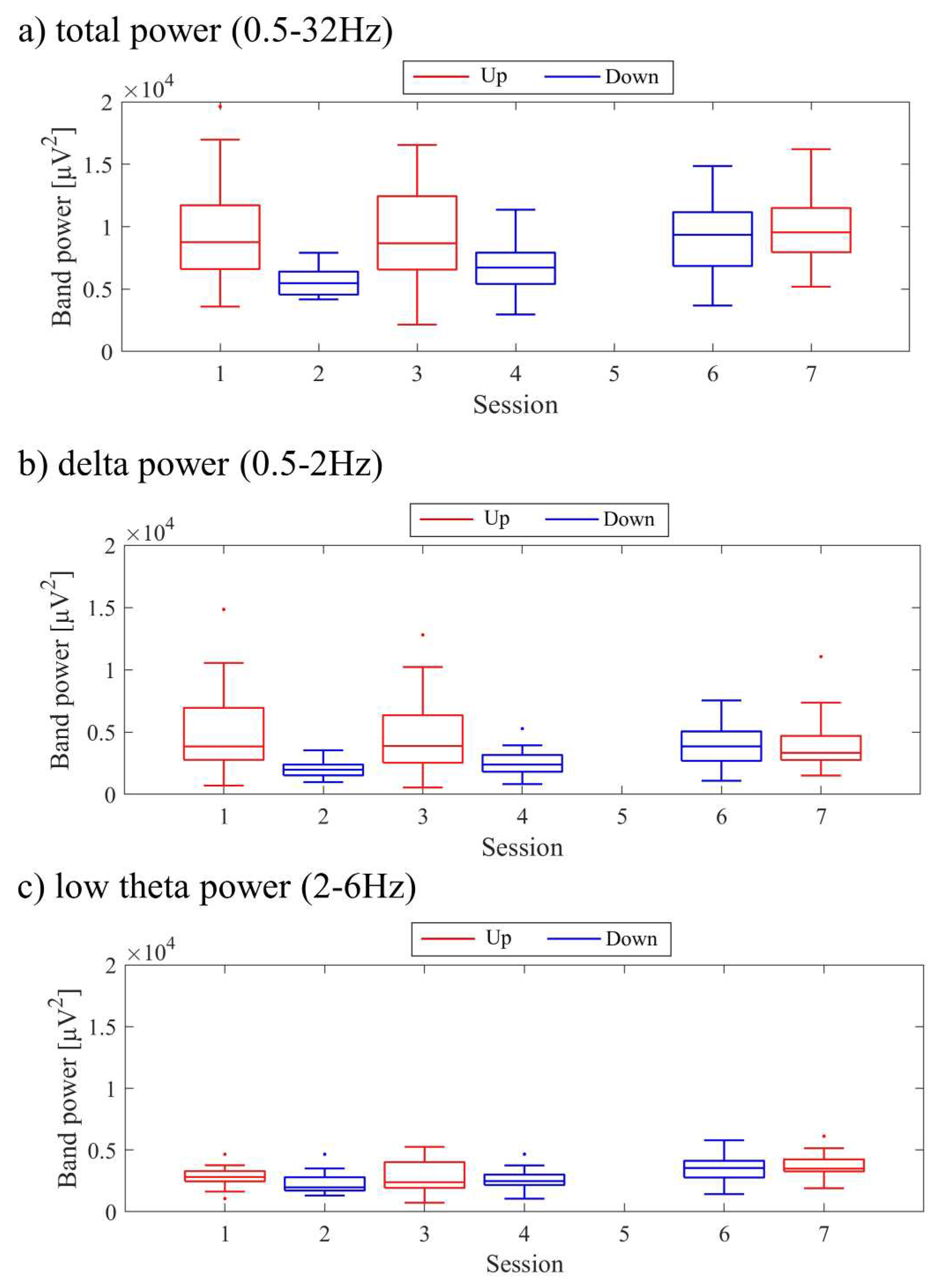

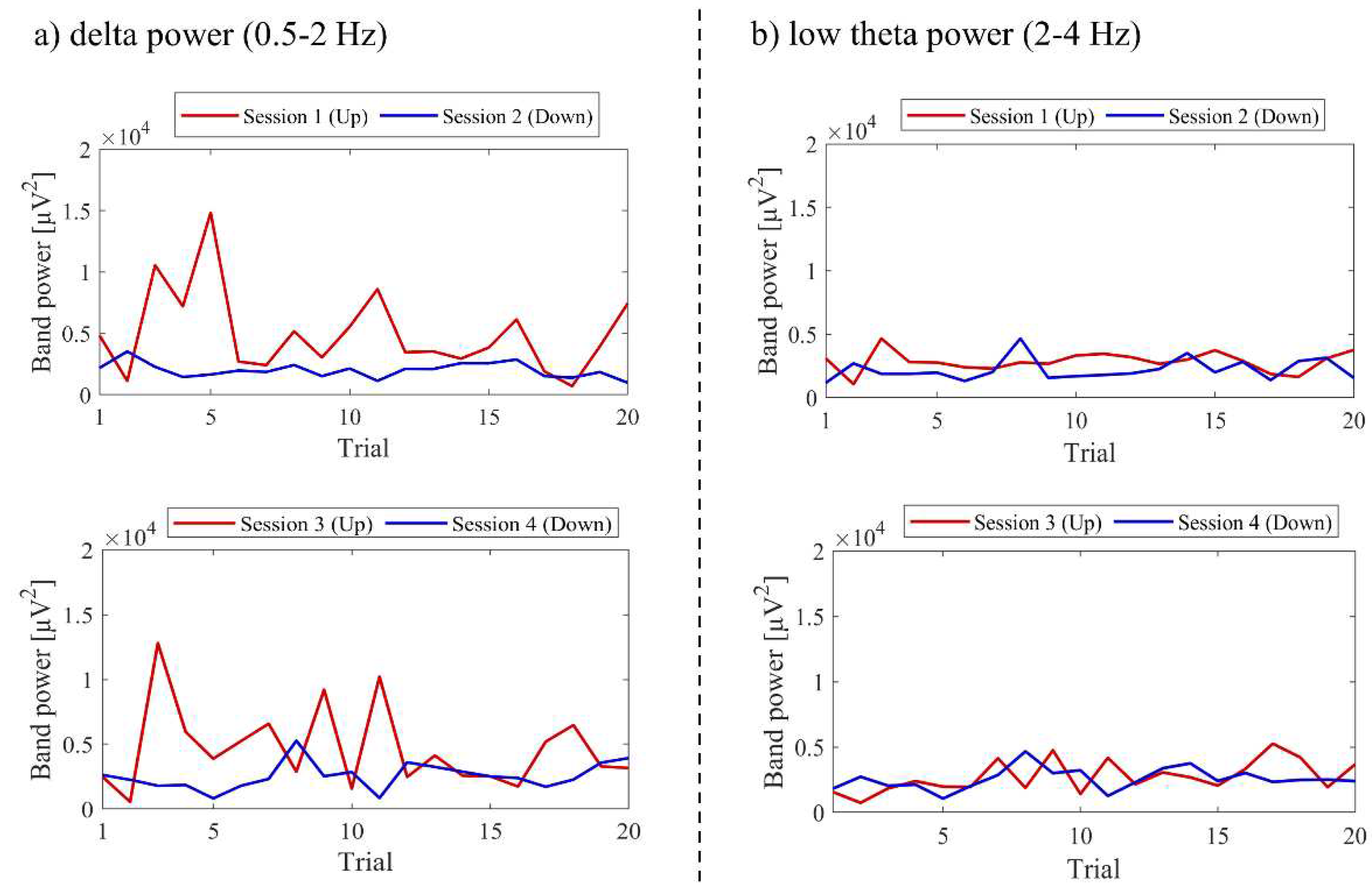

3.1.6. Frequency Band Power Changes across Sessions (P01)

The transitions between sessions of total power, delta power, and low theta power are presented in

Figure 9. Both delta power and low theta power had similar median magnitudes. All frequency band powers showed a trend of higher median values in the Up condition compared to the Down condition. The patterns of total power and low theta power changes exhibited similarities to the NF signal changes and the performance changes in recognition task 2.

