“One of the most significant developments in contemporary medicine has been the increasing recognition that the soma and the psyche are not distinct and unrelated, but are so closely bound together as to make proper investigation of both a necessary part of the management of disease.”

Frederic Speer (The allergic tension-fatigue syndrome, 1954)

1. Introduction

In 1954, Frederic Speer, head of Pediatric Allergy at the University of Kansas, published a seminal study focused on a new clinical entity, the allergic tension-fatigue syndrome. Speer allergic tension-fatigue syndrome (SATFS) was characterized by allergy-like symptoms such as rhinitis and skin rashes that were either triggered or worsened by exposure to certain foods or environmental factors: muscle tension, headache, chronic fatigue, and a particular behavior. This particular behavior, displayed by either children or adults, included symptoms such as hyperkinesis, hyperesthesia (i.e., insomnia), restlessness, and distractibility. Interestingly, these symptoms are very similar to recent descriptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the most prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder worldwide [

1]. ADHD symptoms typically encompass hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity. Speer also considered that “the behavior disturbance of allergic children constitutes a primary allergic disorder of the nervous system” [

2].

The three cardinal ideas underlying the SATFS are that: 1) the behavioral manifestations of the syndrome are very similar to current descriptions of ADHD; 2) the clinical manifestations of this condition, including the behavioral manifestations, are a consequence of allergic pathophysiology; and 3) it is secondary to a cholinergic imbalance. Unfortunately, neither the SAFTS nor the cholinergic imbalance has convincingly been proven [

3,

4].

In this conceptual paper, we offer a disruptive view of the SATFS and the underlying pathological explanation by suggesting that: 1) the SATFS is indeed a good clinical picture of some patients with ADHD and a typical comorbidity displayed by these patients, allergy; 2) the SATFS (ADHD for us) is a systemic disease; and 3) the role of neuroinflammation and a "forgotten" neurotransmitter, histamine, is key for understanding the SATFS. We begin by describing the clinical picture and the underlying pathophysiology of the SATFS. Next, we summarize the role of histamine in the body and brain. Finally, we revisit the SAFTS and present emerging evidence of the key role of histamine in ADHD, and its comorbidities.

2. The Speers allergic tension-fatigue syndrome (SATFS)

As said before, the SATFS includes behavioral and systemic, constitutional manifestations.

2.1. Behavioral allergic traits

In his seminal works, Speer reported that some allergic patients, either children or adults, tended to initially "overdo and overreact", and then to become strongly fatigued [

2,

5]. In other words, he suggested that a distinct pattern of behavior was typical of some allergic individuals. He included this pattern of behavior within the SATFS [

5,

6]. Both behavioral components (tension and fatigue) of the SATFS had two aspects: 1) a motor component; and 2) a sensory component [

2,

6]. The symptoms of both components are summarized in

Table 1.

In his original description of the behavior of people with the SATFS, he said “While some victims of allergic fatigue may be said to be tired, others may more properly be regarded as torpid. Rather than muscular fatigue, there seems to be a depression of sensory and psychic function, and affected children may be described as sluggish, inactive, sleepy, and apathetic” [

2].

2.2. Constitutional allergic traits

In addition to the disturbed (tension-fatigue) behavior typical of allergic children, Speer also considered the “constitutional allergic traits”. In other words, the original constitutional, systemic syndrome depicted by Speer not only included allergic and motor fatigue, but also torpor, “asthma, gastrointestinal allergy, eczema, and nasal allergy” and a “less well defined and less well known phenomena” that he interpreted as “evidence of increased parasympathetic or cholinergic activity” which included hyperhidrosis, headache (“characteristically unilateral and frontal”), edema (particularly in the infraorbital and malar areas), lacrimation, (hyper)salivation, and increased bladder tone (increased urinary frequency and enuresis) [

2].

2.3. A misstep? Speer's cholinergic theory

The first convincing hypotheses to explain the SATFS in which children with atopic disorders developed hyperactivity and hyperesthesic behaviors was an increased cholinergic activity at the cortical level triggered by the allergic stimulus [

2].

Later on, Marshall (“what are the biochemical or brain mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of ADHD with an etiology of allergy?”) expanded Speer’s cholinergic hypothesis by suggesting that the relationship between allergy and ADHD was better explained by a cholinergic/adrenergic activity imbalance in the central nervous system (CNS) [

6]. He stressed that the increased nasal and throat mucus and bronchospasm (respiratory system), pylorospasm, cramping and constipation (digestive system), were symptoms typically associated with increased cholinergic tone. This cholinergic hyper-response, induced by an allergen, would lead to the predominance of cholinergic activity over adrenergic activity in genetically predisposed patients, and explained both excitatory and attention deficit symptoms. Furthermore, this cholinergic-adrenergic imbalance would be potentiated, independently of the allergy, by all those stressors included in the patient's environment. Some authors reported some data giving partial support to this hypothesis [

7].

In any case, what is quite surprising is that although Speer was describing a syndrome characterized by allergy, he did not mention either histamine, nor IgE, which are probably the most relevant biomarkers in any pathology involving allergy. As a matter of fact, the initial symptomatic treatment of most allergic pathologies is an antihistamine. But, what do we know about histamine?

3. Histamine

Histamine is an imidazole amine that is involved in local immune responses (related to leukocyte and eosinophil chemotaxis), the digestive system, and the CNS, where it acts as a neurotransmitter.

Although our body synthesizes histamine, foods also contain varying amounts of histamine. Furthermore, histamine has the potential to be toxic. The deleterious effects of excessive histamine ingestion were initially referred to as scombrotoxicosis more than 60 years ago, and is currently known as histamine intoxication or histamine poisoning [

8]. Histamine poisoning was related to almost exclusively with the consumption of spoiled fish, particularly, poorly transported tuna. It is characterized by occurring in outbreaks, having a short incubation period (around 20 minutes post-ingestion), and includes symptoms of low/moderate severity that remit in a few hours. The symptoms are closely linked to several physiological functions of histamine, affecting the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), the skin (e.g., rash, redness, urticaria, pruritus, edema, local inflammation), and the cardiovascular (hypotension) and neurological (e.g., headache, palpitations) system [

8].

