1. Introduction

Plastic surgeons are perhaps the “surgeons of wound closure” possessing the necessary skills and expertise in order to achieve this goal in challenging clinical situations. The traditional reconstructive ladder is an essential concept and still to this day informs plastic surgeons on how to approach the choice of wound closure1,2. It has been developed through research and experience resulting in a schema whereby increasingly complex methods of wound closure are utilized. The aim is to achieve wound healing and restore function with the least amount of morbidity possible1,2.

Recent technological advancements have allowed the reconstructive ladder to evolve5,6 but still holding true to its primary principle. For example, the use of topical negative pressure has allowed the addition of a new rung of wound closure – albeit as a temporizing measure rather than a ‘technique’. The concept of the ladder continues to enhance and new interpretations, such as the reconstructive ‘elevator’, allow flexibility in the selection of the best reconstructive option to choose rather than the step-wise approach of exhausting all basic principles of closure first4,5.

The external appearance of the human body is outlined by the underlying bony skeletal scaffold, which is covered by the skin. To adapt to this complex morphology, the cutaneous covering has to be both elastic and viscous to allow deformation and return to its previous form. From a mechanical point of view, it has to be both flexible and strong.

The vectors of tension throughout the skin are specifically related to the movement and volume of the underlying shape, and high cutaneous tension is most frequently associated with imperfect or pathologic scar formation post-surgery or following lacerations.

Unfortunately, quantitative determination of skin tension is neither practical nor reliable in clinical situations and settings. On the other hand, skin wrinkles or specific lines have been commonly employed as a surrogate superficial map of tension vectors. A variety of skin lines have been considered over time7 , whilst relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) and Langer’s lines are the most commonly taken into consideration. Interrupting the cutaneous surface with a punch excision usually determines a circular wound that immediately evolves into an elliptical defect. If a multitude of punch excisions are carried out and the major axes of these ellipses are associated in continuity, the resulting line is deemed as a Langer’s line8. These vectors run parallel to the main collagen fascicles of the dermis and sometimes but not always and not necessarily follow the natural cutaneous creases.

A relaxed skin tension line (RSTL) is a groove typically resulting from the skin being pinched and relaxed in the lack of local tension9,10.

Physiologically and anatomically, the cutaneous mantle appears to be most extensible perpendicular to RSTL, and this involves that the tension is minimal in case the excisions are performed along RSTLs.

RSTLs and Langer’s lines run parallel across many regions of the body, whilst they are significantly noncoincident in mechanically sophisticated areas such as the temple, the lateral canthal region and the mouth corner.

An appropriate master of cutaneous vectors of tension is essential for correct incision and excision planning and outlines.

Inappropriate surgical planning and markings are the most common and main reason for pathologic scarring (scar hypertrophy and keloid) occurring in the course of a wound remodeling. Excessive tension across an incision may result in pulling the wound margins apart.

As a pathophysiological consequence, the wound acquires a tendency to hold itself together more tensely. Macroscopically, the scar tends to become hypertrophic. Microscopically, this turns out to be an increased collagen deposition.

The critical aspect is in the timing. Since hypertrophic responses are noticed months after an incision has been performed, the surgeon cannot correct revert the errors made.

In specific areas of high cutaneous tension, a hypertrophic reaction is unavoidable irrespective to the direction of incision (i.e. sternal area and shoulders).

Similarly and on a larger ground, incisions almost never involves the extensor aspects of the joints. The opposite holds true; flexor grooves are elect directions for surgical incisions.

Many body regions represent challenging areas, with a high incidence of skin and soft tissue tumors and high local tension causing risk of wound dehiscence or pathologic wound healing due to the retracting effect of scars. Limbs and sternal area are body regions with such features.

The problem occurs when the major axis of the lesion is not parallel to the Langer’s lines or RSTL, as the excisional ellipse might be difficult or impossible to close and the deriving scar might be at risk for the mentioned complications.

In many of these cases traditional options offered by plastic surgery are represented by skin grafts or flaps.

