1. Unused publicly owned buildings and civic actors: a fertile combination for social innovation?

The economic crisis has exacerbated the phenomenon of unused and abandoned buildings both private and public, and it has revealed how traditional planning policies are no longer adequate. Also, urban resilience and adaptive re-use are quite debated topics in the contemporary literature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This is a situation shared across Europe, but specifically, the issue of disused publicly owned buildings is urgent in the Italian context. Unused public properties, either because of inefficiency [

6,

7,

8,

9] or for speculative reasons [

10], are a problem in themselves. The ethical issues are not the same as those for private buildings [

11,

12,

13] precisely because the property is ‘public’. According to the general definition of the public sector’s obligations and duties, the Italian contemporary situation presents some deficiencies in desired outcome. Also, the economic downturn shows how financial shortage influences (i) private interventions [

14,

15,

16], speculative and strategic intentions, (ii) government policies. On this line, new ways to consider public portfolios (and buildings in particular) have been emerging. In particular, the contemporary Italian context is facing a shift towards new economic, financial and social conditions [

11,

17]. These kinds of ‘experimentations’ might be considered as new and different way to address social, economic and environmental changes [

18,

19].

From this perspective, the idea to consider a new trend of experiences, launched by the so-called ‘civic actors’, for renovating and revitalising unused public buildings is twofold. On the one hand, there is a general acknowledgement that some policies and regulations on the management of public buildings must be rethought. This phenomenon is also important in considering the Italian context since the after-crisis situation has highlighted how traditional planning models are no longer effective for renovating and regenerating buildings [

16]. Also, considering these practices as an emerging phenomenon, it is important to understand their role: either to reinforce a status or to generate new opportunities for thinking anew regulatory and physical contexts [

18].

On the other, there is a progressive awareness that public spaces (in this case, public buildings) might be considered relevant places, as they are the expression of people’s claim, freedom and rights see also [

20]. What emerges is a variety of bottom-up and top-down activities that combine social needs with governmental purposes [

21,

22]. This field is where civic actors have a strong pull. That phenomenon has taken place since the middle 2010 in Italy with different attempts to define and promote

temporary uses , for the Italian case, see [

4,

23] through many public policies (at both the regional and local levels) [

4,

24,

25,

26], and new regulations (see

Regolamento dei beni comuni and

Patti di Collaborazione, promoted by Labsus) [

27,

28]. This new tendency considers bottom-up experiences and temporary uses as a trigger for revitalisation [

29,

30]. Moreover, increasing discussion and debate have focused on communities and their potential to self-govern creative practices and self-provide services, facilities, and local welfare [

31,

32,

33,

34].

The paper is an extract of a broader research, and it will discuss briefly some of the key elements that contribute to enhancing the current debate on these initiatives. On the one hand, the overproduction of laws and regulations hardly influence and limit this phenomenon; on the other hand, these emergencies and urban experiments are highly and inherently political [

18], which means that their role is directly connected – or not – to more systematic and structural changes.

The paper illustrates the Italian context, particularly providing a sample of cases to discuss these new ‘civic’ experiences to promote the revitalisation of unused buildings. The aim of the paper is to critically discuss similarities and dissimilarities of the cases, with specific attention to the background conditions fostering these practices. Also, the paper suggests policy guidelines, conditions, and limits for these experiences to occur.

2. Institutional performance and methodology

The approach used in this paper is the Ostrom’s framework towards institutionalism and the case studies analysis [

35,

36]. In brief, in Italy, this phenomenon of civic actors and their role in revitalisation processes is still under investigation, and it has to be disentangled and organised. The risk is to over-regulate those experiences without any specific directions, within a regulative framework. This attitude has been reiterated by public governments, introducing different tools almost annually to solving public buildings disuse.

The kind of self-organisation civic actors have, might be analysed from the point of view of the institutional performances, and incentives Ostrom derived [

35]. Moreover, these practices are likely recurring, and institutions are used and crafted by individuals “to organise all forms of repetitive and structured interaction” [

36](p.3).

Although it is not so well spread in urban planning concerns [

37,

38], the importance of having a new institutional approach is based on three elements. First of all, the analysis of institutions provides a different way to consider and analyse complex systems, such as cities or governance processes [

35,

39,

40]. Second, it explores contexts and activities that might be embedded into practices, that are difficult to be acquired from a rough generalisation [

37,

41,

42]. Third, this framework might reveal how institutions have contributed to creating and recreating a robust setting for successful cases [

18,

43]. In general, this approach underscores that “the application of empirical studies to the policy world leads one to stress the importance of fitting institutional rules to a specific social-ecological setting” [

44](p.642). This is made because ‘one fits all’ policies are not effective if the discussion is focused on institutions, incentives and patterns of enforcement.

This approach is combined with a case-based method of investigation. The paper will discuss what emerges according to the analysis of a sample of different Italian experiences about revitalisation processes by civic actors. The use of a

sample to present the phenomenon might be helpful because it (i) provides a certain degree of generalisation and representativeness for the phenomenon, and it (ii) allows separation between theory and testing [

45](p. 125). The

sample includes 45 cases. In particular, the research is grounded on the QCA methodology [

46,

47]. This method contributes to better understand the complexity of each case, introduces comparable basic categories for generalisation, and it helps in deriving conditions and incentives, that might help in encouraging and guide these kinds of practices.

