6.1. Building the Posterior Distribution

In Bayesian realm, the observed data,

is fixed while the state variable

and the parameter

are considered as random variables. In this setting, the Bayes’ theorem defines the posterior distribution as

where

, called the prior distribution, codifies our belief about the unknown parameter

before the data is observed and

, called the likelihood distribution, codifies all the information available regarding how the observed data

was obtained. From the Bayesian perspective, (

9) constitutes thean inverse problem which may be solved by using the

Maximum a posteriori (MAP), that is thean argument that maximizes the posterior (

), or the posterior mean (

) or posterior median, as the optimal value

of

.

Since we are dealing with count data, which by their very nature are events that occur between a given period of time, a Poisson process would be a natural and meaningful starting point for modeling and performing inference on the observed cases. However, count data, especially epidemiological observations, usually exhibit more variations than is implied by the Poisson distribution, pointing to inherent over-dispersion in the data. Such variations may be due to sampling, aggregation and environmental variability or a combination of both factors making count data to have inherent over-dispersion. It is therefore not possible that count epidemiological data portrays equal mean-variance relationship, as is contemplated by the Poisson distribution. In fact, [

124] posits that most commonly used approaches contemplates a quadratic mean-variance relationship. The mean-variance relationship in modeling count data, like epidemiological data, can adequately be described by the negative-binomial distribution as it has an additional parameter that permits the variance to be larger than the mean [

125,

126,

127]. Moreover, the negative binomial distribution is a mixture of the Poisson and Gamma distribution [

127,

128], a pointer to the fact that the Poisson distribution is still involved in the modelling even when the negative binomial distribution is used.

We assume that the observed data follows the negative binomial distribution with one dispersion parameter

and we write

where

p is the probability of success. The distribution has the form

where

It is noteworthy that is the additional variance allowed by the Negative Binomial distribution with respect to the Poison distribution, and that the parameter can be viewed as controlling the dispersion of the observed data.

We acknowledge that there are other forms of the Negative binomial distribution. For instance, [

49] achieved success in modelling COVID-19 and hospital demand in Mexico using a Negative binomial distribution with two over-dispersion parameters. This distribution was proposed by [

124]. However, in a model with numerous parameters to estimate as ours, it is our view that additional parameters would further increase the dimensionality of the already complex optimization problem.

We now construct the posterior distribution for the present multi-patched study. Using the already defined observed data and the variable

in the previous section, we assume that the observed cases of each patch follow a negative-binomial distribution with over-dispersion parameter (the number of failures before first success)

and success probabilities

where

is the theoretical mean of the negative binomial distribution which can be taken as patch

i incidence

With this setting in mind, we have that if

, represents the incidence in Patch

i observed in day

j with theoretical mean

, as in (

11), then we have that

Then the likelihood from Patch

i,

, corresponds to

Hence, the likelihood of the combined data from the n patches is given as .

To establish the prior distribution, we opt to define the joint prior distribution as the product of the marginal. That is, if we denote

, where

is the

ℓ-parameter associated to Patch

i, then

where

is the number of parameters for Patch

i.

The posterior distribution of the parameters from all the

n patches can thus be obtained as the product of (

9) and (

12) as (

9).