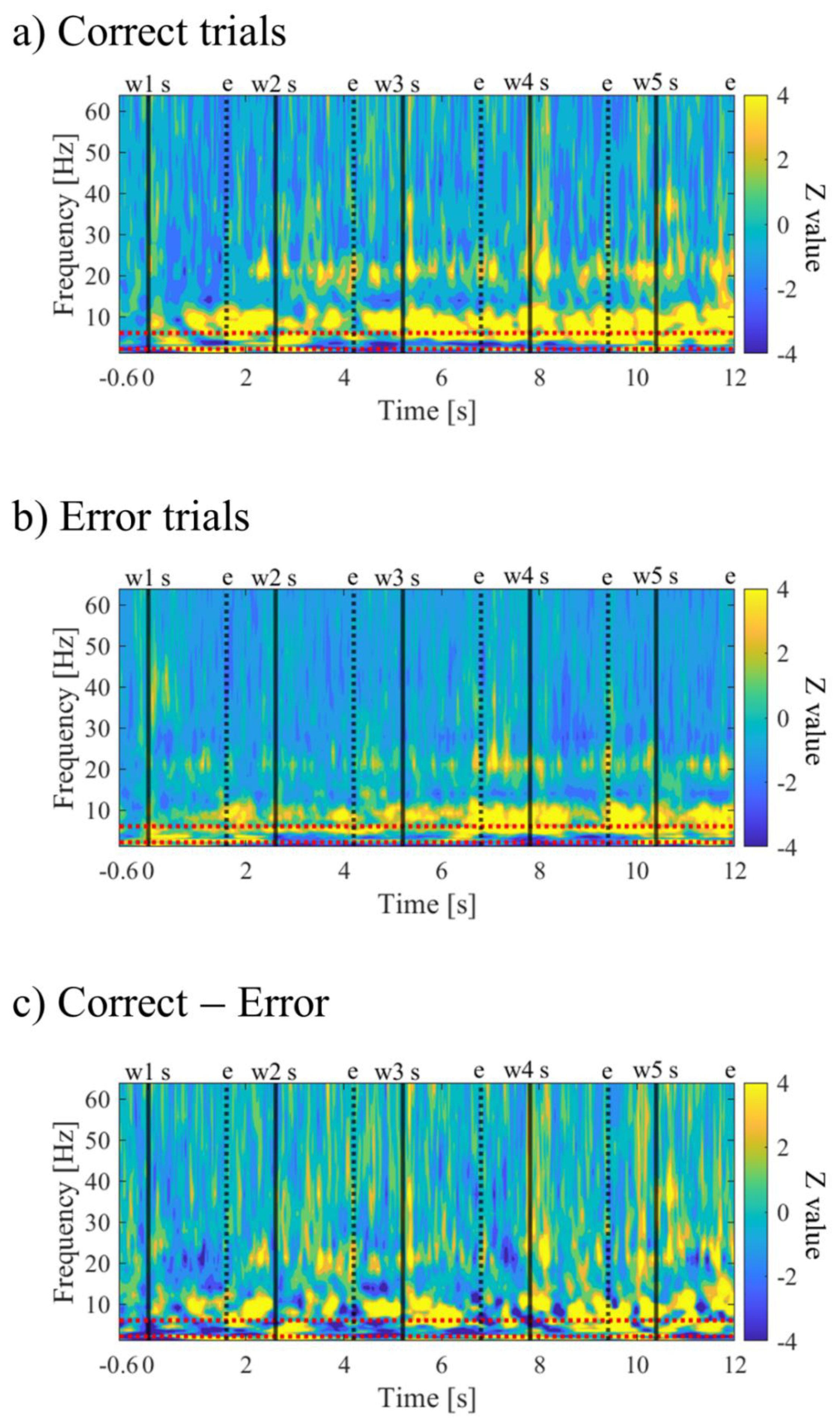

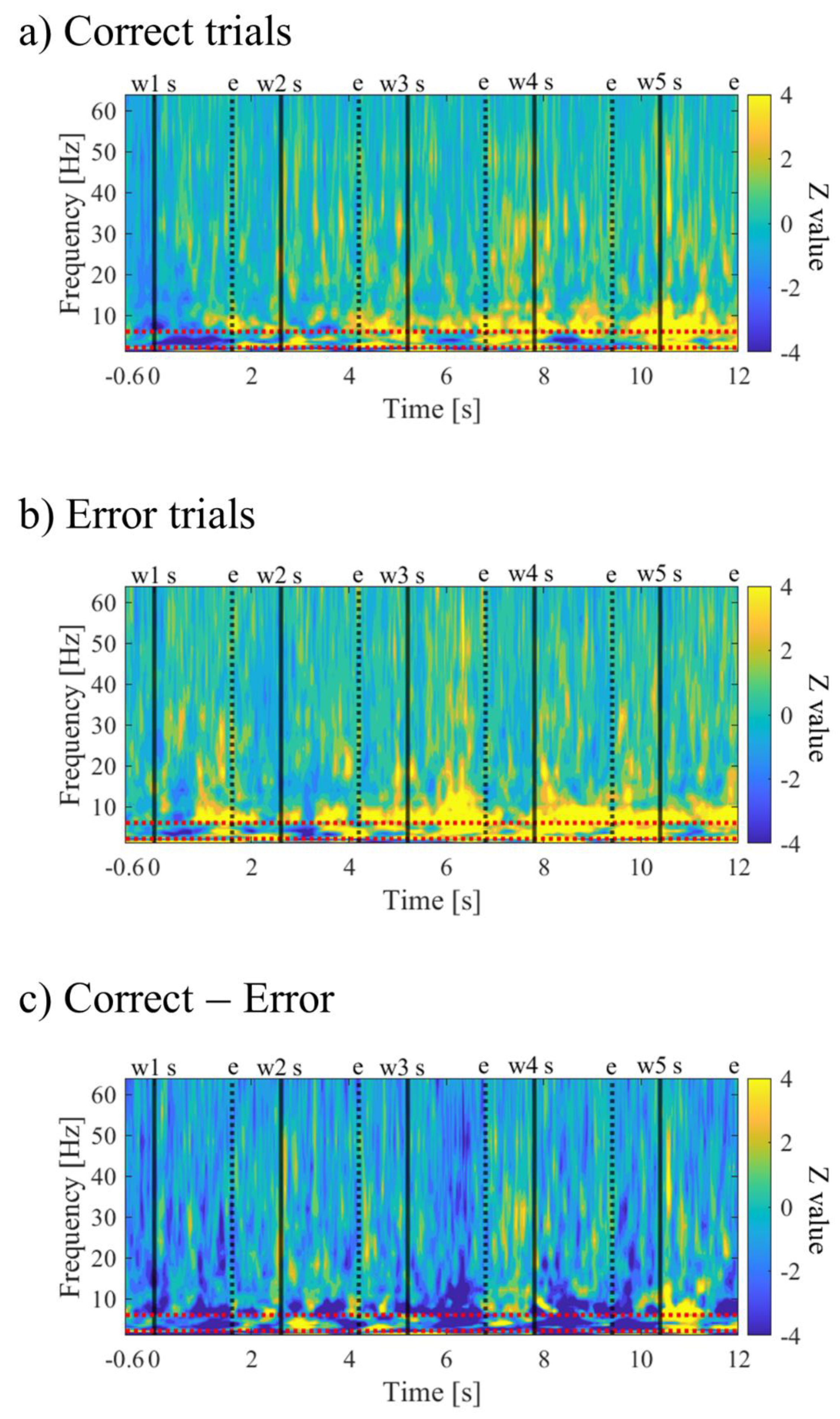

3.1.7. Time-Frequency Maps for Correct and Error Trials (P01)

The time-frequency maps for Correct and Error trials are shown in

Figure 10a,b. Both maps exhibited intermittent power increases in the theta and alpha bands. When comparing Correct to Error trials, it was observed that during the mid-phase of the encoding period, the low theta band power increased before stimulus presentation and decreased during stimulus presentation (

Figure 10c).

