1. Introduction

Treatments for organ failure can present deleterious effects on critically ill patients. Mechanical ventilation or dialysis are essential despite an incorrect prescription on ventilation parameters can produce harmful effects. Barotrauma or dialytrauma has been introduced as syndromic entities, new concepts that has facilitated the general diffusion of these questions, increasing awareness to avoid iatrogenia, and consequently increasing patient’s safety (1,2).

Medical nutritional treatments (MNT) in critically ill patients can be complex, mainly during the first days of illness. The ideal prescription of calories, proteins, fiber or electrolytes is difficult, because is affected by basal patient conditions, impact of acute illness, endogenous production, route for administration… so an special monitoring is suggested (3,4). Over and under prescription of macronutrients is associated to worse prognosis. Moreover, critically ill patients can present comorbid conditions predisposing to refeeding syndrome (5,6).

Recently, Nutritrauma (4) has been described as a structured strategy to increase alert and facilitate the detection of metabolic complications potentially associated to the MNT. The aim of this work was to describe how Nutritrauma strategy implementation in real life help us to detect metabolic complications and inappropriate prescription of MNT in critically ill patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Study Design

A unicenter prospective study was developed in a Medical-Surgical intensive Care Unit with 14 beds of a University Hospital. We included 30 consecutive critically ill patients that received MNT during first trimester of 2020. Patients were monitored from admission to ICU discharge.

Inclusion criteria were: patients admitted to intensive care unit aged 18 years or older with at least 2 organ failures who needs enteral or parenteral nutrition for, at least, 48 hours. Exclusion criteria were patients with a high subjective probability of receive oral nutrition or dead during the first 72h. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Consorci Sanitari del Maresme (Ref. 52/2019).

