1. Introduction

ZSM-5 is a typical microporous zeolite with a three-dimensional ordered double-10-membered rings channel structure. Where, the diameter of “Z” shaped pore is about 0.53 nm × 0.56 nm, and the diameter of the rectilinear elliptical pore perpendicular to “Z” shaped one is about 0.51 nm × 0.55 nm. The two kinds of pore cross each other, and the aperture at the intersection is about 0.9 nm. As a solid-acid catalyst, ZSM-5 zeolite has been widely used in petrochemical industry. For example, in the field of FCC catalysis, ZSM-5, as an active component, can significantly increase the olefin/oil ratio in products [

1]. Most of the zeolite were reported to be prepared by using organic structure-directing agent (OSDA) as templates, which is usually used to direct the formation and to help stability of the zeolite framework. As OSDA, the most representative would be tetrapropylammonium cation, either in the form of its hydroxide (TPAOH) or in the form of a salt, preferably the bromide (TPABr), or a mixture of salt and hydroxide. The conventional method involving the synthesis of ZSM-5 zeolite is usually realized with the help of OSDA, which will waste resources, consume energy and pollute environment [

2]. As a consequence, it has become extremely desired to develop an eco-friendly method for synthesizing ZSM-5 without organic templates.

Synthesis of zeolite crystals from an OSDA-free system has been a very interesting alternative method because it avoids using organic templates and consequent calcination step. In general, OSDA often plays important roles in directing crystallization and filling micropores. In recent years, an OSDA-free synthesis of zeolites with the help of zeolite seeding has been successfully developed. Here, the zeolite seed play a similar role to the OSDA for directing zeolite crystallization from the amorphous precursor. Consequently, researchers have devoted themselves to synthesizing highly crystalline ZSM-5 in the absence of organic templates [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. For instance, Micro-scale, submicron-scale and nano-scale ZSM-5 yielded from a template-free system was reported to be prepared in an environment friendly seed-assisted one-step method [

2]. Hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite composed of nanocrystals was also synthesized by template-free seed-assisted technique in a gel precursor with ethanol and using aluminum isopropoxide as Al-species and tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) as silicon-species [

6]. MFI-SDS crystals were reported to be assembled from the rod-like nanocrystals with the same aligned direction in an OSDA-free synthesis system in the presence of the zeolite seeds[

7]. For another example, nanocrystalline ZSM-5 was reported to be synthesized with the help of a seed suspension liquid obtained by dispersing the calcined seed in ethanol. However, in these synthesis, organic substance is more or less involved. For example, TEOS [

6,

7] as silicon resource, or Al(O

iPr)

3 [

6,

11] as aluminum resource, or crystals containing OSDA as seeds [

2,

8,

10], or suspension seeds in ethanol [

9,

10] will inevitably bring organics especially alcohols in the synthesis system. The organic matter such as ethanol, which is the directly added or yielded from hydrolysis of raw materials in the synthesis system, may play a template by filling in the zeolite micropores [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] because of tetrahedron formed by ethanol and sodium ions, which can accelerate the nucleation and crystallization [

12,

13].

In the present work, a calcined commercial ZSM-5 zeolite was used as a seed, sodium aluminate as an aluminum source, silica sol as a silicon source, which ensures that there is no any organic substance (template) in the synthesis system, and polycrystalline ZSM-5 aggregates consisting of rod-like nanocrystals are successfully prepared in a completely OSDA-free system. The effects of the chemical component (Si/Al ratio) and the added amount of seeds, and crystallization time on the synthesis of ZSM-5 zeolite were investigated in detail.

