1. Introduction

Widespread acceptance of electromobility is highly dependent on the performance and service life of the battery technology used. Lithium-ion batteries (LIB) are currently the most promising energy storage technology for mobile applications available, but cell performance and capacity are greatly affected by environmental conditions, especially temperature [1]. Winter temperatures reduce the energy efficiency and practical energy availability of lithium-ion battery packs by up to 30%. The charging characteristics of many lithium-ion technologies generally do not allow discharging at excessively high temperatures. In addition, freezing temperatures often prevent charging. By maintaining a defined temperature range of at least 15 °C up to 30 °C, these drawbacks can be greatly reduced and even eliminated [1]. With this technology, battery temperature becomes a key parameter for battery performance. Also, batteries generate a lot of heat during charging and discharging and must be dissipated by proper cooling. Heating is also required when the vehicle is operated in cold temperatures. The possibility of storing thermal energy in battery packs is being explored for more efficient use of energy. The advantage of storing waste heat in the battery system lies in user behavior and the system-related fact that the vehicle is not always connected to a charging station in order to generate the energy to heat the battery pack. Maintaining a traction battery temperature window not only optimizes performance and storage capacity, but also reduces the load on the battery cells, which has a positive effect on service life. This reduces the total energy consumption of electric vehicles in their lifecycle from production to recycling. This alleviates the weaknesses of LIB, which are reduced performance and storage capacity at low temperatures. Phase change materials (PCM) offer the potential to store thermal energy with high energy densities. Our goal was therefore to integrate such a PCM into the battery box. The manufacturing options examined are metal 3D printing. This field of additive manufacturing technology makes it possible to produce parts that could not be manufactured in the past. This makes it possible for the first time to optimally implement an innovative heat transfer system inside the battery pack. The new system can keep all battery cells at a uniform temperature throughout the battery pack. The purpose of thermal management is to keep the inside of the box within a defined temperature window to ensure safe, long-lasting and efficient operation of the battery cells.

2. Materials and Methods

The system components of the BTMS have been identified and found to be suitable candidates for energy efficient energy storage systems for electric vehicles. LIB thermal parameters are defined. Based on the parameters of the battery cells used, a suitable PCM was defined and its suitability was tested in laboratory experiments. To verify the properties of PCMs, we have developed our own test bench that can automatically measure different his PCMs simultaneously. Furthermore, PCM can be observed over longer periods of time. The developed PCM test stand has a mobile and modular design, allowing the specimen to be exchanged and the heat accumulator to be expanded. The exact procedures and components used for this test bench were developed in a preliminary project and detailed in the accompanying report [2]. Particular attention was paid to additive manufacturing options when designing the battery pack. Aspects such as component geometry, component thickness, overhangs and supports, post-processing processes, material selection, and manufacturing costs must be considered. A CFD model was created and simulated to describe the thermal behavior of a battery system with cooling or heating integrated with PCM storage. This simulation can be used to test different scenarios and explore the thermal behavior of components under different conditions, such as different temperatures and load conditions.

2.1. PCM Enhanced Battery Packs

For thermal management of electric vehicles, common heat dissipation techniques including forced air cooling and liquid cooling are frequently employed. Such BTMS first seem to be highly effective, but they often increase the overall system's weight and parasitic power requirements by adding extra blowers, fans, pumps, pipes, and other accessories that are large, expensive, and complex [3]. These cooling system limitations, the increased energy consumption of parasitic loads, and the limited battery capacity can all be avoided by using a well-designed and optimized PCM system [4]. Many advantages could result from a novel thermal management approach that uses PCM as a heat dissipation source. A compact, cost-effective, and warp-resistant system without ancillary performance requirements ought to be the primary benefit of such a heat management system [4].

2.1.1. Phase Change Material

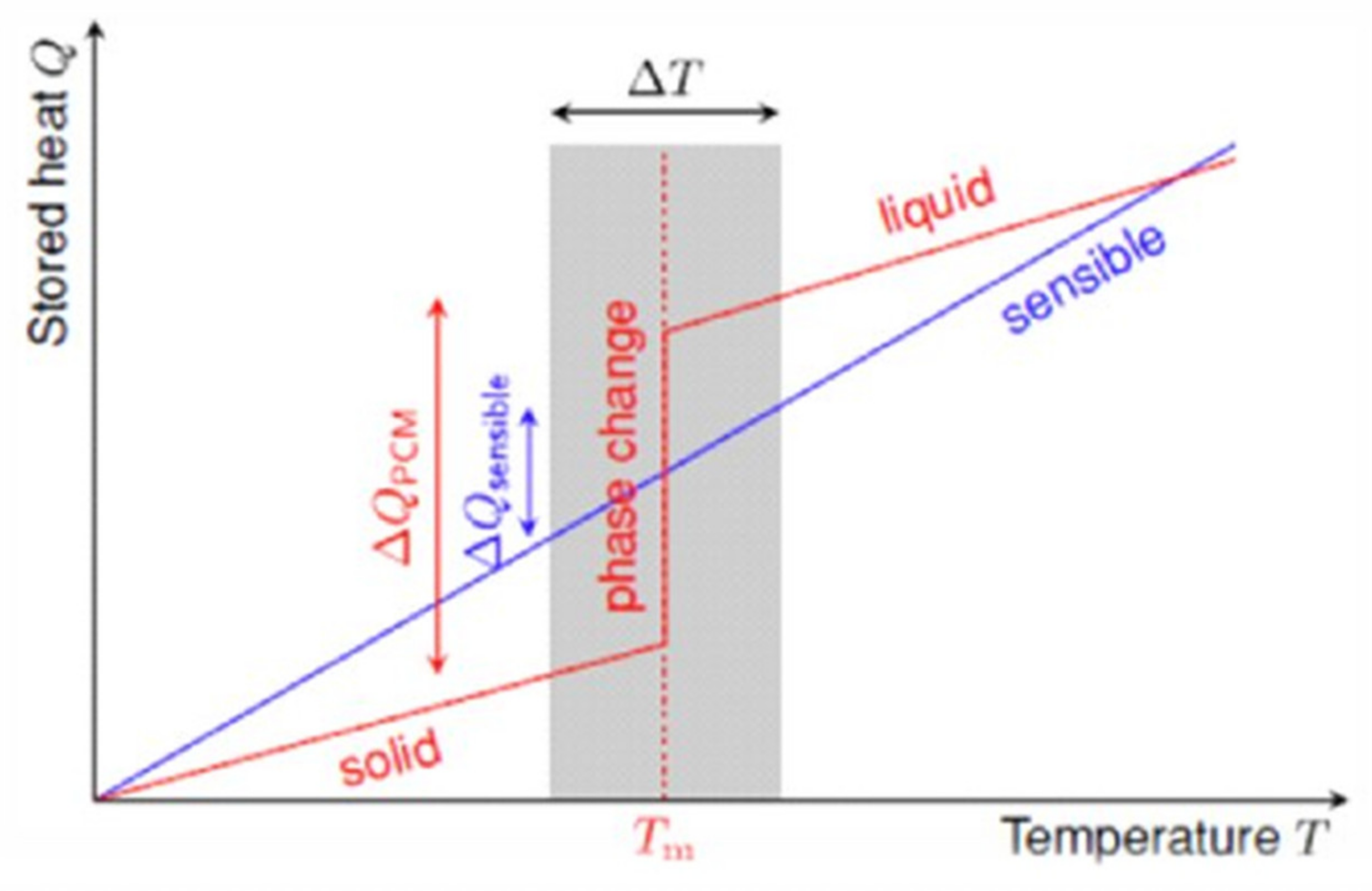

Heat is stored in sensitive heat storage materials by the temperature difference between the storage medium before and after the charging process. Temperature difference, heat capacity, and storage medium mass all play a role in the amount of energy stored. Sensitive heat storage systems, which can be found in almost every household as a warmwater tank and a buffer storage, require good heat insulation.

