Submitted:

12 June 2023

Posted:

12 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition and delimitation of agroforestry homegardens

2.2. Area of study

2.3. Data collection and analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociocultural use of species in homegardens

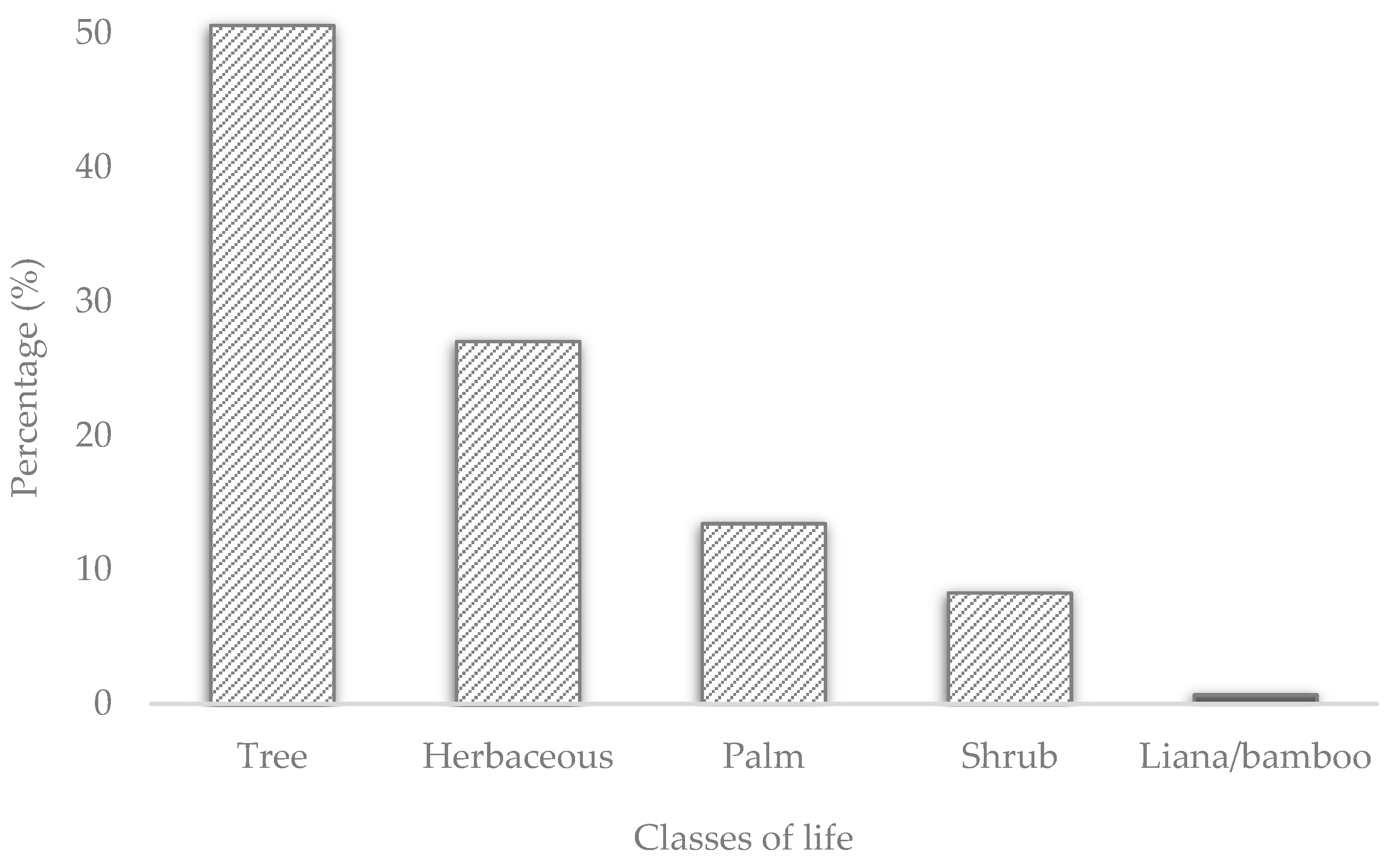

3.2. Form of life and origin of plants

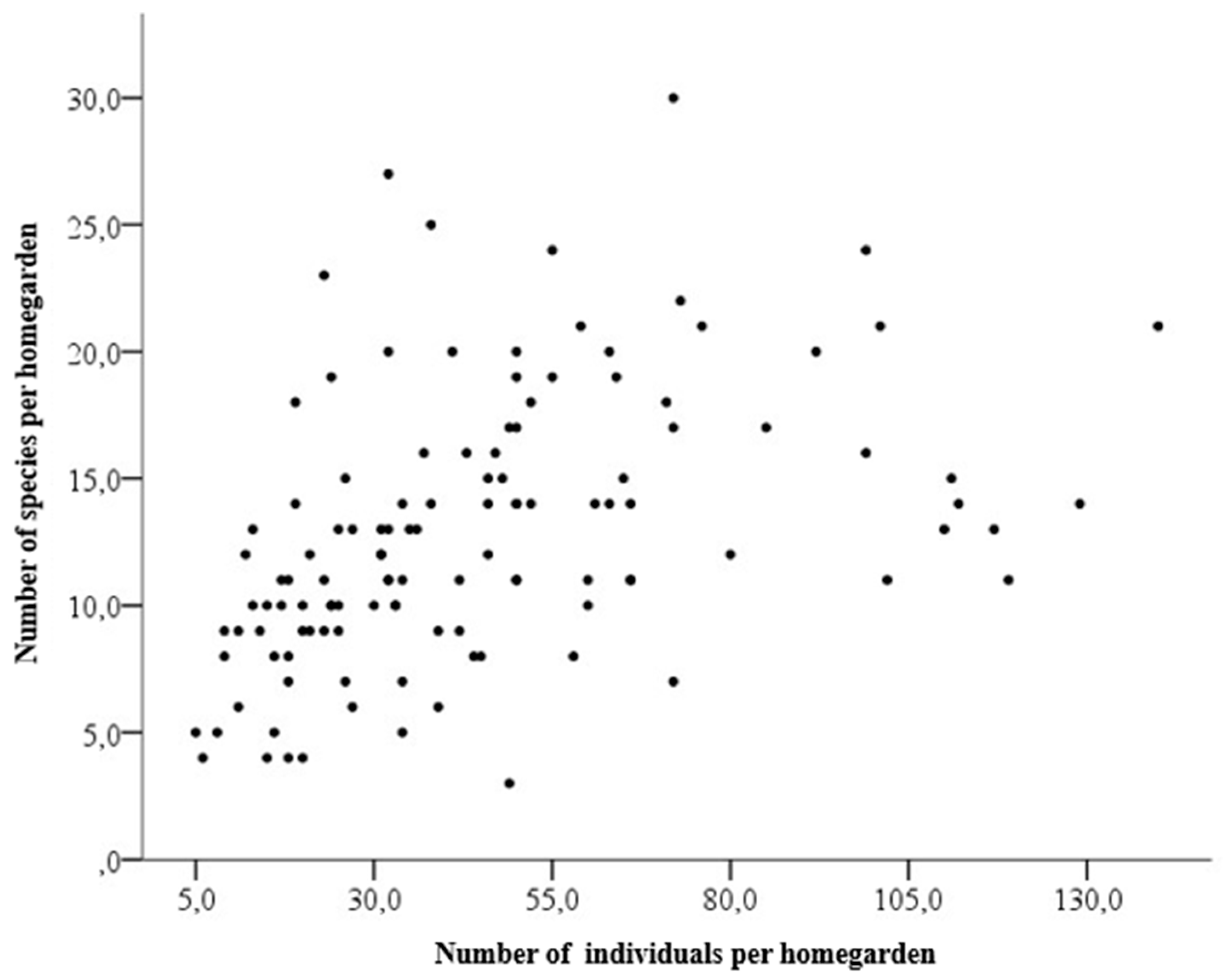

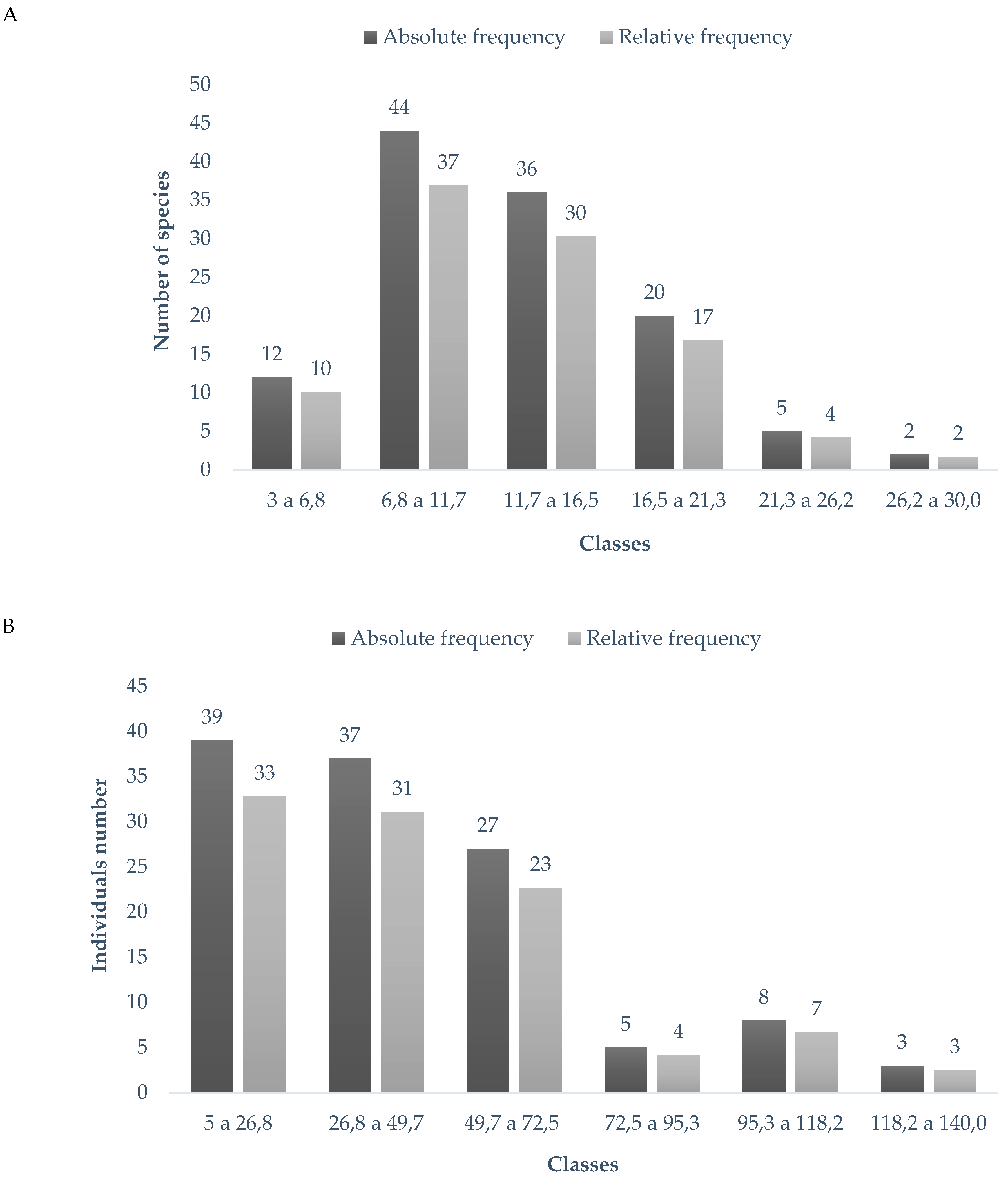

3.3. Characteristics of homegardens in the five zones

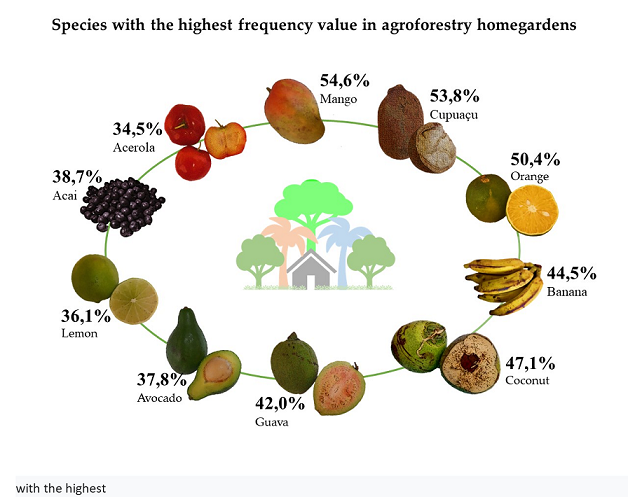

3.4. Featured species in homegardens

3.5. Importance and perspectives for agroforestry homegardens

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

| 1 | To facilitate the reading of the text, the name "homegardens" was considered the summarized form of " agroforestry homegardens". |

References

- Nair, P.K.R.; Kumar, B.M.; Nair, V.D. An introduction to agroforestry: four decades of scientific developments; Springer: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, L.S.; Gama, J.R.V. Quintais agroflorestais: estrutura, composição florística