1. Introduction

Femtosecond nonlinear laser-stimulated emission

spectroscopy of disperse media, when the medium under study is a micron-sized

particle which is luminous due to either laser-induced fluorescence (FLIF) of

the active substance or because of the recombination of optical breakdown

plasma (FIBS) generated in particle volume, has received recently a new impetus

in its development due to the use of femtosecond laser sources. High intensity

achieved in such ultrashort laser pulses provides for the overcoming the energy

threshold for nonlinear-optical processes of multiphoton laser absorption and

optical breakdown of matter inside a particle and enables for reliable optical

signal receiving from emitting particles at considerable long ranges in the

atmosphere using the LiDAR method [1].

At sufficiently high irradiation intensities, far

above the optical breakdown threshold Ib , a laser-induced

plasma can arise in aqueous medium [2], which

produces spectrally-resolved light emission of elemental plasma components as a

result of radiative recombination of generated free electrons with ions. For

example, in an aqueous solution of table salt (sodium chloride) the spectral

doublet of sodium with wavelengths near 590 nm possesses the highest emission

intensity, which is reported in many experiments on laser-induced femtosecond

spectroscopy of model marine aerosol [3–10].

Importantly, the threshold for laser plasma formation in a spherical

microparticle in addition to the physical and chemical properties of particle

substance depends on the parameters of the laser radiation (wavelength, pulse

duration) also. According to the published data [3,11,12],

the threshold for optical breakdown in a water microdroplet exposed to a

femtosecond pulse of Ti:Sapphire laser (λ

≈ 800 nm) is about Ib

≈ 1011 W/cm2,

which is two orders above the breakdown intensity of similar water droplets

placed in air and illuminated by a nanosecond laser pulse at the wavelength of

second harmonic of Nd:YAG-laser (λ =

532 nm), i.e. Ib ≈ 2.5⋅109 W/cm2 [13], and simultaneously by two orders of magnitude

lower than the breakdown threshold of pure air (without particles) when Ib

≈ 5⋅1013

W/cm2 [14].

If the incident laser radiation has a sub-threshold

breakdown intensity, I < Ib , but a droplet contains

a fluorescent dye, it is quite likely that the laser stimulated fluorescence

can be excited. For example, for the greenish-yellow fluorescent dye uranine,

the center wavelength of a wide spectral region of fluorescence lies near 525

nm, while the center of the absorption band is located near 500 nm. Obviously,

since the photon energy in a stimulating IR laser radiation is usually less

than the energy gap between the absorption levels of a dye molecule, the

two-photon absorption fluorescence (TPA) through main radiative transition of

uranine will have the highest probability in such spectral range. As a result,

under the TPA a dye molecule absorbs two photons of incident radiation in a

single quantum event (at the same time instant) and then releases its lower

excited vibrational sublevel through a radiative transition to the ground

singlet state.