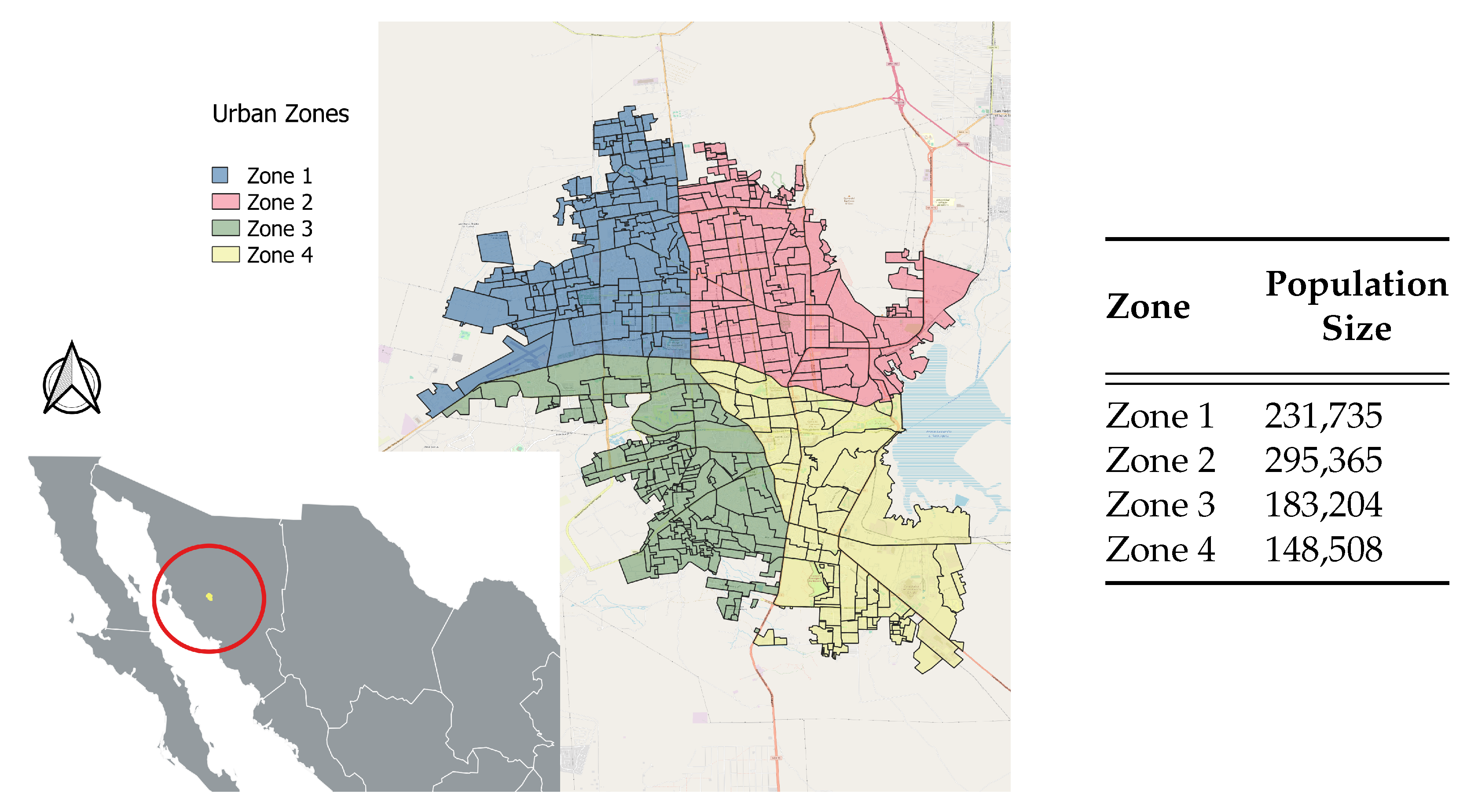

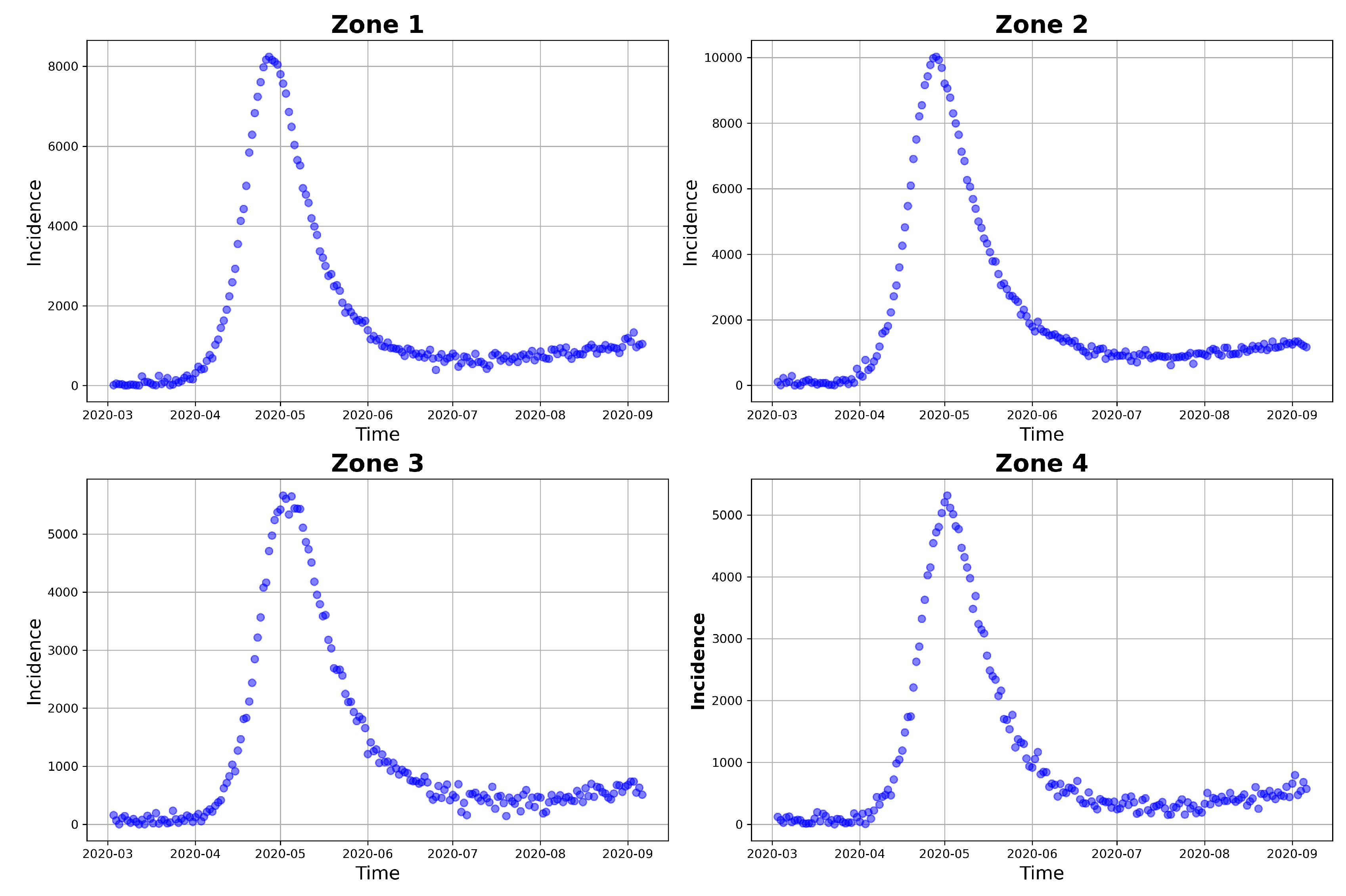

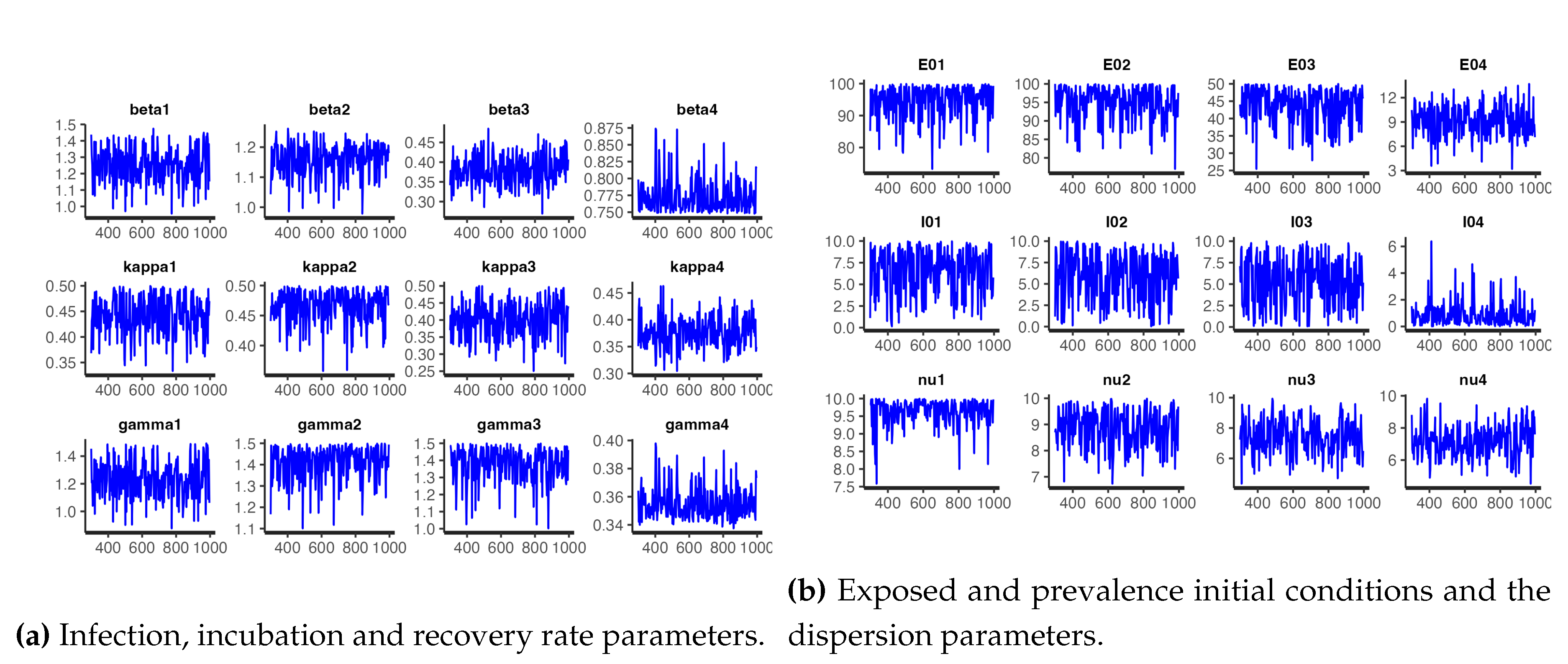

6.2. Results

We note, from the deterministic inversion section, that we are interested in estimating for each zone

i,

, the transmission, incubation and recovery rates

,

and

as well as the exposed, infected and incidence initial conditions

and

. For the Bayesian inference, also called probabilistic inversion, there is an addition of four over-dispersion parameters

, for each zone’s observed incidence data. The dispersion parameters can be loosely defined as the number of trials before we encounter the first successful infection in each zone. These parameters come with the negative binomial distribution, which we use as the distribution of the observed zonal incidences. We thus have, for the Bayesian inference in this section, a total of 24 parameters,

that we estimate.

An important problem that has been the topic of recent research, is the selection of adequate prior distributions, their corresponding hyperparameters and the delimitations of the parametric spaces of the parameters to be estimated [

129,

130,

131]. In this research, for the epidemiological parameters, we choose prior distributions with 95% of their body falling within the parametric spaces (upper and lower bounds) provided from COVID-19 literature as in

Table 2.

In this way, we use the following prior distributions for each of the parameters;

where the hyperparameters for the log Normal prior distributions of the contact parameters are

,

,

,

and

, while those for the exposed states’ initial conditions are

,

,

,

,

,

, and

,

. These prior probability distributions, which we have selected using the mentioned criteria, are versatile and allows for the assumption that some parameter values could occur with lower, equal or higher probability densities.

However, to avoid generalizations, it is imperative to perform a diagnostic analysis of the adequacy and correctness of the selected prior distributions before we begin sampling. These prior distributions should be in coherence with our expectations and correspond to the domain knowledge of each parameter as obtained from the deterministic inversion in the previous section. We desire priors that, in accordance with our deterministic inversion domain experience, permits every conceivable configuration of the data while excluding blatantly ludicrous scenarios.

