Submitted:

13 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Motion Model and Parameter Identification of Vessel

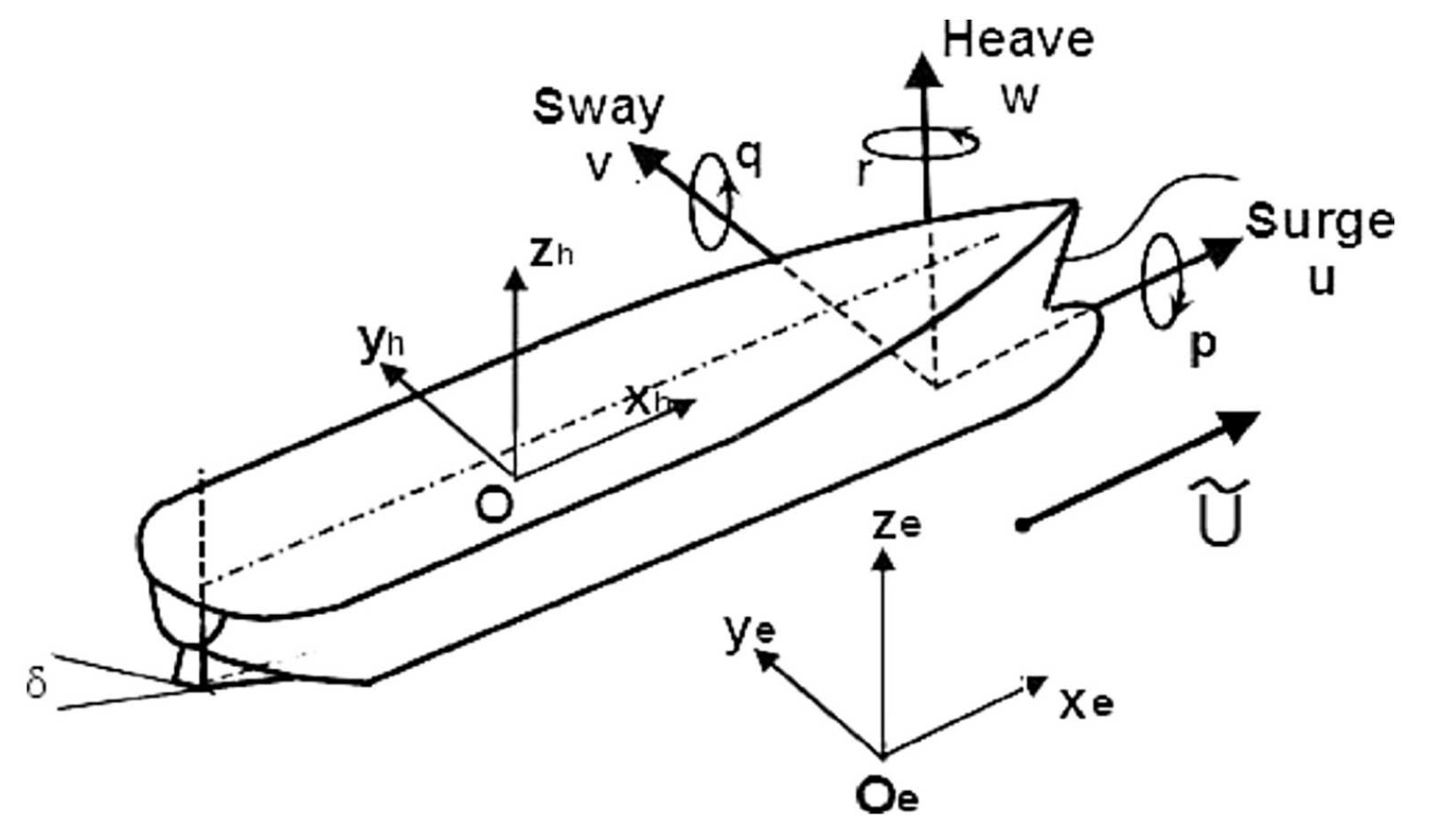

2.1. MMG Motion Model

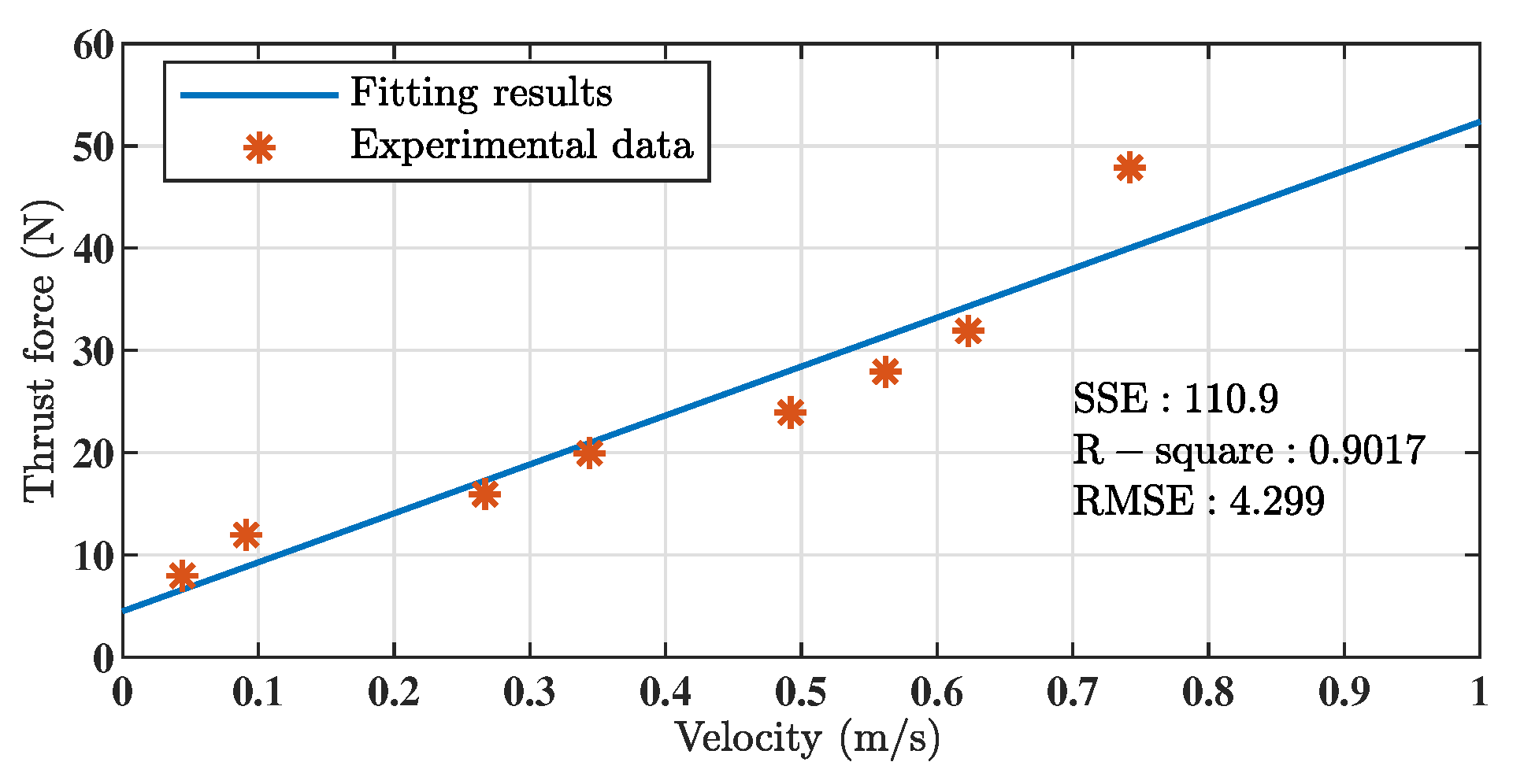

2.2. Parameter Identification

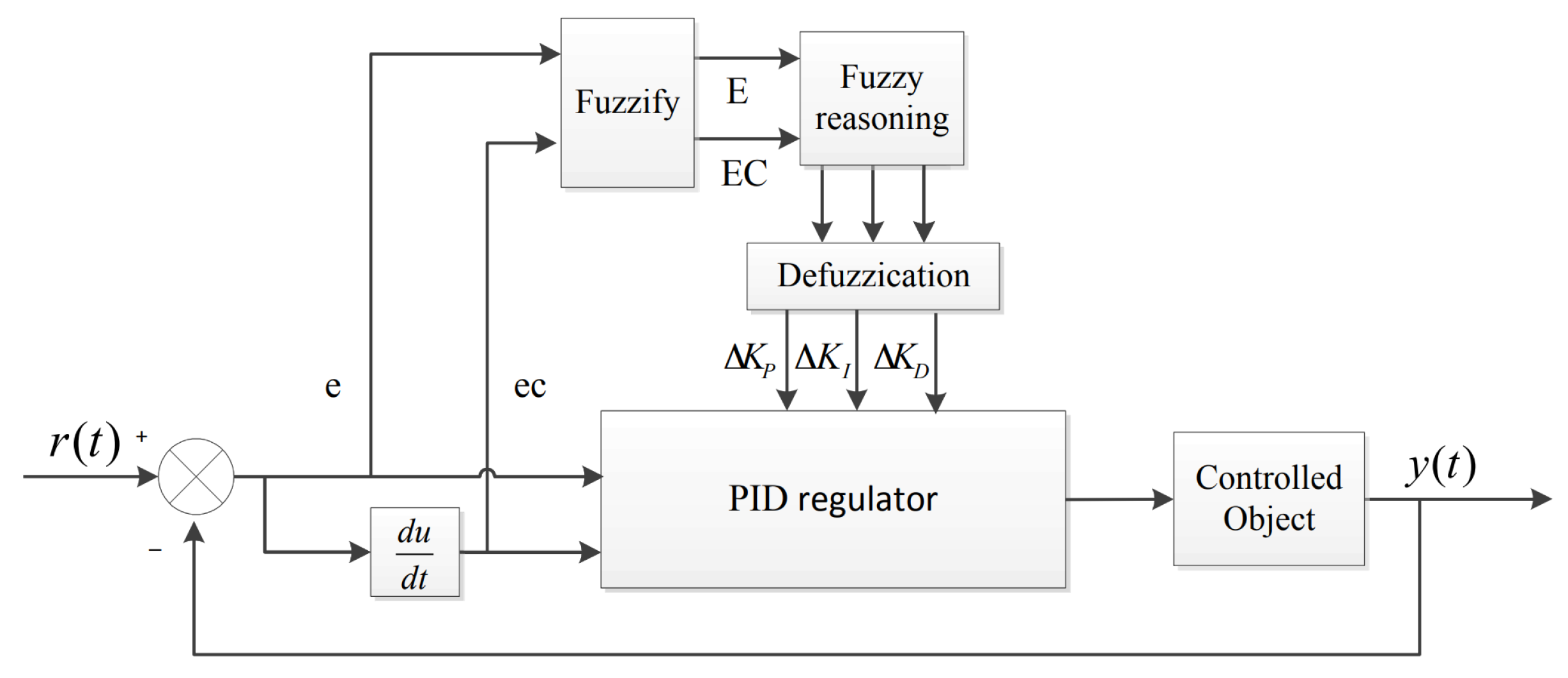

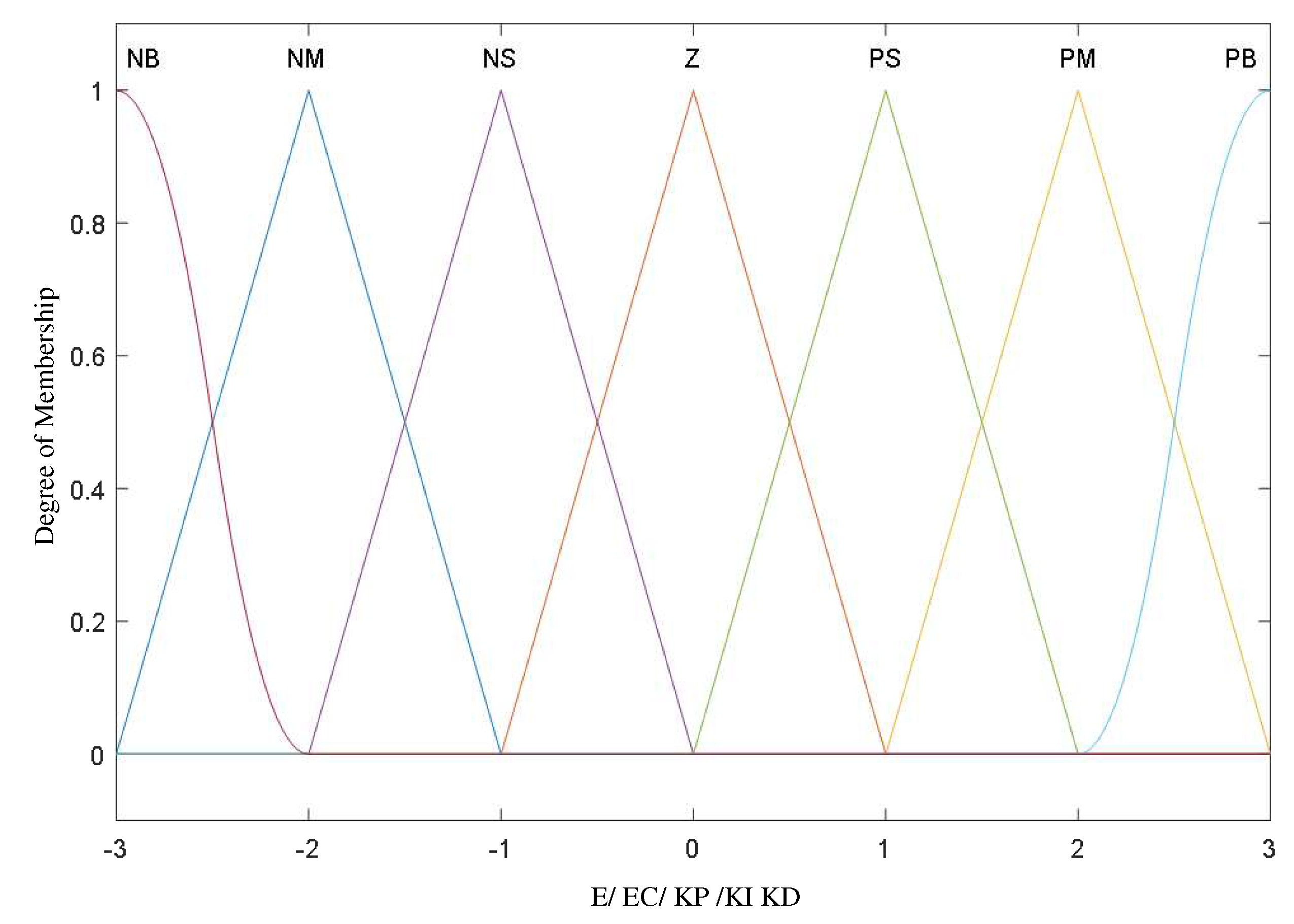

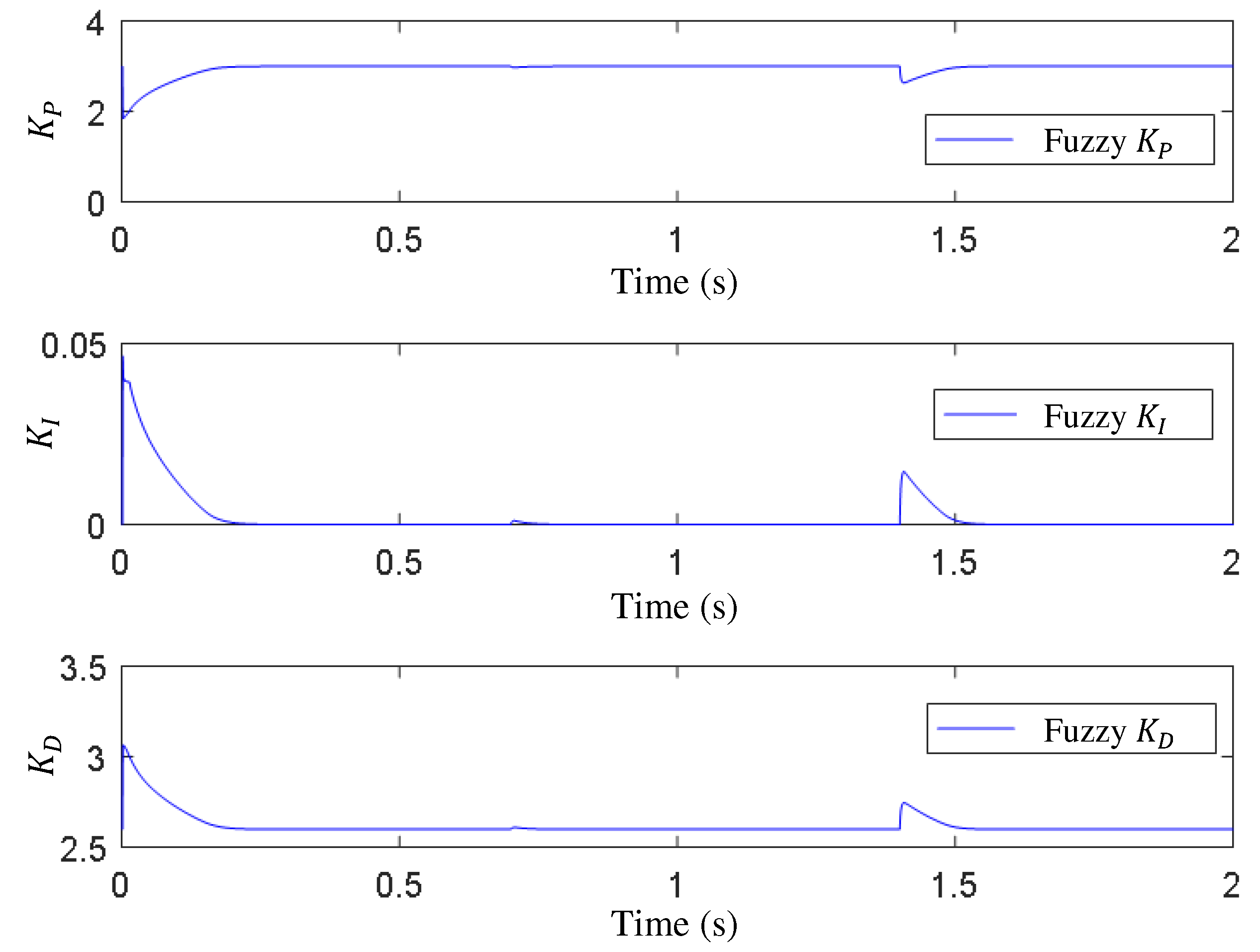

3. Trajectory Control

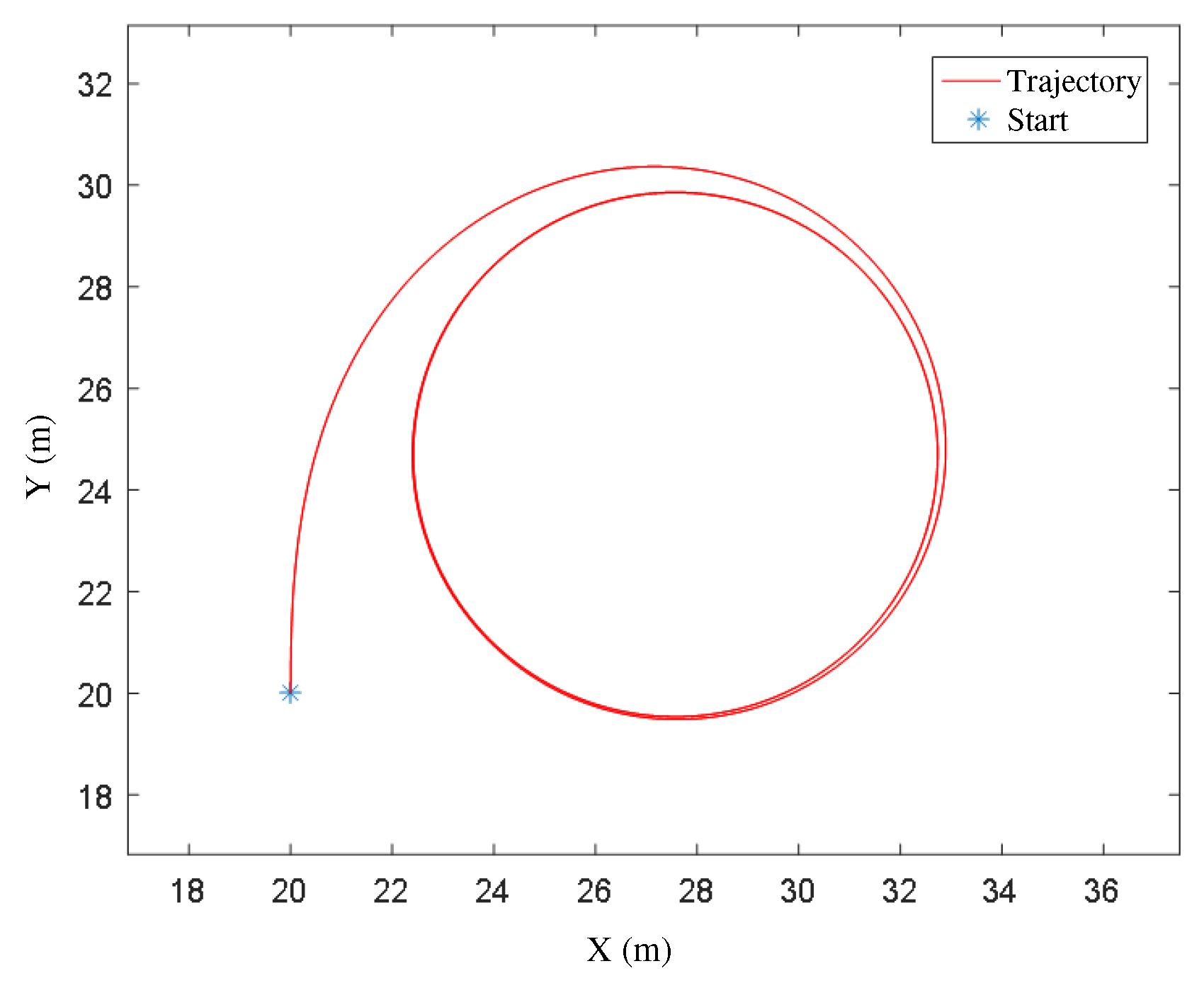

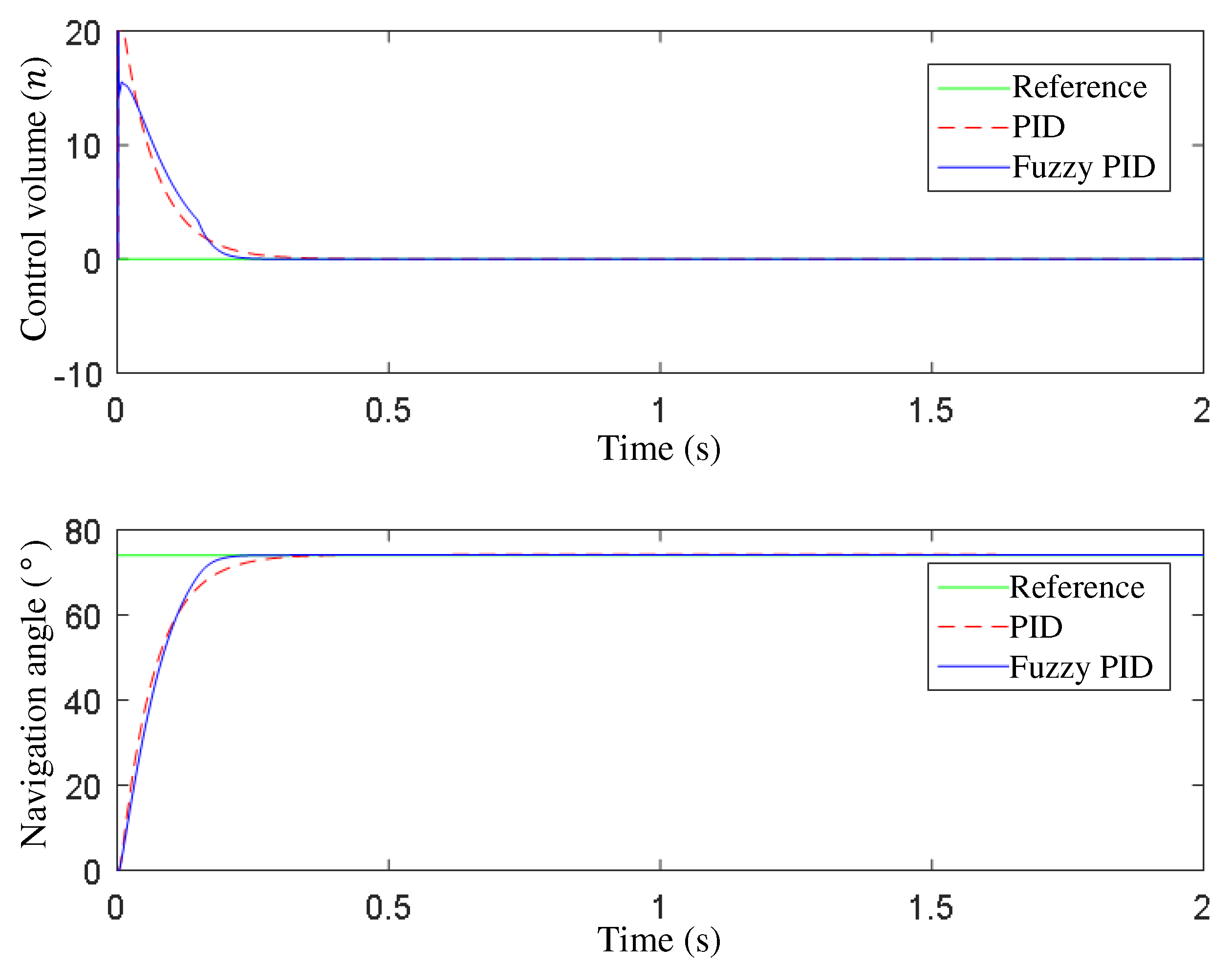

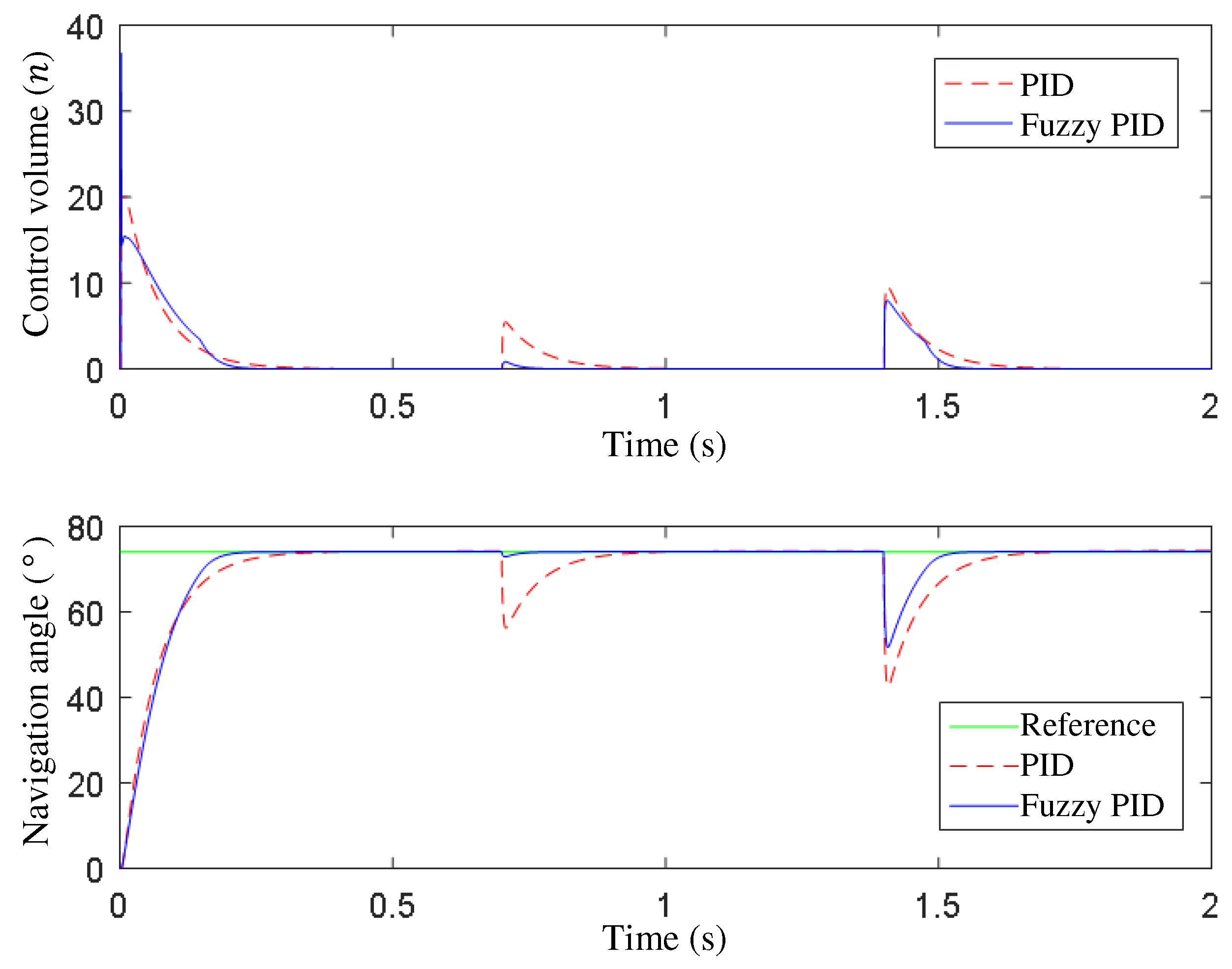

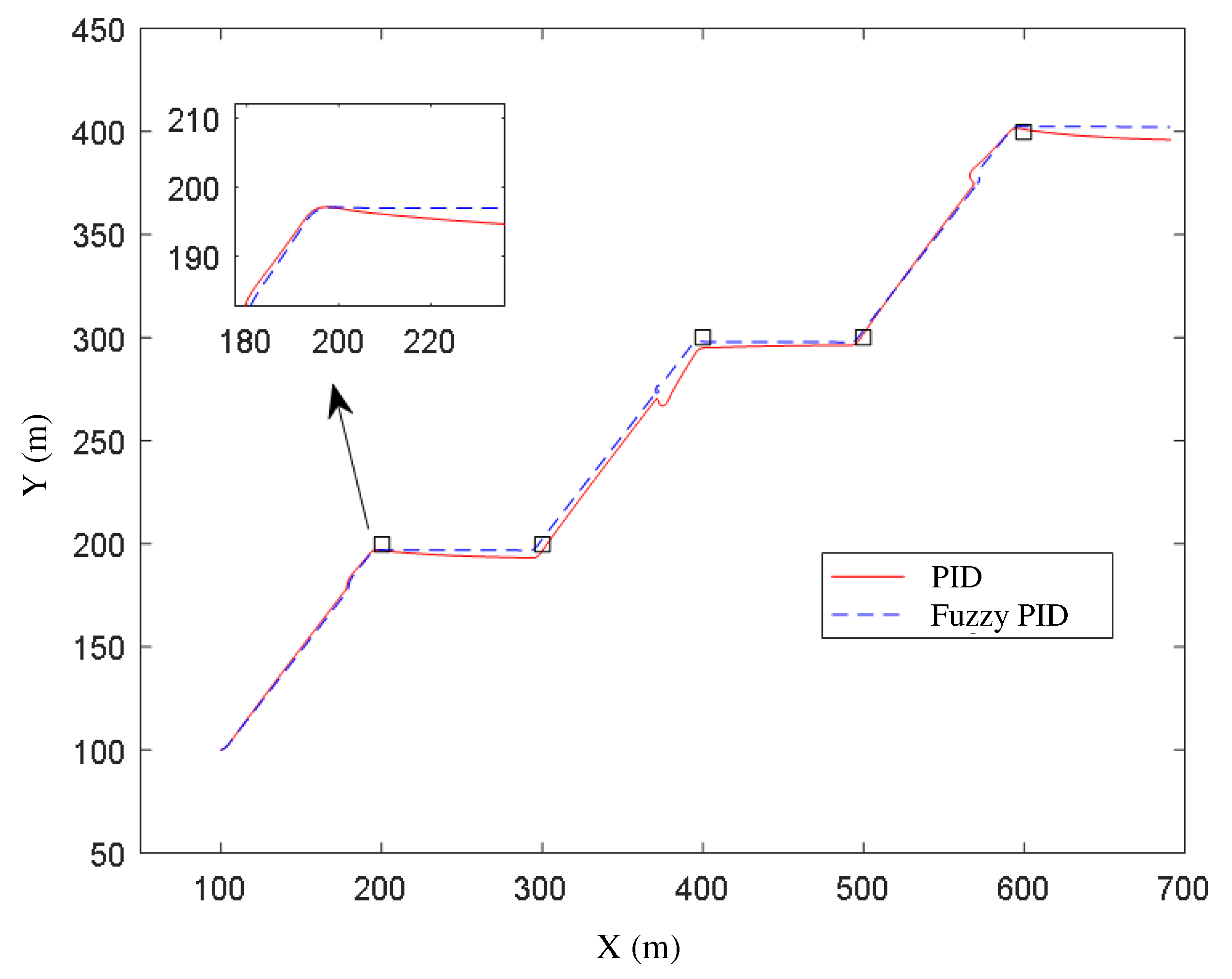

4. Simulation Results

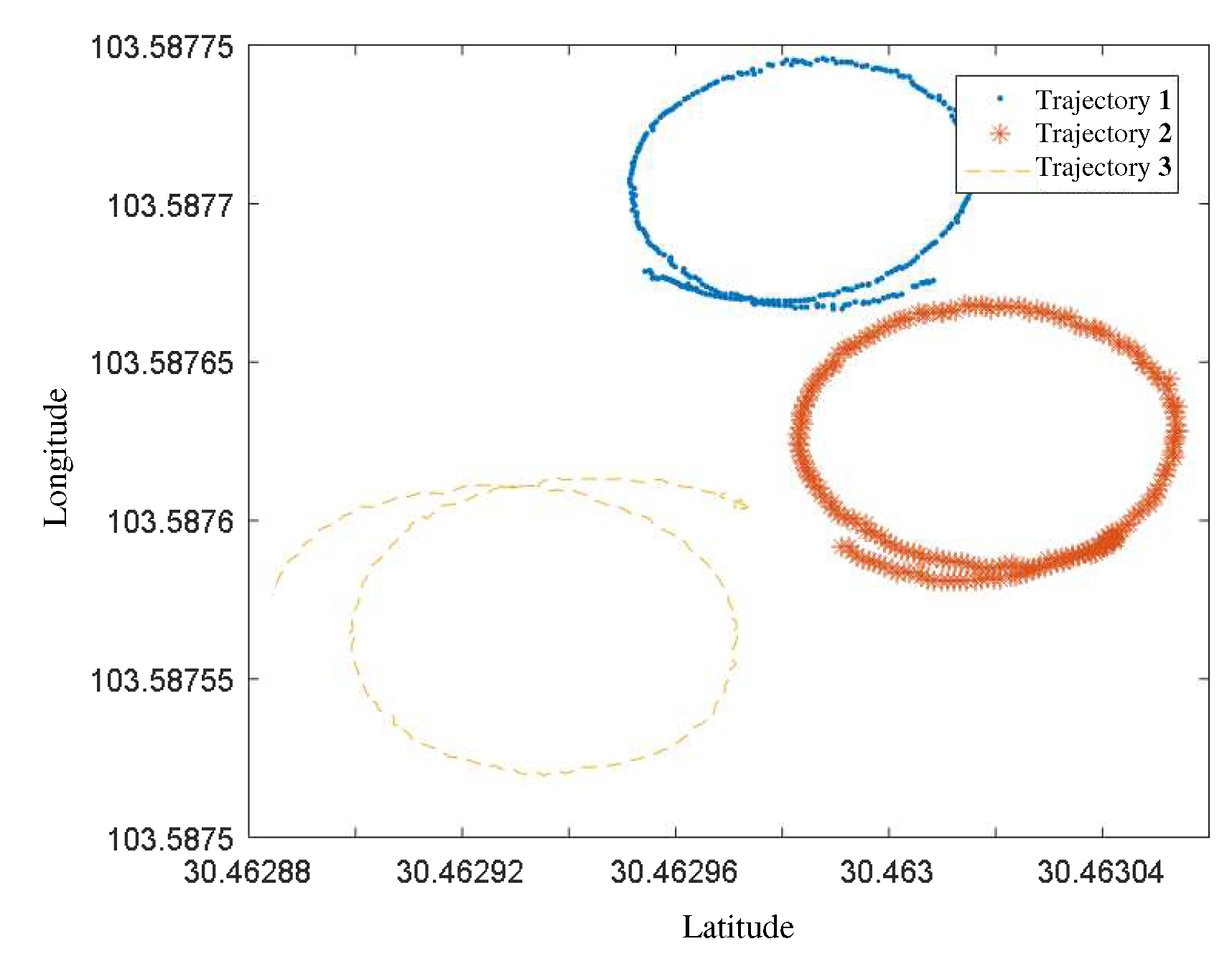

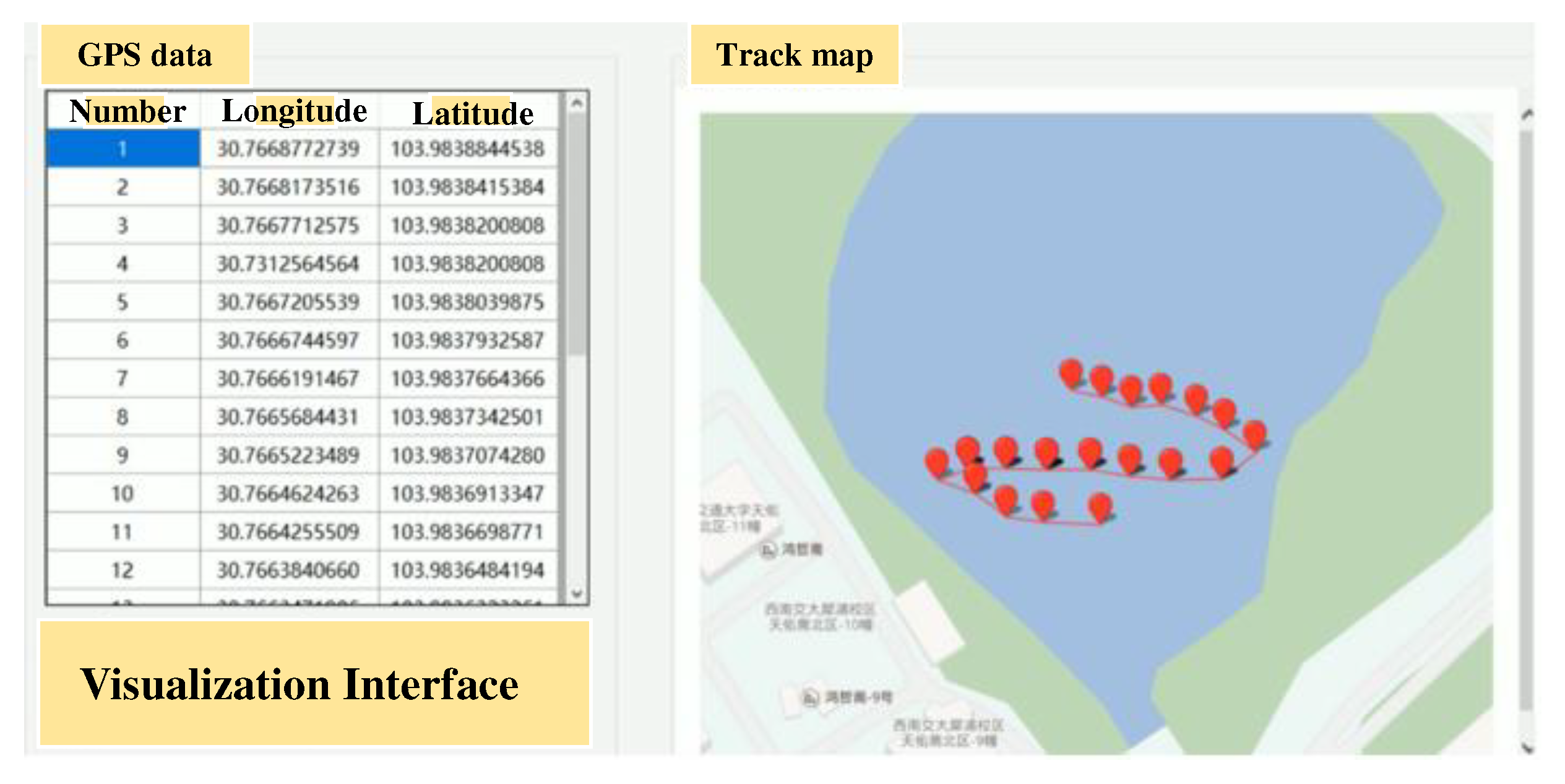

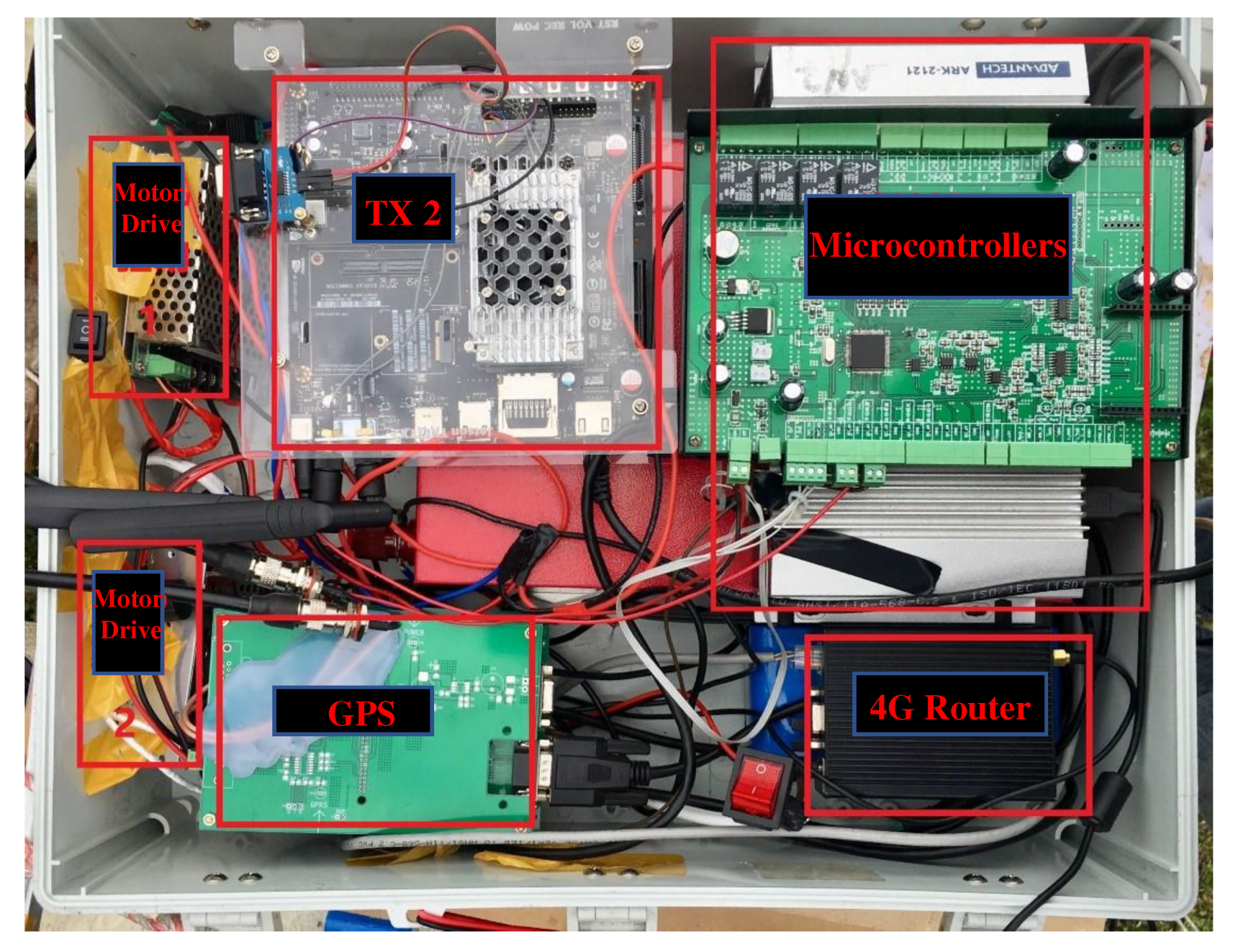

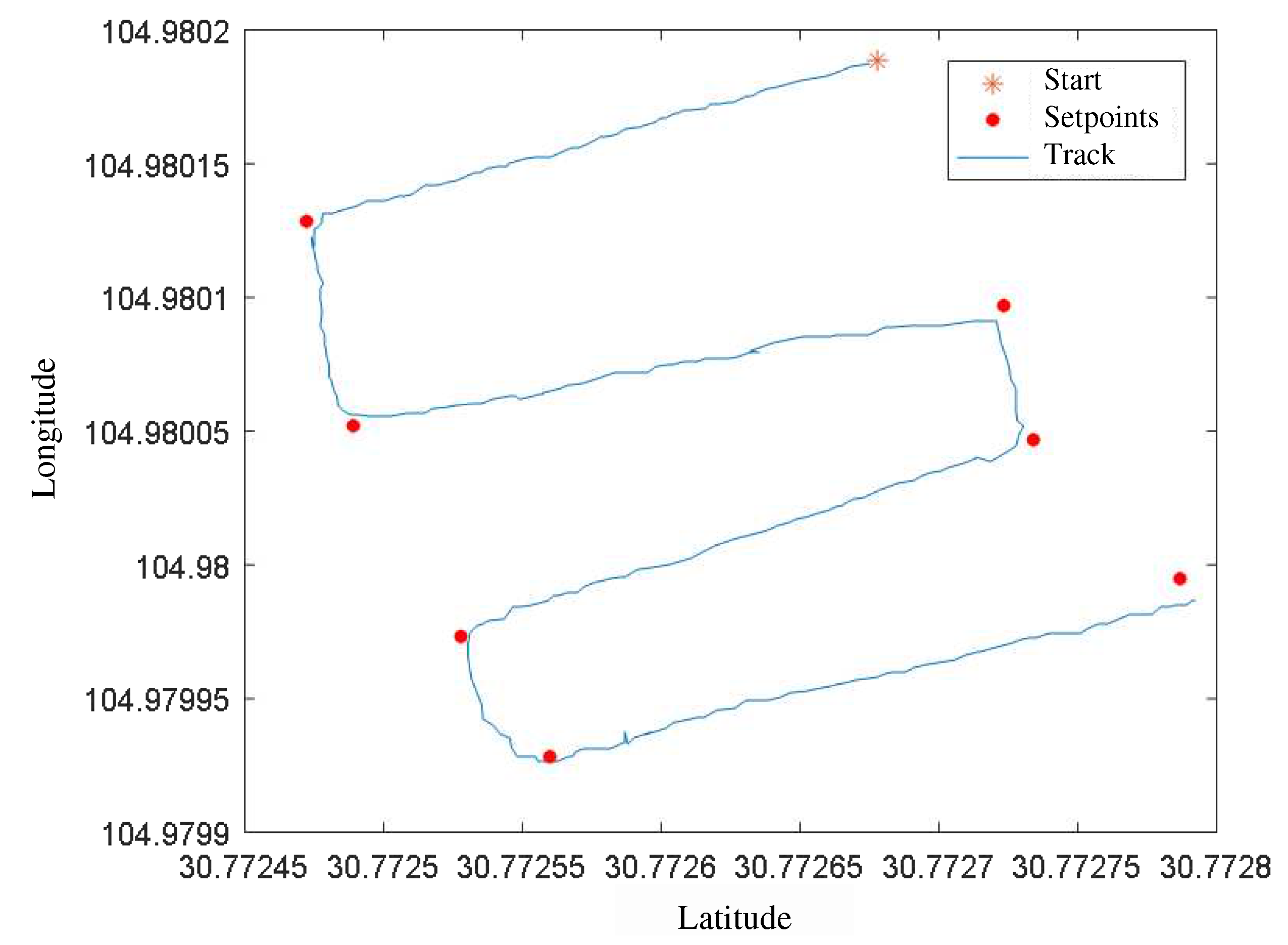

5. Analysis of Experimental Results

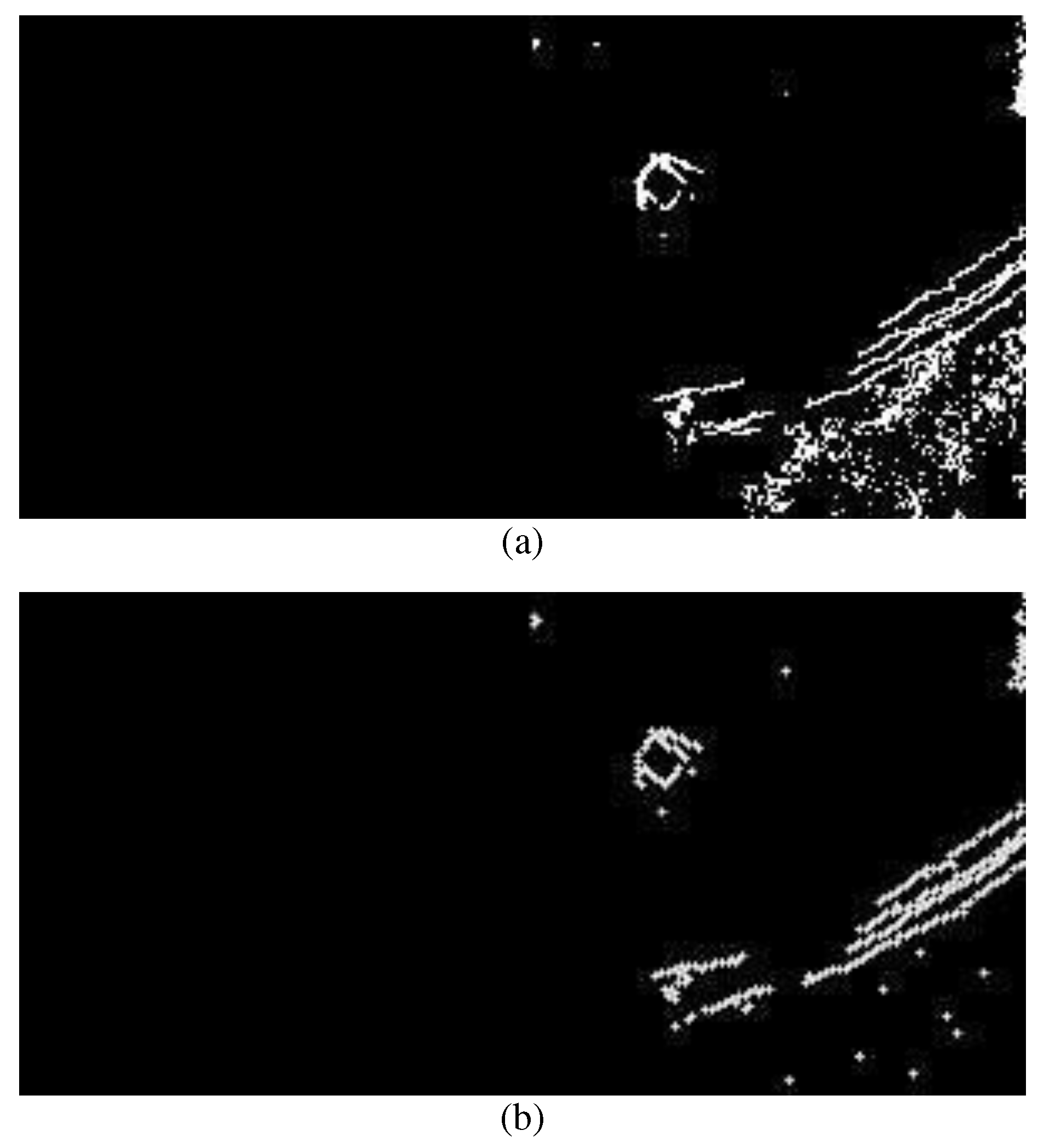

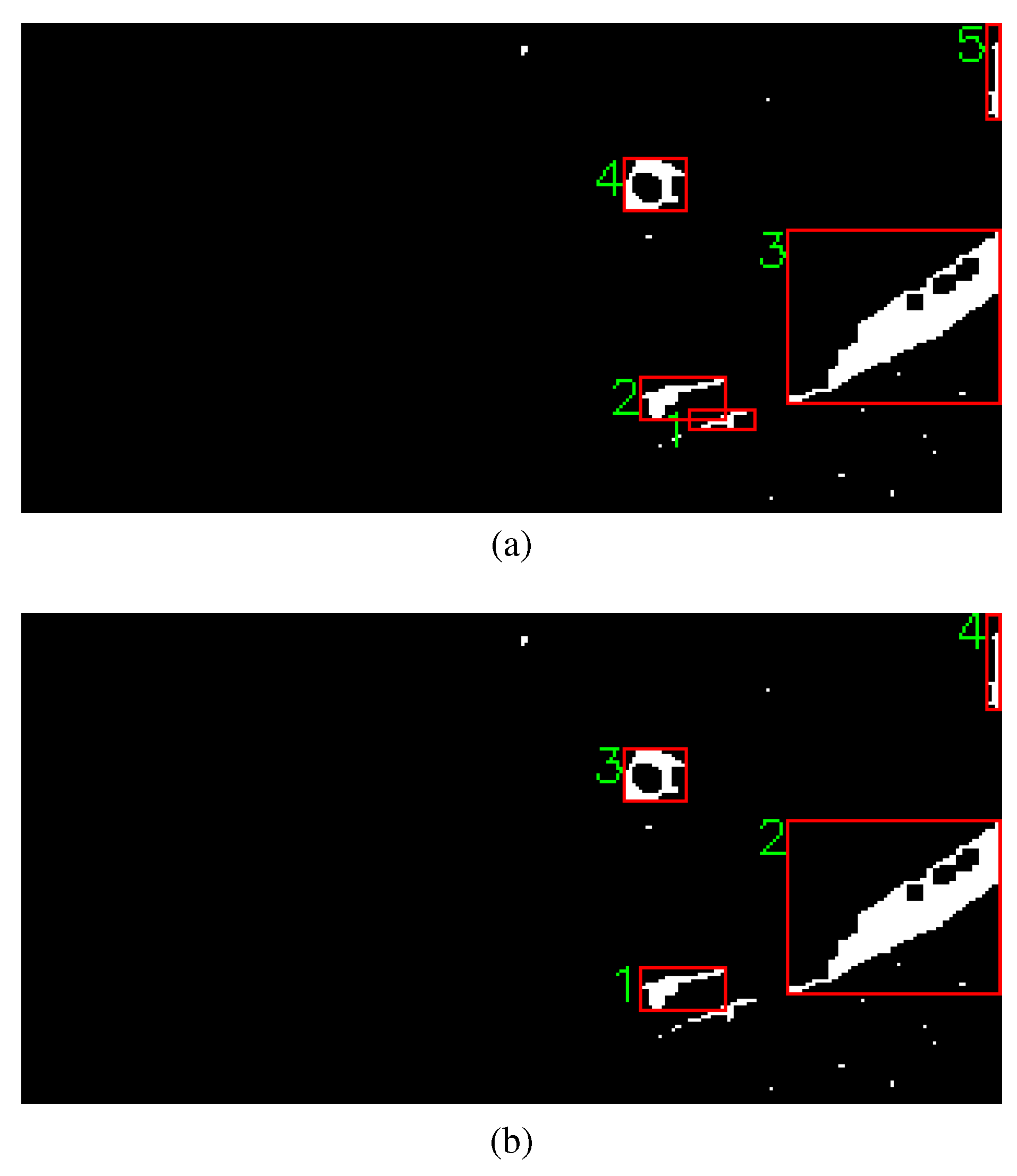

5.1. Obstacle Detection

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrera, C.; Padron, I.; Luis, F.; Llinas, O. Trends and challenges in unmanned surface vehicles (Usv): From survey to shipping. TransNav: International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousazadeh, H.; Jafarbiglu, H.; Abdolmaleki, H.; Omrani, E.; Monhaseri, F.; Abdollahzadeh, M.r.; Mohammadi-Aghdam, A.; Kiapei, A.; Salmani-Zakaria, Y.; Makhsoos, A. Developing a navigation, guidance and obstacle avoidance algorithm for an Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) by