Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. Related Work

1.2.1. Estimating Used Car Prices

Classic Machine Learning.

Neural Networks - Multi-Layer Perceptron.

Deep Neural Networks.

1.2.2. Computer Vision Models for Image Processing

1.3. Research Objective

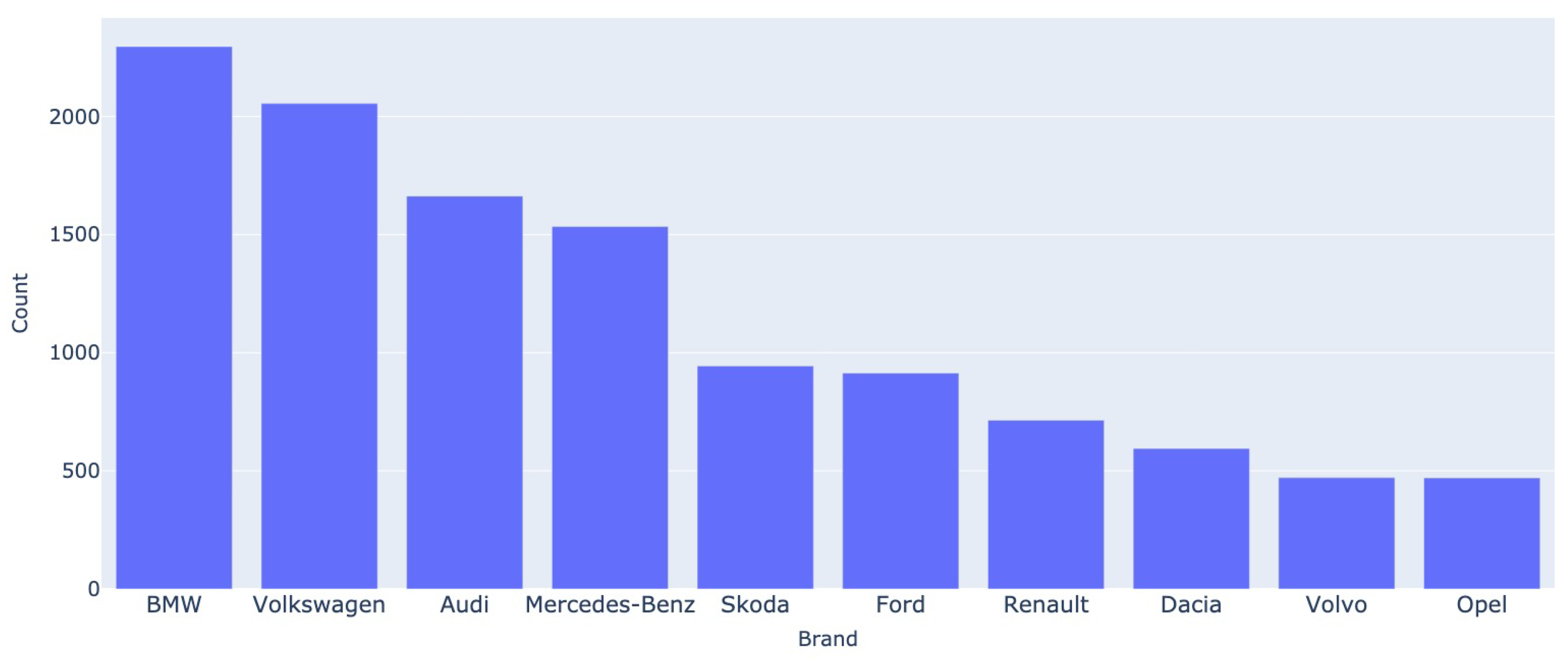

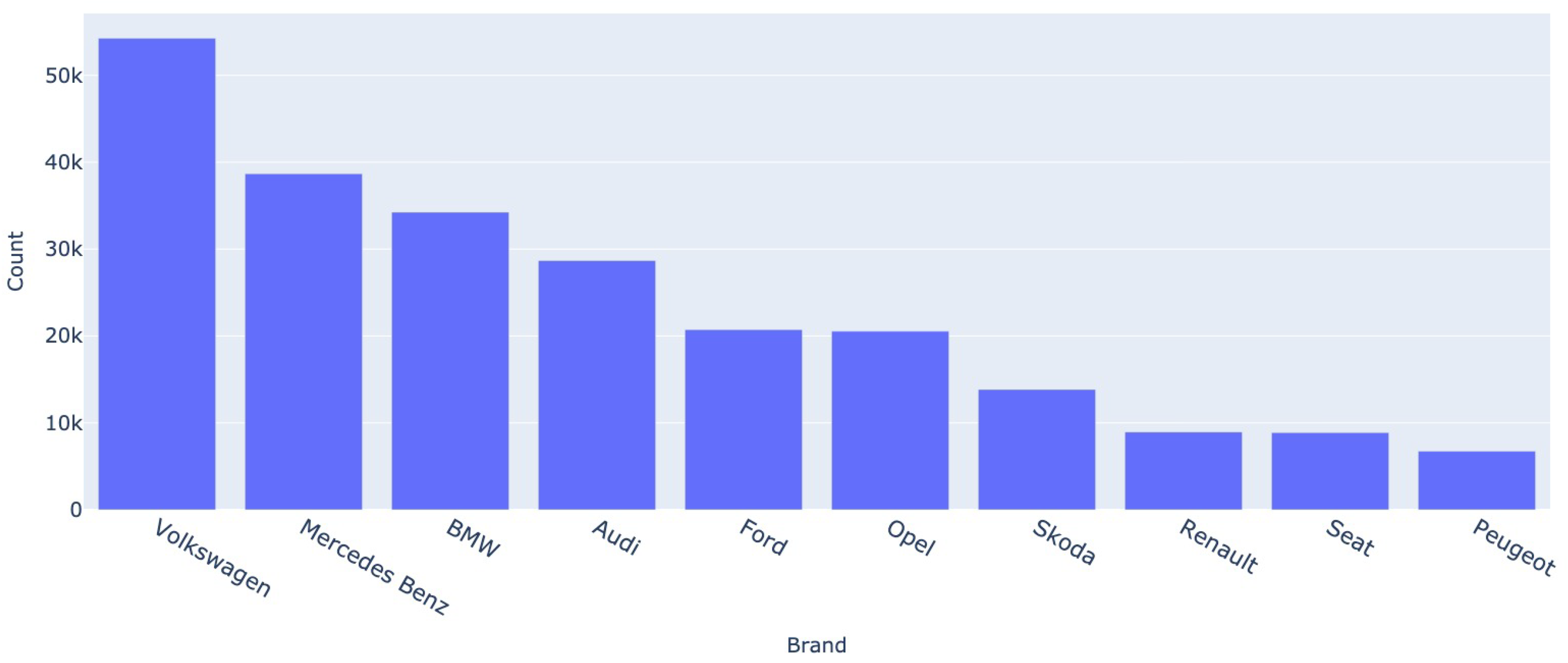

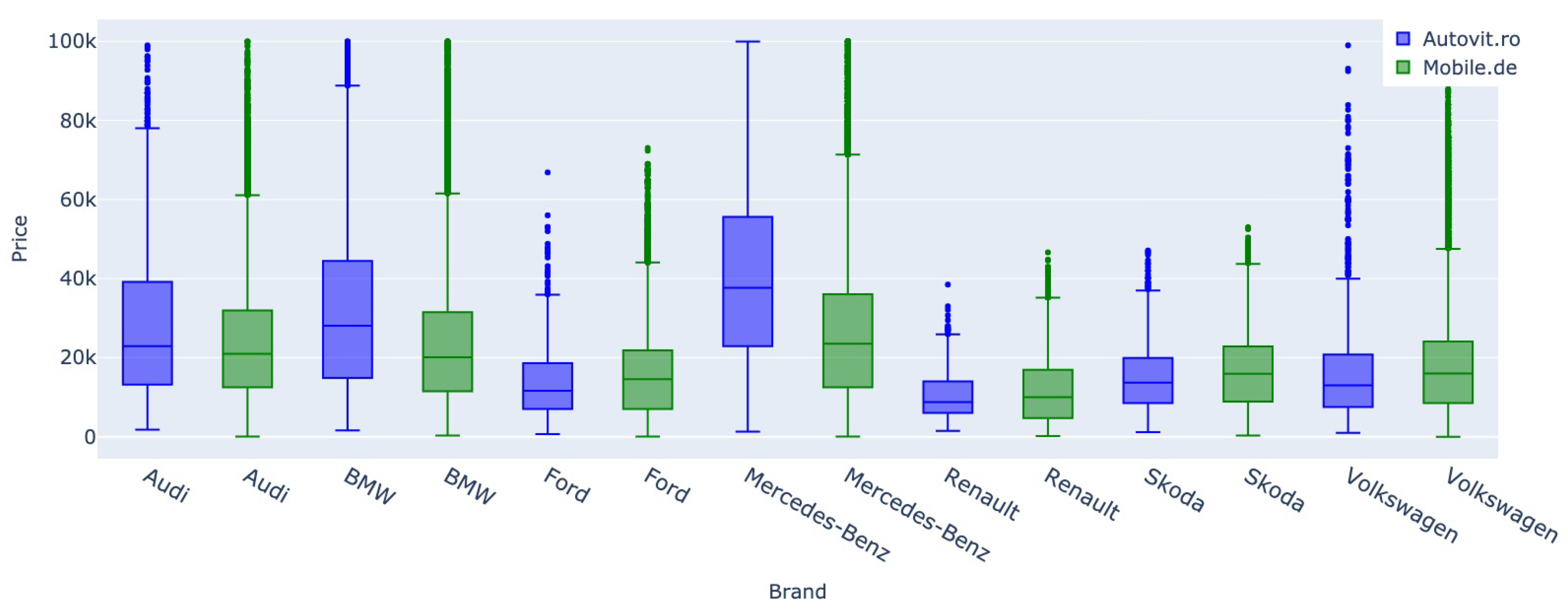

- Create a comprehensive dataset comprising over 300,000 entries from the German market and a second dataset comprising more than 15,000 car quotes from the Romanian market. These datasets serve as valuable resources for training deep prediction models and enable a comparative analysis of behavior and prediction models between the emerging Romanian and well-established German markets. To our knowledge, these combined datasets create the largest corpus analyzed to date and represent the base for the first cross-market analysis on fine-tuning Deep Learning models.

