1. Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are multipotent stem cells that give rise to all blood cells [

1]. They are located in the bone marrow (BM) niche where they maintain blood and immune cell homeostasis through a balance of self-renewal and differentiation [

2]. Alterations of HSCs or bone marrow homeostasis are a major cause of blood diseases such as leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma [

3,

4,

5]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the mainstay of the therapies of acute leukemias in allogeneic settings, and that of other hematopoietic malignancies in autologous settings in high-risk multiple myeloma [

6,

7] and aggressive refractory/relapses lymphomas [

8].

Several attempts have been made in the past to expand true HSCs using

in vitro established techniques in the presence of cytokines and starting with bone marrow, umbilical cord blood (UBC) or mobilized peripheral blood cells [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. These attempts have not generated so far a methodology to manufacture transplantable true HSCs in clinically applicable settings. The use of double cord blood transplantation, especially in adults, has been used to circumvent these difficulties [

14].

Generation of functional and engraftable HSCs from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) would represent a step forward for improving bone marrow transplantation. Indeed, the self-renewable capacity of iPSCs combined with the HLA gene editing would provide a renewal and universal stock of material for HSCT. However, current protocols do not enable the generation of mature and engraftable HSCs [

15]. With the current protocols, iPSC-derived HSCs can produce matured blood cells in a process resembling primitive hematopoiesis [

16,

17] but they lack engraftment and repopulation capacities. However, BM and UCB derived HSCs are mature which confers them the engrafting potential [

18].

A better knowledge of the mechanisms of iPSCs hematopoietic differentiation and the improvement of the current protocols to generate more BM/UCB HSCs-like cells from iPSCs are needed for developing HSCs generation from iPSCs.

Previous studies have shown the implications of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in hematopoietic stemness potential and maintenance [

19,

20]. RET (rearranged during transfection) protooncogene is a RTK which transmits a proliferative signal in the presence of its co-receptor GFR-alpha (GFRα1) and in response to GDNF-ligands families (GLF). RET is known to be expressed in intermediate mature myeloid cells and in acute myeloid leukemia [

21,

22]. Previous studies have suggested that RET plays a key role in the emergence of hematopoietic potential in mice [

23]. Others showed the improvement of cord blood HSCs survival and expansion when RET pathway is activated by the addition of its ligand/coreceptor GDNF/GFRα1 [

24]. Moreover, HSCs frequency is four-fold higher in the RET-positive compartment compared to RET-negative cells. However, its effect during iPSCs hematopoietic differentiation has yet to be characterized.

In order to test the effect of RET activation during iPSC-derived hematopoietic differentiation, we generated different iPSC models of RET activation with the lentiviral overexpression of wild-type receptor RET (RETWT) or a mutated RET (RETC634Y) which was overexpressed in normal IPSCs. In addition, we have used a patient-derived iPSC containing the mutated RET (RETC634Y) or its CRISPR-corrected isogenic control. With the use of these tools, we have tested the hematopoietic potential of iPSCs using in vitro assays. Interestingly, we show that RET activation during iPSCs hematopoietic differentiation reduces the HSCs stemness potential by the activation of the MAPK pathway and we identify, using a transcriptomic approach some regulatory factors, such as DLK1, that could be involved in hematopoietic inhibition. This work provides a better understanding of the effects of RET activation during iPSCs hematopoietic differentiation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generation of iPSCs

PB33-WT and PB68-WT were both generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors with the informed consents according to the Declaration of Helsinki. PBMCs were reprogrammed by non-integrative Sendai viral transduction. Pluripotency was characterized by FACS and teratoma assays. Generation of RET mutated iPSC iRET

C634Y and its isogenic CRIPSR corrected control iRET

CTRL have been previously described [

25,

26].

2.2. iPSC cultures

iPSCs were cultured in feeder-free condition on Geltrex coated dishes (A1413201; ThermoFisher Scientific, France) and fed daily with Essential 8 flex Medium (A2858501; ThermoFisher Scientific, France). iPSCs were passaged twice a week with EDTA dissociation (0.5 mM).

2.3. Hematopoietic differentiation from iPSCs

Hematopoietic differentiation of iPSCs has been performed using a STEMDiff hematopoietic kit (05310; STEMCELL Technologies, France) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, iPSCs have been dissociated in aggregates of 50-100 μm by using EDTA (0.5 mM). 50 aggregates have been seeded per well in a 12-well cell culture plate (Corning, France) coated with Geltrex (A1413202; Gibco, France). The medium was changed according to the manufacturer’s instruction and floating cells were harvested on day +13 of hematopoietic differentiation. For GDNF/GFRα1 experiment, 100 ng/mL of GDNF & GFRα1 mixed 1:1; (212-GD-010, 714-GR-100; R&D Systems, France) were added to the media.

2.4. Flow cytometry

The viability of the cells collected from day +13 of hematopoietic differentiation was evaluated with Trypan blue and living cells were stained with the following antibodies (Table 1) in PBS at 4°C for 20 minutes.

