Submitted:

17 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

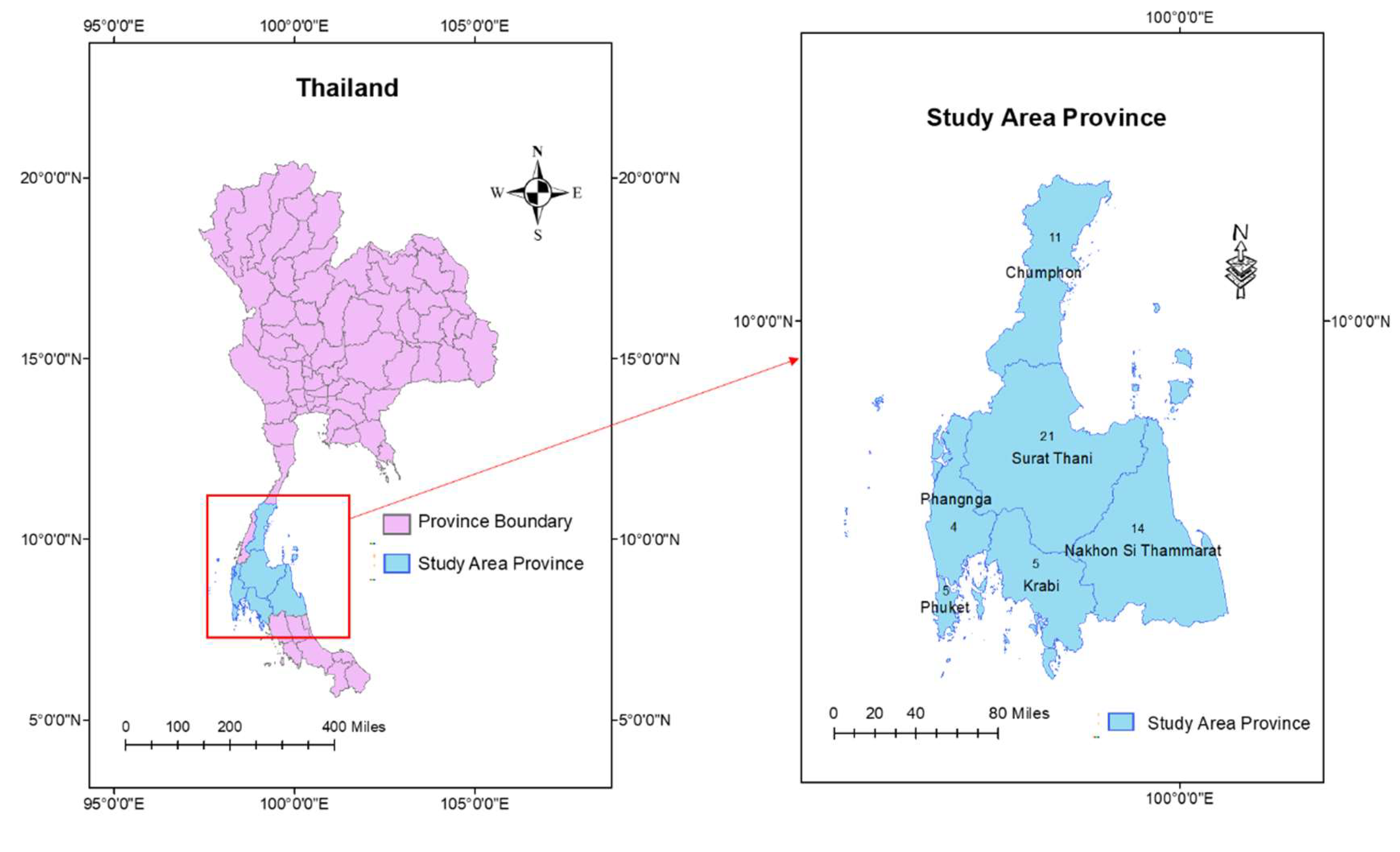

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative methods

2.1.1. Population and sample

2.1.2. Instruments of quantitative approach

2.1.3. Data analysis of quantitative

2.2. Qualitative methods

2.2.1. Study design and participation

2.2.2. Participant as the key informant

2.2.3. Guide of questionnaire for in-depth interview

2.2.4. Data collection of in-depth interview

2.2.5. Data analysis of qualitative approach

2.2.6. Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics information in quantitative method

