Submitted:

21 June 2023

Posted:

22 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

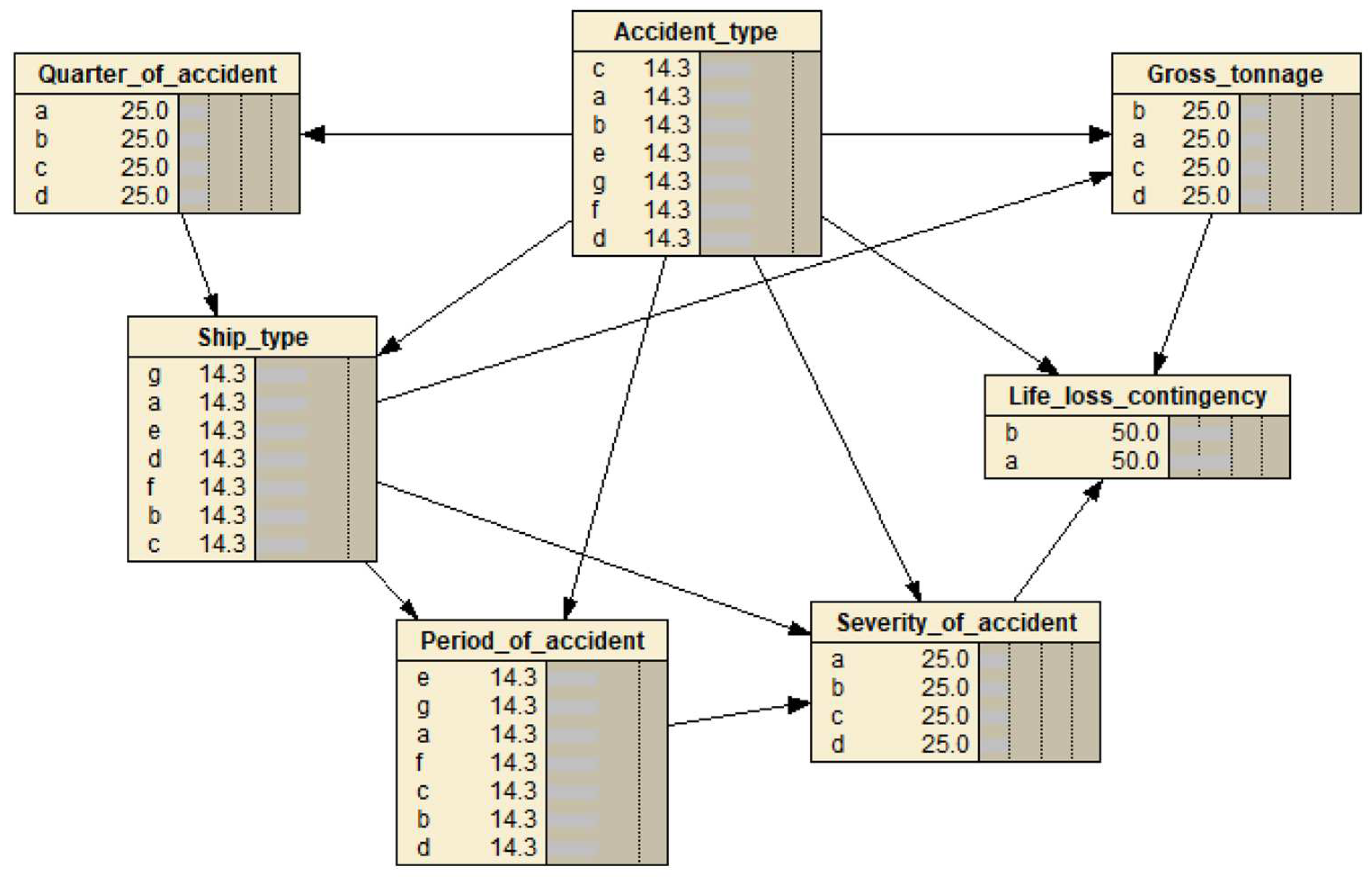

2. BN Structure Learning—TAN

3. Global Maritime Accident TAN Model

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Node Variable Definitions

3.3. TAN Modeling

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis and Model Validation

3.4.1. Sensitivity Analysis

3.4.2. Model Validation

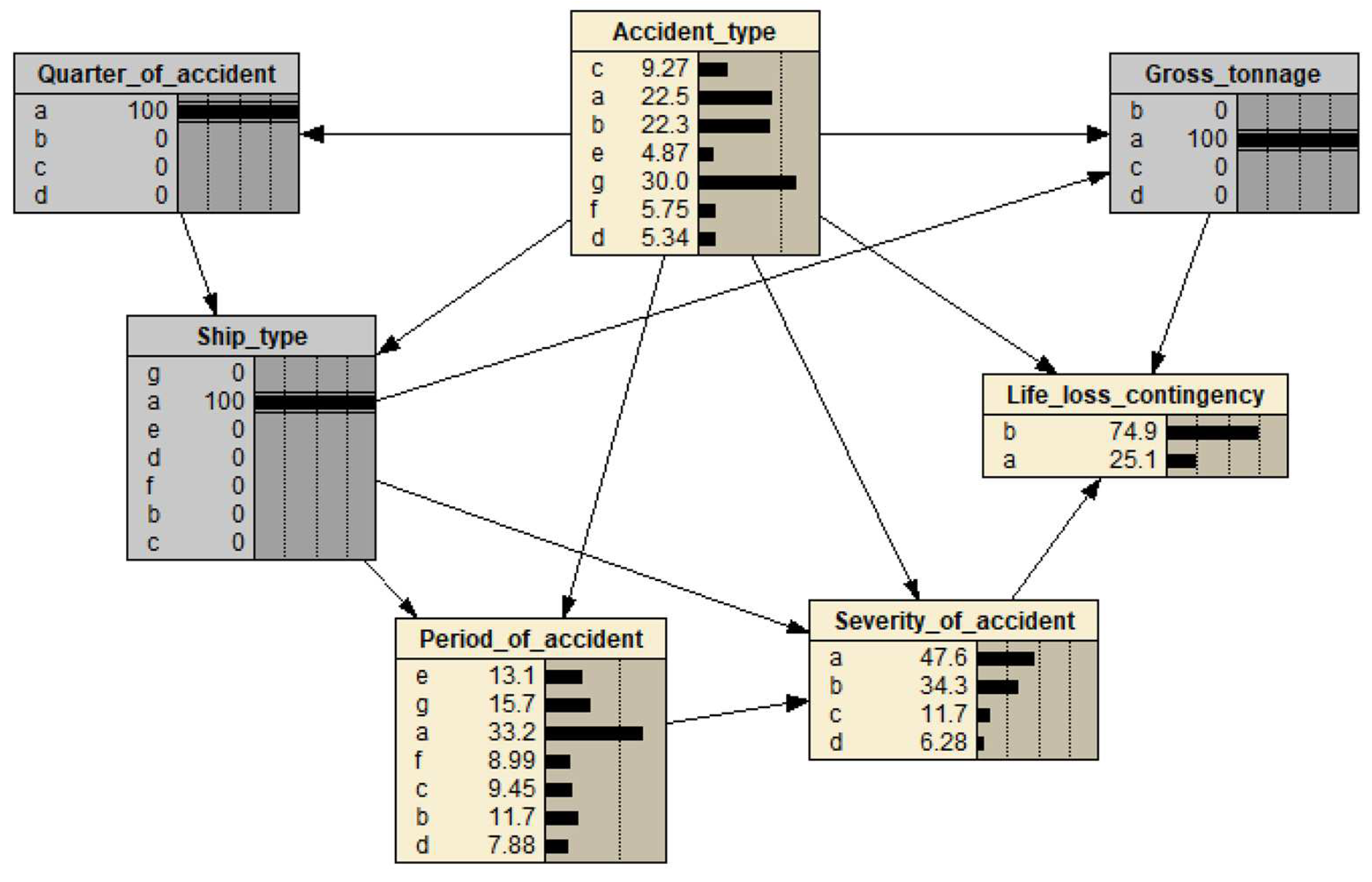

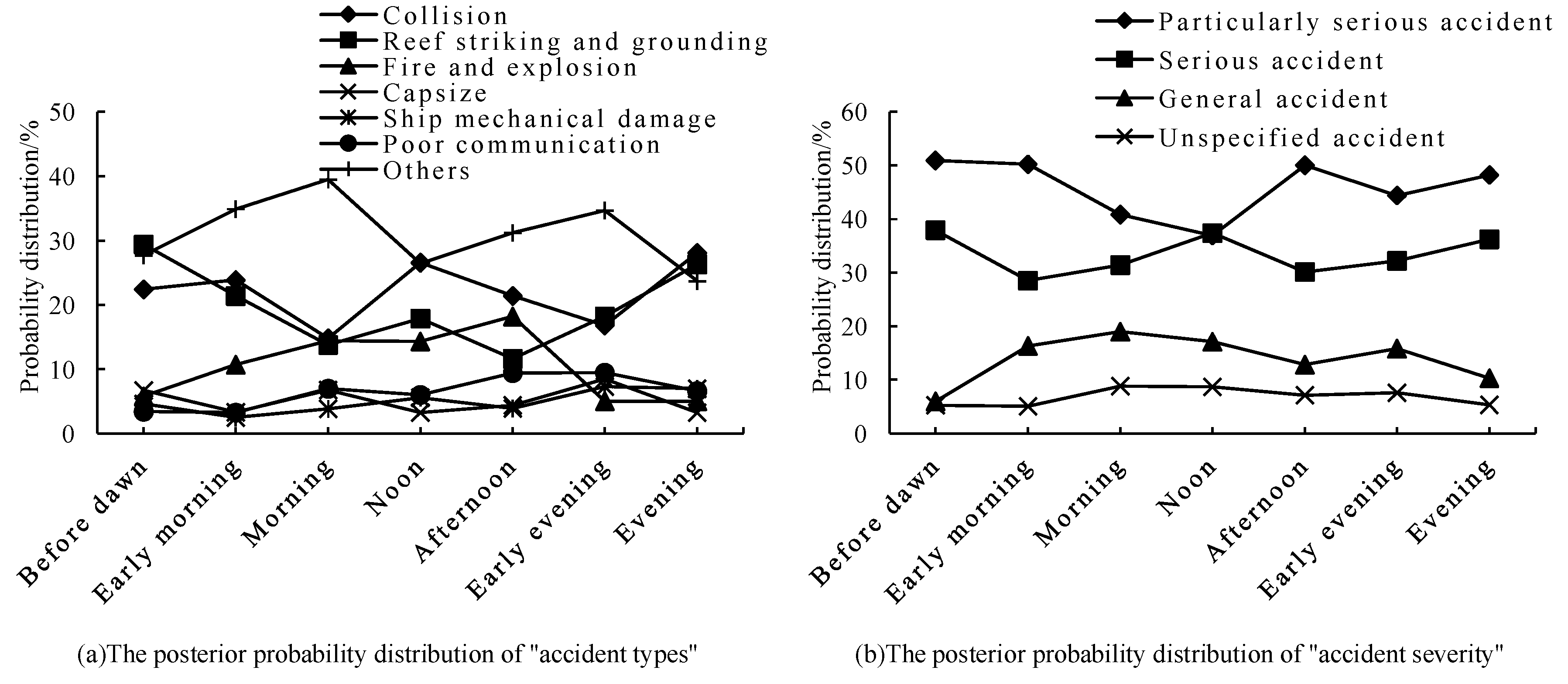

4. Model Reasoning

4.1. Accident Chain Forecast

4.2. Accident Cause Analysist

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, S.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. Incorporation of human factors into maritime accident analysis using a data-driven Bayesian network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Thai, V.V. Expert elicitation and Bayesian Network modeling for shipping accidents: A literature review. Saf. Sci. 2016, 87, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Xi, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, X. Path analysis of causal factors influencing marine traffic accident via structural equation numerical modeling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-C.; Wang, C.-N.; Hsu, H.-P.; Ding, J.-F.; Tseng, W.-J.; Yeh, C.-Y. Integrating AIS, GIS and E-Chart to Analyze the Shipping Traffic and Marine Accidents at the Kaohsiung Port. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Papadimitriou, E.; Reniers, G.; Wu, C.; Jiang, D.; van Gelder, P. A comprehensive statistical investigation framework for characteristics and causes analysis of ship accidents: A case study in the fluctuating backwater area of Three Gorges Reservoir region. Ocean Eng. 2021, 229, 108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, S.; Arslan, Ö. Quantitative analysis of dynamic risk factors for shipping operations. J. ETA Marit. Sci. 2020, 8, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yao, C.; Zhu, X.; Gao, G.; Hu, S. A decision support model for ship navigation in Arctic waters based on dynamic risk assessment. Ocean Eng. 2021, 244, 110427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jin, Y.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Xi, Y.; Han, B. Risk evolution analysis of ship pilotage operation by an integrated model of FRAM and DBN. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Meng, Q.; Xie, H. Ship accident consequences and contributing factors analyses using ship accident investigation reports. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O: J. Risk Reliab. 2019, 233, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otay, E.N.; Özkan, S. Stochastic Prediction of Maritime Accidents in the strait of Istanbul. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Oil Spills in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions; 2003; pp. 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Koromila, I.; Nivolianitou, Z.; Giannakopoulos, T. Bayesian network to predict environmental risk of a possible ship accident. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments; 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zou, X.; Lin, C. Fusing XGBoost and SHAP models for maritime accident prediction and causality interpretability analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Liu, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, S. Analysis of influencing factors on severity of ship accidents in ice-covered Arctic waters. China Safety Science Journal 2019, 29, 84. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, A.-A.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F. Marine transportation risk assessment using Bayesian Network: Application to Arctic waters. Ocean Eng. 2018, 159, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Dai, L.; Hu, H. Risk assessment of marine accidents with Fuzzy Bayesian Networks and causal analysis. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventikos, N.P.; Giannopoulos, I.F. Assessing the Consequences from Marine Accidents: Introduction to a Risk Acceptance Criterion for Greece. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 2013, 19, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bian, W.; Wan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Wang, P. Identifying factors influencing total-loss marine accidents in the world: Analysis and evaluation based on ship types and sea regions. Ocean Eng. 2019, 191, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Luo, L. Factor and trend analysis of total-loss marine casualty using a fuzzy matter element method. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivolianitou, Z.; Leopoulos, V.; Konstantinidou, M. Comparison of techniques for accident scenario analysis in hazardous systems. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2004, 17, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, X.; Xia, S.; Cao, Q. Incident tree model and incident tree analysis method for quantified risk assessment: An in-depth accident study in traffic operation. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1248–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, L.; Gao, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. Fault tree analysis combined with quantitative analysis for high-speed railway accidents. Saf. Sci. 2015, 79, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, S.-T. Evaluation of human error contribution to oil tanker collision using fault tree analysis and modified fuzzy Bayesian Network based CREAM. Ocean Eng. 2019, 179, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J.; Yu, Y.-U.; Kim, J.-K. Accident cause factor of fires and explosions in tankers using fault tree analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-I.; Jeong, J.S.; Lee, B.-G. Study on the analysis of near-miss ship collisions using logistic regression. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Informatics 2017, 21, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B. A flexible hierarchical Bayesian modeling technique for risk analysis of major accidents. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1668–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, M. Bayesian networks for maritime traffic accident prevention: Benefits and challenges. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 73, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abistado, K.G.; Arellano, C.N.; Maravillas, E.A. Weather forecasting using artificial neural network and Bayesian network. Journal of Advanced Computational Intelligence and Intelligent Informatics 2014, 18, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X.; Chen, J. Scenario analysis of road transportation accidents of inflammable and explosive hazardous chemicals. China Safety Science Journal 2019, 29, 171. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y. Human factors analysis for maritime accidents based on a dynamic fuzzy Bayesian network. Risk analysis 2020, 40, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Thai, V.V.; Yuen, K.F.; Loh, H.S.; Zhou, Q. Addressing the epistemic uncertainty in maritime accidents modelling using Bayesian network with interval probabilities. Saf. Sci. 2018, 102, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.X.; Yin, J.; Bang, H.S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Bayesian network with quantitative input for maritime risk analysis. Transp. A: Transp. Sci. 2012, 10, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Bayesian network modelling and analysis of accident severity in waterborne transportation: A case study in China. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 180, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yue, W.L. A bayesian network approach to causation analysis of road accidents using netica. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.; Wang, J.; Fan, S. Evaluation on consequences prediction of fire accident in emergency processes for oil-gas storage and transportation by scenario deduction. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2021, 72, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xie, L.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Ou, C.; Zeng, R. An ISM-BN based research on navigation risk factors of inland waterway vessels. China Safety Science Journal 2022, 32, 37. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afenyo, M.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B.; Yang, M. Arctic shipping accident scenario analysis using Bayesian Network approach. Ocean Eng. 2017, 133, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Risk analysis of maritime accidents along the main route of the Maritime Silk Road: a Bayesian network approach. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 47, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, D.; Zhang, J.; Lang, K. Causation analysis of container ship collision accidents based on improved BN. China Safety Science Journal 2019, 29, 31. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yang, Z.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. Analysis of maritime transport accidents using Bayesian networks. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O: J. Risk Reliab. 2020, 234, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, M.; Banda, O.A.V.; Kujala, P. Bayesian network model of maritime safety management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 7837–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, H.; Yu, Q. Autonomous vessels in the Yangtze river: A study on the maritime accidents using data-driven bayesian networks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, T.D.; Yoo, K.W.; Lee, D.H. GIS-based spatio-temporal analysis of marine accidents database in the coastal zone of Korea. J. Coast. Res. 2017, 79, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, Ö.; Köse, E.; Yıldırım, U.; Yüksekyıldız, E. Marine accident analysis for collision and grounding in oil tanker using FTA method. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 42, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antão, P.; Teixeira, A.; Soares, C.G. Statistical characterization of risk influencing factors in ship collision accidents. In Developments in Maritime Technology and Engineering; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magda, B. Fires as a cause of ship accidents-a statistical approach. Safety & Fire Technology 2015, 37, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ren, X.; Yang, Z. Data-driven Bayesian network for risk analysis of global maritime accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.-Z.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.-Z. Spatial analysis of maritime accidents using the geographic information system. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2013, 2326, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. Geiger, D., Goldszmidt, M. Bayesian network classifiers. Machine learning 1997, 29, 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.; Liu, C. Approximating discrete probability distributions with dependence trees. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization-Global Integrated Shipping Information System. Marine Casualties and Incidents. Available online: https://gisis.imo.org/Public/MCI/Default.aspx. (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Zhu, L.; Lu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M. Analysis of accident severity for curved roadways based on bayesian networks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ye, X.; Wang, T.; Yan, X.; Chen, J.; Ran, B. Key factors analysis of severity of automobile to two-wheeler traffic accidents based on bayesian network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Cheng, C. Spatial patterns and characteristics of global maritime accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 206, 107310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Classification | Frequency | Percentage/% | Variable Name | Classification | Frequency | Percentage/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accident quarter | a (the first quarter) | 1539 | 27.19 | Ship type | a (general cargo ship) | 989 | 17.47 |

