Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. ROLE OF cAMP-PKA PATHWAY IN THE CELLULAR RESPONSE TO STRESS

2.1. Osmotic Stress and PKA

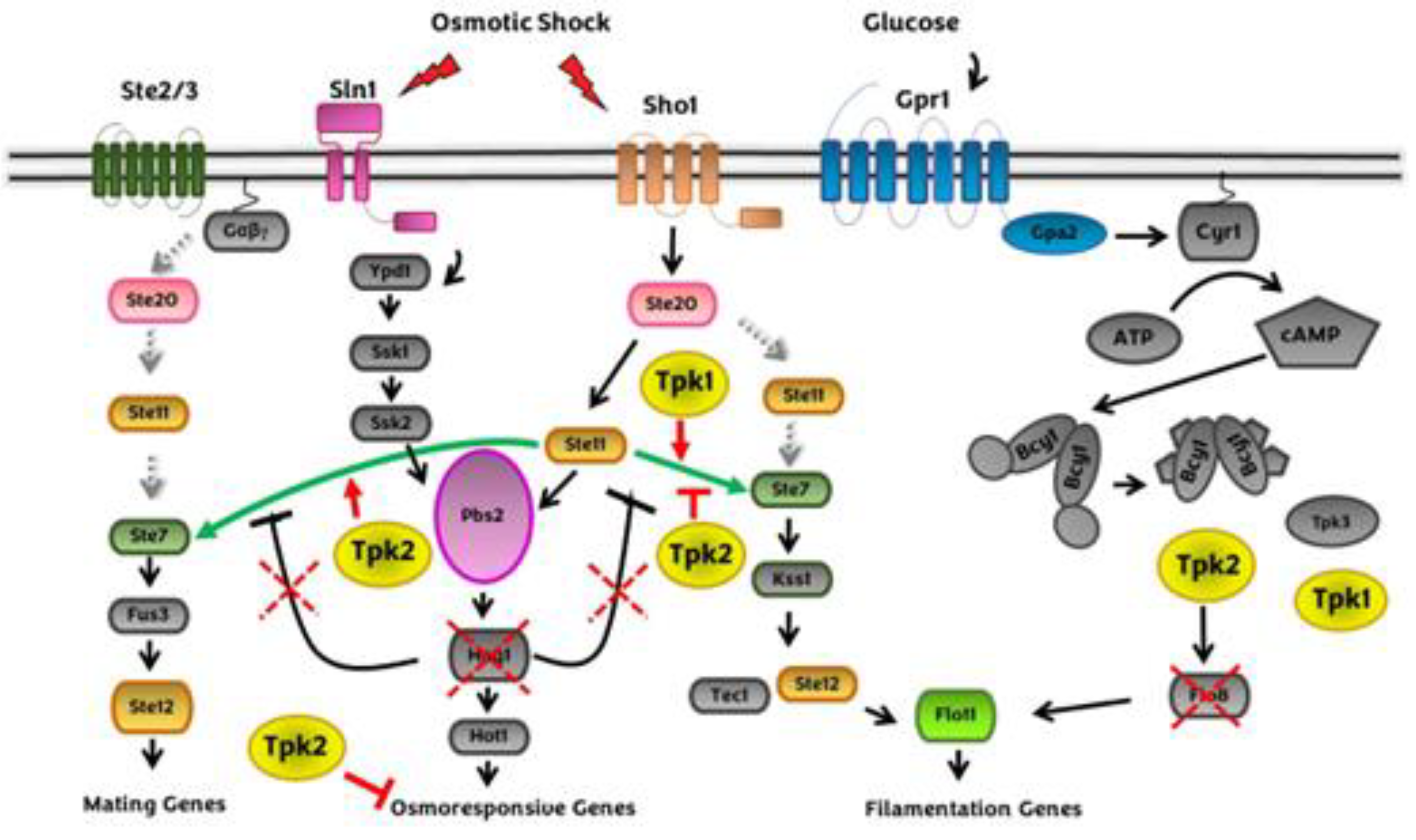

2.2. Crosstalk between cAMP-PKA and HOG MAPK pathway during osmostress

2.3. Thermal Stress and PKA

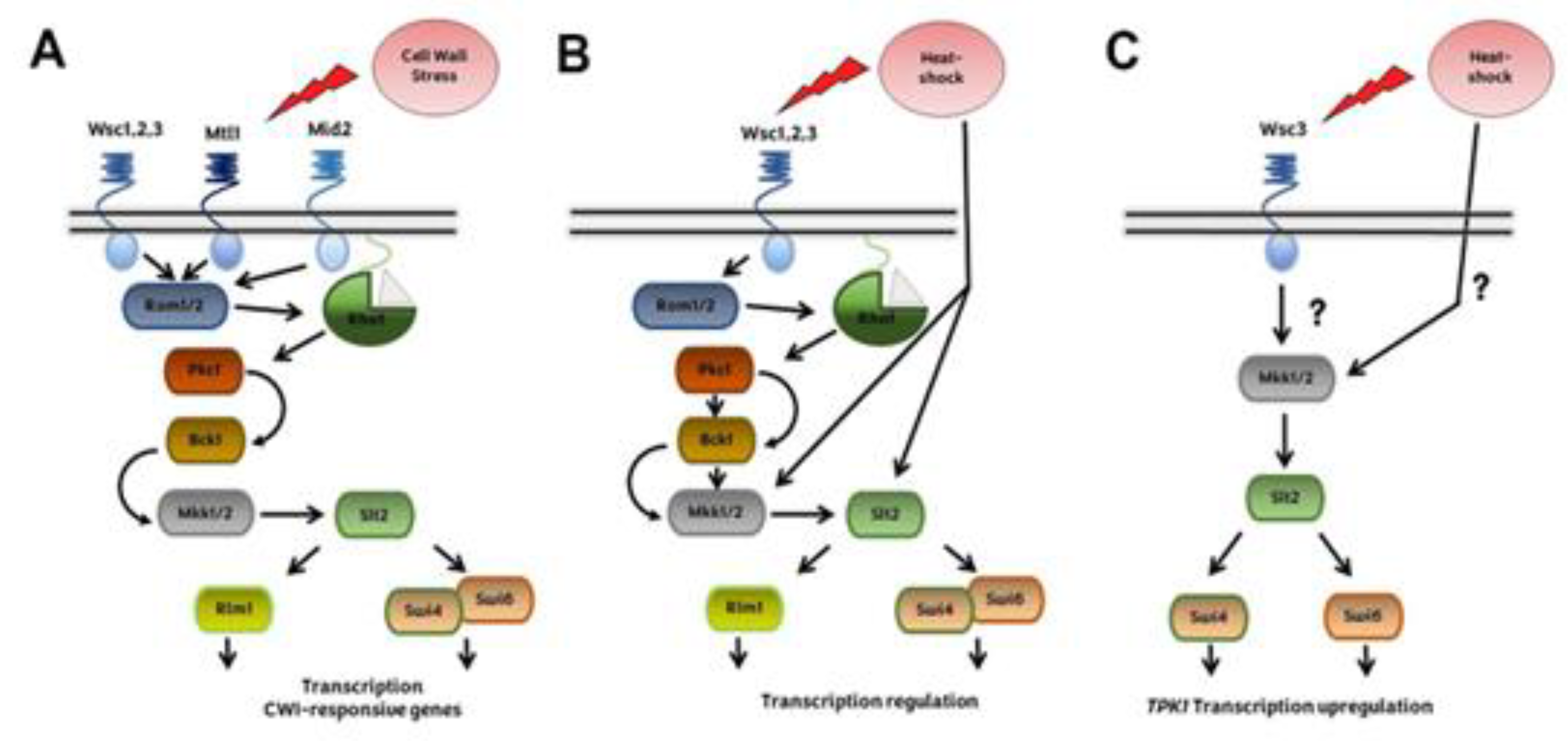

2.4. Crosstalk between cAMP-PKA and CWI pathways during heat stress

3. EFFECT OF STRESS ON THE SPECIFICITY REGULATION OF cAMP-PKA PATHWAY

3.1. PKA anchoring through Bcy1 interacting proteins

3.2. Subcellular localization of Tpk1, Tpk2 and Tpk3 catalytic isoforms

3.3. Transcriptional regulation of PKA subunits

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bleuven, C.; Landry, C.R. Molecular and Cellular Bases of Adaptation to a Changing Environment in Microorganisms. Proc Biol Sci 2016, 283. [CrossRef]

- Vanderwaeren, L.; Dok, R.; Voordeckers, K.; Nuyts, S.; Verstrepen, K.J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a Model System for Eukaryotic Cell Biology, from Cell Cycle Control to DNA Damage Response. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23, Page 11665 2022, 23, 11665. [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P. The Environmental Stress Response: A Common Yeast Response to Diverse Environmental Stresses. Yeast Stress Responses 2003, 11–70. [CrossRef]

- Chasman, D.; Ho, Y.-H.; Berry, D.B.; Nemec, C.M.; MacGilvray, M.E.; Hose, J.; Merrill, A.E.; Lee, M.V.; Will, J.L.; Coon, J.J.; et al. Pathway Connectivity and Signaling Coordination in the Yeast Stress-Activated Signaling Network. Mol Syst Biol 2014, 10, 759. [CrossRef]

- Święciło, A. Cross-Stress Resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Yeast--New Insight into an Old Phenomenon. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Haroon, S.; Bravo, D.G.; Will, J.L.; Gasch, A.P. Cellular Memory of Acquired Stress Resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 192, 495–505. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, C.; Mazzoni, C. External and Internal Triggers of Cell Death in Yeast. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 2237–2250. [CrossRef]