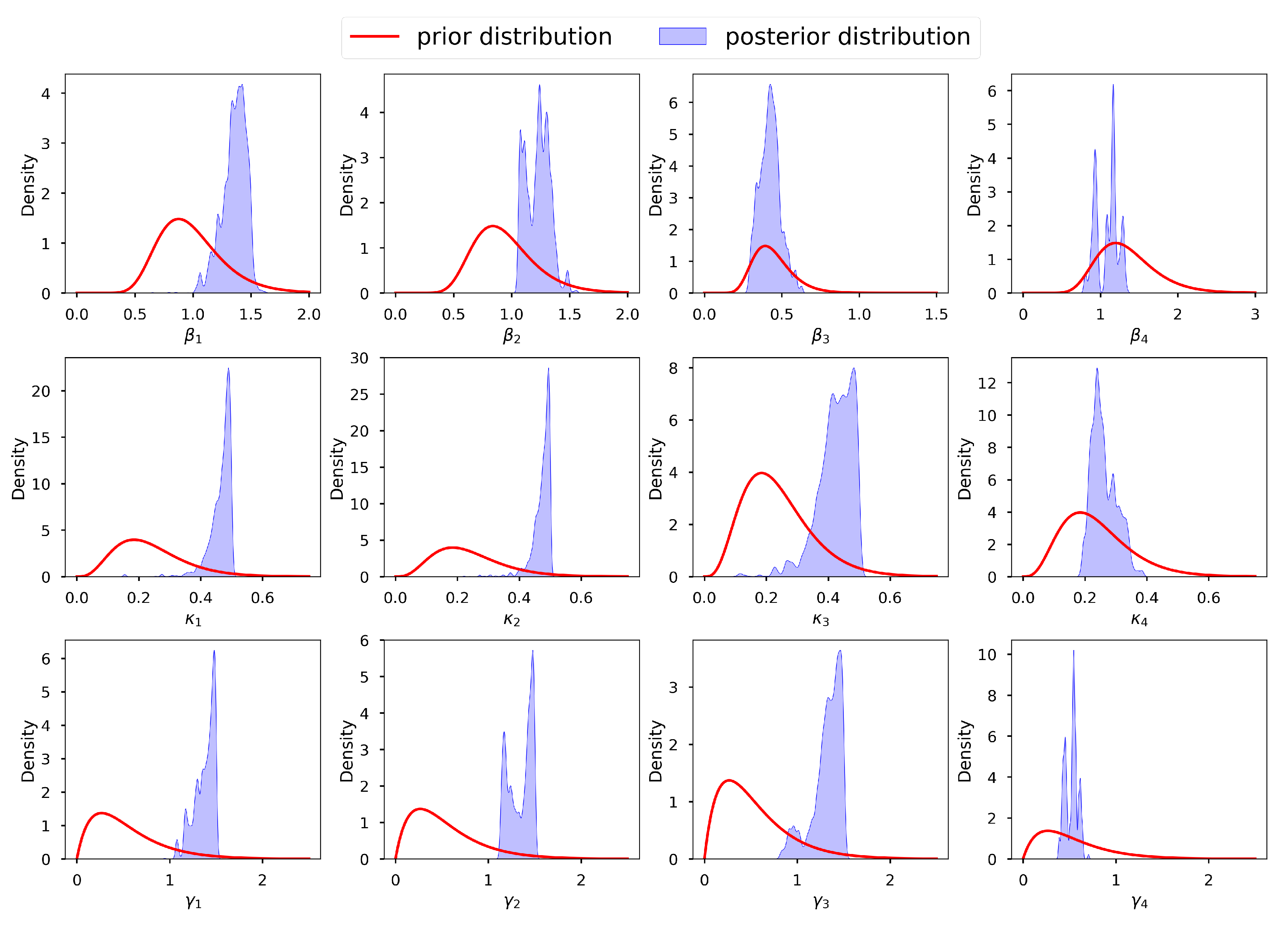

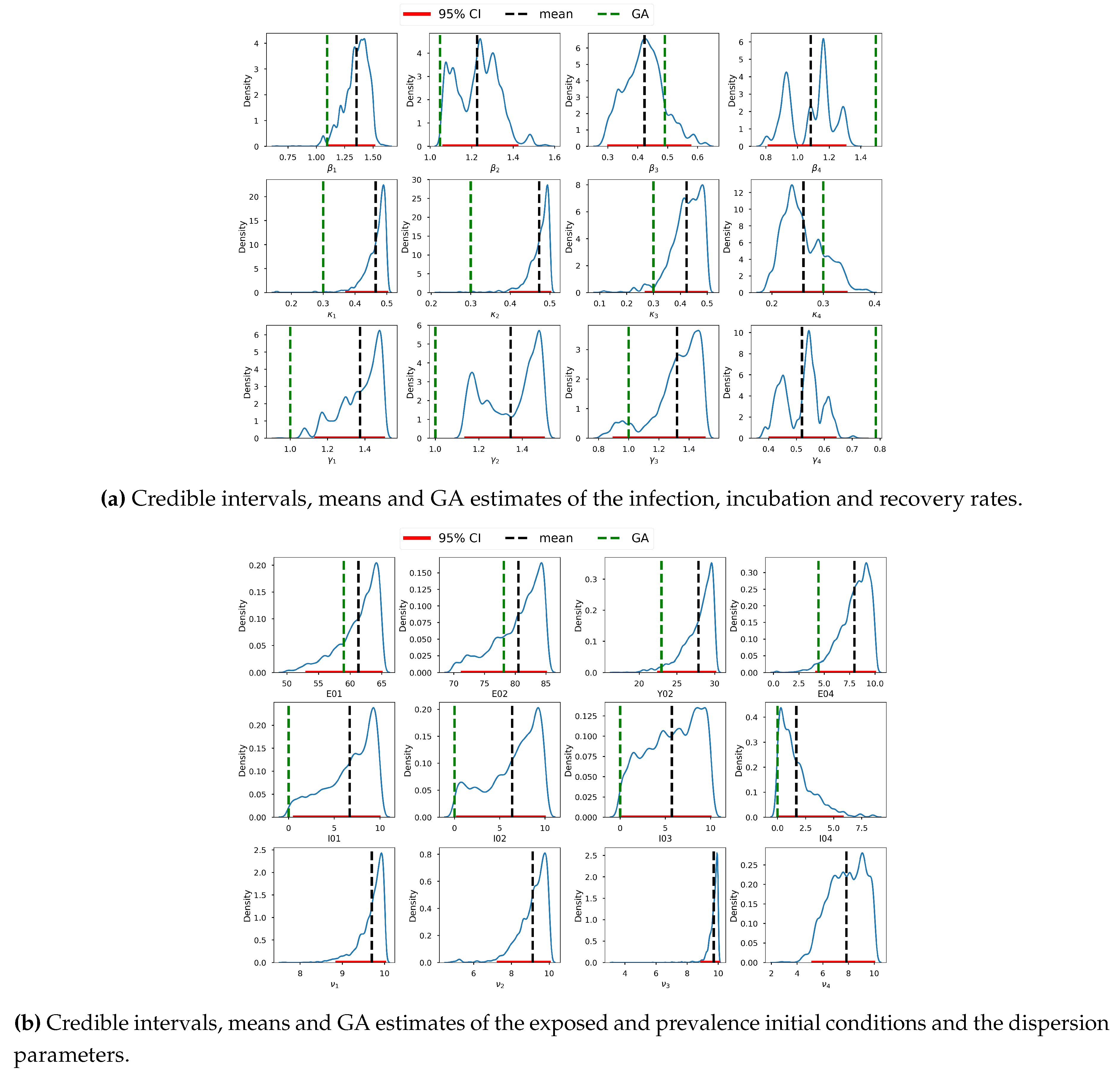

Figure 8 shows a graph of the selected prior distributions of the infection, incubation and recovery parameters, vis-à-vis the corresponding posterior distributions. Here we can observe that for most parameters we have allowed for low informative priors and the posterior distributions are within their respective prior probability support. This conforms with the suggestion by [

132], that the model should not be overly confined by the priors, which should instead be too wide to encompass a wide variety of situations and data that are incredibly improbable. We thus conclude that our selected prior distributions are adequate and are capable of regularizing our estimates to avoid non-identifiability. We acknowledge that [

131] also proposed an interesting criterion for selecting prior distributions together with their corresponding hyperparameters, based on parametric intervals. Applying the assumption of independence of the parameters, the joint prior distribution is

.

The likelihood for the four zonal incidence is

where,

is the total number of days for which we observe the incidence for each zone

;

is the

j-th observed incidence for zone

i, and

is the incidence of model (

1). The posterior distribution is thus given as

.

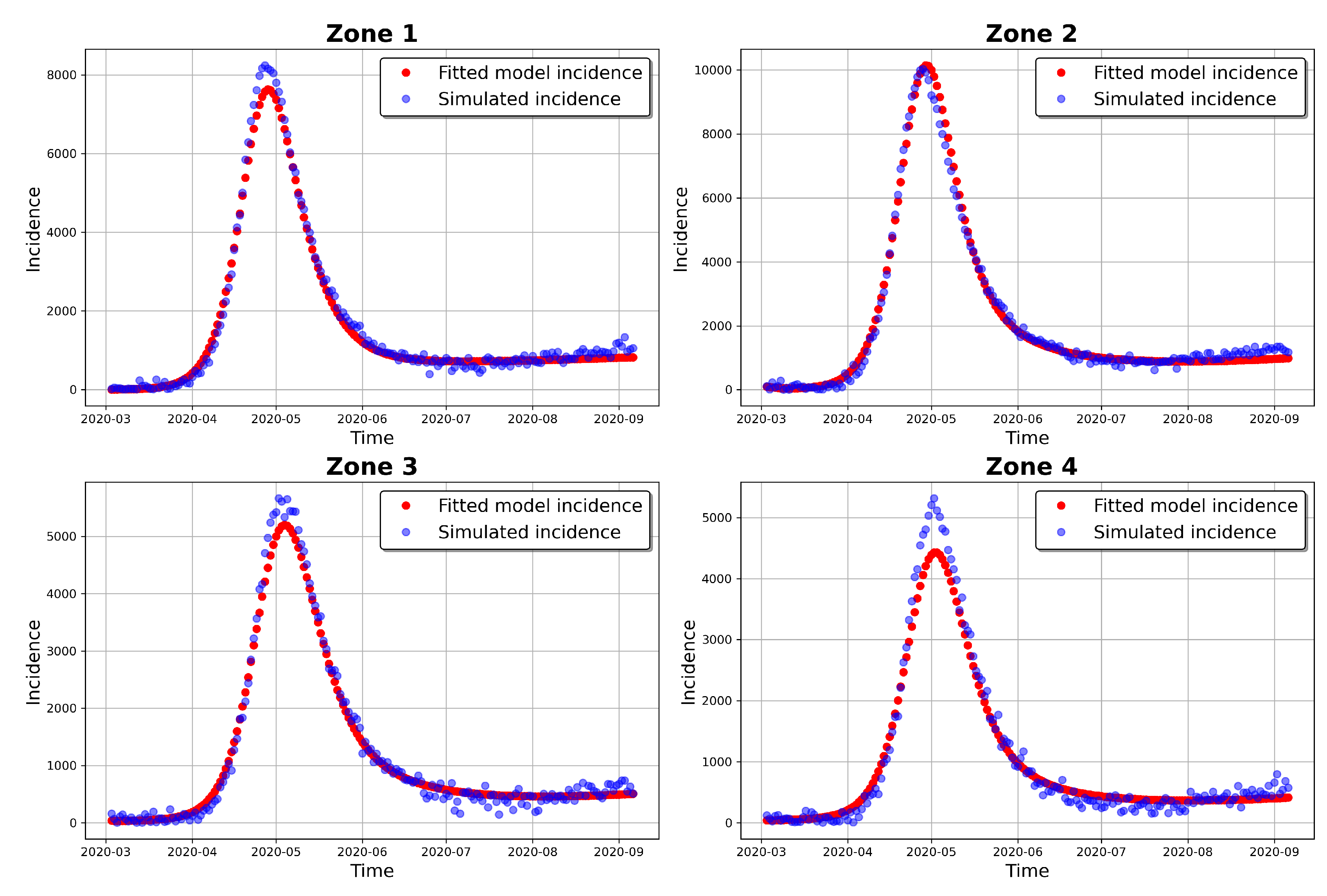

The incidences output from the epidemic model (

1) are very sensitive and exhibits a lot of uncertainty to slight changes, especially of the contact, incubation and recovery parameters. As a consequence, it was challenging to provide a wide range of values as support of the posterior distribution in Stan and t-walk. We addressed this challenge by beginning with the deterministic inversion of the epidemic model using GA, as is discussed in the previous section. The output of this inversion are given in

Table 5. Consequently, we use the point parameter estimates obtained from the GA as the initial sampling points for t-walk and Stan. Moreover, as there is no literature for the parametric spaces of the incubation and prevalence states initial conditions, we delimit their support in the posterior distribution in the neighbourhood of their point parameter estimates obtained from the GA.