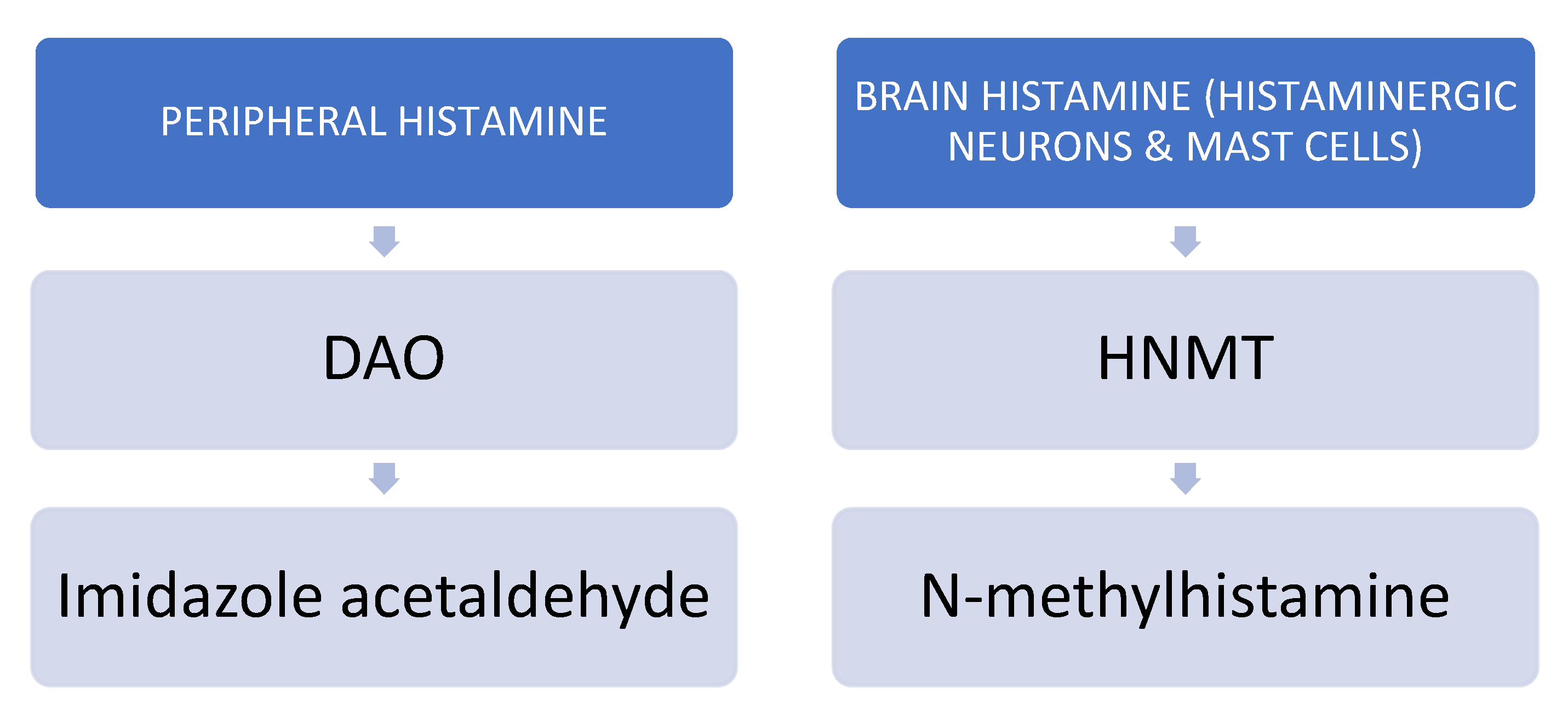

In order to avoid a potential intoxication or the deleterious effects of excessive histamine in the body, histamine is metabolized by two main enzymes: diamine oxidase (DAO), and histamine-N-methyltransferase (HNMT) [

9,

10]. HNMT is responsible for the degradation of intracellular histamine, whereas DAO metabolizes histamine extracellularly [

8]. Whenever the activity of either DAO or HNMT is insufficient, histamine is accumulated extracellularly or intracellularly, respectively. Under physiological conditions, DAO has low activity in brain, and mainly catabolizes histamine in peripheral tissues. However, whenever the activity of HNMT is inhibited, DAO may help by metabolizing brain histamine into imidazole acetaldehyde [

11,

12]. See

Figure 1.

3.1. Body histamine.

Apart from its action in the CNS (see below), histamine is mainly involved in local immune responses, and the digestive system. The best-known histamine receptors, H1R and H2R, are low affinity, classic drug targets for allergy and gastric ulcer, respectively. Lesser-known, but with high therapeutic potential, H3R, and H4R “are high-affinity receptors in the brain and immune system, respectively” [

13]. H1R are expressed in several cells (including mast cells), and are involved in Type 1 hypersensitivity reactions. H2R are mainly involved in Th1 lymphocyte cytokine production. H3R play a role in the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) function. H4R are highly expressed on mast cells, and their stimulation increases histamine and cytokine production [

14].

Histamine is involved in several somatic diseases. Furthermore, it is possible that histamine plays a major role in other disorders, yet unknown. To get an idea of the relevance of the histaminergic system, it suffices to point out the results of a recent study stemming from a retrospective analysis revealing that cancer patients who took antihistamines during immunotherapy for treating the cancer had significantly improved survival. This observation led this team to find that HR1 was frequently increased in the tumor microenvironment, thus inducing T cell dysfunction. Furthermore, antihistamine treatment restored immunotherapy response by reverting macrophage immunosuppression, and revitalizing T cell cytotoxic function. In other words, clinical manifestations of allergy, via H1R, facilitated both tumor growth, and induced immunotherapy resistance. Thus, high histamine levels or pre-existing allergy in cancer patients may dampen immunotherapy responses. Accordingly, antihistamines might be used as adjuvant agents for combinatorial immunotherapy [

15].

Apart from this very relevant study, histaminergic drugs are commonly prescribed for both allergic and gastric diseases. Regarding allergy, since its discovery in 1911, histamine has traditionally been recognized as a critical mediator in allergic diseases such as acute pruritus, atopic dermatitis, and allergic asthma. Indeed, antihistamines are fundamental for treating these conditions. In addition, histamine has proinflammatory effects, which appear to be mediated by H1R. Thus, histamine mediates both the early and late-phase reactions of an allergic response. The use of first-generation antihistamines was limited because they penetrate the BBB, and cause sedation, among others side effects. Second-generation antihistamines (i.e., ebastine) do not penetrate the BBB, and thus have improved tolerability [

16]. In addition to H1R, H4R also play a critical role in the development, progression and modulation of many allergic diseases [

14]. Given that antihistamines targeting H1R alone are not entirely effective in the treatment of allergic diseases, H4R antagonists might also be used as they have shown promising effects in preclinical and clinical studies in the treatment of several allergic diseases [

14].

Regarding the digestive system, H2R antagonists are yet considered traditional treatments for a variety of gastric diseases such as gastritis or gastro-esophageal reflux given their gastroprotective effect. One of the major uses is the prevention or treatment of peptic ulcers, or bleeding associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) use [

17]. More recent research also suggests that H2R antagonists can also improve the dysbiosis secondary to NSAID use [

18].

Finally, the use of drugs targeting histamine receptors is increasingly used in a CNS neurological disorder, migraine. Histamine has a vasodilative effect. Therefore, some authors have suggested that histamine may play a role in the pathophysiology of migraine. There is reduced susceptibility for migraine attacks during evenings and night, which corresponds with less central histaminergic firing [

19]. Furthermore, a recent review stressed that histamine is critical in migraine pathogenesis via an inflammation pathway. The authors suggested that, given that H3 receptors act as autoreceptors/ heteroreceptors, lowering the release of histamine, drugs targeting this receptor may have anti-nociceptive and anti-neurogenic inflammatory actions that could be used for treating migraine [

20].

3.1.1. Histamine intolerance (HIT).

Excessive body histamine can be secondary to: 1) the ingestion of histamine-rich food that surpasses the catabolic capacity of the subject; 2) the intake of alcohol or other drugs that either release histamine and/or block the DAO; and 3) a genetic predisposition to a deleterious capacity for catabolizing histamine (DAO deficiency). All three reasons may derive in the same clinical picture, but only the last two reasons are related to histamine intolerance (HIT). HIT is a non-immunological disease characterized by an impaired ability to metabolize ingested histamine. HIT may include both gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal non-specific symptoms such as food intolerance, allergies, and mastocytosis, among others [

9]. HIT symptoms are indeed similar to those of histamine intoxication [

21,

22], but less acute and severe, and more prolonged.

HIT symptoms are linked to the various physiological functions of histamine in the body, affecting the skin (e.g., flushing, redness, rash, urticaria, pruritus), the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, intolerance of histamine-rich food and alcohol), the respiratory (e.g., rhino-conjunctival symptoms; asthma, particularly during exercise), the cardiovascular (hypotension, arrhythmia), the reproductive (e.g., dysmenorrhea), and neurological (e.g., chronic headache, migraine) bodily functions [

23]. Please recall that all these systems are exactly the same involved in the SATFS. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of HIT is usually difficult because symptoms are usually unspecific, and mild. Furthermore, the prevalence of HIT is probably underestimated, given the multifaceted nature, similarity of the symptoms with allergic diseases and other disorders.

Currently, a positive response to a low-histamine diet is the most relevant was for establishing the diagnosis. Similarly, following a low-histamine diet is the main therapeutic option for avoiding HIT symptoms [

8]. But what is the main ethological factor in HIT?