2.2. The “Nutritrauma strategy” implementation

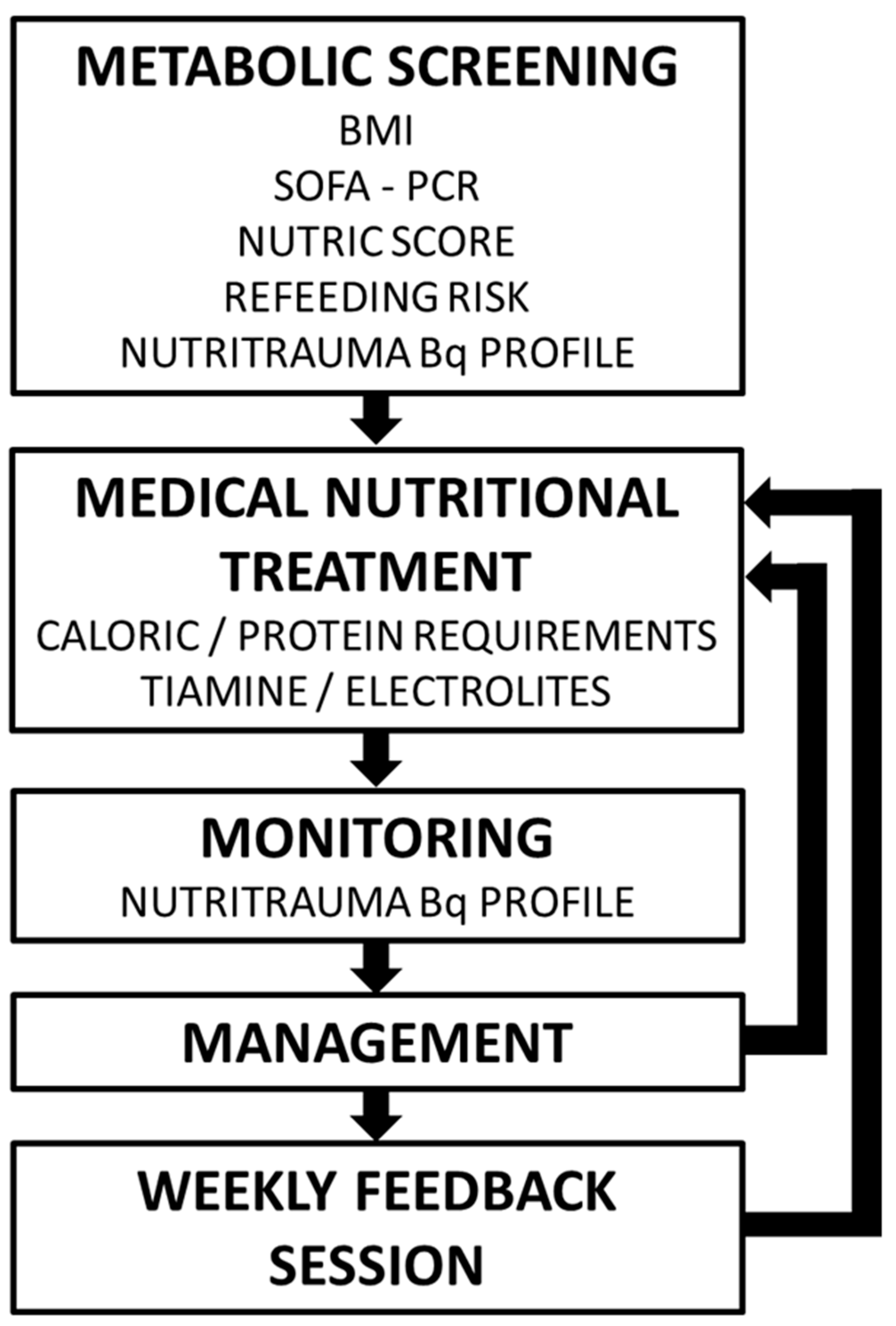

A preliminary multitdisciplinary formative session was conducted. Informative posters were designed and a specific biochemical profile was created in the biochemical laboratory petitionary. The strategy was structured in four M steps: Metabolic screening, MNT Design, Monitoring and Management (

Figure 1).

2.2.1. Metabolic screening

During first 24 hours of admission, severity of illness [Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) (7), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) (8)], evaluation of nutritional risk (modified Nutric Score) (9) and risk of refeeding syndrome (10) were performed.

2.2.2. MNT prescription

Initial nutrition prescription was according institutional protocol. Caloric and protein requirements were estimated separately, using weight-based formulas (using adjusted weight if BMI was >30). The initial caloric prescription was 10-15 Kcal/kg/day if there was a refeeding syndrome risk, and 20 kcal/kg/day if was no risk. Caloric prescription was increased progressively according to the clinical status. Enteral and/or parenteral route was used to achieve caloric objectives. Protein prescription was adjusted to clinical status (from 1,2 to 2 g/kg/day or 2g/Kg/day if BMI was between 30 or 40) (11).

2.2.3. Biochemical monitoring

A specific blood analytic profile was created (named Nutritrauma) that included:

- -

Electrolytes: sodium (Na); potassium (K), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca).

- -

Liver function analysis: Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT), Glutamic Oxaloacetic Transaminase (GOT), Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminase (GPT), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), Total Bilirubin (and indirect and direct bilirubin if it was anormal)

- -

Proteins: total proteins, albumin, prealbumin, transferrin

- -

Lipids: total cholesterol, triglycerides

- -

Inflammation: C Reactive Protein (CRP), lymphocytes.

2.2.4. Nutritional management

Physicians must design their patient’s treatment according to institutional protocol, based on SEMICYUC Guidelines (11). The Nutritrauma blood analysis was performed at the nutrition initiation (day 0), at clinical criteria in presence of abnormal values or nutritional risk, on days 2 and 5, and weekly. Every Wednesday a one-hour multidisciplinary clinical session was performed with presence of the medical ICU staff, a nutritionist, a pharmaceutic, a rehabilitation physician and a physiotherapist.

