Introduction

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a rare, chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by the overproduction of platelets, which can lead to an increased risk of both thrombotic and hemorrhagic events.[

1] The diagnosis of ET is established based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, which include elevated platelet counts, bone marrow biopsy findings, and the presence of a

JAK2,

CALR, or

MPL mutation.[

2] The

JAK2 V617F mutation, in particular, is a key molecular driver of the disease and has been identified in approximately 50-60% of ET cases.[

3]

The clinical manifestations of ET can vary from asymptomatic presentations to severe thrombotic or hemorrhagic events.[

4] Among the thrombotic complications, ischemic strokes represent a significant concern, given the potential for long-term morbidity and mortality.[

5] The management of ET-associated ischemic stroke involves addressing modifiable risk factors, controlling platelet counts through cytoreductive therapy, and employing antithrombotic agents when appropriate.[

6]

This study aimed to provide a detailed analysis of the clinical presentations, diagnostic workup, and management of five patients with ET-associated ischemic strokes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from consecutive ischemic stroke patients with definitive ET treated at department of neurology in our hospital between March 2014 and February 2023. ET was diagnosed according to the World Health Organization criteria, which include a sustained platelet count ≥ 450,000/μL, bone marrow biopsy specimen showing increased numbers of enlarged, mature megakaryocytes, not meeting the criteria for other chronic myeloid neoplasms, and

JAK2 617V mutation or no evidence of reactive thrombocytosis.[

2]

Clinical characteristics, location of ischemic stroke, laboratory data (platelet count, hemoglobin level, leukocyte count, and JAK2 V617F mutation), outcome, and treatment were reviewed. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital (110757-202347-HR-04-02), and informed consents were waived for this study given its retrospective design.

Results

Out of 961 patients admitted to the neurology department during the period of March 2014 and February 2023, we identified five cases (0.52%). These cases, comprising four women and one man, represent a specific subset of individuals diagnosed with ischemic stroke and

JAK2 mutation-associated ET. The patients had a mean age of 71.8 ± 8.6 years (range, 63-85 years) and presented with various medical histories and stroke symptoms (

Table 1). The previous medical histories relevant to stroke risk factors included hypertension in four patients, diabetes mellitus in none, and hyperlipidemia in one patient. One patient (Case 5) had a history of ischemic stroke and had been treated with antiplatelet drugs prior to the current stroke event. The remaining patients had no previous history of stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA) or recognized neurological symptoms.

The mean platelet count at the time of stroke was 811,600 ± 112,528/μL (range, 643,000-949,000/μL).

JAK2 mutations were confirmed in all cases. Bone marrow biopsies were performed in all cases, revealing various findings. All patients received combined antiplatelet and cytoreductive therapy following the stroke. The therapeutic goal for platelet count is to maintain it below 600,000/μL.[

7] A hematologist performed monitoring of platelet counts (every 1-2 months) and selected the appropriate cytoreductive therapy. The status of patients was generally good, with most achieving a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-1, at discharge. The follow-up periods for the cases were as follows: 5.5 years for Case 1, 4.5 years for Case 2, 4 years and 3 months for Case 3, 2 years and 9 months for Case 4, and 3 months for Case 5, with a mean follow-up period of 3.5 ± 1.9 years. The patients remained stable during the follow-up period, with no recurrences reported, although the follow-up period for Case 5 was too short for definitive conclusions.

