1. Introduction

Early detection of diseases tends to improve the prognosis while opening up many avenues for successful treatment. In many diseases, biomarkers serve as an important tool for discerning pathophysiology, and the identification of biomarkers has therefore emerged as a crucial aspect in contemporary clinical diagnosis and the subsequent treatment [

1]. Of the many biomarkers that are of clinical significance, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an important biomarker that plays a key role in angiogenesis as well as many physiological and pathological processes such as wound healing [

2], tumor growth [

3,

4,

5], and lung development [

6]. In addition, VEGF is implicated in various retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [

7], diabetic retinopathy [

8], and retinopathy of prematurity [

9]. As such, these render VEGF as a critical biomarker during clinical diagnosis and the quantification and detection of VEGF can facilitate the overall prognosis and treatment of the disease as a whole.

So far, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the main immunoassay technique for detecting VEGF. The sensitivity of ELISA is well-established and is sensitive enough to even discern the various isoforms of VEGF commonly detected under clinical setting [

10]. However, there are some disadvantages of using ELISA for VEGF detection. Firstly, ELISA may sometimes produce false-positive or false-negative detection and this may adversely affect the diagnosis outcome or treatment. Secondly, ELISA can be rather time-consuming and not very cost-effective for undeveloped rural areas or in some third world countries. There are also concerns pertaining to the limitation in the dynamic range of ELISA detection as well as the susceptibility of cross-interference from biological serums. Hence, it is necessary to find a quick and inexpensive replacement for ELISA, and in recent years, there had been much advancement towards developing such newer diagnostic platforms.

As such, there had been a wide range of different type of biosensors that have been suggested as a viable replacement for ELISA. For instance, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is one such sensitive and specific biosensor for detecting VEGF based on a relatively straightforward concept of optical sensing. Such biosensor relies on measuring changes in refractive index that occur in the vicinity of a sensor chip that had been precoated with immobilized bioreceptors (such as antibodies or aptamers) for the capture of VEGF. Upon binding, a change in refractive index will be registered as a shift in the angle of reflected light, which is proportional to the amount of VEGF bound to the sensor surface [

11]. In addition, there are also various electrochemical based biosensors (amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric biosensors) that had been developed accordingly. Amperometric biosensors will measure the current produced by the oxidation or reduction of electroactive species generated by the binding of VEGF to an immobilized bioreceptor. In conjunction, potentiometric biosensors detect changes in the potential difference between two electrodes, one of which is functionalized with an appropriate bioreceptor and the other with a non-specific protein that serves as a reference. The potential change will be caused by the selective binding of VEGF to the bioreceptor, which in turn alters the charge distribution at the electrode surface. Impedimetric biosensors, on the other hand, measure changes in the electrical impedance of a solution containing the immobilized bioreceptor and VEGF, which can be attributed to changes in the dielectric properties or charge distribution of the solution [

12]. Additionally, electronic biosensors based on semiconductor technology, such as silicon nanowire (SiNW) field-effect transistor (FET), can offer unparalleled sensitivity for the detection of VEGF by measuring changes in conductivity when VEGF binds to the nanowire surface. Due to the small size of the nanowire and the high surface-to-volume ratio, this approach can detect extremely low concentrations of VEGF with high accuracy and precision [

13]. These strategies as highlighted above exhibit relatively faster detection speed and are less labor intensive compared to conventional ELISA.

Another interesting and inexpensive biosensor alternative that can be on contention are interdigitated sensors. These sensors are generally described as microelectrodes arranged as interdigitated fingers that may be used to measure changes in impedance or conductivity of the surrounding medium [

14]. With the appropriate surface chemical modification, VEGF molecules can be captured on the electrode surface which subsequently resulting in a change in the dielectric properties of the medium which modulates the overall impedance. The information collected from the impedance measurements can then be used to produce an impedance spectrum by scanning at different frequencies, which in turn would provide an estimate of the concentration of VEGF molecules that is present in the medium [

15]. Interdigitated sensors are considered to be promising for detecting VEGF owing to several advantages over alternative methods. Compared to ELISA, interdigitated sensors offer rapid detection while eliminating the need for secondary antibodies and enzymes and this largely reduces the overall complexity and cost of the assay. Furthermore, interdigitated sensors can provide real-time monitoring of binding events and this enables the dynamic measurement of VEGF concentration. Unlike SPR, dedicated interdigitated sensors may even offer higher sensitivity and a broader range of detection attributed to the larger sensing area and comparatively lower noise level. Furthermore, when compared to the other electrochemical biosensors such as amperometric and potentiometric biosensors, impedance spectroscopy in tandem with interdigitated sensor may offer detailed information on the binding kinetics and structural changes of the bioreceptor upon VEGF binding, thus allowing for a better understanding of the interaction mechanism. Interdigitated sensors are also easier to fabricate a

nd can be mass-produced at a lower cost compared to electronic biosensors such as SiNW FET while maintaining robust for everyday use. In conjunction to these attributes, the non-destructive nature of impedance spectroscopy makes it potentially suitable for long-term monitoring and repeated measurements while the resilience of the material permits for more robust handling, even under less ideal conditions. Hence, it is therefore envisaged that miniaturized interdigitated sensors with impedance spectroscopy may have the potential to be integrated into portable and handheld devices for point-of-care testing [

16].

So far, specific interdigitated sensors have already been developed for VEGF detection. For instance, Kim

et al. proposed an impedance biosensor for detecting VEGF using a poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT)/gold nanoparticle (Au NP) composite material. The authors deposited PEDOT-Au NP composites on three different interdigitated electrode designs. The anti-VEGF antibodies were covalently immobilized on the surface of the polymer films, and the resulting composites were used to detect VEGF-165 by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Among different interdigitated electrode designs, the interdigitated strip shape showed the best overall film stability and reproducibility [

17]. In another study, Sun

et al. utilized the complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technique to develop a low-power sensing system for VEGF detection. The monolithic interdigitated electrodes were used as the transducer, and post-process etching and Au plating were applied to the surface of the electrodes. Experimental results showed that the biosensor achieved a capacitive resolution of 28.3 fF and a sensing range of VEGF concentration from 1 to 1000 pg/mL [

18]. While both studies [

17,

18] can achieved highly sensitive detection of VEGF, the complex fabrication procedures as well as expensive setup was required to attain this level of sensitivity, and this may limit practical applications of such techniques. Hence, there is a need to produce a more cost-effective interdigitated sensor that is capable for detecting VEGF under less ideal operation conditions.