- Grosfeld, E. V.; Bidiuk, V.A.; Mitkevich, O. V.; Ghazy, E.S.M.O.; Kushnirov, V. V.; Alexandrov, A.I. A Systematic Survey of Characteristic Features of Yeast Cell Death Triggered by External Factors. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qian, H. Sensitivity and Specificity Amplification in Signal Transduction. Cell Biochem Biophys 2003, 39, 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.E.; Ingham, P.W.; Lim, W.A.; Marshall, C.J.; Massagué, J.; Pawson, T. Signalling Change: Signal Transduction through the Decades. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 393–398. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Yaffe, M.B. Protein Regulation in Signal Transduction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Pawson, C.T.; Scott, J.D. Signal Integration through Blending, Bolstering and Bifurcating of Intracellular Information. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17, 653–658. [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Hall, M.N. Nutrient Sensing and TOR Signaling in Yeast and Mammals. EMBO J 2017, 36, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Chasman, D.; Ho, Y.; Berry, D.B.; Nemec, C.M.; MacGilvray, M.E.; Hose, J.; Merrill, A.E.; Lee, M.V.; Will, J.L.; Coon, J.J.; et al. Pathway Connectivity and Signaling Coordination in the Yeast Stress-Activated Signaling Network. Mol Syst Biol 2014, 10, 759. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Kornev, A.P.; Wu, J.; Taylor, S.S. Discovery of Allostery in PKA Signaling. Biophys Rev 2015, 7, 227–238. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.S.; Wu, J.; Bruystens, J.G.H.; Del Rio, J.C.; Lu, T.W.; Kornev, A.P.; Ten Eyck, L.F. From Structure to the Dynamic Regulation of a Molecular Switch: A Journey over 3 Decades. J Biol Chem 2021, 296. [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Cameron, S.; Sass, P.; Zoller, M.; Wigler, M. Three Different Genes in S. cerevisiae Encode the Catalytic Subunits of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Cell 1987, 50, 277–287.

