Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Core tip

2. Introduction

3. People with inflammatory bowel disease are at escalated probability for risk for colitis-associated colorectal cancer with a subsequent poor prognosis

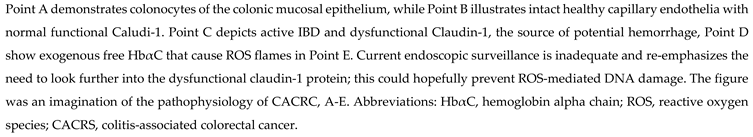

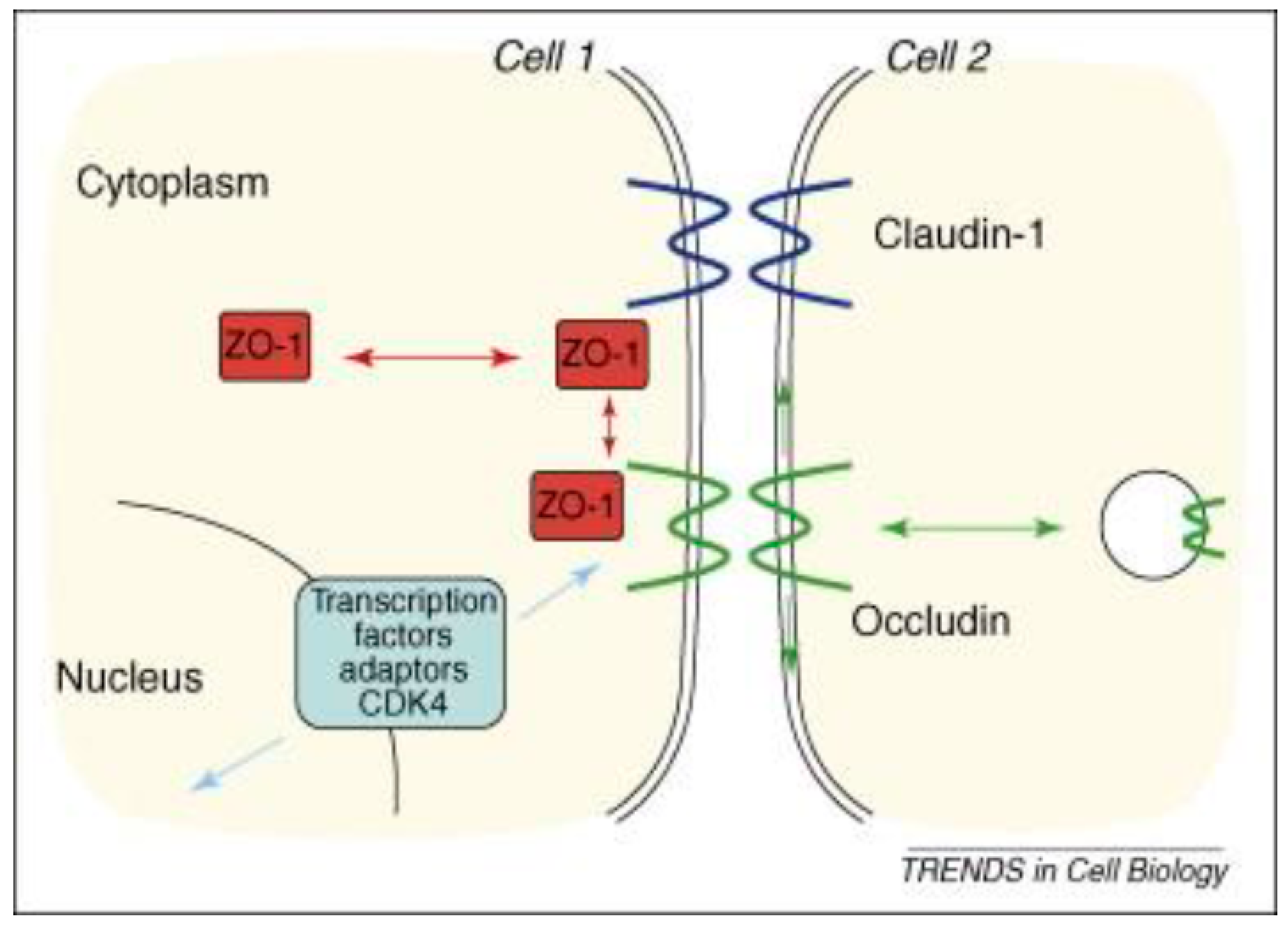

4. Malfunction tight junction protein Caludin-1 is source point of colitis-associated colorectal cancer carcinogenesis

5. Pharmacological mitigation

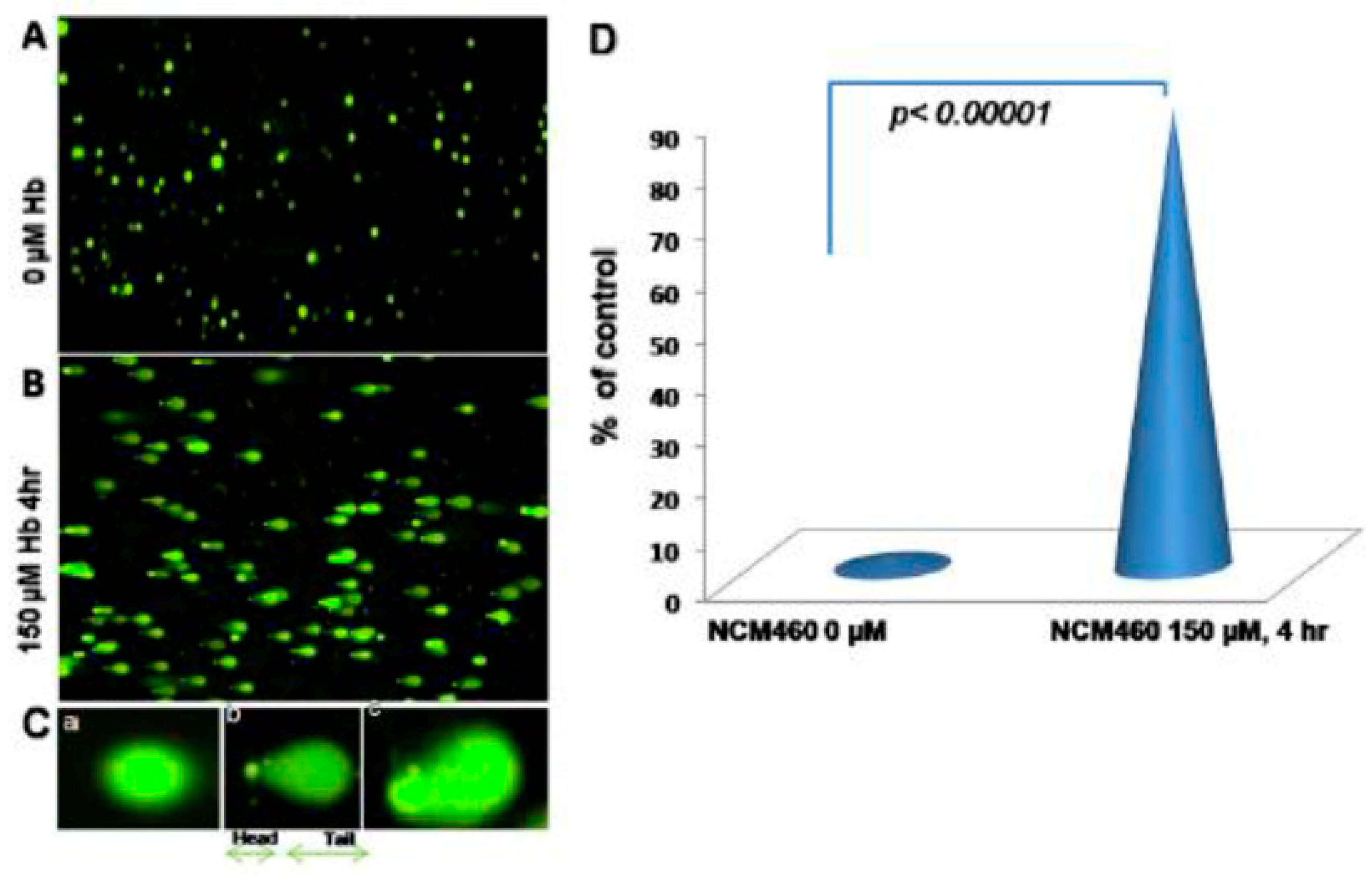

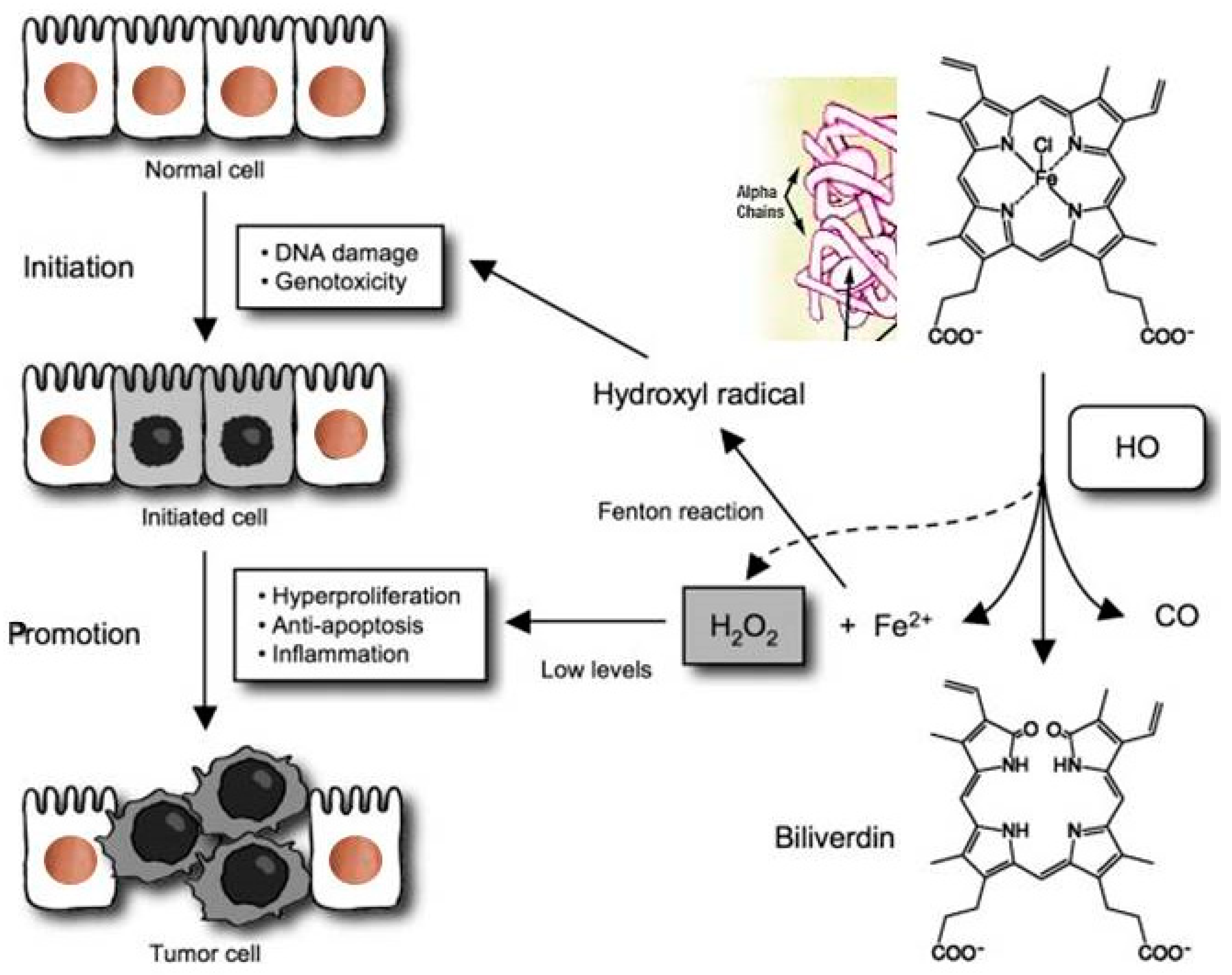

5. Pharmacological mitigation of Fenton Reaction to prevent colitis-associated colorectal cancer oncogenes

6. Pharmaceutical approach to prevent colitis-associated colorectal cancer

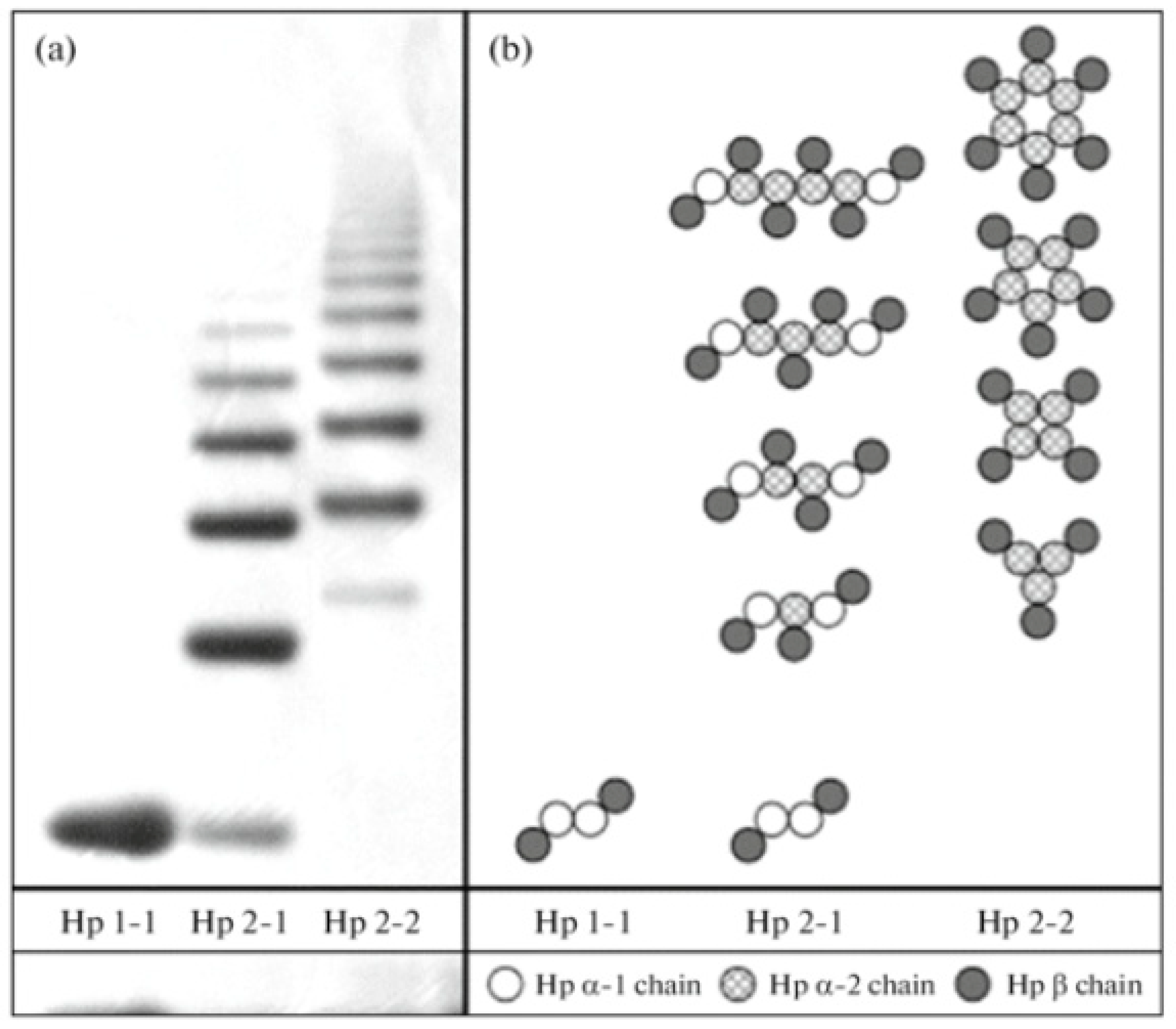

6.1. Haptoglobin (Hp)

