1. Introduction

The quality of people's lives depends on their lifestyle, the environment they live in (e.g with high pollution), the food they eat, and the drugs they take. Added to these are the interaction of food with drugs or food supplements, and their adverse reactions. Regardless of the type of pollution (e.g. air, water, soil, sonic or olfactory), it negatively influences people's health at different levels. According to the research program called "Teplice Program", carried out in the Czech Republic [

1], polluted air can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, negative impact on sperm morphology, learning difficulties in children, or respiratory morbidity in preschool children. Soil pollution with heavy metals from pesticides and plastic microparticles leads to flora and fauna contamination and human diseases, including cardiovascular conditions [

2]. Soil pollution, accompanied by its erosion, due to the cutting of forests, leads to water pollution with harmful effects on health [

2,

3]. Many drugs can cause side effects or reactions and can interact with other medicines, or foods. Authors Mogoșan CI et al. [

4] defined an adverse event as any unexpected and unwanted medical incident that may be present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product, but which is not necessarily causally related to that product. They all define an adverse reaction as an unintended and harmful response to a drug that occurs at doses normally used in humans for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or treatment of a condition or for the modification of a physiological function. According to Zazzara M.B. et al [

5], adverse drug reactions are a common cause of unplanned hospitalization, increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs and implicitly increasing health system costs, and the need to allocate a higher percentage of the gross domestic profit of all countries. For the detection, evaluation, understanding, and prevention of adverse drug reactions or other drug-related problems, the pharmacovigilance system was established. It is working in all developed countries.

In Romania, the pharmacovigilance system belongs to the National Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices, within the Ministry of Health. The pharmacovigilance system allows spontaneous reporting of adverse reactions and monitoring of drug safety. Factors that contribute to the occurrence of adverse drug reactions are pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors, associated comorbidities, special physiological conditions, drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, lifestyle, genetic variability, adherence to treatment, and even medication errors [

4].

Allergy is recognized as an adverse reaction to common foods, milk, and products derived from it, including lactoferrin, seafood, fish, peanuts, nuts, eggs, wheat, soy, seeds of sesame and edible insects, newly authorized by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Commission (EC). In addition to this adverse reaction, plant food resources can also cause liver dysfunction in cancer patients - Agaricus blazei Murrill [

6], cheilitis - Agaricus blazei Murrill [

7], liver damage - Aloe vera [

8], acute hepatitis - Aloe vera [

9], hypokalemia - following the use of aloe vera during chemotherapy - Aloe vera [

10], toxic hepatitis - Aloe vera [

11] or neurotoxicity - Asimina triloba [

12].

The previously mentioned food resources have contraindications, such as Agaricus blazei Murrill in the case of patients with hormone-sensitive cancers (estrogen) [

13] and pregnant women should avoid the consumption of Aloe vera [

14], and it interacts with medications: in vitro, Agaricus blazei Murrill inhibits CYP3A4 [

15] and may affect the intracellular concentration of drugs metabolized by this enzyme.

The assumption that food resources and dietary supplements are natural and do not have side effects, or do not interact with drugs is wrong and can lead to unplanned symptoms or even hospital admissions. Also, failure to communicate with the general practitioner, the specialist doctor, or the pharmacist, can make their work considerably more difficult in establishing the correct treatment.

Since 2009, France, through the National Food and Animal Safety Authority (ANSES), monitors food supplements containing spirulina, melatonin, red rice yeast and p-synephrine, supplements for pregnant women and athletes, and energy drinks. They are monitored after sales. France was joined by Italy, Belgium, Greece, the Czech Republic, Ireland, and Slovenia for the regulation and implementation of nutrivigilance. In Italy, natural products, herbal products, traditional Chinese or Ayurvedic medicine preparations, food supplements, vitamins and probiotics and homeopathic medicines, medicinal preparations, or galenic masters are monitored.

In Belgium, the nutrivigilance system is a quality system used by the company responsible for marketing food supplements to fulfill the tasks and responsibilities required by the competent authorities and designed to monitor the safety of authorized food supplements and detect any change in the risk-benefit ratio of them. The quality system is part of the nutrivigilance system and consists of its own structures and processes. It covers the organizational structure, responsibilities, procedures, processes, and resources of the nutrivigilance system, as well as appropriate resource management, compliance management, and records management. In this country, the raw materials used in nutraceuticals, and recent scientific publications in the context of combinations of materials are monitored premiums and monitoring of new nutraceuticals worldwide. In all European Union (EU) countries where nutrivigilance is implemented, reporting of adverse reactions can be done by health professionals, such as doctors, pharmacists, midwives, masseurs, physiotherapists and dieticians, manufacturers or distributors, who observe or they become aware of the adverse effects associated with the consumption of these foods and people (consumers). Reporting adverse reactions is easy to do and can be done online.

