1. Introduction

Research has described an increasing incidence of adolescents with Atypical Anorexia Nervosa (AAN) reported in literature in recent years [

1,

2,

3]. Based on DSM-5, individuals with AAN meet the criteria for Anorexia Nervosa (AN), except that despite significant weight loss, their presenting Body Mass Index (BMI) lies within or above the average range [

4,

5]. Previously classified as Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Stated (EDNOS) in DSM-IV, AAN is now classified as a subtype of Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED) in DSM-5 since 2013 [

4]. An Australian study in 2010 documented more than a five-fold increase of cases with AAN among hospitalized adolescents from 8% to 47% over a 6-year period [

3]. To date, most literature on AAN has occurred in predominantly Caucasian female samples [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Nonetheless, even in these samples, an increased proportion of males and non-Caucasian individuals has been noted amongst individuals with AAN, suggesting the prevalence of AAN may be higher in males [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

14] and non-White populations [

1,

6,

7,

12,

13,

14].

While it is well established that individuals with AN are at risk for significant medical complications due to malnutrition and low body weight, there is growing recognition that significant or rapid weight loss can lead to similar complications for individuals with AAN despite at a normal weight or overweight [

3]. Recent systematic reviews found that individuals with AAN experience similar rates of physical complications of malnutrition (such as bradycardia and hypotension) [

2,

15] and lower rates of menstrual disturbances than individuals with AN [

2,

6,

14,

16,

17]. Moreover, individuals with AAN have increased eating disorder symptomatology with similar rates of depression compared to individuals with AN [

3,

8,

11,

16,

18,

19,

20].

Although literature indicates that individuals with AAN are at risk for medical instability [

3,

16], limited literature has examined which weight variables that are important for medical instability in adolescents with AAN and AN. Both in predominantly Caucasian samples of adolescents with AN and AAN, Whitelaw et al. identified total and recent weight loss as predictors of bradycardia independent of presentation weight [

3] while Garber et al. showed that the rate of weight loss was associated with lower heart rate independent of admission weight [

14].

As research that suggests that demographic pattern of AAN may differ from AN [

1] and the emergency of eating disorders in Asia [

21] with certain ethnic groups at higher risk [

22], it is critical to fill the significant literature gap in understanding the epidemiology and presentations of AAN and predictors of illness severity in diverse samples, including Asian adolescents. Our study thus aims to address these gaps by describing the baseline characteristics and first presentations in both the inpatient and outpatient setting of adolescents with AN and AAN in a multi-ethnic Asian population and to understand the factors associated with physical and psychological markers of illness severity in this sample.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject selection

Study data was retrieved from case notes of all patients below the age of 18, who presented for evaluation for an eating disorder at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital between January 2010 and October 2020. Cases were reviewed by an adolescent medicine physician and a psychologist with expertise in EDs for retrospective diagnosis according to the DSM-5 criteria [

4] Low weight for AN was defined as %mBMI of less than 87% which is consistent with other studies on adolescent ED [

23]. Patients who met all criteria for AN, except their weight was within or above normal range (defined as %mBMI of greater than 87%) despite significant weight loss were classified as atypical AN. Patients with Bulimia Nervosa, Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder and other unspecified conditions were excluded from the study. Data for this study was used in accordance and with approval from SingHealth Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Patient variables at presentation

Ethnicity, highest historical weight and corresponding height, menstrual status, duration of weight loss, the presence of purging, and use of weight loss medications were self-reported by patients and parents at first presentation. Measurements for height, weight, and orthostatic measurement of heart rate and blood pressure (lying and standing) were abstracted from the clinical record. Admission data included the reasons for admission (which may include more than one) and admission duration.

2.3. Weight variables and menstrual history

Percent median BMI (%mBMI) was calculated using the BMI of the patient divided by the 50th percentile BMI corrected for their age and gender, and multiplied by 100. Fiftieth percentile BMI (%mBMI) for exact age was determined using the BMI-for-age growth charts for Singapore children and adolescents aged 4 to 18 years [

24]. Weight loss was defined as the change in %mBMI from highest %mBMI to the %mBMI at presentation. The duration of weight loss (months) was the time between the highest weight and the presentation date. Rate of weight loss was the change in %mBMI divided by the duration of weight loss [

14].

