1. Introduction

In recent years, the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in a significant worldwide public health crisis, profoundly impacting human physical and mental well-being, the global economy, and sociopolitical landscapes. To date, there have been over 754 million confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 globally, with 6.82 million reported deaths as of February 2023 [

1]. Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in November 2019, multiple variants of concern have arisen and rapidly disseminated across the globe [

2]. The initial predominant Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, BA.1, contains 35 mutations in its Spike protein compared to the original variant that emerged in late 2019 [

3]. Shortly after its identification, the BA.1 variant quickly emerged as the prevailing variant on a global scale and has subsequently undergone further genetic changes, giving rise to multiple sublineages.. On November 26, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated B.1.1.529 as a variant of concern based on recommendations from the WHO Technical Advisory Group on Virus Evolution [

4].

An essential aspect of anyj infectious disease is to determine whether infection results in long-lasting immunity or if recurrent reinfection is prevalent. Both natural immunity acquired from prior infection and vaccine-induced immunity against COVID-19 play a crucial role in reducing the severity and impact of the disease. However, several knowledge gaps remain concerning the risk of reinfection following previous exposure to different variants of SARS-CoV-2 [

5,

6,

7]. During the initial waves of SARS-CoV-2, including the wild-type, Alpha, and Delta variants, the prevailing belief was that infection conferred long-lasting immunity. However, more recent evidence, especially during the Omicron waves in 2022, has indicated that reinfection can occur relatively frequently [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, certain countries, including China, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, implemented strategies to effectively suppress community transmission and successfully maintained containment measures [

13,

14]. Prior to December 2022, China implemented a “zero COVID” policy, which aimed to achieve and maintain zero tolerance for local transmission of SARS-CoV-2. This policy focused on sustained containment by effectively preventing and responding to any externally introduced outbreaks. In the event of an outbreak, response measures were based on an assessment of the epidemic risk and utilized the same strategies employed during the initial containment phase [

15]. These measures are further reinforced by stringent border protection measures to minimize the occurrence of imported outbreaks. Additionally, routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is extensively conducted to enable highly sensitive surveillance for detecting infections [

16,

17,

18].

Shanghai is the largest city in eastern China. It experienced the first wave of COVID-19 caused by the Omicron BA.2 variant [

19] between March and May 2022 and the second wave caused by the circulating Omicron BA5.2 and BF.7 variants since December 2022, right after the downgrade of the “zero COVID” policy. A key question with the emergence of the new variants is the extent to which they are able to reinfect those who have had a prior natural infection. The reinfection rate could not be ascertained without routine PCR testing for the community.

This study aimed to assess the reinfection risk among people with COVID-19 confirmed during the 2022 spring outbreak within one year and explore the effect of hybrid immunity (i.e., vaccination vs. nonvaccination) on reinfection. The findings of this study are intended to provide scientific evidence for the implementation of appropriate intervention strategies and programs to target the oncoming waves of COVID-19 in Shanghai in the future and other areas with the possibility of considering a subsidy policy for COVID-19 vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in the study to assess the prevalence of reinfection among previously infected individuals during the second wave of the outbreak in December 2022.

Since the strict quarantine and frequent screening policy was implemented before December 1, 2022, in China for COVID-19 management, we assumed that all potential cases would be identified during the first wave in spring 2022. From March 1 to May 31, 2022, there were 245,803 new nucleic acid-positive cases in Pudong New Area according to the local nucleic acid testing information system. With the downgrade of the disease control policy after December 1, 2022, a great portion of the cases would not be identified since frequent PCR testing stopped. Nonetheless, we still found that 5,649 of 245,803 previously infected individuals tested positive again according to the same system in December 2022. We estimated that the lowest reinfection rate was 2.30% (5,649/245,803).

We conducted a stratified sampling method in this study. The estimated response rate was 60% according to the pilot study. The sample size of 3361 participants was determined for this cross-sectional study based on various factors. These factors include an estimated reinfection rate of 2.30%, an alpha risk of 5%, a maximum permissible error of 0.01, and a design effect of 2. The minimum sample size was calculated using the following formula commonly used in cross-sectional studies: N = 2(Z/δ)2p(1−p).

Telephone interviews were conducted from January 17 to 31, 2023 in Pudong New Area, Shanghai, eastern China. Participants included only permanent residents who had lived in Pudong New Area for ≥12 months. Guardians of children aged 6 months to 14 years were interviewed. Data collection was conducted by professional investigators at the Shanghai Pudong New Area Center for Disease Control and Prevention(PDCDC). Each selected respondent participated in the study and provided their responses to a questionnaire. The interviewers explained the questionnaire items to the respondents, and CDC professionals recorded the answers in a standardized questionnaire.

For the purpose of this study, reinfection was defined as a positive result on a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or rapid antigen test conducted between December 1 and 31, 2022.