PCM – heat storage systems are also known as latent heat storage because the heat is stored more "latently" than "sensible" in a PCM. The charging and discharging are accomplished by changing the aggregate state of the medium based on its respective enthalpy. These systems can store heat relatively lossless over long periods of time.

Figure 1 depicts the distinction between sensible and latent heat storage. The benefit of larger energy storage amount is limited to a certain temperature area. The solid-liquid phase transition and vice versa is the most widely employed principle. Special salts or paraffin are frequently melted as a storage medium for charging the storage, as they absorb a lot of thermal energy. The discharge happens as the storage medium solidifies, releasing the previously absorbed massive amount of heat back into the environment as solidification heat. The amount of heat depends not only on the system's temperature difference, but also on the material's mass and specific heat capacity.

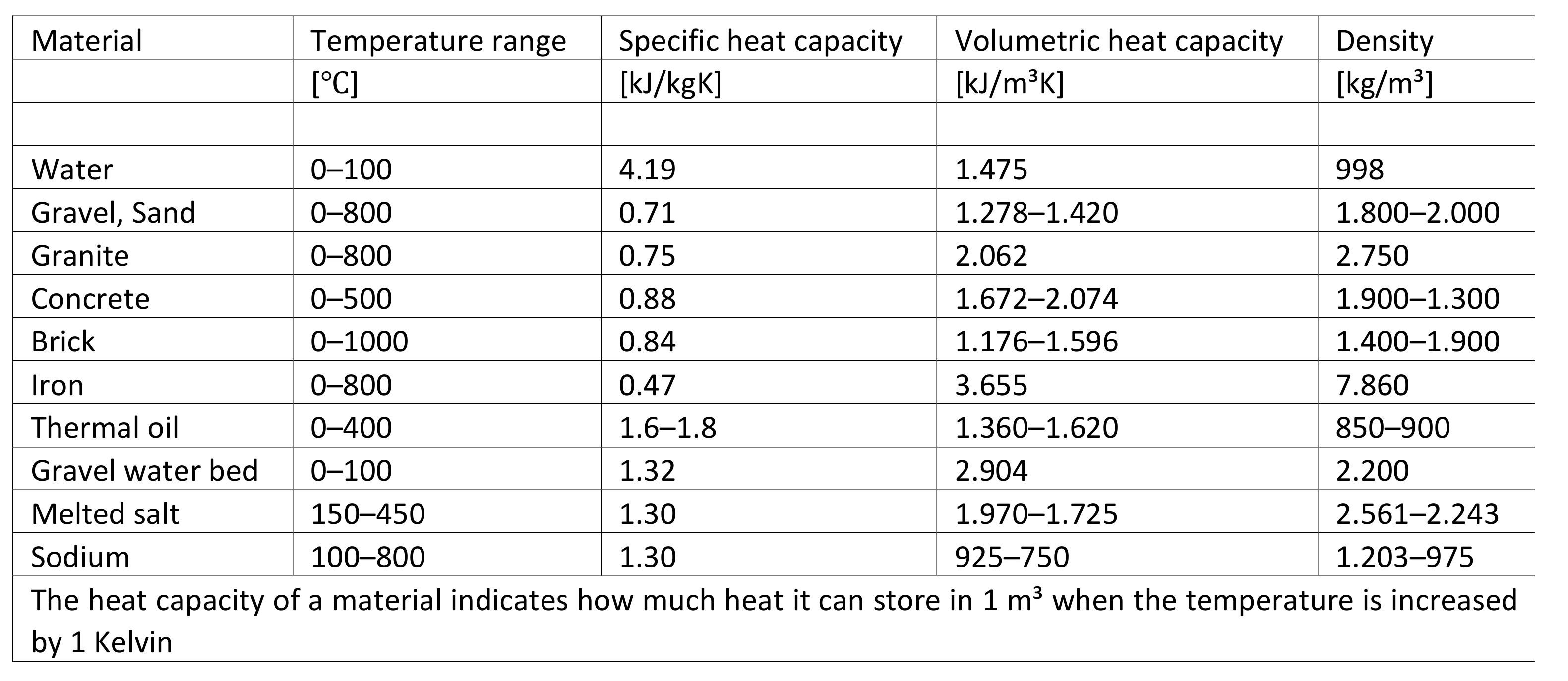

Table 1 shows the specific heat capacities of some substances. Since mass is not the only determinant of energy storage, consistency and volumetric heat capacity are often also specified. The heat capacity of a material indicates how much heat it can store in 1 m³ when the temperature is increased by 1 Kelvin [

5].