For general use in plastic surgery, authors have conceptualized and tested a new reconstructive rung to the ladder - the ‘parallelogram’ excision, as illustrated by

Figure 1, a method that allows to optimize the elliptical excision of a lesion whose major axis is not parallel to the RSTL.

2. Materials and Methods.

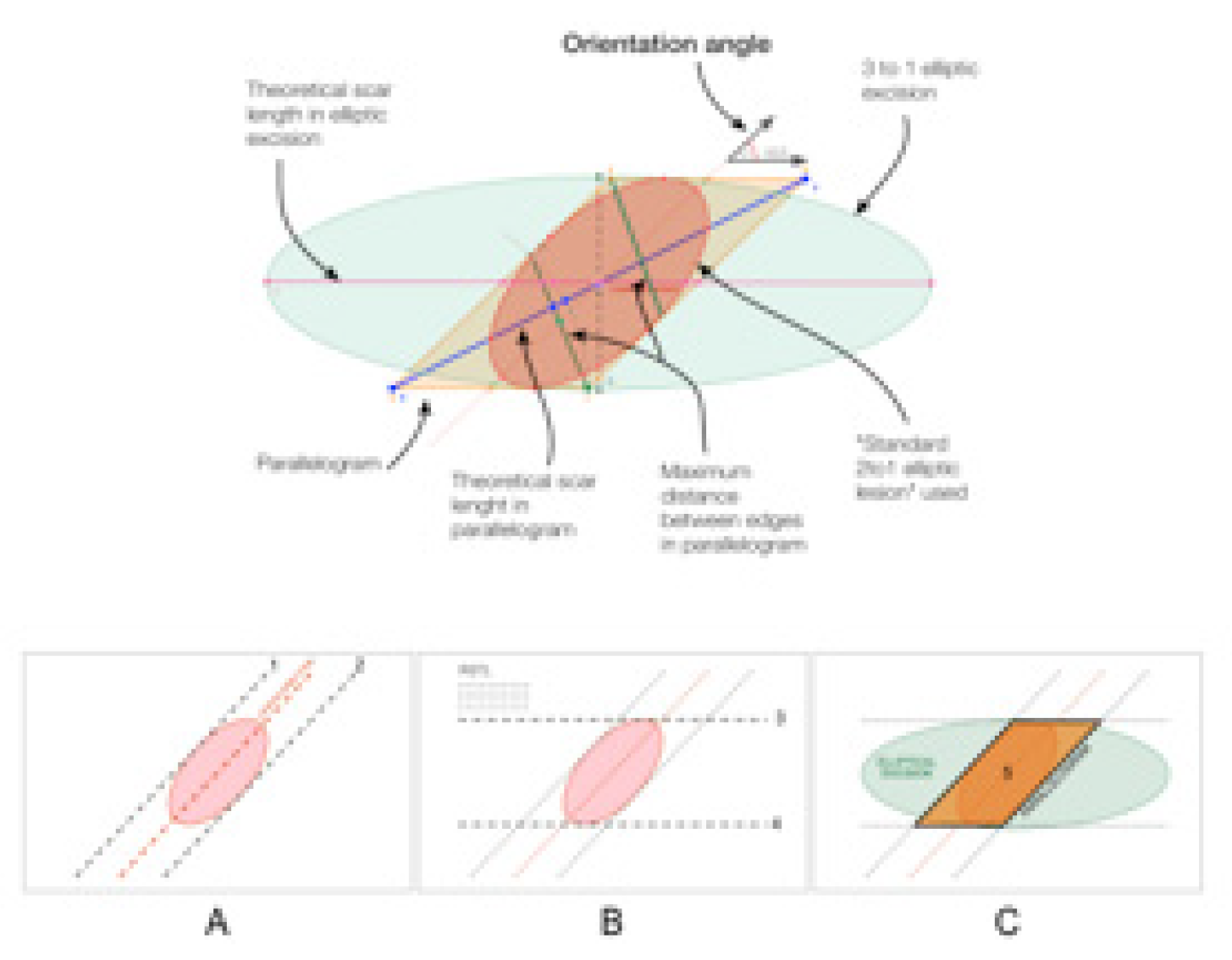

Preliminarily to the clinical study, a comparative geometrical analysis was conducted between various excision shapes and angles using Geometry Pad version 2.7.10 (Bytes Arithmetic LLC) and verifying the data obtained through AutoCAD 2D 2016 (Autodesk, San Rafael, California, USA), with the intent to optimize the technique from the geometrical point of view. A comparison was conducted between the theoretical traditional elliptical excision1,2 and the theoretical parallelogram excision. The parameters evaluated were total excision area, theoretical length of the final wound, margin distance, healthy excised area. These parameters were compared between the two scenarios (traditional ellipse versus parallelogram) in a variety of angles between the ellipse major axis and the direction of RSTL.

For this theoretical purpose, we have defined the lesion as an ellipse that has major axis double than the minor and forming with the RSTL an intersection angle (orientation angle) variable between 30 and 90 degrees.

After the preclinical part, all patients consecutively accessing the authors’ departments of plastic surgery between January and October 2022 due to skin or soft tissue neoplasms of the limbs or sternum were considered for inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria were a lesion whose major diameter was equal or smaller than 2 cm, the orientation of the major axis was angulated between 30 and 60 degrees compared to the local relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) and patients’ age was between 40 and 80.

Exclusion criteria were recurrent lesions and patients with anelastic skin as can be evaluated through a pinch test. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki declaration and no Institutional Revisory Board approval was necessary as per local policies on clinical studies.

All cases were evaluated in terms of wound healing complications. Patients were administered a satisfaction questionnaire at 6 months postoperatively with a 5 grade likert scale describing the surgical outcome as unsatisfactory, satisfactory, good, very good and excellent respectively from 1 to 5. The questionnaire explored patient’s satisfaction with the final scar.

Surgical markings and technique