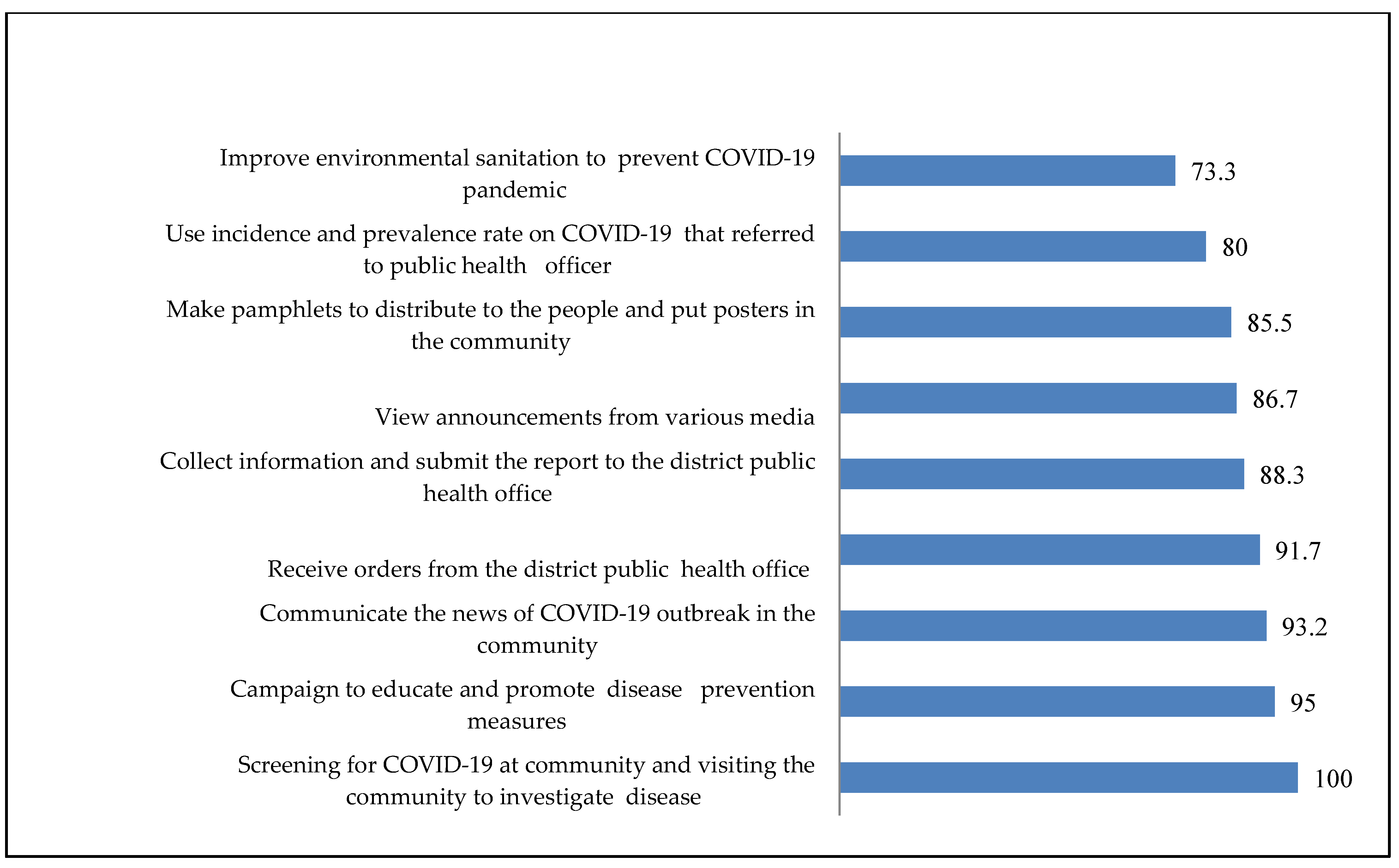

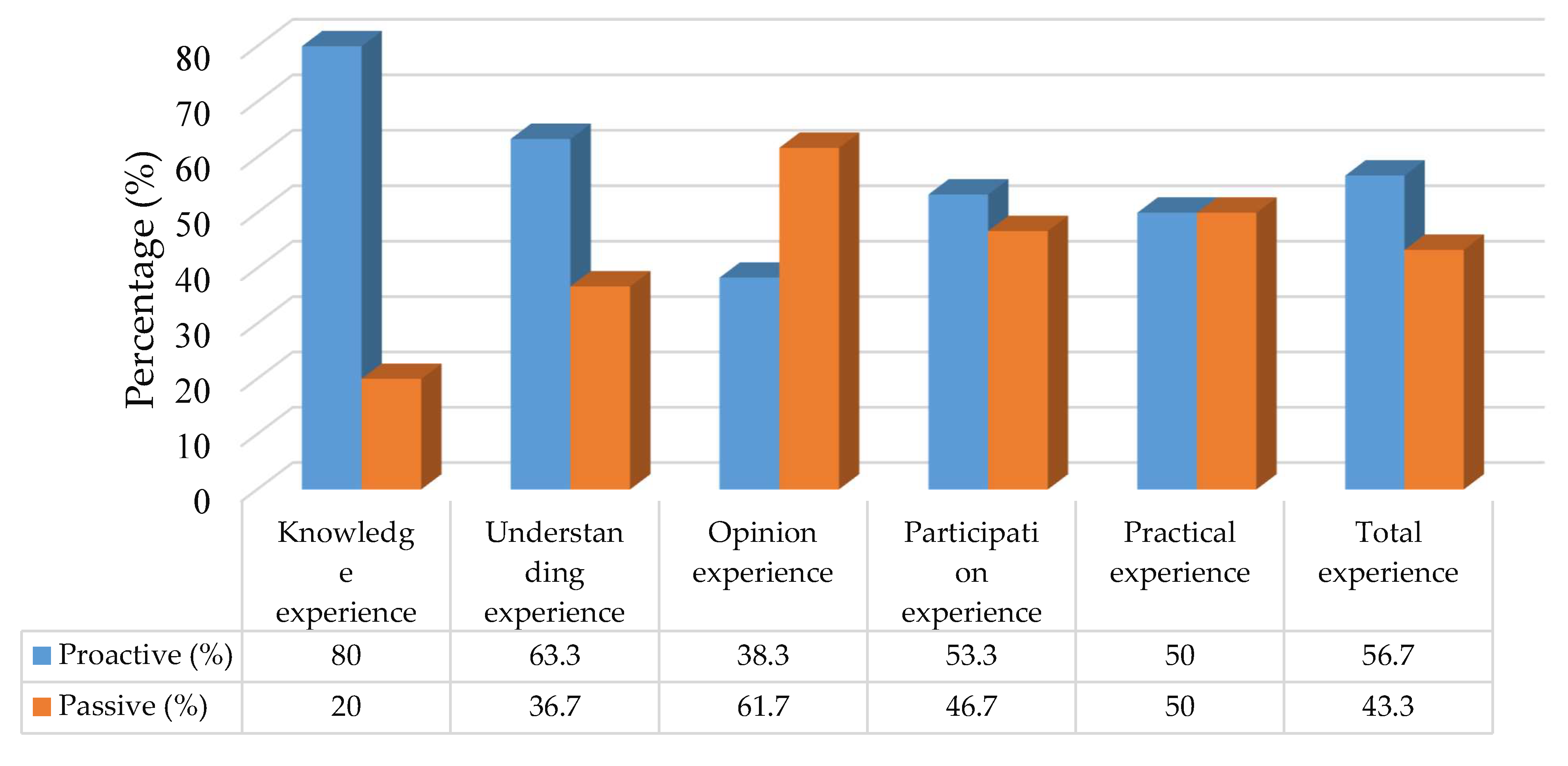

3.2. Level of PHO’s Experience to solve COVID-19 in upper southern region, Thailand

3.3. Predictor of the proactive practical experiences to solve COVID-19 among PHOs in upper southern region, Thailand.

3.4. The theme of PHOs’ experiences in solving COVID-19 from a qualitative study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thai Ministry of Public Health. Strategic Plan: Covid-19 Strategy: Managing the new wave of the Covid-19 Epidemic Ministry of Public Health, January 2021. Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/eng/file/main/en_Thailand%20Covid-19%20plan_MOPH_2021.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- World Health Organisation. COVID-19 Situation, Thailand; 2022. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/thailand/2022_01_26_tha-sitrep-220-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=bf4f76d6_3 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Tuangratananon, T.