e aspectos socioambientais em área de assentamento rural na Amazônia brasileira. Ciência Florestal 2014, 24, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.G.; Altieri, M.A. Sistema agroflorestais. In Agroecologia: bases cientifica para uma agricultura sustentável. 3. Ed.Ver. Ampl; Altieri, M.A., Ed.; Expressão popular, AS-PTA: São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, W.A.M.; Silva, G.L.L.P.; Pushpakumara, D.K.N.G. Homegardens as a modern carbon storage: Assessment of tree diversity and above-ground biomass of homegardens in Matale district, Sri Lanka. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 74, 127671. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, C.; et al. Agroforestry contributions to smallholder farmer food security in Indonesia. Agroforestry Systems 2021, 95, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.N.; Maneschy, R.Q.; Oliveira, P.D.; De Souza Oliveira, I.K. Caracterização de quintais agroflorestais no projeto de assentamento Belo Horizonte I, São Domingos do Araguaia, Pará. Revista Agroecossistemas 2013, 2, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.W.S.; Vieira, T.A. Plant diversity of tree and shrub strata of agroforestry homegardens in an agro-extractive settlement, Monte Alegre, Pará. Ciência e Natura 2021, 43, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayol, B.P.; Miranda, I.S. Quintais agroflorestais na Amazônia Central: caracterização, importância social e agrobiodiversidade. Ciência Florestal 2019, 29, 1614–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, T.A.; Rosa, L.S.; Santos, M.M.L.S. Condições socioeconômicas para o manejo de quintais agroflorestais em Bonito, Pará. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias 2013, 8, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, E.; Ostwald, M.; Nissanka, S.P. What is good about Sri Lankan homegardens with regards to food security? A synthesis of the current scientific knowledge of a multifunctional land-use system. Agroforestry Systems 2018, 92, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwardi, A.B.; Navia, Z.I.; Mubarak, A.; Mardudi, M. Diversity of home garden plants and their contribution to promoting sustainable livelihoods for local communities living near Serbajadi protected forest in Aceh Timur region, Indonesia. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, R.N.; Moreira, L.L.; Vieira, C.R. Diversidade de plantas alimentares em quintais agroflorestais de Cuiabá e Várzea Grande, Mato Grosso, Brasil. Interações 2021, 22, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayol, B.P.; Do Vale, I.; Miranda, I.S. Tree and palm diversity in homegardens in the Central Amazon. Agroforestry systems 2019, 93, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.R.; Malek, S.; Milow, P. Diversity, structure, and application of self-organizing map on plant species in homegardens. Tropical Ecology 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinebeb, M.; et al. Homegardens plant species richness and their use types have positive associations across agricultural landscapes of Northwest Ethiopia. Global Ecology and Conservation 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.C. Sistemas Agroflorestais: conceitos e métodos; SBSAF: Itabuna, 2013. I: Agroflorestais: conceitos e métodos; SBSAF.