3.1.8. Time-Frequency Maps for Up/Down and First/Final Sessions (P01)

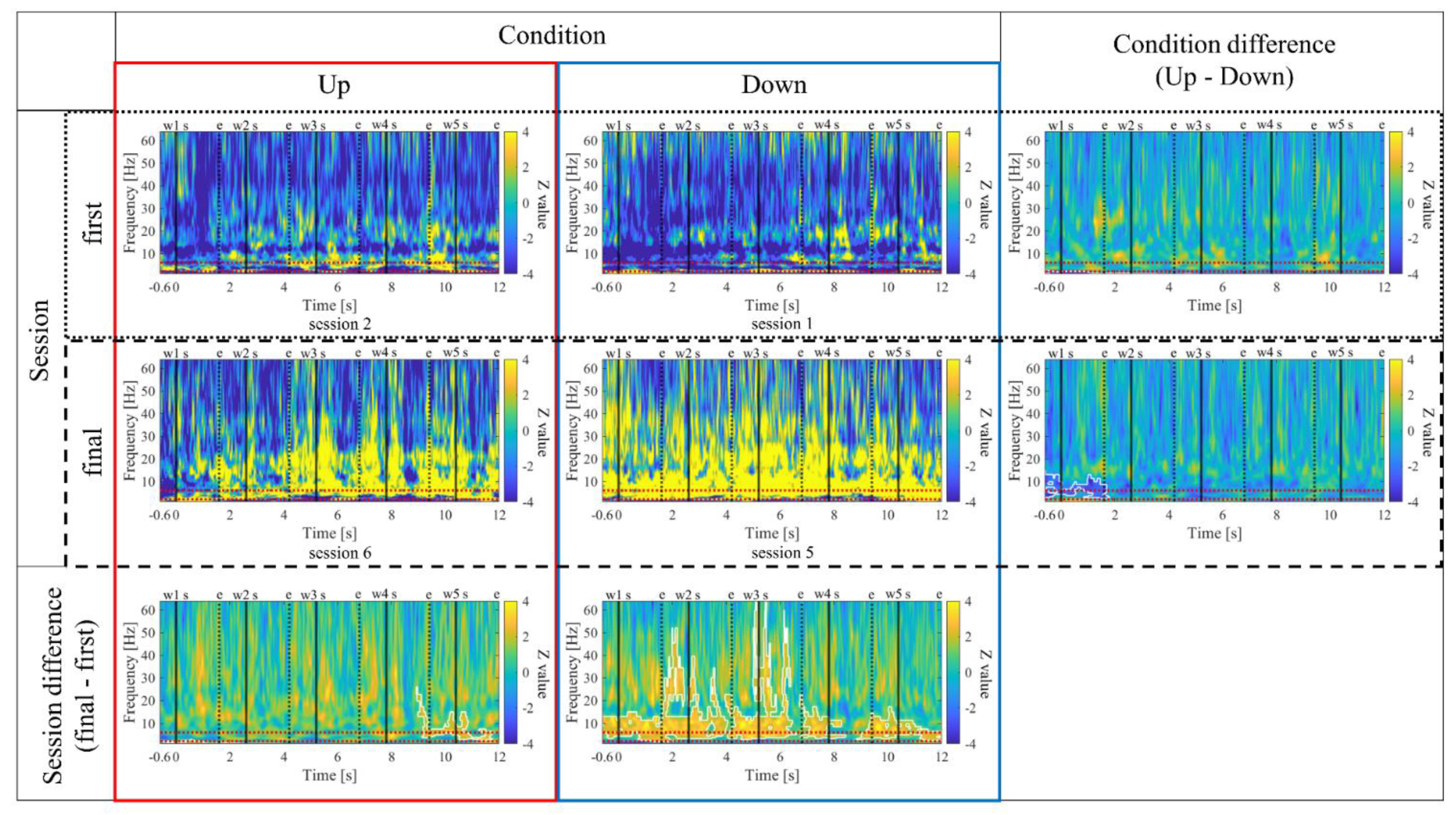

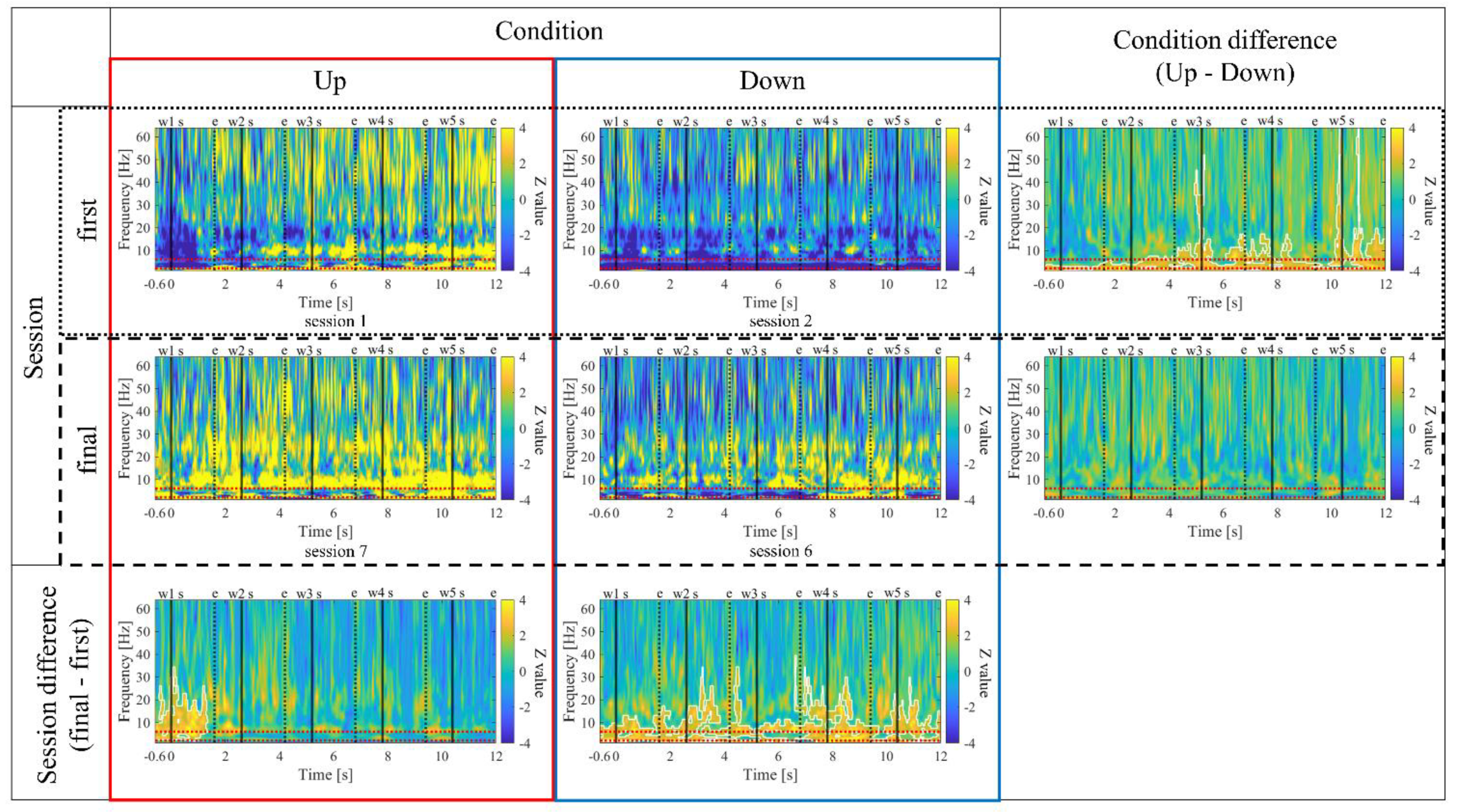

The time-frequency maps for the Up and Down conditions, as well as the first and final sessions, along with the difference maps between sessions, are presented in

Figure 11. In comparison between the Up and Down conditions, in both the first and final sessions, sustained power increases in the gamma band were observed for the Up condition compared to the Down condition. Additionally, intermittent power increases in the alpha and beta bands during the middle of the encoding period were observed for the Down condition in the first sessions. However, in the final sessions, the Up condition exhibited more consistent power increases from the low theta to beta bands. When comparing the first and final sessions, power increases in the Up condition and power decreases in the Down condition from the low theta to beta bands were observed during the middle of the encoding period. Furthermore, in the Up condition, a significantly large cluster indicating a decrease in delta band power at the end of the encoding period was observed for the final session compared to the first session.

3.2. Results for P02

P02 completed six sessions of memory NF training over a span of five days. After the series of NF training, P02 did not undergo surgery; therefore, the WMS-R assessment was not conducted post-surgery.

During sessions 1 and 2, it was reported that P02 was occupied with memorising the words. After sessions 5 and 6, reports indicated that the white team tended to win when P02 remembered the words with relaxation without concentrating too much. In contrast, when P02 concentrated hard to memorise, the red team seemed to win. Regarding session 4, it was observed that artificial noise with high amplitude was mixed during trial 1, making it difficult to adjust noise reduction using ASR. Since the NF signal values used trial 1’s LTR as the baseline, session 4 was excluded from the analysis, and any trials with confirmed artificial noise contamination were also excluded.

3.2.1. Intracranial Electrodes Used for Memory NF (P02)

In P02, subdural electrodes (Unique Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were implanted in the left MTL, covering the hippocampus. Four platinum electrodes (1.5mm in diameter) were longitudinally placed at 5mm intervals (centre to centre) along the left parahippocampal gyrus, and iEEG was measured and used for NF (