Cells were thereafter washed and resuspended in PBS. Stained cells were analyzed with a BD LSRFortessaTM (BD Biosciences, USA) flow cytometer and FlowJo analysis software.

2.5. Clonogenic assays

Non-adherent cells collected at day +13 of hematopoietic differentiation were counted and plated in methylcellulose-based medium (MethoCultTM H4434; STEMCELL Technologies, France) at the concentration of 5000 cells/dish and incubated for 14 days in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. After 14 days in methylcellulose, colonies were enumerated.

2.6. RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and quantitative qRT-PCR

Total intracellular RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (74104; Qiagen, Germany) and 1 µg was reverse transcribed using a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR kit (Superscript III 18080-44; ThermoFisher Scientific, France). An aliquot of cDNA was used as a template for qRT-PCR analysis using a fluorescence thermocycler (ThermoFisher Scientific QuantStudio 3

TM) with FastStart Universal SYBR Green (04913914001, Roche, Lithuania) DNA dye. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are shown in

Supplementary Materials Table S1. Relative expression was normalized to the geometric mean of housekeeping gene expression and was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

2.7. Western blots

Cells were lysed in ice with RIPA buffer. Separation of proteins was done by electrophoretic migration on a NuPAGE™ 4-12 % Bis-Tris gel (NP0323BOX; ThermoFisher, France) under denaturing conditions. The proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane pre-activated with methanol. After saturation with TBS-Tween 5% BSA for 1h and hybridization of the membranes with primary antibody overnight (1:500, Ret #132507, R&D System, USA; 1:1000, Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (E10) #9106, CellSignaling, USA; 1:200, p-Ret (Tyr 1062)-R: sc-20252-R, SantaCruz, USA; p63 [EPR5701] #ab124762, Abcam, USA; 1:60000, B-Actin-Peroxidase #A3854, Sigma, France) and secondary antibodies coupled to HRP. Membranes were revealed by chemiluminescence with SuperSignal West Dura or Femto reagents and data were acquired using G:BOX iChemi Chemiluminescence Image Capture system.

2.8. Production of lentiviruses and viral transduction

To produce RET-expressing lentiviruses, we used Lenti-X 293T as a packaging cell line and psPAX2.2, and pMD2.G as packaging vector and envelope vector, respectively. Briefly, the Lentix-293T cell line was cultured on a T150 mm in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (11560636; Gibco, France) and 100 U/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (PenStrep) solution (11548876; Gibco, France) and co-transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (L3000015; ThermoFisher, France) with 20 μg of packaging vector ps-PAX2.2 (Addgene, USA), 10 μg envelope vector of pMD2.G (Addgene, USA) and 30 μg transfer vector. The supernatant was collected at 24h and 48h. RET

WT overexpression plasmid was a gift from Gordon Mills & Kenneth Scott (Addgene plasmid # 116787;

http://n2t.net/addgene:116787; RRID:Addgene 116787). The plasmid RET

C634Y was purchased from VectorBuilder (Guangzhou, China).

Transduction of iPSC with RET lentiviruses was performed by using freshly passaged iPSC. Puromycin selection was performed by using 1 μg/mL of Puromycin (12122530; Fisher Scientific, France).

2.9. Transcriptomic experiments

Total RNA from hematopoietic cells derived from iRET

C634Y and from its CRISPR correction iRET

CTRL were treated in duplicates to performed Clarium S Assay human microarray (902927; ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Robust microarray analysis (RMA) [

27] normalization was applied to the resulting transcriptome matrix with Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) version 4.0.1.36 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

2.10. Bioinformatics analysis

Bioinformatics analyses were performed in R software environment version 4.1.0. Supervised differential expression analysis between RET-mutated cells and their CRISPR corrected counterparts was performed LIMMA R bioconductor package version 3.48.3 [

28]. Expression heatmap up regulated genes by RET mutation was drawn with pheatmap R-package version 1.0.12. Heatmap classification was performed with Euclidean distances and Ward.D2 method. Functional enrichment was performed with Toppgene web site on Gene Ontology Biological Function and DisGeNET diseases databases [

29]. Functional molecular networks were drawn with Cytoscape standalone software version 3.6.0 [

30].

4. Discussion

Generation of HSC with long-term repopulation potential from iPSCs is a major goal of research which could circumvent the unmet need of new sources for HSCT. However, iPSC-derived hematopoiesis resembles the first wave of hematopoiesis because it produces mature blood cells only and not long-term engraftable HSCs [

16,

17]. Several studies show the possibility for iPSC-derived HSCs from human teratoma to migrate and repopulate the BM [

35,

36]. Other studies generate short-term engraftable HSC from iPSC by the ectopic expression of transcriptional factors such as HOXA9, ERG, RORA, SOX4, and MYB [

37,

38]. Nevertheless, no engraftable HSCs were generated without ectopic transcription factor expression or teratoma formation. Therefore, protocols for hematopoietic differentiation must be optimized, or mechanisms of differentiation must be better understood to develop iPSCs derived HSCs for clinical applications.