2.2. Data sources and description

The questionnaire used in the telephone survey included three sets of questions regarding the following: (i) sociodemographic variables, including age and sex; (ii) occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, defined as a positive PCR or rapid antigen test; and (iii) COVID-19 vaccination status before the survey. Investigators asked participants about nucleic acid/antigen test results and the time of testing. If the participants had not experienced reinfection, other questions regarding reinfection were not asked. For those who declined to answer any part of the questionnaire, the remaining sections of the questionnaire were not administered. According to the type and dose of vaccine, we divided the respondents’ vaccination status into incomplete vaccination series (unvaccinated, or had one inactivated vaccines 14 days or longer before December 1, 2022), complete vaccination series (having received two doses of an inactivated vaccines 14 days or longer before December 1, 2022) and booster vaccination series (having received three or more doses of an inactivated vaccines 14 days or longer before December 1, 2022).

The questionnaire was validated in a pilot survey conducted in a small area before the formal survey.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The proportions of individuals who had SARS-CoV-2 reinfections were calculated by dividing the number of reinfections by the total number of respondents. These proportions were then stratified by sex and age group. To compare the reinfection risk across different subgroups, Pearson’s chi-square test was employed.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify potential factors that influenced the risk of reinfection. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to examine the associations between these factors and the likelihood of reinfection.

A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Basic characteristics of respondents

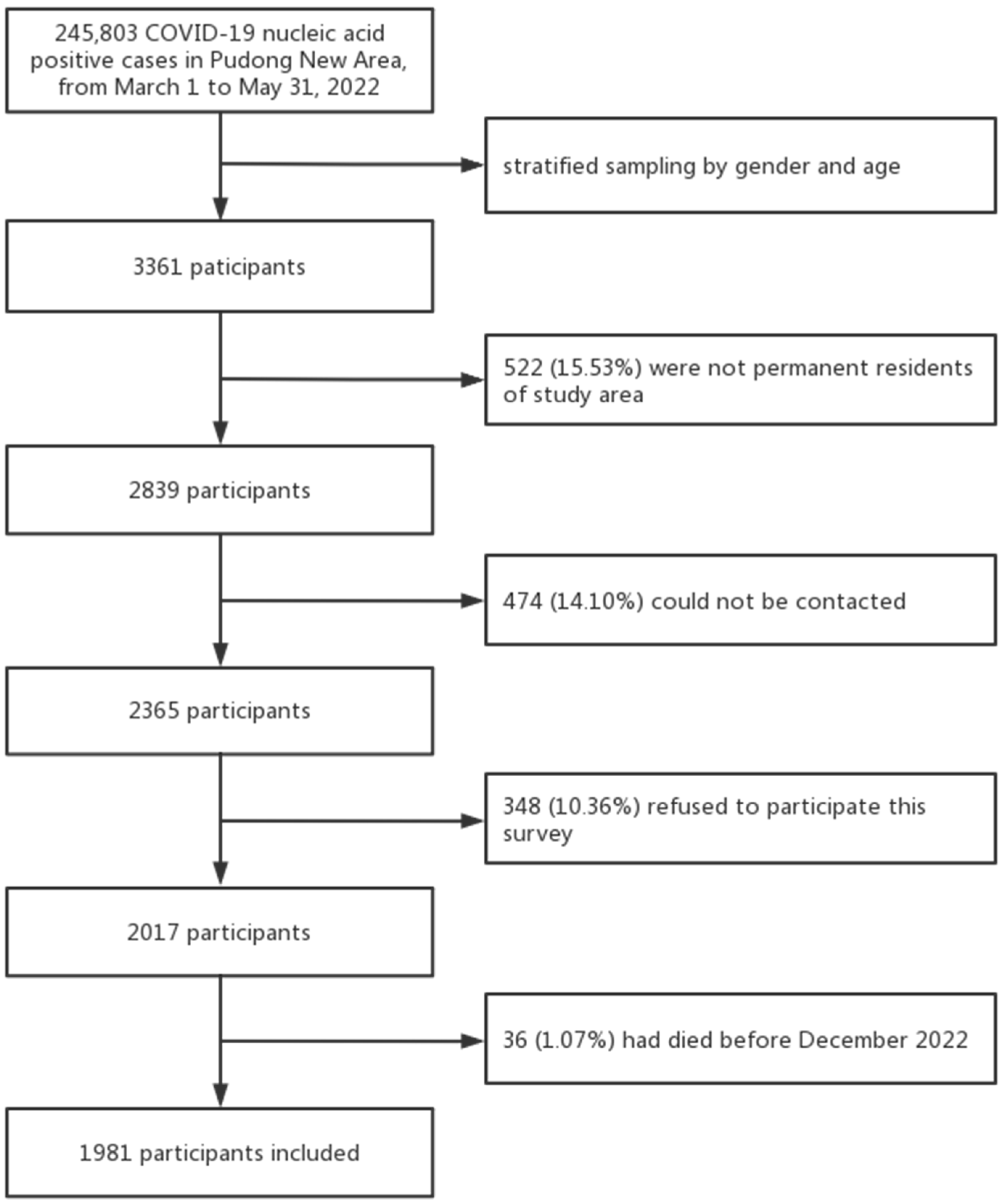

Among the 3361 respondents, 522 (15.53%) were excluded since they were not permanent residents of the study area, 474 (14.10%) could not be contacted, 36 (1.07%) had died before December 1, and 348 (10.36%) refused to participate(

Figure 1); a total of 1981 valid questionnaires were finally collected, yielding a response rate of 58.94% (1981/3361) (

Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant selection.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants..