Figure 12). A reference electrode placed on the dural side of the right temporal lobe was used for P02.

3.2.2. Performance Changes in the Recognition Task (P02)

The session-to-session changes of the three scores for the recognition task are shown in

Figure 13. The recall score for recognition task 1 slightly decreased from session 1 to 2, but all aspects of the task showed improvement from session 1 to 3 and a decline from session 5 to 6.

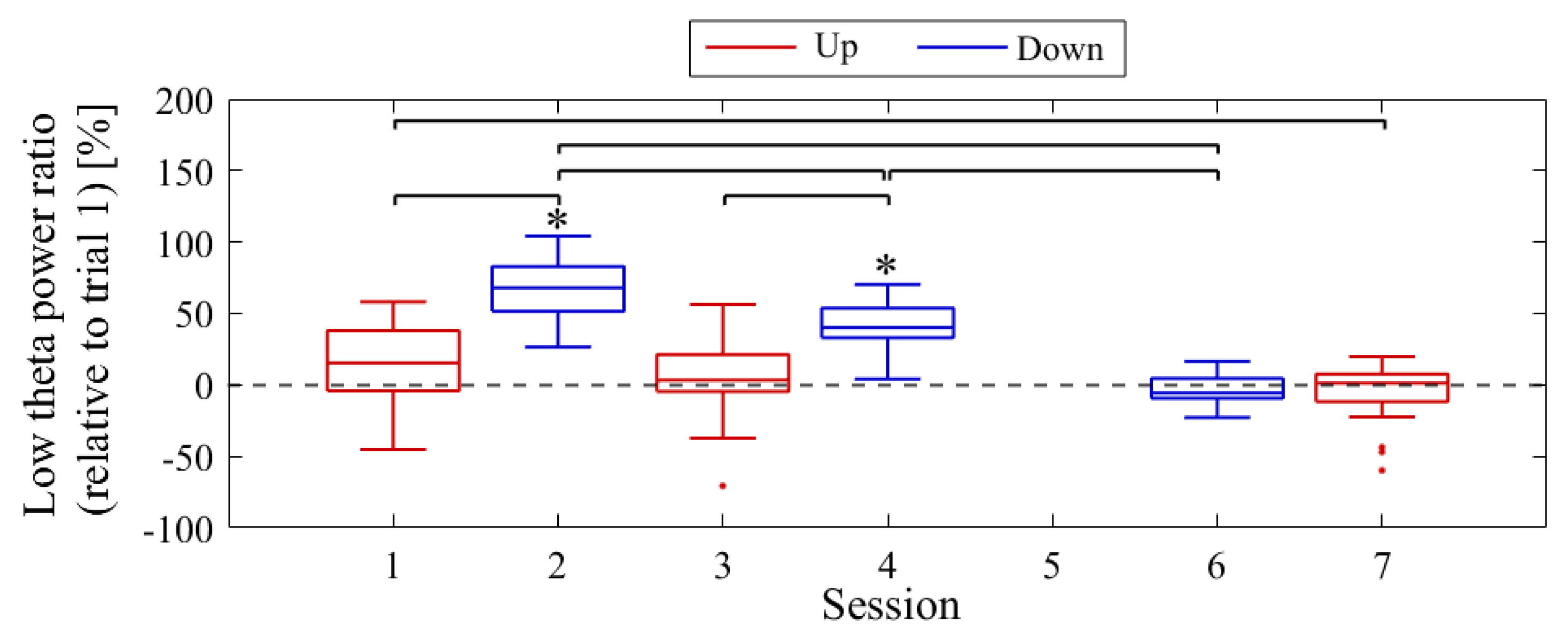

3.2.3. NF Signal Changes across Sessions (P02)

The session-to-session changes in NF signal values (LTR

i/1) are presented in

Figure 14. The NF signal values were significantly higher for Up in session 2 (

Mdn = 153.49, n = 19,

z = 4.621,

p < 0.001,

r = 1.060) compared to the baseline (LTR

1/1) with a large effect size. However, in session 6, the NF signal values for Up were not significantly higher (

Mdn = 117.91, n = 17,

z = 2.216,

p = 0.027,

r = 0.538). For Down, the NF signal values were significantly higher in session 1 (

Mdn = 151.58, n = 18,

z = 3.800,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.896) compared to the baseline, with a large effect size. In session 3, there were no significant changes (

Mdn = 101.37, n = 19,

z = 0.00,

p = 1.00,

r = 0.00), while in session 5, the NF signal values were significantly lower compared to the baseline, with a large effect size (

Mdn = 77.65, n = 19,

z = −3.834,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.880). When comparing Up and Down conditions for the same session number, there were no significant differences in the first session (

z = 0.091,

p = 0.940,

r = 0.015). However, in the final session, Up showed significantly higher values than Down, with a large effect size (

z = 4.009,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.668). It is noteworthy that in the Up condition, there was a significant decrease in NF signal values as sessions progressed, with a large effect size (

z = 3.565,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.594). In the Down condition, NF signal values decreased significantly as sessions progressed, with a large effect size (session 1 > session 3,

z = 3.829,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.629; session 1 > session 5,

z = 4.619,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.759; session 3 > session 5,

z = 3.547,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.575).