Human HSCs are characterized by several surface markers. The historical marker of human HSC is the CD34. CD34+ population is heterogenous but all the stem cells in the BM express this marker [

39]. Most of the CD34+ cells co-express CD38 but only the CD38- fraction can generate multi-lineage colonies in immune-deficient mice [

40,

41]. In addition to well established HSC markers [

39,

40,

41], CD49f has been shown to be a specific marker of HSC and a demarcation between HSCs and multipotent progenitors. Moreover, CD49f+ cells were highly efficient in generating long-term multilineage grafts [

42].

Previous studies have shown that RET could be important for HSC generation and expansion. Indeed, RET has been identified as a crucial player in the development of hematopoietic potential in mice [

23]. RET neurotrophic factor partners are produced in the HSCs environment and stimulate survival, expansion, and function of HSCs. Null mutation of RET leads to the loss of Bcl2 and Bcl2l1 surviving cues. Another study has also demonstrated that the activation of the RET pathway by the addition of its ligand/coreceptor GDNF/GFRα1 improves cord blood HSCs survival and expansion [

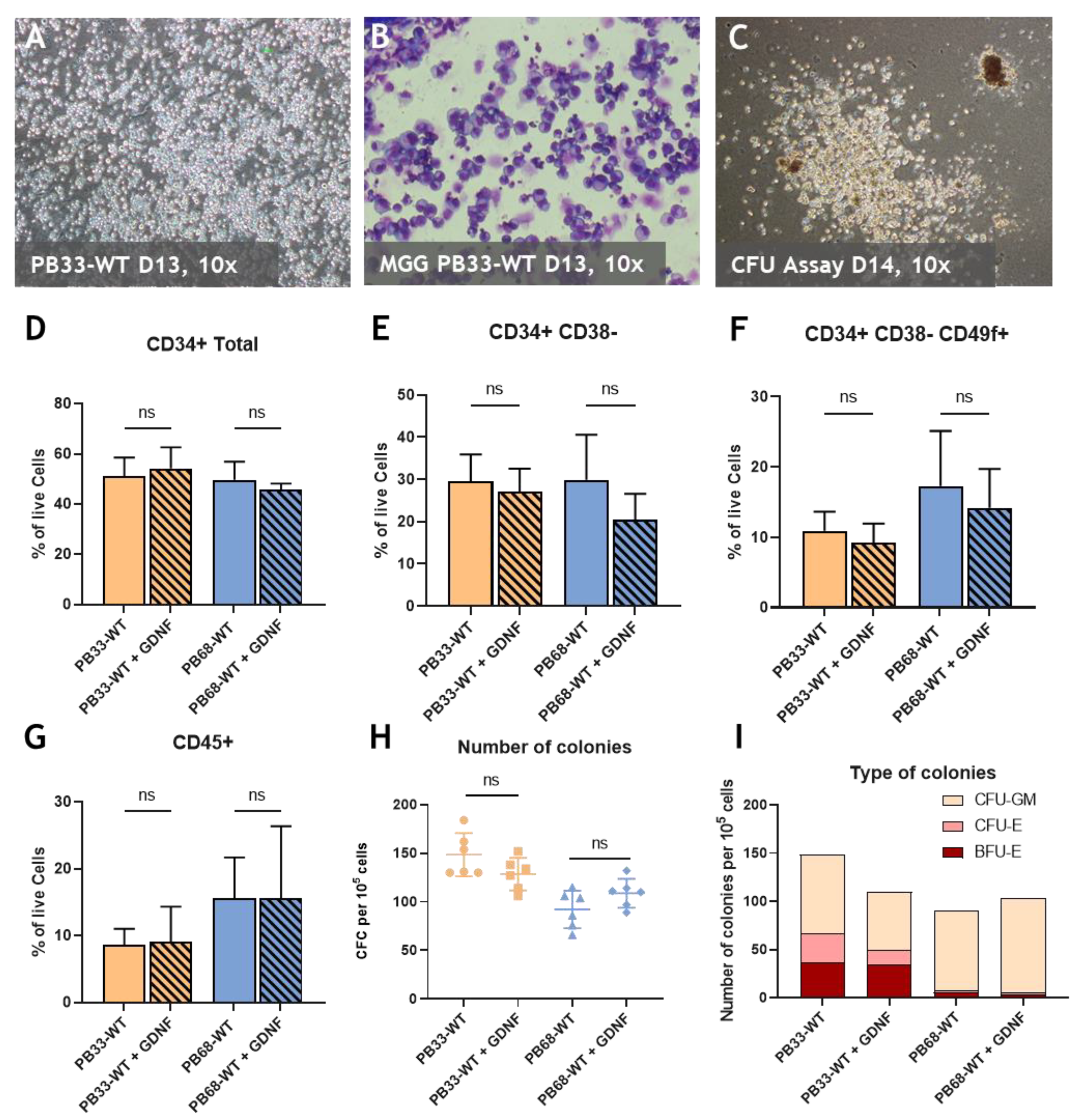

24]. However, the impact of RET during iPSCs hematopoietic differentiation remains to be characterized. Here, we observed no effect of RET activation by GDNF/GFRα1 addition during hematopoietic differentiation of WT iPSCs (