3.1.2. DAO deficiency and histamine-related diseases including histamine intolerance (HIT)

An impaired histamine degradation based on reduced DAO activity is the most frequent cause of HIT. DAO activity may be the result of genetic (DAO deficiency), and environmental (intake of alcohol and/or drugs inhibiting DAO) factors. DAO deficiency can lead to an excessive accumulation of histamine in the body, which has been linked to a number of symptoms and diseases, including (seasonal) allergic diseases [

24] and asthma in some people [

25]. Histamine can cause airway constriction, which can worsen asthma symptoms. Therefore, DAO deficiency may be a contributing factor in the development and severity of asthma. In a recent interesting study, reduced DAO serum levels leading to occurrence of HIT symptoms were significantly more frequent in patients with atopic eczema than in controls [

23]. DAO deficiency has also been related to HIT, and other food allergies/intolerance, particularly lactose intolerance [

26]. In another study, the authors reported a very close relationship between DAO deficiency and non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), thus leading to most severe migraine symptomatology, as both gluten and histamine are commonly involved within migraine [

27]. Histamine present in food is one of the main triggers of food allergies, and DAO deficiency may increase susceptibility to these allergies. Histamine is an inflammatory biomarker involved in local immune responses (related to leukocyte and eosinophil chemotaxis), but is also an MAO substrate [

28]. Another typical medical condition associated with DAO deficiency is migraine. Indeed, more than 85% of patients affected by migraine display DAO deficiency [

29]. Furthermore, DAO deficiency appears to be very frequent in patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia [

30].

There are several candidate tests to detect DAO deficiency. However, their informative value is questionable, as the DAO expression and activity depends on the interplay between genes and environment [

10]. Furthermore, DAO has a higher expression than HNMT, being the main barrier for the intestinal absorption of histamine [

31]. At least in the Caucasian population, the SNPs that can most directly cause DAO deficiency are rs10156191, rs1049742, rs2052129, and rs1049793 [

10,

30].

To treat DAO deficiency, dietary supplements containing the DAO enzyme have been developed. These supplements have been used successfully in reducing the symptoms of allergic diseases and asthma in some patients. However, it is important to note that food supplements should not replace a healthy, balanced diet. Indeed, a histamine-free diet is the treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and HIT [

32].

In conclusion, DAO deficiency may be related to an increased susceptibility to allergic diseases and asthma, among others. Excessive accumulation of histamine in the body can lead to more severe allergic reactions and worsen asthma symptoms. Dietary supplements containing the enzyme DAO may help reduce symptoms in some patients, but it is important to follow a healthy, balanced diet and seek medical attention if symptoms persist. Other therapeutic options such as DAO supplementation, antihistamines or probiotics are considered as complementary treatments.

3.2. Brain (CNS) Histamine.

There is increasing evidence of the relevance of histamine in the CNS, where it acts as a neurotransmitter. In the brain, histamine is mainly produced by a group of tuberomamillary neurons concentrated in the posterior hypothalamus (TNM), which project practically to the whole CNS, and a limited number of mast cells throughout the CNS [

13,

19,

33]. In mammals, these neurons emerge late and mature slowly [

33,

34]. CNS histaminergic neurons play a key role in the regulation of memory, learning, locomotion, circadian rhythms, and feeding, among others [

35].

Both H1R and H2R are relevant postsynaptic receptors in the CNS, as they mediate some of the central effects of histamine such as alertness and wakefulness. H3R is a pre- and postsynaptic receptor. H3R regulates release of histamine and many other neurotransmitters (i.e., GABA, glutamate, and serotonin). H4R is found in microglia and cerebral blood vessels. The expression of H4R in neurons is not yet well established [

13]. See

Table 2.

A recent review focused on the role of the histaminergic system in neuropsychiatric disorders [

36]. Curiously, the authors reported strong evidence linking histamine with different neuropsychiatric disorders traditionally associated with the dopamine system such as Tourette syndrome, Parkinson syndrome, Alzheimer disease or narcolepsy, but there was not a single word about ADHD. However, a couple of articles stressed that the inhibition of HNMT may be used in the treatment of ADHD [

37,

38]. To our knowledge, there is not a single study directly linking DAO deficiency with ADHD.

Furthermore, there are several treatments for CNS disorders targeting histaminergic receptors: H1R antagonists have been used to treat insomnia. Unfortunately, they require some precautions due to potential side effects. Indeed, the use of first-generation H1R antagonists, capable of crossing the BBB, was limited by sedation. H2R antagonists have shown some efficacy in schizophrenia, but their use is limited nowadays. An H3R antagonist, Pitolisant, is used to treat hypersomnia and narcolepsy. Finally, H4R ligands may play a role in neuroimmunological disorders and neurodegenerative disorders (via inflammatory pathways), but clinical tests are lacking [

13].

In theory, somatic (blood) histamine does not pass the BBB. However, during development, the BBB is permeable to histamine. Accordingly, DAO deficiency may influence not only a series of somatic alterations, such as gastric or allergic manifestations, but also some manifestations at the brain, such as ADHD symptoms. Indeed, there is a link between DAO deficiency and migraine, a neurological pathology in which 85% of patients have DAO deficiency, which strongly suggests an action at the cerebral level. Thus, “systemically given histamine may elicit, maintain, and aggravate headache” [

19]. Furthermore, given that histamine does not penetrate the BBB, the authors suggested that histamine might “influence hypothalamic activity via the circumventricular organs that lack BBB”.

4. The Speer allergic tension-fatigue syndrome (SATFS) syndrome re-visited.

To our knowledge, there are no previous studies suggesting the hypothesis that the SATFS is indeed a good clinical description of some patients with ADHD. Indeed, Speer [

2,

5] stressed that the tension-fatigue syndrome was the result of the combination of: 1) a behavioral syndrome that he said was indeed a “primary allergic disorder of the nervous system”; and 2) a systemic (constitutional) syndrome (more than a disease) involving several apparatuses, but particularly, the allergic system.

In this section we will defend this hypothesis by stressing that: 1) the typical behavior of patients with SATFS is very similar to the current description of the cardinal symptoms of ADHD; 2) the somatic component of the SATFS fits with the typical medical comorbid conditions of patients with ADHD; and 3) the frequent comorbidity with this particular - and no other - profile of somatic conditions and ADHD is better explained by histamine than by acetylcholine. But on what evidence is our hypothesis based?

4.1. A groundbreaking vision: Could the behavior of patients with SATFS indeed be a description of ADHD?

As stated above, the SATFS is a syndrome including two components: a typical behavior, and some health conditions. Regarding the typical behavior of patients with SATFS, as expressed in

Table 1, most of the behavioral symptoms included in the SATFS are typical symptoms of ADHD. The SATF syndrome includes a typical behavior with: 1) a motor component (hyperkinesis): exaggerated, accelerated, and continuous motor function; impatient, talkative, fidgety, poorly coordinated, and accident prone; and 2) a sensory component (hyperesthesia): insomnia, irritability, distractibility, short attention span, excitability, and unusual sensitivity (oversensitivity) to innocuous stimuli (i.e. noise and temperature change, oversensitivity to pain) [

2,

6]. But aren't the SATFS symptoms typical symptoms of ADHD, including a typical feature of its cousin-sibling, autism spectrum disorders?

The hyperkinetic component is clearly reminiscent of the hyperactivity component of ADHD, while the hypersensitive component clearly alludes to symptoms of the inattentive component of ADHD (“The essential characteristics of allergic hypekinesis are exaggeration and acceleration of motor function. All muscular activity is likely to be jerky, quick, and overdone. […] hyperkinetic allergic children are often rather poorly coordinated, clumsy, and accident-prone. They are commonly deficient in manual skills, and although their school work is generally good, they often receive poor marks in writing, art work and crafts. There is evidence that their poor coordination may at times extend to speech function, with resultant stuttering and related problems. […] Teachers find the child to have a short attention span and to be timid, restless, and distractible. Grades often suffer, and it is a commonplace comment of both parents and teachers that “he could learn if he would only pay attention”. Since these children neither understand themselves nor are understood by their elders, it is not uncommon to find them to be sullen and negativistic and convinced that the world is against them. […]. But a large number of them remain retiring, oversensitive, insecure and unhappy - and unrecognized victims of constitutional allergy”) [

2].The unusual sensitivity to stimuli is more typically found in patients with ASD, but is also present in patients with ADHD.

