Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- To determine the sociodemographic profile of the study participants

- To find the prevalence of psychological morbidity among Abha citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To measure the association between the sociodemographic details, associated factors of Covid-19, and psychological effects among the Abha community.

Methodology

| Personal data | N | % | |

| Age | 19-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-65 >65 |

102 134 183 77 26 8 |

19.2% 25.3% 34.5% 14.5% 4.9% 1.5% |

| Gender | Male Female |

163 367 |

30.8% 69.2% |

| Nationality | Saudi Non-Saudi |

519 11 |

97.9% 2.1% |

| Marital status | Married Single Divorced/widow |

370 134 26 |

69.8% 25.3% 4.9% |

| Education | Less than secondary Secondary University/more |

17 100 413 |

3.2% 18.9% 77.9% |

| Level of income | <5000 5000-10000 10000-20000 >20000 |

179 138 190 23 |

33.8% 26.0% 35.8% 4.3% |

| Employment | Yes No |

322 208 |

60.8% 39.2% |

| Are you a healthcare practitioner? |

Yes No |

100 430 |

18.9% 81.1% |

Discussion

Authors Contributions

Ethical Considerations

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Last Updated Apr. 5, 2021. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html.

- Awwad F, Mohamoud M, Abonazel M. Estimating COVID-19 cases in Makkah region of Saudi Arabia: Space-time ARIMA modeling. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(4): e0250149. [CrossRef]

- Alshammari T, Altebainawi A, Alenzi K. Importance of early precautionary actions in avoiding the spread of COVID-19: Saudi Arabia as an example. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal.2020;28:898-902. [CrossRef]

- Aldarhami A, Bazaid A, Althomali O, Binsaleh N. Public perceptions and commitment to social distancing “staying-at-home” during COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of General Medicine, 2020;13: 677-686. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wu H, Meng F, Li L, Wang Y, Zhou M. Relations of COVID-19-Related Stressors and Social Support with Chinese College Students' Psychological Response During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:551315. [CrossRef]

- Hazarika M, Das S, Bhandari SS, Sharma P. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated risk factors during the initial stage among the general population in India. Open J Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2021;12(1):31-35. [CrossRef]

- Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, et al. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety, and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry 2020:10:291. [CrossRef]

- Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, Roma P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(9):3165. [CrossRef]

- Rafique N, Al Tufaif F, Alhammali W, Alalwan R, Aljaroudi A, AlFaraj F, Latif R, Ibrahim Al-Asoom L, Alsunni AA, Al Ghamdi KS, Salem AM, Yar T. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Residents of Saudi Arabia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022; 15:1221-1234. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Ahmed, A., Sharaf, A., Kawakami, N., Abdeldayem, S., & Green, J. (2017). The Arabic version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21: Cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 56-58. [CrossRef]

- Shaw T, Campbell M, Runions K, Zubrick S. Properties of the DASS-21 in an Australian community adolescent population. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2016;73(7): 879-892. [CrossRef]

- Ghazawy ER, Ewis AA, Mahfouz EM, Khalil DM, Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mohammed EF, Hassan EE, Abdel Hamid S, Ewis SA, Mohammed AES. Psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students in Egypt. Health Promot Int. 2021 Aug 30;36(4):1116-1125. [CrossRef]

- Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2): e100213. Erratum in: Gen Psychiatr. 2020 Apr 27;33(2): e100213corr1.. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Ó, Sánchez-Sánchez LC, García-Montes JM. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Confinement and Its Relationship with Meditation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(18):6642. [CrossRef]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of the Iranian general population during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102076. [CrossRef]

- Downs N, Galles E, Skehan B, Lipson SK. Be True to Our Schools-Models of Care in College Mental Health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(9):72. [CrossRef]

- Mortier P, Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Bantjes J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P. WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among First-Year College Students: Results From the WMH-ICS Project. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(4):263-273.e1. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Líbano J, Yeomans MM, Oyanedel JC. Psychometric Properties of the Emotional Exhaustion Scale (ECE) in Chilean Higher Education Students. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2022;12(1):50-60. [CrossRef]

- Acharya L, Jin L, Collins W. College life is stressful today–Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of American college health. 2018;66(7):655-664. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1451869.

