Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is one of the most common types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and comprises the largest portion of aggressive lymphomas. Its treatment is still a challenge to clinicians, and a significant part of patients still falls into the category of unmet medical need and require salvage therapy with autologous transplantation. Adding rituximab to CHOP increased the first-line response rate and cure by about 10-13% in these patients, but about 35-40% relapse or are refractory to this treatment (1). Adding rituximab to CHOP gives slightly better results in the ABC subgroups, but no other therapy has proven beneficial in any subgroup. Salvage treatment of transplant-eligible patients usually is with R-DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara-C, cisplatin) or R-ICE (ifosfamide, etoposide, carboplatin), but recently it has been shown that CAR-T cells (liso-cel and axi-cel) achieve better results in second-line treatment compared to conventional salvage chemotherapy (2, 3). The 3rd line treatment is better with CAR-T cells (tisa-cel, axi-cel, liso-cel) as more patients achieve CR(4–6). The antibody-drug conjugate polatuzumab-vedotin is superior to conventional chemotherapy in second and third-line salvage settings, making this drug an easily accessible therapeutic choice for most clinicians (7). The role of autologous transplantation after successful polatuzumab salvage in selected transplant-eligible patients adds a clear survival benefit. It is still a question whether autologous transplantation should follow successful CAR-T salvage. It has been reported that the more lines of therapy are required before transplantation, the worse the long-term results of this treatment (8). The price and availability of CAR-T therapy make this treatment difficult; thus, a portion of patients still receives conventional chemo-immunotherapy therapy-based salvage in real life, leaving CAR-T therapy as a 3rd or 4th line salvage option for non-responding transplant-eligible patients.

As autologous stem cell transplantation is still the most critical consolidating therapy in r/r DLBCL patients, the authors analyzed their institution's data to see the achievable results and to find any additional factors affecting the results of this treatment modality, making possible ways to improve the outcome.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis of transplanted diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients is reported from a single center at the University of Debrecen. All patients were included who underwent autologous transplantation with the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2021. The patient's clinical data were retrospectively collected from the hospital medical records. The data was also cross-checked with the data reported towards the European Bone Marrow Transplantation Society (EBMT). Survival times were calculated from the time of transplantation. The censoring event in overall survival (OS) was the patients' death, and in event-free survival (EFS), either lymphoma progression or death of any cause. Primary refractory cases were defined as not responding after four cycles of first-line chemotherapy determined by interim 18FDG Positron Emission Tomography CT (PET/CT) or not achieving CR after first-line chemo-immunotherapy based on end-of-treatment evaluation PET/CT or relapsing within 12 months of first-line rituximab-containing therapy. PET/CT was used to confirm the disease status before and after transplantation.

Salvage therapy was administered to patients until PET was negative. PET positivity was considered only an acceptable result before transplantation, where the salvage treatments were not completely effective, and no other salvage therapy was available at the time; thus, the patient achieved the best possible response with the available therapy. In these cases, tumor reduction had to be at least a partial response. However, more than 80% tumor reduction was detected in most of the patients not reaching complete metabolic response (CMR) before transplantation. Complete response (CR) refers to CMR in patients' pretransplant and post-transplant evaluation according to Lugano classification (9). All patients not fulfilling the criteria for CMR are reported as having PR. No stable disease or progressive disease patients were transplanted.