Figure 1). Then we generated iPSC overexpressing the gene RET

WT and the mutant RET

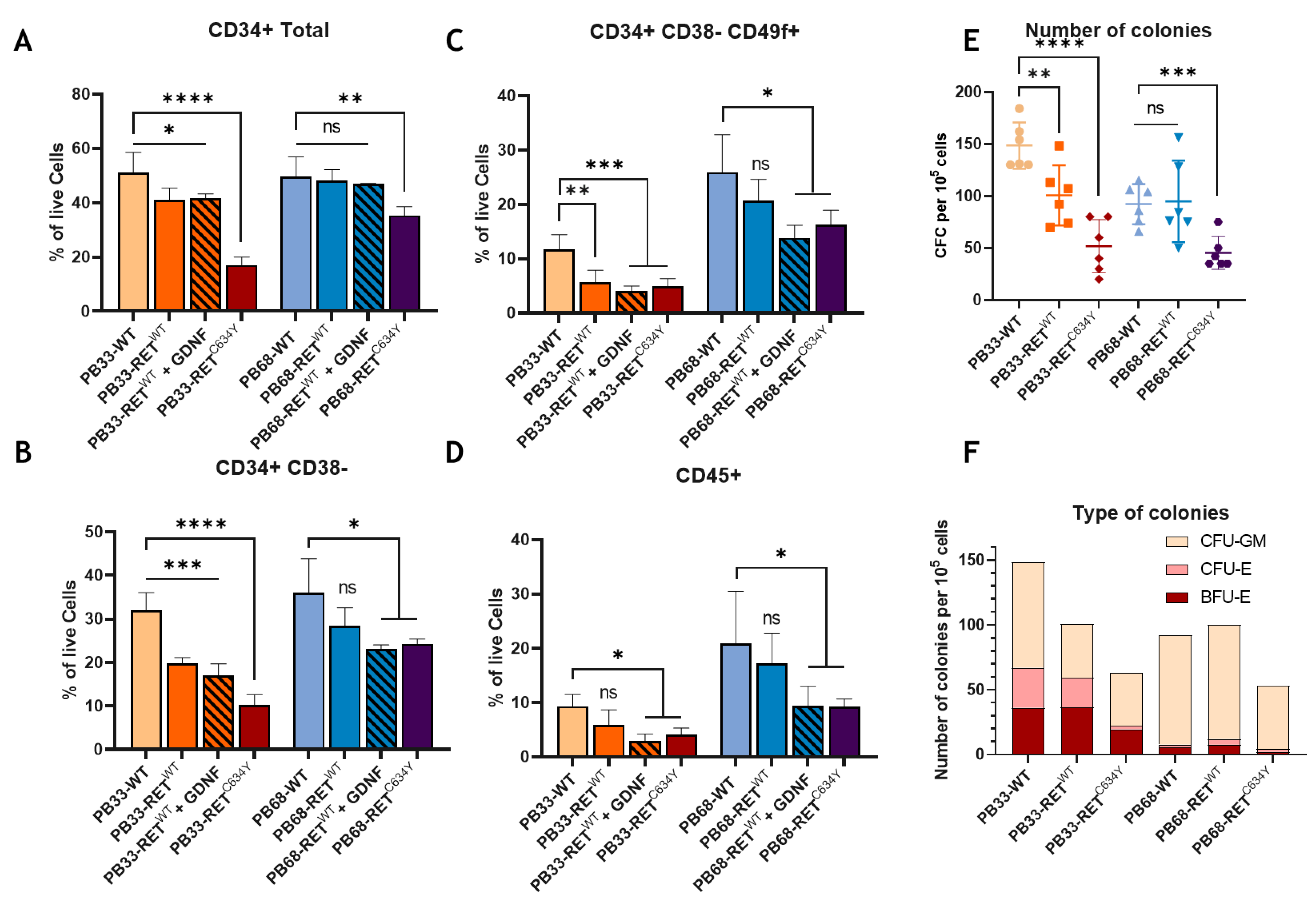

C634Y. Our results show that RET activation decreases the number of hematopoietic cells with HSC phenotype as well as that of hematopoietic progenitors. (

Figure 2). The hematopoietic potential of iPSCs is also altered by the activation of exogenous RET because their capacity to form hematopoietic colonies is also reduced. This inhibitory effect is enhanced with the level of RET activation as shown by the addition of GDNF in the RET

WT conditions. (

Figure 2). We have observed that constitutive activation of the RET

C634Y mutant is associated with the most severe inhibitory effect in both iPSCs. These results strongly suggest a relationship between RET constitutive phosphorylation and hematopoietic differentiation.

