1. Introduction

Cosmeceutical products are a topical combination of cosmetic and pharmaceutical in which biologically active ingredients to have medicinal or drug-like benefits to improve skin health [

1]. Due to the modern lifestyle and increasing beauty concerns, the beauty care industries are growing each year all over the world. To meet the demand of consumers, these industries are moving towards the unstoppable use of synthetic cosmetics and ingredients. Due to the ineffectiveness of synthetic ingredients, they may accumulate in skin layers and create toxicities and harm to normal skin health. According to Kerdudo et al. [

2], hydroxybenzoic acid esters (parabens), which are widely used in cosmetic formulations, were reported as harmful to the skin as well as causing an increased incidence of breast cancer and malignant melanoma. Phthalates, as an example, are commonly found in several cosmetic products that can cause DNA modifications and damage as proved in human sperm cells [

3]. Some of these chemicals can cause harmful effects in animal studies such as decreased sperm counts, altered pregnancy outcomes, male genitalia congenital disabilities, etc. [

4]. As a result, people have changed their preferences and opted for natural cosmetic products. Hence, the ever-expanding market for skincare products and continual search for an alternative natural ingredient has led to the development of a multitude of skin cosmetic formulations [

5].

Seaweeds, also known as macroalgae are eukaryotic, multicellular, macroscopic, marine photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms that are ubiquitously distributed along with all kinds of coasts from tropical regions to polar regions. It is normally inhabiting the intertidal and sub-tidal regions of coastal areas [

6]. Macroalgae are mainly classified into three major types, namely Brown algae (Ochrophyta phylum, Phaeophyceae class), red algae (Rhodophyta phylum), and green algae (Chlorophyta phylum). In which, green and red algae belong to the Plantae kingdom, whereas brown algae belong to the Chromista kingdom [

7]. Marine macroalgae are a rich source of structurally diverse biological active constituents. Algae contain ten times greater diversified phycocompounds than terrestrial plants. The biologically active constituents found in marine macroalgae have multiple activities, which allow them to be used as an active constituent in formulations. The utilization of macroalgae in cosmetic applications is based on their valuable bioactive compounds, such as carbohydrates, proteins, amino acids, lipids, fatty acids, phenolic compounds, pigments, vitamins, and minerals [

8,

9] Broad applications of marine macroalgae are based on valuable bioactive compounds and potential bioactivities. For the development of cosmetic formulations, seaweed-derived compounds have been given considerable importance.

There is a distinctive small brown alga by the name of

Padina boergesenii. It has rounded fronds and grows to a length and diameter of 4 to 6 cm (1.6 to 2.4 in). A fissured, bulbous holdfast provides support for thin, leafy, and flat fronds that have narrow or wide lobes. Typically, they are pale brown or tan in color with a moderate amount of calcification on the underside [

10,

11]. In general, the fronds are two or three cells thick, but the bases are usually three cells thick. There are many short hairs on the surface of the fronds, resulting in a matted appearance [

12].

Many previous research studies demonstrated the wide range of biological activities of seaweed-derived active molecules that can offer a variety of skin benefits. The aim of this study was to investigate the biochemical profile of Padina boergesenii, a marine macroalga, using various analytical techniques, including FTIR, GC-MS, HRLCMS-Q-TOF, pigment estimation, total phenol content, total protein content, antioxidant analysis, and tyrosinase inhibition assay. The study aimed to assess the potential of P. boergesenii as a natural cosmetic ingredient by exploring its bioactive constituents, elemental composition, amino acid composition, and its ability to improve skin health. The findings aimed to contribute to the understanding of P. boergesenii’s suitability for incorporation into seaweed-based cosmetic products and further encourage research and development in the cosmetics industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection, Transportation, and Storage of Brown Alga P. boergesenii

The fresh marine macroalgal sample of

Padina boergesenii was collected in separate sterile plastic bags containing seawater from the Beyt Dwarka (Bet Dwarka) seacoast, Western coast of Gujarat, India (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), and transported by maintaining it at 10 °C from the site to the laboratory. The identification of collected marine algae sample was done with taking help of Dr. Nilesh H. Joshi, at Fisheries Department, Junagadh Agriculture University, Okha, Gujarat, India.

2.2. FTIR Characterization for Functional Groups Analysis

FTIR analysis was carried out in an instrument model 3000 Hyperion Microscope with Vertex 80 FTIR System, Bruker, Germany. 5 mg of shed dried

P. boergesenii sample was mixed with FT-IR grade Potassium bromide (99% trace metal basis, Sigma-Aldrich, India) and mixed evenly to obtain a homogenized fine powder. This prepared powder was then kept in a mold and pressed mechanically for 30 s using a sterile spatula to form pellets. This pellet was shifted on the pan and proceeded for analysis. The scanning range of analysis at 400–4000 cm

−1 wavelength. Based on the peak values in the region of the IR spectrum, the functional groups of the compounds were separated [

13,

14].

2.3. Characterization of Phytocompounds by GCMS Analysis

The extract of

P. boergesenii was prepared by adding 500 g of shed dried finely ground powder in 89% ethanol at 70 °C by continuous hot percolation method in Soxhlet assembly. It was run for 6 h and then, the ethanolic extract

P. boergesenii was filtered and kept in a dry hot air oven (RDHO 80, REMI, Bengaluru, India) for 24 h at 40 °C which was used to evaporate the ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Bengaluru, India). The prepared extract was concentrated to dryness in a rotary vacuum evaporator (Sigma Scientific, Chennai, India) under reduced pressure (150 mbar) at 20 °C temperature. The obtained residues of algal extract were kept separately in airtight vessels and put in a deep freezer maintaining −20 °C (Esquire Biotech, Chennai, India). A Gas chromatogram (GC) was obtained, and the mass spectrum of each unknown obtained compound was compared with the spectrum of the known compounds stored in the NIST (National Institute Standard and Technology) library ver. 2005 [

15,

16,

17].

2.4. Fatty Acids Characterization by GCMS Analysis

100 g of the shed-dried finely ground powder of

P. boergesenii was extracted with 1000 mL 99.8% methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Bengaluru, India) in a flask for 72 h. Then, this mixture was filtered in a separate clean vessel. This process was repeated twice with the sample residues using a fresh methanol solvent. Following this, supernatants of this mixture are collected separately. The rotary vacuum evaporator (Sigma Scientific, Chennai, India) was used to separate the excess methanol solvent from the above mixtures and proceeded for further analysis. A gas chromatogram was obtained and the mass spectrum of each unknown compound was interpreted with the known data stored in the NIST library ver. 2005 [

18,

19].

2.5. Characterization of Phytocompounds by HRLCMS Q-TOF

The

P. boergesenii sample was first dried in a hot air oven at 40 °C for 24 h, then this dried alga was ground separately in a mechanical grinder to obtain a uniformly fine powder. 1 g of oven-dried

P. boergesenii sample was kept in a screw cap tube and added 10 mL of 2 M HCl (Hydrochloric acid) containing 1% phenol. Following this, the tube was closed under N

2 gas and kept the tubes in an electric oven (REMI, Maharashtra, India) at 80 °C for 3 h, afterward, allowing the tube to cool and its contents were vacuum filtered through Whatman filter paper grade 41. Following filtration, the filtrate was diluted to 25 mL of ultrapure water in a volumetric flask, separately and the resulting liquid sample was again membrane filtered to get the hydrolysate. Different types of phytocompounds present in

P. boergesenii were identified by analyzing samples with the HRLCMS QTOF technique [

20,

21].

2.6. Measurements of Different Amino Acids by HRLCMS

100 mg of shed dried finely ground powder of

P. boergesenii was weighed separately in different vessels. Mixed this weighed

P. boergesenii sample with 12 mL 6N HCl and heat sealed after filling with pure nitrogen gas. For hydrolysis purposes, put all the vessels in an electric hot air oven at 120 °C temperature for 16 h. Following this, the sample was removed carefully and filtered. After filtration, flash evaporation was done to eliminate traces of HCl. Use 0.05 N HCl to make a definite volume of the algal sample residues. This mixture was filtered through a Whatman filter paper (0.45 µ). The above hydrolyzed and filtrated

P. boergesenii was analyzed by HRLCMS method [

22,

23,

24].

2.7. Element Analysis by ICP-AES Technique

2.7.1. Digestion and Detection

For the analysis of different elements, standard analytical pure-grade reagents such as nitric acid (HNO3), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) hydrogen fluoride (HF), and hydrochloric acid (HCl) (Merck, Germany) was used for the whole experiment. All glass wares and plasticware were cleaned by soaking overnight in 10% HNO3 (ACS reagent, Sigma-Aldrich, India) and then rinsed again with deionized water before use.

2.7.2. Digestion and Detection

Add approximately 0.05 g of

P. boergesenii was weighed directly into the TFM-PTFE (second generation modified Polytetra-fluoro-ethylene-) vessels, to which the mixture of reagents (3 mL of HCl + 1 mL of HNO

3 + 1 mL of HF + 1 mL of H

2O

2) was added separately and the vessel was closed quickly. Following this, subject this prepared mixture into a microwave digester (Titan Microwave system, PerkinElmer, Thane, India) and sent the operational conditions and heating program in ICP Spectrometer (SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Germany) [

25,

26].

2.8. Determination of Pigments content

The pigment content in P. boergesenii was quantified in triplicate using various solvents (10 mL each) following established protocols. The selection of solvents was based on their specific affinity for each class of pigment. The sample was vortexed for 60 s at room temperature after the addition of the respective solvent, which was prepared fresh.

2.8.1. Quantification of Chlorophylls, Carotenoids, Fucoxanthin, Phycoerythrin, and Phycocyanin

To extract chlorophylls, 1 gm of

P. boergesenii sample was mixed with 100% methanol or 100% ethanol. Total carotenoids were extracted using methanol, while brown pigment fucoxanthin in brown algal species was extracted using a DMSO-water mixture (4:1, v/v). The red pigments, phycoerythrin, and phycocyanin were extracted using a phosphate buffer at pH 6.8. The prepared extract of

P. boergesenii were then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min, and the collected supernatant was subjected to another round of centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance values of the supernatants were measured thrice using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer at wavelengths corresponding to the maximum absorption of the pigments, as indicated in the equations below. The pigment content was determined by applying the absorbance values in the following formulas, based on standard methods. The content of each pigment was expressed as grams per gram (µg/mL) of macroalgae [

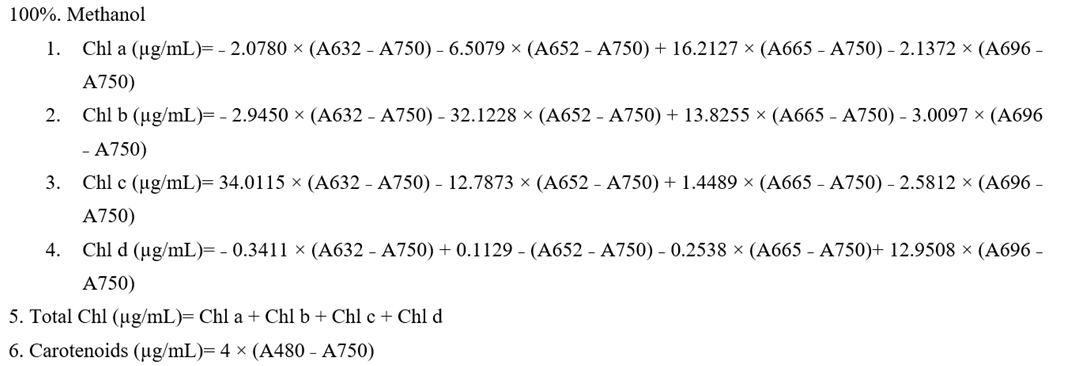

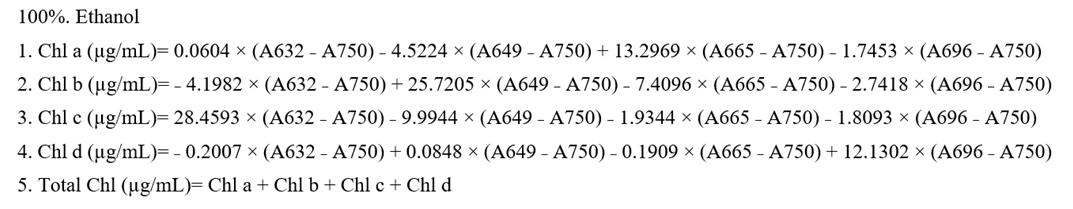

27].

Equations for estimation of Chlorophyll and Carotenoids

Equations for estimation of Fucoxanthin, Phycoerythrin and Phycocyanin

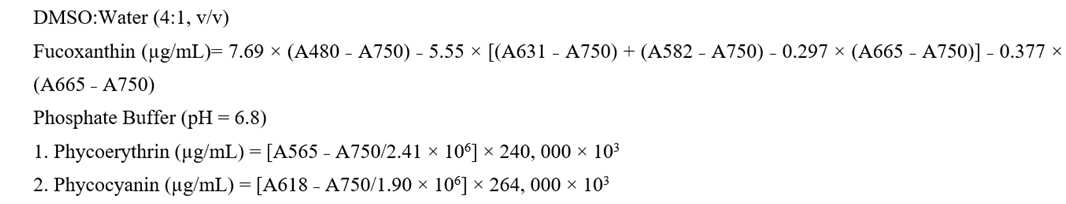

2.8.2. Estimation of Chlorophylls and Lycopene

The quantification of Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, and Lycopene followed the standard procedure described by Nagata and Yamashita (1992). Fresh

P. boergesenii weighing 100 mg was homogenized with 10 ml of an acetone-hexane mixture (2:3) for 120 seconds. To protect the sample from overheating, the

P. boergesenii sample was maintained in an ice-water bath during the homogenization process. Subsequently, the prepared homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at a temperature of 20 °C. The absorbance value was measured at wavelengths of 453 nm, 505 nm, 645 nm, and 663 nm using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer. The content of Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, and Lycopene was calculated using the following equations, and all values were expressed in milligrams per 100 milliliters (mg/100 mL) [

28].

