Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

01 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and methods

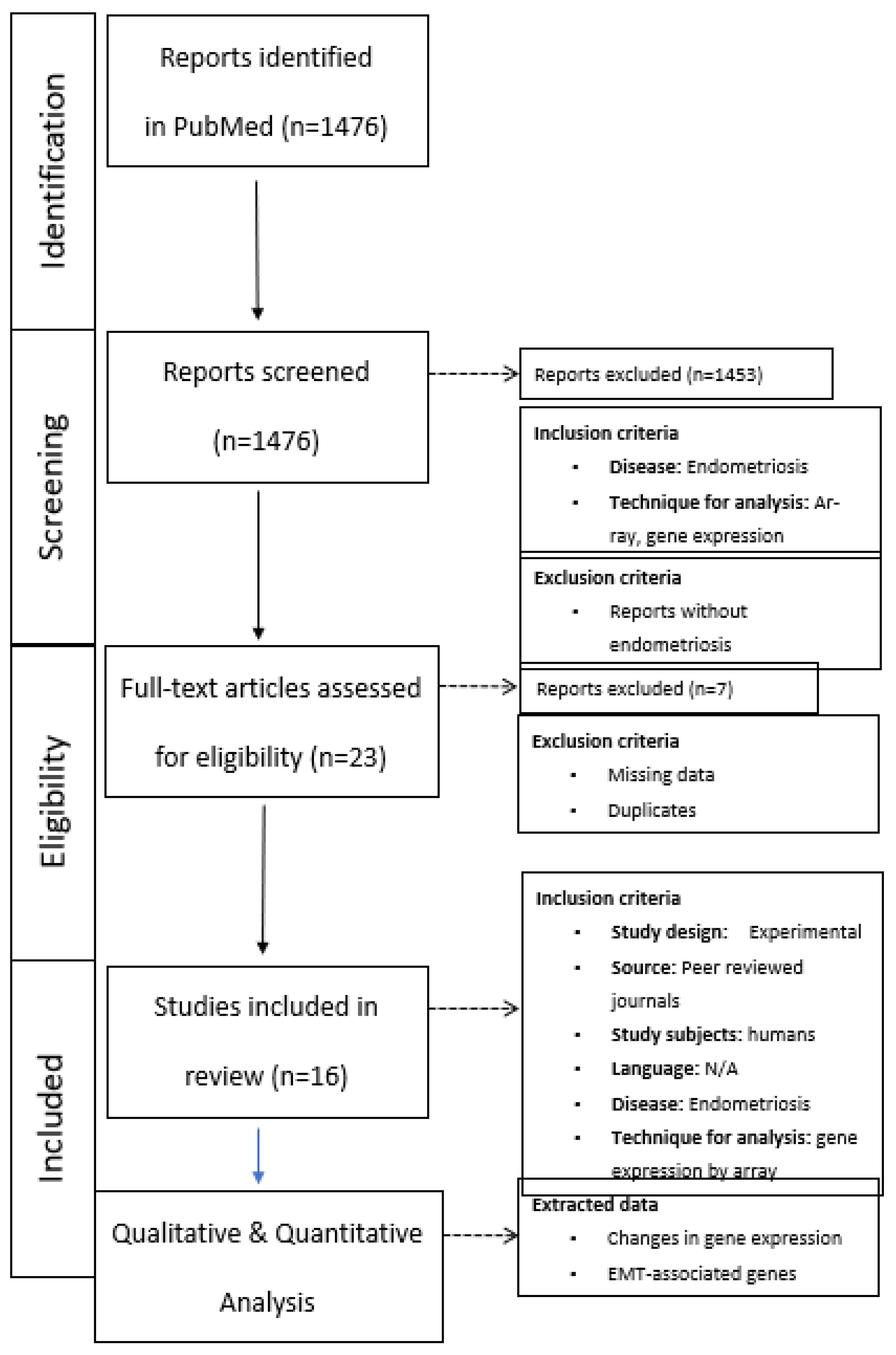

2.1. Search strategy and eligibility criteria

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Results

Discussion

Strength and limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clement, P.B. The pathology of endometriosis: a survey of the many faces of a common disease emphasizing diagnostic pitfalls and unusual and newly appreciated aspects. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2007, 14, 241–260.

