1. Introduction

Third molars, mostly known under the name of wisdom teeth, are located at the very back of the mouth. They are the last adult teeth to erupt and above all teeth, they are the ones with the widest variability in terms of calcification and eruption. This variability is not directly related to gender, neither to sexual maturation, or growth, as it occurs with the other permanent teeth, however certain differences are merely based on the ethnicity [

1].

The crown begins its formation when the primitive dental lamina develops between the ages of 4 and 5, begins mineralizing between the ages of 9 and 10, and is finished between the ages of 12 and 15. At this point the eruptive phase starts, thanks to and ascensional movement: the inclination of the axis depends mainly on the space of the retro-molar trigone and on the posterior arch growth. Third molars (LM3) usually don’t develop fully until the ages of 18 to 24, and it is only then that they appear [

2,

3].

Often, wisdom teeth aren't a problem when they fail to erupt or they are partially erupted, but in some people they can lead to pain, swelling or pericoronaritis. The wisdom teeth may also damage nearby teeth and increase the likelihood of tooth decay, periodontal probing, root resorption and the cause of development of odontogenic cysts or tumors at the level of the second lower molar (LM2) [

4,

5].

Orthodontic complications, such as lack of space for third molar eruption, lower second molar impaction, the impairment of second molar distalization in III classes may also occur, and in the past they have represented the main reason why third molars were almost always extracted [

6].

Nowadays dentists are a bit more hesitant to extract them, owing the fact that their remotion can easily lead to further complications, ergo it is fundamental to be conscious when their avulsion is indicated and the right approach should be carefully evaluated first through a profound study of both orthopantomography and CBCT. The most recurrent complications consist in swelling and pain, secondary infection, trismus, ecchymosis, hemorrhage and alveolar osteitis. Inferior alveolar or lingual nerve paresthesia are reported, even though they are luckily uncommon. In order to avoid all the clinical issues aforementioned, an increasing number of oral surgeons are inclined to perform germectomy in young patients, rather than waiting for a future more invasive and higher risk surgery [

7,

8].

Germectomies can be performed at different stages of the third molar development. Very early germectomies are usually carried out between 7 and 11 years of age, when the bone crypt of the third molar is well defined, and it is usually located near the anterior border of the ramus. This allowed a shorter and less invasive treatment, that normally ends up as a simple curettage or the direct aspiration of the dental bud. Early germectomy are conduct between 12 and 15 years old, when the roof of the bone crypt is not fenestrated. At this stage, it is necessary to open the crypt surgically and the procedure is challenging, as the tooth bud tends to pivot easily on itself and the crown should always be sectioned. The most favorable stage for germectomies is considered between 14 and 18 years old, because the crypt's bony cover has partially resorbed, while its crown remains submucosal. Despite being enclosed in its follicular membrane, the tooth is not at risk of infection. If extraction is necessary, it is best to perform the operation before the crown has emerged [

9,

10].

Generally, the extraction of impacted wisdom teeth and germectomies consists in the incision of soft tissues, the detachment of the periodontal ligament if present, the bone removal with high-speed drill and bone-cutting burs, and sometimes even tooth separation if necessary. After that, the bruising of the alveolar site and the irrigation with clorhexidine or physiologic solution is recommended, that for the accurate remotion of debris. Then, 4/0 sutures are applied, for a nice and smooth wound healing. Unfortunately, all those steps of the intervention might lead to the several aforementioned side effects. Correspondingly, the choice of the flap design and the type of surgical bone removal seems to be crucial for a safe and satisfying result. Yet the results reported by some investigators indicate no differences between the type of the flap in terms on post-operative clinical attachment level, and probing depth on the LM2 and swelling or post-operative pain perception. On the flip of the coin, maximum mouth opening might be influenced by the type of incision of choice [