2.3. Data Collection

The study data included age, sex, weight, and height, Body Mass Index (BMI), APACHE-II and SOFA. Blood levels of total proteins, albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, triglycerides, total cholesterol, CRP, liver function (GGT, GOT, GPT, ALP), and electrolytes (Na, K, Ca, Mg, P] were recorded for each study participant.

During de Wednesday multidisciplinary clinical session nutritional treatment changes were collected as increase of protein and/or caloric dosage, change into an “organ-specific diet” (L-arginina enriched diets, specific diabetic diets and diet for enteral nutrition associated diarrhea) or change to a fiber enriched diet.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were collected in Excel® and exported for analysis to SPSS version 26.0 statistical package (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) to perform descriptive analysis of means or medians based on normality for quantitative variables and of proportions for descriptive variables. Normality was analyzed using Shapiro¬–Wilk tests.

3. Results

3.1. Patients Characteristics

From January to march of 2020, 30 consecutives patients were included. Two of them died before initiation of MNT. Mean age was 69,7 ± 11,3 years, the 50% were female with an admission APACHE II 18,1 ± 8,1, admission SOFA 7,5 ± 3,7, and modified Nutric Score 4,3 ± 2,01. The mean body weigh was 77,4 ± 12,9 kilograms and the mean BMI was 27,2 ± 3,8. Four patients (14,4%) had risk of refeeding syndrome. The most frequent disease on admission was sepsis (46,4%), followed by cardiovascular disease (21,4%) and respiratory failure (17,8%). The main MNT route of administration was enteral nutrition (82,1%). The starting time of the nutritional treatment was appropriate in 92,8% of the patients. The patients remained 20,6 ± 15,1 days in ICU and 39,3% died during the ICU stay. Main characteristics of the 28 patients are described in

Table 1.

3.2. Detection of Metabolic Complications

During follow-up, 54 analytical determinations were made (

Table 2). Hyperglycemia was the most frequent metabolic alteration during evolution (83,3% of patients). Electrolyte disturbances were also frequents: hypocalcemia, adjusted for albumin (50%), hypophosphatemia (29,6%) and hypokalemia (27,8%). After identifying the ion deficit, supplementation was started in 100% of the cases. Regarding liver function, 31,5% of the patients had bilirubin elevation > 2 times its baseline value, not being associated, in this case, with MNT. Similarly, 85,2% of the patients presented cholestasis, none of them being treated with parenteral nutrition. Analyzing the lipid profile, hypocholesterolemia (64,8%) was the most frequent laboratory abnormality followed by hypertriglyceridemia (27,8%), and during serial tests both cholesterol and triglyceride levels normalized without specific treatment. All the protein-related biochemical parameters were low during practically the entire follow-up: hypoproteinemia (90,7%), hypoalbuminemia (88,8%), low transferrin (87%) and low prealbumin (72,2%). Finally, 100% of the patients presented anasarca in the evolution.

3.3. MNT Modifications during multidisciplinary sessions

During the multidisciplinary sessions inappropriate prescription was detected in 53,6% of patients. All of them suffered at least one MNT modification, 3,6% of the patients suffered two modifications and another 3,6% suffered three modifications during their evolution in the ICU. The most frequent modification made was the increase in protein dosage (25%), followed by the increase in caloric dosage (21,4%) and the change to an organ-specific diet (17,8%). The change to a fiber-enriched diet was made in 10,7% of the patients (

Table 3).

Figure 1.

Schema for incorporating the concept of nutritrauma into clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Schema for incorporating the concept of nutritrauma into clinical practice.

4. Discussion

Our work is the first clinical report of the application of nutritrauma concept. In our experience, the grouping of the different complications associated with MNT under the nutritrauma concept facilitated the spread of the concept that inadequate nutritional prescription can be associated with deleterious metabolic effects. The strategy allowed to detect that near 30% of patients presented hypophosphatemia, 50% hypoalbuminemia, and 83% hyperglycemia. Moreover, the combination of the analytical screening with periodical clinical multidisciplinary session facilitated the systematic reevaluation of the MNT, modifying MNT in the 53% of patients.