3. Results and Discussion

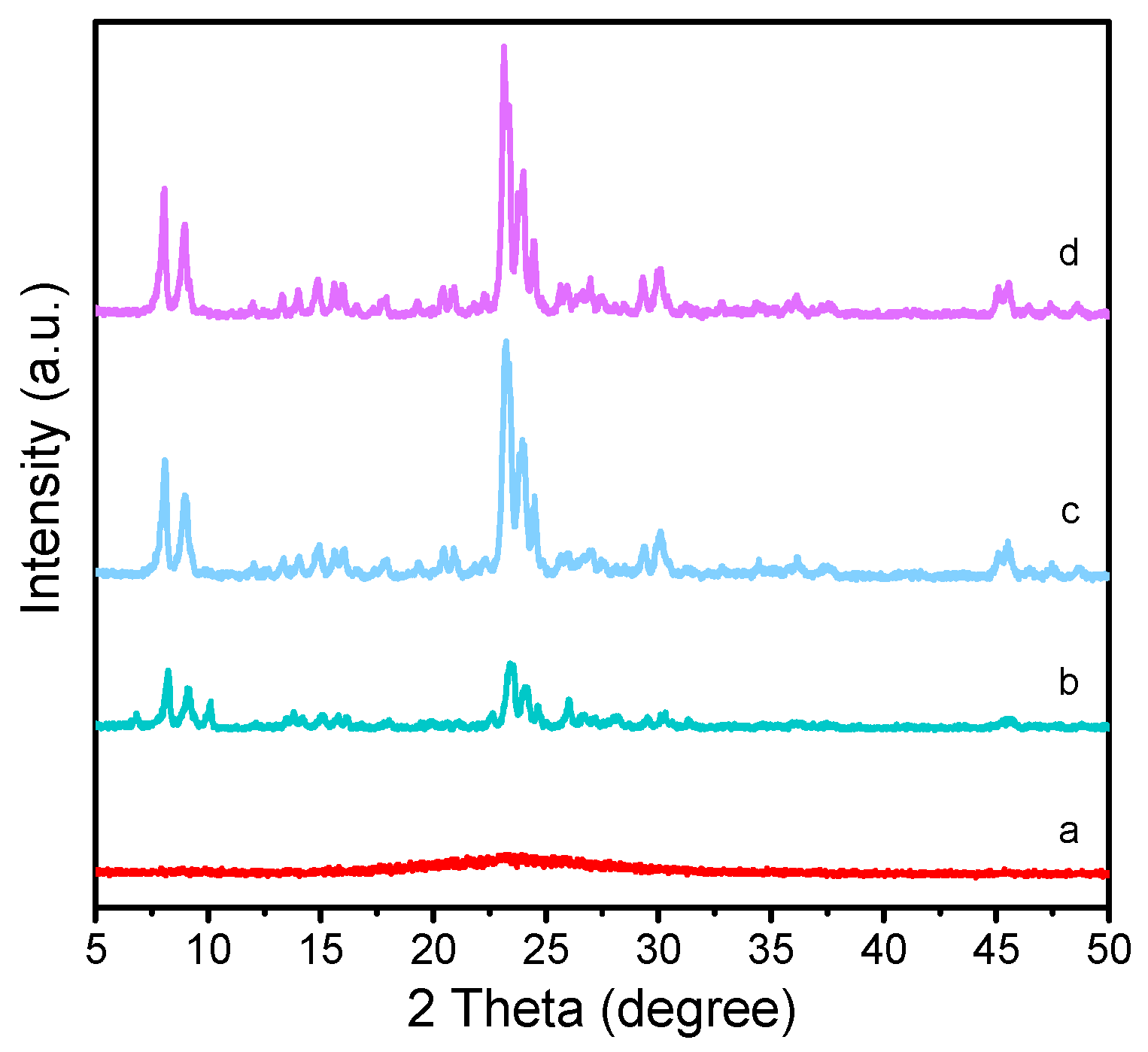

Figure 1 is XRD pattern of the as-synthesized samples with different added amount of the seeds. The diffraction peaks at 7.88°, 8.76°, 23.0°, 23.84°, and 24.3° can be ascribed to the characteristic diffraction peaks of MFI topology (JCPDS: 44-00033) [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. It can be seen that the added amount of the crystal seed plays an important role in the formation of ZSM-5 zeolite. A gel precursor without seed only generates an amorphous phase in the as-synthesized sample Z518-0-48. When the added amount of seed is lower than 2.8 wt.%, except for the characteristic diffraction peaks of MFI topological structure, two obvious diffraction peaks at 6.5° and 9.8° attributing to MOR zeolite emerge in the as-prepared sample Z518-2.8-48, suggesting that the sample Z518-2.8-48 mainly consisting of MFI topological structure mingled with a little of MOR can be obtained. It can be inferred from

Figure 1 that about 5.6 wt.% seed added in the gel precursor is enough to induce in pure and high crystallization ZSM-5 zeolite.

Figure 1 also displays that when seed amount is further increased from 5.6 wt.% to 11.2 wt.%, the as-synthesized sample Z518-11.2-48 has the similar while slightly intense characteristic diffraction peaks to the sample Z518-5.6-48 (

Figure 1). The above result also suggests that the further increased amount of the seed has little effect on the topological structure of the as-synthesized samples.