Patient characteristics

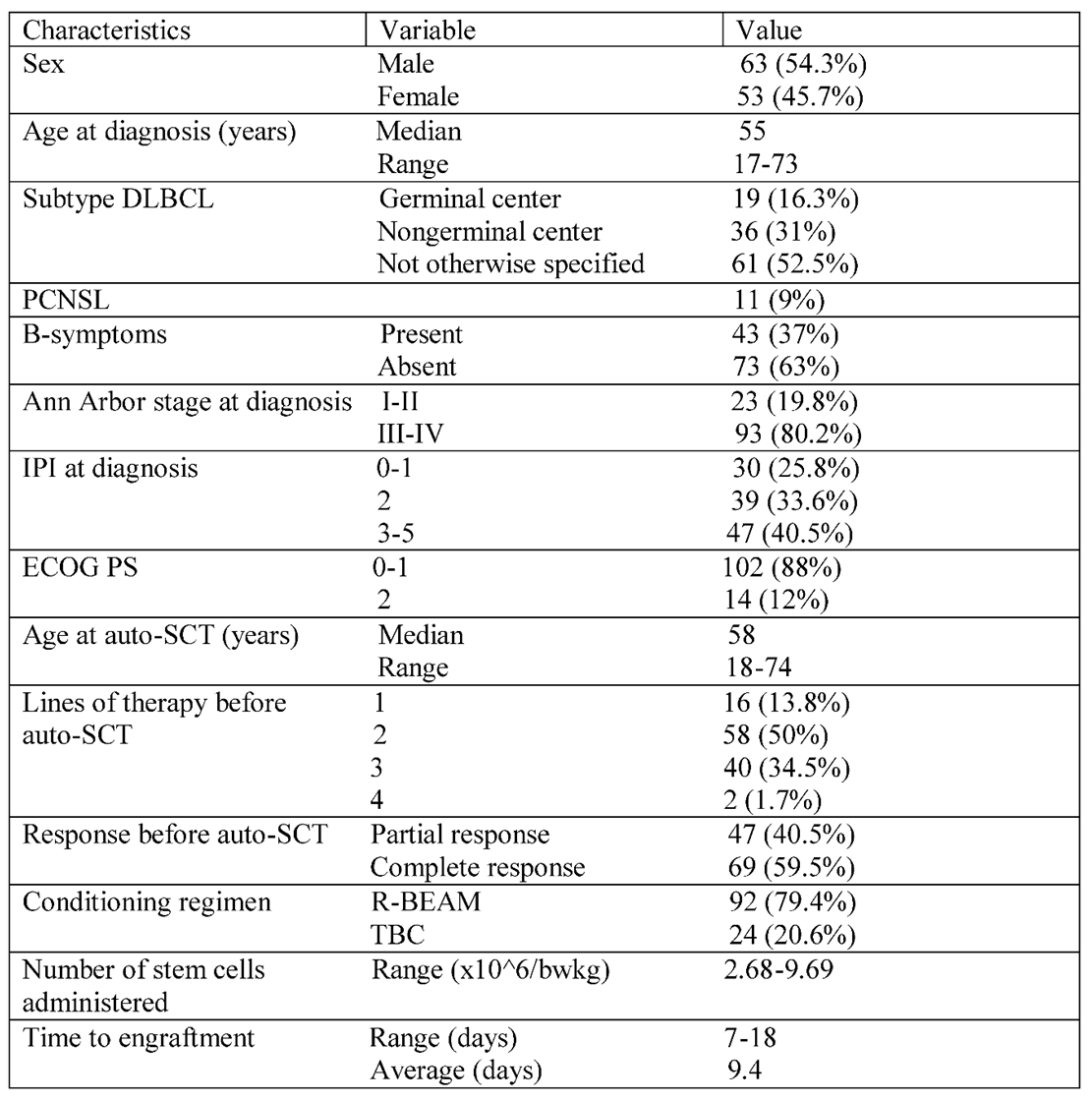

In the defined time interval, 116 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients underwent autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT). All patients transplanted during this period were included. There were 11 primary central nervous lymphoma (CNS lymphoma) and eight systemic plus CNS involvement cases. These all were transplanted as part of the first-line consolidation therapy. Four primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and one very aggressive DLBCL were also transplanted first line. The rest of the patients were relapsed/refractory cases, as 39 primary refractory and 53 relapsed patients were transplanted after responding to salvage treatment. The baseline characteristics of patients at diagnosis are summarized in

Table 1. The median age at initial diagnosis was 58 years (range 18-74), and 63 (54.3%) were male. The clinical characteristics at diagnosis were as follows. Ninety-three patients (80.2%) had advanced-stage disease (Ann Arbor stage III-IV). 102 patients (87.9%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. International prognostic index risk groups were low risk in 30 (25.8%), intermediate in 39 (33.6%), and high risk in 47 (40.5%) of patients. The cell of origin by Hans algorithm was used to define the histological groups of patients, but it was routinely used after 2015. Germinal center lymphoma was diagnosed in 19 cases (16.3%), non-germinal center B-cell-like in 36 cases (31%), and not otherwise specified in 61 (52.5%) patients. Most patients received R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) as first-line treatment. CNS lymphoma cases were treated with high-dose methotrexate-rituximab-vincristine (R-MPV) and were transplanted as part of the first-line treatment. Relapsed/refractory disease was confirmed by

