Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

16 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Attitude Estimation Algorithms

2.1. The SVD Algorithm

2.2. The Extended Kalman Filter

| Algorithm 1: The extended Kalman filter |

|

Data: inputs:

Result: Optimal state vector

Prediction Step:

1 Compute the Jacobian matrix of to find

2

3

Measurement update

4 Compute the Jacobian matrix of to find

5

6 Update the Kalman gain using (9)

7 Update the predicted state to find the optimal state estimate ,using (10)

8

|

2.3. SVD aided EKF algorithm

| Algorithm 2: The SVD aided EKF for attitude estimation |

|

Data: inputs:

Result: Optimal state vector

Prediction Step:

1 Similarly as in Algorithm 1.

Measurement update

2 Compute using in (2).

3 Compute the optimal attitude matrix using (3).

4 Compute from (Section 2.1) and use it as .

5 Convert to Euler angles using , and

6 Define the measurement vector using Euler angles and the angular velocity components.

7

8 Update the Kalman gain using (9).

9 Update the predicted state to find the optimal state estimate ,using (10).

10

|

3. System Model

3.1. System Kinematics

3.2. Environment Models

3.2.1. International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF)

3.2.2. PSA Sun Position Algorithm

3.3. Measurement Model

3.4. Coordinate Systems

4. Adaptive EKF

4.1. Expectation Maximization

| Algorithm 3: The Expectation Maximization Algorithm |

|

4.1.1. E Step

4.1.2. M Step

4.2. and adaptive EKF

| Algorithm 4: and adaptive EKF for attitude estimation |

|

Inputs:

Prediction Step:

Measurement update

for

end for

Outputs:

