Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

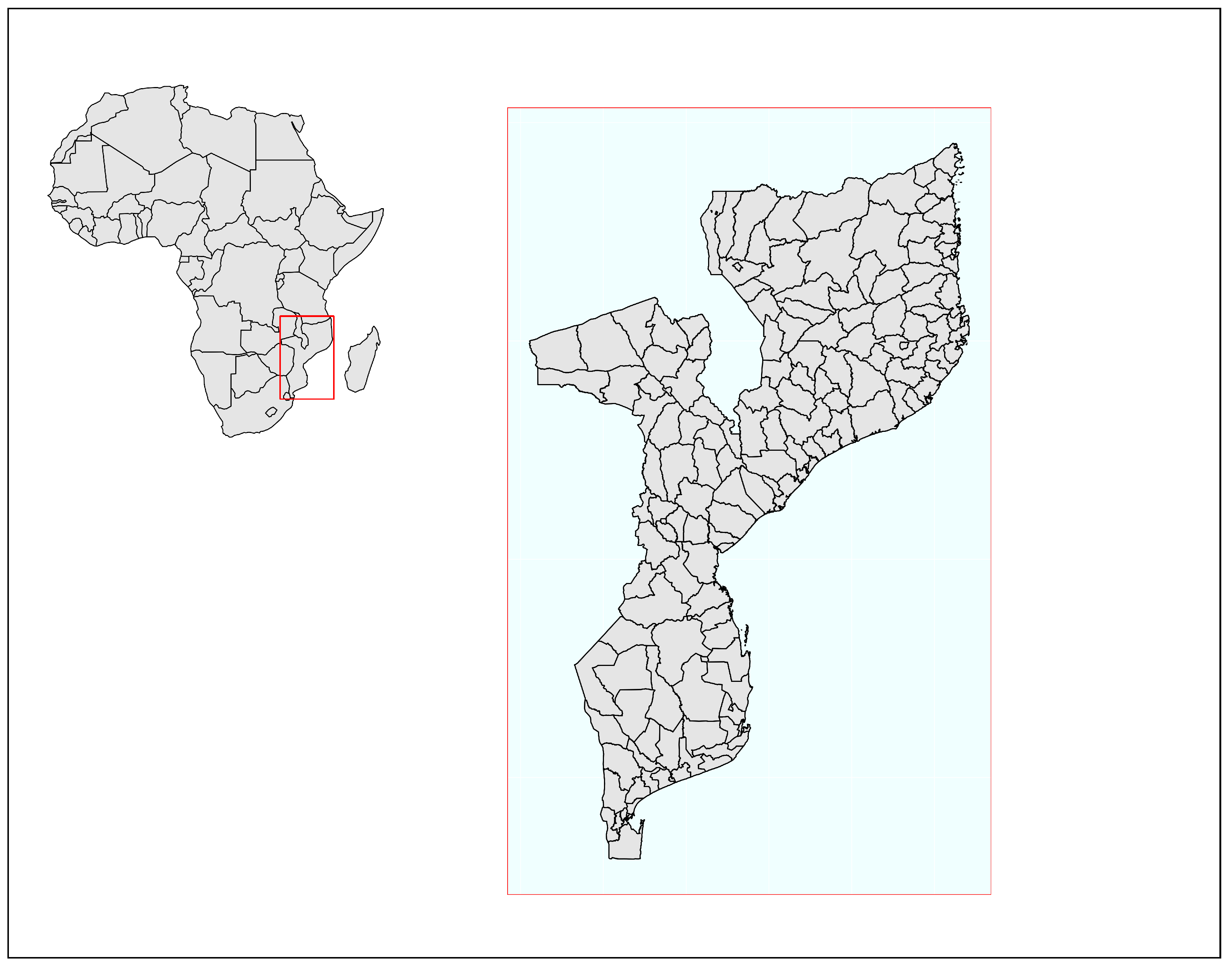

2.1. Study area and climate

2.2. Study design

2.3. Data source

2.3.1. Climate data

2.3.2. Epidemiological data

2.3.3. Socio-economic data

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Vulnerability assessment model

| Vulnerability determinant | Components | Indicators | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average temperature variation (1970-2016) | NOAA | ||

| Exposure | Changes on precipitation, temperature and relative humidity | Average rainfall variation (1970-2016) | Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) version 2.1 |

| Average variation in the relative humidity (1970-2016) | ECMWF (European Center for Medium Weather Forecast) - Climate Data Store | ||

| Extreme events | Historical data on the frequency of floods, droughts and cyclones (1979-2019) | DesInventar data [23] . | |

| Sensitivity | Natural capital (Ecosystem / Geography - Risks) | Frequency of cholera outbreaks | |

| Frequency of food insecurity episodes | Ministry of health | ||

| Natural capital (Demography and vulnerable population) | Population density | ||

| Percent of children under five in the district | |||

| Percent of children aged 5-15 years in the district | Census data [39] | ||

| Percent of women in the district | |||

| percent of elderly people (over 60 years old) in the total population in the district | |||

| Vulnerable population due to health conditions | HIV positivity rate | ||

| Rate of reported cases of tuberculosis | |||

| Average number of cases of acute and chronic malnutrition reported between 2017 and 2018 per 100 000 inhabitants | Ministry of Health (National Division of public health) | ||

| Average number of cases of malaria reported between 2017 and 2018 per 100 inhabitants | |||

| Average number of reported cases of diarrheal diseases between 2017 and 2018 per 100 000 inhabitants | |||

| Adaptive capacity | Financial resources | Per capita public sector health expenditure | Ministry of Health (division of administration and finance) |

| Health services | Ratio of the total number of inhabitants to the total number of health units in the district Percentage of population living within the coverage radius of a health facility |