- Rubio-Texeira, M.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Voordeckers, K.; Thevelein, J.M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Plasma Membrane Nutrient Sensors and Their Role in PKA Signaling. FEMS Yeast Res 2010, 10, 134–149. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Schothorst, J.; Kankipati, H.N.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Rubio-Texeira, M.; Thevelein, J.M. Nutrient Sensing and Signaling in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014, 38, 254–299. [CrossRef]

- Thevelein, J.M.; Geladé, R.; Holsbeeks, I.; Lagatie, O.; Popova, Y.; Rolland, F.; Stolz, F.; Van de Velde, S.; Van Dijck, P.; Vandormael, P.; et al. Nutrient Sensing Systems for Rapid Activation of the Protein Kinase A Pathway in Yeast. Biochem Soc Trans 2005, 33, 253–256. [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.; Gasch, A. Stress-Activated Genomic Expression Changes Serve a Preparative Role for Impending Stress in Yeast. Mol Biol Cell 2008, 19, 4580 – 4587. [CrossRef]

- Gancedo, J.M. The Early Steps of Glucose Signalling in Yeast. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008, 32, 673–704. [CrossRef]

- Palecek, S.P.; Parikh, A.S.; Kron, S.J. Sensing, Signalling and Integrating Physical Processes during Saccharomyces cerevisiae Invasive and Filamentous Growth. Microbiology (Reading) 2002, 148, 893–907.

- Portela, P.; Rossi, S. CAMP-PKA Signal Transduction Specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 2020, 66, 1093–1099. [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.M. Glucose Signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2006, 70, 253–282. [CrossRef]

- Causton, H.C.; Ren, B.; Koh, S.S.; Harbison, C.T.; Kanin, E.; Jennings, E.G.; Lee, T.I.; True, H.L.; Lander, E.S.; Young, R.A. Remodeling of Yeast Genome Expression in Response to Environmental Changes. Mol Biol Cell 2001, 12, 323–337.

- Gasch, A.P.; Werner-Washburne, M. The Genomics of Yeast Responses to Environmental Stress and Starvation. Funct Integr Genomics 2002, 2, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Winkler, S.; Schlottmann, F.P.; Kohlbacher, O.; Elias, J.E.; Skotheim, J.M.; Ewald, J.C. Multiple Layers of Phospho-Regulation Coordinate Metabolism and the Cell Cycle in Budding Yeast. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 338. [CrossRef]

- Grossbach, J.; Gillet, L.; Cl Ement-Ziza, M.; Schmalohr, C.L.; Schubert, O.T.; Sch€ Utter, M.; Mawer, J.S.P.; Barnes, C.A.; Bludau, I.; Weith, M.; et al. The Impact of Genomic Variation on Protein Phosphorylation States and Regulatory Networks. Mol Syst Biol 2022, 18, e10712. [CrossRef]

- Kanshin, E.; Kubiniok, P.; Thattikota, Y.; Amours, D.D.’; Thibault, P. Phosphoproteome Dynamics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under Heat Shock and Cold Stress. Mol Syst Biol 2015, 11, 813. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S.; Mager, W.H. Yeast Stress Responses; Springer, 2003; ISBN 9783540456117.

- Ruis, H.; Schüller, C. Stress Signaling in Yeast. Bioessays 1995, 17, 959–965. [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Beniwal, A.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Vij, S. Response and Tolerance of Yeast to Changing Environmental Stress during Ethanol Fermentation. Process Biochemistry 2018, 72, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Thevelein, J.M.; De Winde, J.H. Novel Sensing Mechanisms and Targets for the CAMP–Protein Kinase A Pathway in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 1999, 33, 904–918. [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Bradshaw-Rouse, J.; Markwardt, D.; Heideman, W. Changes in Gene Expression in the Ras/Adenylate Cyclase System of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Correlation with CAMP Levels and Growth Arrest. Mol Biol Cell 1993, 4, 757–765. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Ward, M.P.; Garrett, S. Yeast PKA Represses Msn2p/Msn4p-Dependent Gene Expression to Regulate Growth, Stress Response and Glycogen Accumulation. EMBO Journal 1998, 17, 3556–3564. [CrossRef]

- Boy-Marcotte, E.; Garreau, H.; Jacquet, M. Cyclic AMP Controls the Switch between Division Cycle and Resting State Programs in Response to Ammonium Availability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1987, 3, 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Durchschlag, E.; Reiter, W.; Ammerer, G.; Schüller, C. Nuclear Localization Destabilizes the Stress-Regulated Transcription Factor Msn2. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 55425–55432. [CrossRef]