Secondary amenorrhea was defined as the disruption of previously regular menstruation cycles for 3 months or more [

25].

2.4. Admission criteria

Criteria for admission included physiological instabilities such as bradycardia (<50 beats/min daytime; <45 beats/min at night) and hypotension (<90/45 mmHg) or acute medical complications (such as syncope), as per published international guidelines [

26]. Patients admitted for medical instabilities are placed on ED protocols for medical stabilization [

27]. Besides admission for medical instabilities, patients may also be admitted to evaluate for other organic causes of weight loss or hospitalized for safety in the event of attempted self-harm or suicide requiring medical or safety monitoring.

2.5. Psychological measures

Eating Disorder Evaluation Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [

28] is a self-administered questionnaire with scores ranging from 1 to 9 and higher scores indicating greater ED psychopathology severity. The questionnaire was administered by a clinical psychologist trained in ED at first presentation and routine administration of the questionnaire started in our service from 2016, in-line with clinical practice recommendations. Psychiatric comorbidities of depressive and anxiety symptoms, suicidal ideations or self-harm were evaluated by psychologists or psychiatrists who were part of the treating team.

2.6. Statistical analysis

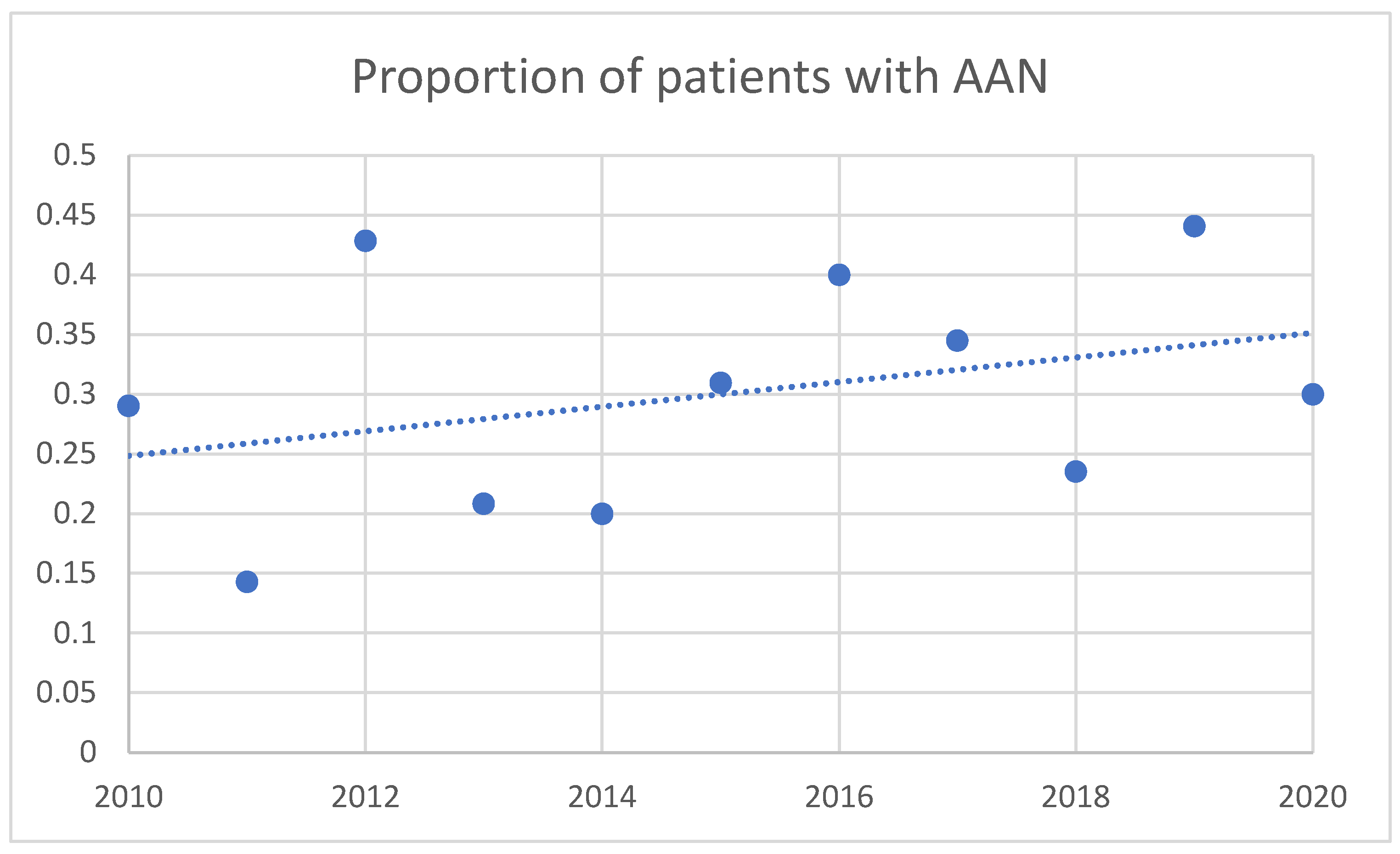

Data was extracted for statistical analysis using SPSS software version 19 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Baseline demographic and anthropometric measurements of study participants were compared between AN and AAN patients using two independent samples t test (or Wilcoxon rank sum, depending on normality) and chi-square (or Fisher exact test, where appropriate) for continuous and categorical variables. Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The number of adolescents with AAN was presented as a proportion of the total AN and AAN cases along with a line of best fit. Associations between 3 weight history variables (independent variables) and markers of illness severity were examined with multiple regression models. The four independent weight variables are: 1) %mBMI 2) Change in %mBMI 3) Rate of weight loss 