11,

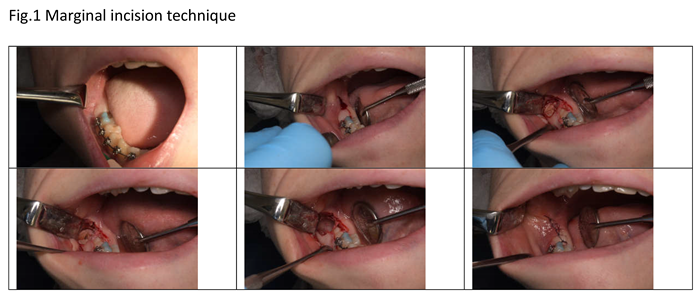

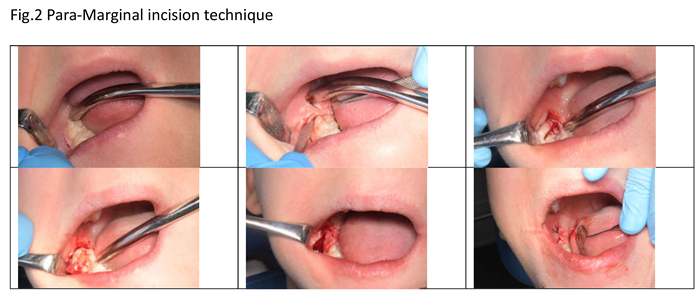

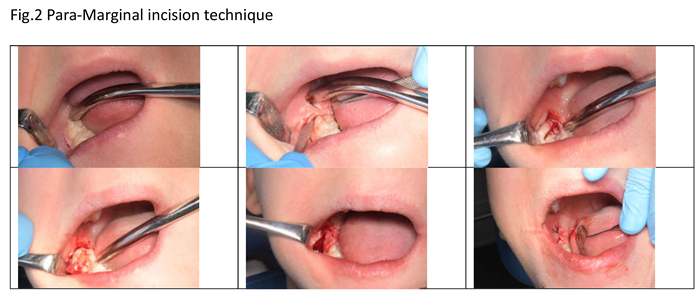

12]. For what concerns the flap design, marginal and paramarginal flaps are the most used for germectomies, in association with a distal discharge. For both methods, the incision goes from the first molar until the second molar, and the discharge cut goes from the half of the second molar, to distal with a 45° inclination, which is sufficient to achieve the vestibular bone where there is the third molar bud. In the marginal technique, the flap design goes into the gingival sulcus and intra-papillar, meanwhile in the para-marginal technique, the incision goes between the adhering gengiva and the free gingiva [

13].

The aim of the present prospective study is to compare the influence of the marginal and paramarginal flap designs, in terms of wound healing, depth fo the distal margin of the second molar, post-operative pain perception, maximum mouth opening and swelling.

2. Materials and Methods

Population

For this study, forty patients, between 11 and 16 years old were recruited: they presented either right or left mandibular impacted third molars buds, whose extraction was suggested for prophylactic and orthodontic reasons.

Before the surgical procedure, all patients’ parents received an informed consent, proper informations about the intervention, post-operative recommendations and eventual complications which might appear following the extractions. Although patients and parents were blind about which incisional technique were they going to be submitted to.

Intervention and Comparison

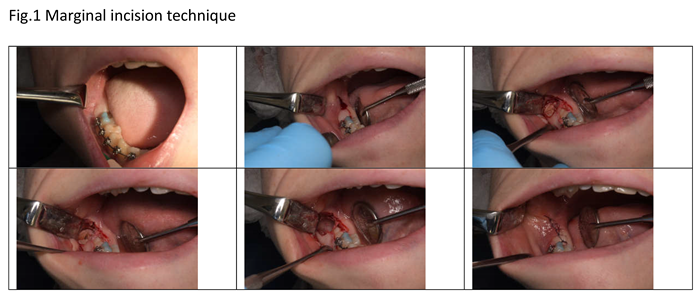

Forty germectomies were performed, above them, there were twenty mandibular right third molars (RLM3) and twenty mandibular left third molars (LLM3). Half germectomies were carried out with a marginal incision technique (Figure 1) (ten LLM3 and 10 RLM3), the other half with a para-marginal incision technique (Figure 2) (ten LLM3 and 10 RLM3), previously randomized with the computer program IBM spss®.

The intervention was fully standardized as all patients were operated by the same surgeon, within a previous accurate study of the orthopantomography.

Before the surgery, the following measurements were evaluated by a blind researcher, who didn’t know which patients were going to receive either marginal or para-marginal technique.

The periodontal evaluation of the LM2, was carried out based on: plaque index (in percentages), bleeding on probing index (BoP) and probing (in mm) of the distal surface of the tooth with a periodontal probe. The maximum opening of the mouth was evaluated with millimetric scale, from the incisal border of the superior incisor to the incisal border of the inferior incisor. Data were evaluated before and after the surgical removal of third molar and reported in a data set.

Before the extraction was carried on, it was performed and inferior alveolar nerve block and a buccinator nerve block.

One week after surgery, the complete periodontal evaluation of the LM2, post-operative pain perception (evaluated by the patient based on a VAS scale) and post-operative swelling were reported. All measurements were collected in a data set, as previously specified.

Plaque index was calculated with a T-test, The maximum mouth opening with a mean test, distal probing and post-operative pain will be evaluated with the mean test.

3. Results

For the present prospective study, forty patients, twenty-two females and eighteen males, between 11 and 16 y.o. were recruited. Forty germectomies were performed, half with marginal incision technique, half with para-marginal incision technique. No drop-out were reported.