Although Romanian clinicians encounter patients with adverse reactions to medicinal plants, because currently in Romania nutrivigilance is not implemented legislatively, they cannot report adverse reactions, and thus, food and dietary supplements cannot be monitored post-sale. Because of this, inpatient cases and costs to the healthcare system are increasing.

As food safety falls to the food operator [

16], we propose that non-vigilance also falls to it and to operators from the field of food supplements. It is necessary that nutrivigilance be ensured along the entire food chain, starting with processing resources of animal or plant origin and continuing with consumption by patients and/or consumers.

Although on an international level nutrivigilance is applied post-sale, like pharmacovigilance, in this research we aimed to show the method by which nutrivigilance can be implemented and applied in the stage of research-development of food and food supplements.

2. Materials and Methods

PubMed, ResearchGate, EUR-Lex and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center databases were analyzed. Given that currently, with the exception of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center database, there is no centralized information on side effects, contraindications, and interactions with drugs, for this work we considered expanding the analysis period between 2000-2023. The extension of the period from the last five years (2018 - 2023) was also carried out from the perspective of implementing nutrivigilence in the research-development (pre-sale) stage, compared to the current monitoring, which is carried out post-sale. The following expressions were used: "adverse reactions", nutrivigilance", "drug interaction", and the scientific names of food resources in Latin.

The method proposed by us for the implementation of nutrivigilance in the research-development stage is applying and adapting HACCP principles (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) to nutrivigilance, based on the 7 principles [

16]:

P1: Identification of any risks that must be prevented, eliminated, or reduced to an acceptable level;

P2: Identification of critical control points in the stage or stages in which control is essential to prevent the risk or to reduce it to an acceptable level;

P3: Establishing critical limits at critical control points capable of separating the acceptable from the unacceptable domain from the point of view of preventing, eliminating, or reducing the identified risks;

P4: Establishing and implementing effective monitoring procedures at critical control points;

P5: Establishing corrective measures for cases where a critical control point is not controlled;

P6: Establishing procedures that are applied periodically to verify the effective functioning of the measures mentioned in principles P1 - P5;

P7: Definition of documents and records depending on the nature and size of the enterprise in the food sector to demonstrate the effective application of the measures mentioned in principles 1-6.