In this manuscript, we proposed an aptamer-based nanolayer grafting for VEGF detection on commercially available interdigitated sensors. DNA aptamers had been used as a targeting moiety instead of conventional antibody and this is due to the fact that aptamers are more robust and resilient under a wider range of physiological conditions and these have very high binding affinity as well to its target [

19]. In this manuscript, we had achieved detectable VEGF limit of 200 pg/mL (5 pM). Although the detection level does not reach the level of the commercial ELISA kit (such as 1 pg/mL of MBS355343, MyBioSource Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) [

20], we found that our inexpensive setup was within the clinically relevant range [

21]. Additionally, the relative cost-effectiveness makes the proposed approach a promising method for VEGF detection in practical point-of-care applications.

The rest of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 contains the methods and materials used in this study. The experimental results are shown in

Section 3. The implication of this research is discussed in

Section 4. Finally, the conclusions are given in

Section 4.

2. Methods and Materials

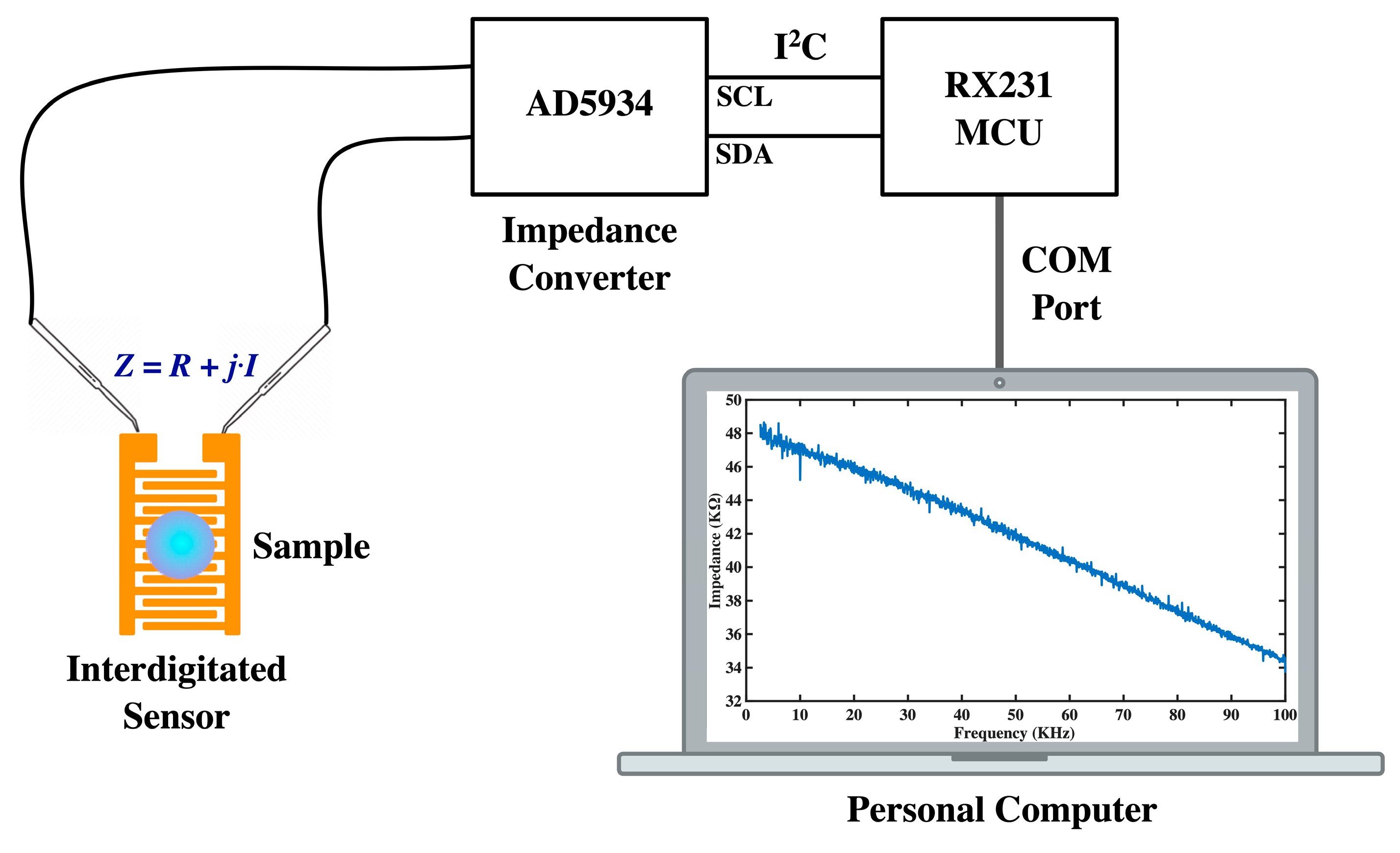

The objective of this study is to develop a cost-effective method for detecting the VEGF protein using readily available interdigitated sensors that are modified with surface chemistry and grafted with aptamers. The aptamer-VEGF complex has a negative charge, which alters the dielectric characteristics between the interdigitated electrodes. This alteration leads to a decrease in impedance when VEGF is captured by the sensor. Since the impedance consists of a capacitance component and the resulting imaginary part of impedance varies with frequency, impedance measurements are taken from 2.5 kHz to 100 kHz to evaluate the concentration of VEGF. To ensure consistency in measurements, the ambient temperature is controlled at around 25 °C in all experiments. In this study, we use the impedance analyzer AD5934 (Analog Devices Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA) [

22] to measure the impedance. This analyzer is a high-precision impedance converter system that combines an on-board frequency generator with a 12-bit, 250k sample per second (SPS) analog-to-digital converter (ADC). The frequency generator applies a sinusoidal excitation signal to the external complex impedance at the specified frequency, and the on-board ADC samples the response signal from the impedance, which is then analyzed by the on-board digital signal processing (DSP) engine. The discrete Fourier transform (DFT) algorithm returns both real (denoted as

R) and imaginary (denoted as

I) parts of the impedance at each specified frequency along each sweep (ranging from 2.5 kHz to 100 kHz, with a 50-Hz separation between sweep frequencies). We use the RX231 microcontroller unit (MCU) (Renesas Electronics Corp., Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan) [

23] to control the impedance scanning and the data access on AD5934 via the inter-integrated circuit (I

2C) bus. The impedance data acquired by MCU is transported to the personal computer via the communication (COM) port and can be observed in the graphical user interface (GUI) application program (App) that is developed in C# language. The impedance spectroscopy can be shown in the form of magnitude versus frequency or imaginary part versus real part in the GUI App. The configuration of impedance measurement is depicted in

Figure 1.