3. Civic actors and revitalisation processes: the result of an Italian investigation

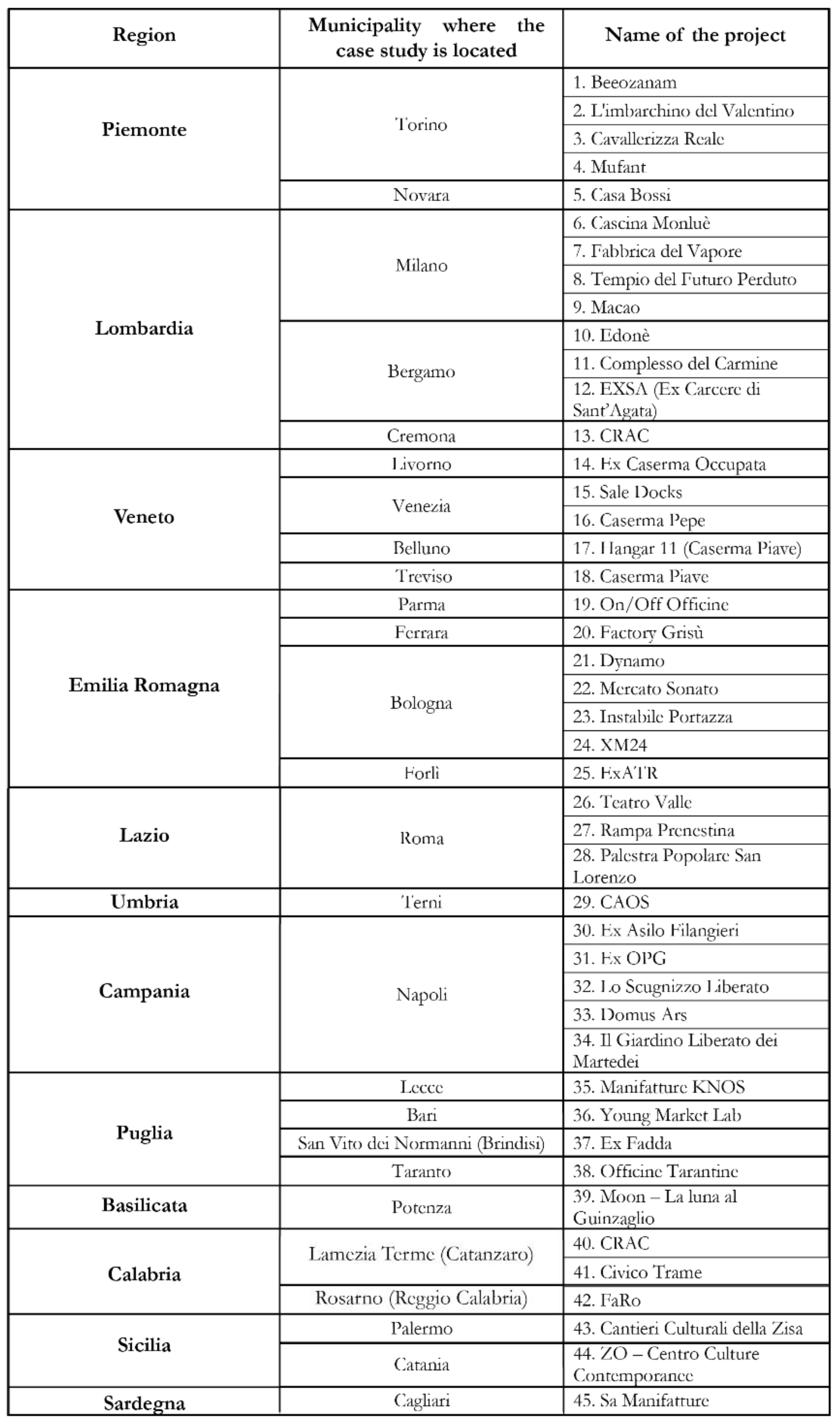

As already mentioned, the case studies have been extensively discussed in the broader research (They are extensively analysed in the PhD thesis, discussed in July 2021.). Here, there will be just a glimpse to better understand the Italian contemporary city. The cases are organised in a

sample of 45 Italian heterogeneous revitalisation experiences made up by civic actors (

Figure 1).

Some of the cases are still ongoing (64%), some others are pending (13%), and another portion is concluded (23%) (Last update February 2023. The first research was made within 2019-2020, and the average was a bit different, with 64% of cases ongoing, 18% of cases ‘pending’, and the 18% of concluded). This kind of categorisation is important to understand the different dynamics and to acknowledge the fact that there might be issues limiting or hindering the processes. The first impression, based on the sample, is that more than one-third of these experiences have encountered complications. This is the reason why this analysis is based on empirical evidence. They have been investigated through the QCA analysis, with the introduction of comparable basic categories that might help in generalising some of the features.

These studies are made to better understand the different typology of cases of revitalisation processes and, on the other hand, it helps in thinking about these practices with a more critical and systematic approach. Moreover, the need to structure these experiences through regulations and norms might lead to entirely unexpected outcomes [

48].

This section aims to discuss the findings that have come to light by analysing the sample.

The findings have been subdivided based on some key elements, such as (i) the location of the unused (and then renovated) building, (ii) the patterns of behaviour, civic actors’ institutions and public sphere’s attitudes, and (iii) the uncertainty. All these elements help in deriving the essential background conditions that will be necessary for investigating the institutional performances civic actors have in revitalising unused buildings.