The fatigue sensory component of the SATFS (being inactive, in a torpor, sluggish, sleepy, and apathetic state) clearly recalls either some inattentive symptoms or even the symptoms included within the concept of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (SCT) [

39]. Furthermore, the unusual sensitivity to stimuli is more typically found in patients with ASD, but is also present in patients with ADHD. As a matter of fact, Speer recognized that a cluster of behaviors recalling hyperkinesis emerged from factor analysis [

2]. So, why did Speer not allude to the concept of ADHD when describing the SATFS?

The most plausible explanation is that, although several authors coined different terms for hyperactive children before 1950, including Franz Kramer and Hans Pollnow, it was not until the sixties with the work by Stella Chess that ADHD became notorious in the scientific community [

40]. Indeed, ADHD was first included in the third version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980. Accordingly, it was virtually impossible for an expert on pediatric allergy, but not psychiatry, to describe a parallel with the behavioral description of the "allergic tension- fatigue syndrome", and the incipient conceptualization of ADHD by early alienists.

4.2. The constitutional component of SATFS: ADHD as a systemic disease. What is the evidence?

In their original studies, Speer stressed that the behaviors of allergic children “constitute a primary allergic disorder of the nervous system” [

2]. In other words, he stressed that the behavior itself was part of a systemic (allergic) disease. By accepting that the SATFS corresponds to the clinical description of ADHD is right, we are also accepting the concept that ADHD should be viewed as a systemic disease. Indeed, there is increasing literature suggesting that ADHD may be viewed as a systemic inflammatory disease, in the same vein as depression was previously depicted [

41]. The norm is that people with ADHD have comorbidities with other disorders, both psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Recent evidence stemming from three ground-breaking studies curiously stressed similar comorbidities in the same systems. In the first of these studies, the authors focused only on frequent disorders with well-documented large-scale genetic and epidemiological evidence for association with ADHD [

42]. They grouped the comorbidities into three principal groups: (1) cardiometabolic (obesity, coronary heart disease, and type 2 diabetes); (2) immune-inflammatory-autoimmune (asthma, dermatitis, Chrohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis); and (3) neuropsychiatric (migraine, insomnia, epilepsy, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, alcohol intake and smoking, and autism spectrum disorder). Interestingly, the allergic and behavior symptoms included in the SATFS are included within these comorbidities. The presence of these comorbidities can further complicate the diagnosis and management of ADHD.

In the second study, the authors tested whether or not ADHD polygenic risk scores (PRS) were associated with mid-to-late life somatic diseases in a general population sample [

43]. They included 16 diseases particularly prevalent during middle age, and again, they grouped them into the same groups: 1) cardiometabolic (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, obesity, and type-2 diabetes); (2) autoimmune-inflammatory disease (type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis); and (3) neurological conditions (migraine, epilepsy, dementia, Parkinson disease and parkinsonism, and sleep disorder). They found that higher ADHD-PRS were associated with increased risk of seven somatic conditions (that were, in order of relevance: type 1 diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and migraine), thus concluding that ADHD conferred the risk for these comorbid outcomes, even in the absence of drug treatment for ADHD.

The third study focused on the phenotypic and etiological associations between ADHD and a several somatic conditions across adulthood by doing a register study with a final sample of nearly 5 million individuals in Sweden [

44]. Stronger cross-disorder associations were found for nervous system (sleep disorders, Parkinson disease, dementia, migraine, epilepsy), respiratory (asthma, EPOC), musculoskeletal (back pain), and metabolic diseases, but also genitourinary, circulatory, gastrointestinal, and skin diseases. They found that ADHD was associated in 34 out of the 35 (97%) conditions studied. Most associations were explained by shared genetic factors, with the exception of associations with nervous system and age-related health conditions. Within the nervous system, an exception was migraine, which showed almost complete genetic overlap with ADHD. The authors stressed the relevance of assessing the presence of physical diseases in ADHD patients.

In conclusion, all these studies suggest that ADHD is particularly comorbid with other neuropsychiatric, cardiometabolic, and immune-inflammatory-autoimmune conditions. Psychiatric comorbidities that are commonly associated with ADHD include sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome [

45], depression and anxiety disorders [

46], and substance use disorders [

47]. These disorders can significantly impact the quality of life and cognitive functioning of individuals with ADHD. Regarding the comorbidity with cardiovascular disease, several studies have demonstrated a significant association between ADHD and obesity, with higher rates of obesity reported in both children and adults with ADHD compared to individuals without ADHD [

48]. But the immune-inflammatory-autoimmune conditions were the ones more clearly depicted in the initial description of the SATFS. Accordingly, we expand on this relationship.

4.2.1. ADHD and immune-inflammatory-autoimmune comorbidities

All the allergic (atopic) symptoms included in the SATFS are frequently reported by people diagnosed with ADHD. If our hypothesis that the description of the SATFS corresponds to the current concept of ADHD, it is not surprising that Speer included the allergic symptoms within his concept of the SATFS. The first authors to draw attention to the high prevalence of atopic diseases in patients with ADHD were Geschwind (1985) and Marshall (1989). Geschwind proposed a causal relationship between non-right-handedness, immune disorders, ADHD and learning disabilities, via a prenatal exposure to high levels of testosterone whose effects would involve alterations of the immune system, and reading and motor alterations at the CNS [

49,

50,

51]. Four years later, Marshall (1989) carried out an exhaustive study of the "allergic tension-fatigue syndrome". He expanded Speer’s cholinergic hypothesis and suggested that the bridge between ADHD and allergy was a cholinergic-adrenergic imbalance. In short, both Speer and Marshall speculated on a possible neuro-immunological etiology common to ADHD and atopy.

Since the 1990s, several studies have emerged testing the association between atopia (allergy) and ADHD. Regarding the relationship between atopic dermatitis and ADHD, most authors reported an association [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], but some not [

3,

4,

61]. Again, regarding the relationship between asthma and ADHD, most authors report an association [

54,

58,

59,

60,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66], but some not [

3,

4,

52,

61,

67,

68]. Here, it is interesting to stress that the drug treatment of asthma may act as a confounding variable between ADHD and asthma. Thus, some authors have reported a negative association [

64,

66], whereas others have reported a positive relationship [

69]. Finally, regarding the relationship between allergic rhinitis and ADHD, most studies report a positive relationship [

54,

55,

58,

59,

61,

70,

71].

In any case, two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses provided convincing evidence that ADHD is related to atopic diseases (i.e., asthma, atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis) [

72,

73]. An even more recent study integrating information from two meta-analyses concluded that atopic diseases were not only associated with ADHD, but also with ADHD symptom severity [

74]. In conclusion, we may say that, even if there is not a definitive relationship between ADHD and atopic diseases, most of the evidence suggest that this may be the case.

Finally, there is also increasing evidence about the relationship between ADHD and auto-immune disorders [

75]. As stressed before, patients with ADHD had a higher prevalence of autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease [

42,

43]. The exact mechanism underlying the relationship between ADHD and autoimmune diseases is not yet fully understood. However, chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation may probably play a role in the pathophysiology of both conditions. In particular, some studies have found increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), in individuals with ADHD [

76]. In conclusion, there is evidence to suggest a link between ADHD and autoimmune diseases, possibly mediated by chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation. Further research is needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms and to develop effective treatments for individuals with comorbid ADHD and autoimmune diseases.

4.2.2. Immunity, inflammation, and ADHD: Histamine as a potential integrating factor

At this point, why histamine? First of all, we want to emphasize that, supporting the role that histamine should play in the classic concept of SATFS or in the current concept of ADHD, we do not want to downplay the importance of other pathophysiological mechanisms and neurotransmitters such as dopamine or noradrenaline, which have a fundamental role in the pathophysiology of ADHD. We simply want to emphasize that histamine may be the missing link in the clinical relationships we have already mentioned. Indeed, the search for a common pathophysiology between allergy and ADHD may help us to understand their association. In this respect, we again stress that it is awkward that, given the close relationship between ADHD and atopic disorders, it is surprising that the only work suggesting a mediating role between both conditions is the study mentioned before [

77]. In this section, we will review several lines of evidence suggesting a relationship between the SATFS (ADHD) and histamine.