- Boyle, D.P.; McCluggage, W.G. Peritoneal stromal endometriosis: a detailed morphological analysis of a large series of cases of a common and under-recognised form of endometriosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 62, 530–533. [CrossRef]

- Mecha, E.; Makunja, R.; Maoga, J.B.; Mwaura, A.N.; Riaz, M.A.; Omwandho, C.O.A.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Konrad, L. The Importance of Stromal Endometriosis in Thoracic Endometriosis. Cells 2021, 10, 180. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Adamson, G.D.; Diamond, M.P.; Goldstein, S.R.; Horne, A.W.; Missmer, S.A.; Snabes, M.C.; Surrey, E.; Taylor, R.N. An evidence-based approach to assessing surgical versus clinical diagnosis of symptomatic endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 142, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; A Flores, V. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, B.; Fischer, A.; Lotfy, H.; Turki, R.; Zahed, H.; Malik, R.; Holliday, C.; Glass, A.; Fishel, H.; Soliman, M.; et al. Recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn. 2014, 6, 219–227.

- Sandström, A.; Bixo, M.; Johansson, M.; Bäckström, T.; Turkmen, S. Effect of hysterectomy on pain in women with endometriosis: a population-based registry study. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 1628–1635. [CrossRef]

- Bougie, O.; McClintock, C.; Pudwell, J.; Brogly, S.B.; Velez, M.P. Long-term follow-up of endometriosis surgery in Ontario: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 270.e1–270.e19. [CrossRef]

- Long, A.J.; Kaur, P.; Lukey, A.; Allaire, C.; Kwon, J.S.; Talhouk, A.; Yong, P.J.; Hanley, G.E. Reoperation and pain-related outcomes after hysterectomy for endometriosis by oophorectomy status. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 57.e1–57.e18. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.A. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1927, 14, 422–469. [CrossRef]

- Yovich, J.L.; Rowlands, P.K.; Lingham, S.; Sillender, M.; Srinivasan, S. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: Look no further than John Sampson. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M.; Kulkarni, M.T.; Missmer, S.A. Is endometriosis more common and more severe than it was 30 years ago? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 452-461.

- Young, V.J.; Brown, J.K.; Saunders, P.T.; Horne, A.W. The role of the peritoneum in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2013, 19, 558–569. [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Wattiez, A.; Gomel, V.; Martin, D.C. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 327–340. [CrossRef]

- Samimi, M.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Mehdizadehkashi, A.; Eftekar, T.; Asemi, Z. The role of inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and apoptosis in the pathophysiology of endometriosis: Basis science and new insights based on gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 19384-19392.

- Liu, H.; Lang, J.H. Is abnormal eutopic endometrium the cause of endometriosis? The role of the eutopic endometrium in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, RA92-99.

- Benagiano, G.; Brosens, I.; Habiba, M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2014, 20, 386–402. [CrossRef]

- Jolly, M.K.; Ware, K.E. Gilja, S.; Somarelli, J.A.; Levine, H. EMT and MET: necessary or permissive for metastasis? Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 755-769.

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1420–1428. [CrossRef]

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 69–84. [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.; Shu, X.; Gassama-Diagne, A.; Thiery, J.P. Mesenchymal–epithelial transition in development and reprogramming. Nature 2019, 21, 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Diepenbruck, M.; Christofori, G. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis: yes, no, maybe? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2016, 43, 7-13.

- Savagner, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: from cell plasticity to concept elasticity. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2015, 112, 273-300.

- Debnath, P.; Huirem, R.S.; Dutta, P.; Palchaudhuri, S. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and its transcription factors. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20211754. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Darcha, C. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like and mesenchymal to epithelial transition-like processes might be involved in the pathogenesis of pelvic endometriosis†. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 712–721. [CrossRef]

- Nisolle, M.; Casanas-Roux, F.; Donnez, J. Coexpression of cytokeratin and vimentin in eutopic endometrium and endometriosis throughout the menstrual cycle: evaluation by a computerized method. Fertil. Steril. 1995, 64, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Song, I.O.; Hong, S.R.; Huh, Y.; Yoo, K.J.; Koong, M.K.; Jun, J.Y.; Kang, I.S. Expression of Vimentin and Cytokeratin in Eutopic and Ectopic Endometrium of Women with Adenomyosis and Ovarian Endometrioma. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1998, 40, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Konrad, L.; Gronbach, J.; Horné; F.; Mecha, E.O.; Berkes, E.; Frank, M.; Gattenlöhner, S.; Omwandho, C.O.; Oehmke, F.; Tinneberg, H.R. Similar characteristics of endometrial and endometriotic epithelial cells. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 49-59.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583.