|

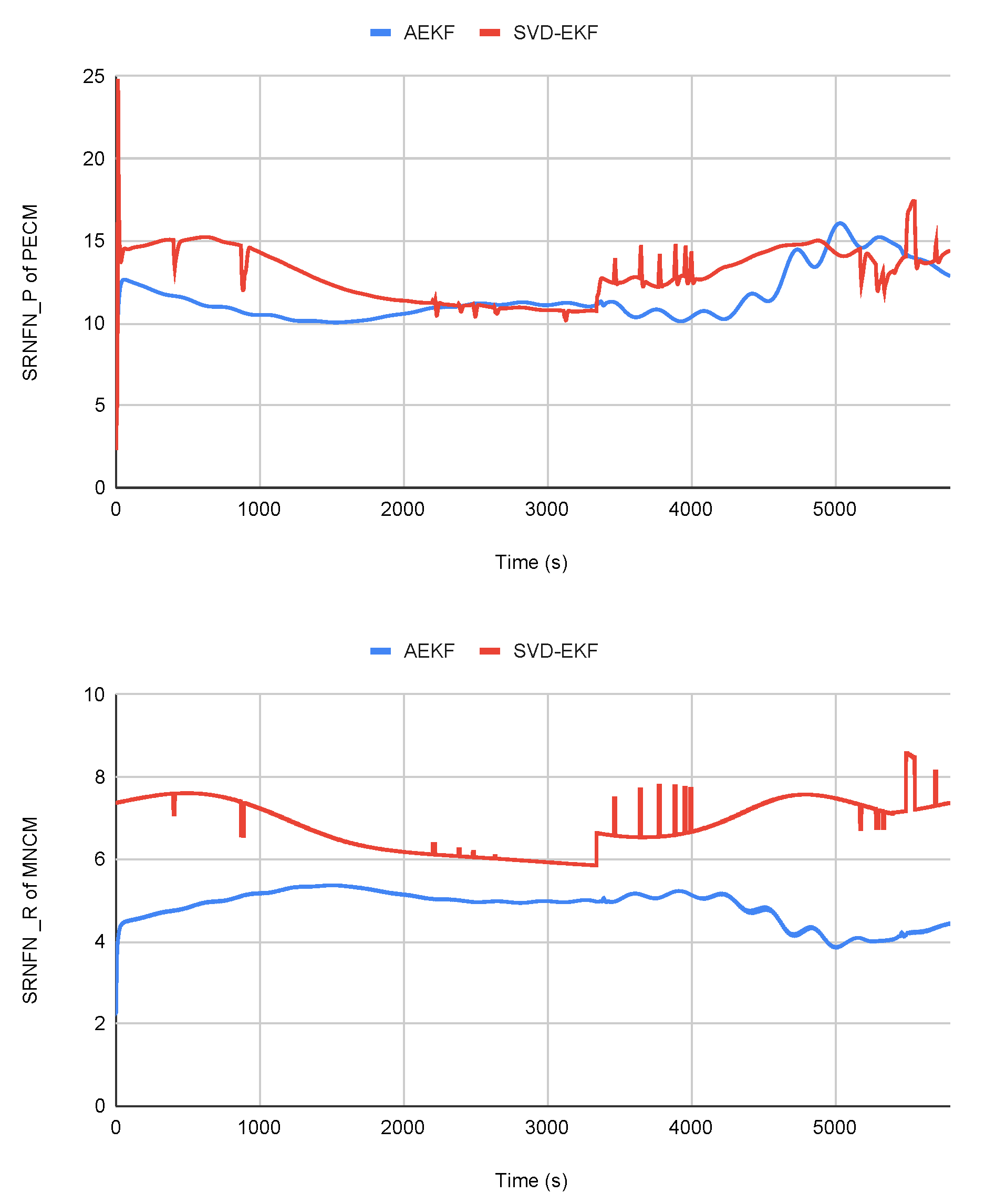

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Sun Phase

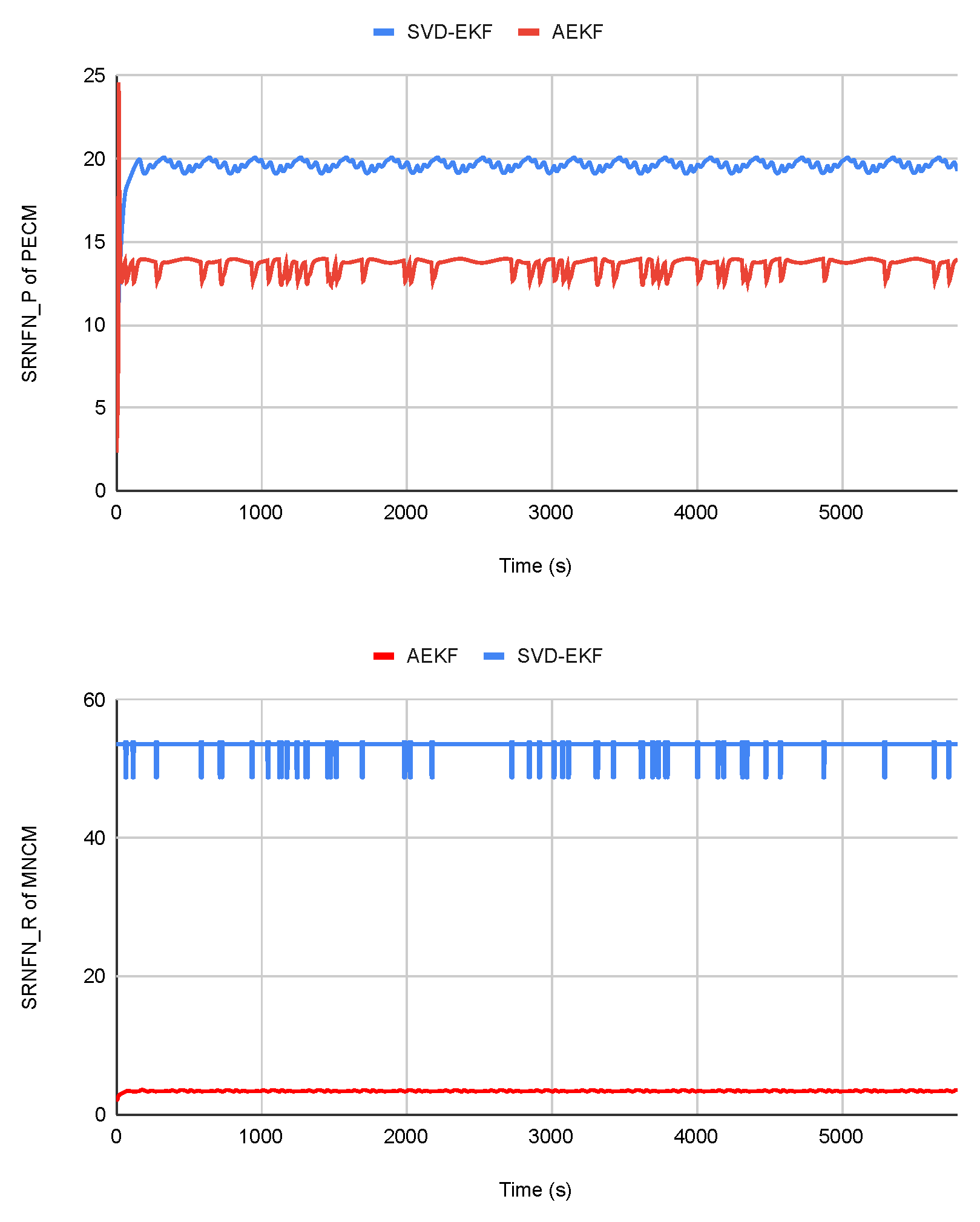

5.2. eclipse phase

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selva, D.; Krejci, D. A survey and assessment of the capabilities of Cubesats for Earth observation. Acta Astronautica 2012, 74, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, V.; Kuga, H.K.; Bringhenti, P.M.; de Carvalho, M.J. Attitude determination, control and operating modes for CONASAT Cubesats. In Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Space Flight Dynamics (ISSFD), Laurel, Maryland; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, N.H.; Böcker, S.; Munari, A.; Clazzer, F.; Moerman, I.; Mikhaylov, K.; Lopez, O.; Park, O.S.; Mercier, E.; Bartz, H.; et al. White paper on critical and massive machine type communication towards 6G. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.14146 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Wu, S.; Wang, T.; Xia, L.; Liu, S. NanoSats/CubeSats ADCS survey. In Proceedings of the 2017 29th Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC); 2017; pp. 5151–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.S.; Radanovic, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, S.; Fang, Y.; Khoshelham, K.; Palaniswami, M.; Ngo, T. Real-time monitoring of construction sites: Sensors, methods, and applications. Automation in Construction 2022, 136, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, M.D.; et al. A survey of attitude representations. Navigation 1993, 8, 439–517. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, W.; Hailey, C.; Gebert, G. Review of attitude representations used for aircraft kinematics. Journal of aircraft 2001, 38, 718–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.O. Attitude Representations. In 3D Motion of Rigid Bodies; Springer, 2019; pp. 185–230. [Google Scholar]

- Parwana, H.; Kothari, M. Quaternions and attitude representation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.08680 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, M.; Cheng, D.; Zhou, Z. An optimized triad algorithm for attitude determination. Artificial Satellites 2017, 52, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, C.; Guler, D.C. Review on gyroless attitude determination methods for small satellites. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2017, 90, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilden Guler, D.; Conguroglu, E.S.; Hajiyev, C. Single-Frame Attitude Determination Methods for Nanosatellites. Metrology and Measurement Systems 2017, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Crassidis, J.L.; Markley, F.L.; Cheng, Y. Survey of nonlinear attitude estimation methods. Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics 2007, 30, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markley, F.L.; Crassidis, J.L. Fundamentals of spacecraft attitude determination and control; Springer, 2014; pp. 1–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, J.R. Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Control (Astrophysics and Space Science Library 73); D. Reidel; 1978th edition, 1999.