We have evaluated the effect of RET activation in two different iPS cell lines (PB33-WT and PB68-WT) by overexpression of RET. Interestingly, hematopoietic differentiation gave rise to different outcomes in these two cell lines. In

Figure 1 we can notice that the percentage of HSC (CD38- CD34+ CD49f+) and hematopoietic cells (CD45+) are different between the two WT conditions. The number and the type of colonies were found to be different as well. Indeed, there were almost no CFU-Es and BFU-Es observed for PB68-WT whereas in PB33-WT almost fifty percent of the colonies formed erythroid colonies. The effect of RET

WT overexpression is also different between the two cell lines where a much stronger activation of RET is needed to observe an effect in PB68

Figure 2). These differences could be explained by the genotypic background of the donors. Indeed, a study shows that 5-46% of the variation in different iPSC phenotypes arises from differences between individuals [

43].

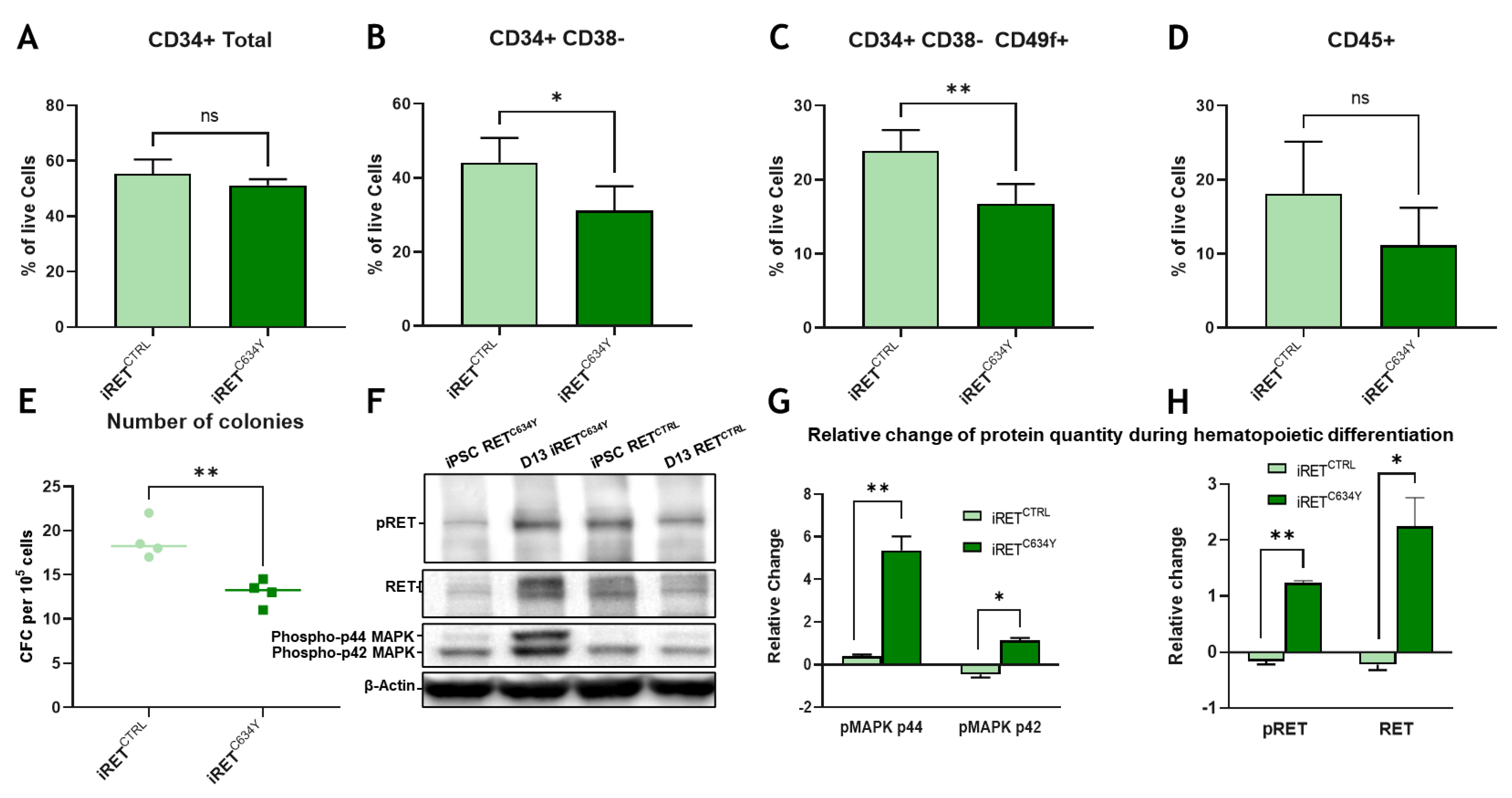

We next tested the effect of an endogenous RET

C634Y mutation from a patient-derived iPSC and we compared the results with its CRISPR corrected isogenic control. This model is derived from a patient and therefore is more suitable to study the endogenous effect of RET

C634Y (

Figure 3). Interestingly, we found the same inhibitory effect than with the overexpression of the mutation in WT background iPSCs. It indicates that our RET

C634Y lentiviral overexpression model is relevant to mimic the

in vivo effect of the RET mutation and therefore it could serve as a drug screening model. There are several RET inhibitors available in the market and under evaluation for clinical treatment such as Pralsetinib, a RET specific inhibitor currently tested for NSCLC treatment [

44,

45,

46]. It would be interesting to evaluate the effect of this drug in our hematopoietic differentiation model.