- Görner, W.; Durchschlag, E.; Martinez-Pastor, M.T.; Estruch, F.; Ammerer, G.; Hamilton, B.; Ruis, H.; Schüller, C. Nuclear Localization of the C2H2 Zinc Finger Protein Msn2p Is Regulated by Stress and Protein Kinase A Activity. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 586–597. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Dalal, C.K.; Elowitz, M.B. Frequency-Modulated Nuclear Localization Bursts Coordinate Gene Regulation. Nature 2008 455:7212 2008, 455, 485–490. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia-Torres, C.; Goldbeter, A.; Jacquet, M. Nucleocytoplasmic Oscillations of the Yeast Transcription Factor Msn2: Evidence for Periodic PKA Activation. Curr Biol 2007, 17, 1044–1049. [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, M.; Renault, G.; Lallet, S.; De Mey, J.; Goldbeter, A. Oscillatory Behavior of the Nuclear Localization of the Transcription Factors Msn2 and Msn4 in Response to Stress in Yeast. ScientificWorldJournal 2003, 3, 609–612. [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, A.; Movshovich, N.; Volokh, M.; Gheber, L.; Aharoni, A. Fine-Tuning of the Msn2/4-Mediated Yeast Stress Responses as Revealed by Systematic Deletion of Msn2/4 Partners. Mol Biol Cell 2011, 22, 3127–3138. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Lippman, S.I.; Zhao, X.; Broach, J.R. How Saccharomyces Responds to Nutrients. Annu Rev Genet 2008, 42, 27–81. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S. An Integrated View on a Eukaryotic Osmoregulation System. Curr Genet 2015, 61, 373–382. [CrossRef]

- Tamás, M.J.; Karlgren, S.; Bill, R.M.; Hedfalk, K.; Allegri, L.; Ferreira, M.; Thevelein, J.M.; Rydström, J.; Mullins, J.G.L.; Hohmann, S. A Short Regulatory Domain Restricts Glycerol Transport through Yeast Fps1p. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 6337–6345. [CrossRef]

- Tamás, M.J.; Luyten, K.; Sutherland, F.C.W.; Hernandez, A.; Albertyn, J.; Valadi, H.; Li, H.; Prior, B.A.; Kilian, S.G.; Ramos, J.; et al. Fps1p Controls the Accumulation and Release of the Compatible Solute Glycerol in Yeast Osmoregulation. Mol Microbiol 1999, 31, 1087–1104. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Tatebayashi, K.; Nishimura, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Yang, H.Y.; Saito, H. Yeast Osmosensors Hkr1 and Msb2 Activate the Hog1 MAPK Cascade by Different Mechanisms. Sci Signal 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Macia, J.; Regot, S.; Peeters, T.; Conde, N.; Solé, R.; Posas, F. Dynamic Signaling in the Hog1 MAPK Pathway Relies on High Basal Signal Transduction. Sci Signal 2009, 2. [CrossRef]

- Raitt, D.C.; Posas, F.; Saito, H. Yeast Cdc42 GTPase and Ste20 PAK-like Kinase Regulate Sho1-Dependent Activation of the Hog1 MAPK Pathway. EMBO J 2000, 19, 4623–4631. [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Tatebayashi, K. Regulation of the Osmoregulatory HOG MAPK Cascade in Yeast. J Biochem 2004, 136, 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Ibarra, A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, G.; Guerrero-Serrano, G.; Kawasaki, L.; Ongay-Larios, L.; Coria, R. Negative Feedback-Loop Mechanisms Regulating HOG- and Pheromone-MAPK Signaling in Yeast. Curr Genet 2020, 66, 867–880. [CrossRef]

- Brewster, J.L.; De Valoir, T.; Dwyer, N.D.; Winter, E.; Gustin, M.C. An Osmosensing Signal Transduction Pathway in Yeast. Science 1993, 259, 1760–1763. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Takekawa, M.; Saito, H. Activation of Yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by Binding of an SH3-Containing Osmosensor. Science 1995, 269, 554–558. [CrossRef]

- Posas, F.; Saito, H. Osmotic Activation of the HOG MAPK Pathway via Ste11p MAPKKK: Scaffold Role of Pbs2p MAPKK. Science 1997, 276, 1702–1708. [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Posas, F. Response to Hyperosmotic Stress. Genetics 2012, 192, 289–318. [CrossRef]

- Tatebayashi, K.; Saito, H. Two Activating Phosphorylation Sites of Pbs2 MAP2K in the Yeast HOG Pathway Are Differentially Dephosphorylated by Four PP2C Phosphatases Ptc1-Ptc4. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 104569. [CrossRef]

- Ferrigno, P.; Posas, F.; Koepp, D.; Saito, H.; Silver, P.A. Regulated Nucleo/Cytoplasmic Exchange of HOG1 MAPK Requires the Importin Beta Homologs NMD5 and XPO1. EMBO J 1998, 17, 5606–5614. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.K.; Lambert, I.H.; Pedersen, S.F. Physiology of Cell Volume Regulation in Vertebrates. Physiol Rev 2009, 89, 193–277. [CrossRef]

- Alepuz, P.M.; Jovanovic, A.; Reiser, V.; Ammerer, G. Stress-Induced Map Kinase Hog1 Is Part of Transcription Activation Complexes. Mol Cell 2001, 7, 767–777. [CrossRef]