MRI Findings

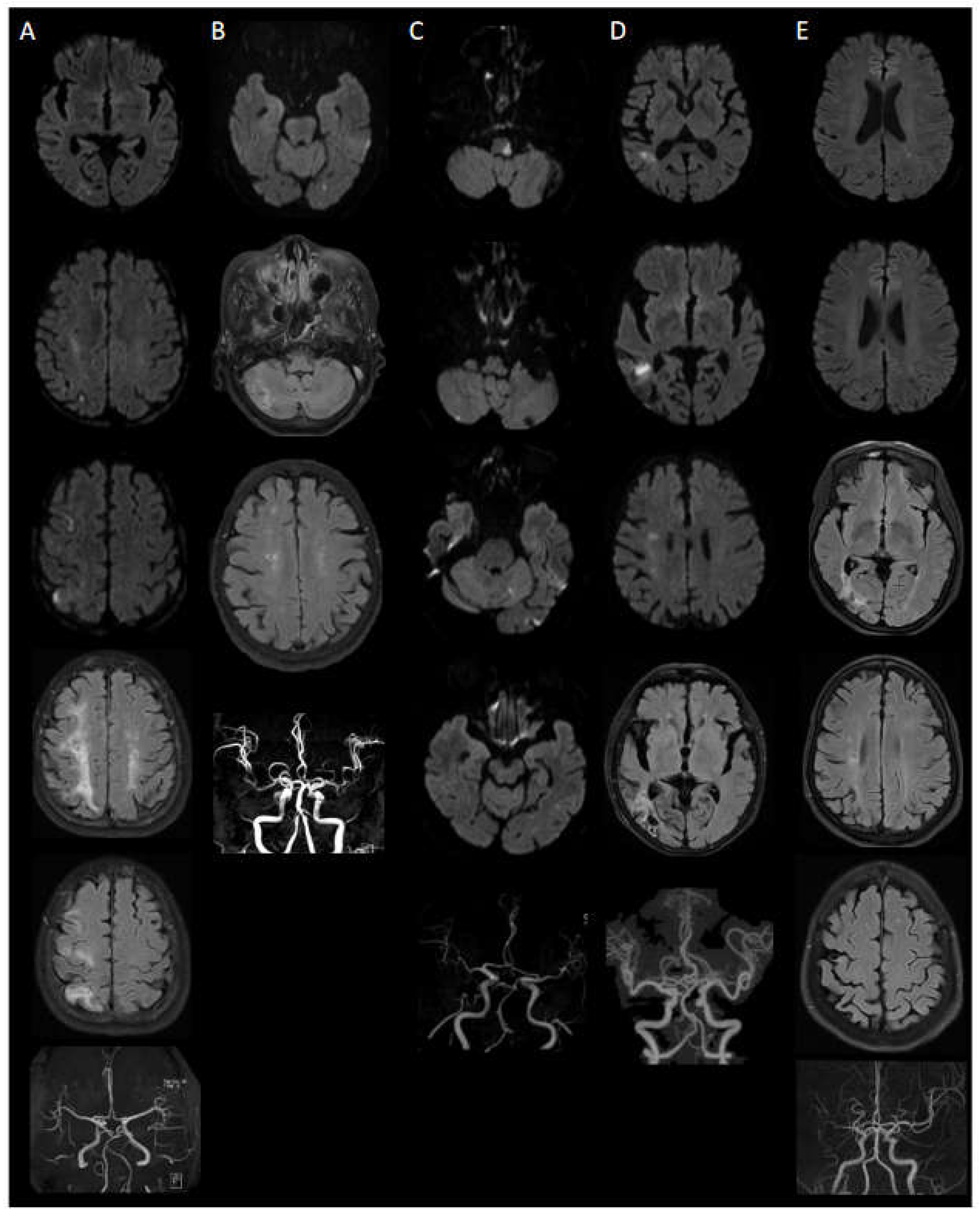

MRI findings in this case series demonstrated a diverse range of acute and chronic infarctions, lacunar lesions, white matter hyperintensities, and small vessel disease. In some instances, patients exhibited acute lesions and old leukoaraiosis, despite the absence of prior history of stroke or recognized neurological symptoms. Furthermore, small vessel occlusions and large vessel atherosclerosis were identified. Lesions were observed in both the anterior and posterior circulation areas, with certain cases exhibiting a widespread distribution of lesions throughout the brain.