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants..

| Sex |

Age group |

COVID-19 infections from March to May 2022

N = 245803 |

No. of people with COVID-19 sampled

N = 3361 |

No. of people with COVID-19 who responded

N = 1981 |

Response rate (%) |

| Male |

0–9 |

4453 (1.81%) |

53 (1.58%) |

40 (2.02%) |

65.57 |

| |

10–19 |

5653 (2.3%) |

76 (2.26%) |

38 (1.92%) |

49.35 |

| |

20–29 |

22151 (9.01%) |

333 (9.91%) |

153 (7.72%) |

50.50 |

| |

30–39 |

30411 (12.37%) |

405 (12.05%) |

238 (12.01%) |

57.21 |

| |

40–49 |

24528 (9.98%) |

365 (10.86%) |

199 (10.05%) |

59.40 |

| |

50–59 |

28536 (11.61%) |

376 (11.19%) |

229 (11.56%) |

58.72 |

| |

60–69 |

14337 (5.83%) |

189 (5.62%) |

106 (5.35%) |

54.08 |

| |

70–79 |

7038 (2.86%) |

96 (2.86%) |

59 (2.98%) |

61.46 |

| |

80+ |

3310 (1.35%) |

55 (1.64%) |

34 (1.72%) |

75.56 |

| Female |

0–9 |

3826 (1.56%) |

49 (1.46%) |

33 (1.67%) |

63.46 |

| |

10–19 |

3946 (1.61%) |

53 (1.58%) |

29 (1.46%) |

53.70 |

| |

20–29 |

12485 (5.08%) |

182 (5.42%) |

95 (4.80%) |

55.56 |

| |

30–39 |

20122 (8.19%) |

244 (7.26%) |

175 (8.83%) |

63.64 |

| |

40–49 |

18182 (7.4%) |

232 (6.90%) |

165 (8.33%) |

66.27 |

| |

50–59 |

20647 (8.4%) |

300 (8.93%) |

174 (8.78%) |

61.70 |

| |

60–69 |

13721 (5.58%) |

170 (5.06%) |

113 (5.70%) |

60.11 |

| |

70–79 |

7245 (2.95%) |

103 (3.06%) |

60 (3.03%) |

60.61 |

| |

80+ |

5212 (2.12%) |

80 (2.38%) |

41 (2.07%) |

57.75 |

The study population consisted of respondents with ages ranging from 0.9 to 99.8 years, with a median age of 45.3 [interquartile range (IQR): 32.8–57.1] years. Among the respondents, women accounted for 43.7% (866/1981) of the total sample.. One third of the respondents (33.7%) of the respondents aged 30–59 years; Respondents younger than 20 years older than 70 years accounted for 4.0% and 4.8% separately. The proportions of the respondents received incomplete vaccination series, complete vaccination series and booster vaccination series were 29.2%, 31.9% and 38.9%, respectively (

Table 2).

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate among individuals with past infections in the December 2022 outbreak, Pudong New Area, Shanghai. (n = 1981).

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate among individuals with past infections in the December 2022 outbreak, Pudong New Area, Shanghai. (n = 1981).

| Characteristics |

No. of respondents |

Proportions (%) |

No. of reinfections |

Adjusted reinfection rate (95% CI) |

p |

| Total |

1981 |

100.0 |

260 |

13.12 (11.64–14.61) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

1115 |

56.3 |

161 |

14.69 (12.59–16.79) |

0.025 |

| Female |

866 |

43.7 |

99 |

11.19 (9.11–13.26) |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0–9 |

40 |

2.0 |

2 |

2.74 (0–6.48) |

0.000 |

| 10–19 |

40 |

2.0 |

6 |

8.96 (2.12–15.79) |

|

| 20–29 |

151 |

7.6 |

33 |

13.31 (9.08–17.53) |

|

| 30–39 |

243 |

12.3 |

87 |

21.07 (17.13–25.00) |

|

| 40–49 |

195 |

9.8 |

47 |

12.91 (9.47–16.36) |

|

| 50–59 |

229 |

11.6 |

42 |

10.42 (7.44–13.41) |

|

| 60–69 |

122 |

6.2 |

22 |

10.05 (6.06–14.03) |

|

| 70–79 |

62 |

3.1 |

10 |

8.40 (3.42–13.39) |

|

| 80+ |

33 |

1.7 |

11 |

14.67 (6.66–22.67) |

|

| Vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

| Incomplete |

579 |

29.2 |

88 |

15.20 (12.27–18.12) |

0.022 |

| Complete |

632 |

31.9 |

84 |

13.29 (10.64–15.94) |

|

| Booster |

770 |

38.9 |

88 |

11.43 (9.18–13.68) |

|

3.2. Reinfection rate of SARS-CoV-2 among different populations

A total of 260 respondents reported reinfection during the December 2022 outbreak. The reinfection risk was estimated to be 13.12% [95% CI: 11.64–14.61)] (

Table 2).