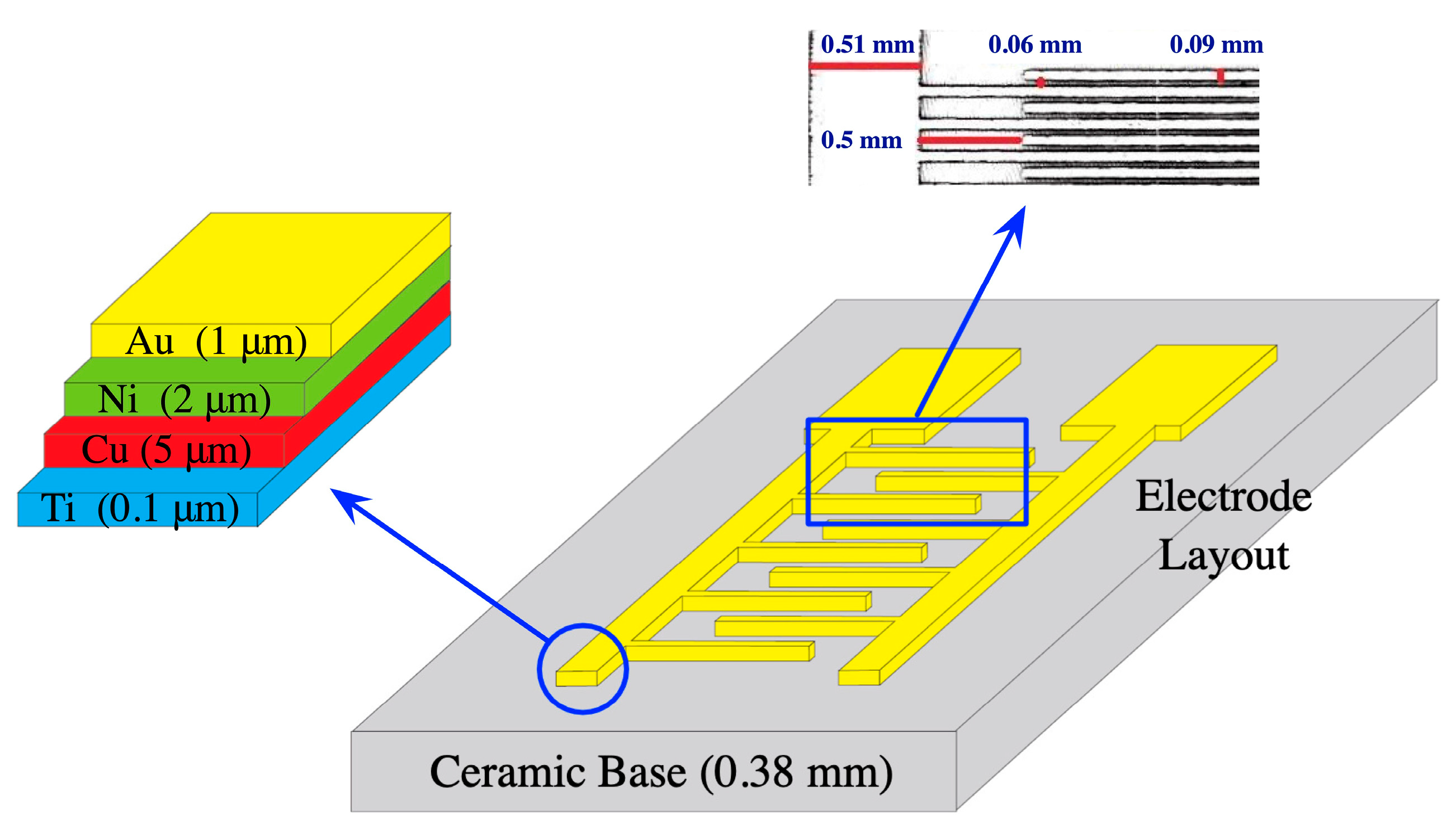

The manufacturing procedure for interdigitated sensors typically involves the following steps [

24]: First, the substrate (such as ceramic, silicon, glass, quartz, or crystalline polyethylene terephthalate) is cleaned and prepared to ensure a clean and uniform surface. Then, layers of metals (such as gold, platinum, nickel, copper, and titanium) are deposited on the substrate by sputtering, evaporation, or chemical vapor deposition to form the conductive surface of the interdigitated sensors. Next, photolithography is applied to the metal layers using a patterned mask and exposing them to ultra-violet (UV) light. This process chemically modifies the areas that are not covered by the mask, allowing the unexposed areas to be selectively removed in a subsequent etching step. The specific details of the manufacturing process may vary depending on the application and desired characteristics of the interdigitated sensor. However, these basic steps provide a general overview of the process, enabling mass production of interdigitated sensors. In this research, interdigitated sensors numbered 10856975, manufactured by Guangzhou MecartSensor Tech. Inc. (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. Website:

http://cn.global-trade-center.com/HotOffers/10856975.html, accessed on May 19, 2023) were utilized for all experiments. These sensors are cost-effective, with a price of less than 0.15 US dollars per piece under bulk orders.

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the used interdigitated sensor, where the conductive layers composed of titanium, copper, nickel, and gold are deposited on ceramic substrate from bottom to top. This figure also demonstrates the thickness of each conductive layer and the geometric layout, including the gap between fingers, width of arm and finger, and the separation between arm and fingers.