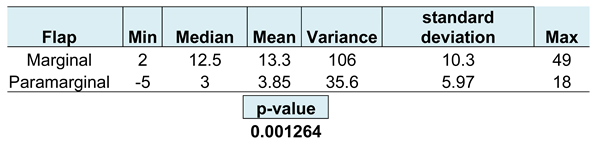

Plaque Index

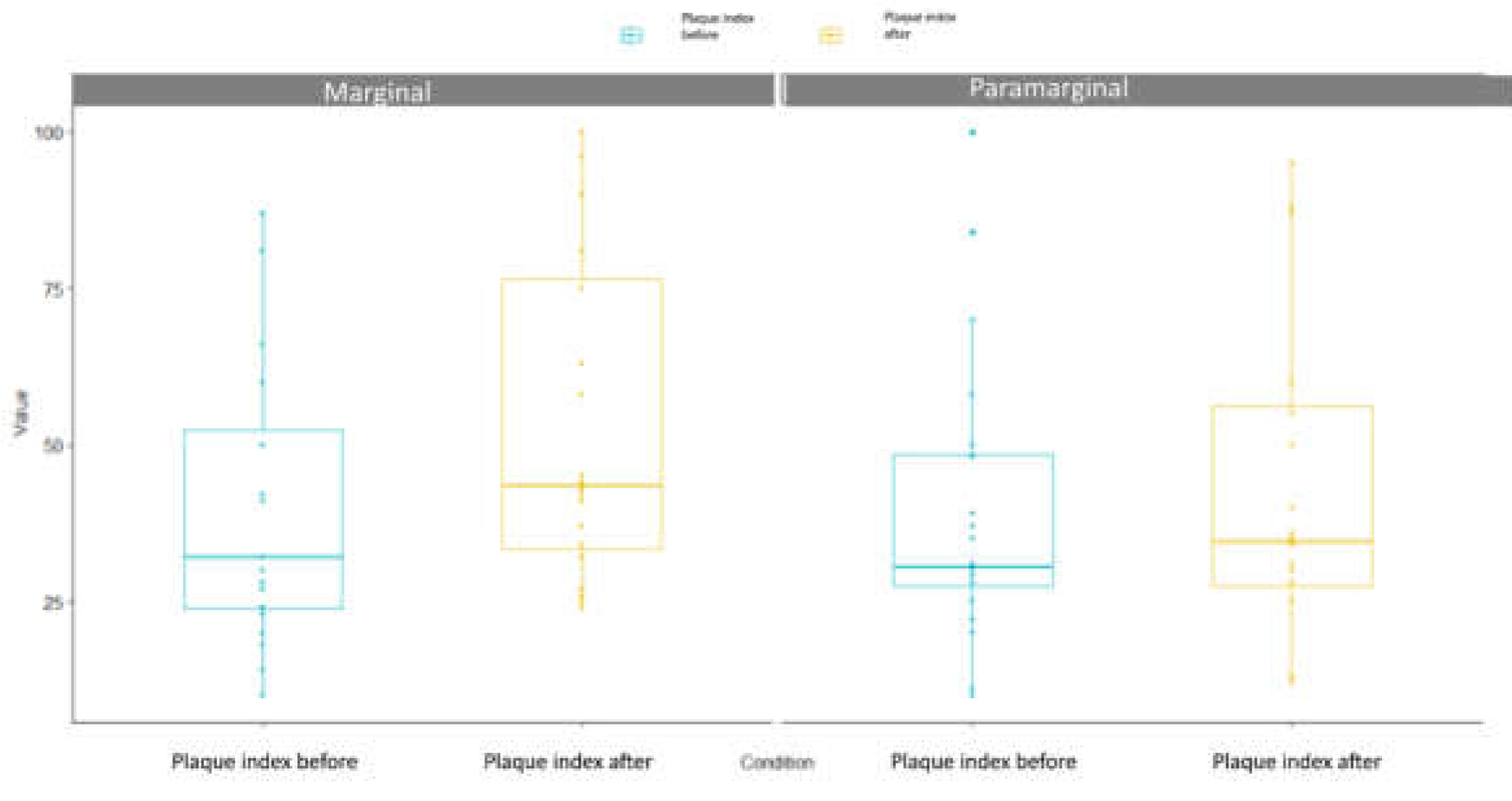

In

Figure 3 and

Table 1, it is appreciable that an higher percentage of plaque (> 13%) was observed after performing the marginal flap, meanwhile a similar plaque percentage was reported before and after the para-marginal flap technique (> 3,8%). SSD were reported between marginal flap technique compared with the para-marginal flap technique (p-value = 0.001264).

BoP Index

The pre-surgical BoP Index, revealed that there was a slightly higher number of bleeding patients in paramarginal group (9 patients, 45%) than in marginal group (7 patients, 35%). Instead, no bleeding was reported in 13 patients (65%) belonging to marginal group, and 11 patients (55%) in para-marginal group. After marginal flap, no bleeding was reported in 1 patients (5%) and bleeding was experienced in the remaining 19 patients (95%). For what concerns the para-marginal flap, BoP was reported in 6 patients (30%) and 14 patients (70%) no bleeding was observed. In general, there was a reduction of BoP about 65% in para-marginal flap compared to the marginal one. For further clarification, please check

Table 2.