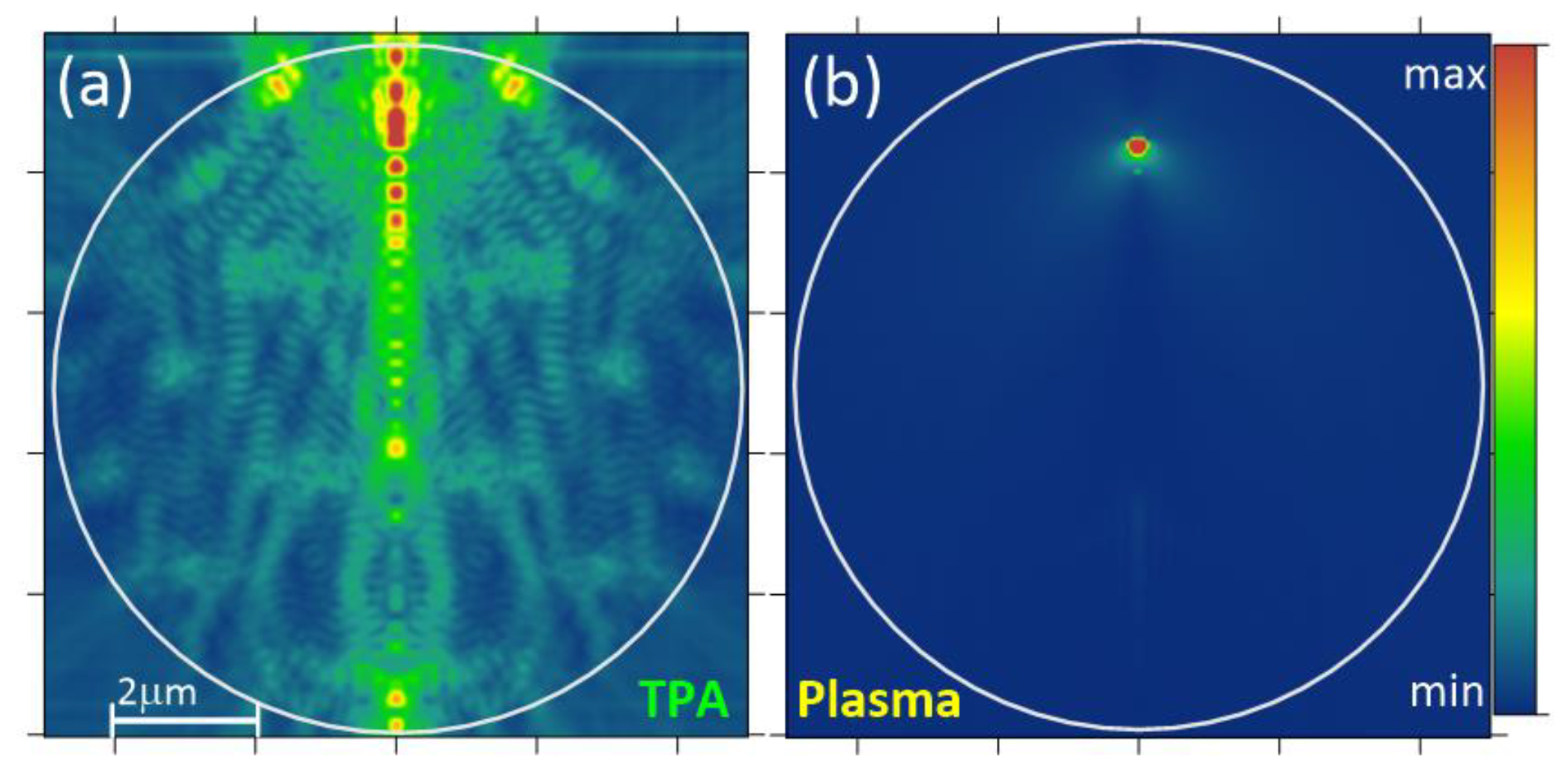

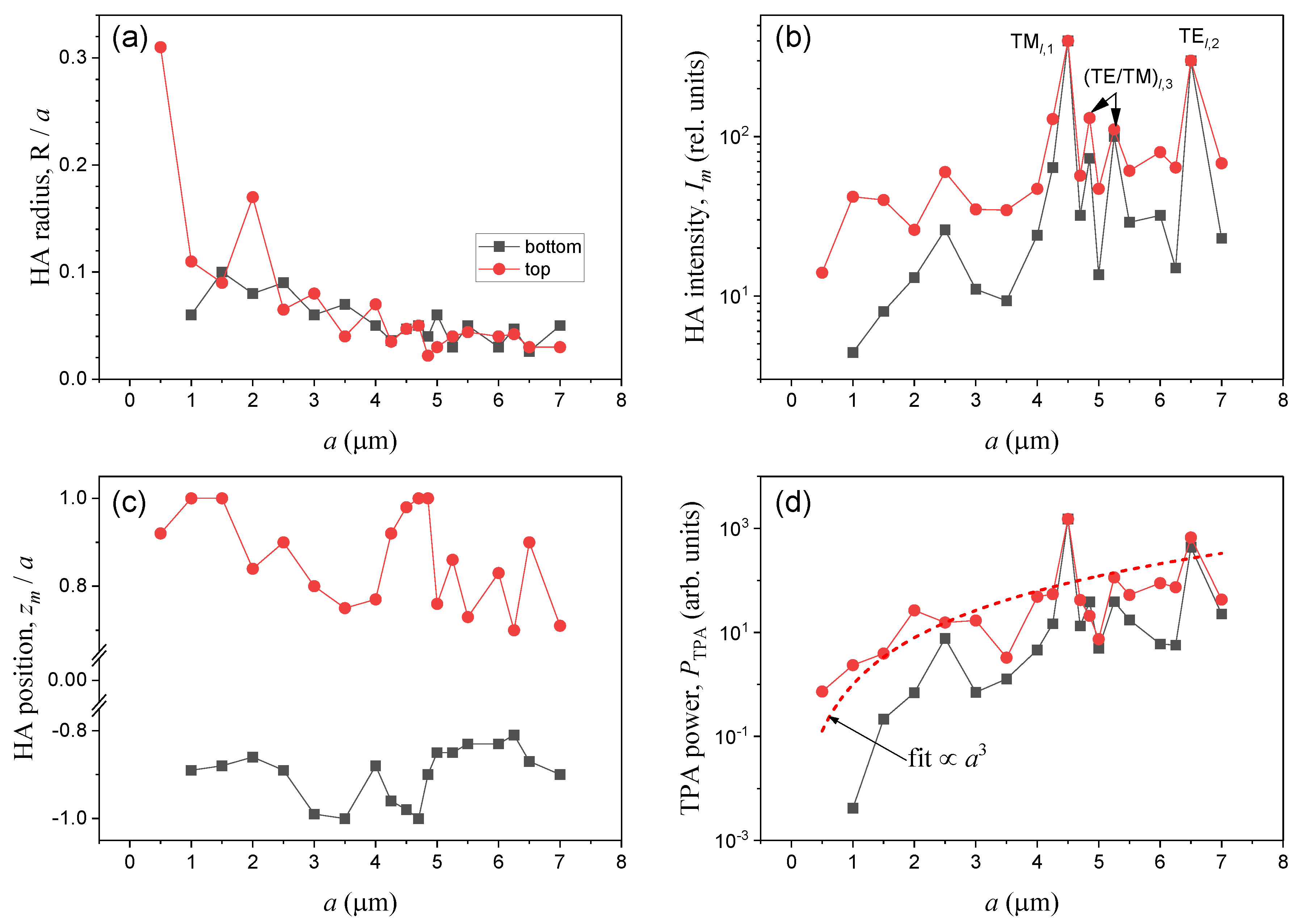

Secondary radiation arising in a droplet volume

(plasma emission, or TPA fluorescence) is localized mainly in the vicinity of

the internal focuses (“hot areas”) and by exiting the particle experiences

multiple refractions and reflections on the spherical liquid-air interface.

This causes a nonuniform character of the angular distribution of emission far

from the particle (the receiver area). Besides, the particular shape of droplet

emission phase function is also influenced by the character of emission

mechanism, namely, the multiphoton-order ( m ) of the excitation process.

