1. Introduction

Influenza is a highly contagious viral disease with global circulation: the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, at least before the COVID-19 pandemic, epidemics of seasonal influenza interest about 5–15% of the population worldwide annually, causing up to 5 million cases of severe illness and 650,000 respiratory deaths [

1]. Symptoms range from mild to severe and even death: hospitalization and death occur most frequently among high-risk groups such as older adults and individuals with underlying chronic health conditions, even comorbidities [

2].

In particular, health professionals have an increased risk both to acquire and to spread influenza as vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) to their colleagues and, especially, to vulnerable or immunocompromised patients. In fact, medical visits and hospitalizations associated to influenza facilitate the transmission of the infection to healthcare providers who represent an important target group for vaccination because of their role in potential for nosocomial influenza-like illness (NILI) on the one hand and increased sick leaves on the other hand [

3]. Likewise, healthcare providers, in whom infection is incubating or who are working despite infection, may infect hospitalized patients and further perpetuate the transmission to frail individuals. The vaccination recommendations of health professionals, as well as the general population, differ from country to country. Furthermore, coverage rates vary widely a lot over the world, making healthcare providers vulnerable to disease and so settings to outbreaks [

4]. Nevertheless, despite recommendation for immunization of this work-category in most of Western Countries, inadequate flu vaccine uptake is reported during the last decade in the European area [

5]. The failure to protect properly all individuals at increased risk of influenza-related complications including death has led to the recommendation to immunize health care workers as an additional means of reducing the potential for transmission of influenza to vulnerable people. However, influenza outbreaks continue to challenge healthcare facilities and vaccinated professionals act as a barrier against the spread of infections and maintain essential healthcare delivery during outbreaks [

6]. Indeed, the vaccination attitudes among health professionals is even more valuable, given their role as most trusted sources of vaccine-related information, still in effectively addressing issues of concern, mistrust and misconceptions about vaccinations in the general population [

7,

8]. In Italy, within the framework of the National Immunization Prevention Plans (PNPV) over the years [

9], the Ministry of Health (MoH) has issued specific recommendations to health professionals for several types of vaccination as essential for the prevention and control of infection-related diseases: hepatitis B, influenza, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella and tuberculosis [

6,

10,

11]. In Italy, there is no national registry for vaccinations and, although the national recommendations recognize health care providers as high-priority group for influenza immunization, the success of vaccination programs in this subgroup appears still unclear, reaching suboptimal values, as coverage data are not readily accessible and only limited to local communities or a few hospitals [

10,

12].

The purpose of this study is to provide nationwide estimates on influenza vaccination uptake among health professionals by using the 2014-2018 data from the Italian Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) PASSI (Progressi delle Aziende Sanitarie per la Salute in Italia - Progresses in ASSessing population health in Italy). Further, we investigated the association between demographic, medical, and socio-economic factors, and the adherence to immunization programs for influenza among health care providers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Data Source and Samples

Committed by the National Centre for Disease Prevention and Control of the Italian MoH in 2007, PASSI is an ongoing nationwide surveillance system and the National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS) is in charge of its central coordination [

13].

2.1.1. Study Design and Data Source

Briefly, PASSI collects data on many of the behaviours and medical conditions that could influence the health status of people residing in Italy, as per the domains and indicators encompassed in the National Prevention Plan [

14]. The target population consists of all people aged 18 to 69 years residing in the area of Local Health Unit (LHU) participating in PASSI. The eligible population comprises residents who have a telephone number available and who are capable of being interviewed. In each LHU, a random sample is drawn monthly from the LHU’s enrolment list of residents. The list is then stratified according to sex and age (18–34, 35–49, and 50–69) proportionally to the size of the respective stratum in the general population. Specially trained personnel from the public health departments of each LHU administer telephone interviews through a standardized questionnaire, gathering information on physical and mental health, behavior-related risk factors, and socio-demographic characteristics. The LHU data are merged, weighted and analyzed to obtain national and regional estimates. The sample is representative of the adult population residing in Italy. A detailed description of the validated survey design and random sampling procedures is available elsewhere [

15,

16].

2.1.2. Sampling Procedures

The sample is representative of the general population as indicated above. In the period 2014-2018 data were collected from 154,187 working-age adults. The response rate was 81%; in 2018, 110 out of 121 LHUs from all Regions and Autonomous Provinces except one, participated in the surveillance, covering more than 90% of the adult population living in Italy.