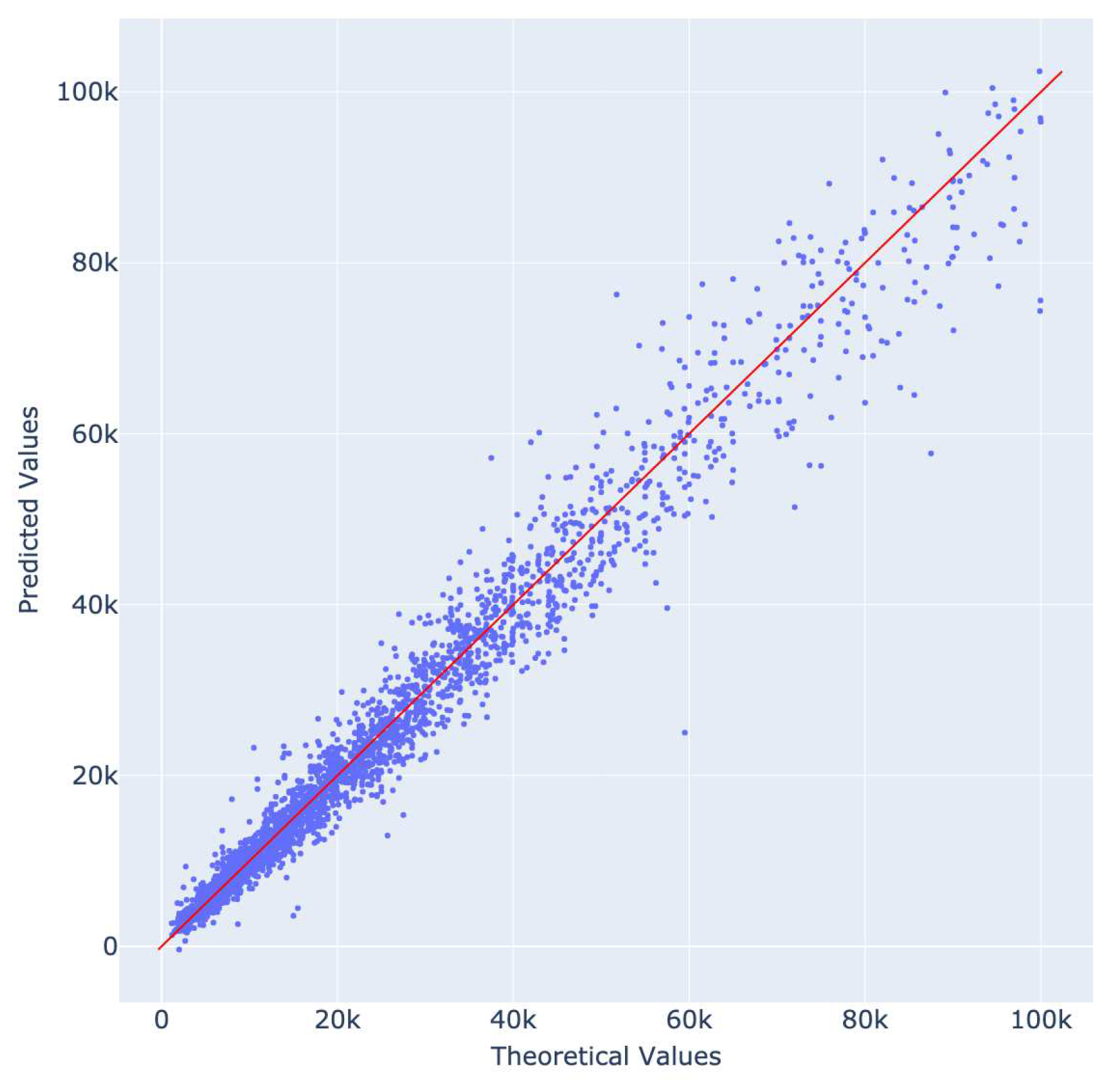

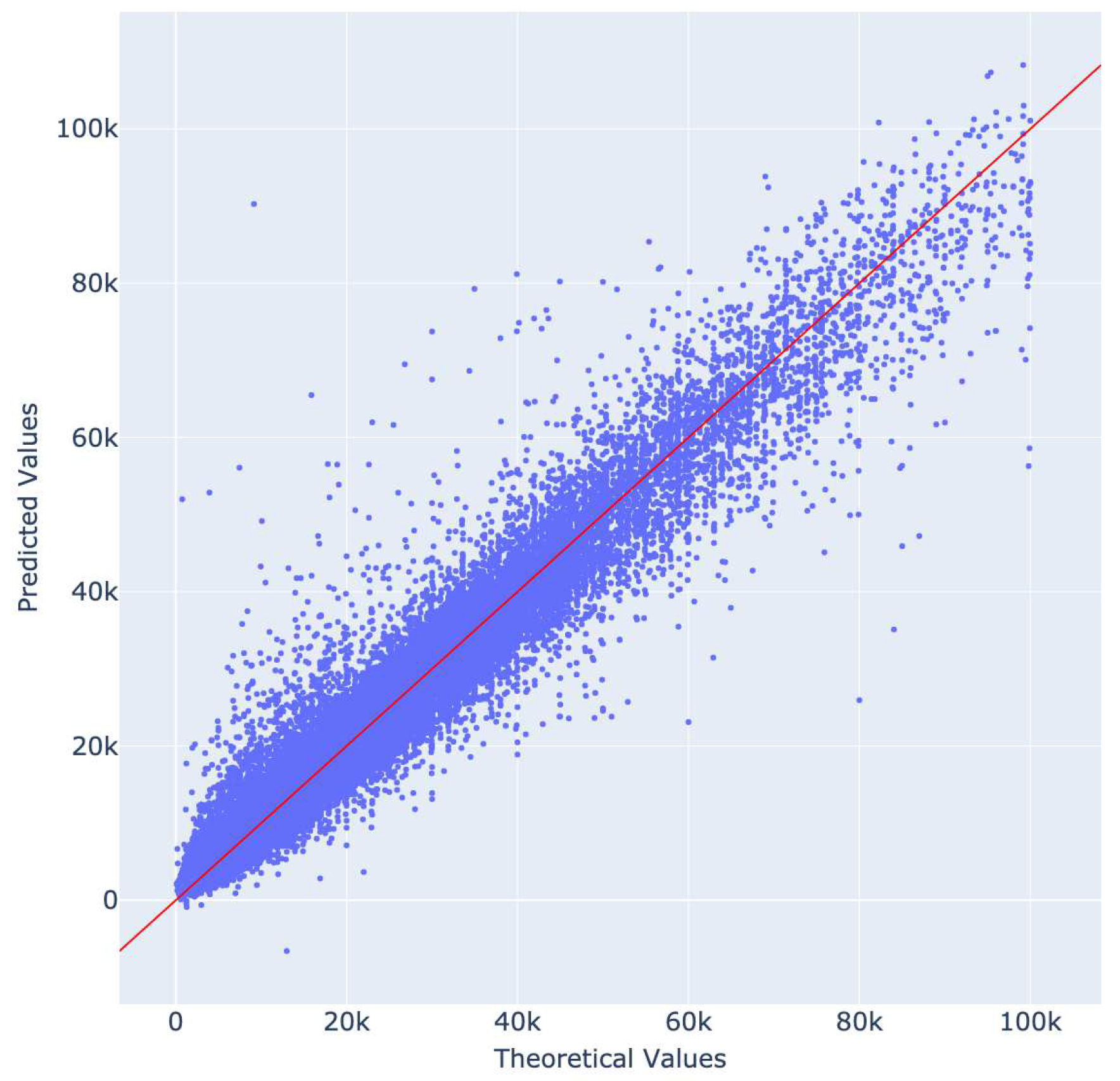

- Introduce state-of-the-art approaches for developing advanced prediction models that accurately estimate used car prices by considering multiple types of features, trainable embeddings, multi-head self-attention mechanisms, and convolutional neural networks applied to the car images. These models achieve high prediction accuracy, with the R2 score exceeding 0.95. Moreover, we added to these findings an extensive ablation study to showcase the most relevant features, while an error analysis was also performed to study the models’ limitations.

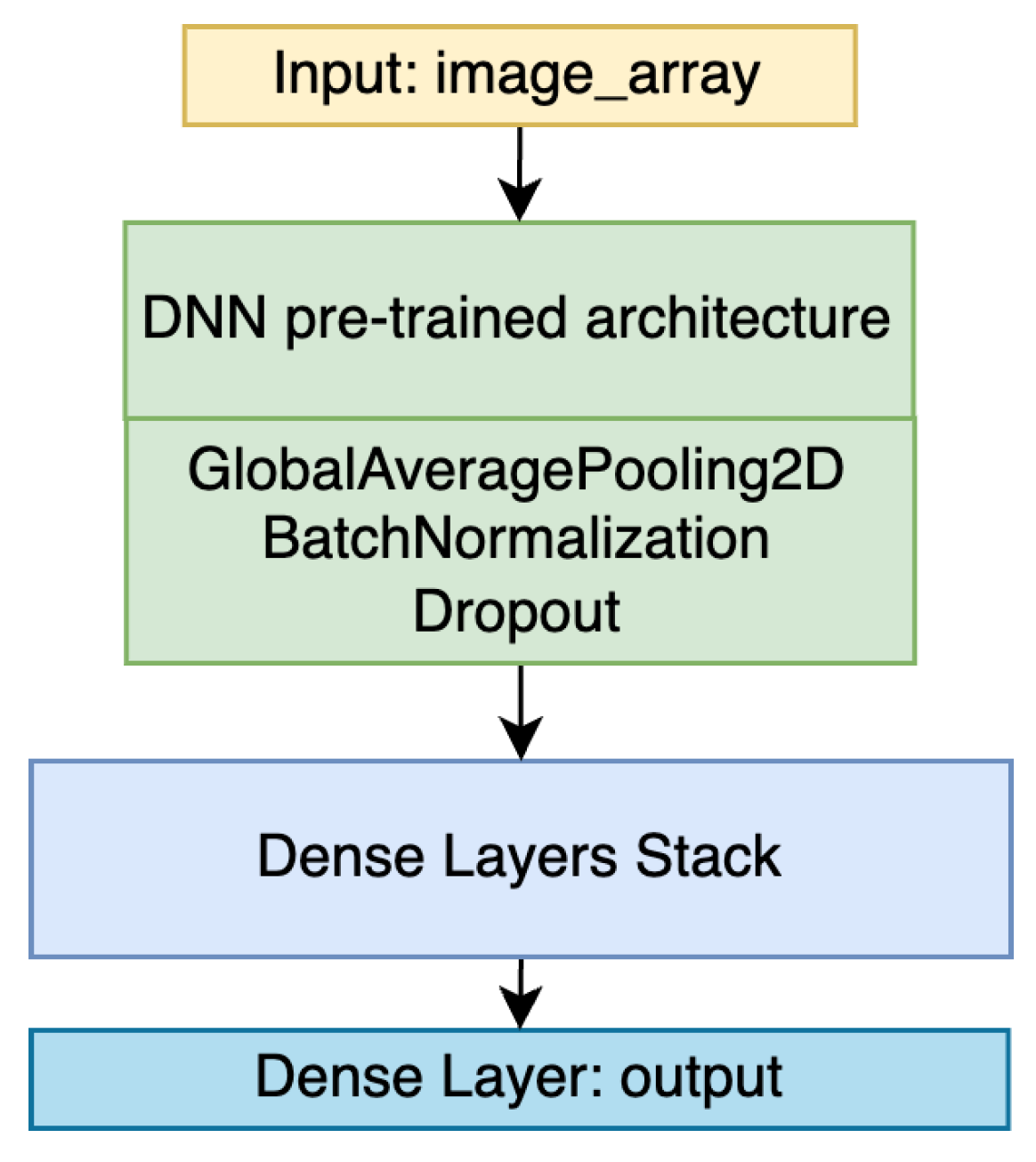

- Create a baseline model that employs convolutional architectures to predict car prices based solely on visual features extracted from car images. This model demonstrates transfer-learning capabilities, enabling improved prediction accuracy, particularly for low-resource training datasets. This highlights the potential for leveraging visual information alone to predict car prices accurately.