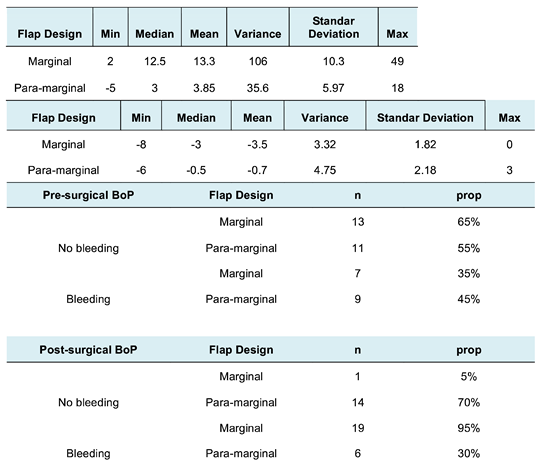

Maximum Mouth Opening Index

Maximum Mouth Opening range is similar between groups at baseline and it slightly diminished in marginal group (3,5%) compared to para-marginal group (0.7%), as specified in

Table 3. In some cases the maximum mouth opening in the para-marginal group was wider as reported in

Figure 4. SSD were reported between the two techniques, as the p-value is 0.001264.

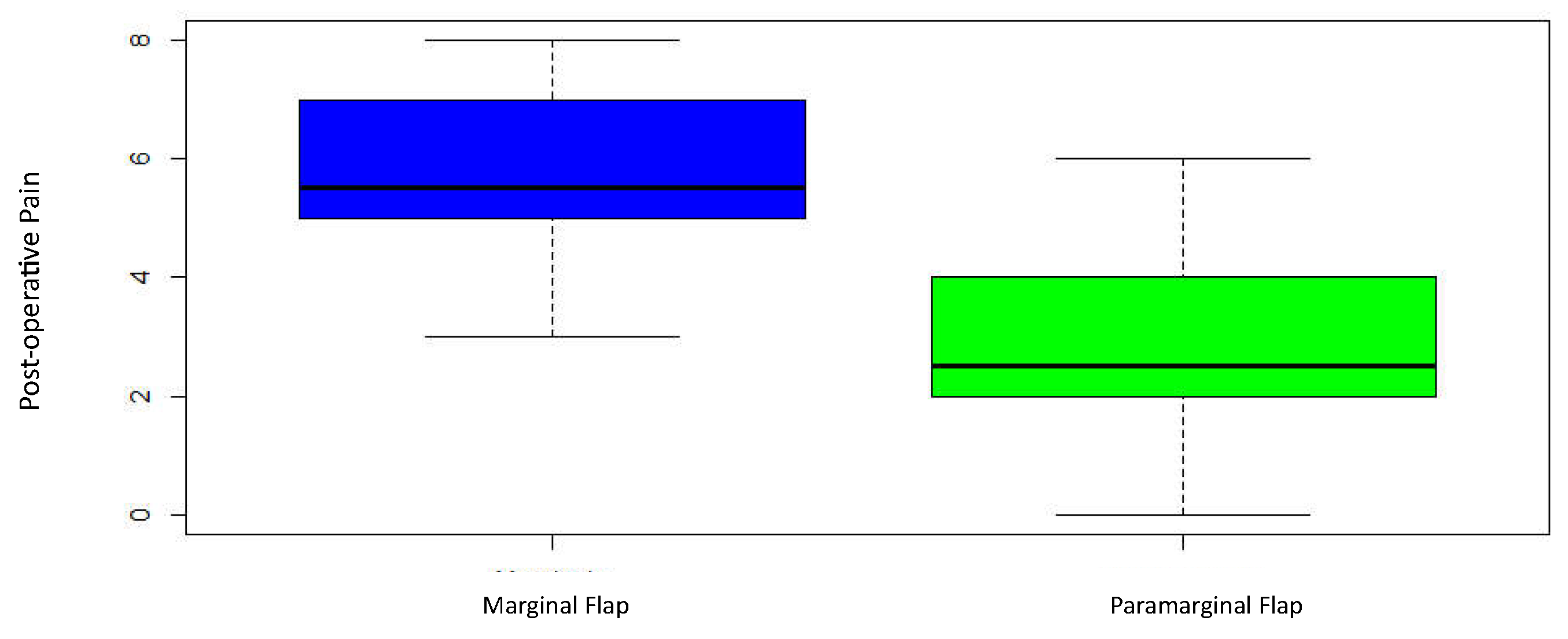

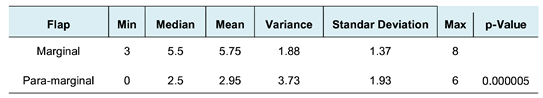

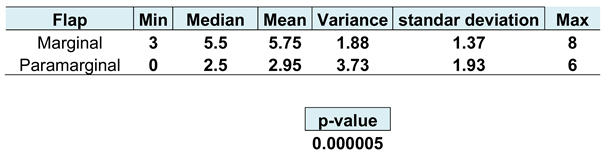

Post-Operative Pain Perception

Highly SSD were found in patients receiving the para-marginal flap (5.75

± 1.37), who reported a lower pain level,, compared with the ones who received the marginal flap technique (2.95

± 3.73), with a p-value of 0,000005 (

Figure 5 and

Table 4).