3. Results

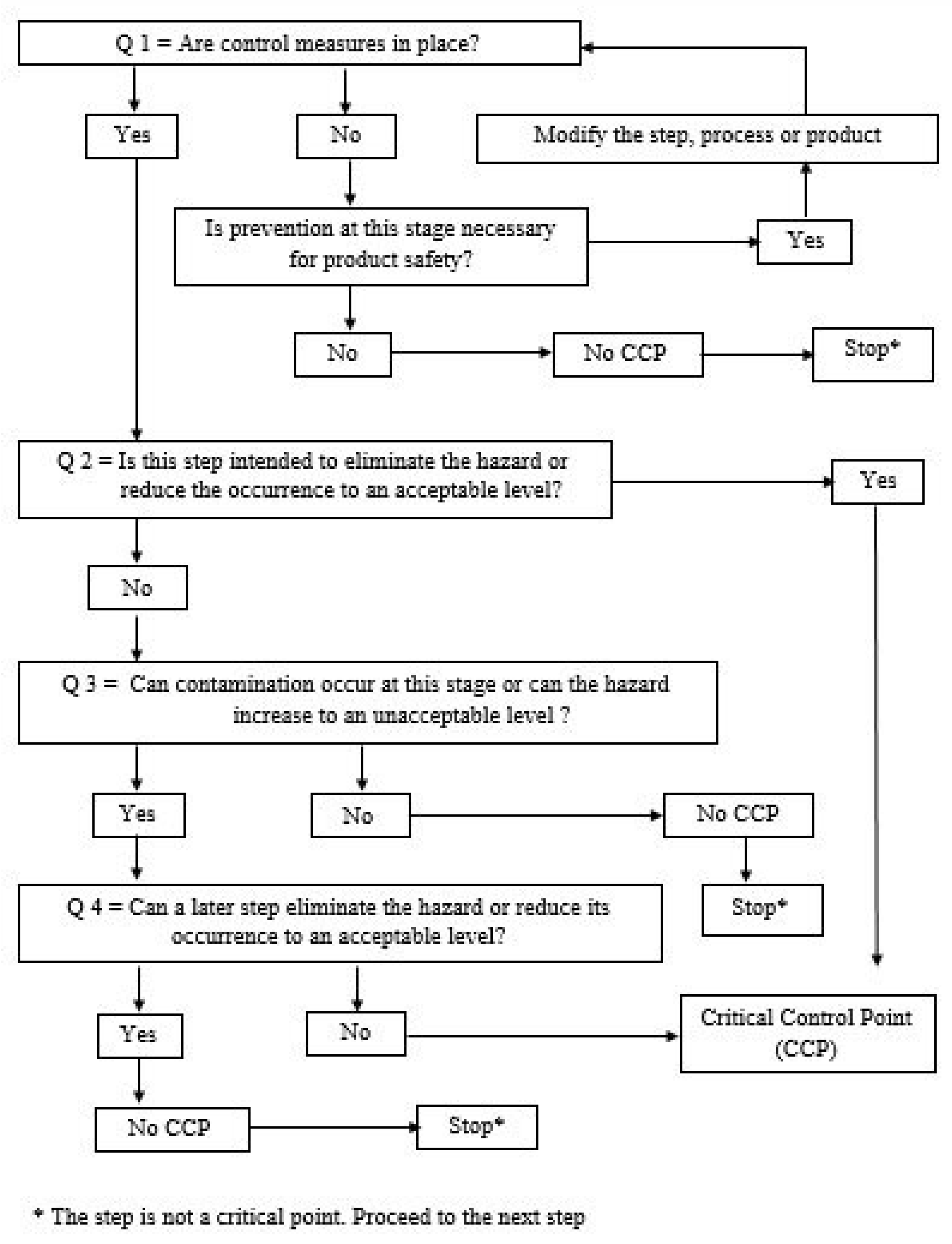

For the application of HACCP principles in nutrivigilance, we propose the abbreviation HACCPn, where "n" comes from nutrivigilance. To establish control points (CP) and critical control points (CCP), the Decision Tree is used. A critical control point (CCP) is that point (or step) at which a control measure must be applied. It is a critical or critical point for safety. This is the point at which a control measure can be used to prevent or eliminate a food safety hazard or to reduce it to an acceptable level. If we consider the safety of the lives of patients who have certain administration treatments, or of healthy people who take food supplements under the influence of the media or unauthorized platforms, we can very easily adapt the definition of a CCP, like this: "A point critical control in nutrivigilance (CCPn) is that point (or step) at which a measure must be applied to monitor recent scientific publications for raw materials and ingredients in the context of reactions or adverse effects caused and recent scientific publications for raw materials and ingredients used and which interacted with oral or parenteral drugs, or which caused adverse reactions. It is a critical or essential point for patient safety. It is about the point at which a control measure can be used to prevent or eliminate a patient safety hazard or to reduce it to an acceptable level".

To exemplify the application of the 7 principles of HACCPn, we will consider Aloe vera The HACCPn principles adapted to nutrivigilance are presented below:

Principle 1: Conduct an analysis of potential risks in terms of adverse reactions, contraindications, and drug interactions. We propose to register them in the preliminary list of dangers from the point of view of nutrivigilance (

Table 1).

We recommend that all adverse reactions, possible contraindications and drug interactions identified, both in vitro, preclinical and clinical studies, for all ingredients of the analyzed food (e.g. ice cream) be reported. Since plant resources can present several species, and plant ingredients can be of various types, such as fresh, dry, powder, leaves, alcoholic or aqueous extract, or obtained by certain methods [

22], we propose that all possible adverse reactions be mentioned, for the following reasons:

- if the methods of obtaining a certain ingredient (e.g. Aloe vera powder) are not known, in the event of an adverse reaction or an interaction with drugs, traceability from the point of view of nutrivigilance can be quickly achieved;

- the respective ingredient (e.g. Aloe vera powder) can react with water (e.g. Aloe vera sorbet ice cream, or Aloe vera juice).

This recommendation is also valid for ingredients purchased from the electronic market when only the site administrator is known.

Until the maturation of the nutrivigilance system, we recommend keeping (in the physical or electronic file) the scientific references included in the analysis of dangers from the point of view of nutrivigilance.