2. Method

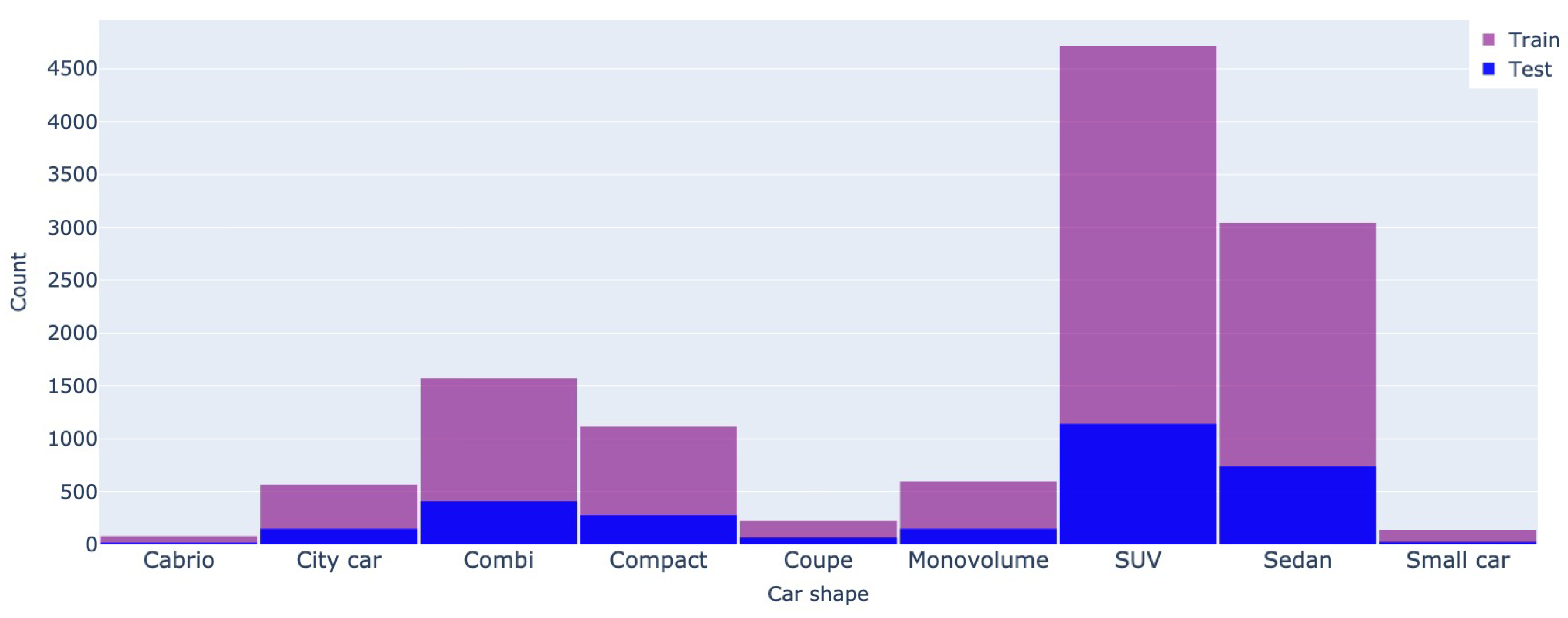

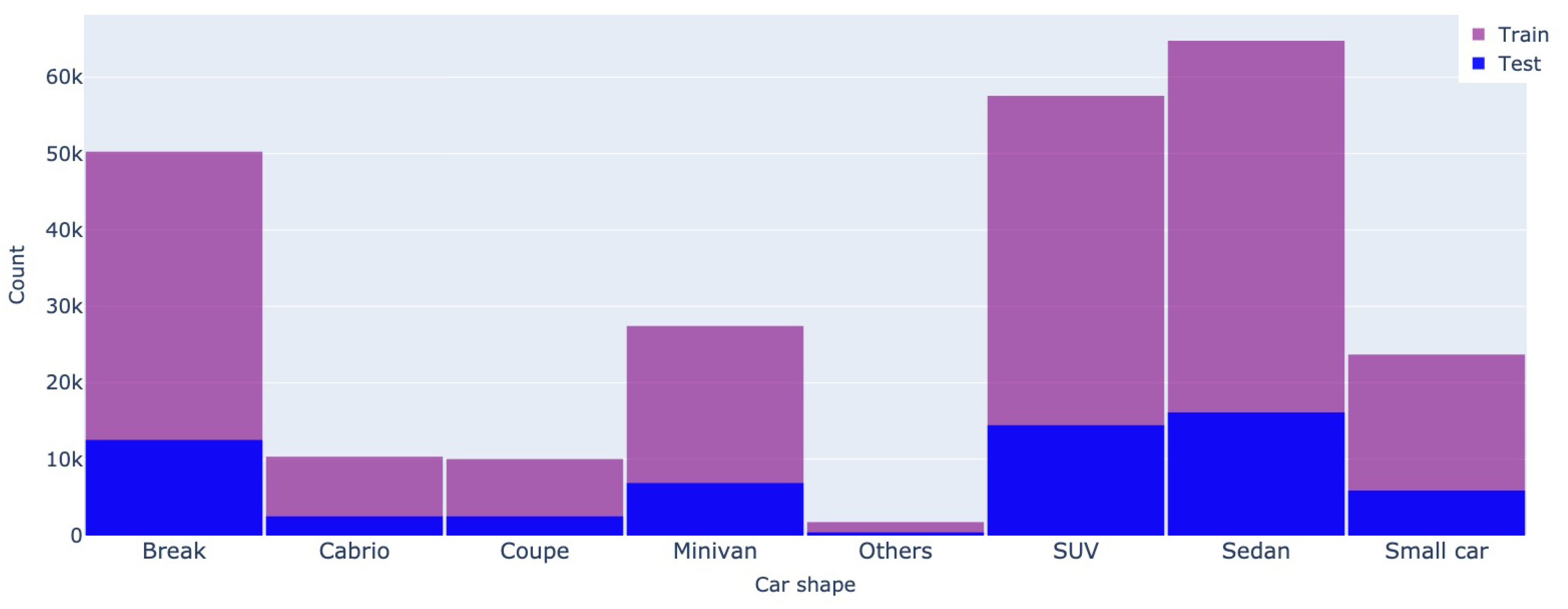

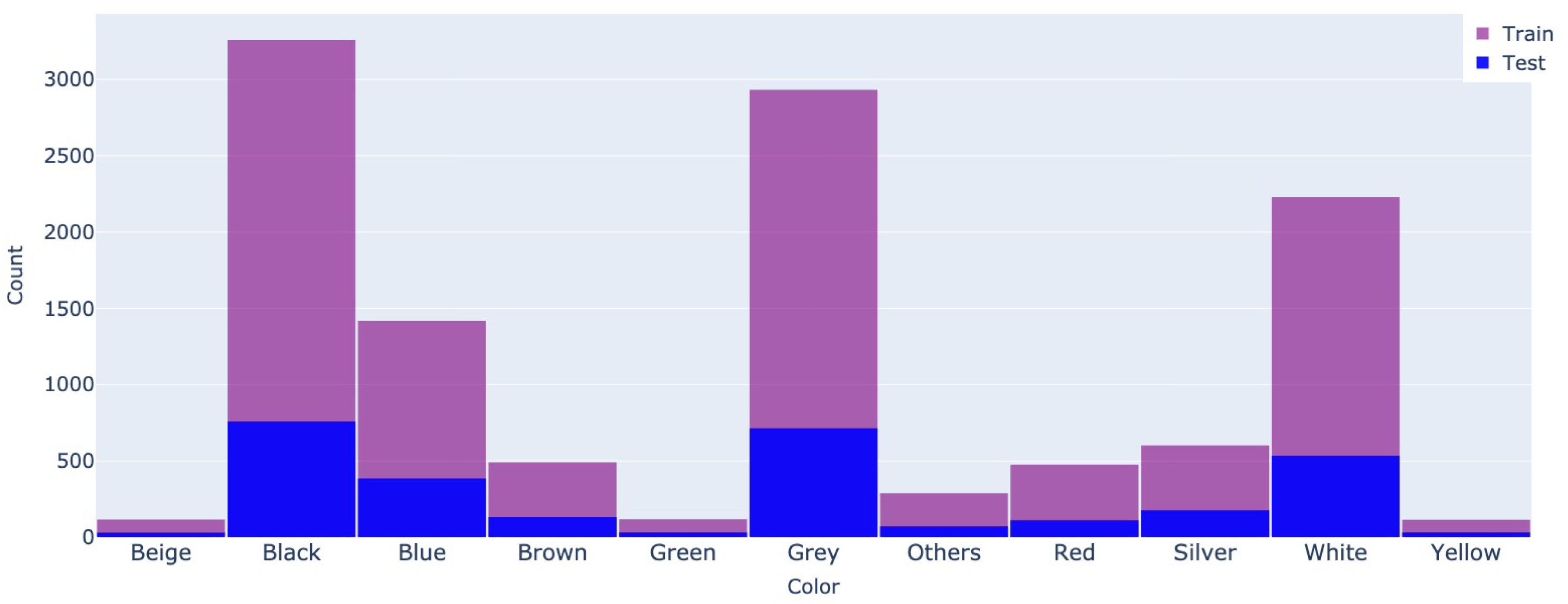

2.1. Datasets

- Mobile.de ads do not explicitly contain the categorized car brand and model but rather a title written by the seller. We extracted these two relevant features from the title using a greedy approach of matching them against an exhaustive list of all car brands and models and choosing the most fitted one. Finding a category was impossible for some ads, and these entries were dropped from the dataset.

- We discarded the ads that did not contain the relevant features mentioned above and those that did not contain at least an image of the car’s exterior. As some sellers published multiple images, some irrelevant to the ad or not showing the entire vehicle, we only considered images that contained the full car exterior. This filtering was done with the help of a YOLOv7 model [30] that detected a bounding box for a car image. Images displaying multiple cars without a prominent focus (e.g., parking lots) or having car bounding boxes occupying less than 75% of the entire image size were removed from the dataset.