Negative correlations were observed between the performance changes in the recognition task and the NF signal changes. However, the statistical analysis revealed no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the NF signal values for recognition task 1 accuracy (r = −0.10, p = 0.95), recognition task 1 recall (r = −0.10, p = 0.87), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = −0.87, p = 0.05). Furthermore, there were no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the LTR values for recognition task 1 accuracy (r = 0.3, p = 0.68), recognition task 1 recall (r = 0.05, p = 0.93), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = 0.10, p = 0.87).

3.2.4. NF Signal Transition within Sessions (P02)

For the first and final sessions, the within-session transitions of NF signal values were compared between Up and Down conditions (

Figure 15). In the first session, both the Up and Down conditions exhibited higher values throughout almost all trials compared to trial 1. The Up condition had a greater number of trials surpassing trial 1 compared to the Down condition. On the other hand, during the final session, the NF signal value mostly exceeded that of trial 1 in the Up condition, while remaining lower than trial 1 in the Down condition across most trials.

3.2.5. Low Theta Power Ratio (LTR) Changes across Sessions (P02)

The baseline LTR

1 varied by a few percent between sessions: 5.65% in session 1, 6.04% in session 2, 7.23% in session 3, 10.02% in session 5, and 6.06% in session 6. A comparison between conditions was performed for LTR

i values from trial 2 onwards, similar to the NF signal analysis (

Figure 16). When comparing Up and Down conditions for the same session number, no significant differences were observed in either the first session (

z = 1.216,

p = 0.233,

r = 0.200) or the final session (

z = −0.650,

p = 0.531,

r = 0.108). In the Up condition, as sessions progressed, there was a significant decrease in LTR

i values, with a large effect size (

z = 3.565,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.594). However, there were no significant changes between sessions in the Down condition (session 1 vs session 3,

z = 1.793,

p = 0.075,

r = 0.295; session 1 vs session 5,

z = 0.881,

p = 0.391,

r = 0.145; session 3 vs session 5,

z = −0.803,

p = 0.435,

r = 0.130).

3.2.6. Frequency Band Power Changes across Sessions (P02)

The transitions between sessions of total power, delta power, and low theta power are presented in

Figure 17. It is important to note that the vertical scale of the low theta power graph differs from the graphs of other frequency band powers. Delta power was consistently higher than low theta power throughout the sessions. When comparing the trends of NF signal values with each frequency band power, a negative correlation trend can be observed with all frequency bands, particularly with low theta power. Furthermore, the patterns of low theta power changes exhibited similarities to the performance changes in recognition task 2.

3.2.7. Time-Frequency Maps for Correct and Error Trials (P02)

The time-frequency maps for Correct and Error trials are shown in

Figure 18a,b. Both maps exhibited intermittent power increases in the theta, alpha, and high beta bands. It was observed that Correct trials displayed stronger and sustained power increases (

Figure 18c).

3.2.8. Time-Frequency Maps for Up/Down and First/Final Sessions (P02)

The time-frequency maps for the Up and Down conditions, as well as the first and final sessions, along with the difference maps between sessions, are presented in

Figure 19. In comparison between the Up and Down conditions, sustained power increases in the gamma band were observed for the Down condition compared to the Up condition, both in the first and final sessions. In the first session, a slight power increase from the low theta to beta frequency bands was observed for the Up condition compared to the Down condition. However, a significantly large cluster indicating a power decrease in the delta frequency band for the Up condition compared to the Down condition spread from the early to the mid-encoding period. In the final session, the Down condition exhibited a power increase compared to the Up condition across all frequency bands starting before the presentation of the first-word stimulus. Additionally, a significantly large cluster indicating increased powers from the low theta to alpha frequency bands was observed for the Down condition compared to the Up condition during the early-encoding period. When comparing the first and final sessions, regardless of the Up or Down conditions, a power increase from the low theta to low gamma frequency bands was observed in the final session compared to the first session. In the Up condition, a significantly large cluster indicating a power increase was observed for the final session compared to the first session during the late-encoding period, spanning from the low theta to alpha frequency bands. Similarly, in the Down condition, a significantly large cluster indicating a power increase was observed for the final session compared to the first session, spreading from the early to late-encoding periods, encompassing the low theta to alpha frequency bands, and extending to the gamma frequency band during specific time periods.

3.3. Results for P03

P03 completed seven sessions of memory NF training over a span of four days. After the series of NF training, P03 underwent right selective hippocampal-amygdala resection surgery, which resulted in the disappearance of seizures. In the post-surgery WMS-R assessment, the verbal memory index score was 92, showing a small change from the preoperative score of 91, indicating that verbal memory function was not impaired.

Throughout all sessions, P03 focused on memorization during the encoding period, and reports indicated that P03 did not find out the strategy to make the supporting team win until the end. There was a report of slight distraction after session 4. For session 5, it was observed that artificial noise with high amplitude was mixed during trial 1, making it difficult to adjust noise reduction using ASR. Since the NF signal values used trial 1’s LTR as the baseline, session 5 was excluded from the analysis.

3.3.1. Intracranial Electrodes Used for Memory NF (P03)

In P03, subdural electrodes (Unique Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were implanted in the left MTL. Four platinum electrodes (3.0mm in diameter) were laterally placed at 10mm intervals (centre to centre) along the left parahippocampal gyrus, and intracranial EEG was measured and used for NF (

Figure 20). A reference electrode placed on the dural side of the left temporoparietal lobe was used for P03.

3.3.2. Performance Changes in the Recognition Task (P03)

The session-to-session changes of the three scores for the recognition task are shown in

Figure 21. The performance of the recognition task 1, for both accuracy and recall, decreased from session 1 to 2 and then increased. In contrast, the accuracy of the recognition task 2 decreased from sessions 1 to 3 and then increased from sessions 4 to 6.