18FDG-PET/CT scan. Rebiopsy was not routinely performed, only in cases where late relapse or unusual localization of the relapse was detected. The most common salvage regimen was R-DHAP (rituximab, cisplatin, dexamethasone, and high-dose cytarabine, n=72), followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide, n=16). Patients received an average of 2.22 cycles of salvage chemotherapy before transplantation. The response was evaluated after two cycles of salvage therapy, and patients who did not respond were switched to different salvage therapy. Forty-two patients received more than one type of salvage chemotherapy. Radiotherapy was used in 2 cases before transplantation and 4 cases early after transplantation as part of consolidation therapy. Most patients (59.5%) achieved complete metabolic remission before transplantation, but the others failed to do so. In their case, auto-HSCT was performed in partial remission. All primary consolidations were done in CR (n=22). The conditioning regimen was R-BEAM (rituximab, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) for DLBCL (n=92) and TBC (thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide) for CNS lymphoma and lymphoma with CNS involvement and selected aggressive cases where CNS propagation risk was high (n=24). According to the guidelines, the target number of infused viable CD34+ stem cells is 5x10

6/kg body weight at our institution.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan-Meier method analyzed and compared unadjusted survival distributions using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Hazard ratios were calculated using the Log-rank test. The effect of variables on outcome was investigated using the ROC analysis to define cutoff points where needed. Cutoff values were always rounded to the nearest non-decimal number, except noted. Two-sided p-values of <0.05 (5%) were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v9.5 and SPSS v 28.0 software. Survival graphs were created using GraphPad Prism v9.5 software.

Results

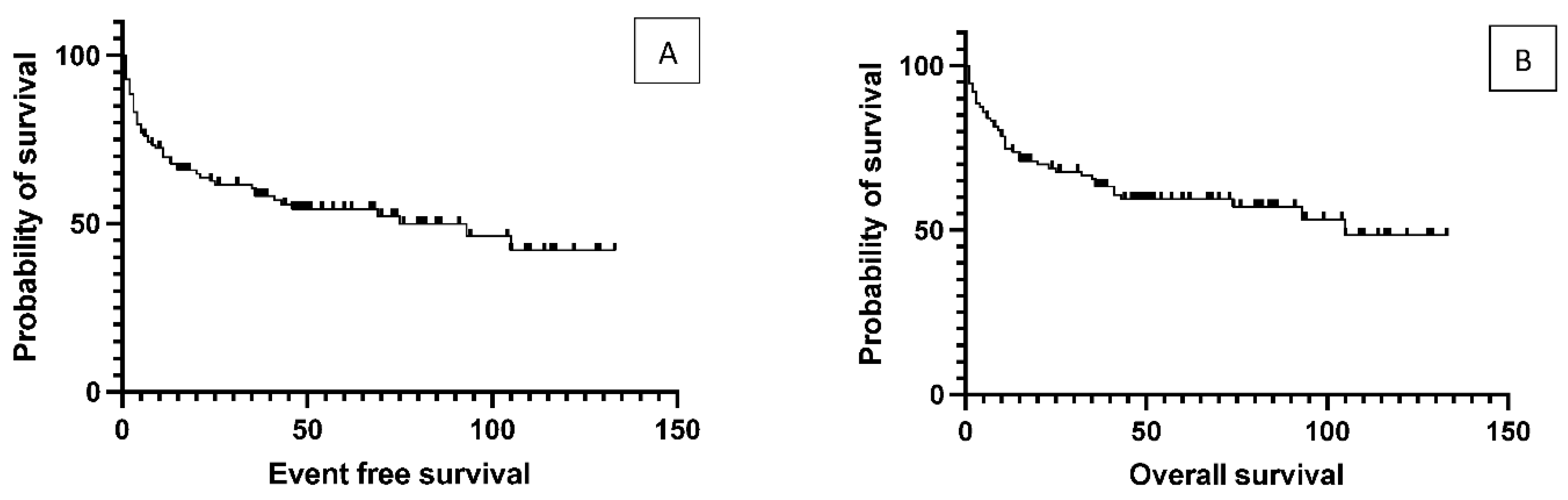

One hundred and sixteen patients with DLBCL are transplanted at the Center. There were 53 relapsed cases where the average time between initial diagnosis to transplantation was 42 months. The median age at the time of transplantation was 58 years (range 18-74). The median duration of follow-up was 46 months (8 to 133). The median OS was 105 months for the total population, while the median EFS was 75 months. (

Figure 1)

The effect of initial prognostic factors established at diagnosis on the outcome of transplantation