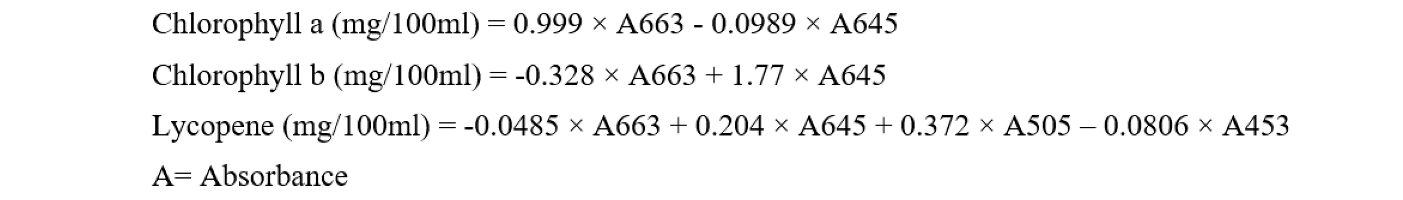

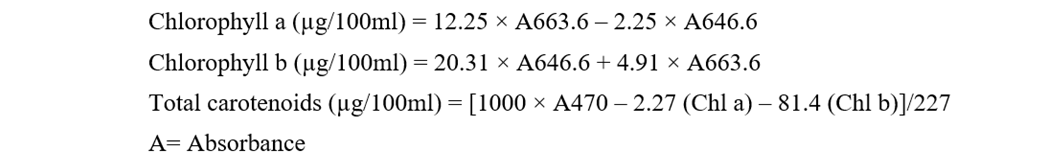

2.8.3. Estimation of Chlorophylls and Total Carotenoids

The determination of Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, and total carotenoids pigment content in

P. boergesenii followed the established method described by Yang et al. [

29]. The extraction process was conducted using the same method as previously mentioned. In this analysis, an acetone-water mixture (4:1) served as the solvent. The absorbance values were measured at specific wavelengths: 663.6 nm for Chlorophyll a, 646.6 nm for Chlorophyll b, and 470.0 nm for carotenoids. The content of these pigments was calculated using the following equations.

2.9. Analysis of Total Polyphenol Content

The spectrophotometric method was used to measure total polyphenol content in

P. boergesenii. In this assay, Gallic acid was used as a standard (50 µg/mL). First, add 50 mg of

P. boergesenii sample separately dissolved in 0.5 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), followed by adding demineralized water up to the limit of a 5.0-mL volumetric flask to make final sample concentration 1 g/100 mL. Carefully pipette 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 ml of the prepared standard gallic acid solution (50 µg/mL) in each tube and bring all the tubes to make a final volume 1 mL by adding the appropriate amount of distilled water. In the same way, take different aliquots of

P. boergesenii sample and add distilled water to make total volume 1 mL. Following this, add 5.0 mL of 1/10 dilution of Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) reagent in each tube. Afterwards, add 4.0 mL of a 7.5% sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3) solution each above tubes. Then, these tubes were kept to stand at room temperature for 1 h. After one hour incubation, read absorbance value of all the tubes at 762 nm against deionized water. The concentration of polyphenol in

P. boergesenii was measured from a standard curve of gallic acid by taking concentration range from 10 to 50 μg/mL. On a sheet of graph paper, construct A762 (y axis) vs. concentration of Gallic acid (x axis) graph. Label the x axis in a microgram/ml of Gallic acid. This is called a standard graph. Plot the absorbance values of unknown algal solution on the standard graph and find out the corresponding values of total phenol concentration of total phenol in

P. boergesenii [

30].

2.10. Estimation of Total Protein

The determination of total protein content was conducted using the following method. Standard solutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) were prepared by pipetting precise volumes (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mL) of a 100 µg/mL BSA solution into separate labelled test tubes. The test tubes were brought to a total volume of 1 mL by adding the appropriate amount of phosphate buffer. Similarly, different aliquots (0.5, 0.8, 1.0 mL) of

P. boergesenii sample were taken and adjusted to a total volume of 1 mL to achieve a sample concentration of 1%. Next, 5.0 mL of Bradford reagent was added to each test tube containing the BSA standard solutions and the algae samples, followed by thorough mixing after each addition. The set of tubes was then incubated in a dark area for 10 min. After the incubation period, the absorbance values were measured at 595 nm using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer. A graph was constructed on graph paper, plotting A595 (y-axis) against the concentration of BSA (x-axis). The corresponding values of protein concentration for

P. boergesenii was determined by plotting the absorbance values of the

P. boergesenii on the standard graph. The protein concentration values were multiplied by the appropriate dilution factor, and the average was calculated to obtain the final value of the unknown protein concentration [

31].

2.11. In vitro Antioxidant Analysis using the DPPH Method

The antioxidant activity of methanol and ethanol extract obtained from

P. boergesenii was evaluated based on their ability to scavenge the stable DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) free radical [

32]. Stock solution of

P. boergesenii sample was prepared at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL and subsequently diluted to final concentrations of 100 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, 400 μg/mL, 600 μg/mL, and 800 μg/mL. For the analysis, 3.8 mL of a 50 μM methanolic solution of DPPH was added to 0.2 mL of each algal solution individually. The mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of these mixtures was measured at 517 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A control sample without the addition of

P. boergesenii sample or standard was quickly measured at 0 minutes. The inhibition percentage (I%) was calculated using the following formula. Additionally, the IC

50 value, which represents the concentration at which 50% inhibition is achieved, was determined for

P. boergesenii. The IC

50 value was obtained by plotting the inhibition percentage (I%) against the different concentrations of the selected

P. boergesenii sample.

where: A_control is the absorbance of the control sample A_sample is the absorbance of the sample or standard. Through this assay, the IC

50 value was determined as a measure of the antioxidant activity of the tested sample.

2.12. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

A modified Dopachrome method [

33] using L-DOPA substrate was employed to assess the tyrosinase inhibition activity of the

P. boergesenii’s extract. Kojic acid, a known tyrosinase inhibitor, was used as a reference standard and both the extracts and Kojic acid were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. The assay was conducted using a 96-well microplate, and absorbance values were measured at 475 nm using an ELISA microplate reader. Each well was labeled appropriately, and 40 μL of the prepared

P. boergesenii extract in DMSO was transferred to the respective labeled well. Subsequently, 80 μL of phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 40 μL of tyrosinase enzyme, and 40 μL of L-DOPA were added to each well. A blank sample, which included all the aforementioned reagents except for L-DOPA, was prepared for comparison with each algae sample. Additionally, Kojic acid was included as a reference standard inhibitor of tyrosinase for the purpose of comparative analysis. The percentage inhibition of tyrosinase was calculated using the following formula:

where: A_blank is the absorbance of the blank sample A_sample is the absorbance of the sample or standard. Through this assay, the inhibitory activity of

P. boergesenii on tyrosinase was determined, and Kojic acid was used as a reference to assess the relative inhibition levels.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Collection of Brown Alga P. boergesenii

India is among the 12 countries with the most extensive variety of living species on earth, and it boasts the world’s longest coastline, measuring approximately 8,100 km. One of India’s states, Gujarat, has a coastline that extends over 1,600 km and features diverse topography, geomorphology, coastal processes, and river discharge into the Arabian Sea. The Indian Sea coast is home to more than 844 species of seaweed, while Gujarat’s coast has more than 198 species of seaweed. Among the species of macroalgae found in this region,

Padina boergesenii (

Table 1) is prevalent during the winter and summer seasons and persists for longer durations than other algal species. It thrives in temperatures ranging from 16 to 25 °C, in salinity levels ranging from 9 to 13‰, and in intertidal pools along the upper to mid-region of the coast. This algal species is found attached to sandy or muddy benthic areas and may form groups on the water surface. Beyt Dwarka sea coast (

Figure 1), located on the western coast of Gujarat, is a suitable habitat for

P. boergesenii, making it an ideal location for this study. Marine macroalgae contain bioactive compounds in greater concentrations than their terrestrial counterparts and can be used in diverse applications, including medicine, cosmetics, food, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

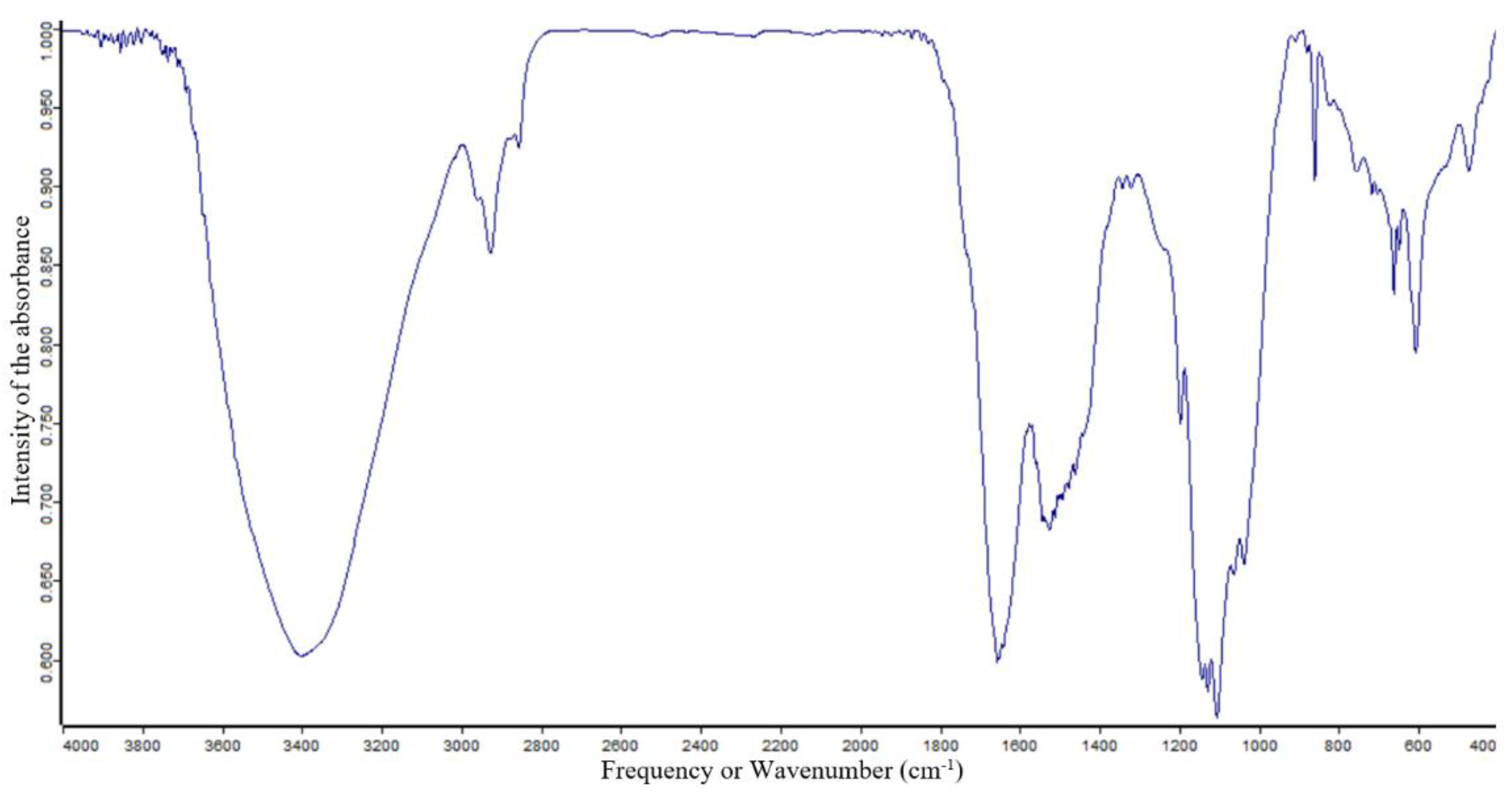

3.2. FTIR Characterization for Functional Groups Analysis

The functional groups of the active compounds in

P. boergesenii were characterized using FTIR analysis, which involved assessing the peak values, frequencies, intensities, and assigning bands to specific functional groups. The FTIR spectrum of the studied sample is depicted in

Figure 3, and the corresponding values for selected algae are presented in

Table 2. In the FTIR analysis of

Padina boergesenii, prominent bands were observed at frequencies of 604, 659, 751, 1038, 1099, 1126, 1196, 1320, 1343, 1521, 1648, 1656, 1873, 2859, 2925, 2959, 3404, and 3686 cm

−1. These bands were attributed to specific functional groups, including C-O, C-H, S=O, C-Br, C-Cl, C=C, S=O, N-H, C-F, C=N, C-N, O-H, indicating the presence of halo compounds, 1,2-disubstituted compounds, monosubstituted compounds, sulfoxides, fluoro compounds, amines, aliphatic ethers, secondary alcohols, tertiary alcohols, esters, aromatic amines, phenols, sulfonates, sulphonamides, sulfonic acids, sulfones, imines/oximes, alkenes, conjugated alkenes, carboxylic acids, amine salts, and alkanes within the

P. boergesenii extract.

These identified functional groups play crucial roles in providing various skin benefits and can be utilized in cosmetic formulations. For instance, alcohols, such as secondary and tertiary alcohols, are known for their potential moisturizing and emollient properties, contributing to improved skin hydration and texture. Esters, carboxylic acids, and phenols may have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which can support overall skin health and combat signs of aging. Amines and sulfonic acids might exhibit antimicrobial properties, helping to protect the skin against bacterial and fungal infections. Furthermore, the presence of halo compounds and fluoro compounds suggests potential photoprotective effects, aiding in shielding the skin from harmful UV radiation. The FTIR analysis provides valuable insights into the functional groups present in P. boergesenii, highlighting their significance in skincare and cosmetic applications. Further exploration and understanding of the specific contributions of these functional groups can lead to the development of innovative and effective cosmetic formulations targeting moisturization, anti-aging, photoprotection, and antimicrobial properties.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrums of selected marine algae by KBr pellet method. B: Padina boergesenii.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrums of selected marine algae by KBr pellet method. B: Padina boergesenii.