Pre-operative parallelogram-shape marking of the patient was designed around the lesion in each case to excise the minimum area of tissue and to achieve direct closure as parallel as possible to relaxed skin tension lines.

The preoperative marking of the parallelogram excision, shown in

Figure 2a,b, has to be done as follows:

A. Identify the direction of the major axis of the ellipse circumscribing the lesion (plus eventual excision margins) and draw two tangents parallel to that direction

B. Draw two other tangents to the ellipse parallel to the RSTL

C. Intersect these 4 lines finding 4 vertices and outline the parallelogram

All excisions were carried out under local anesthesia as a day case procedure.

3. Results

The software analysis took into account a variety of excision orientations as illustrated in

Table 1.

In the selected period 18 patients were considered for inclusion, but three were excluded due to recurrence (two) and anelastic skin (one) and therefore underwent reconstruction through skin graft.

Among the included 15 patients, 8 were men and 7 women, the average age was 68 and no patients were smokers. Ten patients suffered from hypertension, 5 from atrial fibrillation, 3 from hypothyroidism and 2 from diabetes type 2.

All included patients had an uneventful postoperative course and all scars healed and maturated with no complications, including dehiscence, hypertrophy, hypotrophy, keloid. Out of the included 15 cases 7 were basal cell carcinomas, 5 were dysplastic nevi and 3 Bowen’s diseases. The lateral margins taken were 3 mms for the nevi and 4 mms in the other cases. All specimens were completely excised.

Most patients expressed a good to excellent degree of satisfaction with the scar and no patient declared the surgical outcome unsatisfactory (excellent: 4, very good 7, good 3, satisfactory 1).

4. Discussion

The aim of cutaneous oncologic surgery is the complete excision of neoplasms and the reconstruction of resultant defects, to let patients develop a healed scar and allow them to restart pre-surgery life in terms of work and other activities11. In case of minor defects, primary closure is possible; instead, when defects are too broad to be repaired primarily, the various options offered by the reconstructive ladder are feasible, which include full and partial and full thickness skin grafts12, halo grafts13, local flaps, regional flaps, perforator-based island flaps such as the Keystone Flap14 and reducing opposed multilobed flaps15. For excisional wounds that cannot be sutured primarily, in case the choice of a skin graft or a local flap is not feasible, microvascular free tissue transfer16 is generally the indicated solution to be utilized.