After performing the prior predictive checks, using the t-walk package [

133], we obtain posterior samples for each of the 24 parameters (

13). MCMC methods, from its definition, produces samples that can have high correlation, harboring some level of redundant information. One way of measuring the level of information redundancy in the posterior sample, is by using the effective sample size (ESS). Theoretically, ESS is the sample size we would obtain if we independently sampled the posterior distribution. The ESS and the proportion of ESS (pESS) of the simulated samples are given in the last two columns of

Table A1. Going by how low (high) the values of ESS (pESS) are, we can tell that the simulated chains are highly correlated and thus, this MCMC method requires very high number of iterations. In other words, to obtain samples with insignificant auto correlations can require thinning at large lags, which can remarkably reduces the chains sizes. To obtain chains with reasonable sample sizes for analysis, after running this MCMC method for 1,000,000 iterations, we discarded 360,000 burnin samples and thinned the chains at lag 20.

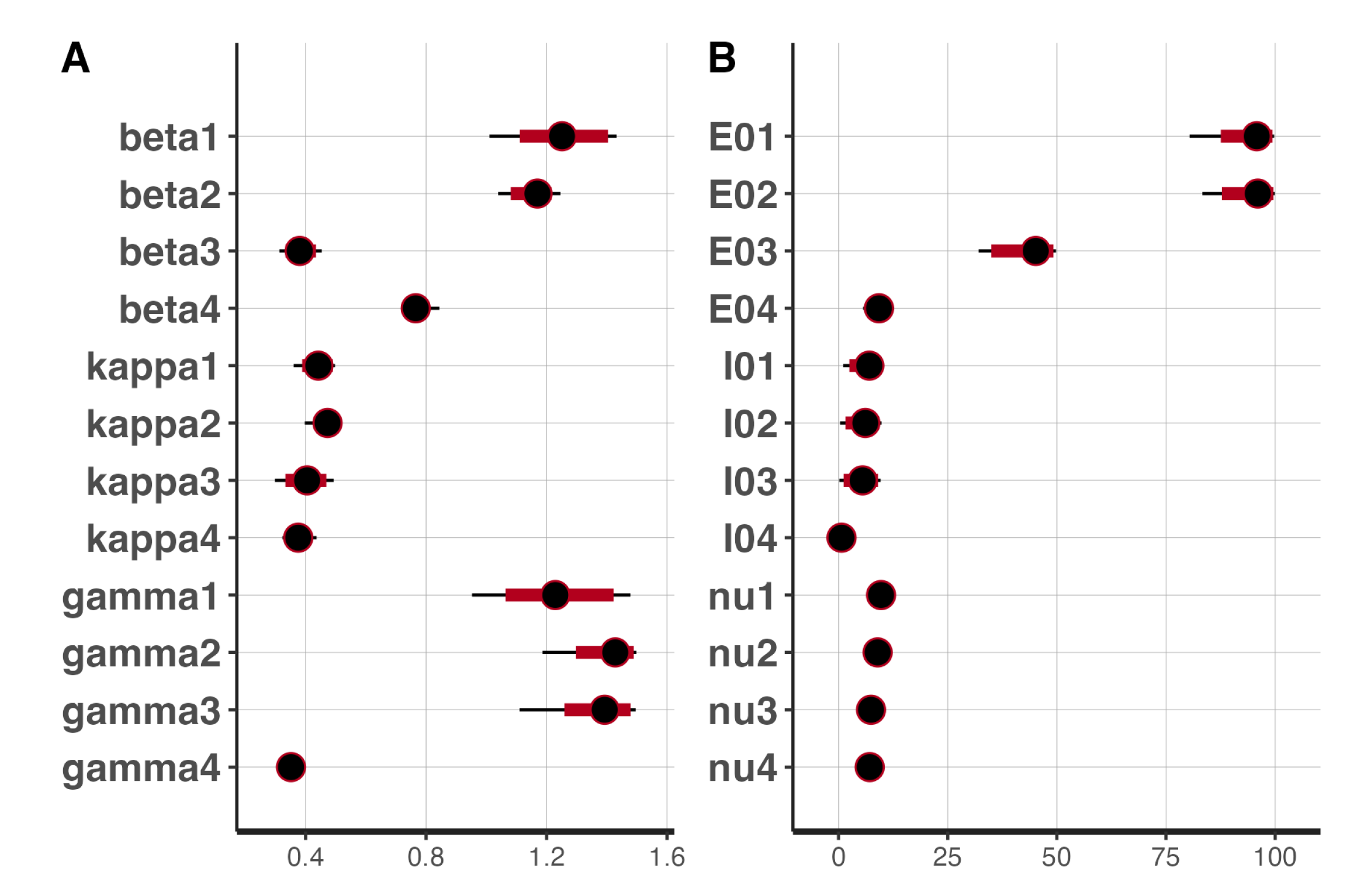

The summary statistics of the generated samples are given in

Table A1 (in the Appendix). As can be observed, the presented summary statistics are; the mean, variance, 95% credible interval (CI), median, ESS and pESS. From this table, we can conclude that in general, all the samples exhibited low variability and that their means are close to the estimates obtained from the GA in the previous section. Further, we can conclude that the means (and medians) are all within the 95% CI. The former and the latter observations can be confirmed from

Figure 9, which shows the 95% CI of the samples, the mean and the estimates from the GA. Based on the scales of the values in the intervals, we can conclude that the credible intervals (CIs) are generally short, an indication of good estimates.