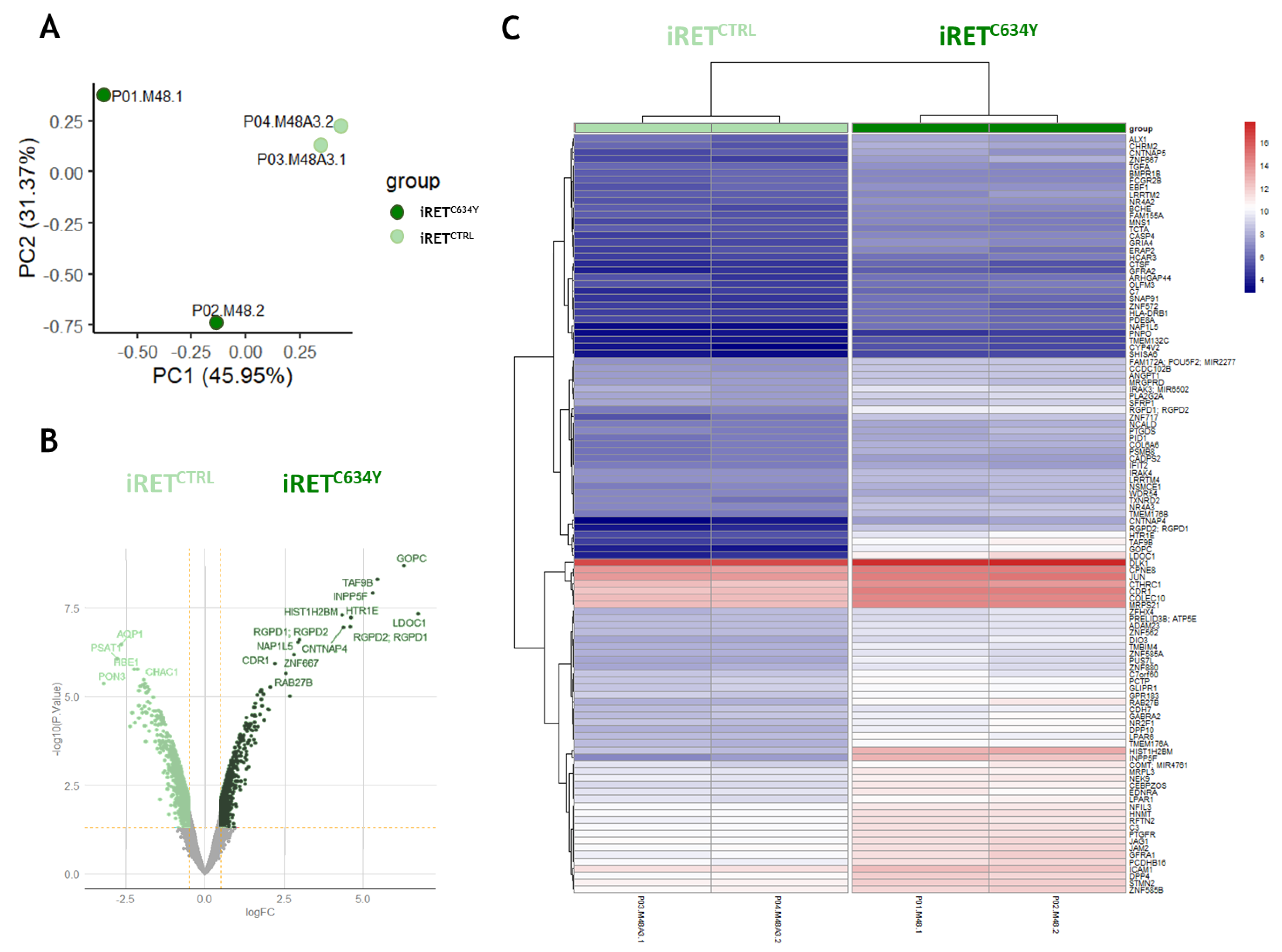

To get a better understanding of RET activation effect on iPSC derived hematopoiesis, we performed transcriptomic analysis on iRET

C634Y and its isogenic counterpart iRET

CTRL in hematopoietic cells collected at day +13 of differentiation. The data reveals a specific activated expression profile of iRET

C634Y compared to iRET

CTRL (

Figure 4). Genes up regulated in iRET

C64Y are functionally enriched for MAPK, immune system, and hematopoiesis regulation gene sets. Inside this network, we identified some relevant hematopoietic regulatory genes up regulated by RET mutation (