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Panichkriangkrai, W; Pudpong, N.; Patcharanarumol, W. et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on integrating NCDs into primary healthcare in Thailand: a mixed method study. Health Res. Policy Sys. 2021, 19, 139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaprawat, P.; Greene, M.T.; Saint, S.; Kasatpibal, N.; Fowler, K.E.; Apisarnthanarak, A. Status of hospital infection prevention practices in Thailand in the era of COVID-19: Results from a national survey. Am J. Infect. Control. 2022, 50, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siree, O. Praise of the Thai medical team!! Hundred days to fight “COVID”, the number of patients continues to decline. The Bangkok Insight. 2020. Available online: https://www.thebangkokinsight.com/340658/ (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Pipattanachat, V. Role of Health Professions Career by the Community Health Professions Act, B.E. 2556 (2013). Pub. Health & Health Laws J, 2016; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thai Ministry of Public Health. Guidelines for surveillance and investigation of the novel coronavirus disease 2019. DDC EOC; 2020. Retrieved June 09, 2023 from. Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/file/g_km/handout004_26022020.pdf.

- Roth, W.M.; Jornet, A. Towards a theory of experience. Science Education. 2014, 98, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libertus, K.; Needham, A. Teach to reach: The effects of active vs. passive reaching experiences on action and perception. Vision Res. 2010, 50, 2750–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, D. Experiences of registered nurses as managers and leaders in residential aged care facilities: a systematic review. Int J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2011, 9, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- Harvey, K.; Horton, L. Bloom’s Human Characteristics and School Learning. The Phi Delta Kappan 1977, 59, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Laverty, S.M. Hermerneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: a comparison of historical and methodological considerations. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2003, 2, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In Cooper H. (Ed.), Research designs. Amarican Psychological Association, 2012, 2.