- Kuga, H.K.; Carrara, V. Attitude determination with magnetometers and accelerometers to use in satellite simulator. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, C.; Cilden, D.; Somov, Y. Gyro-free attitude and rate estimation for a small satellite using SVD and EKF. Aerospace Science and Technology 2016, 55, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, C.; Çilden, D.; Somov, Y. Gyroless attitude and rate estimation of small satellites using singular value decomposition and extended Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC). IEEE; 2015; pp. 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cilden, D.; Hajiyev, C.; Soken, H.E. Attitude and attitude rate estimation for a nanosatellite using SVD and UKF. In Proceedings of the 2015 7th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies (RAST). IEEE; 2015; pp. 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Sumanth, R.M. Computation of eclipse time for low-earth orbiting small satellites. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakupoglu-Altuntas, S.; Esit, M.; Soken, H.E.; Hajiyev, C. Backup Magnetometer-only Attitude Estimation Algorithm for Small Satellites. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, XX, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, C.; Cilden-Guler, D.; Somov, Y. Attitude determination of nanosatellites in the sun-eclipse phases. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies (RAST); 2017; pp. 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- Hajiyev, C.; Cilden-Guler, D. Gyroless Nanosatellite Attitude Estimation in Loss of Sun Sensor Measurements. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, C.; Cilden-Guler, D. Satellite attitude estimation using SVD-Aided EKF with simultaneous process and measurement covariance adaptation. Advances in Space Research 2021, 68, 3875–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Li, J.; Song, R.; Li, Y. HE2LM-AD: Hierarchical and efficient attitude determination framework with adaptive error compensation module based on ELM network. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2023, 195, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wei, C. Adaptive iterated extended Kalman filter for relative spacecraft attitude and position estimation. Asian Journal of Control 2018, 20, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markley, F.L. Attitude determination using vector observations and the singular value decomposition. Journal of the Astronautical Sciences 1988, 36, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Lefferts, E.J.; Markley, F.L.; Shuster, M.D. Kalman filtering for spacecraft attitude estimation. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 1982, 5, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. Extended Kalman Filters. Reference Manual 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.W.; Park, C.G. Attitude estimation with accelerometers and gyros using fuzzy tuned Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the 2009 European Control Conference (ECC); 2009; pp. 3713–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alken, P.; Thébault, E.; Beggan, C.D.; Amit, H.; Aubert, J.; Baerenzung, J.; Bondar, T.; Brown, W.; Califf, S.; Chambodut, A.; et al. International geomagnetic reference field: the thirteenth generation. Earth, Planets and Space 2021, 73, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovec, K.L. A nonlinear magnetic controller for three-axis stability of nanosatellites. PhD thesis, Virginia Tech, 2001.

- Blanco, M.J.; Milidonis, K.; Bonanos, A.M. Updating the PSA sun position algorithm. Solar Energy 2020, 212, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.B.; Batzoglou, S. What is the expectation maximization algorithm? Nature biotechnology 2008, 26, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, T.K. The expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Signal processing magazine 1996, 13, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, T.B.; Wills, A.; Ninness, B. System identification of nonlinear state-space models. Automatica 2011, 47, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Wu, Z.; Chambers, J.A. A new adaptive extended Kalman filter for cooperative localization. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2017, 54, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2010, 33, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2015, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RMSE | SVD-EKF | AEKF |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2146 | 0.0042 | |

| 0.2220 | 0.0015 | |

| 0.2472 | 0.0024 | |

| 3.6076e-06 | 4.4296e-08 | |

| 7.7722e-06 | 8.8530e-08 | |

| 8.8545e-06 | 1.7761e-08 |

| Filters | SVD-EKF | AEKF |

|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | 7.94 | 8.46 |

| Filters | SVD-EKF | AEKF |

|---|---|---|

| ASRNFN | 13.0078 | 11.6005 |

| ASRNFN | 47.1554 | 4.8422 |

| RMSE | SVD-EKF | AEKF |

|---|---|---|

| 1.7126 | 0.1094 | |

| 12.6611 | 0.1388 | |

| 6.9083 | 0.3137 | |

| 7.9837e-05 | 1.3449e-07 | |

| 1.3499e-05 | 6.8046e-08 | |

| 1.9008e-04 | 1.8077e-08 |

| Filters | SVD-EKF | AEKF |

|---|---|---|

| ASRNFN | 19.5559 | 13.6083 |

| ASRNFN | 53.2372 | 3.4397 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).