- de Vasconcellos, R.C.; Beltrão, N.E.S. Avaliação de prestação de serviços ecossistêmicos em sistemas agroflorestais através de indicadores ambientais. Interações (Campo Grande) 2018, 19, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A.P.S.; et al. Meliponicultura em sistemas agroflorestais em Belterra, Pará. ACTA Apicola Brasilica 2021, 9, e7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.S. Quintais agroflorestais e estado nutricional familiar na comunidade Santa Maria, Santarém-PA. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, 2015.

- Getachew, E.; Lemessa, D.; Leulekal, E. Socio-ecological determinants of species composition of crops in homegardens of southern Ethiopia. Agroforestry Systems 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Filho, J.R.; Costa Moraes, L.L.; Luz Freitas, J.D.; Cruz Junior, F.O.; Santos, A.C. Quintais agroflorestais em uma comunidade rural no vale do Rio Araguari, Amazônia Oriental. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais 2021, 12, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.G.F.; Anjos, M.C.R.; Anjos, A. Quintais produtivos: para além do acesso à alimentação saudável, um espaço de resgate do ser. Guaju 2016, 2, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashima, Y.; Andrade, M.L.; Gandara, F.B.; Tomas, F.L. Sistemas agroflorestais em áreas urbanas. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Arborização Urbana 2009, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervazio, W. Agrobiodiversidade e qualidade do solo em quintais agroflorestais urbanos na cidade de Alta Floresta–MT. 2015.136 f (Doctoral dissertation, Dissertação) –Programa de Pós-graduação em Biodiversidade e Agroecossistemas Amazônicos, Faculdade de Ciências Biológicas e Agrárias da Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso), 2015.

- Vieira, T.A.; Rosa, L.S.; Santos, M.M.L.S. Agrobiodiversidade de quintais agroflorestais no município de Bonito, Estado do Pará. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2012, 55, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; et al. The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature 2018, 559, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Mina, U.; Kumar, B.M. Homegarden agroforestry systems in achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2022, 42, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, M.G.R.; Carmuça, A.M.; Esmeraldo, G.G.S.L.; Sousa, N.R. Quintais produtivos: contribuição à segurança alimentar e ao desenvolvimento sustentável local na perspectiva da agricultura familiar (o caso do Assentamento Alegre, no município de Quixeramobim/CE). Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia 2013, 8, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – Ibge. Classificação e caracterização dos espaços rurais e urbanos do Brasil: uma primeira aproximação. Rio de Janeiro, 2017. 2017.

- Veiga, J.E. Nem tudo é urbano. Ciência e cultura 2004, 56, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alvares, C.A.; et al. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorano, L.G.; Nechet, D.; Pereira, L.C. Tipologia climática do Estado do Pará: adaptação do método de Köppen. Boletim de Geografia Teorética 1993, 23, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Martorano, L.G.; et al. Climatology of Air Temperature in Belterra: Thermal Regulation Ecosystem Services Provided by the Tapajós National Forest in the Amazon. Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 2021, 36, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Júnior, R.C.; Corrêa, J.R.V. Caracterização dos solos do município de Belterra, Estado do Pará. Embrapa Amazônia Oriental 2001, 88, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, T.E.; Santos, P.L.; Oliveira Júnior, R.C.; Valente, M.A.; Silva, J.M.L.; Cardoso Júnior, E.Q. Caracterização dos solos da área do Planalto de Belterra, município de Santarém, estado do Pará. Embrapa Amazônia Oriental 2001, 15, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira Neto, H.G.; Pereira, C.A.; Almeida, E.N. Dinâmica Da Produção De Alimentos Na Região De Santarém, Oeste Do Pará. Terceira Margem Amazônia 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2005.

- Flora e Funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available online: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ Acesso em: 30 ago. 2022. 3: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ Acesso em, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V. et al. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobiológica e etnoecológica. Recife, Brazil: NUPEEA, p. 189–206, 2010.

- Ayres, M. et al. Aplicações estatísticas nas áreas das ciências bio-médicas. Instituto Mamirauá, Belém, v. 364, 2007. Available online: https://www.mamiraua.org.br/downloads/programas/. Acesso em 02 maio 2022.