3.3.3. NF Signal Changes across Sessions (P03)

The session-to-session changes in NF signal values (LTR

i/1) are presented in

Figure 22. The medians of the NF signal values were higher for Up compared to the baseline (LTR

1/1) in session 1 (

Mdn = 115.29, n = 19,

z = 2.140,

p = 0.032,

r = 0.491), session 3 (

Mdn = 103.34, n = 19,

z = 0.850,

p = 0.396,

r = 0.195), and session 7 (

Mdn = 101.26, n = 19,

z = 0.295, p = 0.768, r = 0.068), although not significantly. However, in session 2 (

Mdn = 167.96, n = 19,

z = −4.621,

p < 0.001,

r = 1.060) and session 4 (

Mdn = 140.12, n = 19,

z = −4.621,

p < 0.001,

r = 1.060) for the Down condition, the NF signal values were significantly higher compared to the baseline, with a large effect size. In session 6 (

Mdn = 94.43, n = 19,

z = −0.850,

p = 0.396,

r = 0.195), the median of the NF signal values for Down was lower than the baseline, but not significantly. When comparing Up and Down conditions for the same session number, Down showed significantly lower values than Up in the first session (

z = −4.744,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.770), as well as in the second session (

z = −4.160,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.675), with a large effect size. However, in the final session, there was no significant difference in NF signal values between Up and Down (

z = 0.336,

p = 0.751,

r = 0.054). In the Up condition, the NF signal values were significantly lower at the final session (session 7) than at the first session (session 1), with a moderate effect size (

z = −2.409,

p = 0.015,

r = 0.391). There were no significant changes in NF signal values between other sessions of Up condition (session 1 vs session 3,

z = 1.036,

p = 0.311,

r = 0.168; session 3 vs session 7,

z = −1.445,

p = 0.154,

r = 0.234). In the Down condition, NF signal values decreased significantly as sessions progressed, with a large effect size (session 2 vs session 4,

z = −3.606,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.585; session 2 vs session 6,

z = −5.270,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.855; session 4 vs session 6,

z = −5.065,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.822).

There were no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the NF signal values for recognition task 1 accuracy (r = −0.70, p = 0.12), recognition task 1 recall (r = −0.72, p = 0.11), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = 0.03, p = 1.00). Furthermore, there were no significant correlations between the performance on the recognition task and the LTR values for recognition task 1 accuracy (r = −0.15, p = 0.77), recognition task 1 recall (r = 0.48, p = 0.34), and recognition task 2 accuracy (r = −0.26, p = 0.66).

3.3.4. NF Signal Transition within Sessions (P03)

For the first and final sessions, the within-session transitions of NF signal values were compared between Up and Down conditions (

Figure 23). In the first session, the Up condition initially showed a lower trend but gradually increased above trial 1 as the session progressed. On the other hand, the Down condition consistently exhibited higher values than trial 1 throughout all trials, showing higher values than the Up condition. However, in the final session, neither the Up nor Down condition showed significant increases nor decreases from trial 1.

3.3.5. Low Theta Power Ratio (LTR) Changes across Sessions (P03)

The baseline LTR

1 varied between sessions: 25.01% in session 1, 20.69% in session 2, 28.18% in session 3, 25.01% in session 4, 34.81% in session 6, and 34.41% in session 7, with late sessions being larger than early and mid sessions. A comparison between conditions was performed for LTRi values from trial 2 onwards, similar to the NF signal values (

Figure 24). The comparison of conditions for the same session number revealed that the Down condition had significantly higher LTR values than the Up condition in the first session (

z = −2.817,

p = 0.004,

r = 0.457) and second session (

z = −2.701,

p = 0.006,

r = 0.438), with a moderate effect size. In the Up condition, there were no significant differences between sessions (session 1 vs. session 3,

z = −0.219,

p = 0.840,

r = 0.036; session 1 vs. session 7,

z = −1.825,

p = 0.070,

r = 0.296; session 3 vs. session 7,

z = −1.562,

p = 0.123,

r = 0.253). Similarly, in the Down condition, there were no significant differences between sessions (session 2 vs. session 4,

z = −0.511,

p = 0.624,

r = 0.083; session 2 vs. session 6,

z = 0.423,

p = 0.686,

r = 0.069; session 4 vs. session 6,

z = 1.036,

p = 0.311,

r = 0.168).

3.3.6. Frequency Band Power Changes across Sessions (P03)

The changes in total power, delta power, and low theta power across sessions are illustrated in

Figure 25. In the early sessions, delta power showed a more prominent difference than low theta power between Up and Down conditions (Up > Down). Negative correlations were observed between all band powers compared to the changes in NF signal values.

3.3.7. Time-Frequency Maps of Correct/Error Trials during Encoding Period (P03)

Time-frequency maps for Correct and Error trials are shown in

Figure 26a,b. Both maps display intermittent power increases in the theta and alpha bands, with Error trials exhibiting stronger and more sustained power (

Figure 26c).

3.3.8. Time-Frequency Maps for Up/Down and First/Final Sessions (P03)

The time-frequency maps for the Up and Down conditions, as well as the first and final sessions, along with the difference maps between sessions, are presented in

Figure 27. In comparison between the Up and Down conditions, both in the first and final sessions, the Up condition showed more continuous power increases across a wide frequency range from delta to gamma. In the first session, a significantly large cluster indicating a power increase, primarily centred around the delta and theta bands, extended throughout the entire encoding period, expanding to the gamma band during specific time periods. In comparison between the first and final sessions, both Up and Down conditions showed power increases from the low theta to beta bands in the final sessions compared to the first session. In the Up condition, a significantly large cluster indicating a power increase was observed during the early-encoding period, covering the low theta to beta band. On the other hand, in the Down condition, a significantly large cluster indicating a power increase was observed throughout the entire encoding period, covering the low theta to alpha bands, expanding to the beta band during specific time periods.

4. Discussion

In this study, we administered bidirectional NF training aimed at increasing and decreasing (Up/Down conditions) the low theta power ratio (LTR) of the MTL in three patients with intractable epilepsy. We observed that the difference in NF signals between the conditions (Up−Down) increased as sessions progressed. The NF signal changed significantly only in one direction (Up or Down) for all participants, yet the opposite-direction NF served as an important intra-subject control condition demonstrating the NF effect, enabling us to exclude potential confounders such as motivation, visual modality, and eye movement as their influences were almost identical across conditions.

The reason why changes in the session progression of NF signal values were observed only in one direction can be attributed to the effect of the anterograde interference observed in motor and perceptual learning [

69,

70]. When alternating between task A and task B, anterograde interference reflects how the memory of task A impacts the learning of task B. The impact of Task B on the memory of task A is termed retrograde interference, which is known to have a less effects than anterograde interference [

70]. The studies using fMRI-based bidirectional NF reported that anterograde interference could influence the NF effect in the latter half NF sessions [

71]. This anterograde interference may also explain the discrepancy between our current and previous study [

24]. In the previous study, we performed NF using intracranial electrodes longitudinally placed along the left parahippocampal gyrus and reported an increase in theta power (4-8Hz) for one participant. In this study, despite the same electrode location for P02, the NF signal values decreased over sessions for both Down and Up conditions. It is possible that the memory of Down NF influenced the learning of Up NF. However, precise cause identification is challenging due to differences between the current and the previous study, including the number of sessions for Up condition, NF signal values, and NF modality used.

No correlation was observed between the transitions of memory task scores and the transitions of NF signal values. The first potential reason is that, given the within-subject design in which bidirectional NF was conducted, the two types of NF may have interfered with each other, preventing observable changes at the behavioural level [

71,

72]. A second factor may be that the mental strategy for NF interfered with the execution of the memory task. In this study, we did not provide participants with a clear mental strategy for NF. Consequently, one participant (P01) adopted an unexpected strategy of randomly answering the recognition task, resulting in a significant decrease in accuracy in recognition task 1 compared to other sessions. Offering a clear mental strategy to participants before the start of memory NF may prevent such unforeseen strategies and potentially influence the success and efficiency of NF. While the relationship between the provision of a mental strategy and the outcomes of NF is a topic of current investigation [

73], systematic studies have been limited [

74], and there are no established standards for providing strategies [

75]. Research on instructional design suggests that feedback is more effective when goals are clearly defined and specific [

76]. NF training might be improved by providing participants with objectives, purposes, and mental strategies, thereby reducing trial and error [

73]. On the other hand, even if a mental strategy that directly affects task performance is prevented, the mental strategy itself might create a dual-task situation with the memory task, divide attention, and indirectly affect the performance of the memory task [

77,

78]. Another factor may have been insufficient trials per session to evaluate memory function. However, increasing the number of trials was difficult due to considerations for minimising the burden on the patients. In future research addressing the second and third factors, it is conceivable to introduce memory tasks separate from memory NF, allowing for independent evaluation of memory function.