algorithms fusion. Ocean Engineering 2018, 159, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, H.; Yoshimura, Y. Introduction of MMG standard method for ship maneuvering predictions. Journal of marine science and technology 2015, 20, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Z. Ship Maneuvering Performance Prediction Based on MMG Model. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 452, 042046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, M. Prediction of manoeuvring abilities of 10000 DWT pod-driven coastal tanker. Ocean Eng. 2017, 136, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, P.; Li, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, K.; Zhou, X. Online modeling and prediction of maritime autonomous surface ship maneuvering motion under ocean waves. Ocean Engineering 2023, 276, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, X.; Pu, H.; Gu, J.; Xie, S.; Luo, J. Development of the USV ‘JingHai-I’and sea trials in the Southern Yellow Sea. Ocean engineering 2017, 131, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.; da Pires, P.S.; Moreira, M. Design Challenges of a Maritime Multipurpose Unmanned Vehicle. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 172, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mou, J.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, P. Comparison between the collision avoidance decision-making in theoretical research and navigation practices. Ocean Eng. 2021, 228, 108881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukas, O.F.; Kinaci, O.K.; Bal, S. System-based prediction of maneuvering performance of twin-propeller and twin-rudder ship using a modular mathematical model. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 84, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.; Boonen, R.; Vanierschot, M.; DeFilippo, M.; Robinette, P.; Slaets, P. Asymmetric Steering Hydrodynamics Identification of a Differential Drive Unmanned Surface Vessel⁎⁎This research was funded by Flanders Research Foundation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 207–212, 11th IFAC Conference on Control Applications in Marine Systems, Robotics, and Vehicles CAMS 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Bao, T.; Zheng, M.; Yang, X.; Song, L.; Mao, Y. Heading control of unmanned marine vehicles based on an improved robust adaptive fuzzy neural network control algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9704–9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horel, B. System-based modelling of a foiling catamaran. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. Design of control system of USV based on double propellers. 