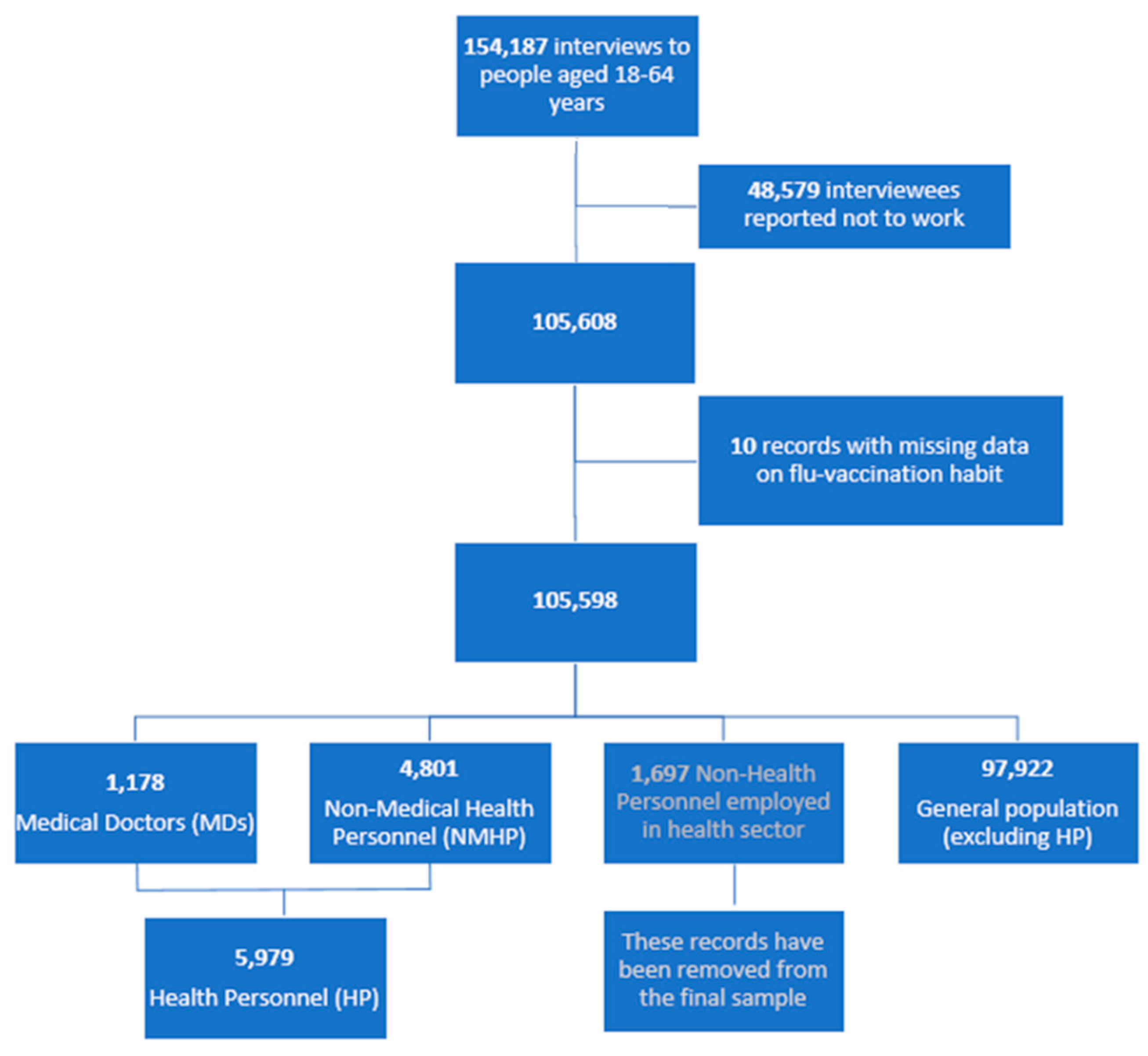

As

Figure 1 shows, we selected 105,608 out of 154,187 records of total participants who reported to be employed at the time of interview. From this number, we removed 10 records because of missing information on flu-vaccination. Aggregating and recoding data from two variables (“work sector” and “type of job”), three groups are identified: 5,979 individuals working as Health Personnel (HP), 1,697 personnel employed in health sector without health duty and 97,922 workers in other sectors. Among HP, 1,178 were Medical Doctors (MDs) and 4,801 were Non-Medical Health Personnel (NMHP), thus including nursing, midwifery and other health-related professions. In this analysis, we did not consider people who, although working in health sector, did not practice any health profession (

Figure 1).

2.2. Outcome and Covariate Variables

The outcome is the adherence to seasonal influenza vaccination, obtained categorizing the answers to the question “In the past 12 months, have you had seasonal flu vaccination?” into a dichotomous variable: yes vs no (including “I don’t know/I don’t remember”).