3.1. Location of the building

The sample underscores that a large part of the experiences is located in the central or semi-central area of the cities (64%); the other portion is located in suburban or peripheral areas, despite the size of the cities. The kinds of activities are similar, but the services provided in the latter locations concern social services and answer more local needs (e.g. FaRo in Rosarno, Palestra Popolare di San Lorenzo in Roma). In general, the buildings in city centres are more likely to be ‘cultural hubs’ (e.g. Fabbrica del Vapore in Milano; Manifatture KNOS in Lecce [

49,

50] ). Public buildings that function this way are large and flexible enough to enable civic actors’ experiences inside. What emerges is that larger cities are more likely to be more dynamic. That is directly related to the idea of creative industries and social capital [

16,

51].

In most cases, the former condition of the public buildings was either abandoned, or ‘dismissed’ – but not abandoned – which means that the building is no more performative for specific functions. There are a few examples in which the public building (or the space in question) might be considered ‘empty’. However, the restoration of public buildings does not have a direct connection with full use, in fact, some of them were still partially unused.

The reasons are two: (i) civic actors are non-profit so they do not have enough money to revitalise and restore big buildings, but only part of them; (ii) rationalisation made from public administrations for different reasons, such as speculative ones.

3.2. Patterns of behaviour, civic actors’ institutions and public sphere’s attitudes

Analysing civic actors based on their three main features (nature of the group, nature of the action, and nature of the trigger; [

11] )a set of different patterns of interface emerges. In general, for what concerns the nature of the group, the distinction is quite standardised (either formal or informal); but when introducing the analysis of their action (bottom-up or top-down) and the trigger (licit or illicit), it is important to clarify the processes. Here, the boundaries are more nuanced and equivocal, since these aspects are referring to the specific dynamics happening case-to-case. As the role of civic actors in revitalisation processes might be very complex and difficult to manage, this analysis leads to the investigation and the study of the patterns of behaviour and the construction of robust – or fragile – institutions. On this concern, civic actors’ and the processes they pursue have been divided into three clusters of interface. The clusters are intended to present different combinations of ‘actions-trigger’ that might describe what nowadays happen when revitalisation processes take place in unused public buildings. The interface clusters are divided into three main categories: (i) traditional, (ii) cooperative, and (iii) non-traditional. This distinction is important because each case is unique and, although similar patterns of behaviour or context, the outcome might be unexpected.

This aspect is related to the concept of uncertainty, which is quite spread in those processes. Using the clusters of interface and understanding the kind of dynamics, might help in lowering the degree of uncertainty, activating other forms of interactions and other patterns of behaviour and, at the same time, make the institutions evolve.

The first cluster relates to traditional patterns of behaviour. This category includes ordinary and streamlined processes of revitalisation (it is around the half of the experiences in analysis). It involves cases where the public administration decides to entrust public buildings to civic actors for social and cultural purposes. Frequently these are related to the formal organisation of civic actors. According to the different dynamics, the traditional cluster highlights that the intervention on unused buildings is frequently made from the public sector and, civic actors only settle inside it, after a public call. In general, the traditional cluster is the one where civic actors are formal, act in a top-down manner and have a licit trigger (e.g. CAOS in Terni; Fabbrica Grisù in Ferrara; Mercato Sonato in Bologna).

The second cluster is called

cooperative. It consists of cases where cooperation and ‘coproduction’ [

52] are the key elements of the revitalisation processes (around one third of the whole cases). The label “cooperative” is, in fact, because civic actors and public administrations are crafting together patterns of interaction able to convey a common idea of revitalisation [

42]. In this case, civic actors might also present their revitalisation project in the first place. This means that the process might be from the bottom up. In general terms, the

cooperative cluster is modelling the bottom-up experiences that have been emerging spontaneously and without any public advice. Once civic actors start the process, they might (but not always) encounter public interests; it means that the conditions and the arrangements could be

tailored specifically for

that case. The mutual arrangements and pattern of behaviour in this cluster is very important and might lead to interesting outcome. In this cluster, the trigger might be both

licit or

illicit, but the outcome is a tailored agreement (e.g. Asilo Filangieri in Napoli; Edonè in Bergamo).

The third cluster is called

non traditional, in opposition with the

traditional one. In general, it has a bottom-up approach to actions, but the nature of the trigger starts as

illicit (outside the legal domain; they are less than 20% of the sample). In this case, civic actors do not follow any legal framework, either because that experience is not taken into consideration by public administrations or because civic actors are in conflict with them. There are two different directions that non-traditional experiences might have: (i) convey into more

cooperative clusters (e.g. Sale Docks in Venezia), (ii) remaining in a conflictual situation (XM 24 in Bologna). This is also related to civic actors’ attitudes: (i)

moderate and (ii)

extreme. The main difference is how they express themselves and their beliefs.

Moderate civic actors are willing to cooperate for the collective interest;

extreme civic actors possess a strong tendency towards an unconventional, politically oriented approach [

53].

These clusters of interfaces have to be considered as ‘fluid’ categories as the patterns of dynamics are very heterogeneous, but they highlight two elements, in relation to ‘the perfect- timing’. First, the civic actors’ settlement in the building, second their temporary (or more stable) presence in there. Combining together these elements, taking into account the time-related steps, this distinction among the clusters might be helpful in understanding the complexity of the cases in the first place, and allows for further investigations. In general, the sample helps in having an important outlook in relation to revitalisation processes.

These clusters of interface have to be considered as a categorisation of a variety of different dynamics, that share two common elements: (i) civic actors’ behaviour and its consequences, and (ii) the public administrations’ attitude. In general, public administrations’ attitude is very important into revitalisation processes, and its bias might be risky, and leading to uncertainty.