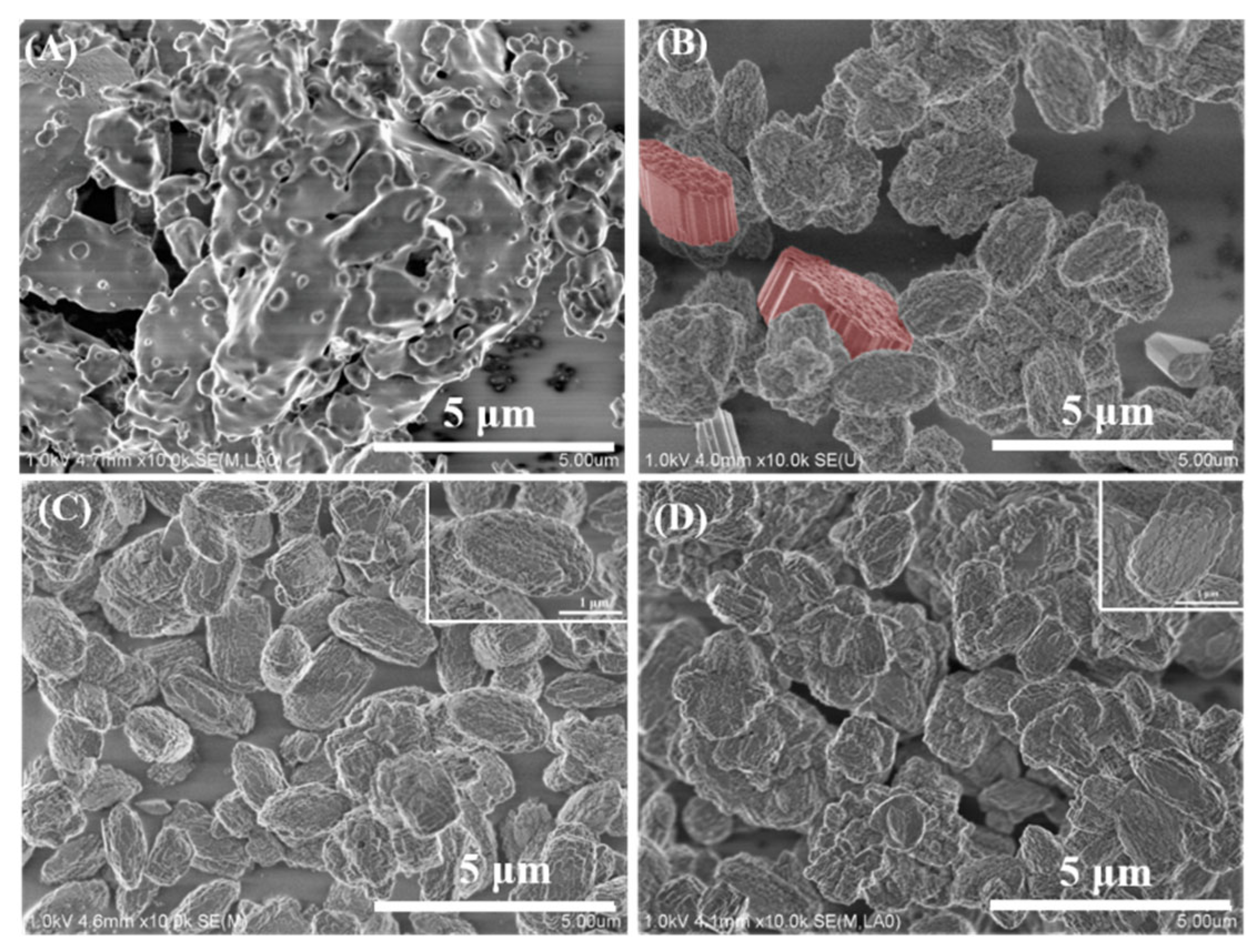

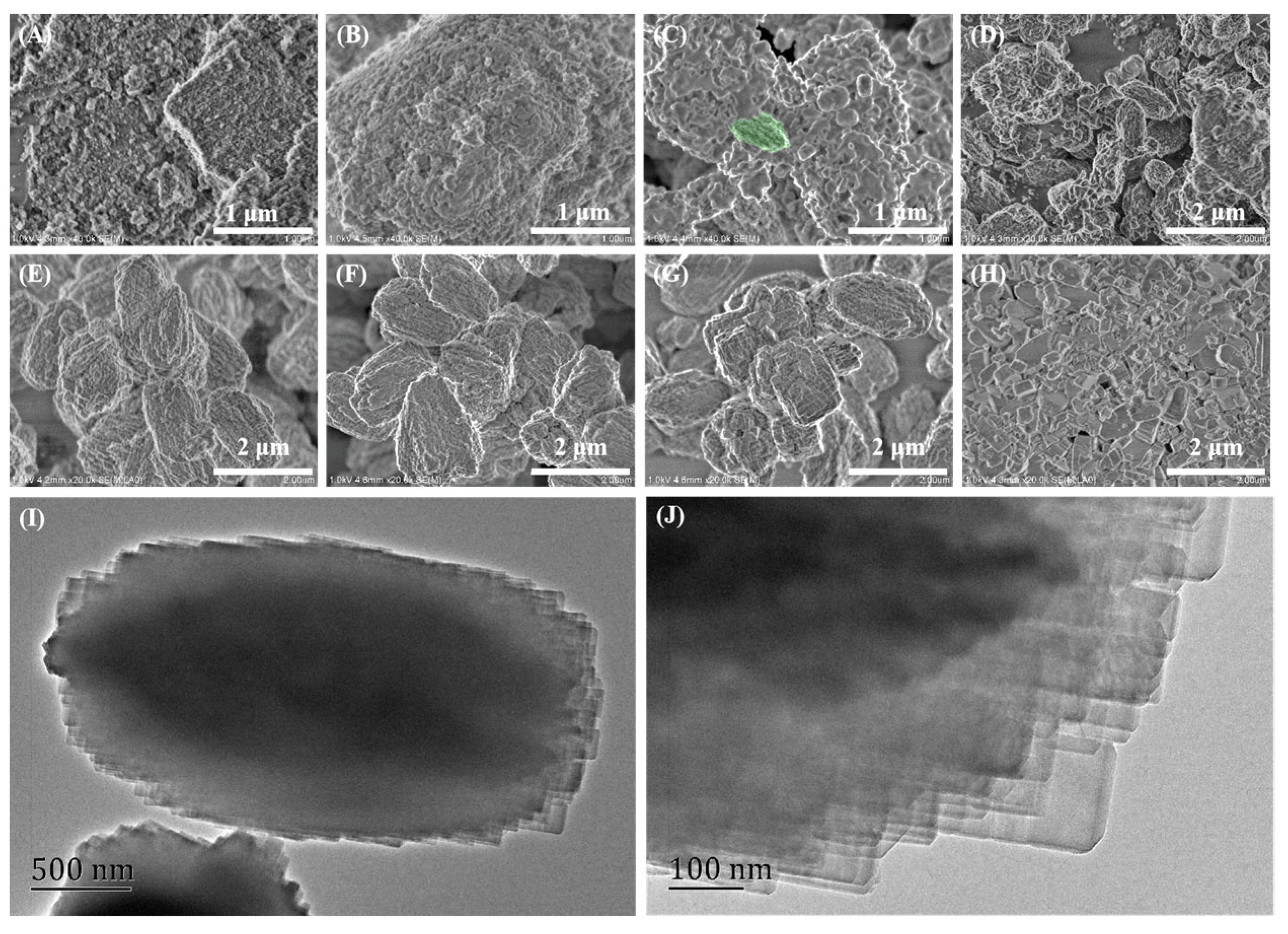

As shown in

Figure S1A1-A2, the SEM image of NK-18 suggests that the initial ZSM-5 serving as the seed is mono-dispersed single crystal with a size of about 1-2 μm. It can be seen from

Figure 2 and

Figure S1 that the added amount of the crystal seed strongly affects the formation and the morphology of the as-made samples. As shown in

Figure 2 that the morphology of the as-prepared samples is very different from that of the seed crystals. The as-synthesized sample Z518-0-48 yielded from a gel precursor without any seed displays a worm-like monolith (

Figure 2A), agree with the result of XRD as shown in

Figure 1 very well. A precursor with an appropriate amount of seed gives the as-prepared samples with a polycrystalline morphology. As exhibited in

Figure 2B-D, all the samples Z518-2.8-48, Z518-5.6-48, and Z518-11.2-48 display polycrystalline aggregates, which further consist of loosely aggregating primary nanocrystals with an estimated size of about less than 100 nm (

Figure S2). As shown in

Figure 2B, some plate-like crystals ( the part rendered in red) can be found, which may be the impure MOR zeolite, which is in agreement with the above XRD result. No any amorphous form can be obviously detected in Z518-2.8-48, Z518-5.6-48, and Z518-11.2-48 samples, suggesting that the appropriately added amount of the seed can promote the as-synthesized sample to be highly crystalline and avoid the formation of amorphous form and impure MOR phase. As shown in

Figure S3, both of the sample Z518-5.6-48 and Z518-11.2-48 have the similar N

2 adsorption-desorption isotherms with a combination of type-I and type-IV, indicating that the coexistence of the micropore and mesopore. The corresponding BJH pore size distribution curve of samples shows that a mesopore distribution ranging from 5 to 50 nm can be found in the two samples, which can be ascribed to the intercrystalline mesopore structure resulted from the loosely aggregating primary nanocrystals in the polycrystalline aggregates as shown in

Figure S2. The N

2 adsorption data as shown in

Table S1 shows that the Z518-5.6-48, and Z518-11.2-48 samples have the similar porosity structure and crystalline, may also suggest that the further increased amount of the seed from 5.6 % to 11.2 % has little effect on the porosity structure and the elevated crystalline of as-synthesized samples.