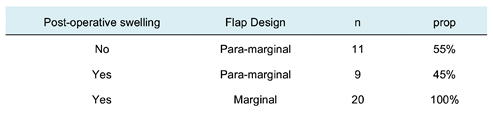

Post-Operative Swelling

All patients treated with a marginal flap experienced a visible swelling on the mid-cheek and molar region. 11 patients (55%) receiving para-marginal flap do not refer any swelling, but 9 patients do (45%) (

Table 5).

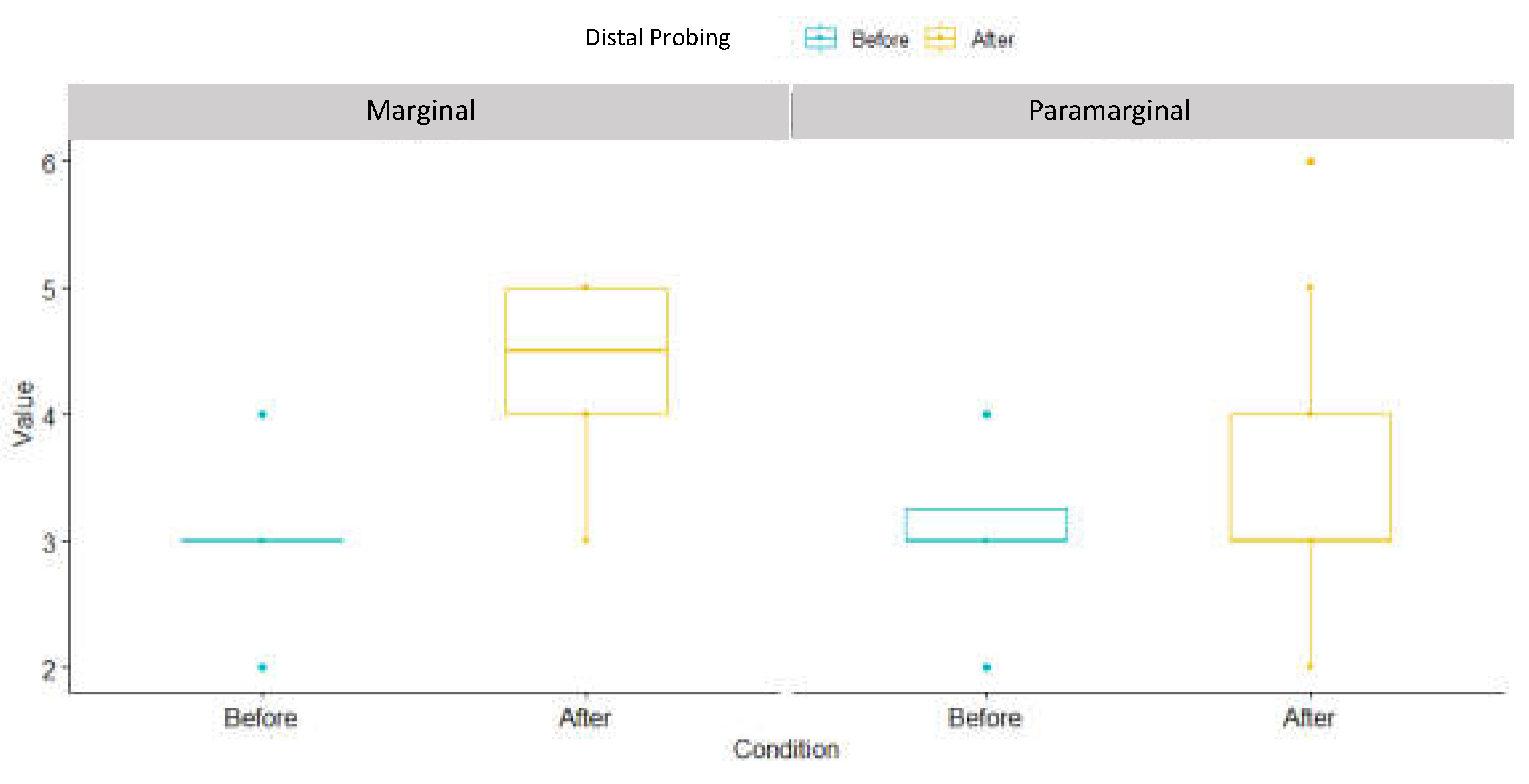

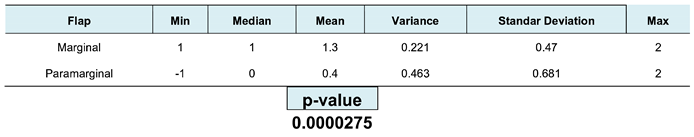

Distal probing

As reported in

Figure 6 and

Table 6, distal probing has significantly increased in marginal incision (1,3 ± 0,47) in comparison with para-marginal incision (0,4 ± 0,687), as reported by the p-value = 0,0000275.

4. Discussion

Late germectomy of third mandibular molars represents a valuable alternative to early germectomy or delayed third molar extraction. Certainly, it is not risk free, but it is no doubts the safest and minimally invasive alternative available at the present time.