There are three different attitudes identified: (i) promoter but neutral, which means the public sector initiate the process but then do not interfere in any ways with civic actors activities (this is the case in traditional cluster); (ii) promoter and collaborator, that is the tendency of the public sector to cooperate with civic actors either for reaching an agreement or for enriching and strengthening the process (this is the typical case of the cooperative clusters); (iii) conflicting, which means that civic actors and public administrations do not agree on specific aspects of revitalisation processes (this is potentially happening in non-traditional clusters, but also in the preliminary stages of the cooperative clusters). These elements and the analysis of the clusters is particularly important to understand the complexity of the case in the first place. Also, these ambiguities and the need of a first categorisation are related to the lack of a general understanding of these practices from governments and the continuous copy-paste regulations that do not allow for flexibility and ad hoc situations. The clusters of interface and the public administrations’ attitudes have highlighted how civic actors’ activities might be reliant on external situations, not totally dependent on them. In general, the kind of temporariness they might have (it might be years, but also months), influences how they pursue and perform revitalisation processes. These elements contribute to creating uncertainty.

3.3. Uncertainty

Ostrom [

35] discussed this situation of uncertainty as an element that institutions have to challenge to evolve and strengthen themselves. She underscores the importance of having a problem-solving attitude, which contributes to cases’ success [

35,

54]. Here, two different levels of uncertainty might come to light. On the one hand, the building that they are managing is publicly owned (public reliance); on the other, the process might eventually take unpredictable directions.

To lower the level of uncertainty, it is possible to work in advance on civic actors’ reliance on public administrations. Their dependency is influenced by the nature of the cluster, as well as the public attitude. The more the clusters of interface are conflictual, the more civic actors aim for a change in the political public administration government. In those cases, the level of uncertainty is already high, so they are more prone to face changes, and to interact with different public organisations. The less conflictual situations, instead, might have a higher level of uncertainty, as a change in political government might either enhance to process or worsen it. Knowing in advance what are the costs and benefits of any situation, might help in organising the revitalisation processes more deliberately. This analysis is important as it highlights how revitalisation processes are continuously evolving and unpredictable [

41,

55].

In general, the sample of revitalisation processes has highlighted three important elements that these experiences share.

The idea to categorise the patterns of behaviour and the kind of possible alternatives might be useful to understand the kind of interventions policy-makers, civic actors or public administrations might adopt (the co-creative planning, von Schönfeld et al., 2019). Likewise, the analysis of the experiences has highlighted similarities in the organisations and practices that might happen in very different contexts, each of them affected by very diverse local conditions [

56]. This depends on the specific attitude of each of the stakeholders, as they craft rules that might affect one situation or another. Nevertheless, acknowledging those experiences as complex might help in coping with uncertainty [

57]. As revitalisation processes are very diverse and they respond to very specific institutions and contexts [

58], it is crucial to underscore the importance of the uniqueness of the processes, and it highlights how diversity and complexity are clear conditions in contemporary urban contexts [

36].

4. The role of background conditions in revitalisation processes

The Ostrom’ framework and approach are crucial in this phase. It is important to highlight that, although some similarities, each case is different from the other, and that the traditional way of planning seems to be inconsistent with those practices. Moreover, the sample presents that there is another distinction among the experiences: as Ostrom, the processes are considered successful or not successful. To consider a process as a successful or not successful, the distinction is based on the outcome of the revitalisation processes. This is connected with: (i) the structural improvement of the building in question (functional aspects), (ii) the innovative, social-friendly and culturally-driven activities in the building (the meaning of the building), (iii) the community participation, and (iv) the continuity of the process throughout the time. That is important as ‘revitalisation’ relies both on physical aspects, and on social and participatory practices.

The paper refers to Ostrom’s principles [

35], redefining them as ‘background conditions’ since they are related to the contextual and institutional domain. In general, the background conditions might be distinguished between

case-based conditions (internal to the process and the stakeholders) and

framework conditions (derived from the environment).

These elements interact in complex ways that influence the dynamics and the potential ‘trajectories of transformation’ of governance, which are highly diverse and contingent. Moreover, the different

case-based and

framework conditions are not separated, but rather they interact and influence each other reciprocally [

41].

The case-based conditions are: (i) the localisation of the building, (ii) the community-building, and (iii) coproduction.

The framework conditions are related to the local situation where the revitalisation process takes place. These are related to (i) political continuity, (ii) legal and administrative frameworks, and to (iii) the socio-economic environment.

4.1. Case-based conditions

The different case-based conditions influence the revitalisation processes either in positive or negative ways. In particular, one important element is the localisation of the building. Being in the city center, in contrast with being in a peripheral area, is a potentiality. Civic actors involved in revitalising a public building in the central city area (for large cities) may also contribute to creating a scale economy, not only in terms of limitation of transaction costs, but also because they would operate in a more active context. The flow is different, which means that more people might have the chance to get acquainted with the project and participate actively in it.

This element is related to the second

case-based condition, which is the civic actors’ ability and capacity to build a reputation. The

community-building condition relates to the actors’ capacity to be considered as civic agents, and

also being considered as such from the community. It involves the creation of a solid network within and outside the community. This element might be more difficult, but not impractical, when the social capital is low [

59,

60,

61]. In fact, reputation building is more likely to be successful when considering a favourable positioning; while in peripheral and suburban areas revitalisation processes might face some difficulties. The capacity to be recognized from the public administration and citizens is crucial to pursuing revitalisation processes. As these activities are non-profit, they need to have other kinds of revenues and need a certain kind of demand. If the demand is not reciprocated with a specific supply, these experiences are more likely to be unsuccessful throughout time.