First item. A little bit of history. The physiopathological foundations of the SATFS (ADHD)

Speer suggested that the underlying mechanism of the SATFS was based on the cholinergic system [

2,

5]. He postulated that a cholinergic/adrenergic activity imbalance in the CNS was the best way to explain the SATFS [

6]. Others, however, rejected this hypothesis of a common etiology mediated by the cholinergic system, and postulated that if there is one, it would not be (only) mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) [

4,

77]. Atopic diseases have traditionally been linked to increased plasma levels of IgE. In 2009, Pelsser and colleagues suggested that the relationship between allergies and ADHD was supported by a hypersensitive mechanism, including both allergic (IgE- or non-IgE-mediated) and non-allergic alternatives [

77]. These authors considered ADHD a hypersensitivity syndrome with(out) allergic basis, in which dopamine, noradrenaline, and histamine would play a common role in the ADHD-asthma duet, causing exaggerated reactions to certain environmental stimuli in both pathologies. This milestone is relevant because it is the first time that histamine is postulated as a neurotransmitter potentially involved in the ADHD-atopia relationship. More recently, Maintz and colleagues proposed that a diminished histamine degradation secondary to reduced DAO activity may be the main reason for non-IgE-mediated food intolerance caused by histamine [

23].

More recent research points to a reciprocal activation: on the one hand, overexposure of the cortex to the high levels of cytokines produced in the allergic reaction and its treatment would cause alterations in brain maturation making it more susceptible to developing ADHD; on the other hand, increased stress in children with ADHD may lead to activation of the immune response by alternative neuroimmune pathways triggering the allergic reaction [

71,

78]. Finally, anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines are related to tryptophan metabolism and dopaminergic pathways. Therefore, there is increasing evidence regarding the inflammatory mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ADHD [

79]. Furthermore, serotonin has been considered a potential common mechanism for both disorders acting as a trigger: high plasma serotonin levels would be associated with asthma attacks, whereas low plasma serotonin levels are associated with impulsive and aggressive behaviors, including suicidal behaviors [

80].

Second item: ADHD and histamine: What is the evidence?

As stated before, histamine is a biogenic amine that acts as a neurotransmitter in the CNS, and is involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes. Histamine is synthesized in the brain by histidine decarboxylase (HDC), and it is known to modulate several neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine and noradrenaline, which are traditionally involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD. Studies suggesting a possible link between histamine and ADHD are emerging, but still indirect.

The following points are supported by data suggesting that histamine and ADHD are closely related:

1) Histamine levels [

36,

81], serum DAO levels [

82], and histamine-specific SNPs variants [

37] are associated with the development of cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders, including ADHD.

2) Two frequently used drugs for treating ADHD (methylphenidate and atomoxetine) increase histamine availability in the prefrontal cortex [

83,

84]. Thus, the therapeutic effects of ADHD medications may partly be due to increasing histamine release, in addition to the well-known increasing effect of dopamine and noradrenaline in ADHD [

85,

86].

3) Antihistamine use has been associated with subsequent detection of ADHD [

87,

88,

89]. This increased use of antihistamine drugs may be related to the increased risk of other diseases such as atopy [

89,

90], food allergies [

91], and allergic rhinitis [

92,

93] in people with ADHD.

4) Moreover, there is increasing evidence concerning the potential use of drugs acting at the histaminergic system. In 1985, a case study reported that an anti-histamine, anti-motion sickness drug might exert some improvement in ADHD [

94]. While the precise mechanisms underlying the relationship between histamine and ADHD are still unclear, several preclinical and clinical studies have suggested that H3R antagonists, such as pitolisant, may be effective in treating ADHD symptoms. These drugs increase histamine release and have been shown to improve cognitive function and reduce hyperactivity in individuals with ADHD [

95,

96]. However, some studies using anti-H3R drugs for the treatment of ADHD have yielded negative results [

97,

98].

5) Given the central role of histamine in allergic diseases, and the well-known deleterious effect of traditional anti-histamines, capable of crossing the BBB, on attention and concentration, one might expect that the role of histamine on ADHD has extensively been explored, but this is not the case.

Overall, the relationship between histamine and ADHD is complex and multifaceted, and further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms underlying this connection. Nevertheless, these preliminary findings highlight the potential importance of histamine-signaling in the pathophysiology of ADHD and suggest that histamine-based therapeutics may represent a promising avenue for the treatment of this disorder.

Third item. Antihistamines and CNS side effects.

One of the most relevant lines of evidence comes from the deleterious effects produced by some antihistaminergic drugs. Traditionally, first-generation antihistamines (i.e., diphenhydramine) were characterized by readily crossing the BBB, thus leading to significant CNS side effects such as altered mood, reduced wakefulness, drowsiness, and impaired psychomotor and cognitive performance (i.e., vigilance, divided attention, and working memory) even in the absence of self-reported sleepiness [

99].

Fourth item. A parallelism between SATFS (ADHD) constitutional conditions and HIT.

Another line of evidence comes from the evidence that SATFS constitutional symptoms affect most of the systems that are also affected in HIT: 1) the respiratory system (asthma, nasal allergy); 2) the digestive system (gastrointestinal allergy); 3) the skin (eczema, edema); 4) the CNS (headache, with a clinical description that recalls migraine, characteristically unilateral and frontal, typically associated with HIT); and 5) the urinary system (enuresis). See

Table 3.

Furthermore, DAO activity has been linked to migraine [

29,

100], celiac disease, and gluten intolerance [

27]. Likewise, HIT, a non-immune reaction caused by histamine accumulation, is characterized by diverse skin, respiratory and gastrointestinal pseudoallergic symptoms [

101]. Interestingly, most of the disorders related to either DAO activity and/or HIT, are also frequently reported in people diagnosed with ADHD, and as noted above, affect the same body systems. For instance, there is an increased risk of migraine among ADHD patients, either children [

102] or adults [

103]. Moreover, there is increasing evidence about the relationship between ADHD, and celiac disease [

104], and other food allergies that might be the counterpart of what Speer coined as “gastrointestinal allergy”. Tryphonas and Trites (1979) reported that 47% of the 90 hyperactive children referred were allergic to at least one food [

105]. Finally, the potential role of food additives in ADHD has long been debated, and the evidence, although still not definite, appears to suggest such a relationship [

106,

107]. This is interesting because the exacerbation of ADHD symptoms in children by food additives seems to be related to a genetic polymorphism affecting histamine [

108]. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial, three food additives were administered to a general community sample of 3-year-old children, and 8/9-year-old children. The adverse effect of food additives on ADHD symptoms was moderated by histamine degradation gene polymorphisms: the two HNMT polymorphisms (T939C and HNMT Thr105Ile) in 3- and 8/9-year-old children; and one DAT1 polymorphism in 8/9-year-old children only.

Fifth item. Histamine and immunity in ADHD and related disorders.

The immune system plays a critical role in the body's response to infection, injury, and disease. One important aspect of this response is inflammation, which is a complex biological process that involves the activation of immune cells and the release of various inflammatory molecules. Inflammation is essential for the clearance of pathogens and the repair of damaged tissue, but it can also be harmful if it becomes chronic or dysregulated [

109].

Several studies have shown that the immune system and inflammation are closely linked. For example, immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells can release cytokines and chemokines that initiate and amplify the inflammatory response.

In turn, inflammatory molecules can stimulate the recruitment and activation of immune cells, leading to a feedback loop that can perpetuate inflammation. Moreover, chronic inflammation has been associated with a wide range of diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune disorders. In these conditions, the immune system may become overactive and mistakenly target healthy tissue, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Overall, the relationship between immunity and inflammation is complex and multifaceted, and further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms underlying this connection. However, it is clear that a well-functioning immune system and balanced inflammatory response are essential for maintaining health and preventing disease [

110].