The authors analyzed the transplantation outcome data based on prognostic factors that were calculated at the time of DLBCL diagnosis. No significant difference was found in EFS between the low- and intermedier/high-risk groups based on the IPI score (data not presented), as median event-free survival was 93 months in IPI 0-2 group and 43 months in IPI 3-5 group (p= 0.19). Elevated LDH values at diagnosis did not affect the survival results either (data not presented). Median EFS was 93 months in the absence of B-symptoms, while 25 months in the presence of B-symptoms (p = 0.12), but due to data variation was not statistically significant. According to the Hans algorithm, they also found no significant differences in survival between the histological subgroups of CG versus nonCG. The authors compared the groups with primary and secondary CNS involvement because CNS involvement is associated with a worse prognosis. Median event-free survival was 26.5 months in the systemic plus CNS lymphoma group and not reached (p= 0.12) in the primary CNS group. EFS curves reached a stable plateau in the latter cluster at 80.8% (

Figure 2). A detailed summary of hazard ratios associated with different factors is listed in

Table 2.

Effect of pretransplantation prognostic factors on outcome

The authors found no difference in event-free and overall survival between primary refractory and relapsed patients (p= 0.96) and no disparity according to whether the transplant was performed as primary consolidation, or after relapse or primary refractoriness (p= 0.7,