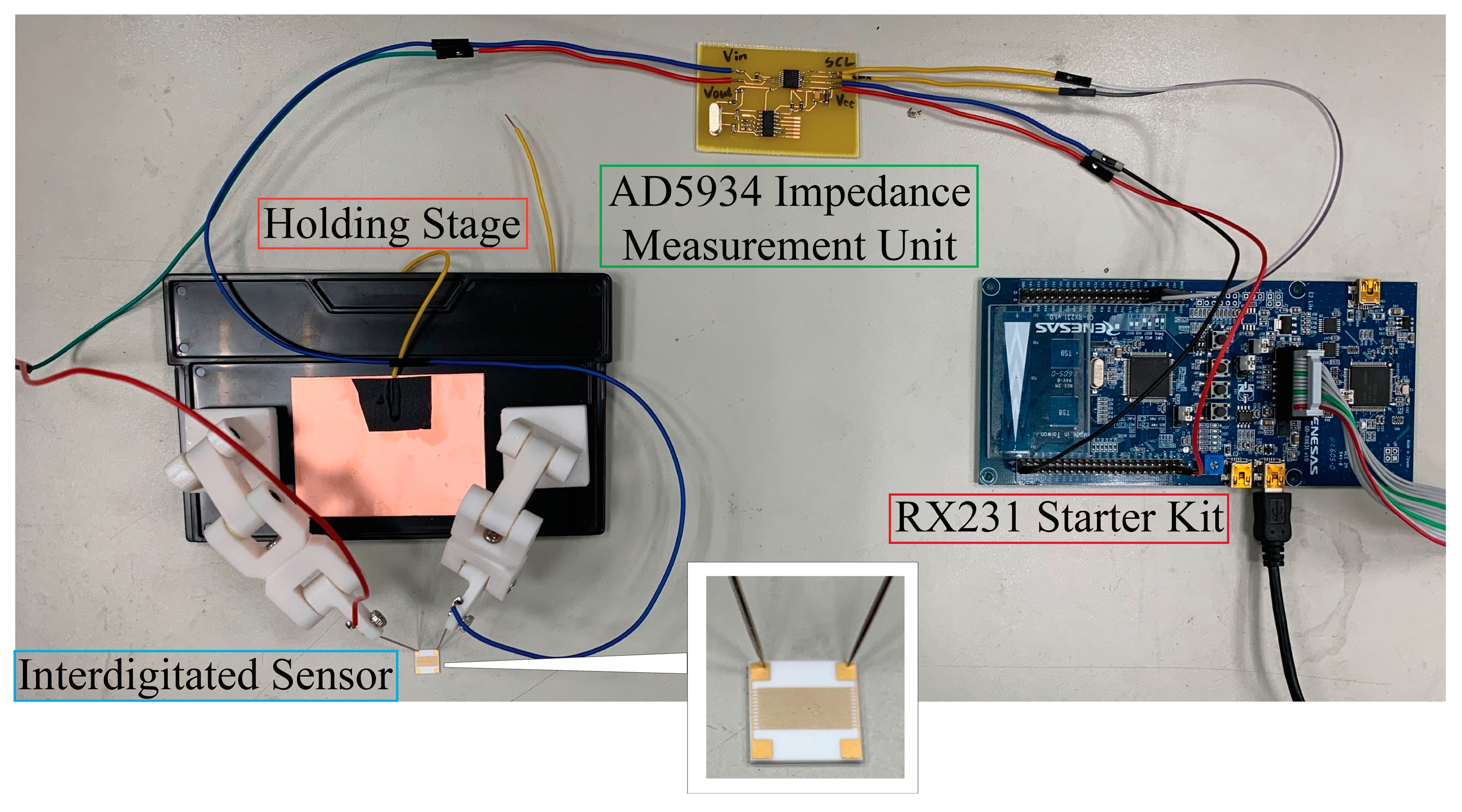

Briefly, in our setup, the modified interdigitated sensor was mounted to a simple customized setup as shown in

Figure 3 as a proof-of-concept. A single drop of protein solution would be subsequently aliquoted directly onto the surface of the sensor carefully and the changes in impedance was immediately monitor via RX231 starter kit and was subsequently connected to a computer workstation. All measurements were performed under normal ambient conditions to best mimic the environment by which handheld point-to-care devices are used. This is to demonstrate the ease of preparation of our simple setup that holds the potential for future device system setup.