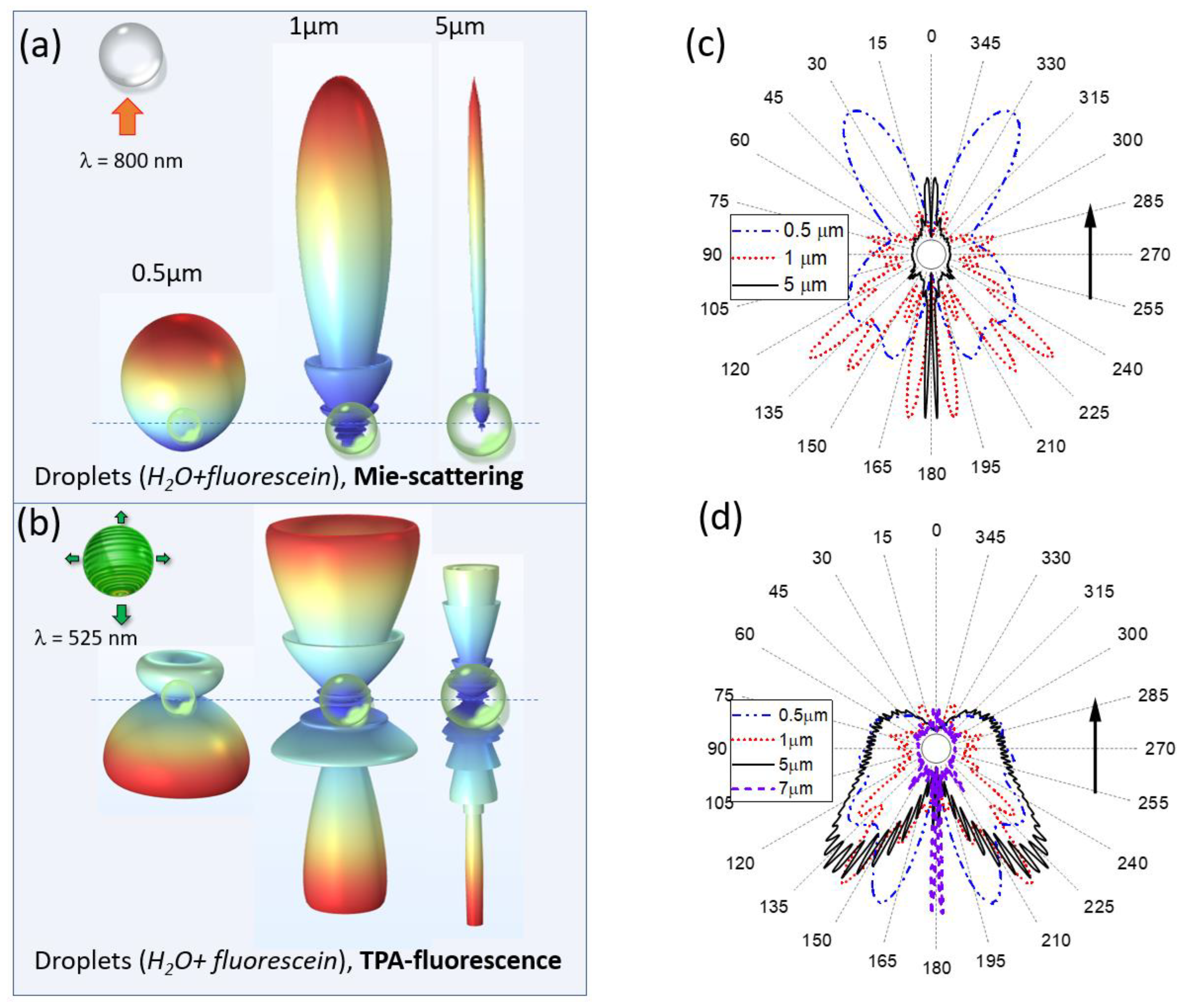

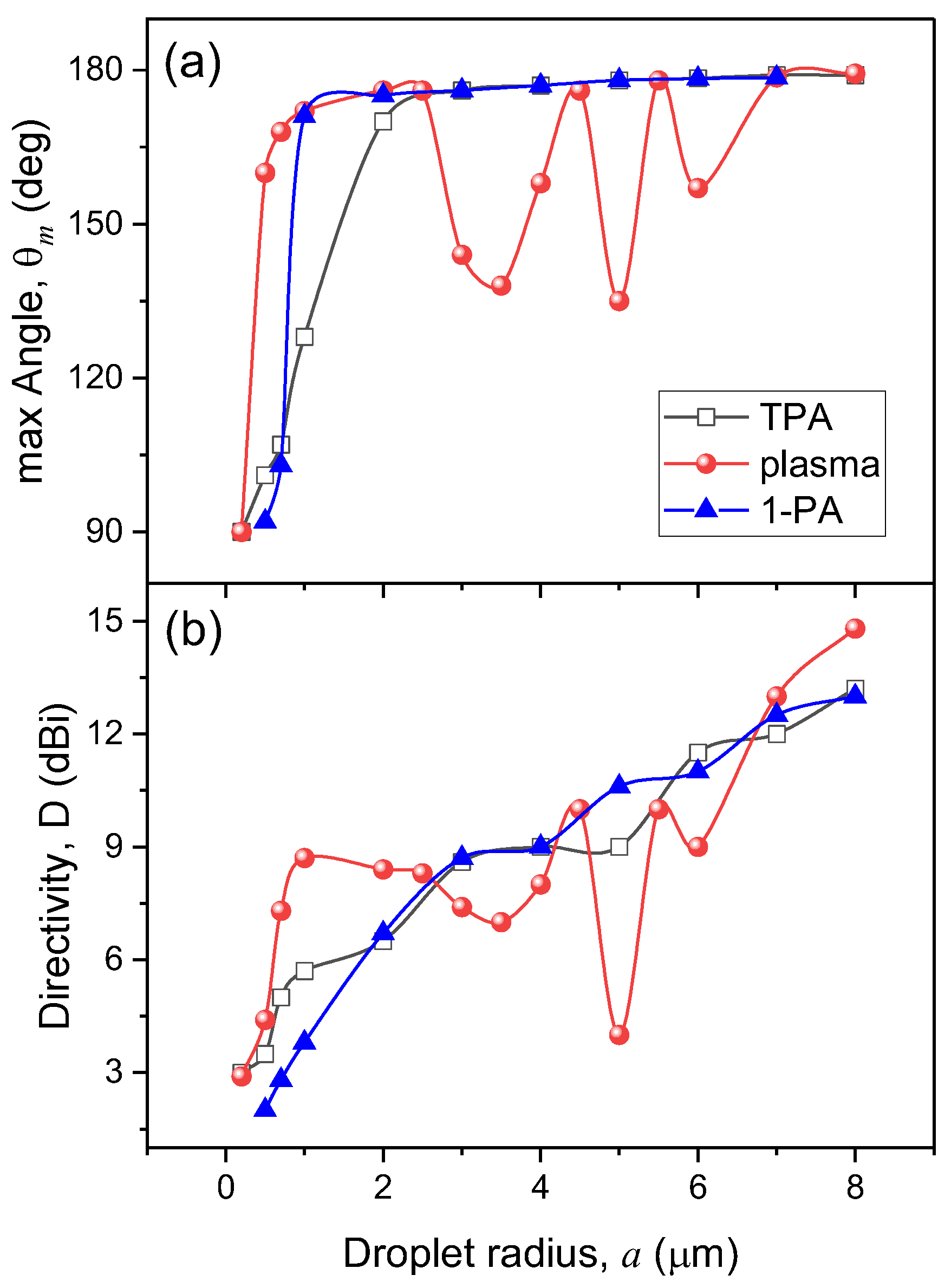

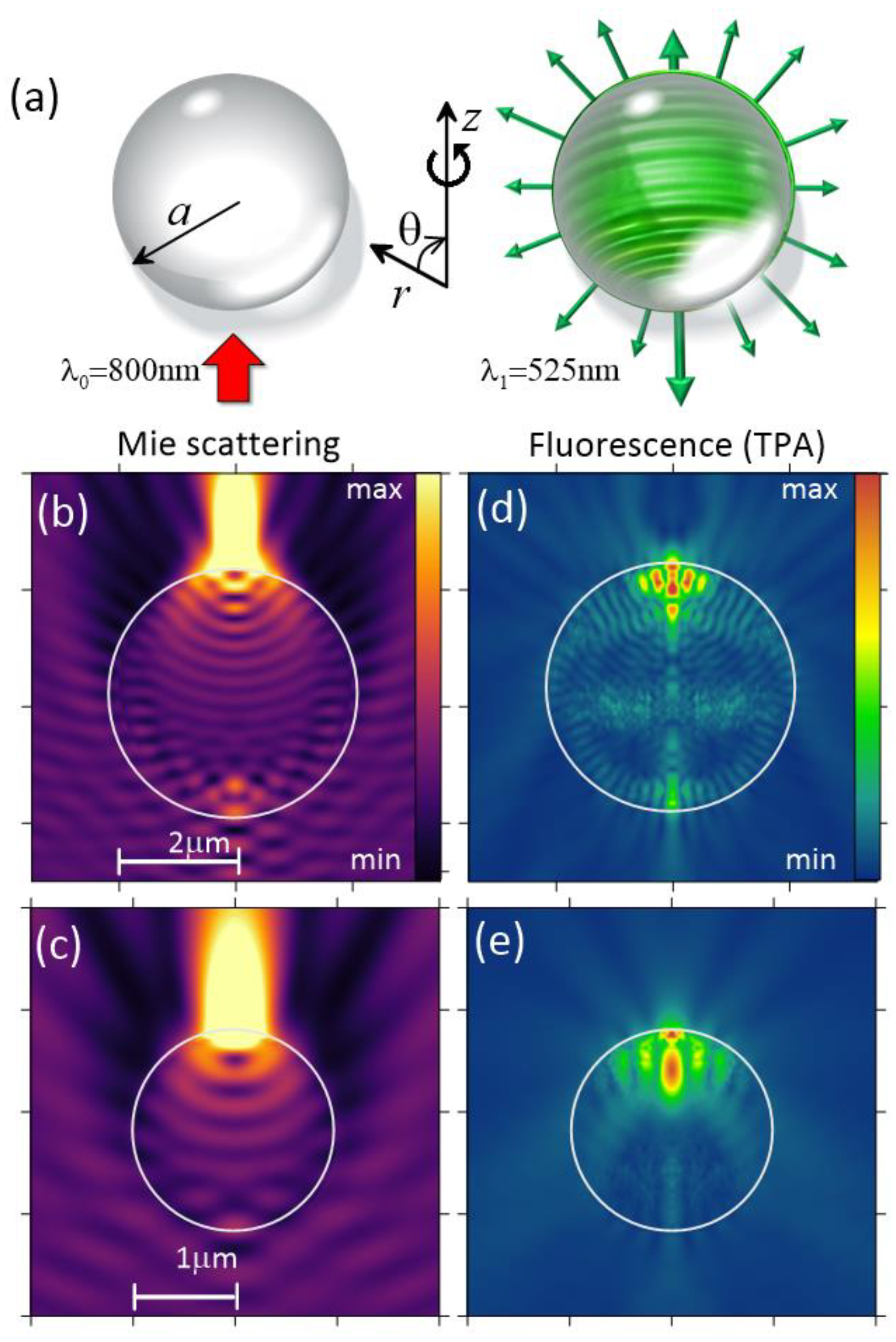

As shown earlier [3,10,15], the higher the

values of m , the more forward- backward-directed becomes the angular

distribution of nonlinear emission from spherical particles. Moreover, light

emission of sufficiently large water droplets (particle radius a

>> λ) is always characterized by

an anomalously enhanced backward emission intensity [16].

In Refs. [3,10]

the angular characteristics of multiphoton excited fluorescence in ethanol and

methanol droplets with the radius from 25 to 40 μm are studied experimentally

and theoretically. The droplets contain different dyes, coumarin 510 or

tryptophan, and are irradiated by a Ti:Sapphire laser pulse with duration of

about 100 fs and energy per pulse of the order of several microjoules. For

one-, two-, and three-photon excitation of fluorescence in microdroplets,

central laser wavelengths of 400, 850, and 1200 nm are used, respectively. The

main finding of these works is that the maximum fluorescence intensity of

droplets is observed in the backward direction, i.e., toward the direction of

incidence of the excitation pulse. Meanwhile, the ratio of fluorescence

intensities in the backward and transverse directions increases when the order

of multiphoton fluorescence excitation increases. A qualitative explanation of

this effect is given based on the reciprocity principle of light rays emitted

by fluorescence sources within a spherical particle. Numerical simulations

established a relationship between the observed intensity of particle

luminescence in the backward direction and the spatial localization of

fluorescence sources, which increases with increasing the parameter m. Later, a

similar effect was reported for non-spherical micro-objects, particularly in

clusters formed by several micrometer polystyrene (PS) microparticles

containing dry tryptophan [17].