In the time-frequency analysis of the encoding period, we confirmed intermittent increases in theta and alpha power for both the trials in which the order of word presentation was successfully recognised (Correct) and the trials where it was not (Error). The association between theta oscillations and memory has been suggested based on a wealth of past research [

44,

79], and an increase in theta oscillations during the encoding period has been reported in scalp EEG studies [

41,

47,

80,

81,

82], MEG studies [

42,

83], and iEEG studies [

43,

45,

46,

84], supporting our study results. Theta and alpha power have also been suggested to be associated with memory retention [

81,

85], with reports of theta and alpha power in the MTL increasing in response to memory load [

86], and an increase in alpha activity during the retention of the order of word sequences [

87]. In this study, because participants were questioned the order of word presentation in the recognition task 2, the memory load was heavier and the neuronal activity involved in word retention may also have been reflected in the encoding period than in previous studies that only asked whether words were present. In the comparison of correct and error recognition of the order of word presentation, two participants (P01, P03) showed a relative decrease in theta power during successful encoding, consistent with many intracranial studies that asked whether words were present and conducted a correct and error comparison [

45,

54,

58,

88,

89,

90]. Particularly for P01, in the middle of the encoding period, a relative increase in low theta power before stimulus presentation and a relative decrease in low theta power during stimulus presentation were observed in relation to successful encoding. The increase in low theta power before stimulus presentation has been reported in multiple studies [

43,

84,

91], and is suggested to be associated with the preparatory process for stimulus processing of encoding. For P01, the preparatory state in the middle of the encoding may have affected the success of the recognition task. On the other hand, P02 observed intermittent increases in theta and alpha power as neural activity associated with successful encoding, and an increase in activity in the beta band was also observed. Most conventional studies that asked whether words were present reported a decrease in power in these bands [

52,

54,

57,

89,

90,

92,

93], and the results of P02 in this study may seem contradictory at first glance. However, in this study, we based the correct and error encoding on the recognition of the order of word presentation, and we analysed 13 seconds including before and after the presentation of five words. Therefore, compared to conventional studies, this study may reflect neuronal activity related to word retention and memory of word order. P02 had lower scores on the recognition task compared to other participants, so the memory load, or difficulty, may have been relatively high. Since memory retention increases theta and alpha power depending on the load [

81,

86,

87], P02 may have been more affected by memory retention on the correctness of the recognition task than other participants, resulting in different results. The increase in beta power in the MTL during successful encoding has been reported in several previous studies [

45,

84], and is suggested to be associated with sensory processing. Furthermore, increases in alpha and beta band activity before the presentation of the encoding word have been reported in the neocortex and MTL [

43,

84], suggesting associations with predictive and attention processes [

48,

54], and inhibitory top-down control of sensory processing [

43,

45,

54]. In P02, these cognitive functions, which are deeply involved in memory, may have affected the succcess of encoding more than in other participants. In fact, P02 commented that he took mental strategies such as adjusting his concentration during encoding, and previous studies have suggested that volitional control can regulate a brain network composed of the hippocampus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum, benefiting memory function [

94].

In the time-frequency analysis, none of the participants showed a change in gamma power between Up and Down conditions first and final sessions, compared to other frequency bands. Specifically, regardless of the first or final sessions, two participants (P01 and P03) observed intermittent increases in gamma power in the Up condition compared to the Down condition, while P02 observed the opposite. One possible reason for the small change before and after training could be that the gamma band was not included in the calculation of the NF signal values used in this study, so the effect of NF might have been smaller than in other bands. The increase in gamma band activity during encoding has been reported in previous studies [

46,

48,

54,

55,

90,

95,

96], and has been suggested to reflect an increase in attentional resources [

48,

96] and the association of stimuli with spatiotemporal context, which supports the formation of episodic memories [

56,

92]. As for alpha and beta power, in two participants (P02 and P03), the power increased in the final sessions compared to the first sessions, regardless of the Up/Down condition. Low theta power also increased similarly but considering that the NF signal values decreased over the sessions in both conditions, the influence of increase in activity in the alpha and beta bands can be inferred to have been relatively high. Considering the association of alpha and beta oscillations with predictive and attentional processes during encoding [

48,

54], as well as the inhibitory top-down control [

43,

45,

54], it is conceivable that being accustomed to the tasks over multiple sessions may have affected these cognitive functions related to encoding. On the other hand, in P01, although the relationship of alpha and beta power between conditions was firstly Up < Down, the power increased in the Up condition and decreased in the Down condition over the sessions, resulting in Up > Down in the final session. This suggests that the current NF training, which aimed to adjust theta power, may have affected prediction and attention processes during encoding [

48,

54], as well as inhibitory top-down control [

43,

45,

54], and as a result, alpha and beta power may also have been indirectly adjusted. However, Further study is needed to determine the causes of these differences between participants. Next, we will proceed with the interpretation of the results specific to each individual participant.

1.1. Discussion on the Results of P01

In the case of P01, it is inferred that the dominant side for verbal memory function was the left side, as verbal memory function declined after surgery. Unlike the other participants, P01 underwent NF for the right MTL, which is more closely associated with visual memory function, rather than the left MTL, which is deeply related to verbal memory function. In this study, despite the use of a standard verbal memory task, the NF training resulted in differences in neural activity in the right MTL and performance on the recognition task 2 between the Up and Down conditions. The possible reasons for this could be: 1. the nature of the memory task, which involved visually presenting words on a monitor, might have evaluated not only verbal encoding function but also visual encoding function; 2. the right side may have also been responsible for verbal encoding function, not just the left side. For 1, in the future, when assessing the effect of NF solely on verbal encoding function, it could be helpful to use stimuli that are less likely to involve visual processing, such as auditory stimuli. For 2, based on the elapsed years since the onset of epilepsy and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis in the left MTL, it can be inferred that verbal memory function may have been partially reorganized towards the right MTL, potentially serving as an alternative or complementary role of the left MTL. Regardless, as evidenced by the observed similarity in the trends of NF signal values and performance on memory tasks, it is speculated that in the case of P01, there is a possibility that NF not only adjusted neural activity but also memory function.

Considering the fact that there was a difference in total power, which is the denominator of NF signal values, between Up and Down conditions (Up > Down), it can be interpreted that the trend of NF signal values was largely contributed by the trend of low theta power. Moreover, seeing the similarity with the transition of accuracy in recognition task 2, it can be considered that low theta power may have played an important role in encoding in P1.

In the Up condition, the NF signal values significantly increased from the first session (session 1) to the final session (session 3), and in the intra-session trends of NF signal values, a steeper rise from trial 1 was observed during the final session compared to the first session. Additionally, in the comparison of time-frequency maps, it was confirmed that theta power was intermittently increasing more in the final session than in the first session in the Up condition. These results may suggest an accumulated NF effect in the Up condition. On the other hand, this adjustment of theta power may have been caused by the expectation of reward. The relationship between reward and theta activity has been suggested in rodent studies [

97], and in humans, it has been suggested that reward motivation is associated with successful memory encoding [

98,

99]. One study reported an increase in theta power just before word presentation associated with successful encoding under high reward conditions [

100]. Although not mentioned by the authors, Figure.3C of this paper shows a visible increase in theta power immediately after word presentation associated with successful encoding under low reward conditions. In P01’s session 3, due to a system error, NF continued to make it difficult for the red team to win, which might have created a low reward condition unexpectedly, potentially inducing an increase in theta power.