Census data[39] and SARA report [40] | |

| Human resources | Ratio of medical workers per 100,000 inhabitants Ratio of nursing workers per 100,000 inhabitants Ratio of workers in the midwifery area per 100,000 inhabitants Number of inhabitants per health elementary multipurpose agents (APE) |

Ministry of Health (division of human resource) Ministry of Health (a division of public health) and census data [39] |

|

| Water and sanitation | percentage of population with access to safe water sources Percentage of population with access to safe latrines |

Census data [39] | |

| Social capital (Social determinants of health) | Percentage of literate population, men Percentage of population with primary education, men Percentage of population with secondary education, men Percentage of literate population, women Percentage of population with primary education, women Percentage of population with secondary education, women Per capita expenditure |

Census data [39] National household budget survey report [41] |

3. Results

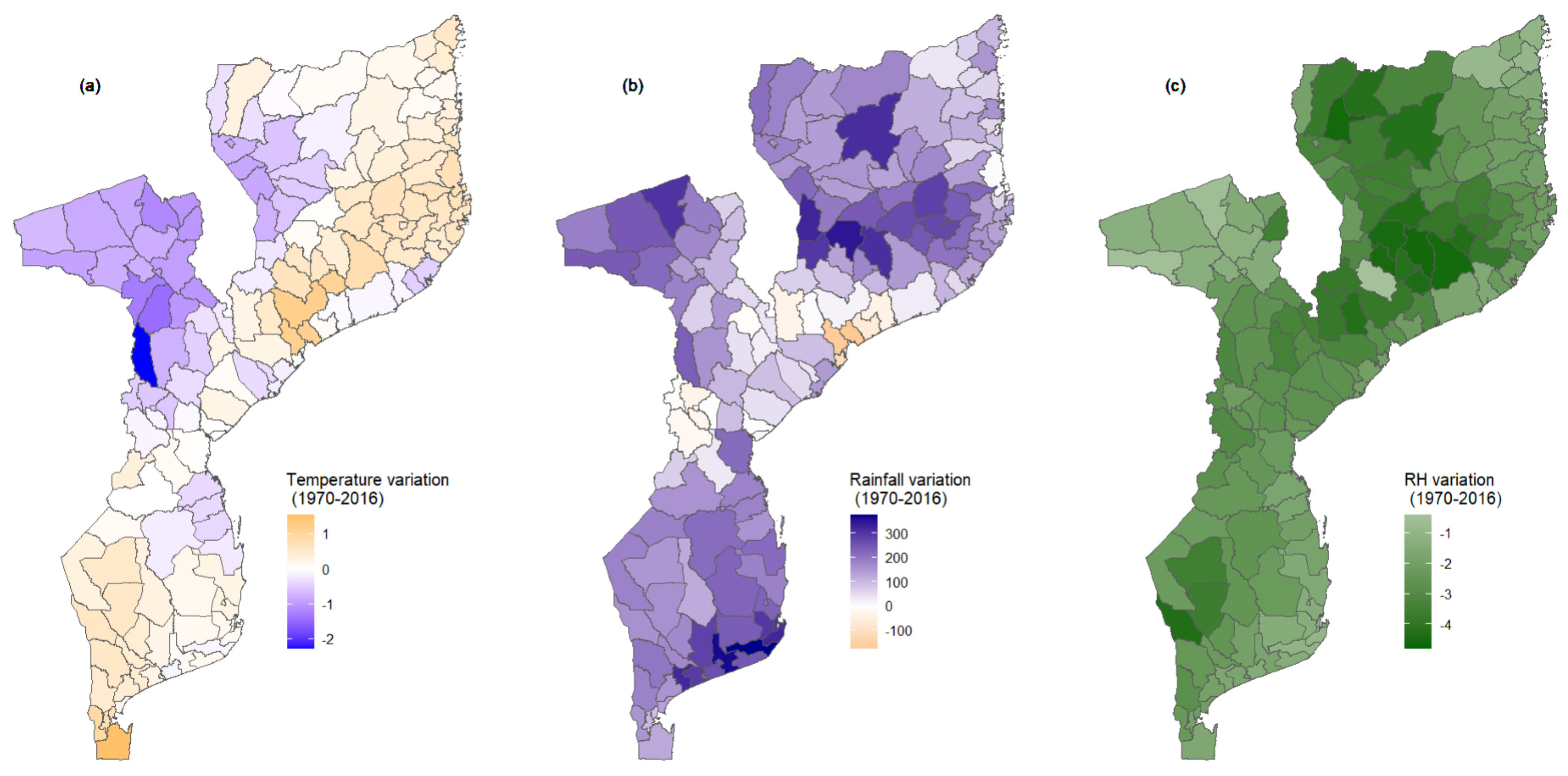

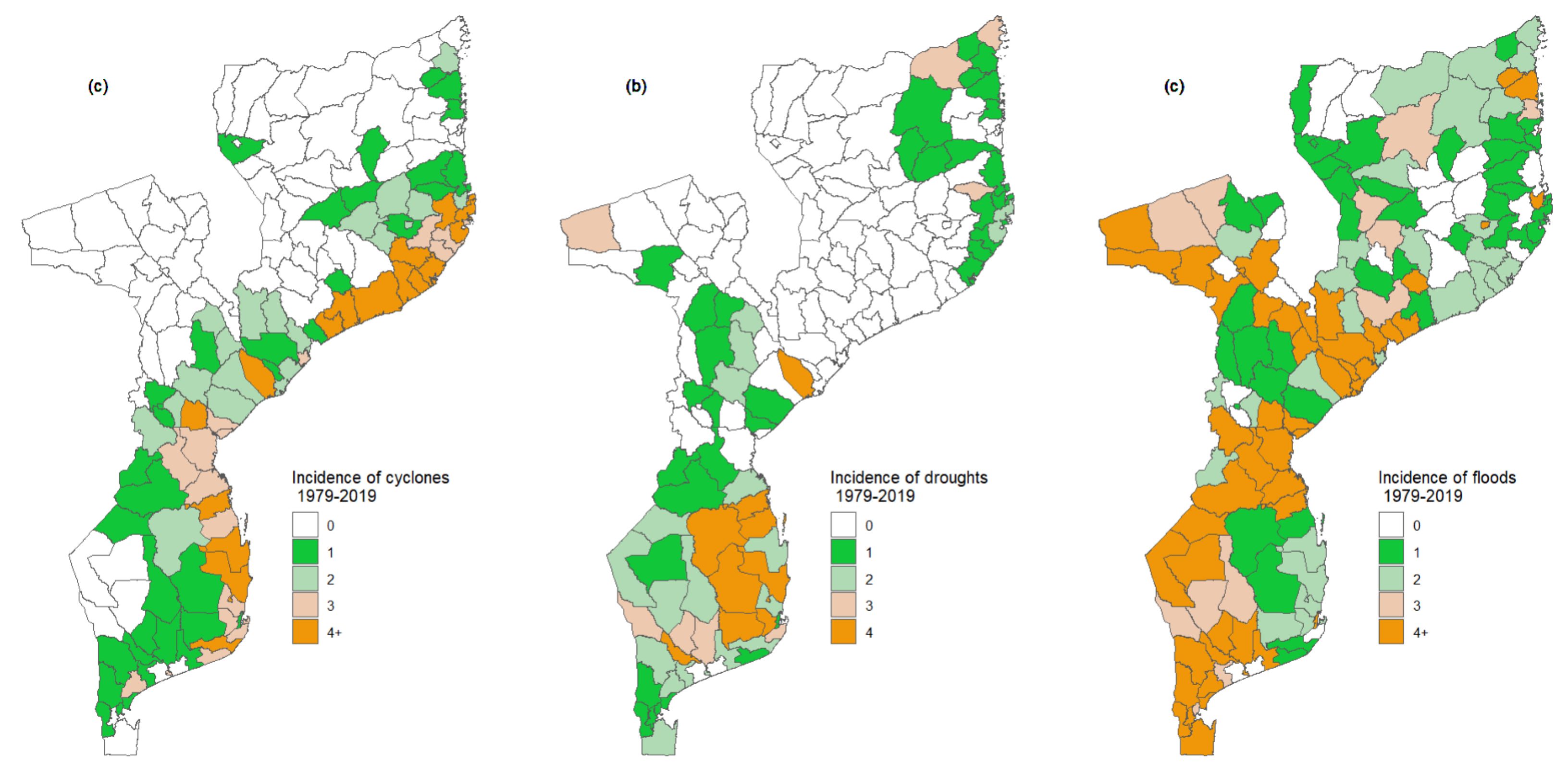

3.1. Exposure

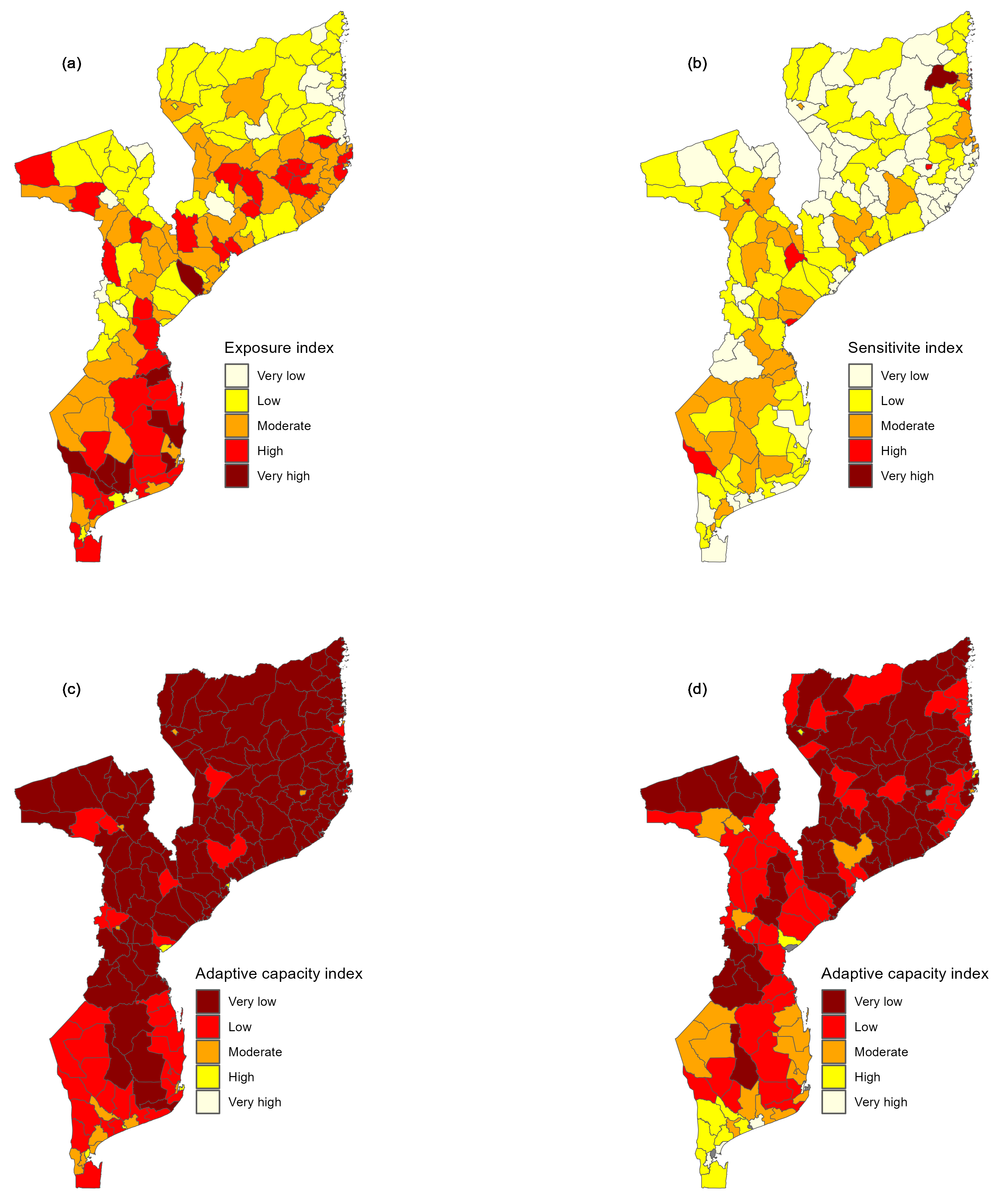

3.2. Exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity index