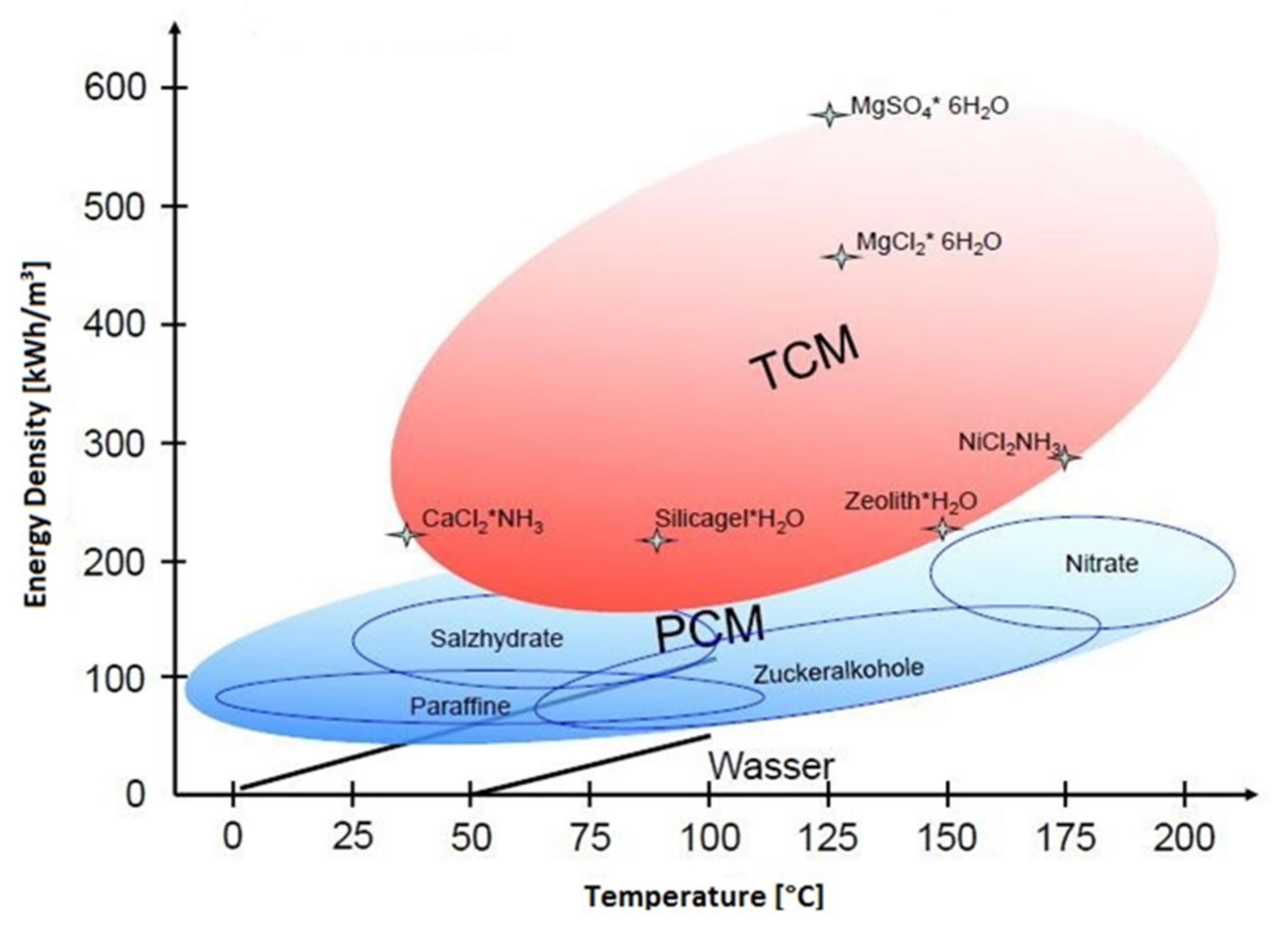

Different material classes are used as latent heat storage, depending on the temperature range. Solid-liquid transition is mainly used because the volume change is easier to handle than solid-liquid transition and the enthalpy of the transition is sufficiently high compared to solid-liquid transition. The longest and most commonly used PCM is water or ice. It meets all the required standards and is very cheap and available everywhere. In addition to water, the substance classes salt hydrates and paraffins are most frequently used [6]. Therefore, the application determines the storage medium with the optimum phase transition temperature. Water and salt solutions are primarily used for refrigerated storage. There are various materials that are suitable for phase change heat storage. In practice, solid-to-liquid transitions are mostly used. A phase change from liquid to gas is avoided despite the high phase transition enthalpy due to the large change in volume [5]. Use salt hydrate or paraffin at 5°C to 130°C for heat storage. Salts such as nitrates, chlorides, carbonates and fluorides are mainly used for heat storage above 130 °C, but mixtures of these substances are also used at these temperatures. The use of salt hydrates as PCMs results in so-called "discordant melting" [7], which affects the reversibility of the phase change process and thus reduces the heat storage capacity of the medium. By adding suitable additives to salt hydrates in pure form, it is possible to counteract the phenomenon of incompatible melting and use the medium in a temperature range around 100 °C [7]. The paraffin-based PCMs are characterized by being particularly harmoniously soluble, cycle-resistant, ecologically harmless, harmless to health and not corroding metal building materials [6]. Special attention should be paid to the phase change temperature, as it is the most important criterion in selecting a PCM for a particular application. No single material has all the properties needed for an ideal PCM. Therefore, available materials must be selected and additional additives added to replace poor physical properties with suitable system designs [7]. The selection of suitable PCMs for passive BTMS was determined by the materials available on the market and the phase transition temperature chosen.

2.1.2. PCM Preselection

The preset battery technology defines an ideal temperature range for continuous battery operation between 15°C and 30°C.

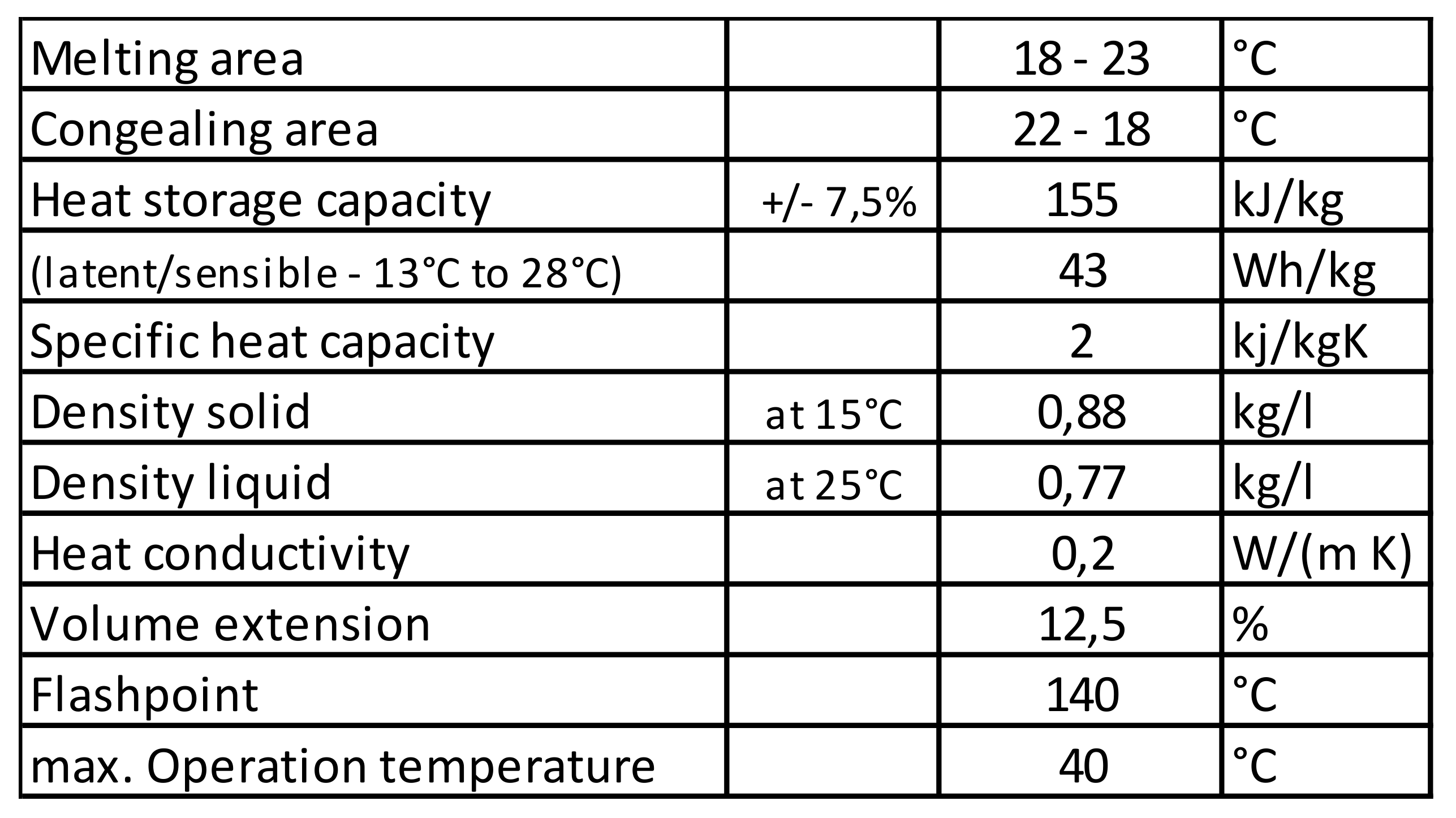

Figure 2 shows that only paraffins are in question for this temperature range. For these reasons, paraffin RT21 is the best choice for our application. This material's highest heat storage capacity is attained at temperatures ranging from 13°C to 28°C. Heat is stored in this area as a combination of latent and sensible heat.

This material has a heat storage capacity of 43 Wh/kg in the given temperature range, as shown in the accompanying data sheet in. In order to store the entire energy content of a battery cell as thermal energy in the PCM, we need 0.20 kg of paraffin RT21 per battery cell [9].