Table 2.

Characterization of functional groups in P. boergesenii by FTIR analysis.

Table 2.

Characterization of functional groups in P. boergesenii by FTIR analysis.

| Frequency (cm−1) |

Intensity |

Band assignments |

Functional group |

| 604.94 |

S |

C-Cl stretch |

Halo compound |

| S |

C-Br stretch |

Halo compound |

| 659.08 |

S |

C-Br stretch |

Halo compound |

| S |

C-Cl stretch |

Halo compound |

| 751.88 |

S |

C-Cl stretch |

Halo compound |

| S |

C-H bend |

1,2-Disubstituted |

| S |

C-H bend |

Monosubstituted |

| 1038.02 |

S |

S=O stretch |

Sulfoxide |

| S |

C-F stretch |

Fluoro compound |

| M |

C-N stretch |

Amine |

| 1099.89 |

S |

C-F starch |

Fluoro compound |

| S |

C-O starch |

Aliphatic ether |

| S |

C-O starch |

Secondary alcohol |

| M |

C-N stretch |

Amine |

| 1126.96 |

S |

C-F stretch |

Fluoro compound |

| S |

C-O stretch |

Tertiary alcohol |

| S |

C-O stretch |

Aliphatic ether |

| M |

C-N starch |

Amine |

| 1196.56 |

S |

C-F stretch |

Fluoro compound |

| S |

C-O stretch |

Tertiary alcohol |

| S |

C-O stretch |

Ester |

| M |

C-N stretch |

Amine |

| 1320.30 |

S |

C-F stretch |

Fluoro compound |

| S |

C-N stretch |

Aromatic amine |

| S |

S=O stretch |

Sulfone |

| M |

O-H bend |

Phenol |

| 1343.50 |

S |

C-F Stretch |

Fluoro compound |

| S |

S=O Stretch |

Sulfonate |

| S |

S=O Stretch |

Sulfonamide |

| S |

S=O Stretch |

Sulfonic acid |

| S |

S=O Stretch |

Sulfone |

| M |

O-H bend |

Phenol |

| 1521.37 |

S |

N-O stretch |

Nitro compound |

| 1648.98 |

M |

C=N Stretch |

Imine/Oxime |

| M |

C=C stretch |

Alkene (Disubstituted) |

| M |

C=C stretch |

Alkene |

| M |

C=C stretch |

Conjugated alkene |

| M |

N-H bend |

Amine |

| M |

C=C stretch |

Cyclic alkene |

| S |

C=C Stretch |

Alkene (Mono substituted) |

| 1656.71 |

M |

C=C stretch |

Alkene (Disubstituted) |

| M |

C=N Stretch |

Imine/Oxime |

| M |

C=C stretch |

Alkene (Vinyldehyd) |

| W |

C-H bend |

Aromatic compound |

| 1873.25 |

W |

C-H bend |

Aromatic compound |

| 2859.29 |

SB |

O-H stretch |

Carboxylic acid |

| WB |

O-H stretch |

Alcohol |

| SB |

N-H Stretch |

Amine salt |

| M |

C-H stretch |

Alkane |

| 2925.03 |

SB |

O-H stretch |

Carboxylic acid |

| WB |

O-H stretch |

Alcohol |

| SB |

N-H Stretch |

Amine salt |

| M |

C-H stretch |

Alkane |

| 2959.83 |

SB |

O-H stretch |

Carboxylic acid |

| WB |

O-H stretch |

Alcohol |

| SB |

N-H Stretch |

Amine salt |

| M |

C-H stretch |

Alkane |

| 3404.51 |

SB |

O-H stretch |

Alcohol |

| 3686.79 |

MS |

O-H Stretch |

Alcohol |

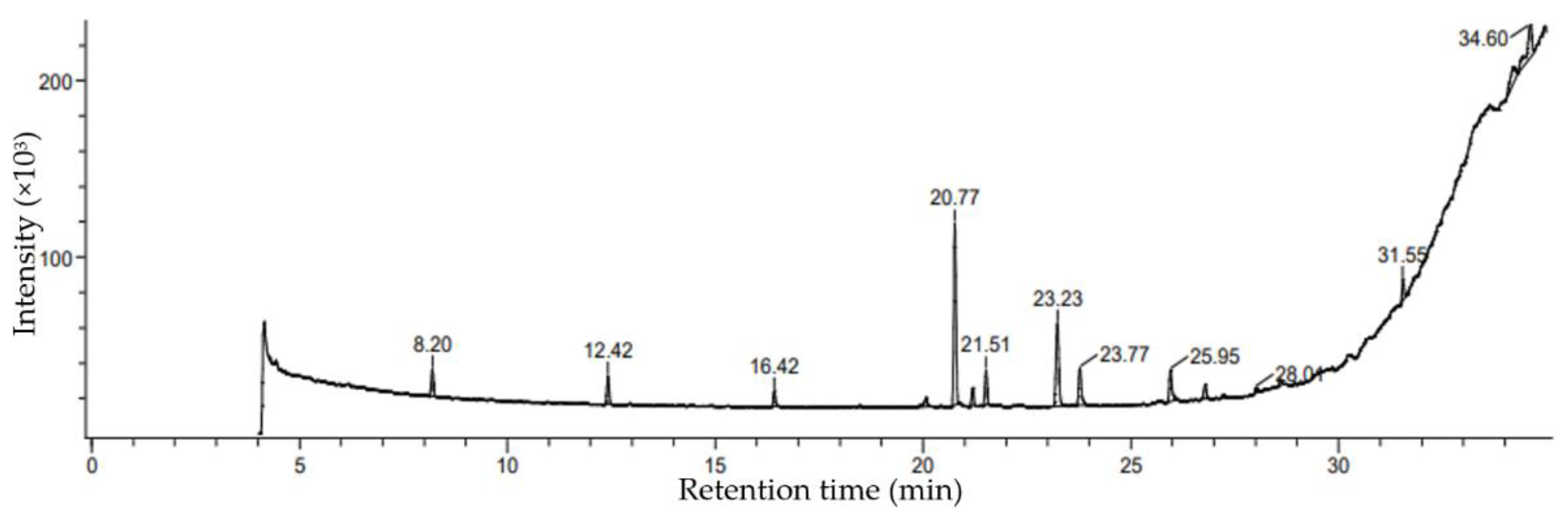

3.3. Fatty Acids Characterization by GC MS Analysis

Based on percentage peak area, retention time (in minutes), molecular formula and molecular weight, different compounds were characterized in methanolic extract of selected marine macroalgal species. Gas chromatograms of selected macroalga with different peaks are illustrated in

Figure 5. Chemical information of different obtained compounds in GCMS analysis tabulated in

Table 4.

The methanolic extract of P. boergesenii revealed several compounds through GC-MS analysis, each with its own potential role in skincare and cosmetics. Among the identified compounds, 9-Octadecenal exhibited the highest percentage peak area (34.79%) at a retention time of 2.36 min. This compound belongs to the class of fatty aldehydes and is known for its pleasant aroma, which could be utilized in cosmetic products for fragrance purposes. In terms of fatty acids, P. boergesenii contains Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, palmitic acid, and palmitic acid vinyl ester, which are saturated fatty acids. These fatty acids can provide moisturizing and emollient effects, helping to hydrate and soften the skin. On the other hand, the unsaturated fatty acids present in P. boergesenii include cis-9-Octadecenoic acid, 9-Dodecenoic acid methyl ester [E]-, and Alkynyl Stearic Acid. Unsaturated fatty acids are known for their skin-nourishing properties and can contribute to maintaining the skin’s barrier function. Other noteworthy compounds found in P. boergesenii include Hexahydrofarnesol, a fatty alcohol that can provide hydration and soothing benefits to the skin. Fatty aldehydes, such as 9-Octadecenal and (z)-9,17-octadecadienal, may contribute to the sensory experience and aroma of cosmetic products.

Phytosterols like 29-Methyliso Fucosterol are bioactive compounds with potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Terpenes such as Phytol and Patchoulol are known for their antimicrobial properties and can be beneficial in formulations targeting acne or other skin concerns. Cyclic organic compounds like 1,2,4-Trioxolane, 3,5-dipropyl- can have antioxidant and skin-soothing effects. Hydrocarbon derivatives like 1,1′-Bicyclopentyl, 2-hexadecyl-, and 1,4-Eicosadiene offer potential benefits as skin-conditioning agents, providing moisture retention and improving the overall appearance of the skin. These individual compounds found in P. boergesenii present various opportunities for formulators to develop skincare products with targeted benefits. The saturated and unsaturated fatty acids contribute to moisturization and skin barrier support, while the fatty aldehydes, fatty alcohols, and other compounds offer sensory enhancements and specific skincare properties. By harnessing the potential of these compounds, cosmetic formulations can be tailored to address specific skin concerns and provide an enjoyable and effective skincare experience. Further research and exploration of these compounds will unlock their full potential and expand their application in the cosmetics industry.