2013 IEEE International Conference of IEEE Region 10 (TENCON 2013), 2013, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, Y.J.; others. An autonomous control of fuzzy-PD controller for quadcopter. International Journal of Fuzzy Logic and Intelligent Systems 2017, 17, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; He, H. Dynamics-level finite-time fuzzy monocular visual servo of an unmanned surface vehicle. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2019, 67, 9648–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.L.; Paez, J.; Quintero, C.; Yime, E.; Cabrera, J. Design and control of an unmanned surface vehicle for environmental monitoring applications. 2016 IEEE Colombian Conference on Robotics and Automation (CCRA), 2016, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Asvadi, A.; Premebida, C.; Peixoto, P.; Nunes, U. 3D Lidar-based static and moving obstacle detection in driving environments: An approach based on voxels and multi-region ground planes. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 83, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliot, N.; Richard, P.L.; Montambault, S. LineScout power line robot: Characterization of a UTM-30LX LIDAR system for obstacle detection. 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2012, pp. 4327–4334. [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.; Aaltonen, J.; Koskinen, K.T. Path-following with lidar-based obstacle avoidance of an unmanned surface vehicle in harbor conditions. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2020, 25, 1812–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stateczny, A.; Burdziakowski, P. Universal autonomous control and management system for multipurpose unmanned surface vessel. Polish Maritime Research 2019, 26, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfain, B.; Drews, P.; You, C.; Barulic, M.; Velev, O.; Tsiotras, P.; Rehg, J.M. Autorally: An open platform for aggressive autonomous driving. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2019, 39, 26–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Han, X. Numerical investigation on underwater towed system dynamics using a novel hydrodynamic model. Ocean Engineering 2022, 247, 110632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; You, R.; Ma, Y.; Li, H. Temperature and velocity characteristics of rotating turbulent boundary layers under non-isothermal conditions. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 065138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, B.; Fei, Q. Curve Path Following Based on Improved Line-of-Sight Algorithm for USV. 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 3801–3806.

- Motora, S. On the measurement of added mass and added moment of inertia for ship motions Part 2. Added mass Abstract for the longitudinal motions. Journal of Zosen Kiokai 1960, 1960, a59–a62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, J. Coastal SLAM with marine radar for USV operation in GPS-restricted situations. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2019, 44, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrbin, N.H. Theory and Observation on the Use of a Mathematical Model for Ship Maneuvering in Deep and Confined Water. Proc. 8th Symposium on naval Hydrodynamics, 1977.

- Guo, M.; Guo, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Z. Fusion of ship perceptual information for electronic navigational chart and radar images based on deep learning. The Journal of Navigation 2020, 73, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of marine craft hydrodynamics and motion control; John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Fossen, T.I.; Breivik, M.; Skjetne, R. Line-of-sight path following of underactuated marine craft. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2003, 36, 211–216, 6th IFAC Conference on Manoeuvring and Control of Marine Craft (MCMC 2003), Girona, Spain, 17-19 September, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamari, S.M.; Narm, H.G.; Mollaee, H. Fractional-order fuzzy PID controller design on buck converter with antlion optimization algorithm. IET Control Theory & Applications 2022, 16, 340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. A geometrically nonlinear analysis method for offshore renewable energy systems—Examples of offshore wind and wave devices. Ocean Engineering 2022, 250, 110930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basbas, H.; Liu, Y.C.; Laghrouche, S.; Hilairet, M.; Plestan, F. Review on Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Models for Nonlinear Control Design. Energies 2022, 15, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.G.; Xu, W.D.; Wang, J.L.; Park, J.H.; Yan, H. BLF-based neuroadaptive fault-tolerant control for nonlinear vehicular platoon with time-varying fault directions and distance restrictions. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 12388–12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Y. Formation tracking of underactuated unmanned surface vehicles with connectivity maintenance and collision avoidance under velocity constraints. Ocean Engineering 2022, 265, 112698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Direction | x-Axial | y-Axial | z-Axial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity | u | v | w |

| Rotation angle | |||

| Angular velocity | p | q | r |

| Forces | X | Y | Z |

| Torque | K | M | N |

| Symbol | Description | Value/Unit |

|---|---|---|

| m | Unmanned vessel mass | 67.40 kg |

| L | Length | 1.235 m |

| B | Width | 0.956 m |

| d | Full load draft | 0.168 m |

| Thruster to the center distance | 0.34 m |

| e | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | NB | NM | NS | Z | PS | PM | PB |

| NB | PB | PB | PM | PM | PS | Z | Z |

| NM | PB | PB | PM | PS | PS | Z | NS |

| NS | PM | PM | PM | PS | Z | NS | NS |