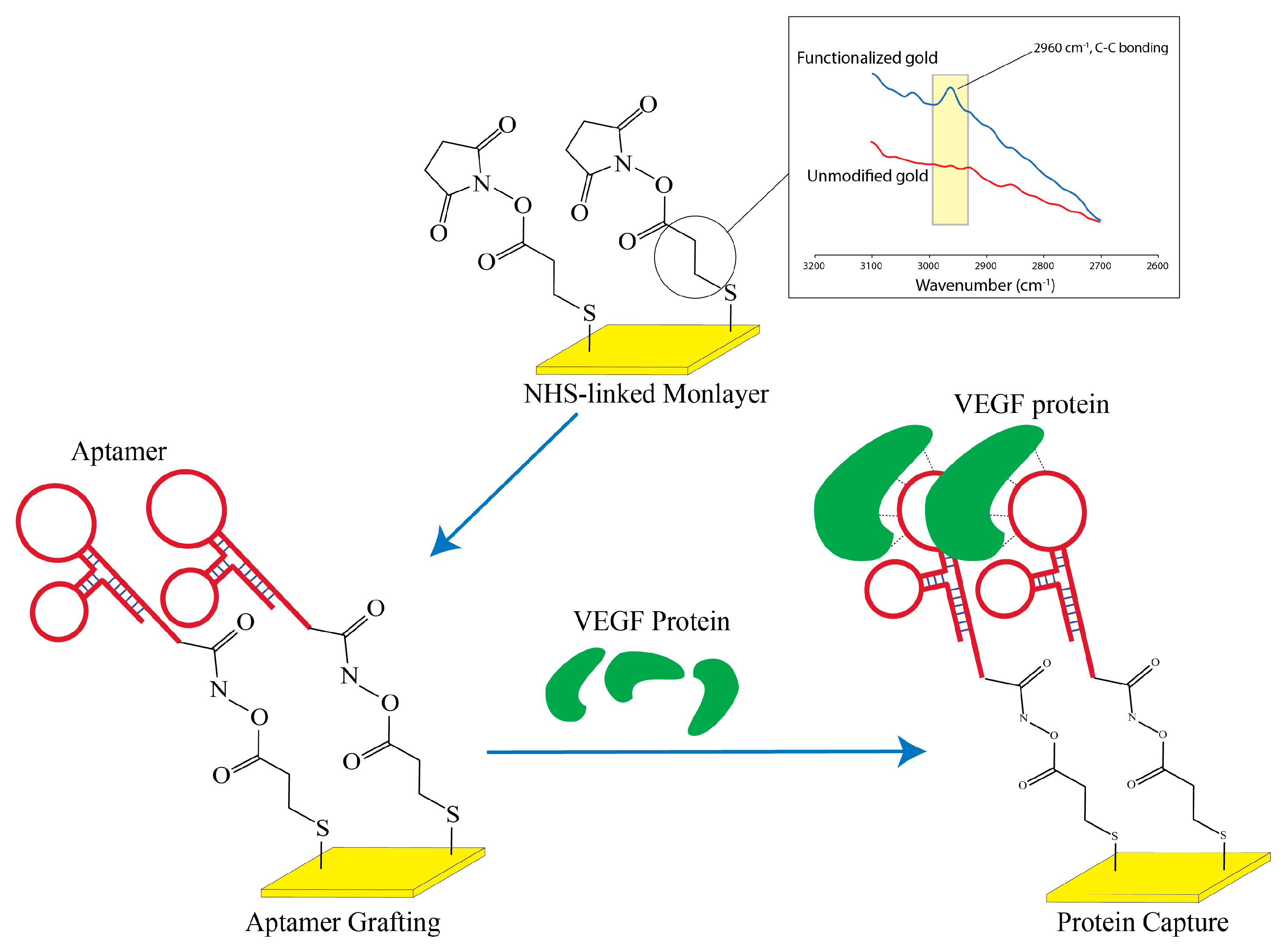

The surface modification and the preparation of the nanolayer aptamer graft on the surface closely follows the previous work as previously published from our group [

13] although the initial grafting relies on thiol based linkages to the surface (

Figure 4). In brief, 20mM of 3-Mercaptopropanyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Sigma-Aldrich) is prepared in a 50% EtOH solution and was directly added to the interdigital surface for two hours at room temperature under constant slow shaking. The thiol moiety would subsequently self-assembled onto the gold surface to present a distal NHS group. After the reaction, the surface was washed with copious amounts of methanol, ethanol, chloroform and deionized water in sequential order and dried under stream of nitrogen.

For protein biosensing intentions, 50nM of DNA aptamer for VEGF 165 (Sequence: 5’ATACCAGTCTATTCAATTGGGCCCGTCCGTATGGTGGGTGTGCTGGCCAGATAGTATGTGCAATCA 3’) [

25] was added to the NHS functionalized surface for a duration of 24h at a pH of 8. After the incubation of the surfaces with the DNA, the interdigital sensors were washed with copious amounts of deionized water and dried under stream of dry nitrogen and stored prior to use. Pertaining to the protein capture studies, both VGEF and PDGF were acquired from Novubios and was diluted to the apparent concentration (5 and 50pM) with PBS prior to dispensing protein drops directly onto the interdigitated surfaces for biosensing purposes using the setup as shown in

Figure 3.

To examine the chemical profiling on the surface immediately after monolayer grafting, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) was performed using JASCO FT/IR-4700 spectrometerwith Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) detector that was cooled using liquid nitrogen during the analysis. Chemical signals from gold surfaces were detected with a diamond prism at an angle of 45° by carefully aligning the gold region to the center of the detection window. Due to the implications from various NH species after aptamer grafting, we restricted our analysis solely on the gold surface passivated with NHS monolayer and examined the range from 2600 to 3500 cm

-1 in order to elucidate the presence of aliphatic carbon (

Figure 4).