3.3. Adaptive capacity determinants

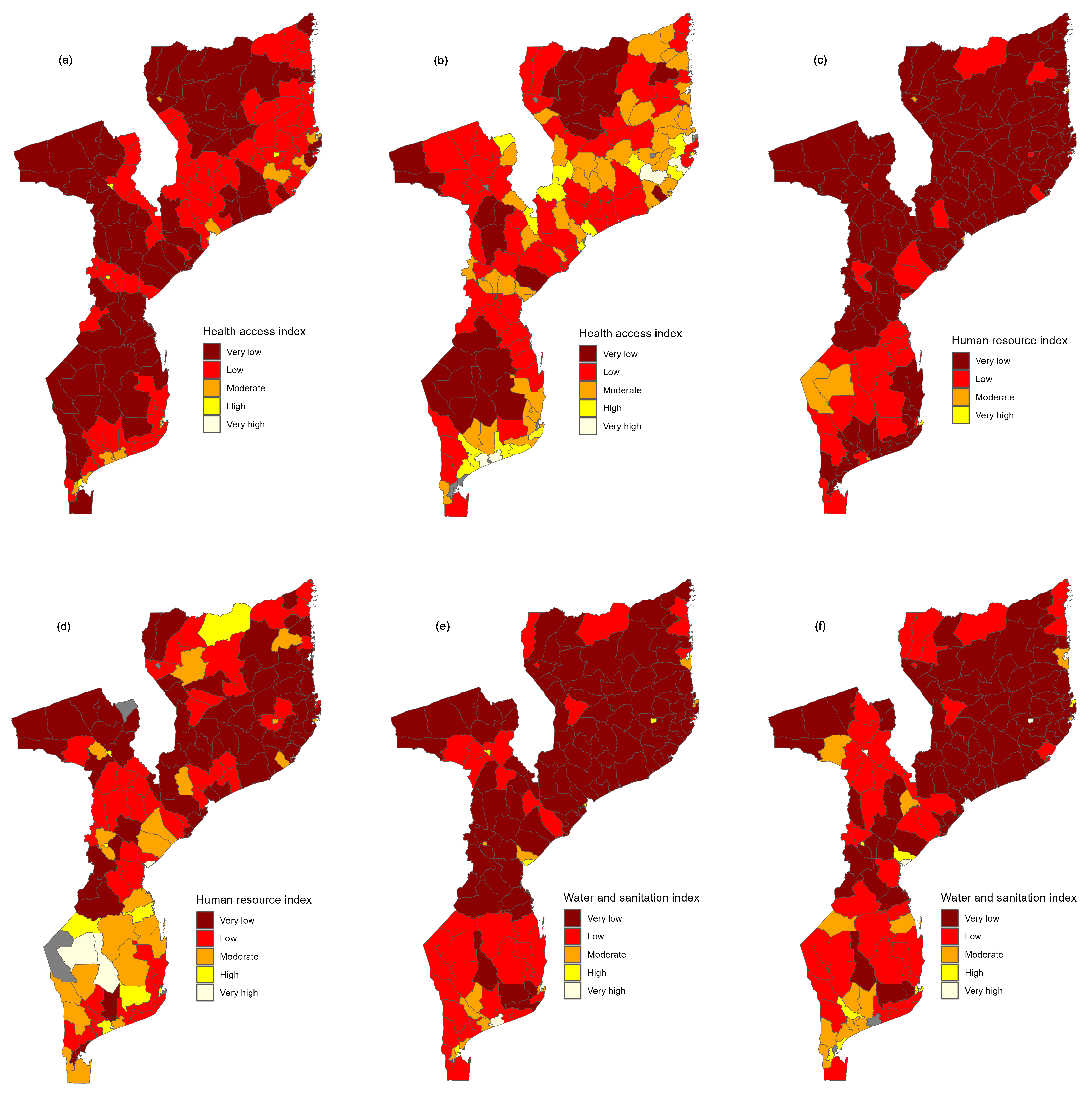

3.3.1. Access to health services

3.3.2. Human resources for health services

3.3.3. Water and sanitation

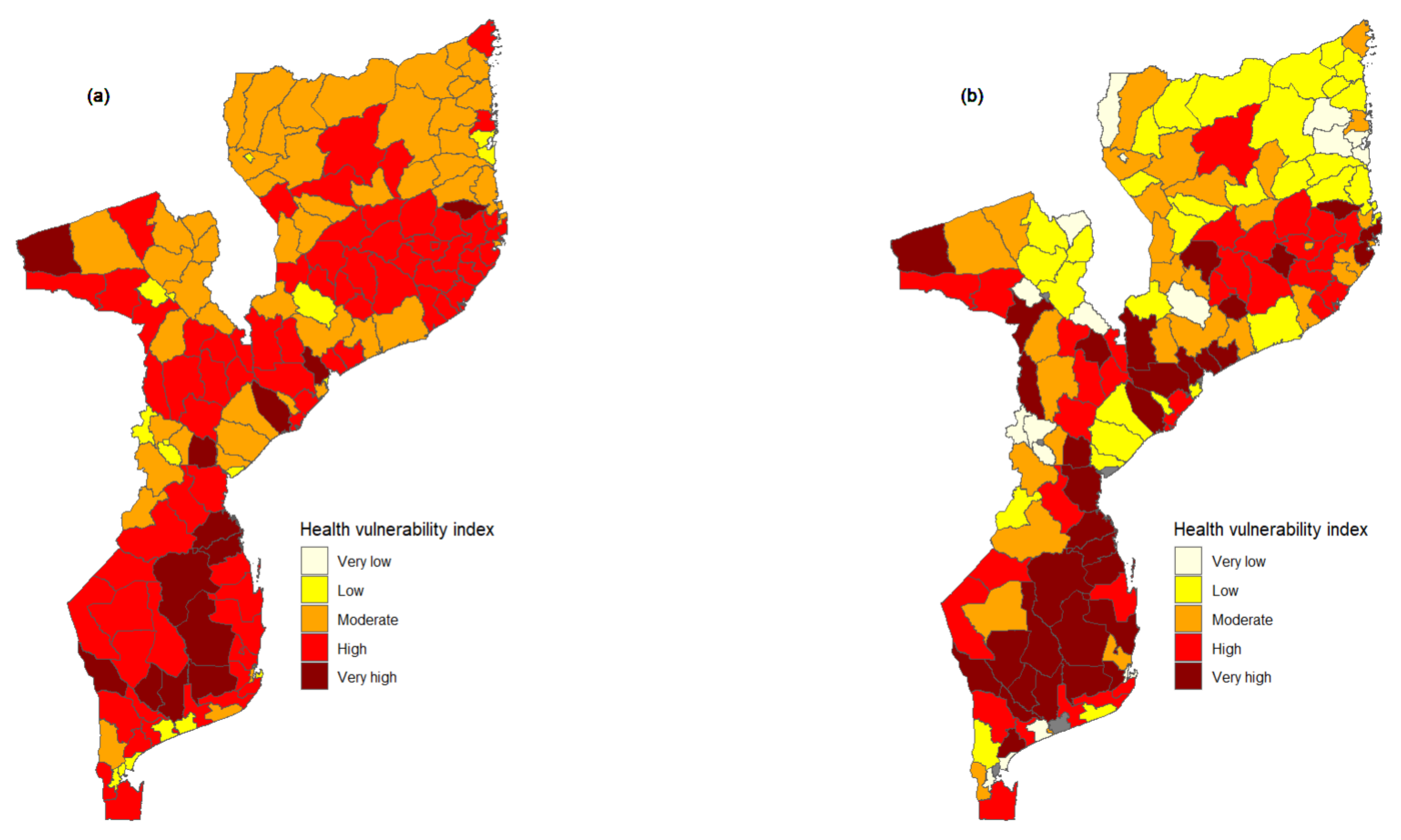

3.4. Global health vulnerability index

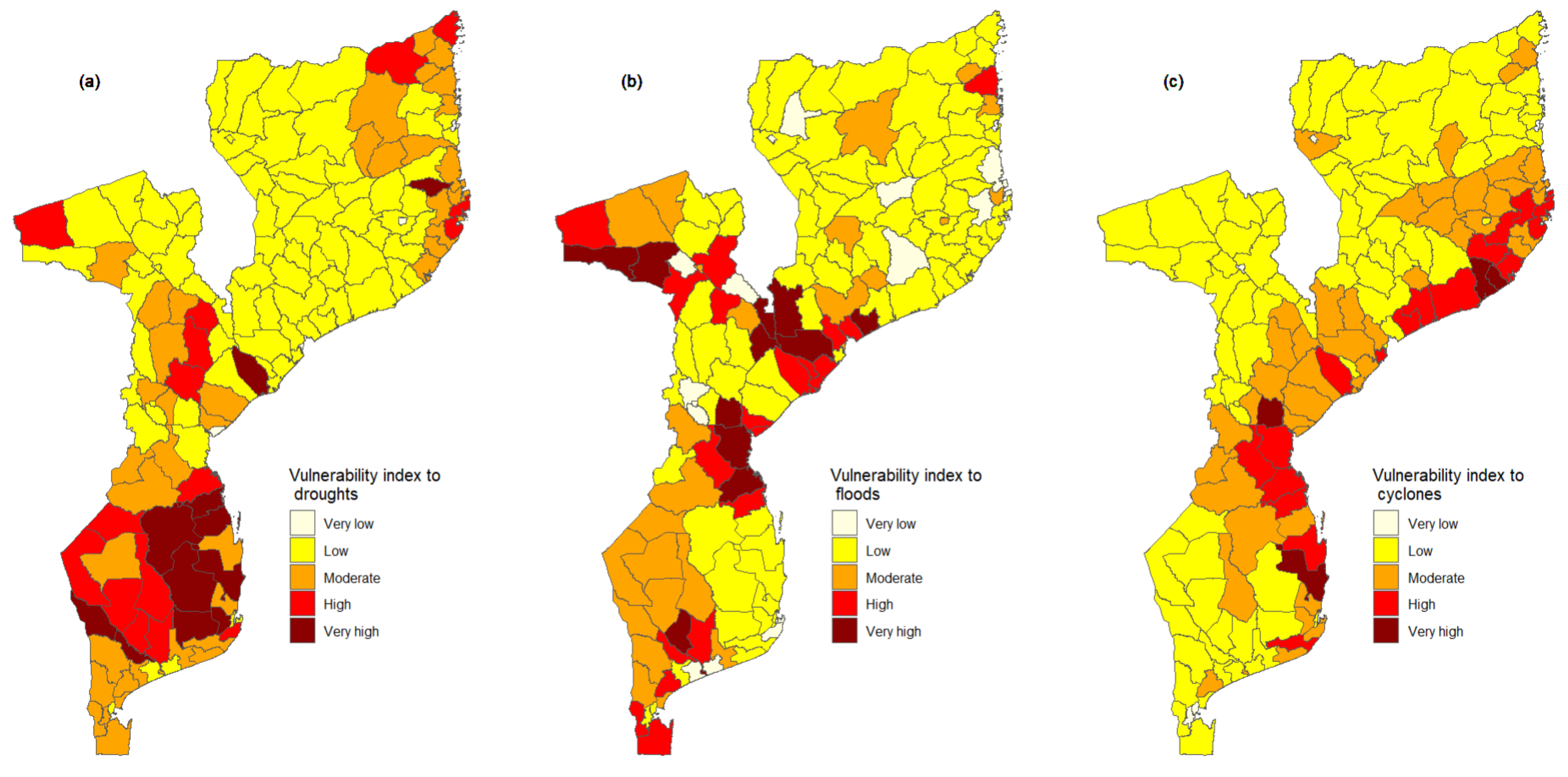

3.5. Vulnerability index to droughts, floods and cyclones

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Monday, I.F. Investigating Effects of Climate Change on Health Risks in Nigeria. In Environmental Factors Affecting Human Health; Uher, I., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2019; chapter 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate change 2001: the scientific basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2001.