- Gomar-Alba, M.; Alepuz, P.; Del Olmo, M. Dissection of the Elements of Osmotic Stress Response Transcription Factor Hot1 Involved in the Interaction with MAPK Hog1 and in the Activation of Transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1829, 1111–1125. [CrossRef]

- Rep, M.; Krantz, M.; Thevelein, J.M.; Hohmann, S. The Transcriptional Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Osmotic Shock. Hot1p and Msn2p/Msn4p Are Required for the Induction of Subsets of High Osmolarity Glycerol Pathway-Dependent Genes. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 8290–8300. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Song, Y.S.; Yosef, N.; Iulio, J. di; Stirling Churchman, L.; Choder, M. The Yeast Exoribonuclease Xrn1 and Associated Factors Modulate RNA Polymerase II Processivity in 5’ and 3’ Gene Regions. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 11435–11454. [CrossRef]

- Proft, M.; Struhl, K. Hog1 Kinase Converts the Sko1-Cyc8-Tup1 Repressor Complex into an Activator That Recruits SAGA and SWI/SNF in Response to Osmotic Stress. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 1307–1317. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Chang, Y.W.; Li, W.H. Experimental Evolution of Yeast for High-Temperature Tolerance. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1823–1839. [CrossRef]

- Klopf, E.; Schmidt, H.A.; Clauder-Münster, S.; Steinmetz, L.M.; Schüller, C. INO80 Represses Osmostress Induced Gene Expression by Resetting Promoter Proximal Nucleosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, 3752–3766. [CrossRef]

- Norbeck, J.; Blomberg, A. The Level of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase A Activity Strongly Affects Osmotolerance and Osmo-Instigated Gene Expression Changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2000, 16, 121–137. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S. Osmotic Adaptation in Yeast-Control of the Yeast Osmolyte System. Int Rev Cytol 2002, 215, 149–187. [CrossRef]

- W, G.; E, D.; MT, M.-P.; F, E.; G, A.; B, H.; H, R.; C, S. Nuclear Localization of the C2H2 Zinc Finger Protein Msn2p Is Regulated by Stress and Protein Kinase A Activity. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 586–597. [CrossRef]

- González-Rubio, G.; Sellers-Moya, A.; Martín, H.; Molina, M. A Walk-through MAPK Structure and Functionality with the 30-Year-Old Yeast MAPK Slt2. Int Microbiol 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lallet, S.; Garreau, H.; Garmendia-Torres, C.; Szestakowska, D.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Quevillon-Chéruel, S.; Jacquet, M. Role of Gal11, a Component of the RNA Polymerase II Mediator in Stress-Induced Hyperphosphorylation of Msn2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 2006, 62, 438–452. [CrossRef]

- Garreau, H.; Hasan, R.N.; Renault, G.; Estruch, F.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Jacquet, M. Hyperphosphorylation of Msn2p and Msn4p in Response to Heat Shock and the Diauxic Shift Is Inhibited by CAMP in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology (Reading) 2000, 146 ( Pt 9), 2113–2120. [CrossRef]

- Boy-Marcotte, E.; Perrot, M.; Bussereau, F.; Boucherie, H.; Jacquet, M. Msn2p and Msn4p Control a Large Number of Genes Induced at the Diauxic Transition Which Are Repressed by Cyclic AMP in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 1998, 180, 1044–1052. [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Cho, B.R.; Joo, H.S.; Hahn, J.S. Yeast Yak1 Kinase, a Bridge between PKA and Stress-Responsive Transcription Factors, Hsf1 and Msn2/Msn4. Mol Microbiol 2008, 70, 882–895. [CrossRef]

- Rep, M.; Krantz, M.; Thevelein, J.M.; Hohmann, S. The Transcriptional Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Osmotic Shock. Hot1p and Msn2p/Msn4p Are Required for the Induction of Subsets of High Osmolarity Glycerol Pathway-Dependent Genes. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 8290–8300. [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, A.P.; Kaplan, T.; Liu, Y.; Habib, N.; Regev, A.; Friedman, N.; O’shea, E.K. Structure and Function of a Transcriptional Network Activated by the MAPK Hog1. Nat Genet 2008, 40, 1300–1306. [CrossRef]

- Pokholok, D.K.; Zeitlinger, J.; Hannett, N.M.; Reynolds, D.B.; Young, R.A. Activated Signal Transduction Kinases Frequently Occupy Target Genes. Science 2006, 313, 533–536. [CrossRef]

- De Nadal, E.; Zapater, M.; Alepuz, P.M.; Sumoy, L.; Mas, G.; Posas, F. The MAPK Hog1 Recruits Rpd3 Histone Deacetylase to Activate Osmoresponsive Genes. Nature 2004, 427, 370–374. [CrossRef]

- Baccarini, L.; Martínez-Montañés, F.; Rossi, S.; Proft, M.; Portela, P. PKA-Chromatin Association at Stress Responsive Target Genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2015, 1849, 1329–1339. [CrossRef]

- Vert, G.; Chory, J. Crosstalk in Cellular Signaling: Background Noise or the Real Thing? Dev Cell 2011, 21, 985. [CrossRef]

- González-Rubio, G.; Fernández-Acero, T.; Martín, H.; Molina, M. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Phosphatases (MKPs) in Fungal Signaling: Conservation, Function, and Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Chavel, C.A.; Caccamise, L.M.; Li, B.; Cullen, P.J. Global Regulation of a Differentiation MAPK Pathway in Yeast. Genetics 2014, 198, 1309–1328. [CrossRef]