4) Duration of weight loss. Models were adjusted for gender, age and race. Multivariable linear regression, followed by stepwise backward selection, was used to examine the contribution of the weight variables on illness severity outcomes measures. Markers of illness severity are indicators of medical instability (heart rate and systolic blood pressure), duration of admission and ED psychopathology (global EDE-Q scores).

3. Results

The study population consisted of 459 adolescents with a mean age of 14.1 (±1.5) years (range 9-18 years), with a mean duration of illness of 8.1(±6.2) months. The study sample was 90.2% female with 318 patients (62.7%) diagnosed with AN and 141 patients (27.8%) diagnosed with AAN. There was a greater proportion of males (15.6% vs. 7.2%,

p = 0.007) and individuals of Malay ethnicity (10.6% vs. 3.5%,

p = 0.025) diagnosed with AAN compared to AN.

Table 1 details the baseline characteristics at baseline for patients with AN and AAN and admission information.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of patients diagnosed with AAN relative to the total number of cases of AN and AAN for each year of the study period. Between 2010 and 2020, an increasing proportion of patients was diagnosed with AAN relative to the total number of cases of AN and AAN per year.

3.1. Weight variables and menstrual status

There was no significant difference in the duration, amount or rate of weight loss between adolescents with AN or AAN. Adolescents with AAN were more likely to be premorbidly overweight (32.2% vs. 5.5%, p < 0.001). Adolescents with AAN were also less likely to present with secondary amenorrhea (57% vs. 39.5%, p = <0.001).

3.2. Admission rate and reasons for admission

Adolescents with AAN were less likely to be admitted at first presentation compared to adolescents with AN (81.4% vs. 61%,

p < 0.001) Adolescents with AAN were more likely to be admitted for self-harm or suicide ideation (14% vs. 1.5%,

p < 0.001), and less likely to be admitted for bradycardia (21.2% vs. 7%,

p = 0.004) and hypotension (7% vs. 0%,

p = 0.125) but higher rates of syncope (12.8% vs. 6.6%,

p = 0.032) compared to AN. Adolescents with AAN also had shorter durations of inpatient stay(

p < 0.001)

Table 1 outlines the rates and reasons for admission in adolescents with AN and AAN.