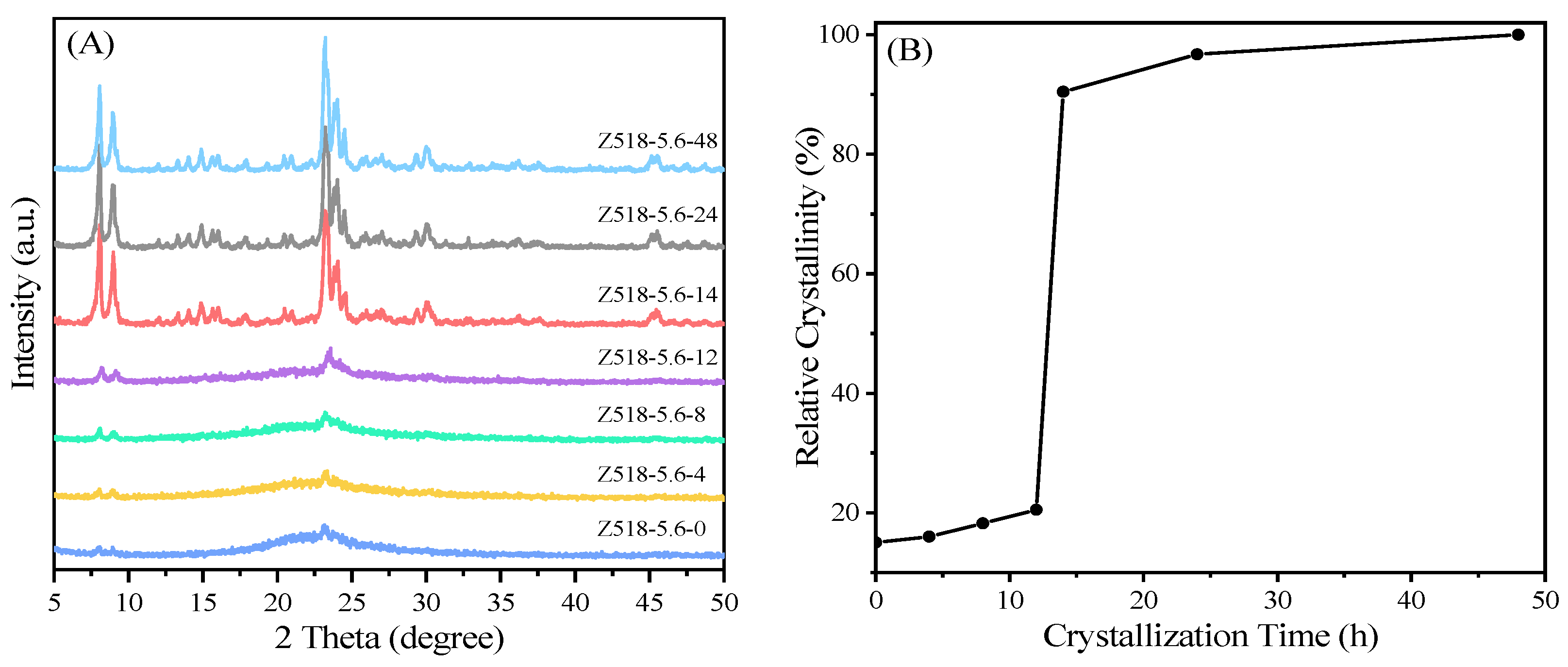

XRD pattern of the as-made samples yielded from the same gel precursor with different crystallization time and the corresponding crystallization kinetic curve of the as-synthesized samples are shown in

Figure 3. The characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 7.9°, 8.8° and 23° in sample Z518-5.6-0 can be attributed to the influence of ZSM-5 seed in the precursor, indicating that ZSM-5 crystal seeds can remain relatively stable during the preparation of gel precursor. The main reason is that the Si/Al ratio of seed NK-18 is relatively low, and the zeolite framework with negative charge has electron repulsion on OH

–. In the alkaline environment, the Al atom in the framework will protect the nearby Si atom from the nucleophilic attack of hydroxide ions, thus forming the protective barriers for Si-species [19, 20]. When 0 h< “t” (the crystallization time) <12 h, the characteristic diffraction peaks attributed to MFI topological structure in the synthesized samples Z518-5.6-4, Z518-5.6-48 and Z518-5.6-12 gradually increase with the prolonged crystallization time (

Figure 3A), while the corresponding relative crystallinity of the as-prepared samples such as Z518-5.6-12 is still low (<20%,

Figure 3B), indicating that the synthesis gel system is still in the nucleation induction stage [

21]. When the crystallization time “t” ≥ 14 h, the characteristic diffraction peaks of the as-synthesized samples increase sharply (

Figure 3A), and the relative crystallinity of corresponding sample Z518-5.6-14 reaches about 92 % of the sample Z518-5.6-48 (

Figure 3B).

