1. Introduction

Threats over global warming linked to carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions from human activity have recently become salient [

1], which are received growing attentions by academics, media, and politicians [

2]. Countries are actively adopting carbon reduction action and may introduce significant limits on CO

2 emissions within the next decade to accomplish the 2°C or even 1.5°C control in the Paris climate agreement [

1,

3]. Previous research has documented that the carbon emissions trading has significant effects on firm-level outcomes (e.g. innovation, performance and stock returns) [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, the literature widely neglects its influence on corporate financialization.

This study aims to explore how carbon emissions trading affects the financialization of non-financial companies (NFC). Corporate financialization can be defined as NFC increase investment in financial assets while reducing productive investment [

8]. The financialization of NFC has become a common phenomenon in emerging markets. Taking China as an example, the disproportionately high growth beyond real economic needs of China’s financial sector has enabled financial assets to bring substantial profits to enterprises [

9], which exacerbates the profitability gap between the financial sector and the non-financial sector, leading NFC are forced to invest in more profitable financial assets due to the downturn in entities. However, existing research showed that financialization makes the surplus capital of NFC increasingly used for speculation and arbitrage instead of their main businesses [

8], such as innovation or production improvement, thereby reducing the company’s core business potential future profitability [

10,

11], which may cause a vicious circle of “low profit - financialization - lower future profitability”.

At the same time, the possible impact of carbon emissions trading on corporate financialization is inconclusive. As a typical environmental regulation, carbon emissions trading can not only further damage NFC’s profits through compliance costs, but also reduce the return on entities investment thereby weakening investor confidence in polluting companies, leading to underperformance of company stocks [

12,

13]. In this case, carbon emissions trading may exacerbate the financialization of NFC. However, the emissions trading may also reduce the financialization of NFC because, on the one hand, companies can directly obtain economic benefits by selling carbon emission rights. On the other hand, it can stimulate firms to disclose carbon information [

14], thus sending green signals to the market, which can attract more investors and ease the financial pressure of NFC. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the relationship between carbon emissions trading and the financialization of NFC.