The reinfection risk among male respondents (14.69%, 95% CI: 12.59–16.79) was significantly higher than that among female respondents (11.19%, 95% CI: 9.11–13.26). Among different age groups, adults aged 30–39 years had the highest reinfection risk (21.07%, 95% CI: 17.13–25.00), while children younger than 9 years had the lowest reinfection risk (2.74%, 95% CI: 0–6.48)..

A total of 1501 respondents had received at least one dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, with a coverage risk of 75.77%. The reinfection risks for people who had received the incomplete vaccination series, complete vaccination series and booster vaccination series were 15.20% (95% CI: 12.27–18.12), 13.29% (95% CI: 10.64–15.94), and 11.43% (95% CI: 9.18–13.68), respectively.

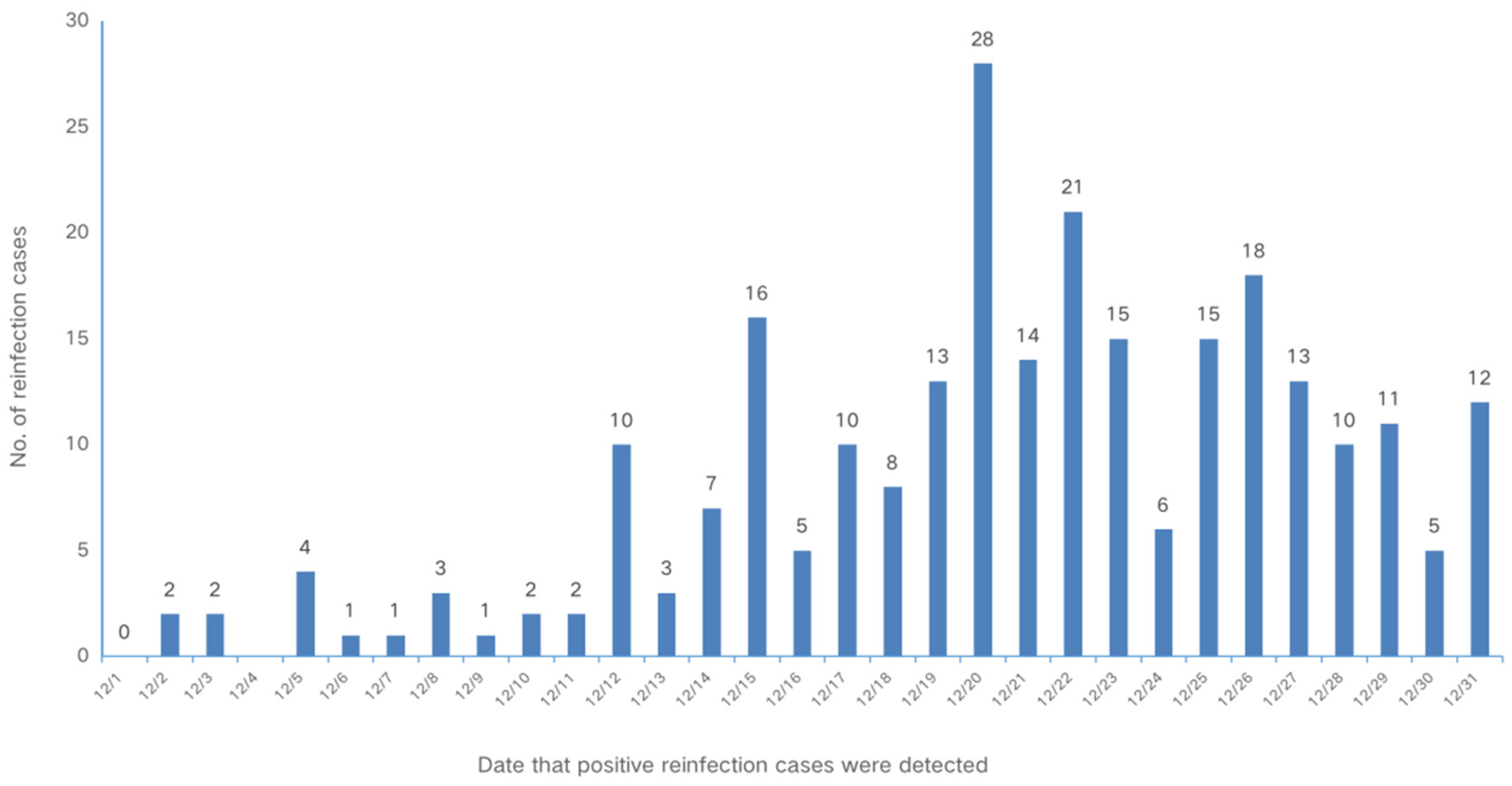

The first reinfection case was detected on December 2. The epidemic curve increased sharply after December 12 and peaked on December 20. The time series of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection for individuals who had a history of previous infection is shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Epidemic curve of 260 reinfection cases in Shanghai, China, 2022.