As shown in

Figure 4, all of the samples yielded from the same gel precursor with the different crystallization time exhibit the characteristic vibration bands of MFI topological structure. For example, the absorption bands near 453 cm

−1, 553 cm

−1 and 790 cm

−1 belong to the internal framework vibration, the double five-member ring vibration and the asymmetric stretching of the AlO

4 and SiO

4 tetrahedron of ZSM-5 zeolite, respectively. It was reported that the ratio of the absorption band strength of 553 cm

−1 to that of 453 cm

−1 could be used to evaluate the degree of crystallization of the samples [

22]. It can be inferred from

Figure 4A that with the extended crystalline time, the relative degree of crystallinity of the as-synthesized samples gradually increase. This is consistent with the results as shown in

Figure 3B. In addition, the asymmetric stretching vibrations of TO

4 (T = Si or Al) at 1090 cm

−1 is closely related to the Si/Al ratio of the zeolite framework, and the increased Si/Al ratio will cause the vibration moving towards a high wavenumber. It can be inferred from

Figure 4B that the prolonged crystalline time causes the asymmetric stretching vibrations of TO

4 to move towards the low wavenumber, may mean that with a prolonged crystalline time, more Al-species are inserted into the zeolite framework, which offers the as-synthesized samples with the decreased Si/Al ratios.

As shown in

Figure 5, The shorter crystalline time such as less than 8 h, amorphous phase is detected to be the main body in the as-prepared samples. When the crystalline time is longer than 14 h, all the crystals in the as-synthesized samples Z518-5.6-14, Z518-5.6-24 and Z518-5.6-48 have the similar polycrystalline morphology composed of primary nanocrystals, and no any amorphous phase can be obviously observed, agreeing with the results as shown in

Figure 3 very well. It can be seen from

Figure 5 I-J that the crystals in the as-synthesized sample Z518-5.6-48 are polycrystalline aggregates consisting of the rod-like nanocrystals estimated at about less than 100 nm in diameter. The TEM image of sample Z518-5.6-48 also shows that some of the crystals in the as-synthesized may have a core-shell structure: a monocrystal core warped by a polycrystalline shell, which makes the as-synthesized crystals seeming more like a polycrystalline aggregate.

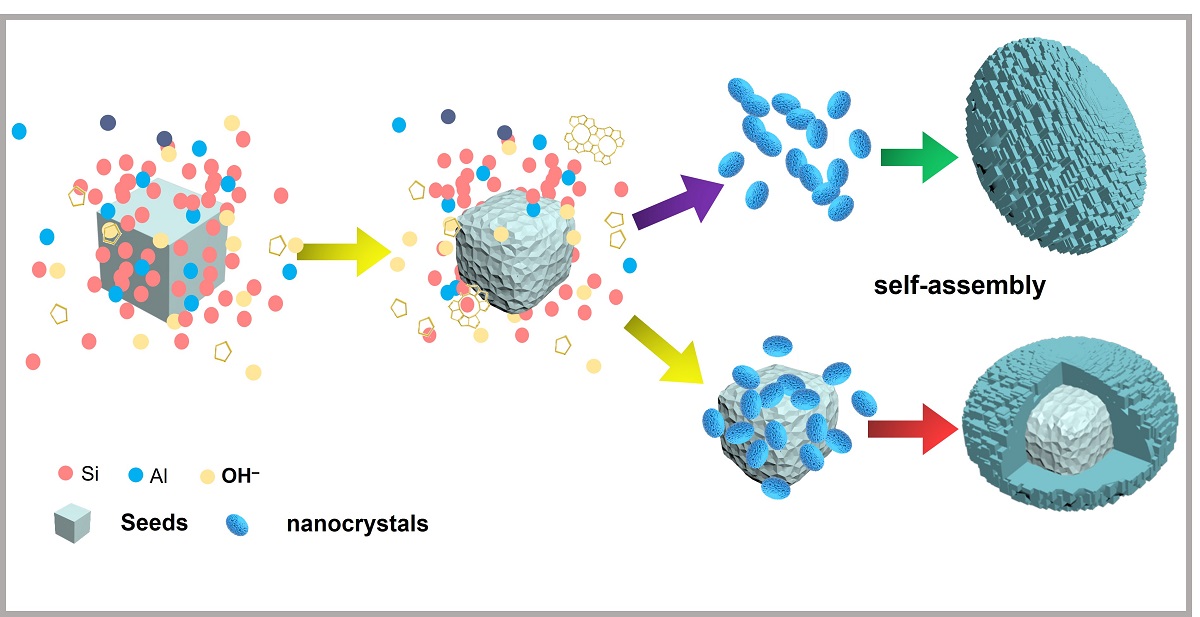

The formation process of the as-prepared polycrystalline aggregates can be summarized as follows: Despite the commercial ZSM-5 (NK-18) has a low framework Si/Al ratio, which ensures NK-18 zeolite acting as the crystal seed to remain a relatively stable during the preparation of gel precursor [