Even though repair of defects with the least tension is well proven to determine the best results in terms of both wound healing and scar-related processes, the excisional vectors that minimize tension have often been controversial and far from a general consensus in the scientific community. It has been noticed that a number of books define and outline cutaneous tension lines such as Langer’s lines diversely, and lines currently used for surgical excision may be based on a poor scientific ground17.

Borges9 initially reported the idea of utilizing RSTL for removal of skin lesions on the head and neck region. RSTLs rely on the concept that with the skin relaxed, grooves appear. Moreover these vectors become more visible by pinching skin and detecting the direction of ridges and creases9.

Nevertheless, on the rest of the body or areas such as the shoulders, sternum and lower limbs, Borges9 usually relied on Kraissl’s lines18, which basically consist of wrinkle directions.

Another important concept on the topic derives from recent studies on wound tension in surgical wounds, in which a hypothesis was described that excisional and incisional lines need to be identified and approached differently19.

Wrinkles and creases that may be adequate for surgical incisions may not be sufficiently tension-bearing to let them to deal with the increased loads posed by major excisional surgery20.

This is partially in contrast to the original study on the matter by Langer21 in which no mention was made about a possible difference between excision and incision, since the study methodology was only based on incision tests.

Even though the skin is anatomically viewed as a unique even organ and as our largest organ, a biomaterial engineering perspective reconsiders our integuments as a composite tissue with elastic behavior only at low-tension levels.

Body regions such as the feet and lower limbs, due to major weight-bearing physiology, show a cutaneous mantle that reveals greater viscoelastic behavior, i.e., tension depends on patient’s age and load20. In lower limbs with sun damage, not only can modifications due to age and UV radiations be noticed, but also the underlying elastin system demonstrates a certain degree of deterioration over time22.

In the lower limb region, especially in the legs, distally to the knees, the effect of improper orientation of excision markings is relevant, as it may involve the choice between primary closure or a skin graft with the related longer time necessary for healing and suboptimal aesthetic outcome. Hence, a correct orientation of the excisional ellipse when planning oncologic skin surgery is of paramount importance.

Scientific works exploring wound strain by means of tensiometer on different body sites have already proven that for diameters smaller than 7–8 mm, there is very little differences in wound-closing tension, irrespective to the direction of the ellipse major axis23.

Skin has often been qualified as anisotropic, but in fact, in areas adjacent to the bone such as the pretibial region, the cutaneous mantle does show orthotropy, i.e., some symmetry (in terms of tension of the excisional ellipse) relative to 2 perpendicular planes, which depends on the main and preferential orientation of collagen fibers24.

Tensiometric analyses in other areas like the scalp also revealed an evident directional predilection relative to decreased closing tension.

As noticed by Borges9, Langer’s lines were originally studied and defined21 in cadavers that had undergone rigor mortis and this bias was not taken into consideration, therefore they can hardly be defined lines of relaxation.

Anyway, in the lower limb, Borges9 complied to wrinkles as indicators of least tension lines. In anatomical sites different from the face, Borges’s lines indeed respect Langer’s lines, and in directions noncompliant with Langer’s lines, they are hindered by the cutaneous tension that results in rendering them irregular25.

In the controversial lower limb region, Paul26 demonstrated that byodinamic excisional skin tension (BEST) lines run in the vertical direction.

The parallelogram technique is a surgical procedure designed to allow excision and primary closure of skin defects sometimes deemed to need skin grafting or loco-regional flap due to the extension of the excision area and/or tightness of the skin. By improving excision geometrical characteristics, first of all the total excision area, and consenting a slight rotation of the scar toward RSTL, parallelogram excision’s purpose is to minimize the tension between wound edges and extend the direct closure applicability, delaying or avoiding the use of further step of the reconstructive ladder.