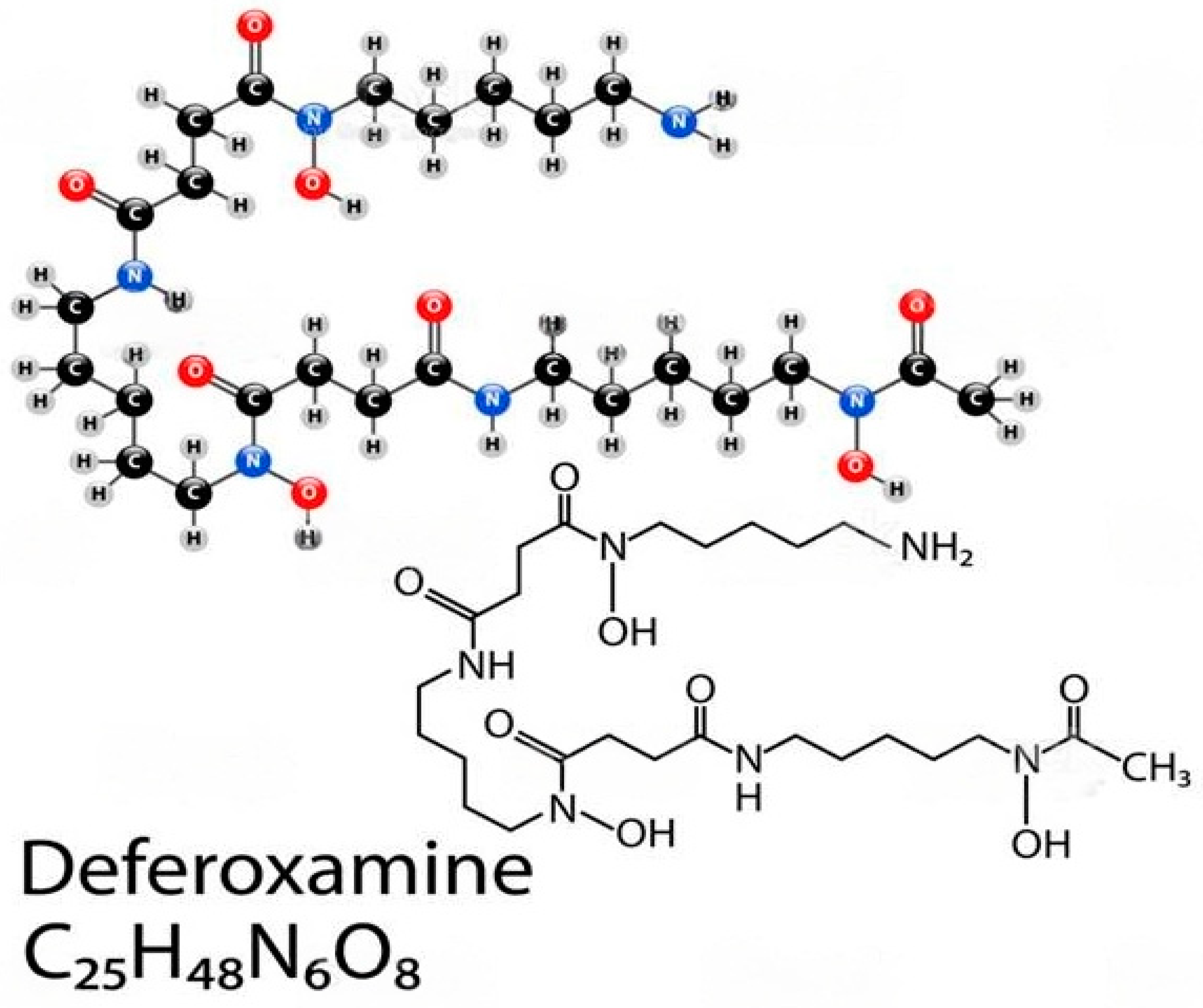

6.2. Deferoxamine (DFO)

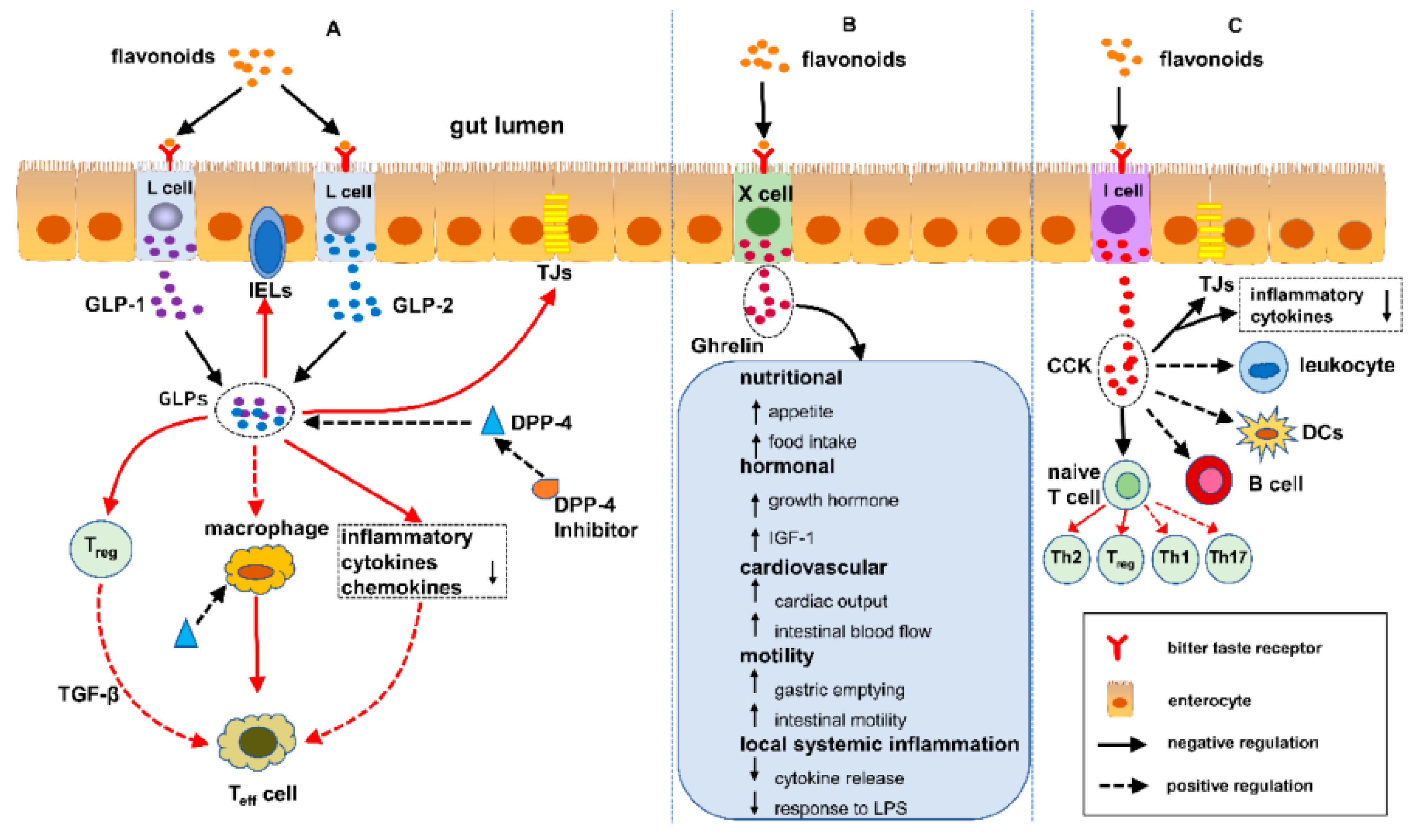

6.3. Flavonoids

7. Closing significance

8. Discussion

9. Significance

10. Ethical Considerations

Author Contributions

Funds acknowledgement

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

References

- Myers JN, Schaffer MW, Korolkova OY, Williams AD, Gangula PR, M'Koma AE. Implications of the Colonic Deposition of Free Hemoglobin-alpha Chain: A Previously Unknown Tissue By-product in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2014;20(9):1530-47. [CrossRef]

- Kruidenier L, Verspaget HW. Review article: oxidative stress as a pathogenic factor in inflammatory bowel disease--radicals or ridiculous? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(12):1997-2015. [CrossRef]