Unlike food safety systems, where the dangers can be physical, chemical and biological, in nutrivigilance, they can be: adverse reactions (pathologies), contraindications, and interactions with enzymes that metabolize drugs, such as cytochrome P450.

Principle 2: Determination of non-vigilance critical control points (CCPn) (

Table 12 and

Table 13). The information in the table is provided as an example of an Aloe vera diet.

This table is completed for all ingredients of the food being analyzed.

We gave an example.

To see whether a hazard is a Nutrivigilance Control Point (CPn) or a Nutrivigilance Critical Control Point (CCPn) apply the Food Safety Decision Tree in

Figure 4.

To motivate the answers to the four questions and respectively the establishment of CPn or CCPn,

Table 4 will be completed.

For the monitoring of the CCPn production flow, they can be numbered as follows: CCPn 1 AR (adverse reaction), CCPn 2 C (contraindications), CCPn 3 IM (drug interaction). This notation can be used in documents related to nutrivigilance.

Principle 3: Establish critical limits.

Critical limits for CCPn can be recorded in

Table 15. This table is a proposal and is completed by each HACCPn team.

Principle 4 - Establishing a monitoring system in CCPn.

In the case of nutrivigilance, respectively of adverse reactions of type A, C, D and F, the monitoring system in CCPn can be represented by the manufacturing recipe of the respective food in terms of ingredients and working method. Given that raw materials and ingredients may present cross-contamination from their suppliers, it is essential that the monitoring system in the CCP also has records of raw material/ingredient name, supplier name, batch/batch, and expiry date. This information is essential to achieve traceability, in the event that unpredictable adverse reactions occur at the post-sale stage.

Principle 5 – Establish corrective actions for situations where monitoring indicates that a CCP is not under control.

Unlike food safety, where a critical control point (CCP) can be monitored during the manufacturing process (e.g. temperature), and corrective actions (e.g. decreasing or increasing temperature) can be applied, in the case of nutrivigilance CCPn 1 AR (adverse reaction), CCPn 2 C (contraindications), CCPn 3 IM (drug interaction) can be established in the post-sale stage.

Principle 6 – Establish verification processes to confirm that the HACCPn system (HACCP in the field of nutrivigilance) is working effectively. These procedures will be carried out both by economic agents in the food industry, that food supplements, and by the "Authority".

Principle 7 - Establishing a system of specific documents for all procedures and records in accordance with the previous principles and their application in practice. These will be of the type of work procedures and instructions.

4. Discussion

For the good management of the possible adverse reactions caused by the analyzed food from the point of view of nutrivigilance, we recommend the analysis and classification of the adverse reactions recorded for the analysis and implementation of the 7 HACCP principles, according to the following criteria: frequency, severity, latency and duration, the mechanism underlying their occurrence (classification proposed by Rawlins and Thomson), predictability, dose, time, susceptibility (DoTS classification) [

4]. This information can be obtained from the scientific articles that represent the previously mentioned references.

In the field of food safety, the target value and the lower and upper critical limits for a CCP are established. Considering the characteristics and management of side effects according to the modified Rawlins and Thompson classification [

4], we consider that in the case of nutrivigilance, respectively side effects of type A, C, D, and F, a correlation should be made between the dose identified in the scientific references considered for the ingredients and the quantity contained in the analyzed food. Considering that there is the possibility that an individual consumes a larger amount of a certain food, and the average amount consumed by an adult in 24 hours, can represent an input element in the analysis.

Due to the unpredictable adverse reactions occurring in the post-sale stage, the monitoring procedure in the CCP must provide that the person responsible for nutrivigilance at the economic agent in the food industry, and that of food supplements, report these adverse reactions. Unpredictable adverse reactions are type B and have an immunological or idiosyncratic mechanism and are not dose-dependent. For this reason, it is essential that the nutrivigilance system is legislated in all countries.

If the nutrivigilance system is not implemented nationally, the person responsible for nutrivigilance together with healthcare professionals (doctors/pharmacists) can publish a case report. For this, post-sale information is also required, such as the gender and age of the person who reported the adverse reaction, the family doctor, or the pharmacist or economic agent in the food industry, the amount of food consumed, the period, if in the period was under treatment and other information as appropriate. This means that the economic agent in the food industry must create the possibility of receiving adverse reactions by telephone or electronically, and manage the respective information, throughout the period that they manufacture those foods for which adverse reactions have been reported, which adds the period related to the validity period of the respective food.