- Heckman S, Lim H, Montalto C. Factors related to financial stress among college students. Journal of Financial Therapy. 2014;5(1):19–39. [CrossRef]

- Shifera N, Mesafint G, Sayih A, Yilak G, Molla A, Yosef T, Matiyas R. The Psychological Impacts During the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Outbreak, and its Associated Factors Among Pastoral Community in West Omo Zone, South-West Ethiopia, 2020: A Community-Based Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:835-846. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1729. [CrossRef]

- Alkhamees AA, Alrashed SA, Alzunaydi AA, Almohimeed AS, Aljohani MS. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;102:152192. [CrossRef]

- Fu W, Wang C, Zou L., et al. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:225. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, López-Núñez M, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Choo F, Ho R, Ho C, Aparicio García M The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Health in China and Spain: Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Form Res 2021;5(5):e27818 URL: https://formative.jmir.org/2021/5/e27818. [CrossRef]

- Salman M, Asif N, Mustafa ZU, Khan TM, Shehzadi N, Tahir H, Raza MH, Khan MT, Hussain K, Khan YH, Butt MH, Mallhi TH. Psychological Impairment and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Students in Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;16(3):920-926. [CrossRef]

- Yeen Huang, Ning Zhao. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2021;26:23-34. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated Psychological Problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102092. [CrossRef]

- Cai X, Hu X, Ekumi IO, Wang J, An Y, Li Z, Yuan B. Psychological Distress and Its Correlates Among COVID-19 Survivors During Early Convalescence Across Age Groups. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(10):1030-1039. [CrossRef]

- Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, Cheng ASK. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;20:148:e98. [CrossRef]

- Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental Health Strategies to Combat the Psychological Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Beyond Paranoia and Panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49(3):155-160. PMID: 32200399.

- Arafa A, Mohamed A, Saleh L, Senosy S. Psychological Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Public in Egypt. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(1):64-69. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher MW, Zvolensky MJ, Long LJ, Rogers AH, Garey L. The Impact of Covid-19 Experiences and Associated Stress on Anxiety, Depression, and Functional Impairment in American Adults. Cognit Ther Res. 2020;44(6):1043-1051. [CrossRef]

- Dai Y, Hu G, Xiong H, Qiu H, Yuan X, Yuan X. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. medRxiv preprint 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Mahbub Alam Talukder, Md. Tuhin Mia, Nashir Uddin Shaikh, Nasreen Sultana Chowdhury, Md. Ismael, Morshed Alam, Mohammad Ala Uddin. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Depressive Symptoms among Poor Urban Women: A Study in Dhaka City of Bangladesh. Research in Psychology and Behavioral Sciences. 2021;9: 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Pannucci, Christopher J, Wilkins, Edwin G MD. Identifying and Avoiding Bias in Research. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2010;126(2):619-625. |. [CrossRef]

- Lefever S, Dal M, Matthíasdóttir Á. Online data collection in academic research: Advantages and limitations. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2007;38(4): 574-582. [CrossRef]