Detailed Case Presentations

Case 1: A 64-year-old female presented with weakness in her left extremity. MRI findings revealed multiple lesions within the territory of the right MCA, specifically in the temporal and frontoparietal lobes, which suggested embolic infarction (

Figure 1A). However, no relevant intracranial and extracranial vascular abnormalities were detected. Furthermore, cardiac evaluations, including transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and Holter monitoring, failed to identify any potential embolic sources. Additionally, she had several lacunes, indicative of old small infarct lesions, in right frontoparietal subcortical area. Initial platelet count was 949,000/μL. Bone marrow examination revealed mild hypercellularity and marked megakaryocytic hyperplasia. The patient received cytoreductive therapy (ruxolitinib) and took antiplatelet medication (from clopidogrel (4 years) to cilostazol (18 months)). Notably, her hospital stay was prolonged (60 days) due to an accidental fall leading to an orthopedic intervention and subsequent pneumonia. Despite these complications, she was discharged with good recovery from her stroke. During the 5.5-year follow-up, no recurrence occurred, and her condition remained stable.

Case 2: An 85-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented with persistent vertigo. Imaging demonstrated a small acute infarction in the left occipital lobe and several lacunes in the right cerebellar hemisphere, both basal ganglia, and right corona radiata (

Figure 1B). Initial platelet count was 802,000/μL. Bone marrow biopsy showed normocellular to hypercellular marrow with increased and enlarged megakaryocytes. She received cytoreductive therapy (hydroxyurea) and clopidogrel for secondary stroke prevention, and follow-up MRI after 4.5 years showed no new lesions or interval changes.

Case 3: A 67-year-old male with hypertension presented with acute vertigo and ambulatory difficulties due to impaired balance. MRI revealed acute embolic infarctions in the left lateral medulla, both cerebellar hemispheres, and left temporo-occipital lobe (

Figure 1C). MRA displayed occlusion of the left VA V4 segment (

Figure 1C). The patient's initial platelet count was 829,000/μL. The patient's bone marrow showed hypercellularity and increased megakaryocytes. Despite a low initial NIHSS score, the patient required extended rehabilitation due to severe gait disturbance from imbalance, and sensory deficits in the left hemiface were not fully recovered. Despite persistent sensory deficits, the patient remained stable for over 4 years following anagrelide, hydroxyurea, and clopidogrel treatment. A follow-up MRI and MRA after 4 years and 3 months showed no new lesions or interval changes.

Case 4: An 80-year-old female presented with dizziness, and ambulatory difficulties. She had a past medical history of hypertension. MRI findings revealed acute infarction in the right temporoparietal deep white matter, subacute infarction in the right frontoparietal deep white matter and cystic encephalomalacia in the right temporo-occipital lobe (

Figure 1D). The patient's initial platelet count was 729,000/μL. Bone marrow biopsy showed slightly hypercellular marrow for her age and increased megakaryocytes. Following cytoreductive treatment with hydroxyurea and antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel, her condition remained stable for 2 years and 9 months.

Case 5: A 63-year-old female with a history of cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction and essential thrombocytosis, had discontinued her medication for approximately one month. During this period, her platelet count increased to 600,000/μL. She presented with a two-week history of right upper and lower extremity weakness (Grade 4+). MRI revealed a tiny acute infarction in the left posterior periventricular white matter and high parietal lobe, as well as cystic encephalomalacia in the right temporo-occipital lobe and focal cystic encephalomalacia in the right frontal lobe (

Figure 1E). The patient's bone marrow revealed hypercellularity and hyperplasia of megakaryocytes. She received combined antiplatelet (aspirin and clopidogrel) and cytoreductive therapy (hydroxyurea) after stroke and remained stable after 3 months; however, ongoing monitoring and adherence to medication were needed.

Discussion

This case series presents the clinical manifestations and management of five patients with ET-associated ischemic strokes, all harboring the

JAK2 mutation. The

JAK2 mutation results in constitutive activation of the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway, culminating in unregulated platelet production and a hypercoagulable state.[

8] The pathophysiology of ET is primarily driven by the

JAK2 mutation, which contributes to a higher risk of ischemic stroke in these patients. Risk factors include advanced age, prior thrombotic events, cardiovascular risk factors, and the presence of the

JAK2 mutation.[

9] The increased thrombotic risk underscores the necessity of addressing modifiable risk factors and managing platelet counts to prevent recurrent stroke events. All five patients exhibited varying neurological deficits due to ischemic strokes, with their elevated platelet counts indicating a heightened risk for thrombotic events.

