Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

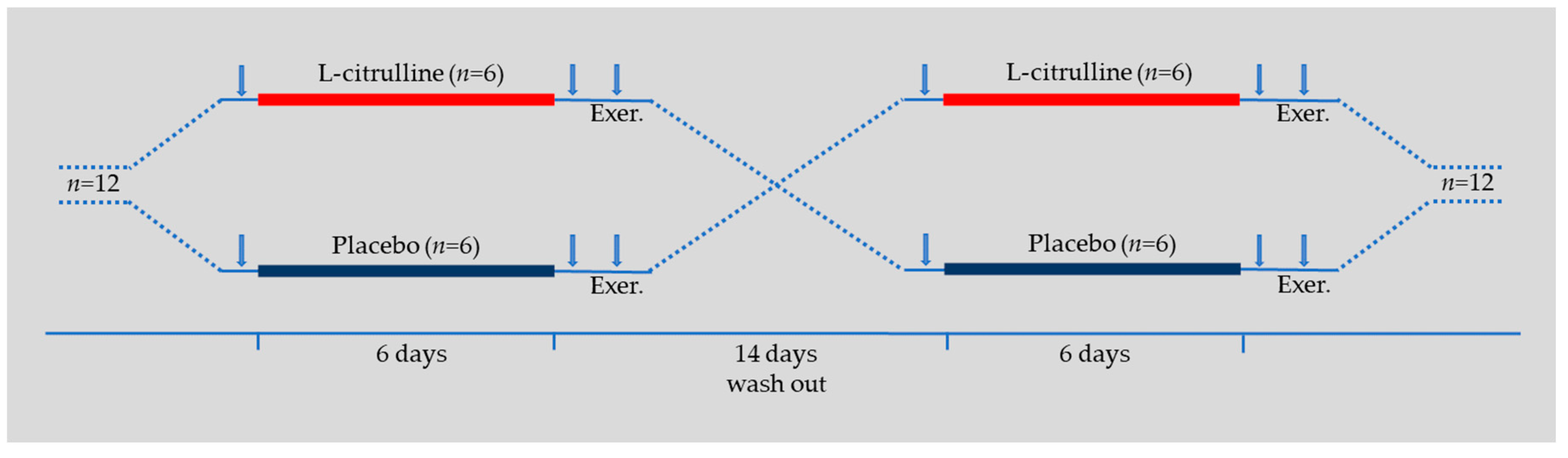

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Anthropometry

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Blood Hemodynamics

2.5. Arterial Pressure Waveform Analysis and Pulse Wave Velocity

2.6. Muscle Oxygenation and Blood Flow

2.7. Isometric Knee Extensors Exercise

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

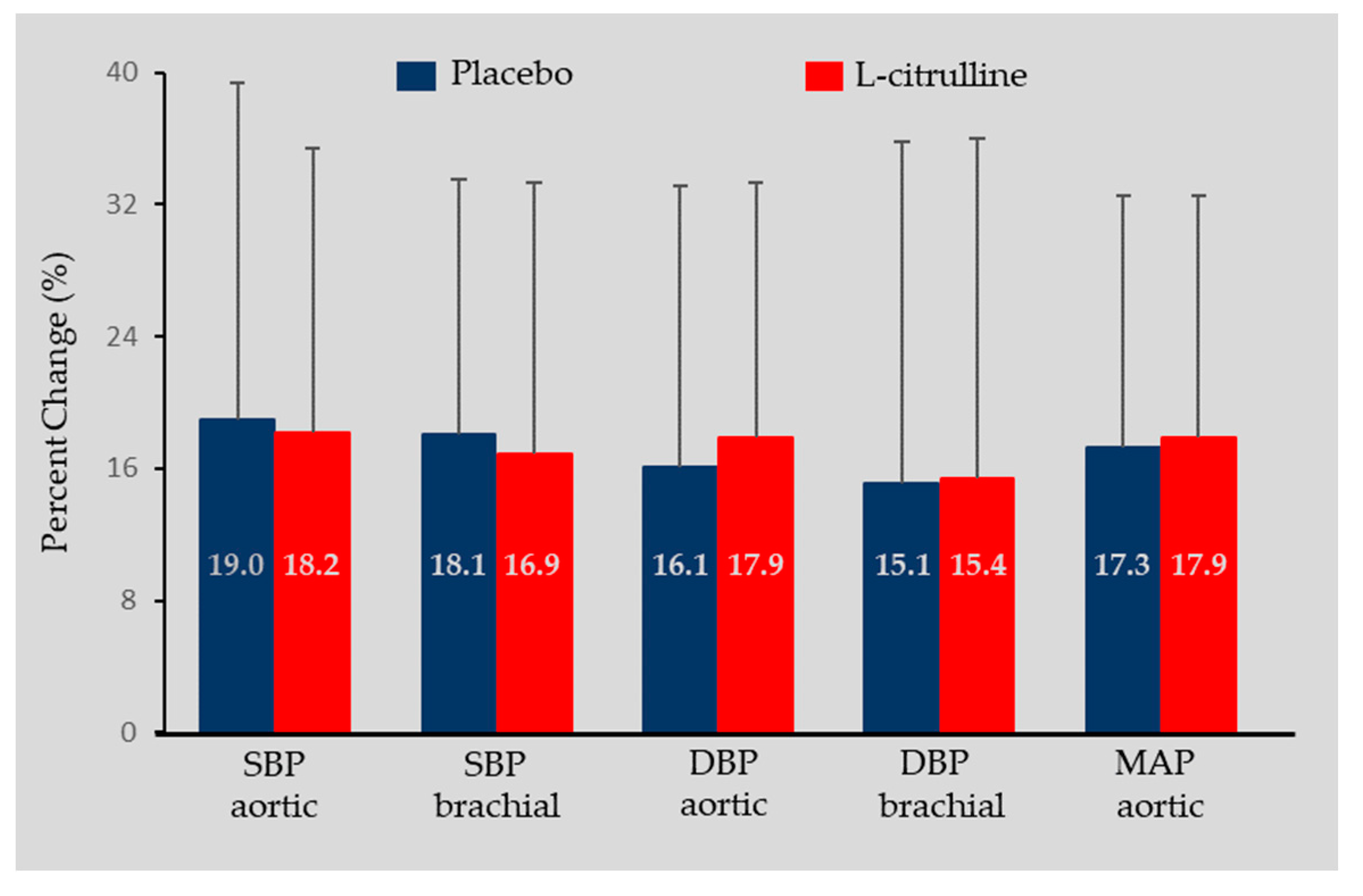

3.1. Blood Hemodynamics

3.2. Arterial Pressure Waveform Analysis and Pulse Wave Velocity

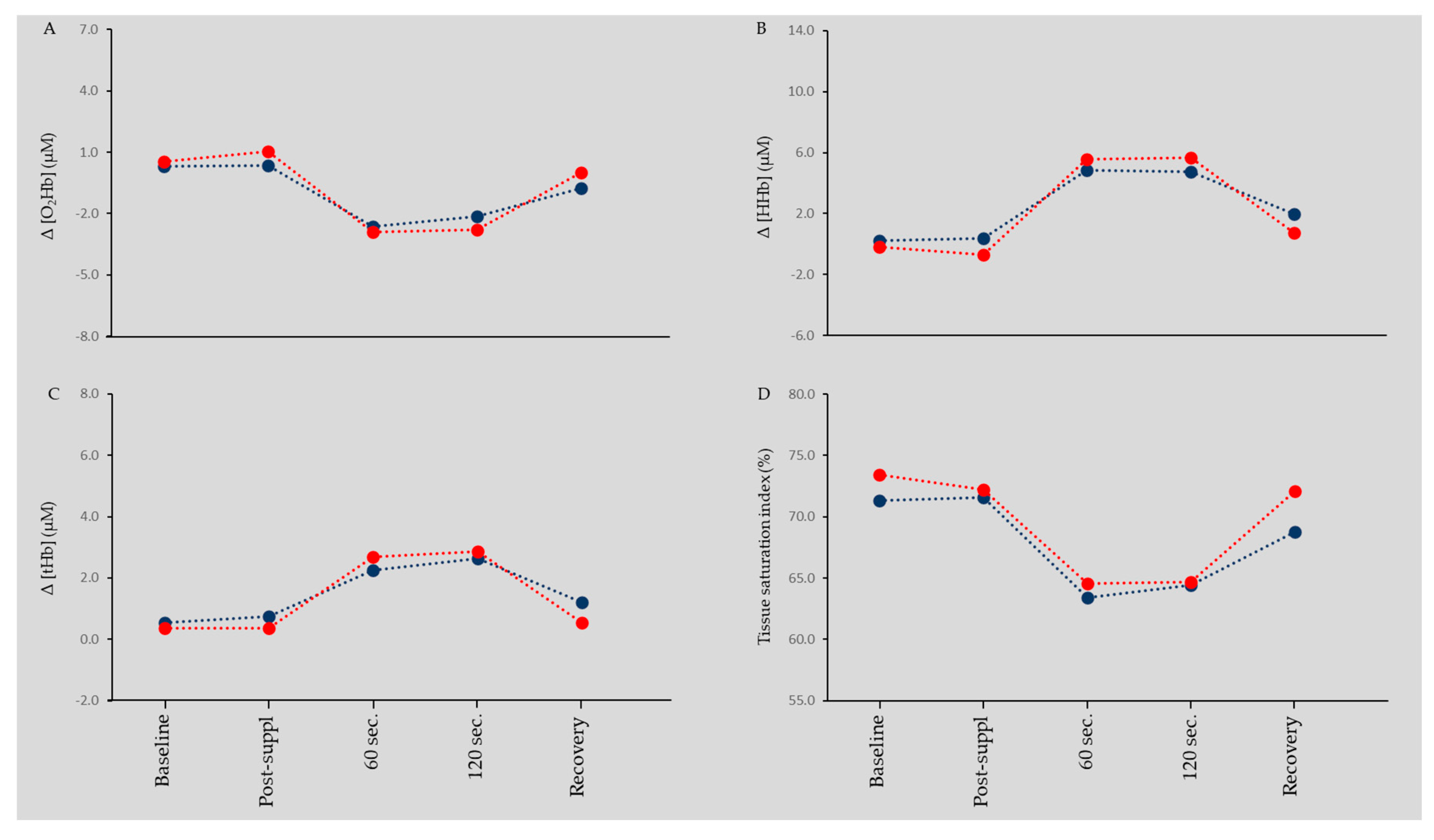

3.3. Muscle Oxygenation and Blood Flow

4. Discussion

4.1. L-Citrulline and Blood Pressure

4.2. L-Citrulline and Arterial Stiffness

4.3. L-Citrulline, Muscle Oxygenation, and Blood Flow

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, B.M.; Rong, J.; Larson, M.G.; Hamburg, N.M.; Vita, J.A.; Levy, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Vasan, R.S.; Mitchell, G.F. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA 2012, 308, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness and hypertension: chicken or egg? Hypertension 2014, 64, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safar, M.E.; Asmar, R.; Benetos, A.; Blacher, J.; Boutouyrie, P.; Lacolley, P.; Laurent, S.; London, G.; Pannier, B.; Protogerou, A.; et al. Interaction Between Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension 2018, 72, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Bombelli, M.; Facchetti, R.; Madotto, F.; Corrao, G.; Trevano, F.Q.; Grassi, G.; Sega, R. Long-term prognostic value of blood pressure variability in the general population: results of the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni Study. Hypertension 2007, 49, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willum-Hansen, T.; Staessen, J.A.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Rasmussen, S.; Thijs, L.; Ibsen, H.; Jeppesen, J. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation 2006, 113, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Nitric oxide signaling in health and disease. Cell 2022, 185, 2853–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousoulis, D.; Kampoli, A.M.; Tentolouris, C.; Papageorgiou, N.; Stefanadis, C. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2012, 10, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamler, J.S.; Meissner, G. Physiology of nitric oxide in skeletal muscle. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Chatzinikolaou, A.N.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Vrabas, I.S.; Kyparos, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Oxygen Transport. A Redox O2dyssey. In Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology, Cobley, J.N., Davison, G.