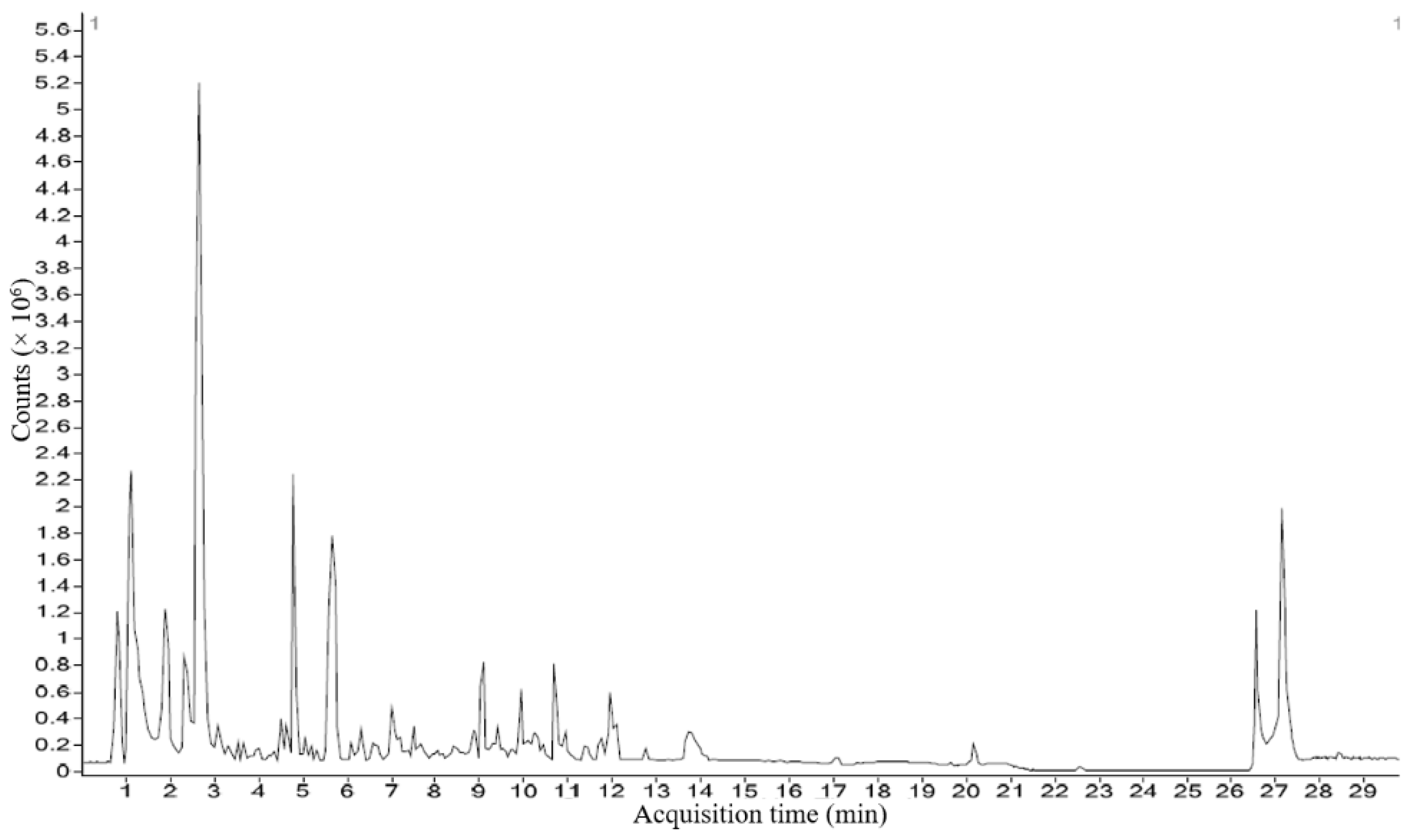

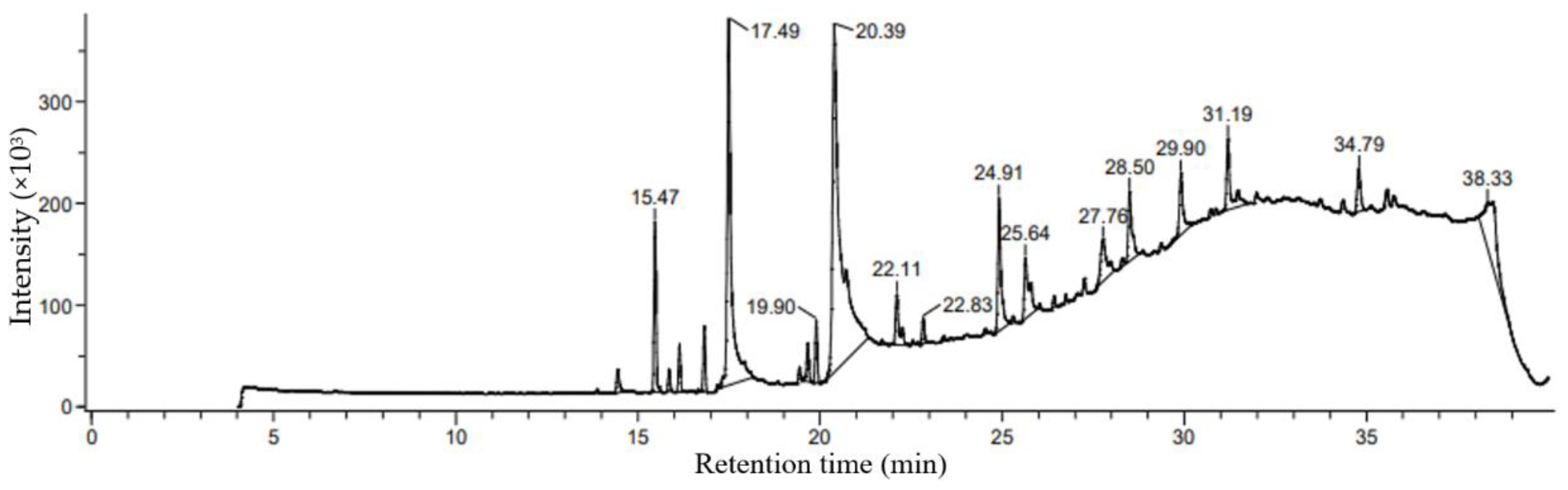

3.4. Characterization of Phytocompounds by HRLCMS Q-TOF

An analysis of methanolic extract from selected marine macroalga revealed different types of phycocompounds with different values of percentage peak area and retention time. In characterization study, liquid chromatograms (LC) for screened alga obtained by HRLCMS analysis is illustrated in

Figure 6. The obtained different types of phycocompounds and their details for this brown alga were tabulated in

Table 5. Unknown compounds identified and characterized by comparing obtained values of unknown compounds with standard available data in the library.

In P. boergesenii, the presence of Azuleno(5,6-c)furan-1(3H)-one, 4,4a,5,6,7,7a,8,9-octahydro-3,4,8-trihydroxy-6,6,8-trimethyl-, and 18-Nor-4(19),8,11,13abietatetraene; 6-Oxocativic acid suggests anti-inflammatory properties, making them beneficial for soothing skin irritations and reducing redness. The compound 2,6-Dimethoxy-4-(1-propenyl)phenol, a phenolic compound, exhibits potent antioxidant activity, protecting the skin from oxidative stress and combating signs of aging. Fatty acid derivatives, such as 8-Amino Caprylic acid, N-linoleoyl taurine, and Bolekic acid, offer moisturizing and nourishing effects on the skin. These compounds can help maintain skin hydration, improve skin texture, and support overall skin health. Peptide molecules, including L-NIO, Lys Gly, Pro Pro His, Gln Phe Lys, Tyr Ile Pro, S-Decyl GSH, Lys Met Lys, and N-Formyl-norleucyl-leucylphenylalanyl-methylester, possess diverse skincare benefits. They may stimulate collagen synthesis, improve skin elasticity, and contribute to anti-aging effects. These peptides can be incorporated into skincare formulations targeting wrinkle reduction and improving skin firmness. Phycocompounds such as Ni-azirinin, a carbohydrate derivative, hold potential for moisturization and skin conditioning. Cryptopleurine, an alkaloid, may exhibit antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects, making it useful in skincare products targeting acne or skin inflammation. The presence of LG 100268, a member of the Vitamin B Complex, suggests potential benefits in supporting overall skin health, cellular functions, and rejuvenation. Terpenoids, like Phytol and Patchoulol, offer potential antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, which can help protect the skin from environmental stressors and maintain a healthy complexion. By harnessing the potential benefits of these individual compounds, skincare formulations can be developed to target specific skin concerns, such as aging, dryness, inflammation, and microbial imbalances. Further research and studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms of action and determine optimal concentrations for these compounds in cosmetic applications.

Figure 6.

Liquid Chromatogram (LC) for phycocompounds’ characterization from selected macroalga Padina boergesenii by HRLCMS-QTOF. X-axis: Acquisition time (minutes); Y-axis: Counts (×106).

Figure 6.

Liquid Chromatogram (LC) for phycocompounds’ characterization from selected macroalga Padina boergesenii by HRLCMS-QTOF. X-axis: Acquisition time (minutes); Y-axis: Counts (×106).

Table 5.

Chemical information of phycocompounds identified in P. boergesenii by HRLCMS technique.

Table 5.

Chemical information of phycocompounds identified in P. boergesenii by HRLCMS technique.

| Phytocompound |

Class of compound |

Formula |

Retention time (min) |

Mass (Da) |

Abundance |

Hits (DB) |

| 8-Hydroxy-2chlorodibenzofuran |

organochlorine compound |

C12H7ClO2

|

0.828 |

218.0135 |

828077 |

2 |

| Sulfabenzamide |

Sulfur Compounds (sulfonamide) |

C13H12N2O3S |

0.829 |

276.0549 |

- |

4 |

| 3-((2-Methyl-3-furyl)sulfanyl)-2-butanone |

aryl sulfide (organosulfur compound) |

C9H12O2S |

0.897 |

184.0573 |

631461 |

7 |

| 8-Amino Caprylic acid |

omega-amino fatty acid (Carboxylic Acids) |

C8H17NO2

|

1.175 |

159.1249 |

1110887 |

6 |

| L-NIO |

Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins |

C7H15N3O2

|

1.272 |

173.1157 |

449684 |

7 |

| Lys Gly |

Dipeptide |

C8H17N3O3

|

1.318 |

203.1262 |

189239 |

10 |

| Pirbuterol |

Amino Alcohols (Ethanolamines) |

C12H20N2O3

|

1.319 |

240.146 |

- |

10 |

| N-Guanyl Histamine |

Amines |

C6H11N5

|

1.329 |

153.1014 |

143807 |

6 |

| Pro Pro His |

Pro-Pro-His is an oligopeptide. |

C16H23N5O4

|

1.894 |

349.1722 |

- |

10 |

| MeIQx |

Quinoxalines (aromatic amine) |

C11H11N5

|

2.375 |

213.1016 |

208953 |

10 |

| Salsolidine |

Isoquinolines (organic heterocyclic compound) |

C12H17NO2

|

2.937 |

207.1253 |

- |

10 |

| Isopentenyladenine-9-Glucoside |

organic heterocyclic compound(aminopurine) |

C17H25N5O4

|

3.179 |

363.1882 |

- |

10 |

| 2-Amino-1,7,9trimethylimidazo [4,5g]quinoxaline |

Heterocyclic Compounds, 2-Ring(Quinoxalines) |

C12H13N5

|

3.408 |

227.1171 |

136941 |

7 |

| Niazirinin |

carbohydrates and carbohydrate derivatives |

C16H19NO6

|

3.831 |

321.1201 |

116378 |

10 |

| Cryptopleurine |

Alkaloids |

C24H27NO3

|

3.88 |

377.2028 |

92057 |

10 |

| beta-Butoxyethyl nicotinate |

an aromatic carboxylic acid and a member of pyridines. |

C12H17NO3

|

3.964 |

223.12 |

104913 |

7 |

| LG 100268 |

Vitamin B Complex (Nicotinic Acids) |

C24H29NO2

|

4.033 |

363.2243 |

177426 |

7 |

| 2-(3′-Methylthio)propyl malic acid |

Alcohol |

C8H14O5S |

4.169 |

222.0578 |

92654 |

10 |

| Gln Phe Lys |

peptide (organic amino compound) |

C20H31N5O5

|

4.387 |

421.2295 |

146961 |

10 |

| N-linoleoyl taurine |

fatty amide (fatty acid derivative) |

C20H37NO4S |

4.6 |

387.2453 |

149019 |

10 |

| Tyr Ile Pro |

Peptide |

C20H29N3O5

|

4.632 |

391.2192 |

268855 |

10 |

| S-Decyl GSH |

Peptide |

C20H37N3O6S |

5.096 |

447.245 |

79144 |

5 |

| ORG 20599 |

Steroids (Pregnanediones) |

C25H40ClNO3

|

5.171 |

437.2696 |

6034 |

10 |

| Nafronyl |

Naphthalenes (benzenoid aromatic compound) |

C24H33NO3

|

5.27 |

383.2521 |

82233 |

7 |

| Lys Met Lys |

Oligopeptide |

C17H35N5O4S |

5.533 |

405.2348 |

156109 |

7 |

| Benzenemethanol, 2-(2hydroxypropoxy)-3-methyl- |

aromatic ether |

C11H16O3

|

5.68 |

196.109 |

719286 |

10 |

| Acetyl Lycopsamine |

Pyrrolizines (organic heterocyclic compound) |

C17H27NO6

|

5.791 |

341.1862 |

215252 |

10 |

| Benzenemethanol, 2-(2hydroxypropoxy)-3-methyl- |

aromatic ether |

C11H16O3

|

6.022 |

196.1092 |

130269 |

10 |

| 2,6-Dimethoxy-4-(1propenyl)phenol |

phenols |

C11H14O3

|

6.247 |

194.0938 |

149475 |

10 |

| Azuleno(5,6-c)furan-1(3H)-one, 4,4a,5,6,7,7a,8,9-octahydro-3,4,8-trihydroxy-6,6,8-trimethyl- |