The diverse radiological features observed in this series highlight the complexity of stroke manifestations in patients with ET. These findings suggest that both large and small vessel diseases could be influenced by the prothrombotic state induced by ET, as evidenced by the mixed vascular disease seen in cases 1, 2, and 5. However, it is crucial to recognize that these patients might also have other risk factors contributing to large vessel disease. Thus, further investigations are warranted to elucidate the interplay between ET and these additional risk factors in the context of large vessel disease. Furthermore, TIA is indeed common manifestations of ET.[

10] However, in our case series, neither TIA symptoms nor recognized neurological symptoms were noted in any of the five patients. Yet, on MRI, old or subacute lesions were evident in cases 1 and 4. This suggests that in ET, small-sized thromboembolic lesions may present as unrecognized lacunar infarctions.

Despite imaging suggestive of embolic infarction, with features such as involvement of multiple vessel territories or small-sized cortical/subcortical lesions, it was challenging to definitively identify an embolic source through vascular and cardiac evaluations. The absence of transesophageal echocardiogram to potentially reveal cardiac or atrial thrombi represents a limitation of this study. In the context of ET, it is theoretically more common for thrombotic strokes to occur, as an overproduction of platelets can lead to clot formation within the brain's blood vessels. Nonetheless, it's also feasible for a clot to develop elsewhere and migrate to the brain, causing an embolic stroke.[

11]

According to current guidelines, in cases where a JAK2 mutation is confirmed and arterial thrombotic events such as stroke have occurred, treatment with hydroxyurea in combination with twice-daily aspirin is recommended.[11.12] However, in these case studies, clopidogrel was used instead of aspirin, diverging from the guidelines. This was due to the fact that ET was diagnosed after the initiation of clopidogrel for stroke, leading to the decision not to switch from clopidogrel to aspirin.

Case 5 exhibited a new acute infarction in the left posterior periventricular white matter and high parietal lobe after discontinuing essential thrombocytosis medication, resulting in an increased platelet count of 600,000/μL. This observation highlights the potential association between platelet count and stroke risk in ET patients.

Effectively managing and closely monitoring patients with ET are imperative for reducing stroke risk. Regular platelet count assessments can help detect changes in disease status, facilitating timely treatment adjustments to minimize stroke risk. Our findings emphasize the importance of medication adherence and the crucial role of combined antiplatelet and cytoreductive therapy in preventing secondary stroke events in patients with ET. The heterogeneity of stroke patterns in this population necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and tailored therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2018R1C1B5045675 and NRF-2022R1F1A1074366).

References

- Tefferi A, Thiele J, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T. An overview of CALR and CSF3R mutations and a proposal for revision of WHO diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1407-13.

- Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1703.

- Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1054-61.

- Tefferi A, Barbui T. Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2021 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(12):1599-1613.

- Finazzi G, Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Ruggeri M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for bleeding in 1104 patients with essential thrombocythemia or prefibrotic myelofibrosis diagnosed according to the 2008 WHO criteria. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):716-9.

- Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, Buxhofer-Ausch V, De Stefano V, Betti S, Rambaldi A, et al. Practice-relevant revision of IPSET-thrombosis based on 1019 patients with WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e369.

- Cortelazzo S, Finazzi G, Ruggeri M, Vestri O, Galli M, Rodeghiero F, et al. Hydroxyurea for patients with essential thrombocythemia and a high risk of thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1132-6.

- Vainchenker W, Leroy E, Gilles L, Marty C, Plo I, Constantinescu SN. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms and other disorders. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-82.

- Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Passamonti F, Vannucchi AM, Morra E, Reilly JT, et al. Improving survival trends in primary myelofibrosis: an international study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2981-7.

- Tefferi A, Pardanani A. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: A Contemporary Review. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):97–105. [CrossRef]

- Haider M, Gangat N, Lasho T, et al. Validation of the revised International Prognostic Score of Thrombosis for Essential Thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis) in 585 Mayo Clinic patients. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(4):390-394. [CrossRef]

- Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T. Essential thrombocythemia treatment algorithm 2018. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(1):2.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).