- D'Odorico A, Bortolan S, Cardin R, D'Inca R, Martines D, Ferronato A, et al. Reduced plasma antioxidant concentrations and increased oxidative DNA damage in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(12):1289-94. [CrossRef]

- Krzystek-Korpacka M, Neubauer K, Berdowska I, Boehm D, Zielinski B, Petryszyn P, et al. Enhanced formation of advanced oxidation protein products in IBD. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14(6):794-802. [CrossRef]

- Boehm D, Krzystek-Korpacka M, Neubauer K, Matusiewicz M, Berdowska I, Zielinski B, et al. Paraoxonase-1 status in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009;15(1):93-9. [CrossRef]

- Koutroubakis IE, Malliaraki N, Dimoulios PD, Karmiris K, Castanas E, Kouroumalis EA. Decreased total and corrected antioxidant capacity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(9):1433-7. [CrossRef]

- Babbs, CF. Oxygen radicals in ulcerative colitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13(2):169-81. [CrossRef]

- Caillet S, Yu, H., Lessard, S., Lamoureux, G., Ajdukovic, D., & Lacroix, M. Fenton reaction applied for screening natural antioxidants. Food Chemistry. 2007;100(2):542-52. [CrossRef]

- de Lacerda TC, Costa-Silva B, Giudice FS, Dias MV, de Oliveira GP, Teixeira BL, et al. Prion protein binding to HOP modulates the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2016;33(5):441-51. [CrossRef]

- Nopel-Dunnebacke S, Conradi LC, Reinacher-Schick A, Ghadimi M. [Influence of molecular markers on oncological surgery of colorectal cancer]. Chirurg. 2021;92(11):986-95. [CrossRef]