We recommend that predictable adverse reactions be presented in the technical specification of the product. In order for information on nutrivigilance (adverse reactions, contraindications, and interactions of food with drugs) to reach patients, in order not to load the food label with this information, one solution is for economic agents to transmit this information to the national authority responsible for nutrivigilance, and the "Authority", to enter the information in a database.

This solution can also be applied to food supplements. Information on side effects, contraindications, and food-drug interactions must be visible to patients or healthy individuals and health professionals (pharmacists, doctors, dietitians, nutritionists, and physiotherapists). In the case of nutrivigilance CCPn 1 AR (adverse reaction), CCPn 2 C (contraindications), CCPn 3 IM (drug interaction) can be established in the post-sale stage, by the "Authority". As a result, the implementation of nutrivigilance in the food industry and that of food supplements according to HACCP principles, in the research-development stage involves principles 1,2,3,4, 6, and 7. Principles 5 and 6 are applicable to the "Authority".

Given that certain ingredients can alter the absorption of certain drugs, such as apple juice [

21], and in the case of certain food products, they undergo heat treatment and patients consume a certain amount of these foods, the question can be raised whether these foods influence drug clearance. In order to be able to respond from the point of view of evidence-based medicine, these possible side effects must be monitored and analyzed. Another method is to carry out preclinical studies on animal species and to see if a certain food influences the absorption of a drug (e.g. preclinical study to see if the simple jellies developed in this research influence the absorption of statins (Prasvastatin). Also, we must report apple allergies, because the two proteins LTP (Mal d3) and TLP are not destroyed by heat (heat treatment) [

20].

Since there is also information regarding adverse effects and interactions, which are not scientifically documented, for nutrivigilance, there may be cases when other information can be taken into account, with mention of the source, and the monitoring of possible adverse reactions and in-interactions with drugs, thus so that the "Authority" can create a database. Depending on the adverse reactions received from consumers, including patients and health professionals, respectively the information received from economic agents, to be able to periodically evaluate this database.

Regarding the qualification of the human resources involved in the implementation of nutrivigilance, they can be engineers in food technology and control, with qualifications in pharmacovigilance or nutrivigilance, pharmacists, or physicians. Healthcare professionals can collaborate with economic agents in the food or food supplement industry, based on a collaboration or consultancy contract.

Given that not all new ingredients authorized in the EU have drug interaction information (e.g. Acheta domesticus powder), we recommend that they be included in future research in vitro or in vivo (in animal models), for research on influencing the clearance of drugs metabolized by certain enzymes (e.g. cytochrome P450).

For food industry specialists, manufacturing food with newly authorized EU ingredients requires a complex knowledge of technology, technical quality control, and food safety. In the context of nutrivigilance, knowledge of evidence-based medicine is also added.

We believe that the method we propose is useful starting with the research–development of food and food supplements, followed by post-sale analysis, and also can be a model for other countries from UE to follow.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of nutrivigilance in the Romanian food industry, food supplements, and healthcare system represent a real tool in improving the national public health management by preventing adverse reactions, contraindications, and interactions with drugs, and decreasing the costs of the health system. Also, it will create a European network of this area, to be sustainable and evidence-based medicine. The sustainability of this measure requires the publication of a detailed Guide that represents an aid for economic agents. In order for the "Authority" and economic agents to be able to interact on the subject of "Nutrivigilance", it must be legislated. From our knowledge, the proposal regarding the implementation of nutrivigilance in the stage of research-development of food and food supplements, based on HACCP principles, is unique.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Irina M Matran, Monica Tarcea, Daniela Cîrnatu, Simona Pârvu and Sorin Gabriel Ungureanu.; Irina M. Matran, Daniela Cîrnatu; software, Monica Tarce, Florin C. Buicu; validation, Sorin Gabriel Ungureanu, Daniela Cîrnatu and Simonas Pârvu; formal analysis, Florin C. Buicu.; investigation, Irina M. Matran; resources, Irina M. Matran and Daniela Cîrnatu; data cleaning, Daniela Cîrnatu and Monica Tarcea.; written — Irina M Matran, Daniela Cîrnatu; writing—review and editing, Monica Tarcea; visualization, Sorin Gabriel Ungureanu, Simona Pârvu and Florin C. Buicu.; supervision, Monica Tarcea and Simona Pârvu; project management, Irina M. Matran; funding acquisition, Monica Tarcea All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Radim, J.S. Impact of Air Pollution on the Health of the Population in Parts of the Czech Republic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Münzel, T.; Hahad, O.; Daiber, A.; Landrigan, P.J. Soil and water pollution and human health: what should cardiologists worry about? Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.M.; David, F.; Shin, M.; Vaidyanathan, A. Community drinking water data on the National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network: a surveillance summary of data from 2000 to 2010. Environ Monit Assess 2019, 191, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogoșan, C.I.; Farcaș, M.A.; Bucșa, CD.; Voștinaru, O.; Ghibu Morcovan, S.M. Generalities. In Introduction to Pharmacovigilance. 1nd ed.; Edit. Risoprint, Cluj-Napoca, 2013.