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Kyparos, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Antioxidants in Personalized Nutrition and Exercise. Adv Nutr 2018, 9, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J.; Shiva, S.; Gladwin, M.T. Sources of Vascular Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Regulation. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 311–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bescos, R.; Sureda, A.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. The effect of nitric-oxide-related supplements on human performance. Sports Med 2012, 42, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerksick, C.M.; Wilborn, C.D.; Roberts, M.D.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Kleiner, S.M.; Jager, R.; Collins, R.; Cooke, M.; Davis, J.N.; Galvan, E.; et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2018, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Poll, M.C.; Siroen, M.P.; van Leeuwen, P.A.; Soeters, P.B.; Melis, G.C.; Boelens, P.G.; Deutz, N.E.; Dejong, C.H. Interorgan amino acid exchange in humans: consequences for arginine and citrulline metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 85, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwedhelm, E.; Maas, R.; Freese, R.; Jung, D.; Lukacs, Z.; Jambrecina, A.; Spickler, W.; Schulze, F.; Boger, R.H. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of oral L-citrulline and L-arginine: impact on nitric oxide metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008, 65, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.M., Jr. Enzymes of arginine metabolism. J Nutr 2004, 134, 2743S–2747S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curis, E.; Nicolis, I.; Moinard, C.; Osowska, S.; Zerrouk, N.; Benazeth, S.; Cynober, L. Almost all about citrulline in mammals. Amino Acids 2005, 29, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windmueller, H.G.; Spaeth, A.E. Source and fate of circulating citrulline. Am J Physiol 1981, 241, E473–E480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinard, C.; Maccario, J.; Walrand, S.; Lasserre, V.; Marc, J.; Boirie, Y.; Cynober, L. Arginine behaviour after arginine or citrulline administration in older subjects. Br J Nutr 2016, 115, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, E.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Lobato, B.; Alacid, F. L-Citrulline: A Non-Essential Amino Acid with Important Roles in Human Health. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, T.D.; Proctor, D.N.; Stephens, J.M.; Dugas, T.R.; Spielmann, G.; Irving, B.A. l-Citrulline Supplementation: Impact on Cardiometabolic Health. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, A.; Fischer, S.M.; Dillon, K.N.; Kang, Y.; Martinez, M.A.; Figueroa, A. Effects of L-Citrulline Supplementation on Endothelial Function and Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Koutnik, A.P.; Ramirez, K.; Wong, A.; Figueroa, A. The effects of short term L-citrulline supplementation on wave reflection responses to cold exposure with concurrent isometric exercise. Am J Hypertens 2013, 26, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Jaime, S.J.; Kinsey, A.W.; Spicer, M.T.; Madzima, T.A.; Figueroa, A. Combined whole-body vibration training and l-citrulline supplementation improves pressure wave reflection in obese postmenopausal women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016, 41, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Chernykh, O.; Figueroa, A. Chronic l-citrulline supplementation improves cardiac sympathovagal balance in obese postmenopausal women: A preliminary report. Auton Neurosci 2016, 198, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.H.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, W.G.; Figueroa, A.; Chen, L.H.; Qin, L.Q. Effect of oral L-citrulline on brachial and aortic blood pressure defined by resting status: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2019, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chant, B.; Bakali, M.; Hinton, T.; Burchell, A.E.; Nightingale, A.K.; Paton, J.F.R.; Hart, E.C. Antihypertensive Treatment Fails to Control Blood Pressure During Exercise. Hypertension 2018, 72, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.P.; Young, C.N.; Fadel, P.J. Autonomic adjustments to exercise in humans. Compr Physiol 2015, 5, 475–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butlin, M.; Qasem, A. Large Artery Stiffness Assessment Using SphygmoCor Technology. Pulse (Basel) 2017, 4, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorou, A.A.; Zinelis, P.T.; Malliou, V.J.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Mandalidis, D.; Geladas, N.D.; Paschalis, V. Acute L-Citrulline Supplementation Increases Nitric Oxide Bioavailability but Not Inspiratory Muscle Oxygenation and Respiratory Performance. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, A.W.; Thomas, M.W.; Bohannon, R.W. Normative values for isometric muscle force measurements obtained with hand-held dynamometers. Phys Ther 1996, 76, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. The age-related hemodynamic changes of blood pressure and their impact on the incidence of cardiovascular disease and stroke: new evidence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014, 16, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E. Blood pressure and ageing. Postgrad Med J 2007, 83, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungvari, Z.; Tarantini, S.; Kiss, T.; Wren, J.D.; Giles, C.B.; Griffin, C.T.; Murfee, W.L.; Pacher, P.; Csiszar, A. Endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis impairment in the ageing vasculature. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrenson, L.; Poole, J.G.; Kim, J.; Brown, C.; Patel, P.; Richardson, R.S. Vascular and metabolic response to isolated small muscle mass exercise: effect of age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003, 285, H1023–H1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, A.C.; Aranke, M.; Bryan, N.S. Nitric oxide and geriatrics: Implications in diagnostics and treatment of the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol 2011, 8, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, J.U.; Raymond, A.; Ashley, J.; Kim, Y. Does l-citrulline supplementation improve exercise blood flow in older adults? Exp Physiol 2017, 102, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, M.; Hayashi, T.; Morita, M.; Ina, K.; Maeda, M.; Watanabe, F.; Morishita, K. Short-term effects of L-citrulline supplementation on arterial stiffness in middle-aged men. Int J Cardiol 2012, 155, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.A.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Christodoulou, F.; Tsatalas, T.; Paschalis, V. Short-Term L-Citrulline Supplementation Does Not Affect Inspiratory Muscle Oxygenation and Respiratory Performance in Older Adults. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalaf, D.; Kruger, M.; Wehland, M.; Infanger, M.; Grimm, D. The Effects of Oral l-Arginine and l-Citrulline Supplementation on Blood Pressure. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Jaime, S.J.; Kalfon, R. l-Citrulline supplementation attenuates blood pressure, wave reflection and arterial stiffness responses to metaboreflex and cold stress in overweight men. Br J Nutr 2016, 116, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Trivino, J.A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Vicil, F. Oral L-citrulline supplementation attenuates blood pressure response to cold pressor test in young men. Am J Hypertens 2010, 23, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime, S.J.; Nagel, J.; Maharaj, A.; Fischer, S.M.; Schwab, E.; Martinson, C.; Radtke, K.; Mikat, R.P.; Figueroa, A. L-Citrulline supplementation attenuates aortic pulse pressure and wave reflection responses to cold stress in older adults. Exp Gerontol 2022, 159, 111685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, S.; Ichihara, A. Late age at menopause positively associated with obesity-mediated hypertension. Hypertens Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, E.; Mensink, R.P.; Joris, P.J. Effects of L-citrulline supplementation and watermelon consumption on longer-term and postprandial vascular function and cardiometabolic risk markers: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults. Br J Nutr 2021, 128, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, E.J. The Influence of Obesity and Metabolic Health on Vascular Health. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2022, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.D.; Gona, P.; Larson, M.G.; Plehn, J.F.; Benjamin, E.J.; O'Donnell, C.J.; Levy, D.; Vasan, R.S.; Wang, T.J. Exercise blood pressure and the risk of incident cardiovascular disease (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2008, 101, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashina, A.; Tomiyama, H.; Arai, T.; Hirose, K.; Koji, Y.; Hirayama, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hori, S. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as a marker of atherosclerotic vascular damage and cardiovascular risk. Hypertens Res 2003, 26, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, A.; Wong, A.; Jaime, S.J.; Gonzales, J.U. Influence of L-citrulline and watermelon supplementation on vascular function and exercise performance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2017, 20, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Chiesa, S.T.; Chaturvedi, N.; Hughes, A.D. Recent developments in near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for the assessment of local skeletal muscle microvascular function and capacity to utilise oxygen. Artery Res 2016, 16, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincivero, D.M.; Gandhi, V.; Timmons, M.K.; Coelho, A.J. Quadriceps femoris electromyogram during concentric, isometric and eccentric phases of fatiguing dynamic knee extensions. J Biomech 2006, 39, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.Y.; Schutzler, S.E.; Schrader, A.; Spencer, H.J.; Azhar, G.; Deutz, N.E.; Wolfe, R.R. Acute ingestion of citrulline stimulates nitric oxide synthesis but does not increase blood flow in healthy young and older adults with heart failure. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015, 309, E915–E924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.J.; Blackwell, J.R.; Lord, T.; Vanhatalo, A.; Winyard, P.G.; Jones, A.M. l-Citrulline supplementation improves O2 uptake kinetics and high-intensity exercise performance in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015, 119, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, P.J.; Currie, G.; Delles, C. Sex Differences in the Prevalence, Outcomes and Management of Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2022, 24, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Mechanisms of sex and gender differences in hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhewicz, A.E.; Wenner, M.M.; Stachenfeld, N.S. Sex differences in endothelial function important to vascular health and overall cardiovascular disease risk across the lifespan. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018, 315, H1569–H1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n = 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 64.3 | ± | 5.1 |