Histamine is a well-known mediator of allergic responses and inflammation, but it is also involved in the regulation of immune responses. Indeed, histamine can regulate the production and release of cytokines, which are important mediators of immune response. For example, histamine can increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in various immune cells [

111]. Cytokines, on the other hand, can also regulate the production and release of histamine in various tissues by mast cells [

112]. In summary, histamine and cytokines are important mediators of immune response, which plays a role in many physiological processes. The interaction between these two molecules is complex and involves multiple signaling pathways. Further research is needed to fully understand the relationship between histamine and cytokines and its implications for health and disease.

All that said about immunity and inflammation, an altered histaminergic system may mediate some of the clinical manifestations of both allergy and ADHD. Indeed, one study reported an association between left-handedness and immune disease, migraine, and developmental learning disorder [

113]. This study is traditionally reported as the Geschwind-Behan hypothesis. Interestingly, in 1971, Speer published a lesser-known paper relating allergy and migraine [

114]. Regarding the relationship between left-handedness and immune disease, and particularly allergy, results are quite convincing as most literature has found a clear-cut, positive association, thus lending support to Geshwind's hypothesis of a relationship between cerebral dominance and a characteristic immunologic set [

115,

116]. This relationship appears to be particularly strong among asthma, eczema, urticaria, and ulcerative colitis [

116,

117,

118,

119]. All of these diseases fall under the concept of Speer syndrome. In the most relevant study to date, including information from 134,317 female and 120,783 male participants, the authors reported that individuals indicating "either" hand for writing preference “had significantly lower spatial performance (mental rotation task) and significantly higher prevalence of hyperactivity, dyslexia, asthma than individuals who had clear left- or right-hand preferences” [

120].

Regarding the relationship between left-handedness and migraine, the evidence is more controversial [

121,

122,

123]. In any case, it is interesting to stress the results of a study in which the authors reporting a close relationship between the number of anomalous brain conditions or phenomena (including mixed- or left-handedness, learning and speech disorders, enuresis after age 5), and migraine [

124].

Moreover, the evidence regarding an association between left-handedness and both dyslexia and ADHD is compelling [

125,

126]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed the relationship between left-handedness and ADHD [

127]. Furthermore, left-handedness has also been related to different typical ADHD comorbidities such as developmental coordination disorder [

128], or consequences such as traumatic dental injuries [

129], head injuries [

130], and some symptoms that were included in the Speer syndrome, such as enuresis [

131,

132]. Furthermore, neonatal habenula lesion-induced ADHD-like syndrome in juvenile rats could be normalized by the histamine H3 receptor antagonists [

96].

6. The interaction between histaminergic and acetylcholine systems.

Both acetylcholine and histaminergic systems are important neurotransmitters that play a role in many physiological processes in the body, and the interaction between them is complex and involves multiple receptors and signaling pathways. Histamine mediates allergic responses and inflammation, but it is also involved in the regulation of neurotransmission. Histamine neurons project to many brain regions and can modulate the release of other neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine [

12]. Indeed, histaminergic neurons can influence the activity of cholinergic neurons, as they increase the release of acetylcholine by dopamine-independent, and dopamine-dependent - the inhibition of dopamine release decreases GABAergic transmission - mechanisms [

133]. Furthermore, lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, an amphetamine approved for the treatment of ADHD, markedly increased acetylcholine efflux in the pre-frontal cortex, and histamine efflux in both the pre-frontal cortex and hippocampus, thus suggesting that both acetylcholine and histamine might be involved in the therapeutic effects of lysdexamphetamine in patients with ADHD [

134].

Acetylcholine, on the other hand, is an important neurotransmitter that plays a crucial role in the regulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. It is involved in many physiological processes such as muscle contraction, cognitive function, and regulation of the immune system. Acetylcholine also regulates histamine release in various tissues, including the brain. Indeed, the nervous system regulates the inflammatory response in real time thanks to acetylcholine, in the same vein as it controls heart rate [

135].

Studies have shown that histamine and acetylcholine interact in many physiological processes, including sleep, cognitive function, and inflammation. For example, histamine and acetylcholine act together to regulate the sleep-wake cycle, with histamine promoting wakefulness and acetylcholine promoting REM sleep [

35]. In summary, histamine and acetylcholine are important neurotransmitters that play a role in many physiological processes. The interaction between these two molecules is complex and involves multiple receptors and signaling pathways. Further research is needed to fully understand the relationship between histamine and acetylcholine and its implications for health and disease.

7. Final words.

The SATF syndrome is a clinical entity characterized by chronic fatigue, muscle tension, headache, cognitive impairment, and allergy-like symptoms that are triggered or worsened by exposure to certain foods or environmental factors. The pathogenesis of the SATF syndrome is thought to involve an abnormal immune response to allergens, which leads to the release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine, and cytokines.

We think that histamine, and not acetylcholine is the most plausible neurotransmitter involved in the pathogenesis of SATFS. In other words, histamine probably plays a very relevant role in the etiology of ADHD and related somatic conditions, particularly those of an allergic-immune basis. In any case, all mentioned molecules (IgE, histamine, acetylcholine, cytokines, dopamine, and noradrenaline), which are important molecules involved in the immune system and the nervous system, are probably involved in the etiopathogenesis of ADHD and related somatic conditions. IgE is an immunoglobulin that plays a crucial role in the immune response to allergens. When IgE binds to an allergen, it triggers the release of histamine and other mediators from mast cells, leading to an allergic response [

136]. Histamine is released from mast cells and basophils in response to various stimuli, including allergens, pathogens, and stress. Histamine is involved in local immune responses, inflammation, smooth muscle contraction, vasodilation, and is also an MAO substrate and acts as a neurotransmitter [

12,

28]. Acetylcholine plays a crucial role in the regulation of the parasympathetic nervous system, and is involved in muscle contraction, cognitive function, and the regulation of the immune system [

135]. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a crucial role in the regulation of the reward system, motivation, movement, and the immune system [

137]. Finally, norepinephrine is involved in the regulation of the sympathetic nervous system, and plays a crucial role in the regulation of the "fight or flight" response, and the regulation of the immune system [

138].

5. Conclusions and future directions

The SATF syndrome included a particular behavior reminiscent of the current concept of ADHD, and a constellation of physical symptoms (“constitutional allergic traits”) that are very similar to those of HIT and which included hyperhidrosis, headache, edema, lacrimation, salivation, and increased bladder tone (i.e., enuresis). We suggested that the most plausible molecule behind the physiopathology is histamine.

People affected by ADHD usually have a prefrontal cortex dysfunction, a cortical region regulated by subcortical systems including dopaminergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic pathways [

139]. Most of the pathophysiology and etiology of ADHD is based in the catecholamine system (dopamine and noradrenaline). As a matter of fact, all major drugs (i.e., atomoxetine, lisdexamfetamine, methylphenidate) treating ADHD increase either dopamine or noradrenaline, or both, in the synapsis cleft. Interestingly, both drugs also increase histamine in the brain.

Furthermore, ADHD is a major burden where psychiatric and somatic comorbidity frequently dominate the clinical picture [

140]. Further research is needed to fully understand the relationship between ADHD and related somatic conditions, and the underlying mechanisms involved. Nevertheless, immune dysregulation and histamine intolerance, probably mediated by DAO deficiency, may be important factors in the pathophysiology of ADHD and related somatic conditions. In any case, given the increasing evidence linking diamine oxidase enzyme (DAO), the major catabolizing enzyme of histamine, and allergy, it is surprising to find that studies exploring a relationship between either histamine or DAO, and ADHD are lacking.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing—and funding acquisition, H.B.F.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Lorraine Maw for English proof correction. He also thanks Dr Healthcare, and particularly Maria Tintore and Carlos de Lecea, by providing different literature about DAO deficiency and HIT.