Another important case-based condition is the

coproduction [

52]. This element might be considered a consequence of civic actors’ expertise and capacities to work with other subjects (comprising the public administration). The main feature of this aspect is that co-production might occur in varying degrees [

52,

62], but this condition is essential to grant revitalisation processes more possibilities. This might contribute to lowering uncertainty. Co-production and uncertainty are strictly connected in revitalisation processes. In particular, there are two different kinds of ‘uncertainty’: ‘policy ambiguity’, and ‘polity ambiguity’. The ‘policy ambiguity’ is related to the concerns about the legal framework and kind of tools; whilst the ‘polity ambiguity’ is more related to the precariousness of these experiences, and the possibility that they will be interrupted because of public administration actions and decisions.

4.2. Framework conditions

As the case-based conditions, the framework ones might influence the outcome of the revitalisation. They depend largely on normative frameworks and planning policies, on public administrations interface and attitude, and, in general, on the socio-economic environment.

In terms of the legal and normative framework, it is important to highlight that there is a need for specific tools and a transparent legal background. This allows civic actors – but also public administrations – to recognise these experiences as a potentiality. Moreover, there is no shared national framework wrapping up all the different local tools and public devices. This contributes to creating ambiguities, the overlap of norms and uncertainty. The bureaucracy and the legal framework concerning these experiences is still blurred, and the kind of contracts sometimes are not flexible enough to allow civic actors to be forward-looking.

Political continuity is also an important background condition that might influence the success of these experiences. It is a crucial element because its absence could lead to uncertainty. Political continuity is essential, apart from rhetoric and political beliefs, because it encourages (or discourages) these activities [

4,

62].

The last framework condition is the

socio-economic environment, which might be favourable for social entrepreneurship [

50] (Singhal et al., 2013). The incentive derived from the market is the first factor that stimulates civic actors to promote cultural activities, innovative and hybrid services that are not present in the context (and also to overcome the supply-oriented policies that have been promoted since the 1990s). Also, it is an opportunity for public administrations to

test [

18,

20] new activities without costs or save time on further investments. The opportunity for the public administrations with these activities, in fact, is related also to the possibility to re-activate an abandoned or unused space in a public and collective perspective, without any costs. Furthermore, having this space renovated might enlighten public administrations to change land-use policies deliberatively.

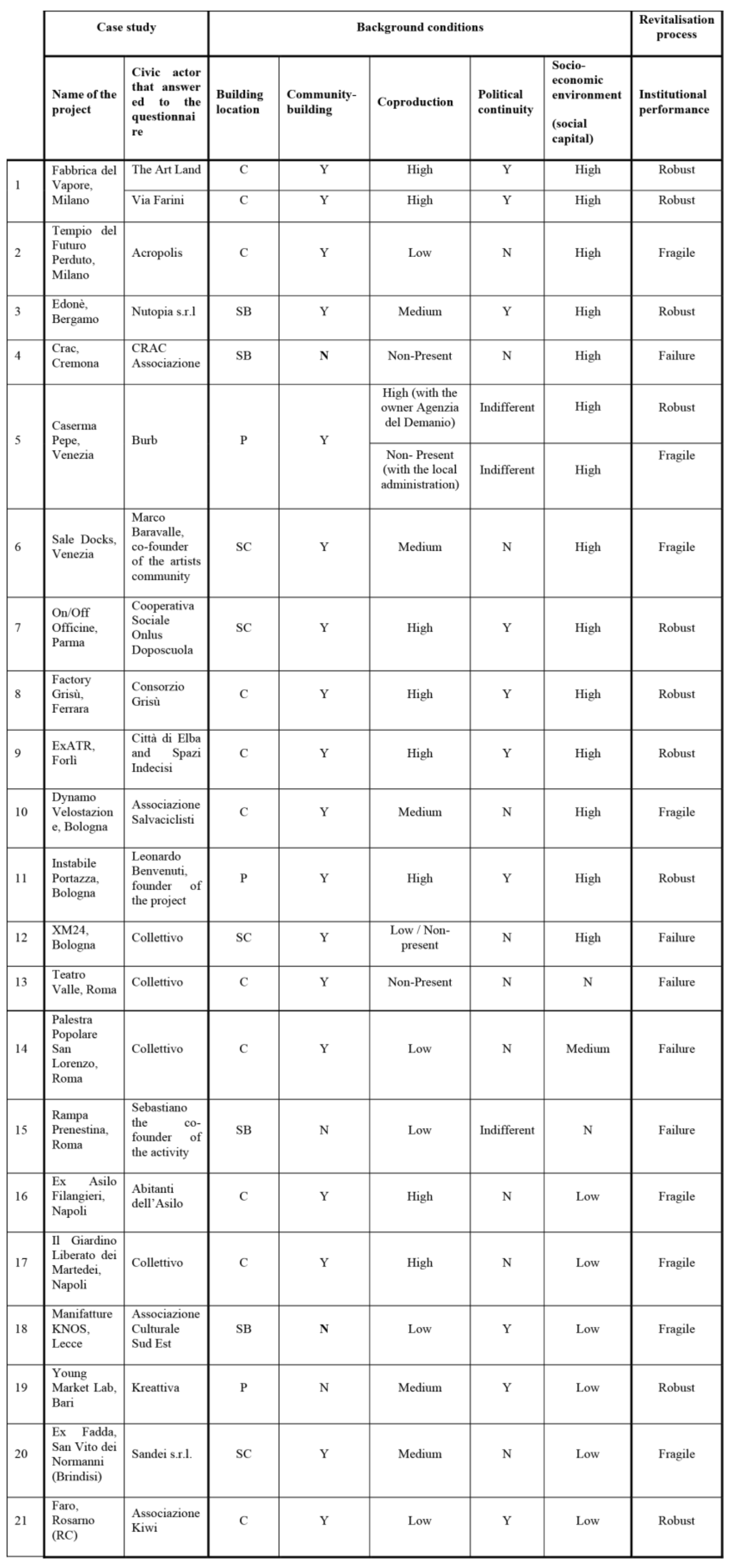

To understand revitalisation processes and the institutional performances, these

background conditions have been ‘evaluated’ accordingly to what has emerged from the analysis of institutions and patterns of behaviour. All the