| Height (cm) | 173.9 | ± | 4.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.4 | ± | 6.9 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.0 | ± | 2.7 |

| Body fat (%) | 26.8 | ± | 2.6 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100 | ± | 5.6 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 105.8 | ± | 6.8 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.95 | ± | 0.02 |

| Interactions and Main Effects | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post Suppl. | Dur. Exercise | C×T | C | T | |||||||

| Heart Rate (bpm) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 64.1 | ± | 6.3 | 64.0 | ± | 7.9 | 76.8 | ± | 11.5 | p=0.631 | p=0.963 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 63.5 | ± | 5.9 | 63.7 | ± | 6.1 | 78.1 | ± | 9.0 | |||

| Aortic SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 121.9 | ± | 13.3 | 121.2 | ± | 12.7 | 142.5 | ± | 17.4 | p=0.899 | p=0.822 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 120.0 | ± | 11.5 | 121.1 | ± | 11.3 | 141.8 | ± | 14.4 | |||

| Brachial SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 130.8 | ± | 13.2 | 129.4 | ± | 12.6 | 152.5 | ± | 21.6 | p=0.553 | p=0.788 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 131.5 | ± | 12.6 | 130.1 | ± | 14.5 | 151.8 | ± | 23.8 | |||

| Aortic DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 83.3 | ± | 6.1 | 84.1 | ± | 6.5 | 97.5 | ± | 14.8 | p=0.919 | p=0.608 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 82.1 | ± | 5.9 | 81.9 | ± | 7.2 | 96.3 | ± | 9.0 | |||

| Brachial DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 83.4 | ± | 6.0 | 84.2 | ± | 7.9 | 97.3 | ± | 21.5 | p=0.808 | p=0.652 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 82.8 | ± | 7.6 | 82.1 | ± | 6.5 | 94.6 | ± | 17.1 | |||

| Aortic MAP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 99.2 | ± | 8.0 | 99.4 | ± | 8.2 | 116.0 | ± | 13.0 | p=0.962 | p=0.660 | p<0.001 |

| L-Citrulline | 97.7 | ± | 6.6 | 98.1 | ± | 7.2 | 115.1 | ± | 12.6 | |||

| Aortic PP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 38.6 | ± | 11.4 | 37.1 | ± | 10.7 | 45.01 | ± | 18.7 | p=0.856 | p=0.876 | p=0.071 |

| L-Citrulline | 37.9 | ± | 11.5 | 39.2 | ± | 11.4 | 45.5 | ± | 12.0 | |||

| Interactions and Main Effects | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post Suppl. | Dur. Exercise | C×T | C | T | |||||||

| Augmented pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 10.8 | ± | 4.4 | 11.0 | ± | 4.4 | 11.3 | ± | 5.7 | p=0.537 | p=0.730 | p=0.286 |

| L-Citrulline | 11.1 | ± | 4.4 | 11.2 | ± | 4.0 | 12.8. | ± | 6.8 | |||

| Augmentation Index (%) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 31.9 | ± | 20.3 | 32.9 | ± | 19.4 | 37.2 | ± | 16.2 | p=0.729 | p=0.965 | p=0.796 |

| L-Citrulline | 35.7 | ± | 17.5 | 31.6 | ± | 14.6 | 33.5 | ± | 17.6 | |||

| Forward Wave Pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 43.3 | ± | 5.6 | 31.9 | ± | 5.1 | 32.7 | ± | 4.8 | p=0.896 | p=0.816 | p=0.503 |

| L-Citrulline | 31.5 | ± | 4.5 | 31.6 | ± | 5.6 | 32.4 | ± | 6.1 | |||

| Backward Wave Pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 17.2 | ± | 4.0 | 17.5 | ± | 4.2 | 17.8 | ± | 4.4 | p=0.769 | p=0.659 | p=0.631 |

| L-Citrulline | 16.8 | ± | 5.3 | 16.5 | ± | 3.2 | 17.0 | ± | 4.2 | |||

| c-f Pulse Wave Velocity (m/s) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 7.3 | ± | 1.7 | 7.1 | ± | 1.4 | p=0.251 | p=0.251 | p=0.666 | |||

| L-Citrulline | 7.7 | ± | 1.8 | 7.7 | ± | 1.8 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).