1.1. Discussion on the Results of P02

The transition in NF signal values across sessions and the transition in frequency band powers across sessions demonstrated a negative correlation trend. This suggests that the transition in NF signal values was more heavily influenced by power in other frequency bands rather than by low theta power. Specifically, delta power had a higher value than low theta power, potentially exerting a greater influence on total power. Consequently, the transition in NF signal values may have strongly reflected the change in delta power.

We observed a negative correlation trend between the scores of the recognition task and NF signal values. However, considering the similarity observed between the scores of the recognition task and low theta power, it is plausible that in P02, low theta power played a crucial role in the encoding process. In this study, we aimed to modulate neural activity contributing to memory encoding with the Up/Down conditions. However, contrary to our intentions, it is possible that the adjustments performed in the Up/Down conditions had resulted in the opposite direction of modulation.

In the Up condition, we observed a trend of declining NF signal values as the sessions progressed. Even the comparison of LTRi values across sessions, excluding trial 1, showed a downward trend in the Up condition. This could be attributed to the rise in total power, especially the rise in delta power being stronger than the increase in low theta power. The same declining trend of NF signal values was observed in the Down condition, along with a rising trend in power across frequency bands (total power, delta power, low theta power), just as in the Up condition. However, unlike Up, the comparison of LTRi values across sessions, excluding trial 1, did not show any significant differences within the Down condition. This could be because, in the Down condition, low theta power rose as much as total power and delta power, resulting in no significant difference in LTRi across sessions. The strong upward trend in low theta power in Down compared to Up may be due to the unintentional adjustment of low theta power in the opposite direction in the Up/Down condition. The direct cause for the decline in NF signal values in Down is inferred to be the magnitude of LTR1 value. The values of LTR1 in Down were increasing, from 5.65% in session 1, to 7.23% in session 3, and 10.02% in session 5. One interpretation for this rise in LTR1 values in Down is the carryover effect due to NF training in the previous Up session aimed at increasing LTRi. Furthermore, as there is no significant difference in LTRi values between conditions in the final session, the significantly lower NF signal value in session 5 in the Down condition compared to session 6 in the Up condition (LTR 1 value: 6.06%) is likely to be due to the magnitude of LTR1 value.

P02 reported in the later sessions that concentrating to remember led to the Red team winning, while remembering with relaxation led to the White team winning. This study’s difference in concentration during memory encoding might be interpreted as a difference in load during the memory retention process. Increases in theta activity in the frontal midline area have been reported when engaging in tasks that require focused attention or high-load memory tasks [

101,

102,

103]. The hippocampus is known to be strongly connected with the prefrontal cortex [

104,

105], and is suggested to contribute to cortical theta activity through their interaction [

40]. Furthermore, one study reported an increase in MTL theta power during memory retention with increasing memory load [

86]. Taking these into account, when concentration was needed for memory, theta power might have increased, resulting in a rise in NF signal values and the Red team winning, while in a more relaxed state, theta power might have decreased, leading to a decrease in NF signal values and the White team winning. The reason why the NF signal values were higher than the baseline in trial 1, regardless of Up/Down in the first sessions, might be due to the increase in theta power as P02 still needed to focus on remembering. Additionally, as the scores in the recognition task 2 were lower in the first sessions compared to other sessions, it can be inferred that the memory task imposed a high load during these first sessions.

1.1. Discussion on the Results of P03

Interestingly, in the first and intermediate sessions of NF training for P03, the NF signal values and LTR

i were higher in Down (session 2, 4) than in Up (session 1, 3). Given the negative correlation trend between the transitions in NF signal values and transitions in frequency band powers, it can be inferred that the transitions in NF signal values was more heavily influenced by the power in other frequency bands than by low theta power. Particularly, delta power exhibited larger differences between conditions (Up > Down) in the first and intermediate sessions than low theta power, with the magnitude of this power difference being similar to that in the total band. Additionally, in the first session comparison of the time-frequency map between conditions, we observed clusters indicating intermittently lower delta power in Down than in Up. Considering these, we can infer that delta power significantly influenced LTR and NF signal values in P03, similar to P02. Although we were unable to confirm any similarities or negative correlations between the transitions of neural activity and the transitions of scores in the memory task in P03, the differences between NF conditions were most apparent in the delta band. This suggests that delta power in P03 might be deeply associated with the memory encoding function, similar to or even more than low theta power. Some studies have reported modulation of delta power during encoding [

45,

52,

53,

93], and Lega et al. [

45] have asserted its functional significance, noting the similarity between oscillations below 4Hz in human MTL and memory-related theta oscillations observed in the hippocampus of animals. If delta power contributed to encoding more than low theta power in P03, then, given the observed negative correlation trend between NF signal values and delta power, we may have unintentionally conducted NF that decreased delta power in Up and increased it in Down.

To investigate the causes of the differences in NF signal values and LTR

i (Up < Down) in the first and intermediate sessions, we examined the within-session transitions in delta power and low theta power, as shown in

Figure 28.

In Up, delta power transitioned higher than low theta power. This suggests that delta power had a significant impact on NF signal values. In Up, delta power remained high for the first few trials but later declined to values similar to trial 1. In the first session of Up, NF signal values were lower than trial 1 for the first few trials but later transitioned to values similar to or higher than trial 1. Considering these, it is conceivable that in P03, the loss of the red team in the first few trials in Up became a negative reinforcement in NF learning, causing a decline in delta power to a level similar to trial 1 and changing the NF signal values. However, LTRi and NF signal values were not elevated significantly beyond the baseline. This might be due to the loss of negative reinforcement when escaping from the losing situation of the red team and the subsequent repetitions of the increase and decrease of NF signal values (down to the level of trial 1), making it difficult for positive reinforcement to occur. Furthermore, the inability to observe an increase in LTRi and NF signal values in the session comparison of Up could be attributed to the potential retrograde effect of interposing Down session between Up sessions.

On the other hand, in Down, delta power remained lower and more stable than in Up throughout the session, and NF signal values were high throughout the session after trial 1, with continuous losses for the supported white team serving as feedback. The fact that delta power in Down remained lower and more stable than in Up can be interpreted in two ways. One possibility is the anterogradely carryover effect of lowering delta power in the previous Up session. The other is that the motivation for NF decreased due to the continuous losses of the white team, potentially hindering NF learning within the session. However, delta power showed an increasing trend across Down sessions. This could imply that the continuous losses of the white team served as negative reinforcers in between-session NF learning. In Down, as delta power increased, low theta power also increased, and no differences in LTRi were observed between sessions. Nonetheless, NF signal values declined with each Down session. A direct cause of this could be the magnitude of LTR1. In Down, the values of LTR1 increased, being 20.69% in session 2, 25.01% in session 4, and 34.81% in session 6. This might be a carryover effect of trying to increase NF signal values and thereby decreasing delta power in the previous Up session.

1.1. Limitation and Future Prospects

This study has several limitations. Firstly, we adopted the band power ratio rather than band power as NF signal values. Based on the previous studies that suggest the importance of frequencies below 4 Hz in the human hippocampus for encoding [