Terpenoids (Sesquiterpenoids) |

C15H22O5

|

6.251 |

282.1453 |

113097 |

10 |

| Hericerin |

Amides (Lactams) |

C27H33NO3

|

6.316 |

419.2504 |

325331 |

5 |

| Di-n-pentyl phthalate |

phthalate ester (Phthalic Acids) |

C18H26O4

|

6.811 |

306.1819 |

155711 |

7 |

| N-Formyl-norleucyl-leucylphenylalanyl-methylester |

peptide |

C23H35N3O5

|

7.036 |

433.2662 |

476213 |

2 |

| 2,4,6-Trimethyl-4-phenyl-1,3 dioxane |

Dioxanes |

C13H18O2

|

7.158 |

206.13 |

240568 |

10 |

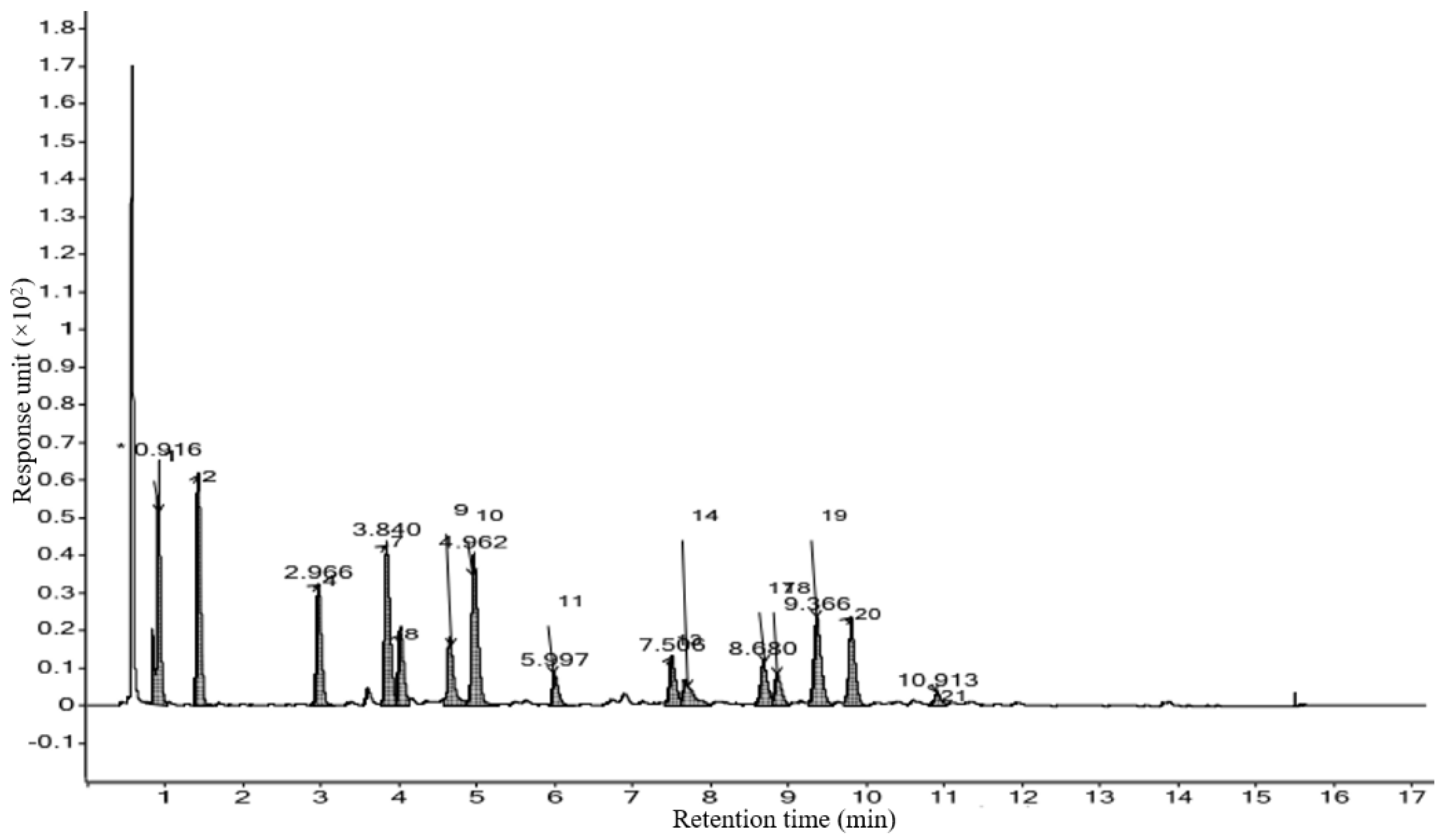

3.5. Measurements of Different Amino Acids by HRLCMS

Total 21 different types of amino acids were measured in chosen marine macroalga by HR LCMS-QTOF technique. Liquid chromatograms (LC) showing peaks of different amino acids in

Padina boergesenii alga which is illustrated in

Figure 7 and its content tabulated in

Table 6. In the present study,

P. boergesenii revealed a good amount of different amino acids Likewise,

P. boergesenii showed more than 500 nmol/mL content of Asp, Glu, Ala, Gly, Leu, Hyp, Ser and Thr. Content of amino acids were found in the following descending order (in nmol/ml): In

P. boergesenii, Asp > Glu > Ala > Gly > Leu > Hyp > Ser > Thr > Arg > Phe > Val > Lys > Met > Ile > Tyr.

Many previous research studies suggested skin beneficial actions of amino acids such as antioxidant anti-inflammatory, photoprotection, anti-wrinkle, moisturization, anti-elastase, antioxidant and other skin health promoting benefits [

41]. Among different amino acids, Proline, Glycine and Leucine found abundantly in collagen as well as lysine, Histidine and arginine are the three most common useful amino acids for skin care preparations. Likewise, a combination of arginine and lysine noted for its skin healing benefit while the combination of Leucine and Proline reported for repairing skin wrinkles [

42]. Moreover, Lysine plays an important functional role in elastin and collagen [

43]. Moreover, Lysine proved beneficial for preventing acne and cold sore. Choi et al. [

44] showed the role of tripeptide containing histidine and lysine for skin moisturization in skin care formulation. The synthesis of dermal collagen is considerably stimulated by Leucine, Isoleucine, Arginine, Glycine, Proline and Valine in hairless mice against UV damaging effects [

45]. Mixing Leucine with Glycine and Proline found useful for the repairing of skin wrinkles [

46]. On the faces of Japanese women, skin elasticity in a Crow’s feet lines was found to have improved after topical treatment of a Proline derivative [

46]. As a moisturizing agent, Alanine and Serine found useful in skin care product preparation and played a greater role in water retention in the stratum corneum layers. Yamane et al. [

47] showed the role of Isoleucine and Leucine in collagen synthesis of the skin. Facial atopic eczema treated by Isoleucine containing ceramide-based emollient cream formula [

48]. Aromatic amino acids, Tyrosine and Phenylalanine play an important role in melanin synthesis as a precursor. It is the main skin cutaneous pigment that provides protection against harmful sunlight containing UV rays and protects against DNA damage and skin cancers [

49]. Moreover, Tyrosine and Phenylalanine were found to play an important role in melanin synthesis process [

50]. Sulfur containing amino acid, methionine can also be needed in antiacne, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits [

51]. Besides, Serine and Threonine remain useful in moisture regulation in the stratum corneum. Moreover, Proline and Glycine amino acids are not only present as components in collagen but also work as a regulator of its synthesis [

52].

3.6. Element Analysis By ICP-AES Technique

Marine macroalgae are highly rich in different mineral elements. These marine algae derived minerals can be applied in skin cosmetic benefits. Among measured minerals, Silicon, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium and Iron are found to be major in amount in studied macroalgae species. The present study suggested that the Silicon (Si) was found to be the highest whereas Copper (Cu) remained at the lowest in amount in selected sample. Total ten elements and its measured concentration (%) in each alga tabulated in

Table 7. The percentage of minerals in selected macroalgae as follow in decreasing order (in %): In

P. boergesenii, Silicon > Calcium > Potassium > Magnesium > Iron > Sodium > Boron > Zinc > Copper.

Many research studies reported the beneficial actions of minerals in skin health promoting benefits. Calcium played its important role in hemostasis as well as in key regulation of epithelialization which is significantly noteworthy for differentiation of basal keratinocytes to corneocytes [

53]. Besides, Calcium (Ca

++) was found to be a key modulator in keratinocytes locomotion and promoter of wound healing in an in vivo study. For maintenance of cell membrane potential, Sodium and Potassium demonstrated beneficial roles at cellular and extracellular levels as electrolytes and osmolytes. Regarding skin benefits, formulations prepared from the Dead Sea salts containing magnesium found useful for skin nourishment [

54]. Denda et al. [

55] reported the skin repairing role of Calcium and Magnesium salts. In the experiment, reduction in the number of Langerhans cells in the epidermis as well as antigen presenting activity in the skin reported in topical treatment with 5% magnesium chloride (MgCl

2) before UVB radiation effect [

56]. However, zinc was found to be safer and effective in many topical applications. According to the report of the FDA of the United States, three zinc containing compounds, Zinc oxide, Zinc carbonate and Zinc acetate for safer and effective application as topical skin protectant [

57]. Some other research studies suggested the important wound healing role of zinc in tissue. Zinc oxide (ZnO) demonstrated a sunscreen protective role as well as effectiveness for treatment of skin rashes, pruritus, psoriasis, ringworms, impetigo, ulcers and eczema [

58]. Another most important element, iron (Fe) found most abundant in trace metals with various skin benefits. Most importantly, it shows its major action in skin relevant procollagen-proline dioxygenases [

59]. More interestingly, iron (Fe) becomes helpful against UV-induced damaging effects by expressing a higher amount of Iron in UV exposed skin (53.0 ppm) than unexposed skin (17.8 ppm) [

60]. Moreover, Copper (Cu) notes an effective role in stimulation of collagen formation and improvement of skin health. In beauty products, copper-peptides have been found to relax skin irritation, improve skin elasticity, skin firmness, heal photodamage skin, decrease fine lines and treat skin wrinkles with some more benefits [

61].

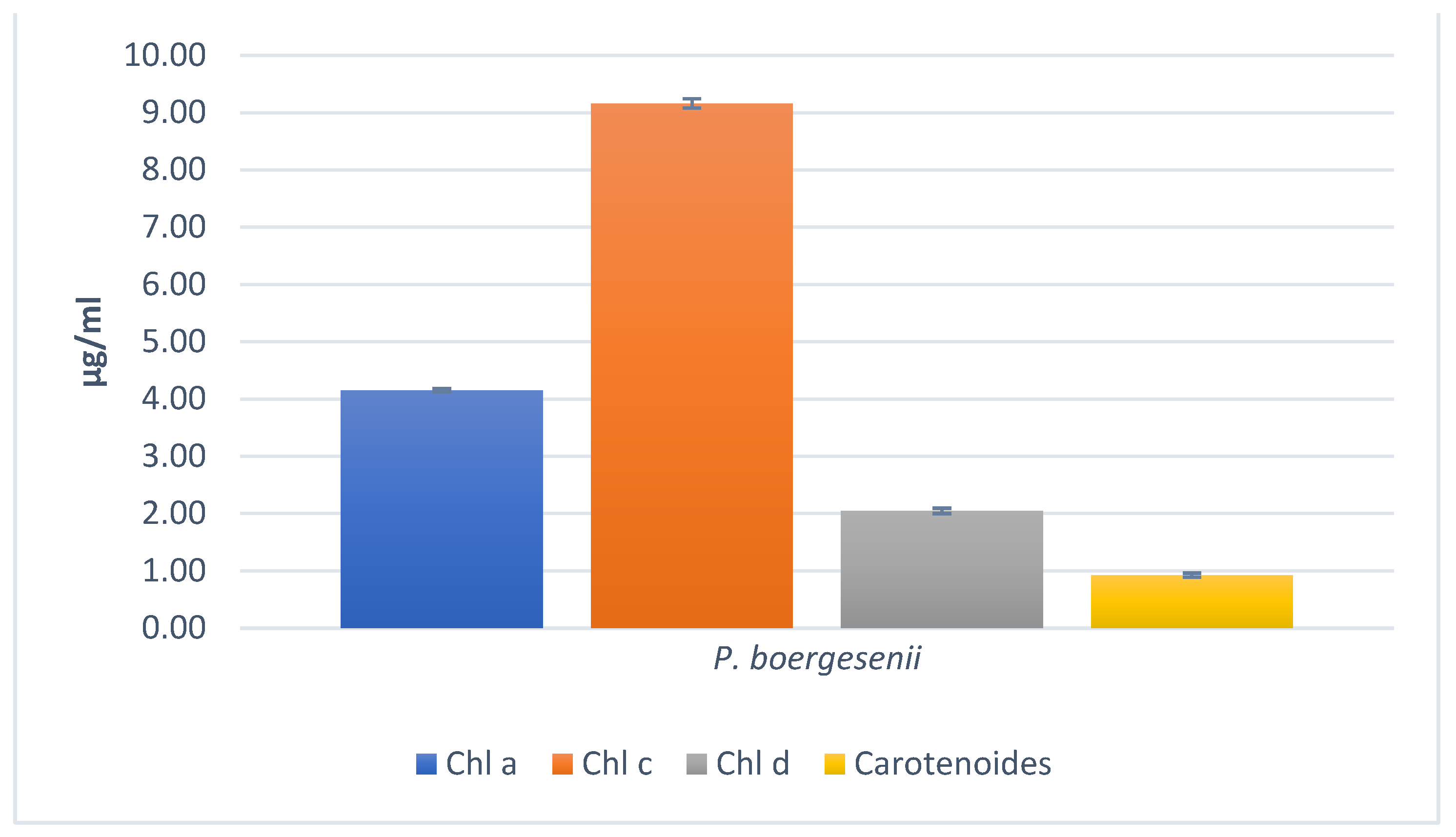

3.7. Determination of Pigments content

3.7.1. Quantification of Chlorophylls, Carotenoids, Fucoxanthin, Phycoerythrin, and Phycocyanin

Figure 8.

(a). Pigment analysis in 100% Methanol by Osório et al. 2020.

Figure 8.

(a). Pigment analysis in 100% Methanol by Osório et al. 2020.

Figure 8.

(b). Pigment analysis in 100% Ethanol by Osório et al. 2020.

Figure 8.

(b). Pigment analysis in 100% Ethanol by Osório et al. 2020.