- Baltanás, R.; Bush, A.; Couto, A.; Durrieu, L.; Hohmann, S.; Colman-Lerner, A. Pheromone-Induced Morphogenesis Improves Osmoadaptation Capacity by Activating the HOG MAPK Pathway. Sci Signal 2013, 6. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, S.M.; Herskowitz, I. The Hog1 MAPK Prevents Cross Talk between the HOG and Pheromone Response MAPK Pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 2874–2886. [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.E. Regulation of Cell Wall Biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: The Cell Wall Integrity Signaling Pathway. Genetics 2011, 189, 1145–1175. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gutiérrez, E.; Alegría-Carrasco, E.; Sellers-Moya, A.; Molina, M.; Martín, H. Not Just the Wall: The Other Ways to Turn the Yeast CWI Pathway On. Int Microbiol 2020, 23, 107–119. [CrossRef]

- Birkaya, B.; Maddi, A.; Joshi, J.; Free, S.J.; Cullen, P.J. Role of the Cell Wall Integrity and Filamentous Growth Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways in Cell Wall Remodeling during Filamentous Growth. Eukaryot Cell 2009, 8, 1118–1133. [CrossRef]

- Buehrer, B.M.; Errede, B. Coordination of the Mating and Cell Integrity Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 6517–6525. [CrossRef]

- Zarzov, P.; Mazzoni, C.; Mann, C. The SLT2(MPK1) MAP Kinase Is Activated during Periods of Polarized Cell Growth in Yeast. EMBO J 1996, 15, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Urita, A.; Ishibashi, Y.; Kawaguchi, R.; Yanase, Y.; Tani, M. Crosstalk between Protein Kinase A and the HOG Pathway under Impaired Biosynthesis of Complex Sphingolipids in Budding Yeast. FEBS J 2022, 289, 766–786. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda LE Interaction between the CAMP-PKA and HOG-MAPK Pathways in the Adaptive Cellular Response to Osmotic Stress in S. cerevisiae., Departamento Química Biológica, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas,UBA, 2022.

- Ojeda LE; Gulias F; Ortola M; Galello FA; Rossi SG; Bermudez Moretti M and Portela, P. Crosstalk between CAMP-PKA and Hog-MAPK Pathways in the Regulation of the Osmotic Stress Response in S. cerevisiae. In Proceedings of the BIOCELL 46 (Suppl. 1); 2022; p. 63.

- Erdman, S.; Snyder, M. A Filamentous Growth Response Mediated by the Yeast Mating Pathway. Genetics 2001, 159, 919–928. [CrossRef]

- Hao, N.; Nayak, S.; Behar, M.; Shanks, R.H.; Nagiec, M.J.; Errede, B.; Hasty, J.; Elston, T.C.; Dohlman, H.G. Regulation of Cell Signaling Dynamics by the Protein Kinase-Scaffold Ste5. Mol Cell 2008, 30, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Sieber, B.; Coronas-Serna, J.M.; Martin, S.G. A Focus on Yeast Mating: From Pheromone Signaling to Cell-Cell Fusion. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2023, 133, 83–95. [CrossRef]

- Van Drogen, F.; Dard, N.; Pelet, S.; Lee, S.S.; Mishra, R.; Srejić, N.; Peter, M. Crosstalk and Spatiotemporal Regulation between Stress-Induced MAP Kinase Pathways and Pheromone Signaling in Budding Yeast. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 1707–1715. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. The Complex Genetic Basis and Multilayered Regulatory Control of Yeast Pseudohyphal Growth. Annu Rev Genet 2021, 55, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.J.; Sprague, G.F. The Regulation of Filamentous Growth in Yeast. Genetics 2012, 190, 23–49. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Heitman, J. Protein Kinase A Operates a Molecular Switch That Governs Yeast Pseudohyphal Differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 3981–3993.

- Robertson, L.S.; Fink, G.R. The Three Yeast A Kinases Have Specific Signaling Functions in Pseudohyphal Growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 13783–13787.

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic Expression Programs in the Response of Yeast Cells to Environmental Changes. Mol Biol Cell 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, J.; Abrams, J.; Wang, Y.; Morano, K.A. Biology of the Heat Shock Response and Protein Chaperones: Budding Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a Model System. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2012, 76, 115–158. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, R.I.; Westerheide, S.D. The Heat Shock Response and the Stress of Misfolded Proteins. Handbook of Cell Signaling, Second Edition 2010, 3, 2231–2239. [CrossRef]

- Keuenhof, K.S.; Berglund, L.L.; Hill, S.M.; Schneider, K.L.; Widlund, P.O.; Nyström, T.; Höög, J.L. Large Organellar Changes Occur during Mild Heat Shock in Yeast. J Cell Sci 2022, 135. [CrossRef]

- Mühlhofer, M.; Berchtold, E.; Stratil, C.G.; Csaba, G.; Kunold, E.; Bach, N.C.; Sieber, S.A.; Haslbeck, M.; Zimmer, R.; Buchner, J. The Heat Shock Response in Yeast Maintains Protein Homeostasis by Chaperoning and Replenishing Proteins. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 4593-4607.e8. [CrossRef]