As previously mentioned, some well-known and frequently reported complications might occur. The right choice of the flap design represents one of the factors that might influence the occurrence or the absence of post-operative complications. This is the main reason why the present study have focused on two different flap designs: the marginal flap, which is the mostly used for third molar extraction and the para-marginal flap, which allows to respect the supracrestal tissue attachement and potentially preserve the periodontal health.

According to our study, the marginal flap is more plaque retentive and a higher level of BoP on the distal second lower molar was reported. In addition, patients reported a greater difficulty on reaching the maximum mouth opening, which was diminished compared with the baseline. Post-operative pain perception swelling, tumefaction and distal probing were higher in those patients in which the marginal flap technique was carried out. Therefore, the results of the present study support the concept that para-marginal approach is less invasive and more conservative in terms of periodontal health. From the patient’s perspective, the para-marginal technique is also better acceptedas this non-invasive incision lead to less post-operative discomfort in terms on maximum mouth opening, tumefaction and pain perception.

Similar results were reported by Suarez Cunquiero et al., in fact, in their study, it was observed a statistically significant increase of the probing depth at the buccal and distal sites of the adjacent second molars in the marginal flap group at day 5 and 10 after surgery. In the para-marginal flap group, a lower probing depth was always reported, compared with the marginal flap group. On the other hand, similar results were reported in terms of plaque index, BoP, pain, trismus, and swelling, for marginal and para-marginal approaches [

14].

On the flip side of the coin, Shahzad, et al. reported that no SSD was found between the marginal flap and the para-marginal flap at week 1 and 2 in appearance of wound dehiscence (p > 0.05). Likewise, no SSDs were found in the buccal and distal probing depths of the adjacent second molar (p > 0.05) [

15].

Again, Chalkoo et al, in a study carried out in 2015, showed that there were no significant differences between the marginal and paramarginal flaps in terms of maximum mouth opening before surgery, on the second and seventh day after surgery (

Table 1). However, both techniques were associated with a significant restricted mouth opening at second day after surgery (P<0.001) and a significant improvement at seventh day after surgery (P<0.001) [

16].

Para-marginal and marginal incision techniques could also be used in highly esthetic surgeries, for example in canine. Kösger et al have found that there are no SSDs were present between marginal and para-marginal flap design in plaque index, gingival index and probing depth at any timepoint [

17].

Since it is an anterior region, it is much easier to keep it clean and plaque free, and, hence, it is likely that no differences in plaque retention are appreciable in this case. Conversely, in the area of third molars there is an higher possibility of saliva stagnation and the flap choice might play a crucial role to achieve more cleansable situation. .

To avoid secondary effects after third molar surgery, many authors have developed their own flap design. Some of them are designed with a marginal approach, such as the envelope flap, the modified envelope flap or the triangular flap. Other flap designs, as the Szmyd flap, the modified Szmyd flap and the modified triangular flap all have in common the submarginal incision technique, which is comparable to a para-marginal approach [

18,

19].

According to Chen et al., the para-marginal flap turns out to have a greater periodontal depth reduction, compared with other types of flaps that adopt the marginal incision. A possible explanation consists of the fact that the sub-marginal incision flaps may provide the advantage of maintaining gingival margin height by eliminating the need to detach the keratinized gingiva and leaving a whole gingival collar around the adjacent molar. This procedure minimized the impact that the surgery inevitably has on the periodontal health of the adjacent second molar [

19]. In fact, the apical incision allows a better papillae conservation and that promotes higher standards of oral hygiene, together with a reduced amount of plaque retention. A lower proliferation of bacterias due to stagnation and inflammation prospects a lower BoP level, as it has occurred in our study in the para-marginal group.

Above all, it has to be considered that in the absence of inflammation a faster and better wound healing is promoted. In the study by Jakse et al., , 57% of cases treated with a sulcular flap approach resulted in wound healing failure or dehiscence. Conversely , only 10% of cases approached with a sub-marginal flap developed a wound dehiscence after third molar surgery [

20]. In or study, at one week from surgery, no failure in the wound healing has been reported because of the short time-period, but a higher level of BoP was detected in the marginal group, which suggested an increased risk of wound healing failure. BoP and wound healing failure might happen also when there is a lack of stability on the flap and more tension is created on the surgical site. Some Authors assert that more invasive procedures, such as a para-marginal approaches with vertical incisions lead to a greater probability of higher pain levels. It is believed that a more conservative approach decreases post-operative pain and tumefaction [

21,

22,

23]. A part from that, pain, tumefaction and reduced mouth opening are also strongly associated with the osteotomy and surgery time, which are profoundly influenced by the position of the LM3 respect to the mandibular ramus and their inclination, according to Pell y Gregory and Winter’s classification. Post-operative discomfort is reduced in short-time surgery, this is one more reason why germectomy is recommended instead of waiting for the complete formation of the LM3, especially because it is not possible to predict with certain its final position once fully formed [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Different solutions have been investigated in order to reduce post-operative discomfort, such as the application of cryotherapy and laser therapy, but only small improvements have been detected. Time and medications are still the primary solution for reducing post-surgical complications [

27,

28].