background conditions have been assessed with criteria allowing the comparison and the presentation of the institutional performance. Roughly, considering the Ostrom’s framework, the cases might be considered from their institutional performance as (i) robust, (ii) fragile, and (iii) failure. The ‘robust’ are the ones that have three or more

background conditions (with a positive absolute value) that are occurring at the same time. The ‘fragile’ cases are the ones that present less than three conditions, or that present a medium level of the absolute value, given to the

background conditions. The ‘failure’ are the ones that do not have a positive degree based on the conditions (

Figure 2).

To sum up, the background conditions are an important element that might contribute to understanding the institutional performaces, and what might influence negatively a revitalisation process. This might depend for example, on the location of the building, the low degree of coproduction, a discontinued political interface, the lack of contextual conditions or the inadequacy of the civic actor to promote itself. The less these conditions are happening, the more possibilities a revitalisation case has to be considered a failure. It might be considered as a checklist to continuously work with, to improve civic actors’ institutional performances.

5. Discussion and policy implications

The background conditions are crucial. Considering them is important to define policy guidelines and derive general discussion about the phenomenon. All the different criteria described might be a proxy to discuss the outcome and the institutional arrangements, with particular reference to revitalisation processes. Moreover, background conditions are derived from specific cases and, although they cover a heterogeneous range of experiences, this paper aims to provide a structured framework for further investigations.

In general, these processes are happening because of a shift in socio-economic and political contexts. The background conditions highlight that some elements are important in principle. The general framework used for this research is important to ground this phenomenon to the actual situation: (i) it helps to define some key elements that are important to understand the very nature of these experiences, and (ii) it highlights how urban planning issues are rarely discussed in those terms. In fact, there is a need to reflect upon the normative framework provided for two main reasons. Firstly, the Italian regulative structure is highly fragmented. That means uncertainty, on the one hand, and difficulties in understanding clearly the processes and the potentiality of revitalisation, on the other. As an example, the effort done with the Legislative Decree no 117 approved in 2017, about the Third Sector Organisation, is not responding to a contemporary situation about the civic actors. This happens because civic actors’ nature is more hybrid and, sometimes, difficult to classify in those pre-arranged categories. Whilst, it would be easier to consider them as they share similar aims. This ‘gap’ might contribute, on the one hand, to increase the level of uncertainty and, on the other, it highlights the need to clarify and update some regulations.

Secondarily, considering civic actors and their revitalisation processes, together with the role of public administrations, would create a different way to consider these practices. As they are not ‘standardised’ but more context-specific, the ‘one fits all’ norms might not be the solution, the processes have to be improved through

background conditions continuously and incrementally. In this way, there is a need to shift from formal rules and norms to the one discussed extensively by Ostrom [

35,

36]. The operational rules are the ones improving the community-building from the side of civic actors, as they influence day-to-day activities and are also considering the kind of attitude performed with public administrations. The collective choice rules are the ones concerning especially the co-production and the political continuity, and they are related to the achievement of collective benefits. These rules, on the one hand, affect indirectly the operational rules, so how civic actors might evolve and trigger the revitalisation process; on the other hand, these rules are used to craft policies. In this case, it comes to light that each process is different, and the policy has to be flexible enough to allow different degree on operational rules in the process. Last, the constitutional choice rules are the ones defined by the effects they have on the other two levels, which means that they might change accordingly to what is happening at the operational level, but at the same time, it enforces them. That is the case of the background condition related with the socio-economic environment.

6. Conclusion

This paper investigates the role that civic actors might have in revitalisation processes, in particular for what concerns the unused publicly owned buildings. It is important to refer to these practices as a potential alternative to the long-standing tradition of privatisation. This does not mean that these experiences are the solution to unused public buildings. There are still a huge amount of processes that might be considered fragile or a failure for different reasons. Also, it is not easy for a civic actor to invest in such assets.

What is crucial, is to discuss this phenomenon with critical tones, without the rhetoric. Furthermore, it is essential to work on background conditions as a tool both for civic actors (but also for public administrations willing to pursue and promote these processes), as well as integrate operational rules and collective choice rules. The constitutional choice rules are the ones that might encounter more problems, as they are not directed to standardisation, but towards diversification. To enhance these experiences, without assuming that they will address the whole demand, it is crucial and essential to define specific policies, flexible enough to allow civic actors to activate those spaces with less limitations (e.g. planning regulations and tools or bureaucracy). This means, for instance, creating codes able to foster these experiences. A code of this kind must provide general, but fundamental, rules that can support different kinds of experiences (as the one presented here). It has to work on background conditions.

Moreover, to have flexible regulations that might vary case-by-case, will (i) enhance the specificity of the locality, (ii) commit both civic actors and public administrations on revitalisation processes in unused public buildings, and (iii) avoid the cut-pasting of laws without any kind of real tie and relationships with the context [

62].