- Carvalho, T.K.N.; et al. Structure and floristics of home gardens in an altitudinal marsh in northeastern Brazil. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 2013, 11, 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Quaresma, A.P.; Almeida, R.H.C.; Oliveira, C.M.; Kato, O.R. Composição florística e faunística de quintais agroflorestais da agricultura familiar no nordeste paraense. Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável 2015, 10, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Álvarez, N.P.; et al. Global conservation priorities for crop wild relatives. Nature plants 2016, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, R.; Su, Q.; Tamang, E. The pareto principle. 2014.

- Newman, M.E. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf's law. Contemporary physics 2005, 46, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winklerprins, A.; Oliveira, P.S.S. Agricultura urbana em Santarém, Pará, Brasil: diversidade e circulação de plantas cultivadas em quintais urbanos. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 2010, 5, 571–585. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, B.N.R.; Vieira, T.A.; Oliveira, F.A. Tree and shrub diversity in agroforestry homegardens in rural community in Eastern Amazon. Floresta 2017, 47, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; et al. Diversidade e multifuncionalidade de quintais agroflorestais em aldeias da Terra Indígena Tupinambá, Santarém, Pará. Biodiversidade 2022, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Pauletto, D.; et al. Caracterização de quintais agroflorestais da Várzea: estudo de caso na comunidade Alto Jari em Santarém–Pará. Cadernos de Agroecologia 2020, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, J.A.; Junqueira, A.B.; Clement, C.R. Homegardens on Amazonian dark earths, non-anthropogenic upland, and floodplain soils along the Brazilian middle Madeira River exhibit diverging agrobiodiversity. Economic Botany 2011, 65, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.H. Tabelas para classificação do coeficiente de variação (Vol. 171). IPEF, 1989. 11 p.

- Garcia, B.N.R.; Vieira, T.A.; Oliveira, F.A. Aspectos socioeconômicos de manejadores de quintais agroflorestais: o caso de uma comunidade rural na Amazônia. Revista Contribuciones a las Ciencias Sociales 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson, E.; Ostwald, M.; Nissanka, S.P. What is good about Sri Lankan homegardens with regards to food security? A synthesis of the current scientific knowledge of a multifunctional land-use system. Agroforestry Systems 2018, 92, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, L.D. S et al. Desafios para a Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional na Amazônia: disponibilidade e consumo em domicílios com adolescentes. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2018, 23, 4043–4054. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, R. et al. Está na mesa: receitas com pitadas literárias. Papirus Editora, 2005.

- Zuin, L.F.S.; Zuin, P.B. Alimentação é cultura: aspectos históricos e culturais que envolvem a alimentação e o ato de se alimentar:[revisão]. Nutrire Rev. Soc. Bras. Aliment. Nutr 2009, 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Santilli, J. Agrobiodiversidade e direitos dos agricultores. Editora Peirópolis LTDA, 2009.

- Levis, C.; et al. Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian Forest composition. Science 2017, 355, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fao - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Training building on gender, agrobiodiversity and local knowledge. 2005. Training building on gender, 2005.

- Paterniani, E. Agricultura sustentável nos trópicos. Estudos avançados 2001, 15, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombi, L. et al. Climate-smart agriculture: sourcebook. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2013. 2013.

- Tuler, A.C.; Peixoto, A.L.; Silva, N.C.B. da. Plantas alimentícias não convencionais (PANC) na comunidade rural de São José da Figueira, Durandé, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rodriguésia 2019, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Extração Vegetal e da Silvicultura (PEVS). 2020a.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017–2018: análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. 2020b.

- Sistema de Vigilância Alimentar e Nutricional (Sisvan). Relatórios de Acesso Público. Ministério da Saúde. Available online: https://sisaps.saude.gov.br/sisvan/relatoriopublico/index. Acesso em: 31 ago. 2022. 3: Saúde. Available online: https://sisaps.saude.gov.br/sisvan/relatoriopublico/index. Acesso em, 2022.

- Maluf, R.S. Segurança Alimentar e nutricional. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2007. 176 p.