Figure 2.

Epidemic curve of 260 reinfection cases in Shanghai, China, 2022.

3.3. Factors that influenced reinfection

As showed in the logistic regression model (

Table 3), female sex (aOR = 0.732, 95% CI: 0.557–0.961,

p = 0.0245), an age younger than 9 years (aOR = 0.163, 95% CI: 0.035–0.764,

p = 0.0213) and booster vaccination series (aOR = 0.579, 95% CI: 0.412–0.813,

p = 0.0016) were significantly associated with a decreased risk of reinfection.

Table 3.

Factors that influenced the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate among individuals with past infection in the December 2022 outbreak, Pudong New Area, Shanghai. (n = 1981).

Table 3.

Factors that influenced the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate among individuals with past infection in the December 2022 outbreak, Pudong New Area, Shanghai. (n = 1981).

| Characteristics |

No. of reinfections |

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

p |

| Total |

260 |

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Male |

161 |

REF |

0.0245 |

| Female |

99 |

0.732 (0.557–0.961) |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

| 0–9 |

2 |

0.163 (0.035–0.764) |

0.0213 |

| 10–19 |

6 |

0.664 (0.226–1.949) |

0.4565 |

| 20–29 |

33 |

1.086 (0.509–2.317) |

0.8316 |

| 30–39 |

87 |

2.034 (0.997–4.148) |

0.0510 |

| 40–49 |

47 |

1.156 (0.551–2.425) |

0.7006 |

| 50–59 |

42 |

0.903 (0.429–1.903) |

0.7888 |

| 60–69 |

22 |

0.823 (0.371–1.823) |

0.6305 |

| 70–79 |

10 |

0.643 (0.256–1.616) |

0.3477 |

| 80+ |

11 |

REF |

|

| Vaccination |

|

|

|

| Incomplete |

88 |

REF |

|

| Complete |

84 |

0.741 (0.528–1.042) |

0.0849 |

| Booster |

88 |

0.579 (0.412–0.813) |

0.0016 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

Our study found that the reinfection rate of the Omicron variant among people who had previous SARS-CoV-2 infections within one year was 13.12%. Moreover, a cohort study was conducted among people in the community in the study area, which included over 2,500 non-infected individuals. As of December 2022, the crude infection rate was up to 75% in this cohort, which was over 5 times higher than that among previously infected people. Natural BA.2 infection provided strong protection for people against infection during the Omicron outbreak caused by BA5.2 or BF.7. The reinfection rates among females, children younger than 9 years and people with a booster vaccination history were significantly lower than those among other groups.

4.2. Reinfection rate of omicron

Natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 elicits strong protection against reinfection with the B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta) variants. However, the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant harbours multiple mutations that can mediate immune evasion [

8]. A study in Turkey showed that reinfection was found for 520 (13.0%) of 3992 Omicron sublineages, which is similar to the findings of our study [

11].

Recent studies have found that the risk of reinfection is higher for Omicron than for other strains of SARS-CoV-2 [

20,

21,

22]. According to a meta-analysis from the University of Ferrara in Italy, the reinfection rate of the novel coronavirus gradually increased, with a reinfection rate of 0.57% for Alpha, 1.25% for Delta, and 3.31% for Omicron, which was 5.8 times higher than that of Alpha [

23]. Another study found that the reinfection rate was only 0.7% among people who were infected by Omicron BA.4/BA.5 for the first time. However, if an infected person was first infected with the Delta or Omicron BA.2 strain, then the chances of being reinfected with Omicron BA.4/BA.5 were greater [

24].

One study indicated that the risk of reinfection increased almost 18-fold following the emergence of the Omicron variant compared with Delta [

25]. Moreover, compared with Alpha and Delta, the decrease in antibody protection was greater after infection with Omicron. The effectiveness of antibodies in infected individuals 3 to 5 months after infection with Alpha and Delta still reached 86.6% and 91.3%, respectively. The decrease rate was limited among people infected with Omicron, but the lowest value was still above 60% [

24].