3. Results

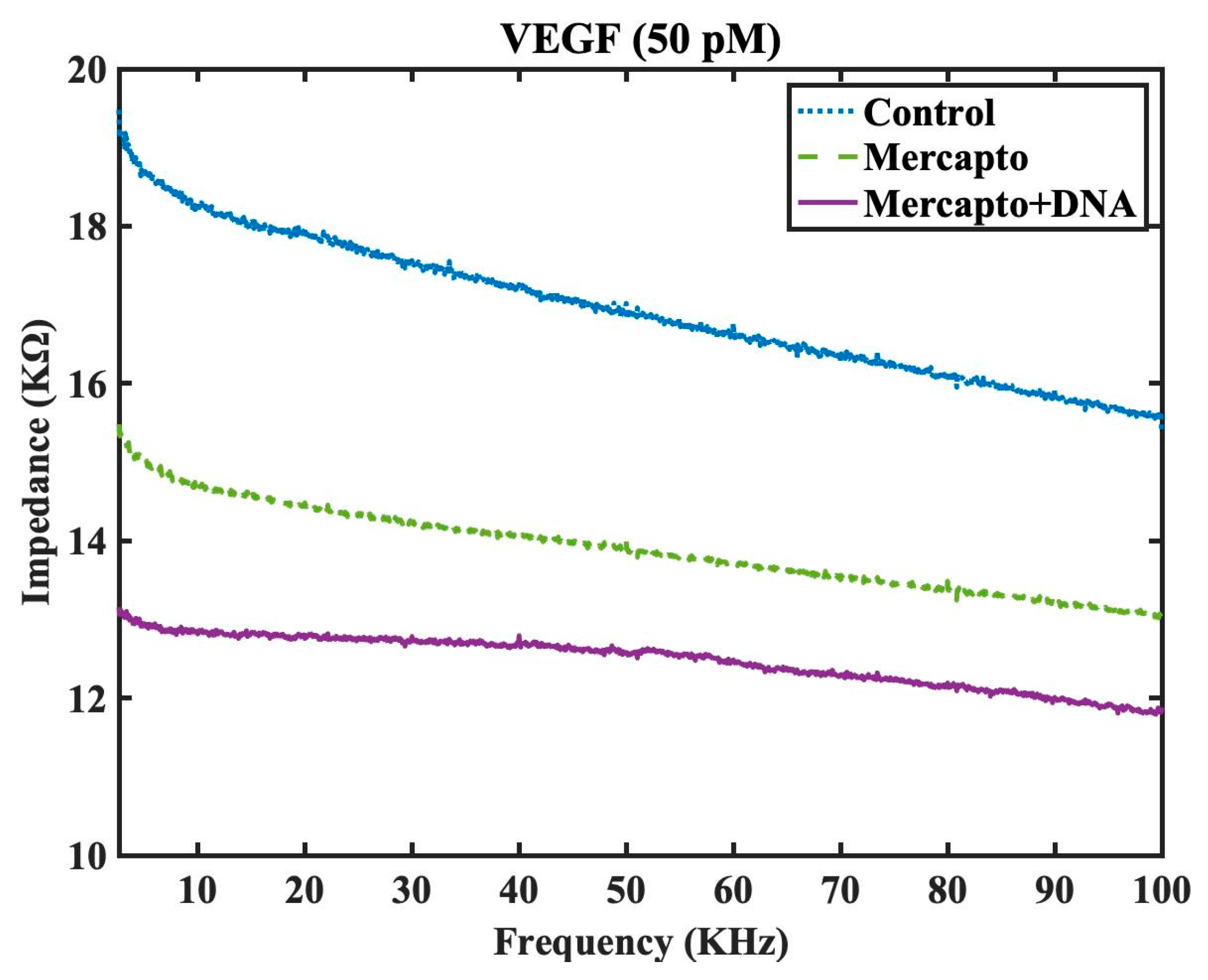

To examine the efficacy of surface chemistry modifications and DNA aptamer grafting for VEGF protein detection and selectivity, impedance spectra testing was conducted for VEGF at a concentration of 50 pM under three distinct conditions using simple drop aliquots to the surface of the interdigital electrode. The examined conditions were as follows: control (using the sensor without surface chemistry modification (control), mercapto functionalized monolayer and mercapto+DNA (utilizing the sensor with surface chemistry modification and DNA aptamer grafting). It was expected that the mercapto+DNA scenario would exhibit the lowest impedance in the spectra due to the capture of negatively charged VEGF protein by the functionalized sensor. The experimental results shown in

Figure 5 confirm that the functionalized sensor indeed exhibited the lowest impedance, while the unfunctionalized sensors without surface chemistry modification presents the highest impedance for VEGF detection among three scenarios. The detection was rapidly quick and this experiment demonstrates the effectiveness of the DNA aptamer grafted interdigitated sensor for rapid VEGF protein detection.

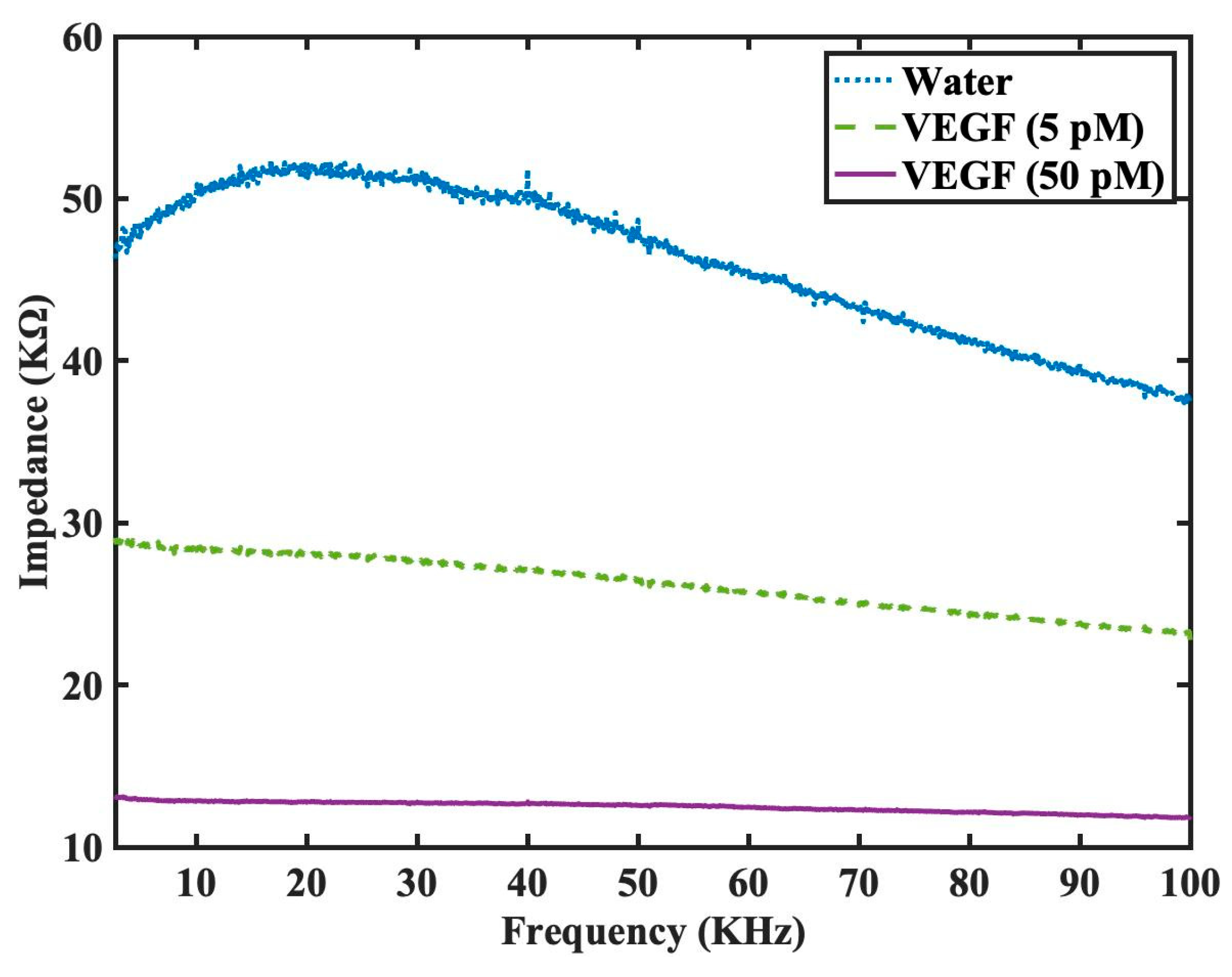

To further evaluate the effectiveness of functionalized sensor in VEGF detection, we also conducted further investigations onto the impedance spectra for the interdigitated sensor with mercapto functionalized monolayer and DNA aptamer grafting under three conditions. The examined conditions included water (adjusted to pH 7), VEGF at 5 pM (quantified to approximately 200 pg/ml), and VEGF at 50 pM. The detection using water serves as a control for the detection experiments and is hypothesized to exhibit the highest impedance among three conditions, while higher concentration of VEGF protein would result in lower impedance and the experimental results was as summarized in