Figure 5). DLK1 and NR4A3 are both known to be involved in the restriction of HSC proliferation and emerging hematopoiesis [

33,

34]. C/EBPα is downstream of NR4A3 and its conditional knockout in adult HSC leads to the expansion of functional HSCs [

47]. Moreover, upon its activation by the MAPK, JNK1 can act as a positive regulator of C/EBPα [

48]. Implication of the MAPK pathway was also hinted by western blot analysis showing an increase of pMAPK1/2 protein quantity during iRET

C634Y hematopoietic differentiation. qRT-PCR performed at both iPSC stage and at day-13 of differentiation show a correlation between RET activation and the overexpression of DLK1, NR4A3, GFRA1, JUN, CEPBA and DLK1. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of RET activation on HSC during hematopoietic differentiation could be mediated by MAPK/JNK and the transcriptional regulation of HSC inhibitory genes. Conditional KO of these candidate genes with siRNA during iPSC derived hematopoiesis could provide useful information on their role and on the mechanism of RET HSC inhibition.

Activation of the RET pathway by GDNF promotes the growth and survival of f UCB-derived HSCs [

24]. This activation induces an anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory response while reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in UCB HSCs.

In vivo, the RET signal is likely provided by GDNF/GFRα1 from the bone marrow environment, playing a crucial role in maintaining HSC potential. However, our study reveals an inhibitory effect of RET activation during iPSC-derived hematopoiesis. Specifically, we observed a decrease in the number of HSC-positive cells and their clonogenic potential in various models of RET activation. It is interesting that the same regulatory pathway can exhibit opposing effects depending on the timing of its activation. In the context of hematopoietic differentiation, premature activation of a proliferative signal may impede the emergence of HSCs. Moreover, it is essential to verify the findings from other models specifically during iPSC differentiation, as outcomes may differ. iPSC-derived hematopoiesis closely resembles embryonic hematopoiesis and differs from what is known about adult hematopoiesis. This consideration is crucial for the development and optimization of new strategies for iPSC differentiation.

We demonstrate with this work a model of RET increasing induction within different iPS cell lines. RET is known to be mutated and overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2A) [

32]. These iPSCs could be used to generate cancerous tissues, get better understanding of the mechanisms activated by RET and could be used as potential target discovery tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M., J.I., C.D., A.T.; methodology, P.M., J.I., C.D., A.T.; software, C.D.; validation, P.M., A.B-G, A.T.; formal analysis, P.M., C.D.; investigation, P.M., J.I.; resources, T.L., D.C., P.H.; data curation, P.M., J.I., A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M. J.I., A.T.; writing—review and editing, P.M, J.I., C.D., A.T.; visualization, P.M., A.T.; supervision, P.M., A.T.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, A.B-G., A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

RET activation with GDNF/GFRα1 has no effect on HSC potential at D13 of hematopoietic differentiation. (A) Morphology of non-adherent, round, hematopoietic cells derived from PB33-WT iPSC at D13 of differentiation (B) Microscope pictures (magnification 10x) of May-Grunwald and Giemsa (MGG) staining at day 13 of floating hematopoietic cells differentiated from PB33-WT. (C) Microscope picture of CFU assay at D14 of culture displaying a Colony derived from CFU-GM (white) and colony derived from BFU-E (Red) (D-G) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (D), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (E), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (F), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (G) at day 13 of hematopoietic differentiation with or without GDNF for two different iPSC cell lines (PB33-WT and PB68-WT). (H) CFC assays for PB33-WT and PB68-WT with or without GDNF showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells (Means and SD are represented) and the type of colonies (I). All experiments have been performed six times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant.

Figure 1.

RET activation with GDNF/GFRα1 has no effect on HSC potential at D13 of hematopoietic differentiation. (A) Morphology of non-adherent, round, hematopoietic cells derived from PB33-WT iPSC at D13 of differentiation (B) Microscope pictures (magnification 10x) of May-Grunwald and Giemsa (MGG) staining at day 13 of floating hematopoietic cells differentiated from PB33-WT. (C) Microscope picture of CFU assay at D14 of culture displaying a Colony derived from CFU-GM (white) and colony derived from BFU-E (Red) (D-G) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (D), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (E), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (F), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (G) at day 13 of hematopoietic differentiation with or without GDNF for two different iPSC cell lines (PB33-WT and PB68-WT). (H) CFC assays for PB33-WT and PB68-WT with or without GDNF showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells (Means and SD are represented) and the type of colonies (I). All experiments have been performed six times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of RETWT and RETC634Y during iPSCs-derived hematopoiesis decreases the percentage of HSCs and their capability. (A-D) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (A), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (B), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (C), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (D) at day 13 of hematopoietic differentiation for WT iPSC cell lines (PB33-WT and PB68-WT), with RETWT overexpression with or without GDNF or with RETC634Y overexpression. (E) CFC assays for PB33-WT/PB33-RETWT/PB33-RETC34Y and for PB68-WT/PB68-RETWT/PB68-RETC634Y showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells and the type of colonies (F) (Means and SD are represented). All experiments have been performed six times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of RETWT and RETC634Y during iPSCs-derived hematopoiesis decreases the percentage of HSCs and their capability. (A-D) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (A), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (B), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (C), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (D) at day 13 of hematopoietic differentiation for WT iPSC cell lines (PB33-WT and PB68-WT), with RETWT overexpression with or without GDNF or with RETC634Y overexpression. (E) CFC assays for PB33-WT/PB33-RETWT/PB33-RETC34Y and for PB68-WT/PB68-RETWT/PB68-RETC634Y showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells and the type of colonies (F) (Means and SD are represented). All experiments have been performed six times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 3.