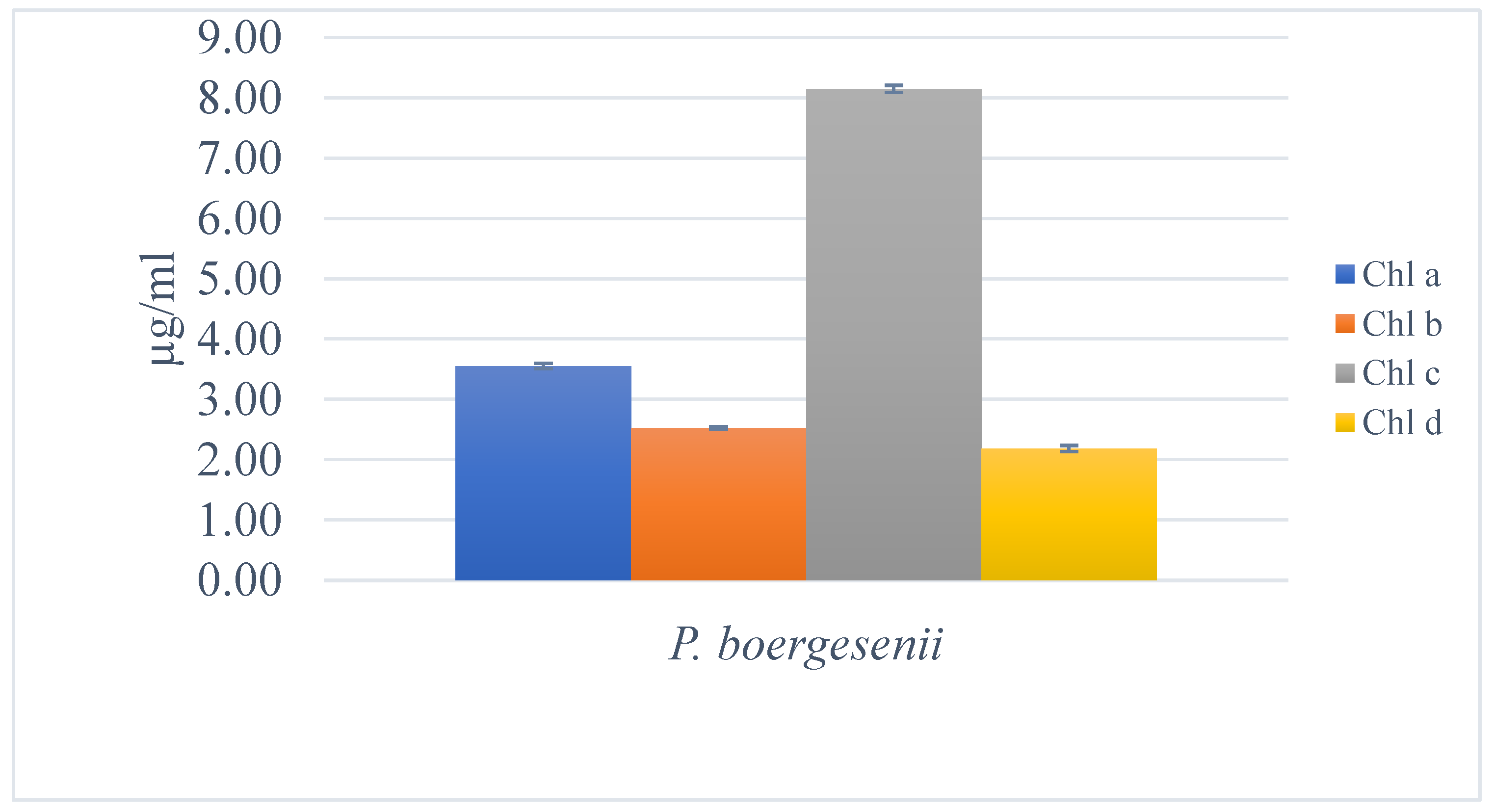

The pigment content of P. boergesenii was analyzed using various solvents to extract different classes of pigments. The extraction process was carried out following established protocols and in triplicate to ensure accuracy. In the 100% methanolic extract of P. boergesenii, the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll c, and carotenoids were found to be 4.15 µg/mL, 9.16 µg/mL, 2.05 µg/mL, and 0.93 µg/mL, respectively. On the other hand, in the 100% ethanolic extract, the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll c, and chlorophyll d were determined to be 3.55 µg/mL, 2.53 µg/mL, 8.15 µg/mL, and 2.18 µg/mL, respectively. The analysis of pigment content in P. boergesenii is of particular interest due to the potential cosmetic benefits associated with these pigments. Pigments derived from natural sources, such as algae, have gained attention in the cosmetic industry for their various functional properties and aesthetic appeal.

Several related studies have demonstrated the importance of algal pigments in cosmetic applications. For instance, chlorophylls, which are major photosynthetic pigments found in algae, have been recognized for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. These properties are beneficial in skincare products as they help protect the skin from oxidative stress and contribute to a healthier and more youthful appearance [

62]. Carotenoids, another class of pigments found in algae, have shown significant potential in cosmetic formulations. These pigments are known for their antioxidant properties and their ability to scavenge free radicals, which can contribute to premature aging and skin damage. Carotenoids, such as β-carotene and astaxanthin, have been extensively studied for their photoprotective effects against UV-induced skin damage, including the prevention of wrinkle formation and improvement of skin elasticity [

63,

64]. Fucoxanthin, a brown pigment specific to brown algae, has also attracted attention in the cosmetic industry. It has been reported to have anti-aging and skin lightening properties. Fucoxanthin exhibits antioxidant activity and inhibits the activity of tyrosinase, an enzyme involved in melanin synthesis, which makes it a potential ingredient in skin whitening and brightening products [

65]. Moreover, the red pigments phycoerythrin and phycocyanin, extracted from certain red algae species, have been investigated for their cosmetic applications. These pigments possess strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making them valuable for skincare products targeted at reducing skin redness, inflammation, and providing overall skin protection [

66]. By determining the pigment content in

P. boergesenii, this study contributes to our understanding of the potential cosmetic benefits associated with these algae. The presence of chlorophylls, carotenoids, fucoxanthin, phycoerythrin, and phycocyanin in the algal extract suggests that

P. boergesenii could be a promising natural source for cosmetic formulations aiming to harness the antioxidant, anti-aging, skin lightening, and anti-inflammatory properties of these pigments.

Using the same method with DMSO:Water (4:1, v/v) solvent mixture, no fucoxanthin was detected in the

P. boergesenii sample. Fucoxanthin is a specific brown pigment typically found in brown algal species and is known for its various beneficial properties, including antioxidant and skin lightening effects. However, the absence of fucoxanthin in the analyzed sample suggests that

P. boergesenii may not contain significant levels of this particular pigment. It is important to consider that the presence or absence of fucoxanthin can vary among different algal species and may be influenced by various factors such as growth conditions, geographical location, and extraction methods [

67]. Further investigation or alternative extraction techniques may be necessary to determine the presence of fucoxanthin in

P. boergesenii or to explore other potential sources of this pigment.

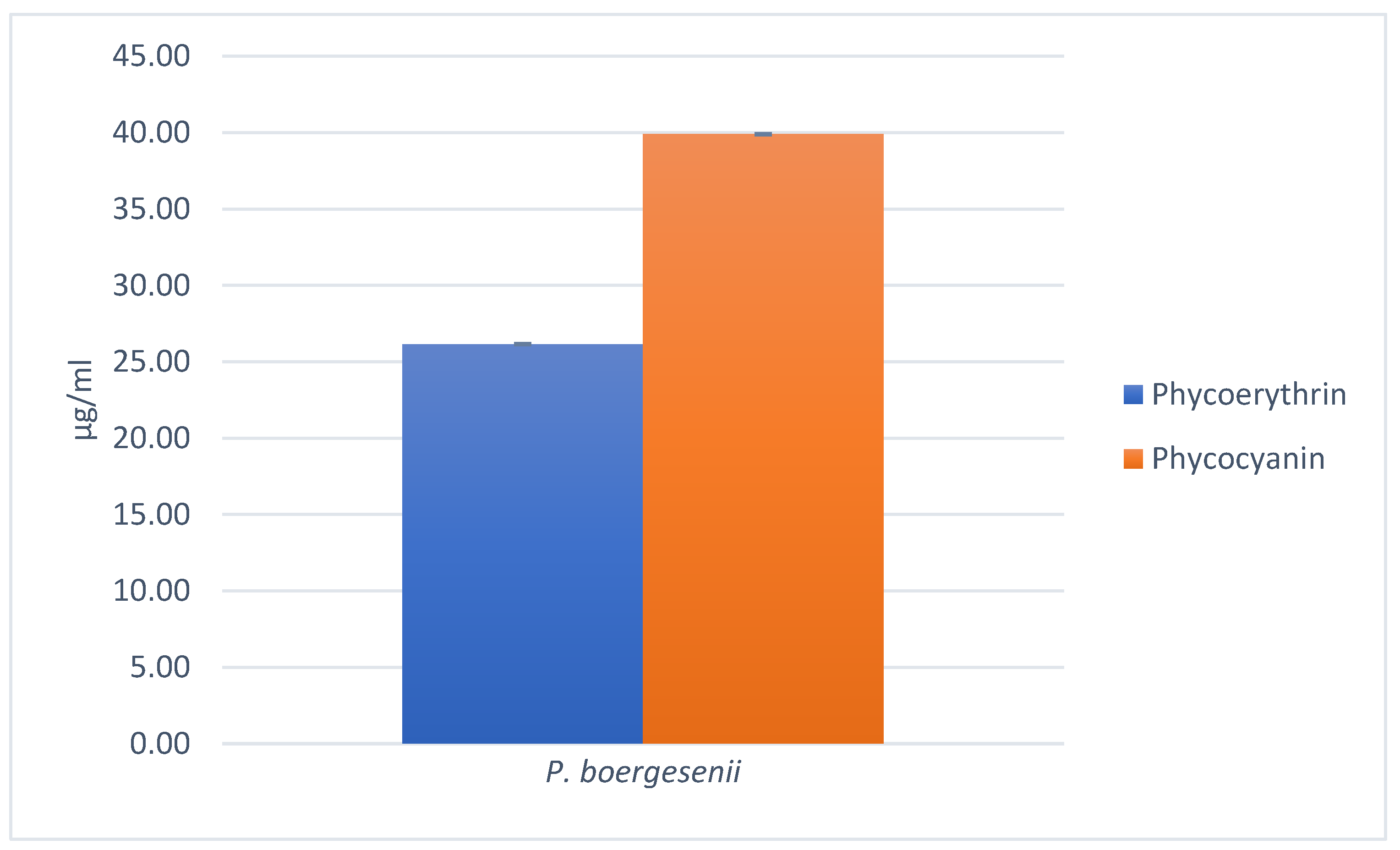

Figure 8.

(c). Pigment analysis in Phosphate Buffer (pH = 6.8) by Osório et al. 2020.

Figure 8.

(c). Pigment analysis in Phosphate Buffer (pH = 6.8) by Osório et al. 2020.

Using the Phosphate Buffer (pH = 6.8) as the solvent, the pigment analysis of

P. boergesenii revealed the presence of phycoerythrin at a concentration of 26.15 µg/mL and phycocyanin at a concentration of 39.90 µg/mL. Phycoerythrin and phycocyanin are known as accessory pigments commonly found in various species of red algae (Rhodophyta). These pigments play important roles in photosynthesis, light absorption, and energy transfer within the algal cells. Additionally, phycoerythrin and phycocyanin have shown potential applications in the cosmetic industry due to their antioxidant properties and ability to scavenge free radicals, which contribute to skin aging and damage. The presence of these pigments in

P. boergesenii suggests its potential as a natural source of phycoerythrin and phycocyanin for cosmetic formulations aimed at promoting skin health and protection against oxidative stress [

68,

69].

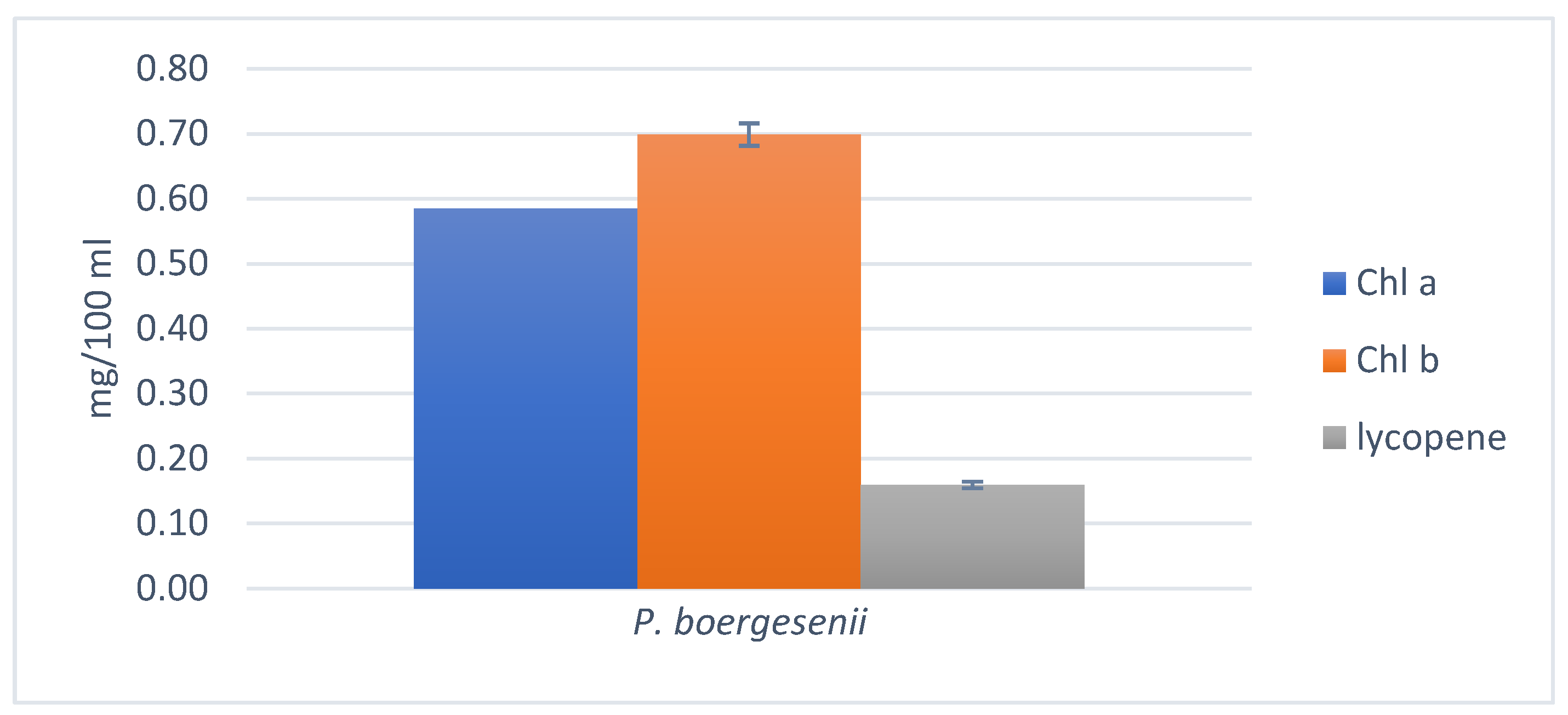

3.7.2. Estimation of Chlorophylls and Lycopene

Figure 9.