3.3. Psychological measures

There was significantly higher proportion of adolescents with AAN presenting with depression, deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation (

p < 0.05 for all analyses). Purging was more common among adolescents with AAN (45.1% vs. 14.8%,

p < 0.001). There was a trend towards worse EDE-Q in all domains amongst adolescents with AAN with shape concern in EDE-Q being significantly higher in AAN cases (

p = 0.043).

Table 2 outlines the baseline psychological characteristics for adolescents with AAN and AN.

3.4. Associations between weight variables and markers of illness severity

Lower presenting %mBMI was associated with lower heart rate (β = 0.248 [CI 0.047 to 0.449];

P = 0.016), lower systolic blood pressure (β = 0.610 [CI 0.302 to 0.918];

p = <0.001), higher (worse) EDE-Q weight concern scores (β = -5.231 [CI -10.013 to -0.450];

p = 0.03) and longer duration of admission (β = -1.033 [CI -1.646 to -0.419];

p = 0.001). There were no significant associations of amount of weight loss, rate of weight loss and duration of weight loss with markers of illness severity (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This is the first study in a multi-ethnic Asian population that characterises differences in physical and psychological characteristics on presentation between adolescents with AN and AAN. Our study found that males and adolescents of Malay ethnicity comprised a higher proportion of adolescents with AAN. Despite presenting at a normal or high body weight, adolescents with AAN can manifest with physical complications of malnutrition and had higher frequency of psychological co-morbidities compared to adolescents with AN.

Consistent with other studies [

2,

3,

14,

16], our study found patients with AAN presenting with lower rates of secondary amenorrhea as well as bradycardia and hypotension requiring admission for medical stabilisation despite having similar amount, duration, and rate of body weight as their AN counterparts. This does not mean that adolescents with AAN do not suffer from complications of malnutrition as approximately half of our adolescent sample with AAN required admission for medical stabilisation. Interestingly, we also noted that adolescents with AAN were also more likely to present with syncope, despite having a higher systolic blood pressure, heart rate and no significant postural blood pressure changes compared to adolescents with AN. Given the increasing numbers of patients presenting with AAN, it is important for healthcare providers to screen for a history of weight loss and restrictive eating in adolescents with normal or higher body weight presenting with postural giddiness and syncope.

Similar to the study by Garber et al. [

14], we found that %mBMI at presentation was associated with lower heart rate and worse EDE-Q scores. However, we did not find similar associations with amount, duration or rate of weight loss as found in two other studies. This may be explained by our study that looks at a wider spectrum of illness with both inpatient and outpatient presentations in the cohort. We also do not have data on recent weight loss which has been shown to be associated with bradycardia.

Our study found that Asian adolescents with AAN experienced higher rates of depression, self-harm and suicidal ideation at presentation with a greater proportion requiring admission for psychological safety reasons. This is in contrast with the systematic review that did not find an increase in non-ED related psychopathology amongst patients with AAN [

2,

14,

16]. Clinically, we have observed adolescents with AAN presenting to care for evaluation of their mood issues, self-harm and suicidal ideations rather than for evaluation of their weight loss. This may affect the increased proportion of non-ED psychopathology amongst adolescents with AAN in our study.

In terms of ED psychopathology, we noted a trend towards worse EDE-Q scores on all domains with significantly increased scores in shape concern amongst adolescents with AAN which replicates other existing research which is consistent with findings from other studies [

2,

14,

16]. Concerningly, our study also found more Asian adolescents with AAN to be engaged with purging behaviour compared to cases with AN. This is in contrast to the study by Sawyer et al. that found similar rates of purging amongst AAN and AN [

16].