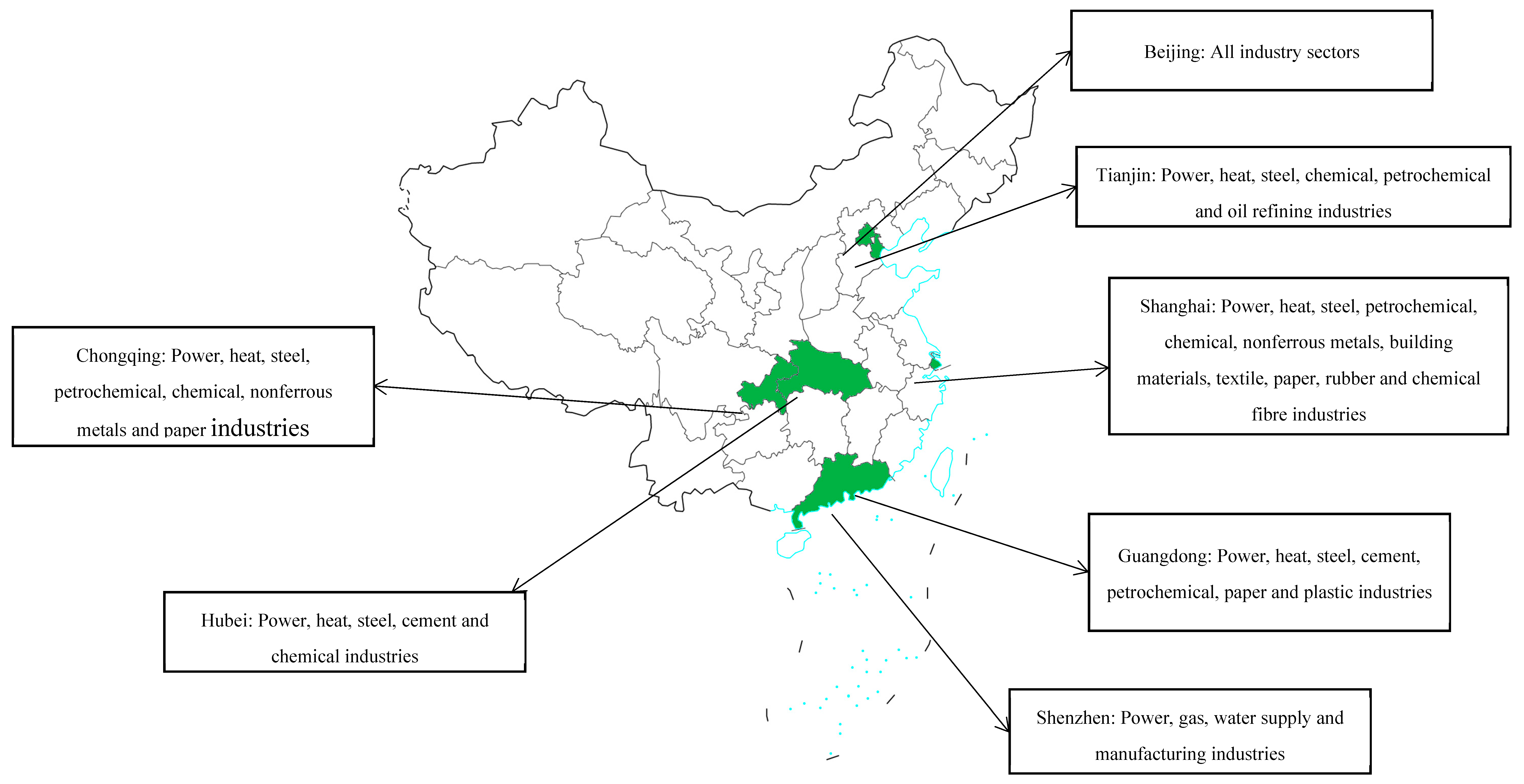

To conduct the examinations, we use China as a laboratory since it provides an ideal research context. First, as the world’s largest carbon emitters and emerging economies, China approved carbon emissions trading pilots in 7 provinces and cities since 2011 to promote the low-carbon economy transition, all of which launched trading in 2014. The implementation of carbon emissions trading pilots can be seen as a quasi-natural experiment for identifying the causal relationships between carbon emissions trading and financialization, whose strictly exogenous characteristic can prevent the possibly reverse shaping of carbon emissions trading by financialization. Second, the financialization of NFC and low-carbon development is a prominent social issue in China. China not only needs low-carbon economic transformation, but also rapid economic development. However, if carbon policies intensify the financialization of NFC, it will have a negative impact on the real economy in the future. Hence, studying the impact of carbon emissions trading on NFC financialization based on China context has practical significance.

Based on the differences between covered companies and non-covered ones before and after the carbon emissions trading pilots, we construct a difference-in-differences (DID) model and link it with the financialization index [

11,

15] to explore the impact of carbon emissions trading on the financialization of NFC. Using a sample of China listed NFC over the period of 2008 to 2020, we find that the financialization degree of NFC located in pilot areas significantly decreases, which still exists when we validate the robustness of the research. Hence, carbon emissions trading effectively inhibits the financialization of NFC.

Then, we explore the influence channel of carbon emissions trading. We find that carbon emissions trading can inhibit corporate financialization by reducing corporate financing constraints. The possible reason for this result is that, companies can gain direct economic benefits by selling carbon emissions rights. Li et al. [

14] also pointed out that carbon trading can improve enterprises’ transparency of carbon information, which can reduce information asymmetry and create an environmentally friendly corporate image, thereby alleviating financing distress.

Finally, we conduct several cross-sectional tests in terms of company ownership, company location and the degree of industry competition. We find that non-state-owned ownership, eastern location and high level of industry competition promotes the inhibitory effect of carbon emissions trading on financialization. Non-state-owned enterprises turn to holding more financial assets in order to survive in the context of the downturn in the entities economy leading they are more significantly affected by carbon trading policies. Whereas firms in eastern regions and highly competitive industries have to holding more financial assets under the combined pressure of competition and shrinking markets makes them very sensitive to the alleviation of financing constraints brought by carbon emissions trading.