2.2. Metal 3D Printing

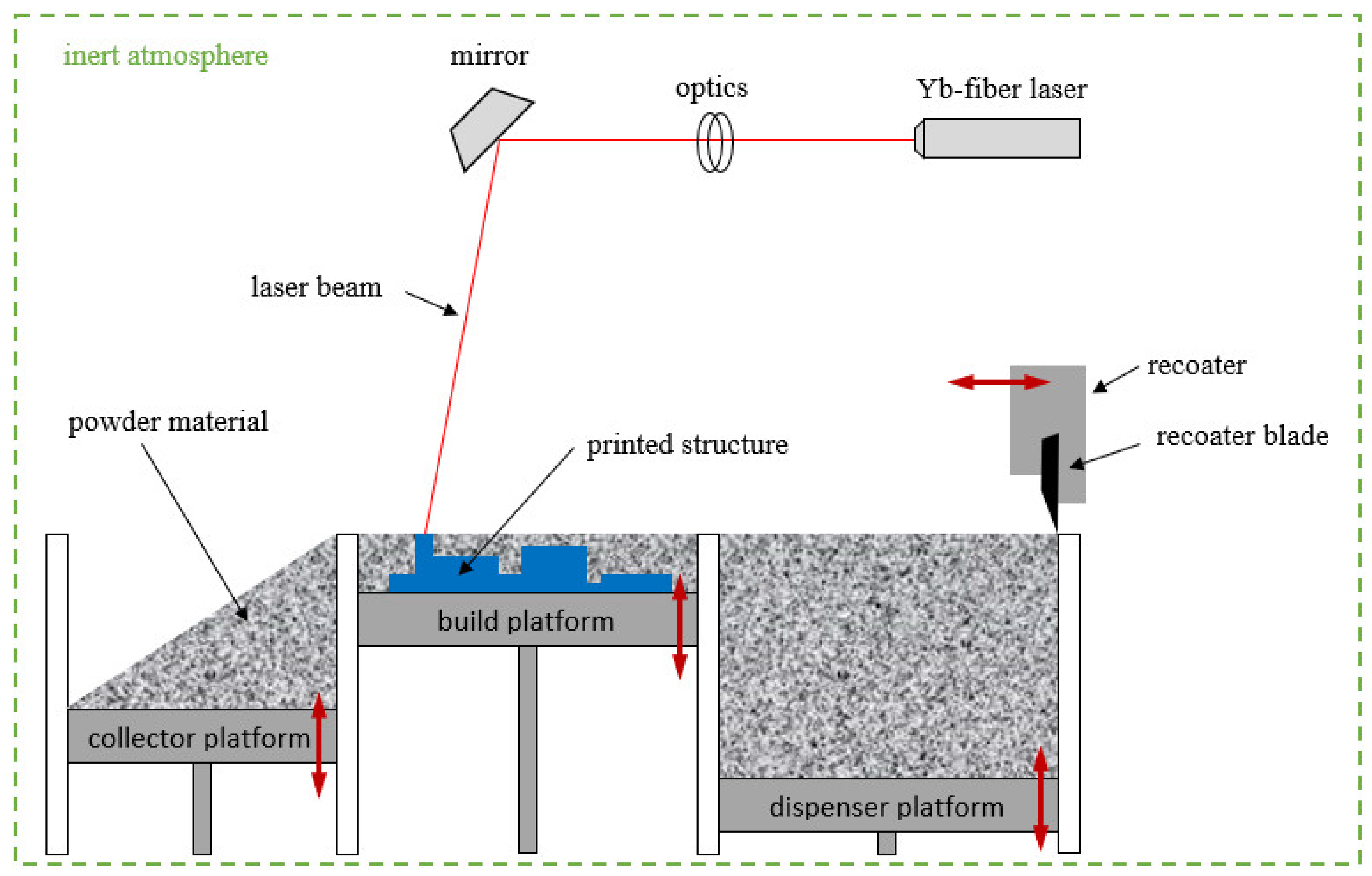

A temperature management system with an implemented cooling circuit requires a manufacturing process that enables the fabrication of complex and fragile structures. Furthermore, a heat resistant material is required to withstand temperature fluctuations within or around the system. Therefore, Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) is selected to be a suitable manufacturing technology for this application. DMLS is an additive manufacturing technology for fabricating metal components out of powder particles – it is assigned to the Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) technology.

The DMLS printing system consists of three different chambers as schematically shown in Table 2. These chambers are flooded with inert gas (Nitrogen/Argon – depending on the powder material) to create an oxygen-free atmosphere during the printing process. There is one movable platform in each of the chambers. First, powder material (new/recycled) is filled on the dispenser platform. Here, the powder material has to be manually compacted with the help of spatulas to avoid cavities that could lead to problems during the print job. Then, the recoater arm including the recoater blade moves across all the three platforms, starting on the right (dispenser platform). Here, the recoater blade (steel, ceremic, or soft brush – depending on the powder material and on the geometry) takes away a certain amount of powder material which is then applied on the build platform. The excessive powder material is pushed onto the collector platform. After the first layer of powder material is applied, a high power Yb-fiber laser beam fuses together the single powder particles according to a two-dimensional section of the CAD model. Splashes, which are created by the laser beam, are blown away by a continuous gas flow across the build platform. After the powder layer is exposed, the next powder layer is applied by the recoater arm. This iterative process lasts until the structure to be printed is finished [10–14].

Table 2.

Data sheet RT21 [8].

Table 2.

Data sheet RT21 [8].