- Kao, L.C.; Germeyer, A.; Tulac, S.; Lobo, S.; Yang, J.P.; Taylor, R.N.; Osteen, K.; Lessey, B.A.; Giudice, L.C. Expression Profiling of Endometrium from Women with Endometriosis Reveals Candidate Genes for Disease-Based Implantation Failure and Infertility. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2870–2881. [CrossRef]

- Absenger, Y.; Hess-Stumpp, H.; Kreft, B.; Krätzschmar, J.; Haendler, B.; Schütze, N.; Regidor, P.; Winterhager, E. Cyr61, a deregulated gene in endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 10, 399–407. [CrossRef]

- Burney, R.O.; Talbi, S.; Hamilton, A.E.; Vo, K.C.; Nyegaard, M.; Nezhat, C.R.; Lessey, B.A.; Giudice, L.C. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 3814–3826. [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, J.; Sharkey, A.; Mihalyi, A.; Simsa, P.; Catalano, R.; D’Hooghe, T. Global gene analysis of late secretory phase, eutopic endometrium does not provide the basis for a minimally invasive test of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1063–1068. [CrossRef]

- Fassbender, A.; Verbeeck, N.; Börnigen, D.; Kyama, C.; Bokor, A.; Vodolazkaia, A.; Peeraer, K.; Tomassetti, C.; Meuleman, C.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Combined mRNA microarray and proteomic analysis of eutopic endometrium of women with and without endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 2020–2029. [CrossRef]

- Eyster, K.M.; Boles, A.L.; Brannian, J.D.; Hansen, K.A. DNA microarray analysis of gene expression markers of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 77, 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Arimoto, T.; Katagiri, T.; Oda, K.; Tsunoda, T.; Yasugi, T.; Osuga, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Nishii, O.; Yano, T.; Taketani, Y.; et al. Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis of gene-expression profiles involved in ovarian endometriosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2003, 22, 551–560.

- Matsuzaki, S.; Canis, M.; Vaurs-Barrière, C.; Boespflug-Tanguy, O.; Dastugue, B.; Mage, G. DNA microarray analysis of gene expression in eutopic from patients with deep endometriosis using laser capture microdissection. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 84Suppl. 2, 1180–1190. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A.; Strawn, E.; Basir, Z.; Halverson, G.; Jailwala, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ghosh, S.; Guo, S.-W. Transcriptional Characterizations of Differences between Eutopic and Ectopic Endometrium. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 232–246. [CrossRef]

- Mettler, L.; Salmassi, A.; Schollmeyer, T.; Schmutzler, A.G.; Püngel, F.; Jonat, W. Comparison of c-DNA microarray analysis of gene expression between eutopic endometrium and ectopic endometrium (endometriosis). J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2007, 24, 249–258. [CrossRef]

- Eyster, K.M.; Klinkova, O.; Kennedy, V.; Hansen, K.A. Whole genome deoxyribonucleic acid microarry analysis of gene expression in ectopic versus eutopic endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 88, 1505-1533.

- Zafrakas, M.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Streichert, T.; Pournaropoulos, F.; Wölfle, U.; Smeets, S.J.; Wittek, B.; Grimbizis, G.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Pantel, K.; et al. Genome-wide microarray gene expression, array-CGH analysis, and telomerase activity in advanced ovarian endometriosis: a high degree of differentiation rather than malignant potential.. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 21, 335–344. [CrossRef]