RETC634Y mutation from a patient has an inhibitory effect of the HSCs potential correlated with MAPK1/2 activity. (A-D) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (A), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (B), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (C), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (D) at day +13 of hematopoietic differentiation for RETC634Y mutated iPSC (iRETC634Y) and its isogenic CRISPR control (iRETCTRL). (E) CFC assays showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells. (F) Western blot showing iRETC634Y and iRETCTRL at iPSC stage or after 13 days of hematopoietic differentiation. (G-H) Relative change of the phospho-p44/42 MAPK (G) and pRET/RET (H) quantity during hematopoietic differentiation. All experiments have been performed three times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **.

Figure 3.

RETC634Y mutation from a patient has an inhibitory effect of the HSCs potential correlated with MAPK1/2 activity. (A-D) FACS phenotypic panel gated on live cells. Proportion of CD34 total (A), primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (CD34+/CD38-) (B), HSCs (CD34+CD38- CD49f+) (C), or hematopoietic cells (CD45+) (D) at day +13 of hematopoietic differentiation for RETC634Y mutated iPSC (iRETC634Y) and its isogenic CRISPR control (iRETCTRL). (E) CFC assays showing the number of colonies per 5000 cells. (F) Western blot showing iRETC634Y and iRETCTRL at iPSC stage or after 13 days of hematopoietic differentiation. (G-H) Relative change of the phospho-p44/42 MAPK (G) and pRET/RET (H) quantity during hematopoietic differentiation. All experiments have been performed three times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **.

Figure 4.

iRETC634Y mutated hematopoietic cells derived from iPSCs harbored a specific activated expression profile as compared to iRETCTRL (A) Whole transcriptomic principal component analysis stratified on group of samples. (B) Volcano plot of differential expressed between iRETC634Y mutated cells and its isogenic CRISPR correction iRETCTRL. (C) Expression heatmap of 109 genes up regulated in iRETC634Y cells as compared to its CRISPR corrected control iRETCTRL.

Figure 4.

iRETC634Y mutated hematopoietic cells derived from iPSCs harbored a specific activated expression profile as compared to iRETCTRL (A) Whole transcriptomic principal component analysis stratified on group of samples. (B) Volcano plot of differential expressed between iRETC634Y mutated cells and its isogenic CRISPR correction iRETCTRL. (C) Expression heatmap of 109 genes up regulated in iRETC634Y cells as compared to its CRISPR corrected control iRETCTRL.

Figure 5.

MAPK cascade overlaps immune system and hemopoiesis network induced by RETC634Y mutation in hematopoietic cells derived from iPSCs: (A) Bar plot of functional enrichment performed on GO-BP database with 109 coding genes up-regulated by RET mutation. (B) Venn diagram for overlapping of MAPK, immune system, hemopoiesis gene sets up regulated by RETC634Y mutation. (C) MAPK and hematopoiesis regulation molecular network activated by RET mutation. (D) Expression of RET regulated candidate genes quantified by qRT-PCR in iPSCs-derived hematopoietic cells after 13 days of differentiation. Experiments have been performed three times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 5.

MAPK cascade overlaps immune system and hemopoiesis network induced by RETC634Y mutation in hematopoietic cells derived from iPSCs: (A) Bar plot of functional enrichment performed on GO-BP database with 109 coding genes up-regulated by RET mutation. (B) Venn diagram for overlapping of MAPK, immune system, hemopoiesis gene sets up regulated by RETC634Y mutation. (C) MAPK and hematopoiesis regulation molecular network activated by RET mutation. (D) Expression of RET regulated candidate genes quantified by qRT-PCR in iPSCs-derived hematopoietic cells after 13 days of differentiation. Experiments have been performed three times. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Table 1.

Antibody fluorophores and references.

Table 1.

Antibody fluorophores and references.

| Antibody |

Fluorophore |

Reference |

| CD34 |

APC |

BD 555824 |

| CD38 |

PE-Cy7 |

BD 560677 |

| CD45 |

FITC |

BD 555482 |

| CD49f |

PE |

BD 555736 |

| CD201 |

BV421 |

BD 743552 |