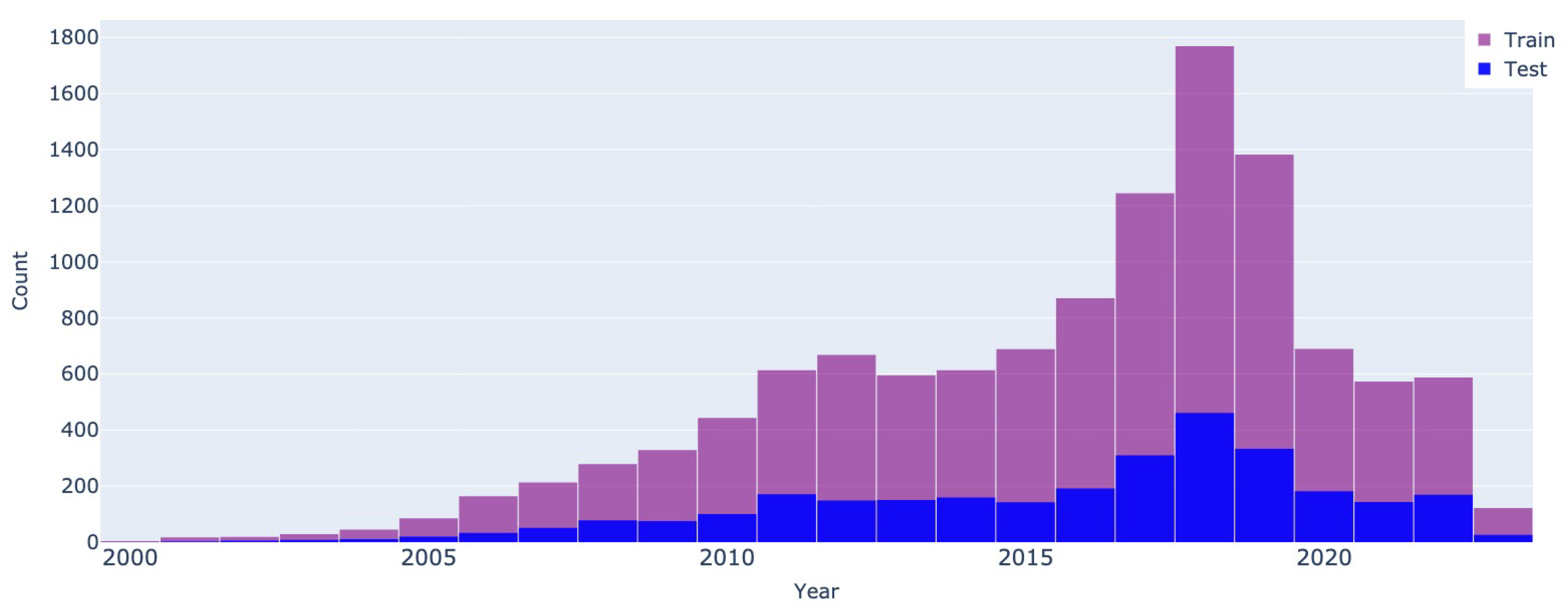

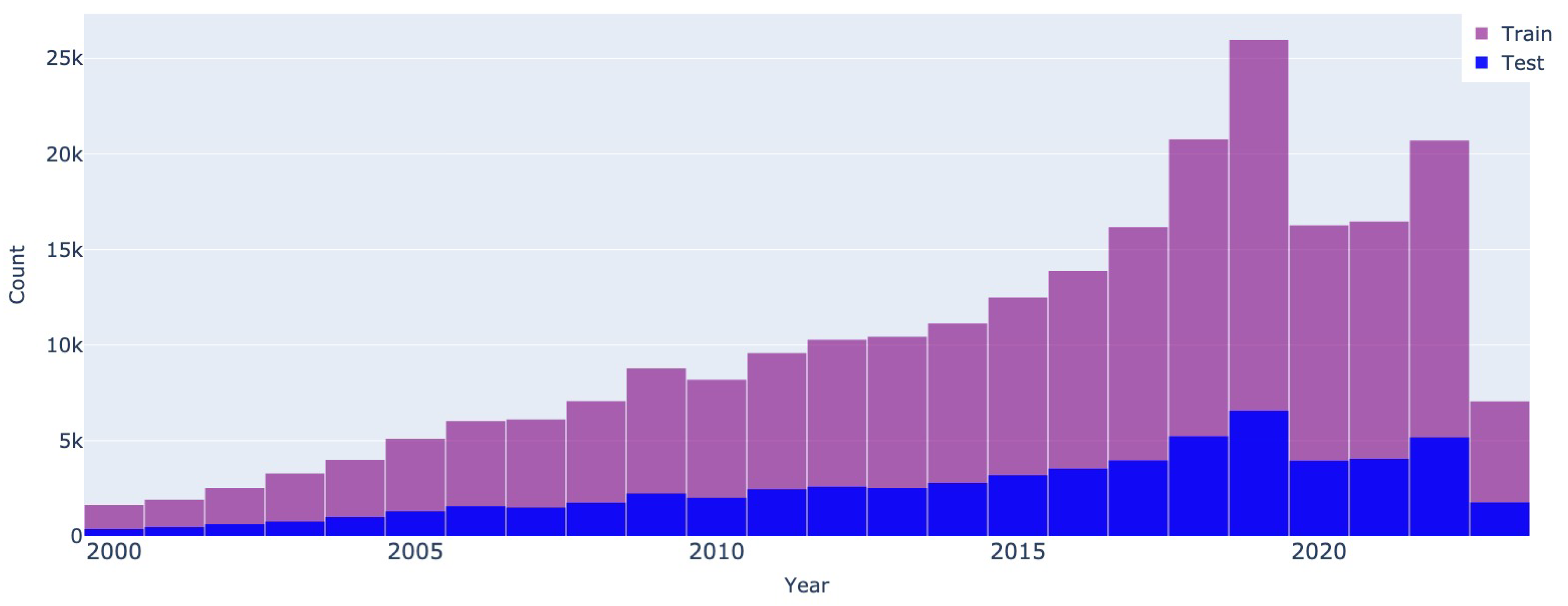

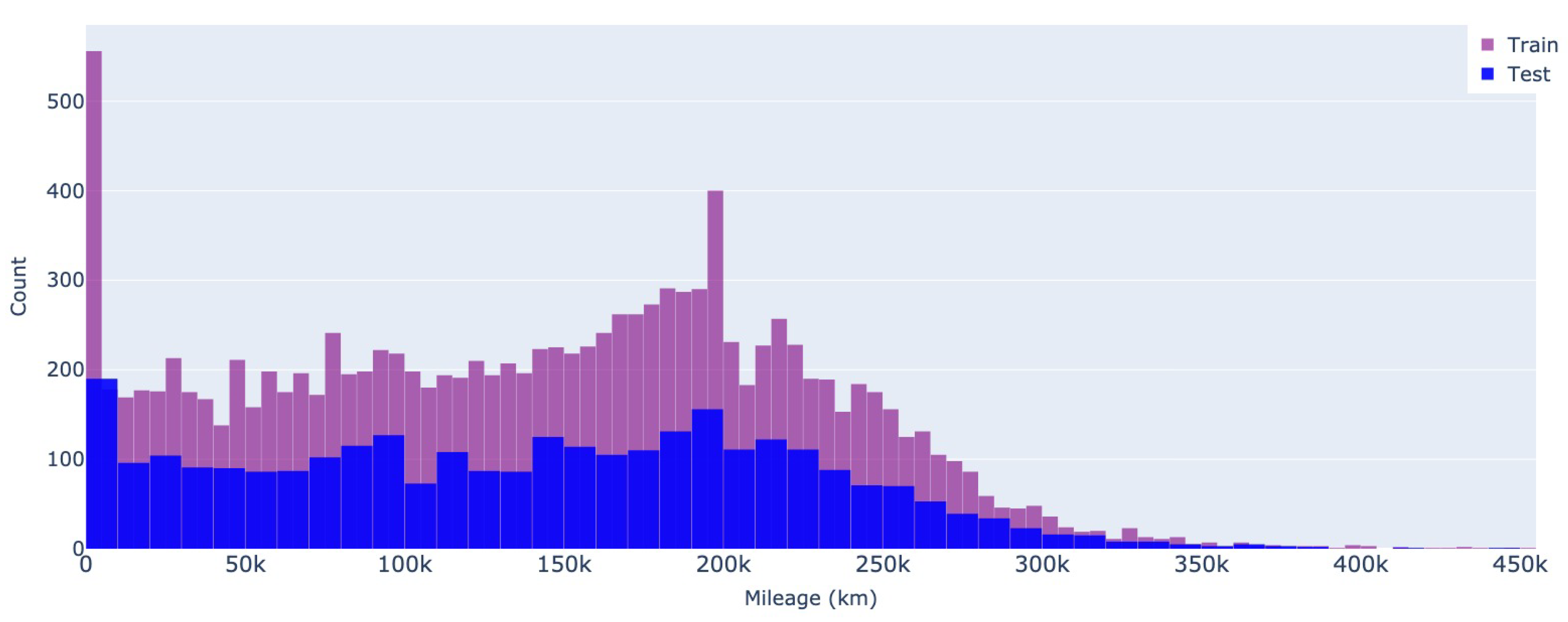

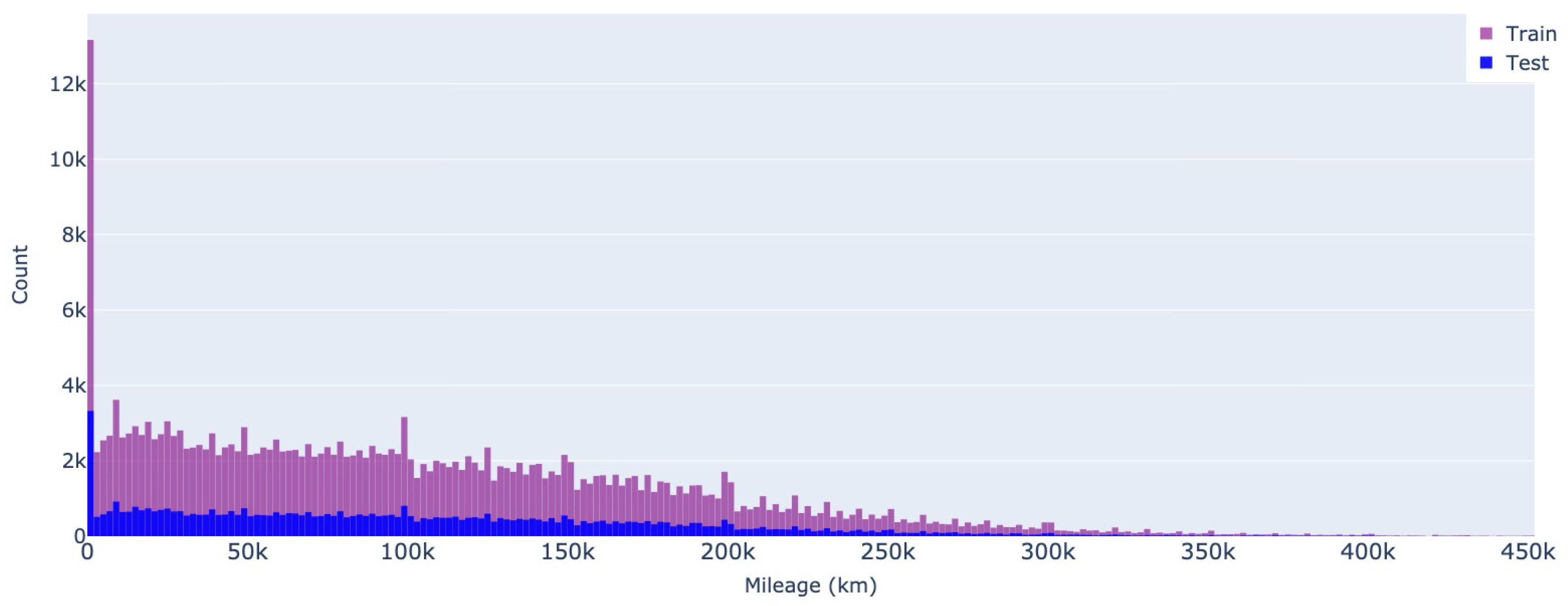

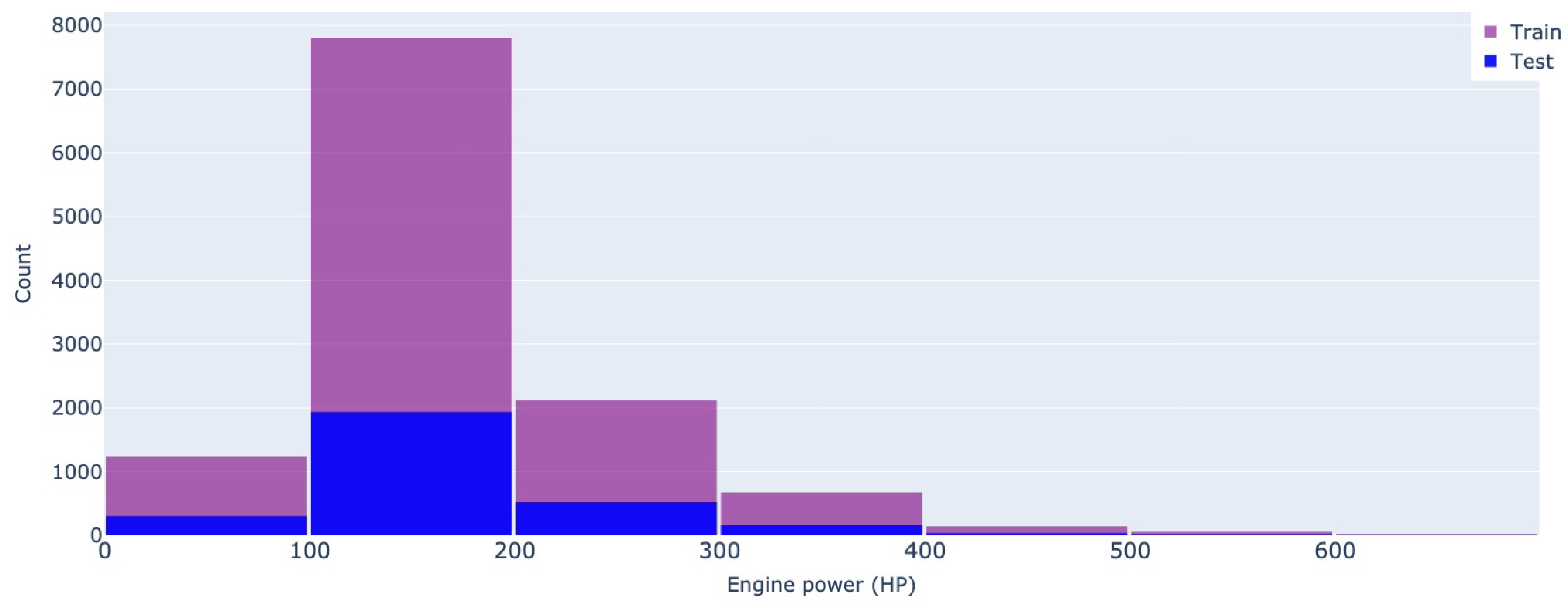

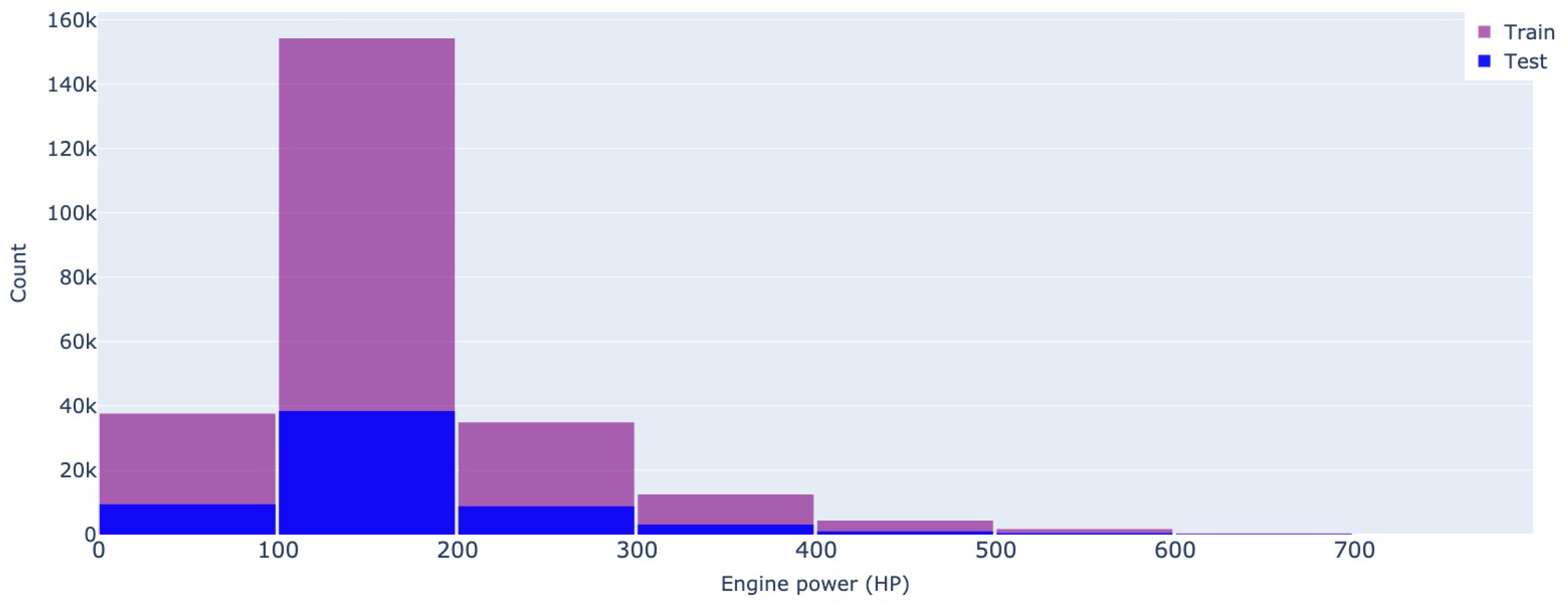

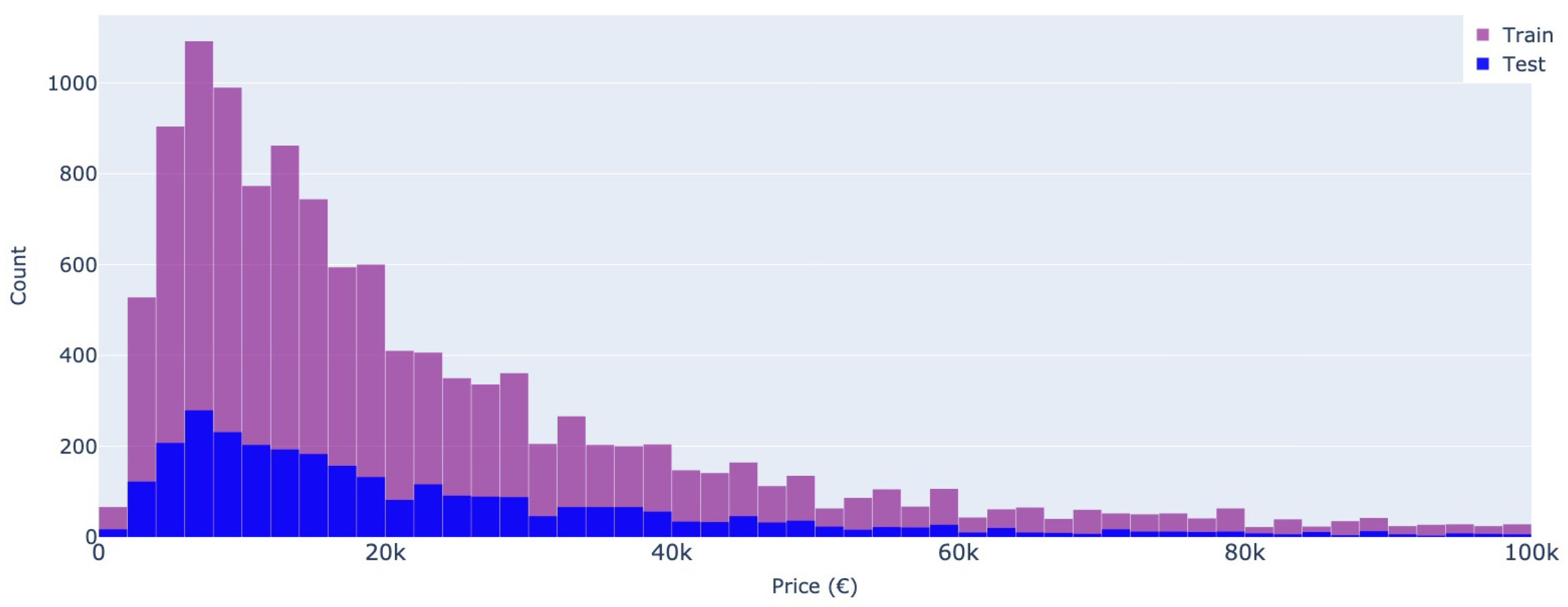

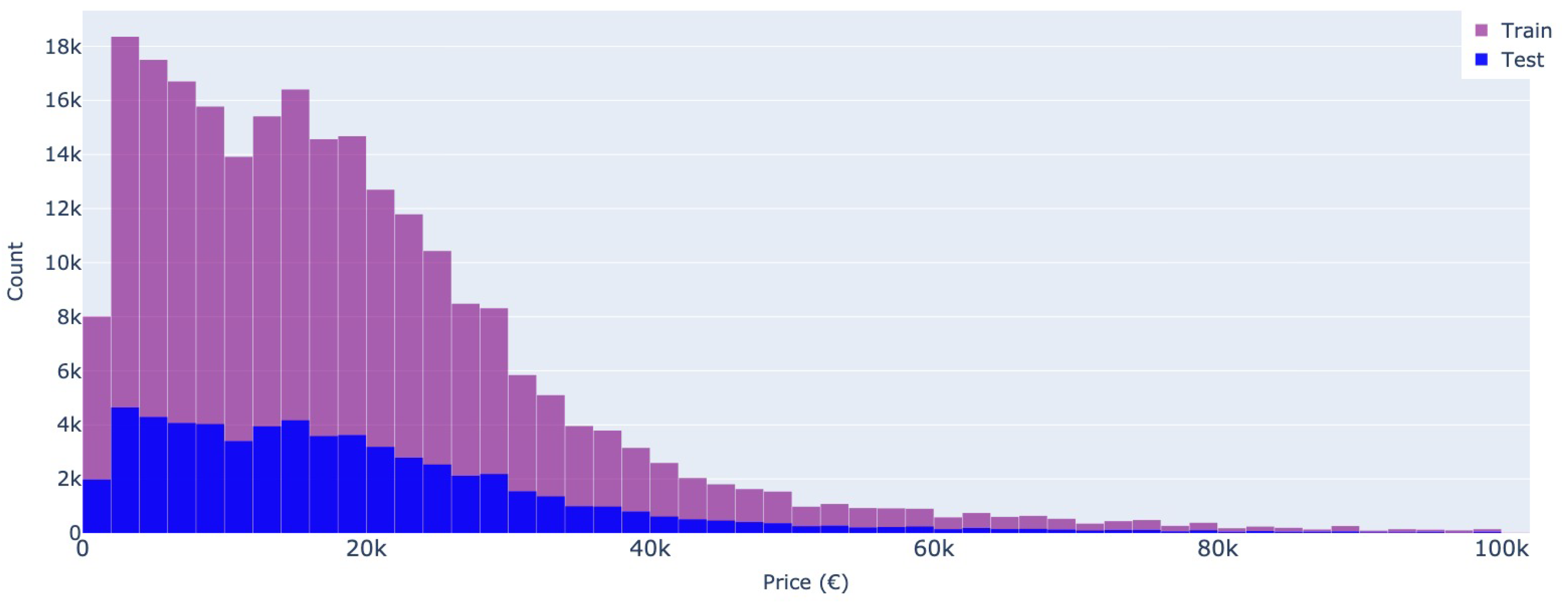

- To maintain precision and minimize the presence of erroneous data, listings with questionable features were eliminated, as they could potentially contain inaccurate information. Thus, we excluded cars with a manufacturing year before 2000, a mileage exceeding 450,000 kilometers, a price surpassing 100,000 Euros, and an engine power exceeding 600 horsepower.