19,

20]. While, in the subsequent hydrothermal synthesis process, it is inevitable that the ZSM-5 crystal seeds are partially dissolved by the alkaline gel precursor. The dissolved crystal seeds will release abundant primary/secondary structural units, which contributes to stimulating an explosive nucleation and results in the formation of a large number of nanocrystals [

23]. During the hydrothermal crystallization, zeolite seeds along with the primary/secondary structural units resulted from partially dissolved seeds play the similar role to OSDA for directing zeolite crystallization from the amorphous gel precursors. Due to the high surface energy, the nanocrystals caused by the explosive nucleation in a short time are highly unstable. In order to decrease the surface energy, the nanocrystals will suffer from interattraction and then form polycrystalline aggregates by self-assembly [

6,

7,

17], or be adsorbed on the external surface of the reserved seed crystals and form the polycrystalline aggregates with the reserved seed crystal as cores and rod-like nanocrystals as polycrystalline shell [

24].

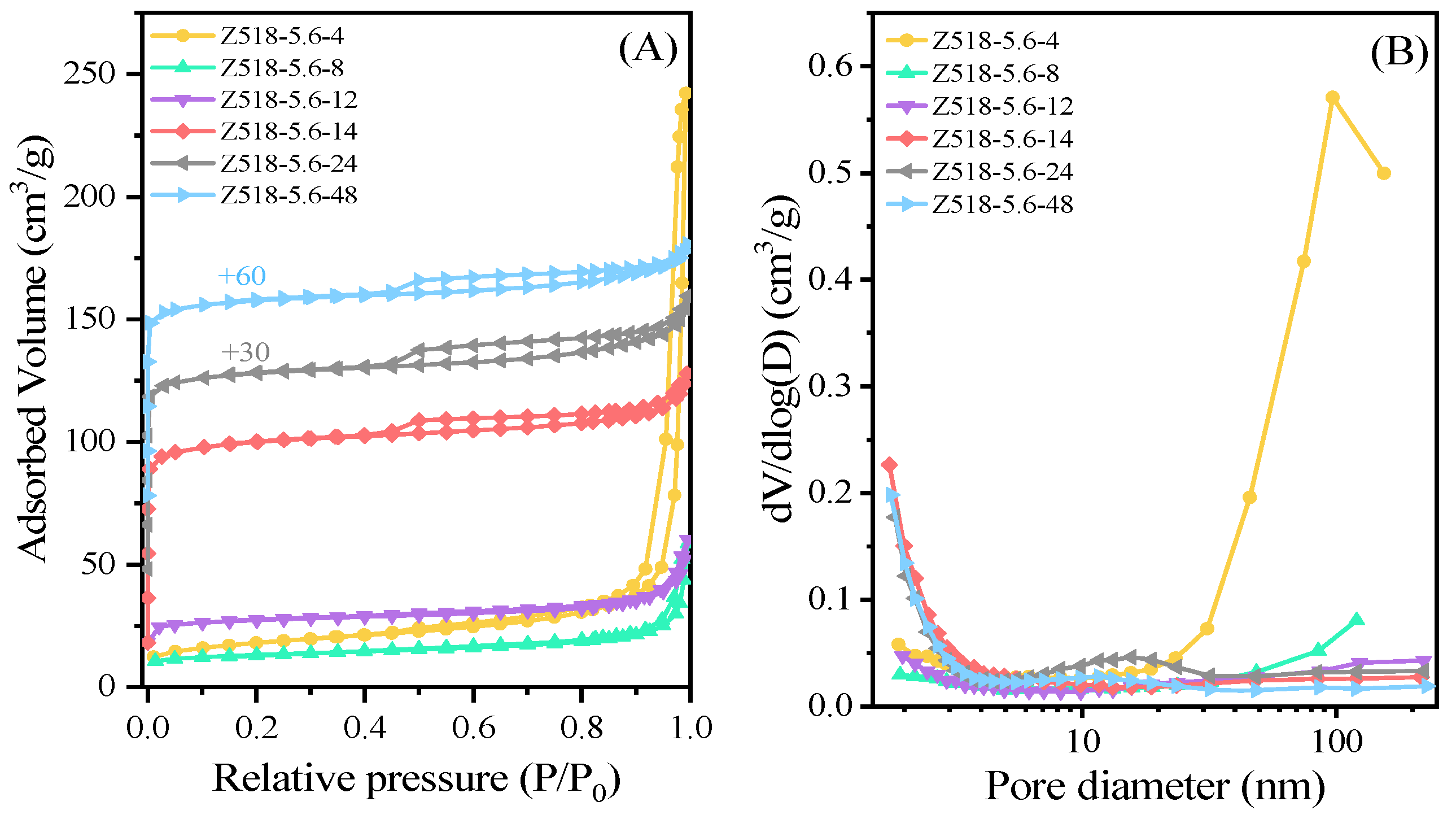

Figure 6 is the N

2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and the corresponding BJH pore size distribution curves. It can be seen from

Figure 6A that the N

2 adsorption isotherm curves exhibit a steep increase at the relative pressure p/p

0 < 0.02 and a hysteresis loop at a relative pressure p/p

0 of 0.45-0.8, indicating the co-existence of intrinsic micropores and meso- or/and macropores in the samples. The hysteresis loop at a relative pressure p/p

0 of 0.45-0.8 can be attributed to the capillary condensation [

17] in open mesopores or macropores obtained by filling the interparticles spaces of primary MFI zeolite in the aggregates. Moreover, hysteresis loops at p/p

0>0.8 are present in the nitrogen isotherm of samples especially Z518-5.6-4 yielded from a shorter crystalline time, which can be caused by the macropores in the worm-like amorphous phase as shown in

Figure 5B. The BJH pore structure distribution calculated from the adsorption branch of the isotherms are shown in

Figure 6B. Samples Z518-5.6-14, Z518-5.6-24 and Z518-5.6-48 have an obvious mesopore distribution centering at about 15 nm, attributing to the intercrystalline mesopores between the primary MFI crystals in the aggregates [

6,

7,

8,

11]. Larger pore distribution centering at about more than 100 nm detected in the samples Z518-5.6-4 and Z518-5.6-8 can be ascribed to the macropores in the worm-like amorphous phase (

Figure 5B-C). As shown in

Table 1, with the prolonged hydrothermal treatment time, the microporous properties such as microporous areas (S