The covariate variables are socio-demographic characteristics and health-related conditions. The formers include the following: gender, age (18–34; 35–49; 50–64), economic difficulties in making ends meet by the available financial resources (many or some; not at all), educational attainment (low as none or elementary or middle school; high as high school or university), macro-area of residence (North; Centre; South of Italy), urbanization degree, marital status (married yes

vs no), and nationality (Italian

vs others). Specifically, about the urbanization degree, ISTAT disseminates a classification of Italian municipalities [

17] based on a subdivision of the territory into 1 km2 cells, considering both the criteria of geographic contiguity and minimum population threshold. The resulting areas are matched with the administrative boundaries of the municipalities and grouped into three classes: 1) high density municipalities—at least 50% of the population lives in densely populated areas; 2) intermediate density municipalities—less than 50% of the population lives in rural areas and less than 50% in densely populated areas; 3) low population density municipalities—more than 50% of the population falls into rural areas.

The health-related conditions include: presence of at least one chronic disease, obesity, tobacco smoking, and self-perceived health status. The first variable is defined as having ever received from a physician a diagnosis of a condition among the following: diabetes, renal insufficiency, asthma, chronic respiratory disease, chronic liver disease, cancer, coronary heart disease or other cardiovascular diseases, or cerebral stroke or brain ischemia.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Prevalence of adherence to seasonal flu vaccination was calculated stratified by type of health care employee, Medical Doctors (MDs) and Non-Medical Health Personnel (NMHP), and for general population, excluding health professionals (NHP). Also, results was provided according to all covariate variables mentioned above.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between vaccination adherence outcome and socio-demographic and medical factors such as age, gender, educational level, economic difficulties, macro-area of residence, presence of at least one chronic diseases. Odds ratio (OR) estimates, crude and adjusted, 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were reported. We used univariate logistic analysis by subgroup to test the association of socio-demographic characteristics and health-related conditions with the adherence to the seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns. We then conducted a multivariate regression logistic model by subgroup that excluded variables with p>0.20 in the univariate analysis.

STATA version 17.0 was used for all. Throughout the paper, p < 0.05 is regarded as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Health Conditions

Table 1 shows the description of the three professional category samples (MDs, NMHP, and NHP) by socio-demographic characteristics and health conditions.

Among NMHP, the female gender was much more represented (73.9%) than in the other two groups: MDs (47.1%) and NHP (42.7%).

As categorization per age, almost half of MDs belonged to the 50-64 group. They reported less economic difficulties and, holding at least a university degree, were the category with a higher education level. In others, 89.9% of NMHP vs 71.5% of NHP had a university or high school diploma.

According to the urbanization degree, MDs seemed to live in high population density municipalities (48.9%) more than NMHP (35.1%) and NHP (33.7%). By the way, the most of respondents lived in municipalities with an intermediate urbanization degree.

Smoking habit showed a lower prevalence among MDs (16.4%) than in other categories (25.4% of NMHP and 28.7% NHP).

An obesity condition was more frequent in the general population (9.4%) than among NMHP (7.9%) and even lower in MDs (6.4%).