| Z | PM | PM | PS | Z | NS | NM | NM |

| PS | PS | PS | Z | NS | NS | NM | NM |

| PM | PS | Z | NS | NM | NM | NM | NB |

| PB | Z | Z | NM | NM | NM | NB | NB |

| e | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | NB | NM | NS | Z | PS | PM | PB |

| NB | NB | NB | NM | NM | NS | Z | Z |

| NM | NB | NB | NM | NS | NS | Z | Z |

| NS | NB | PM | NS | NS | Z | PS | PS |

| Z | NM | NM | NS | Z | PS | PM | PM |

| PS | NM | NS | Z | PS | PS | PM | PB |

| PM | Z | Z | PS | PS | PM | PB | PB |

| PB | Z | Z | PM | PM | PM | PB | PB |

| e | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ec | NB | NM | NS | Z | PS | PM | PB |

| NB | PS | NS | NB | NB | NB | NM | PS |

| NM | PS | NS | NB | NM | NM | NS | Z |

| NS | Z | NS | NM | NM | NS | NS | Z |

| Z | Z | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | Z |

| PS | Z | Z | Z | Z | Z | Z | Z |

| PM | PB | NS | PS | PS | PS | PS | PB |

| PB | PB | PM | PM | PM | PS | PS | PB |

| Point No. | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30°46’21.6403" | 104°58’48.6782" |

| 2 | 30°46’20.9004" | 104°58’48.4626" |

| 3 | 30°46’20.9601" | 104°58’48.1879" |

| 4 | 30°46’21.8029" | 104°58’48.3499" |

| 5 | 30°46’21.8427" | 104°58’48.1684" |

| 6 | 30°46’21.0995" | 104°58’47.9035" |

| 7 | 30°46’21.2156" | 104°58’47.7418" |

| 8 | 30°46’22.0319" | 104°58’47.9819" |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).