Figure 6. It was subsequently observed that as the functionalized sensor could bind to more VEGF proteins under higher concentration, the negative charge in the protein would in turn modify the overall dielectric characteristics between the arms of interdigitated sensor, thus leading to greater reduction in the impedance spectra. We noticed that this quenching of the impedance was even noticeable for 5 pM when compared to water as our control while the quenching of the impedance was most profound for 50 pM and hence, we did not find the reason to increase the concentration further and concentrations beyond 50 pM as it was not thought to be clinically significant. Similarly, our device was unable to monitor change in impedance in a stable fashion for concentration below 5 pM and thus we did not attempt to reduce our concentration further.

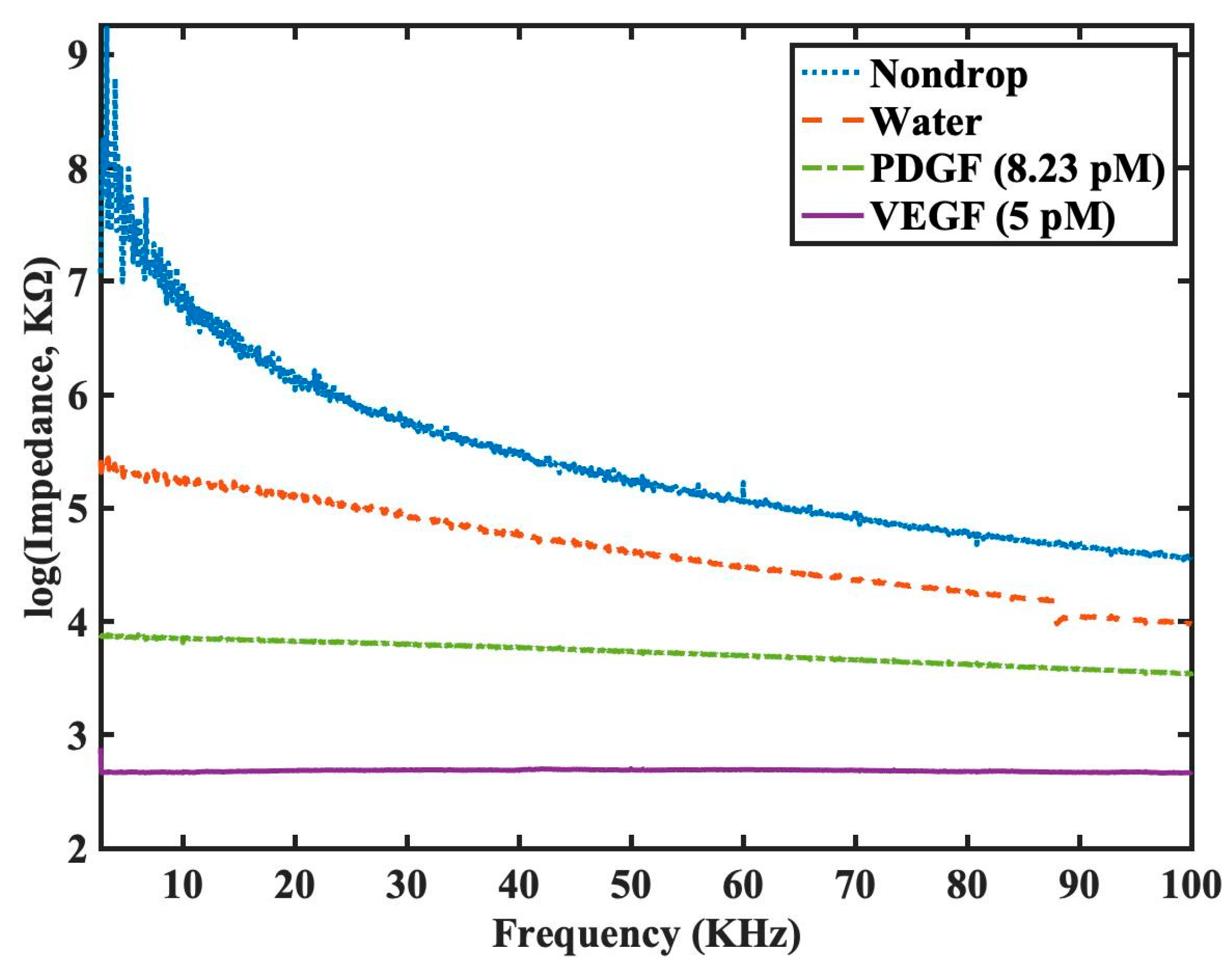

Next, our group had decided to test our sensor for the detection in the presence of non-specific 2

nd type of biomarker, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). It is important to note that both PDGF and VEGF are important signaling proteins involved in regulating cellular growth and angiogenesis and hence have significant clinical relevance. Both have distinct roles in physiological and pathological processes, and they target different receptors. PDGF is involved in cell growth and tissue repair, while VEGF is primarily responsible for promoting the growth of blood vessels [

27]. Hence it was in the author’s opinion that in the presence of PDGF, we will be able to evaluate if non-specific interference could influence the impedance outcome of work and this an importance consideration when performing using serum during clinical diagnosis. The impedance spectra were measured under four different conditions: no sample, water, PDGF at 8.23 pM (approximately 200pg/ml), and VEGF at 5 pM. Since the functionalized sensor is grafted with the DNA aptamer solely for the detection of VEGF protein, it is expected that the detected impedance for VEGF at 5 pM would be the lowest among the testing conditions. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 7, where the impedance values are presented in logarithmic scale due to the large dynamic range. From our data, we had shown that even at our lowest limit of VEGF at 5 pM, our biosensor was able to discern between different biomarkers and was highly sensitive in terms of selectivity and the results was highly encouraging.