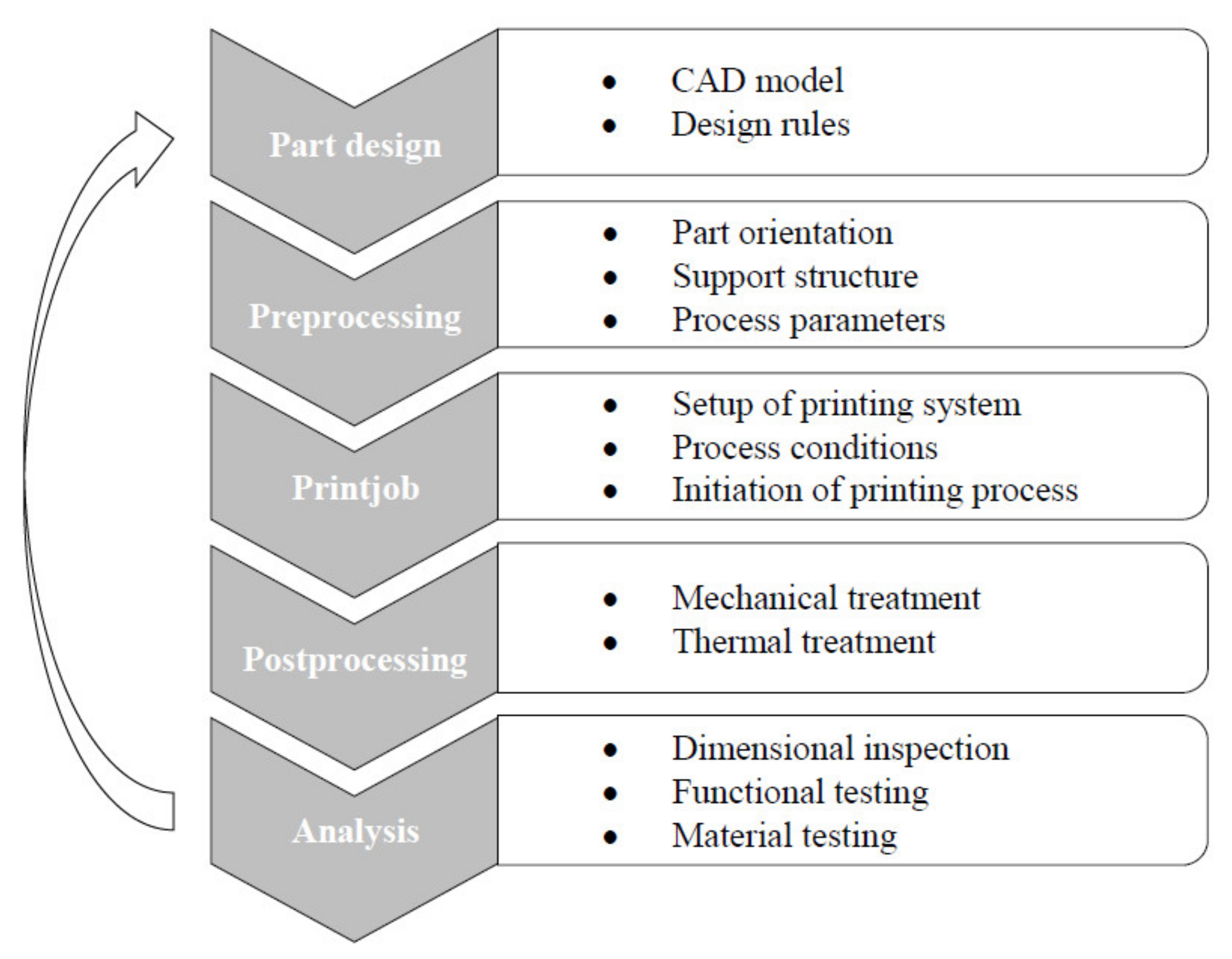

Due to the high process complexity of DMLS, the number of influencing factors (e.g. direction of the gas flow and the direction/movement of the recoater arm) that can have a significant impact on the buildability, the quality, and also the process costs of a part is very high. To keep the risk of a negative impact of the influencing factors low, the overall printing process including its single steps has to be considered, as shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Principle of DMLS printing system [15] (p. 74).

Figure 3.

Principle of DMLS printing system [15] (p. 74).

The first step of the printing process is the “Part design”. Here, the 3D-model of the part is created by using a CAD software (e.g. Autodesk® Inventor®) under consideration of process and material dependent design guidelines. These design guidelines contain relevant information about geometric restrictions (e.g. maximum pin diameter, minimum wall thickness). A thoughtful design can help to save support structure and therefore to reduce the process costs. At the end of the part design, the 3D-model is transferred into a STL file.

The second step is called “Preprocessing”. In this step, the STL file is loaded into a software that represents a virtual build platform (e.g. Materialise Magics®). Here, the orientation of the part is defined and support structure is generated. The orientation of a part has an enormous influence on the part quality and on the process costs (e.g. build height). After this step, the STL files (part and support structure) are transferred into a slicing software (e.g. EOSPRINT®). Within the slicing software, the 3D models of the STL files are subdivided into 2D-sections (slices). This step is necessary because the printing system then processes one slice after the other during the process (powder recoating/exposing). Furthermore, the appropriate printing parameter has to be selected within the slicing software. Every powder material requires a certain printing parameter that guarantees a parts’ maximum density and strength. Nevertheless, depending on the application and the part geometry, it is also possible to change some of the process parameters (e.g. laser power, laser speed, hatch distance) to avoid problems (e.g. warpage). Right after the preprocessing step is finished, the virtual print job is sent to the printing system.

Within the third step, which represents the “Print job”, the printing system is prepared for the upcoming process. This step includes the setup of the printing system (filling of powder material, application of the first powder layer, cleaning of the lens, etc.) and the initiation of the process conditions (e.g. flooding of system chamber with inert gas, heating of build platform). Subsequently, the print job can be started. When the print job is finished, the excessive powder material is removed and the build platform including the printed structures is taken out of the printer.

The fourth step is the “Postprocessing”. Here, the parts are removed from the build platform using diverse techniques (e.g. hammer and chisel, band saw, hand saw, wire cutting). Furthermore, mechanical (e.g. turning, milling) and thermal treatments (e.g. hardening) are executed within this step. In general, parts fabricated via DMLS can be treated with all kinds of manufacturing processes, same as conventional parts.

The fifth step of the process represents the “Analysis”. Dimensional inspection, functional testing, and material testing are part of this step.

The process steps of

Figure 4 have a mutual influence which is linked to the final result of a print job. Technical aspects (buildability) and the economic aspects (process costs) depend on the optimum correlation between the single process steps. Therefore, it can happen that the entire development process has to undergo several iterations until the result is at its optimum.

2.2. Special Aspects of Component Design

In order to accommodate the entire energy of the LIB in the PCM, 0.20 kg of paraffin RT21 per battery cell would be necessary. Since the battery concept provides for additional external heating or cooling and in order to be able to settle the size and weight of the battery pack in a normal range, we decided to reduce the amount of thermal storage mass to 0.05 kg/cell. Furthermore, the aspects of the component design depend on the appropriate printing system. In our case, we decided to use the EOS M400 printing system. The aspects are:

Minimum wall thickness: 0.4 mm

Minimum cavities: 0.8mm

Minimum distance from wall to wall: 0.4mm

Minimum angle for overhangs: 45°

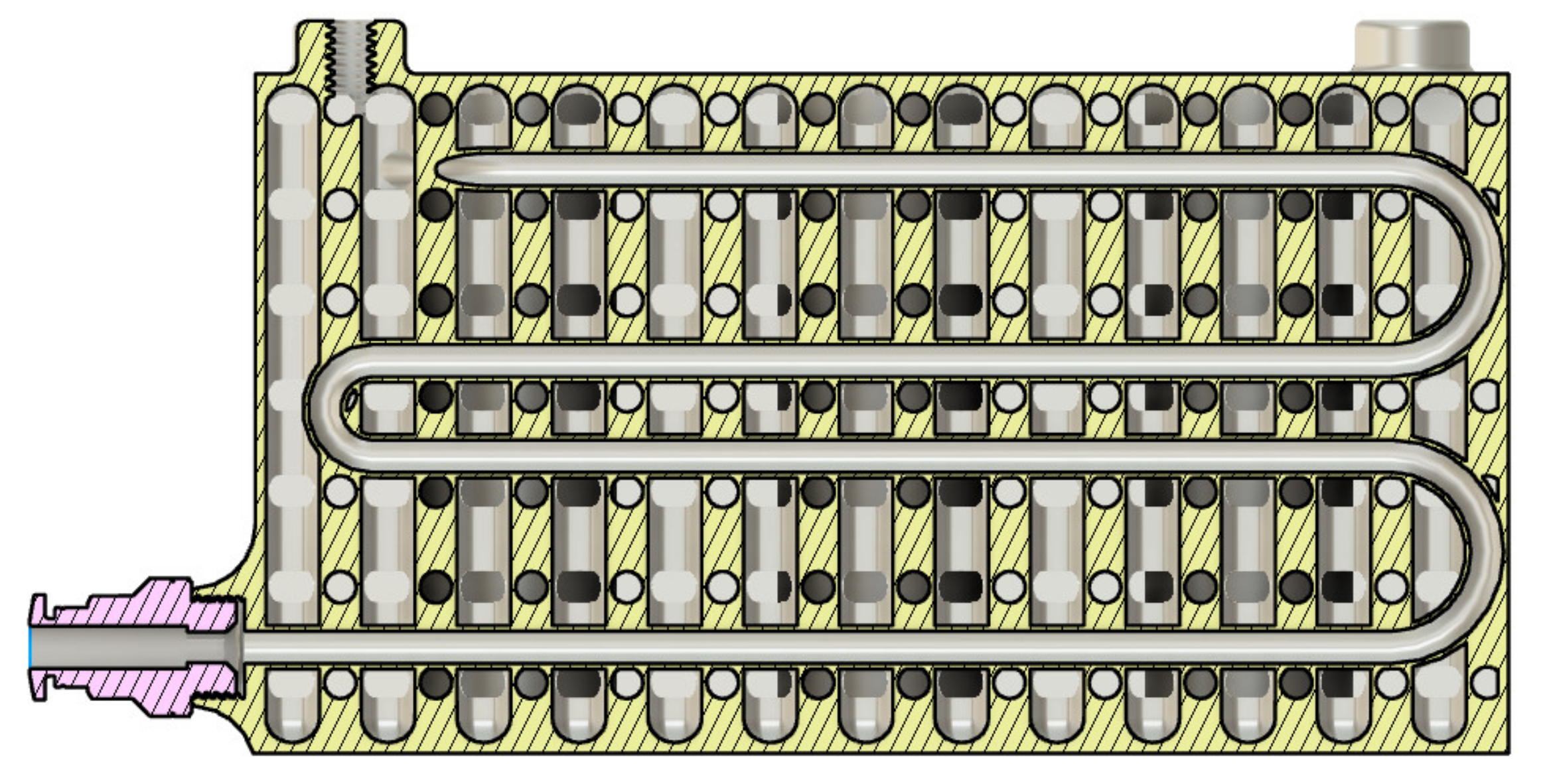

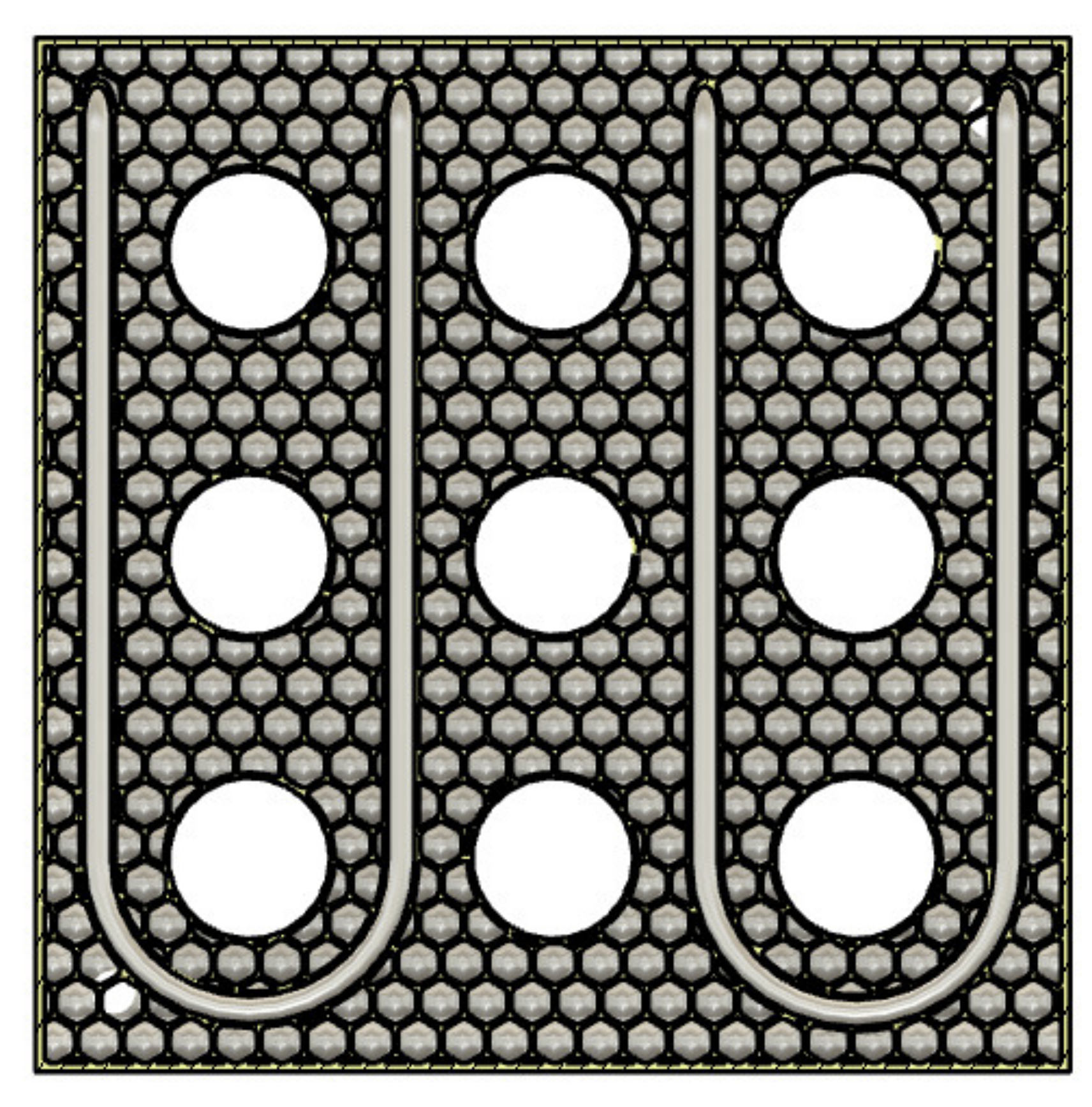

The thickness of the walls in the construction is between 0.5 – 2 mm. The diameter of the pipes is 3.1 mm. The distance between the edge of the honeycomb is 4 mm. Inside the box we have designed a honeycomb structure. The upper and lower part of each honeycomb is a hemisphere so that we do not need any additional support structures inside.

2.4. Design, Modeling and Simulation

To assess the feasibility and functionality of BTMS, we decided to support the development process with simulations. In today's industry, simulation is an everyday tool, especially in companies with strong engineering ties, such as the automotive industry or mechanical and plant engineering. Therefore, in science as well as in business, there is a strong demand for ways to utilize computers to provide competitive and functional products, and to manufacture and sell them efficiently, with high quality and safety. [27] Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a computational mathematical modeling tool that can be viewed as a fusion of theory and experiment in the fields of fluid flow and heat transfer. CFD simulations provide information about flow and fluid properties that can be difficult or expensive to obtain by measurement, providing insight and understanding of product performance or flow behavior in specific situations. CFD is now used in many industries, starting from aerospace and power generation, to consumer goods, biomedical, pharmaceutical, built environment and many more. Where CFD has historically been used to predict or understand the flow performance of existing designs or conditions. The most effective and productive usage is achieved when applied early in the design process to drive the design towards better or more consistent performance. [28] Even the simplest heat exchange system is actually quite complex when viewed through rigorous analysis. Therefore, we decided to perform flow analysis in BTMS using a computational fluid dynamics software tool that offers 3D flow analysis. CFD is a software tool for simulating the behavior of systems involving fluid flow, heat transfer, and other similar physical processes. Solve fluid flow equations over a defined range. I need to know the conditions specified at the boundaries of this region. Creating such CFD models and analyzing the results is quick and easy thanks to high computational power, powerful graphics and interactive 3D manipulation of the models. Advanced solvers contain algorithms that provide robust solutions to flow fields in a reasonable amount of time. For these reasons, CFD is now an established industrial design tool that offers a cost-effective and accurate alternative to scale model testing. There are many different solving methods used in CFD codes, but the most common is known as the finite volume method. In this technique, the region of interest is divided into smaller sub-regions called control volumes. The equations are discretized and solved iteratively for each control volume. As a result, you can get an approximation of the value of each variable at a specific point over the range, giving you a complete picture of the flow behavior. Estimating the heat release of solids due to convection can only be done by abstracting the body under consideration into very simple geometries. However, these empirical approximations lose their meaning when the geometry of the body and the abstraction deviate significantly. Heat sources with very complex geometries cannot be meaningfully represented by abstractions. Calculation of heating power can be mastered only under very simple conditions. To be able to describe the thermal behavior of battery systems with passive PCM cooling, his CFD model of the battery and surrounding thermal mass was created. The CFD tool Ansys/Fluent was used for this. [28] Passive BTMS requires the heat generated in the battery cells of the battery pack to be transferred to the PCM. The resulting heat is stored in the PCM, which should provide the ideal temperature range for the battery cells.