| COVID-19 Infection | Status | Number | Percentage |

| Have you ever been infected with Covid-19? | Yes No |

276 254 |

52.1% 47.9% |

| Relative or acquaintance infected with COVID-19 | Yes No |

273 257 |

51.5% 48.5% |

| A relative or acquaintance died of COVID-19 | Yes No |

251 279 |

47.4% 52.6% |

| Have you been quarantined? | Yes No |

263 267 |

49.6% 50.4% |

| Have you received psychological support? |

Yes No |

236 294 |

44.5% 55.5% |

| Fearing exposure to COVID-19? | Yes No |

273 257 |

51.5% 48.5% |

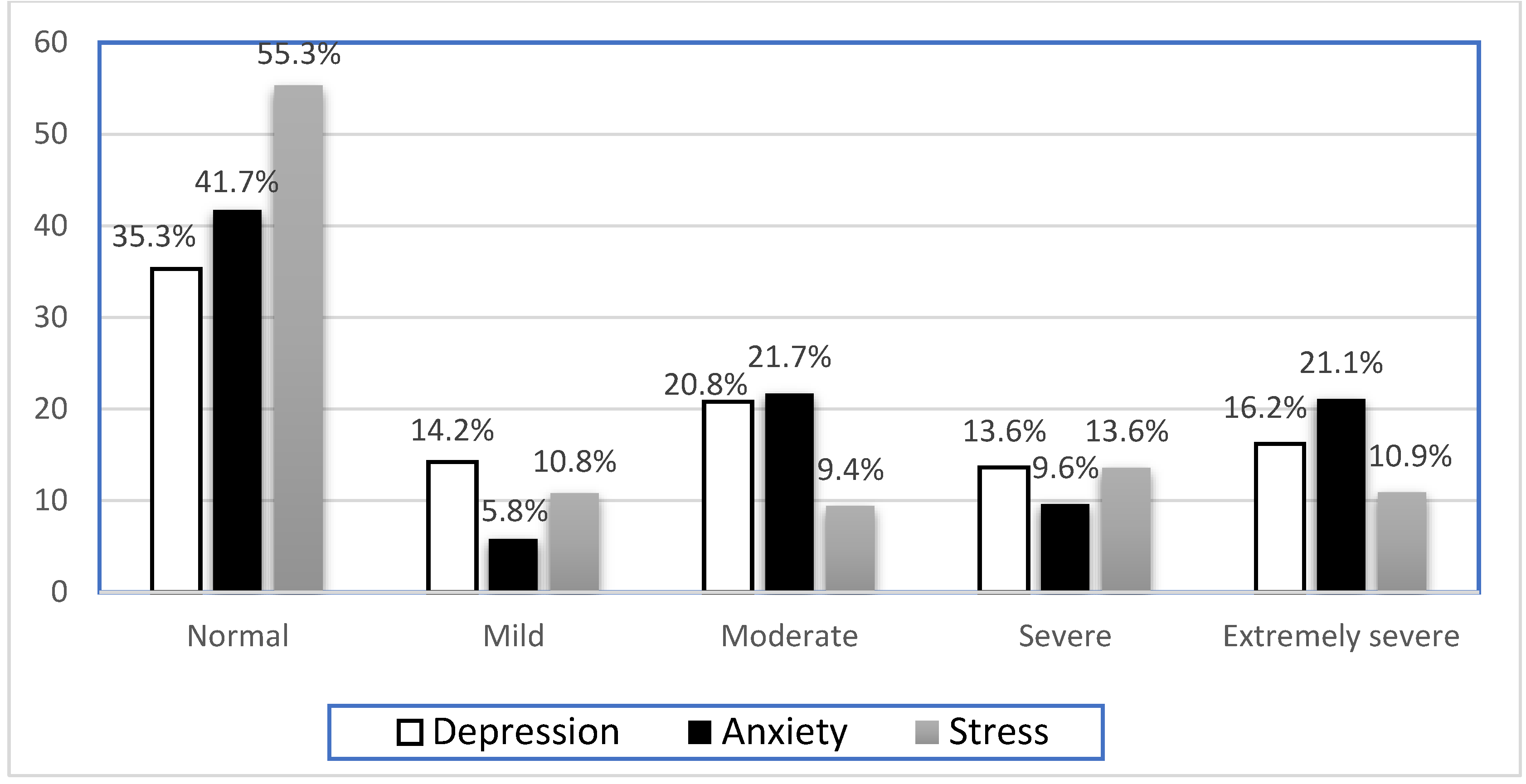

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Normal | 187 | 35.30% | 221 | 41.7 | 293 | 55.3 |

| Mild | 75 | 14.2 | 31 | 5.8 | 57 | 10.8 |

| Moderate | 110 | 20.8 | 115 | 21.7 | 50 | 9.4 |

| Severe | 72 | 13.6 | 51 | 9.6 | 72 | 13.6 |

| Extremely severe | 86 | 16.2 | 112 | 21.1 | 58 | 10.9 |

| Mean depression score (mean ± SD) | 14.84 ± 10.64 | - | 11.33 ± 10.26 | - | 15.47 ± 12.31 | - |