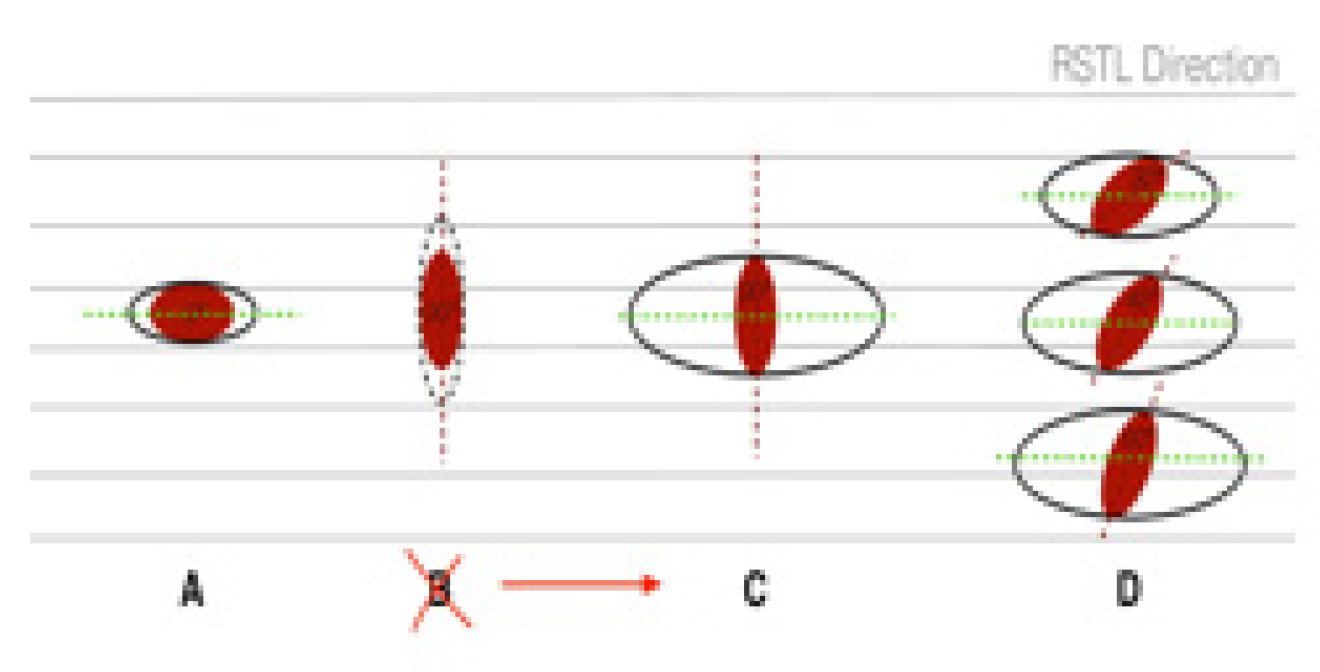

Figure 3 summarizes some very common situations in which, to different angles between the major axis of the lesion and the RSTL, correspond different sizes and shapes of the standard elliptical excision. In

Figure 3A, the longitudinal axis of the lesion is parallel to RSTL, therefore, the excision of healthy tissue surrounding the lesion is minimal. Case shown in

Figure 3B is unfavorable due to the lesion being perpendicular to RSTL, therefore, the excision is performed as shown in 3C, where the amount of healthy tissue sacrificed is far more extensive.

Figure 3D illustrates some intermediate between cases A and C.

The applicability of this technique depends on the initial direction of the skin lesion in relation to RSTL, and this aspect strongly affected the selection of the patients in the present study.

Fifteen patients with skin lesions had a complete excision of various skin lesions without need for skin graft of flap and the postoperative course was uneventful up to 6 months after surgery. The degree of patients’ satisfaction with the maturing scar was high.