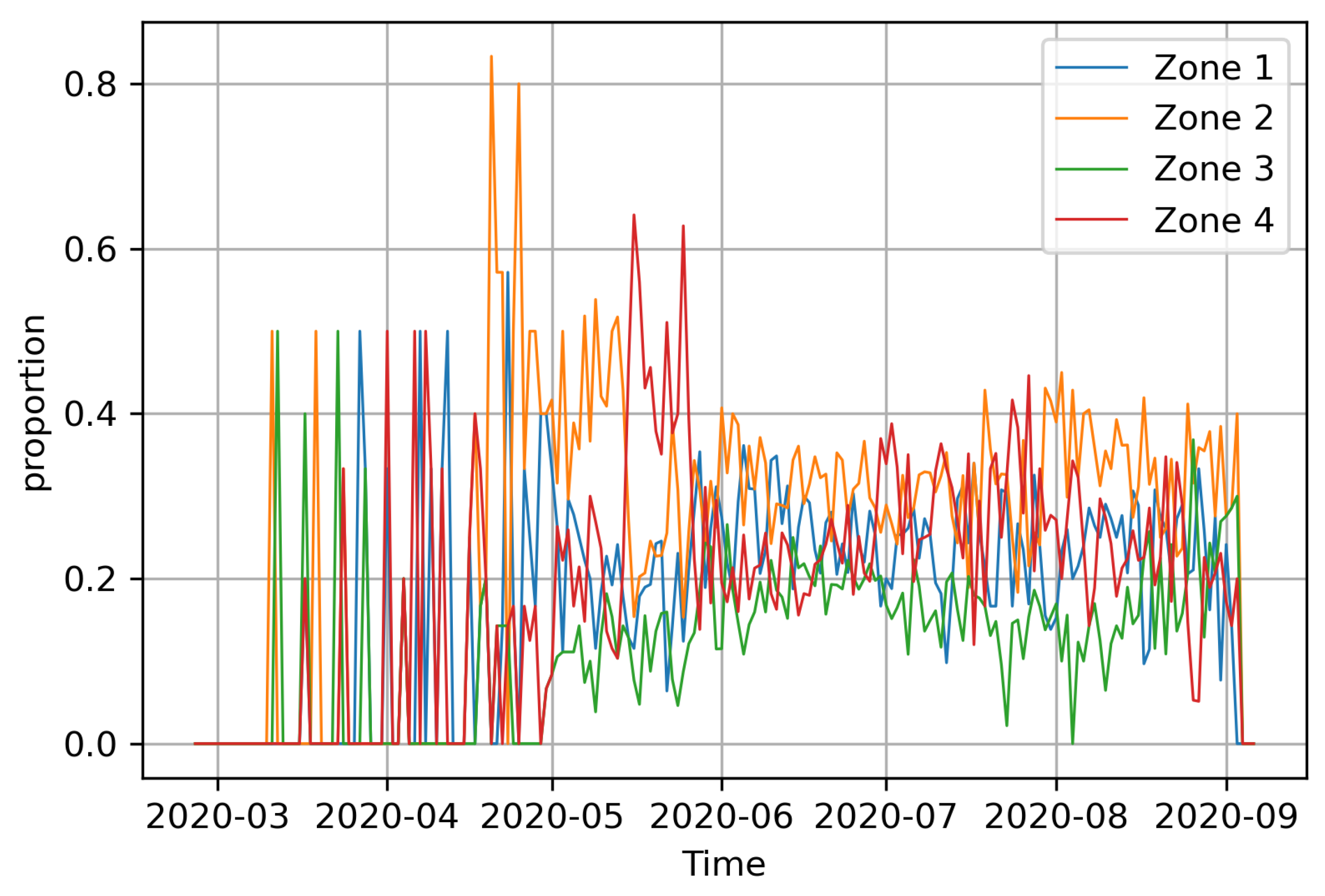

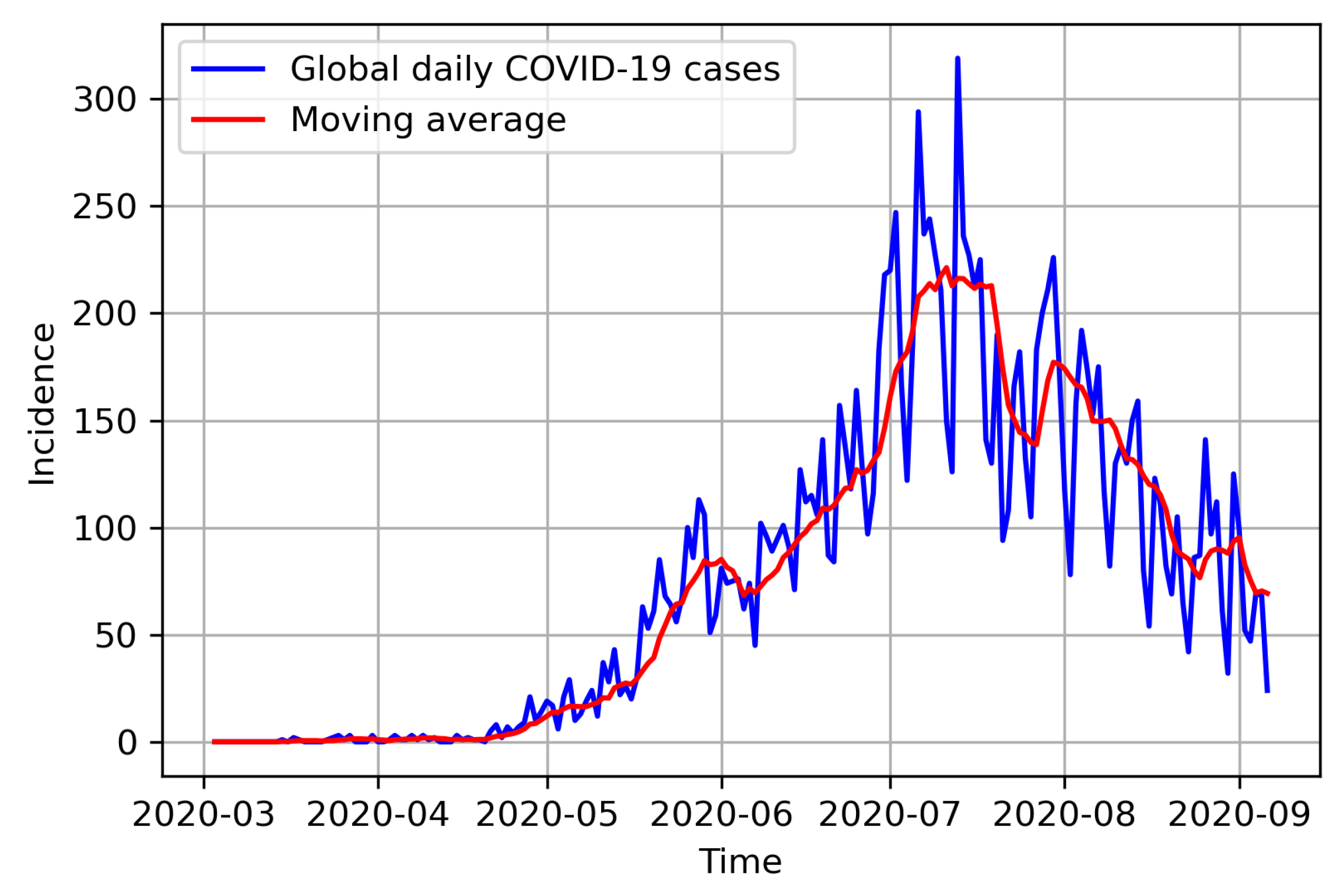

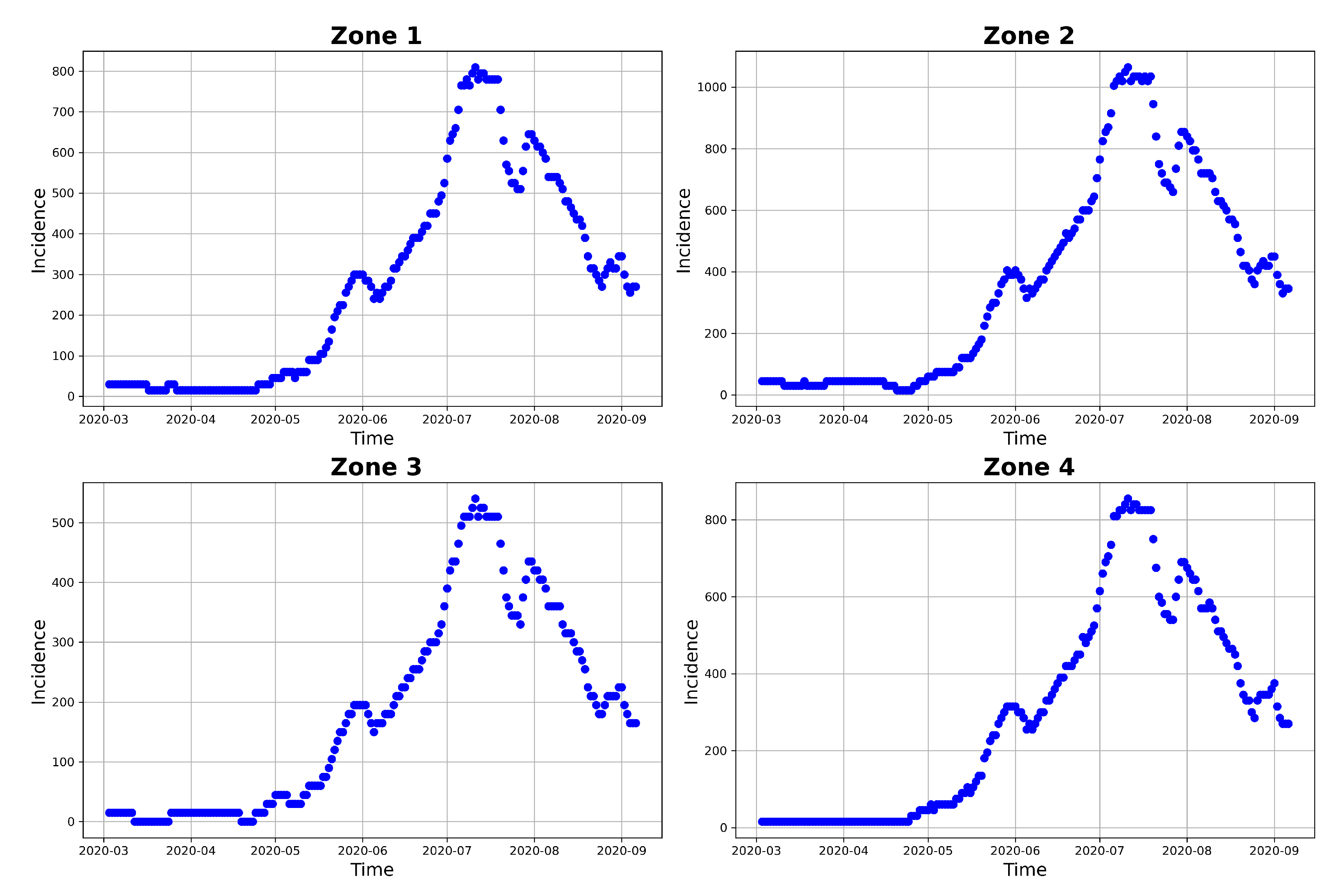

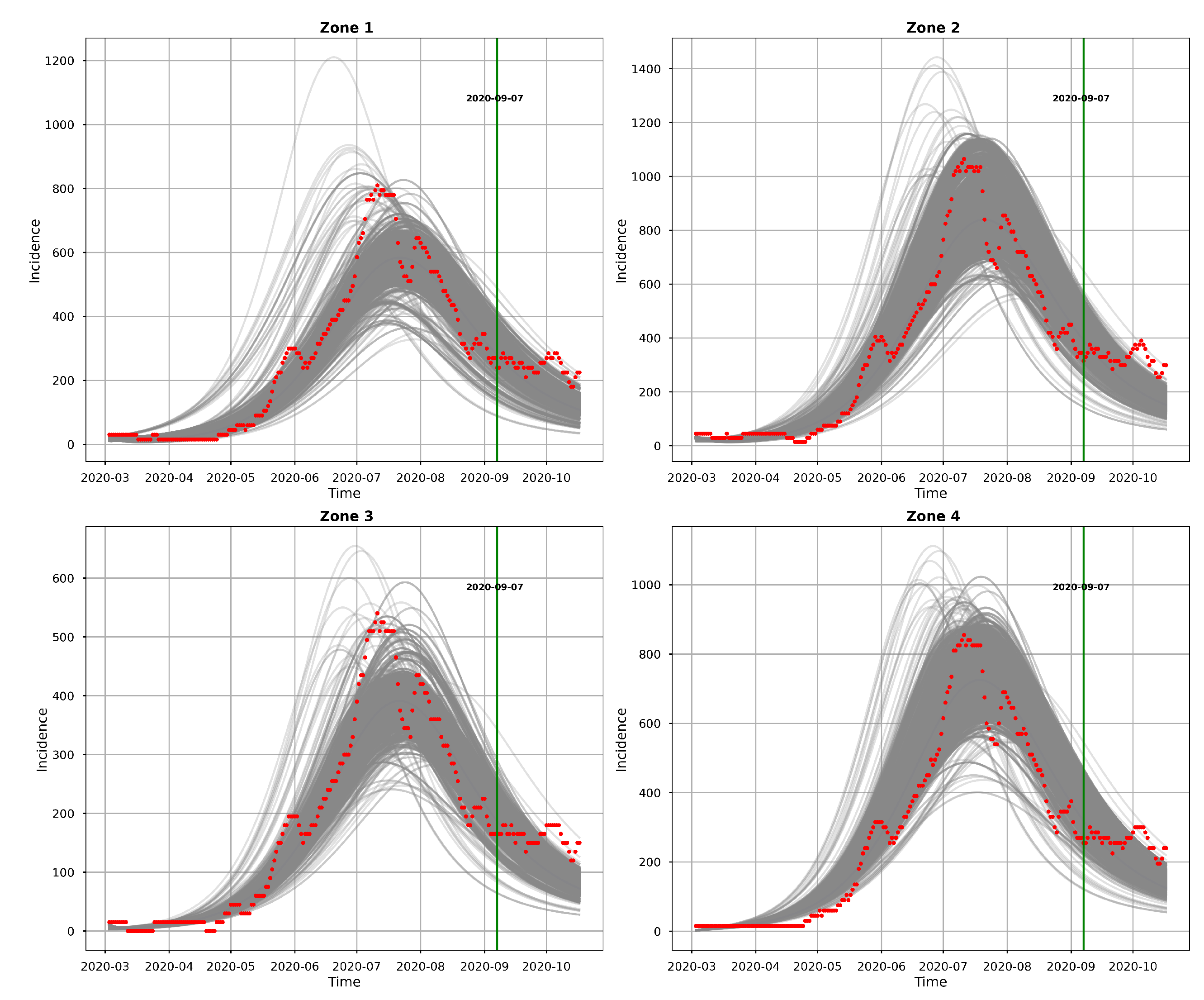

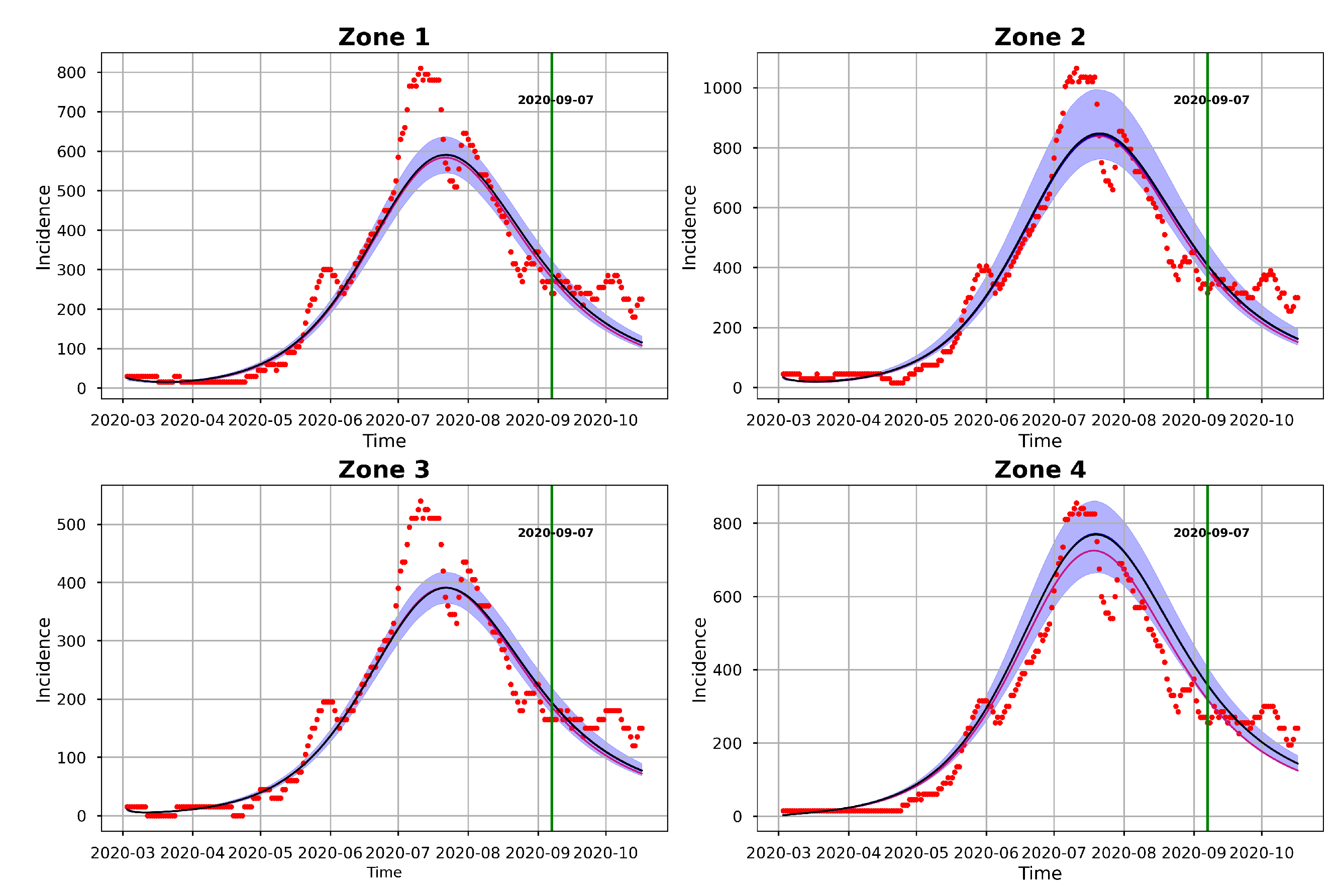

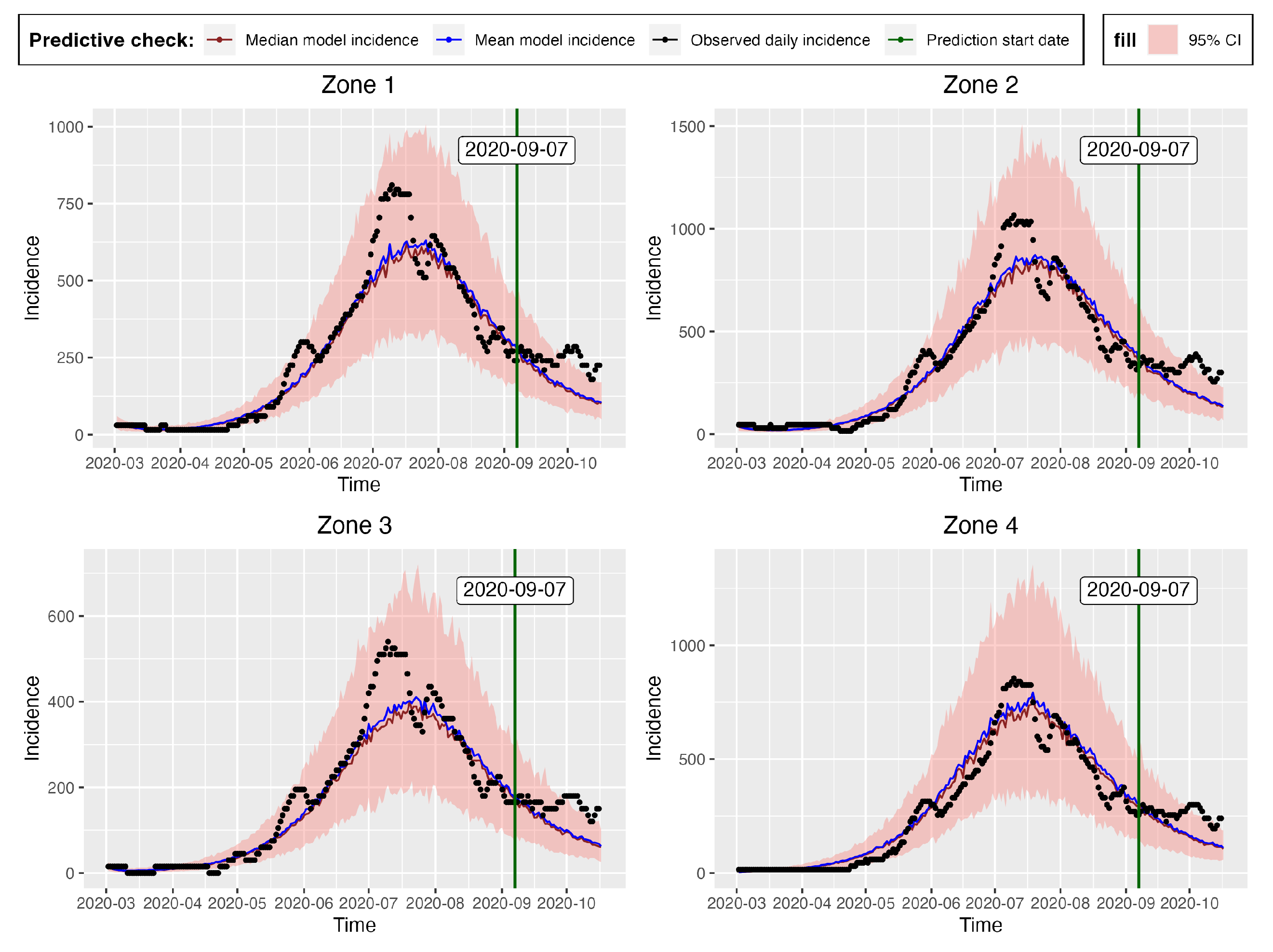

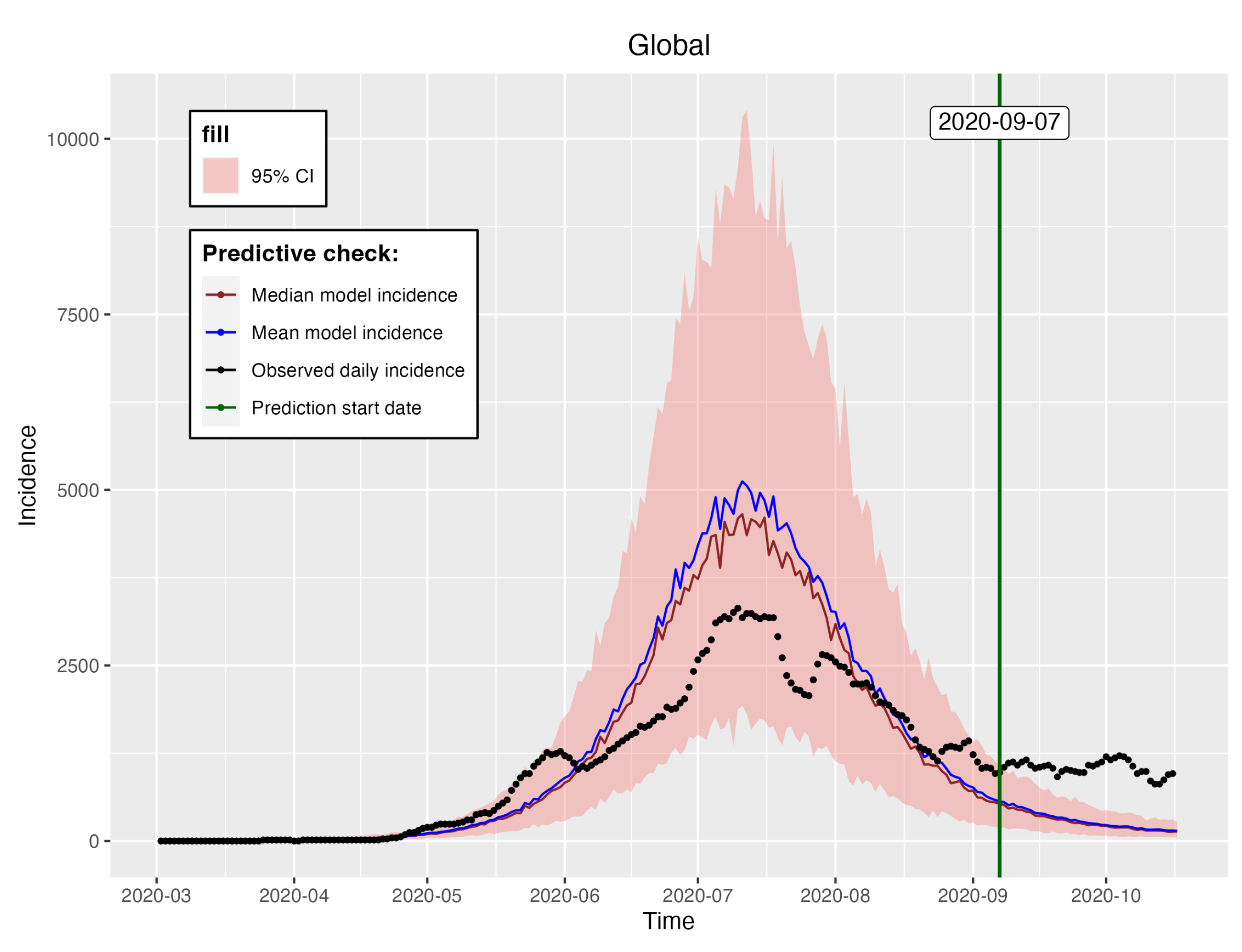

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 represents the posterior predictive checks. The figures graph the incidence simulations of model (

1) from 2020-02-26 to 2020-10-17. This period includes the dates within which the incidence data was observed (2020-02-26 to 2020-09-06) and 41 days prediction dates (2020-09-07 to 2020-10-17).

Figure 10 shows 30,000 model incidences (grey curves), from the first 30,000 MCMC iterations, the observed incidence and the

maximum a posteriori (MAP) model incidence. Here, the MAP model incidence, which is apparently covered by the grey curves, is the model incidence output obtained from the parameter values that maximizes the posterior distribution. We can observe from this figure, that 1) our fitted model produces simulations that are consistent with the observed incidence data and 2) the simulated trajectories do not portray diverse or variable changes. Indeed, the latter observation is consistent with our previous observation that there is low variability in the simulated samples.