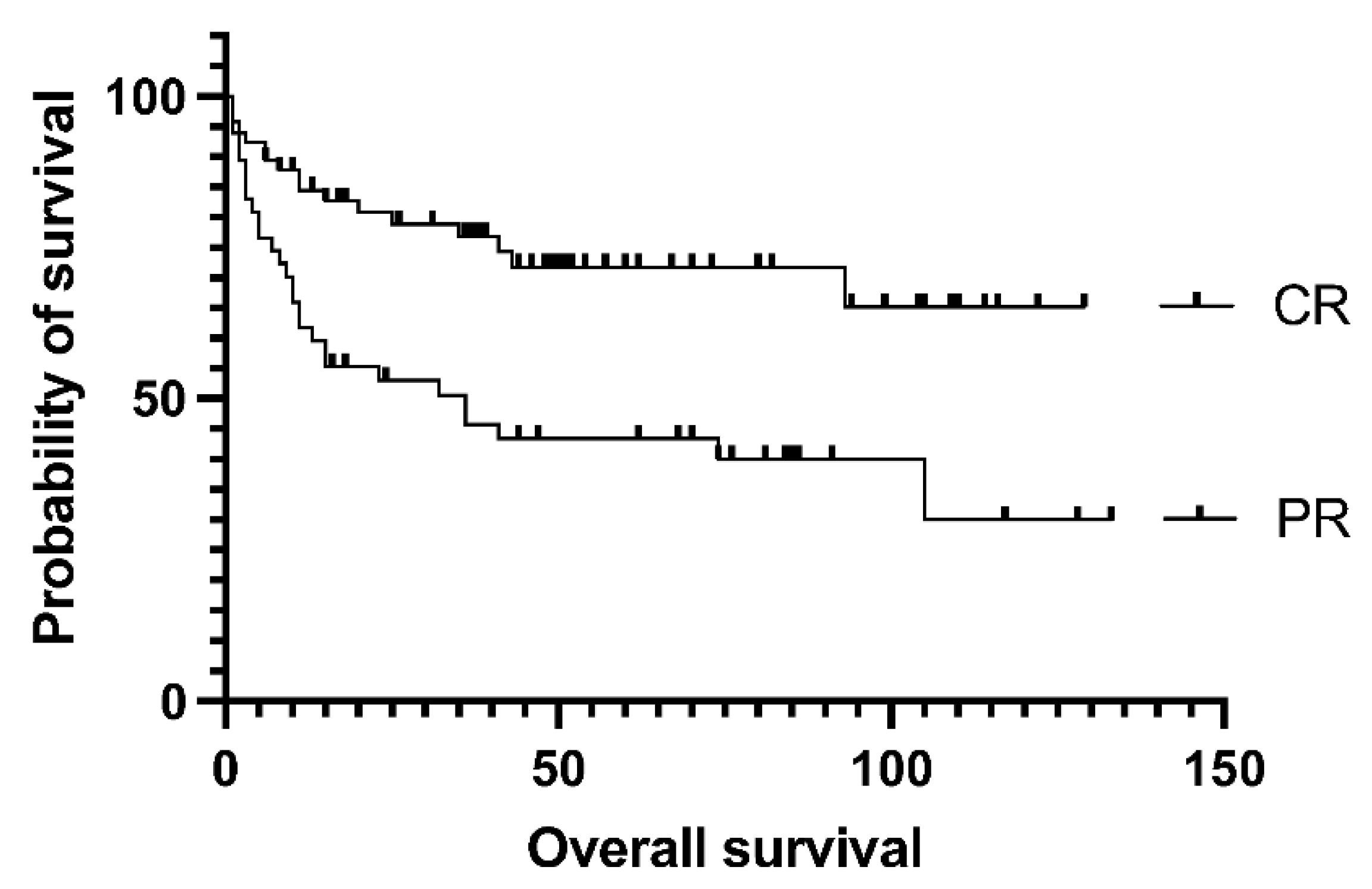

Figure 2.), as the median EFS was not reached vs. 105 vs. 75 months in the groups above. Survival was not affected by the number of lines of prior salvage chemotherapy either; median event-free survival was 93 months in case of 1 type of salvage therapy and 21 months when patients received more than 1 line of salvage (p= 0.13). Patients who achieved a PET-negative complete response before transplantation had significantly better 5-year overall survival than those who achieved only partial remission (62.5% vs. 30%, p= .0009). Median overall survival was 36 months for the PET-positive group and not reached for the PET-negative group (