- Ojomo, E.; Elliott, M.; Amjad, U.; Bartram, J. Climate Change Preparedness: A Knowledge and Attitudes Study in Southern Nigeria. Environments 2015, 2, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafino, B.A.; Walsh, B.; Rozenberg, J.; Hallegatte, S. Revised estimates of the impact of climate change on extreme poverty by 2030, 2020.

- WMO. Climate change triggers food insecurity, poverty and displacement in Africa. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/climate-change-triggers-food-insecurity-poverty-and-displacement-africa (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Manga, L.; Bagayoko, M.; Sommerfeld, J. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: what are the implications for public health research and policy? Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci 2015, 370, 20130552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J.C.; Rocklöv, J.; Ebi, K.L. Climate Change and Cascading Risks from Infectious Disease. Infect Dis Ther 2022, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Young, H.; Cornforth, R.; Petty, C. Climate and health in Africa: research and policy needs, 2019.

- McGlade, J.; Bankoff, G.; Abrahams, J.; Cooper-Knock, S.; Cotecchia, F.; Desanker, P.; Erian, W.; Gencer, E.; Gibson, L.; Girgin, S.; et al. Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2019, 2019.

- Unicef. Cyclone Gombe: Impacto das mudanças climáticas nas mulheres e raparigas em Moçambique. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mozambique/historias/cyclone-gombe-impacto-das-mudan%C3%A7as-clim%C3%A1ticas-nas-mulheres-e-raparigas-em-mo%C3%A7ambique (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Masters, J. CAfrica’s Hurricane Katrina: Tropical Cyclone Idai Causes an Extreme Catastrophe. 2019. Available online: https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/Africas-Hurricane-Katrina-Tropical-Cyclone-Idai-Causes-Extreme-Catastrophe (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- ACSS. Cyclones and More Frequent Storms Threaten Africa. Available online: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/cyclones-more-frequent-storms-threaten-africa/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- WHO. Tropical cyclone Idai Mozambique - Situation Report 01 April 06 2019. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2019-05/WHOSitRep1Mozambique06-07-2019.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- WHO. Tropical Cyclones Idai and Kenneth Mozambique - National situation report 2nd August 2019. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2019-08/SitRep%208_MOZ_15%20%20t%2028%20Jul%202019_ENG.pdf, 2019 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Unicef. Cyclone Idai and Kenneth cause devastation and suffering in Mozambique. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mozambique/en/cyclone-idai-and-kenneth (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Suit, K.C.; Choudhary, V. Mozambique agricultural sector risk assessment, 2015.

- Parkinson, V. Climate learning for African agriculture: the case of Mozambique. University of Greenwich: London, UK, 2013, pp. 1–62.

- Coetzee, K. Climate Change and Trade: The Challenges for Southern Africa, 2011.

- Ministério do Mar, Águas Interiores e Pesca. Elaboração do plano de ordenamento do espaço marítimo [Preparation of the maritime spatial planning plan], 2020.

- Uele, D.I.; Lyra, G.B.; Oliveira, J.F.d. Variabilidade espacial e intranual das chuvas na região sul de moçambique, África Austral. Rev Bras de Meteorol 2017, 32, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Protecting health from climate change: vulnerability and adaptation assessment, World Health Organization. 2013.

- Fritzsche, K.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Bubeck, P.; Kienberger, S.; Buth, M.; Zebisch, M.; Kahlenborn, W. The Vulnerability Sourcebook: Concept and guidelines for standardised vulnerability assessments, 2014.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Desinventar Sendai 10.1.2-User Manual Administration and Data Management, 2019.

- Adger, W.; Agrawala, S.; Mirza, M.; Conde, C.; O’Brien, K.; Pulhin, J.; Pulwarty, R.; Smit, B.; Takahashi, K. Assessment of adaptation practices, options, constraints and capacity. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change; Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 717–743. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, D.; Polsky, C.; Patt, A.G. Assessing vulnerabilities to the effects of global change: an eight step approach. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 2005, 10, 573–595. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.A.R.; Raju, B.M.K.; Rao, A.V.M.S.; Rao, K.V.; Rao, V.U.M.; Ramachandran, K.; Venkateswarlu, B.; Sikka, A.K.; Rao, M.S.; Maheswari, M.; et al. A district level assessment of vulnerability of Indian agriculture to climate change. Curr Sci 2016, 110, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Stocker, T.F.; Dahe, Q. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change; Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- O’Brien, K.; Leichenko, R.; Kelkar, U.; Venema, H.; Aandahl, G.; Tompkins, H.; Javed, A.; Bhadwal, S.; Barg, S.; Nygaard, L.; et al. Mapping vulnerability to multiple stressors: climate change and globalization in India. Glob Environ Change 2004, 14, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T.E. Choosing Methods in Assessments of Vulnerable Food Systems, 2008.