Figure 11 shows the 95% posterior confidence intervals (CIs), the mean, median and the MAP of the simulated model incidences. From this figure we observe that most of the observed training incidences for the four zones, fall outside the 95% CI of the simulated model incidence with zone 1 and zone 3 simulated model incidences providing the narrowest 95% CI. In contrast, zones 2 and 4 have larger 95% prediction CI, and they cover more of the observed incidence. Zone 1 model prediction interval provides the worst coverage of the observed prediction incidences in this zone. The proportions of the observed prediction incidence covered by the 95% CI of simulated model incidence from t-walk are presented in

Table 8. As the CIs for the four zones are generally not too wide and covers a small proportion of the training observed incidence, and the prediction observed incidences for zones 3 and 4, we can conclude that the point estimates from t-walk seems adequate, but we tend to underestimate the uncertainty associated with the estimated parameters.

We can observe from both

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 that the model predicts that there will still be some infection levels beyond 2020-09-06, the date when we observed the last incidence. In fact, the figures reveal that in the four zones, some individuals will still be infected up until 2020-10-17, with the median and map incidences being within the 95% CI.

After checking the adequacy of the prior distributions with respect to the posterior distribution and sampling, using the t-walk package, we also performed sampling of the posterior distribution using the Stan package. Stan is a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) based package designed for Bayesian statistical analysis. We refer the reader to [

134] for more details about the software and [

132,

135] for an insight on how the package can be used to perform inference and uncertainty quantification of compartmental epidemic models.

For Stan, we used the same support for the prior distribution as used in t-walk, except for the incubation initial conditions. Using the same support for the incubation initial conditions in t-walk led to very low overall proposal acceptance rate. As such, we had to use a different and shorter support range for all the incubation initial conditions prior distributions in t-walk in order to have reasonable proposals acceptance rate for the algorithm. However, in Stan, the support range for the same parameters were larger as Stan is more robust. For the over-dispersion parameters, we used the transformed versions and sampled their inverses in Stan.

For the model at hand, we ran one chain with 1,000 iterations for each of the 24 parameters and took the first 300 iterations as burn-in samples. The number of iterations is not the same as those obtained from t-walk as Stan requires longer periods of time, than t-walk, to complete each iteration. However, from the analysis, we observe that the chains are importantly less correlated, and we can obtain bigger effective sample sizes.