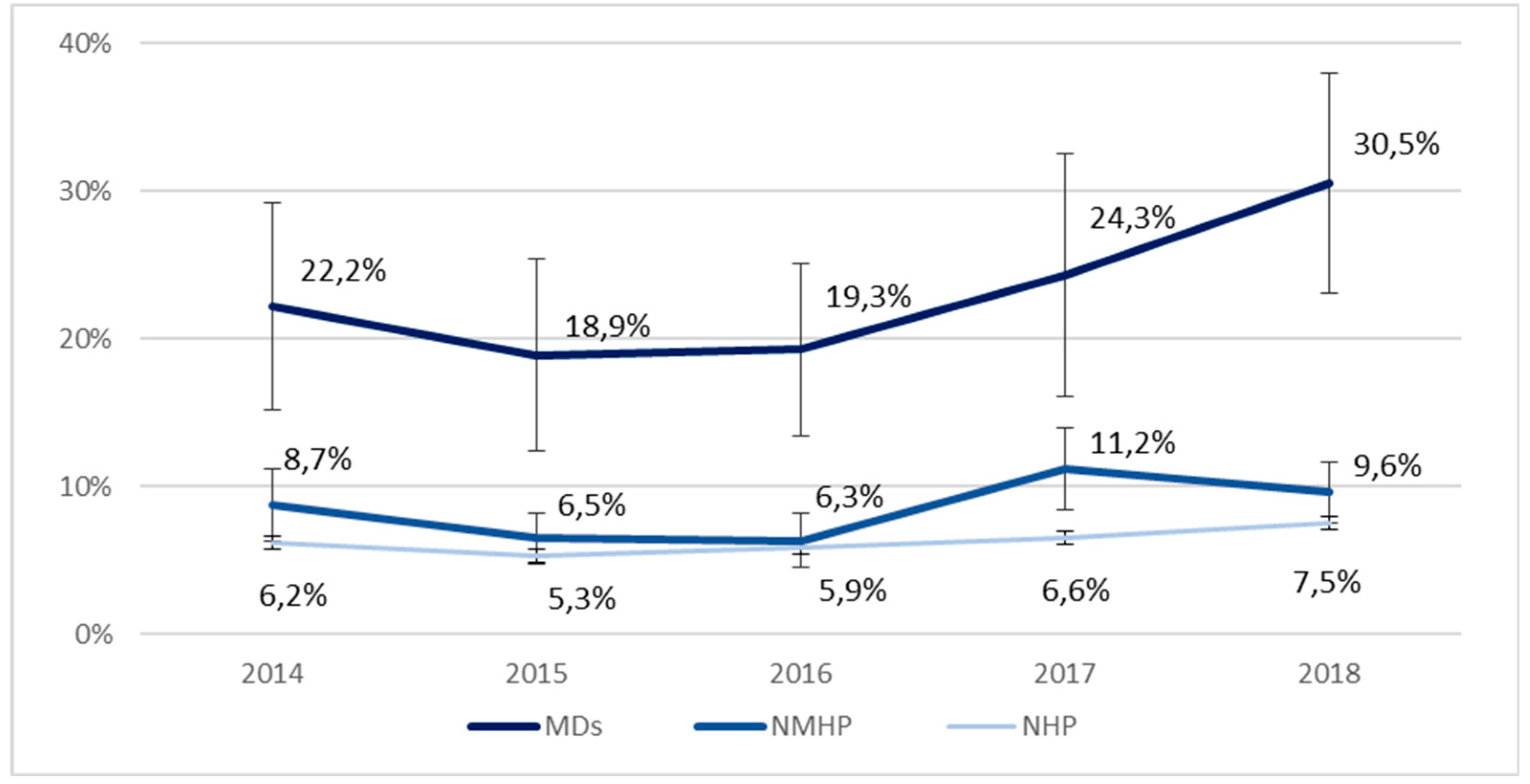

From 2014 to 2018, we detected an overall increase of the adherence to the seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns in the three groups, with a rise from 2016. Such this increase is even more evident among MDs (from 22.2% in 2014 to 30.5% in 2018) and, although it does not reach statistical significance due to small sample size, is by over 25% in five years. The trend is less evident, but significant also in the NHP group (

Figure 2).

3.2. Adherence to the Flu Vaccination Campaign by Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Health Conditions

In Italy, in the period 2014-2018, the adherence by MDs to the seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns was significantly higher (22.8%) than that observed among NMHP (8.5%) who, in turn, reached a higher adherence than that recorded in general population (6.3%) (

Table 2a).

Adherence was lower in women in comparison to men: respectively, 21.3%

vs 24.1% (MDs) and 7.8%

vs 10.2% (NMHP). An increasing gradient by age was retrieved over the three categories, even higher among MDs and especially in older physicians (28.4%

vs 9.9% in doctors aged >35 years). Differences between age groups are smaller, but still evident in NMHP (13.9%

vs 4.4%) and NHP (3.4%

vs 10.6%). A gap in favor of MDs was also found in comparison with socioeconomically advantaged individuals, with a high cultural level and without economic difficulties, in the other two groups. MDs adherence to vaccination by geographical area was higher in the North (25.7%) and in the South (22.7%), compared to the Centre (17.9%). Among NMHP and NHP, a higher adherence was observed in the South (9.6% and 6.9%, respectively) than in the North (7.9% and 5.7%). Additionally, MDs living in municipalities with a high urbanization degree seemed to be less vaccinated, whereas any significant differences are appreciated in the other two categories.

Table 2a includes also findings by marital status and nationality: the first pattern seemed to be enhancing the vaccination adherence, mostly in MDs and slightly occurring in NMHP and NHP, and as per the second variable just a discrepancy is retrieved in Italian

vs other NMHP.

In all the three groups, there was a clearly higher adherence to vaccination in people with almost one chronic disease (

vs none): MDs 36.3%

vs 20.8%; NMHP 13.9%

vs 7.5%; NHP 17.6%

vs 4.4%. Likewise, a similar occurrence was observed in whom reported an obesity condition; on the contrary, tobacco smoking resulted not to be associated to the adherence levels in HP. A quite strong finding related to the self-perceived health status: independently from the grouping category, who perceived a lower health revealed to vaccinate more against seasonal influenza (

Table 2b).