- Ewing I, Hurley JJ, Josephides E, Millar A. The molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5(1):26-30. [CrossRef]

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Raj JP. Role of biologics and biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: current trends and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:215-26. [CrossRef]

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89-103. [CrossRef]

- M'Koma AE, Moses HL, Adunyah SE. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: proctocolectomy andmucosectomy does not necessarily eliminate pouch related cancer incidences. Int J colorect Dis. 2011;26:533-52. [CrossRef]

- Marynczak K, Wlodarczyk J, Sabatowska Z, Dziki A, Dziki L, Wlodarczyk M. Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in a Tertiary Referral Center: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Lucafo M, Curci D, Franzin M, Decorti G, Stocco G. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: An Overview From Pathophysiology to Pharmacological Prevention. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:772101. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt M, Greten FR. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(10):653-67. [CrossRef]

- M'Koma, AE. The Multifactorial Etiopathogeneses Interplay of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview. Gastrointest Disord. 2018;1(1):75-105. [CrossRef]

- Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, Ng SC, Alberts R, Takahashi A, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):979-86. [CrossRef]

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749-53. [CrossRef]

- Spekhorst LM, Visschedijk MC, Alberts R, Festen EA, van der Wouden EJ, Dijkstra G, et al. Performance of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(41):15374-81. [CrossRef]

- Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(1):423-39. [CrossRef]

- Kofla-Dlubacz A, Pytrus T, Akutko K, Sputa-Grzegrzolka P, Piotrowska A, Dziegiel P. Etiology of IBD-Is It Still a Mystery? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20). [CrossRef]

- Pena-Sanchez JN, Osei JA, Marques Santos JD, Jennings D, Andkhoie M, Brass C, et al. Increasing Prevalence and Stable Incidence Rates of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among First Nations: Population-Based Evidence From a Western Canadian Province. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2022;28(4):514-22. [CrossRef]

- Jones GR, Lyons M, Plevris N, Jenkinson PW, Bisset C, Burgess C, et al. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut. 2019;68(11):1953-60. [CrossRef]

- M'Koma, AE. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Expanding Global Health Problem. Clinical Medicine Insights Gastroenterology. 2013(6):33-47. [CrossRef]

- Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, Guttmann A, Nguyen GC, Mojaverian N, Quach P, et al. Changing age demographics of inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study of epidemiology trends. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2014;20(10):1761-9. [CrossRef]

- Krzesiek E, Kofla-Dlubacz A, Akutko K, Stawarski A. The Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Paediatric Population in the District of Lower Silesia, Poland. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021;10(17). [CrossRef]

- Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1785-94. [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Changing Global Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Sustaining Health Care Delivery Into the 21st Century. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(6):1252-60. [CrossRef]

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-78. [CrossRef]

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390(10114):2769-78. [CrossRef]

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn's and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-65 e2. [CrossRef]

- Archampong TN, Nkrumah KN. Inflammatory bowel disease in Accra: what new trends. West Afr J Med. 2013;32(1):40-4.

- Ukwenya AY, Ahmed A, Odigie VI, Mohammed A. Inflammatory bowel disease in Nigerians: still a rare diagnosis? Ann Afr Med. 2011;10(2):175-9.

- Agoda-Koussema LK, Anoukoum T, Djibril AM, Balaka A, Folligan K, Adjenou V, et al. [Ulcerative colitis: a case in Togo]. Med Sante Trop. 2012;22(1):79-81. [CrossRef]

- Mebazaa A, Aounallah A, Naija N, Cheikh Rouhou R, Kallel L, El Euch D, et al. Dermatologic manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease in Tunisia. Tunis Med. 2012;90(3):252-7.

- Senbanjo IO, Oshikoya KA, Onyekwere CA, Abdulkareem FB, Njokanma OF. Ulcerative colitis in a Nigerian girl: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:564. [CrossRef]

- Bouzid D, Fourati H, Amouri A, Marques I, Abida O, Haddouk S, et al. The CREM gene is involved in genetic predisposition to inflammatory bowel disease in the Tunisian population. Human immunology. 2011;72(12):1204-9. [CrossRef]

- O'Keefe EA, Wright JP, Froggatt J, Cuming L, Elliot M. Medium-term follow-up of ulcerative colitis in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 1989;76(4):142-5.

- O'Keefe EA, Wright JP, Froggatt J, Zabow D. Medium-term follow-up of Crohn's disease in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 1989;76(4):139-41.

- Segal, I. Ulcerative colitis in a developing country of Africa: the Baragwanath experience of the first 46 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3(4):222-5. [CrossRef]

- Segal I, Tim LO, Hamilton DG, Walker AR. The rarity of ulcerative colitis in South African blacks. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74(4):332-6.

- Wright JP, Marks IN, Jameson C, Garisch JA, Burns DG, Kottler RE. Inflammatory bowel disease in Cape Town, 1975-1980. Part II. Crohn's disease. S Afr Med J. 1983;63(7):226-9.

- Wright JP, Marks IN, Jameson C, Garisch JA, Burns DG, Kottler RE. Inflammatory bowel disease in Cape Town, 1975-1980. Part I. Ulcerative colitis. S Afr Med J. 1983;63(7):223-6.

- Brom B, Bank S, Marks IN, Barbezat GO, Raynham B. Crohn's disease in the Cape: a follow-up study of 24 cases and a review of the diagnosis and management. S Afr Med J. 1968;42(41):1099-107.

- Novis BH, Marks IN, Bank S, Louw JH. Incidence of Crohn's disease at Groote Schuur Hospital during 1970-1974. S Afr Med J. 1975;49(17):693-7.

- Sobel JD, Schamroth L. Ulcerative colitis in the South African Bantu. Gut. 1970;11(9):760-3. [CrossRef]

- Giraud RM, Luke I, Schmaman A. Crohn's disease in the Transvaal Bantu: a report of 5 cases. S Afr Med J. 1969;43(21):610-3.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Kwon J, Raffals L, Sands B, Stenson WF, McGovern D, et al. Variation in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at major referral centers in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1197-200. [CrossRef]

- Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1907-13. [CrossRef]

- Siegmund B, Zeitz M. [Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy]. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47(10):1069-74. [CrossRef]

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46-54 e42; quiz e30. [CrossRef]

- Chouraki V, Savoye G, Dauchet L, Vernier-Massouille G, Dupas JL, Merle V, et al. The changing pattern of Crohn's disease incidence in northern France: a continuing increase in the 10- to 19-year-old age bracket (1988-2007). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(10):1133-42. [CrossRef]

- Shmidt E, Dubinsky MC. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10s):60-8. [CrossRef]

- Baiocco PJ, Korelitz BI. The influence of inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment on pregnancy and fetal outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6(3):211-6.