Pigment analysis in acetone–hexane mixture (2:3) by Nagata and Yamashita, (1992).

Figure 9.

Pigment analysis in acetone–hexane mixture (2:3) by Nagata and Yamashita, (1992).

By employing the acetone-hexane mixture (2:3) as the extraction solvent, the estimation of chlorophylls and lycopene in

P. boergesenii was performed following the method established by Nagata and Yamashita, [

28]. The analysis revealed the presence of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and lycopene in the algal sample. The concentration of chlorophyll a was determined to be 0.58 mg/100 mL, while chlorophyll b was quantified at 0.70 mg/100 mL. Additionally, the pigment lycopene was found at a concentration of 0.16 mg/100 mL. These pigments possess beneficial properties that make them valuable in cosmetic and skincare applications. Chlorophylls have been shown to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective effects, contributing to the maintenance of healthy skin. Lycopene, on the other hand, is recognized for its potent antioxidant properties and its potential role in protecting the skin from damage induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The presence of chlorophylls and lycopene in

P. boergesenii highlights its potential as a natural source of these pigments, which can be utilized in the development of cosmetic formulations aimed at enhancing skin health and providing protection against environmental stressors [

70,

71].

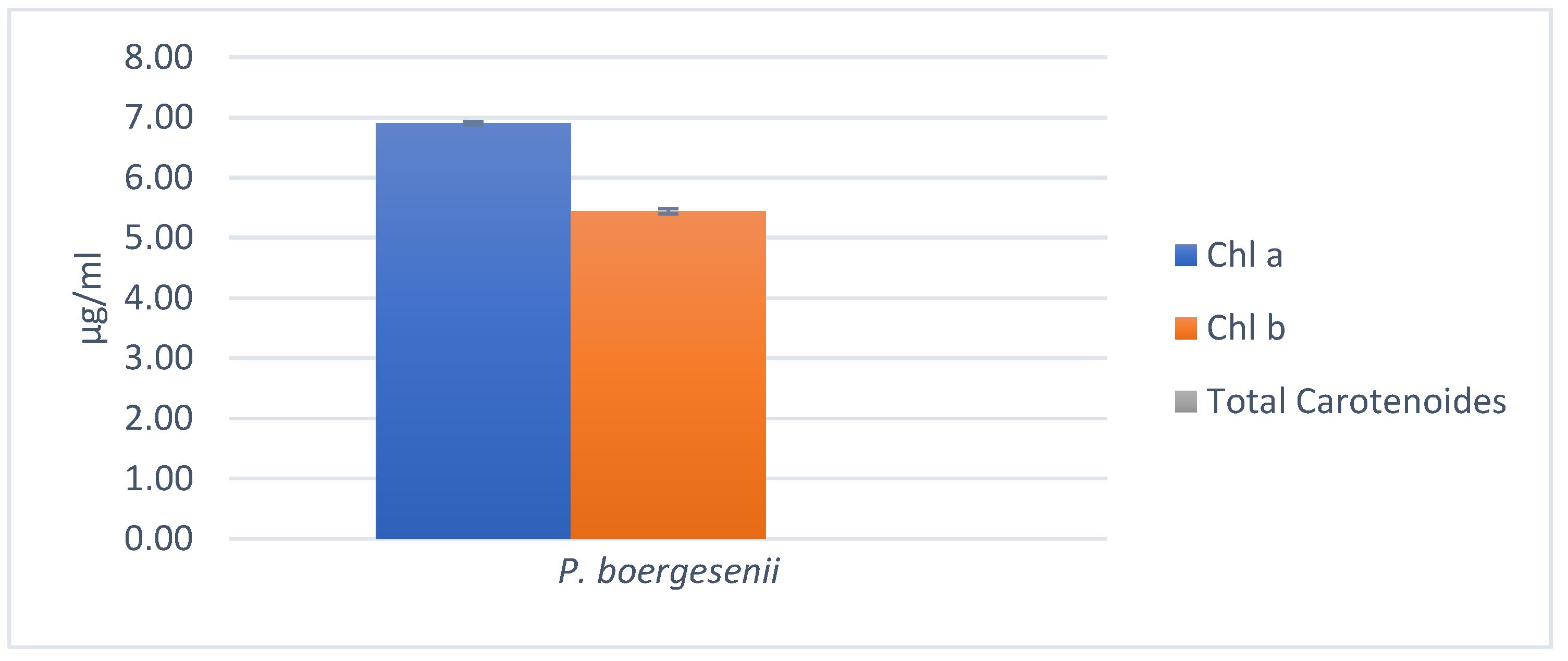

3.7.3. Chlorophylls and Total Carotenoids estimation

Figure 10.

Pigment analysis in acetone-water mixture (4:1) by Yang et al. (1998).

Figure 10.

Pigment analysis in acetone-water mixture (4:1) by Yang et al. (1998).

The estimation of chlorophylls and total carotenoids in

P. boergesenii using the acetone-water extraction method yielded interesting results. The concentrations of Chlorophyll a and Chlorophyll b were determined to be 6.90 µg/mL and 5.44 µg/mL, respectively. These values indicate the presence of significant amounts of chlorophyll pigments in the algal sample. Interestingly, the analysis did not detect any measurable content of total carotenoids in the algal sample. Carotenoids are a diverse group of pigments that contribute to the coloration of plants and algae. They also play vital roles as antioxidants, protecting cells from oxidative damage. While carotenoids are commonly found in algae, their absence in

P. boergesenii could be attributed to various factors such as genetic variation, growth conditions, or specific metabolic pathways within the algal species. It is worth noting that the obtained results should be interpreted in the context of the specific extraction method and the sensitivity of the measurement techniques employed. The extraction solvent and wavelength selection for absorbance measurement were based on the method described by Yang et al. [

29].

When comparing the results, a significant variation can be observed in the pigment content depending on the extraction method and the solvents used. In general, the chlorophyll content (Chlorophyll a, b, and c) shows variations across the different methods. The highest concentrations of chlorophylls are observed in the 100% methanolic extract, followed by the acetone-water mixture (4:1) and the 100% ethanolic extract. The acetone-hexane mixture (2:3) yields lower concentrations of chlorophylls compared to other methods. Carotenoids, on the other hand, are detected in varying amounts depending on the method used. Carotenoids are present in the highest concentration in the 100% methanolic extract, followed by the 100% ethanolic extract. No carotenoids were detected in the acetone-water mixture (4:1). In terms of specific pigments, the presence of fucoxanthin was not detected in the DMSO-water (4:1) extract. However, phycoerythrin and phycocyanin were detected in significant amounts in the phosphate buffer (pH = 6.8) extract. These variations in pigment content can be attributed to the solubility properties of pigments in different solvents, as well as the selectivity of each solvent in extracting specific pigments. Additionally, factors such as the algal species, growth conditions, and the sensitivity of the measurement techniques employed in each study can contribute to the observed differences. Comparing the results obtained from different methods provides valuable insights into the composition and distribution of pigments in P. boergesenii. However, it is important to consider the limitations and specificities of each method and interpret the results in the context of the experimental conditions.

By examining multiple studies and using various extraction methods, a more comprehensive understanding of the pigment composition in P. boergesenii can be achieved. This knowledge can have implications for various fields, including ecology, biochemistry, and even applications in industries such as cosmetics and food. The variations in pigment content highlight the importance of selecting appropriate extraction methods based on the specific pigments of interest. For example, if the focus is on chlorophyll content, the 100% methanol or acetone-water (4:1) extraction methods may be more suitable. On the other hand, for specific pigments like fucoxanthin or phycobiliproteins (phycoerythrin and phycocyanin), different solvent systems or buffer solutions may be necessary to extract and quantify these compounds effectively. Comparing the results from different studies and methods also emphasizes the need for standardization in pigment analysis. Consistency in extraction protocols, solvent selection, and measurement techniques can ensure more reliable and comparable results across different research studies. Furthermore, the variations in pigment content can have implications for the potential applications of P. boergesenii. Pigments, such as chlorophylls and carotenoids, have antioxidant properties and are known for their potential health benefits. They also contribute to the color and visual appeal of natural products, making them valuable in the cosmetic and food industries. Understanding the pigment composition and content can aid in the development of products that harness the potential benefits of these pigments.

3.8. Analysis of Total Polyphenol Content

The obtained result for the total phenol content of

P. boergesenii was determined to be 86.50 µg/mL. This indicates the presence of a considerable amount of polyphenolic compounds in the algal extract. Polyphenols are bioactive compounds found in various plant sources, including marine macroalgae, and have been associated with numerous health-promoting effects, including antioxidant and anti-aging properties. Polyphenols are known for their antioxidant properties, which can help protect the skin from oxidative stress and contribute to its overall health and appearance. The high polyphenol content of

P. boergesenii indicates its potential as a natural ingredient for cosmetic formulations aimed at providing antioxidant and anti-aging benefits. The polyphenolic compounds have been recognized for their antioxidant activity and potential health benefits. For instance, studies by Souza et al. [

72] and Kim et al. [

73] have investigated the polyphenol content of various seaweed species and reported significant levels of polyphenols, highlighting their potential as natural sources of bioactive compounds. The total polyphenol content of

P. boergesenii was determined using a spectrophotometric method, following a procedure based on the Folin-Ciocalteu assay. The concentration of polyphenols in the algal sample was measured based on a standard curve constructed using gallic acid as a reference standard. Polyphenols are known for their antioxidant properties and their potential benefits in cosmetic applications.

3.9. Estimation of Total Protein

The total protein content of the

P. boergesenii sample was determined using the Bradford method, which allows for the quantification of protein concentration. The analysis revealed a total protein content of 113.72 µg/mL in the

P. boergesenii sample. This measurement provides valuable information about the protein content in the algal extract, indicating the presence of bioactive compounds that contribute to its potential cosmetic applications. Although specific studies focusing on the protein content of

P. boergesenii were not carried out before but, various studies have explored the protein composition of different marine macroalgae species. For example, a study by Farabegoli et al. [

74] investigated the protein profiles of various marine macroalgae using gel electrophoresis and proteomic analysis. The researchers identified several protein bands with different molecular weights, indicating the presence of diverse proteins in the macroalgae species studied. These findings suggest that marine macroalgae, including

P. boergesenii, contain a complex mixture of proteins that may contribute to their potential bioactivity. Furthermore, a study by Dixit et al. [

75] examined the protein content and amino acid composition of different seaweed species. The researchers found substantial protein content in the analyzed seaweed samples and observed variations in amino acid composition among the species. These findings highlight the nutritional and functional potential of seaweed proteins. Although there may be variations in protein content and composition among different algae species, the presence of proteins in

P. boergesenii aligns with the general characteristics of marine macroalgae.

3.10. In vitro Antioxidant Analysis using the DPPH Method

Figure 11.

Percent Radical Scavenging Activity, (a): for ethanolic extract, (b): for methanolic extract.

Figure 11.

Percent Radical Scavenging Activity, (a): for ethanolic extract, (b): for methanolic extract.

The results of the DPPH assay demonstrated that both the ethanolic and methanolic extracts of P. boergesenii exhibited significant antioxidant activity. In the ethanolic extracts, the inhibition percentage ranged from 35.5% at 100 μg/mL to 76.75% at 500 μg/mL. Similarly, the methanolic extracts showed inhibition percentages ranging from 46.41% at 100 μg/mL to 73.85% at 500 μg/mL. The IC50 values, representing the concentration required to achieve 50% inhibition, were calculated as 36.75 μg/mL for the ethanolic extract and 42.784 μg/mL for the methanolic extract of P. boergesenii. Ascorbic acid, used as a reference standard, exhibited IC50 values of 9.87 μg/mL for the ethanolic extract and 11.98 μg/mL for the methanolic extract. These findings suggest that both the ethanolic and methanolic extracts of P. boergesenii possess significant antioxidant activity, although the extracts showed slightly higher IC50 values compared to ascorbic acid. Antioxidants play a crucial role in neutralizing free radicals and protecting the body from oxidative stress. The results indicate that P. boergesenii may have potential as a source of natural antioxidants for various applications in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries.