Table 3 reports the multivariate analysis results which, as indicated in the Methods paragraph, excluded covariates with p>0.20 from univariate analysis. It confirmed that, controlling by the socio-demographic characteristics and risk factors, MDs were much more vaccinated than NMHP and general population.

In the multivariate analysis, adherence to the seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns by MDs was significantly associated with age (AdjOR=3.14 in 50-64

vs under 35 years), geographic area (AdjOR= 0.64 Central

vs Northern Italy), and having at least one chronic disease (AdjOR=1.85 almost one

vs none). Amongst NMHP, adherence was instead associated with gender (AdjOR=0.74 in women

vs men), age (AdjOR=3.30 in 50-64 NMHP

vs under 35 years) as well as having at least one chronic disease (AdjOR=1.73 at least one

vs none). Among NHP, adherence to vaccination was associated with male gender, older age, residing in Central and Southern Italy, living in intermediate and low population density municipalities and having at least one chronic disease (AdjOR=3.49 at least one, compared to none). Smokers seemed to be significantly less vaccinated, as well as people who perceived a good health status (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Critical Reading of the Results

This study aimed to describe and compare influenza vaccine uptake and its prognostic factors among different categories of HP

vs NHP in Italy by using 2014-2018 PASSI data. The main findings from this focus on flu vaccination concern higher compliance values among health professionals as a whole when compared to people who do not practice any health profession. Indeed, in the comparison between MDs

vs NMHP, physicians are three times as likely to vaccinate against seasonal influenza. This difference is even confirmed in the three population categories under study across the different age groups: from lower values in younger people, aged 18-34, to higher figures among older people, 50-64yy. This occurrence is also known as “

vaccine confidence gap” that is retrieved to increase over time across many EU member states [

18]. According to PASSI data, also the increasing influenza vaccination uptake over time is verified especially among doctors.

4.1.1. Literature Appraisal on Influenza Vaccination Uptake and its Main Determinants

According to studies included in

Table S1 reporting a scoping overview on seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among health professionals in Italy, 1990-2022, also including systematic reviews on the topic, the adherence rate is quite low. In any study, in fact, coverage data are near 75%. The uptake ranges from under 10% to around 20% overall, and anything seems to be changed since 1990. Lower vaccine acceptance levels are reported in females and nurses; this figure could even be due to a collinearity effect.

The main determinants of vaccine acceptance among HP have been largely investigated and include a wide spectrum of aspects, ranging from desire for self-protection and to protect family rather than absolute disease risk or desire to protect patients.

Individual motivation as self- and family protection would result to be the main drivers for seasonal flu vaccination among HP, mostly associated with a concern about age and comorbidities. As expected, the vaccine uptake is also associated with trust in vaccines and recommending the flu vaccination to patients.

On the other hand, the barriers to vaccination identified leading to a lower influenza vaccine confidence among HP were associated with several issues, such as low risk perception, denial of the social benefit of influenza vaccination, low social pressure, lack of perceived behavioural control, negative attitude toward vaccines, not having been previously vaccinated against influenza or not having previously had influenza, lack of adequate influenza-specific knowledge, lack of access to vaccination facilities, and socio-demographic variables. The topic of influenza vaccination among HP is then much challenging, full of ethical issues [

5,

19].

As recalled in the Introduction, increasing influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare workers would mean also reducing the risk of NILI in patients hospitalized in acute hospitals [

3].

4.1.2. Interventions and Application of Proven Effective Policies

Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effectiveness of interventions for improving vaccine uptake among HP found that combined strategies were more effective than isolate approaches. High quality studies on specific motivations leading to lower vaccine confidence would help policy-makers and stakeholders to shape evidence-based initiatives and programs to improve vaccination coverage and the control of influenza through the correct application of guidelines on prevention [

4,

5]. On the other hand, studies that evaluated the effectiveness of multicomponent interventions to increase vaccination coverage found only minimal to moderate increases in uptake levels [

12]. For example, a group of different studies retrieved a good effectiveness from on-site vaccination sessions [

20,

21].

Currently, according to the law that regulates safety in the workplace, health surveillance for biological agents and therefore relative vaccination refers to the specific risk factors, whether they are potential or deliberate, and there is no specific reference on flu vaccination. However, this law also encourages information and awareness-raising activities on workers in the vaccination field.

Nevertheless, both the PNPV in force [

9] and the Recommendations for the prevention and control of influenza 2021-21 have identified health professionals as target groups for influenza vaccination. The interventions that make it “complex and traceable” flu vaccination refusal increase adherence to this type of vaccination. The results show that launched vaccination campaigns have not contributed to increase the rate of adherence by health practitioners [

19].