- Krellenberg, K.; Welz, J. Assessing Urban Vulnerability in the Context of Flood and Heat Hazard: Pathways and Challenges for Indicator-Based Analysis. Soc Indic Res 2017, 132, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.D.; Dat, T.T.; Hang, N.D.; Huan, L.H. Vulnerability Assessment of Climate Change in Vietnam: A Case Study of Binh Chanh District, Ho Chi Minh City. Front Environ Sci 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Bonetti, J.; Rogers, K.; Woodroffe, C.D. Indicator-based assessment of climate-change impacts on coasts: A review of concepts, methodological approaches and vulnerability indices. Ocean Coast Manag 2016, 123, 18–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gbetibouo, G.A.; Ringler, C.; Hassan, R. Vulnerability of the South African farming sector to climate change and variability: An indicator approach. Nat Resour Forum 2010, 34, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luh, J.; Christenson, E.C.; Toregozhina, A.; Holcomb, D.A.; Witsil, T.; Hamrick, L.R.; Ojomo, E.; Bartram, J. Vulnerability assessment for loss of access to drinking water due to extreme weather events. Climatic change 2015, 133, 665–679. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, K.U.; Dulal, H.B.; Johnson, C.; Baptiste, A. Understanding livelihood vulnerability to climate change: Applying the livelihood vulnerability index in Trinidad and Tobago. Geoforum 2013, 47, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.G.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Jesdale, B.M.; Kyle, A.D.; Shamasunder, B.; Jerrett, M. An Index for Assessing Demographic Inequalities in Cumulative Environmental Hazards with Application to Los Angeles, California. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43, 7626–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—A case study in Mozambique. Glob Environ Change 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2022.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. IV Recenseamento geral da população e habitação 2017-Resultados definitivos [IV General Census of Population and Housing 2017-Definitive Results], 2019.

- Ministério da Saúde. Service Availability and Rediness Assessment (SARA) 2018: Inventário Nacional, 2018.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Relatório Final do Inquérito ao Orçamento Familiar- IOF 2014/15, 2015.

- Mavume, A.F.; Banze, B.E.; Macie, O.A.; Queface, A.J. Analysis of Climate Change Projections for Mozambique under the Representative Concentration Pathways. Atmosphere 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, P.; Augusto, G.; Akande, A.; Costa, A.; Amade, N.; Niquisse, S.; Atumane, A.; Cuna, A.; Kazemi, K.; Mlucasse, R.; et al. Assessing Mozambique’s exposure to coastal climate hazards and erosion. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2017, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondlane, A. Floods and droughts in Mozambique–the paradoxical need of strategies for mitigation and coping with uncertainty. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2004, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.A.; Eriksen, S.; Ombe, Z.A. Double Exposure in Mozambique’s Limpopo River Basin. The Geographical Journal 2010, 176, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongo, E.; Cambaza, E.; Nhambire, R. Outbreak of cholera due to cyclone Idai in central Mozambique (2019). In Evaluation of Health Services; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Mugabe, V.A.; Gudo, E.S.; Inlamea, O.F.; Kitron, U.; Ribeiro, G.S. Natural disasters, population displacement and health emergencies: multiple public health threats in Mozambique. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e006778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariado de Técnico de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional. Relatório da Avaliação da Situação de Insegurança Alimentar e Nutricional Aguda Póschoque de Abril - Maio de 2019, 2019. Accessed: 22022-02-26.

- Atanga, R.A.; Tankpa, V. Climate Change, Flood Disaster Risk and Food Security Nexus in Northern Ghana. Front Sustain Food Syst, 2021, p. 273. [CrossRef]

- Secretariado de Técnico de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional. Relatório da Monitoria da Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional em Moçambique (versão final)”, 2007.

- Smit, B.; Pilifosova, O.; Burton, I.; Challenger, B.; Huq, S.; Klein, R.; Yohe, G.; Adger, W.; Downing, T.; Harvey, E. Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. In Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom, 2001; pp. 877–912. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.B.; Lenhart, S.S. Climate change adaptation policy options. Clim Res 1996, 6, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INS, INE, and ICFI. Moçambique Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011, 2013. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr266/fr266.pdf.

- dos Anjos Luis, A.; Cabral, P. Geographic accessibility to primary healthcare centers in Mozambique. Int J Equity Health 2016, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, S.; Kostermans, K. Improving health for the poor in Mozambique: the fight continues, 2002.

- Bao, X.; Zhang, F. How Accurate Are Modern Atmospheric Reanalyses for the Data-Sparse Tibetan Plateau Region? J Clim 2019, 32, 7153–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério para a Coordenação Ambiental. Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação e Mitigação de Mudanças Climáticas [National Strategy for Adaptation and Mitigation of Climate Change], 2012.

- UNICEF. Massive flooding in Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe, 2019. Acessed: 2022-09-09.

- International Labour Organization. Green Jobs: Improving the Climate for Gender Equality Too! International Institute for Labour Studies. 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).