- Suwanbamrung, C.; Kaewsawat, S. Public Health Students’ Reflection regarding the First Case of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in a University, Southern Thailand. J. Health Care and Res. 2020, 1, 1,182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U.; Lardorff, E.V.; Steinke, I. A companion to qualitative research. SAGE Publications. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rerkswattavorn, C.; Chanprasertpinyo, W. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in a Population Under Community-Wide Containment Measures in Southern Thailand. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 6391–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewchandee, C.; Hnuthong, U.; Thinkan, S.; Rahman, S.; Sangpoom, S.; Suwanbamrung, C. The experiences of district public health officers during the COVID-19 crisis and its management in the upper southern region of Thailand: A mixed methods approach. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triukose, S.; Nitinawarat, S.; Satian, P.; Somboonsavatdee, A.; Chotikarn, P.; Thammasanya, T.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Sudhinaraset, N.; Boonyamalik, P.; Kakhong, B.; Poovorawan, Y. Effects of public health interventions on the epidemiological spread during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangpoom, S.; Adesina, F.; Saetang, J.; Thammachot, N.; Jeenmuang, K.; Suwanbamrung, C. Health workers’ capability, opportunity, motivation, and behavior to prevent and control COVID-19 in a high-risk district in Thailand. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2023, 74, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ogboghodo, E.O.; Osaigbovo, I.I.; Obaseki, D.E.; Iduitua, M.T.N.; Asamah, D. , Oduware, E. et al. Implementation of a COVID-19 screening tool in a southern Nigerian tertiary health facility. PLOS Glob. Public Health. 2022, 2, e0000578. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.J.; Kurscheid, J.; Mationg, M.L.; Williams, G.M.; Gordon, C.; Kelly, M. et al. Health-education to prevent COVID-19 in schoolchildren: a call to action. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertshuis, S.; Jung, M.; Cooper-Thomas, H. Preparing Students for Higher Education: The Role of Proactivity. Int. J. Learn High Educ. 2014, 26, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Geberemariyam, B.S.; Donka, G.M.; Wordofa, B. Assessment of knowledge and practices of healthcare workers towards infection prevention and associated factors in healthcare facilities of West Arsi District, Southeast Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, J.; Diress, G.; Adane, S. Infection prevention knowledge, practice, and its associated factors among healthcare providers in primary healthcare unit of Wogdie District, Northeast Ethiopia, 2019: a cross-sectional study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammed, O.A.; Aldwihi, L.A.; Alragas, A.M.; Almoteer, A.I.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Alqahtani, N.M. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Associated With COVID-19 Among Healthcare Workers in Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 643053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.C.C.; Wong, S.C.; To, K.K.W.; Ho, P.L.; Yuen, K.Y. Preparedness and proactive infection control measures against the emerging novel coronavirus in China. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, C.; Shamsudin, F.M.; Zin, M.L.; Ramalu, S.S.; Hassan, Z. The influence of safety management practices on safety behavior: A study among manufacturing SMES in Malaysia. Int. J. Sup. Chain Mgt. 2016, 5, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, P.; Karakonstantis, S.; Mathioudaki, A.; Sourris, A.; Papakosta, V.; Panagopoulos, P. et al. Knowledge and Perceptions about COVID-19 among Health Care Workers: Evidence from COVID-19 Hospitals during the Second Pandemic Wave. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2021, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olateju, Z.; Olufunlayo, T.; MacArthur, C.; Leung, C.; Taylor, B. Community health workers experiences and perceptions of working during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lagos, Nigeria—A qualitative study. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0265092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, Z.; Singh, V.; Supehia, S.; Mohan, L.; Gupta, P.K.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, S. Expectations of healthcare personnel from infection prevention and control services for preparedness of healthcare organisation in view of COVID-19 pandemic. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2021, 77 (Suppl 2), S459–S465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Taiwo, O.O.; Barraza-Roppe, B.; Lemus, M. Using Community Health Workers to Prevent Infectious Diseases in Women. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004; 10, e11. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, B.S.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Harasym, P.; Dumanski, S.M.; Fiest, K.; Graham, I.D. et al. Healthcare workers’ perception of gender and work roles during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e056434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regenold, N.; Vindrola-Padros, C. Gender Matters: A Gender Analysis of Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during the First COVID-19 Pandemic Peak in England. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murman, D.L. The Impact of Age on Cognition. Seminars in hearing 2015, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amzat, J.; Aminu, K.; Kolo, V.I.; Akinyele, A.A.; Ogundairo, J.A.; Danjibo, M.C. Coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria: Burden and socio-medical response during the first 100 days. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganyani, T.; Kremer, C.; Chen, D.; Torneri, A.; Faes, C.; Wallinga, J.; Hens, N. Estimating the generation interval for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on symptom onset data, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25, 2000257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Personal data | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (31.7) |