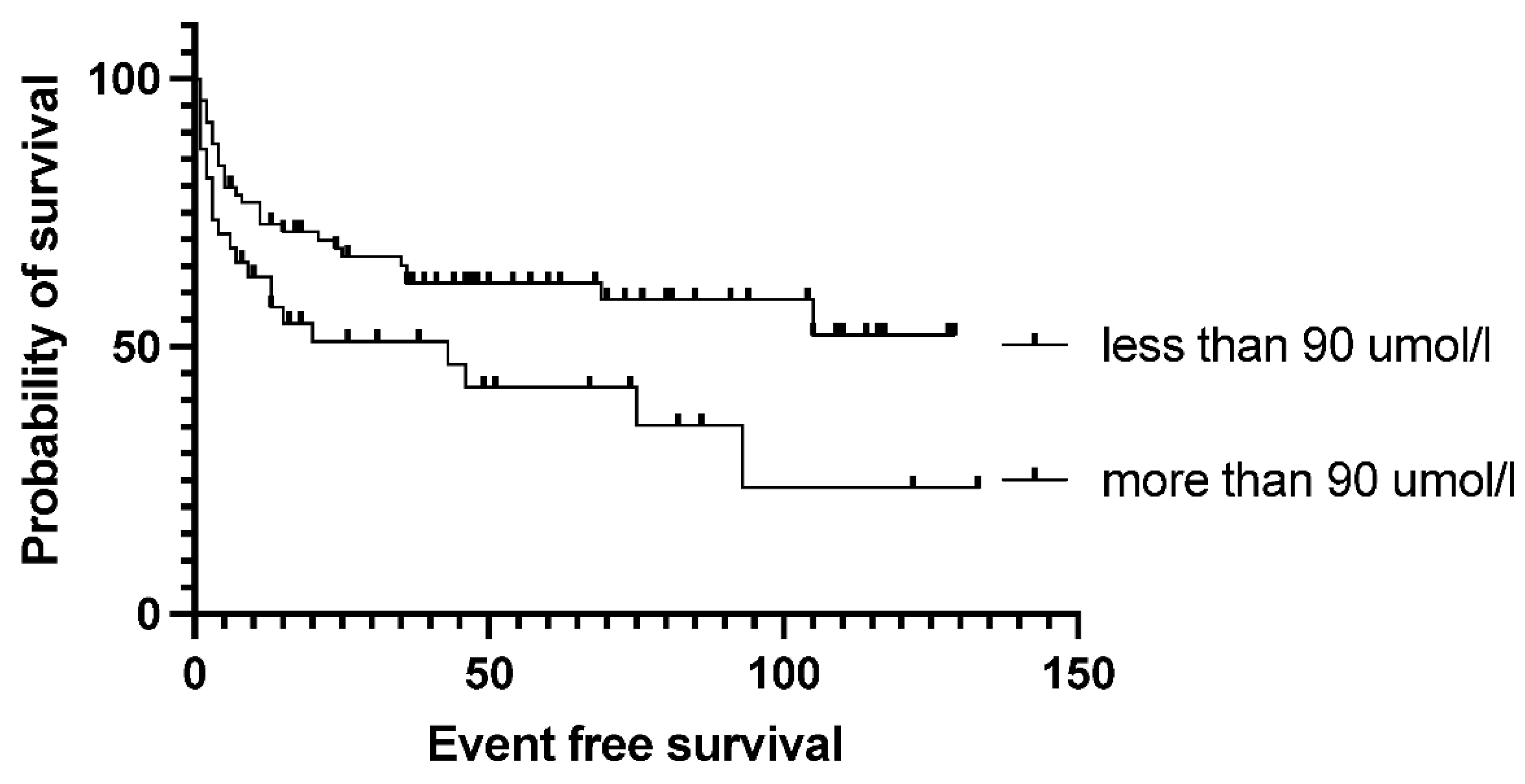

Figure 3). Bone marrow function before transplantation, such as white blood cell count or hemoglobin level, had no significant effect on survival results. Median EFS was 75 months in the normal WBC group and not reached in case of low white blood cell count (p= 0.5). Neither the absolute lymphocyte and monocyte count nor the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio significantly affects survival at this time point (data not shown). Median EFS was 69 months if absolute lymphocyte count was above 1.1 G/L and not reached in a group with lower absolute lymphocyte value (p= .6). Interestingly, renal function did affect the outcome of transplantation, as both higher (>90umol/l) creatinine and higher (>4.5mmol/l) blood urea nitrogen levels are associated with significantly worse survival. Median EFS was 93 vs. 13 months (p= 0.028) in groups with normal and elevated creatinine levels (

Figure 4). The difference was also reflected in overall survival as patients with high urea levels had a median EFS was 46 months in the patients with higher blood urea nitrogen levels, and not reached for the lower urea group (p= 0.018), while the median OS was 74 months vs. not reached in these groups (p= 0.012). The presence of ongoing infection did defer patients from transplant. However, slightly elevated CRP levels without obvious signs of infection were allowed to proceed to transplantation. Elevated C-reactive protein levels measured directly before transplantation also significantly affected the results. CRP level over 6mg/L was associated with significantly shorter EFS and OS. Median EFS was 105 months in the group with normal CRP level and 35 months with elevated CRP level (p= 0.04), while median OS was not reached vs. 36 months (p=0.038). As per local guidelines, the target stem cell number infused was 5 million CD34 per body kg of patients. The actual number of stem cells administered varied between 2.68-9.69x10