4.3. Reinfection rates among different groups

The reinfection rates across the various age groups were generally comparable, except for the younger population, where the rates were notably lower than those observed in other age groups. A population-level retrospective cohort study conducted in Kuwait from 2020 to 2021 also found that SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was uncommon among children [

26]. A study conducted in France between March 2021 and February 2022 found that people younger than 18 years and older than 40 years had lower rates of reinfection (

p < 0.001) [

21].

A retrospective epidemiological study analysed SARS-CoV-2 reinfection cases in Bahrain between April 1, 2020, and July 23, 2021, obtained from the Bahrain national COVID-19 database of individuals who had 2 positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 at least 3 months apart. The researchers found that a significantly larger proportion of reinfected individuals were male (60.3%,

p <0.0001). Reinfection episodes were highest among those aged 30–39 years (29.7%) [

27]. This finding was consistent with that in our study.

We conducted this study in January 2023, when the second wave of the Omicron variant in China was not completely over. A previous study also showed that the interval between 2 infection events varied by time, strain, vaccine situation and other factors [

2,

6,

28,

29]. Protection conferred by prior infection against reinfection with pre-Omicron variants was initially high and maintained a consistently high level even after a period of 40 weeks [

12]. A study using whole-genome viral RNA sequencing of clinical specimens collected during the initial infection and suspected reinfection from 4 health care workers at the Habib Bourguiba University Hospital that retested positive for SARS-CoV-2 through RT‒PCR after recovery showed a range between 45 and 141 days [

30]. The results of a retrospective longitudinal analysis among health care workers suggested that the first episode of SARS-CoV-2 infection provides strong protection against reinfection, which lasts for at least a year, including during periods of high transmission in the community. At a median follow-up of 38.4 (range: 7.1–55.0) weeks following the initial infection, the cumulative actuarial probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection at 52 weeks was determined to be 2.2% (95% CI, 1.0–4.9%) [

31]. Another study found that the fewest reinfection episodes occurred 3–6 months after the first infection, and most occurred ≥9 months after the initial infection [

27].

4.4. Hybrid immunity against Omicron

Hybrid immunity, particularly against the Omicron variant, has been widely recognized as the most resilient approach to combat SARS-CoV-2 [

32,

33,

34]. Previous research has demonstrated that a combination of naturally acquired immunity through multiple reinfections and vaccine-induced immunity confers significant protection against severe SARS-CoV-2 disease and mortality [

20,

35,

36,

37]. Irrespective of the prevailing virus variant, the most significant risk factor for reinfection was found to be the absence of vaccination [

25,

38].

In Shanghai, vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were first offered in the winter of 2020, followed by the summer of 2011 and winter of 2022. Out of the total respondents, 75.77% (1501/1981) had received vaccination with at least one dose. Booster-vaccinated individuals had the lowest reinfection rate, followed by those who were fully vaccinated. The highest risk of reinfection was observed among unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated people. Evidence has shown that a previous Omicron infection in triple-vaccinated individuals provides high amounts of protection against BA.5 and BA.2 infections [

28]. A study on the incremental protection and durability of infection-acquired immunity against Omicron infection among individuals with hybrid immunity in Canada showed that previous SARS-CoV-2 infections provided added cross-variant immunity from vaccination [

39]. According to a population-level observational study, unvaccinated, incompletely or completely vaccinated patients were slightly more likely to be reinfected than recipients of a third (booster) vaccine dose [

40]. Estimated protection (95% CI) against Omicron infection was consistently significantly higher among vaccinated individuals with prior infection compared with vaccinated infection-naive individuals, with 65% vs. 20% for 1 dose, 68% vs. 42% for 2 doses, and 83% vs. 73% for 3 doses [

20].

In our study, for the first time, we reported the reinfection rate during the first Omicron outbreak after the downgrade of China’s “zero COVID” policy among people who had been infected in the 2022 spring Omicron outbreak in Shanghai. With the ongoing emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants becoming a global concern, immunity plays a crucial role in combating SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Protective immunity, derived from immune memory, serves as a defense mechanism against SARS-CoV-2. Recent studies have highlighted the robustness of hybrid immunity, which combines naturally acquired and vaccine-induced immunity, in providing the highest level of protection against the virus. Our study indicated that protection was strong after natural immunity within one year for different Omicron variant sublineages. Furthermore, evidence of the effectiveness of hybrid immunity was also found, consistent with other studies conducted worldwide.

4.5. Limitations

This study shares limitations commonly associated with retrospective survey and cross-sectional study designs, which include the potential for recall bias and selection bias. Before December 2022, routine PCR testing was performed in the community. Hypothetically, all potential cases would be identified and registered. The sample of our study was from the local PCR registration system. However, a large number of the cases involved migrants, travellers or floating workers who stayed in Shanghai during the 2022 spring outbreak. They had left the city when our survey was conducted after the downgrade of the prevention policy. This was the major reason for the low response rate, especially among young males. On the other hand, after the downgrade of the prevention policy, only a small number of individuals with suspected disease would seek PCR testing or rapid antigen testing. Obviously, asymptomatic individuals and younger or older adults for whom PCR or rapid antigen testing was less convenient had limited opportunities to confirm their own reinfection. Such people may have provided negative answers to the survey. This bias might also be one of the reasons for the lower reinfection rate among younger children and older people.