| Female | 41 (68.3) |

| Age (Year old ) (S.D.) = 35.57 (11.61), Min = 22, Max = 59 | |

| < 27 | 20 (33.3) |

| ≥ 27 | 40 (66.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Single/divorced/separated | 29 (48.3) |

| Married | 31 (51.7) |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 48 (86.7) |

| Master’s degree | 12 (13.3) |

| Public health position | |

| Public Health Scholar | 38 (63.3) |

| Public Health Practitioner | 22 (36.7) |

|

Length of time worked in the current position (S.D.) = 12.32 (12.02), Min = 1, Max = 38 | |

| ≤ 6 year old | 30 (50.0) |

| > 6 year old | 30 (50.0) |

| COVID-19 patients in the area | |

| No | 49 (75.0) |

| Yes | 11 (25.0) |

| Factors | Proactive practical experiences (n=30) | ORa | ORbadj | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 9 | 0.86 | 1.52 | 1.04-2.21 | 0.029* |

| Female | 21 | 1.00 | |||

| Age (years old) | |||||

| <27 | 11 | 1.35 | 1.69 | 1.16-2.48 | 0.006* |

| ≥27 | 19 | 1.00 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single/divorced/separated | 12 | 0.51 | 1.69 | 1.16-2.48 | 0.006* |

| Married | 18 | 1.00 | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 24 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 1.02-2.20 | 0.040* |

| Master’s degree | 6 | 1.00 | |||

| Position for work | |||||

| Public Health Practitioner | 23 | 3.28 | 1.69 | 1.16-2.48 | 0.006* |

| Public Health Scholar | 7 | 1.00 | |||

| Length of time worked in the current position | |||||

| > 6 year old | 17 | 1.71 | 0.93 | 0.60-1.46 | 0.829 |

| ≤ 6 year old | 13 | 1.00 | |||

| Presence of COVID-19 patients in the area | |||||

| No have | 25 | 1.25 | 1.24 | 0.84-1.82 | 0.301 |

| Have | 5 | 1.00 | |||

| Knowledge experience | |||||

| Proactive | 24 | 1.00 | 1.65 | 1.13-2.40 | 0.008* |

| Passive | 6 | 1.00 | |||

| Understanding experience | |||||

| Proactive | 23 | 3.76 | 1.47 | 1.01-2.14 | 0.045* |

| Passive | 7 | 1.00 | |||

| Opinion experience | |||||

| Proactive | 7 | 1.22 | 1.48 | 1.01-2.21 | 0.046* |

| Passive | 23 | 1.00 | |||

| Participationexperience | |||||

| Proactive | 24 | 11.00 | 1.58 | 1.08-2.31 | <0.017* |

| Passive | 6 | 1.00 | |||

| Sub-themes | Meaning | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptions about the pandemic and awareness of COVID-19. | Significant impact on the world.

|

It was a pretty serious outbreak because there was no specific cure and it happened so quickly. In the infected area, there is a spread of COVID-19 infection among those who returned from travel and reunited with people at home (PHO1). |

| COVID-19’s knowledge leads to standard practice and guidelines. | Educating people on preventive measures and control strategies:

|

It began with forming a team with a network to create a Facebook and video on the online application to publicise and educate people in various places, such as mosques, schools, government service facilities, and hotels. Distributing leaflets, and pasting posters in the community as an education program. This highlights the beginning of the program’s implementation process (PHO5). Preventing and controlling COVID-19 in quarantine areas, promoting mask-wearing, and social distancing in the public” (PHO1). |

| A careful understanding of COVID-19 solutions is necessary | People must comprehend the public health officer’s methods for preventing COVID-19.