Furthermore, regarding the formation of a periodontal pocket distal to the adjacent LM2, this represents the most common and known post-operative complication, as described by many Authors. A direct correlation between pain, tumefaction, PD and BoP is not proved, but it appears that younger patients are less prone to display periodontal pockets and generally the PD is demonstrated to be significantly lower compared to adult patients [19- 22- 29]. In the present study an higher PD was registered in patients treated with a marginal approach, yet, age seemed to play a role on the development of a periodontal pocket distal to the LM2. Once again, this is influenced by the position of the LM3 and the capability of tissues repair, which is higher in younger patients where the roots of LM3 are not fully formed and the bone of the ramus is not completely calcified [

30]. Some Authors suggest employing bone grafts to improve the PD distal to the LM2 nonetheless, this does not seem to drastically improve the periodontal health [

31,

32].

5. Conclusions

In light of the above, the para-marginal flap design showed more promising results compared to the marginal flap design. Periodontal health is better preserved in terms of PI, PD and BoP and MOM, PP and PT are reduced in the para-marginal flap compared with the marginal flap, which represents less discomfort and consequences for the patient’s prospective. Therefore, we recommend to have a sub-marginal approach in late germectomies as secondary effects seem to be strongly reduced, even if further investigations on this topic are highly suggested.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.Z.. and F.S.L..; methodology, M.M..; validation, S.M.., E.S. and F.S.L..; formal analysis, R.G.P.; investigation, M.M..; resourcs,F.R..; data curation, R.G.P; writing—original draft preparation, E.; writing—review and editing, E.S..; visualization, S.M.; supervision, F.R..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to normal dental activity. None of the used technique is a new technique and both are commonly used to germetcomy.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors do not have any financial interest in the companies whose materials are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garn SM, Lewis AB, Vicinus JH: Third molar polymorphism and its significance to dental genetics. J Dent Res 1963; 42:1344-1363. [CrossRef]

- Richardson M. Impacted third molars. Br Dent J 1995;178:92. [CrossRef]

- Seward GR, Harris M, McGowan DA, editors. An outline of oral surgery I. Oxford: Wright; 1999. p. 52-92.

- Peñarrocha-Diago M, Camps-Font O, Sánchez-Torres A, Figueiredo R, Sánchez-Garcés MA, Gay-Escoda C. Indications of the extraction of symptomatic impacted third molars. A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021 Mar 1;13(3):e278-e286. doi: 10.4317/jced.56887. PMID: 33680330; PMCID: PMC7920557. [CrossRef]

- Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Toedtling V, Perry J, Tummers M, Hoppenreijs TJ, Van der Sanden WJ, Mettes TG. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 May 4;5(5):CD003879. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub5. PMID: 32368796; PMCID: PMC7199383. [CrossRef]

- Mazur M, Ndokaj A, Marasca B, Sfasciotti GL, Marasca R, Bossù M, Ottolenghi L, Polimeni A. Clinical Indications to Germectomy in Pediatric Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 10;19(2):740. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020740. PMID: 35055565; PMCID: PMC8775662. [CrossRef]

- Sbricoli L, Cerrato A, Frigo AC, Zanette G, Bacci C. Third Molar Extraction: Irrigation and Cooling with Water or Sterile Physiological Solution: A Double-Blind Randomized Study. Dent J (Basel). 2021 Apr 1;9(4):40. [CrossRef]

- Staderini E, Patini R, Guglielmi F, Camodeca A, Gallenzi P. How to Manage Impacted Third Molars: Germectomy or Delayed Removal? A Systematic Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Mar 26;55(3):79. doi: 10.3390/medicina55030079. PMID: 30917605; PMCID: PMC6473914. [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli Angelo, Pecora Camilla Nicole, Arun K Garg. Early Third Molar Extraction: When Germectomy Is the Best Choise. Inter Ped Dent Open Acc J 4(4)- 2020. IPDOAJ.MS.ID.000192. DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.04.000192. [CrossRef]

- Lysell L, Rohlin M. A study of indications used for removal of mandibular third molar. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 17:161-164. [CrossRef]

- Y.-W. Chen, C.-T. Lee, L. Hum, S.-K. Chuang, Effect of flap design on periodontal healing after impacted third molar extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis, International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Volume 46, Issue 3, 2017, Pages 363-372, ISSN 0901-5027. [CrossRef]

- Woolf RH, Malmquist JP, Wright WH. Third molar extractions: periodontal implication of two flap designs. Gen Dent 1978;26:52-6.

- Shofield ID, Kogon SL, Donner A. Long-term comparison of two surgical flap designs for third molar surgery on the health of the periodontal tissue of the second molar tooth. J Can Dent Assoc 1988;54:689-91.