| b (the second quarter) | 1353 | 23.90 | b (bulk carrier) | 255 | 4.50 | ||

| c (the third quarter) | 1406 | 24.84 | c (container ship) | 370 | 6.54 | ||

| d (the fourth quarter) | 1362 | 24.06 | d (chemical tanker/oil tanker) | 537 | 9.49 | ||

| Accident time | a (dawn 0-5 a.m.) | 1954 | 34.52 | e (passenger ship) | 453 | 8.00 | |

| b (early morning 5-8 a.m.) | 562 | 9.93 | f (fishing vessel) | 634 | 11.20 | ||

| c (morning 8-11p.m.) | 693 | 12.24 | g (other) | 2422 | 42.79 | ||

| d (noon 11-13 p.m.) | 427 | 7.54 | Vessel gross tonnage | a (gross tonnage [1,18500]) | 4011 | 70.87 | |

| e (afternoon 13-16 p.m.) | 647 | 11.43 | b (gross tonnage [18501,57500]) | 1219 | 21.54 | ||

| f (early evening 16-19 p.m.) | 540 | 9.01 | c (gross tonnage [57501,120000]) | 340 | 6.00 | ||

| g (evening 19-24 p.m.) | 837 | 14.79 | d (gross tonnage [120001,403342]) | 90 | 1.59 | ||

| Accident type | a (collision) | 1016 | 17.95 | Life loss contingency | a (life loss) | 1651 | 29.17 |

| b (reefed and stranded) | 823 | 14.54 | b (no life loss) | 4009 | 70.83 | ||

| c (fire and explosion) | 754 | 13.32 | Accident severity | a (particularly serious accidents) | 2837 | 50.12 | |

| d (capsize) | 365 | 6.45 | b (serious accidents) | 2034 | 35.94 | ||

| e (ship's machinery damage) | 287 | 5.07 | c (general accident) | 622 | 10.99 | ||

| f (poor communication) | 281 | 4.96 | d (unspecified accident) | 167 | 2.95 | ||

| g (other) | 2134 | 37.70 | |||||

| Nodes | Mutual Information Value | Percentage /% | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life loss contingency | 0.14246 | 5.800 | 0.0176774 |

| Accident severity | 0.14033 | 5.710 | 0.0088289 |

| Ship type | 0.04235 | 1.720 | 0.0013155 |

| Vessel gross tonnage | 0.02096 | 0.853 | 0.0004918 |

| Time period | 0.02006 | 0.817 | 0.0012170 |

| Quarter | 0.00421 | 0.171 | 0.0000869 |

| Variables | Event Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Quarterly | c | a | b |

| Time period | e | b | g |

| Ship type | g | a | g |

| Life loss contingency | a | b | b |

| Accident severity | a | b | c |

| Vessel gross tonnage | b | a | b |

| Accident type | g | b | a |

| Accident probability | 75.1% | 38.0% | 44.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).