- The dataset was split randomly into an 80% training set and a 20% validation set; however, we ensured a balanced distribution of car brands in each subset. Notably, a car advertisement could include multiple images, resulting in multiple entries within the dataset (one for each image). However, measures were taken to ensure that the training and validation sets did not contain the same advertisement but rather different ads, each with their respective images.

- Within the training dataset, we calculated each car model’s mean and standard deviation. Subsequently, we removed outlier listings from the entire dataset that fell outside the range defined by . When considering car models with less than 20 instances in the dataset, we calculated the mean and standard deviation for the car manufacturer instead to ensure meaningful measurements because the car manufacturer category contains an adequate number of entries for each group. We determined the mean and standard deviation on a per-model basis for frequently represented car models (i.e., with over 20 sale ads).

2.2. Gradient Boosting Methods

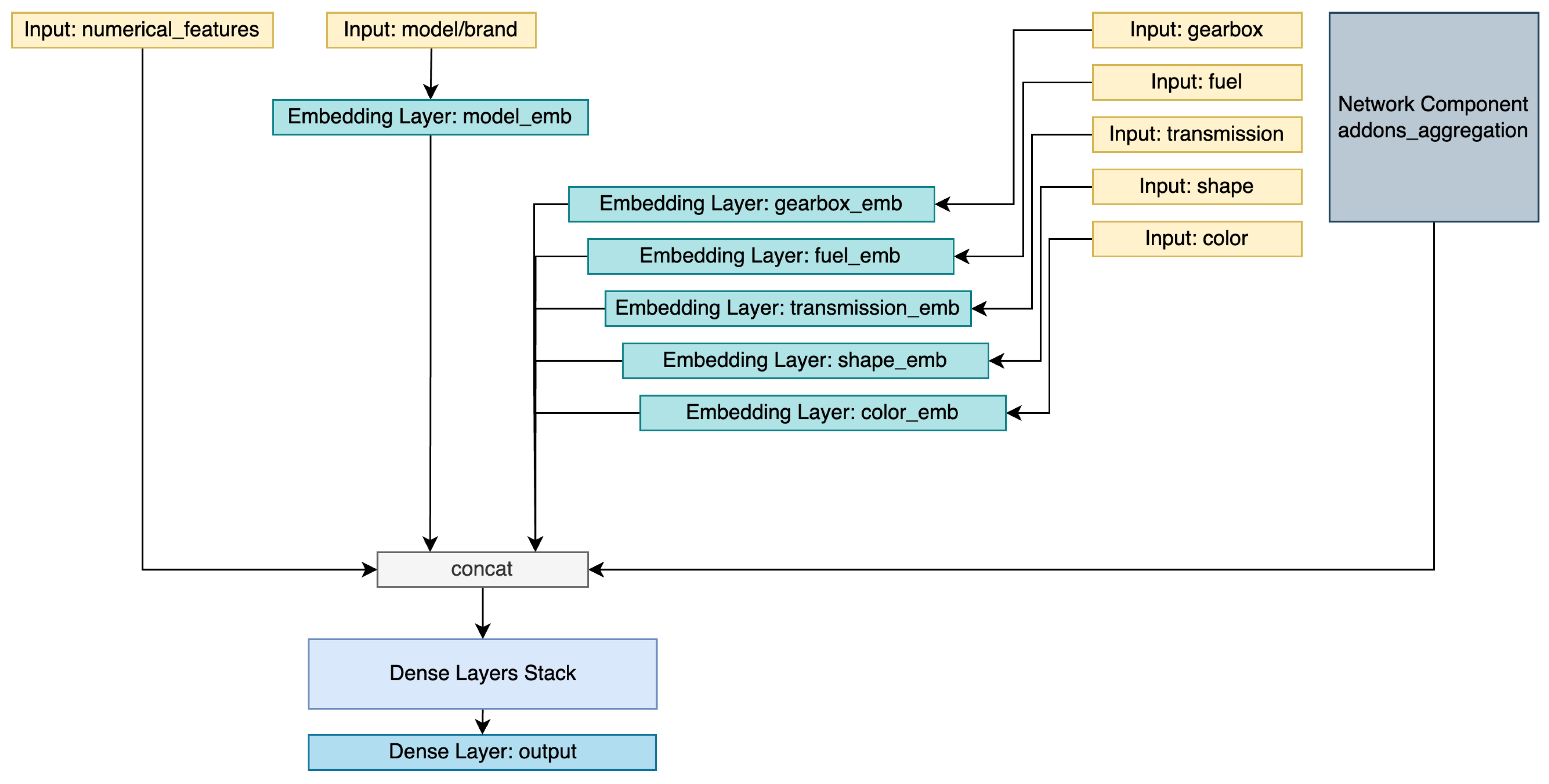

2.3. Neural Networks Methods

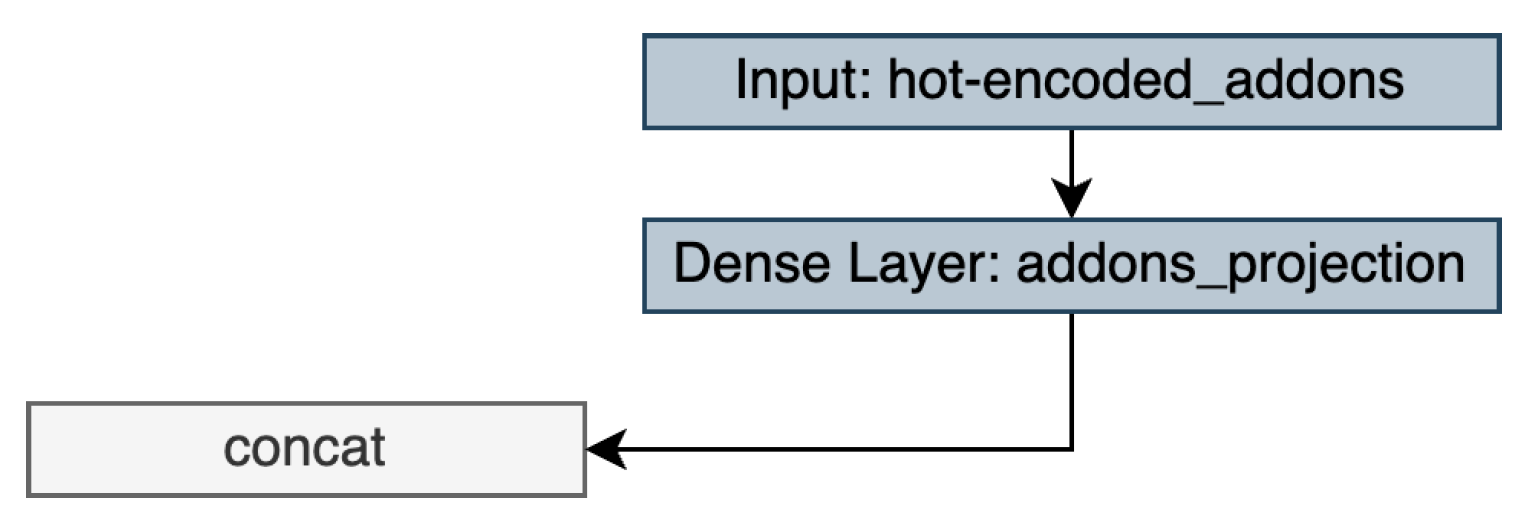

2.3.1. Neural network with hot-encoded add-ons projection

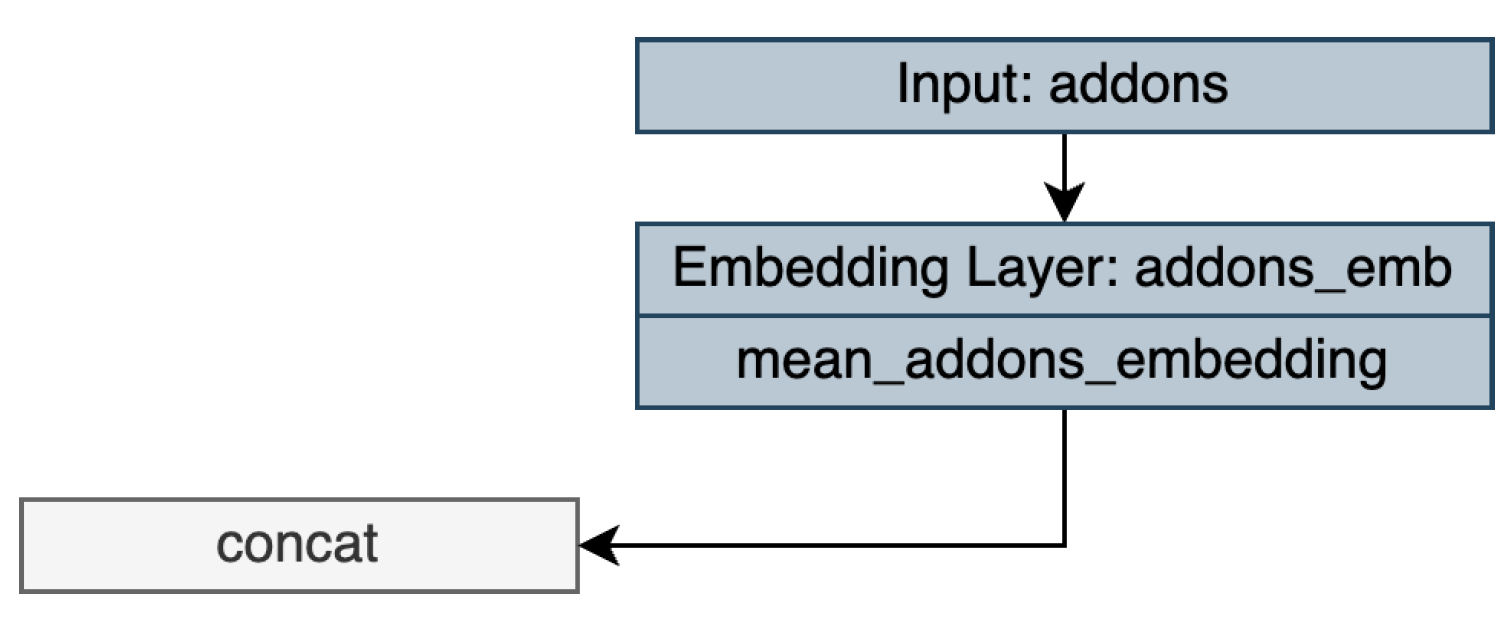

2.3.2. Neural network with mean add-ons learned embeddings

2.3.3. Neural network with add-ons embeddings and multi-head self-attention

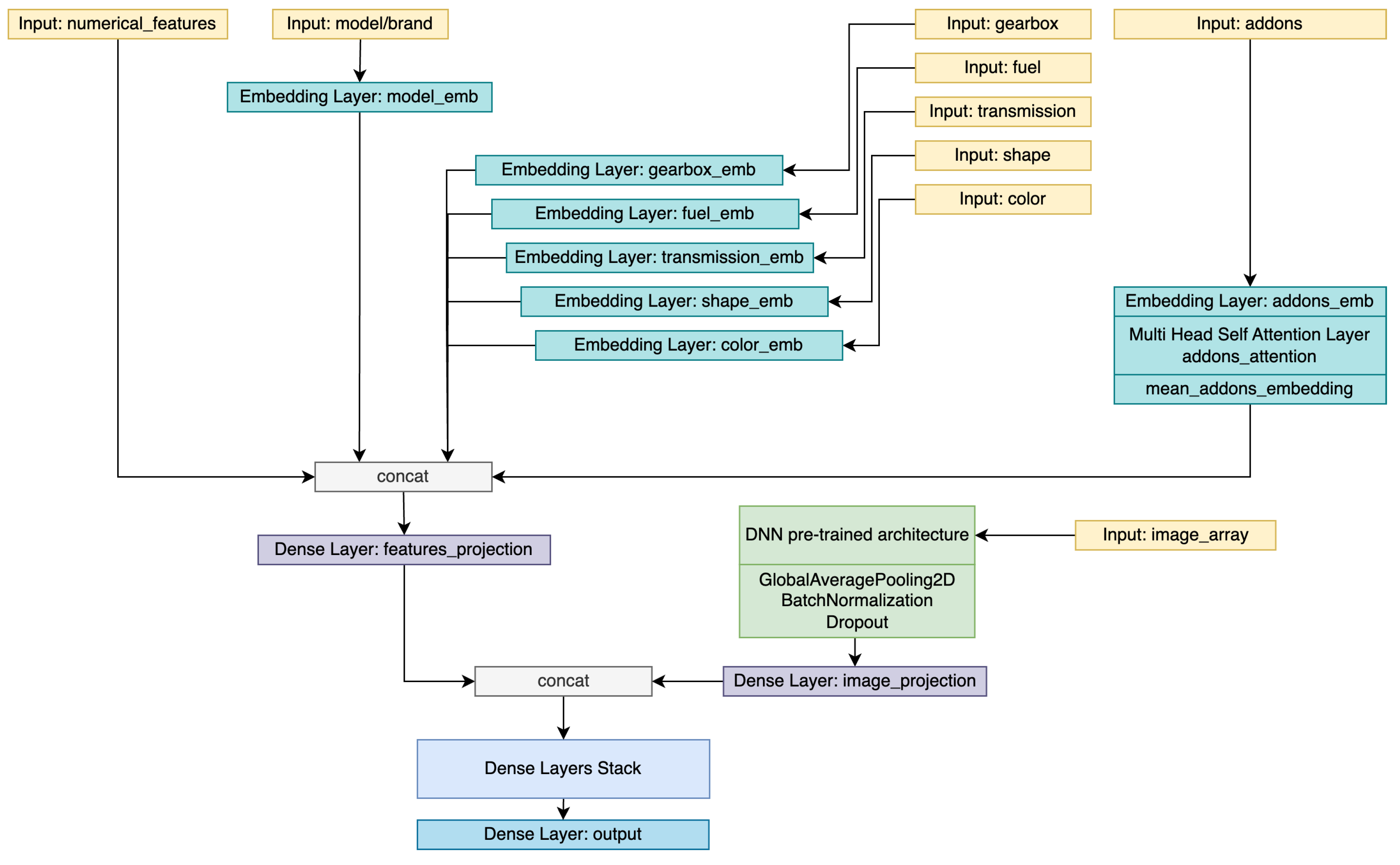

2.3.4. Deep neural networks for Image Analysis and Add-ons Multi-head Self-attention

2.4. Experimental Setup

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Ablation Study