In general, these institutional performaces have highlighted that there is a need to shift from a traditional model of planning, towards another one. This new model has to be: (i) inclusive, which means that formal and informal rules might be used similarly for creative outcomes; (ii) simplified, which means that it is necessary to optimize what is working and to avoid and remove the unnecessary parts ok regulations and norms (as they are also considered a waste of resources [

63] ); (iii) decentralized, which means that the local level might be the most appropriate level for enhancing institutions [

34].

To conclude, revitalisation processes brought about by civic actors might not solve completely the phenomenon of unused public buildings in Italy. The phenomenon will still remain, considering its magnitude. Nevertheless, these practices might be positively considered as a manifesto for social inclusion and public participation in a more general sense Moreover, they might contribute to creating a diverse and non-standardised way to consider planning processes through institutionalism, uncertainty and patterns of behaviour.

References

- Rauws, W.S. (2017) Embracing uncertainty without abandoning planning: Exploring an adaptive planning approach for guiding urban transformations, disP – The Planning Review, 53(1), 32–45. [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, S. , Moroni S. (2021), Multiple agents and self-organisation in complex cities: The crucial role of several properties, Land Use Policy, vol 103(C). [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, S. , Moroni S. (2022), Structural preconditions for adaptive urban areas: Framework rules, several property and the range of possible actions, Cities, vol 130(4). [CrossRef]

- Abastante, F. , Lami I. M., Mecca B. (2021), “Performance indicators framework to analyse factors influencing the success of six urban cultural regeneration cases”, in Bevilacqua C., Calabrò F., Della Spina L. (eds.), New Metropolitan Perspective, vol. 2, Berlin, Springer, 886-897. [CrossRef]

- Ingaramo R., Lami I.M., Robiglio M. (2022), How to Activate the Value in Existing Stocks through Adaptive Reuse: an

Incremental Architecture Strategy, Sustainability, 14(9). [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, V. , Prakash T. (2000), “The cost of governments and the misuse of public assets”, International Monetary Fund, Working Paper.

- Kaganova, O. , Amoils (2020), “Central government property asset management: a review of international changes”, Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 22(3), 239-260. [CrossRef]

- Kaganova, O. , Telgarsky, J. (2018), “Management of capital assets by local governments: An assessment and 850 benchmarking survey”, International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 22(2), 143-156. [CrossRef]

- Vermiglio, C. (2011), “Public property management in Italian municipalities: Framework, current issues and viable solutions”, Property Management, 29(5), 423-442. [CrossRef]

- Evans A., W. (2004), Economics, real estate and the supply of land, Oxford, Blackwell XXX, 2020.

- Moroni, S. , De Franco A., Bellè B. M. (2020a), “Vacant buildings. Distinguishing heterogeneous cases: Public items versus private items; empty properties versus abandoned properties”, in Lami I. (ed.), Abandoned buildings in contemporary cities: Smart conditions for actions, Berlin, Springer, 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S. , De Franco A., Bellè B. M. (2020b), “Unused private and public buildings: re-discussing merely empty and truly abandoned situations, with particular reference to the case of Italy and the city of Milan”, Journal of Urban Affairs, Online ahead of print, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- ANCE (2015), “Osservatorio congiunturale sull’industria delle costruzioni”, Roma .

- Tajani, F. , & Morano, P. (2017), “Evaluation of vacant and redundant public properties and risk control: A model for the definition of the optimal mix of eligible functions”, Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 35(1), 75-100. [CrossRef]

- Mangialardo, A. , Micelli, E. (2018), “From sources of financial value to commons: Emerging policies for enhancing public real-estate assets in Italy”, Papers in Regional Science, 97(4), 1397-1408. [CrossRef]

- Bonini Baraldi, S. , Salone C. (2022), “Building on decay: urban regeneration and social entrepreneurship in Italy through culture and the arts”, European Planning Studies, vol. 30(10), 2102-2121. [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. , Bertolini L. (2019), “Urban experimentation as a politics of niches”, Economy and Space, vol. 51(4), 831-848. [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U. , Spekkink W., Quist J. (2019), “Local sustainability initiatives: innovation and civic engagement in societal experiments”, European Planning Studies, vol. 27(2), 300-317. [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. , Dembski S. (2016), “Manufacturing the creative city: Symbols and politics of Amsterdam North”, Cities, 55, 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. (2018), “Responsibility, polity, value: The (un)changing norms of planning practices”, Planning Theory, 18(1), 58-81. [CrossRef]

- Rauws, W.S. , de Jong M. (2019), “Dealing with tensions: the expertise of boundary spanners in facilitating community initiatives”, in Raco M. and Savini F. (eds.), Planning and Knowledge. How new forms of technocracy are shaping contemporary cities, Bristol, Policy Press, 33-45. [CrossRef]

- Abastante, F. , Lami I. M., Mecca B. (2021), “Performance indicators framework to analyse factors influencing the success of six urban cultural regeneration cases”, in Bevilacqua C., Calabrò F., Della Spina L. (eds.), New Metropolitan Perspective, vol. 2, Berlin, Springer, 886-897. [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L. , Jones M.Z., Daldanise G. (2020), “Platform spaces: When culture and the arts intersect territorial development and social innovation, a view from the Italian context”, Journal of Urban Affairs, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli G., Tognetti R., (2016), L’Italia da riusare. La nuova ecologia. (www.osservatorioriuso.it , last access March 2023).

- Gastaldi, F. , Camerin, F. (2017), “The decommissioning of military real estate”, Scienze Regionali, 16(1), 103-120. [CrossRef]

- Camerin, F. , Gastaldi F. (2018), “Il ruolo dei fondi di investimento immobiliare nella riconversione del patrimonio immobiliare pubblico in Italia” (Working Paper), Urban@it, 2.