In our previous work [15],

the spatial location, effective volume, and intensity of the excitation optical

field in the “hot areas” of a micron spherical droplet are calculated within

the Lorentz-Mie formalism. Particularly, by the method of geometric optics we

show that the shape of the angular distribution of fluorescence excited in a

spherical microparticle by laser radiation significantly depends on the

morphology of the particle, in particular on the specific location within the

droplet and the effective power of the fluorescence sources. If the most

intense of these sources is located near the shadow surface of the particle,

the inelastic scattering phase function is elongated in the backward direction

to the direction of laser pulse incidence. As the fluorescence source moves

toward the particle center, the emission asymmetry disappears. In addition, the

fluorescence emitted from the rear and front hemispheres of the droplet is

characterized by different angular spreading. These results indicate that the

size of aerosol particle as well as the specific type of nonlinear process

causing the secondary emission are the key parameters affecting the angular

structure of emission.

In present work, the development and dynamics of

two-photon excited fluorescence and plasma emission inside an aqueous dyed

spherical droplet is considered theoretically in particles exposed to a

high-power laser radiation. Based on the numerical solution of the Helmholtz

equation by means of the finite element method, the angular structure of the

secondary emission is simulated and studied in droplets with different sizes

that allows us to determine the directions of the maximal emission from the

particles in the far-field.

2. Materials and Methods

Consider the following problem. A spherical droplet

is placed in the air and illuminated by laser radiation with a wavelength λ0 = 800 nm. Either saline water

(NaCl solution) or a diluted aqueous solution of fluorescein (uranine,

C₂₀H₁₂O₅) is considered as liquid. The droplet is characterized by the radius a

and the refractive index n = 1.33 in the visible and near-IR spectral

region (Figure 1a). In this spectral

region we neglect linear light absorption of a liquid particle. As a result of optical

wave diffraction incident on dielectric sphere, inside it the regions with

increased optical intensity are formed which usually are termed as the “hot areas”

(HAs). These HAs offer favorable conditions for optical nonlinearity

manifestation of particulate substance and serve as the main sources of nonlinear

light emission. Light emitted from HAs experiences constructive/destructive interference

both inside and outside the particle provided by wave refraction and reflection

at the boundaries. The resulting stationary emission field at blue-shifted

wavelength λ1 is analyzed in

terms of angular intensity distribution in the far-field region.

From now on, we make several simplifications of the

problem under consideration. First, a stationary scattering problem is

considered as we reduce the dimensionality of the original problem to only two

spatial dimensions by assuming that all the optical fields (primary and

secondary) possess azimuthal symmetry. This reduction neglects only the

azimuthal field variation in the direction transverse to the direction of pump

radiation incidence but the angular emission structure along the polar angle θ is preserved.

The second problem simplification considers only a monochromatic

optical radiation for both the excitation optical field and the nonlinear

emission from the droplet. This assumption is based on the fact that, even in

the case of a high-power femtosecond pulse upon its filamentation in air and

supercontinual spectral broadening, the bulk of the optical energy is

transported in a fairly narrow spectral range near the central wavelength [18]. Consequently, in the problem of droplet

emission instead of a realistic wide-spectrum optical excitation one can

consider some artificial monochromatic radiation at certain effective

wavelength.

A similar approximation is adopted when modeling

the nonlinear optical emission from the particle, i.e., the spatial dynamics of

the optical field at only single wavelength from the emission spectrum is

considered. In the case of the breakdown plasma emission this approximation

corresponds to the receiving the optical signal from only one selected chemical

constituent of particle substance, e.g., sodium in a table salt solution. For the

situation with the multiphoton-excited fluorescence which is characterized by

broad spectrum of dye luminescence, the spectral averaging of the working

transition of the fluorophore molecule over energy sublevels as shown in [19] does not lead to critical errors in the

measured emission signal if the fluorescing particles are of the mesowavelength

scale ( a < 10 λ). Practically,

this means the absence of simultaneous excitation of several high-quality Mie resonances

(the "whispering gallery" modes [20])

within the broadband spontaneous fluorescence spectrum inside the

microparticle, which can significantly modify the angular distribution of the

emission. The requirement of the absence of strong resonances in the secondary

emission allows one neglecting the modification of quantum yield of spontaneous

dipole emission excited by the resonant field, which is known as the Purcell

effect [21].