Our study found a higher percentage of males and Malays among the AAN subgroup. This observation appears to mirror the higher rates of obesity amongst males and amongst the Malay ethnicity in Singapore [

29]. Many shared risk factors have been identified between obesity and EDs, including body dissatisfaction, dieting, weight control behaviours and low self-esteem. Studies have shown that adolescents with adverse childhood experiences, which includes bullying and body-related difficulties have higher odds of developing AAN [

10]. The association between overweight and eating disorders thus emphasizes the need for a holistic and non-stigmatising approach to adolescent obesity programs and public health prevention programs.

The retrospective nature of this study presented several inherent limitations. Data recorded in the electronic medical record was not always complete and dependent on the original clinical documentation. Routine administration of EDE-Q started from 2016 in the service which meant that patients who presented prior to 2016 did not have EDE-Q data recorded. This may affect the generalizability of the results obtained.

Strengths of our study included this being the first study to investigate the differences in presentation of a large cohort of a multi-ethnic population of Asian adolescents with AAN and AN and the inclusion of inpatient and outpatient cases.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights how AN and AAN present differently in Asians with males and Malay ethnicity presenting more commonly with AAN than AN. Adolescents with AAN present less frequently with features of medical instability requiring admission compared to adolescents with AN. However, adolescents with AAN present more frequently with psychological safety concerns requiring admission in our study. We also found higher rates of depression and self-harm with worse eating disorder psychopathology and purging behaviours in AAN cases. These findings are instructive in guiding the identification and management of Asian adolescents with suspected AAN.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.S.E., E.E.T. and C.D.; methodology, C.C.S.E., E.E.T. and C.D.; formal analysis, C.C.S.E., E.E.T. and M.E.H.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E.T.; writing—review and editing, C.C.S.E., E.E.T, B.K.K., M.E.H.M.L. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research project was approved by Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB reference number:2016/2571) with waiver of consent approved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Singapore Health Services (CIRB reference number:2016/2571). Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to collection of routine clinical data for audit of clinical services.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to collection of routine clinical data for audit of clinical services.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the complexity of the dataset with different phases of implementation and the need for informed interpretation but are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Eating disorder team members comprising of adolescent physicians, nurses, psychologists, dietitians and medical social workers and families coping with their loved one suffering from eating disoders.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harrop, E.N.; Mensinger, J.L.; Moore, M.; Lindhorst, T. Restrictive eating disorders in higher weight persons: A systematic review of atypical anorexia nervosa prevalence and consecutive admission literature. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1328–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, B.T.; Hagan, K.E.; Lockwood, C. A systematic review comparing atypical anorexia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 56, 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitelaw, M.; Gilbertson, H.; Lee, K.J.; Sawyer, S.M. Restrictive Eating Disorders Among Adolescent Inpatients. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e758–e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association., A.P. Association., A.P. and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ed. t. Edition. A: 2013, Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, R.; Hardy, K.K.; Wilson, J.L.; Lock, J.D. Are diagnostic criteria for eating disorders markers of medical severity? Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1193–e1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, S.F.; McKenzie, N.; Hehn, R.; Monge, M.C.; Kapphahn, C.J.; Mammel, K.A.; Callahan, S.T.; Sigel, E.J.; Bravender, T.; Romano, M.; et al. Predictors of Outcome at 1 Year in Adolescents With DSM-5 Restrictive Eating Disorders: Report of the National Eating Disorders Quality Improvement Collaborative. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2014, 55, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keery, H.; LeMay-Russell, S.; Barnes, T.L.; Eckhardt, S.; Peterson, C.B.; Lesser, J.; Gorrell, S.; Le Grange, D. Attributes of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Carlson, J.L.; Golden, N.H.; Long, J.; Murray, S.B.; Peebles, R. Comparisons of bone density and body composition among adolescents with anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, M.; Ghaderi, A.; Wolf-Arehult, M.; Ramklint, M. Overcontrolled, undercontrolled, and resilient personality styles among patients with eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, A.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Marcoux-Louie, G.; Singh, M.; Patten, S.B. Psychological characteristics and childhood adversity of adolescents with atypical anorexia nervosa versus anorexia nervosa. Eat. Disord. 2020, 30, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar-Lavie, I.; Segal, H.; Oryan, Z.; Halifa-Kurtzman, I.; Bar-Eyal, A.; Hadas, A.; Tamar, T.; Benaroya-Milshtein, N.; Fennig, S. Atypical anorexia nervosa: Rethinking the association between target weight and rehospitalization. Eat. Behav. 2022, 46, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Malizio, J. Eating disorders in adolescents: how does the DSM-5 change the diagnosis? International journal of adolescent medicine and health 2015, 27, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorr, M.; Drabkin, A.; Rothman, M.S.; Meenaghan, E.; Lashen, G.T.; Mascolo, M.; Watters, A.; Holmes, T.M.; Santoso, K.; Yu, E.W.; et al. Bone mineral density and estimated hip strength in men with anorexia nervosa, atypical anorexia nervosa and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Clin. Endocrinol. 2019, 90, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, A.K.; Cheng, J.; Accurso, E.C.; Adams, S.H.; Buckelew, S.M.; Kapphahn, C.J.; Kreiter, A.; Le Grange, D.; Machen, V.I.; Moscicki, A.-B.; et al. Weight Loss and Illness Severity in Adolescents With Atypical Anorexia Nervosa. PEDIATRICS 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, C.; Illingworth, S.; Cini, E.; Bhakta, D. Medical instability in typical and atypical adolescent anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Whitelaw, M.; Le Grange, D.; Yeo, M.; Hughes, E.K. Physical and Psychological Morbidity in Adolescents With Atypical Anorexia Nervosa. PEDIATRICS 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, K.N.; Schorr, M.; Bruno, A.G.; Bredella, M.A.; Lawson, E.A.; Gill, C.M.; Singhal, V.; Meenaghan, E.; Gerweck, A.V.; Slattery, M.; et al. Vertebral Volumetric Bone Density and Strength Are Impaired in Women With Low-Weight and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 102, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Rohde, P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanna, V.; Criscuolo, M.; Mereu, A.; Cinelli, G.; Marchetto, C.; Pasqualetti, P.; Tozzi, A.E.; Castiglioni, M.C.; Chianello, I.; Vicari, S. Restrictive eating disorders in children and adolescents: a comparison between clinical and psychopathological profiles. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2020, 26, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, I.; Giles, S.E.; Granero, R.; Agüera, Z.; Sánchez, I.; Sánchez-Gonzalez, J.; Jimenez-Murcia, S.; Fernandez-Aranda, F. Where does purging disorder lie on the symptomatologic and personality continuum when compared to other eating disorder subtypes? Implications for the DSM. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 30, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.M.; Dunne, P.E. The rise of eating disorders in Asia: a review. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, C.S.E.; Kelly, S.; Baeg, A.; Oh, J.Y.; Rajasegaran, K.; Davis, C. First presentation of restrictive early onset eating disorders in Asian children. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 54, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, M.; Accurso, E.C.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Le Grange, D. The Impact of DSM-5 on Eating Disorder Diagnoses. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 50, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board, H.P. , Anthropometric Study on School Children in Singapore. 2002.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 651: menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol 2015, 126, e143–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Management of Restrictive Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 71, 648–654. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Hong, W.J.N.; Zhang, S.L.; Quek, W.E.G.; Lim, J.K.E.; Oh, J.Y.; Rajasegaran, K.; Chew, C.S.E. Outcomes of a higher calorie inpatient refeeding protocol in Asian adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 54, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, K.M.; Phillips, K.E. Eating Disorder Examination–Questionnaire (EDE–Q): Norms for Clinical Sample of Female Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Biddle, S.; Chan, M.F.; Cheng, A.; Cheong, M.; Chong, Y.S.; Foo, L.L.; Lee, C.H.; Lim, S.C.; Ong, W.S.; et al. Health Promotion Board–Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Obesity. Singap. Med. J. 2015, 57, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).