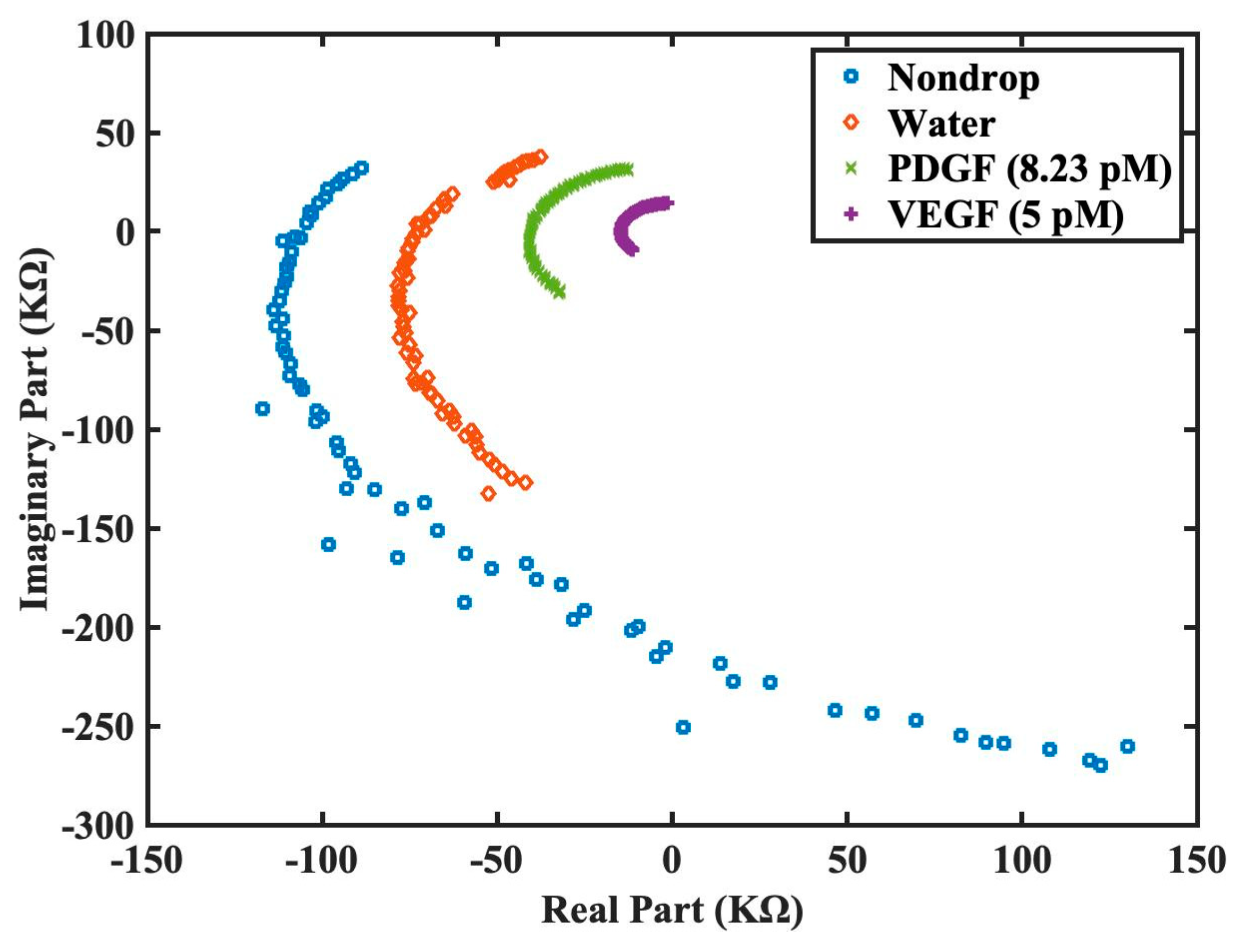

Thus, from

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the proposed functionalized sensor was experimentally confirmed to be effective in its function, sensitivity, and specificity on VEGF detection by impedance spectroscopy. To further enhance the visualization of the derived impedance spectrum in an intuitive manner, we had proposed an alternative presentation style in

Figure 8. This style presents the real and imaginary parts of the spectrum on

x and

y axes separately for each frequency.

Figure 8 utilizes the raw data from

Figure 7 without logarithmic scale. This illustration offers the advantages of intuitive comprehension and potential integration with machine learning techniques for intelligent VEGF detection.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated a highly cost-effective approach for detecting VEGF using impedance spectroscopy with the surface monolayer functionalized interdigitated sensor. Commercially available interdigitated sensors were modified through simple but precise surface chemistry and DNA aptamer was selected for VEGF protein detection. The platform for impedance spectroscopy, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, was fabricated and process of the surface chemistry modification and DNA aptamer grafting for VEGF detection was described and successfully accomplished (see

Figure 4). The experimental results as summarized in

Figure 5 further validate the VEGF detection capability of the proposed sensor.

In addition, sensitivity experiments have been conducted and functionalized sensor was shown possess ability to detect VEGF at a concentration of 5 pM, as illustrated in

Figure 6. In order to assess the specificity of the functionalized sensor in VEGF detection, we compared the performance with the detection of PDGF. The results as shown in

Figure 7 helped to verify that the functionalized sensor can specifically detect VEGF protein even at a low concentration of 5 pM. Finally, we also propose an alternative demonstration style for impedance spectra to enhance the intuitive visualization of the derived impedance spectrum, as depicted in

Figure 8. Furthermore, this approach holds the potential to integrate the machine learning techniques for intelligent VEGF detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D.L and Y.L.K.; methodology, Y.D.L., S.I.Z. and Y.L.K.; software, C.C.Y.; validation, C.C.Y., S.I.Z. and Y.L.K.; formal analysis, C.C.Y.; investigation, C.C.Y.; resources, Y.L.K.; data curation, C.C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.L. and Y.L.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.D.L. and Y.L.K.; visualization, Y.D.L., C.C.Y. and Y.L.K.; supervision, Y.D.L. and Y.L.K.; project administration, Y.D.L. and Y.L.K.; funding acquisition, Y.D.L. and Y.L.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.