mic), microporous volume (V

mic) display a continuously increased trend, suggesting a progressively increased “RC”, which is in agreement with the result as shown in

Figure 3B.

In order to investigate the effect of the chemical component of the seed on the synthesis of ZSM-5, seeds such as NK-18, NK-27, NK-200 with different Si/Al ratio were used for preparing ZSM-5 in an organic-templates-free system. It can be inferred from

Figure S4A that the chemical component of the seeds has little effect on the synthesis of pure phase ZSM-5 zeolite. All the samples Z518-5.6-48, Z527-5.6-48 and Z5200-5.6-48 have the similar characteristic diffraction peaks attributing to MFI topological structure while with a slightly weakened peak intensity with the increased Si/Al ratios of the used seeds (

Figure S4A). It can be seen from

Figure S4B that the samples induced by the different seeds have the similar N

2 adsorption-desorption isotherm, and the microporous properties of the as-synthesized samples display a slightly and expressively decreased trend with enhanced Si/Al ratios of the used seeds (

Table 2). The above result means that low Si/Al ratios seeds may be in favor of directing and promoting a fast crystallization of zeolites. It can be seen from

Figure S5 that the samples Z527-5.6-48 and Z5200-5.6-48 induced by the different seeds of NK-27 and NK-200 have the similar polycrystalline aggregates to the Z518-5.6-48, rather different from the corresponding seeding crystals (

Figure S1), and no any amorphous phase can be found in the as-synthesized samples. Element analysis decided by EDS is displayed in

Figure S6, Combining with the result as shown in

Table 2, the seeds with the different Si/Al ratios has a little effect on the chemical component of the as-synthesized ZSM-5 samples, and all the samples have the similar Si/Al ratio of about 11.3-11.6, much lower than those of the used seeds. As shown in

Figure S7, all of the samples Z518-5.6-48, Z527-5.6-48 and Z5200-5.6-48 display the similar NH

3-TPD curves. In order to determine the acid amount, NH

3-TPD curves were carried out peak-differentiating and fitting, and shown in

Figure S8. It can be seen that all of the acid sites of the as-synthesized samples induced by the seeds with different Si/Al ratios can be fitting into weak acid, moderate-strength acid, and strong acid centers [

8,

17]. It can be seen from

Table 2. that the three samples have the comparable acid density except Z518-5.6-48 yielded from the gel precursors with low Si/Al ratio seeds has more strong acid sites than the samples Z518-5.6-48 and Z527-5.6-48 induced by seeds with relatively high Si/Al ratios.