5. Conclusions

To summarize, our study findings indicate that individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection during the spring 2022 outbreak in Pudong had a significantly lower risk of reinfection compared to the general population. This observation highlights the protective effect of natural infection-induced immunity and hybrid immunity, which includes both natural infection and vaccination, in reducing the risk of subsequent reinfection caused by different Omicron sublineages. Booster vaccination (hybrid immunity) provides strong protection against SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

Author Contributions

YZ, WZ, LH and CY conceived and designed the study. CY, AZ, GZ, HX and ZL drafted the paper. KW, AZ, GZ and YJ did the analysis, and all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and agreed to submit the final version for publication. KW, AZ, GZ and WZ edited the questionnaire. HX, CX, YW, CY, KW and YJ collected and verified the data. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Pudong New Area Public Health Peak Discipline “Infectious Disease” Project (PWYggf2021-01). Chuchu Ye received funding from the Shanghai “Rising Stars of Medical Talents” Youth Medical Talents Public Health Leadership Program and Pudong New Area Health System Discipline Leader Training Program (PWRd2021-15).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for this research was given by the Ethical Review Board of Pudong New Area Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (PDCDC). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents surveyed. All potentially identifying factors were removed to prevent the identification of individuals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, YZ, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the investigation team at Pudong New Area CDC in conducting this survey. We also thank Dr. Zhibin Peng and Dr. Qin Ying of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/; 2022.

- Wu J, Nie J, Zhang L, Song H, An Y, Liang Z, et al. The antigenicity of SARS-CoV-2 delta variants aggregated 10 high-frequency mutations in RBD has not changed sufficiently to replace the current vaccine strain. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00874-7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants, https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants; 2023 [accessed 16 March 2023].

- World Health Organization. Classification of omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern, https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern; 2021.

- Breathnach AS, Duncan CJA, Bouzidi KE, Hanrath AT, Payne BAI, Randell PA, et al. Prior COVID-19 protects against reinfection, even in the absence of detectable antibodies. J Infect 2021;83:237–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.024. [CrossRef]

- Abo-Leyah H, Gallant S, Cassidy D, Giam YH, Killick J, Marshall B, et al. The protective effect of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in scottish healthcare workers. ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00080–2021. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00080-2021. [CrossRef]

- To KK, Hung IF, Ip JD, Chu AW, Chan WM, Tam AR, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e2946–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Coyle P, Tang P, Yassine HM, Al-Khatib HA, et al. Protection of omicron sub-lineage infection against reinfection with another omicron sub-lineage. Nat Commun 2022;13:4675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32363-4. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 2022;602:657–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04385-3. [CrossRef]

- Deng L, Li P, Zhang X, Jiang Q, Turner D, Zhou C, et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2022;12:20763. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24220-7. [CrossRef]

- Özüdoğru O, Bahçe YG, Acer Ö. SARS CoV-2 reinfection rate is higher in the omicron variant than in the alpha and delta variants. Ir J Med Sci 2022;192:751–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03060-4. [CrossRef]

- Stein C, Nassereldine H, Sorensen RJD, Amlag JO, Bisignano C, Byrne S, et al. Past SARS-CoV-2 infection protection against re-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2023;401:833–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02465-5. [CrossRef]

- Lai S, Ruktanonchai NW, Zhou L, Prosper O, Luo W, Floyd JR, et al. Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020;585:410–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2293-x. [CrossRef]

- Baker MG, Wilson N, Blakely T. Elimination could be the optimal response strategy for covid-19 and other emerging pandemic diseases. BMJ 2020;371:m4907. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4907. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Zheng C, Wang L, Geng M, Chen H, Zhou S, et al. Interpretation of the protocol for prevention and control of COVID-19 in China (Edition 8). China CDC Wkly 2021;3:527–30. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2021.138. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liu F, Cui J, Peng Z, Chang Z, Lai S, et al. Comprehensive large-scale nucleic acid-testing strategies support China’s sustained containment of COVID-19. Nat Med 2021;27:740–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01308-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Rodewald L, Lai S, Gao GF. Rapid and sustained containment of covid-19 is achievable and worthwhile: implications for pandemic response. BMJ 2021;375:e066169. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-066169. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Chen Q, Feng L, Rodewald L, Xia Y, Yu H, et al. Active case finding with case management: the key to tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;396:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31278-2. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Deng X, Fang L, Sun K, Wu Y, Che T, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and transmission dynamics of the outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Shanghai, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2022;29:100592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100592. [CrossRef]

- Carazo S, Skowronski DM, Brisson M, Sauvageau C, Brousseau N, Gilca R, et al. Estimated protection of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection against reinfection with the omicron variant among messenger rna-vaccinated and nonvaccinated individuals in Quebec, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2236670. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36670. [CrossRef]