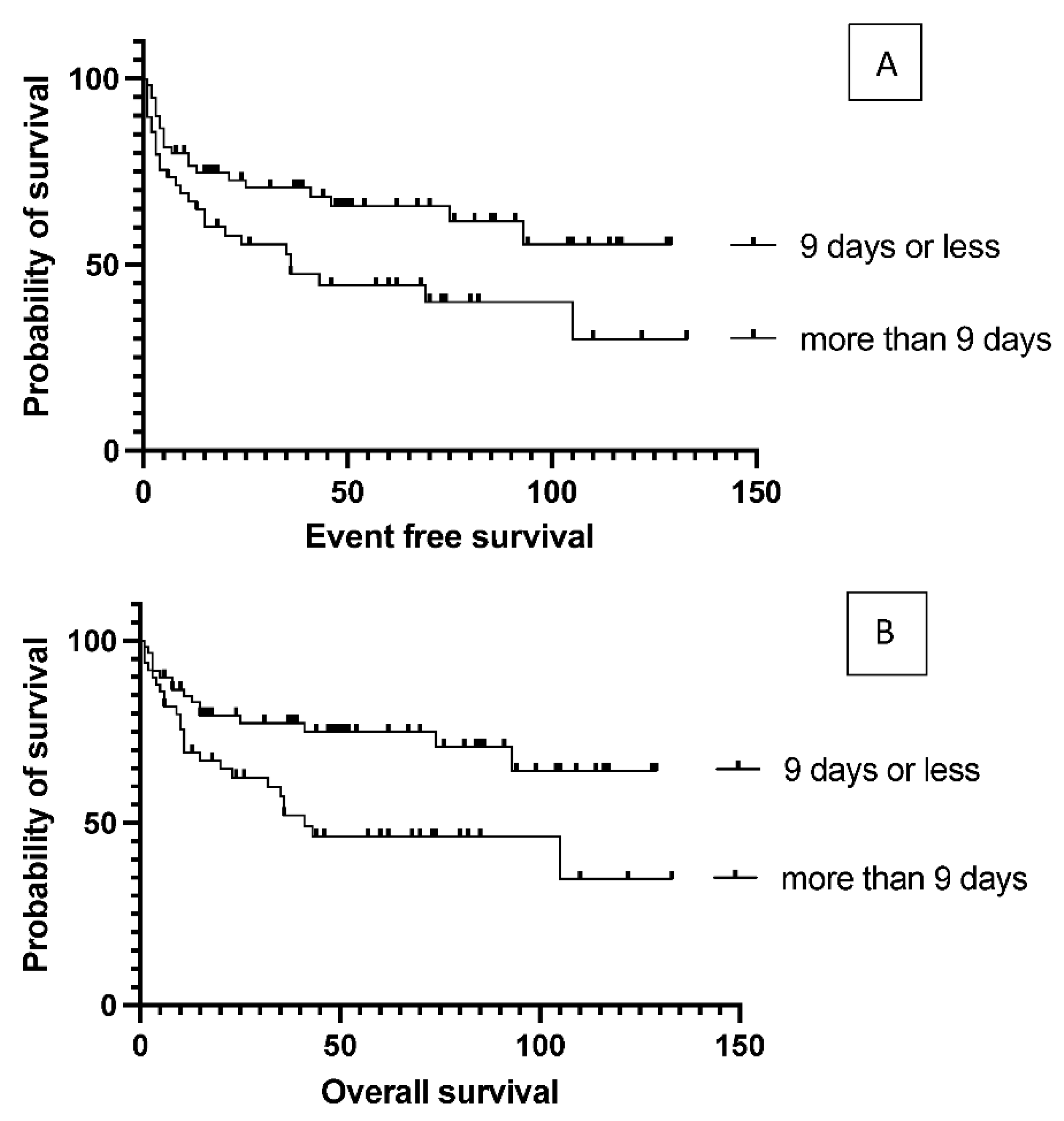

6 per kg body weight (median: 5.84) in the patients. The number of stem cells infused during transplantation did not affect survival (data not shown). Engraftment occurred at a median of 9.4 days (7-18) after stem cell infusion. However, faster engraftment resulted in a better outcome, as median event-free survival was not reached vs. 36 months (p= 0.025), and median overall survival was not reached vs. 41 months (p= 0.01) in case of engraftment within 9 days, than over 9 days (

Figure 5). See

Table 2 for hazard ratios associated with the different factors investigated.

Discussion

Autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation is still an effective therapeutic modality among patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In this single-center analysis, the authors presented survival outcomes, exploring variables associated with survival during this therapeutic modality.

The long-term outcome of the patients reported is similar to what has been published earlier, resulting in more than 50% long-term survival (10). The conditioning consisted of rituximab and BEAM conditioning in the cases reported. Thus the reports reflect the R-BEAM conditioning results. The authors have a good experience with this protocol, with acceptable toxicities. As several prognostic factors at diagnosis have a clear role in the initial prognosis of DLBCL patients, the authors examined whether these factors still hold a role for transplanted patients. The authors found no difference in outcomes after autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory and relapsed DLBCL based on the cell of origin, which is somewhat contrary to what has been published, as the germinal center type was reported to have worse long-term survival (11). However, there is also a similar outcome reported in another publication, where no difference was found according to the cell of origin (12) (13).

The IPI at diagnosis did not differentiate prognostic groups in our cohort, which is also contrary to what has been published earlier, as higher IPI patients had an inferior survival (14). It has been reported that IPI before transplantation may impact outcomes, but it was not evaluated in the cases reported in this paper (15). LDH level and B-symptoms at the diagnosis did not significantly affect the transplantation outcome either. This data corresponds with the previously published data. The reported results in this study support the fact that the clinical behavior of the disease, especially the response to salvage therapy being a strong biological prognostic factor, overwrites all pretreatment prognostic factors. Survival data were not affected by whether the transplant was due to relapse or primary chemo-refractoriness. Only the response to salvage therapy was important, which also determined whether the patient could proceed to transplant. This is somewhat different from the published data, as relapsed patients are reported to have a better prognosis than refractory cases (16). The authors found no difference in whether the patient responded to the first choice of salvage or required additional lines of salvage therapy. No matter how many cycles of therapy were required, if the patient achieved a good response, the transplant was beneficial. This is a very important finding. However, the quality of remission seen on PET/CT before transplantation greatly influenced the results. This has already been published, and the authors' data also support this important finding (17) (18). However, autologous transplantation can still benefit patients responding to salvage therapy but not reaching a complete metabolic response. Whether these patients require additional novel therapy to reach remission or whether the novel treatments can be reserved for cases with relapse after the transplantation is still a question. Bone marrow function before transplantation did not prove to be of decisive importance, as neither the hemoglobin level at the time of transplantation nor the white blood cell count and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio affects survival data. There was a tendency for better outcomes with platelet levels above 100 G/L, but it was only significant for overall survival. The authors found no correlation between the number of stem cells infused and survival. However, the time required for engraftment significantly influences long-term outcomes. This unique data must be further explored, as previous treatments do not influence this. The higher-than-normal CRP value without ongoing infection, as well as the elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, significantly influenced the results highlighting that besides response to therapy being a strong biological prognostic factor, these additional factors characterize the biological background having prognostic influence in these patients.