- Borghese, B.; Mondon, F.; Noël, J.-C.; Fayt, I.; Mignot, T.-M.; Vaiman, D.; Chapron, C. Gene Expression Profile for Ectopic Versus Eutopic Endometrium Provides New Insights into Endometriosis Oncogenic Potential. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 2557–2562. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sengupta, J.; Mittal, S.; Ghosh, D. Genome-wide expressions in autologous eutopic and ectopic endometrium of fertile women with endometriosis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 84. [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, D.; Bray, J.D.; Su, E.; Pavone, M.E.; Dyson, M.T.; Navarro, A.; Kakinuma, T.; Bulun, S.E. Activated glucocorticoid and eicosanoid pathways in endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Sohler, F.; Sommer, A.; Wachter, D.L.; Agaimy, A.; Fischer, O.M.; Renner, S.P.; Burghaus, S.; Fasching, P.A.; Beckmann, M.W.; Fuhrmann, U.; et al. Tissue Remodeling and Nonendometrium-Like Menstrual Cycling Are Hallmarks of Peritoneal Endometriosis Lesions. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 20, 85–102. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.; García-Moreno, E.; Aghajanova, L.; Salumets, A.; A Horcajadas, J.; Esteban, F.J.; Altmäe, S. The mid-secretory endometrial transcriptomic landscape in endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac016. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kang, S. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in endometriosis using Illumina Human Methylation 450 K BeadChips. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2019, 86, 491–501. [CrossRef]

- Braza-Boïls, A.; Marí-Alexandre, J.; Gilabert, J.; Sánchez-Izquierdo, D.; España, F.; Estellés, A.; Gilabert-Estellés, J. MicroRNA expression profile in endometriosis: its relation to angiogenesis and fibrinolytic factors. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 978–988. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Hill, C.; Ewing, R.M.; He, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Bioinformatic analysis reveals the importance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the development of endometriosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8442. [CrossRef]

- Suda, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Ishiguro, T.; Adachi, S.; Kase, H.; Motoyama, T.; Inoue, I.; Enomoto, T. Different mutation profiles between epithelium and stroma in endometriosis and normal endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1899–1905. [CrossRef]

- Konrad, L.; Dietze, R.; Riaz, M.A.; Scheiner-Bobis, G.; Behnke, J.; Horné, F.; Hoerscher, A.; Reising, C.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I. Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition in endometriosis – When does it happen? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, E1915.

- Gescher, D.M.; Siggelkow, W.; Meyhoefer-Malik, A.; Malik, E. A priori implantation potential does not differ in eutopic endometrium of patients with and without endometriosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005, 272, 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Nap, A.W.; Groothuis, P.G.; Demir, A.Y.; Maas, J.W.; Dunselman, G.A.; de Goeij, A.F.; Evers, J.L. Tissue integrity is essential for ectopic implantation of human endometrium in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 30–34. [CrossRef]

- Gaetje, R.; Holtrich, U.; Engels, K.; Kissler, S.; Rody, A.; Karn, T.; Kaufmann, M. Differential expression of claudins in human endometrium and endometriosis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2008, 24, 442–449. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.-Y.; Li, X.; Weng, Z.-P.; Wang, B. Altered expression of claudin-3 and claudin-4 in ectopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 1692–1699. [CrossRef]

- Hoerscher, A.; Horné, F.; Dietze, R.; Berkes, E.; Oehmke, F.; Tinneberg, H.-R.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Konrad, L. Localization of claudin-2 and claudin-3 in eutopic and ectopic endometrium is highly similar. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1003–1011. [CrossRef]

- Loeffelmann, A.C.; Hoerscher, A.; Riaz, M.A.; Zeppernick, F.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Konrad, L. Claudin-10 Expression Is Increased in Endometriosis and Adenomyosis and Mislocalized in Ectopic Endometriosis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2848. [CrossRef]

- Horné, F.; Dietze, R.; Berkes, E.; Oehmke, F.; Tinneberg, H.-R.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Konrad, L. Impaired Localization of Claudin-11 in Endometriotic Epithelial Cells Compared to Endometrial Cells. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 1181–1192. [CrossRef]

- Chevronnay, H.P.G.; Cornet, P.B.; Delvaux, D.; Lemoine, P.; Courtoy, P.J.; Henriet, P.; Marbaix, E. Opposite Regulation of Transforming Growth Factors-β2 and -β3 Expression in the Human Endometrium. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1015–1025. [CrossRef]