- FAO, FIDA, OPS, WFP y UNICEF. 2021. América Latina y el Caribe - Panorama regional de la seguridad alimentaria y nutricional 2021: estadísticas y tendencias. Santiago de Chile, FAO. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Lei nº 11.326, de 24 de julho de 2006. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, ano 2009, n. 128, p. 1–72, 8 jul. 2009. Estabelece as diretrizes para a formulação da Política Nacional da Agricultura Familiar e Empreendimentos Familiares Rurais. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11326.htm. /.

- Florentino, A.T.N.; Araújo, E.L.; Albuquerque, U.P. Contribuição de quintais agroflorestais na conservação de plantas da Caatinga, Município de Caruaru, PE, Brasil. Acta botanica brasilica 2007, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siviero, A.; Lin, C.M.; Silveira, M.; Daly, D.C.; Wallace, R.H. Etnobotânica e botânica econômica do Acre. Edufac, 2016.

- Moura, E.A.F. Moura, E.A.F. et al. Sociodemografia da reserva de desenvolvimento sustentável Mamirauá. 2016.

- Nunes, J.G.S.; et al. População Ribeirinha e Promoção da Saúde. Revista Científica da Faculdade de Educação e Meio Ambiente 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Palheta, I.C. Quintais urbanos e plantas medicinais: um estudo etnobotânico no bairro São Sebastião, Abaetetuba-PA. 2015. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade do Estado de Pará.

- Lobato, G.J.M.; Martorano, L.G.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Tavares-Martins, A.C.C.; Jardim, M.A.G. Condições Térmico-Hídricas E Percepções de Conforto Ambiental em Quintais Urbanos de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Revista Ra & Ga Espaço Geográfico em Análise 2016, 38, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Alves, E.; Rayol, B. Diversidade das Espécies Arbóreas em Quintais de Várzea da Ilha Saracá, Limoeiro do Ajuru, Pará. Espaço Aberto 2021, 11, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.R.V.; Souza, A.L.; Martins, S.V.; Souza, D.R. Comparação entre florestas de várzea e de terra firme do Estado do Pará. Rev. Árvore 2005, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudel, E. et al. Consolidando a Agricultura Familiar: Cartilhas do Observatório das Dinâmicas Socioambientais. [S. l.], 2019.

- Biassio, A. Agrobiodiversidade em escala familiar nos municípios de Antonina e Morretes (PR): Base para sustentabilidade socioeconômica e ambiental. 2011. Tese de Doutorado. Dissertação de Mestrado) - Curso de Curso de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Florestal, Setor de Ciências Agrárias, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba.

- Pereira, A.G.; Alcantara, L.C.S.; De Oliveira, R.E.; Sais, A.C. Plantas com potencial medicinal em quintais agroflorestais: diversidade entre comunidades rurais do Portal da Amazônia-Mato Grosso, Brasil. Research, Society and Development 2021, 10, e59010615713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.M.B. Aspectos da segurança alimentar com base em quintais agroflorestais na comunidade rural de Santa Luzia do Induá no município de Capitão Poço, PA. Revista Agroecossistemas 2018, 9, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.G.D.; Borges, C.D.; Miguel, A.C.A.; Jacomino, A.P.; Mendonça, C.R.B. Características físico-químicas de cebolinhas comum e europeia. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology 2015, 18, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censo Agropecuário 2017. Online. Cupuaçu. Pará. Available online: https://censoagro2017.ibge.gov.br/templates/censo_agro/resultadosagro/agricultura.html?localidade=15&tema=78248>. Acesso em 19 Jan. 2023.

- Matos Rebêlo, A.G.; et al. Quintais agroflorestais urbanos em Belterra, PA: importância ecológica e econômica. Terceira Margem Amazônia 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Perola do Maicá (APM). Rede social Facebook. Acesso em ago/2022.

- Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (OPAS). Sistemas alimentares e nutrição: a experiência brasileira para enfrentar todas as formas de má nutrição. Brasília, DF, 2017.

- Sousa, W.L.; Santos, A.O.; Serrão, E.M.; Gama, A.S.P.; Vieira, T.A. Quintais agroflorestais e trabalho da mulher em espaço periurbano: um estudo de caso em Santarém, Pará, Brasil. Research, Society and Development 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepal, N.U. et al. Fomento de circuitos cortos como alternativa para la promoción de la agricultura familiar. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación-FAO, Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura, 2014.