Conflicts of Interest

In the last 24 months, H.B.F. has received lecture fees from Takeda, BIAL, laboratorios Rubio, and laboratorios Rovi. He has also been granted with three prizes regarding the development of a serious videogame for treating ADHD (The secret trail of Moon): the Shibuya Prize by Takeda; the first prize of the college of psychologists of Madrid; and a prize to the best innovative health initiative within the healthstart prize (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o_j6WBKIpF0&list=PLFM_B3KwjcXObcNBpbL3VBnrbcRTJmOt4&index=5). He is Principal Investigator (PI) of an iPFIS research contract (

www.isciii.es, accessed on 12 August 2022; IFI16/00039), co-PI of a MINECO research grant (RTI2018-101857-B-I00), and PI of a research of the SINCRONIA project, funded by the Start-up Bitsphi; recipient of (1) a FIPSE Grant and (2) an IDIPHIPSA intensification grant; involved in two clinical trials (MENSIA KOALA, NEWROFEED Study; ESKETSUI2002); Co-Founder of Haglaia Solutions. He is also an employee and member of the advisory board of ITA Salud Mental (KORIAN).

References

- G. Polanczyk et al., "The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents," in Am J Psychiatry, vol. 164, no. 6). United StatesEngland: 2015 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health., 2007, pp. 942-8.

- Speer, F. The Allergic Tension-Fatigue Syndrome in Children. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1958, 12, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, R.; Stanton, W.R.; Sears, M.R. Allergic disorders and attention deficit disorder in children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1993, 21, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Gaitens, B. J. Kaplan, and B. Freigang, "Absence of an association between IgE-mediated atopic responsiveness and ADHD symptomatology," (in eng), J Child Psychol Psychiatry, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 427-31, Mar 1998.

- Speer, F. The Allergic Tension-Fatigue Syndrome. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 1954, 1, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, P. Attention deficit disorder and allergy: A neurochemical model of the relation between the illnesses. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 106, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, N.; Beyreiss, J.; Schlenzka, K.; Beyer, H. Coincidence of attention deficit disorder and atopic disorders in children: Empirical findings and hypothetical background. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1991, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comas-Basté, O.; Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.; Vidal-Carou, M.d.C. Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Novak, N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maintz, L.; Yu, C.-F.; Rodríguez, E.; Baurecht, H.; Bieber, T.; Illig, T.; Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the diamine oxidase gene with diamine oxidase serum activities. Allergy 2011, 66, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanaka, J.; Kitanaka, N.; Tsujimura, T.; Terada, N.; Takemura, M. Expression of diamine oxidase (histaminase) in guinea-pig tissues. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 437, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H.L.; Sergeeva, O.A.; Selbach, O. Histamine in the Nervous System. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1183–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Panula, "Histamine receptors, agonists, and antagonists in health and disease," (in eng), Handb Clin Neurol, vol. 180, pp. 377-387, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Thangam, E.B.; Jemima, E.A.; Singh, H.; Baig, M.S.; Khan, M.; Mathias, C.B.; Church, M.K.; Saluja, R. The Role of Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Mast Cell-Mediated Allergy and Inflammation: The Hunt for New Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, X.; Saito, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, P.; et al. The allergy mediator histamine confers resistance to immunotherapy in cancer patients via activation of the macrophage histamine receptor H1. Cancer Cell 2021, 40, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C. Histamine - a major role in allergy? Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Chan, E.W.; Man, K.K.C.; Lau, W.C.Y.; Leung, W.K.; Ho, L.M.; Wong, I.C.K. Dosage Effects of Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonist on the Primary Prophylaxis of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID)-Associated Peptic Ulcers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Drug Saf. 2014, 37, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, R.; Tamaki, S.; Kawakami, F.; Maekawa, T.; Ichikawa, T. Histamine H2-Receptor Antagonists Improve Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Intestinal Dysbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alstadhaug, K.B. Histamine in Migraine and Brain. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2014, 54, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Silberstein, S.D. Histamine and Migraine. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2017, 58, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehane, L.; Olley, J. Histamine fish poisoning revisited. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 58, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, J.M. Scombroid poisoning: A review. Toxicon 2010, 56, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Benfadal, S.; Allam, J.-P.; Hagemann, T.; Fimmers, R.; Novak, N. Evidence for a reduced histamine degradation capacity in a subgroup of patients with atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Yáñez, M.; Díaz-Díaz, A.; Calvo-Henríquez, C.; Lechien, J.R.; Vaira, L.A.; Figueroa, A. Diamine Oxidase Activity Deficit and Idiopathic Rhinitis: A New Subgroup of Non-Allergic Rhinitis? Life 2023, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkar, N.M.; Rupwate, R.U.; Desai, N.K.; Kamat, S.R. Comparative study of platelet histamine and serotonin with their corresponding plasma oxidases in asthmatics with normals. . 1999, 47, 878–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Meier-Allard, N.; Michaelis, S.; Lackner, S.; Enko, D.; Mangge, H.; Holasek, S.J. Serum Diamine Oxidase Values, Indicating Histamine Intolerance, Influence Lactose Tolerance Breath Test Results. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griauzdaitė, K.; Maselis, K.; Žvirblienė, A.; Vaitkus, A.; Jančiauskas, D.; Banaitytė-Baleišienė, I.; Kupčinskas, L.; Rastenytė, D. Associations between migraine, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and activity of diamine oxidase. Med Hypotheses 2020, 142, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatarinova, T.V.; Deiss, T.; Franckle, L.; Beaven, S.; Davis, J. The Impact of MNRI Therapy on the Levels of Neurotransmitters Associated with Inflammatory Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Casas, J.; Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Lorente-Gascón, M.; Duelo, A.; Vidal-Carou, M.C.; Soler-Singla, L. Low serum diamine oxidase (DAO) activity levels in patients with migraine. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 74, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okutan, G.; Casares, E.R.; Alcalde, T.P.; Niño, G.M.S.; Penadés, B.F.; Lora, A.T.; Estríngana, L.T.; Oliva, S.L.; Martín, I.S.M. Prevalence of Genetic Diamine Oxidase (DAO) Deficiency in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia in Spain. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, W.; Plata-Nazar, K.; Sznurkowska, K.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Histamine Intolerance in Children: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantke, F.; Götz, M.; Jarisch, R. Histamine-free diet: treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and supporting treatment for chronical headaches. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1993, 23, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panula, P.; Nuutinen, S. The histaminergic network in the brain: basic organization and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.C.; Arrang, J.M.; Garbarg, M.; Pollard, H.; Ruat, M.; Gemba, C.; Nakayama, K.; Nakamura, S.; Mochizuki, A.; Inoue, M.; et al. Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol. Rev. 1991, 71, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.E.; Stevens, D.R.; Haas, H.L. The physiology of brain histamine. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001, 63, 637–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z. The Histaminergic System in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Nakamura, T.; Yanai, K. Histamine N-Methyltransferase in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhan, A.D.; Gani, M.A.; Budiatin, A.S.; Siswodihardjo, S.; Khotib, J. Molecular docking studies of Nigella sativa L and Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb secondary metabolites against histamine N-methyltransferase with their ADMET prediction. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 32, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; A Waschbusch, D. Relationship between sluggish cognitive tempo and sleep, psychological, somatic, and cognitive problems and impairment in children with autism and children with ADHD. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 26, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K.W.; Reichl, S.; Lange, K.M.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Adhd Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2010, 2, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, M.; Hashemi, P.; Reagan, L.P. Integrating the monoamine and cytokine hypotheses of depression: Is histamine the missing link? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 55, 2895–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegvik, T.-A.; Waløen, K.; Pandey, S.K.; Faraone, S.V.; Haavik, J.; Zayats, T. Druggable genome in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its co-morbid conditions. New avenues for treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 26, 4004–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Argibay, M.; du Rietz, E.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J.; Haan, E.; Lehto, K.; Bergen, S.E.; Lichtenstein, P.; Larsson, H.; Brikell, I. The role of ADHD genetic risk in mid-to-late life somatic health conditions. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rietz, E.; Brikell, I.; Butwicka, A.; Leone, M.; Chang, Z.; Cortese, S.; D'Onofrio, B.M.; A Hartman, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Faraone, S.V.; et al. Mapping phenotypic and aetiological associations between ADHD and physical conditions in adulthood in Sweden: a genetically informed register study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.G.; Weiss, M.D.; Hudec, K.L.; Gibbins, C. The Functional Impact of Sleep Disorders in Children With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2017, 24, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J.; Faraone, S.V. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 2005, 366, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilens, T.E.; Martelon, M.; Joshi, G.; Bateman, C.; Fried, R.; Petty, C.; Biederman, J. Does ADHD Predict Substance-Use Disorders? A 10-Year Follow-up Study of Young Adults With ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Moreira-Maia, C.R.; Fleur, D.S.; Morcillo-Peñalver, C.; Rohde, L.A.; Faraone, S.V. Association Between ADHD and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaburda, A.M. The testosterone hypothesis: Assessment since Geschwind and Behan, 1982. Ann. Dyslexia 1990, 40, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, N.; Galaburda, A.M. Cerebral Lateralization. Arch. Neurol. 1985, 42, 428–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, N.; Galaburda, A.M. Cerebral Lateralization. Arch. Neurol. 1985, 42, 521–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Romanos, M.; Schmitt, N.M.; Meurer, M.; Kirch, W. Atopic Eczema and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in a Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. JAMA 2009, 301, 724–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, M.; Gerlach, M.; Warnke, A.; Schmitt, J. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and atopic eczema modified by sleep disturbance in a large population-based sample. J. Epidemiology Community Heal. 2009, 64, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camfferman, D.; Kennedy, J.D.; Gold, M.; Simpson, C.; Lushington, K. Sleep and neurocognitive functioning in children with eczema. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 89, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.-D.; Chang, S.-N.; Mou, C.-H.; Sung, F.-C.; Lue, K.-H. Association between atopic diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood: a population-based case-control study. Ann. Epidemiology 2013, 23, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghmaie, P.; Koudelka, C.W.; Simpson, E.L. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 131, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuneit, J.; Braig, S.; Brandt, S.; Wabitsch, M.; Florath, I.; Brenner, H.; Rothenbacher, D. Infant atopic eczema and subsequent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - A prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2013, 25, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-H.; Su, T.-P.; Chen, Y.-S.; Hsu, J.-W.; Huang, K.-L.; Chang, W.-H.; Chen, T.-J.; Pan, T.-L.; Bai, Y.-M. Is atopy in early childhood a risk factor for ADHD and ASD? A longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 77, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Ha, M.; Yoo, S.J.; Paik, K.C.; Lim, J.-H.; Sakong, J.; Lee, C.-G.; Kang, D.-M.; Hong, S.J.; et al. The associations between ADHD and asthma in Korean children. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 70–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-J.; Chou, P.-H.; Cheng, C.; Lin, C.-H.; Lan, T.-H.; Lin, C.-C. Asthma in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide population-based study. . 2014, 26, 254–60. [Google Scholar]