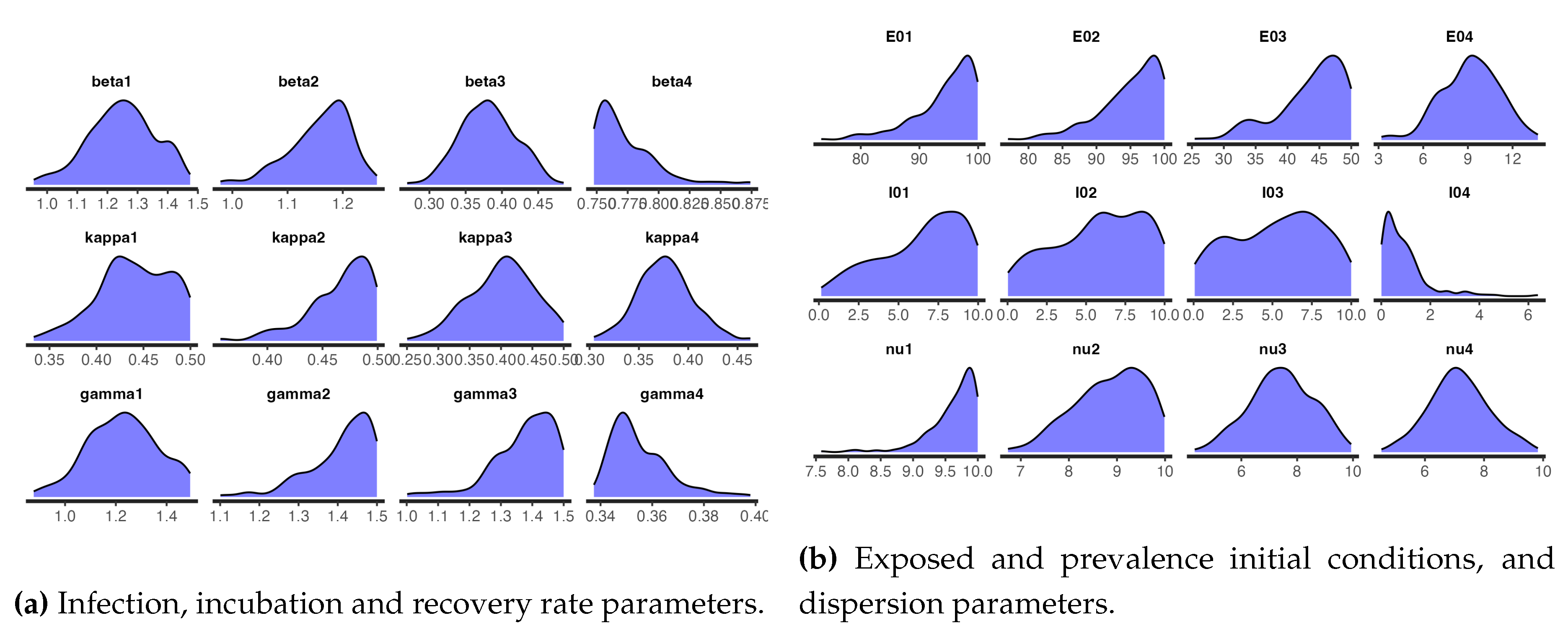

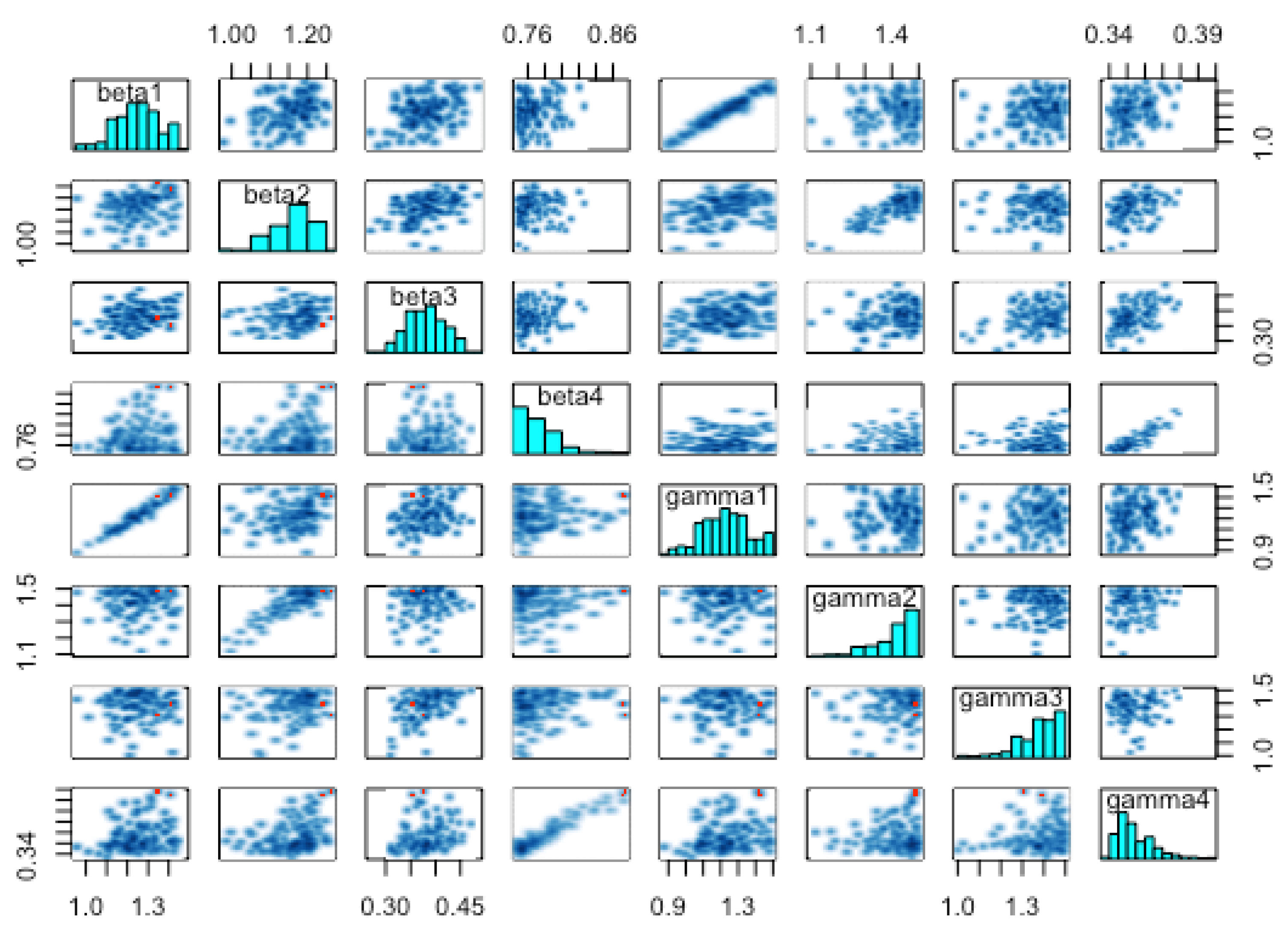

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 respectively shows the trace plots and the posterior densities of the samples of the estimated parameters. We obtained unit Rhat values from the Stan summary statistics output, an indication that all, except two, of the transitions converged. Additional Stan statistics, particularly, the diagnosis of the pairs plot of a subset of the estimated parameters, (

Figure 14), confirms convergence of all, except two of the transitions of the chain during sampling.

Figure 15 shows the 95% CIs of the posterior distributions obtained from Stan. All the parameters, except

,

,

, and

, had short CIs. It is noteworthy that just as in t-walk, the samples of the inverse of the over-dispersion parameters,

from Stan had very narrow intervals.

The pairs plot in

Figure 14 shows the posterior distributions of the infection and recovery parameters (diagonal figures) and scatter plots (off-diagonal figures) showing the relationship between each of the samples. Since there were many (24) parameters to estimate, it was not appealing to have a joint pairs plot for all of them. In as much as this is the ideal procedure, doing this would lead to a figure with very tiny non-visualizable figure entries. We thus chose to pair the infection and recover rates (see

Figure 14), as the scatter plots of these parameters exhibited interesting relationships. For instance, we observe from this figure, that there was a strong linear positive posterior correlation between

and

,

and

and

and

. In contrast, the infection parameters for the four zones did not exhibit any important relationship among themselves. This was also the case with the recovery parameters.

The summary statistics of the samples as obtained from Stan are shown in

Table A2. These statistics are slightly different from the summary statistics from t-walk as displayed in

Table A1. The differences in the statistics of the prevalence initial conditions and the over-dispersion parameters are obvious, as we have already mentioned that besides using different support ranges for thesethe distributions of prevalence initial conditions, we transformed and sampled the inverses of the over-dispersion parameters

,

. Otherwise, the slight differences in the statistics of the other parameters could have been occasioned by the difference in how the t-walk and Stan packages performs sampling. Notably, these differences would not lead to a different conclusion regarding the potency of COVID-19 infections in Hermosillo in 2020. The statistics in

Table A2 reveals that the point estimates of the parameters are within the 95% CIs as is the case with the estimated parameters from t-walk, as can be seen in

Table A1.

The differences in the summary statistics of the samples obtained from both packages is further reflected in

Figure 11 and

Figure 16, which are the posterior predictive check figures from t-walk and Stan respectively. We can observe that the mean, median and the observed incidences for each zone are all covered by the respective 95% CIs. In comparison, we observe from the t-walk output in

Figure 11, that whereas the 95% CI of the epidemic model incidences did not cover some observed daily incidences, the same interval from Stan covered all the training observed zonal incidences. We thus conclude that the estimated parameters from Stan can capture a more realistic uncertainty level, compared to those estimated by t-walk. Both

Figure 11 and

Figure 16 reveals that COVID-19 infections in the four zones, and consequently, the whole of Hermosillo, was at its peak in mid-July 2020, with a prediction of continued infections beyond 2020-09-06, which was the last date of observed training daily incidences.

Table 2 shows the ranges of the parameters of the model as obtained from various COVID-19 literature. Our results, both from the GA, t-walk and Stan packages (see

Table 5,

Table A1 and

Table A2), indicate that the point estimates of the infection and incubation parameters;

and

,

, that best fit the incidences for the four zones, were within the ranges from literature. This is however not the case for the recovery parameters,

, whose estimates were obtained as generally averaging close to one day recovery period for the four zones. This result is not surprising, as our incidence data for the four zones were inflated by a large under-reporting factor. This inflation, besides accounting for a possible lack of systematic testing of COVID-19 in Hermosillo, also accounted for the existence of subclinical and asymptomatic COVID-19 patients in the four zones under study. Going by how well the model fits the data, (see

Figure 7,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 16), we believe that accounting for incidence under-reporting by a factor of 15, as reported by [

86] is realistic.

We further evaluate the prediction capability of the multi-patch model by checking the proportion of the observed zonal prediction incidences that are within the 95% CIs of the zone model incidences.

Table 8 shows these proportions obtained from Stan (see

Figure 16) and t-walk (see

Figure 11). From this table, we can see that Stan produces 95% prediction bands that cover more than 50% of the observed prediction incidences for all the zones. On the other hand, t-walk provides 95% CIs large enough to cover less than 50% of observed prediction incidences for all the four zones, with zone 1 providing the narrowest simulated model incidence CIs that covers only 22.22% of the observed prediction incidence. In effect, we conclude that Stan outperforms t-walk as regards to the percentages of covered observed daily prediction incidence for all the zones.