- Goodman, D. Espaço e lugar nas redes alimentares alternativas: conectando produção e consumo. Cadeias curtas e redes agroalimentares alternativas–negócios e mercados da agricultura familiar 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Souza Amaral, L.; Santos, C.J.; Souza, C.R.; Penha, T.A.M.; Araújo, J.P. O papel das Cadeias Curtas de Comercialização na construção de um modelo de desenvolvimento rural sustentável no semiárido nordestino: o caso da Central de Comercialização da Agricultura Familiar do Rio Grande do Norte (CECAFES). Desenvolvimento e meio ambiente, v. 55, 2020. Desenvolvimento e meio ambiente.

- Câmara Municipal de Santarém (CMS). Pará. Interlegis. Sistema de Apoio ao Processo Legislativo. Lei nº 17.894, de 15 de dezembro de 2004. Available online: https://sapl.santarem.pa.leg.br/ Acesso em ago/2022.

- Lima, A.C.; et al. Registros de incêndios na região metropolitana de Santarém/PA no período de 2012 a 2016. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais 2020, 11, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.M.; Nogueira, C.M. Pagamentos por Serviços Ambientais: uma abordagem conceitual, regulatória e os limites de sua expansão no Brasil. Extensão Rural 2021, 28, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Zone | Amplitude (min. and max.) | Average* | Standard deviation | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of species | Peri-urban | 4 a 30 | 13,9a | ± 5,5 | 40,8 |

| Urban | 4 a 30 | 11,9a | ± 5,1 | 42,6 | |

| Floodplain | 4 a 16 | 10,5a | ± 3,7 | 34,7 | |

| Indigenous | 4 a 24 | 14,5a | ± 5,3 | 36,8 | |

| Tourist | 6 a 27 | 13,5a | ± 6,8 | 50,3 | |

| Number of individual plants | Peri-urban | 5 a 167 | 33,8B | ± 23,0 | 68,2 |

| Urban | 5 a 99 | 42,5AB | ± 22,4 | 52,8 | |

| Floodplain | 8 a 119 | 58,2AC | ± 32,7 | 56,1 | |

| Indigenous | 6 a 140 | 62,5A | ± 37,1 | 59,4 | |

| Tourist | 11 a 55 | 30,9BC | ± 12,2 | 39,5 |

| Order | Popular name | Scientific name | Frequency (%) | Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mango* | Mangifera indica L. | 54,6 | 3,3 |

| 2 | Cupuaçu* | Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. ex Sprng) | 53,8 | 7,8 |

| 3 | Orange* | Citrus sp. | 50,4 | 4,8 |

| 4 | Coconut* | Cocos nucifera L. | 47,1 | 3,6 |

| 5 | Banana* | Heavenly Muse L. | 44,5 | 6,6 |

| 6 | Guava | Psidium sp. | 42,0 | 2,4 |

| 7 | Acai* | Euterpe oleracea Mart. | 38,7 | 5,8 |

| 8 | Avocado | Persea sp | 37,8 | 1,5 |

| 9 | Lemon* | Citrus latifolia | 36,1 | 1,7 |

| 10 | Acerola | Malpighia emarginata L. | 34,5 | 1,3 |

| 11 | Cashew* | Anacardium occidentale sp. | 33,6 | 1,9 |

| 12 | Murici* | Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) | 32,8 | 4,6 |

| 13 | Pupunha* | Bactris gasipaes Kunth. | 31,9 | 3,2 |

| 14 | Papaya* | Load sp. | 27,7 | 1,6 |

| 15 | Jambo | Eugenia malaccensis L. | 23,5 | 0,8 |

| 16 | Tangerine* | Citrus nobilis Lour. | 23,5 | 1,7 |

| 17 | Bacaba | Oenocarpus bacaba Mart. | 19,3 | 0,8 |

| 18 | Chives* | Allium schoenoprasum L. | 19,3 | 5,4 |

| 19 | Soursop | Annona muricata L. | 18,5 | 0,6 |

| 20 | Ata | Annona squamosa L. | 17,6 | 1,0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).