4.2. Transfer Learning Capabilities

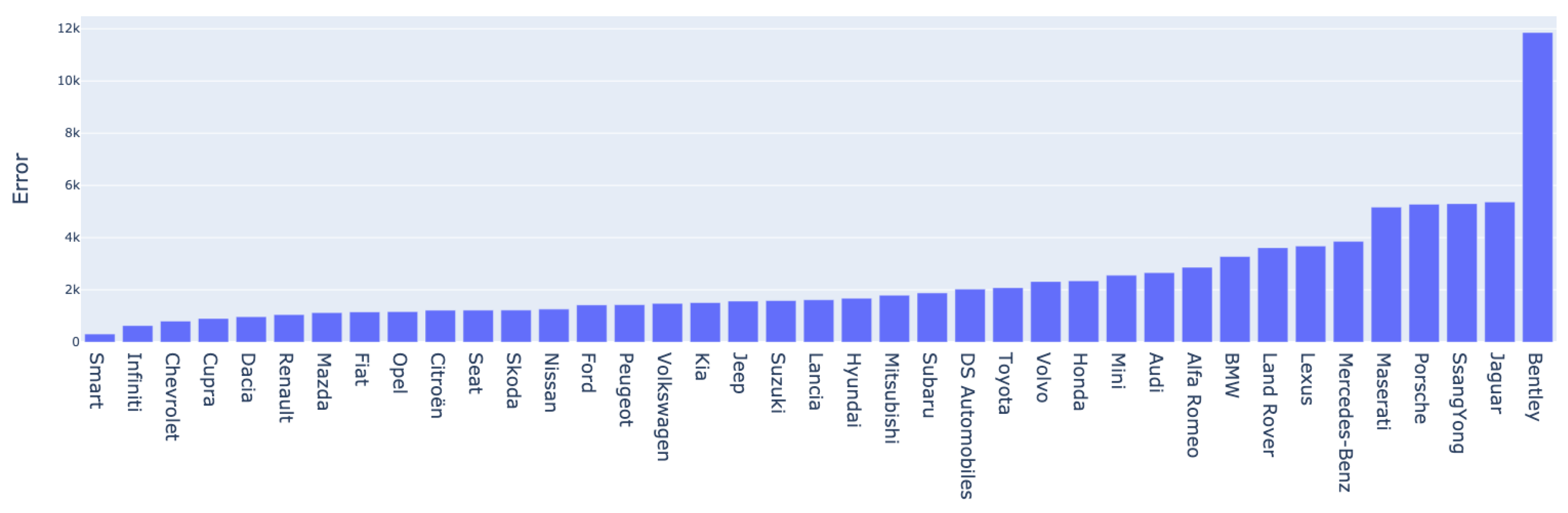

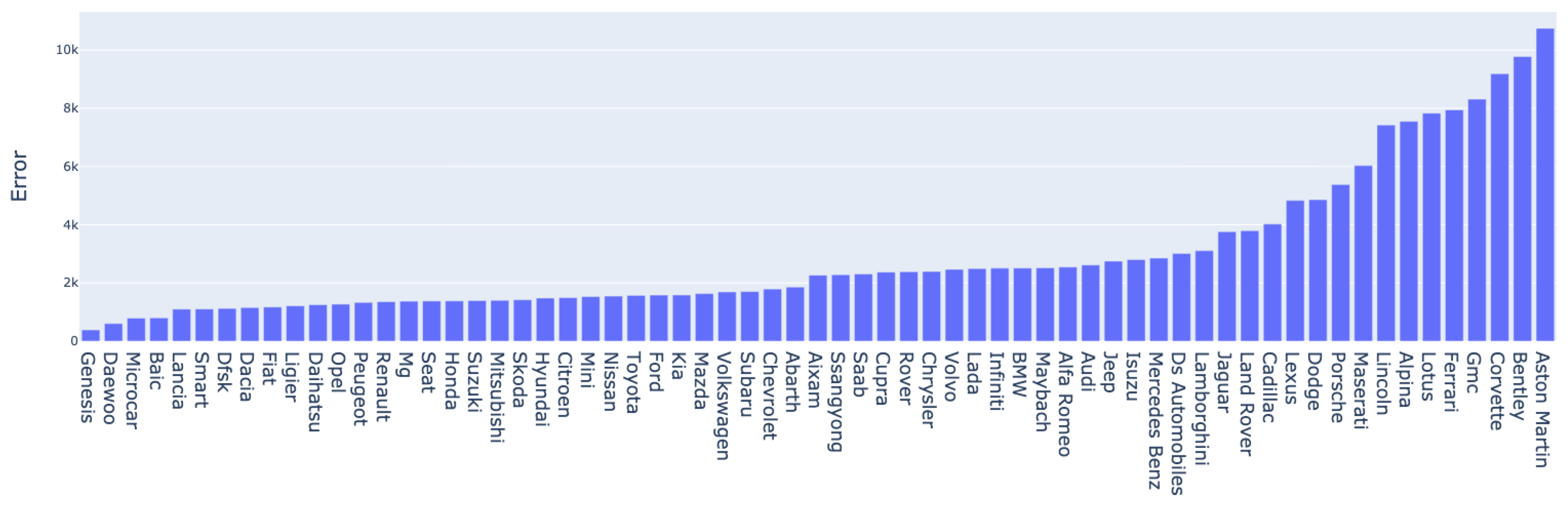

4.3. Error Analysis

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPNN | Backpropagation Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| GRA | Grey Relation Analysis |

| GT | Ground Truth |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| HP | Horse Power |

| KNN | K-Nearest-Neighbour |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MedE | Median Error |

| NN | Neural Network |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

Appendix A. Hyperparameter search options

| Method | Hyperparameters | |

| Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | |

| XGBoost | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| max depth: | max depth: | |

| min child weight: | min child weight: | |

| subsample: | subsample: | |

| colsample bytree: | colsample bytree: | |

| objective: squared error | objective: squared error | |

| NN with add-ons projection | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| addons projection: | addons projection: | |

| model embedding: | model embedding: | |

| fuel embedding: | fuel embedding: | |

| transmission embedding: | transmission embedding: | |

| gearbox embedding: | gearbox embedding: | |

| car shape embedding: | car shape embedding: | |

| color embedding: | color embedding: | |

| dense layer 1: | dense layer 1: | |

| dense layer 2: | dense layer 2: | |

| dense layer 3: | dense layer 3: | |

| NN with add-ons embedding | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| addons embedding: | addons embedding: | |