- Castells-Roca, L.; García-Martínez, J.; Moreno, J.; Herrero, E.; Bellí, G.; Pérez-Ortín, J.E. Heat Shock Response in Yeast Involves Changes in Both Transcription Rates and MRNA Stabilities. PLoS One 2011, 6, e17272. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Renault, G.; Garreau, H.; Jacquet, M. Stress Induces Depletion of Cdc25p and Decreases the CAMP Producing Capability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology (Reading) 2004, 150, 3383–3391. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, P.; Kedersha, N.; Anderson, P. Stress Granules and Processing Bodies in Translational Control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Grousl, T.; Vojtova, J.; Hasek, J.; Vomastek, T. Yeast Stress Granules at a Glance. Yeast 2022, 39, 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, P.; Ham, H.J.; Park, S.; Lee, J.A. Regulation of Cellular Ribonucleoprotein Granules: From Assembly to Degradation via Post-Translational Modification. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.H.; Zhang, B.; Ramachandran, V.; Herman, P.K. Processing Body and Stress Granule Assembly Occur by Independent and Differentially Regulated Pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2013, 193, 109–123. [CrossRef]

- Kozubowski, L.; Aboobakar, E.F.; Cardenas, M.E.; Heitman, J. Calcineurin Colocalizes with P-Bodies and Stress Granules during Thermal Stress in Cryptococcus Neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 2011, 10, 1396–1402. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.F.; Jain, S.; She, M.; Parker, R. Global Analysis of Yeast MRNPs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013, 20, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, V.; Recouvreux, V.; Moreno, S.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Jacquet, M.; Portela, P. Differential Localization to Cytoplasm, Nucleus or P-Bodies of Yeast PKA Subunits under Different Growth Conditions. Eur J Cell Biol 2010, 89, 339–348. [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.Y.; Dyakov, B.J.A.; Zhang, J.; Knight, J.D.R.; Vernon, R.M.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Gingras, A.C. Properties of Stress Granule and P-Body Proteomes. Mol Cell 2019, 76, 286–294.

- Ramachandran, V.; Shah, K.H.; Herman, P.K. The CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway Is a Key Regulator of P Body Foci Formation. Mol Cell 2011, 43, 973–981. [CrossRef]

- Barraza, C.E.; Solari, C.A.; Marcovich, I.; Kershaw, C.; Galello, F.; Rossi, S.; Ashe, M.P.; Portela, P. The Role of PKA in the Translational Response to Heat Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185416. [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, C.; Rossi, S. Transcriptional Regulation of the Protein Kinase A Subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Autoregulatory Role of the Kinase A Activity. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2014, 1839, 275–287. [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, D.; Perlman, R.; Levitzki, A. Transmembrane Signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a Model for Signaling in Metazoans: State of the Art after 25 Years. Cell Signal 2014, 26, 2865–2878. [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Martín, H.; García-Saez, M.I.; Arroyo, J.; Molina, M.; Sánchez, M.; Nombela, C. A Protein Kinase Gene Complements the Lytic Phenotype of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lyt2 Mutants. Mol Microbiol 1991, 5, 2845–2854. [CrossRef]

- Kock, C.; Dufrêne, Y.; Heinisch, J. Up against the Wall: Is Yeast Cell Wall Integrity Ensured by Mechanosensing in Plasma Membrane Microdomains? Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 806–811. [CrossRef]

- Rodicio, R.; Heinisch, J.J. Together We Are Strong - Cell Wall Integrity Sensors in Yeasts. Yeast 2010, 27, 531–540. [CrossRef]

- Verna, J.; Lodder, A.; Lee, K.; Vagts, A.; Ballester, R. A Family of Genes Required for Maintenance of Cell Wall Integrity and for the Stress Response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 13804–13809. [CrossRef]

- Ketela, T.; Green, R.; Bussey, H. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mid2p Is a Potential Cell Wall Stress Sensor and Upstream Activator of the PKC1-MPK1 Cell Integrity Pathway. J Bacteriol 1999, 181, 3330–3340. [CrossRef]

- Zu, T.; Verna, J.; Ballester, R. Mutations in WSC Genes for Putative Stress Receptors Result in Sensitivity to Multiple Stress Conditions and Impairment of Rlm1-Dependent Gene Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2001, 266, 142–155. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.C.; Bardes, E.S.G.; Ohya, Y.; Lew, D.J. A Role for the Pkc1p/Mpk1p Kinase Cascade in the Morphogenesis Checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3, 417–420. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.C.; Zyla, T.R.; Bardes, E.S.G.; Lew, D.J. Stress-Specific Activation Mechanisms for the “Cell Integrity” MAPK Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 2616–2622. [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.A.; Gray, J. V. The Protein Kinase C Pathway Is Required for Viability in Quiescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Current Biology 2002, 12, 588–593. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J.S.; Thiele, D.J. Regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Slt2 Kinase Pathway by the Stress-Inducible Sdp1 Dual Specificity Phosphatase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 21278–21284. [CrossRef]

- Cañonero, L.; Pautasso, C.; Galello, F.; Sigaut, L.; Pietrasanta, L.; Javier, A.; Bermúdez-Moretti, M.; Portela, P.; Rossi, S. Heat Stress Regulates the Expression of TPK1 Gene at Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2022, 1869. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.S.; Causton, H.C.; Young, R.A.; Fink, G.R. The Yeast A Kinases Differentially Regulate Iron Uptake and Respiratory Function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 5984–5988. [CrossRef]