- Suwan, P.; Akaramethathip, D.; Noipayak, P. Association between allergic sensitization and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). . 2011, 29, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel, H.; Sogut, A.; Yilmaz, O. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Symptoms in Children with Asthma. J. Asthma 2008, 45, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, J.A.; Gurka, M.J. Developmental and Behavioral Comorbidities of Asthma in Children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007, 28, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, N.; Larsson, H.; Lundholm, C.; Almqvist, C. Association between childhood asthma and ADHD symptoms in adolescence - a prospective population-based twin study. Allergy 2011, 66, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hak, E.; de Vries, T.W.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Jick, S.S. Association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with atopic diseases and skin infections? A matched case-control study using the General Practice Research Database. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2013, 111, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, K.; Lundholm, C.; Anckarsäter, H.; Larsson, H.; Almqvist, C. Impact of asthma medication and familial factors on the association between childhood asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a combined twin- and register-based study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Milberger, S.; Faraone, S.V.; Guite, J.; Warburton, R. Associations between Childhood Asthma and ADHD: Issues of Psychiatric Comorbidity and Familiality. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1994, 33, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerness, P.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Faraone, S.V.; Gallo, L.; Murphy, H.; Biederman, J. Reexamining the Familial Association Between Asthma and ADHD in Girls. J. Atten. Disord. 2005, 8, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saricoban, H.E.; Ozen, A.; Harmanci, K.; Razi, C.; Zahmacioglu, O.; Cengizlier, M.R. Common behavioral problems among children wıth asthma: Is there a role of asthma treatment? Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2011, 106, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.-T.; Lee, W.-T.; Liang, J.-S.; Lin, Y.-J.; Fu, W.-M.; Chen, C.-C. Hyperactivity and Impulsivity in Children with Untreated Allergic Rhinitis: Corroborated by Rating Scale and Continuous Performance Test. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2014, 55, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Loh, E.-W.; Chan, C.-H.; Lan, T.-H. Prevalence of allergic rhinitis in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 22, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, C.; Koyama, M.; Ota, E.; Swa, T.; Mlunde, L.B.; Amiya, R.M.; Tachibana, Y.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Mori, R. Allergic diseases in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schans, J.; Çiçek, R.; de Vries, T.W.; Hak, E.; Hoekstra, P.J. Association of atopic diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-L.; Wang, L.-J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-J. Two meta-analyses of the association between atopic diseases and core symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K. Autoimmunity as a Risk Factor for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corominas-Roso, M.; Armario, A.; Palomar, G.; Corrales, M.; Carrasco, J.; Richarte, V.; Ferrer, R.; Casas, M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J. IL-6 and TNF-α in unmedicated adults with ADHD: Relationship to cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 79, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelsser, L.M.J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Savelkoul, H.F.J. ADHD as a (non) allergic hypersensitivity disorder: A hypothesis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 20, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; Schmitt, J.; Plessow, F.; Romanos, M.; Weidinger, S.; Roessner, V. Psychoendocrine and psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms in the comorbidity of atopic eczema and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, D. GABA receptors in brain development, function, and injury. Metab. Brain Dis. 2015, 30, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. Asthma medication may influence the psychological functioning of children. Med Hypotheses 2004, 63, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provensi, G.; Costa, A.; Izquierdo, I.; Blandina, P.; Passani, M.B. Brain histamine modulates recognition memory: possible implications in major cognitive disorders. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 177, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Lane, H.-Y. Blood D-Amino Acid Oxidase Levels Increased With Cognitive Decline Among People With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Two-Year Prospective Study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 25, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-L.; Yang, J.; Lei, G.-F.; Wang, G.-J.; Wang, Y.-W.; Sun, R.-P. Atomoxetine Increases Histamine Release and Improves Learning Deficits in an Animal Model of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 102, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, W.E.; Johnson, D.E.; Schmidt, A.W.; Rollema, H. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine increase histamine release in rat prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 558, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnsten, A.F.T. Fundamentals of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: circuits and pathways. . 2006, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten, A.F.T. Stimulants: Therapeutic Actions in ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2376–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, S.; Tesch, F.; Romanos, M.; Abraham, S.; Schmitt, J. ADHD in school-age children is related to infant exposure to systemic H1-antihistamines. Allergy 2020, 75, 2956–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gober, H.J.; Li, K.H.; Yan, K.; Bailey, A.J.; Carleton, B.C. Hydroxyzine Use in Preschool Children and Its Effect on Neurodevelopment: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 721875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Schmitt et al., "Increased attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms in atopic dermatitis are associated with history of antihistamine use Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder," (in eng), Allergy, vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 615-626, Mar Nov 2018. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; Roessner, V. Is atopic disease a risk factor for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? A systematic review. Allergy 2010, 65, 1506–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.G.; Kosowan, L.; Soller, L.; Chan, E.S.; Nankissoor, N.N.; Phung, R.R.; Abrams, E.M. Prevalence of Physician-Reported Food Allergy in Canadian Children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pr. 2020, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkey, F. Atopic dermatitis: More than just a rash. J. Fam. Pr. 2021, 70, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zheng, X.; Li, Z.; Xiang, H.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H. Risk factors analysis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and allergic rhinitis in children: a cross-sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.E.; Clark, D.L.; Sachs, L.A.; Jakim, S.; Smithies, C. Vestibular and Visual Rotational Stimulation as Treatment for Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1985, 39, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, B.; Saad, A.; Sadeq, A.; Jalal, F.; Stark, H. Histamine H3 receptor as a potential target for cognitive symptoms in neuropsychiatric diseases. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 312, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]