| model embedding: | model embedding: | |

| fuel embedding: | fuel embedding: | |

| transmission embedding: | transmission embedding: | |

| gearbox embedding: | gearbox embedding: | |

| car shape embedding: | car shape embedding: | |

| color embedding: | color embedding: | |

| dense layer 1: | dense layer 1: | |

| dense layer 2: | dense layer 2: | |

| dense layer 3: | dense layer 3: | |

| NN with self attention on add-ons embedding | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| addons embedding: | addons embedding: | |

| addons attention heads: | addons attention heads: | |

| addons attention key: | addons attention key: | |

| model embedding: | model embedding: | |

| fuel embedding: | fuel embedding: | |

| transmission embedding: | transmission embedding: | |

| gearbox embedding: | gearbox embedding: | |

| car shape embedding: | car shape embedding: | |

| color embedding: | color embedding: | |

| dense layer 1: | dense layer 1: | |

| dense layer 2: | dense layer 2: | |

| dense layer 3: | dense layer 3: | |

| DNN for image analysis and self attention on add-ons embedding | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| features projection: | features projection: | |

| image projection: | image projection: | |

| dense layer 1: | dense layer 1: | |

| dense layer 2: | dense layer 2: | |

| dense layer 3: | dense layer 3: | |

| DNN for image analysis and self attention on add-ons embedding | learning rate: | learning rate: |

| dense layer 1: | dense layer 1: | |

| dense layer 2: | dense layer 2: | |

| dense layer 3: | dense layer 3: | |

| dense layer 4: | dense layer 4: | |

References

- Moore, C. Used-vehicle volume hits lowest mark in nearly a decade. https://www.autonews.com/used-cars/used-car-volume-hits-lowest-mark-nearly-decade, 2023. Accessed on May 29, 2023.

- Pal, N.; Arora, P.; Kohli, P.; Sundararaman, D.; Palakurthy, S.S. How much is my car worth? A methodology for predicting used cars’ prices using random forest. Advances in Information and Communication Networks: Proceedings of the 2018 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Vol. 1. Springer, 2019, pp. 413–422.

- Gegic, E.; Isakovic, B.; Keco, D.; Masetic, Z.; Kevric, J. Car price prediction using machine learning techniques. TEM Journal 2019, 8, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, H.; Renqing, Z.; Meng, L.; Yang, Y. Used Car Price Prediction Based on the Iterative Framework of XGBoost+ LightGBM. Electronics 2022, 11, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Li, J.; Zheng, A.; Liu, H.; Jiang, T. Research on the Prediction Model of the Used Car Price in View of the PSO-GRA-BP Neural Network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samruddhi, K.; Kumar, R.A. Used Car Price Prediction using K-Nearest Neighbor Based Model. Int. J. Innov. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng.(IJIRASE) 2020, 4, 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kondeti, P.K.; Ravi, K.; Mutheneni, S.R.; Kadiri, M.R.; Kumaraswamy, S.; Vadlamani, R.; Upadhyayula, S.M. Applications of machine learning techniques to predict filariasis using socio-economic factors. Epidemiology & Infection 2019, 147, e260. [Google Scholar]

- Dutulescu, A.; Iamandrei, M.; Neagu, L.M.; Ruseti, S.; Ghita, V.; Dascalu, M. What is the Price of Your Used Car? Automated Predictions using XGBoost and Neural Networks. 2023 24th International Conference on Control Systems and Computer Science (CSCS), 2023.

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Machine learning 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; others. Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R package version 0.4-2 2015, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubbu, P.; Ganesh, M. Used Cars Price Prediction using Supervised Learning Techniques. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol.(IJEAT) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, S. Introduction to Multiple Regression: How Much Is Your Car Worth? Journal of Statistics Education 2008, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajera, P.; Gondaliya, A.; Kavathiya, J. Old Car Price Prediction With Machine Learning. Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. Technol. Sci 2021, 3, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Yang, R.R.; Chen, S.; Chou, E. AI blue book: vehicle price prediction using visual features. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.11227 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and< 0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7-9, 2015, Conference Track Proceedings; Bengio, Y.; LeCun, Y., Eds., 2015.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Ieee, 2009, pp. 248–255.

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2017, Vol. 31.

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1492–1500.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. ; others. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser. Ł; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, H.; Puig, X.; Xiao, T.; Fidler, S.; Barriuso, A.; Torralba, A. Semantic understanding of scenes through the ade20k dataset. International Journal of Computer Vision 2019, 127, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2207.02696 2022.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D.; Brucher, M.; Perrot, M.; Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, T.; Bursztein, E.; Long, J.; Chollet, F.; Jin, H.; Invernizzi, L. ; others. Keras Tuner. https://github.com/keras-team/keras-tuner, 2019.

| Feature | Value | Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Validation | Total | Train | Validation | Total | ||

| Transmission | 2x4 | 6,914 | 1,690 | 8,604 | 192,305 | 47,932 | 24,0237 |

| 4x4 | 5,125 | 1,282 | 6,407 | 53,561 | 13,453 | 67,014 | |

| Fuel | Diesel | 8,445 | 2,082 | 10,527 | 105,842 | 26,442 | 132,284 |

| Gasoline | 2,893 | 683 | 3,576 | 128,643 | 32,172 | 160,815 | |

| Hybrid | 645 | 193 | 838 | 9,545 | 2,310 | 11,855 | |

| LPG | 56 | 14 | 70 | 1,596 | 401 | 1,997 | |

| Others* | 240 | 60 | 300 | ||||

| Gearbox | Automatic | 7,469 | 1,876 | 9,345 | 127,071 | 31,828 | 158,899 |

| Manual | 4,570 | 1,096 | 5,666 | 11,8795 | 29,557 | 148,352 | |

| Engine capacity | <1000 | 508 | 106 | 614 | 22,257 | 5,543 | 27,800 |

| 1000-2000 | 8,743 | 2,183 | 10,926 | 175,479 | 43,902 | 219,381 | |

| 2000-3000 | 2,623 | 642 | 3,265 | 39,488 | 9,780 | 49,268 | |

| 3000+ | 165 | 41 | 206 | 8,642 | 2,160 | 10,802 | |

| Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Add-on | Count | Add-on | Count |

| ABS | 13,626 | ABS | 300,662 |

| ESP | 13,494 | Power steering | 296,909 |

| Electric windows | 13,428 | Central locking | 295,256 |

| Radio | 12,933 | Electric windows | 293,416 |

| Driver airbag | 12,555 | Electric side mirror | 284,564 |

| Passenger airbag | 12,531 | ESP | 283,250 |

| Side airbag | 12,082 | Isofix | 263,770 |

| Heated exterior mirrors | 12,037 | On-board computer | 258,794 |

| Leather steering wheel | 11,986 | Alloy wheels | 248,468 |

| Isofix | 11,643 | Electric immobilizer | 247,690 |

| Feature | Representation |

|---|---|

| Brand, Model, Gearbox, fuel, transmission, shape, color | Categorical features, represented with an integer as ID |

| Year of manufacture, mileage, engine power, engine capacity | Numerical features, scaled with Z-score in (0, 1) interval |

| Addons | List of categorical features, handled differently based on the approach |

| Images | .jpg file, converted into a 3D array |

| Price | Numerical feature, scaled differently based on the approach |

| Method | Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | MAE | MedE | R2 | MAE | MedE | |

| XGBoost | 0.92 | 2,965 | 1,613 | 0.91 | 3,102 | 1,772 |

| NN with add-ons projection | 0.95 | 2,463 | 1,391 | 0.94 | 2,050 | 1,236 |

| NN with add-ons embedding | 0.96 | 2,234 | 1,298 | 0.95 | 2,018 | 1,220 |

| NN with self attention on add-ons embedding | 0.96 | 2230 | 1296 | 0.95 | 2,012 | 1,214 |

| EfficientNet for image analysis and self attention on add-ons embedding | 0.96 | 2,369 | 1,350 | 0.95 | 2,030 | 1,231 |

| Swin Transformer for image analysis and self-attention on add-ons embedding | 0.96 | 2,462 | 1,533 | 0.95 | 2,116 | 1,233 |

| Model structure | Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best architecture without: | R2 | MAE | MedE | R2 | MAE | MedE |

| - | 0.96 | 2,230 | 1,296 | 0.95 | 2,012 | 1,214 |

| Year of manufacture | 0.94 | 3,028 | 1,949 | 0.94 | 2,223 | 1,374 |

| Mileage | 0.95 | 2,723 | 1,600 | 0.93 | 2,481 | 1,589 |

| Engine power | 0.96 | 2,342 | 1,354 | 0.94 | 2,077 | 1,249 |

| Engine capacity | 0.96 | 2,251 | 1,342 | 0.95 | 2,004 | 1,203 |

| Addons | 0.96 | 2,401 | 1,401 | 0.93 | 2,264 | 1,370 |

| Fuel | 0.96 | 2,278 | 1,336 | 0.95 | 2,007 | 1,200 |

| Transmission | 0.96 | 2,243 | 1,337 | 0.95 | 2,018 | 1,221 |

| Gearbox | 0.96 | 2,270 | 1,331 | 0.94 | 2,046 | 1,248 |

| Car shape | 0.96 | 2,271 | 1,315 | 0.94 | 2,051 | 1,218 |

| Color | 0.96 | 2,299 | 1,334 | 0.95 | 2,011 | 1,202 |

| Model structure | Autovit.ro | Mobile.de | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand/Model with: | R2 | MAE | MedE | R2 | MAE | MedE |

| - | 0.57 | 8,761 | 5,697 | 0.57 | 7,015 | 5,182 |

| Year of manufacture | 0.92 | 3,444 | 1,930 | 0.87 | 3,450 | 2,240 |

| Mileage | 0.88 | 4,419 | 2,872 | 0.84 | 3,955 | 2,637 |

| Engine power | 0.72 | 6,525 | 3,559 | 0.75 | 4,958 | 3,226 |

| Engine capacity | 0.63 | 7,930 | 4,947 | 0.67 | 5,828 | 3,880 |

| Addons | 0.82 | 5,181 | 2,927 | 0.87 | 3,374 | 2,124 |

| Fuel | 0.62 | 8,010 | 5,052 | 0.61 | 6,651 | 4,852 |

| Transmission | 0.60 | 8,395 | 5,215 | 0.58 | 7,083 | 5,338 |

| Gearbox | 0.61 | 8,113 | 4,725 | 0.63 | 6,427 | 4,583 |

| Car shape | 0.59 | 8,546 | 5,476 | 0.60 | 6,804 | 4,945 |

| Color | 0.59 | 8,659 | 5,669 | 0.59 | 6,784 | 4,873 |

| Images (EfficientNet architecture) | 0.69 | 6,899 | 4,053 | 0.82 | 4,045 | 2,658 |

| Images (Transformers architecture | 0.67 | 7,534 | 4,335 | 0.82 | 4,087 | 2,697 |

| Method | Autovit.ro | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | MAE | MedE | |

| DNN for image analysis without pre-training | 0.69 | 6,899 | 4,053 |

| DNN for image analysis with pre-training and fine-tuning | 0.79 | 5,652 | 3,373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).