| Domain | Item | Did not apply to me at all. Never No % |

Applied to me to some degree or some of the time. Sometimes No % |

Applied to me to a considerable degree or a good part of the time. Often No % |

Applied to me very much most of the time. Almost Always No % |

| Depression | I could not seem to experience any positive feelings at all | 178 33.6% | 201 37.9% | 108 20.4% | 43 8.1% |

| I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things | 162 30.6% | 190 35.8% | 126 23.8% | 52 9.8% | |

| I felt that I had nothing to look forward to | 225 42.5% | 160 30.2% | 104 19.6% | 41 7.7% | |

| I felt downhearted and blue | 143 27.0% | 158 29.8% | 117 22.1% | 112 21.1% | |

| I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything | 166 31.3% | 145 27.4% | 114 21.5% | 102 19.2% | |

| I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person | 316 59.6% | 104 19.6% | 74 14.0% | 36 6.8% | |

| I felt that life was meaningless | 251 47.4% | 110 20.8% | 90 17.0% | 79 14.9% | |

| Anxiety | I was aware of the dryness of my mouth. | 226 42.6% | 165 31.1% | 83 15.7% | 56 10.6% |

| I experienced breathing difficulty | 296 55.8% | 123 23.2% | 68 12.8% | 43 8.1% | |

| I experienced trembling | 306 57.7% | 124 23.4% | 59 11.1% | 41 7.7% | |

| I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself. | 261 49.2% | 135 25.5% | 80 15.1% | 54 10.2% | |

| I felt I was close to panic | 300 56.6% | 127 24.0% | 58 10.9% | 45 8.5% | |

| I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion. | 266 50.2% | 145 27.4% | 65 12.3% | 54 10.2% | |

| I felt scared without any good reason. | 245 46.2% | 148 27.9% | 81 15.3% | 56 10.6% | |

| Stress | I found it hard to wind down | 184 34.7% | 184 34.7% | 98 18.5% | 64 12.1% |

| I tended to over-react to situations | 222 41.9% | 164 30.9% | 91 17.2% | 53 10.0% | |

| I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy | 178 33.6% | 163 30.8% | 96 18.1% | 93 17.5% | |

| I found myself getting agitated | 175 33.0% | 160 30.2% | 117 22.1% | 78 14.7% | |

| I found it difficult to relax | 189 35.7% | 160 30.3% | 87 16.4% | 94 17.7% | |

| I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing. | 204 38.5 | 172 32.5% | 85 16.0% | 69 13.0% | |

| I felt that I was rather touchy | 186 35.1% | 169 31.9% | 99 18.7% | 76 14.3% |

| Dependent variables and significantly associated variables | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Dependent variable: Depression** | ||

| Age group 19-25 years |

2.01 (1.00 – 4.04) |

0.049* |

| 26-35 years 36-45 years 46-55 years 55-65 years |

1.79 (0.83 – 3.88) 2.20 (0.90 – 5.37) 1.56 (0.50 – 4.87) 0.23 (0.00 – 0.00) |

0.139 0.045* 0.334 0.999 |

| Sex (Male) | 0.97 (0.64 - 1.49) | 0.898 |

| Nationality (Saudi) | 0.22 (0.03 - 1.91) | 0.171 |

| Marital status Married Single |

1.89 (0.81 – 4.44) 2.76 (1.00 – 7.59) |

0.143 0.050* |

| Level of education Less than secondary Secondary |

0.542 (0.17 – 1.71) 0.934 (0.55-1.58) |

0.295 0.799 |

| Level of income <5000 5000-10000 10000-20000 |

0.57 (0.33 – 1.00) 0.76 (0.42 – 1.35) 0.89 (0.33 -2.41) |

0.050* 0.346 0.820 |

| Do you work (yes) | 0.62 (0.37 – 1.04) | 0.068 |

| Dependent variable: Anxiety** | ||

| Age 19-25 years |

1.33 (0.67 – 2.62) |

0.411 |

| 26-35 years 36-45 years 46-55 years 56-65 years Sex (Male) |

0.72 (0.34 – 1.53) 1.31 (0.55 – 3.09) 1.34 (0.44 – 4.10) 2.76 (0.44 – 17.2) 0.67 (0.44 – 1.02) |