- Young, V.J.; Brown, J.K.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Duncan, W.C.; Horne, A.W. The Peritoneum Is Both a Source and Target of TGF-β in Women with Endometriosis. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e106773. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, J.; Smycz-Kubańska, M.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A.; Bednarek, I.; Kondera-Anasz, Z. The involvement of multifunctional TGF-β and related cytokines in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Immunol. Lett. 2018, 201, 31–37. [CrossRef]

| Endometrium healthy | Endometrium with endometriosis |

Endometriotic lesions, all | OMA | PE | DIE | References |

| N=7 | N=8, 206/12.686 (1.6%) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 30 |

| N=41 | N=43, 95/12.651 (0.8%) | N=19 lesions, not spec. | Not spec. | Not spec. | Not spec. | 31 |

| N=16 | N=21, 885/54.600 (1.62%) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 32 |

| N=6 | N=10, 9/22.000 (0.04%) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 33 |

| N=18 | N=31 0/28.000 (0%) |

n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 34 |

| Sum | 1.195/129.937 (0.92%) |

| Genes | Up-regulation | Down-regulation | References |

| Claudin-3 | - | 0.59 | 32 |

| Claudin-6 | 1.54 | - | 32 |

| Claudin-10 | 2.3 | - | 30 |

| Claudin-14 | - | 0.65 | 32 |

| TGF-β3 | 100 3.14 |

- - |

30 32 |

| Endometrium healthy | Endometrium with endometriosis |

Endometriotic lesions, all | OMA | PE | DIE | References |

| n.d. | N=3 | N=3 (paired) 8/4,133 (0.2%) |

N=3 | n.d. | n.d. | 35 |

| n.d. | N=23 | N=23 (paired) 1,413/23,040 (6.1%) |

N=23 | n.d. | n.d. | 36 |

| n.d. | N=12 | N=12 (paired) 0/1,176 (0%) |

n.d. | n.d | N=12 | 37 |

| n.d. | N=12 | N=25 (paired) 904/9,600 (4684*) (9.4%/19.3%*) |

N=6 | N=5 | N=1 | 38 |

| N=5 (not used for the array) | N=5 | N=5 (paired) 13/1,176 (940*) (1.1%/1.38*) |

N=5 | n.d. | n.d. | 39 |

| n.d. | N=10 | N=10 (paired) 1,146/53,000 (2.16%) |

yes | yes | Not. spec | 40 |

| n.d. | N=4 | N=4 (paired) 36/44,928 (0.08%) |

N=4 | n.d. | n.d. | 41 |

| n.d. | N=6 | N=6 (paired) 5,600/53,000 (10.6%) |

N=6 | n.d. | n.d. | 42 |

| n.d. | N=18 | N=18 (paired) 847/29,421 (2.88%) |

N=18 | n.d. | n.d. | 43 |

| n.d. | N=6 | N=6 (paired) 1,366/47,000 (2.9%) |

N=6 | n.d. | n.d. | 44 |

| n.d. | N=17 | N=18 (paired) 3,901/54,675 (7.1%) |

n.d. | N=18 | n.d. | 45 |

| Sum | 15,234/321,149 (314,821*) (4.74%/4.84%*) |

| Genes | Up-regulation | Down-regulation | References |

| Claudin-1 | 6.64 0.87-2.85 |

- - |

45 43 |

| Claudin-2 | - | 0.45-0.55 | 43 |

| Claudin-3 | - - - |

0.14 0.06 0.58 |

45 43 35 |

| Claudin-4 | - - |

0.11 0.1 |

45 43 |

| Claudin-5 | 4,31 7.46 |

- - |

45 43 |

| Claudin-6 | 1.05 | - | 43 |

| Claudin-7 | - - |

0.19 0.12 |

45 43 |

| Claudin-8 | - | 0.28 | 43 |

| Claudin-9 | 2.16 | - | 43 |

| Claudin-10 | - | 0.17 | 43 |

| Claudin-11 | 54.05 69.3 100 |

- - - |

45 43 40 |

| Claudin-15 | 1.31-2.07 | - | 43 |

| Claudin-17 | 1.25 | - | 43 |

| Claudin-22 | - | 0.17 | 43 |

| TGF-β3 | 4.86 0.9-1.7 |

- - |

43 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).