Glucose blood levels alteration is quite common in critically ill patients. Its prevalence is difficult to know, it depends on the cut-off point we consider hyperglycemia. In our sample, 83,3% of patients presented glucose levels above 150 mg/dL, this data is consistent with that literature describe. Hyperglycemia may be related to overfeeding, insulin resistance in the acute phase of metabolic response, or even insufficient insulin treatment (12). It is described that hyperglycemia is associated with poor clinical outcomes, increase mobidity and mortality (13),alters the immune response, causing increased risk of infection, reduces vascular reactivity and nitric oxide, compromising blood flow and increases proteolysis, being associated with a greater risk of cardiac and renal complications (14). Although treatment of hyperglycemia is associated with better results, strict control is not recommended, which is associated with higher mortality. That is why most scientific societies recommend glucose levels between 140 – 180 mg/dL (15). Avoiding hyperglycemia is not enough, it is increasingly important to control glycemic variability, which is also associated to mortality (14,15).

Electrolyte disorders, as hypocalcemia (50%) and hypophosphatemia (29,6%) were very frequent. Calcium is the most plentiful mineral in the body. It has skeletal functions, such as bone tissue building and non-skeletal ones. The latter are divided in structural, like organelles or cell membranes formation and regulatory, such as enzymatic reactions to modify cell functions (16). Hypocalcemia may have severe consequences, such as seizures, laryngospasm, prolonged QT or cardiac dysfunction (17). In critically ill patients, abnormal calcium values can be a marker of severity, and it is often corrected spontaneously when the primary disease is solved. There is not enough evidence on the hypocalcemia management, although generalized administration is discouraged to normalize its values and it is concluded that treatment should be guided by basic decision-making principles (18).

Phosphate has several functions in the body (19), as energy function (it is part of adenosine triphosphate, ATP), structural function (it is a component of the phospholipids of cell membranes and nucleic acids), activation of proteins through their phosphorylation, intracellular buffering effect and mineralization of the bone matrix. Hypophosphatemia produces a wide spectrum of symptoms when there is a depletion of intracellular phosphate. Its deficit produces an increase in the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen, reducing its delivery at the tissues and, the ATP deficit produces alterations in the cellular functions affecting neurological, cardiopulmonary, muscular and hematological systems. In critically ill patients, hypophosphatemia, in addition to the described symptoms, is a risk marker for refeeding syndrome, a syndrome associated with high morbidity and mortality (10). As reflected in the latest ASPEN consensus recommendations on refeeding syndrome (20), the identification of hypophosphatemia can help to identify patients at risk of presenting refeeding syndrome.

During the Nutritrauma strategy the MNT prescription was optimized in 53,6% of patients. In our experience, one of the most frequent difficulty of MNT for not expert physicians, is to adapt de prescription of MNT to the metabolic situation (21) and syndromic characteristics (22–24). Many studies show that the amount of calories and proteins that critical ill patients receives is lower than calculated requirements (25,26). This is associated with worse evolution (27). The evaluation of daily nutritional requirements could minimize this concern. Despite our patients were in a not blinded observational study, underfeeding remained the most frequent complication related with doses. Consequently, the increase of protein (25%) and caloric dosage (20%) were the most frequently modifications.

The qualitative characteristics of the diets can also affect the patient evolution. We introduced changes in the prescription of organ-specific diet in a 17,8% of patients (22). The SEMICYUC recommendations for specialized nutritional – metabolic management of the critical patient includes soluble and insoluble fiber diets to prevent complications such as diarrheal, constipation and tolerance to enteral nutrition (28). We detected a significant percentage of patients that were not receiving fiber-enriched diet, so the prescription of fiber-enriched diet was very common (10,7%).

Finally, the positive effects of multidisciplinary meetings is difficult to measure. To share weekly doubts and interpretations of nutritional practice with experts allows, not only identify wrong dosages and metabolic disorders, but also the increasing of MNT knowledge.