0.397 0.542 0.605 0.277 0.064 |

| Nationality (Saudi) | 0.64 (0.15 -2.74) | 0.555 |

| Marital status Married Single |

1.98 (1.09 – 3.60) 1.04 (0.44 – 2.46) |

0.025* 0.926 |

| Level of education Less than secondary Secondary |

1.39 (0.45 – 4.36) 1.32 (0.79 – 2.20) |

0.570 0.293 |

| Level of income <5000 5000-10000 10000-20000 |

1.64 (0.64 -4.17) 1.03 (0.41 – 2.60) 1.15 (0.46 – 2.89) |

0.302 0.949 0.761 |

| Do you work? | 1.32 (0.80 – 2.20) | 0.280 |

| Dependent variable: Stress** | ||

| Age 19-25 years |

1.72 (0.89 – 3.32) |

0.106 |

| 26-35 years 36-45 years 46-55 years 56-65 years Sex (Male) |

1.14 (0.54 – 2.42) 1.50 (0.64 – 3.54) 1.47 (0.49 – 4.42) 1.55 (0.30 – 7.97) 0.90 (0.59 – 1.35) |

0.725 0.350 0.492 0.600 0.594 |

| Nationality (Saudi) | 0.67 (0.18 – 2.48) | 0.553 |

| Marital status Married Single |

2.16 (1.21 – 3.83) 0.89 (0.38 – 2.09) |

0.009* 0.797 |

| Level of education Less than secondary Secondary |

1.60 (0.53 – 4.79) 1.13 (0.68 – 1.87) |

0.403 0.634 |

| Level of income <5000 5000-10000 10000-20000 |

0.59 (0.34 – 1.00) 0.85 (0.48 – 1.48) 1.19 (0.48 – 2.99) |

0.050* 0.556 0.706 |

| Do you work? | 1.13 (0.69 – 1.85) | 0.635 |

| Dependent variables and significantly associated variables | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Dependent variable: Depression** | ||

| Healthcare practitioner (Yes) |

1.89 (1.18 – 2.92) | 0.007 |

| Have you ever been infected with COVID-19? (Yes) |

1.34 (0.92 – 1.95) | 0.125 |

| Relative or acquaintance died of COVID-19 (Yes) |

0.65 (0.45 – 0.95) | 0.026* |

| Have you been quarantined? (Yes) | 1.31 (0.91 – 1.90) | 0.153 |

| Have you received psychological support (Yes) |

1.16 (0.78 – 1.71) |

0.472 |

| Fearing exposure to COVID-19 (Yes) | 1.26 (0.86 – 1.83) | 0.234 |

| Dependent variable: Anxiety** | ||

| Healthcare practitioner (Yes) | 1.27 (0.81 – 1.98) | 0.293 |

| Have you ever been infected with COVID-19 (Yes) | 1.01 (0.70 – 1.44) | 0.956 |

| Relative or acquaintance died of COVID-19 (Yes) |

0.81 (0.56 – 1.16) |

0.249 |

| Have you been quarantined? (Yes) | 0.97 (0.68 – 1.38) | 0.873 |

| Have you received psychological support (Yes) |

0.90 (0.62 – 1.31) |

0.577 |

| Fearing exposure to COVID-19? (Yes) | 1.46 (1.02 – 2.09) | 0.039* |

| Dependent variable: Stress** | ||

| Healthcare practitioner (Yes) | 0.92 (0.59 – 1.43) | 0.697 |

| Have you ever been infected with COVID-19 (Yes) |

0.78 (0.55 – 1.11) |

0.171 |

| Relative or acquaintance died of COVID-19 (Yes) |

1.03 (0.72 – 1.47) |

0.875 |

| Have you been quarantined? (Yes) | 0.84 (0.59 – 1.19) | 0.331 |

| Have you received psychological support (yes) | 0.93 (0.64 – 1.35) | 0.697 |

| Fearing exposure to COVID-19 (Yes) | 0.75 (0.52 – 1.07) | 0.107 |

| OR – Odds ratio CI’s – Confidence interval Bolded OR & CI’s: p-value ≤0.05. **– depression >9, Anxiety >7 and stress >14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).