|

During the first phase of the pandemic, people misunderstood the prevention guidelines and did not understand quarantine procedures. They entered the village without notifying their public health officer and bypassed checkpoints set up by primary care units, entering the community through natural channels. It is crucial to enhance people’s understanding in the community to effectively prevent COVID-19” (PHO6). |

| Recognizing the nature and severity of COVID-19 | Understanding the symptoms associated with the virus:

|

As previously mentioned, “COVID-19 is a severe disease that can cause damage to the lungs and lead to death. Although death may not occur, individuals may still experience lasting symptoms that affect their daily lives. Therefore, if an infection does occur, it must be taken care of to prevent potential complications (PHO4). |

| COVID-19 impacts lifestyle and quality of life | Individuals returning from high-risk areas must be quarantined and separated from their families. Not visiting others while sick |

It has an impact on the way of life of people in the area, with long-term effects on the economy, society, and the livelihoods of people in all areas (PHO5). |

|

Respond to and trust public health officials to solve COVID-19 |

To trust and cooperate with public health officials to combat COVID-19. | A successful process involves participation from all sectors. When a disease outbreak occurs, everyone tends to rely solely on public health officials to handle it. However, with the prevalence of COVID-19, all sectors must contribute to prevention and control efforts to improve outcomes. If public health officials are the only ones responsible, controlling the disease becomes challenging. Making everyone a stakeholder in preventing and controlling the disease is crucial (PHO 5). |

| Establishment of a collaborative network of stakeholders to address the COVID-19 pandemic. | The cooperation between various stakeholders, such as government agencies, private organizations, and the local community, to tackle the challenges posed by COVID-19. | The network of communities begins at the district level, including the district public health office, sub-district health center, village head, and village health volunteer, all of whom participate in the collaborative effort. Coordination with the network of communities involves writing letters to request support and assistance to fill any remaining gaps (PHO 7). |

| Stakeholders’ contribution to spreading awareness and monitoring COVID-19 treatment |

|

If companies provide alcohol, it can be distributed to schools, community organizations for funeral use, and placed in various locations in the community. It can also serve as a model for villagers. Knowledge is shared by transmitting it to over 130 community organizations, and each responsible community organization will then pass on the knowledge about COVID-19 prevention (PHO2). |

| COVID-19 screening and referral checkpoints. | Establishing checkpoints in various locations, such as schools, hotels, temples, mosques, and village extraction points. | If someone in quarantine has a suspected disease, we screen them and send them to the district hospital for investigation. For the common people in the community, there were checkpoints at the screening points in the village. This indicates the importance of taking proactive measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the community (PHO3). I have been involved in every aspect of combating COVID-19, from setting up screening and referral checkpoints in schools, hotels, temples, and mosques to working together to prevent the spread of the disease, providing knowledge, monitoring and taking care of high-risk groups in isolation for 14 days, and searching for infected patients (PHO6). |

| Collaboration and sharing opinions to improve solutions | The process of working together and gathering ideas from different communities to find solutions to problems. | We work with network leaders, the local administration organization head, and the district public health office to ensure adequate supplies. The local administration organization will provide support for food, and the primary care unit of the public health office will continue to provide COVID-19-related knowledge to the community (PHO8). |

| Conducting community examinations, follow-ups, and reporting | The process of implementing an operational plan to monitor and track individuals who may have been exposed to COVID-19 in the community. | The operational plan creates group lines for each group in the community and brings people at risk into the group line to report symptoms for 14 days. If there is no confirmed case, that person will be immediately removed from the group line (PHO1). |

| Today’s practical prevention and control lead to future solutions | Proactive plan | At first, there is a passive plan, but when there is a COVID-19 patient, the plan changes to a proactive plan, such as the meeting of the district committee every week to adjust the plan, setting up additional checkpoints to screen employees. For the second round, there are meetings with all stakeholders, such as the local government and the police department, to solve the problem (PHO5). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).