In Chapter 2.2, we explain how we can build a structure so that we don't need a support structure provided by the slicer. The other two critical points are cooling or heating and PCM space. We design pipes inside the structure for cooling and heating. The honeycomb construction also serves as a support framework for the tubes (see

Figure 5). To guarantee that the PCM is distributed evenly, we punctured the honeycomb (

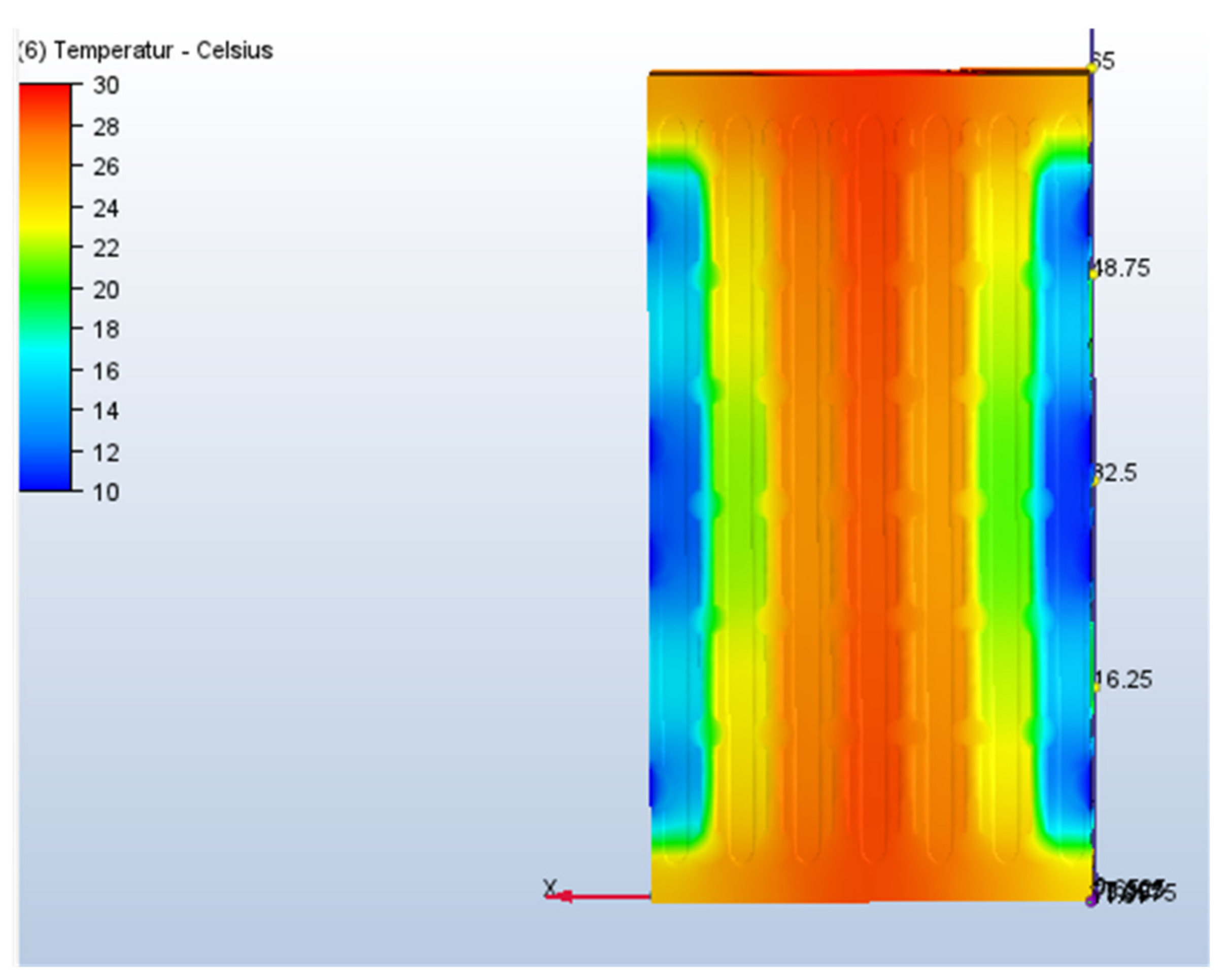

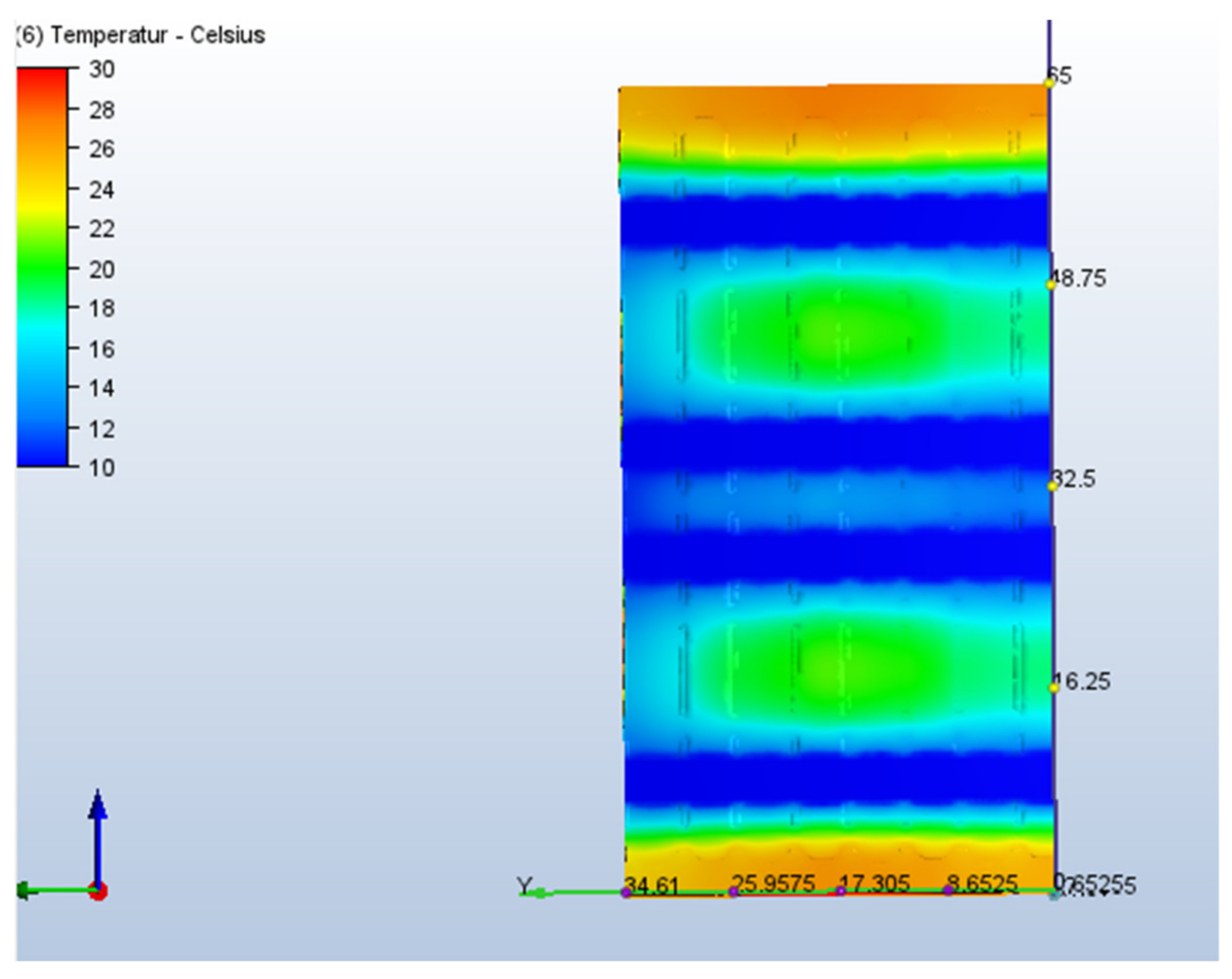

Figure 5). The middle section of the construction was simulated in Autodesk CFD 2023 to generate preliminary estimations of the temperature distribution. The battery slot's wall temperature was anticipated to be 30°C. The liquid passing through was supposed to be 10°C in temperature. To provide a better idea of the temperature distribution, the temperature difference was considered to be 20°C.

Figure 5.

The side cut-out shows the hemisphere from the upper and lower part.

Figure 5.

The side cut-out shows the hemisphere from the upper and lower part.

Figure 6.

Honeycomb structure inside.

Figure 6.

Honeycomb structure inside.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution front view.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution front view.

As can be seen in Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the temperature distribution between the front view and the side view is very different. In order to achieve an even temperature distribution, an additional cooling loop must be installed in the next step, offset by 90 degrees.

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution Side view.

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution Side view.

3. Results

In this project, the feasibility and effectiveness of passive thermal management of lithium-ion batteries using phase change materials for electric vehicle battery modules was investigated. We were able to evaluate different latent heat storage materials and define suitable PCM for the required temperature range of the selected battery cells. The strong temperature dependence of the performance of lithium-ion battery packs can be mitigated by installing a high energy density heat accumulator such as PCM. Based on the battery pack's selected batteries and the data from the PCMs, paraffin RT21 appears to be the best fit for this application. This material's highest heat storage capability is attained at temperatures ranging from 13°C to 28°C. It is feasible to assume that the best temperature range for our batteries' continuous operation should be between 15°C and 30°C. This condition is met by using paraffin RT21. A first, printable concept with sufficient heat conduction in the material and an integrated heating and cooling concept could be developed. Several iteration loops regarding the design and thermal simulations were necessary in order to reach proper results. The component design was made according to design guidelines for DMLS. In the scope of this work, we only focused on the design and simulation of the battery pack. The results show the fabrication of a 3D-printed battery pack is possible although the component was not printed yet. The printing and practical evaluation of the battery pack is part of a subsequent project.

4. Discussion