In other countries than Italy, flu vaccination is mandatory for health professionals: it is the case of the United States, where mandatory influenza vaccination of HP was introduced more than a decade ago with excellent results [

7]. Thus, mandatory policies are currently under debate in several countries. From the findings of a survey among the Vaccination Service employees in the Apulia Region, three respondents out of four stated that mandatory vaccination should be retained [

22]. Basing on the results from reviews also including meta-regression analysis about evaluating interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccination coverage in HP, mandatory vaccination results to be the most effective intervention component, followed by “soft” mandates such as declination statements, increased awareness and increased access. Whereas for incentives the difference was not significant and for education no effect was observed, such evidence claims that effective alternatives to mandatory HP influenza vaccination do exist, and need to be further explored according to context-related specificity [

23].

Many HP get informed from TV or other media, some studies suggest an expressed need for more education or counselling. Still, despite provided educational programs generate an improvement in vaccination adherence by involved HP, the increased coverage results to be in any way lower than recommended to reduce influenza spread in hospital contexts. Thus, specific training alone may play a role to improving influenza vaccination adherence, but an integration with broader public health measures is envisaged as well [

24].

Other kinds of intervention concern participative strategies such as forum theater that does represent an innovative solution to increasing HP awareness of the importance of flu vaccination and could positively impact their adherence to vaccination recommendations. The forum theater methodology can also be a meaningful teaching tool to health professionals for their learning about and changing attitudes toward other clinic and public health issues [

25].

4.1.3. Impact of Pandemics

The COVID-19 epidemic may have a significant occurrence in matter of VPDs. For instance, in the 2020-2021 flu season a pretty higher prevalence of vaccinated HP was observed in Italy [

26] or altruistic motivations such as protecting general population and safety of patients, usually considered less important as vaccination driver, were much higher accounted during the COVID pandemic.

Indeed, it has even represented a watershed also in matter of mandating influenza vaccination to HP in Italy; in fact, the Law Decree of 01 April 2021 establishes mandatory vaccination against COVID for healthcare workers. Although mandatory is an undesirable modality for operators in the health area, those measures, which are necessary in emergency contexts, can increase awareness in the category.

Even more after the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among HP is much highly related to the key role that they play in representing a behavioural model to their patients, having such an enormous potential to contribute to better vaccine confidence among the general population and its specific subgroups. Considered one of the most trusted sources of information around vaccination, HP are crucial in motivating individuals to get vaccinated. The Vaccine Confidence Project found vaccine confidence among HP across all 27 EU member states to be universally high and stable between 2018 and 2020, with a large perception increase particularly towards the seasonal influenza vaccine [

18]. If many of these 2020 gains have since been reversed, in Italy in 2022 the confidence level towards flu vaccine achieved 100% on safety, relevance, effectiveness, and 97% on compatibility with beliefs. Furthermore, about the likelihood to recommend the flu vaccine 98% would do it to patients and 88% to pregnant women [

27]. In turn, basing on data from the Italian BRFSS PASSI d’Argento (on elderly population), four out of five older individuals referred to have been advised by the general practitioner to vaccinate against flu: this figure remains high as before the COVID-19 pandemic [

28].

4.2. Strenghts and Limitations

Our study presents some strengths and limitations as well.

This research has major strengths relating to the fact that it is the first and unique surveys at a national scale with this focus on health professionals. PASSI is an ongoing surveillance system and can then monitor how the influenza vaccination uptake and prognostic factors among health professionals in Italy change over time, even under emergency occurrences such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

29]. PASSI relies on large sample size and proven reliability and validity because data aggregated over time give good solidity to the results but it does not refer to any European network, thus comparisons with the same data from other Countries are not possible so far.

The limitations are mainly attributable to the characteristics of PASSI data collection that, as health interview survey, is based on self-reporting during a telephone interview. Therefore, except for the main demographic characteristics such as sex, age, residence, data cannot be validated with objective measures, and the information released can be somehow biased, generating underestimated or overestimated percentages [

30]. Vaccination uptake may be affected by bias for social desirability, and misclassification or recall bias could occur on vaccine compliance, as referring to unusual and infrequent behaviour. Self-reported data show in any way robust consistency and sensitivity [

31], even because the PASSI interviewers are specially trained healthcare workers from the LHU Prevention Departments and, over the years, a capillary surveillance network has been growing on local territory [

15]. As described in the Methods, the PASSI design and sampling procedures ensure both low nonresponse rates and much broader coverage than other similar surveys (e.g., the American BRFSS), and the final response rate is goodly assessed [

16].