Based on geometrical considerations, the possible advantages of using the parallelogram technique can be summarized as:

Reduction of the healthy area that is sacrificed in wider excision margins

Reduction of the distance between edges and spreading of tension in 2 equidistant points

Reduction of the theoretical length of the scar, with increasing benefit going from 45° to 90° of the orientation angle between the lesion and the RSTL

Slight rotation of the initial direction of the lesion towards the RSTL

During the surgery we clinically observed:

Ability to perform direct wound closure that may otherwise need a higher step in the reconstruction ladder such as skin graft or a flap

Orientation of the resultant scar toward RSTL

Reduction of the operating time

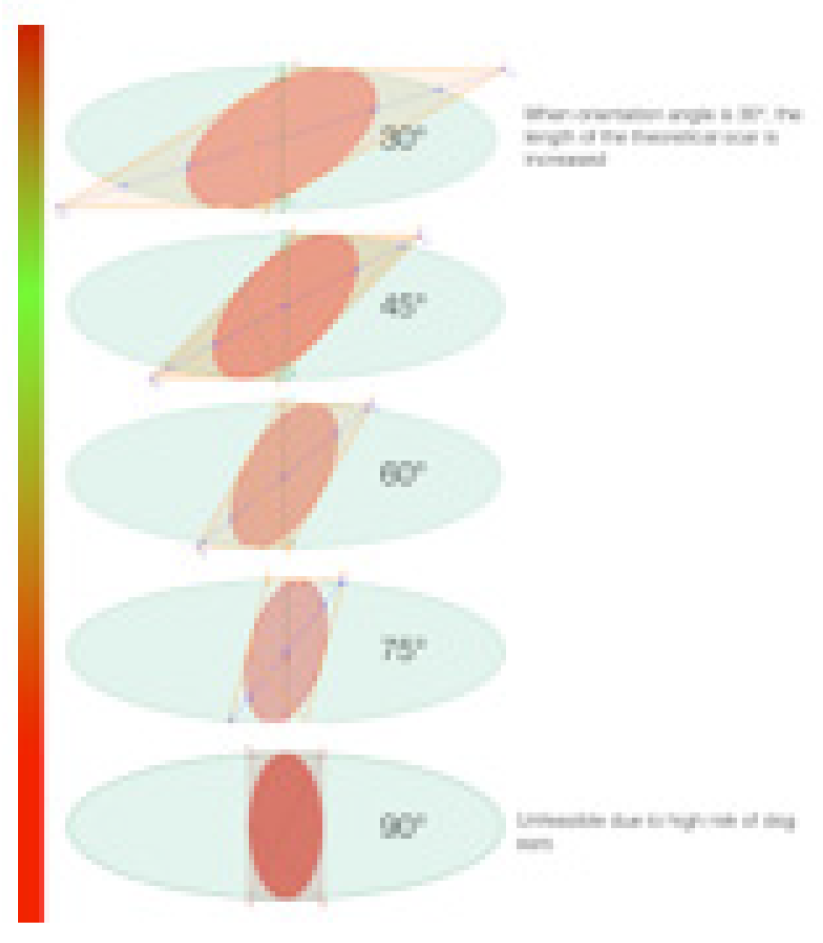

However, the extent of the advantages discussed above is dependent on the orientation angle of the lesion to the RSTL. In fact, similar to the Z-plasty1,2,3, in which angles are crucial in defining the benefits of the technique, our parallelogram excision has shown to be more suitable when applied to orientation angles within 45 and 60 degrees.

Geometrically speaking, the overall benefits of using parallelogram increase as the orientation angle goes from 40 to 90 degrees, but from 60 to 90 degrees these benefits are limited from the behavior of the skin, due to high risk of dog ears.

For these reasons we strongly suggest using the parallelogram technique in lesions with the orientation angle between 40 and 60 degrees, which have the best balance between geometrical benefits and low risk of dog ears onset as shown in

Figure 4.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, where indicated, the parallelogram excision technique appears to be a good option for excision and primary closure of skin lesions without compromising excision margins and achieving a superior aesthetic result compared to elliptic excision. Furthermore, it avoids skin graft or loco-regional flap donor site morbidity and reduces the operative time.

All patients who underwent this excision method had excellent healed final scars and were satisfied with the results.