- Heetun ZS, Byrnes C, Neary P, O'Morain C. Review article: Reproduction in the patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(4):513-33. [CrossRef]

- Vermeire S, Carbonnel F, Coulie PG, Geenen V, Hazes JM, Masson PL, et al. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(8):811-23. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen C, Paerregaard A, Munkholm P, Faerk J, Lange A, Andersen J, et al. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: increasing incidence, decreasing surgery rate, and compromised nutritional status: A prospective population-based cohort study 2007-2009. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(12):2541-50. [CrossRef]

- North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology H, Nutrition, Colitis Foundation of A, Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(5):653-74. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, AM. Specificities of inflammatory bowel disease in childhood. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18(3):509-23. [CrossRef]

- Wang YR, Loftus EV, Jr., Cangemi JR, Picco MF. Racial/Ethnic and regional differences in the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Digestion. 2013;88(1):20-5. [CrossRef]

- Afzali A, Cross RK. Racial and Ethnic Minorities with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States: A Systematic Review of Disease Characteristics and Differences. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016;22(8):2023-40. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Collins B, Velayos FS, Liu L, Lewis JD, Allison JE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization and outcomes among ulcerative colitis patients in an integrated health-care organization. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(2):287-94. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda G, Liu B, Torres S, Bhuket T, Wong RJ. Race/Ethnicity-Specific Disparities in the Severity of Disease at Presentation in Adults with Ulcerative Colitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2876-81. [CrossRef]

- Avalos DJ, Mendoza-Ladd A, Zuckerman MJ, Bashashati M, Alvarado A, Dwivedi A, et al. Hispanic Americans and Non-Hispanic White Americans Have a Similar Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(6):1558-71. [CrossRef]

- Hou JK, El-Serag H, Thirumurthi S. Distribution and manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(8):2100-9. [CrossRef]

- Ventham NT, Kennedy NA, Nimmo ER, Satsangi J. Beyond gene discovery in inflammatory bowel disease: the emerging role of epigenetics. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):293-308. [CrossRef]

- Price, AB. Overlap in the spectrum of non-specific inflammatory bowel disease--'colitis indeterminate'. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31(6):567-77. [CrossRef]

- Farmer M, Petras RE, Hunt LE, Janosky JE, Galandiuk S. The importance of diagnostic accuracy in colonic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(11):3184-8. [CrossRef]

- Kader HA, Tchernev VT, Satyaraj E, Lejnine S, Kotler G, Kingsmore SF, et al. Protein microarray analysis of disease activity in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease demonstrates elevated serum PLGF, IL-7, TGF-beta1, and IL-12p40 levels in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients in remission versus active disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):414-23. [CrossRef]

- Burczynski ME, Peterson RL, Twine NC, Zuberek KA, Brodeur BJ, Casciotti L, et al. Molecular classification of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients using transcriptional profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8(1):51-61. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima K, Yonezawa H, Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells by differential cDNA screening and mRNA display. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2003;9(5):290-301. [CrossRef]

- Shkoda A, Werner T, Daniel H, Gunckel M, Rogler G, Haller D. Differential protein expression profile in the intestinal epithelium from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(3):1114-25. [CrossRef]

- M'Koma AE, Moses HL, Adunyah SE. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: proctocolectomy andmucosectomy does not necessarily eliminate pouch related cancer incidences. Int J colorect Dis. 2011;26:533-52. [CrossRef]

- Hardy RG, Meltzer SJ, Jankowski JA. ABC of colorectal cancer. Molecular basis for risk factors. Bmj. 2000;321(7265):886-9. [CrossRef]

- Rubin DT, Parekh N. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: molecular and clinical considerations. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9(3):211-20. [CrossRef]

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526-35. [CrossRef]

- Harpaz N, Talbot IC. Colorectal cancer in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13(4):339-57.

- Rubio CA, Befrits R, Ljung T, Jaramillo E, Slezak P. Colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative colitis is decreasing in Scandinavian countries. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(4B):2921-4.

- Loftus EV, Jr. Epidemiology and risk factors for colorectal dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35(3):517-31. [CrossRef]

- Delaunoit T, Limburg PJ, Goldberg RM, Lymp JF, Loftus EV, Jr. Colorectal cancer prognosis among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3):335-42. [CrossRef]

- Keller DS, Windsor A, Cohen R, Chand M. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(1):3-13. [CrossRef]

- Khan MA, Hakeem AR, Scott N, Saunders RN. Significance of R1 resection margin in colon cancer resections in the modern era. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(11):943-53. [CrossRef]

- Canavan C, Abrams KR, Mayberry J. Meta-analysis: colorectal and small bowel cancer risk in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(8):1097-104. [CrossRef]

- Stidham RW, Higgins PDR. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(3):168-78. [CrossRef]

- Munkholm, P. Review article: the incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18 Suppl 2:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Axelrad JE, Lichtiger S, Yajnik V. Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: The role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(20):4794-801. [CrossRef]

- Baker AM, Cross W, Curtius K, Al Bakir I, Choi CR, Davis HL, et al. Evolutionary history of human colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gut. 2019;68(6):985-95. [CrossRef]

- Um JW, M'Koma AE. Pouch-related dysplasia and adenocarcinoma following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15(1):7-16. [CrossRef]

- Gallo G, Kotze PG, Spinelli A. Surgery in ulcerative colitis: When? How? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;32-33:71-8. [CrossRef]

- Yashiro, M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16389-97. [CrossRef]

- Stjarngrim J, Widman L, Schmidt PT, Ekbom A, Forsberg A. Post-endoscopy colorectal cancer after colectomy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a population-based register study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35(3):288-93. [CrossRef]

- Vleggaar FP, Lutgens MW, Oldenburg B, Schipper ME, Samsom M. [British and American screening guidelines inadequate for prevention of colorectal carcinoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2007;151(50):2787-91.