- Zazzara, M.B.; Palmer, K.; Vetrano, D.L.; Carfì, A.; Onder, G. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: a narrative review of the literature. Eur Geriatr Med 2021, 12, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, H.; Watanabe, T.; Ando, M.; Katsumata, N. An alternative medicine, Agaricus blazei, may have induced severe hepatic dysfunction in cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2006, 36, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suehiro, M.; Katoh, N.; Kishimoto, S. Cheilitis due to Agaricus blazei Murill mushroom extract. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 56, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschke, R.; Genthner, A.; Wolff, A.; Frenzel, C.; Schulze, J.; Eickhoff, A. Herbal hepatotoxicity: analysis of cases with initially reported positive re-exposure tests. Dig Liver Dis 2014, 46, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, C.; Musch, A.; Schirmacher, P.; Kruis, W.; Hoffmann, R. Acute hepatitis induced by an Aloe vera preparation: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005, 11, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baretta, Z.; Ghiotto, C.; Marino, D.; Jirillo, A. Aloe-induced hypokalemia in a patient with breast cancer during chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2009, 20, 1445–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.N.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, B.H.; Sohn, K.M.; Choi, M.J.; Choi, Y.H. Aloe-induced toxic hepatitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2010, 25, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, L.F.; Luzzio, F.A.; Smith, S.C. , Hetman, M.; Champy, P.; Litvan, I. Annonacin in Asimina triloba fruit: implication for neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Furutani, Y.; Suto, Y.; Furutani, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yoneyama, M.; Kato, T.; Itabe, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Tomimatsu, Tanaka, H. T.; Kasanuki, H.; Masaki, T.; Kiyama, R.; Matsuoka, R. Estrogen-like activity and dual roles in cell signaling of an Agaricus blazei Murrill mycelia-dikaryon extract. Microbiol Res 2012, 167, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, N.; Akram, M.; Yaniv-Bachrach, Z. Daniyal, M. Is it safe to consume traditional medicinal plants during pregnancy? Phytother Res. 2021, 35, 1908–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engdal, S.; Nilsen, O.G. In vitro inhibition of CYP3A4 by herbal remedies frequently used by cancer patients. Phytother Res. 2009, 23, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Commission. Regulation (EC) no.852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council regarding the hygiene of food products. OJEU 2004, 139, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center – Aloe Vera-purported benefits, side-effects and more. 2023. Available online: https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/aloe-vera.

- Teschke, R.; Genthner, A.; Wolff, A.; Frenzel, C.; Schulze, J.; Eickhoff, A. Herbal hepatotoxicity: analysis of cases with initially reported positive re-exposure tests. Dig Liver Dis 2014, 46, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, C.; Musch, A.; Schirmacher, P.; Kruis, W.; Hoffmann, R. Acute hepatitis induced by an Aloe vera preparation: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005, 11, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissoni, P.; Rovelli, F.; Brivio, F.; Romano, Z.; Massimo, C. , Giuseppina, M.; Adelio, M.; Giorgio, P. A randomized study of chemotherapy versus biochemotherapy plus Aloe arborescens in patients with metastatic cancer. In Vivo 2009, 23, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.N.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.M.; Byoung, H.K.; Kyoung, M.S.; Myung, J.C.; Young, H.C. Aloe-induced toxic hepatitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2010, 25, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoqing, G.; Nan, M. Aloe vera: A review of toxicity and adverse clinical effects. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 2016, 34, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Djuv, A.; Nilsen, O.G. Aloe Vera Juice: IC (50) and Dual Mechanistic Inhibition of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Phytother Res 2011, 26, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Chui, P.T.; Aun, C.S.; Gin, T.; Lau, A.S. ; Possible interaction between sevoflurane and Aloe vera. Ann Pharmacother 2004, 38, 1651–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).