The input of heat energy into the system from the outside "Battery to PCM" can create a uniform temperature distribution within the battery pack. The strong temperature dependence of lithium-ion battery pack performance can be mitigated by adding a high energy density heat accumulator such as our His PCM. Due to the poor heat transfer of PCMs, additive manufacturing options can be used to integrate additional cooling for safe operation of the battery in the event of overheating. Implementing his PCM in a vehicle battery increases the total weight of the battery, which in turn increases the total weight of the vehicle, thus increasing energy consumption. To avoid this, the whole system was constantly observed during the study to focus on suitable solutions. PCMs that meet the requirements are not widely available on the market, which can lead to higher battery pack costs. In this exploratory project, this risk is subordinated to the technical risk as the economic valuation is dubious. The design of the battery pack has to include both, thermal simulation as well as the consideration of process-dependent design guideline to ensure an optimal thermal behavior as well as the printability of the complex structure. The printing of the structure and its validation in practical experiment is executed in future projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.; methodology, S.T., J.Z. and D.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, P.N.; investigation, S.T., J.Z. and D.Z.; resources, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T., J.Z. and D.Z.; supervision, R.H. and R.L.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- T. Reddy and D. Linden, Linden´s Handbook of Batteries, Fourth Edition, McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2011.

- S. Thaler, "Effizienzsteigerung von thermischen Solaranlagen durch den Einsatz innovativer Latentwärmespeicher (08-Fo-53330/2015)," Villach, 2018.

- Pesaran, "Battery Thermal Management in EVs and HEVs: Issue and Solution," in Advanced Automotive Battery Conference, Las Vegas, 2001.

- P. Nelson, D. Dees, K. Amine and G. Henriksen, "Modeling thermal management of lithium-ion PNGV batteries," in Journal of Power Sources Volume 110, 2002, pp. 349-356.

- M. Sterner and I. Stadler, Energiespeicher, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2014.

- Hauer, S. Hiebler and M. Reuß, Wärmespeicher, Fraunhofer IRB, 2012.

- F. Kenfach and M. Bauer, "Innovative Phase Change Material (PCM) for heat storage for industrial applications," in 8th International Renewable Energy Storage Conference and Exhibition, Berlin, 2013.

- R. T. GmbH, "Rubitherm Technologies GmbH," [Online]. Available: https://www.rubitherm.eu/index.php/produktkategorie/organische-pcm-rt. [Accessed ]. 23 April.

- S. Thaler, S. Figueira das Silva, R. Hauser and R. Lackner, "Experimental Investigation on Phase Change Materials for Thermal Management of Lithium-ion Battery Packs," Atlantis Highlights in Engineering, volume 6, 2021.

- F. H. Froes and R. Boyer, Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry - 1st edition, Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier, ISBN 9780128140635, 2019.

- G. Tromans, Developments in Rapid Casting - 1st edition, London (United Kingdom): John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781860583902, 2004.

- J. Zhang and Y.-G. Jung, Additive Manufacturing: Materials, Processes, Quantifications and Applications - 1st edition, Oxford (United Kingdom): Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN 9780128123270, 2018.

- E. Toyserkani, D. Sarker, O. O. Ibhadode, F. Liravi, P. Russo and K. Taherkhani, Metal Additive Manufacturing - 1st edition, New Jersey (United States of America): John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781119210832, 2021.

- M. K. Niaki and F. Nonino, The Management of Additive Manufacturing: Enhancing Business Value - 1st edition, Cham (Switzerland): Springer, ISBN 9783319563091, 2017.

- Zettel Dominic et al. (2023). Direct Metal Laser Sintering - Setup-dependent material characteristics of topologies for multi-functional part optimization. In Kadkhodapour Javad, Quality analysis of additively manufactured metals - 1st edition, Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-323-88664-2, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).