- Arena G. (2016), “Cosa sono e come funzionano i patti per la cura dei beni comuni”, Labsus (https://www.labsus.org/2016/02/cosa-sono-e-come-funzionano-i-patti-per-la-cura-dei-beni-comuni/, last access March 2023).

- Labsus (2022), Rapporto 2021. Sull’amministrazione condivisa dei Beni Comuni. (https://www.labsus.org/).

- Ostanel, E. (2017), Spazi fuori dal comune. Rigenerare, includere, innovare, Milano, Franco Angeli.

- Bartoletti, R. , Faccioli, F. (2016), “Public engagement, local policies, and citizens’ participation: An Italian case study of civic collaboration”, Social Media + Society, 2(3), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L. , Pacchi C. (2018), “Community entrepreneurship and co-production in urban development”, Territorio, 87, 69-77.

- Bragaglia, F. (2021), “Social innovation as a ‘magic concept’ for policy-makers and its implications for urban governance”, Planning Theory, 20(2), 102-120. [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L. , De Vidovich L. (2021), “Imprenditorialità, Inclusione o Co-produzione? Innovazione sociale e possibili approcci territoriali”, Crios, 21, pp. 34 – 45. [CrossRef]

- Weck, S. , Madanipour A., Schmitt P. (2021), “Place-based development and spatial justice”, European Planning Studies, vol. 30(5), 791-806. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (1990), Governing the commons. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2005), Understanding institutional diversity, Princeton (N.J.), Princeton University Press.

- Salet, W. (2002), “Evolving Institutions. An International Exploration into Planning and Law”, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 22, 26-35. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. (2017a), “New institutionalism and planning theory”, in Madanipour M.G., Watson A.V. (eds.), Handbook of Planning Theory, London, Routledge, 250-263.

- Healey P. (2007), “The New Institutionalism and the Transformative Goals of Planning”, in Varna N. (ed.), Institutions and Planning, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 61-87.

- Alston, E. , Alston L. J., Mueller B., Nonnenmacher T. (2018), Institutional and organizational analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S. , Healey P. (2005), “A sociological institutionalist Approach to the study of innovation in governance capacity”, Urban Studies, 42(11), 2055-2069. [CrossRef]

- von Schönfeld, K.C. , Tan W., Wiekens C., Salet W., Janssen-Jansen L. (2019), “Social learning as an analytical lens for co-creative planning”, European Planning Studies, 27:7, 1291-1313. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. (2017b), “Institutions and urban space. Land, infrastructure, and governance in the production of urban property”, Planning Theory and Practice, 19(3), 21-38. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (2010), “Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems”, American Economic Review, 100(3), 641-72. https:///doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.

- Gerrin, J. (2017), Case study research. Principles and practices, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Rihoux, B. , Lobe B. (2009), “The case for Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Adding Leverage for thick cross-case comparison”, in Byrne D.S., Ragin C.C. (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Case-Based Methods, Newbury Park (Cal.), Sage Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B. (2013), “Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Reframing the comparative method’s seminal statements”, SPSR – Swiss Political Science Review, 19(2), 233-245. [CrossRef]

- Cellamare, C. (2019), Città fai-da-te. Tra antagonismo e cittadinanza. Storie di autorganizzazione urbana, Roma, Donzelli.

- Mile, S. , Paddison R., (2005), “Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration”, Urban Studies, 42(5-6), 833-839. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S. , McGreal, S., Berry, J. (2013), “An evaluative model for city competitiveness: Application to UK cities”, Land Use Policy 30 (1), 214–222.

- Mangialardo, A. (2017), “Il social entrepreneur per la valorizzazione del patrimonio immobiliare pubblico”, Scienze Regionali, 3, 473-480. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (1996), “Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development”, World Development, 24(6), 1073-1087. [CrossRef]

- Pacchi, C. (2020), Iniziative dal basso e trasformazioni urbane. L’attivismo civico di fronte alle dinamiche di governo locale, Milano, Mondadori.

- North D., C. (1989), “Institutional and economic growth: An historical introduction”, World Development, 17(9), 1319-1332. [CrossRef]

- Gualini, E. (2001), Planning and the intelligence of institutions. Aldershot, Ashgate.

- Hall P., A. , Taylor R. C. R. (1996), “Political science and the three new institutionalisms”, Political Studies, XLIV, 936-957. [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S. , Chiffi D. (2021), “Complexity and Uncertainty: Implications for Urban Planning”, in Portugali J (eds.) Handbook on Cities and Complexity, Northampton, MA, Edward Elgar, 319-330. [CrossRef]

- North D. C. (1992), “Institutions and economic theory”, The American Economist, 36(1), 3-6. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25603904.

- Ferilli, G. , Sacco P. L., Tavano Blessi G., Forbici S. (2016), “Power to the people: when culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not)”, European Planning Studies, 25(2), 241-258. [CrossRef]

- Glackina, S. ,Dionisio M.R. (2016), “ ‘Deep engagement’ and urban regeneration: tea, trust, and the quest for co-design at precinct scale”, Land Use Policy (52), 363-373. [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. (2003), “Assessing the discourses and practices of urban regeneration in a growing region”, Geoforum, 34, 37-55. [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R. , Iaione C. (2018), “Ostrom in the city: Design principles and practices for the urban commons”, in Cole D., Hudson B., Rosenbloom J. (eds.), Handbook of the study of the commons, Routledge, 235-255.

- De Soto, H. (1989), The Other Path, New York, Basic Book.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).