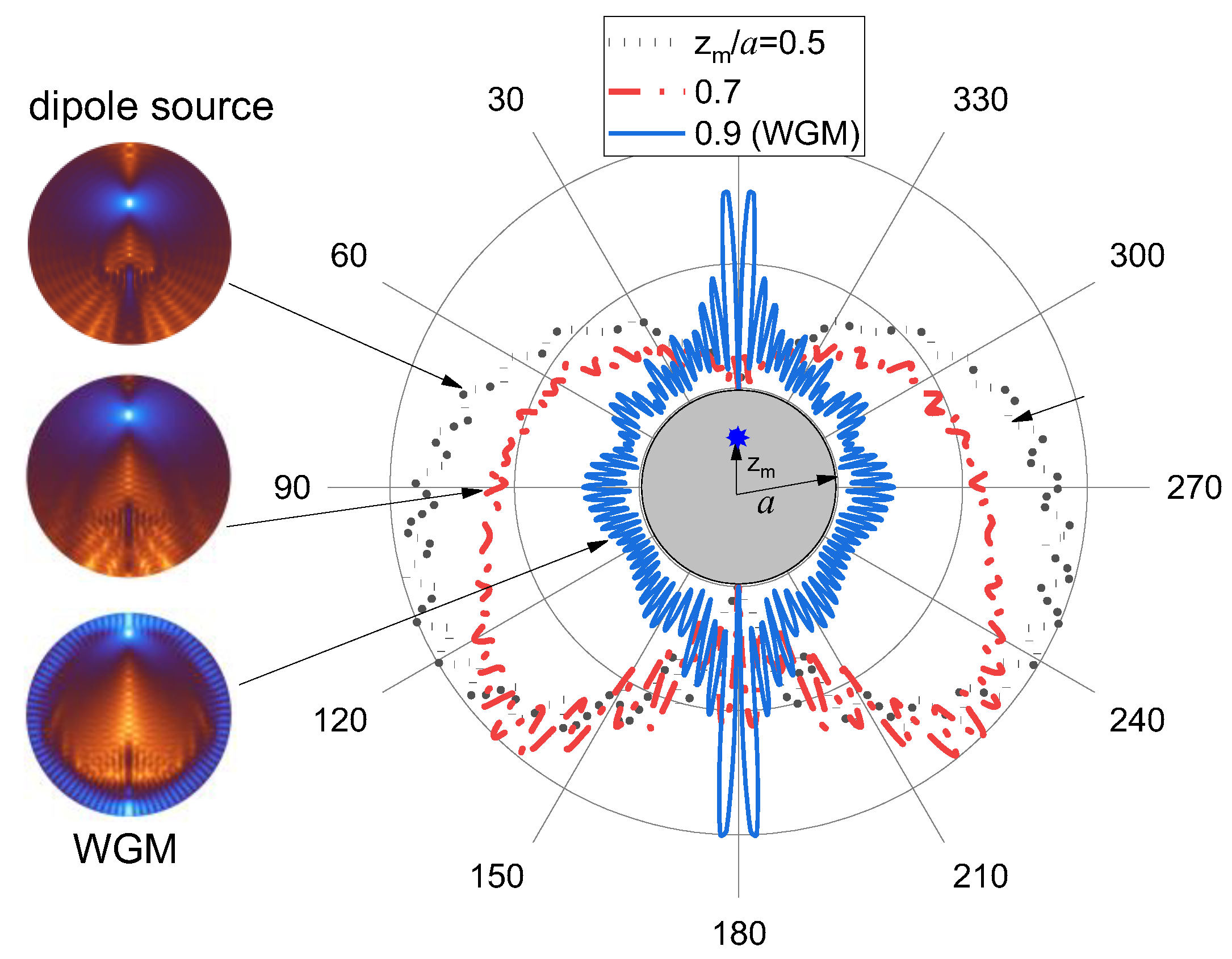

Figure 1.

(a) Schematics of the problem statement on laser-stimulated nonlinear emission from a droplet. (b-e) Relative intensity distribution of (b, c) pumping radiation at λ0 and (d, e) TPA fluorescence at λ1 near water droplets with a = 2 μm (b, d) and 1 μm (c, e).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematics of the problem statement on laser-stimulated nonlinear emission from a droplet. (b-e) Relative intensity distribution of (b, c) pumping radiation at λ0 and (d, e) TPA fluorescence at λ1 near water droplets with a = 2 μm (b, d) and 1 μm (c, e).

Thus, within the framework of the approximations made it

is considered that each molecule of particulate substance located at the point r

inside a particle represents a dipole that first absorbs a certain portion of optical

energy from the incident electromagnetic field E

i (r )

at the wavelength λ

0 and

then spontaneously (stochastically) emits an optical quantum E

1(r )

at a shifted wavelength λ

1.

Without considering the nonradiative relaxation mechanisms, the rate γ

d of spontaneous dipole emission

(probability of dipole transition) is proportional to the scalar product of the

dipole moment p

d of the corresponding energy transition

and local field amplitude

, where m is

the number of simultaneously absorbed photons [22,23].