- Chevtzoff, C.; Vallortigara, J.; Avéret, N.; Rigoulet, M.; Devin, A. The Yeast CAMP Protein Kinase Tpk3p Is Involved in the Regulation of Mitochondrial Enzymatic Content during Growth. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2005, 1706, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Palomino, A.; Herrero, P.; Moreno, F. Tpk3 and Snf1 Protein Kinases Regulate Rgt1 Association with Saccharomyces cerevisiae HXK2 Promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, 1427–1438. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Gong, X.; Tong, Y.; Wang, M.; Duan, K.; Zhang, X.; Ge, F.; Yu, X.; Li, S. Phosphorylation of Jhd2 by the Ras-CAMP-PKA(Tpk2) Pathway Regulates Histone Modifications and Autophagy. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Anghileri, P.; Imre, E.; Baroni, M.D.; Ruis, H. Nutritional Control of Nucleocytoplasmic Localization of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic and Regulatory Subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 1449–1456. [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Thevelein, J.M. Molecular Mechanisms Controlling the Localisation of Protein Kinase A. Curr Genet 2002, 41, 199–207. [CrossRef]

- González Bardeci, N.; Caramelo, J.J.; Blumenthal, D.K.; Rinaldi, J.; Rossi, S.; Moreno, S. The PKA Regulatory Subunit from Yeast Forms a Homotetramer: Low-Resolution Structure of the N-Terminal Oligomerization Domain. J Struct Biol 2016, 193. [CrossRef]

- Newlon, M.G.; Roy, M.; Morikis, D.; Carr, D.W.; Westphal, R.; Scott, J.D.; Jennings, P.A. A Novel Mechanism of PKA Anchoring Revealed by Solution Structures of Anchoring Complexes. EMBO J 2001, 20, 1651–1662. [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.G.; Lygren, B.; Dokurno, P.; Hoshi, N.; McConnachie, G.; Taskén, K.; Carlson, C.R.; Scott, J.D.; Barford, D. Molecular Basis of AKAP Specificity for PKA Regulatory Subunits. Mol Cell 2006, 24, 383–395. [CrossRef]

- Sarma, G.N.; Kinderman, F.S.; Kim, C.; von Daake, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, B.-C.; Taylor, S.S. Structure of D-AKAP2:PKA RI Complex: Insights into AKAP Specificity and Selectivity. Structure 2010, 18, 155–166. [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Branduardi, P.; Ballarini, A.; Anghileri, P.; Norbeck, J.; Baroni, M.D.; Ruis, H. Nucleocytoplasmic Distribution of Budding Yeast Protein Kinase A Regulatory Subunit Bcy1 Requires Zds1 and Is Regulated by Yak1-Dependent Phosphorylation of Its Targeting Domain. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21, 511–523. [CrossRef]

- Galello, F.; Moreno, S.; Rossi, S. Interacting Proteins of Protein Kinase A Regulatory Subunit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteomics 2014, 109, 261–275. [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, V.; Recouvreux, V.; Moreno, S.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Jacquet, M.; Portela, P. Differential Localization to Cytoplasm, Nucleus or P-Bodies of Yeast PKA Subunits under Different Growth Conditions. Eur J Cell Biol 2010, 89, 339–348. [CrossRef]

- Barraza, C.E.; Solari, C.A.; Rinaldi, J.; Ojeda, L.; Rossi, S.; Ashe, M.P.; Portela, P. A Prion-like Domain of Tpk2 Catalytic Subunit of Protein Kinase A Modulates P-Body Formation in Response to Stress in Budding Yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868. [CrossRef]

- Barraza, C.E.; Solari, C.A.; Rinaldi, J.; Ojeda, L.; Rossi, S.; Ashe, M.P.; Portela, P. A Prion-like Domain of Tpk2 Catalytic Subunit of Protein Kinase A Modulates P-Body Formation in Response to Stress in Budding Yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868. [CrossRef]

- Rep, M.; Krantz, M.; Thevelein, J.M.; Hohmann, S. The Transcriptional Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Osmotic Shock. Hot1p and Msn2p/Msn4p Are Required for the Induction of Subsets of High Osmolarity Glycerol Pathway-Dependent Genes. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 8290–8300.

- Posas, F.; Chambers, J.R.; Heyman, J.A.; Hoeffler, J.P.; de Nadal, E.; Ariño, J. The Transcriptional Response of Yeast to Saline Stress. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 17249–17255. [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic Expression Programs in the Response of Yeast Cells to Environmental Changes. Mol Biol Cell 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [CrossRef]

- Yale, J.; Bohnert, H.J. Transcript Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae at High Salinity. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 15996–16007. [CrossRef]

- Castells-Roca, L.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Lill, R.; Herrero, E.; Bellí, G. The Oxidative Stress Response in Yeast Cells Involves Changes in the Stability of Aft1 Regulon MRNAs. Mol Microbiol 2011, 81, 232–248. [CrossRef]

- Galello, F.; Pautasso, C.; Reca, S.; Cañonero, L.; Portela, P.; Moreno, S.; Rossi, S. Transcriptional Regulation of the Protein Kinase a Subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during Fermentative Growth. Yeast 2017, 34, 495–508. [CrossRef]

- Reca, S.; Galello, F.; Ojeda, L.; Pautasso, C.; Cañonero, L.; Moreno, S.; Portela, P.; Rossi, S. Chromatin Remodeling and Transcription of the TPK1 Subunit of PKA during Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2020, 1863, 194599. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).