Several limitations must be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, the retrospective design is subject to inherent selection bias of non-randomized retrospective data, furthermore missing information for some patients who were lost to follow-up, and long study period with different eras of diagnostic criteria, as well as therapy with potentially different management approaches. Our data set had a few missing data, which affected mainly DLBCL subtypes according to Hans algorithm (germinal center B-cell-like, non-germinal center B-cell-like, not otherwise specified). The results of this study are also limited by the relatively small cohort of heterogeneous patients, the heterogeneity of the prior chemotherapy, and distinct causes of transplantation, such as first-line consolidation and refractory and relapsed cases, preventing us from comparing protocol efficacy and drawing definitive conclusions.

In conclusion, consolidative ASCT can be considered an effective and reasonable treatment option for eligible chemosensitive patients in DLBCL. With the availability of novel treatment options such as CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies, further studies are required to understand better how to sequence these treatment modalities (19). The authors' findings support other studies reporting that complete metabolic remission before autologous transplantation is associated with much better overall survival. Prognostic markers existing at the diagnosis lose their significance by the time of transplantation.

References

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235-242. [CrossRef]

- Hagberg H, Gisselbrecht C, CORAL SG. Randomised phase III study of R-ICE versus R-DHAP in relapsed patients with CD20 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) followed by high-dose therapy and a second randomisation to maintenance treatment with rituximab or not: an update of the CORAL study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17 Suppl 4:iv31-2. [CrossRef]

- Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45-56. [CrossRef]

- Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839-852. [CrossRef]

- Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:31-42. [CrossRef]

- Morschhauser F, Flinn IW, Advani R et al. Polatuzumab vedotin or pinatuzumab vedotin plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results from a phase 2 randomised study (ROMULUS). Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e254-e265. [CrossRef]

- Shargian L, Amit O, Bernstine H et al. The role of additional chemotherapy prior to autologous HCT in patients with relapse/refractory DLBCL in partial remission-A retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Haematol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059-3068. [CrossRef]

- Mounier N, Canals C, Gisselbrecht C et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in first relapse for diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis based on data from the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:788-793. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal M, Castano YG, Paludo J et al. Impact of Cell of Origin on Outcomes After Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplant in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22:e89-e95. [CrossRef]

- Costa LJ, Feldman AL, Micallef IN et al. Germinal center B (GCB) and non-GCB cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphomas have similar outcomes following autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:404-412. [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz CH, Zelenetz AD, Kewalramani T et al. Cell of origin, germinal center versus nongerminal center, determined by immunohistochemistry on tissue microarray, does not correlate with outcome in patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL. Blood. 2005;106:3383-3385. [CrossRef]

- Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4184-4190. [CrossRef]

- Hamlin PA, Zelenetz AD, Kewalramani T et al. Age-adjusted International Prognostic Index predicts autologous stem cell transplantation outcome for patients with relapsed or primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:1989-1996. [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord R, Berning P, Niemann AL et al. The role of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in aggressive B-cell lymphomas: real-world data from a retrospective single-center analysis. Ann Hematol. 2021;100:2733-2744. [CrossRef]

- Armand P, Welch S, Kim HT et al. Prognostic factors for patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation in the positron emission tomography era. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:608-617. [CrossRef]

- Sauter CS, Matasar MJ, Meikle J et al. Prognostic value of FDG-PET prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2579-2581. [CrossRef]

- Flowers CR, Odejide OO. Sequencing therapy in relapsed DLBCL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2022;2022:146-154. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).