- Suarez-Cunqueiro MM, Gutwald R, Reichman J, Otero-Cepeda XL, Schmelzeisen R. Marginal flap versus paramarginal flap in impacted third molar surgery: a prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003 Apr;95(4):403-8. PMID: 12686924. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Asif Shahzad, et al. "Outcome of management of mandibular third molar impaction by comparing two different flap designs." Pakistan Oral and Dental Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 30 June 2014, pp. 235+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A381474429/AONE?u=anon~19344d62&sid=googleScholar&xid=96bb8df2. Accessed 20 Feb. 2023.

- Chalkoo, Altaf Hussain et al. “Effect of two triangular flap designs for removal of impacted third molar on maximal mouth opening —.” (2015).

- Köşger H, Polat HB, Demirer S, Ozdemir H, Ay S. Periodontal healing of marginal flap versus paramarginal flap in palatally impacted canine surgery: a prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 Sep;67(9):1826-31. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.023. PMID: 19686917. [CrossRef]

- Abdulmoein AlFotawi R. Flap Techniques in Dentoalveolar Surgery. Oral Diseases [Internet]. 2020 May 13; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.91165. [CrossRef]

- Chen YW, Lee CT, Hum L, Chuang SK. Effect of flap design on periodontal healing after impacted third molar extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017 Mar;46(3):363-372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.08.005. Epub 2016 Sep 3. PMID: 27600798. [CrossRef]

- Jakse N, Bankaoglu V, Wimmer G, Eskici A, Pertl C. Primary wound healing after lower third molar surgery: evaluation of 2 different flap designs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002 Jan;93(1):7-12. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.119519. PMID: 11805771. [CrossRef]

- Shevel E, Koepp WG, Butow KW. A subjective assessment of pain and swelling following the surgical removal of impacted third molar teeth using different surgical techniques. SADJ 2001; 56:238-41.

- Glera-Suárez P, Soto-Peñaloza D, Peñarrocha-Oltra D, Peñarrocha-Diago M. Patient morbidity after impacted third molar extraction with different flap designs. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020 Mar 1;25(2):e233-e239. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23320. PMID: 32062667; PMCID: PMC7103454. [CrossRef]

- DE Marco G, Lanza A, Cristache CM, Capcha EB, Espinoza KI, Rullo R, Vernal R, Cafferata EA, DI Francesco F. The influence of flap design on patients' experiencing pain, swelling, and trismus after mandibular third molar surgery: a scoping systematic review. J Appl Oral Sci. 2021 Jun 4;29:e20200932. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2020-0932. PMID: 34105693; PMCID: PMC8232931. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Garcia A, Gude Sampedro F, Gandara Rey J, Gallas Torreira M. Trismus and pain after removal of impacted lower third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:1223-6. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Herrera RS, Esparza-Villalpando V, Bermeo-Escalona JR, Martínez-Rider R, Pozos-Guillén A. Agreement analysis of three mandibular third molar retention classifications. Gac Med Mex. 2020;156(1):22-26. English. doi: 10.24875/GMM.19005113. PMID: 32026883. [CrossRef]

- Karaca, Inci, et al. "Review of flap design influence on the health of the periodontium after mandibular third molar surgery." Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology 104.1 (2007): 18-23. [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento-Júnior EM, Dos Santos GMS, Tavares Mendes ML, Cenci M, Correa MB, Pereira-Cenci T, Martins-Filho PRS. Cryotherapy in reducing pain, trismus, and facial swelling after third-molar surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019 Apr;150(4):269-277.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.11.008. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 30798949. [CrossRef]

- Duarte de Oliveira FJ, Brasil GMLC, Araújo Soares GP, Fernandes Paiva DF, de Assis de Souza Júnior F. Use of low-level laser therapy to reduce postoperative pain, edema, and trismus following third molar surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2021 Nov;49(11):1088-1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2021.06.006. Epub 2021 Jun 22. PMID: 34217567. [CrossRef]

- Passarelli PC, Lopez MA, Netti A, Rella E, Leonardis M, Svaluto Ferro L, Lopez A, Garcia-Godoy F, D'Addona A. Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Nov 30;10(12):2410. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10122410. PMID: 36553934; PMCID: PMC9777857. [CrossRef]

- Low SH, Lu SL, Lu HK. Evidence-based clinical decision making for the management of patients with periodontal osseous defect after impacted third molar extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Sci. 2021 Jan;16(1):71-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.018. Epub 2020 Aug 8. PMID: 33384781; PMCID: PMC7770311. [CrossRef]

- Hassan KS, Marei HF, Alagl AS. Does grafting of third molar extraction sockets enhance periodontal measures in 30- to 35-year-old patients? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Apr;70(4):757-64. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.010. Epub 2011 Dec 16. PMID: 22177808. [CrossRef]

- Barbato L, Kalemaj Z, Buti J, Baccini M, La Marca M, Duvina M, Tonelli P. Effect of Surgical Intervention for Removal of Mandibular Third Molar on Periodontal Healing of Adjacent Mandibular Second Molar: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. J Periodontol. 2016 Mar;87(3):291-302. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150363. Epub 2015 Nov 26. PMID: 26609696. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).