Furthermore, specifically applying to the present study, although the national pool is representative of the general population living in Italy, the health professionals’ sub-sample is however reconstructed retrospectively [

32].

5. Conclusions

It is crucial to tackle influenza vaccine hesitancy in health professionals because, despite such observed increases, vaccination uptake is still low, especially among the younger groups. Identifying effective strategies able to significantly increase vaccine coverage is needed in order to decrease the risk of nosocomial infections, prevent transmission to patients, and reduce indirect costs related to HP absenteeism due to illness. Even more under pandemic scenarios, given also the role of professionals as public health promoters in the society, these figures represent key information to address effective strategies in matter of VPD prevention.

Through the extensive “tool” of prevention in the workplace, joint efforts with occupational medicine are needed to develop a culture on the protection of public health and patients. The introduction of compulsion would be more to be understood as a requirement of safe work for the worker and patients, than as a coercive action. Therefore, especially designed educational programs should be set up to make health professionals interiorize the value and worth of voluntary compared to mandatory vaccination, as well why high vaccination rates do not have to depend on compulsion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Study on influenza vaccination uptake among health professionals in Italy, 1990-2022; References studies in Table S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M., R.G., E.D.A. and M.M.; methodology, V.M., R.G., B.C. and M.M.; software, V.M.; validation, V.M. and R.G.; formal analysis, V.M. and R.G.; investigation, V.P., B.C., E.D.A. and D.D.F.; resources, V.M. and M.M.; data curation, V.M. and R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P., E.D.A. and D.D.F.; writing—review and editing, R.G., V.P and B.C.; visualization, V.M., R.G. and V.P.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (the protocol number of the final opinion is CE-ISS 06/158—8 March 2007).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, e.g., privacy or ethical.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution and support of the whole PASSI Network from Local Health Unit Prevention Departments, including the interviewers, coordinators, and reference persons at local and regional levels. We also thank the many interviewees who generously spent their time to join in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- 2. Siriwardena AN, Gwini SM, Coupland CA. Influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination and risk of acute myocardial infarction: matched case-control study. CMAJ, 2010; 182, 15, 1617–1623. [CrossRef]

- Amodio, E.; Restivo, V.; Firenze, A.; Mammina, C.; Tramuto, F.; Vitale, F. Can influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare workers influence the risk of nosocomial influenza-like illness in hospitalized patients? J Hosp Infect. 2014, 86(3), 182–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squeri, R.; Di Pietro, A.; La Fauci, V.; Genovese, C. Healthcare workers’ vaccination at European and Italian level: a narrative review. Acta Biomed, 2019; 13, 90(9-S), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, G.; Toletone, A.; Sticchi, L.; Orsi, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Durando, P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: A comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018, 14(3), 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchitta, M.; Basile, G.; Lopalco, P.L.; Agodi, A. Vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccination among Italian healthcare workers: a review of current literature. Future Microbiol. 2019, 14, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Theodoridou, K.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Theodoridou, M. Vaccination of healthcare workers: is mandatory vaccination needed? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019, 18(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Scala, C.; Toletone, A.; Debarbieri, N.; Perria, M.; D’Amico, B.; Montecucco, A.; Martini, M.; Dini, G.; Durando, P. Susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccination adherence among healthcare workers in Italy: A cross-sectional survey at a regional acute-care university hospital and a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017, 13(2), 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. National Immunization Prevention Plans (PNPV) 2017-2019. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/documentazione/p6_2_2_1.jsp?id=2571 (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Prato, R.; Tafuri, S.; Fortunato, F.; Martinelli, D. Vaccination in healthcare workers: an Italian perspective. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010, 9(3), 277–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietro, A.; Visalli, G.; Antonuccio, G.M.; Facciolà, A. Today’s vaccination policies in Italy: The National Plan for Vaccine Prevention 2017-2019 and the Law 119/2017 on the mandatory vaccinations. Ann Ig. 2019, 31(2 Supple1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassano, M.; Barbara, A.; Grossi, A.; Poscia, A.; Cimini, D.; Spadea, A.; Zaffina, S.; Villari, P.; Ricciardi, W.; Laurenti, P.; Boccia, S. La vaccinazione negli operatori sanitari in Italia: una revisione narrativa diletteratura [Vaccination among healthcare workers in Italy: a narrative review]. Ig Sanita Pubbl. 2019; 75, 2, 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers of 3 March 2017. Identification of surveillance systems and registers of mortality, cancer and other diseases. (17A03142) (OJ General Series No.109 of 12-05-2017).