Author Contributions

Francesco Costa: this Author helped to plan the study, make data analysis and write the paper, this is the Corresponding Author Filippo Boriani: this author helped to plan the study, make data analysis and write the paper. Syed Haroon Ali Shah: this Author leaded the operative section and helped to write the paper. Jeyaram Srinivasan: this Author helped to plan the study and write the paper, providing coauthors with a general supervision. Francesco Costa and Filippo Boriani coauthored as first authors. All Authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript. No funding or conflict of interest to mention for any authors.

Declaration of interest statement

None

References

- Thorne C, Chung K, Gosain A, Guntner G, Mehrara, B. Grabb and Smith's plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

- Neligan, Peter, and James Chang. Plastic Surgery (Principles). Elsevier, 2012.

- Hove CR, Williams EF, Rodgers BJ. Z-plasty: a concise review. Facial Plast Surg. 2001;17:289–294.

- Gottlieb LJ, Krieger LM. From the reconstructive ladder to the reconstructive elevator. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;93:1503–1504.

- Erba P, Orgill DP. Discussion. The new reconstructive ladder: modifications to the traditional model. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011;127 Suppl 1:213S–214S.

- Gottlieb LJ, Krieger LM. From the reconstructive ladder to the reconstructive elevator. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;93:1503–1504.

- Chu HJ, Son DG, Kwon SY, Kim JH, Han KH. Characteristics of wound contraction according to the shape and antomical regions of the wound in porcine model. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 38: 576-84.

- Wilhelmi BJ, Blackwell SJ, Phillips LG. Langer’s lines: to use or not to use. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999; 104: 208-14.

- Borges AF. Relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) versus other skin lines. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984; 73: 144-50.

- Borges AF. Relaxed skin tension lines. Dermatol Clin 1989; 7: 169-77.

- Parrett BM, Pribaz JJ. Lower extremity reconstruction. Rev Med Clin Condes 2010; 21:66–75.

- Oganesyan G, Jarell AD, Srivastava M, et al. Efficacy and complication rates of full-thickness skin graft repair of lower extremity wounds after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2013;9:1334–1339.

- Paul SP. “Halo” grafting—a simple and effective technique of skin grafting. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:115–119.

- Behan FC. The keystone design perforator island flap in reconstructive surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:112–120.

- Dixon AJ, Dixon JB. Reducing opposed multilobed flaps results in fewer complications than traditional repair techniques when closing medium-sized defects on the leg after excision of skin tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:935–942.

- Miyamoto S, Kayano S, Fujiki M, et al. Early mobilization after free-flap transfer to the lower extremities: preferential use of flowthrough anastomosis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:e127.

- Paul SP. Biodynamic Excisional Skin Tension (BEST) lines: revisiting Langer’s lines, skin biomechanics, current concepts in cutaneous surgery, and the (lack of) science behind skin lines used for surgical excisions. J Dermatol Res. 2017;2:77–87.

- Maranda EL, Heifetz R, Cortizo J, et al. Kraissl lines—a map. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1014.

- Paul SP, Matulich J, Charlton N. A new skin tensiometer device: computational analyses to understand biodynamic excisional skin tension lines. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30117.

- Daly CH, Odland GF. Age-related changes in the mechanical properties of human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:84–87.

- Langer K, "Zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Haut. Über die Spaltbarkeit der Cutis". Sitzungsbericht der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Wiener Kaiserlichen Academie der Wissenschaften Abt. 44 (1861).

- Escoffier C, de Rigal J, Rochefort A, et al. Age-related mechanical properties of human skin: an in vivo study. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:353–357.

- Paul SP. Revisiting Langer’s lines, introducing BEST lines, and studying the biomechanics of scalp skin. Spectrum Dermatologie. 2017;2:8–11.

- Lanir Y. A structural theory for the homogeneous biaxial stress-strain relationships in flat collagenous tissues. J Biomech. 1979;12:423–436.

- Barbenel JC. Identification of Langer’s lines. In: Serup J, Jemec GBE, eds. Handbook of Non-invasive Methods and the Skin. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press; 1995:341–344.

- Paul SP. Biodynamic Excisional Skin Tension lines for excisional surgery of the lower limb and the technique of using parallel relaxing incisions to further reduce wound tension. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017;5:e1614.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).