The governing equation describing the spontaneous

emission from a spherical particle is the following inhomogeneous Helmholtz (wave)

equation which is solved within the stationary problem formulation:

Here, k

0

is the wave number in free space, ε

1

= n

2, and the polarization source P

1 depends

randomly on the radiating dipole spatial position

:

where we use the notation

for the optical intensity, , and denotes a randomly-oriented unit vector of the

dipole (). It follows from Equation (2), that the energy

exchange rate between the optical field and radiating dipole in a unite volume,

, in the case of, e.g., two-photon absorption (m = 2) depends on the squared intensity of the pump field as: .

Worthwhile, when simulating plasma emission from a droplet, the volume density of secondary emission sources in the right-hand side of Equation (1) should be proportional to free electron concentration ρ

e (laser plasma is considered in equilibrium) generated through the photoionization of particle medium induced by the incident (“primary”) radiation. The plasma polarization source reads as:

where the random character of dipole emission is assumed also.

In turn, the density of free electrons in the medium can be determined from the kinetic plasma equation accounting for the field (multiphoton) and impact (avalanche) medium ionization, as well as the decreasing in the concentration of electrons due to the recombination with ions, as follows [

2,

24]:

whereWI is the photoionization rate (probability), ρ

nt is the density of neutrals (molecules, atoms), ν

c – avalanche ionization rate, ν

r is the electron recombination rate. In Equation (4), the diffusion of free electrons from the region occupied by plasma is not accounted during the characteristic time of radiative recombination of femtosecond plasma [

12]. Additionally, further consideration is carried out in approximation of a short optical pulse, when its duration is much less than characteristic decay time of free electron plasma which allows neglecting the term responsible for plasma relaxation in Equation (4).

Then, under the apparent condition, ρ

e << ρ

nt (ρ

nt ≈ 10

22 cm

-3 is the critical density of free electrons when plasma begins resonantly absorbing optical energy), one obtains the following solution to Equation (4) for a rectangular pulse with the duration t

p of stimulating laser radiation [

24]:

Here, , while m-photon water molecule photoionization with a certain rate is assumed: .

By substituting (5) into (3), one obtains an expression for plasma polarization source in a droplet, which is similar to Equation (2). In contrast to TPA fluorescence, the degree of multiphoton ionization of water molecule at wavelength 800 nm is considerably higher and equals to m = 5 because bound electrons in a molecule need to overcome a high energy potential barrier of 6.5 eV to enter the conduction band and become free. In other words, not two but five photons of incident optical radiation are involved in a single excitation event of one plasma electron.

The exponential multiplier in (5) takes into account the “warming up” of free electrons by the optical field in a series of elastic collisions with heavy multicharged particles by the inverse Bremsstrahlung mechanism. This energy excess is used for increasing the kinetic energy of free electron and is converted into electron chaotic drift, which contributes to the development of the electron avalanche. The avalanche rate is proportional to the optical energy density (

Ii⋅tp) at a selected point in the particle. For typical breakdown intensities of a femtosecond pulse,

Ii ~ 5⋅10

13 W/cm

2, with the duration

tp = 100 fs, by accounting the data on ν

c from [

12] one obtains the following estimate for the exponent index: (ν

c⋅

Ii⋅tp) ≈ 10 >> 1. This indicates that in the area of optical breakdown, the dynamics of free electron concentration is not a power dependence, but rather an avalanche-like (exponential) growth with a linear increase in the pulse intensity.

Theoretical simulation of the nonlinear droplet emission is based on the numerical solution of the equation (1) by means of the finite element method implemented in the COMSOL Multiphysics software package. Since the emission of photons by a molecule/ion occurs spontaneously, in the numerical model the emitting dipoles at each point of particle generally are not correlated either in phase or in the direction. Hereafter, in the steady-state approximation we consider only the random direction of the dipole moments by specifying a random polar angle of the dipole

within the range

in the (

r-

z) plane. Then, at each point

r inside the particle the unit dipole moment vector can be represented as a function of a single random parameter:

, where

are unit vectors along the corresponding coordinate axes. In the simulation, the statistics on the droplet emission is gathered by setting different (usually a hundred variants) spatial distributions of dipole moments inside a particle having random dipole moment directions

. For each of these variants the solution of the problem (1)-(5) is carried out separately. All the calculation series are eventually averaged over the spatial coordinates and the resulting angular distribution of the nonlinear droplet emission is obtained in the far-field region (r >>

a) by using Stratton-Chu integrals [

25].

As known, this formalism is based on the assumption that the Green's function for the vector Helmholtz equation (1) in the far-field region is known and the medium in this region is homogeneous. Then, the vectorial electric field of the emission

Efar in the far-field region at any point

r = (

r,θ) located on the surface of certain speculative sphere

S with radius

r and normal

n which encompasses the particle is expressed through the integral of the near-field as follows:

Here, is the medium impedance, and j stays for . Using Equation (6) one can calculate the angular distribution of the emission intensity of a water droplet by calculating the electromagnetic fields E1 and H1 directly near the particle surface.

, where m is

the number of simultaneously absorbed photons [22,23].

, where m is

the number of simultaneously absorbed photons [22,23].