- Ministero della Salute. National Prevention Plan (PNP) 2020-2025. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/prevenzione/dettaglioContenutiPrevenzione.jsp?id=5772&area=prevenzione&menu=vuoto#:~:text=Adottato%20il%206%20agosto%202020%20con%20Intesa%20in,vita%2C%20nei%20luoghi%20in%20cui%20vive%20e%20lavora (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Baldissera, S.; Campostrini, S.; Binkin, N.; et al. , Features and initial assessment of the Italian behavioral risk factor surveillance system (PASSI), 2007-2008, Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8(1), A24. [Google Scholar]

- Baldissera, S.; Ferrante, G.; Quarchioni, E.; Minardi, V.; Possenti, V.; Carrozzi, G.; et al. , Field substitution of nonresponders can maintain sample size and structure without altering survey estimates-the experience of the Italian behavioral risk factors surveillance system (PASSI), Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24(4), 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principali Statistiche Geografiche Sui Comuni. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/156224 (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- de Figueiredo, A.; Eagan, R.L.; Hendrickx, G. ; E. Karafillakis, van Damme, P. & Larson, H.J. State of Vaccine Confidence in the European Union, 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guillari, A.; Polito, F.; Pucciarelli, G.; Serra, N.; Gargiulo, G.; Esposito, M.R.; Botti, S.; Rea, T.; Simeone, S. Influenza vaccination and healthcare workers: barriers and predisposing factors. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92(S2), e2021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.P.; Tafuri, S.; Spinelli, G.; Carlucci, M.; Migliore, G.; Calabrese, G.; Daleno, A.; Melpignano, L.; Vimercati, L.; Stefanizzi, P. Two years of on-site influenza vaccination strategy in an Italian university hospital: main results and lessons learned. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2022; 18, 1993039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimercati, L.; Bianchi, F.P.; Mansi, F.; et al. Influenza vaccination in health-care workers: an evaluation of an on-site vaccination strategy to increase vaccination uptake in health professionals of a South Italy Hospital. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019, 12), 2927–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafuri, S.S.; Martinelli, D.D.; Caputi, G.G.; Arbore, A.A.; Germinario, C.C.; Prato, R.R. Italian healthcare workers’ views on mandatory vaccination. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytras, T.; Kopsachilis, F.; Mouratidou, E.; Papamichail, D.; Bonovas, S. Interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccine coverage in healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016, 12(3), 671–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, C.; Restivo, V.; Gaglio, V.; Lanza, G.L.M.; Marotta, C.; Maida, C.M.; Mazzucco, W.; Casuccio, A.; Torregrossa, M.V.; Vitale, F. Effectiveness of an educational intervention on seasonal influenza vaccination campaign adherence among healthcare workers of the Palermo University Hospital, Italy. Ann Ig. 2019, 31(1), 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsaro, A.; Poscia, A.; de Waure, C.; De Meo, C.; Berloco, F.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G.; Laurenti, P.; Group, C. Fostering Flu Vaccination in Healthcare Workers: Forum Theatre in a University Hospital. Med Sci Monit. 2017, 24(23), 4574–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogliastro, M.; Borghesi, R.; Costa, E.; Fiorano, A.; Massaro, E.; Sticchi, L.; Domnich, A.; Tisa, V.; Durando, P.; Icardi, G.; Orsi, A. Monitoring influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a three-year survey in a large university hospital in North-Western Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022, 63(3), E405–E414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State of Vaccine Confidence in the European Union, 2022, Country Factsheets. Italy. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/state-vaccine-confidence-eu-2022_en#factsheets-by-country (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- EpiCentro. PASSI d’Argento. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi-argento/dati/VaccinazioneAntinfluenzale (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- PASSI and PASSI d’Argento National Working Group. PASSI and PASSI d’Argento and COVID-19 pandemic. First National Report on results from the COVID module, 1st ed.; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi-argento/pdf2020/PASSI-PdA-COVID19-first-national-report-december-2020.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Nelson, D.E.; Holtzman, D.; Bolen, J.; Stanwyck, C.A.; Mack, K.A. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Soz. Praventivmed. 2001, 46, S3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Belli, R.F.; Winkielman, P.; Read, J.D.; Schwarz, N.; Lynn, S.J. Recalling more childhood events leads to judgments of poorer memory: Implications for the recovered/false memory debate, Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1998, 5, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minardi, V.; D’Argenio, P.; Gallo, R.; Possenti, V.; Contoli, B.; Carrozzi, G.; Cattaruzza, M.S.; Masocco, M.; Gorini, G. Smoking prevalence among healthcare workers in Italy, PASSI surveillance system data, 2014-2018. Ann Ist Super Sanità, 2021; 57, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).