Our research makes several contributions to the existing literature. First, to our best knowledge, we are the first to explore the relationship between carbon emissions trading and the financialization of non-financial companies. As one of the effective means to curb climate change, carbon emissions trading has attracted the attention of all countries. Previous research has proved carbon emissions trading has real effects on firms [

4,

5,

6,

7], but neglected its influence on corporate financialization. Our study extends the consequences of carbon emissions trading at the company level. Second, our results provide clear policy implications for low-carbon transitions in emerging markets. Nowadays, more than half of the world’s top 10 carbon dioxide emitters are emerging and developing countries [

16]. For them, non-financial firms not only are the main carbon emissions source, but also the key driver of economic development. Therefore, it is important to assess the impact of carbon emissions trading on the financialization of non-financial companies in emerging markets, because financialization is one of the obstacles to the corporate development. Taking the typical emerging market China as the background, we find that carbon emissions trading can reduce the financialization of non-financial companies, thereby promoting the low-carbon economy development, which can be referenced by other emerging markets.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 discusses the institutional background and hypothesis development.

Section 3 introduces the sample construction and research design.

Section 4 reports the empirical results, and

Section 5 presents the influence channels of carbon trading policies. Then, section 6 presents the further tests conducted.

Section 7 concludes.

4. Carbon Trading Policy and Corporate Financialization

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

We employ the OLS estimation to model (1) for exploring the impact of carbon trading policy on the financialization of non-financial firms.

Table 2 presents the regression results. Column (2) adds control variables to column (1).

From column (1), we find that the coefficient of Treati × Postt is negatively significant at the level of 1%, which shows that carbon trading policy effectively prevents the intensification of corporate financialization. After adding control variables, the coefficients of Treati × Postt is still negatively significant.

Surprisingly, the regression results are contrary to our hypothesis that carbon trading policy curbs the financialization of non-financial firms. Specifically, the carbon trading policy with compliance cost does not make managers invest in more financial products for liquidity reserving and losses compensation. On the contrary, companies in the pilot covered industries cut down the financial assets investment after carbon trading launching.

For the control variables, LnSize and Lev are both negatively related to Fini,t showing that large company scale and adequate financing can reduce enterprises’ willingness of financialization. SS also presents negatively significant. Hence, strict internal management can prevent companies from investing in high-risk financial assets. However, LnAge is positively correlated with financialization, thus indicating that old non-financial companies may have to hold more financial assets to obtain liquidity and prevent profits from being squeezed by the financial industry.

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

The key logic of the DID model (1) is that the difference between the treatment group and the control group is caused by the ETS pilot instead of other factors. Specifically, the firms in treatment group and the control group should maintain the parallel financialization trend before the ETS pilot, but present significant differences after it. For proving the parallel trend, we reference Qi et al. [

6] to examine the dynamic effects of the enactment of the ETS pilot on financialization of non-financial firms through construct new independent variable, which is the product of the dummy variable Treat

i and the dummy variable of corresponding year (the value is 1 in the corresponding year, and 0 otherwise), and build the following model (2):

where the subscript i and t means company i and year t, respectively. Fin

i,t represents degree of financialization, which is measured by the ratio of financial assets to total assets, of company i in year t. pre3plus

i,t, pre3

i,t, pre2

i,t, pre1

i,t, im

i,t, post1

i,t, post2

i,t, post3

i,t and post3plus

i,t are is the product of the dummy variable Treat

i and the dummy variable of corresponding year. All other variables in model (2) are consistent with the model (1), whose explanation is not repeated for brief.

Table 3 shows result of parallel trend test. Column (2) adds control variables to column (1). We find that the coefficients prior to ETS pilot is insignificant thus verifying the parallel financialization trend between treatment group and control group. After pilot, the results signify that carbon trading policy curb the degree of financialization of treatment group enterprises whose inhibition effect still exists more than three years after the pilot. Hence, the carbon trading policy effectively and long-term deceases the tendency of Chinese non-financial companies to invest in financial assets.

4.3. Placebo Test

To verify whether there is possible results bias, we conduct a placebo test by randomly selecting 15% of the 3,367 companies in full sample as the dummy treatment group while the remaining firms setting as the control group. Then, we do the random sampling with replacement three times to generate Dummy treat1, Dummy treat2 and Dummy treat3 to replace the variable Treati in model (1) and repeat the regression. If the estimated coefficient of Dummy treat1, Dummy treat2 and Dummy treat3 are still significant, it will show that our original estimation result is likely to be biased, that is the change of financialization is affected by other policy changes or random factors, and vice versa.

Table 4 presents the results of the placebo test whose dependent variable is Fin

i,t. Column (1), (2) and (3) show the results of Dummy treat

1, Dummy treat

2 and Dummy treat

3, respectively. We find that the all dummy treat is not significant. As a result, the decreasing of the financialization of non-financial firms brought by the carbon trading policy.