- M'Koma AE, Seeley EH, Wise PE, Washingtoin MK, Schwartz DA, Herline AJ, Muldon RL, Caprioli RM. Proteomic analysis of colonic submucosa differentiates Crohn's and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5 Suppl 1):A-349. [CrossRef]

- M'Koma AE, Seeley EH, Washington MK, Schwartz DA, Muldoon RL, Herline AJ, Wise PE, Caprioli RM. Proteomic profiling of mucosal and submucosal colonic tissues yields protein signatures that differentiate the inflammatory colitides. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(4):875-83. [CrossRef]

- Seeley EH, Washington MK, Caprioli RM, M'Koma AE. Proteomic patterns of colonic mucosal tissues delineate Crohn's colitis and ulcerative colitis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013;7(7-8):541-9. [CrossRef]

- Steed E, Balda MS, Matter K. Dynamics and functions of tight junctions. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(3):142-9. [CrossRef]

- Weber CR, Nalle SC, Tretiakova M, Rubin DT, Turner JR. Claudin-1 and claudin-2 expression is elevated in inflammatory bowel disease and may contribute to early neoplastic transformation. Lab Invest. 2008;88(10):1110-20. [CrossRef]

- Steed E, Rodrigues NT, Balda MS, Matter K. Identification of MarvelD3 as a tight junction-associated transmembrane protein of the occludin family. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:95. [CrossRef]

- Porter RJ, Arends MJ, Churchhouse AMD, Din S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Colorectal Cancer: Translational Risks from Mechanisms to Medicines. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(12):2131-41. [CrossRef]

- Zielinska AK, Salaga M, Siwinski P, Wlodarczyk M, Dziki A, Fichna J. Oxidative Stress Does Not Influence Subjective Pain Sensation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka M, Mrowicki J, Mik M, Dziki L, Dziki A, Majsterek I. Assessment of DNA damage profile and oxidative /antioxidative biomarker level in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pol Przegl Chir. 2020;92(5):8-15. [CrossRef]

- Kontoghiorghes GJ, Pattichi K, Hadjigavriel M, Kolnagou A. Transfusional iron overload and chelation therapy with deferoxamine and deferiprone (L1). Transfus Sci. 2000;23(3):211-23. [CrossRef]

- Szymonik J, Wala K, Gornicki T, Saczko J, Pencakowski B, Kulbacka J. The Impact of Iron Chelators on the Biology of Cancer Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Naryzny SN, Legina OK. Haptoglobin as a Biomarker. Biochem Mosc Suppl B Biomed Chem. 2021;15(3):184-98. [CrossRef]

- Wobeto VP, Zaccariotto, T. R., and Sonati, M. D. Polymorphism of human haptoglobin and its clinical importance. Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2008;31(3):602-220. [CrossRef]

- Marquez L, Cleynen, I., Machiels, K., Organe, S., Ferrante, M., Henckaerts. Haptoglobin Poymorphisms are Associated With Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease. Haptoglobin Poymorphisms are Associated With Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease. 2010;138(5).

- Tayari M, Afsharzadeh D. Amplification of antioxidant activity of haptoglobin(2-2)-hemoglobin at pathologic temperature and presence of antibiotics. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2012;27(2):171-7. [CrossRef]

- Marquez L, Shen, C., Machiels, K., Perrier, C., Ballet, V., Organe, S. Role of Haptoglobin in Susceptibility of IBD and in Triggering Murine Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5). [CrossRef]

- Meczynska S, Lewandowska H, Sochanowicz B, Sadlo J, Kruszewski M. Variable inhibitory effects on the formation of dinitrosyl iron complexes by deferoxamine and salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone in K562 cells.Hemoglobin. 2008;32:157-63. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese A, Martino EA, Mendicino F, Lucia E, Olivito V, Bova C, et al. Iron chelation therapy. Eur J Haematol. 2023;110(5):490-497. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Q, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhu Y, Jiao Y, Bao Y, Shi W. Cuscuta chinensis flavonoids reducing oxidative stress of the improve sperm damage in 35 bisphenol A exposed mice offspring. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;15:255:114831. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Yang W, Li Y, Cong Y. Enteroendocrine Cells: Sensing Gut Microbiota and Regulating Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2020;26(1):11-20. [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt RJ, van Nood E, van Hoorn DE, Boelens PG, van Norren K, van Leeuwen PA. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(4):418-25. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro D, Proenca C, Rocha S, Lima J, Carvalho F, Fernandes E, et al. Immunomodulatory Effects of Flavonoids in the Prophylaxis and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25(28):3374-412. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Weigmann B. A Novel Pathway of Flavonoids Protecting against Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Modulating Enteroendocrine System. Metabolites. 2022;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Hillier TA, Vesco KK, Pedula KL, Beil TL, Whitlock EP, Pettitt DJ. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):766-75. [CrossRef]

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, Rutter CM, Webber EM, O'Connor E, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 2016;315(23):2576-94. [CrossRef]

- Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 2021;325(19):1978-98. [CrossRef]

- Miller-Wilson LA, Limburg P, Helmueller L, Joao Janeiro M, Hartlaub P. The impact of multi-target stool DNA testing in clinical practice in the United States: A real-world evidence retrospective study. Prev Med Rep. 2022;30:102045. [CrossRef]

- Kim A, Gitlin M, Fadli E, McGarvey N, Cong Z, Chung KC. Breast, Colorectal, Lung, Prostate, and Cervical Cancer Screening Prevalence in a Large Commercial and Medicare Advantage Plan, 2008-2020. Prev Med Rep. 2022;30:102046. [CrossRef]

- Poulson MR, Geary A, Papageorge M, Laraja A, Sacks O, Hall J, et al. The effect of medicare and screening guidelines on colorectal cancer outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Meester RGS, Peterse EFP, Knudsen AB, de Weerdt AC, Chen JC, Lietz AP, et al. Optimizing colorectal cancer screening by race and sex: Microsimulation analysis II to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124(14):2974-85. [CrossRef]

- Peterse EFP, Meester RGS, Siegel RL, Chen JC, Dwyer A, Ahnen DJ, et al. The impact of the rising colorectal cancer incidence in young adults on the optimal age to start screening: Microsimulation analysis I to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer. 2018;124(14):2964-73. [CrossRef]

- Almario CV, May FP, Ponce NA, Spiegel BM. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Colonoscopic Examination of Individuals With a Family History of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(8):1487-95. [CrossRef]

- May FP, Almario CV, Ponce N, Spiegel BM. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1388-94. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, KB. Addressing Colorectal Cancer Disparities Among African American Men Beyond Traditional Practice-Based Settings. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1356-8. [CrossRef]

- Mehta SJ, Jensen CD, Quinn VP, Schottinger JE, Zauber AG, Meester R, et al. Race/Ethnicity and Adoption of a Population Health Management Approach to Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Community-Based Healthcare System. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1323-30. [CrossRef]

- Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):1033-46. [CrossRef]

- Lin TK, Erdman SH. Double-balloon Enteroscopy: Pediatric Experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010.

- Houghton J, Li H, Fan X, Liu Y, Liu JH, Rao VP, et al. Mutations in Bone Marrow-Derived Stromal Stem Cells Unmask Latent Malignancy. Stem Cells Dev. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt C, Bielecki C, Felber J, Stallmach A. Surveillance strategies in inflammatory bowel disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2010;56(2):189-201.