Our work has some limitations. This is a not blinded observational study designed to evaluate applicability of the nutritrauma strategy. In our opinion, the main limitation is that it has been developed in a single center with a low number of patients. However, this is the first clinical application reported of the nutritrauma concept, and the benefits observed encourage us to presents our protocol and results.

5. Conclusions

The concept nutritrauma has been useful to spread the concept that MNT must be carefully designed and monitored to avoid harmful effects. The application of Nutritrauma strategy facilitate the detection of metabolic complications and the evaluation of the appropriate prescription of the MNT. The weekly multidisciplinary session results in a powerful assistential and educational strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization JCY, IMdL, JP, LC. Methodology all authors. Investigation, IMdL, JP. Formal analysis JCY, IMdL, JP. Review and editing, All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital de Mataró (protocol code 52/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the observational nature of the project.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in this work is available contacting with the Unitat de Recerca de l’Hospital de Mataró (recerca@csdm.cat).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar, A.; Pontoppidan, H.; Falke, K.J.; Wilson, R.S.; Laver, M.B. Pulmonary barotrauma during mechanical ventilation. Crit. Care Med. 1973, 1, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynar Moliner J, Honore PM, Sánchez-Izquierdo Riera JA, Herrera Gutiérrez M SH. Handling continuous renal replacement therapy-related adverse effects in intensive care unit patients: the dialytrauma concept. Blood Purif. 2012;34(2):177-85. [CrossRef]

- Berger MM, Reintam-Blaser A, Calder PC, Casaer M, Hiesmayr MJ, Mayer K, Montejo JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, van Zanten ARH, Bischoff SC, Singer P.Berger MM, Reintam-Blaser A, Calder PC, Casaer M, Hiesmayr MJ, Mayer K, Montejo JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, van SP. Monitoring nutrition in the ICU. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(2):584-593. [CrossRef]

- Yébenes, J.C.; Campins, L.; de Lagran, I.M.; Bordeje, L.; Lorencio, C.; Grau, T.; Montejo, J.C.; Bodí, M.; Serra-Prat, M. ; Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism of the Spanish Society of Critical Care Nutritrauma: A Key Concept for Minimising the Harmful Effects of the Administration of Medical Nutrition Therapy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Elson, M.; Martínez-Carmona, J.; Ruiz-Santana, S. Recommendations for specialized nutritional-metabolic management of the critical patient: Consequences of malnutrition in the critically ill and assessment of nutritional status. Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC). Med. Intensiv. 2020, 44, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, O.; Theilla, M.; Cohen, J.; Kagan, I.; Bendavid, I.; Singer, P. Resting energy expenditure, calorie and protein consumption in critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, Sprung CL, Colardyn F BS. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;Nov;26(11):1793–800.

- Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP ZJ. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;Oct;13(10):818–29. [PubMed]

- eyland, D.K.; Dhaliwal, R.; Jiang, X.; Day, A.G. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R268–R268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot R, Koekkoek KWAC van ZA. Refeeding syndrome: relevance for the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24(4):235-240. [CrossRef]

- Serón Arbeloa C, Martínez de la Gándara A, León Cinto C, Flordelís Lasierra JL MVJ. Recommendations for specialized nutritional-metabolic management of the critical patient: Macronutrient and micronutrient requirements. Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Unit. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2020;44(suppl 1):24-32. [CrossRef]

- Preiser, J.-C.; Ichai, C.; Orban, J.-C.; Groeneveld, A.B.J. Metabolic response to the stress of critical illness. Br. J. Anaesth. 2014, 113, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalfon, P.; On behalf of the CGAO–REA Study Group; Giraudeau, B. ; Ichai, C.; Guerrini, A.; Brechot, N.; Cinotti, R.; Dequin, P.-F.; Riu-Poulenc, B.; Montravers, P.; et al. Tight computerized versus conventional glucose control in the ICU: a randomized controlled trial. Intensiv. Care Med. 2014, 40, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, CW. Glycemic control in critically ill patients. World J Crit Care Med. 2012;1(1):31–9. [CrossRef]