4.4. PSM-DID Estimate

We also extend the DID model to a DID model linking propensity score matching (PSM) method in order to improve the reliability of the research results. The control group still is firms, which are not covered by ETS pilot, but through propensity score matching based on companies’ characteristics, we can get a more suitable control group than randomly selecting [

38]. According to Qi et al. [

6], we use nearest-neighbour matching to estimate PSM-DID whose results of the propensity score matching balance test are shown in Appendix 2. To ensure a sufficient number of observations, we match each processing group company with three control group companies.

Table 5 shows the estimation results of PSM-DID. Column (2) adds control variables to the column (1). From the results, we find that the test results are all same as the original results, which prove that our research results are reliable.

5. Influence Channels of Carbon Trading Policy

The analysis in

Section 4 presents that the carbon trading policy effectively suppress the financialization of non-financial firms in China. What is the influencing channel of this policy curbs corporate financialization? On the one hand, enterprises can obtain economic benefits by selling carbon emission rights. On the other hand, carbon trading policies can stimulate companies to disclose more carbon emission information [

14]. Based on the theory of information asymmetry, carbon information disclosure improves corporate transparency and reduces information asymmetry while transmitting to outside investors a green signal that the company attaches importance to environmental protection, which can attract more investors thereby obtaining external financial support. Through the above two analysis, it can be seen that the carbon trading policy may alleviate the financing constraints, who are precisely the important reasons for companies to expand financial asset holdings. Hence, we explore whether carbon trading policies can reduce the degree of corporate financialization by decreasing corporate financing constraints through model (3) and (4):

where model (3) is a benchmark DID model whose explained variable SA

i,t is the measurement of corporate financing constraints (Hadlock and Pierce, 2010). A higher SA

i,t indicates firms with higher financing constraints. Model (5) adds SA

i,t based on model (1). All other variables in model (3) and (4) are consistent with the model (1), whose explanation is not repeated for brief. The basic idea of the exploration of influence channels is that if β

1 in model (3) is significant, carbon trading policies can affect corporate financing constraints, and vice versa. In the case where β

1 in model (3) is significant, if α

1 and α

2 in model (4) are significant, and α

1 is significantly closer to 0 than β

1 in model (1), then the financing constraint is the channel through which carbon trading policy affects the company financialization, and vice versa.

The regression results are shown in

Table 6. All columns include control variables and fixed effects. Column (1), (2) and (3) show the results of model (1), (3) and (4), respectively. The significant negative coefficient of Treat

i × Post

t in column (2) indicates that the carbon trading policy eases the level of corporate financing constraints. The coefficient of SA

i,t in column (3) is significantly positive while Treat

i × Post

t is significantly negative and lower than the coefficient in the column (1), showing that carbon trading policies curb financialization of non-financial firms by alleviating corporate financing constraints.

6. Heterogeneity Analysis

Given that we find that carbon trading policy reduces the financialization of non-financial companies by easing financing constraints in the previous sections, do carbon trading policies have the same impact on companies with different characteristics? To address this issue, we explore the influence of heterogeneity on the inhibitory effect of carbon trading policy on enterprises with differences between the ownership structure, geographical locations and industry characteristics.

6.1. Ownership Heterogeneity

Company ownership has an impact on the financialization degree of the companies [

36]. Therefore, we explore the ownership heterogeneity impact on the inhibition effect of carbon trading policy.

We divide the full sample into state-owned enterprises (SOE) and non-state-owned enterprises (non SOE), which respectively include 11,194 observations and 17,406 observations, and reproduce the regression of model (1).

Table 7 shows the results of ownership heterogeneity. The results of SOE and non SOE are presented in column (1) and (2), respectively. From the results, the carbon trading policy only decrease the financialization of non-state non-financial enterprises.

The reasons of state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises choosing different financial asset holding strategies while facing carbon trading policies may be as follows. First, the natural political connection between state-owned enterprises and the government makes the it become the guarantor of state-owned enterprises. When non-financial state-owned enterprises are in financial distress due to lower profits, the government can help them get out of it by granting subsidies. Moreover, the connection between the government and the bank reduces the difficulty of financing for state-owned enterprises. Second, preventing major financial risks is one of the main strategies of the Chinese government. As a stable of area economic development and employment, state-owned enterprises may not be allowed to hold large amounts financial assets with high risks by government. Both of the above points may cause state-owned enterprises to maintain a low level of financialization before the carbon trading policies, thereby being not sensitive to the inhibitory effects of it. However, non-state-owned enterprises turn to holding more financial assets in order to survive in the context of the downturn in the entities economy leading they are more significantly affected by carbon trading policies.