Several studies have investigated the antioxidant potential of marine macroalgae, highlighting their significance as a rich source of bioactive compounds with potential applications in various industries, including cosmetics. A study by Wang, Jonsdottir, and Ólafsdóttir [

76] explored the antioxidant activity of different marine macroalgae species and reported substantial scavenging activity against DPPH radicals. The authors attributed this activity to the presence of phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and flavonoids, which are known to possess strong antioxidant properties. These findings support the idea that the antioxidant activity observed in

P. boergesenii may be due to the presence of similar bioactive compounds. In a study by El-Shafei, Hegazy, and Acharya [

77], various marine macroalgae extracts were evaluated for their antioxidant potential using the DPPH assay. The results demonstrated significant DPPH scavenging activity, suggesting the presence of potent antioxidant compounds in these algae. The study further highlighted the importance of marine macroalgae as promising sources of natural antioxidants. Furthermore, a study by Monteiro et al. [

78] investigated the antioxidant activity of different extracts obtained from marine macroalgae, including methanol and ethanol extracts. The researchers employed the DPPH assay and observed considerable antioxidant potential in the tested extracts. The findings indicated that the antioxidant activity could be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds and other bioactive constituents. The results of these related studies support and complement our findings, highlighting the significant antioxidant activity exhibited by marine macroalgae, including

P. boergesenii. The presence of bioactive compounds such as phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and flavonoids in marine macroalgae likely contributes to their antioxidant potential. These findings further validate the potential of marine macroalgae extracts, including

P. boergesenii, as valuable sources of natural antioxidants for various applications, including cosmetic formulations.

3.13. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

Figure 12.

Tyrosinase inhibition (%) by dopachrome method.

Figure 12.

Tyrosinase inhibition (%) by dopachrome method.

Based on the results obtained from the assay, the P. boergesenii extract demonstrated a tyrosinase inhibition of 62.14%. In comparison, the reference standard Kojic acid exhibited a tyrosinase inhibition of 80.37%. The findings indicate that the P. boergesenii extract possesses significant tyrosinase inhibition activity, although it is slightly lower than that of Kojic acid. Tyrosinase is an enzyme involved in melanin production, and inhibiting its activity is desirable for addressing hyperpigmentation concerns in the cosmetic industry. The results suggest that the P. boergesenii extract could potentially be utilized as an ingredient in cosmetic formulations targeting hyperpigmentation. However, further investigations are warranted to explore the underlying mechanisms of tyrosinase inhibition and to assess the extract’s stability and safety for cosmetic applications.

Several studies have explored the potential of marine macroalgae as a source of tyrosinase inhibitors for various applications, including skincare and cosmetic formulations. A study by Im [

79] investigated the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of various marine macroalgae extracts. The researchers found significant tyrosinase inhibition in several algae species, indicating their potential as natural tyrosinase inhibitors. This aligns with our results, where the ethanolic and methanolic extracts of

P. boergesenii demonstrated notable tyrosinase inhibition activity. In another study, Jo et al. [

80] evaluated the tyrosinase inhibitory potential of different marine macroalgae extracts. The researchers observed considerable tyrosinase inhibition in certain algae extracts, attributing the activity to the presence of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other bioactive constituents. These findings support the notion that

P. boergesenii extracts may contain similar bioactive compounds responsible for tyrosinase inhibition. Furthermore, a study by Fitton et al. [

81] investigated the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of various marine macroalgae species. The researchers discovered significant tyrosinase inhibition in some algae extracts, emphasizing their potential as natural tyrosinase inhibitors. The study also highlighted the importance of exploring marine macroalgae as promising sources of bioactive compounds for cosmetic and skincare applications. The results of these related studies corroborate the present findings and underscore the potential of marine macroalgae, including

P. boergesenii, as a source of tyrosinase inhibitors. The presence of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other bioactive constituents in these algae extracts may contribute to their tyrosinase inhibitory activity. These findings suggest that

P. boergesenii extracts could be further explored for their potential use in cosmetic formulations targeting skin pigmentation disorders and related applications.

4. Conclusions

A comprehensive analysis of Phaeophyta P. boergesenii has revealed its substantial potential as a valuable source of bioactive compounds for cosmetic applications. The study conducted an in-depth examination of various aspects, including the characterization of P. boergesenii using techniques such as GCMS, FTIR, HRLCMS, and ICP-AES. Additionally, the study investigated the pigment content, total polyphenol content, total protein content, antioxidant activity, and tyrosinase inhibition potential. The findings highlight the exceptional biochemical profile and significant cosmetic potential of the marine alga P. boergesenii. The study has identified several promising active ingredients in P. boergesenii, including long-chain fatty acids, Ergosterol derivatives, and Stigmastane derivatives. These compounds offer various benefits for the skin, such as moisturization, enhancement of the skin barrier function, antibacterial and antifungal effects, anti-inflammatory properties, and immunostimulatory benefits. Additionally, carbohydrate derivatives and other phytochemical compounds in P. boergesenii have demonstrated remarkable skincare benefits, including antioxidant activity, anti-wrinkle effects, acne-fighting properties, moisturizing capabilities, antimicrobial action, and conditioning properties. Moreover, the study found that P. boergesenii contains amino acids and minerals that are potent and non-toxic ingredients essential for protecting the skin against UV damage, promoting antioxidant activity, inhibiting melanogenesis, supporting skin whitening, exhibiting anti-aging effects, and stimulating collagen synthesis. The high concentrations of Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid, Hydroxyproline, Glycine, Alanine, and Serine, along with essential elements like Silicon (Si), Potassium (K), Calcium (Ca), Iron (Fe), and Magnesium (Mg), further contribute to its skincare benefits.

The investigation of pigment content revealed variations based on the extraction method and solvents used, resulting in varying amounts of chlorophylls and carotenoids. Furthermore, the analysis of total polyphenol content and total protein content confirmed the presence of these bioactive compounds in P. boergesenii, known for their antioxidant properties. In vitro antioxidant analysis demonstrated significant antioxidant activity in the ethanolic and methanolic extracts of P. boergesenii, highlighting its potential as a natural antioxidant for cosmetic and pharmaceutical applications. The tyrosinase inhibition assay further indicated the extract’s ability to address hyperpigmentation concerns. The comprehensive findings suggest a diverse range of cosmetic applications for P. boergesenii and its derived compounds, including moisturizers, photoprotective formulations, conditioners, skin whitening products, anti-wrinkle creams, and soothing creams. The extract’s antimicrobial properties and contribution to overall skin health enhance its appeal. Additionally, the abundance of P. boergesenii in the Beyt Dwarka sea coast minimizes cultivation concerns, making it a viable option for incorporation into skincare formulations.

However, further investigations are necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of tyrosinase inhibition and to assess the extract’s stability and safety for cosmetic applications. In conclusion, the comprehensive analysis of Phaeophyceae P. boergesenii provides scientific evidence supporting its potential as a rich source of bioactive compounds with significant cosmetic benefits. The promising active ingredients, antioxidant activity, tyrosinase inhibition potential, and contributions to overall skin health make P. boergesenii an appealing option for skincare formulations. The utilization of marine algae-derived compounds holds great promise in the cosmetics industry due to their effectiveness, lower risks compared to synthetic compounds, and compatibility with the skin’s natural structure. Further research, in vitro evaluations, and clinical studies will unlock the full potential of P. boergesenii and its application in skincare formulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.K. and L.P.; methodology, H.S.K.; investigation, H.S.C. and N.B.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.K. and N.B.P; writing—review and editing, H.S.K. and L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

It is the authors’ sincere gratitude to IIT Bombay-SAIF (Indian Institute of Technology, Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility) for providing the HRLCMS-QTOF facilities used in this study. The authors also would like to thank MARE—Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre—ARNET, and the University of Coimbra, within the scope of the project LA/P/0069/2020 granted to the Associate Laboratory ARNET, and UIDB/04292/2020 granted to MARE—Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, S.K. Marine cosmeceuticals. Journal of cosmetic dermatology 2014, 13, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdudo, A.; Burger, P.; Merck, F.; Dingas, A.; Rolland, Y.; Michel, T.; Fernandez, X. Development of a natural ingredient—Natural preservative: A case study. Comptes Rendus Chimie 2016, 19, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R.; Calafat, A.M. Phthalates and human health. Occupational and environmental medicine 2005, 62, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlantézec, R.; Monfort, C.; Rouget, F.; Cordier, S. Maternal occupational exposure to solvents and congenital malformations: a prospective study in the general population. Occupational and environmental medicine 2009, 66, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalasariya, H.S.; Patel, N.B.; Yadav, A.; Perveen, K.; Yadav, V.K.; Munshi, F.M.; Yadav, K.K.; Alam, S.; Jung, Y.K.; Jeon, B.H. Characterization of fatty acids, polysaccharides, amino acids, and minerals in marine macroalga Chaetomorpha crassa and evaluation of their potentials in skin cosmetics. Molecules 2021, 26, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Desai, A.Y.; Mulye, V. Seaweed resources and utilization: an overview. Biotech Express 2015, 2, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.; Neto, J.M. (Eds.) Marine algae: biodiversity, taxonomy, environmental assessment, and biotechnology. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jesumani, V.; Du, H.; Aslam, M.; Pei, P.; Huang, N. Potential use of seaweed bioactive compounds in skincare—A review. Marine drugs 2019, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Bhuyan, P.P.; Patra, S.; Nayak, R.; Behera, P.K.; Behera, C.; Behera, A.K.; Ki, J.S.; Jena, M. Beneficial effects of seaweeds and seaweed-derived bioactive compounds: Current evidence and future prospective. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2022, 39, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, K.; Sivadasan, D.; Alghazwani, Y.; Asiri, Y.I.; Prabahar, K.; Al-Qahtani, A.; Mohamed, J.M.M.; Khan, N.A.; Krishnaraju, K.; Paulsamy, P.; Vasudevan, R. Potential of seaweed biomass: snake venom detoxifying action of brown seaweed Padina boergesenii against Naja naja venom. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.M.; Patel, I.C. A review on phytoconstituents of marine brown algae. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.M. Marine algae (seaweeds) associated with coral reefs in the Gulf. Coral Reefs of the Gulf: Adaptation to Climatic Extremes 2012, 309–335. [Google Scholar]

- Moubayed, N.M.; Al Houri, H.J.; Al Khulaifi, M.M.; Al Farraj, D.A. Antimicrobial, antioxidant properties and chemical composition of seaweeds collected from Saudi Arabia (Red Sea and Arabian Gulf). Saudi journal of biological sciences 2017, 24, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, T.Y.; Rajasree, S.R.; Kirubagaran, R. Evaluation of zinc oxide nanoparticles toxicity on marine algae Chlorella vulgaris through flow cytometric, cytotoxicity and oxidative stress analysis. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2015, 113, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitha, J.; Palani, S. Phytochemical screening, GC-MS analysis and antioxidant activity of marine algae Chlorococcum humicola. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016, 5, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Tatipamula, V.B.; Killari, K.N.; Prasad, K.; Rao, G.S.N.K.; Talluri, M.R.; Vantaku, S.; Bilakanti, D.; Srilakshmi, N. Cytotoxicity studies of the chemical constituents from marine algae Chara baltica. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019, 81, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapa, A.N.; Martin, Á.; Mato, R.B.; Cocero, M.J. Extraction of phytocompounds from the medicinal plant Clinacanthus nutans Lindau by microwave-assisted extraction and supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Industrial Crops and Products 2015, 74, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragunathan, V.; Pandurangan, J.; Ramakrishnan, T. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of methanol extracts from marine red seaweed Gracilaria corticata. Pharmacognosy Journal 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, B.; Eswaran, K. GC-MS determination of bioactive components of Gracilaria dura (C. agardh) J. Agardh. Science Research Reporter 2015, 5, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Salunke, M.; Wakure, B.; Wakte, P. HR-LCMS assisted phytochemical screening and an assessment of anticancer activity of Sargassum squarrossum and Dictyota dichotoma using in vitro and molecular docking approaches. Journal of Molecular Structure 2022, 1270, 133833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, M.A.; Wakure, B.S.; Wakte, P.S. High-resolution liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (HR-LCMS) assisted phytochemical profiling and an assessment of anticancer activities of Gracilaria foliifera and Turbinaria conoides using in vitro and molecular docking analysis. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosic, N.N.; Braun, C.; Kvaskoff, D. Extraction and analysis of mycosporine-like amino acids in marine algae. Natural products from marine algae: methods and protocols 2015, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Javith, M.A.; Balange, A.K.; Xavier, M.; Hassan, M.A.; Sanath Kumar, H.; Nayak, B.B.; Krishna, G. Comparative studies on the chemical composition of inland saline reared Litopenaeus vannamei. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology 2022, 20, 336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Carreto, J.I.; Carignan, M.O.; Montoya, N.G. A high-resolution reverse-phase liquid chromatography method for the analysis of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in marine organisms. Marine Biology 2005, 146, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falandysz, J.; Szymczyk, K.; Ichihashi, H.; Bielawski, L.; Gucia, M.; Frankowska, A.; Yamasaki, S.I. ICP/MS and ICP/AES elemental analysis (38 elements) of edible wild mushrooms growing in Poland. Food Additives & Contaminants 2001, 18, 503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Murugaiyan, K.; Narasimman, S. Elemental composition of Sargassum longifolium and Turbinaria conoides from Pamban Coast, Tamilnadu. International Journal of Research in Biological Sciences 2012, 2, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Osório, C.; Machado, S.; Peixoto, J.; Bessada, S.; Pimentel, F.B.; CAlves, R.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Pigments content (chlorophylls, fucoxanthin and phycobiliproteins) of different commercial dried algae. Separations 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]