- Bastard J, Taisne B, Figoni J, Mailles A, Durand J, Fayad M, et al. Impact of the omicron variant on SARS-CoV-2 reinfections in France, March 2021 to February 2022. Euro Surveill 2022;27:2200247. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2022.27.13.2200247. [CrossRef]

- Pulliam JRC, Van Schalkwyk C, Govender N, Von Gottberg A, Cohen C, Groome MJ, et al. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of omicron in South Africa. Science 2022;376:eabn4947. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn4947. [CrossRef]

- Flacco ME, Martellucci CA, Baccolini V, De Vito C, Renzi E, Villari P, et al. Risk of reinfection and disease after SARS-CoV-2 primary infection: meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest 2022;52:e13845. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13845. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha LB, Foster C, Rawlinson W, Tedla N, Bull RA. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev Med Virol 2022;32:e2381. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2381. [CrossRef]

- Sacco C, Petrone D, Del Manso M, Mateo-Urdiales A, Fabiani M, Bressi M, et al. Risk and protective factors for SARS-CoV-2 reinfections, surveillance data, Italy, August 2021 to March 2022. Euro Surveill 2022;27:2200372. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2022.27.20.2200372. [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad F, Abdulkareem A, Alsharrah D, Alkandari A, Bin-Hasan S, Al-Ahmad M, et al. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in a paediatric cohort in Kuwait. BMJ Open 2022;12:e056371. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056371. [CrossRef]

- Almadhi M, Alsayyad AS, Conroy R, Atkin S, Awadhi AA, Al-Tawfiq JA, et al. Epidemiological assessment of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Int J Infect Dis 2022;123:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.075. [CrossRef]

- Hansen CH, Friis NU, Bager P, Stegger M, Fonager J, Fomsgaard A, et al. Risk of reinfection, vaccine protection, and severity of infection with the BA.5 omicron subvariant: a nation-wide population-based study in Denmark. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23:167–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00595-3. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang X, Shen XR, Geng R, Xie N, Han JF, et al. A 1-year longitudinal study on COVID-19 convalescents reveals persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 humoral and cellular immunity. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022;11:902–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2022.2049984. [CrossRef]

- Gargouri S, Souissi A, Abid N, Chtourou A, Feki-Berrajah L, Karray R, et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 symptomatic reinfection in four healthcare professionals from the same hospital despite the presence of antibodies. Int J Infect Dis 2022;117:146–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Dhumal S, Patil A, More A, Kamtalwar S, Joshi A, Gokarn A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection after previous infection and vaccine breakthrough infection through the second wave of pandemic in India: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis 2022;118:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.02.037. [CrossRef]

- Russell RS. Hybrid immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Viral Immunol 2022;35:391. https://doi.org/10.1089/vim.2022.0116. [CrossRef]

- Andreano E, Paciello I, Piccini G, Manganaro N, Pileri P, Hyseni I, et al. Hybrid immunity improves B cells and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nature 2021;600:530–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04117-7. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya M, Sharma AR, Dhama K, Agoramoorthy G, Chakraborty C. Hybrid immunity against COVID-19 in different countries with a special emphasis on the Indian scenario during the omicron period. Int Immunopharmacol 2022;108:108766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108766. [CrossRef]

- Halfmann PJ, Kuroda M, Maemura T, Chiba S, Armbrust T, Wright R, et al. Efficacy of vaccination and previous infection against the Omicron BA.1 variant in syrian hamsters. Cell Rep 2022;39:110688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110688. [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaiby M, Krissaane I, Al Seraihi A, Alshenaifi J, Qahtani MH, Aljeri T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate and outcomes in Saudi Arabia: a national retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis 2022;122:758–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.025. [CrossRef]

- Diani S, Leonardi E, Cavezzi A, Ferrari S, Iacono O, Limoli A, et al. SARS-CoV-2-the role of natural immunity: a narrative review. J Clin Med 2022;11:6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216272. [CrossRef]

- Lutrick K, Rivers P, Yoo YM, Grant L, Hollister J, Jovel K, et al. Interim estimate of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among adolescents aged 12-17 years—Arizona, July-December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1761–5. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm705152a2. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Li Y, Mishra S, Bodner K, Baral S, Kwong JC, et al. Effect of the incremental protection of previous infection against omicron infection among individuals with a hybrid of infection- and vaccine-induced immunity: a population-based cohort study in Canada. Int J Infect Dis 2023;127:69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.11.028. [CrossRef]

- Medić S, Anastassopoulou C, Lozanov-Crvenković Z, Vuković V, Dragnić N, Petrović V, et al. Risk and severity of SARS-CoV-2 reinfections during 2020-2022 in Vojvodina, Serbia: a population-level observational study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022;20:100453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100453. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).