6.2. Regional Heterogeneity

China is a large country with varying development levels of regional economic. Differences in regional macroeconomic factors can affect the company’s operating conditions, thereby changing their financial investment decisions [

39]. Hence, we verify whether regional heterogeneity affects the effectiveness of carbon trading policies.

Based on the location of the company, we divide the total sample into two sub-samples of companies located in the east and central and western regions’ companies, and perform model (1) on them.

Table 8 shows the results of regional heterogeneity. Column (1) and (2) show the results of Eastern region firms and central and western regions ones, respectively. From the results, the carbon trading policy only decrease the financialization of eastern region non-financial firms.

The reasons for this situation may be that, the rapid economic development in the eastern China results in a high-density distribution of firms, which increases the pressure of competition and financing difficulties in the east region. As a result, non-financial companies in the eastern region have to hold more financial assets under the dual pressure of competition and market shrinkage before the carbon trading policy, which makes they be sensitive to reduced financing constraints and additional benefits brought about by the carbon trading policy. However, for central and western regions’ companies, on the one hand, the low level of firms overlap makes the companies less competition pressure. On the other hand, the Chinese government has given more support policies to the central and western regions in order to achieve the strategic goal of common prosperity, which can reduce the difficulty of financing for enterprises in the central and western regions. Hence, low competition and relatively sufficient funds make companies in the central and western regions are not sensitive to direct or indirect benefit from carbon trading policies.

6.3. Industry Competition Heterogeneity

In this section, we verify the impact of industry competition on the effect of carbon trading policies. According the view of Rhoades [

40] and Tingvall and Poldahl [

41], this paper use Herfindahl index to measure the level of industry competition. We compute the average Herfindahl index of each industry from the sample start to ETS pilots trading launching based on total assets, and classifies the industries whose average Herfindahl index below the median as highly competitive industries, others are set as industries with less competition. Referring to the 2012 edition of the China Securities Regulatory Commission industry classification, we the divide the total sample into two sub-samples of companies in highly competitive industries and firms in non-high competition industries.

Table 9 shows the results of industry competition heterogeneity. Column (1) and (2) show the results of high competition industry firms and non-high competition industry firms, respectively.

Through the results, we find that the carbon trading policy only decrease the financialization of high competition non-financial firms. The plausible explanation is that in industries with low market competition, most companies have a certain degree of monopoly, which may make them have sufficient market control thereby reducing the pressures of financing and operating. In addition, industries with low market competition are mostly occupied by state-owned enterprises, whose close relationship with the government lead them not sensitive to the extra benefits caused by carbon trading policy. However, for companies in industries with a high degree of market competition, their investment decisions react more strongly to the extra benefits.

7. Conclusion

Reducing carbon emission plays an important role in alleviating global warming. At the same time, the trend of financialization of China's non-financial enterprises intensified. Nevertheless, the neglecting of the contradictions between environmental regulations and financialization in existing research leads the impact of carbon trading policy on financialization of non-financial firms unclear. Therefore, taking China emission trading scheme pilots as a quasi-natural experiment, we use the difference-in-differences model to study the impact of carbon trading policy on financialization of non-financial companies, which can effectively identify the causal relationship between carbon trading policies and corporate financialization and eliminate the influence of non-result related factors. In doing so, we expand the research of carbon trading policy influence on micro-company level and the influence factor of corporate financialization. In addition, our research results provide a policy reference for reduce the corporate financialization in emerging markets under low-carbon transition.

According to our results, carbon trading policy can effectively restrain the financialization of non-financial enterprises through reducing firms’ financing constraints. In parallel trend test, we find that the inhibition effect of ETS pilot on corporate financialization consistently remains significant. Our findings show robust validity even when (1) extending the DID model to a PSM-DID model to get a more appropriate control group and (2) using the placebo test to verify possible results bias. Finally, we conduct a cross-sectional test in terms of company ownership, company location and industry competition and find that carbon trading policy have a more significant mitigation on the financialization of (1) non-state-owned enterprise (2) eastern region companies (3) highly competitive industry firms.

In summary, emerging economies can achieve a win-win situation for low-carbon transition and stable economic development through carbon trading policies.