- Alhatemi G, Aldiwani H, Alhatemi R, Hussein M, Mahdai S SB. Glycemic control in the critically ill: Less is more. Cleve Clin J Med. 2022;89(4):191–9. [CrossRef]

- Martínez de Victoria, E. El calcio, esencial para la salud [Calcium, essential for health]. Nutr Hosp. 2016;33(Suppl 4):341. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Levine, M. A. Hypocalcemia in the critically ill patient. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28(3):166–77. [CrossRef]

- Aberegg S K. Ionized Calcium in the ICU: Should It Be Measured and Corrected? Chest. 2016;149(3):846-55. [CrossRef]

- García Martín A, Varsavsky M, Cortés Berdonces M, Ávila Rubio V, Alhambra Expósito MR, Novo Rodríguez C, Rozas Moreno P, Romero Muñoz M, Jódar Gimeno E, Rodríguez Ortega P MTM. Phosphate disorders and clinical management of hypophosphatemia and hyperphosphatemia. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2020;67(3):205-215. [CrossRef]

- da Silva JSV, Seres DS, Sabino K, Adams SC, Berdahl GJ, Citty SW, Cober MP, Evans DC, Greaves JR, Gura KM, et al. ASPEN Consensus Recommendations for Refeeding Syndrome. Nutr Clin Pr. 2020;35(2):178-195. [CrossRef]

- van Zanten ARH, De Waele E WP. Nutrition therapy and critical illness: practical guidance for the ICU, post-ICU, and long-term convalescence phases. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):368. [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.P.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo, J.C.; Pichard, C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Leyba C, Valenzuela Sánchez F YRJ. Recommendations for specialized nutritional-metabolic treatment of the critical patient: Sepsis and septic shock. Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC). Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2020;44(Suppl 1):55-59. [CrossRef]

- Blesa-Malpica A, Martín-Luengo A R-GA. Recommendations for specialized nutritional-metabolic management of the critical patient: Special situations, polytraumatisms and critical burn patients. Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2020;44(Suppl 1):73-76. [CrossRef]

- Servia-Goixart L, Lopez-Delgado JC, Grau-Carmona T, Trujillano-Cabello J, Bordeje-Laguna ML, Mor-Marco E, Portugal-Rodriguez E, Lorencio-Cardenas C, Montejo-Gonzalez JC, Vera-Artazcoz P, Macaya-Redin L, Martinez-Carmona JF, Iglesias-Rodriguez R, Monge-Don Y-RJESI. Evaluation of Nutritional Practices in the Critical Care patient (The ENPIC study): Does nutrition really affect ICU mortality? Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022;47:325-332. [CrossRef]

- Flordelís Lasierra JL, Montejo González JC, López Delgado JC, Zárate Chug P, Martínez Lozano-Aranaga F, Lorencio Cárdenas C, Bordejé Laguna ML, Maichle S, Terceros Almanza LJ, Trasmonte Martínez MV, Mateu Campos L, Servià Goixart L, Vaquerizo Alonso C VGB the NSG. Enteral nutrition in critically ill patients under vasoactive drug therapy: The NUTRIVAD study. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 46(6):1420-1430. [CrossRef]

- Bordejé Laguna ML, Martínez de Lagrán Zurbano I LDJ. Hiponutrición vs Nutrición artificial Precoz. Nutr Clin Med. 2016;X(2):79–94.

- Montejo González JC, de la Fuente O’Connor E, Martínez-Lozano Aranaga F SGL. Recommendations for specialized nutritional-metabolic treatment of the critical patient: Pharmaconutrients, specific nutrients, fiber, synbiotics. Metabolism and Nutrition Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Co. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2020;44(Suppl 1):39-43. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).