- Burrill, B. Crohn BB RH. The Sigmoidoscopic Picture of Chronic Ulcerative Colitis (Non-Specific). Am J Med Sci. 1925(170):220.

- Warren S, Sommers SC. Cicatrizing enteritis as a pathologic entity; analysis of 120 cases. Am J Pathol. 1948;24(3):475-501.

- Soderlund S, Brandt L, Lapidus A, Karlen P, Brostrom O, Lofberg R, et al. Decreasing time-trends of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):1561-7; quiz 818-9. [CrossRef]

- Itzkowitz SH, Present DH, Crohn's, Colitis Foundation of America Colon Cancer in IBDSG. Consensus conference: Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2005;11(3):314-21. [CrossRef]

- Barthet M, Gay G, Sautereau D, Ponchon T, Napoleo B, Boyer J, et al. Endoscopic surveillance of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2005;37(6):597-9. [CrossRef]

- Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):31-54. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-64. [CrossRef]

- Averboukh F, Ziv Y, Kariv Y, Zmora O, Dotan I, Klausner JM, et al. Colorectal carcinoma in inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison between Crohn's and ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(11):1230-5. [CrossRef]

- Sadrzadeh SM, Graf E, Panter SS, Hallaway PE, Eaton JW. Hemoglobin. A biologic fenton reagent. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1984;259(23):14354-6.

- Woodford, FP. Ethical experimentation and the editor. N Engl J Med. 1972;286(16):892. [CrossRef]

- Abe C, Miyazawa T, Miyazawa T. Current Use of Fenton Reaction in Drugs and Food. Molecules. 2022;27(17). [CrossRef]

- Ruan L, Wang M, Zhou M, Lu H, Zhang J, Gao J, et al. Doxorubicin-Metal Coordinated Micellar Nanoparticles for Intracellular Codelivery and Chemo/Chemodynamic Therapy in Vitro. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2019;2(11):4703-7. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Liu M, Cheng J, Yin J, Huang C, Cui H, et al. Acidity-Triggered Tumor-Targeted Nanosystem for Synergistic Therapy via a Cascade of ROS Generation and NO Release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(26):28975-84. [CrossRef]

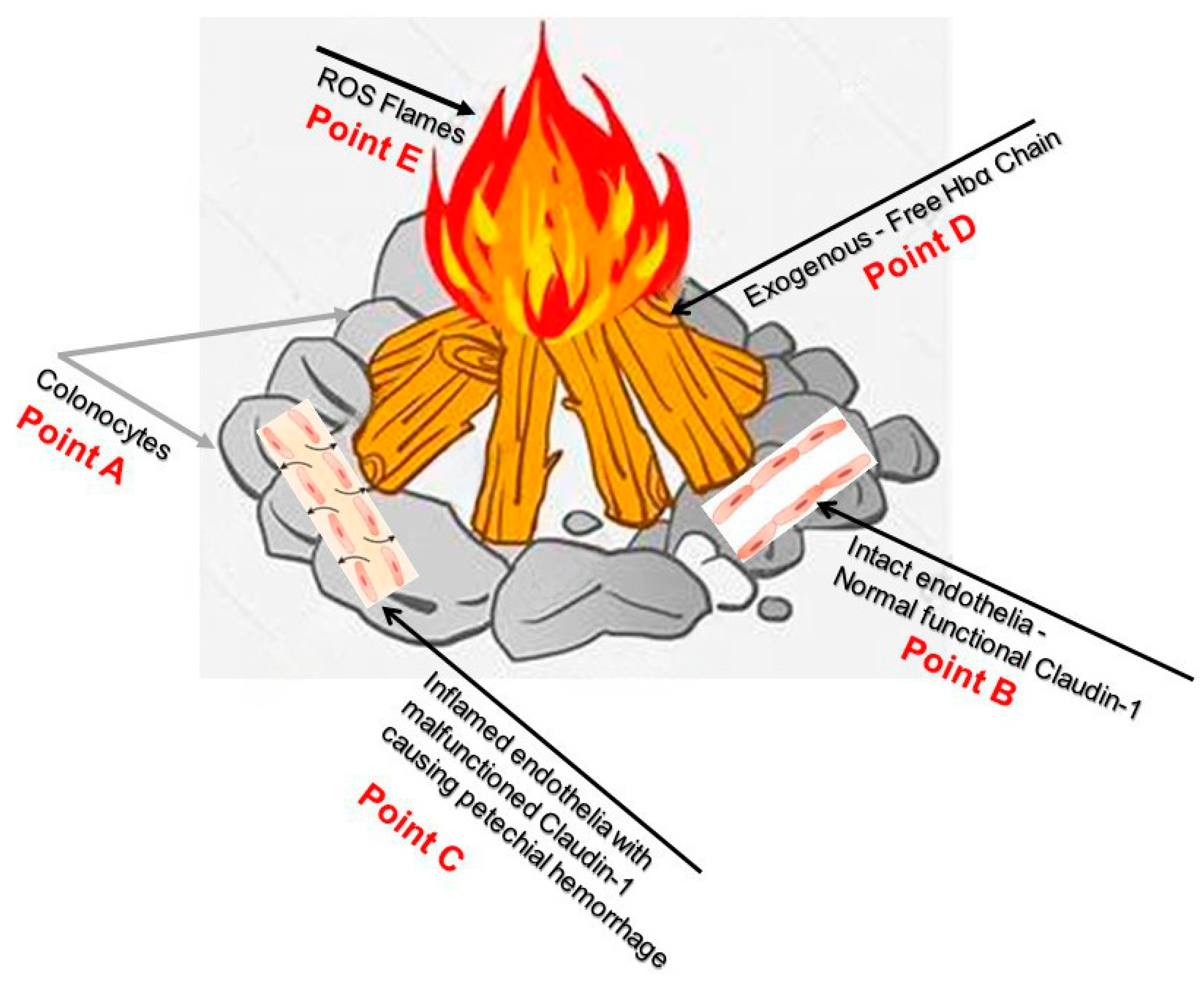

- Available online: https://www.shutterstock.com/create/editor/CiQ3YTEzMTI1YS0zOTdiLTQzNTAtOTE2ZC0yYWM5N2U0NmRlYWM.

- Bystrom LM, Guzman ML, Rivella S. Iron and reactive oxygen species: friends or foes of cancer cells? Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20(12):1917-24. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://pikbest.com/png-images/qianku-drawing-burning-wood-illustration_1963420.html.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).